1 Introduction

Recent cross-linguistic work on definiteness has revealed subtle differences across languages with respect to the kinds of contrasts that definiteness-markers may encode. This project has gained steam after Schwarz (2009) developed a fine-grained, theoretically-based catalogue of uses that definite articles could in principle have, building on Hawkins’s (1978) classification.1 In this article, we propose an expansion of Schwarz’s typology to include not only ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ but also ‘super-weak’, propose a methodology for identifying ‘super-weak’ articles, and apply it to Ṭuroyo, an endangered Semitic language.

Schwarz’s (2009) analysis is grounded in the distinction between ‘uniqueness’ and ‘familiarity’ theories of definiteness. The ‘uniqueness’ theory can be traced to Frege. According to Frege (1892 [reprinted 1948]), use of a phrase like the F is sanctioned whenever one and only one object falls under the description F. Hence the moon is a licit definite description, since there is only one moon (for us humans), but ?the Baltic state is not, since there are three. The iota operator gives a way of formally capturing Frege’s idea:

ιx.MOON(x)

denotes the unique individual satisfying a given property if one exists, and otherwise fails to denote. A Montague (1973)-style translation of the into the typed lambda calculus capturing Frege’s idea can thus be written as follows:

| (1) | the ⟿ λF .ιx.F(x) |

This says that the meaning of the definite article is a function that combines with any property to denote the unique individual satisfying that property, as long as such as exists. The lexical entry in (1) represents a UNIQUENESS THEORY of the definite article.

Strawson (1950) pointed out that while there are many tables, and many books, The book is on the table is a perfectly legitimate sentence of English. One way of dealing with this fact is to relativize the definite article to a given situation as follows:

| (2) | the ⟿ λsλF .ιx .Fs(x) |

Here, s is a variable over situations, and Fs(x) means that x is an F in s. The iota expression no longer requires that there be at most one x in the entire world, only relative to the given situation. This kind of analysis is developed by authors including Heim (1990), Cooper (1996), and Elbourne (2013).

A rival theory, often called the FAMILIARITY THEORY, is advocated within a dynamic semantic framework by Heim (1982), among others. According to this view, a definite article serves to pick up a familiar discourse referent, just as anaphoric pronouns do. Definite descriptions are associated with an index, just as pronouns are. Without moving fully into dynamic semantics, this approach can be captured using the following formalism:

| (3) | thei ⟿ λF .ιx .[P(x) ∧ x = vi] |

Here, vi denotes the ith variable in a logical language providing a sequence of variables v0,v1,v2,… corresponding to potential discourse referents; the preceding context provides information about discourse referents that have already been introduced via constraints on these variables. The familiarity theory involves iota but it does not require uniqueness of P; it only requires that there be exactly one ‘P associated with index i’ This helps to explain texts like the following:

| (4) | A glass broke last night. The glass had been very expensive. |

This story does not lead the reader to conclude that there is only one glass, so uniqueness with respect to the property ‘glass’ is not implied here; what is implied is that there is a unique ‘glass denoted by the antecedent of the current description’, roughly put. But can the job of the familiarity component be done by situations? Suppose the glass is evaluated relative to the situation containing the glass introduced in the former sentence; then it could succeed in referring, and uniqueness with respect to the property ‘glass’ would not implied more generally. Heim (1990), Cooper (1996), and Elbourne (2013) argue that the use of situations renders the familiarity theory of definiteness unnecessary. See Coppock (in prep) for further discussion of this issue.

Schwarz (2009; 2013) argues that both the uniqueness theory and the familiarity theory are needed, but for different articles. The marriage between these approaches can also be seen in Schwarz’s lexical entry for the ‘strong’ definite article, which incorporates both discourse-familiarity and situation-sensitivity:

| (5) | thei ⟿ λs .λF .ιx .[Ps(x) ∧ x = vi] |

In certain Germanic varieties such as the Frisian dialect Fering (Ebert 1971), there are two series of definite articles, called ‘weak’ and ‘strong’. The distinction is also seen in standard German, in preposition-article combinations: von dem ‘of/by the’ vs. the contracted vom (von + dem). Here are two environments in which they are in complementary distribution:

- (6)

- Der

- the

- Ampfang

- reception

- wurde

- was

- vom

- by.theweak

- / *von

- / by

- dem

- thestrong

- Burgermeister

- mayor

- eroffnet.

- opened

- ‘The reception was opened by the mayor.’ (Schwarz 2009)

- (7)

- a.

- Hans

- Hans

- hat

- has

- einen

- a

- Schriftsteller

- writer

- und

- and

- einen

- a

- Politiker

- politician

- interviewt.

- interviewed

- ‘Hans interviewed a writer and a politician.’

- b.

- Er

- He

- hat

- has

- *vom

- from.theweak

- / von

- / from

- dem

- thestrong

- Politiker

- politician

- keine

- no

- interessanten

- interesting

- Antworten

- answers

- bekommen.

- gotten

- ‘He didn’t get any interesting answers from the politician.’ (Schwarz 2009)

Schwarz argues that these involve the uniqueness-based lexical entry (2) and the familiarity-based article (5), respectively, based on their distribution in a range of environments. As Schwarz shows, the weak articles are used when uniqueness is presupposed with respect to what Hawkins (1978) calls an ‘immediate situation’ (e.g. the dog), a ‘larger situation’ (e.g. the priest), or a ‘global situation’ (e.g. the moon), and in certain types of bridging anaphora.

Bridging anaphora is a phenomenon in which an anaphor does not have a coreferential linguistic antecedent, but is licensed in view of a predictable relation between its referent and the referent of its antecedent. Schwarz observes that German articles show a split between two different types of bridging anaphora, ‘part-whole bridging’ (e.g. the tower, after a church has been introduced), and ‘product-producer’ bridging (e.g. the author, after a book has been introduced). The weak article is used for part-whole bridging, while the strong article, which also occurs in anaphoric context, is used for product-producer bridging.

In this paper, we investigate the environments that Schwarz uses to distinguish between strong and weak uses, as well as also investigate exclusives and superlative adjectives. These latter two kinds of cases are potentially interesting for two reasons. First, Wespel (2008) shows that exclusives, superlatives, and sentence-internal readings of same behave distinctively in Haitian Creole, so their behavior cannot be assumed to be like that of other expressions in the language. Second, exclusives give rise to anti-uniqueness effects, which Coppock & Beaver (2015) take to show that the English article should be analyzed as ‘super-weak’ rather than ‘weak’, meaning that uniqueness is presupposed but existence is not.

Anti-uniqueness effects are manifest in examples like:

| (8) | Scott is not the only author of Waverley. |

On one prominent reading of this sentence, it implies that there are multiple authors of Waverley. If so, then there is nothing that satisfies the description ‘only author of Waverley’. So the definite description as a whole cannot presuppose existence. Under Coppock & Beaver’s (2015) analysis, English the is fundamentally predicative, and it acquires existential import through the same kinds of type-shifting operations that give existential import to bare nouns in article-less languages like Russian. Combined with a predicate P, the P denotes P, as long as there is no more than one satisfier of P (possibly zero). In the following lambda expression, ∂(|P| ≤ 1) is a formula that evaluates to ‘true’ if the cardinality of P is zero or 1, and ‘undefined’ otherwise, thus implementing the presupposition that P has at most one satisfier:

| (9) | λP .λx . ∂ (|P| ≤ 1) ∧ P(x) |

If Ṭuroyo’s article exhibits anti-uniqueness effects, then according to the same reasoning, such an analysis is applicable to Ṭuroyo as well.

The results of our investigations show that Ṭuroyo’s definite article has a very wide distribution, including anti-uniqueness cases, and beyond the range of English definite articles, into definiteness spreading constructions, where they may be used contrastively or non-contrastively. The only limit to their reach is with superlative adjectives, which appear to compete for the article’s syntactic position. We advocate syntactic explanations for the definiteness spreading uses and the absence of the definite article with fronted superlatives, and we propose that definite articles in Ṭuroyo have an underlyingly super-weak semantics.

Given this claim, a question arises as to why the article has anaphoric uses. We argue that anaphoric uses are actually predicted under a weak or super-weak analysis, and more generally that the typology of definite articles is a cline, where stronger articles carry more specific meanings than weaker articles.

strong article > weak article > super-weak article

As discussed in the final section, this view makes the broader typological prediction that weaker articles should generally have a wider distribution than stronger articles, except in the case of blocking by a competing form.

2 Background on Ṭuroyo

Ṭuroyo is a Neo-Aramaic variety spoken mainly in Southeast Turkey, specifically the Ṭur Abdin region. Ṭuroyo is considered threatened, with an approximated 100,000 speakers worldwide according to Glottolog,2 or 40,000 according to Jastrow (2011). Many Ṭuroyo speakers are in diaspora; our speakers live in Massachusetts and Indiana, USA, respectively.

Although Ṭuroyo was transmitted only orally for many years, there have been attempts to establish an orthography for it. Since the 1880’s, Ṭuroyo has been written using the Syriac alphabet, whose script has three main versions, each with its own system of diacritic vowels: Madnhaya, Serto, and Estrangela. In our case, most written communication with our informants was done in Estrangela. Latin scripts have also been developed for Ṭuroyo, primarily in Sweden. In this article we aim to adhere to the orthography standards developed at the 2015 International Surayt Conference held at the University of Cambridge.3

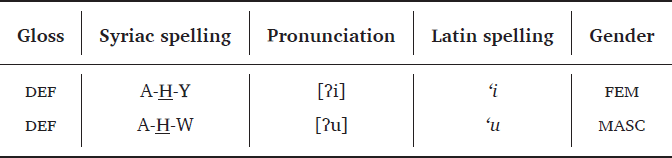

In the Syriac alphabet, regardless of script, the definite article is spelled using three letters: (i) alap, which we write here as ‘A’, (ii) heh ‘H’, and (iii) either yod ‘Y’, for the feminine article, or waw ‘W’, for the masculine.

In the definite article series, the heh is silent (indicated with an underline in the Syriac orthography), and the alap is pronounced as a glottal stop, the yod or waw in this case functioning as a vowel. The result is pronounced either [ʔi] for the feminine definite article and [ʔu] for the masculine. In the Latin spelling, these are written as ‘i and ‘u.

Many languages in the Central Semitic family, including Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic, have definite articles, though their origins differ. The Arabic and Hebrew definite articles are cognate with each other, but the corresponding form in Aramaic became bleached and disappeared; O’Leary (1923: 204–205) summarizes this as follows:

For the definite article Arabic uses the demonstrative -l-… Hebrew uses the prefixed demonstrative ha-… In Aramaic this appears as suffixed -a, the so-called “emphatic” form, but here the determining force is generally lost.

In place of the lost article, some varieties of Aramaic developed a new one.

Doron & Khan (2016) argue that clues about the origins of this new definiteness marker can be gleaned through comparison of two varieties of Neo-Aramaic, namely Barwar (an Assyrian, or Eastern variety) and Ṭuroyo (a Western variety). Ṭuroyo’s definite article is cognate with its own demonstrative (Lipiński 2001: 275), and with an element that serves purely as a demonstrative in Barwar. Contra Pat-El (2009), Doron & Khan (2016) argue persuasively that the historical development of definiteness in Semitic languages follows Greenberg’s demonstrative cycle (Greenberg 1978), in which a demonstrative pronoun grammaticalizes into a definite article when the demonstrative pronoun becomes “bleached of deixis by anaphoric uses” (p. 79). Assuming this to be the case, Ṭuroyo’s definite article is clearly farther along the grammaticalization pathway than Barwar’s, for the reasons that Doron & Khan (2016) point out. The definite article has non-demonstrative uses, as in (10a), and co-occurs with the demonstrative determiner (as usual in Semitic languages), as in (10b):

- (10)

- a.

- rahëṭ-no

- run-1sg

- bëtre

- after

- d-u

- of-DEF

- zcuro

- child

- ‘I chased the boy.’

- b.

- rahëṭ-no

- run-1sg

- bëtre

- after

- d-u

- of-DEF

- zcur-awo

- child-DEM

- ‘I chased that boy.’

Doron & Khan (2016) argue that Ṭuroyo’s article can mark both “pragmatic definiteness” and “semantic definiteness” in Löbner’s (1985) sense. These two notions correspond to familiarity and uniqueness, respectively. To illustrate the ‘pragmatic’ part, they observe that (11b) can follow (11a), and ‘u bayto ‘the house’ in (11b) is interpreted as anaphoric to the house introduced in (11a).

- (11)

- a.

- aḥoni

- brother.POSS.1

- macmarle

- built

- bayto

- house

- ‘My brother built a house.’

- b.

- ‘u

- DEF

- bayto

- house

- qariwo-yo

- near-COP

- l-u

- to-DEF

- bayto

- house

- d-u

- of-DEF

- malko

- king

- ‘The house is near the house of the king.’ (Doron & Khan 2016)

In the same example, ‘u malko ‘the king’ is a non-anaphoric definite. Ṭuroyo uses a definite article in this case, but Barwar does not.4 Doron & Khan (2016) take the ‘king’ example to show that the definite article can mark semantic uniqueness, while the anaphoric case shows that it can mark pragmatic uniqueness.

This article gives a more in-depth look at the distribution of the definite article. Although definiteness-marking has been described to some extent (Jastrow 2011) and discussed from a syntactic perpsective (Doron & Khan 2016), we are not aware of any detailed study of this particular issue. We offer our study as an example of how to assess the status of a definite article in an under-studied language in terms of an enriched typology of definiteness.

3 Strong, weak, super-weak

In this section, we consider each of the environments used by Schwarz (2009) to argue for his analysis of the strong/weak distinction in German, in addition to some others. Given the evidence that Ṭuroyo’s definite article is derived from the anaphoric demonstrative *hu (Doron & Khan 2016: 49), one might expect the definite article to behave like a strong article to some extent, as there tends to be is a connection between strong articles and demonstratives. In German, the strong article can also be used as a demonstrative, and according to Schwarz (2013), strong articles in German, Fering, Akan, Haitian Creole, Mauritian Creole, and Hausa have deictic uses that would be translated into English using a demonstrative (although in Akan, the article no, or something homophonous with it, co-occurs with a separate form saa in deictic uses; cf. Arkoh & Matthewson 2013, Bombi 2018). Cross-linguistic work on definiteness has revealed that languages with definite determiners derived from demonstratives often behave like ‘strong’ articles (Schwarz 2019); for instance, Cho (2016) argues that Korean ku, although it had traditionally been classified as a demonstrative, functions as a strong definite article. But we find that the distribution of the definite article is not limited to those environments in which strong articles are found in German; it extends fully into all weak article environments as well (and beyond).

3.1 Weak-only environments

We begin with ‘immediate situation’ uses, where uniqueness of the relevant predicate is presupposed relative to the immediate context of use. Ṭuroyo allows the definite article in such cases; the following sentence is acceptable in a context where both the speaker and listener know the dog in question (cf. Schwarz 2009, citing Ebert 1971):

- (12)

- ‘u

- DEF

- kalbo

- dog

- carša

- tooth

- kokoyu

- hurt

- ‘The dog has a toothache’

The definite article can also be used to express the uniqueness of ‘larger situations’, where a description is unique relative to a local context (cf. Schwarz 2009, citing Ebert 1971):

- (13)

- lazëm

- must

- ëzi

- go.1sg

- l-u

- to-DEF

- dukano

- store

- ‘I must go to the grocer.’

Doron & Khan’s (2016) ‘king’ example in (11b) can also be classified as a ‘larger situation’ use.

A case involving ‘global uniqueness’—where the descriptive content is unique relative to the whole world—is the following (cf. Schwarz 2009):

- (14)

- Armstrong

- Armstrong

- wa

- COP.PST

- ‘u

- DEF

- barnošo

- person

- qamoyo

- first

- d-faer

- COMP-fly

- l-u

- to-DEF

- sahro

- moon

- ‘Armstrong was the first person to fly to the moon.’

So even if the description is inherently unique, and not mentioned in prior discourse, the definite article is used.

We turn now to part-whole bridging. Bridging is a phenomenon in which the introduction of one entity into the discourse raises other, associated entities to a sufficient level of salience that they can be referred to using an anaphoric expression. The following example illustrates a type of bridging known as ‘part/whole bridging’ (cf. Ebert 1971; Schwarz 2009). In the following example, the first sentence establishes a context, and the second sentence includes a definite description licensed by an indefinite in the first sentence:

- (15)

- a.

- ḥze-lan

- saw-to.us

- cito

- church

- b-falge

- in-middle

- d-I

- of-DEF

- krito.

- village

- ‘We found a church in the middle of the village.’

- b.

- ‘u

- DEF

- burgo

- tower

- ëšmto

- a little bit

- cwiyo

- crooked

- wa

- COP.PST

- ‘The tower was a little crooked.’

Let us suppose that Ṭuroyo’s definite article has the meaning in (2). Then, according to Schwarz (2009), we can explain its appearance in part/whole bridging contexts like the above as follows: The definite description ‘u burgo ‘the tower’ is interpreted relative to the situation consisting of the church introduced in the previous sentence. Since the tower is part of the church, the the tower is guaranteed to exist and in the relevant church-situation, it is the only one. Hence, this data is consistent with a ‘weak’ analysis of the definite article.

To summarize, Ṭuroyo’s definite article is used in all of the environments where Germanic weak articles are found: cases where uniqueness is satisfied in the immediate, larger, or global situation, and in part-whole bridging examples. But as we will see in the following section, it is used in all of the environments where Germanic strong articles are found, as well.

3.2 Strong-only environments

The following example, based on Schwarz (2009), illustrates another type of bridging, known as ‘producer/product bridging’; cf. John bought a book today. The author is French (Schwarz 2009 p. 6).

- (16)

- a.

- Abgar

- Abgar

- zvëlle

- bought

- ktowo

- book

- adyawma.

- today

- ‘Abgar bought a book today.’

- b.

- ‘u

- DEF

- katowo

- author

- franšoyo

- French

- yo.

- COP

- ‘The author is French.’

This use of the definite article is not directly predicted based on the ‘weak’ lexical entry in (2), where the ⟿ λsλF .ιx .Fs(x). As Schwarz (2009: 54) puts it, “when considering wholes and their parts, it is clear that there is a containment relationship between the two, which in turn ensures that whenever we are looking at a situation that contains the whole, it will also contain the part. This is not the case for the relationship between products and their producers. A situation containing a book does not generally contain the book’s author.” In German, the strong article is used for producer/product bridging.

The reasoning is complicated a bit by the fact that the familiarity analysis does not directly predict that these uses should be possible. To account for them, Schwarz (2009) advocates a relational variant of that lexical entry for cases like this, after arguing that the ‘producers’ in producer-product bridging must be described using relational nouns. But this is one respect in which the Ṭuroyo article matches the German strong article, which is analyzed as a familiarity article.

The article in Ṭuroyo also exhibits prototypically anaphoric uses. Example (17) (based on Arkoh & Matthewson 2013) shows an anaphoric use of the definite article.

- (17)

- a.

- zvëlli

- bought.for.me

- furtakala.

- orange.

- ‘I bought an orange today.’

- b.

- ‘i

- DEF

- furtakala

- orange

- ġalabe

- very

- basëmto

- tasty

- wa

- COP.PST

- ‘The orange was very tasty.’

This example is much like Heim’s glass example (4), where an anaphoric use of the glass does not carry a uniqueness implication; there is no implication that there is only one orange here. Anaphoric examples abound; here are two more, based on Schwarz (2009) and Ebert (1971), respectively:

- (18)

- a.

- ‘u

- DEF

- Sargon

- Sargon

- sëmle

- had

- mëqablonuto

- interview

- cam

- with

- katowo

- writer

- w

- and

- politiqayo.

- politician

- ‘Sargon interviewed a writer and a politician.’

- b.

- lo

- NEG

- atile

- get

- funoye

- answers

- ṭowe

- good

- m-u

- from-DEF

- politiqayo

- politician

- ‘He didn’t get any interesting answers from the politician.’

As with the orange example, there is no implication that there is only one politician here. Under Schwarz’s (2009) reasoning, these examples would suggest an analysis of Ṭuroyo’s article as a strong article, as in (5), where thei ⟿ λs .λF .ιx .[Ps(x) ∧ x = vi]. However, we argue below that this data is also consistent with an analysis as a weak article.

3.3 Super-weak environments

Recall from above that Coppock & Beaver (2015) argue for a ‘super-weak’ analysis of the English definite article, one where uniqueness is presupposed but existence is not, based on anti-uniqueness effects in examples like:

| (19) | Scott is not the only author of Waverley. |

where what is implied is that Scott is an author of Waverley, but someone else is as well, so there is no satisfier of the predicate ‘only author of Waverley’.

With this in mind, we set out to determine whether Ṭuroyo’s definite article appears in noun phrases with exclusives that exhibit anti-uniqueness effects. And indeed, we found that it does. We found anti-uniqueness effects not only for nominals in predicate position, as shown in (20), but also for nominals in argument position (object position in particular), as shown in (21).

- (20)

- Muše

- Moushe

- lat-yo

- NEG-COP

- ‘u

- DEF

- katowo

- author

- yëḥidoyo

- only

- d-u

- of-DEF

- ktow-awo

- book-DEM.FEM

- ‘Moushe is not the only author of that book.’

- (21)

- Sona

- Sona

- lo

- NEG

- zmërla

- sing

- wa

- COP.PST

- ‘i

- DEF

- zmirto

- song

- yaḥidayto

- only

- b-u

- at-DEF

- ḥago

- party

- ‘Sona did not sing the only song at the party.’

Example (20) implies that the book has multiple authors, and (21) implies that more than one person sang a song at the party. Regarding (21), for example, our consultant said, “To me, it sounds like there were many songs; Sona was not the only one who sang a song over there.” Hence we do observe anti-uniqueness effects with this type of example. From Coppock & Beaver’s (2015) perspective, what this shows is that a ‘super-weak’ analysis of the sort given in (9) is appropriate: There is no satisfier of the predicate ‘only author of that book’ if there are multiple authors of the book, so existence of a satisfier of that predicate cannot be presupposed by the sentence.

3.4 Proposal for the semantics of the definite article

We have seen that the distribution of Ṭuroyo’s definite article spans across strong, weak, and super-weak environments, just like its English counterpart. Should we then conclude that it is ambiguous between all three of the lexical entries given above, or is its meaning sufficiently general that it applies in all three types of cases? The latter hypothesis certainly has the advantage of parsimony. Can it be maintained?

Beaver & Coppock (2015) propose a way of resolving the tension between uniqueness and familiarity for English definite articles with a single, unified analysis. Under Beaver & Coppock’s (2015) view, familiarity is a special case of uniqueness, in the sense that if familiarity holds, then uniqueness automatically holds as well. To account for Heim’s glass example above, Beaver & Coppock posit that nouns may carry an index, so that the glassi requires uniqueness relative to the property ‘being a glass labelled i’. It turns out that if i is a familiar index, then uniqueness of glassi is guaranteed, no matter how many glasses there are, under the system that they define. Under these assumptions, an article that carries a uniqueness presupposition should always be usable in anaphoric environments—environments where the strong article is licensed in German—unless it is preempted by another form. A simple way of implementing this idea within static semantics would be to borrow the idea from Hanink (2017) that an index-introducing element idx can head the complement to a determiner, as follows:

| (22) |  |

| (23) | idxi ⟿ λx .x = vi |

This idxi can combine via Predicate Modification with glass before it combines with the definite article, yielding λx.[GLASS(x) ∧ x = vi]. Since vi picks out a particular individual, this predicate is guaranteed to be unique, relative to a given assignment.

Given a super-weak semantics for the definite article as in (9), where the ⟿ λP. λx .∂(|P|≤ 1) ∧ P(x), this analysis can accommodate the full range of uses, with the exception of product-producer bridging (which requires a separate treatment even under Schwarz’s theory). Even if we assumed that Ṭuroyo’s definite article were ambiguous between weak and strong, we still would not be able to accommodate the full range of uses; in particular, we would not be able to accomodate the super-weak uses. Hence we propose that Ṭuroyo’s definite article is a super-weak uniqueness article, but nouns may carry an index; hence the anaphoric uses. Cross-linguistic predictions of this view are discussed briefly in the conclusion.

3.5 Additional uses

Before moving on, let us round out the picture of where the definite article occurs by briefly mentioning a number of additional aspects of its distribution. Following Schwarz (2009), we will set these observations aside and not try to over an account for them.

The definite article has proprial uses. Example (18) above illustrated a proprial use of the definite article, modifying a proper name, as in ‘u Sargon ‘the Sargon’. This is one respect in which English and Ṭuroyo differ. As we are not in a position to offer a unified analysis, our conjecture is that this usage involves a separate, subtly different sense of the definite article that is not available for English the. See Muñoz (2019) for a recent treatment of the semantics of proprial articles that might apply here as well.5

As in English, singular definites may denote kinds:

- (24)

- a

- DEF.PL

- karkdone

- rhino

- ḥewore

- white

- mën-kara-ḍe

- became-extinct-3PL

- ‘The white rhino has become extinct.’

- (25)

- ‘i

- DEF

- eqarto

- family

- amrikayto

- American

- ko-quryo

- read

- 16

- 16

- ktowe

- books

- kul

- every

- šato

- year

- ‘The American family reads 16 books a year.’

For generic interpretations, definite plurals can be used:

- (26)

- a

- DEF.PL

- kalbe

- dogs

- lo

- NEG

- kruḥmi

- love

- a

- DEF.PL

- qatune

- cats

- ‘Dogs don’t like cats. ‘

- (27)

- a

- DEF.PL

- iṭaloye

- Italians

- ṭaboxe

- cooks

- ṭawe-ne

- good-COP.3PL

- ‘Italians are good cooks.’

To the extent that kinds constitute a particular type of individual, these uses may somehow be related to the proprial uses, as Schwarz (2009: 66) suggests, but this is an issue that we will not investigate further here.

Unlike in English, we did not find evidence for so-called “weak definite” interpretations (where uniqueness is not implied); for the following example, the consultant we asked reported that Bob and John must be reading the same newspaper.

- (28)

- Bob

- bob

- qrele

- read

- ‘i

- DEF

- gazeta,

- newspaper

- w

- and

- John

- John

- ste

- also

- (qrela

- (read

- ‘i

- DEF

- gazeta)

- newspaper)

- ‘Bob read the newspaper, and John did too.’

But given that weak definite interpretations are highly lexically specific (cf. the newspaper vs. the magazine in English, where only the former gives rise to a weak definite interpretation), we hesitate to conclude that weak definite interpretations are unavailable without a fuller investigation of weak definiteness per se, and we leave this to future research. We take all of these uses to be compatible with a uniqueness-based analysis of the definite article, though we will not spell out any particular treatment of them.

4 Syntactic influences on definiteness-marking

We turn now to two further aspects of definiteness-marking in Turoyo that we take to be driven by syntactic rather than semantic factors: definiteness spreading and obviation of definiteness marking in the presence of fronted superlatives. We discuss both in turn.

4.1 Definiteness spreading

As Doron & Khan (2016) point out, definiteness spreading is found in noun phrases featuring both demonstrative determiners and attributive adjectives:

- (29)

- kroḥam-no

- love-1sg

- ‘i

- DEF

- radayta-yo

- car-DEM

- ‘i

- DEF

- semaqto

- red

- ‘I love that red car.’

It is also found in noun phrases with possessives:

- (30)

- ‘u

- DEF

- kalb-aydi

- dog-POSS

- ‘u

- DEF

- šafiro

- beautiful

- ‘my beautiful dog’

- (31)

- huwe

- PRO

- yo

- COP

- ‘u

- DEF

- zamor-aydi

- artist-POSS

- ‘u

- DEF

- rḥimo

- favorite

- ‘He is my favorite artist.’

The previous examples use the possessive suffix -idi/aydi, which co-occurs with the definite article. There is another possessive suffix, -i, which is typically used with nouns denoting close familial relationships, and this one does not co-occur with the definite article (Jastrow 1993: 52–53). However, modifying adjectives are still marked by the definite determiner in conjunction with this kind of possessive:

- (32)

- aḥon-i

- brother-POSS

- ‘u

- DEF

- nacimu

- small

- ‘my younger brother’

Like the examples with two definiteness markers above, this construction does involve auxiliary marking of the adjective with the definite article.

Doron & Khan (2016) argue that definiteness spreading (at least with demonstratives) imposes a contrastive interpretation. They give the following example:

- (33)

- g-coyašno

- FUT-live

- b-u

- in-DEF

- bayt-ano

- house-DEM

- ‘u

- DEF

- nacimo

- small

- ‘I shall live in this small house.’

We presented informants with a visual scenario in which there was only one car, which was red, and our participants reported that example (29) (with ‘the red car’) would be felicitous in such a scenario, even in the absence of a linguistic antecedent.

Similarly, we found no requirement of contrast in definiteness-spreading examples with possessives. In a context with only one rosebush, the following sentence was judged acceptable by our informants:

- (34)

- hate

- this

- yo

- COP.PRES

- ‘i

- DEF

- wardo

- rose

- d-Ashur

- of-Ashur

- ‘i

- DEF

- šafirto

- beautiful

- ‘This is Ashur’s beautiful rosebush’

Hence, at least for our informants, definiteness spreading is not conditioned by contrast, unlike Doron & Khan (2016) would predict; it seems to be conditioned purely syntactically. Following Danon (2010), we assume that a morphological definiteness feature can be positively specified on both N and A in some languages, and that this fact underlies the phenomenon of definiteness spread in languages like Hebrew. We assume further that Ṭuroyo is one of those languages. In the cases just discussed, the intervention of the demonstrative or possessive phrase between the head noun and the modifier triggers a second realization of definiteness on the modifier, inherited from the dominating DP, as grammatical agreement.

It may seem at this point that almost nothing can limit the distribution of Ṭuroyo’s definite article. But we turn now to superlatives, which will finally put a stop to it.

4.2 Superlatives

To express superlative meaning, one option is to use a positive-form adjective along with an explicit comparison class. In this case, a definite article appears:

- (35)

- ‘u-nacimo

- DEF-small

- d-kulle

- of-all

- ‘the smallest’ (lit. ‘the small of all’) Waltisberg (2016: 61, ex. (106))

Waltisberg (2016: 61) reports that this is the most common strategy for expressing superlativity. Superlative meaning presumably comes about in this construction through a combination of the uniqueness requirement imposed by the definite article and flexibility with respect to the threshold for the positive-form gradable adjective. Finding a threshold that satisfies the uniqueness requirement for the definite article leads to a superlative interpretation, such that the referent holds the gradable property to a greater extent than any other individual in the comparison class. Our consultants did not offer this strategy when translating English sentences containing superlatives, perhaps due to a preference for explicit, morphosyntactic expression of the superlative meaning.

When superlativity is morphosyntactically expressed, a form that is morphologically indistinguishable from a comparative is placed syntactically before the noun (whereas adjectival modifiers are normally placed after the noun). There is no morphological distinction between comparatives and superlatives in Ṭuroyo; the distinction is made purely through syntax. There are three ways of forming comparatives in Ṭuroyo, one native, one borrowed from Arabic, and one borrowed from Kurdish.

The native Ṭuroyo form is a reduction of the positive form; for example, basimto ‘tasty’ becomes basëm ‘tastier/tastiest’.

In the form borrowed from Arabic, a triconsonantal root enters the aCCaC template. Thus basimto becomes absam.

Finally, the comparative ending -tër, borrowed from Kurdish, can be suffixed to the adjectival root, so basimto becomes basim-tër.

All of these comparative forms can also be used in superlatives.

The native Ṭuroyo strategy is shown in (36), with the adjective rabo ‘big’ shortened to rab.

- (36)

- rab

- big.CMPR

- ktowo

- book

- hano

- DEM

- yo

- COP

- ‘This is the biggest book.’

The Kurdish strategy, which was quite commonly used by our informants, is seen in the following examples:

- (37)

- Sargon

- Sargon

- salaq

- climbed

- l-ali-tër

- to-high-CMPR

- ṭuro

- mountain

- b-afrika

- in-Africa

- ‘Sargon climbed the highest mountain in Africa.’

- (38)

- ‘i

- DEF

- momo

- mother

- kosaymo

- bakes

- basim-tër

- tasty-CMPR

- besqwit

- cookies

- b-i

- in-DEF

- brito

- world

- ‘Mom bakes the yummiest cookies in the whole world.’

- (39)

- lat-no

- NEG-1SG

- ‘u

- DEF

- hadomo

- person

- d-i

- of-DEF

- iqartaydi

- family.POSS

- d-këtla

- COMP-has

- nacëm-tër

- small-CMPR

- kacaro

- waist

- ‘I’m not the one in the family with the thinnest waist.’

Notice that the superlative adjective precedes the noun in these examples. Adjectives normally follow the noun. It is only when a -tër-marked adjective is interpreted as a superlative that it appears prenominally. Here is a minimal pair showing that adnominal superlatives are prenominal, while adnominal comparatives are postnominal:

- (40)

- ono

- REDUP

- no

- 1sg

- d-košote

- COMP-drink

- noketz-tër

- less-CMPR

- qahwuto

- coffee

- ‘I am the one who drinks the least coffee.’

- (41)

- ‘i

- DEF

- momo

- mother

- këmmo-le

- says-to.him

- kolazëm

- needs

- d-šote

- to-drink

- qahwuto

- coffee

- noketz-tër

- little-CMPR

- ‘Mom says that he ought to drink less coffee.’

The same pattern holds for all three of the morphological comparative/superlative-marking strategies: with a superlative interpretation, the adjective is placed before the noun, and otherwise it is placed after the noun. These examples illustrate how the marking of superlative meaning is achieved through a combination of morphology and syntax.

There are quite a number of other Semitic varieties that exhibit this superlative fronting phenomenon. Other Aramaic varieties that do so include Syriac and the Jewish dialect of Zakho; see Gutman (2018: 86, 123) for examples. Superlative fronting occurs in Arabic as well; Elghamry (2004) and Hallman (2016) offer theoretical takes on it, which we will discuss further below. Plank (2003: 361–362) discusses the case of Maltese (heavily influenced by Arabic, if not strictly speaking Semitic) within the context of a general discussion of superlatives in Romance languages, pointing out that because the superlative is fronted, one of the definite articles that would otherwise surface is lost.

But fronting of superlatives in this fashion is not ubiquitous among the Semitic languages. Urmi, for example, a dialect of Assyrian (alternatively, ‘Eastern’) Neo-Aramaic—much more closely related to Ṭuroyo than Arabic or Maltese—treats superlatives on a par with other adjectival modifiers, that is, after the noun (Khan 2016: 67) (although Gutman (2018: 7) notes that superlative adjectives can occur prenominally as part of the Construct State construction in Urmi).

Superlative fronting (an instance of what Gutman (2018) calls ‘inverse juxtaposition’) is “clearly an areal phenomenon” according to Gutman (2018: 123, fn. 10), and it may be due to contact with Persian languages, where superlatives, along with ordinals (which are morphologically superlative) are generally placed before the noun, although adjectives canonically appear after the noun (see e.g. Samvelian 2007 for Persian, MacKenzie 1961: 68 for Sorani Kurdish, and Thackston 2006: 28 as well as MacKenzie 1961: 215 for Kurmanji Kurdish).

Gutman (2018: 123, fn. 10) writes, “One reviewer suggested this [superlative fronting] is semantically motivated, as superlatives establish a unique reference similarly to determiners which are typically pre-nominal.” While superlative fronting may be semantically motivated, it cannot be motivated based on uniqueness. The case of Mauritian Creole (Wespel 2008) is instructive as a point of comparison. In Mauritian Creole, a distinct pattern (namely, absence of definiteness-marking) is found for adjectives that “establish a unique reference”, including sèl ‘only’, superlatives (although here there is a split, described further below), and menm ‘same’. If the fronting of superlatives in Ṭuroyo were due to their inherent uniqueness, then we would expect fronting with all uniqueness-implying adjectives, including exclusive adjectives. As we saw above, exclusive ‘only’ in Ṭuroyo is not fronted, nor is it in any of the other geographically-related languages with superlative fronting, as far as we know. If the fronting is semantically motivated in some other way, the relevant factor is highly specific to superlatives.6

We also do not see the split among superlatives that we see in Mauritian Creole. The Mauritian Creole sentence corresponding to (42) lacks a definite article while the one corresponding to (43) has one. Ṭuroyo’s definite article is persistently absent across these contexts, and superlatives are consistently fronted.

- (42)

- ṭav-tër

- good-CMPR

- yalufo

- student

- b-u

- in-DEF

- sedro

- class

- d-malfono

- of-teacher

- Malka

- Malka

- gëd

- will

- otile

- get

- dašno

- prize

- ‘The best student in Mr. Malka’s class will get a reward.’ (Wespel 2008)

- (43)

- b-u

- in-DEF

- sedro

- class

- d-malfono

- of-teacher

- Malka

- Malka

- ṭav-tër

- good-CMPR

- yalufo

- student

- gëd

- will

- otile

- get

- dašno

- prize

- ‘In Mr. Malka’s class, the best pupil will get a reward. (Wespel 2008)

Superlative fronting in Ṭuroyo therefore does not reflect the distinction that governs definiteness-marking on superlatives in Mauritian Creole.

Nor is the fronting of superlatives, and concomittant absence of the definite article, tied to whether they have an ‘absolute reading’ or a ‘relative reading’ (Szabolcsi 1986; Heim 1999). The following example illustrates a relative reading:

- (44)

- me-bayne

- from-among

- d-u

- of-DEF

- Moushe

- Moushe

- wa

- and

- ‘u

- DEF

- Sargon

- Sargon

- wa

- and

- ‘i

- DEF

- Atour

- Atour

- ‘u

- DEF

- Sargon

- Sargon

- salak

- climbed

- l-ali-tër

- to-high-CMPR

- ṭuro

- mountain

- ‘Among Moushe, Sargon, and Atour, Sargon climbed the highest mountain.’ (Wespel 2008)

(We consider this a relative reading because the comparison class, made explicit with the among phrase, is a set of mountain-climbers, rather than mountains.) One might expect the definite article to be absent only with relative readings, as superlatives are semantically indefinite on such readings (Szabolcsi 1986).

Hallman (2016) offers another somewhat semantically-based theory of superlative fronting in Syrian Arabic in terms of Heim’s (1999) analysis of superlatives. As he points out, the syntactic behavior of superlatives in Syrian Arabic matches Heim’s (1999) posited Logical Forms (LFs), in which superlatives undergo a raising operation within the local noun phrase. He posits that Heim’s LF movement takes place overtly in Syrian Arabic. While this view is attractive, it cannot be maintained for the present case, at least not in a totally unconstrained form: If superlatives always surfaced in their LF position, then superlatives should surface far from their local noun phrase on relative readings too, assuming Heim’s (1999) scope theory of relative superlatives. On relative readings, superlatives undergo a movement operation that lands them in proximity to the focused consituent, far away from the modified noun. As we have just seen, with example (44), superlatives do not move so far away from the noun they modify on relative readings. Thus the surface position of superlatives does not always reflect their LF position.

So, while we cannot definitively rule out the possibility that the fronting of superlatives is semantically motivated, we can safely conclude that it is not based on their inherent uniqueness, nor is it due to a reliable correspondence between surface position and position at LF. There may be no more parsimonious generalization than just that it is superlatives that are fronted.

It is only superlatives that front, and more importantly, it is only with superlatives that the definite article is absent. If the definite article were systematically absent with semantically unique descriptions, then the absence of the definite article with superlatives might be taken as an indication regarding the meaning of the definite article. But given that the definite article is compatible with semantically unique descriptions so long as there is no fronted modifier, we find it rather more likely that the absence of the determiner with superlatives is due to syntactic circumstances, namely preemption by the superlative. It appears that the fronting of the superlative somehow displaces the definite article, leaving no room for it.

As mentioned above, Arabic exhibits the same fronting phenomenon with superlatives. Here is a pair of examples from Elghamry (2004: p. 900, ex. (2b) and (3e)), with a positive and superlative adjective, respectively:

- (45)

- a.

- al-kaatib-u

- DEF-writer.3M.SG-NOM

- l-gayyid-u

- DEF-good.3M.SG-NOM

- HaDar-a

- came.3M.SG

- ‘The good (male) writer came.’

- b.

- Aagwad-u

- good.SPRL-NOM

- kaatib-i-n

- writer.3M.SG-GEN-INDEF

- HaDar-a

- came.3M.SG

- ‘The best (male) writer came.’

Elghamry (2004) points out that superlatives generally pattern with quantifiers like ‘all’ with respect to morphology and word order, and unlike demonstratives and typical adjectives. They do not exhibit agreement in features like number and gender, they combine with a noun that surfaces in genitive case, and they can precede construct state constructions.

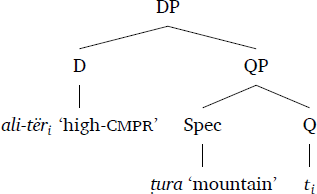

To account for superlative fronting in Arabic, then, Elghamry (2004) argues that superlatives are not of category A, but rather head a nominal projection. Like ‘all’, superlatives head a QP (Quantifier Phrase) projection under DP, and undergo movement to the head of the DP projection. The associated nominal, which surfaces in genitive case, occupies the specifier of this phrase. A parallel analysis in Turoyo would yield the structure in (46) for ‘(the) highest mountain’:

- (46)

Given that superlative fronting is an areal phenomenon, it is reasonable to expect that similar underlying structures would be involved throughout the Sprachbund. As we have seen, superlatives do not inflect for number and gender, even though ordinary adjectives do. As Elghamry (2004) argues for Arabic, this fact lends a bit of support to the view that superlatives are not adjectival, and rather some other category such as Q. The other evidence given for the analysis Arabic cannot be ported to Ṭuroyo, unfortunately: Ṭuroyo nouns do not inflect for case, so we cannot use evidence from case-marking, and there is no clear evidence for a construct state construction in Ṭuroyo. But as far as we can see, Elghamry’s (2004) analysis of superlative fronting in Arabic can be extended to Ṭuroyo. If this analysis is correct, then the absence of the definite article with superlatives is due to the fact that the superlative is occupying its syntactic position, and not because of an obstacle presented by its semantics.

Abbreviations

1/2/3 = first/second/third person, PL = plural, M (ASC) = masculine, F (EM) = feminine, CMPR = comparative, SPRL = superlative, PL = plural, REDUP = reduplication, DEF = definite, INDEF = indefinite, POSS = possessive, DEM = demonstrative, COP = copula, PRES = present, FUT = future, PST = past, COMP = complementizer, NOM = nominative, GEN = genitive, NEG = negative/not

Notes

- In addition to entries in this volume, see Wespel 2008 and Deprez (2016) on Mauritian Creole, Ortmann 2014 on Upper Silesian and Upper Sorbian, Jenks (2015) on Mandarian and Thai, Arkoh and Matthewson 2013 and Bombi 2018 on Akan, Barlew (2014) on Bulu, Maldonado et al. 2018 on Yucatec Maya, and individual contributions to Aguilar-Guevara et al. 2019 on Cuevas Mixtec, Lithuanian, American Sign Language, Yokot’an Maya, among others. [^]

- See https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/turo1239. [^]

- From https://www.omniglot.com/writing/turoyo.htm, accessed December 15, 2019. [^]

- We replicated this data point for Ṭuroyo; both Ṭuroyo speakers we consulted produced the same pattern of definiteness marking when asked to translate the English sentence, My brother built a house. The house is near the house of the king. [^]

- According to Laura Kalin (p.c.), this usage may be mediated by social factors: “[M]y consultants use the definite article before names, but only when the person they are naming is someone very familiar to them or is in their close community. For example, they’ll use the definite article before the name of a friend who attends their church, but not before the name of someone who they know through their children’s (public) school.” We do not have any data bearing directly on this observation, but include it here as a hypothesis as to how to capture the variation in proprial article usage. [^]

- We are aware of one non-superlative adjective that follows the superlative pattern, namely cayni ‘same’ (thanks to a reviewer for pointing out this example):

Hence uniqueness appears to be a necessary, though not sufficient condition for fronting. [^]

- (i)

- ann

- DEF.PL

- armënoye

- Armenians

- ḥzalle

- saw

- cayni

- same

- tacadda

- persecution

- ‘The Armenians experienced the same persecution (as the Syriac people)’

- (Jastrow & Talay 2019: 168)

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to George Stifo and Professor Abdul Saadi for their translations and judgments. We are also very grateful to the organizers of Sorting out definiteness, Carla Bombi and Radek Šimik, for giving us the opportunity to develop this work and for shepherding it to publication. We are also indebted to the conscientious and careful reviewers whose feedback greatly improved this paper.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Aguilar-Guevara, Anna & Pozas-Loyo, Julia & Maldonado, Violeta Vázquez Rojas (eds.). 2019. Definiteness across languages (Studies in Diversity Linguistics). Language Science Press.

Arkoh, Ruby & Matthewson, Lisa. 2013. A familiar definite article in Akan. Lingua 123. 1–30. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2012.09.012

Barlew, Jefferson. 2014. Salience, uniqueness, and the definite determiner-tè in bulu. In Snider, Todd & D’Antonio, Sarah & Weigand, Mia (eds.), Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 24, 619–639. CLC Publications. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v24i0.2992

Beaver, David & Coppock, Elizabeth. 2015. Novelty and familiarity for free. In Proceedings of the 2015 Amsterdam Colloquium, 50–59. University of Amsterdam.

Bombi, Carla. 2018. Definiteness in Akan: Familiarity and uniqueness revisited. Proceedings of SALT 28. 141–160. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v28i0.4406

Cho, Jacee. 2016. The acquisition of different types of definite noun phrases in L2-English. International Journal of Bilingualism 21(3). 367–382. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916629577

Cooper, Robin. 1996. The role of situations in generalized quantifiers. In Lappin, Shalom (ed.), The handbook of contemporary semantic theory. Blackwell.

Coppock, Elizabeth. in prep. Familiarity vs. uniqueness: Can they be told apart? In Altshuler, Daniel (ed.), Linguistics meets philosophy. Cambridge University Press.

Coppock, Elizabeth & Beaver, David. 2015. Definiteness and determinacy. Linguistics and Philosophy 38(5). 377–435. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-015-9178-8

Danon, Gabi. 2010. The definiteness feature at the syntax-semantics interface. In Kibort, Anna & Corbett, Greville (eds.), Features: Perspectives on a key notion in linguistics, 144–165. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deprez, Viviane. 2016. Refining cross-linguistic dimension of definiteness: Variations on ‘la’. Talk presented at the Workshop on the Semantic Contribution of Det and Num, Barcelona, May 27–28.

Doron, Edit & Khan, Geoffrey. 2016. The morphosyntax of definiteness agreement in Neo-Aramaic and Central Semitic. In Audring, Jenny & Masini, Francesca & Sandler, Wendy (eds.), Quo vadis morphology? MMM10 On-line Proceedings, 45–54. DOI: http://doi.org/10.26220/mmm.2723

Ebert, Karen Heide. 1971. Referenz, Sprechsituation und die bestimmten Artikel in einem nordfriesischen Dialekt, vol. 4. Nordfriisk Instituut.

Elbourne, Paul. 2013. Definite descriptions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199660193.001.0001

Elghamry, Khaled. 2004. Definiteness and number ambiguity in the superlative construction in Arabic. Lingua 114. 897–910. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(03)00081-0

Frege, Gottlob. 1892 [reprinted 1948]. Sense and reference. The Philosophical Review 57(3). 209–230. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2181485

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1978. How does a language acquire gender markers? In Greenberg, Joseph H. & Ferguson, Charles A. & Morovcsik, Edith A. (eds.), Word structure, vol. III (Universals of Human Language), Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gutman, Ariel. 2018. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Hallman, Peter. 2016. Superlatives in Syrian Arabic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34. 1281–1328. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9332-1

Hanink, Emily A. 2017. The German definite article and the ‘sameness’ of indices. In Proceedings of the 40th annual Penn Linguistics Conference, vol. 23.

Hawkins, John A. 1978. Definiteness and indefiniteness: A study in reference and grammaticality. London: Croom Helm.

Heim, Irene. 1982. On the semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases: Umass. Amherst dissertation.

Heim, Irene. 1990. E-type pronouns and donkey anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy 13. 137–177. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00630732

Heim, Irene. 1999. Notes on superlatives. Manuscript, MIT.

Jastrow, Otto. 1993. Laut-und Formenlehre des neuaramäischen Dialekts von Mīdin im Ṭūr ‘Abdīn. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

Jastrow, Otto. 2011. Turoyo and Mlahso. In Weninger, Stefan (ed.), The Semitic languages: An international handbook, 697–707. Berlin: Mouton. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110251586.697

Jastrow, Otto & Talay, Shabo. 2019. Der neuaramäische dialekt von midyat (midyoyo). Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz.

Jenks, Peter. 2015. Two kinds of definties in numeral classifier languages. In D’Antonio, Sarah & Moroney, Mary & Little, Carol Rose (eds.), Proceedings of SALT 25, 103–124. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v25i0.3057

Khan, Geoffrey. 2016. A grammar of the Neo-Aramaic dialect of the Assyrian Christians of Urmi. Leiden: Brill. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1163/9789004313934

Lipiński, Edward. 2001. Semitic languages: Outline of a comparative grammar. Leuven: Peeters.

Löbner, Sebastian. 1985. Definites. Journal of Semantics 4. 279–326. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/jos/4.4.279

MacKenzie, David Neil. 1961. Kurdish dialect studies, vol. I. London: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-968X.1961.tb00987.x

Maldonado, Violeta Vázquez-Rojas & Fajardo, Josefina García & Gutiérrez-Bravo, Rodrigo & Loyo, Julia Pozas. 2018. The definite article in Yucatec Maya: The case of le… o’. International Journal of American Linguistics. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/696197

Montague, Richard. 1973. The proper treatment of quantification in ordinary English. In Hintikka, Jaakko & Moravcsik, Julius & Suppes, Patrick (eds.), Approaches to natural language: Proceedings of the 1970 Stanford workshop on grammar and semantics (Synthese Library) 49. 221–242. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Dordrecht. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-2506-5_10

Muñoz, Patrick. 2019. The proprial article and the semantics of names. Semantics and Pragmatics 12(6). 1–32.

O’Leary, De Lacy. 1923. Comparative grammar of the Semitic langages. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315011707

Ortmann, Albert. 2014. Definite article asymmetries and concept types: Semantic and pragmatic uniqueness. In Gamerschlag, Thomas & Gerland, Doris & Osswald, Rainer & Petersen, Wiebke (eds.), Frames and concept types: Applications in linguistics and philosophy, 293–321. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01541-5_13

Pat-El, Na’ama. 2009. The development of the Semitic definite article: a syntactic approach. Journal of Semitic Studies. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgn039

Plank, Frans. 2003. Double articulation. In Plank, Frans (ed.), Noun phrase structure in the languages of Europe, 337–395. Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110197075

Samvelian, Pollet. 2007. A (phrasal) affix analysis of the Persian Ezafe. Journal of Linguistics 43. 605–645. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226707004781

Schwarz, Florian. 2009. Two types of definites in natural language: University of Massachusetts at Amherst dissertation.

Schwarz, Florian. 2013. Two kinds of definites cross-linguistically. Language and Linguistics Compass 7(10). 534–559. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12048

Schwarz, Florian. 2019. Weak vs. strong definite articles: Meaning and form across languages. In Aguilar-Guevara, Ana & Loyo, Julia Pozas & Maldonado, Violeta Vázquez-Rojas (eds.), Definiteness across languages, 1–37. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Strawson, P. F. 1950. On referring. Mind 59(235). 320–344. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.235.320

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1986. Comparative superlatives. In Fukui, Naoki & Rapoport, Tova & Sagey, Elizabeth (eds.), Papers in theoretical linguistics, 245–265. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Thackston, Wheeler M. 2006. Kurmanji kurdish: A reference grammar with selected readings. http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~iranian/Kurmanji.

Waltisberg, Michael. 2016. Syntax des ṭuroyo. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11qdtvj

Wespel, Johannes. 2008. Descriptions and their domains: the patterns of definiteness marking in French-related creoles: University of Stuttgart dissertation. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18419/opus-5708.