1 Introduction

Humans can comprehend anaphoric expressions, including reflexives, rapidly on the fly. This is no easy accomplishment since anaphoric expressions are referentially underspecified. For example, in a sentence like “Mary said that John scolded himself”, a comprehender needs to track the potential antecedents of the reflexive himself and recruit semantic (e.g. gender), syntactic (e.g. structural position), and discourse-level (e.g. topicality) cues to guide antecedent retrieval. In this paper, we ask how linguistic cues at the syntactic and discourse-pragmatic levels constrain real-time antecedent retrieval, with a specific focus on the Chinese bare reflexive ziji, motivated by additional linguistic interests.

According to Chomskyan Binding Theory (e.g. Chomsky 1981), the antecedent of a reflexive is restricted to the local domain (often a tensed clause) and must c-command (i.e. be structurally higher than) the reflexive. However, it was soon realized that semantic and discourse-pragmatic factors need to be considered to account for cases like (1) (Kuno 1987: 127) where the reflexive can be bound non-locally.

| (1) | Johni told Mary that there was a picture of himselfi in the morning paper. |

These kinds of reflexives are typically called exempt anaphors (e.g. Pollard & Sag 1992; Reinhart & Reuland 1993). Prior psycholinguistic work also suggests that discourse-level factors guide both offline and online processing of reflexives (e.g. Kaiser et al. 2009; Sloggett 2017).

It has been argued that the notion of logophoricity or point of view (POV) is relevant for exempt anaphors (e.g. Kuno 1987; Sells 1987; Huang & Liu 2001; Oshima 2007; Charnavel 2020). According to Sells (1987: 455), the antecedent of a logophoric reflexive – what we call the POV center – has the role of Source (“the intentional agent of communication”), Self (“one whose mental state or attitude the content of the proposition describes”) or Pivot (“one with respect to whose (space-time) location the content of the proposition is evaluated”).

Importantly, Huang and Liu (2001: 156) showed that in Mandarin Chinese the long-distance (LD) reflexive ziji (‘self’) exhibits all three of these logophoric properties (Source, Self, and Pivot). In other words, ziji can refer to a non-local antecedent if that antecedent is a POV center (which we notate with [+POV]).

It has been proposed that, although the LD ziji can refer to an internal POV center (sentence-internal matrix subject), the intrusion of an external POV center (the speaker/comprehender) makes LD binding unavailable due to the need to avoid conflicting perspectives (e.g. Huang et al. 2009: 343). This phenomenon is known as the blocking effect (Huang et al. 1984; Tang 1989; Cole et al. 1990; Xu 1993; Pan 1997; Pollard & Xue 1998; Huang & Liu 2001; Wang & Pan 2015; a.o.). It is exemplified in (2): here, ziji is blocked from reaching the non-local antecedent Zhangsan by the blocker ‘I/you’.

- (2)

- Zhāngsāni

- Zhangsan

- zhīdào

- know

- wǒ/nǐj

- 1sg/2sg

- haì-le

- ruin-perf

- zìjǐ*i/j.

- self

- ‘Zhangsani knew that I/youj ruined self*i/j.’

There are many debates in the linguistics literature regarding the analysis of the blocking effect. Generally speaking, three main approaches can be identified, the syntax-based account (e.g. Tang 1989; Cole et al. 1990; Huang & Tang 1991; Cole & Sung 1994), the perspective-based account (e.g. Huang et al. 1984; Pan 1997, 2001; Huang & Liu 2001; Huang et al. 2009), and the unified account (e.g. Charnavel et al. 2017).

The present work aims to inform both theoretical analyses and online-processing-oriented accounts of blocking. We have three main aims.

First, to assess the predictions of these three linguistic accounts of blocking, we test whether subject and object blockers differ in their effectiveness. As we will see, the existing theoretical accounts make divergent predictions about whether the structural prominence of the blocker matters. We review these accounts in more depth in Section 2.

Second, we are interested in how the blocking effect interacts with verb semantics, in particular self-directed vs. other-directed verbs which bias a local vs. non-local interpretation of ziji, respectively. We aim to contribute to this question using experimental methods, in order to supplement prior introspective judgments that have yielded inconsistencies.

Third, we investigate the online processing of blocking to see how well it relates to two processing models, which we call the standard cue-based retrieval model and the structure-based retrieval model. We discuss these models and our predictions in Section 4.

2 Theoretical accounts of the blocking effect

In this section we review three linguistic accounts, the syntax-based account (e.g. Tang 1989; Cole et al. 1990; Huang & Tang 1991; Cole & Sung 1994), the perspective-based account (e.g. Huang et al. 1984; Pan 1997; 2001; Huang & Liu 2001; Huang et al. 2009), and the unified account (e.g. Charnavel et al. 2017).

The syntax-based account of LD ziji was pioneered by Tang (1989) who argued that LD binding is reducible to cyclic movements of ziji to agree with subjects in logical form (LF) (also see Battistella 1989; Cole et al. 1990; Huang & Tang 1991; Cole & Sung 1994; Cole & Wang 1996). This account predicts that only subject blockers lead to blocking. Despite its elegance, this account is challenged by Xue et al. (1994) who argued that a first-/second-person object pronoun also blocks LD binding of ziji (see (3)), contrary to the predictions of the syntax-based account.

- (3)

- Zhāngsāni

- Zhangsan

- gàosù

- tell

- wǒj

- 1sg

- Lǐsìk

- Lisi

- hèn

- hate

- zìjǐ*i/*j/k.

- self

- ‘Zhangsani told mej that Lisik hated self*i/*j/k.’

Given this counterexample and other reasons summarized in Huang et al. (2009), a discourse-based analysis, the perspective-based account, has gained traction in recent theories of LD ziji (Huang et al. 1984; Pan 1997; 2001; Huang & Liu 2001; Cole et al. 2001; Huang et al. 2009; Wang & Pan 2015). This approach evolved from the ‘direct discourse complementation’ analysis of English pronouns by Kuno (1972) and was applied to Mandarin by Huang et al. (1984). For example, a sentence like ‘Zhangsan said I liked ziji’ in Mandarin was argued to be derived from the underlying structure in (4) where the internal POV center Zhangsan conflicts with the external POV center ‘I’ (the same argument also holds for object blocking (see Huang & Liu 2001: 321)). Therefore, the unacceptability of LD binding in the presence of ‘I/me’ is ascribed to the difficulty of holding two perspectives at a time and the primacy of the external POV center, summarized by Charnavel et al. (2017: 54), repeated in (5).

- (4)

- Zhāngsāni

- Zhangsan

- shuō

- say

- “wǒj

- 1sg(=external speaker)

- xǐhuān

- like

- wǒ*i/j.”

- 1sg(=Zhangsan)

- ‘Zhangsani said “Ij liked me*i/j”.’

| (5) | Discourse requirements in Chinese | |

| a. | The antecedent for a long-distance reflexive must be the internal Pivot (in our terms, POV center) | |

| b. | The presence of a first- or second-person pronoun anywhere in the sentence constitutes an external Pivot, which blocks the possibility of an internal Pivot | |

While this perspective-based approach can account for several properties of LD ziji, Charnavel et al. (2017) proposed a unified account which incorporates both the syntactic and discourse analyses. This account is based on the observation that LD binding is worse with subject blockers than with object blockers.

- (6)

- a.

- Zhāngsāni

- Zhangsan

- yǐweí

- think

- Lǐsìj

- Lisi

- huì

- will

- bǎ

- ba

- Xiǎomíngk

- Xiaoming

- daì

- bring

- huí

- back

- zìjǐi/j/k

- self

- de jiā.

- de home

- ‘Zhangsani thought Lisij would bring Xiaomingk to self’si/j/k home.’

- b.

- Zhāngsāni

- Zhangsan

- yǐweí

- think

- Lǐsìj

- Lisi

- huì

- will

- bǎ

- ba

- nǐk

- 2sg

- daì

- bring

- huí

- back

- zìjǐ?i/j/k

- self

- de jiā.

- de home

- ‘Zhangsani thought Lisij would bring youk to self’s?i/j/k home.’

- c.

- Zhāngsāni

- Zhangsan

- yǐweí

- think

- wǒj

- 1sg

- huì

- will

- bǎ

- ba

- nǐk

- 2sg

- daì

- bring

- huí

- back

- zìjǐ*i/j/k

- self

- de jiā.

- de home

- ‘Zhangsani thought Ij would bring youk to self’s*i/j/k home.’

In (6a), LD binding of ziji by the matrix subject Zhangsan is allowed as there is no blocker in the subordinate clause. In (6b), LD binding is less well-formed because the object ‘you’ is a POV center. However, syntactically it is not a “blocker” because ‘you’ is an object. In (6c), LD binding is assumed to be unavailable because the blocker ‘I’ is not only a POV center but is also in subject position. Based on these observations, Charnavel et al. (2017) argue that there is a syntactic component to blocking, as subject blocking in (6c) is stronger than object blocking in (6b). The perspective-based account fails to predict this asymmetry. Simply put, Charnavel et al.’s unified account predicts that a POV-sensitive logophoric ziji is more likely to be blocked by an external POV center in a syntactically prominent subject position than by a POV center in a syntactically less prominent object position.

However, (6b) and (6c) do not provide indubitable evidence that it is the subject/object status of the blocker alone that drives the difference. It could be that (6c) is worse due to the presence of dual blockers ‘I’ and ‘you’, which presumably strengthens the external POV center. Moreover, these intuitions have not been systematically examined. Nevertheless, the unified account provides an important insight by raising the possibility of both syntactic and perspectival components playing a role in blocking. Thus, one of our aims is to inform theoretical analyses of blocking by assessing whether the subject/object status of the blocker modulates linguistic blocking. We test for effects of the subject/object asymmetry in both offline forced-choice judgment and online sentence processing.

Note that these linguistic accounts do not make any direct predictions about the role of verb semantics on the blocking effect. Although some linguists suggest that blocking can be overridden by verbs biasing non-local antecedents (e.g. Yu 1992; Y. Huang 1994; Pollard & Sag 1998), we do see cited examples where LD binding is deemed unavailable even with other-directed verbs (e.g. Huang & Liu 2001; Huang et al. 2009), suggesting that introspective judgments regarding verb bias may not be very clear. Therefore, an additional aim of this study is to systematically test effects of verb semantics on blocking.

3 Experimental work on the blocking effect

Theoretical analyses of LD ziji make divergent predictions about whether the syntactic prominence of the blocker is expected to matter, but conclusive evidence is lacking. In this section, we review existing experimental work on blocking and conclude that this question also remains unanswered on the experimental side. Indeed, broader questions still remain regarding the robustness of the blocking effect. This section also lays the foundation for our discussion of the sentence processing models in Section 4.

Experimental studies on the blocking effect mostly focused on assessing whether blocking is present in offline judgments and/or online parsing (e.g. Schumacher et al. 2011; He 2014; He & Kaiser 2016; Han 2020), but have not tested whether syntactic prominence of the blocker modulates the blocking effect. Recent offline acceptability data from Han (2020) provides evidence of blocking in sentences with subject blockers. However, participants’ interpretation of ziji was not directly tested (no information about antecedent choice).

Earlier work by Schumacher et al. (2011) recorded Mandarin native speakers’ event-related brain potentials (ERPs) and found that local first-/second-person blockers elicited a greater early positivity than local third-person non-blockers when verbal semantics biases LD binding, suggesting competition between the local blocker and the matrix subject. Their study also highlights the fact that verb bias plays a pivotal role in guiding the interpretation of ziji. For example, an other-directed verb like ‘approach’ overwhelmingly biased participants towards the matrix subject in spite of the local blocker ‘I/you’. In this paper, we build on Schumacher et al. (2011) and directly assess effects of verb semantics.

Note that not all studies have found clear evidence of blocking. In a self-paced reading study, He & Kaiser (2016) manipulated the person feature of the embedded subject to yield the design shown in (7). In the non-blocker condition, the embedded subject is a third-person NP; in the blocker condition, the embedded subject is a first-person pronoun ‘I’. He & Kaiser assume that competition between the local blocker (external POV center) and non-local antecedent (internal POV center) should lead to reading slowdowns at the critical region ziji due to a perspective clash. They predicted that if the blocker interferes with LD binding, longer reaction times (RTs) at (or after) ziji should be observed in the blocker condition. (Our studies use a different design to diagnose the blocking effect.)

- (7)

- Zhāngsān

- Zhangsan

- gàosù

- tell

- biérén

- others

- Lǐsì/wǒ

- Lisi/1sg

- juéde

- think

- zìjǐ

- self

- míngnián

- next-year

- kéyǐ

- can

- kǎojìn

- get-in

- hǎo

- good

- dàxué.

- university

- ‘Zhangsan told others that Lisi/I thought self could get in a good university next year.’

However, the blocker and non-blocker conditions did not differ in RTs. Sentence-final forced-choice judgment also showed no blocking effect (local binding tendency for ‘I’ was not significantly different from that for Lisi in (7)). Although unexpected, these results are in line with previous studies which have frequently shown a strong locality bias for online and offline interpretation of ziji in isolated contexts (e.g. Gao et al. 2005; Li & Zhou 2010; Jäger et al. 2015; Dillon et al. 2016; Wang 2017). That is, Mandarin natives tend to only consider the local but not the non-local NP as the potential antecedent, especially when neither of the third-person referents is fit to be an internal POV center in neutral contexts (see Brunyé et al. 2009 for related work on perspective).

To summarize, previous experiments show that a local blocker could cause parsing difficulty in online and offline comprehension, but do not provide consistent evidence of blocking effects. Furthermore, the potential effect of blockers’ syntactic prominence has not been systematically tested.

Indeed, prior findings suggest that when no POV center is provided, ziji tends to be constrained by locality, arguably because it is easier to encode anaphoric relations in syntax than in discourse (Reuland 2001; 2011). (We do not claim that local ziji and LD ziji are different linguistic entities since theoretically they can be unified, as in Charnavel (2020). We simply note that ziji shows anaphoric and logophoric properties in different contexts.) What will happen when a POV center is available? To test how ziji is interpreted when a POV center is present, sentences such as (8), with a clear discourse topic rementioned in the second sentence, can be used (see Oshima 2007: 22, ex.(7b), for a similar manipulation).

- (8)

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí

- class

- lǐ

- in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- tīngshuō

- heard

- wǒ/Wáng

- 1sg/Prof.

- jiàoshoù

- Wang

- gānggāng

- just

- pīgaǐ-

- grade-

- le

- PERF

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he heard that I/Prof. Wang had just graded self’s academic paper.’

In (8), the non-local antecedent Xiaoming is the discourse topic as both sentences provide information about him. Furthermore, matrix subjects tend to be topics in topic-prominent language like Mandarin (e.g. Chao 1968; Li & Thompson 1976). According to the Topic Empathy Hierarchy (Kuno 1987: 210), “given an event or state that involves A and B such that A is coreferential with the topic of the present discourse and B is not, it is easier for the speaker to empathize with A than with B.” Here, the term “empathy” is often synonymous with the term point of view (POV) (e.g. Kuroda 1965; Kuno & Kaburaki 1977; Sells 1987; Oshima 2007). Thus, the introduction of a discourse topic by means of a context sentence biases one to take the perspective of Xiaoming rather than that of Prof. Wang. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that the discourse topic will be construed as the POV center, thereby allowing us to better detect the blocking effect.

Another crucial ingredient in our investigation of the blocking effect is verb semantics. In the self-paced reading experiments, we use verb semantics as a tool to create a bias to interpret ziji as referring to the local vs. non-local antecedent, illustrated in (9), to assess the impact of the blocker on processing of ziji. In (9), ‘grade’ is other-directed because a person normally grades others’ papers, not their own. In contrast, ‘publish’ is self-directed since typically a person publishes their own work. If the blocker biases native speakers to take the perspective of the local antecedent ‘I’, other-directed verbs like ‘grade’ should lead to reading slowdowns compared to self-directed verbs at the critical region ziji because ‘I’ normally do not grade ‘my own’ paper. If there is no blocking effect (i.e. ziji refers to Xiaoming), self-directed verbs like ‘publish’ should lead to slowdowns, because ‘I’ normally do not publish someone else’s paper. In short, we use verb bias as a diagnostic to detect (non-)local binding preference. The efficacy of the biased verbs we used were confirmed in a separate study (see Section 6.1).

- (9)

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí

- class

- lǐ

- in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- tīngshuō

- heard

- wǒ

- 1sg

- gānggāng

- just

- fābiǎo/pīgaǐ-le

- publish/grade-perf

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he heard that I had just published/graded self’s academic paper.’

4 Psycholinguistic models

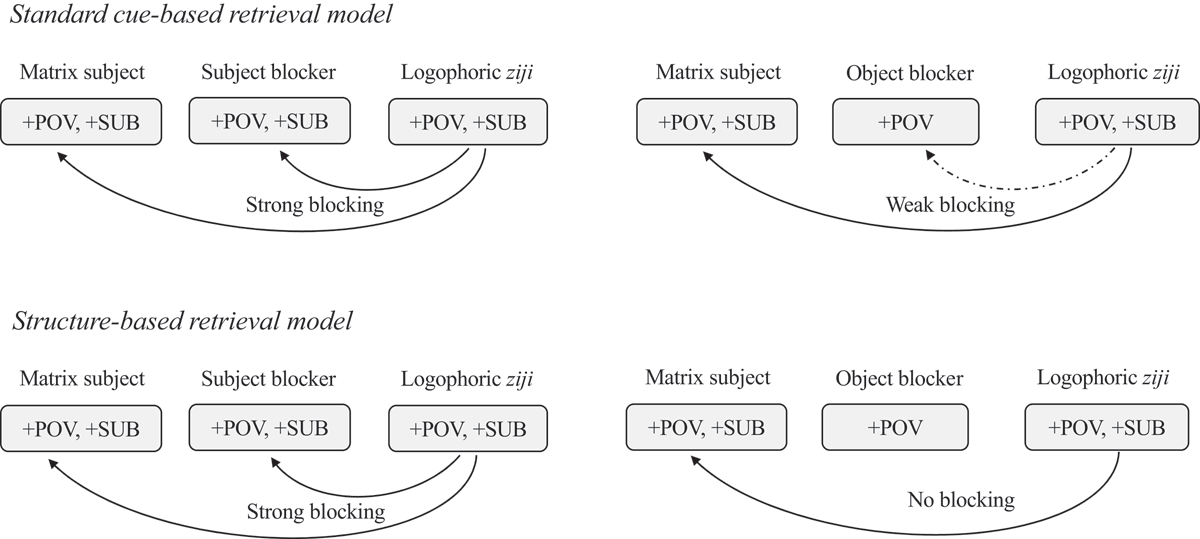

The present work on blocking also aims to test models of sentence processing. In this paper, we focus on two processing models, the standard cue-based retrieval model and structure-based retrieval model. We focus on these models because they are widely influential but make different predictions.

The standard cue-based retrieval model assumes that all cues, by default, are equally available and utilized immediately for antecedent retrieval by a content-addressable memory which has access to both semantic (e.g. gender, animacy) and syntactic (e.g. c-command, subjecthood) cues (e.g. Lewis & Vasishth 2005; Van Dyke & McElree 2006; Patil et al. 2016). Thus, in the present study, upon encountering ziji, the POV cue should be immediately visible to the parser and trigger a logophoric interpretation of ziji. This essentially means that ziji will be marked with a bundle of cues for antecedent retrieval, including [+POV] and potentially [+SUB] (the latter depends on the relevant linguistic facts, to be determined empirically). (Note we do not treat c-command as a distinguishing property between subject and object blockers in our test sentences, given that an anonymous reviewer suggests both might c-command ziji. If we were to include c-command as a differentiating cue, our predictions and conclusions would not be negatively impacted; in fact they would be strengthened.)

Since the blocker ‘I/me’ is also a POV center, interference from the blocker will occur, compared to a non-blocker which we can notate with [-POV]. Therefore, the standard cue-based model predicts that, regardless of the syntactic prominence of the blocker, non-local binding should be more difficult in conditions with a blocker than in conditions without one. If there is a syntactic component to linguistic blocking, the standard model also predicts subject blocking to be stronger than object blocking, as the subject ‘I’ fully matches the retrieval cues ([+POV, +SUB]) of ziji, while the object ‘me’ only constitutes a partial match (i.e. it lacks [+SUB]).

Unlike the standard model, the structure-based retrieval model argues that syntactic cues have more weight and are prioritized in early-stage parsing (e.g. Nicole & Swinney 1989; Sturt 2003; Van Dyke & McElree 2011; Dillon et al. 2014; Chang et al. 2020). Note that it is not quite clear how a structure-based model would handle a discourse-level cue like POV center. Even in the few studies that did look at discourse-level cues (e.g. Kaiser et al. (2009), Sloggett (2017) on English), the target stimuli did not include contexts that would make the non-local POV center highly prominent and logophoric interpretations of reflexives readily available. Nevertheless, two versions of the structure-based model are conceivable. A strong version which ignores discourse-level cues predicts that ziji will only be guided by [+local] and [+c-command] in the early stage, and thus only local binding should be attempted. However, as we shall see, this hypothesis is too strong. Therefore, we do not focus on it in this paper.

In contrast, a weaker version of the structure-based model predicts that the parser is only sensitive to [+POV] cues in syntactically legitimate positions which would still trigger the logophoric interpretation of ziji. Crucially, if ziji is encoded with [+SUB], the search process will be syntactically constrained such that only POV centers in subject positions will be retrieved. Antecedents in syntactically illegitimate positions (i.e. object ‘me’) should fail to induce blocking. Therefore, if there is a syntactic component to the blocking effect, only subject blocker ‘I’ (but not object blocker ‘me’ and non-blockers) can lead to blocking in the early stage. But if syntactic prominence is irrelevant to blocking, logophoric ziji would only be encoded with [+POV] and thus this version of the structure-based account would make the same predictions as the standard account, since no syntactic cues are to be matched between ziji and preceding POV centers. Figure 1 illustrates the different online predictions made by the standard and structure-based retrieval models assuming a syntactic component to blocking. Lastly, we emphasize that the structure-based model does not preclude the possibility of first-person ‘me’ in object position blocking LD binding of ziji during a later processing stage via a discourse-level process.

5 Overview of the aims of this paper

This work aims to contribute to our understanding of the blocking effect and the roles of semantic, syntactic, and discourse-level cues to online antecedent retrieval. As such, this work is motivated by both linguistic and psycholinguistic interests. Summarizing our discussion so far, there are three main goals.

First, with offline forced-choice judgment tasks, we aim to empirically examine the blocking effect when a first-person blocker is in subject or object position. The syntax-based account predicts that only subject blockers can lead to blocking while object blockers cannot, in contrast to the perspective-based account which predicts similar blocking effects regardless of the blocker’s syntactic position. The unified approach also predicts blocking effects for both subject and object blockers but holds that the former should induce stronger blocking.

Second, we are interested in the contribution of verb semantics to the blocking effect. In prior work, verb bias has been used to create non-local dependencies (e.g. Li & Zhou 2010; Schumacher et al. 2011; He 2014), but this property of verbs has not been systematically studied in relation to the blocking effect. Although linguists have noticed the influence of verb semantics (e.g. Yu 1992; Y. Huang 1994; Pollard & Xue 1998), the judgments reported in the literature are not consistent. Thus, more information on the impact of lexical level semantics on blocking effect will enrich our understanding of this phenomenon.

Third, we assess the predictions of two processing models. The standard cue-based retrieval model predicts that both subject and object blockers will lead to blocking. Furthermore, should the offline experiments reveal a syntactic component to linguistic blocking, the standard model predicts stronger blocking effect when the blocker is a subject. In contrast, the structure-based retrieval model predicts no interference to LD binding of ziji by the object blocker ‘me’ but strong interference by the subject blocker ‘I’.

The experiments in this paper are presented in the following order. Experiment 1 investigates the blocking effect when the blocker is in a syntactically prominent subject position. Experiment 2 investigates whether the same blocking effect occurs with object blockers. Each experiment is comprised of a forced-choice judgment task and a self-paced reading task. Note that this study follows a relative approach and compares conditions to each other. We do not make claims about antecedents’ absolute levels of availability/accessibility.

6 Experiment 1: Subject blocker

Experiment 1 comprises an offline forced-choice judgment experiment (Experiment 1a) and an online self-paced reading experiment (Experiment 1b). The offline task examines (i) whether there is blocking with subject blocker ‘I’ and (ii) the strength of the blocking effect. In offline experiments, the blocking effect is operationalized as local binding advantage of the blocker conditions compared to the non-blocker conditions. In online experiments, blocking effects can be diagnosed using verb bias as a tool: If local binding is preferred (i.e. the non-local antecedent is blocked), other-directed verbs (biasing towards the non-local antecedent) should lead to reading slowdowns at (or after) ziji, compared to self-directed verbs.

6.1 Materials

The factors Blocker type (blocker/non-blocker) and Verb bias (self-directed/other-directed) were crossed in a factorial design. The target sentence is preceded by a topic sentence, the subject of which (i.e. Xiaoming) is also the matrix subject of the target sentence (ex.10). Therefore, the matrix subject of the target sentence is a discourse topic which we refer to as the internal POV center. The local subject is either a blocker ‘I’ or a third-person non-blocker NP (e.g. ‘Prof. Wang’). The third-person NP is typically a proper name. The discourse topic in the target sentence was shown in the pronominal form (e.g. ‘he’) to avoid a repeated name penalty. A large body of work shows that use of a name to refer to a prominent antecedent incurs extra processing cost and slows down reading times (see e.g. Gordon et al. 1993; Gordon & Hendrick 1998; Almor 1999).

- (10)

- a.

- Blocker/Self-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí

- class

- lǐ

- in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- wǒ

- 1sg

- tīngshuō

- heard

- gānggāng

- just

- fābiǎo-le

- publish-perf

- zìjǐ de

- self de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he heard that I had just published self’s academic paper.’

- b.

- Blocker/Other-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí

- class

- lǐ

- in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- tīngshuō

- heard

- wǒ

- 1sg

- gānggāng

- just

- pīgaǐ-le

- grade-perf

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he heard that I had just graded self’s academic paper.’

- c.

- Non-blocker/Self-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí

- class

- lǐ

- in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- tīngshuō

- heard

- Wáng

- Prof.

- jiàoshoù

- Wang

- gānggāng

- just

- fābiǎo-le

- publish-perf

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he heard that Prof. Wang had just published self’s academic paper.’

- d.

- Non-blocker/Other-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí

- class

- lǐ

- in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- tīngshuō

- heard

- Wáng

- Prof.

- jiàoshoù

- Wang

- gānggāng

- just

- pīgaǐ-le

- grade-perf

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he heard that Prof. Wang had just graded self’s academic paper.’

The topicality manipulation is critical, because according to the Topic Empathy Hierarchy (Kuno 1987), people tend to assume the perspective of a discourse topic, which will bias a logophoric reading of ziji. Thus, topicality allows us to introduce an internal POV center.

The verb bias manipulation probes the impact of verb semantics on native speakers’ preferences for local vs. non-local readings of ziji in forced-choice judgment and serves as a diagnostic for detecting the dependency length (local vs. non-local) in self-paced reading. The effectiveness of the self- vs. other-directed verb bias was confirmed by a separate study (reference removed for anonymity).1

In the present work, ziji is in the genitive form (in self-paced reading, genitive DE was presented separately, following Chen et al. (2012)). The genitive form was chosen largely because this form is the most frequent one in Mandarin (Jia 2020). Yet, previous studies mostly test ziji in subject (Lu 2011; He & Kaiser 2016; Wang 2017) and direct object (Gao et al. 2005; Li & Zhou 2010; Schumacher et al. 2011; Jäger et al. 2015; Dillon et al. 2016) positions, leaving ziji in its genitive form less studied (but see Chen et al. 2012). To fill this gap, we chose the genitive form.

Twenty sets of target items were distributed into 4 lists using a Latin square design. Thus, each participant only saw one condition per item and read 5 target sentences per condition in the experiment. Half of the discourse topic characters were male; half were female. Ten verbs (‘say’, ‘hear’, ‘notice’, etc.) were used as the matrix verb in the target sentence. In the self-paced reading experiment, the critical region was the reflexive ziji followed by three words: DE, an adjective (e.g. ‘academic’), and an NP (e.g. ‘paper’). The target stimuli were mixed with 20 filler sentences in a pseudo-randomized manner such that each target sentence was followed or preceded by a filler sentence. Each filler item was likewise composed of a topic and a target sentence but did not contain reflexives.

6.2 Experiment 1a

As a first step, we examined whether first-person pronouns in subject positions lead to higher percentages of local binding compared to non-blockers and, if so, how verb bias modulates blocking effects.

6.2.1 Participants

Fifty Mandarin native speakers participated over the internet. The participants were all above 18 and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The studies reported in this paper were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Southern California.

6.2.2 Procedure

Offline experiments were hosted on Qualtrics. On each trial, the topic sentence was presented first, followed by the target sentence on the next screen. This was done to match the format of the self-paced reading task. After reading each sentence, participants answered a comprehension question (e.g. ‘who wrote the academic paper?’) with answer choices consisting of the matrix subject (e.g. ‘Xiaoming’) and the local subject (‘Prof. Wang’ in Non-blocker conditions and ‘I’ in Blocker conditions). See (11) for an example. Thus, participants’ answers indicate how they interpret ziji (e.g. as referring to ‘Xiaoming’, or to ‘Prof. Wang’ or ‘I’). Our set-up with the answer choices follows He & Kaiser (2016). The order of the antecedent choices was counterbalanced.

| (11) | Comprehension question: ‘Who wrote the academic paper?’ (question presented in Chinese) (A) Professor Wang/I (B) Xiaoming |

6.2.3 Predictions

All three linguistic approaches (see Section 2) predict ziji to show a stronger preference for local binding with subject blockers than with non-blockers, although whether the blocking effect is absolute is an empirical question. Thus, a main effect of Blocker type is expected. A main effect of Verb bias is also predicted such that self-directed verbs will elicit more local choices than other-directed verbs. Crucially, if verb bias semantics modulates the blocking effect, then between the two blocker conditions, we predict higher percentages of local binding with self-directed than with other-directed verbs.

6.2.4 Data analysis

Given the binary nature of the data, we fit mixed-effect logistic models (with glmer) in R (R core team 2018) implemented by the R package lme4. Two contrasts were fit for the factors Blocker type (Blocker coded as +0.5, Non-blocker coded as –0.5) and Verb bias (Other-directed verb coded as +0.5, Self-directed verb coded as –0.5), respectively. T-values were transformed into p-values using Satterthwaite approximation implemented by the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al. 2015). For all experiments reported in this paper, models were first fit with random intercepts and random slopes. If the model failed to converge, we simplified the model by following Bates et al. (2015). A parsimonious model is to be preferred over a more complex one if model comparison suggests that the two models do not differ significantly.

6.2.5 Results

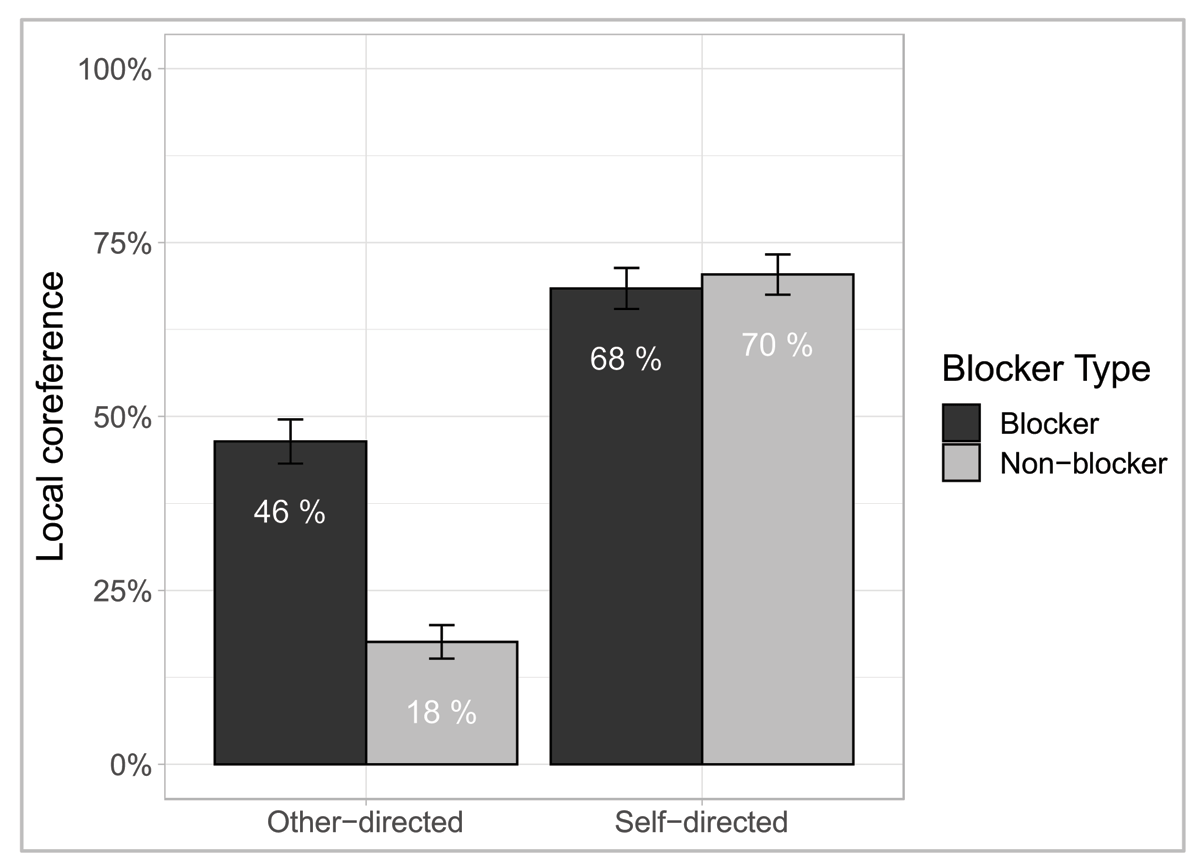

The antecedent choice data is displayed in Figure 2. The y-axis shows the mean percentage of local coreference for ziji. For statistics, see Table 1. We found main effects of Blocker type and Verb bias (ps < 0.001): participants preferred local interpretations of ziji more often in the blocker than in the non-blocker conditions, and in the self-directed than in the other-directed verb conditions. The Blocker type main effect suggests that the external POV center ‘I’ competes with the internal POV center (the discourse topic), supporting claims in the literature. The Verb bias main effect indicates that verb semantics plays an important role in the interpretation of ziji: participants chose local antecedents more often in the self-directed than in the other-directed verb condition, even in the presence of a blocker (68% vs. 46%, β = –1.26, SE = 0.22, t = –5.61, p < 0.001). Finally, we found an unpredicted Blocker type by Verb bias interaction (p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons suggest that the blocking effect reached significance in the other-directed verb conditions (β = 1.65, SE = 0.24, t = 6.96, p < 0.001), but not in the self-directed verb conditions (β = –0.04, SE = 0.22, t = –0.21, p = 0.84). We return to this asymmetry in the Discussion section.

Summary of statistics for Experiment 1a (*: <0.05).

| β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blocker type | 0.78 | 0.16 | 4.89 | <0.001* |

| Verb bias | –2.03 | 0.23 | –9.02 | <0.001* |

| Blocker × Verb | 1.67 | 0.32 | 5.26 | <0.001* |

6.3 Experiment 1b

Experiment 1b probes the processing of ziji with an intervening subject blocker in order to examine whether an external POV center impacts online antecedent retrieval.

6.3.1 Participants

Forty-eight Mandarin native speakers above 18 participated remotely on Ibex Farm (Drummond 2013). None had participated in Experiment 1a.

6.3.2 Procedure

The topic sentence and the target sentence were presented separately. Participants first read the topic sentence presented as a whole. They then pressed the space bar to read the target sentence word by word. Each key press revealed a new word, while the previous word was masked with a dash. Each sentence was followed by a comprehension question. On target trials, 12 questions out of 20 asked about who ziji refers to.2 The other 8 items asked unambiguous questions about context sentences to ensure that participants paid attention to the context. All filler items were followed by unambiguous questions as well. Participants’ responses to all the unambiguous questions were used to calculate their comprehension accuracy. The order of answer choices was randomized.

6.3.3 Predictions

The standard and the structure-based processing models make the same predictions: there should be a local binding bias in the blocker conditions and a LD binding bias in the non-blocker conditions. Recall that in online studies we use verb bias to diagnose local vs. LD interpretations. Therefore, we predict an interaction of Blocker type and Verb bias at or after the critical region ziji: In the blocker conditions, if non-local binding is blocked (i.e. local binding is preferred), we predict longer RTs with other-directed verbs which conflict with local readings of ziji. Conversely, in the non-blocker conditions, we predict longer RTs with self-directed verbs as they are incompatible with non-local readings.

6.3.4 Data analysis

Before data analysis, we decided that participants with less than 70% accuracy on comprehension questions would be excluded. Since everyone satisfied this criterion (mean accuracy: 93.75%), none were excluded. RTs shorter than 80ms or longer than 4000ms were removed. So were RTs longer than 2.5 SDs above the mean by region and condition. This resulted in the removal of 3.37% of the original data. We used mixed-effects models in R to analyze the data. Here, we report statistical results based on raw RTs. Analyses based on log-transformed RTs showed similar results (except for one region in Experiment 2c; we note the minor difference in the text).

6.3.5 Results

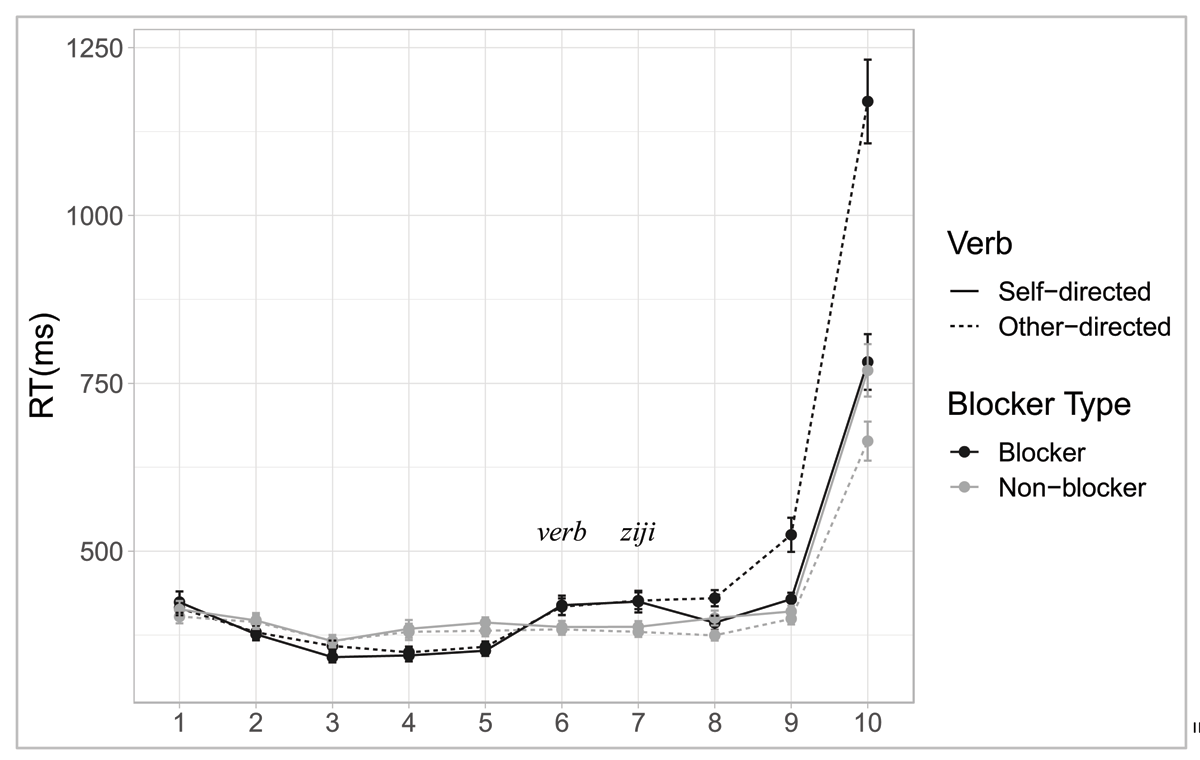

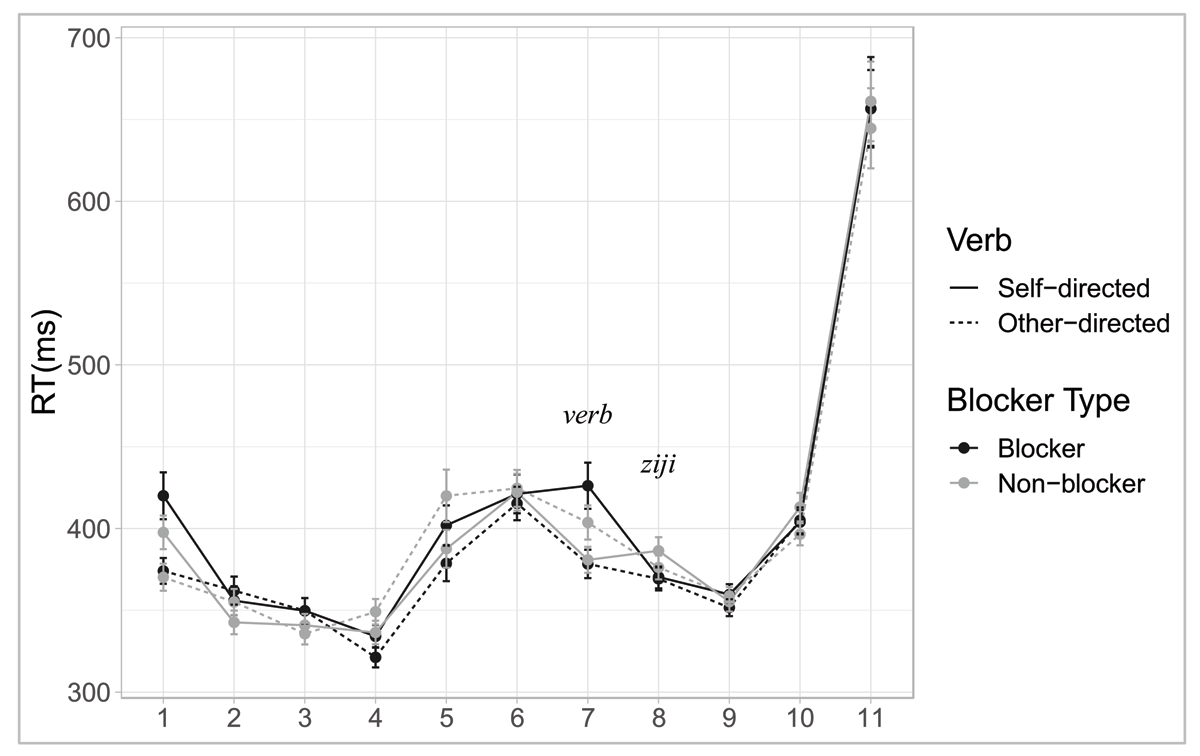

The mean RTs by condition and by region are plotted in Figure 3. See Table 2 for statistics. The critical region is Region 7, ziji. At the pre-critical regions, there was a main effect of Blocker type at Region 2, the matrix subject pronoun, probably a spurious effect as this word is constant across all conditions and Experiments 2b/2c did not show this effect. We also observed main effects of Blocker type at Region 4, the embedded subject, and Region 5, the adverbial (ps < 0.001): non-blocker conditions were read more slowly than the blocker conditions. This is expected as the third-person NP (e.g. Prof. Wang) has more syllables than the monosyllabic wo (‘I’). Intriguingly, at the embedded verb (Region 6) and the critical region ziji (Region 7), the main effect of Blocker type reversed (ps < 0.001). Now, the blocker conditions were read more slowly than the non-blocker conditions. We attribute this to the cost of perspective shift from the matrix subject to the first-person pronoun. This main effect of Blocker type persists till the end of the sentence (ps < 0.005).

Summary of statistics for RTs in Experiment 1b (*: <0.05).

| Blocker type | Verb bias | Blocker × Verb | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | |

| 1 | In lecture | 11.83 | 10.88 | 1.09 | 0.28 | –6.95 | 10.83 | –0.64 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 21.77 | 0.04 | 0.97 |

| 2 | he | –16.18 | 7.89 | –2.05 | 0.04* | 1.57 | 7.84 | 0.20 | 0.84 | –1.70 | 15.78 | –0.11 | 0.91 |

| 3 | heard | –12.50 | 7.02 | –1.78 | 0.08 | 8.05 | 6.99 | 1.15 | 0.25 | 14.98 | 14.04 | 1.07 | 0.29 |

| 4 | Prof.W/I | –33.64 | 9.33 | –3.61 | <0.001* | 2.04 | 9.31 | 0.22 | 0.83 | 6.88 | 18.66 | 0.37 | 0.71 |

| 5 | just | –32.36 | 6.35 | –5.09 | <0.001* | –3.67 | 6.33 | –0.58 | 0.56 | 19.87 | 12.71 | 1.56 | 0.12 |

| 6 | verb | 32.83 | 9.74 | 3.37 | <0.001* | –3.05 | 9.68 | –0.32 | 0.75 | –1.78 | 19.50 | –0.09 | 0.93 |

| 7 | ziji | 41.83 | 10.32 | 4.05 | <0.001* | 0.11 | 10.33 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 7.19 | 20.64 | 0.35 | 0.73 |

| 8 | DE | 25.38 | 9.14 | 2.78 | 0.006* | 6.35 | 9.09 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 57.58 | 18.26 | 3.15 | 0.002* |

| 9 | academic | 70.71 | 13.46 | 5.25 | <0.001* | 44.12 | 13.42 | 3.29 | 0.001* | 109.65 | 26.94 | 4.07 | <0.001* |

| 10 | paper | 256.98 | 41.41 | 6.21 | <0.001* | 145.43 | 41.29 | 3.52 | <0.001* | 503.56 | 82.84 | 6.08 | <0.001* |

At the critical region ziji, only the Blocker type main effect was significant (p < 0.001). Crucially, at Region 8, the first spillover region, a Blocker type by Verb bias interaction emerged (p = 0.002). Pairwise comparisons by Blocker type indicate that in the blocker conditions, other-directed verbs caused longer RTs (β = 36.41, SE =13.99, t = 2.60, p < 0.01), but in the non-blocker conditions, self-directed verbs lead to longer RTs (β = –24.86, SE = 11.72, t = –2.12, p = 0.035). This suggests that Mandarin natives preferred local binding when a subject blocker ‘I’ intervenes (hence struggle when other-directed verbs push for non-local binding) but preferred non-local binding in the non-blocker conditions (hence struggle when self-directed verbs push for local binding). This interaction persists in the next two regions (ps < 0.001). At the penultimate region, the verb bias effect in the non-blocker conditions did not reach significance (β = –11.72, SE = 9.82, t = –1.19, p = 0.23) although other-directed verbs lead to slowdowns in the blocker conditions (β = 98.86, SE = 24.88, t = 3.97, p < 0.001). At the final region, the contrasting verb bias effects were significant in both blocker conditions (β = 394.47, SE = 70.29, t = 5.61, p < 0.001) and non-blocker conditions (β = –103.34, SE = 43.34, t = –2.38, p = 0.018), matching the pattern at Region 8.

6.3.6 Discussion

Experiment 1 examined the blocking effect in Mandarin by using both online and offline methods. Experiment 1a aims to verify the blocking effect with the subject blocker ‘I’. Its secondary goal is to see whether verb bias semantics modulates the binding preference even in the presence of a blocker. Experiment 1b probes native speakers’ reading times to shed light on their real-time processing of ziji. In the offline forced-choice Experiment 1a, we operationalized the blocking effect as the local coreference advantage in the blocker conditions relative to the non-blocker conditions. The offline results support the view that the subject blocker ‘I’ makes LD binding more difficult. However, local binding was preferred only 46% of the time when the verb was other-directed. This indicates that verb semantics plays a crucial role in modulating the blocking effect.

Interestingly, Experiment 1a also showed a Blocker type by Verb bias interaction, such that the blocking effect only reached significance in the other-directed verb conditions but not in the self-directed conditions. We view this asymmetric blocking effect as providing additional evidence for the impact of verb semantics: the subject blocker ‘I’ will only be effective when participants have a strong tendency to establish LD dependencies. In the self-directed verb conditions, however, as participants mostly preferred local binding anyway, the blocker was not as effective. Only in the other-directed verb conditions was the subject blocker more effective in inducing blocking. One might notice that even in the self-directed/blocker condition, the mean proportion of local coreference (68%) is not close to ceiling. We attribute this to the presence of the topic sentence: According to the Topic Empathy Hierarchy, we expect the topic sentence to boost the likelihood of interpreting the non-local matrix subject as the antecedent of ziji.3 Note that the lower-than-expected proportion of local coreference choices does not impact our conclusions, which are based on relative differences between conditions.

In the self-paced reading Experiment 1b, we relied on verb bias effects as diagnostics for detecting local vs. LD binding preferences. The results revealed that antecedent retrieval is sensitive to discourse-level cues: the reading time differences between the self-directed and other-directed verb conditions in the non-blocker conditions signal that participants attempted to bind ziji to the discourse topic, the internal POV center. This is predicted by the standard cue-based and structure-based retrieval models alike, but inconsistent with a strong “syntax-first” approach which assumes that non-structural cues are invisible to the language parser at the early stage. We realize that this verb effect in Experiment 1b appeared at spillover regions and could be regarded as a late-stage effect (Sturt 2003). However, a structural effect, reflected as longer RTs with other-directed verbs in non-blocker conditions, is not observed at all (and we definitely see no signs of such an effect preceding the discourse-level effect). In addition, as we will see, in Experiment 2c, the discourse-level effect appears slightly earlier at the critical region in non-blocker conditions (see Badecker & Straub (2002) for evidence that slight variation can exist regarding the onset of predicted effects during self-paced reading). Therefore, we tentatively conclude that prominent discourse-level cues are immediately available for antecedent retrieval during the real-time processing of ziji.

Furthermore, the reading times provide strong evidence that when a local subject blocker ‘I’ is present, participants prefer local binding. This is shown by reading slowdowns at the spillover regions preceded by other-directed verbs (where verb semantics biases non-local binding) compared to self-directed verbs (where verb semantics biases local binding). At this stage, we speculate that local binding is preferred presumably due to two reasons. First, the blocker ‘I’ matches the [+POV] cue encoded on ziji (as we shall see later, the syntactic [+SUB] cue matters as well) and thus interferes with LD binding by a non-local matrix subject (internal POV center) which matches the same set of cues. Second, according to linguistic accounts (e.g. Kuno 1987; Pan 2001; Charnavel et al. 2017), people are more prone to take the perspective of first-person pronouns than third-person NPs. In other words, the blocker is relatively more activated than the matrix subject,4 hence the preference for local binding.

Overall, Experiment 1a indicates that the blocking effect is influenced by both blocker type and verb semantics. Thus, the “blocking effect” may be better viewed as a defeasible constraint. Furthermore, results from Experiment 1b suggest that online antecedent retrieval is sensitive to discourse-level cues, and that subject blockers bias participants towards local binding of ziji. However, Experiment 1b does not inform us whether it is the discourse-level cue [+POV] alone that induces blocking, because the subject blocker ‘I’ also encodes [+SUB]. It could be that the [+POV] cue is visible only because it is in a syntactically prominent subject position. What will happen if the blocker is in an object position? We turn to this question in Experiment 2.

7 Experiment 2: Object blocker

Experiment 2 has three parts. Experiment 2a is a forced-choice task aiming to replicate the observation by Xue et al. (1994) and others (e.g. Huang & Liu 2001; Huang et al. 2009) that the object-position blocker ‘me’ can also block LD binding of ziji. To the extent that a blocking effect is indeed found with an object blocker, we ask how strong the object blocking effect is compared to subject blocking. This will inform us whether syntactic prominence plays any role in modulating the blocking effect. Experiments 2b/2c are self-paced reading experiments. The main goal of these experiments is to see whether the [+POV] cue alone – in the absence of the [+SUB] cue – leads to an online blocking effect.

7.1 Materials

The design was the same as Experiment 1 (Blocker type (blocker/non-blocker) × Verb bias (self-directed/other-directed)). Stimuli from Experiment 1 were minimally changed to create the stimuli in Experiment 2. To add the object blocker, sentence structure was changed as illustrated in (12). In the blocker conditions, the blocker wo (‘me’) is the object of the matrix clause. In the non-blocker conditions, we replaced wo with referentially simple disyllabic words such as bieren (‘others’) and dajia (‘everyone’). The local antecedents remain constant across conditions. Note that in Experiment 2c, the adverbial region was removed (more below). Otherwise, Experiment 2c was identical to Experiment 2b.

- (12)

- a.

- Blocker/Self-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí

- class

- lǐ

- in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- gàosù

- tell

- wǒ

- 1sg

- Wáng

- Prof.

- jiàoshoù

- Wang

- gānggāng

- just

- fābiǎo-le

- publish-perf

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he told me that Prof. Wang had just published self’s academic paper.’

- b.

- Blocker/Other-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí-lǐ

- class in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- gàosù

- tell

- wǒ

- 1sg

- Wáng

- Prof.

- jiàoshoù

- Wang

- gānggāng

- just

- pīgaǐ-le

- grade-PERF

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he told me that Prof. Wang had just graded self’s academic paper.’

- c.

- Non-blocker/Self-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí-lǐ

- class in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- gàosù

- tell

- biérén

- others

- Wáng

- Prof.

- jiàoshoù

- Wang

- gānggāng

- just

- fābiǎo-le

- publish-PERF

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he told others that Prof. Wang had just published self’s academic paper.’

- d.

- Non-blocker/Other-directed verb

- Xiǎomíng

- Xiaoming

- shì

- be

- bānjí-lǐ

- class in

- de

- de

- yōuxiù

- good

- xuéshēng.

- student

- Kè

- lecture

- shàng,

- on

- tā

- 3sg

- gàosù

- tell

- biérén

- others

- Wáng

- Prof.

- jiàoshoù

- Wang

- gānggāng

- just

- pīgaǐ-le

- grade-PERF

- zìjǐ

- self

- de

- de

- xuéshù

- academic

- lùnwén.

- paper

- ‘Xiaoming is a good student in the class. During the lecture, he told others that Prof. Wang had just graded self’s academic paper.’

7.2 Experiment 2a

To test whether an object blocker blocks LD binding of ziji, we conducted a forced-choice judgment experiment. The results of this experiment will be compared to the results from Experiment 1a to examine the role of syntactic prominence in blocking.

7.2.1 Participants

Forty-eight Mandarin native speakers above 18 participated in the experiment. None had participated in any previous experiment.

7.2.2 Procedure

The procedure was the same as Experiment 1a.

7.2.3 Predictions

The syntax-based account predicts that an object blocker will not induce the blocking effect. In contrast, the perspective-based and the unified accounts predict a main effect of Blocker type. However, the latter two differ regarding the strength of blocking. The perspective-based account does not predict any difference between subject and object blocking, while the unified account predicts stronger blocking with the subject blocker ‘I’ than with the object blocker ‘me’. We also predict a main effect of verb bias.

7.2.4 Data analysis

Data analysis for this experiment was the same as in Experiment 1a.

7.2.5 Results

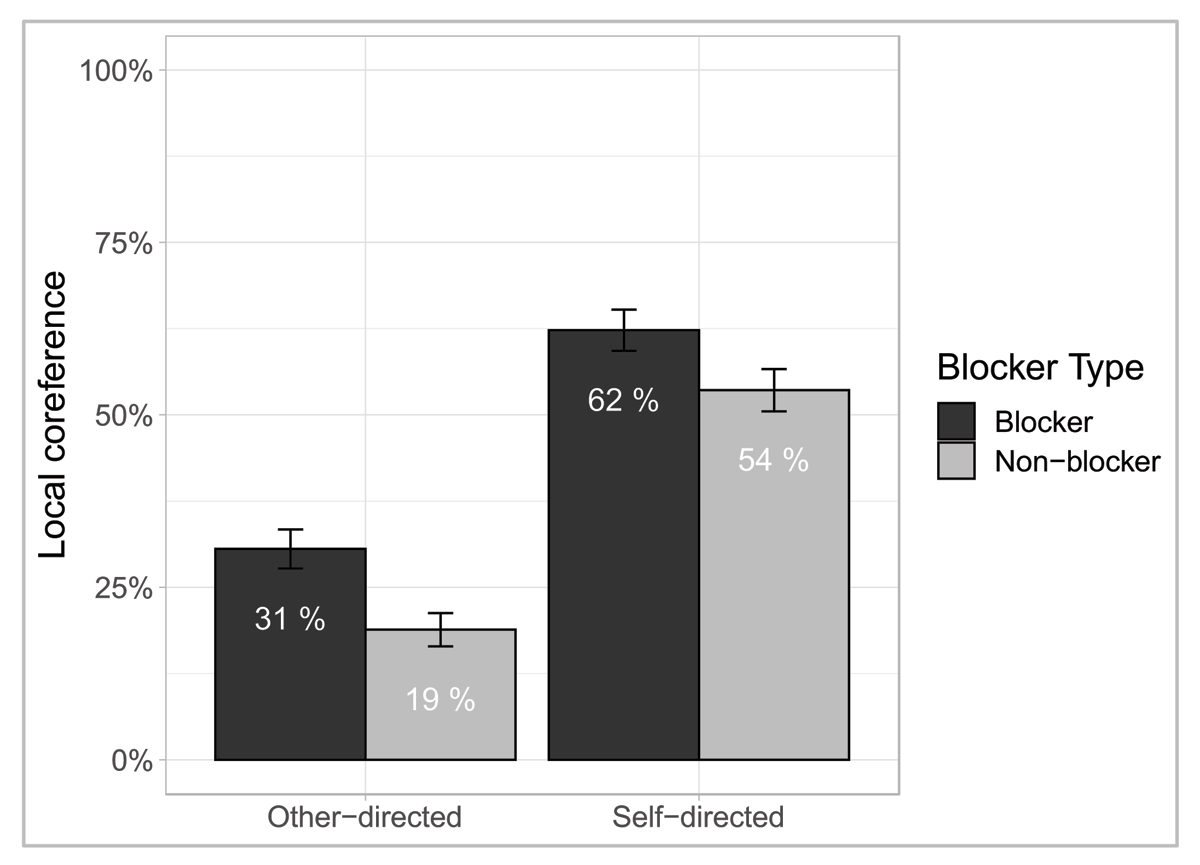

Figure 4 displays participants’ mean preference for local binding of ziji across conditions. See Table 3 for statistical analysis. We found main effects of Blocker type and Verb bias (ps < 0.001). The blocker conditions lead to higher percentages of local binding regardless of verb bias. The overall low tendency for local binding even in the self-directed/blocker condition echoes Experiment 1a, where we argue that the context sentence boosts non-local interpretations (thus suppressing local interpretations) to some extent. Note that the symmetrical pattern in Figure 4 differs from the asymmetric pattern in Experiment 1a, a point we will return to in the discussion. The main effect of Verb bias indicates that verb semantics plays a crucial role in determining the binding of ziji (p < 0.001). As in Experiment 1a, a verb bias effect emerged between the two blocker conditions as well: other-directed verbs lead to a decreased tendency for local binding compared to self-directed verbs (31% vs. 62%, β = –1.53, SE = 0.21, t = –7.35, p < 0.001). This strengthens our view that verb semantics modulates the blocking effect. The Blocker type by Verb bias interaction was not significant. Overall, Experiment 2a shows that the object blocker ‘me’ induces a blocking effect, which is unexpected under a syntactic account.

Summary of statistics for Experiment 2a (*: <0.05).

| β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blocker type | 0.56 | 0.15 | 3.82 | <0.001* |

| Verb bias | –1.69 | 0.15 | –11.16 | <0.001* |

| Blocker × Verb | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.81 | 0.42 |

Next, we compare the strengths of subject blocking (Experiment 1a) and object blocking (Experiment 2a). To this end, we included Blocker position (subject (Exp1a) vs. object (Exp 2a)) as a between-experiment factor (contrast coding: Object = +0.5, Subject = –0.5). See Table 4 for statistics. We found a three-way interaction of Blocker type, Verb bias, and Blocker position (p < 0.001). To better understand the interaction, we examined the blocking effect by blocker positions within each verb bias type. A significant interaction of Blocker type and Blocker position would suggest that the strength of blocking effect varies as a function of the blocker position. Statistical analysis indicated that with self-directed verbs, the blocking effect of the syntactically less prominent ‘me’ seems to be stronger than ‘I’ due to a marginally significant interaction (β = 0.56, SE = 0.29, t = 1.94, p = 0.05). This seems to contradict the unified account which predicts the opposite. But as we mention in the discussion below, this is presumably related to the matrix verb difference (e.g. ‘heard’ vs. ‘told’) in Experiments 1 and 2. If we follow Huang and Liu (2001) by assuming that LD ziji shows logophoric properties, this result falls out naturally. Crucially, statistical analysis also showed the Blocker type by Blocker position interaction to be significant in the other-directed verb conditions (β = –0.99, SE = 0.32, t = –3.11, p = 0.002). This suggests that the syntactically prominent subject blocker induced a stronger blocking effect than the object blocker when the verb semantics biases non-local antecedents, matching the prediction of the unified account but not that of the perspective-based account.

Summary of statistics for between-experiment comparison (*: <0.05).

| β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blocker type | 0.65 | 0.11 | 6.13 | <0.001* |

| Verb bias | –1.80 | 0.11 | –16.34 | <0.001* |

| Blocker position | –0.46 | 0.16 | –2.81 | 0.005* |

| Blocker × Verb | 0.92 | 0.21 | 4.39 | <0.001* |

| Blocker × Position | –0.19 | 0.21 | –0.92 | 0.36 |

| Verb × Position | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.87 | 0.38 |

| Blocker × Verb × Position | –1.43 | 0.42 | –3.41 | <0.001* |

7.3 Experiment 2b

Experiment 2b examines whether the object blocker ‘me’ leads to a preference for local binding in real-time processing. The results from this experiment will inform us whether antecedent retrieval is sensitive to the [+POV] cue alone when the [+SUB] cue does not coincide with it.

7.3.1 Participants

Seventy-six Mandarin native speakers above 18 participated in this experiment. None had not participated in any previous experiment.

7.3.2 Procedure

The procedure was the same as in Experiment 1b.

7.3.3 Predictions

As we previously discovered that the blocking effect has a syntactic component (i.e. subject blocking stronger effect than object blocking), the standard cue-based and the structure-based retrieval models make different predictions regarding native speakers’ online processing patterns (see Figure 1 in Section 3). The standard model predicts that LD binding should be preferred in the non-blocker conditions but less preferred or even unavailable in the blocker conditions. Therefore, a significant Blocker type by Verb bias interaction at the critical region ziji is expected. In contrast, the structure-based model predicts that object blockers in syntactically illegitimate positions will not interfere with LD binding of ziji. Therefore, the structure-based model only predicts a main effect of Verb bias (i.e. longer RTs with self-directed verbs) at ziji.

7.3.3 Data analysis

As in Experiment 1b, we removed participants whose comprehension accuracy fell below the 70% threshold. Eight participants failed to meet this criterion. The remaining 68 participants had a mean accuracy rate of 90.91%. We then filtered out RTs 2.5 SDs above the mean by region and condition, which resulted in the removal of 2.45% of the original data. We used mixed-effect regression to analyze the RTs.

7.3.4 Results

The mean RTs by condition and region are plotted in Figure 5. See Table 5 for statistics. The critical region is Region 8, ziji. Among all the regions, only the pre-critical Region 7, the biased verb, showed a Blocker type by Verb bias interaction (p < 0.001). The early timing of this effect was not predicted although it is not surprising given similar findings from self-paced reading (Chen et al. 2012) and eye-tracking (Jäger et al. 2015; Chang et al. 2020), presumably because participants anticipated the onset of ziji at the biased verb region due to the predictability of the stimuli after repeated trials.

Summary of statistics for RTs in Experiment 1b (*: <0.05).

| Blocker type | Verb bias | Blocker × Verb | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | |

| 1 | In lecture | 4.41 | 4.85 | 0.91 | 0.37 | 8.78 | 5.01 | 1.75 | 0.08 | –4.85 | 9.28 | –0.52 | 0.60 |

| 2 | he | 10.03 | 7.68 | 1.31 | 0.21 | –7.89 | 7.09 | –1.11 | 0.27 | 4.64 | 12.93 | 0.36 | 0.72 |

| 3 | tell | 10.29 | 6.40 | 1.61 | 0.12 | 2.74 | 5.45 | 0.50 | 0.61 | –3.17 | 10.90 | –0.29 | 0.77 |

| 4 | others/me | –6.58 | 4.26 | –1.55 | 0.12 | –0.33 | 4.26 | –0.08 | 0.94 | 6.16 | 8.54 | 0.72 | 0.47 |

| 5 | Prof.W | –2.61 | 5.52 | –0.47 | 0.63 | 6.42 | 5.52 | 1.16 | 0.25 | 16.54 | 11.04 | 1.50 | 0.13 |

| 6 | just | –6.31 | 8.98 | –0.70 | 0.48 | 1.46 | 8.98 | 0.16 | 0.87 | 9.47 | 17.96 | 0.53 | 0.60 |

| 7 | verb | 8.36 | 9.21 | 0.91 | 0.36 | 12.48 | 9.21 | 1.36 | 0.18 | 71.45 | 18.42 | 3.88 | <0.001* |

| 8 | ziji | –6.35 | 8.94 | –0.71 | 0.47 | 1.40 | 9.65 | 0.15 | 0.88 | 9.46 | 17.89 | 0.53 | 0.59 |

| 9 | DE | –0.70 | 4.45 | –0.16 | 0.87 | 1.74 | 4.45 | 0.39 | 0.70 | 10.88 | 8.91 | 1.22 | 0.22 |

| 10 | academic | 0.02 | 6.33 | 0.003 | 0.99 | 6.88 | 6.33 | 1.09 | 0.28 | –16.88 | 12.67 | –1.33 | 0.18 |

| 11 | paper | 4.27 | 21.08 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 1.73 | 21.08 | 0.08 | 0.93 | –16.00 | 42.16 | –0.38 | 0.70 |

However, a closer look at this interaction shows that it is not the one predicted by the standard cue-based approach. In the blocker conditions, self-directed verbs caused RT slowdowns (β = 47.51, SE = 15.04, t = 3.16, p = 0.002), while in the non-blocker conditions other-directed verbs that lead to slowdowns (β = –22.39, SE = 10.77, t = –2.08, p = 0.038). This pattern suggests that participants preferred non-local binding when the (potential) object blocker ‘me’ was present (hence struggled when self-directed verbs pushed for local binding) and preferred local binding when there was no first-person blocker (hence struggled when other-directed verbs pushed for non-local binding).

This shows that the (potential) blocker ‘me’ actually did not induce blocking during real-time processing (as we have evidence of participants considering non-local readings in the blocker conditions). This is consistent with the predictions of the structure-based account, but not the standard cue-based retrieval account.

Second, the mysterious “blocking effect” in the non-blocker conditions is unexpected, but it’s worth noting that this effect is not significant in the log-transformed-RT analysis (β = –0.03, SE = 0.02, t = –1.28, p = 0.20), so we should not read too much into it. We suggest an explanation in the Discussion below, which will motivate a modified Experiment 2c.

7.3.6 Discussion

Experiment 2a and 2b test the blocking effect with the object blocker ‘me’. The syntax-based account predicts that a blocker in object position cannot block LD binding of ziji by a discourse topic. In contrast, the perspective-based and unified accounts acknowledging the logophoric properties of ziji (i.e. sensitive to POV centers) allow for blocking effects with object blockers. The forced-choice judgment results from Experiment 2a support the latter accounts. However, by comparing the offline results in Experiments 1a and 2a, we found that the blocking effect is stronger with subject blockers. We take this as evidence that both perspective-taking and syntactic prominence are involved in blocking, in line with the unified account.5

There are two other discoveries worthy of notice. First, the strength of the blocking effect depends on verb semantics. Experiment 2a showed – echoing Experiment 1a – that if the verb is other-directed, even with an object blocker, the mean preference for local antecedents was only 31%.

Second, the blocking effect in Experiment 2a is symmetrical, unlike the asymmetric pattern in Experiment 1a. In Experiment 1a, we suggested that if the verb is self-directed, the blocker is largely ineffective in blocking LD binding as participants mostly only considered local binding. In Experiment 2a, the matrix verb was changed to a source verb ‘told’ instead of a mixture of perceiver and source verbs (e.g. ‘heard’, ‘said’, ‘noticed’, etc.). Since ziji was interpreted logophorically given a discourse topic, a Source conceivably attracted some of the antecedent choices in Experiment 2a even when the verb was self-directed. This increased tendency for non-local binding was neutralized in the blocker conditions but not in the non-blocker conditions, hence the symmetrical blocking pattern in Experiment 2a. In fact, previous experimental work has corroborated this verb-related logophoricity effect in the case of English reflexive himself/herself (Kaiser et al. 2009; Sloggett 2017). Although we are not aware of any related work in Mandarin, it is reasonable to expect this effect to also occur with perspective-sensitive ziji given its logophoric properties (e.g. Huang & Liu, 2001; Huang et al., 2009).

The self-paced reading Experiment 2b tests whether the discourse-level cue [+POV] alone suffices to influence real-time antecedent retrieval in a context where the [+POV] antecedent lacks the [+SUB] feature, as it is an object. The standard retrieval model predicts different verb bias effects for the object blocker and non-blocker conditions, while the structure-based model predicts similar verb bias effects. Intriguingly, the reading time patterns do differ between the blocker and non-blocker conditions, but not in a way predicted by the standard model. We found that native speakers preferred non-local binding in the blocker conditions and local binding in the non-blocker conditions. Nevertheless, the absence of blocking by a (potential) object blocker during real-time processing is consistent with the prediction of the structure-based retrieval model, but not the standard cue-based retrieval model. Note that the absence of the blocking effect in online parsing contrasts with the weak blocking effect in the offline data from Experiment 2a. This difference suggests that a pure discourse-level blocking effect may emerge later on during processing. (The structure-based model does not speak directly to this, see Section 4).

However, neither model predicts the tendency for local binding with non-blockers. This may be related to working memory burden due to similarity-based interference and dependency length. The accessibility of NPs is known to depend on whether there is interference from other similar NPs (Gordon et al. 2001; 2004; 2006) and referential complexity (Warren & Gibson 2002). In the non-blocker conditions, there are three third-person NPs (e.g. ‘he’, ‘others’, ‘Prof. Wang’) whereas in the blocker conditions, there are only two. Thus, the presence of three third-person NPs in working memory potentially makes sentence processing challenging. This challenge might be compounded by the long distance between the discourse topic and the reflexive (7 words compared to 6 in Experiment 1b). Therefore, in Experiment 2c, we would like to replicate Experiment 2b with a slightly simpler design by removing the adverbial region.

7.4 Experiment 2c

Experiment 2c has two aims. First, we want to test whether native speakers prefer non-local binding in the non-blocker conditions when the sentences are simpler (without adverbials). Second, we would like to replicate the reading time pattern in the blocker conditions observed in Experiment 2b.

7.4.1 Participants

Sixty-two adult Mandarin native speakers participated. None had participated in any previous experiment.

7.4.2 Procedure

The procedure for Experiment 2c was the same as in Experiment 2b.

7.4.3 Predictions

If the removal of the adverbial alleviates participants’ working memory burden, we predict a main effect of Verb bias across (non-)blocker conditions such that self-directed verbs lead to reading slowdowns at either the pre-critical verb region or the critical region ziji.

7.4.4 Data analysis

No participant was removed as all participants passed the 70% threshold with a mean accuracy of 92.51%. After the removal of RTs 2.5 SD above the mean by region and condition, 97.27% of the original data were entered into statistical analysis.

7.4.5 Results

The mean RTs by condition and region are in Figure 6. See Table 6 for statistics. Prior to the critical region ziji, there were no significant effects. At the critical region, a main effect of Verb bias emerged (p < 0.001): self-directed verbs lead to longer RTs than other-directed verbs, consistent with the prediction of the structure-based retrieval model. For the spillover regions, Region 10 showed a Verb bias main effect (p < 0.001) and a Blocker type by Verb bias interaction (ps < 0.005). This late interaction should not be taken as supporting evidence for the standard cue-based retrieval model, so we will not discuss it in detail. It appeared because self-directed verbs lead to significant reading slowdowns in the non-blocker conditions (β = –202.95, SE = 37.97, t = –5.35, p < 0.001), but no verb bias effect was found within the blocker conditions (β = –35.18, SE = 46.71, t = –0.75, p = 0.45). Overall, Experiment 2c replicates Experiment 2b on the absence of object blocking.

Summary of statistics for RTs in Experiment 2c (*: <0.05).

| Blocker type | Verb bias | Blocker × Verb | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | |

| 1 | In lecture | –2.31 | 8.84 | –0.26 | 0.79 | –1.16 | 8.85 | –0.13 | 0.89 | 14.78 | 17.68 | 0.84 | 0.40 |

| 2 | he | –6.71 | 6.89 | –0.97 | 0.33 | –1.80 | 6.89 | –0.26 | 0.79 | 6.67 | 13.77 | 0.49 | 0.62 |

| 3 | tell | –3.68 | 6.61 | –0.56 | 0.58 | –6.97 | 6.61 | –1.06 | 0.29 | 6.35 | 13.21 | 0.48 | 0.63 |

| 4 | others/me | 4.16 | 6.38 | 0.65 | 0.51 | –3.58 | 6.38 | –0.56 | 0.58 | 18.40 | 12.76 | 1.44 | 0.15 |

| 5 | Prof.W | 4.72 | 5.67 | 0.83 | 0.41 | –6.05 | 5.65 | –1.07 | 0.29 | –11.15 | 11.33 | –0.98 | 0.33 |

| 6 | verb | 1.99 | 7.40 | 0.27 | 0.78 | 13.08 | 7.40 | 1.76 | 0.08 | 17.25 | 14.81 | 1.17 | 0.24 |

| 7 | ziji | –5.91 | 8.61 | –0.69 | 0.49 | –32.33 | 8.61 | –3.76 | <0.001* | –10.41 | 17.21 | –0.61 | 0.55 |

| 8 | DE | –1.65 | 6.13 | –0.27 | 0.79 | 4.57 | 6.13 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 15.72 | 12.26 | 1.28 | 0.20 |

| 9 | academic | 14.82 | 8.93 | 1.72 | 0.10 | 4.35 | 7.88 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 23.22 | 14.28 | 1.67 | 0.10 |

| 10 | paper | 46.58 | 29.84 | 1.56 | 0.12 | –116.32 | 29.85 | –3.89 | <0.001* | 173.01 | 59.68 | 2.90 | <0.005* |

7.4.6 Discussion

Experiment 2c improved upon Experiment 2b by eliminating the adverbial region to reduce participants’ potential working memory burden. This move proved to be effective: we now find that in the non-blocker conditions, participants preferred non-local binding very early at the critical region ziji, as expected. This suggests that the unexpected (and statistically unstable) result for verb bias effects in the non-blocker conditions in Experiment 2b is indeed likely to be due to memory load or some other factor unrelated to blocking. Crucially, for the blocker conditions, Experiment 2c replicates the reading time patterns from in Experiment 2b, in stark contrast with the reading time results in Experiment 1b with subject blockers. In summary, together with Experiment 1b and 2b, Experiment 2c provides evidence supporting the unified approach and the structure-based retrieval model.

8 General discussion

The two sets of experiments reported in this study investigated the blocking effect associated with ziji. This work has three main aims. First, we aim to test the strength of the blocking effect with subject and object blockers to shed light on linguistic accounts of blocking. Doing so allows us to see whether there is a syntactic component to this phenomenon. Second, in addition to the syntactic effect, we would like to explore whether lexical semantics plays any role in modulating the blocking effect. Third, we intend to test the standard and structure-based retrieval models with regard to their ability to correctly predict the outcome of the online experiments. These goals were accomplished step by step. We first examined the offline and online processing patterns in Experiment 1 with the subject blocker ‘I’. Next, we replaced the subject blocker with an object blocker ‘me’ in Experiment 2 to see whether the strength of the blocking effect varies. In the following sections, we first summarize the research findings and then discuss the wider issues related to this work.

8.1 Summary of results

In Experiment 1 with subject blocking, an offline forced-choice judgment experiment showed an asymmetric blocking effect: subject blockers only lead to stronger tendency for local binding with other-directed verbs. As explained earlier, this is presumably because participants did not consider LD binding as often in self-directed verb conditions, rendering the blocker ineffective. Although Experiment 1a provides evidence for blocking, it suggests that blocking is not absolute. In fact, verb bias played an important role: in the blocker conditions, the average local binding preference was significantly reduced from 68% with self-directed verbs to 46% with other-directed verbs.

The self-paced reading Experiment 1b yielded two major findings. First, the inclusion of a discourse topic, which we assume introduces a POV center following Kuno (1987), was successful in biasing participants towards the discourse topic (POV center) when no blocker was present, indicated by longer RTs elicited by self-directed verbs at the spillover region. This anti-locality bias stands in contrast to the locality bias reported in previous studies without contexts (e.g. Gao et al. 2005; Jäger et al. 2015; Dillon et al. 2016; He & Kaiser 2016; Wang 2017) and suggests that, in the presence of a discourse topic/POV center, Mandarin natives prefer to interpret ziji as a logophoric reflexive, not a syntactic one.

Importantly, in the blocker conditions, participants displayed reading time slowdowns at the spillover region when the verb was other-directed. The cause for this verb bias effect was probably due to a clash in expectations. The conflict between the expectation for local binding in the presence of a subject blocker and the semantic bias favoring a non-local antecedent lead to processing difficulty. According to both standard and structure-based retrieval models, this is due to complete feature overlaps between the structurally/linearly closer subject blocker and logophoric ziji. Thus, the reading time results are consistent with these two retrieval models acknowledging early access to discourse-level cues, but not with a “syntax-first” model that precludes access to non-syntactic cues. Overall, Experiments 1a and 1b suggest that subject blockers trigger blocking effects during online antecedent retrieval, and that blocking effects are strongly modulated by verb semantics.

Experiment 2 investigated the blocking effect with the object blocker ‘me’ in an attempt to examine the three linguistic theories on blocking and the two sentence processing models. The syntax-based account predicts no object blocking effect while the unified account predicts weaker blocking with object blockers. To verify these linguistic accounts, we conducted an offline forced-choice judgment experiment and found that, compared to non-blockers, an object blocker ‘me’ did elicit a stronger tendency for local binding. However, the object blocking effect in Experiment 2a was significantly weaker than in Experiment 1a with subject blockers. This constitutes strong evidence that the blocking effect is sensitive to syntactic prominence, consistent with the unified account. However, a caveat is in order. The evidence presented in this paper only shows that syntactic prominence can modulate blocking; it does not directly inform us whether a particular syntactic formulation (e.g. LF movement) is correct. Therefore, this paper is not committed to any specific syntactic analysis proposed in the unified account, but simply shows that a linguistic theory taking both syntax and discourse-pragmatics into account is superior to pure syntax-based or pure perspective-based accounts.

Given that the blocking effect is tied to syntactic prominence (subject vs. object), we then examined whether an object blocker leads to online blocking similarly to Experiment 1b. Results from self-paced reading experiments could inform us about the validity of the standard and structure-based models. Reading time patterns from Experiment 2b revealed that self-directed verbs caused reading slowdowns at the pre-critical verb region in the blocker conditions, suggesting a general tendency for non-local binding. This runs counter to the prediction of the standard model which assumes that all cues are accessible for antecedent retrieval. As the external POV center ‘me’ encodes the feature [+POV], a weak blocking effect is predicted to occur, contrary to our findings. Unexpectedly, in the non-blocker conditions, participants demonstrated a preference for local binding. Neither model predicts this pattern. We reasoned that this could be due to retrieval difficulty related to similarity-based interference among the three NPs in the sentence, exacerbated by the distance between ziji and the discourse topic. To address this issue, we simplified the sentences by removing all adverbials and reran the experiment. In the follow-up Experiment 2c, we replicated the tendency for non-local binding with object blockers at the critical region ziji, strengthening the conclusion that only syntactically prominent POV centers can cause blocking. Furthermore, with adverbials removed, we found a non-local binding preference in the non-blocker conditions as well. Therefore, the reading time results in this study are fully congruent with the prediction of the structure-based model but not with the standard model.