1. Introduction

In this paper, I focus on Asturian middle-passive constructions,1 i.e. generic predicates denoting intrinsic properties of their notional object, syntactically realized as their grammatical subject (Ackema & Schoorlemmer 2006, inter alia). Specifically, I discuss the apparent optionality of the reflexive pronoun se in these sentences (1a), which is otherwise obligatory in other Ibero-Romance languages such as Spanish (1b) or Catalan (1c).

- (1)

- Asturian (GLLA 2001: 355)

- a.

- Les

- the

- fueyes

- leaves

- mueyen(se)

- wet.REFL

- col

- with.the

- orbayu.

- light rain

- ‘Leaves get wet/are wetted with the light rain.’

- Spanish

- b.

- Las

- the

- hojas

- leaves

- *(se)

- REFL

- mojan

- wet

- con

- with

- la

- the

- lluvia

- rain

- ligera.

- light

- ‘Leaves get wet/are wetted with the light rain.’

- Catalan

- c.

- Les

- the

- fulles

- leaves

- *(es)

- REFL

- mullen

- wet

- amb

- with

- la

- the

- pluja

- rain

- lleugera.

- light

- ‘Leaves get wet/are wetted with the light rain.’

The GLLA provides a heterogeneous description of structures that can convey the middle reading, and whose classification criterion is whether the reflexive pronoun is required or not. Specifically, when referring to reflexively marked passives –and consequently middle-passive constructions like (1a)– the Academy explains that these are intransitive constructions in which “un pronome se vien a torgar la posibilidá d’apaecer del complementu direutu; esi pronome ta, entós, en llugar del complementu direutu” (ALLA 2001: 353) [‘a se pronoun thwarts the possibility of the direct object to appear; therefore, such pronoun occurs instead of the direct object;’ translation by the author]. Moreover, the GLLA points out that in these structures “ye frecuente que l’usu del pronome reflexivu resulte potestativu” (ALLA 2001: 355) [‘the use of the reflexive pronoun is frequently optional;’ translation by the author]. However, upon closer examination, it is easy to demonstrate that such optionality does not apply across the board. For instance, when these contexts contain verbs denoting an activity or accomplishment that notionally require the participation of an agent/experiencer in the event (e.g. lleer, ‘to read’), Asturian patterns with other Romance languages and the reflexive becomes compulsory, as shown in (2):

- (2)

- Asturian

- a.

- Les

- the

- noveles

- novels

- de

- of

- misteriu

- mystery

- lléen*(se)

- read-REFL

- con

- with

- facilidá.

- easiness

- ‘Mystery novels read easily.’

- Spanish

- b.

- Las

- the

- novelas

- novels

- de

- of

- misterio

- mystery

- *(se)

- REFL

- leen

- read

- con

- with

- facilidad.

- easiness

- ‘Mystery novels read easily.’

Here, I will argue that the presence of the reflexive clitic in sentences like (1a) is not optional; instead, I link it to the interpretation of an implicit generic agent in the event, which can be rephrased as anyone (e.g. anyone can read mystery novels easily, cf. (2)). I propose that se spells out a passive Voice projection in the structure (Marantz 1984; Kratzer 1996; Schäfer 2008; Suárez-Palma 2019; 2020) which contributes to the agentive reading, giving rise to a generic se-passive (3a). Moreover, I provide evidence showing that the se-less counterpart in Asturian is in fact non-agentive because they lack Voice; in other words, this variant is a generic inchoative/anticausative configuration (3b).

| (3) | a. | Generic se-passive |

| Les fueyes muéyense col orbayu. | ||

| [VoiceP se [vP v [VP moyar [DP les fueyes]]]] | ||

| b. | Generic inchoative | |

| Les fueyes mueyen col orbayu. | ||

| [vP v [VP moyar [DP les fueyes]]] |

Lastly, I explain that this phenomenon is subject to crosslinguistic influence. On the one hand, it is possible to find speakers who accept non-agentive middle contexts containing the reflexive clitic; I argue that this is due to the influence of Spanish, the dominant language in the region, which shows the presence of se in passive and numerous inchoative contexts.2 On the other hand, I present real instances of se-less non-agentive middle sentences in Asturian Spanish (AsturSp); this demonstrates that Asturian, in spite of being the minority language, has also exerted its influence over AsturSp, differentiating it from other dialects of Spanish.

The paper is structured as follows: in Section 2, I delve into de data and the analysis; specifically, §2.1 examines data from agentive and non-agentive Asturian middle sentences incorporating purpose clauses, and §2.2 discusses more evidence stemming from the interaction between these structures with dative arguments; §2.3 deals with middle contexts containing unaccusative verbs of movement, and §2.4 tackles crosslinguistic transfer between Asturian and Asturian Spanish. Finally, Section 3 provides the concluding remarks.

2. Analysis

2.1. Voice in Asturian middle-passives

A careful observation of data from middle-passives in Asturian reveals that the optionality of the reflexive clitic se in them is evident in contexts where a verb denoting a change of state or location occurs in them. These verbs may convey both an agentive and a non-agentive reading, as shown in the two possible English translations of the examples in (4); in other words, these verbs participate in the causative alternation (Schäfer 2009, inter alia).

- (4)

- a.

- Esi

- that

- pan

- bread

- esmigáya(se)

- crumbles.REFL

- fácil

- easy

- nes

- in-the.PL

- manes.

- hands

- Non-agentive: ‘That bread crumbles in your hands easily.’

- Agentive: ‘That bread is easy to crumble in one’s hands.’

- b.

- Los

- the

- barcos

- boats

- de

- of

- papel

- paper

- fúnden(se)

- sink.REFL

- rápido.

- fast

- Non-agentive: ‘Paper boats sink quickly.’

- Agentive: ‘Paper boats are quick to sink.’

- c.

- Esti

- this

- material

- material

- ruémpe(se)

- breaks.REFL

- fácil.

- easy

- Non-agentive: ‘This material breaks easily.’

- Agentive: ‘This material is easy to break.’

The non-agentive reading in these sentences can be enhanced by means of the insertion of a PP like por sí mesmu (‘by itself’), which can only be licensed in non-agentive contexts. Interestingly, for most speakers,3 the presence of such PP necessarily requires the omission of the reflexive pronoun.

- (5)

- Esti

- this

- pan

- bread

- esmigaya(*?se)

- crumbles.REFL

- fácil

- easy

- por

- by

- sí mesmu.

- itself

- ‘This bread crumbles easily by itself.’

On the other hand, the implicitly encoded generic agent in the agentive interpretation makes it possible for these structures to control into a purpose clause (6), which has been traditionally taken as evidence for the presence of implicit arguments in passives (cf. Bhatt & Pancheva 2006). Crucially, in that case, the reflexive pronoun must be present.

- (6)

- Esti

- this

- pan

- bread

- esmigáya*(se)

- crumbles.REFL

- fácil

- easy

- pa

- for

- empanar

- bread

- cachopos.4

- cachopos

- ‘This bread is easy to crumble in order to make cachopos.’

Furthermore, when Asturian middle-passive sentences contain predicates expressing activities or accomplishments, i.e. events notionally requiring the participation of an agent or experiencer, the omission of the reflexive becomes ungrammatical (7); besides, these verbs only allow an agentive interpretation, which prevents them from licensing the PP por sí mesmu (‘by itself’) in these contexts, yet they admit a purpose clause.

- (7)

- a.

- Los

- the

- poemes

- poems

- d’amor

- of-love

- escríben*(se)

- write.REFL

- fácil

- fast

- (*por

- by

- sí mesmos) /

- themselves.M

- pa

- for

- namorar

- charm

- a

- to

- daquien.

- someone

- ‘Love poems are easy to write in order to win someone’s heart.’

- b.

- Les

- the

- noveles

- novels

- de

- of

- misteriu

- mystery

- lléen*(se)

- read.REFL

- con

- with

- facilidá

- ease

- (*por

- by

- sí mesmes) /

- themselves.F

- pa

- for

- entretenese.

- entertain.REFL

- ‘Mystery novels read easily in order to kill time.’

- c.

- El

- the

- cascu

- quarter

- históricu

- historic

- d’Avilés

- of-Avilés

- percuérre*(se)

- go-through.REFL

- fácil

- easy

- (*por

- by

- sí mesmu) /

- itself.M

- pa

- for

- conocer

- know

- la

- the

- so

- its

- hestoria.

- history

- ‘Avilés’ historic quarter is easy to visit in order to learn about its history.’

Considering the data above, it seems appropriate to tie the presence of se in Asturian middle-passives to the interpretation of a generic agent participating in the event. In structural terms, this can be accounted for by arguing that only the agentive version of middle sentences projects a Voice head which would normally introduce an external argument, yet it is passivized and spelled out by the reflexive clitic pronoun se in Asturian (Schäfer 2008; Suárez-Palma 2019; 2020; 2021). This configuration is indeed a generic se-passive construction.

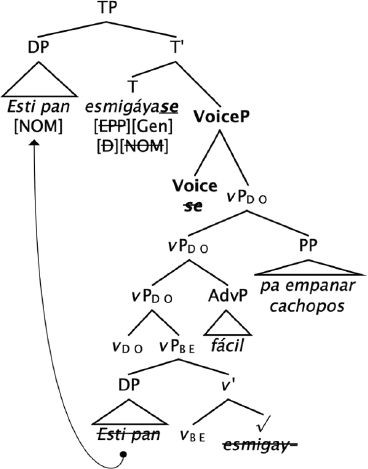

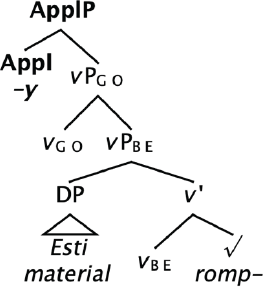

The analysis presented here relies on Cuervo’s (2003) typology of verbalizing heads; this linguist proposes three different types of event introducers/verbalizing heads, each corresponding to a simple eventive structure. Thus, activities (e.g. lleer, ‘to read’) are verbalized by vDO; verbs of change or happening (e.g. asoceder, ‘to happen’) by vGO; and finally, states and existentials (e.g. tar cansáu, ‘to be tired’) by vBE. Moreover, these events may combine with each other giving rise to complex structures such as causatives (e.g. Florinda quemó les fabes, ‘Florinda burnt the beans’), through the combination of an activity verbalizing head and stative one denoting the resulting state (vDO + vBE), or inchoatives (e.g. quemaron les fabes, ‘the beans burned’), by means of clustering a dynamic subevent of change and a stative one (vGO + vBE). Given this, the derivation of the generic se-passive in (6) is shown in (8).

| (8) | a. | Esti pan esmigáyase fácil pa empanar cachopos. |

| b. |  |

Because (8a) is an agentive structure entailing a resulting state, the derivation in (8b) must comprise an activity subevent (vDO) that triggers the change of state process until it reaches a particular end state (vBE), i.e. the state of being crumbled in this case. The combination of these two verbalizing heads generates a causative configuration. The locus for the agentive reading is the Voice head merging on top of vDO, which would normally introduce an external argument in the derivation. Here, however, the reflexive pronoun se spells out the Voice head and renders it passive. The complement of vBE is the root esmigay-, which undergoes head movement until reaching To, and the internal argument esti pan sits in its specifier and is probed to SpecTP by To to satisfy its EPP feature, thus licensing nominative case. Following Suárez-Palma (2020), I assume that the generic interpretation is possible through the presence of a generic operator Gen in To.

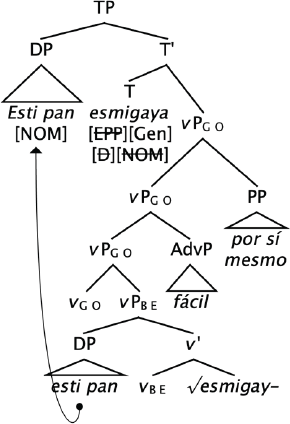

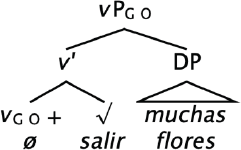

The agentless counterpart, on the other hand, does not host a VoiceP –hence the absence of se– and is therefore a generic unaccusative/inchoative structure. Thus, verbs like those in (7), which necessarily subcategorize for an external argument, can never appear without the reflexive in unaccusative contexts like middles; the same applies for the causative variant of the ones in (4). In other words, the presence of the reflexive clitic pronoun in middle sentences in Asturian is not optional, as it has been proposed in the literature thus far. Instead, it is determined by the type of verb entering the derivation, as well as by its idiosyncratic argument and event structures. The derivation for the non-agentive middle in (5) is given in (9).

| (9) | a. | Esti pan esmigaya fácil por sí mesmo. |

| b. |  |

What (9) shows is another bieventive structure comprising a subevent of change (vGO) and a stative one (vBE), which give rise to an inchoative construction. The root esmigay- is verbalized on its way to To. Finally, the internal argument raises to SpecTP to check the EPP features in To, becoming the sentence’s grammatical subject.5

In this section I have demonstrated that the reflexive and non-reflexive counterparts of Asturian middle constructions containing a change of state verb show structural differences. On the one hand, the se-variant entails an agentive reading which allows the insertion of a purpose clause, whose infinitive is controlled by the sentence’s implicit external argument; I explained this is due to the presence of a passive Voice projection spelled out by se in the derivation. On the other, the se-less variant is non-agentive because it lacks Voice –hence the absence of se–, which makes it possible to license a by itself PP. Next, I discuss additional data concerning Asturian middle sentences and datives which further support my claim that the presence of the reflexive in Asturian middle contexts involves the projection of Voice.

2.2. Asturian middle-passives and datives

In Suárez-Palma (2020), I develop an analysis of middle constructions in Spanish containing change-of-state predicates; I point out that Spanish middle contexts containing change-of-state verbs allow the insertion of a non-core dative argument which can be interpreted either as unintentional causer of the change of state (10.i), or as affected by the notional object’s resulting state whether it is internally (10.ii) or externally (10.iii) caused.6

- (10)

- Suárez-Palma (2020: 25)

- (A Sandrai)

- Sandra.DAT

- la

- the

- madera

- wood

- de

- of

- roble

- oak

- se

- REFL

- lei

- 3SG.DAT

- quema

- burns

- fácilmente.

- easily

- i. ‘Sandra unintentionally makes oak wood burn easily.’

- ii. ‘Oak wood burns easily, and Sandra is affected by it.’

- iii. ‘It is easy to burn Sandra’s wood, and she’s affected by it.’

Crucially, I show that the first two interpretations, i.e. unintentional causer (11.i) and affected by an internally caused event (11.ii), become unavailable should a purpose clause be inserted in the structure; in such case, the dative can only express affectation by an externally caused change of state (11.iii). The infinitive in such prepositional phrase is controlled by the implicit generic agent in the sentence –instantiated by means of the reflexive pronoun se– and not by the dative, as shown in (11). It is also the participation of such generic agent in the event that rules out the interpretation of the change of state being internally caused.

- (11)

- Suárez-Palma (2020: 25)

- (A Sandrai,)

- to Sandra

- la

- the

- madera

- wood

- de

- of

- roble

- oak

- sek

- REFL

- lei

- 3SG.DAT

- quema

- burns

- fácilmente

- easily

- para PROk/*i

- for

- hacer

- make

- carbón.

- coal

- i. ‘When making coal, Sandra unintentionally makes oak wood burn easily.’

- ii. ‘When making coal, oak wood burns easily and Sandra is affected by it.’

- iii. ‘It is easy to burn Sandra’s oak wood in order to make coal.’

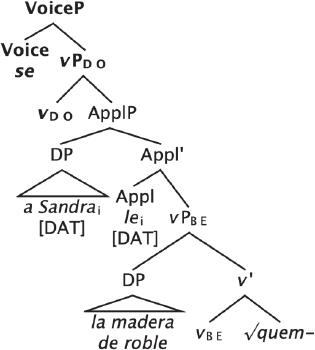

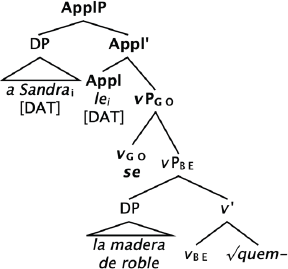

Following Cuervo (2003), I explain that an affected applicative head7 is responsible for introducing these dative arguments in the derivation. The dative’s different interpretations are structurally determined by the position this functional head occupies in the derivation. Thus, the affected reading arises when Appl –which is spelled out as a dative clitic pronoun– merges below the first subevent and is therefore applied to the notional object’s resulting state (vPBE). Depending on whether the first subevent is an activity one (vDO) (12a) –in generic passive contexts– or one of change (vGO) (12b) –in generic inchoative configurations– the dative may be interpreted as affected by an externally or internally caused change of state, respectively.

- (12)

- a.

- Appl = affected by an externally caused change of state

- (A Sandrai,) la madera de roble se lei quema fácilmente.

- ‘It is easy to burn Sandra’s oak wood.’

- b.

- Appl = affected an internally caused change of state

- (A Sandrai,) la madera de roble se lei quema fácilmente.8

- ‘Sandra’s oak wood burns easily, and she is affected by it.’

Alternatively, Cuervo (2003) points out that the applicative head may merge on top of the first subevent, giving rise to the accidental causer interpretation; however, I show that this is only possible in the generic inchoative variant (13), i.e. where no Voice head fills the position above vGO; this accounts for the data in (11).

- (13)

- Appl = accidental causer; ø Voice

- (A Sandrai,) la madera de roble se lei quema fácilmente.

- ‘Sandra unintentionally makes oak wood burn easily.’

I conclude that there exists a competition between the applicative head and Voice for the position atop the first vP, and adduces to Wood and Marantz’s (2017) notion of i*, an argument-introducing functional head whose spell-out form varies depending on its surrounding environment. Thus, i* would be realized as Voiceo when its complement is vDO (14a), and as Applo when it is vGO (14b). The causative instances containing Voice –active or passive– and an affected applicative simply start with two i* in the Numeration (15c); the one that merges before is realized as Appl, and the last one to merge becomes Voice.

| (14) | a. | [i*P i* [vP vDO]] ➔ [VoiceP Voice [vP vDO [VP …]]] |

| b. | [i*P i* [vP vGO]] ➔ [ApplP Appl [vP vGO [VP …]]] | |

| c. | [i*P i* [vP vDO [i*P i*]]] ➔ [VoiceP Voice [vP vDO [ApplP Appl [VP …]]]] |

Interestingly, the data from Asturian in (15) show that this phenomenon is also attested in this language, although slightly different. In Asturian, the accidental causer interpretation is only possible in the absence of se (15b).

- (15)

- Generic se-passive

- a.

- (A Xuani,)

- to Xuan.DAT

- esti

- this

- material

- material

- ruémpese-yi

- breaks.REFL.3SG.DAT

- fácil.

- easy

- i. ‘Xuan accidentally causes this material to break easily.’

- ii. ‘This material breaks easily, and Xuan is affected by it.’

- iii. ‘It is easy to break Xuan’s material, and he is affected by it.’

- Generic inchoative

- b.

- (A

- to

- Xuani,)

- Xuan.DAT

- esti

- this

- material

- material

- ruémpe-yi

- breaks.3SG.DAT

- fácil.

- easy

- i. ‘Xuan accidentally causes this material to break easily.’

- ii. ‘This material breaks easily, and Xuan is affected by it.’

- iii. ‘It is easy to break Xuan’s material, and he is affected by it.’

The examples in (15) show that both the generic passive and the generic inchoative counterparts of Asturian middles can host an affected applicative, spelled out as the third person dative clitic pronoun -y in this case, and optionally duplicated by a dative DP (a Xuan). While in the generic se-passive the dative can only receive one interpretation, i.e. affected by an externally caused change of state (15a.iii), the generic inchoative allows two readings for this argument, namely accidental causer (15b.i) and affected by an internally caused change of state (15.ii), but rules out that of affected by an externally caused event (15b.iii). As in the Spanish examples above, these data further demonstrate that the reflexive clitic pronoun se in Ibero-Romance languages is linked to the projection of a passive Voice head encoding the participation of an implicit external argument in the event. Because Voiceo fills the position above vPDO, Applo can only merge below it, therefore denoting the affected reading, but never the unintentional causer one. In the se-less variant, on the other hand, the lack of Voice allows the applicative to merge either above or below vPGO, which accounts for the two possible readings in (15b). In (16), the two possible merging positions of the applicative are synthesized.

- (16)

- a.

- Applicative as affected by an event (with and without Voice)

- b.

- Applicative as unintentional causer (no Voice)

Next, I discuss middle contexts containing alternating unaccusative verbs of movement.

2.3. Unaccusative predicates in Asturian middle contexts

The reflexive pronoun –although optional– is occasionally required with certain unaccusative verbs of movement for deictic (17a) or telicity (17b) reasons in languages like Spanish; in Asturian, however, it is banned.

- (17)

- Spanish

- a.

- La

- the

- luz

- light

- ?*(se)

- REFL

- marcha

- goes

- fácilmente

- easily

- en

- in

- esta

- this

- casa

- house

- tan

- so

- vieja.

- old

- ‘The power goes out easily in this old house.’

- b.

- Los

- the

- niños

- kids

- (se)

- REFL

- caen

- fall

- fácilmente

- easily

- cuando

- when

- comienzan

- begin.1PL

- a

- to

- caminar.9

- walk

- ‘Kids fall down easily when they start walking.’

- Asturian

- a.

- La

- the

- lluz

- light

- marcha(*se)

- goes-REFL

- fácil

- easy

- nesta

- in-this

- casa

- house

- tan

- so

- vieya.

- old

- ‘The power goes out easily in this old house.’

- b.

- Los

- the

- guajes

- kids

- cayen(*se)

- fall-REFL

- fácil

- easy

- cuando

- when

- entamen

- begin.1PL

- a

- to

- andar.

- walk

- ‘Kids fall down easily when they start walking.’

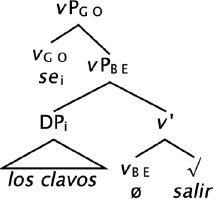

Cuervo (2014) elaborates an analysis of unaccusative verbs of movement in Spanish that alternate between a reflexive and a se-less variant (e.g. caer(se), ‘to fall’; salir(se), ‘to come out’). The key to her proposal is that the non-reflexive variants align with pure unaccusative verbs in that they convey a monoeventive event of change (vGO) without entailing a resulting state, i.e. no vBE (18a); on the other hand, the reflexive counterparts do involve a resulting state, and are therefore bieventive (vGO + vBE) (18b), just like the inchoative structures discussed above. Because the nature of these verbs is unaccusative, no Voice head merges in either structure.

- (18)

- Adapted from Cuervo (2014: 52)

- a.

- Salieron muchas flores.

- ‘Many flowers appeared.’

- b.

- Se salieron los clavos.

- ‘The nails came off.’

The reflexive pronoun in (18b) phonetically realizes the phi-features of the entity denoted by the DP displaying the resulting state, which sits in the specifier of vBE. Cuervo argues that the function of se in these contexts is twofold: (i) to satisfy vGO’s requirement to have an argument, as well as (ii) to favor the DP’s reading as the undergoer of the process of change and holder of the resulting state.

These two configurations show several structural differences, including telicity: while the se-less variant can be atelic, the one with the reflexive is necessarily telic, as shown in the examples in (19), with the verb caer (‘to fall’).10

- (19)

- Adapted from Cuervo (2014: 51)

- Atelic

- a.

- El

- the

- paracaidista

- parachutist

- cayó

- fell

- durante

- during

- dos

- two

- minutos/

- minutes

- *en

- in

- dos

- two

- minutos.11

- minutes

- ‘The parachutist fell for two minutes.’

- Telic

- b.

- El

- the

- paracaidista

- parachutist

- se

- REFL

- cayó

- fell

- *durante

- during

- dos

- two

- minutos/

- minutes

- en

- in

- dos

- two

- minutos.

- minutes

- ‘The parachutist fell in two minutes.’

Interestingly, the verb cayer (‘to fall’) in Asturian cannot co-occur with the reflexive under any circumstances, yet it admits both the telic and the atelic readings found in (19) for Spanish.

- (20)

- L’avión

- the-plane

- cayó

- fell

- mientres/

- for

- en

- in

- dos

- two

- minutos.12

- minutes

- ‘The plane fell for/in two minutes.’

Cuervo (2014) points out that the reflexive and non-reflexive variants of these unaccusative predicates in Spanish differ in terms of the types of DPs they select as arguments; thus, while the se-less variant can take bare NPs as complements (21a), the se-variant cannot (21b), a phenomenon also contemplated by Masullo (1992) and Fernández Soriano (1999a).13 As (21c) shows, the Asturian verb allows both bare NPs and full DPs.

- (21)

- Spanish – Adapted from Cuervo (2014: 50)

- a.

- Cayeron

- fell

- piedras.

- stones

- ‘Stones fell.’

- b.

- Se

- REFL

- cayeron

- fell

- *(las)

- the

- piedras.14

- stones

- ‘The stones fell.’

- Asturian

- c.

- Cayeron(*se)

- Fell.REFL

- (les)

- the

- piedres.

- stones

- ‘(The) stones fell.’

The data in (21c) showing that Asturian unaccusative constructions are less rigid in allowing both NPs and full DPs as internal arguments than their Spanish counterparts,15 together with the fact that both the telic and atelic interpretations in (19) are available in (20), suggest that the two configurations proposed by Cuervo (2014) (cf. (18) above) are available in Asturian. The difference between this language and Spanish is therefore that vGO receives no phonological content in the former, as I have been pointing out so far. Moreover, these unaccusative predicates can occur in generic middle contexts which must necessarily be agentless, i.e. generic inchoative/unaccusative configurations, as seen in (17) above, repeated in (22).

- (22)

- Spanish

- a.

- Los

- the

- niños

- kids

- se

- REFL

- caen

- fall

- continuamente

- continuously

- cuando

- when

- aprenden

- learn

- a

- to

- andar.

- walk

- ‘Kids fall constantly when they start walking.

- Asturian

- b.

- Los

- the

- guajes

- kids

- cayen

- fall

- de cutio

- continuously

- cuando

- when

- entamen

- begin

- a

- to

- andar.

- walk

- ‘Kids fall constantly when they start walking.’

As inchoative configurations, these constructions license the insertion of a by itself PP.

- (23)

- Spanish

- a.

- Los

- the

- aviones

- planes

- se

- REFL

- caen

- fall

- raramente

- rarely

- por

- by

- sí solos.16

- themselves

- ‘Planes rarely fall down by themselves.’

- Asturian

- b.

- Los

- the

- aviones

- planes

- cayen

- fall

- raramente

- rarely

- por

- by

- sí mesmos.

- themselves

- ‘Planes rarely fall down by themselves.’

Moreover, because these constructions lack Voice, they are expected to allow an applicative head to merge above vGO, and therefore entail a certain degree of agency. The example in (24) shows that this is the case, and that the dative can control into a purpose clause.

- (24)

- A

- to

- Antóni

- Anton.DAT

- cáyen-yi

- fall-3SG.DAT

- les

- the

- coses

- things

- de cutio

- continuously

- pa

- for

- fadiar

- annoy

- a

- to

- Xuacu.

- Xuacu.ACC

- ‘Antón constantly drops stuff to annoy Xuacu.’17

In sum, all the examples above demonstrate that vGO does not have a spell-out form in Asturian inchoative configurations, and that the reflexive pronoun se encodes an external argument in unaccusative structures such as passives or middle-passives.18 This leads us to discuss an apparent exception concerning unaccusative verbs of movement which appears to challenge this claim in the next session.

2.4. Linguistic transfer between Asturian and Asturian Spanish

The GLLA notes that certain verbs expressing movement such as dir (‘to go’), quedar (‘to remain’), or escapar (‘to flee) may occur along with the reflexive pronoun, although “paez preferible prescindir d’él” (ALLA 2001: 354) [‘it seems preferable to dispense with it;’ translation by the author].

- (25)

- ALLA (2001: 354)

- a.

- Él

- he

- foi(se)

- went.REFL

- pa

- for

- casa

- house

- d’atapecida.

- of-dusk

- ‘He left for home at dusk.’

- b.

- Quedé(me)

- stayed.1SG.REFL

- en

- at

- pueblu

- village

- tres

- three

- díes

- days

- más.

- more

- ‘I stayed in town for three more days.’

- c.

- Escapó(se)

- fled.3SG.REFL

- un

- a

- lladrón

- thief

- de

- from

- la

- the

- cárcel.

- jail

- ‘A thief escaped from prison.’

In Spanish, the presence of the reflexive with verbs of movement leads to semantic and structural differences. In addition to the differences in telicity mentioned above –i.e. the reflexive version implies perfective aspect, whereas the se-less variant is interpreted as imperfective–, this pronoun becomes obligatory if the meaning to be conveyed is that of vacating a particular location, as shown in (26) (Sánchez López 2002). In other words, the reflexive plays, in a way, the role of a deictic, referring to a point of departure or arrival, whereas the non-pronominal counterpart denotes movement within a continuum, either spatial or temporal (Maldonado 1997).

- (26)

- a.

- Se

- REFL

- marchó

- left

- de

- from

- aquí

- here

- porque

- because

- no

- not

- aguantaba

- endure

- más.

- anymore

- ‘She left because she couldn’t take it any longer.’

- b.

- Se

- REFL

- vinieron

- came.1PL

- de

- from

- Arizona

- Arizona

- para

- for

- escapar

- escape

- del

- from-the

- calor.

- heat

- ‘They returned from Arizona in order to escape the heat.’

Similarly, in the example sentences in (18), repeated below as (27) for convenience, the Spanish verb salir is interpreted as ‘to come out’ in the se-less variant (27a), and as ‘to come off’ in the pronominal one (27b), where the reflexive stands for the aforementioned point of departure. The same contrast can be found in Asturian, i.e. while the non-pronominal version allows both readings (27c), the pronominal one is necessarily interpreted as ‘to come off’ (27d).

| (27) | Spanish – Adapted from Cuervo (2014: 52) | |

| a. | Salieron muchas flores. | |

| ‘Many flowers appeared.’ | ||

| b. | Se salieron los tornillos. | |

| ‘The screws came off.’ | ||

| Asturian | ||

| c. | Salieron munches flores. | |

| ‘Many flowers appeared.’ | ||

| d. | Salieron/Saliéronse los torniellos. | |

| ‘The screws came off.’ | ||

Notice that the meaning of these verbs is compositional, since the type of DP they select as their internal argument conditions the possible interpretations. In (27c), the flowers are more likely to be interpreted as the entity sprouting from, rather than coming off, a certain place. However, if we think of a particular structure, like a carnival float, which is decorated with flowers that are attached/glued to it and they suddenly come off, (27c) would be an optimal candidate to express such context in Asturian, whereas the reflexive would be required in Spanish. Additionally, when a dative occurs in sentences containing these verbs in Asturian, this argument assumes such deictic role, which translates into certain redundancy if the reflexive pronoun is also present. Note that this is so independently of whether the dative argument is inanimate or not, as show in (28).

- (28)

- a.

- Saliéron(?se)-yi

- exited.3PL.REFL-3SG-DAT

- los

- the

- torniellos

- screws

- al

- to-the

- radiui.19

- radio.DAT

- ‘The screws came off the radio.’

- b.

- Salió(?se)-y

- exited.1SG-REFL-3SG.DAT

- un

- a

- güesu

- bone

- del

- of-the

- coldu

- elbow

- a

- to

- Enol.

- Enol.DAT

- ‘One of Enol’s elbow bones jolted.’

In light of these data, I will continue to claim that Asturian, again, does not require the reflexive in (27d) and (28a), in spite of their being inchoative configurations, because vGO does not have a phonetic form in this language. Moreover, I will assume that the fact that the reflexive is possible for a number of speakers in those contexts is a transfer from Spanish, due its major influence and dominance in the region; this adds on to the list of attested phenomena arising from the contact between these two languages (D’Andrés 2002, inter alia).

This transfer is not exclusive to verbs of movement. In fact, those undergoing the causative alternation can occasionally admit the reflexive pronoun in their agentless variant.

- (29)

- a.

- Fundió’l

- sank-the

- barcu

- boat

- (por

- by

- sí

- REFL

- mesmu).

- same

- ‘The boat sank by itself.’

- ‘S/he sank the boat.’

- b.

- Fundióse’l

- sank.REFL-the

- barcu

- boat

- (por

- by

- sí

- REFL

- mesmu).

- same

- ‘The boat sank by itself.’

- ‘The boat was sunk.’

What is interesting about the example in (29a) is the fact that structural ambiguity arises between an inchoative construction and an active causative configuration with an omniscient subject if the by itself PP is omitted. On the other hand, in (29b) the ambiguity emerges between an inchoative structure and a se-passive. It might well be that Asturian speakers choose the pronominal variant in order to disambiguate cases like (29a). In fact, if the theme in (29) occurs preverbally, the sentence becomes unquestionably inchoative, and the reflexive becomes redundant.

- (30)

- El

- the

- barcu

- boat

- fundió(#se)

- sank.REFL

- (por

- by

- sí

- REFL

- mesmu).

- same

- ‘The boat sank.’

Finally, it should also be noted that the opposite is true too, i.e. Asturian Spanish (AsturSp) also shows transfer from Asturian in this regard. Thus, it is possible to find se-less inchoative contexts in AsturSp, such as the ones in (31a-c), which are compared to their respective Standard Spanish counterparts (31a’–c’).20

- (31)

- AsturSp (Inchoative)

- a.

- Estas

- these

- toallas

- towels

- no

- not

- secan

- dry

- ni

- nor

- pa’

- for

- Dios.

- God

- ‘These towels won’t dry.’

- b.

- La

- the

- piel

- skin

- acaba

- ends

- como

- like

- escamando.21

- scaling

- ‘The skin ends up becoming scaly.’

- c.

- Standard Spanish (Inchoative)

- a’.

- Estas

- these

- toallas

- towels

- no

- not

- se

- REFL

- secan

- dry

- ni

- nor

- para

- for

- la

- the

- de

- of

- tres.

- three

- ‘These towels won’t dry.’

- b’.

- La

- the

- piel

- skin

- acaba

- ends

- escamándose.

- scaling.REFL

- ‘The skin ends up becoming scaly.’

- c’.

- La

- the

- morcilla

- blood sausage

- no

- not

- se

- REFL

- escapó.

- escaped

- ‘The blood sausage hasn’t gone anywhere.’

In this section, I have provided additional evidence that inchoative configurations in Asturian are non-pronominal, and I have proposed that those cases where the reflexive arises in such contexts can be accounted for by adducing to the influence of Spanish, the dominant language in the region. Moreover, I have shown that the transfer is bidirectional, since instances of se-less inchoative sentences are abundant in AsturSp.

3. Conclusions

In this paper, I have argued that the apparent optionality of the reflexive pronoun se in Asturian middle-passive contexts is not such, as it had been proposed in the descriptive work on this language; rather, it is associated with the projection of a passive Voice head encoding the participation of a generic external argument in the event, just as it happens in run-of-the-mill reflexively marked passives. On the contrary, inchoative configurations are necessarily non-pronominal in Asturian given their non-agentive nature, i.e. no Voice head merges in these contexts, and therefore the reflexive pronoun is not required. In other words, the verbalizing head of change vGO does not have a spell-out form, unlike in Spanish, or other closely related Ibero-Romance languages, such as Catalan; these languages show the reflexive in many inchoative configurations, particularly those entailing an end state (cf. Cuervo 2014).

Additionally, I showed that this phenomenon is subject to crosslinguistic influence, since certain inchoative cases and others containing unaccusative verbs of movement may appear reflexively marked are due to the influence of Spanish, the dominant language in the region. In a similar fashion, Asturian has impacted on the grammar of Asturian Spanish, and it is possible to encounter multiple instances of inchoative and unaccusative sentences lacking the reflexive in this dialect, contrary to what is expected in Standard Spanish and other dialects.

Finally, these assumptions would benefit from diachronic studies that would help determine at what point in the history of the languages the transfer began to take place; I leave this question open for further inquiry.

Abbreviations

ACC = accusative, DAT = dative, EPP = Extended Projection Principle, D = determiner, F = feminine, Gen = Generic, M = Masculine, NOM = Nominative, PL = plural, PART = partitive, REFL = reflexive, SG = singular, 1/2/3 = first/second/third persons

Notes

- Asturian is a Romance language spoken in the diglossic Principality of Asturias, in northern Spain, as well as in certain areas of the neighboring regions. Although Spanish remains the dominant language, the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (‘Academy of the Asturian Language’) –ALLA, hereafter– has made laudable efforts in the last few decades to standardize and normalize Asturian, resulting in remarkable works such as the Diccionariu de la llingua asturiana (‘Dictionary of the Asturian Language’) (ALLA 2000), the Gramática de la llingua asturiana (‘Grammar of the Asturian Language) (ALLA 2001) –henceforth GLLA–, or the Diccionariu etimolóxicu de la llingua asturiana (‘Etymological Dictionary of the Asturian Language’) (García Arias 2018). Consequently, scholars around the globe have been conducting research on the idiosyncrasies of the language, producing numerous analyses across the different linguistic and philological disciplines. [^]

- Not all inchoative contexts in Spanish require the reflexive clitic (e.g. reventó el neumático, ‘the tire burst’; hirvió el agua, ‘the water boiled’); I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out. See Vivanco Gefaell (2016) for an analysis of se-less sentences that denote a change of state as complex configurations comprising a resulting state. [^]

- The lack of unanimous consensus with respect to the presence/absence of the reflexive in inchoative contexts is discussed in Section 2.4. [^]

- Cachopos are a traditional Asturian dish consisting of two large, breaded beef steaks usually stuffed with Serrano ham and cheese; heavy, yet undoubtedly tasty! [^]

- The same derivation can also account for generic inchoative structures in Spanish, the only difference being that the reflexive clitic se is present in these contexts, as shown in (1b) above. According to Cuervo (2003) and Suárez-Palma (2020), the reflexive spells-out the subevent of change vGO in these configurations. [^]

- Similarly, Fernández Soriano (1999b) and Fernández Soriano & Mendikoetxea (2013) analyze these non-core datives as introduced by an applicative head relating them to other arguments or events. Although is based solely on Cuervo (2003) for the sake of brevity, I refer readers to those other two studies given their abundant, interesting data and sharp observations. [^]

- See also Pylkkänen (2002). [^]

- Note that Spanish, unlike Asturian, shows the reflexive clitic se in many inchoative structures. Cuervo (2003) and Suárez-Palma (2019, 2020) assume this pronoun spells out the subevent of change vGO in this language. [^]

- In Spanish, the reflexive pronoun tends to be omitted in atelic contexts with the verb caer (‘to fall’), as in (ia), and it becomes optional in others where telicity is implied, such as (ib).

- (i)

- a.

- El

- the

- dinero

- money

- no

- not

- (?se)

- REFL

- cae

- falls

- del

- from-the

- cielo.

- sky

- ‘Money doesn’t fall from the sky.’

[^]- b.

- Los

- the

- niños

- kids

- (se)

- REFL

- caen

- fall

- constantemente

- constantly

- cuando

- when

- comienzan

- begin.1PL

- a

- to

- andar.

- walk

- ‘Kids fall down constantly when they begin to walk.’

- An anonymous reviewer points out to me that the verb caer(se) is exceptional in many senses, since in certain Western Peninsular dialects of Spanish it can be transitive (ii), the equivalent of tirar ‘to let fall’ in Standard Spanish, thus giving rise to a causative alternation. I thank the reviewer for this remark, and I refer the reader to Jiménez-Fernández & Tubino-Blanco (2019) for a recent analysis of this phenomenon.

Although the causative counterpart of caer is not available in Asturian or Asturian Spanish, the present proposal predicts that, if it were, it would be reflexively marked in (middle)-passive. As far as I know, the unaccusative verb of movement marchar(se), shown in the examples in (17) above, lacks a causative counterpart both in Asturian and in Spanish. [^]

- (ii)

- Pedro

- Pedro

- cayó

- fell

- el

- the

- jarrón.

- vase

- ‘Pedro knocked over the vase.’

- A reviewer suggests that this non-reflexive example would be grammatical with the PP en dos minutos if such temporal complement refers to the time it takes the parachutist to fall from the airplane to the ground, i.e. caer can be telic without se; I agree with their judgments. Additionally, this same reviewer adds that el paracaidista se cayó durante dos minutos would be acceptable if the temporal PP refers to the duration of the parachutist’s resulting state, i.e. the parachutist was on the ground for two minutes as a result of falling. Vivanco Gefaell (2016) explores the relation between temporal adjuncts and se-sentences in Spanish. [^]

- Although both interpretations are grammatical, my informants point out to me that, in order to make the atelic reading more evident, they would opt for a periphrastic construction which, according to them, would sound more idiomatic:

[^]

- (i)

- L’avión

- the-plane

- tuvo

- was

- cayendo

- falling

- dos

- two

- minutos.

- minutes

- ‘The plane was falling for two minutes.’

- An anonymous reviewer notes that the se-variant does indeed allow bare plural NPs as internal arguments (i.a), and I agree; however, this is not possible with singular bare nouns (i.b). In fact, Cuervo (2014) bases her examples on Masullo’s “*se derritió manteca,” (1992: 272) (intended: ‘butter melted’), which contains a singular NP. It might be the case that plural NPs are in fact DPs containing a null partitive determiner, equivalent to des (‘some’) in French (i.c); I leave this hypothesis open for future research.

- (i)

- a.

- Se

- REFL

- cayeron

- fell.3PL

- piedras.

- stones

- ‘Stones fell.’

- b.

- *Se

- REFL

- cayó

- fell

- piedra.

- stone

- ‘A stone fell.’

[^]- c.

- *(Des)

- PART

- pierres

- stones

- sont

- are

- tombées.

- fallen.F.PL

- ‘Stones fell.’

- See MacDonald (2017) for an analysis along the lines of Cuervo (2014) of the fact that internal arguments in Spanish aspectual se sentences cannot be bare either. This author claims that these objects –just like the ones in inchoative constructions– are also subjects, in this case of a complex predicate comprising a verb and a null PP. Therefore, they are subject to Cuervo’s (2003; 2014) Revised Bare Noun Phrase Constraint, which is based on Suñer’s (1982):

[^]

(i) Bare Noun Phrase Constraint Revised (Cuervo 2014: 54): An unmodified common noun cannot be the subject of a predicate under conditions of normal stress and intonation. - At least for those speakers who share Cuervo’s (2014) judgments. [^]

- The non-reflexive variant of this example does also allow a by itself PP: e.g. las aceitunas raramente caen por sí solas del árbol; ‘olives rarely fall off the tree by themselves.’ I thank an anonymous reviewer for this example. [^]

- Note that this sentence has an additional meaning in which stuff falls onto Antón. [^]

- This excludes inherently reflexive verbs, such as arrepentise (‘to regret’), or esmucise (‘to slip’). [^]

- My informants point out that, although the reflexive variant is possible, they would choose the se-less counterpart over it in the context of an affected dative. [^]

- This trend appears to be a common feature in the northwestern varieties of European Peninsular Spanish, as discussed in the Nueva gramática de la lengua española (RAE-ASALE 2009: 3110). Additionally, de Benito Moreno (2015) provides quantitative data about the abundance of se in different dialects of the language and arrives at the same conclusion. [^]

- RTPA. (2020, May 18). Informativo Matinal. [Video]. Radio Televisión del Principado de Asturias. [^]

- This speaker alternates the reflexive inchoative from Standard Spanish with the se-less variant from Asturian; the mixture of both is common in AstSp. Notice that the sentence in bold no escapó is necessarily in Asturian Spanish, and not in Asturian, since negation in this language is not no but nun. [^]

- Güela Pepi. (2020, April 19). ¡FABADA ASTURIANA de la GÜELA PEPI! *Recetas güela pepi* – Paso a paso [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mzk5BpCSVpw. [^]

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers at Glossa for their invaluable feedback, as well as Johan Rooryck for his help and diligence throughout the peer-review process. I am also thankful to Antxon Olarrea for his feedback on this manuscript and data. Thank you to Xosé Lluís García Arias, Ana Cano and Claudia Elena Menéndez, whose judgments made this work possible. Finally, thanks to the abstract reviewers and audiences at the Agency and Intentionality in Language conference (University of Göttingen), at the Romance Grammars, Context and Contact 2021 (University of Birmingham, UK), at the 39th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (University of Arizona), and at the Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages 51 (University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign). All errors are my own. This research has been funded by the Humanities Scholarship Enhancement Fund, from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Florida.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Ackema, Peter & Schoorlemmer, Maaike. 2006. Middles. In Everaert, Martin & van Riemsdijk, Henk (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Syntax 1. 131–203. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9780470996591.ch42

ALLA. 2000. Diccionariu de la Llingua Asturiana. Oviedo: Academia de la Llingua Asturiana.

ALLA. 2001. Gramática de la Llingua Asturiana (3rd edition). Oviedo: Academia de la Llingua Asturiana.

Bhatt, Rajesh & Pancheva, Roumyana. 2006. Implicit Arguments. In Everaert, Martin & van Riemsdijk, Henk (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Syntax 1. 558–588. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9780470996591.ch34

Cuervo, María Cristina. 2003. Datives at large. Cambridge MA: Massachussetts Institute of Technology dissertation.

Cuervo, María Cristina. 2014. Alternating unaccusatives and the distribution of roots. Lingua 141. 48–70. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2013.12.001

D’Andrés Díaz, Ramón. 2002. Lletres Asturianes 81. 21–38.

De Benito Moreno, Carlota. 2015. Las construcciones con se desde una perspectiva variacionista y dialectal. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid dissertation.

Fernández Soriano, Olga. 1999a. Two types of impersonal sentences in Spanish: Locative and dative subjects. Syntax 2(2). 101–140. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9612.00017

Fernández Soriano, Olga. 1999b. Datives in constructions with unaccusative se. Catalan working papers in linguistics 7. 89–105.

Fernández Soriano, Olga & Mendikoetxea, Amaya. 2013. Non selected dative arguments in Spanish anticausative constructions. The Diachronic Typology of Non-Canonical Subjects 140. 3–34. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.140.01fer

García Arias, Xosé Lluís. 2018. Diccionariu Etimolóxicu de la Llingua Asturiana. Oviedo: Academia de la Llingua Asturiana and University of Oviedo.

Güela Pepi. (2020, April 19). ¡FABADA ASTURIANA de la GÜELA PEPI! *Recetas güela pepi* – Paso a paso [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mzk5BpCSVpw

Jiménez-Fernández, Ángel & Tubino Blanco, Mercedes. 2019. Causativity in Southern Peninsular Spanish. In Gallego, Ángel (ed.), The Syntactic Variation of Spanish Dialects. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190634797.001.0001

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Rooryck, Johan & Zaring, Laurie (eds.), Phrase structure and the lexicon, 109–137. Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8617-7_5

MacDonald, Jonathan E. 2017. Spanish aspectual se as an indirect reflexive. The import of atelicity, bare nouns, and leísta PCC repairs. Probus 29(1). 73–117. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/probus-2015-0009

Maldonado, Ricardo. 1997. Dos trayectos, un sentido. Notas conceptuales de la accidentalidad. In Bariga, Rebeca & Martín Butragueño, Pedro & Rivas, Alejandro & Rodríguez, Yliana (eds.), Varia lingüística y literaria. L años del Centro de Estudios Lingüísticos y Literarios, Mexico, Volume I. 165–189. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w42s.15

Marantz, Alec. 1984. On the nature of grammatical relations. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs, vol. 10. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Masullo, Pascual. 1992. Incorporation and Case Theory in Spanish. A Crosslinguistic Perspective. Seattle, WA: University of Washington dissertation.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2002. Introducing Arguments. Cambridge MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.

RAE-ASALE. 2009. Nueva gramática de la lengua española. Morfología y sintaxis. Real Academia Española y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa.

RTPA. 2020, May 18. Informativo Matinal. [Video]. Radio Televisión del Principado de Asturias.

Sánchez López, Cristina. 2002. Las construcciones con se. Estado de la cuestión. In Sánchez López, Cristina (ed.), Las construcciones con se. Madrid: Visor Libros.

Schäfer, Florian. 2008. The syntax of (anti-) causatives: External arguments in change-of-state contexts, vol. 126. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.126

Schäfer, Florian. 2009. The causative alternation. Language and Linguistics Compass 3(2). 641–681. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2009.00127.x

Suárez-Palma, Imanol. 2019. Stuck in the Middle: Dative arguments and middle-passive constructions in Spanish. Tucson AZ: The University of Arizona dissertation.

Suárez-Palma, Imanol. 2020. Applied arguments in Spanish inchoative middle constructions. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5(1). 9. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.827

Suárez-Palma, Imanol. 2021. Construcciones mediopasivas no agentivas en asturiano. Lletres Asturianes, 124. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17811/llaa.124.2021.9-31

Suñer, Margarita. 1982. Syntax and Semantics of Spanish Presentational Sentence-Types. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Vivanco Gefaell, Margarita. 2016. Causatividad y cambio de estado en español. La alternancia causativo-inacusativa. Universidad Complutense de Madrid dissertation.

Wood, Jim & Marantz, Alec. 2017. The interpretation of external arguments. In D’Alessandro, Roberta & Franco, Irene & Gallego, Ángel J. (eds.), The Verbal Domain, 255–278. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767886.003.0011