1 Introduction

This paper is concerned with the phenomenon of Root Infinitives (RIs) in the acquisition of Jamaican Creole (JC). RIs are constructions involving an infinitival verbal form in a main declarative found in (some) child languages, although not in the target adult languages. This construction has been observed in the acquisition of numerous non-null subject languages (Wexler 1994), and/or in the acquisition of languages in which the non-finite verbal form does not raise to T (Rizzi 1993/94), such as Dutch (Haegeman 1995), French (Crisma 1992), German (Clahsen, Kursawe & Penke 1996), Swedish (Santelmann 1995; Josefsson 2002), among others (see Rasetti 2000 for an overview). These languages possess a morphologically distinct infinitival form, and RIs display this form of the verb in a declarative, where the adult equivalent utterance would employ a tensed verb instead (e.g., French, Papà partir ‘Daddy leave+INF’). In languages lacking a morphologically inflected infinitive, the question arises as to whether the construction is attested at all and what form it takes. English is a case in point, for which a standard assumption is that RIs exist in child productions and are manifested by main clauses with uninflected verbal roots (Daddy leave: Wexler 1994 and much related literature; on other languages, see Varlokosta, Vainikka & Rohrbacher 1996; Garcia 2007; Sugiura, Sano & Shimada 2016; among others).

In JC, as in other Creole languages, the lexical verb is always accompanied by an overt subject and is always uninflected. It co-occurs with particles expressing temporal, modal and aspectual properties (the TMA system) typically expressed by finite verbal inflections in Indo-European languages. RIs are thus likely to emerge during the acquisition of JC and are expected to take a verbal form unaccompanied by the TMA particles that would be required in the adult language in the particular discourse situation in which the sentence is uttered.1 This is, in essence, the approach defended by Pratas and Hyams (2009) for children acquiring another creole language, Capeverdean Creole.

We examine JC children’s omission of aspectual markers in order to (a) determine if early JC includes a root infinitive stage and (b) shed light on the temporal and aspectual interpretations of this verb form in JC. Of course, the mere existence of non-target consistent bare verbal forms in child JC would not suffice to establish the existence of an RIs stage. A cluster of properties already shown to correlate with RIs in other child languages would also need to be observed, such as the occurrence of the uninflected verbal form in declaratives but not in wh-questions (Rizzi 1993/4), their tendency to occur in sentences with a phonetically null subject, with these significantly more frequent in RIs than in finite clauses (much literature summarized in Rasetti 2000), and the roughly concomitant disappearance of RIs and of subject drop in finite clauses in development. These properties require a careful scrutiny in view of arguing for an RIs stage in the acquisition of the language.

This paper is organized as follows. In section 1.1 we summarize some properties of JC which are relevant for the analysis of the developmental facts. In section 1.2 we go through the basic properties of RIs in the acquisition of different languages. Section 1.3 details the research questions and Section 2 outlines the methodology employed in the study. Section 3 analyses the production of bare verbs and progressive and prospective aspects which leads to an examination of root infinitives with overt/null subjects in declarative and interrogative clauses. Section 4 discusses the results and concludes the paper.

1.1 Relevant properties of Jamaican Creole

While JC is a non-null subject language, children acquiring JC display a null-subject phase (De Lisser, Durrleman, Rizzi & Shlonsky 2016), as is typically observed in the development of non-null subject languages. It is an SVO language with various free pre-verbal morphemes that accompany the verb to express Tense, Modality and Aspect. Such markers form a functional sequence, which conforms to the general cartographic hierarchy identified by Cinque (1999), as shown in detail in Durrleman (2008). Unmarked non-stative verbs are normally interpreted with a past reference (example 1a).2 In the case where the past tense marker did (or its variants) is inserted before a non-stative verb, it tends to yield an anterior past interpretation (example 1b). Unmarked stative verbs tend to be interpreted as non-past (example 2a), for which the insertion of the past tense marker is necessary in order to yield a past interpretation (example 2b).

- (1)

- a.

- Im

- s/he

- se

- say

- dat

- that

- siem

- same

- ting

- thing

- de.

- there

- “S/he said that very thing.”

- b.

- Im

- s/he

- did

- PAST

- se

- say

- dat

- that

- siem

- same

- ting

- thing

- de.

- there

- “S/he had said that very thing.”

- (2)

- a.

- Jan

- John

- tingk

- think

- se

- that

- im

- he

- a

- [equative]

- di

- the

- bes.

- best

- “John thinks/*thought that he is/*was the best.”

- b.

- Jan

- John

- did

- PAST

- tingk

- think

- se

- that

- im

- he

- a

- [equative]

- di

- the

- bes.

- best

- “John thought that he was the best.”

Other factors, such as context, may impact the temporal reading of the verb (Durrleman 2008). An unmarked verb alone cannot express progressive aspect, although it can express habitual aspect (example 3a). The progressive aspect marker a, da or de, and the prospective aspect marker a_(g)o, gaa, or gwain, are obligatory, as their omission yields differences in temporal/aspectual interpretation (examples 3b and 3c).3

- (3)

- a.

- Jan

- John

- nyam

- eat

- i.

- it

- “John ate it/John eats it (habitually)/*John is eating it.”

- b.

- Jan

- John

- a

- [+PROG]

- nyam

- eat

- i.

- it

- “John is eating it.”

- c.

- Jan

- John

- a_go

- [+PROS]

- nyam

- eat

- i.

- it

- “John is going to eat it.”

Unmarked verbs can also be non-finite verbs which need no pre-verbal infinitival marker. However, fi, go, or both fi go would generally occur before non-finite verbs (example 4). According to Patrick (2007; p.7) “Fi is common but optional with a number of verb types licensed for zero-infinitives in other languages,” however, in some cases infinitival fi cannot be deleted, nor can it be replaced by its counterparts go or fi go (example 5); proving infinitives to be a complex phenomenon in JC.

- (4)

- Spen

- Spend

- mai

- POSS

- faiv

- five

- dala

- dollar

- fi

- to

- go

- go

- bai

- buy

- wan

- one

- manggo!

- mango

- “Spend my five dollars to buy one mango!”

- (5)

- Jan

- John

- iizi

- easy

- fi

- to

- krai.

- cry

- “John cries easily”

Child productions in our corpus contain both utterances with adult-like specifications of aspect markers (examples 6 and 7), and target-inconsistent utterances with bare lexical verbs, but with contextually inferred interpretations of progressive or prospective aspect (examples 8a and 9a). The examples in (8b) and (9b) illustrate the adult grammar meanings of child productions of aspectual interpretation with bare verbs.

- (6)

- Mi

- 1SG

- a

- PROG

- luk

- look

- fi

- for

- wan

- Q:indef

- mongki.

- monkey

- (TYA 2;10)

- “I am looking for a monkey.”

- (7)

- Mi

- 1SG

- a_go

- PROS

- yuuz

- use

- i

- DEF

- sopm

- something

- yaso.

- LOC

- (KEM 2;07)

- “I am going to use the thing here.”

- (8)

- a.

- CHI:

- Mi

- 1SG

- Ø

- Ø

- fiks

- fix

- i

- 3SG

- bak.

- back

- (ALA 2;02)

- “I am fixing it back.” (intended meaning)

- INV:

- Yaa

- 2SG~PROG

- fiks

- fix

- i

- 3SG

- bak?

- back

- “Are you fixing it back?”

- b.

- Mi

- 1SG

- Ø

- Ø

- fiks

- fix

- i

- 3SG

- bak.

- back

- “I fixed it back.” (adult grammar meaning)

- (9)

- a.

- CHI:

- Felisha

- Felisha

- Ø

- Ø

- kyari

- carry

- mi.

- 1SG

- (RJU 2;05)

- “Felisha is going to carry me.” (intended meaning)

- MOT:

- Yes

- Yes

- Felisha

- Felisha

- gwain

- PROS

- kyari

- carry

- yo.

- 2SG

- “Yes, Felisha is going to carry you.”

- b.

- Felisha

- Felisha

- Ø

- Ø

- kyari

- carry

- mi.

- 1SG

- “Felisha carried me.” (adult grammar meaning)

De Lisser, Durrleman, Shlonsky and Rizzi (2017) provide evidence that JC children at an early age have a clear grasp of the functional projections of the IP of their target grammar. Specifically, they produce utterances consistent with the cartographic structure of the entire TMA domain and do not entertain target-inconsistent TMA combinations. In the current work, we turn our attention to instances of TMA omissions where a particular temporal and aspectual meaning is intended, a target-inconsistent production typically found in development.

1.2 Root Infinitives

Much work has been devoted to the RIs acquisition stage over the years, and different models to interpret it theoretically have been proposed: the Agreement/Tense Omission Model (ATOM) (Schuetze & Wexler 1996); the Unique Checking Constraint Model (UCC) (Wexler 1998); the Truncation Approach (Rizzi 1993/4); the Aspectual Anchoring Hypothesis (Hyams 2007, 2011); the Variational Learning Model (Legate & Yang 2007); and models stipulating a feature-based developmental pattern, with uninterpretable (inflectional) features emerging later than interpretable features (Tsimpli 2005), etc. Most of these approaches are united in arguing that, at an early stage of development, children’s syntactic representation and computation is, in some sense, impoverished as compared with adult grammar. According to the ATOM, for instance, RIs (or Optional Infinitives/OI) arise when tense or agreement features are left underspecified in the child’s clausal representation, causing the verb to surface in its bare form. The ATOM later developed into the UCC, which states that only one uninterpretable feature can be checked in the derivation, i.e. either T or Agr can be checked, but not both. Another view is that the parametric values of such inflectional features, being uninterpretable at LF, are acquired later than interpretable features such as wh (see Tsimpli 2005). The Aspectual Anchoring Hypothesis holds that RIs are a result of children exploring the parametric option of encoding temporal meanings via aspectual instead of temporal marking, an idea also found in the Variational Learning Model (Legate & Yang 2007). The latter further explains why the temporal option is more delayed in some instances than in others, i.e. this variation would be due to lack of sufficient evidence. More specifically, as UG allows tense to be active morphosyntactically (as in English or Spanish) or not (as in Mandarin), children would require sufficient evidence to set the parameter one way or another, and this setting would be delayed in instances where the input provides less unambiguously tensed verbs (as for English) than when the input is more consistent in this respect (as in Spanish), yielding an RIs phase in the former case.

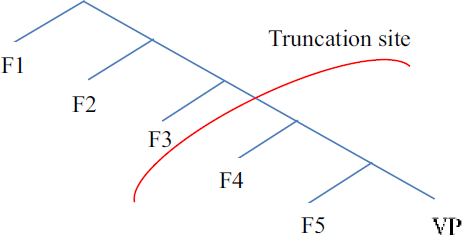

Despite the merits of these approaches, they do not explain various structural restrictions associated with RI, which follow straightforwardly from the Truncation model (Rizzi 1993/4), to which we now turn. This approach assumes that child systems can truncate the structural tree at different layers: the tree will then exclude all the positions above the truncation site and include all the positions below it.

- (10)

So a truncated configuration can only have missing layers which are external and higher than the truncation site (F1, F2, F3 in (10)), but not internal missing layers. In (10), F5 could not be missing if it is an obligatory layer while F4 is present. Classical truncation understood the process as involving the structural absence of the truncated material (Rizzi 1993/4): in these terms, F1, F2, F3 are simply not present in representation (10), and the root of the structure is the projection of F4. De Lisser et al. (2016) discussed a weaker version of truncation, looking at it as a spell-out phenomenon. In this view, the representation in (10) is complete and projects up to F1, but spell-out stops at F4, so that F1, F2, F3 are structurally present but unpronounced. The two views make different predictions in certain cases, but we will not go into the intricate details of the empirical evidence distinguishing them.

The truncation hypothesis predicts that if RIs involve truncation below the T node (hence missing the tense specification and requiring a non-finite verbal form), they should be unavailable in sentences requiring access to structural layers from TP upwards. We will focus in the current work on the subset of properties that we can immediately test in JC, namely:4

RIs should be incompatible with wh-questions, which require the presence of the CP layer to host the wh-element (Crisma 1992 on French). This prediction is to a large degree confirmed: For instance, in Child Dutch, Haegeman (1995a) found 16% RIs among non-interrogative clauses and 2.5% among wh-interrogatives. Similarly, for French, Crisma (1992) reported 15% nonfinite main verbs in declaratives and 0% in wh-questions.5

RIs may be consistent with yes-no questions, if, in the particular language under consideration, these do not have to be signaled through the activation of the left periphery (as in English, with I to C movement). See below for discussion.

1.3 Research questions

Based on the above, we can address the issue of the existence and manifestation of RIs in child JC. What would RIs look like in a Creole language, in which verbs are not morphologically inflected, and in the absence of a distinctive morphology for infinitival verbs? Building on Pratas and Hyams’ (2009) analysis of Capeverdean Creole, we assume that a root infinitive involves a clause with a bare verb in contexts in which the adult grammar requires the appropriate tense and/or aspect marker. In this article we focus on progressive and prospective aspect, the most common aspectual specifications which are mastered early on by language learners (De Lisser, et al. 2017). So, the following questions arise:

Do we find, in child JC natural productions, a robust attestation of target-inconsistent cases of bare verbs expressing interpretations of progressive or prospective aspect?

Do such target-inconsistent uses manifest the structural properties of RIs in other languages, i.e. are they incompatible with wh-questions, while being consistent with yes-no questions?

2 Methodology

This study is based on a longitudinal observation and analysis of six monolingual JC speaking children for a period of 18 months. At the start of the observation period, the children’s ages ranged from 1;06–1;11 months. This age range is critical as it is the period in which syntax typically emerges in children and during which target-inconsistent forms and structures have been documented in other languages. The corpus consists of recordings of naturalistic conversations between/among the target child, the investigator, parents, siblings and occasionally other relatives and friends. The informants were strategically selected from households with speakers of the most basilectal JC varieties, and as such, despite the continuum situation existing in Jamaica, the interference of English in the children’s linguistic environment was minimal. The methodology employed in the selection of participants and the collection of the data is detailed in De Lisser, Durrleman, Rizzi and Shlonsky’s (2014) work. All utterances containing at least one verb were selected to be included in this analysis. The utterances identified for analysis were coded for null/overt subjects, stativity, the presence or absence of tense, and aspectual markers and the location of the markers with respect to the verb. Native speakers’ intuitions were employed in distinguishing between contexts of utterances that could possibly yield multiple temporal and aspectual interpretations. Additionally, data produced within the first two months were not included, as this period included finalizing the selection of children for inclusion in the study and familiarization of the researchers with the informants. Therefore, the actual age range taken into account was between 1;08 and 3;04.

3 Results

3.1 Bare verbs in JC

The data reveals a total 12,592 bare verbs in the corpus. The temporal and aspectual interpretation of each example was evaluated by a native speaker in the context in which the example occurred, in order to tease apart target consistent and target inconsistent uses by children. Out of this total, 5765 non-stative bare verbs occurred in contexts with a past time interpretation (example 11) and 4404 with a present interpretation with a stative verb (example 12), in accordance with adult grammar. However, 2423 bare verbs were used target inconsistently in that they occurred in contexts which expressed progressive and prospective aspectual interpretations (example 13): such cases would require overt progressive or prospective aspectual marking in adult grammar.

- (11)

- Ø

- Ø

- prie

- spray

- i

- DEF

- grong.

- ground

- (KEM 2;05)

- “He sprayed the field.”

- (12)

- Ø

- Ø

- waa

- want

- som

- INDEF

- juus.

- juice

- (KEM 2;05)

- “I want some juice.”

- (13)

- INV:

- A

- FOC

- wa

- what

- im

- 3SG

- a

- PROG

- du?

- do

- “What is he doing?”

- CHI:

- Jan

- John

- daans

- dance

- (COL 1;09)

- “John is dancing.”

Why do children overextend the use of bare verbs to utterances reflecting aspectual interpretations? Do children also show adult-like behavior in their production of aspectual markers? An investigation of the production of progressive and prospective aspects will be presented in the following section.

3.2 Progressive and prospective aspects in early Jamaican Creole

As examples (8) and (9) demonstrate, the omission of the aspectual markers in JC leads to a difference in the temporal interpretation of the utterance. Though these differences are subtle, based on the context of utterance, we are able to determine where they should have been present but were omitted. Such an analysis allows us to map more clearly the development of the aspectual zone. We present in Table 1 a detailed analysis of the development of the progressive and prospective aspect, mapping the production of the overt progressive and prospective aspectual markers compared to their respective omissions, as deduced from the context of the utterance.

Production (PROG/PROS) and Omission (0 PROG/0 PROS) of Progressive and Prospective Aspect of the six JC-speaking children.

| AGE | PROGRESSIVE ASPECT | PROSPECTIVE ASPECT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Y;M) | TOTAL | 0 PROG | % | PROG | % | TOTAL | 0 PROS | % | PROS | % |

| 1;8.0 | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1;8.5 | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1;9.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 1;9.5 | 22 | 20 | 91 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 1;10.0 | 15 | 12 | 80 | 3 | 20 | 7 | 7 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 1;10.5 | 27 | 20 | 74 | 7 | 26 | 11 | 10 | 91 | 1 | 9 |

| 1;11.0 | 57 | 44 | 77 | 13 | 23 | 19 | 19 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 1;11.5 | 37 | 26 | 70 | 11 | 30 | 22 | 21 | 95 | 1 | 5 |

| 2;0.0 | 43 | 31 | 72 | 12 | 28 | 12 | 9 | 75 | 3 | 25 |

| 2;0.5 | 69 | 47 | 68 | 22 | 32 | 30 | 26 | 87 | 4 | 13 |

| 2;1.0 | 86 | 71 | 83 | 15 | 17 | 40 | 37 | 93 | 3 | 8 |

| 2;1.5 | 111 | 77 | 69 | 34 | 31 | 45 | 42 | 93 | 3 | 7 |

| 2;2.0 | 111 | 66 | 59 | 45 | 41 | 99 | 55 | 56 | 44 | 44 |

| 2;2.5 | 121 | 78 | 64 | 43 | 36 | 73 | 56 | 77 | 17 | 23 |

| 2;3.0 | 105 | 47 | 45 | 58 | 55 | 87 | 61 | 70 | 26 | 30 |

| 2;3.5 | 151 | 83 | 55 | 68 | 45 | 57 | 47 | 82 | 10 | 18 |

| 2;4.0 | 119 | 54 | 45 | 65 | 55 | 49 | 34 | 69 | 15 | 31 |

| 2;4.5 | 138 | 59 | 43 | 79 | 57 | 73 | 49 | 67 | 24 | 33 |

| 2;5.0 | 87 | 45 | 52 | 42 | 48 | 52 | 44 | 85 | 8 | 15 |

| 2;5.5 | 174 | 65 | 37 | 109 | 63 | 98 | 70 | 71 | 28 | 29 |

| 2;6.0 | 114 | 32 | 28 | 82 | 72 | 64 | 36 | 56 | 28 | 44 |

| 2;6.5 | 142 | 36 | 25 | 106 | 75 | 74 | 39 | 53 | 35 | 47 |

| 2;7.0 | 239 | 38 | 16 | 201 | 84 | 107 | 32 | 30 | 75 | 70 |

| 2;7.5 | 178 | 43 | 24 | 135 | 76 | 123 | 38 | 31 | 85 | 69 |

| 2;8.0 | 228 | 42 | 18 | 186 | 82 | 121 | 50 | 41 | 71 | 59 |

| 2;8.5 | 223 | 25 | 11 | 198 | 89 | 118 | 22 | 19 | 96 | 81 |

| 2;9.0 | 170 | 30 | 18 | 140 | 82 | 112 | 25 | 22 | 87 | 78 |

| 2;9.5 | 158 | 29 | 18 | 129 | 82 | 120 | 46 | 38 | 74 | 62 |

| 2;10.0 | 152 | 29 | 19 | 123 | 81 | 93 | 19 | 20 | 74 | 80 |

| 2;10.5 | 157 | 15 | 10 | 142 | 90 | 93 | 22 | 24 | 71 | 76 |

| 2;11.0 | 175 | 24 | 14 | 151 | 86 | 117 | 30 | 26 | 87 | 74 |

| 2;11.5 | 131 | 21 | 16 | 110 | 84 | 78 | 18 | 23 | 60 | 77 |

| 3;0.0 | 195 | 17 | 9 | 178 | 91 | 154 | 29 | 19 | 125 | 81 |

| 3;0.5 | 211 | 24 | 11 | 187 | 89 | 98 | 12 | 12 | 86 | 88 |

| 3;1.0 | 147 | 17 | 12 | 130 | 88 | 194 | 26 | 13 | 168 | 87 |

| 3;1.5 | 113 | 9 | 8 | 104 | 92 | 167 | 20 | 12 | 147 | 88 |

| 3;2.0 | 179 | 11 | 6 | 168 | 94 | 100 | 19 | 19 | 81 | 81 |

| 3;2.5 | 126 | 12 | 10 | 114 | 90 | 113 | 11 | 10 | 102 | 90 |

| 3;3.0 | 103 | 4 | 4 | 99 | 96 | 89 | 11 | 12 | 78 | 88 |

| 3;3.5 | 76 | 6 | 8 | 70 | 92 | 35 | 2 | 6 | 33 | 94 |

| 3;4.0 | 32 | 1 | 3 | 31 | 97 | 30 | 2 | 7 | 28 | 93 |

| 3;4.5 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100 | 27 | 8 | 30 | 19 | 70 |

| TOTAL | 4745 | 1313 | 28 | 3432 | 72 | 3007 | 1110 | 37 | 1897 | 63 |

The data shows that children abundantly produced both progressive utterances (4745) and prospective utterances (3007), whether overtly marked or not. The total number of correctly marked progressive and prospective aspects, reflecting adult-like usage, is 3432 and 1897, respectively. While the total number of unmarked structures with progressive and prospective interpretations is lower, 1313 and 1110 respectively, their attestation in the data is substantial. The progressive marker shows a 28% omission rate while the prospective aspect marker was omitted in 37% of the utterances under consideration.

We would like to note that in adult JC, the use of the progressive marker is limited to non-stative verbs. The data was therefore analyzed to determine whether other errors, besides omissions, were prevalent in the children’s production. The examination of the data reveals that children do not incorrectly overextend progressive markings to stative verbs (in line with Bickerton 1981; Erbaugh 1992; Shirai and Andersen 1995; among others).6 This suggests that children master the use of the progressive marker from early on.

Additionally, we see where the progressive marker is used target-consistently with the following arguably stative verbs (verbs of bodily sensation) but with a dynamic reading: pien ‘pain’, fiil ‘feel’, si ‘see’, luk ‘look’ and ier ‘hear’. The data also reveals utterances where the progressive marker was incorrectly extended to a prospective utterance, as in (14). The number of these utterances was very small as only 15 cases were identified.

- (14)

- *Man

- man

- a

- PROG

- paas

- pass

- dier

- there

- so.

- LOC

- (ALA, 2;05)

- “The man is going to pass there.”

The analysis of the aspectual markers therefore reveals that errors of commission are virtually unattested, while errors of omission are robust.

Examples (15)–(20) are cases in point of utterances with aspectual interpretations, but for which there are grammatical errors of omission. These are child-specific constructs that, based on the contexts of utterance and intended interpretation, clearly omit the overt aspectual distinctions, and as such are not in line with adult JC grammar.

- (15)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- uol

- hold

- mi

- 1SG

- fut.

- foot

- (SHU 2;03)

- “She is holding my foot.”

- (16)

- It

- 3SG

- Ø

- Ø

- born.

- burn

- (TYA 2;01)

- “It is burning.”

- (17)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- bons

- bounce

- it.

- 3SG

- (COL 1;11)

- “I am bouncing it.”

- (18)

- Momi

- Mommy

- Ø

- Ø

- biit

- beat

- yu.

- 2SG

- (RJU 2;01)

- “Mommy is going to beat you.”

- (19)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- gi

- give

- guoti.

- goatie

- (ALA 1;10)

- “She is going to give goatie.”

- (20)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- shuo

- show

- Moesha

- Moesha

- i

- DEF

- kyat.

- cat

- (TYA 2;08)

- “I am going to show Moesha the cat.”

Recall that in adult JC, bare non-stative verbs are interpreted as past tense. However, as these examples demonstrate, children employ bare verbs also in contexts of present progressive (15–17) and prospective (18–20) interpretations. These utterances, which express aspectual reading in the absence of the appropriate aspectual morphemes, are naturally interpreted as the language-specific variants of the RIs stage in JC.

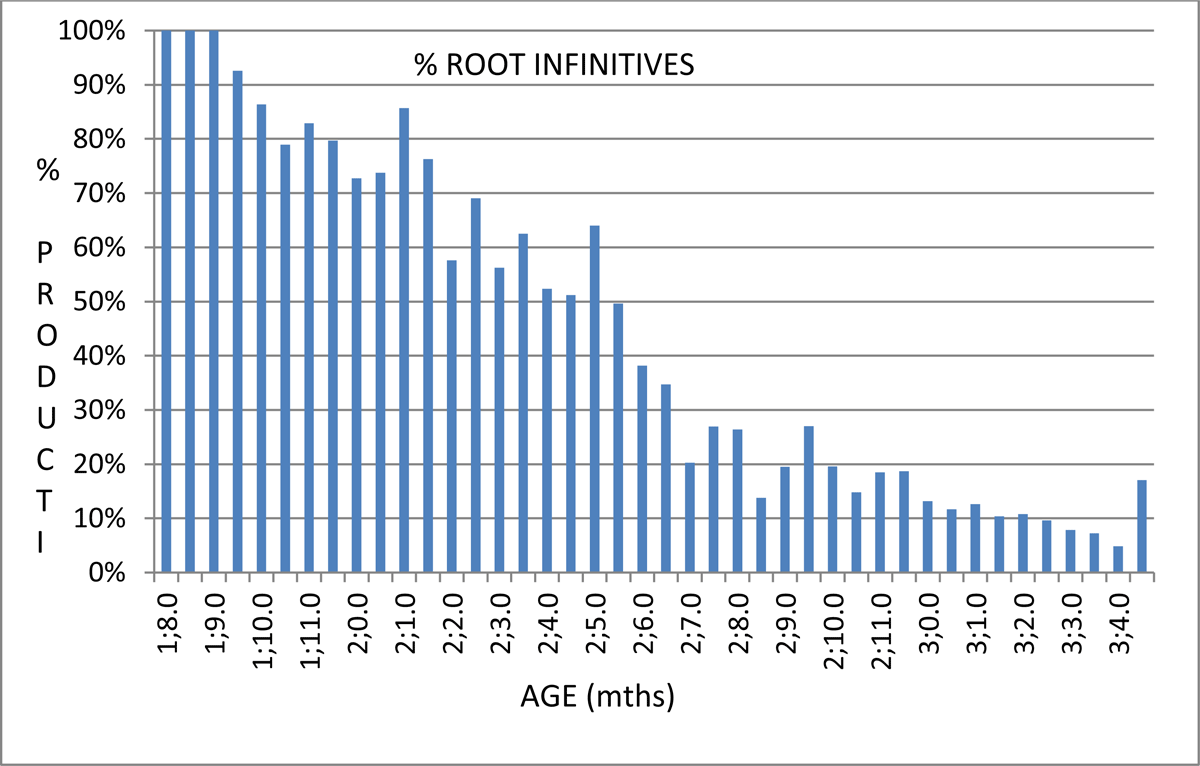

RIs in JC, understood as target-inconsistent omissions of aspectual markers, are at their peak at the beginning of the recordings (1;08). The phenomenon decreases in the course of the third year of life and drops to around 10% at age 3:

Figure 1 demonstrates the production of RIs with aspectual interpretations in the corpus (see Appendix 1 for details).

The interpretation of utterances lacking an aspectual marker as a language-specific variant of RIs is made plausible by the roughly parallel loss of bare verbs with aspectual interpretation, as evidenced from Figure 1, and the loss of root null subjects, as discussed in De Lisser et al. (2016). Figure 1 shows that bare verbs with aspectual interpretation steadily decline in the second half of the third year of life, and fluctuate around 10% at age 3. Similarly, as figure 7 of De Lisser et al 2016 shows, the production of sentences with null subjects drops to 20% at age 2;08, and fluctuates around 10% at age 3. A concomitant loss of subject drop and RIs is expected if the two are traced back to the same underlying factor, namely the availability of truncation; see §1.2.

If the interpretations of aspect drop as the language specific manifestation of RIs is made plausible by these considerations, what remains to be done to consolidate the analysis is to determine whether the child productions with missing aspect respect the other structural constraints which typically characterize RIs across languages, as discussed in § 1.2. We address this question in the next sections.7

3.3 Root Infinitives and Overt/Null Subjects

The data in our corpus contains both structures with target-inconsistent aspect omission which have a null subject, as in examples (21-30), as well as such structures with an overt subject, as in examples (31–40):8

- (21)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- chobl

- trouble

- i

- DEF

- maabl.

- marble

- (ALA 2;04)

- “He is troubling the marble.”

- (22)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- chuo

- throw

- oot

- out

- i.

- 3SG

- (KEM 2;00)

- “I am throwing it out.”

- (23)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- jraiv

- drive

- it.

- 3SG

- (RJU 1;11)

- “She is driving it.”

- (24)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- sidong

- sit

- ina

- in

- mi

- 1SG

- chier.

- chair

- (SHU 2;03)

- “He is sitting in my chair.”

- (25)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- riid

- read

- buk.

- book

- (TYA 2;07)

- “They are reading a book.”

- (26)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- bied

- bathe

- im

- 3SG

- outsaid.

- outside

- (COL 1;11)

- “He is going to bathe him outside.”

- (27)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- jrap

- drop

- aaf.

- off

- (KEM 2;00)

- “They are going to fall off.”

- (28)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- torn

- turn

- aan

- on

- i.

- 3SG

- (RJU 2;01)

- “I am going to turn it on.”

- (29)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- bring

- bring

- som

- some

- priti

- pretty

- blous.

- blouse

- (SHU 2;05)

- “She is going to bring some pretty blouses.”

- (30)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- wet

- wet

- op

- up

- mi.

- 1SG

- (TYA 2;07)

- “It is going to wet me up.”

- (31)

- Mi

- 1SG

- Ø

- Ø

- fiks

- fix

- i

- 3SG

- bak.

- back

- (ALA 2;02)

- “I am fixing it back.”

- (32)

- Granmaa

- grandma

- Ø

- Ø

- kech

- catch

- waata.

- water

- (RJU 2;02)

- “Grandma is catching water.”

- (33)

- Jan

- John

- Ø

- Ø

- daans.

- dance

- (COL 1;10)

- “John is dancing.”

- (34)

- Mi

- 1SG

- Ø

- Ø

- go

- go

- fi

- for

- dem.

- 3PL

- (SHU 2;06)

- “I am going for them.”

- (35)

- Mi

- 1SG

- Ø

- Ø

- ron

- run

- gaan

- gone

- lef

- leave

- yo.

- 2SG

- (KEM 3;03)

- “I am running leave you.”

- (36)

- Felisha

- Felisha

- Ø

- Ø

- kyari

- carry

- mi.

- 1SG

- (RJU 2;05)

- “Felisha is going to carry me.”

- (37)

- Momi

- mommy

- Ø

- Ø

- wash

- wash

- i

- it

- (COL 2;02)

- “Mommy is going to wash it.”

- (38)

- Yu

- 2SG

- mada

- mother

- Ø

- Ø

- kom

- come

- fi

- for

- yu

- 2SG

- an

- and

- biit

- beat

- yu.

- 2SG

- (SHU 2;09)

- “Your mother is going to come for you and beat you.”

- (39)

- Mii

- 1SG

- Ø

- Ø

- tek

- take

- im

- 3SG

- op.

- up

- (ALA 2;02)

- “I am going to take him up.”

- (40)

- Mii

- 1SG

- an

- and

- Aleks

- Alex

- Ø

- Ø

- kola

- colour

- oova

- over

- de-so.

- LOC

- (TYA 3;01)

- “Alex and I are going to colour over there.”

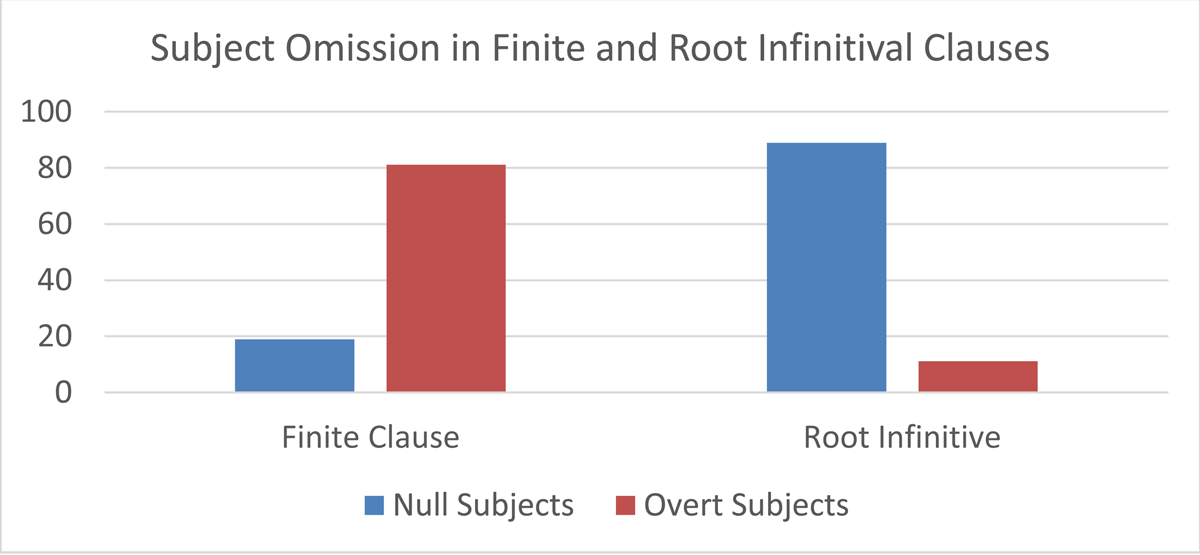

The two cases are not equally frequent, though. Overt subjects are only attested in 16% (395 out of 2423) of RIs utterances. So RIs are much more frequent in environments where the subject is dropped (84%), compared to environments where the subject is overtly pronounced.

Further analysis of the data reveals that null subjects are much more frequent with RIs than with finite clauses. As demonstrated in Table 2, the total proportion of null subjects in finite declarative clauses in JC is a mere 18.9% when compared to 88.9% null subjects with root infinitival declarative clauses.9

Subject Omission in Finite and Root Infinitival clauses in JC.

| Informants | Null subj+fin | % | Null subj RI | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | 510/2205 | 23.1 | 373/437 | 85.3 |

| ALA | 454/2710 | 16.8 | 306/350 | 87.7 |

| RJU | 550/2350 | 23.4 | 321/392 | 81.9 |

| TYA | 229/1148 | 19.9 | 224/239 | 93.7 |

| KEM | 667/3458 | 19.3 | 558/591 | 94.4 |

| SHU | 248/2168 | 11.4 | 158/174 | 90.8 |

| TOTAL | 2658/14039 | 18.9 | 1940/2183 | 88.9 |

Figure 2 offers a visual representation of the findings detailed above. There is a striking asymmetry between the environments where null subjects occur. While they are preponderant in root infinitival clauses, they are much less frequently attested in finite clauses over the whole period taken into consideration (they are robustly attested till around age 30 months, (see De Lisser et al. 2016 for discussion).

The findings, as illustrated in Figure 2, are in line with findings from other languages as detailed in Table 3.

Subject Omission in Finite and Root Infinitival clauses.

| Informants | Null subj+fin | % | Null subj RI | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| French | ||||

| Daniel (Pierce, 1989) | 150/273 | 54.9 | 166/205 | 81.0 |

| Nathalie (Pierce, 1989) | 90/304 | 29.6 | 131/295 | 44.4 |

| Philippe (Pierce, 1989) | 182/782 | 23.3 | 153/194 | 78.9 |

| Augustin (Rasetti, 1999) | 157/582 | 26.8 | 66/71 | 93.0 |

| Marie (Rasetti, 1999) | 154/560 | 27.5 | 130/134 | 97.0 |

| German | ||||

| Simone (Behrens, 1993) | 781/3699 | 21.1 | 2199/2477 | 88.8 |

| Andreas (Krämer, 1993) | 34/263 | 12.9 | 69/101 | 68.3 |

| Dutch | ||||

| Thomas (Krämer, 1993) | 165/596 | 27.7 | 246/267 | 92.1 |

| Heinz (Haegeman, 1995a) | 1199/3768 | 31.8 | 615/721 | 85.3 |

| Flemish | ||||

| Maarten (Krämer, 1993) | 23/92 | 25.0 | 89/100 | 89.0 |

| Faroese | ||||

| O. (Jonas, 1995) | 8/52 | 15.4 | 67/161 | 41.6 |

| Danish | ||||

| Anne (Hamann & Plunkett, 1998) | 366/3379 | 10.8 | 394/667 | 59.1 |

| Jens (Hamann & Plunkett, 1998) | 742/3173 | 23.4 | 539/937 | 57.5 |

The proportion of null and overt subjects in JC sentences with a missing aspectual marker is thus fully comparable to the proportion of null and overt subjects with RIs in other languages. This provides comparative support for the hypothesis that aspectless bare verb clauses in child JC are the language-specific expression of RI.

If we now go back to the truncation approach, an analytic question arises. If overt subjects require case (Chomsky 1981) and if nominative is dependent on the presence of T, then structures truncated below T would be predicted to never permit overt subjects. The data show that, while clearly less frequent than in finite environments, overt subjects are attested. Why is it so? Notice that the prediction of the truncation approach is fulfilled by weak pronominal subjects, which are virtually unattested in RI (see Haegeman 1995/6 for Dutch and Rasetti 2000 for French).10 So, why is the distribution of strong subject DP’s less strictly constrained?

Pursuing the case analysis, we observe that there may be other ways to case mark a strong DP, for instance by assigning it a default case in an otherwise caseless environment. This may be the mechanism involved in case marking DP’s in hanging topic position (Cinque 1999 and much related literature), and possibly in special non-finite constructions such as English Me do that?! Never! So, in cases with overt subjects with RIs the child may be exploring such a default case assignment mechanism, permitting overt subjects in some cases. Such a mechanism would not suffice to satisfy the stricter licensing requirement of weak subjects (which in fact are not legitimate in Hanging Topic and similar special positions). Moreover, it would give rise to a clearly distinct, and weaker, proportion of overt subjects than in finite environments, which can rely on the normal nominative assignment mechanism, hence do not require any special assumption by the language learner on default case assignment.

Whatever the merits of these speculations, it seems to us that the sharp difference in the proportion of overt and null subjects in full clauses and clauses with missing aspectual marker, as illustrated in Figure 2, supports the hypothesis that structures with missing aspectual marking are the language specific manifestation of RIs in JC. This interpretation is reinforced by the fact that the observed difference in subject drop is in line with similar differences between finite and RIs environments in other child languages.

3.4 Root infinitives, declaratives and interrogatives

As pointed out in section 1.2, the truncation approach predicts a sharp contrast between declaratives and wh questions: the former, not involving any overt marker in the higher layers of the clause, should be consistent with RIs, whereas the latter, necessarily involving the C-system to host the wh-phrase, should be inconsistent with RIs. This selective compatibility of RIs has been observed in Child Dutch (Haegeman 1995a), Child French (Crisma 1992), Child German (Clahsen, Kursawe & Penke 1996), Child Swedish (Josefsson 2002), among others. As detailed in Table 4, a similar strong asymmetry between declaratives and wh-questions is observed in child JC. While there are 39.9 % of structures with target inconsistent missing aspect among declaratives, only 6.5% structures with missing aspect were produced with overt wh-interrogatives.11 This sharp difference is expected if structures with missing aspect are to be assimilated to RIs, and under the truncation approach.

RIs with Declaratives and Interrogatives.

| Informants | RIs indeclaratives | % | RIs in yes/no interrogatives | % | RIs inovert wh-interrogatives | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | 437/777 | 56.2 | 11/19 | 57.9 | 1/6 | 16.7 |

| ALA | 350/877 | 39.9 | 23/40 | 57.5 | 0/25 | 0.0 |

| RJU | 392/960 | 40.8 | 17/47 | 36.2 | 4/50 | 8.0 |

| TYA | 239/480 | 49.8 | 3/3 | 100.0 | 0/5 | 0.0 |

| KEM | 591/1714 | 34.5 | 24/50 | 48.0 | 0/4 | 0.0 |

| SHU | 174/660 | 26.3 | 13/55 | 23.6 | 6/79 | 7.6 |

| Total | 2183/5468 | 39.9 | 91/214 | 42.5 | 11/169 | 6.5 |

Can the truncation hypothesis explain the fact that the proportion of yes-no questions with missing aspect roughly corresponds to the proportion of declaratives with missing aspect, namely, 42.5%? On the face of it, these data present a problem. Although main yes-no questions in JC are solely marked by an intonational contour and do not seem to overtly engage the left periphery, their interpretation as questions (and the licensing of the intonational contour) need to be structurally anchored. One possibility that comes to mind is that children can merge a (null) yes-no question operator within the structure of the IP. Such structures would then resemble truncated or fragment yes-no questions in adult language. However, while adult sentences like “sleeping?” or “coming?” are interpretively restricted, (for example, they all require their null subject to be the addressee), children may have recourse to the formal strategy of marking fragments as questions in interpretively less restricted environments. That the marker of yes-no questions may be expressed within the IP gains additional plausibility in view of the fact that some adult languages morphologically mark yes-no questions in an IP-internal position. For instance, the –ti interrogative marker found in Valdôtain dialects in sentences like Tu pékè-ti? ‘Are you eating?’ (Fénis dialect; see Ermacora (in progress) for discussion) seems to have such characteristics.

These data, as mapped out in Figure 3, clearly indicate that there is a structural difference between the productions of RIs in contexts requiring the overt projection of the CP as opposed to contexts where the CP can be truncated.

The following data provides examples of root infinitives in yes/no interrogatives (41–46), and wh-questions with overt subjects (47–52).

- (41)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- plie

- play

- wid

- with

- i?

- 3SG

- (ALA 1;11)

- “Are you playing with it?”

- (42)

- I

- 3SG

- Ø

- Ø

- jomp

- jump

- aaf?

- off

- (COL 2;08)

- “Is it jumping off?”

- (43)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- taak

- talk

- pan

- on

- i

- DEF

- puon?

- phone

- (SHU 2;03)

- “Is she talking on the phone?”

- (44)

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- mash-op

- destroy

- i?

- 3SG

- (KEM 2;03)

- “Am I going to destroy it?”

- (45)

- Faiya

- fire

- Ø

- Ø

- born

- burn

- yo?

- 2SG

- (RJU 2;02)

- “Is the fire going to burn you?”

- (46)

- Moesha

- Moesha

- Ø

- Ø

- koom

- comb

- i

- 3SG

- fi

- for

- mi?

- 1SG

- (TYA 2;10)

- “Is Moesha going to comb it for me?”

- (47)

- Wa

- what

- shi

- 3SG

- a

- PROG

- du?

- do

- (RJU 2;07)

- “What is she doing?”

- (48)

- We

- where

- im

- 3SG

- a

- PROG

- go

- go

- mami?

- mommy

- (KEM 2;10)

- “Where is he going mommy?”

- (49)

- A

- FOC

- uu

- who

- a

- PROG

- kaal

- call

- mi?

- 1SG

- (COL 2;07)

- “Who is it that is calling me?”

- (50)

- We

- where

- mi

- 1SG

- a_go

- PROS

- put

- put

- mi

- 1SG

- fut?

- foot

- (ALA 2;07)

- “Where am I going to put my foot?”

- (51)

- We

- where

- yu

- 2SG

- gwain

- PROS

- sidong?

- sit

- (SHU 2;09)

- “Where are you going to sit?”

- (52)

- Wa

- what

- mi

- 1SG

- a_go

- PROS

- kola

- colour

- wid

- with

- nou?

- now

- (TYA 3;01)

- “What am I going to colour with now?”

The 11 root infinitives found in wh-questions with overt wh-elements are provided in examples (53–63).

- (53)

- Wa

- what

- im

- 3SG

- Ø

- Ø

- du?

- do

- (RJU 2;10)

- “What is he doing?”

- (54)

- Wa

- what

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- Ø

- du?

- do

- (COL 2;05)

- “What is she doing?”

- (55)

- Wa

- what

- i

- 3SG

- Ø

- Ø

- du?

- do

- (RJU 2;08)

- “What is he doing?”

- (56)

- Wat

- what

- yu

- 2SG

- Ø

- Ø

- du?

- do

- (SHU 2;07)

- “What are you doing?”

- (57)

- Wa

- what

- Ø

- 3SG

- Ø

- Ø

- tek

- take

- dem

- them

- we

- away

- fa?

- for

- (RJU 2;11)

- “Why is he going to take them away?”

- (58)

- Wich

- which

- paat

- part

- im

- 3SG

- Ø

- Ø

- paak

- park

- mi

- 1SG

- baisikl?

- bicycle

- (RJU 2;11)

- “Where is he going to park my bicycle?”

- (59)

- Uu

- who

- a

- 1SG

- Ø

- Ø

- jraa

- draw

- nou?

- now

- (SHU 2;09)

- “Who am I going to draw now?”

- (60)

- We

- what

- yu

- 2SG

- Ø

- Ø

- du

- do

- nou?

- now

- (SHU 3;00)

- “What are you doing now?”

- (61)

- Ou

- how

- i

- 3SG

- Ø

- Ø

- ron

- run

- pan

- on

- mi?

- 1SG

- (SHU 3;01)

- “How is it going to run on me?”

- (62)

- We

- where

- yu

- 2SG

- Ø

- Ø

- plat?

- plait

- (SHU 3;02)

- “Where are you going to plait?”

- (63)

- Ou

- how

- yu

- 2SG

- Ø

- Ø

- fiks

- fix

- i

- 3SG

- bak?

- back

- (SHU 3;04)

- “How are you going to fix it back?”

4 Discussion and conclusion

In inflectional languages with a distinct infinitival inflection (and if other conditions are met), a root infinitive stage is systematically observed in development, with the infinitival form of the verb occurring in main declarative clauses, instead of the adult-like finite inflected form. Such root infinitival forms, studied in detail in child French, German, Dutch, and other child languages, occur in specific structural environments and manifest special distributional constraints. One important constraint is that they are consistent with declaratives, but not with wh-questions. This structural property straightforwardly follows from Truncation, but remains unpredicted by various alternative approaches put forth to account for RI, namely ATOM (Schuetze & Wexler 1996), the UCC (Wexler 1998), the Variational Learning Model (Legate & Yang 2007) and models stipulating uninterpretable tense to emerge late (Tsimpli 2005).12 That RIs are banned in wh-contexts in fact motivated the truncation approach: if RIs are structural fragments, structures truncated under T, one expects that all external structural layers will be omitted or be unpronounced as per the spell-out approach, including the CP system. As this system is required in wh-questions to host the operator, truncation explains the incompatibility of RIs with wh-constructions. Along similar lines, this approach explains the incompatibility of RIs with properties requiring the T layer or higher layers in the clausal structure (subject clitics, functional verbs, etc.: Rizzi 1993/4).

In this article we have addressed the question of the existence of an RIs stage in JC, and of the form that RIs constructions could take in a language in which lexical verbs are morphologically invariable. Such invariable verbs occur in the adult grammar preceded by functional heads expressing temporal, modal and aspectual properties and organized along the lines described in Durrleman (2008), in conformity with the general functional sequences uncovered in Cinque (1999). Under the truncation model, we would therefore expect the language-specific variety of RIs to take the form of a bare lexical verb stripped of the functional specifications that would be required in the target grammar. In this article we have focused on aspect, particularly on the frequent and rapidly acquired specifications of progressive and prospective aspect. We observed, in the natural production corpus under examination (1,08–3,04), that in the contexts which would require the aspectual specifications, the progressive marker is omitted in 1313 cases out of 4745 (28%), and the prospective marker is omitted in 1110 cases out of 3007 (37%). Omission errors were abundant, but commission errors were virtually absent, suggesting that children had figured out the interpretive content of the aspect markers. We interpreted the observed target-inconsistent omissions as the language-specific variety of the RIs construction.

This interpretation was supported by the observation that the target-inconsistent bare forms obey structural constraints typical of RI. In particular, they are robustly attested in declaratives (39.9% of the relevant cases), but very rare in post-wh environments (6.5% of the relevant cases). This sharp difference is expected if such bare forms are the language-specific variety of RIs, under the truncation analysis. This line of reasoning also led us to verify the occurrence of RIs in yes-no questions. As the language does not structurally mark yes-no questions by special markers or movements involving the CP system, one may expect such questions to pattern with declaratives, rather than with wh-questions, which necessarily involve the overt CP layer. In fact, bare forms are about as frequent in yes–no questions (42.5%) as in declaratives (39.9%), whereas in wh-questions they are sharply less frequent, as we have seen (6.5%).

Target-inconsistent bare forms also pattern with RIs in connection with the distribution of overt and null subjects. De Lisser et al. (2016) show that the acquisition of JC is characterized by a clear phase of subject omission in finite clauses, much as in the acquisition of other non-null subject languages (see Guasti 2016 for a synthesis of the relevant literature). By comparing the results of De Lisser et al. (2016) with the results of the present paper, we observe that null and overt subjects occur in both finite and non-finite environments, but in clearly different proportions: over the periods considered, the core of which is the third year of life, overt subjects are the preponderant case in finite environments, whereas null subjects are the preponderant case in non-finite environments (Figure 2). This is roughly the same imbalance which has been observed across child languages in subject omission in finite and RIs environments (see Table 3). In this respect too, the bare verbal forms with missing aspectual specification in child JC pattern with RIs cross-linguistically, thus reinforcing the hypothesis that they are the language-specific manifestation of the RIs construction.

Pursuing the comparison with the results of De Lisser et al. (2016) we have also noticed that the phenomena of early subject drop and bare verbs with missing aspect follow very similar developmental courses, with theirs peaks in the very first files and with a constant decrease in the course of the third year of life. This parallel pattern is expected under the hypothesis that a single underlying factor, truncation, is involved.

4.1 Growing trees and truncation

In recent work, Friedmann, Belletti and Rizzi (this volume) have worked out a “growing trees” approach to language development by which learners’ productions start with minimal structures in a bottom up fashion, and then higher zones get added on top of the structure as development proceeds, following the hierarchical organization uncovered by cartographic work. This approach is implemented in Friedmann, Belletti and Rizzi (this volume) to capture the developmental stages of the acquisition of different A’-constructions in Hebrew. The growing trees approach is distinct from the truncation idea. The fundamental difference has to do with optionality. In the growing trees approach, at a given stage a higher layer (for instance a certain zone of the CP-system) is systematically missing in the child’s representation, whereas under truncation, a higher layer is accessible to the child, it may be present in a representation, but it may optionally be truncated.

The two ideas are clearly distinct, but not incompatible. If we try to put them together, the possibility which suggests itself is a three-stage developmental sequence. In the first stage, the upper layer under consideration is always absent, the relevant subtree has not “grown” yet. In the second stage the layer becomes available to the child, but it can be truncated: we thus have the period of optionality which is typically observed in the course of the third year of life. In the third stage, adult-like, the layer becomes obligatory. In this way, the two ideas can coexist, and in fact, if properly integrated, can become a useful tool to look at developmental effects.

Throughout the third year of life, we have observed in our corpus study of child JC that aspectually marked forms alternate with bare verbal forms in contexts in which special aspectual interpretations are required. This alternation is expected under the truncation approach which we have adopted. The optional truncation analysis is also consistent with the findings in Friedmann, Belletti and Rizzi, which assumes an initial stage in which the complete IP structure is available to the child, whereas different left-peripheral zones must grow.

We will not undertake here a more detailed analysis of the possible relevance of a division of labor between growing trees and truncation. Let us simply observe, in closing, that the very first relevant cases of verbal forms in contexts requiring progressive or prospective interpretations are bare forms (Table 1), and a robust alternation between bare and marked forms starts only later. This may suggest the possibility that the initial recordings capture a phase in which the relevant aspectual zones have not grown yet. At later points, such zones become available to the child, and can be expressed in some structures and undergo truncation in other structures. We will not try to develop this hint here, and will leave for further work a systematic assessment of the integration of growing trees and truncation into a single coherent model of the development of the clausal structure.

In conclusion, the acquisition of JC manifests a well-identifiable RIs phase, in which bare verbal forms can occur without the aspectual markers which would be required by the adult grammar. Our conclusion thus concurs with Pratas and Hyams’ (2009) analysis of Capeverdean Creole in showing that specific varieties of the RIs construction can be found in the development of Creole languages. We have shown that certain basic properties characterizing children’s use of verbal forms with omitted aspect markers are naturally explainable through the truncation approach, applied here to the language specific variety of the RI construction.

Appendix 1: Production of RIs with aspectual interpretations.

| AGE (mths) | Omitted Aspect | Overt Aspect | Total Aspect | % Root infinitives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1;8.0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| 1;8.5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 100 |

| 1;9.0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| 1;9.5 | 25 | 2 | 27 | 93 |

| 1;10.0 | 19 | 3 | 22 | 86 |

| 1;10.5 | 30 | 8 | 38 | 79 |

| 1;11.0 | 63 | 13 | 76 | 83 |

| 1;11.5 | 47 | 12 | 59 | 80 |

| 2;0.0 | 40 | 15 | 55 | 73 |

| 2;0.5 | 73 | 26 | 99 | 74 |

| 2;1.0 | 108 | 18 | 126 | 86 |

| 2;1.5 | 119 | 37 | 156 | 76 |

| 2;2.0 | 121 | 89 | 210 | 58 |

| 2;2.5 | 134 | 60 | 194 | 69 |

| 2;3.0 | 108 | 84 | 192 | 56 |

| 2;3.5 | 130 | 78 | 208 | 63 |

| 2;4.0 | 88 | 80 | 168 | 52 |

| 2;4.5 | 108 | 103 | 211 | 51 |

| 2;5.0 | 89 | 50 | 139 | 64 |

| 2;5.5 | 135 | 137 | 272 | 50 |

| 2;6.0 | 68 | 110 | 178 | 38 |

| 2;6.5 | 75 | 141 | 216 | 35 |

| 2;7.0 | 70 | 276 | 346 | 20 |

| 2;7.5 | 81 | 220 | 301 | 27 |

| 2;8.0 | 92 | 257 | 349 | 26 |

| 2;8.5 | 47 | 294 | 341 | 14 |

| 2;9.0 | 55 | 227 | 282 | 20 |

| 2;9.5 | 75 | 203 | 278 | 27 |

| 2;10.0 | 48 | 197 | 245 | 20 |

| 2;10.5 | 37 | 213 | 250 | 15 |

| 2;11.0 | 54 | 238 | 292 | 18 |

| 2;11.5 | 39 | 170 | 209 | 19 |

| 3;0.0 | 46 | 303 | 349 | 13 |

| 3;0.5 | 36 | 273 | 309 | 12 |

| 3;1.0 | 43 | 298 | 341 | 13 |

| 3;1.5 | 29 | 251 | 280 | 10 |

| 3;2.0 | 30 | 249 | 279 | 11 |

| 3;2.5 | 23 | 216 | 239 | 10 |

| 3;3.0 | 15 | 177 | 192 | 8 |

| 3;3.5 | 8 | 103 | 111 | 7 |

| 3;4.0 | 3 | 59 | 62 | 5 |

| 3;4.5 | 8 | 39 | 47 | 17 |

Abbreviations

Ø – Null

1SG – First person singular

2SG – Second person singular

3SG – Third person singular

3PL – Third person plural

DEF – Definite determiner

FOC – Focus marker

INDEF – Indefinite determiner

LOC – Locative

NEG – Negation marker

PAST – Past tense

POSS – Possessive pronoun

PROG – Progressive aspect

PROS – Prospective aspect

Q – Quantifier

Notes

- Here we are not referring to instances where the bare verb is permitted in adult utterances, as is the case with special temporal-aspectual interpretations (Bailey, 1966; Patrick, 2007; Durrleman, 2008, 2015). See below. [^]

- Unmarked non-stative verbs can also be interpreted as habitual, depending on the context, for e.g. im ron can be “he ran” or “he runs (habitually)”. See Bailey (1966), Patrick (2007) and Durrleman (2008; 2015) for details. [^]

- There are different forms of the progressive and prospective aspect markers in JC, possibly due to the variation along the continuum. [^]

- RIs should also be incompatible with the copula and with auxiliaries, if these are generated in T (or are intimately connected to T, for instance because they have to check T features), and should be incompatible with certain types of overt subjects, such as weak pronominal subjects in French, or in Dutch, which are licensed in the higher layers of the inflectional space (as weak pronouns in Spec-Agr, according to Cardinaletti & Starke 1999: see Haegeman, 1995 on Dutch; Rasetti, 2000 on French). JC has no weak pronominal subjects, no overt auxiliary verbs and the copula is sometimes optional, so these points are left aside here. We also leave for future work the issue of the roughly cotemporal disappearance of RIs and root subject drop. Indeed if truncation at different structural levels underlies both RIs and root subject drop in early systems, as argued in Rizzi (1993/4 1995), one would expect the two properties to disappear about at the same time in development (Hamann & Plunkett 1998; Rizzi 2000; Rasetti 2000b; among others). [^]

- JC does not use wh in-situ as a strategy of interrogation and there are virtually no cases of wh in-situ in the current corpus (see De Lisser 2015). This confirms the view that the parameter distinguishing in-situ and not-in-situ languages is fixed early on (see Guasti 2016 for discussion). [^]

- From the total occurrences of the progressive marker, only three examples were detected where the progressive was incorrectly used, as detailed in examples (i) – (iii). Note also that all three cases are errors involving the marker of negation plus the progressive marker, instead of the bare negative marker.

- (i)

- *Yo

- 2SG

- naa

- NEG~PROG

- niem

- name

- no

- NEG

- Tamir,

- Tamir

- yo

- 2SG

- niem

- name

- Kiisha.

- Keisha

- (ALA 2;08)

- “Your name is not Tamir, your name is Keisha.”

- (ii)

- *A

- 1SG

- naa

- NEG~PROG

- lov

- love

- im,

- 3SG

- a

- 1SG

- noo

- NEG

- lov

- love

- Ø.

- Ø

- (COL 2;07)

- “I don’t love him; I don’t love (him).”

Upon close inspection, however, it appears that an analysis of NEG + PROG may not be warranted in these cases: It may well be that the child is intending to simply express NEG, and hasn’t yet determined that naa in fact also encodes PROG. This is likely because in some cases, NEG is indeed expressed as naa, as in the expression ‘naa sa’: ‘no Sir’. [^]- (iii)

- *Im

- 3SG

- naa

- NEG~PROG

- ha

- have

- noo

- NEG

- tiit.

- teeth

- (COL 2;09)

- “He doesn’t have any teeth.”

- The general pattern observed in other languages is that statives do not normally occur as root infinitives (Ferdinand 1996; Wijnen 1997; Hoekstra & Hyams 1998; Van Gelderen & Van der Meulen 1998; Berger-Morales, Salustri & Gilkerson 2005). For a comparative analysis, only non-stative utterances have been included in the subsequent analyses of RIs in JC. Additionally, non-stative utterances with null-wh elements were excluded. The figures will therefore be different from that in Table 1 as Table 1 details the total production of progressive and prospective utterances (marked or deduced from context, stative and non-stative) in all environments. [^]

- Recall that the aspectual interpretation of each example was evaluated and determined by a native speaker in the context in which the example occurred. [^]

- The figures presented here do not correspond to those in De Lisser et al. (2016) as that analysis was restricted to children younger than 35 months, when null subjects were robustly manifested in the corpus. Additionally, De Lisser et al. (2016) included both finite and infinitival declarative clauses and stative and non-stative verbs. The present analysis separates the finite and infinitival declaratives and includes only non-stative declaratives up to 40 months of age. [^]

- JC, contrary to e.g., French, does not have a distinct morphological paradigm for weak pronouns. [^]

- For a coherent comparison, like for declarative clauses, only non-stative interrogative utterances were included in this analysis. [^]

- The Aspectual Anchoring Hypothesis (Hyams 2007, 2011) addresses the way in which RIs receive a temporal-aspectual interpretation, a point which is not explicitly addressed by truncation. We leave open here the question of whether AAH and truncation may be integrated. [^]

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Bailey, Beryl. 1966. Jamaican Creole Syntax: A Transformational Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Berger-Morales, Julia & Salustri, Manola & Gilkerson, Jill. 2005. Root infinitives in the spontaneous speech of two bilingual children: Evidence for separate grammatical systems. In Cohen, James & McAlister, Kara T. & Rolstad, Kellie & MacSwan, Jeff (eds.), ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, 296–305. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Bickerton, Derek. 1981. Roots of Language. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers.

Cardinaletti, Anna & Starke, Michal. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In van Riemsdijk, Henk (ed.), Clitics in the languages of Europe, 145–233. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110804010.145

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures in Government and Binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clahsen, Harald & Kursawe, Claudia & Penke, Martina. 1996. Introducing CP: Wh-questions and subordinate clauses in German child language. In Koster, Charlotte & Wijnen, Frank (eds.), Proceedings of the 1995 Groningen Assembly on Language Acquisition. GALA: Groningen, The Netherlands.

Crisma, Paola. 1992. On the acquisition of Wh-questions in French. Geneva Generative Papers 0.1–2: 115–122.

De Lisser, Tamirand. 2015. The acquisition of Jamaican Creole: The emergence and transformation of early syntactic systems. Thèse de doctorat: Univ. Genève, no.L.835.

De Lisser, Tamirand & Durrleman, Stephanie & Rizzi, Luigi & Shlonsky, Ur. 2014. The acquisition of Jamaican Creole: A research project. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 36. 83–101.

De Lisser, Tamirand & Durrleman, Stephanie & Rizzi, Luigi & Shlonsky, Ur. 2016. The acquisition of Jamaican Creole: Null subject phenomenon. Language Acquisition 23. 261–292. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2015.1115049

De Lisser, Tamirand & Durrleman, Stephanie & Shlonsky, Ur & Rizzi, Luigi. 2017. The acquisition of tense, modal and aspect markers in Jamaican Creole. Journal of Child Language Acquisition and Development 5(4). 219–255.

Durrleman, Stephanie. 2008. The Syntax of Jamaican Creole: A cartographic perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.127

Durrleman, Stephanie. 2015. Nominal architecture in Jamaican Creole. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 30(2). 265–306. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/jpcl.30.2.03dur

Erbaugh, Mary. 1992. The acquisition of Mandarin. In Slobin, Dan Isaac (ed.), The Crosslinguistic Study of Language Acquisition 3. 373–455. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ermacora, Laure. In progress. Issues in Francoprovençal morphosyntax: A comparative approach. Thèse de doctorat: Univ. Genève.

Ferdinand, Renata Astrid. 1996. The acquisition of the subject in French. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, HIL/Leiden University.

Garcia, Carlos Buesa. 2007. Early root infinitives in a null-subject language: A longitudinal case study of a Spanish child. In Belikova, Alyona & Meroni, Luisa & Umeda, Mari (eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America (GALANA), 39–50. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Guasti, Maria Teresa. 2016. Language Acquisition: The growth of grammar. Second edition. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Haegeman, Liliane. 1995. Root infinitives, tense, and truncated structures in Dutch. Language Acquisition 4(3). 205–255. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327817la0403_2

Hamann, Cornelia & Plunkett, Kim. 1998. Subjectless sentences in child Danish. Cognition 69. 35–72. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(98)00059-6

Hoekstra, Teun & Hyams, Nina. 1998. Aspects of root infinitives. Lingua 106. 81–112. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(98)00030-8

Hyams, Nina. 2007. Aspectual Effects on Interpretation in Early Grammar. Language Acquisition 14.3. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10489220701470992

Hyams, Nina. 2011. Missing Subjects in Early Child Language. In De Villiers, Jill & Roeper, Thomas (eds.), Handbook of Language Acquisition Theory in Generative Grammar. The Netherlands: Kluwer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1688-9_2

Josefsson, Gunlog. 2002. The use and function of nonfinite root clauses in Swedish child language. Language Acquisition 10(4). 273–320. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327817LA1004_1

Legate, Julie Anne & Yang, Charles. 2007. Morphosyntactic Learning and the Development of Tense. Language Acquisition 14(3). 315–344. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10489220701471081

Patrick, Peter. 2007. JC Jamaican Patwa (Creole English). Creolica.

Pratas, Fernanda & Hyams, Nina. 2009. Introduction to the acquisition of finiteness in Capeverdean. In Costa, Joao & Castro, Ana & Lobo, Maria & Pratas, Fernanda (eds.), Language Acquisition and Development – Proceedings of GALANA 2009, 378–390. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Rasetti, Lucienne. 2000. Interpretive and formal properties of null subjects in early French. Generative Grammar in Geneva 1. 241–274.

Rasetti, Lucienne. 2000b. Null subjects and root infinitives in the child grammar of French. In Friedemann, Marc-Ariel & Rizzi, Luigi (eds.), The Acquisition of Syntax: Studies in Comparative Developmental Linguistics, 236–268. London: Longman. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315839899-9

Rizzi, Luigi. 1993/1994. Some notes on linguistic theory and language development: the case of root infinitives. Language Acquisition 3(4). 371–393. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327817la0304_2

Rizzi, Luigi. 2000. Comparative Syntax and Language Acquisition. New York: Routledge.

Santelmann, Lynn. 1995. The acquisition of verb second grammar in child Swedish. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Cornell University.

Schuetze, Carson & Wexler, Kenneth. 1996. Subject case licensing and English root infinitives. In Stringfellow, Andy & Cahana-Amitay, Dalia & Hughes, Elizabeth & Zukowski, Andrea (eds.), Proceedings of the Annual 20th Boston University Conference on Language Development, 670–681. Somerville, MA.: Cascadilla Press.

Shirai, Yasuhiro & Andersen, Roger. 1995. The acquisition of tense-aspect morphology: A prototype account. Language 71(4). 743–762. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/415743

Sugiura, Wataru, Sano, Tetsuya & Shimada, Hiroyuki. 2016. Are there root infinitives analogues in child Japanese? In Perkins, Laurel & Dudley, Rachel & Gerard, Juliana & Hitczenko, Kasia (eds.), Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America (GALANA 2015), 131–139. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Tsimpli, Ianthi-Maria. 2005. Peripheral positions in early Greek. In Stavrou, Melita & Terzi, Arhonto (eds.), Advances in Greek Generative Syntax, Linguistics Today, 179–216. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.76.08tsi

Van Gelderen, Veronique & Van der Meulen, Ineke. 1998. Root infinitives in Russian: Evidence from acquisition. Term Paper, Leiden University.

Varlokosta, Spyridoula & Vainikka, Anne & Rohrbacher, Bernhard. 1996. Root infinitives without infinitives. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD 20), 816–827. Somerville MA: Cascadilla Press.

Wexler, Kenneth. 1994. Optional infinitives, head movement, and the economy of derivation in child language. In Lightfoot, David & Hornstein, Norbert (eds.), Verb Movement, 305–350. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wexler, Kenneth. 1998. Very early parameter setting and the unique checking constraint: A new explanation of the optional infinitive stage. Lingua 106. 23–79. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(98)00029-1

Wijnen, Frank. 1997. Temporal reference and eventivity in root iVARnfinitivals. MIT Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 12(May), 1–25.