1 Introduction

This paper investigates an instance of plural suppletion in the Barguzin dialect of Buryat—an endangered Mongolic language spoken primarily in Russia.1 This suppletion process occurs only in accusative and genitive noun phrases. Here we will see that the restricted distribution of this process, in particular its impossibility in oblique case contexts, is significant because it appears to violate the expectations of much recent work about the internal structure of case, and the cross-linguistic typology of possible suppletion patterns. In this paper, I argue that once we examine the intricacies of this plural suppletion process, we find that its unusual distribution is an epiphenomenon reducible to the interaction of independent factors. Consequently, I argue that this suppletion process does not falsify the predictions of the relevant theories of case structure and suppletion. Rather, it reveals a principled exception to them that sharpens our understanding of them, and of the syntax-morphology relationship more generally.

The term suppletion refers to patterns where a given morpheme is, in certain environments, supplanted by a phonologically unrelated alternative form. In other words, suppletion is simply a more dramatic variety of context-sensitive allomorphy. Many recent works argue that significant cross-linguistic generalizations about syntactically triggered suppletion stem from the way in which the morphological component of the grammar interacts with the functional hierarchies of syntax. One such generalization is stated in (1) below. Bobaljik (2012) on adjectives, Moskal (2018) on in/ex-clusivity, and Smith et al. (2019) on suppletion for case and number in pronouns, for instance, all argue with a basis in Distributed Morphology (Halle & Marantz 1993; Harley & Noyer 1999, a.o.) that this generalization holds for the contexts they respectively examine:

| (1) | Generalization about suppletion and syntactic containment |

| If a suppletion process α is triggered by the presence of a syntactic feature/element β, then α is also triggered in more complex structures that happen to contain β. |

By building theories that derive (1) and related generalizations, works like those cited above make predictions about possible suppletion patterns, and importantly, about impossible ones as well. Among the patterns expected to be impossible is the ‘ABA’ pattern, which in the context of such works, describes suppletion failing to occur in an environment that should contain a feature capable of triggering it. Much of the literature in this vein argues that ABA patterns are basically absent from human language. However, as this paper discusses, this claim is not entirely correct.

The generalization in (1) above describes the behavior of contexts in which there is an implicational containment hierarchy of syntactic features. A growing body of research in morpho-syntax argues that case involves a hierarchy of the relevant type (Blake 1994; Bobaljik 2008; Caha 2009, 2013; Zompì 2017; Smith et al. 2019; Davis To appear, a.o.). Caha (2009), for instance, argues for the hierarchy in (2) below. This hierarchy states, among other relations, that the feature set corresponding to accusative case properly contains nominative case, but is properly contained by the feature set corresponding to genitive case, and so on:

| (2) | Case containment hierarchy |

| (Adapted from Caha 2009: p. 24, ex. 38) | |

| [[[[[[ NOM ] ACC ] GEN ] DAT ] INSTR ] COM ] |

While more complex than the hierarchy that this paper will use, (2) makes an assertion common to other proposed case hierarchies: that oblique cases are highest in the hierarchy, and thus contain the features of all non-oblique cases. In (2), for instance, nominative, accusative, and genitive features are all contained by dative case, the lowest oblique case in the hierarchy. Importantly for this paper, when combined with (1) above, a hierarchy like (2) leads to the prediction in (3):

| (3) | Prediction about suppletion in oblique cases |

| If oblique cases contain accusative / genitive features, any suppletion process triggered by accusative / genitive case should also be triggered in oblique cases. |

Smith et al. (2019) have recently verified a prediction of this nature in their cross-linguistic study of case-sensitive pronominal suppletion. They identify a wide variety of suppletion patterns like those shown in (4) below, which fit precisely what (3) predicts. Specifically, in (4) we see patterns where there is an identifiable pronominal root (bolded) whose form is the same in both accusative and dative contexts, setting aside various minor phonological differences (vowel quality in Latin, stress/accent in Lithuanian, syncope in Russian). Such patterns are termed ‘ABB’ because of the fact that the second and third cells of the paradigm are clearly related to each other, but different from the first cell.

- (4)

- ABB case-sensitive suppletion in Indo-European 1st person singular pronouns

- (Adapted from Smith et al. 2019: p. 1042)

NOM ACC DAT German ich mich mir Greek egō eme emoi Latin ego mē mihi Lithuanian àš manè mán Russian ja menja mnje

Smith et al. (2019) also identify AAA patterns, in which a pronoun’s form is consistent across all cases, as well as ABC patterns, in which a pronoun’s form varies for each case. However, Smith et al. importantly observe the absence of ABA suppletion patterns—ones in which, for instance, a suppletion process triggered in accusative case fails to occur in oblique cases as well.2

As we’ll see next, Barguzin Buryat has an instance of suppletion that occurs in accusative and genitive contexts, but not oblique ones. This phenomenon thus instantiates precisely what the body of research summarized above predicts to be impossible—an ABA pattern. The goal of this paper is to show that this ABA pattern is in fact superficial, since it emerges straightforwardly from the interaction of independent facts about Barguzin Buryat with more general principles of morphology.

1.1 Preview of the plural facts

The basic plural suffix in Barguzin Buryat is -nuud, which I gloss as PL1. This plural marker can appear in nominals of any case—nominative, accusative, genitive, as well as the various obliques. Since the distribution of this plural suffix has no restrictions, I refer to it as the ‘basic’ plural form. In (5) below we see this morpheme previewed in accusative3 and genitive contexts:

- (5)

- a.

- Basic plural -nuud in an accusative context

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgɘi-nʉʉd-iijɘ

- cat-PL1-ACC

- xaranab

- see

- ‘I see cats’

- b.

- Basic plural -nuud in a genitive context

- ɘnɘ

- this

- bagʃa-nuud-ain

- teacher-PL1-GEN

- хɘʃɘɘl-nʉʉd

- lesson-PL1

- χоnin

- interesting

- ‘This teacher’s lessons are interesting’

The basic plural -nuud contrasts with its more restricted optional variant -nuuʃA, which I gloss as PL2 to distinguish it from the basic plural. The capital ‘A’ in -nuuʃA represents a harmonizing low vowel. As I discuss in section 3.1 below, Barguzin Buryat has vowel harmony, and this harmonizing vowel /A/ appears in many morphemes. Speakers describe -nuuʃA as a dialectical or colloquial suffix specific to their regional variety of Buryat. There is no motivation for a phonological explanation for the alternation between -nuud and -nuuʃA (as I discuss in detail in section 4.1 below), nor is there semantic difference between these two plural forms. Therefore I regard -nuuʃA as a contextually-triggered suppletive expression of the plural. Importantly for this paper, while -nuud can appear in any context, the -nuuʃA plural is limited to accusative and genitive contexts. These grammatical uses of -nuuʃA are previewed in (6) below:

- (6)

- a.

- -nuuʃA plural in an accusative context

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgɘi-nʉʉʃɘ

- cat-PL2.ACC

- xaranab

- see

- ‘I see cats’

- b.

- -nuuʃA plural in a genitive context

- miisgɘi-nʉʉʃɘ

- cat-PL2.GEN

- χʉʉl-nʉʉd

- tail-PL1

- uta

- long

- ‘The cat’s tails are long’

The impossibility of -nuuʃA in nominative contexts is demonstrated in (7a) below. This restriction is not surprising for the theories about case and suppletion summarized above. As mentioned previously, what is puzzling for the relevant theories is the further fact that -nuuʃA also cannot occur with oblique cases, as (7b) below shows in a dative context:

- (7)

- a.

- No -nuuʃA plural in nominative contexts

- miisgəi-[nuud/*nuuʃɘ]-∅

- cat-PL1/PL2-NOM

- jɘrɘɘ

- came

- ‘The cats came’

- b.

- No -nuuʃA plural in oblique contexts

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-[nuud/*nuuʃɘ]-tə

- cat-PL1/PL2-DAT

- mʲaxa

- meat

- ʉgɵɵb

- gave

- ‘I gave meat to the cats’

Since -nuuʃA can occur in accusative and genitive contexts, its impossibility in oblique contexts violates the prediction in (3) above. This is the challenge that this paper is concerned with.

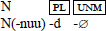

Notice that both the -nuud and -nuuʃA plurals contain a sub-part -nuu. As I show in section 4.2, there is evidence that this is an independent element, since it can be excluded from some plural forms. Therefore I will factor this morpheme out in the final analysis, which I will frame in terms of an alternation between two plural variants -d and -ʃA. For simplicity of exposition, I will speak in terms of -nuud and -nuuʃA for the first part of the paper, and justify their decomposition later on. Setting this detail aside for now, the facts that this paper is concerned with are summarized in (8) below. As the paper progresses, we will deal with a number of additional intricacies about Barguzin Buryat plural marking, but (8) accurately describes the core patterns.

- (8)

- Case and plural marking in Barguzin Buryat

Basic plural (PL1) Suppletive variant (PL2) Nominative N-nuud-∅ * Accusative N-nuud-Aijɘ/iijɘ N-nuuʃA Genitive N-nuud-Ain/iin N-nuuʃA Oblique N-nuud-ABL/COM/DAT/INST… *

1.2 Framework for the analysis

The majority of recent literature on the *ABA generalization and related topics uses one of two frameworks—Distributed Morphology, or Nanosyntax (Starke 2009; Caha 2009, a.o.). Though I will discuss a Nanosyntactic approach to these Buryat facts at the end of the paper, I will focus on an implementation using Distributed Morphology. For this approach, the syntactic derivation builds an abstract hierarchical structure and then passes it on to the PF component of the grammar. This component then assigns morpho-phonological form to the terminal nodes of the syntactic tree depending on the features they bear, by referencing a listed set of Vocabulary Insertion (VI) rules.

In classic Distributed Morphology, the process of assigning morpho-phonological form proceeds terminal-by-terminal, and thus in the basic case one morpheme cannot correspond to more than one terminal node. However, there are indeed situations in human language where a single morpheme seems to express the features of multiple terminals. Such morphemes are sometimes termed portmanteau morphemes, and these will play a central role in this paper.

To achieve portmanteau formation, much literature using Distributed Morphology appeals to a mechanism of fusion, which unites multiple terminal nodes into one before morpho-phonological assignment occurs. As previous research has noted, fusion has the problematic property of requiring the grammar to know which terminal nodes to fuse prior to the application of the relevant VI rule—in other words, a ‘look-ahead problem’ (Chung 2007a, b; Caha 2009, 2018). For this reason, here I will eschew fusion. Instead, I will implement portmanteau formation by spanning, which allows a VI rule to target multiple terminal nodes that form a contiguous sequence (Bye & Svenonius 2012; Merchant 2015; Haugen & Siddiqi 2016; Svenonius 2016, a.o.). This allows a single morpheme to sometimes simultaneously express the features of multiple terminals, as needed. We will see spanning in action in the analysis of section 5, which I preview next.

1.3 Preview of the main proposal

As discussed above, if the generalization about suppletion in containment hierarchies (1) and the case containment hypothesis (2) are both correct, we expect the consequence in (3), repeated in (9):

| (9) | Prediction about suppletion in oblique cases |

| If oblique cases contain accusative / genitive features, any suppletion process triggered by accusative / genitive case should also be triggered in oblique cases. |

If we find a pattern that violates (9), there are two main possibilities. On one hand, (1) or (2) might simply be incorrect. On the other hand, it is possible that (1) and (2) are correct, but that independent factors can sometimes prevent them from interacting in the usual way. I argue that this second type of analysis is accurate for plural suppletion in Barguzin Buryat.

I argue that -nuuʃA is a portmanteau, whose feature specification overlaps with that of oblique morphology. This prevents the two from co-occurring, thus yielding a superficial ABA pattern. The portmanteau-hood of -nuuʃA is revealed by its interaction with accusative / genitive case morphology. Notice that in (5) above, accusative and genitive morphology (here respectively -iijɘ and -ain) affix straightforwardly to the basic plural -nuud. However, in (6) above, the suppletive plural -nuuʃA appears without the typical accusative or genitive marking that we saw in (5). In fact, combining -nuuʃA with typical accusative or genitive morphology is unacceptable, as (10) shows.4

- (10)

- a.

- -nuuʃA blocks usual accusative morphology

- *bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nʉʉʃ-əijə

- cat-PL2-ACC

- xaranab

- see

- ‘I see cats’

- b.

- -nuuʃA blocks usual genitive morphology

- *ʃono-nuuʃ-ain

- wolf-PL2-GEN

- ʃudən

- tooth

- xursa

- sharp

- ‘Wolves teeth are sharp’

I hypothesize that -nuuʃA blocks accusative / genitive case affixes because -nuuʃA is a portmanteau of plural features, and accusative / genitive features. Assuming that a given syntactic feature can only be morphologically expressed once (Bobaljik 2000), since -nuuʃA alone expresses all of these features, independent accusative / genitive marking need not, and cannot, occur with it.

With this hypothesis in mind, notice that according to a case hierarchy like that in (2) above, oblique cases involve a syntactic structure including nominative as well as accusative / genitive features. Correspondingly, in this paper I will posit that oblique suffixes in Barguzin Buryat are portmanteau morphemes that express all of these case features. Importantly, if this is so, then -nuuʃA and oblique morphology overlap in their feature specifications: both must express accusative / genitive features. I argue that for this reason, -nuuʃA and oblique morphology cannot co occur: since each must express features that the other also depends on, they have a complementary distribution.

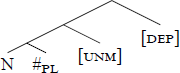

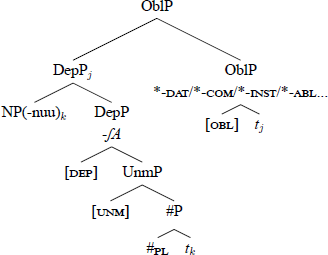

For an initial illustration of this proposal, see (11) and (12) below. In (11), we see the structure for a plural oblique nominal as analyzed under the simplified case hierarchy I will adopt here, which I explain in section 2. In (12), we see a preliminary set of relevant VI rules for Barguzin Buryat. Both (11) and (12) will be slightly modified later on, but these will suffice to make the main point clear. (Note that accusative and genitive cases have been bundled together in (11-12). I justify this decision in section 2 below.)

- (11)

- Structure for a plural oblique nominal (to be revised)

| (12) | Partial set of VI rules for Barguzin Buryat (to be revised) | |

| a. | [#pl] ⟺ -nuud | |

| b. | [#pl NOM ACC] ⟺ -nuuʃA (Optionally supersedes the above) | |

| c. | [NOM] ⟺ ∅ | |

| d. | [NOM ACC] ⟺ Accusative -(ai/ii)jɘ or genitive -(ai/ii)n | |

| e. | [NOM ACC OBL] ⟺ -tA (DAT) / -tAi (COM) / -AAr (INST) / -aan/-χAA (ABL) | |

Several of the VI rules in (12) above describe morphemes that correspond to multiple adjacent terminals—a possibility allowed by the spanning hypothesis, as mentioned above. Importantly, since the rule for -nuuʃA (12b) and oblique morphology (12e) overlap, I argue that both cannot apply in the same nominal domain. This morphological conflict prevents them from co-occurring, and yields the superficial ABA distribution of -nuuʃA. In contrast, notice that the VI rule for the basic plural -nuud (12a) and oblique morphology (12e) do not overlap. Therefore both can be inserted into an oblique nominal structure, as shown once again in (13):

- (13)

- -nuud plural allowed in oblique contexts

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nuud-tə

- cat-PL1-DAT

- mʲaxa

- meat

- ʉgɵɵb

- gave

- ‘I gave meat to the cats’

Though we have identified a reason why -nuuʃA and oblique morphology cannot co-occur, inserting -nuuʃA alone in (11) would successfully express almost every feature in the functional spine of the nominal, aside from [OBL]. In this situation, the rule for oblique morphology (12e) could not apply, and we would expect to end up with an oblique nominal containing -nuuʃA where oblique morphology fails to occur. In reality, such forms are unacceptable (14):

- (14)

- No lone -nuuʃA in an oblique nominal

- *bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nuuʃə

- cat-PL2

- mʲaxa

- meat

- ʉgɵɵb

- gave

- ‘I gave meat to the cats’

Notice that in (13), the combination of -nuud and oblique morphology expresses all features in the functional spine of the nominal, while use of -nuuʃA alone as in (14) leaves an [OBL] feature unexpressed. I argue that for this reason, forms like (13) are always selected over those like (14) because of a blocking effect (Aronoff 1976; Embick & Marantz 2008; Gardani et al. 2019, a.o.). Specifically, I adopt the view of morphological competition in Middleton (2020), who uses spanning to analyze patterns in pronominal syncretism. Middleton argues that the combination of morphemes assigned by VI (within a given syntactic cycle) is the one that most completely expresses the structure in question. This general idea also has precedent in Haugen & Siddiqi (2016). As I discuss in section 5, this theory makes exactly the right predictions about Barguzin Buryat.

In summary, a variety of independent factors prevent -nuuʃA from ever occurring in oblique nominal environments. Thus -nuuʃA has an ABA distribution. However, this pattern is fundamentally an epiphenomenon which does not falsify the theories that ban ABA patterns under normal circumstances. Rather, it reveals a way that ABA can exceptionally arise even in the context of such theories, as the rest of this paper argues in detail.

1.4 Contents of the paper

Next, section 2 provides background on the *ABA generalization and theories of case containment. Section 3 describes the relevant facts about Barguzin Buryat morpho-phonology. Section 4 describes the plural morphology of this language in detail, and shows why the -nuud/-nuuʃA alternation is not phonological. Section 5 provides the main analysis using Distributed Morphology. In section 6 I also discuss a Nanosyntactic analysis. Section 7 contains the concluding remarks.

2 Background on *ABA and case containment

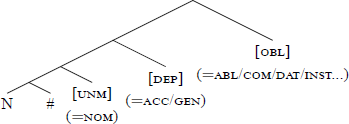

As previewed above, Caha (2009) argues for the case hierarchy in (15a) below. Zompì (2017) and Smith et al. (2019) argue that this hierarchy should be compressed as in (15b), which is organized in terms of the case categories proposed by Marantz (1991). In this simpler hierarchy, oblique cases ([OBL]) contain ‘dependent’ ([DEP]) cases (accusative and ergative), which in turn contain ‘unmarked’ ([UNM]) cases (nominative and absolutive):

| (15) | Two versions of case containment | |

| a. | [[[[[[ NOM ] ACC ] GEN ] DAT ] INSTR ] COM ] | |

| b. | [[[ UNM (=NOM/ABS) ] DEP (=ACC/ERG) ] OBL (=ABL/COM/DAT/INST…) ] | |

While a hierarchy like (15b) will be sufficient for this paper, more must be said about genitive case. In (15a) genitive case is adjacent to (and contains) accusative. Zompì (2017) notes that the nature of genitive morphology is cross-linguistically inconsistent, while Smith et al. (2019) exclude genitive from their study since for them, the possibility of confounding genitive pronouns with distinct possessive forms is problematic. For these reasons these works set aside genitive case, which is thus omitted from (15b).

Since the suppletion process in Barguzin Buryat that I focus on is triggered by both accusative and genitive cases, this paper must make a hypothesis about the position of genitive in the hierarchy. Thus while I will use a hierarchy like (15b), I add to (15b) the qualification that genitive case is contained by oblique cases, as encoded in Caha’s (15a). I reconcile this concept with (15b) by hypothesizing that in Barguzin Buryat, genitive case is in a natural class with accusative in that it is also a ‘dependent’ case. For the purposes of this paper, I will thus assume that dependent case in Barguzin Buryat is realized with either genitive or accusative morphology depending on syntactic context—the former occurring when the relevant NP is embedded in a nominal environment (as in possessive structures), and the latter occurring otherwise. Accusative and genitive case pattern together in Barguzin Buryat not only in that they both allow -nuuʃA suppletion, but also in other aspects of their morpho-phonology, as discussed in the next section. Thus it is reasonable to treat these cases as members of one natural class in this language.5

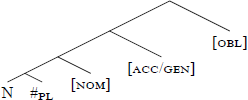

With my assumptions about the case hierarchy now stated, consider the hierarchy in the context of the rest of the functional projection of the nominal, as in (16) below. Here the nominal root N and the # node are dominated by the case structure defined by the hierarchy in (15b) above, to which I have added genitive case under the [DEP] node. (I have also removed the irrelevant cases absolutive and ergative.) The # node sits between N and the case layer, as seen in the linear surface form of Barguzin Buryat nominals. The structure in (16) shows the maximal amount of case nodes, which corresponds to an oblique nominal. A nominal with accusative or genitive marking would lack the [OBL] node, while a nominative nominal would have only the [UNM] node:6

- (16)

- The case hierarchy in context

With this structure in mind, consider the simplified VI rules for Barguzin Buryat plural morphology stated in (17) below. (For the meantime I set aside the spanning analysis previewed above.) In (17a), we see a VI rule for the basic plural -nuud, which can occur in nominals of any case. In (17b) we see a rule which describes the fact that the plural -nuuʃA can be used in accusative / genitive contexts. As previewed in the introduction, use of -nuuʃA rather than -nuud in such cases is optional. Therefore I simply assume that the VI rule for -nuuʃA applies optionally. See section 5 for more concrete discussion about optionality. For the moment, what is important is to notice the distribution that the rules in (17) predict.

| (17) | VI rules for plurality in Barguzin Buryat (updated in section 5) | |

| a. | #pl ⟺ -nuud | |

| b. | #pl ⟺ -nuuʃA / __ ] DEP (=ACC/GEN) (Optionally supersedes the above rule) | |

Importantly, if oblique case structures properly contain accusative / genitive features, then we predict that the rule for -nuuʃA in (17b) should be able to apply not only in accusative / genitive contexts, but in oblique ones as well. As we have seen in the introduction, and will see in more detail in the next section, this prediction is incorrect. Therefore -nuuʃA has an unexpected ABA distribution.

3 The morpho-phonology of Barguzin Buryat

Here I summarize the basics of Barguzin Buryat morpho-phonology. Since this paper is concerned with a morphological phenomenon, familiarity with the language’s other properties is not vital. It is sufficient to state that Buryat is typical of Mongolic and ‘Altaic’ more broadly, in being strictly head-final and having pro-drop, productive scrambling, and suffixing agglutinative morphology. See Tatevosov et al. (To appear) for more information.

3.1 Phonology

Analyzing the morphology of Barguzin Buryat requires familiarity with a few phonological processes, reported here following the description in Staroverov & Zelensky (To appear). This paper adopts the transliteration system used in that work (as well as in Tatevosov et al. To appear), which is an IPA-based representation of the original Cyrillic Buryat orthography. In careful speech the diphthongs transliterated as ⟨ei⟩, ⟨əi⟩, ⟨oi⟩ and ⟨ai⟩ are pronounced as expected following the IPA, but in more natural colloquial speech, the first three diphthongs are simplified to [e:], and the latter to [ɛ:]. This language also has vowel harmony, but the details of this process do not affect the morphological facts under examination here in any significant way. It is only necessary to be aware of the harmonizing low vowel /A/, which is realized as /a/, /ə/, or /o/, depending on the phonological properties of the stem that it affixes to.7

The forms created by agglutinating nominal morphology in this language are frequently affected by its two strategies for avoiding hiatus (vowel-vowel sequences). First, when a heavy vocalic segment (long vowel or diphthong, consisting of more than one mora [=<μ>]) is adjacent to a short vowel, the short vowel deletes, as shown in (18):

- (18)

- Vμ → ∅ / ___Vμμ, Vμμ___

- (Adapted from Staroverov & Zelensky, ex. 20)

Second, when two heavy vocalic segments are adjacent, neither is deleted. Rather, the segment /g/ (phonetically often [ɣ/ʁ]) appears between them, as (19) exemplifies. This is a typologically unusual epenthesis strategy, which is subject to some qualifications as Staroverov (2016) argues, but the level of description in (19) is sufficient for this paper.

- (19)

- ∅ → g / Vμμ___Vμμ

- (Adapted from Staroverov & Zelensky, ex. 21)

- a.

- gun-INST

- buu + AAr → buugaar

- b.

- chicken-ABL

- taxʲaa + AAn → taxʲaagaan

3.2 Case morphology

As is cross-linguistically frequent, nominative case in Barguzin Buryat is null. Oblique cases involve straightforward suffixation of -tA (dative), -tAi (comitative), -AAr (instrumental), or -aan/-χAA (ablative, which has two free variants). We will see these suffixes in many following examples.

In contrast, accusative and genitive marking are more complex, in a way that is phonologically determined. When affixing to a nominal form ending in a long vowel or diphthong, accusative case is -jə (20a-b), while genitive case is -n (20c-d):

- (20)

- Accusative / genitive when following a heavy vocalic segment

- a.

- taxʲaa-jɘ

- chicken-ACC

- b.

- ʒodoo-jɘ

- fir.tree-ACC

- c.

- ɘʒii-n

- mother-GEN

- d.

- noxoi-n

- dog-GEN

However, when suffixing to a nominal form ending in a short vowel or consonant, accusative case marking is -Aijə/-iijə, while genitive case marking is -Ain/-iin, as we see in (21) below. Since these accusative and genitive forms have an initial heavy vocalic segment, when affixing to a nominal form ending in a short vowel the hiatus avoidance process in (18) above deletes that short vowel, as (21c-d) below show.8

- (21)

- Accusative / genitive when following a consonant or short vowel

- a.

- ail-ain/iin

- family-GEN

- b.

- ail-aijɘ/iijɘ

- family-ACC

- c.

- tarxi →

- head

- tarx-ain/iin

- head-GEN

- d.

- tarxi →

- head

- tarx-aijɘ/iijɘ

- head-ACC

It is descriptively correct to hypothesize the following: Fundamentally accusative marking is -jɘ, and genitive marking is -n. Both of these morphemes must affix to a heavy vocalic segment. When the nominal form being affixed to does not end in a heavy vocalic segment, an epenthetic element Ai/ii is inserted to satisfy this need. It is well-known that morphology can be sensitive to phonological context in ways such as this (McCarthy & Prince 1993, 1998; Arregi & Nevins 2012), though alternative analyses of these Buryat facts are conceivable. What I have said here is sufficient for the purposes of this paper, however.

With the relevant morpho-phonological background now laid out, we are prepared to examine in detail the patterns of plural marking that this paper will analyze.

4 The details of Barguzin Buryat plural morphology

As the introduction previewed, the basic plural morpheme in this language is -nuud. This morpheme is not context-sensitive, and thus can occur with any case, as (22) below shows:

- (22)

- -nuud plural is compatible with all cases

- a.

- Nominative

- miisgəi-nuud-∅

- cat-PL1-NOM

- mairana

- meow

- ‘Cats meow’

- b.

- Accusative

- bi

- 1SG

- buuza-nuud-iijə

- dumpling-PL1-ACC

- ədʲəəb

- eat

- ‘I eat dumplings’

- c.

- Genitive

- galuu-nuud-ain

- goose-PL1-GEN

- dali-nuud

- wing-PL1

- jəxə

- big

- ‘Geese’s wings are big.’

- d.

- Oblique

- badma

- Badma

- xarxuur-nuud-aar

- fork-PL1-INST

- ədʲəəlnə

- ate

- ‘Badma ate with forks’

In contrast, while the alternative plural form -nuuʃA can occur in accusative and genitive environments (23-24),9 it cannot occur in nominative ones (25).

- (23)

- -nuuʃA possible in accusative contexts

- a.

- bi

- 1SG

- buuza-nuuʃa

- dumpling-PL2.ACC

- ədʲəəb

- ate

- ‘I ate dumplings’

- b.

- badma

- Badma

- ɘgɘʃɘ-nʉʉʃɘ

- sister-PL2.ACC

- zolgoo

- met

- ‘Badma met sisters’

- (24)

- -nuuʃA possible in genitive contexts

- a.

- əgəʃə-nuuʃə

- sister-PL2.GEN

- nʉxəd

- friend

- χain

- nice

- ‘The sisters’ friends are nice’

- b.

- ʃono-nuuʃa

- wolf-PL2.GEN

- ʃudɘn

- tooth

- xursa

- sharp

- ‘Wolf’s teeth are sharp’

- (25)

- No -nuuʃA in nominative contexts

- a.

- *noxoi-nuuʃa

- dog-PL2

- jɘrɘɘ

- came

- ‘Dogs came’

- b.

- *buuza-nuuʃa

- dumpling-PL2

- amtatai

- delicious

- ‘Dumplings are delicious’

Notice that as (22b/c) above show, typical accusative and genitive marking stack on top of the basic plural. Contrast this with (23) and (24), where we see -nuuʃA, but no accusative or genitive marking: instead, here only -nuuʃA appears. As (26) below shows explicitly, -nuuʃA in fact cannot be combined with typical accusative / genitive suffixes. Attempting such strings results in unacceptability, a fact which will be important for the coming analysis.

A few notes on the forms tested in (26) are necessary. As mentioned previously, for nominal forms that do not end in a heavy vocalic segment, accusative and genitive marking respectively take on the forms -Aijə/-iijə and -Ain/-iin. Thus a noun marked with -nuuʃA, which ends in a short vowel /A/, would be expected to use these case forms. These phonologically-conditioned variants of accusative and genitive case begin with a heavy vocalic segment. Therefore stacking such case markers on top of -nuuʃA should cause the final short vowel of -nuuʃA to be deleted given the hiatus avoidance process illustrated in (18) above, which triggers deletion of a short vowel adjacent to a heavy vocalic segment. This expected phonological manipulation is performed in the examples of (26), which are nevertheless unacceptable.10

- (26)

- -nuuʃA is incompatible with typical accusative / genitive marking

- a.

- *bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nʉʉʃ-iijə/əijə

- cat-PL2-ACC

- xaranab

- see

- ‘I see cats’

- b.

- *bi

- 1SG

- ʃono-nuuʃ-iijə

- wolf-PL2-ACC

- xaranab

- see

- ‘I see wolves’

- c.

- *miisgəi-nʉʉʃ-əin/iin

- cat-PL2-GEN

- χʉʉl-nʉʉd

- tail-PL1

- uta

- long

- ‘Cats tails are long’

- d.

- *ʃono-nuuʃ-ain

- wolf-PL2-GEN

- ʃudən

- tooth

- xursa

- sharp

- ‘Wolves teeth are sharp’

Finally, as previewed in the introduction, -nuuʃA is also distinct from the basic plural marker in that it cannot occur in oblique contexts. This is shown exhaustively in (27) below. Here we see that the basic plural can occur with all oblique cases, and that -nuuʃA is never permitted in oblique case environments, regardless of whether a hiatus avoidance process would have applied or not. Importantly, in (27) we also see that whether oblique morphology is preserved or omitted in the presence of -nuuʃA, the resulting form is unacceptable. Since we’ve seen that -nuuʃA is acceptable in accusative / genitive contexts provided that typical accusative / genitive marking is omitted (23–24 versus 26), we might have expected -nuuʃA to be acceptable in oblique contexts provided that typical oblique marking is absent. However, we see in (27) that this is not so.11 Thus -nuuʃA is evidently completely unable to occur in oblique case environments.

- (27)

- -nuuʃA cannot occur in oblique NPs whether oblique marking is present or not

- a.

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nuud-tə/*nuuʃə-tə/*nuuʃə

- cat-PL1-DAT/PL2-DAT/PL2

- mʲaxa

- meat

- ʉgɵɵb

- gave

- ‘I gave meat to the cats’

- b.

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nʉʉd-təi/*nʉʉʃə-təi/*nʉʉʃə

- cat-PL1-COM/PL2-COM/PL2

- xylgana

- mouse

- alaab

- killed

- ‘I killed the mice with the cats’

- c.

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nʉʉd-əər/*nʉʉʃ-əər/*nʉʉʃə-gəər/*nʉʉʃə

- cat-PL1-INST/PL2-INST/PL2-INST/PL2

- omogorxonob

- be.proud.of

- ‘I’m proud of the cats’

- d.

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nʉʉd-χəə/*nʉʉʃə-χəə/*nʉʉʃə

- cat-PL1-ABL/PL2-ABL/PL2

- gʉiʒə

- run

- arilaab

- go.away

- ‘I ran away from the cats’

- e.

- bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nʉʉd-aan/*nʉʉʃ-aan/*nʉʉʃə-gaan/*nʉʉʃə

- cat-PL1-ABL/PL2-ABL/PL2-ABL/PL2

- gʉiʒə

- run

- arilaab

- go.away

- ‘I ran away from the cats’

The fact that -nuuʃA causes legal omission of typical accusative / genitive marking, but is unacceptable in oblique environments whether usual oblique marking is present or not, will be central to the coming analysis.

4.1 The plural alternation is not phonological

The alternation between -nuud and -nuuʃA is not the result of a phonological process. The most straightforward phonological analysis of these plural forms would be to consider -nuuʃA a form derived from the plural -nuud plus a special case morpheme -ʃA that is syncretic for accusative and genitive, whose presence triggers deletion of the final /d/ of -nuud due to a phonological process that simplifies the potential [dʃ] cluster. Consistent with such an analysis is the fact that -nuudʃA is not a possible accusative or genitive form, as (28) shows:

- (28)

- -nuudʃA is not a possible plural accusative/genitive form

- a.

- xarxur-nuu(*d)ʃa

- fork-PL2.ACC/GEN

- b.

- galuu-nuu(*d)ʃa

- goose-PL2.ACC/GEN

- c.

- ɘgɘʃɘ-nuu(*d)ʃɘ

- girl-PL2.ACC/GEN

However, clusters with a consonant + [ʃ] are generally permitted in Barguzin Buryat, and indeed, forms with [dʃ] are possible outside of contexts like (28). This can be seen by combining the 2nd person singular possessive marker -ʃni with various nominal forms ending in /d/, as in the examples of (29). Most important of these is (29a), where we see the plural -nuud combining with such possessive morphology without any deletion:12

- (29)

- [dʃ] is a possible cluster

- a.

- buuza-nuud-ʃni

- dumpling-PL1-2SG.POSS

- amtatai

- tasty

- ‘Your dumplings are tasty.’

- b.

- basaga-d-ʃni

- girl-PL1-2SG.POSS

- ‘Your girls’

- c.

- buryad-ʃni

- buryat-2SG.POSS

- χaixan

- beautiful

- ‘Your Buryat (person) is beautiful’

Since [dʃ] is permitted by the phonology of this language, there is no obvious phonological explanation for the -nuud/-nuuʃA alternation. Thus I take this alternation to be morpho-syntactically conditioned suppletion. Given this conclusion, this alternation stands as a puzzle for the theories of case containment and suppletion described earlier in this paper.13 Before proceeding to the analysis, next I will consider the morphological decomposition of -nuud and -nuuʃA in more detail.

4.2 The morphological decomposition of plural marking

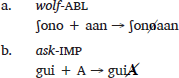

Here I will discuss a final fact about the morphological structure of plural marking in this language. So far, I have spoken in terms of two plural forms -nuud and -nuuʃA. These both contain a sub-part -nuu. In principle, it is conceivable either that this is a synchronic coincidence (perhaps with a diachronic explanation), or that -nuu is in fact a separate morpheme in the synchronic grammar. There is evidence suggesting that the latter hypothesis is the correct one. In particular, with certain nouns (often animate ones, but not only) -nuu may be excluded, leaving behind -d as the only expression of plurality, as in (30):

- (30)

- -nuu can be dropped from -nuud

- a.

- miisgɘi-(nuu)d

- cat-PL1

- mairana

- meow

- ‘Cats meow’

- b.

- mori-(nuu)d

- horse-PL1

- χaixan

- pretty

- ‘Horses are pretty’

- c.

- modo-(nuu)d

- tree-PL1

- χaixan

- pretty

- ‘Trees are pretty’

This suggests that -nuu is a separate morpheme, and that the basic plural marker in Barguzin Buryat is in fact -d. If this is so, then when we factor out -nuu, we come to the conclusion that the -nuud / -nuuʃA alternation is more fundamentally an alternation between two elements -d and -ʃA. This hypothesis accurately predicts the fact that the short plural -d can alternate with an alternative short plural form -ʃA, as demonstrated in (31) below. In (31a-b) we see nouns using the short plural -d in a nominative context, while in (31c-d), we see the same nouns in accusative contexts using a short plural -ʃA.

- (31)

- -d/-ʃA plural alternation in the absence of -nuu

- a.

- nʉxɘ-d

- friend-PL1

- jɘrɘɘ

- came

- ‘The friends came’

- b.

- maana-d

- 1P-PL1

- jɘrɘɘbdi

- came

- ‘We came’

- c.

- bi

- 1SG

- nʉxɘ-ʃɘ

- friend-PL2.ACC

- xaranab

- see

- ‘I see friends’

- d.

- ∅

- 3P

- maana-ʃa

- 1P-PL2.ACC

- duudaa

- called

- ‘Somebody called us’

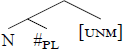

Thus we have evidence that -nuud and -nuuʃA actually contain a separate element -nuu that is correlated with plurality but not necessarily a plural marker itself.14 Consequently, I propose that the actual plural suffixes in Barguzin Buryat are -d and -ʃA. I will thus factor -nuu out of the coming analysis. This decision does not alter the puzzle that this paper focuses on. Given the relevant theories described earlier in the paper, any morphological process that is available in accusative and genitive cases, but not oblique ones, is unexpected. Since -nuu was present in all the plural examples reported in this paper until now, the puzzle that those facts pose is not affected by uniformly factoring out -nuu. Once this is done, the puzzle is conceptually the same, though cast in terms of -d versus -ʃA rather than -nuud versus -nuuʃA.

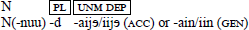

There are multiple ways of analyzing -nuu. For instance, this element could be part of a decomposed structure for number (Harbour 2014, a.o.) or an allomorph of a functional head like n0 (Embick & Marantz 2008; Embick 2010, a.o.) in plural contexts (though able to be omitted for certain nouns, as we’ve seen). However, the nature of this element does not have a direct bearing on the examination of the -d / -ʃA alternation. Thus in the coming analysis, for simplicity of exposition I will opt to diagram -nuu as a sub-part of the noun, beneath the nodes encoding number and case. With this final consideration addressed, we can now summarize the full set of relevant Barguzin Buryat facts as follows (32):

- (32)

- Case and plural marking in Barguzin Buryat (revised)

Basic plural Suppletive variant Nominative N(nuu)-d-∅ * Accusative N(nuu)-d-Aijɘ/iijɘ N(nuu)-ʃA Genitive N(nuu)-d-Ain/iin N(nuu)-ʃA Oblique N(nuu)-d-ABL/COM/DAT/INST… *

Given the case containment hypothesis, the fact that the -ʃA plural cannot occur in nominative contexts is expected, since nominative structures do not contain features related to accusative / genitive cases. However, accusative / genitive features are hypothesized to be a sub-part of oblique cases, which is why the impossibility of -ʃA in oblique contexts is surprising. In the next section, I will make explicit the analysis previewed in the introduction—that a morphological conflict is responsible for the fact that oblique morphology, and the -ʃA plural, have a complementary distribution. As a result of this conflict, only the basic plural -d is ever seen to co-occur with oblique morphology, and -ʃA thus has an ABA distribution.

5 The analysis: Spanning and competition

In this section, I will first state the VI rules that this analysis will depend on, and then show in detail how those rules, along with other considerations about competition in morphology, interact to predict the facts summarized in (32) above.

5.1 The necessary VI rules

Defining the VI rules necessary for this analysis will be facilitated by addressing a question for theories of case containment: if a case containment hierarchy like the one I have adopted in this paper holds cross-linguistically, then we must ask why the structural complexity attributed to many cases under such a theory is rarely surface-evident in a straightforward way. Smith et al. (2019) show that case morphology is sometimes surface-evidently complex in the expected way for two languages, Khanty and Kalderaš Romani (33). Nevertheless, the fact is that in most languages with overt case morphology, each case is simply expressed by one morpheme. For this reason, much recent work on case containment relies on relatively indirect evidence from phenomena like suppletion and syncretism.

- (33)

- Examples of surface-evident case containment

- (Adapted from Smith et al. 2019: p. 1037)

- a.

- Khanty

NOM ACC DAT 1SG ma ma:-ne:m ma:-ne:m-na 3SG luw luw-e:l luw-e:l-na 1PL muŋ muŋ-e:w muŋ-e:w-na

- b.

- Kalderaš Romani

NOM ACC DAT ‘brother’ phral phral-és phral-és-kə ‘brothers’ phral-(à) phral-én phral-én-gə ‘girl’ rakl-í rakl-já rakl-já-kə ‘girls’ rakl-já rakl-já-n rakl-já-n-gə

I hypothesize that for languages like Barguzin Buryat with mono-morphemic case marking rather than surface-evident containment, all features of the case hierarchy present in a given nominal structure are expressed by a single portmanteau morpheme.15 This is essentially the view taken in Caha (2009; 2013), whose Nanosyntactic approach to case entails that most case morphemes are mapped to a constituent containing several nodes of the hierarchy. As mentioned in the introduction, this paper will set Nanosyntax aside until section 6 below, instead focusing on a Distributed Morphology account in which portmanteau morphemes are formed by spanning—a mechanism that allows a single VI to ‘stretch’ across multiple contiguous terminal nodes.

Given these proposals, and following the version of the case hierarchy justified in section 2 above, we can state the VI rules for case morphology in Barguzin Buryat as in (34a-c) below. These rules state that nominative case expresses the feature [UNM] (34a), accusative and genitive case express the feature set [UNM DEP] (34b), and oblique cases express the set [UNM DEP OBL] (34c). In (34d-e), we also see the VI rules I posit for plural morphology. As previewed in the introduction (though now factoring out -nuu), I argue that the basic plural -d simply expresses a plural number node (34d), while the -ʃA plural is a portmanteau, as we see in (34e). Specifically, I argue that -ʃA expresses both a plural feature as well as the features corresponding to accusative / genitive case, which in the context of this account, are the features [UNM DEP]. This proposal accounts for the fact that the -ʃA plural bleeds the appearance of independent accusative / genitive case morphology, but can occur in contexts where those cases are typically assigned, provided that their corresponding morphology is omitted. We have seen this, for instance, in (23-24) versus (26) above.

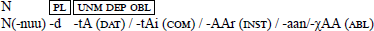

| (34) | VI rules for Barguzin Buryat case and number (final version)16 | |

| a. | [UNM] ⟺ ∅ (NOM) | |

| b. | [UNM DEP] ⟺ -(ai/ii)jɘ (ACC) / -(ai/ii)n (GEN) | |

| c. | [UNM DEP OBL] ⟺ -tA (DAT) / -tAi (COM) / -AAr (INST) / -aan/-χAA (ABL) | |

| d. | [#pl] ⟺ -d | |

| e. | [#pl UNM DEP] ⟺ -ʃA (Optionally supersedes the above) | |

We are now prepared to explain the patterns of Barguzin Buryat plural nominal morphology described in the previous section.

5.2 Superficial ABA due to morphological competition

Here I will discuss the derivation of each plural form one by one, which will lead straightforwardly into my explanation for why the distribution of -ʃA is restricted. For concreteness, I will assume that after a given syntactic structure is built and passed on to the PF component of the grammar, its terminals are then assigned linear order, after which VI rules apply (Embick 2010; Arregi & Nevins 2012; Haugen & Siddiqi 2016; Ostrove 2018; Davis 2020).

For a plural nominative nominal, the structure in (35a) is built. When completed and evaluated by the morpho-phonological component of the grammar, the linearization of that structure and the application of VI rules to it yields the representation in (35b). Here the plural number node is realized by -d, and the lone case node bearing [UNM] is assigned -∅, consistent with the fact that nominative case in Barguzin Buryat is systematically null. Note that here and throughout this section I ignore the realization of N, since this does not interact with the plural facts in focus here.

- (35)

- Plural nominative nominal

- a.

- Structure

- b.

- Linearization and VI

In this context, there is no possibility of using the -ʃA plural. As the VI rules in (34) above state, the features upon which the use of this morpheme depends are not present here. However, use of -ʃA becomes a relevant possibility when we consider accusative / genitive nominals.

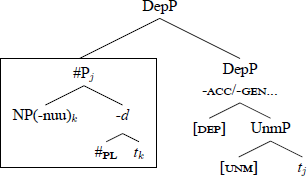

Following the version of the case hieararchy assumed in this paper, a plural accusative or genitive nominal has the same structure as a nominative one, aside from the addition of the next node up in the case hierarchy, which bears the feature [DEP]. This is shown in (36a) below. In (36b), we see the morpho-phonological form that is assigned to this structure in situations where the basic plural -d is used. In this context, following the VI rules defined in (34) above, -d expresses the plural node, while accusative / genitive morphology is inserted as a span that subsumes the two case nodes [UNM] and [DEP]. The facts have shown us that there is also another way to morpho-phonologically express the nominal structure in (36a). As the VI rules in (34) above state, such a structure can also be expressed by the -ʃA plural portmanteau. This is a span that realizes all of [#pl], [UNM] and [DEP], as (36c) shows:

- (36)

- Plural accusative / genitive nominal

- a.

- Structure

- b.

- Linearization and VI: Option 1 with basic plural

- c.

- Linearization and VI: Option 2 with portmanteau plural

Both of these strategies for realizing such a nominal structure are grammatical in Barguzin Buryat. Let’s consider this fact more deeply, since it connects to concepts that are vital for my explanation of the important puzzle that the -ʃA plural cannot arise in oblique contexts.

Human languages sometimes have multiple ways of realizing a given cell in a morphological paradigm—a state of affairs that Thornton (2011; 2012) terms overabundance. We can understand this fact as a consequence of two axioms of the Distributed Morphology framework: the elsewhere principle (Kiparsky 1973) and the subset principle (Halle & Marantz 1993, a.o.). These principles work together to mandate that the morpheme that is chosen to realize a given terminal node is the one that matches the largest subset of that node’s features. Importantly, it is possible for multiple morphemes to happen to correspond to equally large subsets of the features that a given terminal has. In this situation, both morphemes would be grammatical choices for expressing that terminal (as posited by Hein 2008; Halpert 2016; Driemel 2018). This would give rise to an instance of overabundance. A straightforward situation of this sort is the Barguzin Buryat ablative case, which as described above has two free variants: -aan and -χAA.

This understanding of morphological optionality is not directly applicable to the Barguzin Buryat plural forms in (36b-c) above: here we do not see multiple ways of realizing one terminal, but rather multiple ways of realizing the entire functional spine of the nominal. Importantly, Middleton (2020) extends the principles of Distributed Morphology to situations of precisely this sort in her spanning analysis of pronominal syncretism. Specifically, Middleton (p. 59, 68) argues that within a single spell-out domain, such as the functional extend projection of the noun, the combination of morphemes (some of which may be spans) is chosen that most thoroughly expresses the structure in question.17 Haugen & Siddiqi (2016) make a similar proposal in their analysis of the nature of spanning. On these grounds, the two Barguzin Buryat forms in (36b-c) are equally good choices, since both completely express the functional spine of the nominal. It is unsurprising, given these considerations, that both options are acceptable.18 This theory of morphological competition also explains the impossibility of -ʃA in oblique contexts, as I describe next.

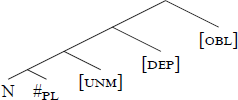

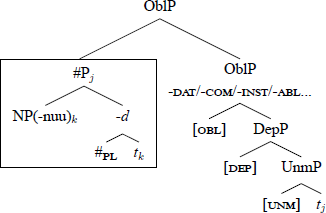

A plural oblique nominal will have a structure like that in (36a) above, but with the addition of the [OBL] feature, yielding a fully articulated case layer. We see this below in (37a). We have seen that this structure can only be realized in one way: with the basic plural -d and usual oblique morphology, the latter of which relizes all features present in the case hierarchy, as (37b) shows:

- (37)

- Plural oblique nominal

- a.

- Structure

- b.

- Linearization and VI

We saw in detail in the introduction and in section 4 (ex. 27) above that two other conceivable ways of realizing this structure are impossible. Next I provide an explanation for these facts.

First, it is not possible for the -ʃA plural to co-occur with oblique morphology, as demonstrated once more in a dative context in (38):

- (38)

- -ʃA plural does not co-occur with oblique morphology

- *bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nuuʃə-tə

- cat-PL2-DAT

- mʲaxa

- meat

- ʉgɵɵb

- gave

- ‘I gave meat to the cats’

Assuming that a given syntactic feature can only be morphologically expressed once (Bobaljik 2000), I argue that -ʃA and oblique morphology cannot co-occur because they overlap in the features they must express, given the VI rules defined in (34) above. To make this overlap clear, the features these morphemes express are shown in (39) in the context of an oblique nominal structure. Here we see that the features [UNM DEP] are where the overlap occurs:

- (39)

- -ʃA and oblique morphology both express [unm, dep]

- a.

- Plural -ʃA

- N(-nuu)

obl

obl

- b.

- Oblique morphology

- N(-nuu) PL

Second, while -ʃA and oblique morphology cannot co-occur, in principle it should be possible to assign -ʃA in the structure in (37a) above, and then simply not insert oblique morphology. This derivation would avoid the overlap problem. However, we have seen that such forms are not possible. We see this again in (40), an ungrammatical dative context including -ʃA but omitting dative marking:

- (40)

- Omitting oblique morphology fails to allow use of -ʃA

- *bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nuuʃə

- cat-PL2

- mʲaxa

- meat

- ʉgɵɵb

- gave

- ‘I gave meat to the cats’

I propose that morphological competition is responsible for the unacceptability of examples like (40). Following Haugen & Siddiqi (2016) and Middleton (2020), continue to assume that a structure must be expressed by the set of morphemes that most thoroughly realizes it. This hypothesis accurately rules out the form in (40): here the features [PL UNM DEP] are expressed by -ʃA, but a lone feature [OBL] is left unrealized. This contrasts with the form schematized in (37b) above, which expresses every feature in the functional projection of the noun by combining the basic plural -d with usual oblique morphology. Thus forms like (37b) block ones using only -ʃA such as (40).19

This concludes the main analysis. I have argued here that the ABA distribution of -ʃA is caused by its portmanteau-hood, which brings it into conflict with the morphological needs of oblique suffixes, and interacts with more general principles of morphological competition. Since this ABA pattern arises due to a confluence of independent factors, it does not falsify the morpho-syntatic theories discussed earlier in this paper for which ABA patterns are predicted to be unattested. Rather, these findings reveal a way that portmanteau morphemes can interfere with the principles that give rise to the *ABA generalization under normal circumstances.20 See section 7 for further discussion.

6 An alternative analysis using Nanosyntax

Much work on the *ABA generalization and related findings about suppletion typology uses the Nanosyntax framework (Starke 2009; Caha 2009, 2017a, b, 2018, 2019; De Clercq & Vanden Wyngaerd 2017). For this reason, it will be useful to address how the facts in focus in this paper can be analyzed in Nanosyntax. This is the purpose of this section.

In usual implementations of Distributed Morphology, VI rules apply terminal-by-terminal, assigning to each the morpheme that matches the largest subset of features that the terminal in question has (due to the subset principle). In contrast, the Nanosyntax framework functions in precisely the opposite way. Specifically, Nanosyntax posits that morpho-phonological form can be assigned to non-terminals (that is, XP or X’ nodes), and that the morpheme assigned to a given node is the one that matches the smallest superset of the features which that node contains (as defined by the superset principle). Both of these frameworks are designed to force selection of the morpheme that most closely matches the context of insertion, though in very different ways.

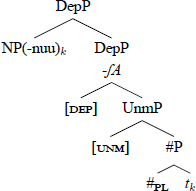

Due to its adoption of the Linear Correspondence Axiom (Kayne 1994), Nanosyntax assumes that syntactic structures are inherently head-initial, and therefore that the material which a suffix attaches to in the linear string moved in order for that suffix to be formed. This entails that a suffix of NP must be formed by NP moving and adjoining to a non-terminal node which contains a subset of the features which that suffixal morpheme is specified for. Thus to derive a noun with a plural suffix and a case suffix in Barguzin Buryat, the following must occur: First, NP must move to the edge of a constituent containing the [PL] node. That constituent can then be expressed as the plural suffix -d, as we see in (41) below. In (41), we also see the derivation of an accusative / genitive suffix. To achieve this, the node containing NP and the plural suffix (the boxed #P) moves to a position where its sister is the sub-tree containing the relevant case nodes, here [UNM] and [DEP]. That sub-tree can then be assigned accusative / genitive morphology, as (41) shows.21

- (41)

- Plural -d with accusative / genitive suffix

In (42) below we see a similar derivation instead involving an oblique suffix. Here movement of the #P containing NP and the plural suffix lands in a position where its sister is a sub-tree containing the nodes [UNM DEP OBL], which can be expressed with an oblique morpheme.

- (42)

- Plural -d with oblique suffix

Formation of the -ʃA plural will interact differently with the derivation of case suffixes, however. Since -ʃA is a suffix specified for the feature set [PL UNM DEP], its formation must involve movement of NP to a position whose sister is a node dominating those features, as in (43) below. This example illustrates a licit derivation for an accusative / genitive nominal, where the plural feature and all case features present are expressed together by insertion of -ʃA at an appropriate non-terminal position.

- (43)

- Licit derivation of an accusative / genitive NP with -ʃA

In (44) below, we see an attempted derivation of a form including -ʃA as well as an oblique suffix. Here all nodes of the case hierarchy are present, since this is an oblique structure. To derive -ʃA, movement of NP to the edge of a constituent dominating [PL UNM DEP] must occur, as we saw in (43) above. However, to derive an oblique suffix while preserving -ʃA, that constituent must then adjoin to a sub-tree which contains [OBL], as we see here in (44). If oblique morphology corresponds to the feature set [UNM DEP OBL] as argued earlier, then given the superset principle of Nanosyntax, an oblique suffix should be able to be assigned to the sub-tree containing just [OBL]. However, unlike the derivation in (43), the one in (44) encounters a problem.

- (44)

- Attempted combination of -ʃA and oblique suffix

Specifically, (44) violates another condition of Nanosyntax argued for by Caha (2009):

| (45) | The Anchor Condition (Caha 2009: p. 89) |

| In a lexical entry, the feature which is lowest in the functional sequence must be matched against the syntactic structure. |

The lowest feature in the case hierarchy is [UNM]. Notice that both [UNM] and [DEP] were displaced in the derivation of (44). Since [OBL] is thus separated from [UNM], the Anchor Condition prevents oblique morphology (specified as lexicalizing [UNM DEP OBL]) from being assigned here.

What has been said so far explains why -ʃA cannot combine with an oblique suffix: just as in the Distributed Morphology account I provided above, the fact that these two compete to express some of the same features prevents them from occurring at the same time. However, the fact that oblique morphology cannot be inserted in (44) does not automatically entail that this derivation should be ungrammatical: that is, we expect (44) to be grammatical, provided that oblique morphology is simply not inserted. However, recall that as we have seen in (27) above, a nominal marked with just -ʃA in an oblique context is unacceptable.

At least two concepts from the Nanosyntax literature are relevant here. On one hand, the exhaustive lexicalization principle (Fábregas 2007) predicts the ungrammaticality of (44), since it contains an un-lexicalized [OBL] feature. See Caha (2019) for further use of this principle. On the other hand, the backtracking operation (De Clercq & Vanden Wyngaerd 2017; Starke 2018; Caha 2019) would allow the derivation in (44) to be reversed and revised until it succeeds. This would have to eventually yield the structure in (42) above containing the basic plural and usual oblique morphology, which is the only licit possibility for a plural oblique nominal in Barguzin Buryat.22

We have just seen that Nanosyntax can account for the distribution of plural morphology in Barguzin Buryat. The shape of the account is, abstractly, very similar to the Distributed Morphology account I focused on in the majority of this paper: the fundamental issue is that an overlap problem prevents -ʃA and oblique morphology from co-occurring, and additional morphological conditions prevent -ʃA alone from successfully expressing such structures. Importantly, under either account the ABA distribution of -ʃA is attributable to the interaction of independent factors, and thus is significant because it reveals a way of subverting the principles that usually rule out ABA patterns.

7 Conclusion: The significance of these results

In this paper, I have described and analyzed an instance plural suppletion in Barguzin Buryat. This phenomenon is significant because it has an ABA distribution, which much recent work on the structure of case and the typology of suppletion predicts to be impossible. I have argued that the suppletive plural morpheme in Barguzin Buryat is actually a portmanteau of a plural feature and certain case features, resulting in a conflict with oblique morphology. As a result, for independent reasons this plural morpheme never occurs in oblique contexts, and therefore has an ABA distribution. Since this ABA pattern emerges from the interaction of independent factors, it does not falsify theories that ban ABA patterns under normal circumstances, but rather reveals a principled exception to them which deepens our understanding of them.

There is a growing body of evidence that ABA suppletion patterns exist, in particular at the sub-word level. See for instance the discussion of Basque adjectival suppletion in Bobaljik (2012), Bulgarian adjectival suppletion in Caha (2017b), as well as the analysis of syncretism in pronominal paradigms in Middleton (2020). Significantly, both Caha and Middleton argue that portmanteau morphemes play a role in creating the instances of ABA they respectively examine, precisely as I have argued for Barguzin Buryat. Thus it is clear that the Buryat pattern I analyze here is not an isolated idiosyncrasy, but rather a manifestation of a more general phenomenon of growing relevance to current morpho-syntactic research: that while ABA patterns may indeed be banned under normal circumstances, they can occur at the sub-word level when part of the word is expressed by a portmanteau form.

This finding is significant because it deepens our understanding of how the syntactic and morphological components of the grammar interact. This analysis of Barguzin Buryat also provides further support for the case containment hypothesis. Recall that -ʃA subsumes typical accusative / genitive morphology, but cannot co-occur with or subsume oblique morphology. Given that -ʃA evidently expresses accusative / genitive features, we accurately predict that -ʃA will conflict with oblique case marking by positing that oblique cases contain accusative / genitive features. The findings of this paper also strengthen the body of evidence for portmanteau morphemes that simultaneously express the features of multiple terminals. If such morphemes did not exist, a morphological overlap conflict like the one that this paper identifies would never occur.

Abbreviations

ABL = ablative case, ABS = absolutive case, ACC = accusative case, COM = comitative case, DAT = dative case, DEP = dependent case, ERG = ergative case, GEN = genitive case, INST = instrumental case, NOM = nominative case, NML = nominalizer, OBL = oblique case, P = person, PL1 = basic plural, PL2 = suppletive plural, SG = singular, POSS = possessive, UNM = unmarked case

Notes

- Unless otherwise cited, all Barguzin Buryat data reported here was elicited during the author’s fieldwork with two native speakers in Baraghan, Republic of Buryatia (Russia), August 2018. Fieldwork elicitation sessions consisted of asking speakers to translate test sentences into Barguzin Buryat (both orally and in writing), and to rate the acceptability of pre-prepared test sentences. [^]

- For additional recent work on the *ABA generalization and related topics, see Caha (2017a, b, 2019); De Clercq & Vanden Wyngaerd (2017); Andersson (2018); Baunaz & Lander (2018); Bobaljik & Sauerland (2018); McFadden (2018); van Baal & Don (2018), and Middleton (2020). [^]

- Barguzin Buryat is a differential object marking language, and thus some direct objects bear no case morphology. Since case morphology is the topic of this paper, objects that have no case morphology are not relevant here. [^]

- Notice that the final vowel of -nuuʃA is not present in the examples of (10). There is a phonological reason why this is indeed what we would expect to occur in such examples, which I explain in detail in section 4. [^]

- Classifying these cases as being versions of ‘dependent’ case is one way of achieving this unification. While some works take genitive case to be an ‘unmarked’ case and thus essentially the nominal-internal counterpart of nominative (Marantz 1991; Levin & Preminger 2015, a.o.), cross-linguistically it is common for genitive morphology to be related to or syncretic with ‘marked’ cases like dative and ergative (Comrie 1978; Baker 2015). Baker (2015) points out that the syntax of possession is parallel to the configuration in which dependent ergative case is taken to be assigned in Marantz (1991) and related works, and that thus some instances of genitive case can be considered parallel to dependent ergative. In contrast, Baker argues that genitive is not parallel with dependent accusative case, though he notes two languages where genitive and accusative are syncretic—Martuthunira (Pama-Nyungan) and Karachai-Balkar (Turkic). While the precise nature of genitive case is a subject of ongoing debate (see for instance Harðarson 2016; van Baal & Don 2018), it is clear that there is a well-established relationship between ‘marked’ cases and genitive. See also Starke (2017), who argues that cross-linguistic variance in the relationship between cases like dative, accusative, and genitive provides evidence for a richer case hierarchy. Specifically Starke argues that there are in essence ‘small’ datives and accusatives which are lower on the hierarchy than genitive, as well as ‘big’ ones which are above genitive. Variance in which part of the hierarchy languages use determines what morphological patterns will be attested in them. Since internal to Barguzin Buryat we arrive at the right results by positing that accusative and genitive have the same position in the hierarchy, I will set richer case hierarchy proposals aside here. [^]

- Note that my adoption of a hierarchy organized in terms of the case categories of Marantz (1991) is not vital here. All that matters is the structural relationship between the various case features. The way that we choose to label them is fundamentally tangential. However, since the highly relevant works Zompì (2017) and Smith et al. (2019) argue for a case hierarchy organized in terms of these categories, it is convenient to adopt the same terminology here. Note that there is independent evidence for taking Marantz’s case categories seriously, for instance, from facts about case discrimination in agreement (Bobaljik 2008; Branan 2018). [^]

- The -nuu sub-part of -nuud and -nuuʃA in fact varies between [nuu] and [nʉʉ]. While this is likely another effect of vowel harmony, speakers intuitions about which form of this element to select were often unclear. Since [nuu] was the most frequent choice, for simplicity I speak in terms of -nuud/-nuuʃA in this paper. [^]

- The accusative forms -Aijə and -iijə are generally in free variation, as are the genitive forms -Ain and -iin, though for some nouns one variant is judged as preferable. A generalization about when one variant is preferred over the other is not obvious based on the available data. Thus this may be a matter of lexical idiosyncrasy. The forms -Aijə/-iijə and -Ain/-iin are also sometimes truncated to just -Ai/-ii, rendering accusative and genitive marking syncretic. [^]

- This paper focuses on instances of -nuuʃA on objects and possessors, since these are the most basic environments in the language for accusative and genitive case, respectively. The subjects of embedded clauses can also sometimes be either accusative or genitive (Bondarenko 2018; Tatevosov et al. To appear), and as expected, when such subjects are plural, -nuuʃA is available for them (i):

- (i)

- a.

- ojuna

- Ojuna

- [miisgɘi-[nʉʉd-iijɘ]/nʉʉʃɘ

- cat-PL1-ACC/PL2.ACC

- zaguu

- fish

- ɘdjɘɘ]

- ate

- gɘʒɘ

- C

- hanana

- thinks

- ‘Ojuna thinks that the cats ate fish.’

Thus this alternation is not about objects or possessors in particular, but accusative and genitive case in general. [^]- b.

- [miisgɘi-[nʉʉd-ai]/nʉʉʃɘ

- cat-PL1-GEN/PL2.GEN

- zaguu

- fish

- ɘdj-ɘ:ʃ-i:n]

- eat-NML-3POSS

- sajan-aijɘ

- Sajana-ACC

- gaaruulaa

- angered

- ‘That the cats ate the fish angered Sajana.’

- Since /g/-epenthesis only occurs between heavy vocalic segments as shown in (19) above, we do not expect the examples of (26) to be grammatical if /g/ were inserted between -nuuʃA and the accusative/genitive marker, instead of deleting the final short vowel of -nuuʃA. Such examples are indeed unacceptable (i):

- (i)

- a.

- *bi

- 1SG

- miisgəi-nʉʉʃə-gəijə

- cat-PL2-ACC

- xaranab

- saw

- ‘I saw cats’

[^]- b.

- *miisgəi-nʉʉʃə-gəin

- cat-PL2-GEN

- xʉʉl-nʉʉd utа

- tail-PL1 long

- ‘The cats’ tails are long’

- The behavior of -nuuʃA is superficially suggestive of this morpheme having a requirement to be aligned to the right edge of the word, and thus not to be followed by any additional suffixes. The interaction of -nuuʃA with possessive markers indicates that there is no such general rule. In Barguzin Buryat, possessed noun phrases include a suffix agreeing with their possessor. Such possessive marking stacks on top of typical case marking (ia-b). This possessive marking also stacks on top of -nuuʃA (ic-d).

- (i)

- a.

- ajmag-iijə-mni

- district-ACC-1SG.POSS

- b.

- noxoi-n-ʃni

- dog-GEN-2SG.POSS

- c.

- ʃono-nuuʃ-iinʲ

- wolf-PL2.ACC/GEN-3SG.POSS

The account of this paper will correctly predict that -nuuʃA conflicts only with case marking, but not with other affixes. [^]- d.

- buuza-nuuʃ-iimni

- dumpling-PL2.ACC/GEN-1SG.POSS

- Example (29b) also involves a plural, but a ‘short’ plural -d rather than the full plural form -nuud. Since the -nuu component of plural forms can sometimes be dropped, I will analyze -nuu as being a separate morpheme, as mentioned in the introduction and described in section 4.2 below. [^]

- It is worth asking whether -nuuʃA might be derived by affixing the accusative -jɘ to -nuud, resulting in a form -nuudjɘ that phonology converts into -nuuʃA. Such an account would describe the facts if we suppose that -jɘ can behave as a syncretic expression of accusative and genitive case (at least in plural contexts). There are several reasons to suspect that such an analysis is not correct. First, I am aware of no evidence that -jɘ can act as a realization of genitive case. Though this possibility was not tested during my fieldwork, no examples of this variety are attested in the data available to me. Second, this hypothesis requires positing that the cluster /dj/ is phonologically converted into [ʃ]. As far as I am aware, Barguzin Buryat does not have /Cj/ clusters per se. However, as Staroverov & Zelensky (To appear) describe, this language does have productive consonant palatization, and therefore has a wide variety of forms containing instances of /Cj/, which are often phonetically similar to /Cj/ clusters. Importantly, [dj] is attested in the language, and is clearly a voiced alveolar plosive combined with palatization (and perhaps a residual glide), rather than a segment anything like [ʃ]. We see this in examples (22b) and (23a) above in the root ədʲə (‘eat’), for instance. Since the conversion of /dj/ into [ʃ] would presumably involve a process like palatization, the fact that palatized [d] does not become a palatal fricative suggests that such a phonological process is not at work in the formation of -nuuʃA. Additionally, to derive [ʃ] from /dj/ it would also be necessary to posit the application of devoicing. Since both /ʃ/ and /ʒ/ are productive phonemes in this language, it is unclear what would motivate such devoicing. Finally and most decisively, there is a straightforward difference between the -nuuʃA plural and the accusative -jɘ which shows that the former is not derived via the latter. For the hypothesis under consideration, the -ʃA component of -nuuʃA is a phonologically modified version of the accusative -jɘ. However, this -ʃA contains a harmonizing low vowel /A/, while the accusative -jɘ contains a non-harmonizing vowel /ɘ/. The harmonizing property of -nuuʃA can be seen by comparing (23a) and (23b): In the former, -nuuʃA affixes to the noun root buuza (‘dumpling’), with which -nuuʃA harmonizes to become [nuuʃa]. In the latter, -nuuʃA affixes to the root əgəʃə (‘sister’), with which -nuuʃA harmonizes and becomes [nuuʃə]. In contrast, the accusative -jɘ is phonologically consistent in all environments, since it does not contain a harmonizing vowel. This morpho-phonological difference demonstrates that -nuuʃA is not derived via affixation of the accusative -jɘ to the plural -nuud. [^]

- Plural marking consisting of one obligatory component and another optional component is known of in other languages. See for instance De Belder (2018) on Breton, and references therein. [^]

- At the very least, I argue that this hypothesis yields the right results for Barguzin Buryat. It is possible that in other languages with mono-morphemic case marking there is no use of portmanteau morphology, but rather simply no morphological realization of most features in the case hierarchy. [^]

- In (34) I have defined accusative and genitive morphology as corresponding to the same set of features, for the reasons described in section 2. There I proposed that these forms of case morphology both instantiate ‘dependent case’, but that the realization of this case category depends on syntactic context—genitive morphology arising when the relevant NP is embedded in a nominal environment (as in possessive structures), and accusative morphology arising otherwise. The different distribution of these cases, as well as the distinction between the various obliques, could also be captured by adopting a more fine-grained case containment hierarchy such as that in Caha (2009). Alternatively, such distinctions could be captured by positing that each variety of case morphology corresponds to a different variant of the relevant case feature (DEP1, DEP2, OBL1, OBL2, OBL3, and so on). Since this degree of precision would complicate the implementation without shedding any additional light on the primary topic of this paper, I set this aside. [^]

- As Middleton discusses, this extension is in opposition to works like Embick & Marantz (2008), who argue that competition applies only at the level of individual terminals. Such a theory is incompatible with one in which spanning is possible, for which competition beyond individual terminals is necessary. [^]

- This fact about Barguzin Buryat is in conflict with the Minimize Exponence principle of Siddiqi (2009). This principle prefers derivations that realize a given structure with the smallest possible number of morphemes, and thus incorrectly predicts that the form in (36c) should block that in (36b). Haugen & Siddiqi (2016) note (p. 370, footnote 24) that such a principle is implicit in much work, but not uncontroversial. [^]

- This blocking analysis works as intended whether we define morphological competition in the way that Middleton (2020) does, or follow Haugen & Siddiqi (2016) in adopting the Post-Linearization Contiguous Morpheme Insertion Principle (p. 369, ex. 12), which allows a morpheme to span across a set of adjacent heads only if the spanned morpheme expresses as least as many features as would have been expressed by a greater number of separate morphemes. These works make similar proposals about the nature of morphological competition, but differ in their implementation and emphasis in ways that are not relevant to this paper’s analysis. Blocking is not the only possible explanation for the unacceptability of forms like (40), but it is likely the simplest one. Arregi & Nevins (2014) propose that certain Spanish verbs lack an elsewhere exponent, and therefore fail to be realized under certain conditions, yielding ungrammaticality. Similarly, we might posit that (40) is illicit because a lone oblique feature lacks an elsewhere exponent, and that its inexpressibility makes the derivation deviant. While there are indeed works arguing that some structures are ungrammatical due to being ineffable (Coon & Keine 2020), this line of reasoning is fundamentally incompatible with the subset principle, which allows many syntactic features to remain unexpressed due to the under-specification inherent to VI rules. An account appealing to ineffability thus must step into controversial territory, unlike the blocking account I have proposed here. [^]