1. Introduction

In mainstream general linguistics, there is a tendency to regard descriptive studies of individual languages as a second-grade task subordinate to the main job, which is that of theoretical interpretation. A descriptive paper, however precise and correct it may be in the presentation of the language data, hardly has a chance of being accepted to a prestigious linguistic journal if it does not “contain theoretical implications that shed light on the nature of language and the language faculty”.1 It would be ridiculous to combat this principle: general linguistics is primarily about Language, and the countless descriptive papers which are produced are of minor interest to non-specialists in the given language. There are journals specializing in individual languages or groups of languages; publication of such papers would be more appropriate in those less central journals.

However, the converse question can be asked: if a paper is well structured and logically consistent, and contains numerous references to theoretical works, is it a venial sin for it to ignore the existing literature on the language in question?

I do not pretend to give a final answer to this question. I even assume that there is no final answer, or that answers may vary considerably, depending on the context. However, I would like to draw the attention of colleagues to the problems a study may run into if the authors disregard previous publications dealing with the language in question and the solutions already advanced by their predecessors.

I am going to illustrate this simple point with a critical review of a paper recently published in Glossa, (Baker & Gondo 2020), dealing with possessive constructions involving deverbal and deadjectival nouns in Dan. In brief, the central idea of the paper by Baker & Gondo can be represented as follows: in Dan, there are two different possessive constructions, proper to relational and non-relational nouns respectively. When a verb is nominalized, its theme argument is expressed like the possessor of a relational noun, whereas when an adjective is nominalized, its theme argument is expressed like the possessor of a nonrelational noun. This difference is explained using Baker’s theory of lexical categories, according to which verbs intrinsically combine directly with a theme argument, whereas adjectives do not, but only become predicates of a theme argument with the help of a functional head Pred.

In this paper, I will firstly (Section 2) make a short presentation of the Dan language and its dialects and basic information on the morphosyntax of Eastern Dan (aspects not relevant for the present study will not be dealt with). Then a survey of the paper by Baker & Gondo will be given and its main ideas will be recapitulated (section 3). Further on, the main theses of Baker & Gondo’s paper will be critically analyzed. In Section 4 it will be shown that the formal distinction between nouns, adjectives and verbs in Dan suggested by Baker and Gondo is valid, but the criteria they provide are unsuitable. In Section 5, Baker & Gondo’s syntactic interpretation of possessive constructions with marker ɓa will be criticized; it will be shown that this marker would be better analyzed as a postposition. In Section 6, the key ideas of Baker & Gondo will be considered, namely, the different possessive constructions with nominalization. It will be shown that possessive constructions both with and without possessive marker ɓa are possible for deadjectival nouns; the main factor in the distribution of these two types of constructions is apparently the agentivity of the possessor. This factor also seems to be valid for possessive constructions with deverbal nouns. In section 7, high nominalization constructions will be considered. Special attention will be paid to a tonal morpheme marking high nominalization (disregarded by Baker and Gondo). My conclusions will be presented in Section 8.

In what follows, in the language examples from Baker & Gondo the orthography of these authors is preserved; the numbers of their examples are also retained and are preceded with the letters “BG”. However, in order to facilitate navigation, my continuous numbering of examples is also maintained; therefore, Baker & Gondo’s examples all have pairs of numbers separated by a slash, e.g.: (16/BG37). In my language examples, a phonological transcription is used.

2. Background information on Dan (with special emphasis on Eastern Dan)

2.1. Dialects of Dan

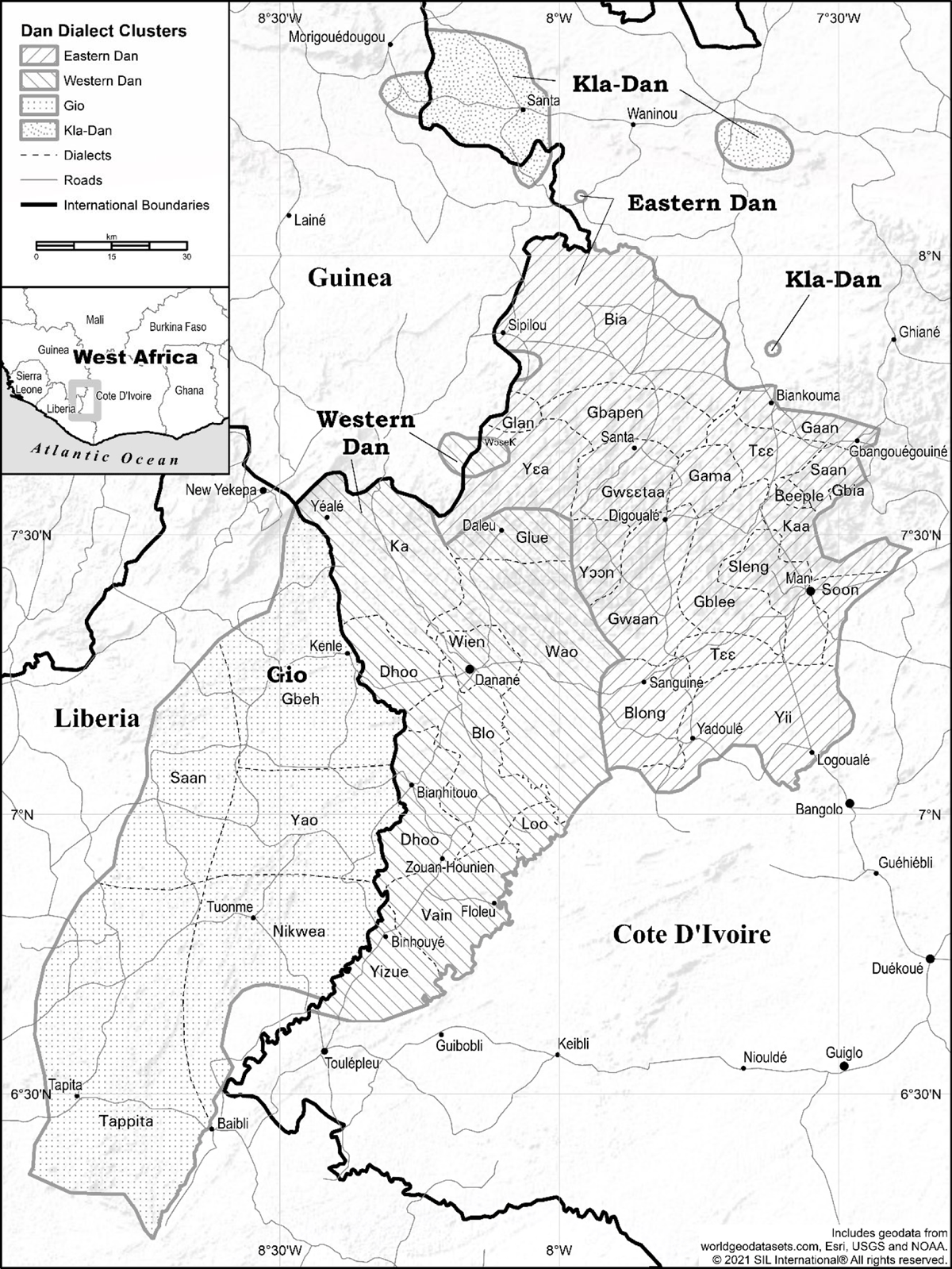

Dan (South Mande < Southeastern Mande < Mande < Niger-Congo) is a macrolanguage spoken in Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Guinea by about 1,600,000 people (2012, my evaluation).2 The total number of Dan dialects is approximately 35, see Figure 1. In Liberia, Dan is known under the name of Gio; in Côte d’Ivoire Dan is most often referred to as Yakuba (Yacouba). Since the 1960s, two distinct written norms have been elaborated in Côte d’Ivoire: Western Dan, based on the Blo dialect, and Eastern Dan, based on the Gwɛɛtaa dialect (sousprefecture of Santa, prefecture of Biancouma, Tonkpi province). There is also a northern variety of Kla-Dan which is different enough from Eastern Dan to be regarded as a separate language.

In the introduction to (Baker & Gondo 2020) it is said that the Dan dialect under study is that of Man (the main administrative center of the Dan country in Côte d’Ivoire): “see Gondo (2016) for the first extended study of the Man dialect, which we investigate here”.3 In fact, in Gondo’s PhD dissertation it is the dialect of Gble or Gblewo (in Dan, Gblʌ̀ʌ̀ or Gblʌ̀ʌ̀wȍ; wȍ means ‘language, dialect’) that is concerned, Bleu Gildas Gondo being a native speaker of this variety. Evidently, Gble data have also been used for the 2020 article. This dialect belongs to Eastern Dan, and is spoken to the west and northwest of Man, at some distance from the city. It is true that all of the Eastern Dan dialects are more or less mutually intelligible, but it is not accurate to refer to Gble as “the dialect of Man”: the dialects whose areas are immediately adjacent to Man are Sleng, Soon and Kaa (Slʌ̋ŋ̏, Sɒ̰̋ɒ̰̏, Kȁȁ), see Figure 1.

It should be mentioned that most of the data for Eastern Dan published so far stem from the Dan-Gwɛɛtaa (Gwɛ̋ɛ̏tàà) dialect, and most of my unpublished data are from this dialect too. Eastern Dan has a written tradition and a codified orthography (some publications are available in the Dan Electronic Library, http://cormand.huma-num.fr/danbiblio/index.php). In what follows, I will operate with the data of the Gwɛɛtaa dialect (unless otherwise specified). Differences between the Gwɛɛtaa and Gble dialects have no impact on the points discussed in this paper; nevertheless, such differences will be mentioned and discussed whenever they may be relevant.

2.2. Segmental phonology and tones

Eastern Dan has 12 to 15 oral and 9 nasal vowels,4 and a vowel ŋ with limited distribution. A remarkable feature of the consonantal system is the presence of two implosive phonemes, ɓ and ɗ, which are realized as [m] and [n] respectively before nasal vowels or after ŋ. In the same way, the sonorants y, w are realized in nasal contexts as [ɲ] and [w̃] respectively. This means that the nasal consonants m, n, ɲ, w̃ have no phonological status in Dan; they will not be represented in my transcription (although m, n appear in examples taken from (Baker & Gondo 2020)).

Eastern Dan has five level tones (extra-high: a̋, high: á, mid: ā, low: à, extra-low: ȁ; the extra-low floating tone is designated by an apostrophe) and three modulated tones (all falling), only one of which is relatively frequent, high-falling: â. Tones bear a great functional load, fulfilling both lexical and grammatical functions (Bearth & Zemp 1967; Vydrin 2016).5

2.3. Basic morphosyntactic information (relevant to the present paper)

The basic word order in a simple verbal sentence is (S) Aux (DO) V (X), where S is the subject, Aux stands for auxiliaries indexed for the person and number of the subject and expressing TAM and polarity meanings (in the Mandeist tradition these auxiliaries are usually referred to as “predicative markers”), DO is the direct object, V is the verbal predicate, and X is an indirect/oblique object or adjunct. Dan is a null-subject language (the explicit presence of a subject NP is not obligatory, the subject being indexed in the Aux). The presence of a DO makes a verb transitive; if the DO position is void, the verb is intransitive. X can be represented by a postpositional phrase (NP + postposition), an adverb or an NP headed by a declinable noun (see below).

Non-verbal sentences of different types are formed with the copulas ɓɯ̰̏, ɓā, ɗɛ̰̀, ɗɤ́.6 Existential, conjoint and negative imperfective series of auxiliaries (see Table 1) can also serve as copulas in non-verbal sentences and can therefore be regarded as “bifunctional auxiliaries” (Vydrin 2020a: 79).

Series of verbal auxiliaries (predicative markers).

| Singular | Plural | Dual | Plural | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | 1 | 2 | 3 | Logophoric | 1 exclusive | inclusive | inclusive | 2 | 3 | Logophoric |

| Series, glosses | ||||||||||

| Existential EXI | ā | ī/ɯ̄ | Ø/yɤ̏ | ɤ̄ | yī | kō | kwā | kā | wȍ | wō |

| Conjoint JNT | á | í/ɯ́ | Ø/ɤ́ | ɤ́ | yí | kó | kwá | ká | wó | wó |

| Perfect PRF | ɓá̰ | ɓá | yà/yȁ | yá | yá | kó | kwá | ká | wà/wȁ | wá |

| Prospective PROS | ɓā̰ā̰ | ɓīī | yɤ̄ɤ̄ | – | yīī | kōō | kwāā | kāā | wōō | – |

| Imperative IMP | – | Ø/ɓɤ̏ | – | – | – | kȍ | kwȁ | kȁ | – | – |

| Subjunctive SBJV | á | í/ɯ́ | Ø/yɤ̏ | ɤ́ | yí | kó | kwá | ká | wȍ | wó |

| Presumptive PRES | ɓā̰ȁ̰ | ɓāȁ | yāȁ | – | yāȁ | kōȍ | kwāȁ | kāȁ | wāȁ | – |

| Negative imperfective NEG.IPFV | ɓá̰á̰ | ɓáá | yáá | – | yáá | kóó | kwáá | káá | wáá | – |

| Negative perfective NEG.PFV | ɓḭ́ḭ́ | ɓíí | yíí | – | yíí | kóó | kwíí | kíí | wíí | – |

| Prohibitive PROH | ɓá̰ | ɓá | yá | – | yá | kó | kwá | ká | wá | – |

A noun can be the head of a noun phrase. It can appear in the positions of subject, direct object, or oblique (introduced by a postposition, i.e., as the dependent component of a postpositional phrase); it can also be the head of an attributive nominal construction.

In the noun phrase, a dependent noun precedes the head noun, while an adjective follows the head noun. A determiner follows the NP. Thus, the basic NP structure is [[NP] N [Adj] Det].

A dependent noun can be connected to the head noun directly (ɗɯ̋ zɔ̋ɗi̋ɤ̋ <tree top> ‘top of a tree’) or by means of a postposition (ɗūɤ̄ɤ̄ ɓȁ gbīŋ̄gā <raffia.palm on caterpillar> ‘raffia palm caterpillar’).7 If the possessor is human, it is connected to a relational noun without a postposition (Gbȁtȍ dʌ̄ <Gbato father> ‘Gbato’s father’), and to a non-relational noun by means of the postposition ɓȁ (Gbȁtȍ ɓȁ kʌ̋ʌ̋ <Gbato on hoe> ‘Gbato’s hoe’). In other words, the postposition ɓȁ serves as a marker of dependency between nouns.8 When a possessive construction with a non-relational head appears in post-verbal position, the connecting postposition ɓȁ is most often replaced by another postposition, gɔ̏.

- (1)

- Wʌ́ʌ̏gā

- money

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- ɗȍ

- go\NEUT

- kʌ̄’

- do\INF

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- gɔ̏

- for

- yʌ̋ʌ̏

- gɯ́.

- in

- ‘There is probably money in his pocket.’

There is a subclass of nouns, so-called declinable nouns. In adjunct function they appear in their oblique case forms without postpositions.9 Six morphological cases can be identified, with a great deal of irregularity in their formation. For more detail, see (Vydrin 2011).10

Adjectives have semi-regular derivative models for plural and intensive meaning based on reduplication, modification of tones, suffixation and transfixation. They can appear in three syntactic functions: a noun modifier in an attributive nominal construction (2), the predicate in a postpositionless construction with a bifunctional auxiliary in copular function (3), the predicate in a postpositional construction (the postposition is ká ‘with’), and with a bifunctional auxiliary in copular function (4).

- (2)

- Glà

- polyarthritis

- kpæ̋æ̋

- dry

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɓȁ.

- on

- ‘He has polyarthritis’ (lit. A dry polyarthritis is on him).

- (3)

- Ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- wȍ

- voice

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- kpæ̋æ̋.

- dry

- ‘He has a strident voice’ (lit.: His voice is dry).

- (4)

- Ɯ̄

- 2SG.EXI

- kpæ̋æ̋

- dry

- ká

- with

- dhɛ̀

- that

- gāɗɯ̋

- stick.insect

- ɗɤ́.

- be

- ‘You are as thin (lit. dry) as a stick insect.’

For a detailed presentation of Eastern Dan adjectives, see (Vydrine 2007; Vydrin 2009; Vydrin 2010a).

Verbs in finite verbal constructions are necessarily preceded by auxiliaries (predicative markers, see Table 1). The 3SG existential, conjoint and subjunctive predicative markers can optionally be omitted, and the same is true of the 2SG imperative predicative marker (I prefer to interpret such cases as involving the use of zero exponents rather than a lack of markers). Predicative markers may merge with adjacent pronouns, conjunctions and determiners.

Apart from the predicative markers, the TAM and polarity meanings are expressed by verbal inflection which may be tonal or segmental. In the neutral aspect construction (Vydrin 2010b; Vydrin 2020b), verbal lexical tones are replaced by the extra-low grammatical tone (5b), cf. the perfect construction, where the verb ɗṵ̄ ‘come’ carries its lexical tone (5a).

- (5)

- a.

- Yà

- 3SG.PRF

- ɗṵ̄

- come

- ŋ̄

- 1SG.NSBJ

- kèŋ̏

- after

- dɛ̀ɛ̀.

- today

- He came to me today.

- b.

- Yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- ɗṵ̏

- come\NEUT

- n̄

- 1SG.NSBJ

- kèŋ̏

- after

- dȅȅ.

- recently

- ‘He has come to me recently.’

This tonal modification is a formal feature distinguishing verbs from adjectives: the adjectives can also appear with the existential series of bifunctional auxiliaries, but keep their lexical tones (3). This formal difference between verbs and adjectives was first described by Piper (1983) for Liberian Dan.

In the conjoint construction (an analogue of the neutral aspect construction used in dependent clauses and after a focalised NP), tonal lowering on the verb takes place; this modification follows a complex pattern which depends on the lexical tone and the segmental structure of the verbal stem, see in detail (Vydrine & Kességbeu 2008: 48–50; Vydrin 2016; Vydrin 2017: 536; Vydrin 2021a: 41–42).

The following means of nominalization are found in Dan-Gwɛɛtaa (see also 3.3, 6.1):

— the gerund, formed with the marker -sɯ̏. The gerund is used as a verbal noun (event nominal) and as a participle (in the attributive construction). A regular form.

— the masdar (event nominal), formed with the suffix -ɗɛ̏. A regular form.

— the result nominal, formed with the suffix -ɗē. An irregular form with limited productivity.

— the supine, formed with the suffix –yȁ̰. A very rare and unproductive form.

— the extra-low grammatical tone on the verbal root marking phrasal nominalization with the retention of the post-verbal arguments.

The first three suffixes (-sɯ̏, -ɗɛ̏, -ɗē)11 can also appear in phrasal nominalization constructions (in this case, they are added to a post-verbal adverbial element or PP). In such constructions, the phrasal nominalization is also marked by the grammatical extra-low tone on the verb. On phrasal nominalization see in more detail sections 3.4 and 7.

3. A survey of the main theses of Baker & Gondo

In this section, I will present the key ideas of Baker & Gondo (2020) in a concise form; critique will be given in the subsequent sections.

3.1. Formal differences between nouns, adjectives and verbs, cross-linguistically and in Dan

Nouns, verbs and adjectives are distinguished in Dan by their distribution. There is a limited amount of conversion between these classes, but this is an idiosyncratic phenomenon, rather than a general property. The authors specially mention a complication: nouns and adjectives are used as predicates preceded by the “particle” ȅ, in the same way as verbs (6/BG14a, b, c). Ȅ can optionally be omitted in all these cases (7/BG15a, b, c).

- (6/BG14)

- a.

- Nʌ́

- child

- ȅ

- 3SG.PRS

- gȁ.

- die

- ‘The child dies.’

- b.

- Műsȍ

- Muso

- ȅ

- 3SG.PRS

- zɔ̄ɔ̄zɔ̏ɔ̏.

- foolish

- ‘Muso is foolish.’

- c.

- Klà

- Kla

- ȅ

- 3SG.PRS

- nʌ́

- child

- ká.

- with

- ‘Kla is a child.’

- (7/BG15)

- a.

- Nʌ́

- child

- gȁ.

- die

- ‘The child dies.’

- b.

- Műsȍ

- Muso

- zɔ̄ɔ̄zɔ̏ɔ̏.

- foolish

- ‘Muso is foolish.’

- c.

- Klà

- Kla

- nʌ́

- child

- ká.

- with

- ‘Kla is a child.’

According to the authors, “the difference between verbs and nouns/adjectives in Dan is concealed in this particular environment because of the confluence of two features of the language, neither of which is remarkable in itself: T remains as a separate word in Dan, and Pred is lexically null (also T can be elided in faster/informal speech)” (Baker & Gondo 2020: 9).

The authors say the following about the cross-linguistic differentiation between the main lexical classes (p. 14):

<…> adjectives (APs) and nouns (NPs) are often used predicatively, <…> but Baker’s claim (with many precedents, including Bowers 1993, and, in a very different framework, Croft 1991) is that this is only possible when the AP or NP gets support from a functional head, called Pred. <…> This difference often shows up (directly or indirectly) in the fact that some sort of copula or predicational particle is needed in predicative adjective and predicate nominal constructions, like be in English (John is happy, John is a hero), but not in verbal constructions (John fell, *John was fall) <…>.

The authors suppose that the fact “that simple verbs combine directly with their core argument, whereas adjectives and nouns can only do so indirectly, with the help of a functional head that may or may not be overt” may explain why nominalized verbs combine directly with their core argument, “whereas nominalized adjectives and nouns can only do so indirectly, with the help of an overt functional head ɓa”.

Another difference between the main parts of speech is mentioned on p. 9:

It is also worth observing that predicate nominal constructions in Dan are different from predicate adjectival constructions in that predicate nominals need to be followed by the postposition ká ‘with’. This difference among the categories is less common/familiar cross-linguistically, but it is systematic in Dan. As such, it is another way of distinguishing nouns from verbs and adjectives in the language.

3.2. Relational and non-relational nouns and two types of possessive constructions

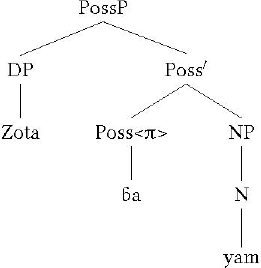

In Dan, relational and non-relational nouns are formally distinguished in possessive constructions: the latter are connected to their possessors by means of the connector ɓa, e.g. (9/BG2b), and the former require no connector (the two nouns are simply juxtaposed), e.g. (8/BG1a). In both cases, the possessor precedes the head noun.

- (8/BG1)

- Zȍta̋

- Zota

- gɔ̀

- head

- ‘Zota’s head’

- (9/BG2)

- Zȍta̋

- Zota

- ɓa̋

- POSS

- ya̋

- yam

- ‘Zota’s yams’

- (10/BG8)

- (11/BG10)

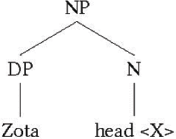

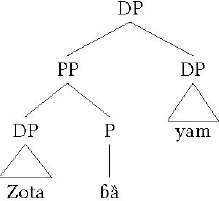

The syntactic structures of these constructions are interpreted by Baker & Gondo as follows: the inalienable possessor is the complement of a noun (10/BG8a), while in a possessive construction with an alienable head noun, the “possessor particle” ɓa is the head, the possessum NP is its complement, and the possessor is the specifier (11/BG10).

3.3. Deverbal and deadjectival nominalization

Verbs are productively nominalized by the morpheme –sɯ. According to Baker and Gondo, the event- and fact-denoting deverbal nouns formed with –sɯ follow the mode of relational nouns and are connected to their possessors without ɓa. A transitive verb can be nominalized retaining both of its core arguments: in this case the theme (i.e., the internal argument) is connected with the verbal noun without ɓa, and the agent (the external argument), with ɓa, see (12/BG33a).

- (12/BG33)

- a.

- Zȍta̋

- Zota

- ɓa̋

- POSS

- Klà

- Kla

- zʌ̄-sɯ̄

- kill-NMLZ

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- já.

- bad

- ‘Zota’s killing Kla is bad.’

Adjectives are regularly nominalized by means of the morpheme -ɗɛ to form names of states, e.g. (BG16a) zɔ̄ɔ̄zɔ̏ɔ̏-ɗɛ ‘foolishness’. Deadjectival nouns follow the model of non-relational nouns, in that they are connected to possessors by means of the connector ɓa, see (BG5a-d).

The authors explain this difference in terms of Baker’s theory of lexical categories, according to which theme arguments are direct arguments of verbs but only indirect arguments of adjectives.

-ɗɛ is also compatible with nominals: it derives abstract nouns (e.g., nʌ́ ‘child’ → nʌ́-ɗɛ́ ‘childhood’, gbɛ̰́ ‘dog’ → gbɛ̰́-ɗɛ́ ‘dog’s behavior’). Baker and Gondo refer to this derivation as “nominalization of nouns” and consider it to be similar to deadjectival nominalization with -ɗɛ, inasmuch as these forms also require the possessive connector ɓa when used as possessum.

Finally, -ɗɛ can derive nouns from verbs, but in this case, according to Baker and Gondo, its role is different: first, the derived form has the meaning of the location of the event (Zȍta̋ gā-ɗɛ̄ ‘place where Zota died’, ɓa̋a̋ kpà-ɗɛ̀ ‘the place where rice is cooked’); second, the theme argument of the derived nominal is not marked with the “possessive particle” ɓa.

Further on, we read (Baker & Gondo 2020: 13): “The affix -sɯ also has uses other than its use in deriving event/fact nouns from verb [sic]. It productively derives adjectives from a root of any category.” This claim is confirmed by the following examples (see 6.1 for my interpretation of the semantics and functions of –sɯ):

- (13/GB24)

- a.

- nʌ́

- child

- dĩ-sɯ

- hunger-ADJ

- ‘hungry child’

- b.

- gbɔ̄

- pot

- pɤ̀-sɯ̀

- fall-ADJ

- ‘fallen pot’

- c.

- mɛ̄

- human

- pűű-sɯ̋

- white-ADJ

- ‘white man’

3.4. Low and high nominalization

According to Baker & Gondo (2020: 16), cross-linguistically, a nominalizing morpheme can combine directly with a lexical head, before the lexical head combines with any of the arguments (or adjunct modifiers) that it would normally appear with. This is a low nominalization. Otherwise, the nominalizing morpheme combines with a verb or adjective after the verb or adjective has already combined with at least some of its arguments or modifiers: this is a high nominalization, or phrasal nominalization.

The low nominalization marker for verbs is –sɯ, and that for adjectives is -ɗɛ. When a deverbal noun forms a possessive construction with the theme of the original verb, it behaves as a relational (inalienable) noun (14/BG3c). A deadjectival noun behaves as a non-relational (alienable) noun and connects to the possessor by means of the possessive marker ɓa (15/BG5d).

- (14/BG3)

- c.

- Műsȍ

- Muso

- gā-sɯ̄

- die-NMLZ

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- yá.

- bad

- ‘Muso’s dying is bad.’

- (15/BG5)

- d.

- Ɓe̋e̋

- shirt

- ɓa̋

- POSS

- kpɛ̋ɛ̋-ɗɛ̋

- dry-NMLZ

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- sʌ̄.

- good

- ‘The dryness of the shirt is good.’

Baker & Gondo (2020: 18) explain this difference on the grounds that a verb takes an internal argument, while an adjective takes an external argument; this difference is projected on the syntax of the nominalized forms.

“Nominalization of nouns” (i.e., derivation of abstract nouns with the suffix -ɗɛ) follows the same pattern as the nominalization of adjectives: “they too have no argument that their nominalization can inherit. As a result, they too behave like nonrelational nouns”.

High nominalization, meanwhile, is possible only on verbs. Baker & Gondo assume that deverbal nominalizations as in (14/BG3c) can be interpreted as reflecting either low nominalization, (Műsȍ) – (gā-sɯ̄), or high nominalization, (Műsȍ gā) – (sɯ̄). Besides, there is a nominalization model where the nominalizer –sɯ comes after a post-verbal constituent (an adverb or a postpositional phrase), as in (16/BG37a, f). This model can be only interpreted as high nominalization.

- (16/BG37)

- a.

- Ɓa̋a̋

- rice

- nū

- give

- nʌ́

- child

- ɗɛ́

- to

- sɯ̏

- NMLZ

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- sʌ̄.

- good

- ‘Giving rice to a child is good.’

- f.

- Mlɛ̰̀ɛ̰̀

- snake

- tà

- go

- va̰̋va̰̋ɗɤ́

- quickly

- sɯ́

- NMLZ

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- sʌ̄.

- good

- ‘The snake’s going along quickly is good.’

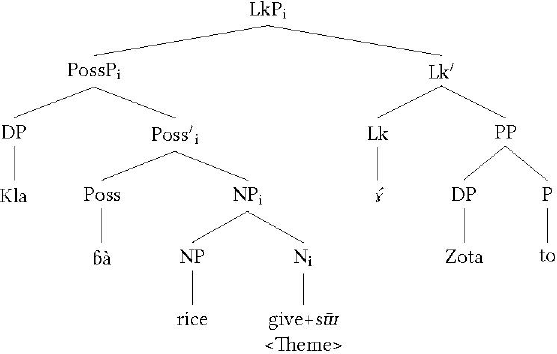

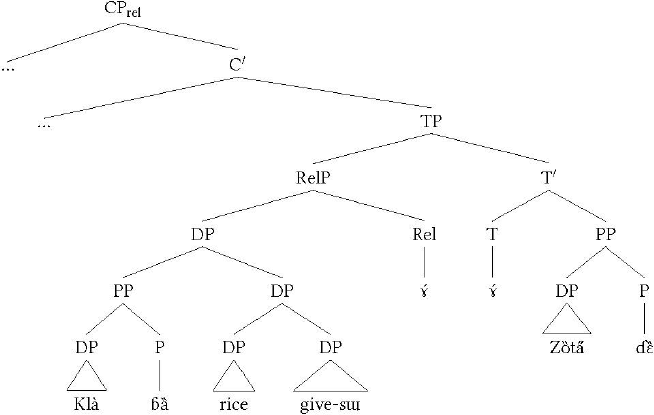

The authors claim that “there is a second version of the nominalizations in (37)12 in which -sɯ does appear affixed directly to the verb root, and the PP, AP or adverb follows -sɯ. The wrinkle is that these postverbal elements are necessarily connected to the nominalized verb by the linking particle ɤ́” (Baker & Gondo 2020: 23), cf. (17/BG39a, d).

- (17/BG39)

- a.

- [Klà

- Kla

- ɓà

- POSS

- ɓa̋a̋

- rice

- nū

- give

- sɯ̏

- NMLZ

- ɤ́

- REL

- Zȍta̋

- Zota

- ɗɛ́]

- to

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- sʌ̄.

- good

- ‘Kla’s giving of rice to Zota is good.’

- d.

- [Mlɛ̰̀ɛ̰̀

- snake

- tà

- go

- sɯ́

- NMLZ

- ɤ́

- REL

- va̰̋va̰̋ɗɤ́]

- quickly

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- sʌ̄.

- good

- ‘The snake’s going along quickly is good.’

The authors claim that in the latter constructions we have low nominalization, and suggest at the same time that “ɤ is probably not a predicative particle”. They represent the syntactic structure of (17/BG39a) as follows.13

- (18/BG42)

Baker & Gondo further note (p. 26) that “the location-denoting nominalizer -ɗɛ (homophonous with the deadjectival nominalizer <…>”, as well as an agentive nominalizer –mɛ can also be markers of high nominalization, in the same way as –sɯ.

At the same time, they show that in those cases where adjectives (in their predicative function) can have adjuncts, the deadjectival nominalizer -ɗɛ can be suffixed only to the adjective, and not the adjunct. This fact confirms the impossibility of the high nominalization for adjectives.

Let us pass now to a critical analysis of the theses of the paper (Baker & Gondo 2020).

4. On the formal differences between the main parts of speech

It would be difficult to disagree with Baker & Gondo that “nouns, verbs and adjectives are distinguished in Dan by their distribution” (see 3.1). However, their discussion of the constructions illustrated by examples (6/BG14) and (7/BG15) is unconvincing. When they say that “no clear difference between verbs, nouns, and adjectives is seen in this environment in Dan” (Baker & Gondo 2020: 9), they do not take into account the tonal morphology of the language. In (6/BG14a), the verb gȁ ‘die’ carries an extra-low tone, although its lexical tone is mid (and it appears elsewhere in their paper with the mid tone, see (BG13a)). This extra-low tone is a marker of the neutral aspect verbal construction (cf. section 2.3). Nouns and adjectives have no tonal marking of this kind: therefore, the purported lack of difference between these parts of speech in this context is only apparent.

As a criterion for differentiation between nouns and adjectives, Baker & Gondo mention that it is impossibile for adjectives (unlike nouns) in predicative function to be followed by the postposition ká. However, this criterion is also unfortunate. The irony is that, unlike other postpositions, ká can follow an adjective in a predicative construction, as was already stated in 2.3, see (4, 19).

- (19)

- a.

- ɓɛ̃̄

- human

- vlã̋ã̋vlã̏ã̏

- slovenly

- ‘a slob’

- b.

- Gbȁtȍ

- Gbato

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- vlã̋ã̋vlã̏ã̏

- slovenly

- ká.

- with

- ‘Gbato is slovenly.’

Vlã̋ã̋vlã̏ã̏ ‘slovenly’, like the great majority of adjectives in Eastern Dan, cannot be used as a noun: as shown in (19a), it cannot express the meaning ‘a slob’ by itself, but the presence of a head noun ɓɛ̃̄ is necessary (in this respect, Eastern Dan differs from many other Mande languages). Therefore, in (19b) it cannot be interpreted as a noun either.14

Baker & Gondo (p. 11) insist that the use of ká can also distinguish nouns from verbs:

As we have seen, the need for ká is a distinctive property of predicate nominals in Dan <…>. Its presence in (20/BG19) thus tends to confirm the inherent nominality of the verb+ sɯ form. Overall, then, there is every reason to see these as straightforward instances of nominalization.

- (20/BG19)

- Műsȍ

- Muso

- ȅ

- 3SG.PRS

- Klà

- Kla

- zʌ̄-sɯ̄

- kill-NMLZ

- ká.

- with

- ‘Musa kills Kla.’

From the translation of example (20/BG19) it can be concluded that in the Gble dialect this construction has an imperfective meaning. In Gwɛɛtaa dialect exactly the same construction is used, but to express resultative meaning:15 it can be intransitive (21) or transitive (22).

- (21)

- Wē

- wine

- ɓā

- ART

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- gīȉ-sɯ̏

- turn.sour-GER

- ká.

- with

- ‘The wine has turned sour.’

- (22)

- Yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- ɤ̄

- REFL.SG

- kwɛ̀ɛ̏

- luggage

- ɗú-sɯ̏

- tie-GER

- ká.

- with

- ‘He has attached his luggage.’

Even if this construction is non-verbal in origin, in synchrony it can be regarded as verbal. The gerund is used here predicatively, in the same way as the adjective in (19b).

The postposition ká in Dan is highly disposed to grammaticalization. In Kla-Dan, ká was grammaticalized as an infinitive marker, and in the next round of grammaticalization the infinitive was integrated into the imperfective verbal construction, i.e. reinterpreted as a finite verb (Makeeva 2017: 633; Makeeva 2018: 129). The evolution of non-finite verbal forms and their reinterpretation as finite verbs is a general trend in Mande languages (Vydrin 2012) and beyond. Even if we decide that the construction represented in (20/BG19, 21, 22) is not fully finite, we should acknowledge that the presence of ká can hardly be regarded as a solid criterion of nominality.

To sum up: I agree with Baker and Gondo that nouns, adjectives and verbs in Dan are formally differentiated; however, none of the criteria suggested by these authors can be considered satisfactory.

5. On the syntactic interpretation of the possessive construction with non-relational nouns

In section 2.1, Baker & Gondo’s understanding of the syntactic structure of possessive constructions was mentioned. I agree with their interpretation of the construction with inalienable nouns (10/BG8a), but not of that with alienable nouns (11/BG10), where the “possessive particle” ɓa is assumed to be the head of the possessive construction.

As was shown in 3.3, the possessive construction with an alienable possessum is just an instance of a nominal construction with a postposition as a marker of dependency between the nouns. With respect to their syntactic structure, such constructions are of the same type as English phrases a house in a wood, a tree by the river, a member of the family. ɓȁ is not the only postposition in Dan that can connect nouns. In (1), the benefactive postposition gɔ̏ appears in the same position, and in (23), postposition pi̋ɤ̋ ‘at (someone’s place)’.

- (23)

- Ā

- 1SG.EXI

- gȍ

- go.away\NEUT

- Yɛ̄ɛ̏

- Ye

- pi̋ɤ

- at

- kwa̋nŋ̏-dhɤ̄.

- compound-LOC

- ‘I am from the Yèè family.’

Therefore, the syntactic structure of the possessive construction with an alienable noun is better represented as in (24) than as in (25/BG10).

- (24)

- (25/BG10)

6. On the deverbal and deadjectival nominalizations

6.1. Nominalization suffixes

According to Baker and Gondo (2020: 11–12), deadjectival nous are derived by means of the suffix -ɗɛ (which can also derive denominal abstract nouns), while deverbal nouns are derived by the suffix –sɯ. They admit that deverbal nouns can also be derived by -ɗɛ, but claim that “the meaning of the derived form is quite different: it does not refer to a state/event/fact/eventuality, but rather to the location at which an event or events of the type named by the verb root takes place”.

In my view, there are three homonymous (or quasi-homonymous) suffixes -ɗɛ and three homonymous suffixes –sɯ in Eastern Dan. In Dan Gwɛɛtaa they all carry the extra-low tone (-ɗɛ̏, -sɯ̏); in the Gble dialect they are toneless, and the tone of the preceding syllable spreads on to the suffix.

The three suffixes -ɗɛ are the following:

common case suffix of the declinable nouns, as in (26), see in more detail (Vydrin 2011);

suffix deriving nouns of quality/state which can be added to adjectival (27) and nominal (28) stems;

suffix of verbal noun (action nominal: I refer to this as the “masdar” simply to distinguish it from other types of verbal noun in Eastern Dan), see (29, 30).

- (26)

- Ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- gblɯ̋-ɗɛ̏

- stomach-CMM

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- we̋-sīʌ̄.

- speak-DUR

- ‘His stomach is rumbling.’

- (27)

- Ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɗó

- go

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɗɛ̏

- place

- gbæ̋æ̋-ɗɛ̏

- broad-ABSTR

- gɯ́.

- in

- ‘He has gone out into the wide world’ (lit. … to the broadness of the place).

- (28)

- Ɯ̄

- 2SG.EXI

- kʌ̄

- RETR

- ɓà̰sɔ̰́ŋ̏-ɗɛ̏

- mason-ABSTR

- kʌ̏

- do-NEUT

- ɓɛ̰́?

- where

- ‘Where did you do the building work?’

It is likely that all three suffixes go back to one and the same noun ɗɛ̏ ‘place’, but in synchrony, it is appropriate to consider the common case suffix as separate one, while the status of the other two (the quality/state and action nominal suffixes) is more debatable: they can be regarded as representing a single transcategorial suffix or two different suffixes (or even three, if we decide that suffixes added to adjectival and nominal stems are distinct).

My first objection to what is said in Baker & Gondo’s article is that although the verbal noun (masdar) derived with -ɗɛ may have the meaning of “location of action” in some contexts (29), elsewhere (depending on the context) it can simply name an action or process (30).

- (29)

- Yȁ

- 3SG.PRF

- kɔ̏ɔ̏

- gourd

- pɛ̋-ɗɛ̏

- split-MSD

- wɔ̏.

- sew

- ‘He has sewn up a split in the gourd’ (lit. … a place of splitting of the gourd).

- (30)

- Zân

- Zan

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- dɔ̏

- know\NEUT

- wʌ́ʌ̏

- money

- ɗōŋ̄-ɗɛ̏

- count-MSD

- ká

- with

- va̰̋a̰̋ɗɤ̄.

- quickly

- ‘Jean can count money quickly’ (lit. ‘Jean knows counting money/the way of counting money…’, rather than *‘Jean knows the place where money is counted quickly’).

To my mind, examples (29) and (30) represent different stages of grammaticalization of the noun ɗɛ̏ ‘place’. There are also intermediate cases, where both interpretations can be accepted, as in (31).

- (31)

- Ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɓǣæ̋-ɗɛ̏

- neck-CMM

- yà

- 3SG.PRF

- tó

- remain

- ɗɛ̰̏ɛ̰̏sɯ̏,

- strict

- yáa

- 3SG.NEG.IPFV

- ɗīaŋ

- talk

- zʌ̄-ɗɛ̏

- kill-MSD

- yɤ̄.

- see

- ‘He has got a sore throat, he cannot speak’ (lit.: ‘… he does not see a place of speaking’, or, in this context, rather ‘he does not see a way of speaking’).

Therefore, the semantic difference between the verbal nouns derived with –sɯ and those derived with -ɗɛ, at least in some contexts, cannot be explained in terms of semantic opposition between event/fact nominals and location nominals.

And the three suffixes –sɯ are as follows:

– the gerund suffix is added to a verbal stem (the low nominalization) or to a post-verbal (adverbial) element (the high nominalization). The low nominalization can express, depending on context, either (a) the meaning of an action/process nominal, or (b) the participial resultative meaning (which can evolve into an adjectival meaning), e.g. (Gwɛɛtaa dialect): yi̋ wɛ̀ŋ̀-sɯ̏ (a) ‘water spilling’, or (b) ‘spilt water’.16 The high nominalization can express only one meaning, that of the action/process nominal. The gerund suffix is regular and predictable, and it can be regarded as inflectional.

– the denominal adjectivization suffix, e.g. (Gwɛɛtaa dialect): fɛ̏ɛ̏ ‘noise’ → fɛ̏ɛ̏sɯ̏ ‘noisy’, ɗɔ̄ŋ̄ ‘shade’ → ɗɔ̄ŋ̄sɯ̏ ‘shady’. Unlike the gerund suffix (which seems to be compatible with any verbal stem), this suffix is of limited productivity (and it is therefore derivational, rather than inflectional): my language assistants refused to derive adjectives from a very large number of nouns, even those which seemed to be semantically compatible with –sɯ̏. On the other hand, we find “unmotivated derivates”, i.e. adjectives with –sɯ̏ for which no original noun is attested, e.g.: sɛ̀ɛ̏sɯ̏ ‘wrinkled’, ki̋ɛ̋ɛ̋sɯ̏ ‘ferocious’. This suffix appears sometimes in intensive forms of adjectives whose basic forms are suffixless, e.g. (Gwɛɛtaa dialect): glɯ̋ɯ̋ ‘bitter’ → Intensive, singular gɯ̋gɯ̋sɯ̏ ‘very bitter’, glɔ̋ɔ̋glɔ̏ɔ̏ ‘blunt’ → Intensive, singular glɔ̄ɔ̋glɔ̄ɔ̋sɯ̏ ‘very blunt’, see in more detail (Vydrine 2007).

– the selectivity suffix can be added to nouns, to adjectives or to personal pronouns belonging to a special “selective” series. A form derived with this suffix is often (but not necessarily) followed by the focalization particle ɗʌ̰̀. The fact that this suffix is different from the adjectivizer –sɯ̏ is proved by the ability of both these suffixes to appear together in a single word form,17 see (32).

Dan Gwɛɛtaa

- (32)

- Sɔ̄

- cloth

- ɗȉȉ-sɯ̏-sɯ̏-ɗṵ̏

- dirt-ADJ-SLA-PL

- zű.

- wash

- ‘Wash just the clothes that are dirty.’

If we return to the examples cited by Baker and Gondo, we can establish that in nʌ́ dĩ-sɯ ‘hungry child’, -sɯ is the denominal adjectivizer; in gbɔ̄ pɤ̀-sɯ̀ ‘fallen pot’ –sɯ is the gerund suffix (pɤ̀ is a verb ‘fall’); and in mɛ̄ pűű-sɯ̋ ‘white man’ -sɯ is the selectivity suffix (pűű is the adjective ‘white’).

In my view, there is no doubt that all three suffixes -sɯ are different, i.e. we have here homonymy of suffixes, rather than polysemy and/or transcategoriality.

6.2. Syntax of deverbal and deadjectival nominals

The central topic of Baker & Gondo’s paper is that the deverbal event and fact nominals formed with –sɯ follow the model of relational nouns and are connected to their possessors without ɓa, while the deadjectival nouns of state derived by means of the morpheme -ɗɛ follow the model of non-relational nouns, i.e. they are connected to possessors by means of the connector ɓa.

However, the rule requiring that “the theme argument of an adjectival nominalization <…> must be marked by the possessive particle ɓa, like the possessors of the nonrelational nouns” is not as strict as is claimed by Baker and Gondo. In my data, I find numerous cases of adjectival nominalization where the theme is not marked with ɓȁ, thus partly disproving the paper’s central claim. Here are some examples.

- (33)

- Yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- tɛ̋ɛ̋dō

- friend

- blɯ̏

- push

- gwʌ̏

- stone

- gɯ́

- in

- yā̰ā̰ɗi̋ɤ̋

- yesterday

- ɗḭ́ḭ̏

- soul

- yāā-ɗɛ̏

- bad-ABSTR

- ɓȁ.

- on

- ‘Yesterday he pushed his friend on the stones maliciously’ (lit.: on the badness of soul).

- (34)

- Yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- ye̋e̋

- laughter

- tȍ

- remain\NEUT

- ɗi̋

- mouth

- gbæ̋æ̋-ɗɛ̏

- broad-ABSTR

- ɓȁ.

- on

- ‘He is giving a loud hearty laugh’ (lit.: he laughs on the broadness of mouth).

- (35)

- Kpȍ

- mongoose

- yȁ

- 3SG.PRF

- tɔ̏

- chicken

- gbɛ́-ɗɛ̏

- numerous-ABSTR

- zʌ̄.

- kill

- ‘A mongoose has killed most of the chickens’ (lit.: the numerousness of the chicken).

- (36)

- Yi̋

- water

- ɤ́

- 3SG.JNT

- sæ̏æ̏

- fresh

- dȅdȅwō,

- truly

- wà

- 3PL.PRF

- wō

- PL.REFL

- kɔ̏

- hand.CMM

- pá’

- touch\3SG.NSBJ

- ká,

- with

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- sæ̏æ̏-ɗɛ̏

- fresh-ABSTR

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- ɓȁ̰

- put\NEUT

- ɓɛ̰̄

- human

- kɔ̏

- hand.CMM

- gɯ́.

- in

- ‘When water is cold, if one touches it with one’s hand, one’s hand feels cold’ (lit.: … its coldness appears in a man’s hand).

I also find numerous examples in my data where ɓȁ is present, as in (37, 38).

- (37)

- Yɛ̏gā

- orifice

- ɤ́

- REL

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɓȁ

- POSS

- gblɛ̰̀ɛ̰̀-ɗɛ̏

- long-ABSTR

- ɤ́

- 3SG.JNT

- ɓɛ̰́tlʌ̏

- metre

- dō.

- one

- ‘A pit one metre deep’ (lit.: A pit which, its length is one metre).

- (38)

- Ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɓȁ

- POSS

- ɗʌ̰́

- child

- ɤ́

- REL

- kwá

- 1PL.INCL.JNT

- we̋-sīʌ̄

- speak-DUR

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɓȁ

- on

- sʌ̏-ɗɛ̏

- good-ABSTR

- ká

- with

- ɗɤ̋

- so.REM

- ɓā…

- ART

- ‘Her child of whose beauty we have thus spoken….’

It is rather improbable that the Gble dialect is different in this respect from what I observe in the Gwɛɛtaa dialect. Even if it seems premature to formulate a strict rule regulating the presence or absence of ɓȁ in possessive constructions with deadjectival nouns, some trends can be identified. The first such trend is that a human possessor requires ɓȁ, as in (20),18 with the exception of two nouns derived from quantifiers, gbɛ̋ɗɛ̏ ‘majority’ (from gbɛ́ ‘many, much’) and kpíȉɗɛ̏ ‘overwhelming majority’ (from kpíȉ ‘big’), as in (39).

- (39)

- Ɗēbʌ̏

- woman

- gbɛ́-ɗɛ̏

- big-ABSTR

- wáá

- 3PL.NEG.IPFV

- tuɤ̏ɤ̏

- livestock

- sūū

- kind

- ɓá

- certain

- dȁ.

- go.up

- ‘Few women have any domestic animal’ (lit.: the majority of women do not rear any kind of livestock).

Another factor may be the pragmatic status of the possessor: it seems that a high pragmatic status of the possessor (as in (37), where the possessor is relativized) may also favour the presence of ɓȁ.

To sum up: contrary to what Baker and Gondo write, possessive constructions with deadjectival nouns may or may not feature the possessive marker ɓȁ, depending on the semantics of the possessor, and probably also its pragmatic status and some other factors.

Let us now consider possessive constructions with deverbal nouns in –sɯ. According to Baker and Gondo:

– if such a deverbal noun is derived from an unaccusative verb, it is connected to its possessor (which corresponds to the internal argument of the verb) without ɓa;

– if it is derived from a transitive verb, the agent of the verb (i.e., its external argument) is connected to the deverbal noun with ɓa, and its object is connected without ɓa, see (12/BG33a) in 2.3.

As for prototypical unergative verbs, the authors claim (p. 21) that such verbs seem to be lacking in Dan, because the meanings in question are expressed by transitive constructions with light verbs: ‘sing’ is ‘song+pick/harvest’, ‘dance’ is ‘dance+do’, ‘sleep’ is ‘sleep+kill’,19 ‘swim’ is ‘water+do’, ‘walk’ is ‘walk+do’ and so on, and the less canonical unergative predicates represented by simple verbs (pè ‘vomit’, wlɤ̀ ‘fly’), when nominalized, are not marked with the possessive ɓa.

Although Baker & Gondo are correct on this point in general, there are some nuances to be taken into account. It is true that “prototypical unergative verbs” are rare in Dan, but still, among the approximately 250 morphologically simple verbs found in the Eastern Dan dictionary (Vydrin 2021b) there are some intransitive verbs which can have agentive subjects. I find examples in my corpus of texts where gerunds of such verbs are connected with their possessors (corresponding to verbal subjects) by means of ɓȁ.

- (40)

- Gbȁtȍ

- Gbato

- ɓȁ

- POSS

- ɗṵ̄-sɯ̏

- come-GER

- yȁ

- 3SG.PRF

- yī

- 1PL.EXCL.NSBJ

- gɯ́-kplȁ.

- embarrass

- ‘Gbato’s arrival has embarrassed us.’

- (41)

- Ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɓȁ

- POSS

- ɗā-sɯ̏

- save-GER

- gɛ̰̏

- foot

- Ø

- 3SG.EXI

- gbȁ̰

- drive.in\NEUT

- Gbȁtȍ

- Gbato

- ɓȁ.

- on

- ‘He owes Gbato his life’ (lit.: The cause of his saving is fixed on Gbato).

The verb ɗā is labile: it can be intransitive (‘save oneself’) or transitive (‘save someone’). If the intransitive meaning is concerned in (41), ɗā is an unergative verb (the saved person is an active actor), and if the transitive meaning is intended, then the saved person is the theme, which is in overt contradiction with Baker & Gondo’s claims.

The gerund of the verb ɗṵ̄ ‘come’ also appears in my data in possessive constructions without ɓȁ, just as in Baker & Gondo’s paper, cf. (BG3a). It turns out that, at least for some speakers (or in some dialects) of Eastern Dan, ɓȁ is acceptable in such context.

On the other hand, converse examples can be found, although rarely: my language assistants accept, in some cases, a gerund of a transitive verb connected with both arguments without ɓȁ, as in (42), although a variant with a possessive connector, wɯ̄-ɗṵ̏ ɓȁ glɛ̏ŋ̏ wɯ́-sɯ̏…, is also accepted.

- (42)

- Wɯ̄-ɗṵ̏

- animal-PL

- glɛ̏ŋ̏

- fence

- wɯ́-sɯ̏

- break-GER

- sűɤ̋

- fear

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- Gɤ̀ɤ̏

- Geu

- gɯ́.

- in

- ‘Geu is afraid that animals may break the fence’ (lit.: A fear of breaking the fence by animals is in Geu).

Without pretending to have conclusive analysis, I would surmise that here again, the presence or absence of ɓȁ may be conditioned by the agentivity of the possessor (the animals mentioned in (42) are agentive, but less so than humans). Accordingly, ɓȁ is not accepted by the same informant in (43), where the possessor is ɗā ‘rain’, while it is obligatory in (44), where the agent is human.

- (43)

- Ɗā

- rain

- (*ɓȁ)

- (POSS)

- bā̰-sɯ̏

- rain-GER

- sűɤ̋

- fear

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- n̄

- 1SG.NSBJ

- gɯ́.

- in

- ‘I’m afraid it will rain’ (lit. A fear of rain’s raining is in me).

- (44)

- Gbȁtȍ

- Gbato

- *(ɓȁ)

- POSS

- Yɔ̏

- Yo

- ɓȁ̰-sɯ̏

- hit-GER

- sűɤ̋

- fear

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- Gɤ̏ɤ̏

- Geu

- gɯ́.

- in

- ‘Geu is afraid that Gbato may beat Yo’ (lit. Fear of Gbato’s beating Yo is in Geu).

7. High nominalization

The ideas of Baker & Gondo on the high nominalization in Eastern Dan can be accepted in their broad outlines. My objection concerns the fact that they have failed to notice the tone lowering on the verbal root as a marker of the high nominalization.

As already mentioned in 2.3, in the Gwɛɛtaa dialect in a construction with high nominalization a verb changes its tone to extra-low if the nominalization suffix –sɯ̏ (in my terminology, the gerund suffix) is attached to a post-verbal constituent, rather than to the verb, cf. (45); the lexical tone of the verb kṵ́ ‘catch’ is high.

- (45)

- dȅ

- self

- kṵ̏

- catch/NMLZ

- wɔ̰́

- matter

- ɗi̋ɤ̋-sɯ̏

- before-GER

- ‘self-control’

It seems that in the Gble dialect a verbal stem takes on a low tone in the same context: in (Baker & Gondo 2020: 22), among the six phrases in example (16/BG37), we observe this tonal lowering in four cases (ɗó → ɗò ‘go’, kʌ̄ → kʌ̀ ‘do, become’, wɪ̋ → wɪ̀ ‘speak’, ta̋ → tà ‘walk’; these verbs appear with their lexical tones in other examples: ɗó (BG3d, BG36b); kʌ̄ (BG34b, BG36c); wɪ̋ (BG24c); ta̋ (BG39d), and the two remaining cases, where no tone lowering is attested, are unclear (I suppose that these exceptions may be due to incorrect tonal notation; audio files containing these phrases would be helpful).

In Standard Eastern Dan, it is not only the high nominalization construction with the suffix –sɯ̏ that is marked with an extra-low grammatical tone on the verbal stem. This tonal morpheme is also attested in high nominalization constructions with the masdar suffix -ɗɛ̏ (46), and in nominalization constructions combined with relativization where the relativized noun is separated from the verb by a post-verbal constituent (an adverb or a postpositional group), see (47).

- (46)

- Ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- ɓȁ

- POSS

- pȉɤ̏gāsòȍ

- bike

- pēdáyɤ̏

- pedal

- yȁ

- 3SG.PRF

- dɔ̄

- put

- bīŋ̄bīŋ̄ɗɤ̄,

- tightly

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- slʌ̏ʌ̏

- turn\NMLZ

- gɯ́-ɗɛ̏

- in-MSD

- yȁ

- 3SG.PRF

- kʌ̄

- do

- gbe̋ȅ.

- difficult

- ‘His bike’s pedals are stiff, it is difficult to pedal’ (slʌ̄ʌ̄ → slʌ̏ʌ̏ ‘turn’).

- (47)

- Ɓā̰

- 1SG.POSS

- yi̋

- water

- tɔ̏

- draw\NMLZ

- ká

- with

- ɓīʌ̋gā

- rope

- yà

- 3SG.PRF

- pɤ̏

- fall

- klɔ̏ŋ̏

- well

- gblɯ̀

- hole

- gɯ́.

- in

- ‘My rope for drawing water has fallen into the well’ (tɔ́ → tɔ̏ ‘draw’).

Therefore, the grammatical extra-low tone on the verbal stem can be regarded as the main morphological marker of high deverbal nominalization, the suffixes (and among these, -sɯ) being supplementary means.

With relation to the high nominalization, I would like to reconsider the analysis of the “second version of nominalization <…> in which -sɯ does appear affixed directly to the verb root, and the PP, AP or adverb follows -sɯ. <…> these postverbal elements are necessarily connected to the nominalized verb by the linking particle ɤ́” (Baker & Gondo 2020: 23), ex. (48/BG39).

- (48/BG39)

- a.

- [Klà

- Kla

- ɓà

- POSS

- ɓa̋a̋

- rice

- nū

- give

- sɯ̏

- NMLZ

- ɤ́

- REL

- Zȍta̋

- Zota

- ɗɛ́]

- to

- è

- 3SG.PRS

- sʌ̄.

- good

- ‘Kla’s giving of rice to Zota is good.’

The syntactic structure of the construction in square brackets is represented by Baker and Gondo as follows (49/BG42).

- (49/BG42)

I disagree with Baker and Gondo with regard to the interpretation of the element ɤ́. In fact, this ɤ́ results from the fusion of two homonymous words, a relativizer ɤ́ and a 3SG verbal auxiliary (predicative marker) of the conjoint series ɤ́ (50a); otherwise, the phrase would simply be incoherent. To demonstrate that this analysis is correct it suffices to pluralize the relativized NP, in which case the 3PL predicative marker appears, and no fusion takes place, as in example (50b) from my data.20

- (50)

- a.

- Gbɛ̰̂

- dog

- ɤ́

- REL.3SG.JNT

- wɔ̏

- lie\JNT

- ɓā

- there

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- gā-sɯ̏

- die-GER

- ká,

- with

- kȁ

- 2PL.IMP

- ȁ

- 3SG.NSBJ

- zȕɤ̏.

- throw

- ‘The dog which is lying there is dead, throw it away.’

- b.

- Ɓɛ̰̄-ɗṵ̏

- human-PL

- ɤ́

- REL

- wó

- 3PL.JNT

- ɓā,

- ART

- wȍ

- 3PL.EXI

- gā-sīʌ̄

- die-DUR

- gbe̋ȅ.

- very

- ‘These people are dying in great numbers’ (lit.: People which they are there, they die very).

Therefore, the syntactic structure of the segment in square brackets in (48/BG39), which I would represent and gloss as in (51a), should be analyzed as follows (51b).

- (51)

- a.

- [Klà

- Kla

- ɓȁ

- POSS

- ɓa̋a̋

- rice

- ɗṵ̄-sɯ̏

- give-GER

- ɤ́

- REL

- ɤ́

- 3SG.JNT

- Zȍta̋

- Zota

- ɗɛ̏,]

- for

- yɤ̏

- 3SG.EXI

- sʌ̏.

- good

- ‘Kla’s giving of rice to Zota is good.’

- (51)

- b.

It is true that my reinterpretation of the syntactic structure of the phrase (48/BG39) does not invalidate Baker & Gondo’s claim that we have here a case of low nominalization, but still, the correct presentation of data seems to me a self-evident requirement for a scholarly article.

8. Conclusions

In their paper, Baker and Gondo (2020: 9–10) claim that nouns, adjectives and verbs in Dan are distinguished only by their syntactic distribution: a verb cannot function as a subject (unlike a noun) or as a modifier (unlike an adjective), and nouns are distinguished from adjectives in their predicative function, where nouns are followed by the postposition ká ‘with’ while adjectives are not.

In reality, besides the syntactic distribution, verbs are also distinguished from adjectives and nouns by their tonal morphology, which invalidates the following claim: “… T and the verb are not brought together in Dan” (Baker & Gondo 2020: 9).

As for ká, it does follow adjectives in their predicative use (even if in this case we can speak of its functional evolution), and therefore it cannot be used as a criterion distinguishing between nouns and adjectives.

Further on, Baker & Gondo (2020) consider the difference between deverbal nouns and deadjectival nouns: “when a transitive or unaccusative verb is nominalized in the Dan language, its theme argument is expressed like the inalienable possessor of a relational noun, whereas when an adjective or noun is nominalized, its theme (subject) argument is expressed like the alienable possessor of a nonrelational noun”. However, a more thorough analysis of the Dan data proves that this difference is not as radical as they think. In fact, the theme argument can combine with a nominalization with the help of the possessive marker ɓa or without it, depending on semantic (position of the possessor in the Animacy Hierarchy) and probably also pragmatic factors.

Baker & Gondo’s analysis of low and high nominalization is correct in many respects; however, they have disregarded the tonal marking of the high nominalization on the verbal stem.

There are numerous other misinterpretations of the Dan data by Baker & Gondo.

One could praise the authors of this paper for their effort to introduce data from Dan into theoretical linguistics. However, this attempt is invalidated, to some extent, by the lack of profound analysis of the language data, an inattention to details, especially those of the tonal morphology, and an utter and blatant ignorance of the preceding tradition of the Dan language studies.

List of glosses and abbreviations

ABSTR – deadjectival nominalization and abstract noun suffix

ADJ – adjectivizer suffix -sɯ̏

ART – definite article ɓā

Aux – auxiliary

CMM – common case suffix -ɗɛ̏

DO – direct object

DUR – durative verbal suffix -sīʌ̄

EXCL – 1st person exclusive plural pronoun/predicative marker

EXI – existential series of bifunctional auxiliaries

FOC – a) focalization particle ɗʌ̰̀ ~ ɗɯ̰̄; b) grammatical high tone on certain focalized nouns

GER – gerundive suffix -sɯ̏

IMP – imperative series of predicative markers

INCL – inclusive 1st person pronoun or predicative marker

INF – infinitive

IPFV – imperfective

JNT – conjoint series of bifunctional auxiliaries; tonal modification on the verbal stem in the conjoint construction

LOC – locative case

MSD – masdar (verbal noun) suffix, -ɗɛ̏

NEG – negative

NEUT – 1) neutral aspect marker (extra-low tone on the verbal stem); 2) Baker & Gondo: suffix –sɯ

NMLZ – nominalizer

NP – noun phrase

NSBJ – non-subject pronominal series

PST – past

PL – plural

POSS – possessive marker ɓȁ

PRF – perfect series of predicative markers

PROH – prohibitive series of predicative markers

PRS – present (Baker & Gondo’s gloss)

Q – general question particle ȅȅ

REL – relativization marker ɤ́

S – subject

SG – singular

SLA – selective marker -sɯ̏

V – verb

X – post-verbal arguments and adjuncts

Notes

- Cited from the home page of Glossa, https://www.glossa-journal.org/. [^]

- Baker and Gondo (p. 1) characterize Dan as “a Niger-Congo language of the Mandean group”. In reality, there is no “Mandean group”: there is simply the Mande language family belonging to the Niger-Congo macrofamily, although its Niger-Congo affiliation is contested by some linguists nowadays. For a recent survey of the genetic classification of African languages, see (Güldemann 2018). [^]

- It is remarkable that the PhD thesis by Gondo is the only publication on Dan mentioned in (Baker & Gondo 2020). Meanwhile, publications dealing with Eastern Dan and predating (Baker & Gondo 2020) are quite numerous, and some of them directly concern the topics dealt with in that paper, see bibliography in (Vydrin 2021a). [^]

- In standard Eastern Dan, mid-close allomorphs [ɩ, ұ, ʋ] of the vowels /e, ɤ, o/ appear under the extra-high tone. In some dialects (including Gble) these allomorphs seem to have undergone phonologization. [^]

- In the Gble dialect the number of tones is the same as in Gwɛɛtaa, but the lexical tones of some words are different. Besides, some auxiliary morphemes are regularly assimilated by the tone of the preceding element (while in Gwɛɛtaa their tones are stable). In Baker and Gondo’s paper some errors in the tonal notation can be observed, but I refrain from pointing these out except where they have an impact on the theoretical aspects of the paper. [^]

- Contrary to Baker & Gondo’s claim (2020: 9) that “<…> Dan does not have an overt copula distinct from T”. [^]

- Contrary to Baker and Gondo’s claim (2020: 25) that “nouns never take PP complements in Dan, as far as we know.” [^]

- In the Gble dialect, ɓa in this function has no tone of its own and is tonally assimilated by the preceding syllable. [^]

- These oblique forms come from fusion with postpositions. [^]

- In all my previous publications, this subclass of nouns was designated as “locative nouns”. However, the term “declinable nouns” is more precise, and I will use it henceforth. Consequently, all the other nouns can be referred to as “inflexible nouns”. [^]

- In the Gble dialect, the first two suffixes seem to have no tone of their own: they acquire the tone of the preceding syllable, which is an argument for their status as clitics (or even bound morphemes). [^]

- My example (16/BG37). [^]

- The authors introduce the label Lk ad hoc, without any explanation. Evidently it stands for “linker”. For criticism of their analysis see Section 7. [^]

- In fact, ká in (19b) is no longer a true postposition; now it is a marker of the predicative function of adjectives (resulting from grammaticalizaton of the postposition ká). [^]

- I do not know if the difference in this construction’s grammatical meaning between Gwɛɛtaa (resultative) and Gble (imperfective) is real, reflecting dialectal variation, or only apparent, due to an imprecise translation of (20/BG19) in Baker & Gondo’s paper. With respect to the topic discussed here it does not matter. [^]

- It is typical of South Mande languages to have a single suffix deriving forms that can function both as verbal nouns (action/event nouns) and as resultative participles, see for example the suffix –lɛ in Beng (Paperno 2014: 32–33), etymologically cognate with the Eastern Dan masdar suffix -ɗɛ. This typological evidence proves that in both action nouns and resultative particles, we have one and the same suffix –sɯ, rather than two homonymous suffixes. [^]

- Theoretically, one could suppose that in (32) we see repetition of the same derivational suffix (as is sometimes attested in the languages of the world). However, each of the suffixes –sɯ̏ has a different function: the first one derives an adjective ɗȉȉ-sɯ̏ ‘dirty’ from the noun ɗȉȉ ‘dirt’, and the second expresses a selective meaning, ‘precisely the dirty ones’ (and not the other clothes). [^]

- Nearly all examples of possessive phrases with deadjectival nouns in (Baker & Gondo 2020) are with human possessors. [^]

- Incidentally, it seems strange that the authors mention, among “the most prototypical unergatives”, the meaning ‘sleep’: the subject of sleeping can hardly be regarded as actively initiating or actively responsible for the action. [^]

- On relativization in Dan, see (Vydrin 2008; Vydrine & Kességbeu 2008: 79–81; Makeeva 2012; Nikitina 2012). [^]

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Nina Sumbatova and Galina Sim who have read the paper and gave valuable comments.

Funding Information

This work is partially supported by a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the program “Investissements d’Avenir” (reference: ANR-10-LABX-0083). It contributes to the IdEx Université de Paris – ANR-18-IDEX-0001.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Baker, Mark C. & Gondo, Bleu Gildas. 2020. Possession and nominalization in Dan: Evidence for a general theory of categories. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 5(1). 1–31. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1018

Bearth, Thomas & Zemp, Hugot. 1967. The phonology of Dan (Santa). Journal of African Languages 6(1). 9–29.

Gondo, Bleu Gildas. 2016. Etude phonologique et morphosyntaxique du dan gblewo. Abidjan: Université Félix Houphouët Boigny PhD dissertation.

Güldemann, Tom. 2018. Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa. In Güldemann, Tom (ed.), The languages and linguistics of Africa (The World of Linguistics 11), 58–444. Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110421668-002

Makeeva, Nadezhda. 2012. Strategii rel’ativizacii v jazyke kla-dan (Стратегии релятивизации в языке кла-дан) [Relativization strategies in Kla-Dan]. In Zheltov, Alexander Ju (ed.), Afrikanskij Sbornik – 2011 (Африканский сборник – 2011) [African Collection – 2011], 231–252. St. Petersburg: Nauka.

Makeeva, Nadezhda. 2017. Kla-dan jazyk (Кла-дан язык) [Kla-Dan]. In Vydrin, Valentin & Mazurova, Yulia & Kibrik, Andrej & Markus, Elena (eds.), Jazyki mira: Jazyki mande (Языки мира: Языки манде) [Languages of the world: Mande languages], 617–679. St. Petersburg: Nestor-Historia.

Makeeva, Nadezhda. 2018. Marques rétrospectives en kla-dan. Mandenkan 60. 123–147. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/mandenkan.1807

Nikitina, Tatiana. 2012. Clause-internal correlatives in Southeastern Mande: A case for the propagation of typological rara. Lingua 122(4). 319–334. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2011.12.001

Paperno, Denis. 2014. Grammatical sketch of Beng. Mandenkan 51. 1–130.

Piper, Klaus. 1983. Das qualifikative System im Gio (Dan). In Vossen, Reiner & Claudi, Ulrike (eds.), Sprache, Geschichte und Kultur in Afrika. Vorträge, gehalten auf dem III. Afrikanistentag, Köln, 14./15. Oktober 1982, 113–124. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2008. Strategii rel’ativizacii v jazykakh mande (na primere dan-gweetaa i bamana) (Стратегии релятивизации в языках манде (на примере дан-гуэта и бамана)) [Strategies of relativization in Mande languages: the cases of Dan-Gwèètaa and Bamana]. In Vydrin, Valentin (ed.), African Collection – 2007, 320–330. St. Petersburg: Nauka.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2009. Morfologija prilagatel’nykh v dan-gweetaa (juzhnyje mande) (Морфология прилагательных в дан-гуэта (южные манде)) [Morphology of adjectives in Dan-Gwèètaa (South Mande)]. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo universiteta (Oriental and African Studies) (2). 120–140.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2010a. Sintaksis i semantika prilagatel’nykh v dan-gweeta (juzhnyje mande) (Синтаксис и семантика прилагательных в дан-гуэта (южные манде)) [Syntaxe and semantics of adjectives in Dan-Gweeta (Southern Mande)]. In Vydrin, Valentin & Dmitrenko, Sergej & Zaika, Natalia & Saj, Sergej & Sumbatova, Nina & Khrakovskij, Victor (eds.), Problemy grammatiki i tipologii: sbornik statej pam’ati V.P.Nedjalkova (1928–2009) (Проблемы грамматики и типологии: Сборник статей памяти В.П.Недялкова (1928–2009)) [Problems of grammar and typology: In memoriam Vladimir Nedjalkov], 77–105. Moscow: Znak.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2010b. “Nejtral’nyj vid” v dan-gweetaa i akcional’nyje klassy (“Нейтральный вид” в дан-гуэта и акциональные классы) [“The neutral aspect” in Dan-Gweetaa and Aktionsarte]. Voprosy Jazykoznanija 5. 63–77.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2011. Déclinaison nominale en dan-gwèètaa (groupe mandé-sud, Côte-d’Ivoire). Faits de langues: Les Cahiers 3. 233–258. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1163/19589514-038-02-900000013

Vydrin, Valentin. 2012. Aspektual’nyje sistemy juzhnykh mande v diakhronicheskoj perspektive (Аспектуальные системы южных манде в диахронической перспективе) [Aspectual systems of Southern Mande languages in diachronic perspective]. In Plungian, Vladimir (ed.), Issledovanija po teorii grammatiki. Vypusk 6: Tipologija aspektual’nykh sistem i kategorij (Исследования по теории грамматики. Выпуск 6: Типология аспектуальных систем и категорий) [Studies in the theory of grammar. Iss. 6: Typology of aspectual systems and categories] (Acta Linguistica Petropolitana. Trudy Instituta lingvisticheskikh issledovanij (ACTA LINGUISTICA PETROPOLITANA. Труды Института лингвистических исследований РАН) [ACTA LINGUISTICA PETROPOLITANA. Transactions of the Institute for Linguistic Studies] 8(2). 566–647. St. Petersburg: Nauka.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2016. Tonal inflection in Mande languages: The cases of Bamana and Dan-Gwɛɛtaa. In Palancar, Enrique L. & Léonard, Jean Léo (eds.), Tone and Inflection: New facts and new perspectives (Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs 296), 83–105. De Gruyter — Mouton.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2017. Dan jazyk (Дан язык) [Dan]. In Vydrin, Valentin & Mazurova, Yulia & Kibrik, Andrej & Markus, Elena (eds.), Jazyki mira: Jazyki mande (Языки мира: Языки манде) [Languages of the world: Mande languages], 469–583. St. Petersburg: Nestor-Historia.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2020a. Non-verbal predication and copulas in three Mande languages. Journal of West African Languages 47(1). 77–105.

Vydrin, Valentin. 2020b. The neutral aspect in Eastern Dan. Language in Africa 1(1). 93–108. DOI: http://doi.org/10.37892/2686-8946-2020-1-1-83-108

Vydrin, Valentin. 2021a. Esquisse de grammaire du dan de l’Est (dialecte de Gouèta). Mandenkan 64. 3–80. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/mandenkan.2406

Vydrin, Valentin. 2021b. Dictionnaire dan de l’Est-français suivi d’un index français-dan. Mandenkan 65. 3–332. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/mandenkan.2541

Vydrine, Valentin. 2007. Les adjectifs en dan-gwèètaa. Mandenkan 43. 77–103.

Vydrine, Valentin & Kességbeu, Mongnan Alphonse. 2008. Dictionnaire Dan-Français (dan de l’Est) avec une esquisse de grammaire du dan de l’Est et un index français-dan. St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoria. http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00715560.