1 Introduction

The goal of this paper is to investigate the compatibility of focus particles with concessive clauses (concessives)1 in Serbian in order to test the observed generalization that, across languages, concessives resist focusing by focus particles (e.g. König 2006; Mizuno 2007, and references there). Cross-linguistically, concessives, unlike the majority of adverbial clauses, cannot be used in the scope of focus particles such as only, even, just, or especially, as illustrated in (1) from English on a pair comprising a causal and a concessive clause (cf. König 2006). According to König (2006), this is due to the constraint on the focusability of concessives, taken to indicate their less tight integration with the main clause in comparison to other adverbial clauses.

- (1)

- a.

- Only / even / just / especially because it is raining, I’m not going to play football.

- b.

- (*Only) / (*even) / (*just) / (*especially) although it is raining, I’m going to play football.

Symptomatically, one of the ‘complex’ concessive conjunctions in English consists of the focus particle even and the ‘proper’ conjunction though, as in (2a) – although a version without even is available too (2b), with the same meaning (Lund 2017).

- (2)

- a.

- Even though it’s raining, John went for a walk.

- b.

- Though it’s raining, John went for a walk.

Lund (2017) proposes an analysis of even though where though is a focus operator introducing a set of alternatives that are exhaustified by even, leading to an LF as in (3).

- (3)

- (Lund 2017: the analysis of ex. (2))

- a.

- Even(C) [[thoughF it’s raining], John went out for a walk] ∼ C

- b.

- Assertion: though it’s raining, John went for a walk = p ∧ q

- c.

- Alternatives: {p ∧ q (= a1), ¬p ∧ q (= a2)}

- d.

- Scalar presupposition: ∀q ∈ {a1, a2}[q ≠ p → p <likely/expected q]

- ⇔ a1 <likely/expected a2

- ⇔ (p ∧ q) <likely/expected (¬p ∧ q)

As obvious from (3), Lund assumes that both p and q are asserted and that the relevant alternatives subject to scalar ranking (brought about by even) are p ∧ q (It’s raining ∧ John went for a walk) and ¬p ∧ q (It’s not raining ∧ John went for a walk). Lund contends that the scalar presupposition ((p ∧ q) <likely/expected (¬p ∧ q)) captures the concessive flavor of the even-though-construction (in prose: ‘John going for a walk given that it’s raining is less likely than him going for a walk when it’s not raining’). Since sentences introduced by though (without even), as in (2b), have the same meaning and distribution as even-though-sentences, Lund (2017) argues that in this case even is present too, albeit covertly. We take that (3) describes standard concessives, i.e. concessives expressing the standard concessive relation (König 2006); see §2.1 for concessive relations.

We provide theoretical and quantitative evidence from Serbian that all standard concessives inherently include a scalar focus particle (although our implementation differs from Lund’s in some respects). Consequently, concessives cannot combine with (other) focus operators/particles (e.g. only, just, especially) because they are already inherently focused – additional focus particles are in complementary distribution with the focus particles contained in concessives.

Concessives in Serbian marked by conjunctions iako, mada and premda ‘although’ (traditionally analyzed as fully synonymous, Stevanović 1989; Stanojčić & Popović 2008; Kuburić Macura 2021) generally fit in the picture sketched above, i.e. they resist focus particles. There is one apparent exception: the focus particle čak ‘even’ can be paired with the conjunction iako ‘although’ (resembling English even though), as in (5).2 We argue that this exception is only apparent because this particle, overt or covert, is an integral part of constructions with standard iako-concessives. However, even iako-clauses are not always felicitous with čak ‘even’, as in (6–7).

- (4)

- (*Jedino)

- only

- /

- (*samo)

- just

- /

- (*čak)

- even

- premda / mada

- although

- nije

- cop.neg

- gladna,

- hungry

- jede.

- eats

- ‘(*Only) / (*just) / (*even) although she is not hungry, she is eating.’

- (5)

- (*Jedino)

- only

- /

- (*samo)

- just

- /

- čak

- even

- iako

- although

- nije

- cop.neg

- gladna,

- hungry

- jede.

- eats

- ‘(*Only) / (*just) / even though she is not hungry, she is eating.’

- (6)

- Ućutao

- fell_silent

- je,

- aux

- (*čak)

- even

- iako

- although

- to

- that.dem

- ćutanje

- silence.nom

- nije

- aux.neg

- dugo

- long

- potrajalo.

- lasted

- ‘He fell silent, (*even) although the silence did not last long.’

- (7)

- Ova

- this

- haljina

- dress.nom

- je

- cop

- lepa,

- nice

- (*čak)

- even

- iako

- although

- je

- cop

- baš

- exactly

- skupa.

- expensive

- ‘This dress is beautiful, (*even) though it is very expensive.’

These observations regarding the focusability of concessives in Serbian have led us to the following two main research questions:

- Q1)

- What enables only concessives with the conjunction iako to be compatible with the focus particle čak ‘even’? From the alternative perspective: why cannot clauses with the other two concessive conjunctions introduced above – mada and premda – be used in the scope of čak ‘even’? (cf. (4–5))

- Q2)

- In which semantic, syntactic and/or pragmatic contexts can the conjunction iako not be combined with the focus particle čak, and why? (cf. (6–7))

To assess Q1 and Q2, the following hypotheses have been tested:

- H1)

- The type of concessive relation (standard, rectifying, or rhetorical; see §2) affects the ability of concessives to (not) allow the compatibility with the particle čak ‘even’.

- H2)

- The compositional structure of concessive conjunctions, i.e. the nature of the components they consist of, correlates with the compatibility of these conjunctions with the particle čak ‘even’.

Based on the theoretical and quantitative explorations presented in §2–§3, we show that both H1 and H2 are confirmed. Specifically, we argue that čak ‘even’ is possible only with iako-clauses that mark the standard concessive relation. Such compatibility – and its lack with other conjunctions, as well as with other types of concessive relations with iako-clauses – follows from the fact that iako-clauses in standard concessives always contain čak ‘even’, albeit a covert one, analogously to the covert even in Lund’s (2017) approach introduced above. In other words, when čak ‘even’ appears with iako-clauses in standard concessives, it is an overt realization of the underlyingly always available operator with the same semantic contribution as čak. We also argue that the conjunctions mada and premda compositionally involve scalar focus particles ma(kar) ‘at least, even’ (cf. also Arsenijević 2021), and prem ‘opposite’, respectively, which are (morphologically) combined with the subordinator da. The advantages of our proposal can be stated as follows:

It explains why čak combines only with the conjunction iako, but not with mada and premda – the latter two already contain a scalar particle.

It accounts for why čak is found only with standard iako-concessives, but not with other types of concessive relations, which crucially do not rely on the scalar likeliness/expectedness presupposition.

It explains why only čak is found with standard iako-concessives, but not other focus particles: if there is always a covert čak, other focus particles are in complementary distribution with it.

It enables accounting for the differences between concessive conditionals introduced by i + ako (roughly, even if in English) and ‘genuine’ concessives introduced by iako ‘although’ – only in the latter there is a covert čak, and hence they always come with a scalar presupposition, unlike concessive conditionals.

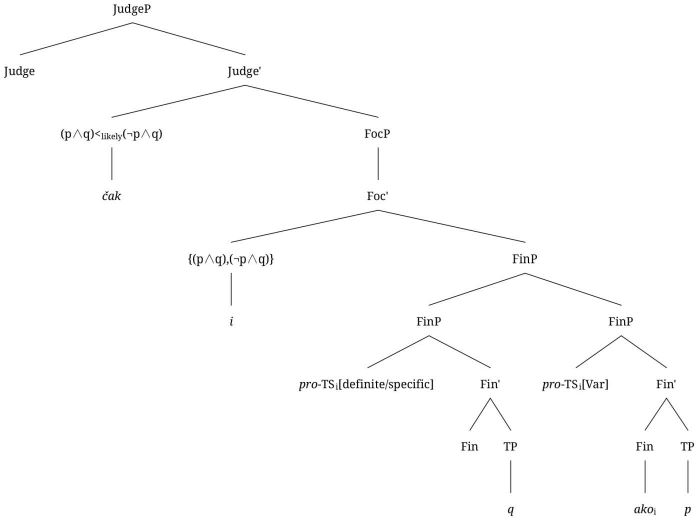

Our proposal has important consequences for the syntactic analysis of concessives, to be outlined in §4. For now, let us provide a brief rationale. In recent syntactic approaches, (standard) concessives are analyzed as modifiers of perspective-related projections such as EpistP or EvidP in Lund & Charnavel (2020) or Krifka’s (2023) JudgeP in Frey (2020). The novelty of our proposal is in that only a scalar focus particle is merged in the epistemic/evidential domain (JudgeP), which is where the expectedness relation [(p ∧ q) <likely/expected (¬p ∧ q)] is introduced – but not the concessive clause itself. The subordinate clause attaches at FinP immediately above TP.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In §2, we introduce the main types of concessive relations recognized in the literature and present the results of our corpus research on how different concessive conjunctions in Serbian correlate with these types of concessive relations and with the focus particle čak. In §3, we analyze concessive conjunctions in Serbian as complex conjunctions and examine the compositional contribution of the morphemes they consist of. After sketching the syntactic analysis in §4, we conclude in §5.

2 Types of concessive relations and Serbian concessive conjunctions

To test whether the type of concessive relation affects the ability of concessives to (not) combine with the particle čak ‘even’ (H1), we looked at a random sample of 1.809 contextualized examples of concessives from the Corpus of Contemporary Serbian (CCS)3 and srWaC.4 Each of the concessive conjunctions discussed – iako, mada, premda – is equally represented: 603 examples per conjunction. The examples are manually annotated for various parameters, including the type of concessive relation and compatibility with the particle čak. We first introduce different concessive relations and then present the results of our corpus analysis.5

2.1 Types of concessive relations

The literature on concessives recognizes three main types of concessive relations, exemplified by (8–10), which we refer to as standard, rectifying, and rhetorical concessives, respectively, following König (1988; 1994; 2006) and Mizuno (2007).

- (8)

- (König 2006)

- Although it is raining, Fred is going out for a walk.

- (9)

- (Mizuno 2007)

- My family was unusual in that they only spoke Wolof, although my 19-year-old “sister” remembered a smattering of French from school.

- (10)

- (König 1988)

- Even though this solution would be harmful to our enemies, the damage done to us would be even greater.

The standard concessive relation (8) is the most common use of concessives. According to König (2006: 821), in uttering a complex sentence with a standard concessive (although p, q), the speaker commits to the truth of both clauses and asserts these two propositions against the background assumption, roughly describable as ‘if p, then normally not-q’; in (8): ‘if it is raining, one normally does not go out for a walk’. The denial of expectation (based on the background assumption) is considered a crucial feature of this type of concessive relation, which is why this relation is often labeled denial of expectation (e.g. Blakemore 1989; Spooren 1989; Noordman 2001).

The function of rectifying concessives is to restrict the preceding utterance (Günthner 2000: 454; König 2006: 824). For instance, the concessive in (9) rectifies the interpretation of the main clause by pointing out an exception – ‘19-year-old sister’. Rectifying concessives are generally postponed w.r.t. the matrix clause, which correlates with their function to restrict the preceding statement.

A complex sentence with the rhetorical concessive relation expresses that the first clause is an argument for a conclusion, whereas the second clause is an argument for the opposite conclusion, and carries more weight in the overall argumentation (König 1985: 5; 2006: 823). For instance, in (10), the content of the first clause evokes a conclusion that the solution is suitable, whereas the content of the second clause implies the opposite conclusion. The overall assessment is that the speaker does not consider the solution suitable after all. Rhetorical concessives are usually introduced by the adversative conjunction but, as in (11b), which is a near counterpart of the although-sentence in (11a).

- (11)

- (König 1985)

- [Somebody is looking for a good actor with brown eyes.]

- a.

- Although he certainly knows his job, he has got blue eyes.

- b.

- He certainly knows his job, but he has got blue eyes.

2.2 Corpus exploration of Serbian concessive conjunctions

We now move to the corpus analysis, which explores the correlation between different concessive conjunctions in Serbian, the concessive relations presented in §2.1, and compatibility with the focus particle čak. The results are summarized in Table 1.

The type of concessive relation and focusability.

| Standard concessives | Focus particle čak | Rectifying concessives | Focus particle čak | Rhetorical concessives | Focus particle čak | Others | |

| iako | 521/603 (86,4%/) | ✔(all examples) | 44/603 (7,3%) | ✖ | 1/603 (0,2%) | ✖ | … |

| mada | 194/603 (32,2%) | ✖ | 224/603 (37,1%) | ✖ | 1/603 (0,2%) | ✖ | … |

| premda | 234/603 (38,8%) | ✖ | 225/603 (37,3%) | ✖ | 40/603 (6,6%) | ✖ | … |

As can be observed from the table, the conjunction iako is used most commonly with standard concessives (86,4%), as in (12), whereas in rectifying (13) and rhetorical contexts (14), it is used sporadically (7,3% and 0,2%, respectively).

- (12)

- Na

- on

- posao

- job.acc

- primili

- received

- direktorovu

- director’s

- svastiku,

- cousin.acc

- [čak]

- even

- iako

- although

- nije

- aux.neg

- ispunjavala

- fulfilled

- sve

- all

- uslove.

- conditions.acc

- ‘They hired the director’s cousin, even though she didn’t meet all the requirements.’ (CCS)

- (13)

- Posećivali

- visited

- su

- aux

- se,

- refl

- iako

- although

- retko.

- rarely

- ‘They visited each other, although rarely.’ (CCS)

- (14)

- Iako

- although

- sam

- aux

- brzo

- quickly

- utonula

- sank

- u

- in

- san,

- dream.acc

- vrlo

- very

- brzo

- quickly

- sam

- aux

- se

- refl

- i

- and

- probudila.

- woke_up

- ‘Although I quickly fell asleep, I woke up very quickly.’ (CCS)

Table 1 further shows that only the conjunction iako is compatible with the focus particle čak – exclusively in its standard concessive use. These results are based on the two native annotators’ intuitions regarding the compatibility of čak with concessives extracted from the corpus. In the actual sentences from the corpus, čak is found with standard iako-concessives five times, whereas its use with mada and premda is not attested. Additionally, we verified the compatibility of čak with concessives from another perspective – by checking the number of combinations of čak with concessive conjunctions in the overall srWaC corpus. Specifically, we looked at how many times each of the three conjunctions is attested and how frequently it is used with čak. The results summarized in Table 2 confirm that only iako is found with čak. Judging by the first 300 examples among 1793 attestations with čak, all such examples illustrate the standard concessive relation.

Frequency of concessive conjunctions in srWaC.

| iako | čak+iako | mada | čak+mada | premda | čak+premda |

| 215.622 (388.8 per million) | 1.793 (3.2 per million) | 81.569 (147.1 per million) | 0 | 5.619 (10.1 per million) | 0 |

An important question that emerges is why examples with the overt čak are much less frequent than those without čak, i.e. with a covert čak on our analysis. We address this issue in §3.1.3.

Returning to Table 1, it can be observed that the conjunctions mada and premda are employed almost equally both with standard concessives (32,2% and 38,8%), illustrated in (15–16), and rectifying concessives (37,1% and 37,3%), exemplified by (17–18).

- (15)

- Mada

- although

- sam

- aux

- imao

- had

- u

- in

- planu

- plan.loc

- da

- comp

- dođem

- come.1sg

- dva

- two

- dana

- day

- ranije,

- earlier

- ipak

- still

- nisam

- aux.neg

- uspeo

- succeeded

- zbog

- because_of

- jakog

- strong

- nevremena.

- storm.gen

- ‘Although I had planned to come two days earlier, I still didn’t make it because of the strong storm.’ (srWaC)

- (16)

- Premda

- although

- živimo

- live.2pl

- u

- in

- doba

- period

- visoke

- high

- tehnologije,

- technology.gen

- arhitektura

- architecture.nom

- ostaje

- remains

- zavjetovana

- vowed

- mistici.

- mysticism.dat

- ‘Although we live in an age of high technology, architecture remains committed to mysticism.’ (srWaC)

- (17)

- Nakon

- after

- nekoliko

- few

- meseci

- months.gen

- ožiljci

- scars.nom

- počinju

- start.3pl

- da

- comp

- blede,

- fade.3pl

- mada

- although

- nikada

- never

- neće

- will.neg

- nestati

- disappear.inf

- u

- in

- potpunosti.

- completeness.loc

- ‘After a few months, the scars begin to fade, although they will never disappear completely.’ (srWaC)

- (18)

- Kod

- at

- njih

- them.gen

- skoro

- almost

- da

- comp

- nije

- aux.neg

- bilo

- was

- bolesti,

- disease.gen

- premda

- although

- je

- aux

- bilo

- was

- smrti;

- death.gen

- ali

- but

- njihovi

- their

- su

- aux

- stari

- old_ones

- umirali

- died

- tiho…

- quietly

- ‘There was almost no disease among them, although there was death; but their old ones died quietly…’ (srWaC)

The conjunction premda, illustrated in (19), is the best choice when the rhetorical relation is intended: premda is used with rhetorical concessives in 6,6% of examples, iako and mada in 0,2% each.

- (19)

- Najgori

- worst

- je

- cop

- đak

- student.nom

- po

- by

- učenju,

- learning.loc

- premda

- although

- najbolji

- best

- po

- by

- vladanju.

- governance.loc

- ‘He is the worst student in terms of learning, although he is the best when it comes to behavior.’ (CCS)

If we look at the results from the perspective of types of concessive relation, as in Table 3, the mapping between the type of relation and the three conjunctions becomes even clearer. Namely, the standard concessive relation is best associated with iako (55%), rectifying concessive relation favors premda (46%) and mada (45%), while the rhetorical concessive relation is expressed, almost as a rule, by premda (89%). The particle čak is compatible only with iako in standard concessives.

The mapping between the type of a concessive relation and concessive conjunctions.

| iako | mada | premda | others | focus particle čak | |

| Standard concessives | 55% | 20% | 25% | … |

/ premda / mada / premda / mada

|

| Rectifying concessives | 9% | 45% | 46% | … | iako / premda / mada |

| Rhetorical concessives | 9% | 2% | 89% | … | iako / premda / mada |

In §3, we present a decompositional analysis of the three concessive conjunctions under discussion and point out the relation between the morphemes they consist of and their compatibility with the focus particle čak across different types of concessives.

3 Decomposing concessive conjunctions

It has been reported in the literature that cross-linguistically concessive conjunctions are typically complex, with an identifiable compositional make-up: al-though in English, ob-wohl in German, aun-que in Spanish, etc. (see König 2006 for an overview). Concessive conjunctions in Serbian iako, mada and premda can be decomposed as follows: i+ako ‘and+if’, ma(kar)+da ‘at_least+comp’, prem+da ‘opposite+comp’. In this section, we provide a compositional analysis of these conjunctions, showing that their (in)ability to combine with the focus particle čak ‘even’ can be compositionally derived from the syntax and semantics of the morphemes they consist of.

3.1 Iako: [čak ‘even’] + i ‘and’ + ako ‘if’

The conjunction iako consists of two primitives: i ‘and’ and ako ‘if’ (see also Arsenijević 2021). We argue that the syntax and semantics of this conjunction can be derived from the elements it is composed of: the conjunction/particle i ‘and’ adds an additive presupposition, whereas the subordinator ako ‘if’ acts as a relativizer, following the approach in Arsenijević (2006; 2009a; b; 2021) that all subordinate clauses are relative clauses (see §4 for the rationale). Crucially, we also argue that standard concessives, which are the most typical context for the conjunction iako (see §2.2), include a scalar focus particle/operator responsible for a scalar presupposition that ranks alternatives invoked by iako-clauses on the scale of likeliness/expectedness. This scalar particle either remains covert, or is overtly expressed by the particle čak ‘even’, as introduced already in (5). The contribution of čak ‘even’ is fully compositional and is shared by other uses of this particle in Serbian (for similar claims in English, see Guerzoni & Lim 2007; Lund 2017; Zhu 2019, and references therein).

Before presenting all three relevant components in the subsequent three subsections (§3.1.1–§3.1.3), let us briefly illustrate the proposed analysis with the standard iako-concessive in (20).

- (20)

- [Witnessing the event directly, under the standard background assumption that Mara usually runs when it doesn’t rain.]

- Čak

- even

- i-ako

- and-if

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Mara

- Mara.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Even though it’s raining, Mara is running.’

In (20), the relativizer ako ‘if’ introduces a (concessive) relative clause and links it to the main clause (see §4 for details). With Arsenijević (2021), we take that the relativization site in the case of concessives is their Topic Situation (TS).6 The TS of a concessive is co-indexed with the definite/specific TS of the main clause, and as a result, it receives a definite/specific interpretation – since both clauses refer to the same definite/specific situation. Hence, in (20), it is asserted that Mara is running in a definite/specific situation (most probably, the actual situation) and that in the same situation, it is raining.7 A potential issue for such an analysis could be that concessives are usually analyzed as fully-fledged assertions, with their own truth conditions independent of the truth conditions of the main clause (cf. Arsenijević 2021). Yet, we propose that the referential status of the iako-clause is not independent of the main clause. The illusion of an independent assertion of the concessive comes exactly from the fact that its TS gets a definite/specific interpretation via co-indexation with the definite/specific TS of the main clause.

The conjunction i ‘and’ is responsible for the additive presupposition, i.e. it introduces the alternatives formed of the relevant conjunctions, as in (21).8 This aligns with the general role of i in activating alternatives (Gajić 2019) and/or domain-widening (Arsenijević 2021).

- (21)

- Additive presupposition (contributed by i ‘and’)

- Alternatives: {p ∧ q (= a1); ¬p ∧ q (= a2)}

- = {It is raining ∧ Mara is running; It is not raining ∧ Mara is running}

Finally, the role of the particle čak ‘even’ is to rank these two alternatives on the scale of likeliness/expectedness, as in (22) (for a similar role of even in English even though clauses, see Lund 2017; Zhu 2019; cf. (2) above).9

- (22)

- Scalar presupposition (contributed by čak ‘even’)

- p ∧ q (= a1) <likely ¬p ∧ q (= a2)

- = It is raining ∧ Mara is running <likely It is not raining ∧ Mara is running

In the following subsections, we take a closer look at the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic properties of the three components involved in the composition of the conjunction iako.

3.1.1 The conjunction/particle i ‘and’

The particle/conjunction i has various uses in Serbian, all of which can be unified under the umbrella of additivity. As a plain conjunction, it marks additive coordination, that is, the second conjunct is added to the first one, forming a plural denotation of the same semantic type (Arsenijević 2011: 179; Čudomirović 2015: 53). According to Arsenijević (2011), the additive semantics of i can be seen as a relation which takes a particular dimension of the denotation of its first conjunct (e.g. temporal or spatial dimension, the scalar degree of some of their properties, etc.), and then adds to it the value along the same dimension for its second argument. This conjunction can coordinate both clauses (23) and noun phrases (24).

- (23)

- (Čudomirović 2015: 81, adjusted)

- Smireno

- calmy

- me

- I.acc.cl

- gleda

- watches

- i

- and

- ćuti.

- keeps_silent

- ‘He looks at me calmly and stays silent.’

- (24)

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- je

- aux

- kupio

- bought

- sendvič

- sandwich.acc

- i

- and

- salatu.

- salad.acc

- ‘Pera bought a sandwich and a salad.’

The coordinative construction typically involves a single i, preceding the last conjunct, as in (23–24), but i can also be repeated before each conjunct in the case of multiple coordination exemplified in (25). In the latter case, each of the conjuncts is given special emphasis. This use represents a borderline case between i as a proper conjunction and a focus particle.

- (25)

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- je

- aux

- kupio

- bought

- i

- and

- sendvič

- sandwich.acc

- i

- and

- salatu.

- salad.acc

- ‘Pera bought both a sandwich and a salad.’

According to Arsenijević (2011: 179), the use of i as a focus particle comes from the focalization of the conjunction i together with the last conjunct, e.g. salata ‘salad’ in (25) above and (26), where the first conjunct is presupposed (cf. also Gajić 2019).

- (26)

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- je

- aux

- kupio

- bought

- i

- and

- salatu.

- salad.acc

- ‘Pera bought a salad, too.’

It has been argued that i as a focus particle can have either an additive (as in (26)) or scalar contribution (27) to the meaning of the sentence (cf. Arsenijević 2011; 2021; Gajić 2019). Arsenijević (2011: 182; 2021: 25) describes the scalar use of i in terms of the domain widening effect (cf. Chierchia 2006), i.e., it expands the reference domain. This is illustrated in (27), where the domain is extended to include the circumstances least expected (which is implicated by the superlative najteži ‘the hardest’).

- (27)

- (Arsenijević 2011, adjusted)

- Jovan

- Jovan.nom

- rešava

- solves

- i

- and

- najteže

- hardest

- probleme.

- problems.acc

- ‘Jovan solves even the most difficult problems.’

According to Arsenijević, this is the same effect that i has in pronominals such as i-ko (and-who) ‘anyone’, i-kad (and-when) ‘any time’, i-gde (and-where) ‘any place’, where, too, it has the domain widening effect (Arsenijević 2021: 26; cf. Grickat 1953 for a similar view). For instance, in (28), the morpheme i in i-koga ‘anyone’ expands the domain of the seen individuals also with the ones least expected to be seen (Arsenijević 2021).

- (28)

- (Arsenijević 2021, adjusted)

- Da

- comp

- li

- q

- si

- aux

- video

- saw

- i-koga?

- and-whom

- ‘Have you seen anyone?’

Arsenijević (2011) emphasizes the role of contextual triggers for the emergence of a scalar reading of i. Similarly, Gajić (2019: 440) proposes that the flip from the additive to the scalar contribution is made once the set of focus alternatives becomes ordered on a likelihood scale due to the context, the information structure, the presence of the focus particle čak, etc., as in (29) (cf. also Grickat 1953: 218). In Gajić’s (2019: 440–441) view, the use of čak to mark a scalar interpretation like (29b) is possible, but not necessary: this particle is needed when the constituent that i is attached to is topicalized.

- (29)

- (Gajić 2019, adjusted)

- a.

- (Čak)

- even

- i

- and

- domaći

- homework.acc

- je

- aux

- uradila.

- did

- ‘She even did the homework.’

- b.

- ‘She fed the dog’ < ‘She washed the dishes’ < ‘She did the homework’.

However, the fact that the ‘scalar’ i needs contextual support, a special information structure, or an explicit focus particle like čak ‘even’ indicates that i is never actually a scalar focus particle by itself, but that this contribution is either brought about by a (c)overt focus operator matching the meaning of čak ‘even’ or triggered contextually, as a conversational implicature (see also §3.1.2). We thus maintain that i itself contributes only additivity. Otherwise, one needs to assume that in examples like (29) both i and čak have the same contribution, which is an uneconomical outcome – especially if the division of labor between the two particles can be independently motivated (cf. §3.1.3), as additionally supported by our analysis of iako-concessives (cf. §3.1.2–§3.1.3).

3.1.2 The relativizer ako ‘if’

Let us now move to the discussion of the relativizer ako ‘if’. This relativizer is most typically used with conditional clauses, as illustrated in (30). With Arsenijević (2021), we assume that in conditional clauses, the TS of the main clause is a free variable, and thus generically interpreted, while the subordinate clause is a restrictive clause that modifies the generic TS of the matrix clause.

- (30)

- Ako

- if

- ne

- not

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘If it doesn’t rain, Pera runs.’

Given that expressions that share the same marking – in the case at hand ako ‘if’ in both conditionals and concessives – are generally expected to have common semantic properties, this calls for accounting for the common core in ako-conditionals and iako-concessives. The parallel is even more striking in the so-called concessive conditionals (cf. König 1992; Haspelmath & König 1998), illustrated in (31) from Serbian, which share some properties with conditionals, and others with concessives; for comparison, let us consider a ‘similar’ concessive in (32).

- (31)

- I

- and

- ako

- if

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Even if it rains, Pera runs.’

- [Two conditions, as a result of an additive presupposition:

- => If it does not rain, Pera runs.

- + If it rains, Pera runs.]

- (32)

- [Background: Pera usually runs when it’s not raining.]

- I-ako

- and-if

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Even though it is raining, Pera is running.’

- [Ranking of two conditions, resulting from additive + scalar presuppositions:

- It is less likely that Pera runs if it rains than that Pera runs if it doesn’t rain.]

In Serbian, concessive conditionals are usually described as formed by attaching the additive i ‘and’ to a conditional clause (Milošević 1986; Silić & Pranjković 2005; Zvekić Dušanović 2007; Kovačević 2009).10 The additive i (cf. §3.1.1) marks that the condition introduced by the subordinator ako is added to the previous one (available from our background knowledge or the context), with an implicature that the introduced condition is an extreme case for the conditional relationship. This extremeness follows as a conversational implicature, since in some more neutral contexts, it may not arise. Observe example (33). The conjunction i here plainly states that there are some other situations apart from being spring in which Pera runs (those additional alternatives may also be asserted, by an indefinite number of repetitions of clauses preceded by the conjunction i, as indicated in the brackets). Only if the alternatives added by i contradict our world knowledge, the pragmatic effect of unexpectedness (or ‘extreme’ case) arises. On the other hand, the iako-counterpart, as in (34), must accommodate a scalar presupposition for a sentence to make sense: it must be clear from the background that for some reason it is less likely that Pera runs in the spring than that he runs if it is not spring.

- (33)

- I

- and

- ako

- if

- je

- cop

- proleće,

- spring.nom

- (i

- and

- ako

- if

- je

- cop

- zima,

- winter.nom

- i

- and

- ako

- if

- je

- cop

- leto,

- summer.nom

- …),

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘If it is spring, (if it is a winter, if it is a summer, …), Pera runs.’

- (34)

- [Background: In spring, when everything blooms, Pera is troubled by numerous allergies. That’s why he doesn’t like to run during spring, although running is his hobby.]

- I-ako

- and-if

- je

- cop

- proleće,

- spring.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Even though it is spring, Pera is running.’

Let us now focus on the differences and similarities between concessive conditionals and ‘proper’ concessives, as illustrated in (31) vs. (32). One difference pertains to the overarching contrast between standard conditionals and concessive constructions: in the former case, the ako-clause modifies the matrix clause that is interpreted generically, whereas in the latter case, the subordinate clause is interpreted referentially (referring to the actual situation). More importantly, where the two types intersect, there is one important similarity and one important difference at the same time. As for the similarity, both types include (via assertion plus presuppositions) the relation between the two conditional alternatives (say, a1 and a2) – as indicated in square brackets in (31) vs. (32), and repeated for convenience in Table 4.11 The difference that can be read from the table is that concessives include a scalar presupposition that a1 is less likely than a2, while scalarity can (but doesn’t have to!) arise as a conversational implicature in the case of concessive conditionals (as also supported by contexts like (33) and (34)).

Concessive conditionals, concessives and scalarity.

| Conditions/implications | Concessive conditionals | Concessives |

|

a1: p –> q If it rains, Pera runs. a2: ¬p –> q If it doesn’t rain, Pera runs. |

Additivity: a1+a2 Scalarity via implicature: a1 is less likely than a2 |

Additivity: a1+a2 Scalarity as a presupposition: a1 is less likely than a2 |

We propose that the difference in the availability of a scalar presupposition follows from the fact that iako-clauses with standard concessives obligatorily include a covert čak ‘even’, which brings us to our final component, to be discussed in the next subsection.

3.1.3 The (c)overt čak ‘even’

Informally, the contribution of the English particle even, whose closest match in Serbian is the particle čak (or particles čak+i jointly), is that the focused expression is less likely and/or less expected than some presupposed alternative (see Horn 1969; 1992; Lycan 1991; Krifka 1992; Guerzoni & Lim 2007; Crnič 2011a; b; 2013; Panizza & Sudo 2020, for various formal implementations of this basic idea, and Greenberg 2022 for a fresh look at the state of the art). Whether even in English only adds a scalar presupposition (the ranking on the scale of likelihood/expectedness) or also adds an additive presupposition, is still debatable (see Guerzoni & Lim 2007; Greenberg 2016 and references therein). Crucial for our purposes is that the scalar presupposition of the type illustrated in (3) above is not questionable.

We propose that the particle čak ‘even’ in Serbian contributes the scalar presupposition (as also hinted in Gajić 2019), whereas the additive presupposition is provided either by the particle i ‘and’ or in some other ways, e.g. when it is easily retrieved from the context. Such a division of labor is supported by the following facts. First, čak most frequently appears together with i, as in (35). Namely, out of 300 randomly extracted examples from srWaC with the focus particle čak, as many as 151 examples are a combination čak + (n)i.12

- (35)

- [Milan usually avoids parties.]

- Čak

- even

- je

- aux

- i

- and

- Milan

- Milan.nom

- došao

- came

- na

- on

- žurku.

- party.acc

- ‘Even Milan came to the party.’

- [Milan was considerably less likely to attend the party compared to others.]

Second, in cases where čak is used without i, the scalar ranking includes the entity in the denotation of the item in the scope of čak and the standard value along the same dimension – rather than comparing an asserted and a presupposed alternative. For instance, in (36), čak indicates that the number of Wimbledon titles that Federer won is estimated by the speaker as exceeding the standard. Similarly, in (37), China as a destination is marked as higher on the ‘distance’ scale in comparison to other destinations (from the perspective of Serbia as the starting point).

- (36)

- Federer

- Federer.nom

- je

- aux

- osvojio

- won

- čak

- even

- 8

- 8

- Vimbldona.

- Wimbledon.gen

- ‘Federer won as many as 8 Wimbledon titles.’

- (37)

- [Uttering from Serbia]

- Čak

- even

- u

- in

- Kinu

- China.acc

- je

- aux

- otputovao.

- traveled

- ‘He traveled all the way to China’.

Importantly, the particle čak is not interchangeable with the particle i in examples like (36) and (37): when i is used instead of čak, it gets an additive interpretation (under the neutral intonation), as in (38) and (39).

- (38)

- Federer

- Federer.nom

- je

- aux

- osvojio

- won

- i

- and

- 8

- 8

- Vimbldona.

- Wimbledon.gen

- ‘Federer won 8 Wimbledons as well.’

- [In addition to other titles.]

- (39)

- [Uttering from Serbia]

- I

- and

- u

- in

- Kinu

- China.acc

- je

- aux

- otputovao.

- traveled

- ‘He traveled to China as well.’

- [In addition to other destinations.]

These data clearly indicate the division of labor between the two particles in Serbian: čak adds a scalar presupposition, while i introduces an additive presupposition.

We can now return to concessive conditionals and concessives that can combine with čak. While both concessive conditionals and standard iako-concessives can be used with the particle čak, as in (40) and (41), respectively, we argue that in the former case, a scalar presupposition is not present without čak, while in the latter case, čak is a mere overt realization of an underlyingly always present scalar particle, which is responsible for a scalar presupposition. Specifically, in (40), without čak, there is no scalar presupposition that it is less likely that Pera runs if it is spring than that he runs if it is not spring (as shown w.r.t. (33) above). By contrast, with čak, this meaning component is accommodated as a scalar presupposition. On the other hand, in (41), there is a scalar presupposition that it is less likely that Pera runs if it is spring than that he runs if it is not spring – irrespective of the (overt) presence of the particle čak.

- (40)

- Čak

- even

- i

- and

- ako

- if

- je

- cop

- proleće,

- spring.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Even if it is spring, Pera runs.’

- (41)

- [Background: In spring, when everything blooms, Pera is troubled by numerous allergies. That’s why he doesn’t like to run during spring, although running is his hobby.]

- Čak

- even

- i-ako

- and-if

- je

- cop

- proleće,

- spring.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Even though it is spring, Pera is running.’

As pointed out in §1, a related proposal for English concessives has been pursued in Lund (2017) for English sentences in (42), repeated from (2). Lund proposes that the two sentences in (42) have the same meaning, and after having argued that even in (42a) contributes a scalar presupposition, this author concludes that the alternative without even actually contains a covert even – as it conveys the same meaning, and the two items (though and even though) are interchangeable.

- (42)

- [from Lund 2017]

- a.

- Even though it’s raining, John went for a walk.

- b.

- Though it’s raining, John went for a walk.

Additional support for the covert even-like operator comes from Panizza & Sudo (2020)’s account of the same truth conditions with and without even in contexts like (43), under the so-called minimal sufficiency reading (after Grosz 2012), which “seems to affirm, rather than negate, focus alternatives”.

- (43)

- (Even) just onefocus cat will make Patrick happy.

According to Panizza & Sudo (2020: 2), in examples of minimal sufficiency readings, “the relevant inference is intuitively scalar and additive: Roughly, the prejacent describes a relatively unlikely/surprising case for some event to happen or some state to hold, and the sentence also suggests that some other focus alternatives that are more likely/less surprising are also true.” As these authors explain, (43) indicates that Patrick’s happiness is contingent upon the presence of one single cat. The scalar component of its meaning suggests that Patrick’s happiness with precisely one cat is relatively unexpected or unlikely. Moreover, the additive facet of the meaning implies that Patrick’s happiness would also result from the presence of multiple cats. The parallel with concessives is striking, since at least those concessives composed with (c)overt even can be conceived as displaying ‘minimal sufficiency readings’ in the sense of Grosz (2012) and Panizza & Sudo (2020): they include a scalar ranking in terms of unlikeliness (contributed by čak ‘even’), as well as an additive component (contributed by i ‘and’, or contextually).

Finally, since (covert) čak ‘even’ is responsible for a scalar presupposition in standard concessives with the conjunction iako, its overt realization is semantically ill-formed in contexts that do not include scalar presuppositions, e.g. with rectifying concessives, as in (44), repeated from (6).13

- (44)

- Ućutao

- fell_silent

- je,

- aux

- (*čak)

- even

- iako

- although

- to

- that.dem

- ćutanje

- silence.nom

- nije

- aux.neg

- dugo

- long

- potrajalo.

- lasted

- ‘He fell silent, although the silence did not last long.’

A covert čak in standard concessives also accounts for the fact that no other focus particles, such as jedino ‘only’ or samo ‘just’, can be used with iako-clauses, as in (45), repeated from (5).

- (45)

- (*Jedino)

- only

- /

- (*samo)

- just

- /

- čak

- even

- iako

- although

- nije

- cop.neg

- gladna,

- hungry

- jede.

- eats

- ‘(*Only) / (*just) / even though she is not hungry, she is eating.’

Namely, the particles čak ‘even’ and jedino ‘only’ exhibit complementary distribution in Serbian. This is because, similar to their English counterparts, they function as antonyms (cf. Greenberg 2022).14 Example (46) shows that čak and jedino are also incompatible beyond concessives when targeting the same constituent: jedino selects one alternative from the available set (Wimbledon, but not other possible tournaments), while čak (in this case, combined with i ‘and’) ranks winning Wimbledon as surpassing the standard expectations (in comparison to other tournaments).

- (46)

- Osvojio

- won

- je

- aux

- jedino

- only

- /

- čak

- even

- i

- and

- (*jedino+čak

- only+even

- /

- *čak+jedino)

- even+only

- Vimbldon.

- Wimbledon

- ‘He won only / even (*only+even / *even+only) Wimbledon.’

As for the particle samo ‘only’, it can be combined with čak only when they target different constituents. For instance, the two particles co-occur under the minimal sufficiency reading in (47), which is possible because samo has scope over the noun phrase (i) jedan cvet, whereas čak scopes over the entire clause, indicating the unexpectedness of the fact that just one flower is sufficient to make happy the girlfriend; this is schematically marked by brackets (cf. Panizza & Sudo 2020 for similar argumentation regarding their English equivalents).

- (47)

- Čak

- even

- [[samo

- just

- [(i)

- and

- jedan

- one

- cvet]]

- flower.nom

- bi

- would

- obradovao

- made_happy

- moju

- my

- devojku.]

- girlfriend.acc

- ‘Even just one flower would make my girlfriend happy.’

When čak and samo target the same constituent, as in (48), they are mutually excluded, because they have the opposite effects: samo indicates that the value on the relevant scale is lower than the standard, whereas čak indicates the opposite: that the relevant value exceeds the standard.

- (48)

- Federer

- Federer.nom

- je

- aux

- osvojio

- won

- čak

- even

- /

- samo

- just

- (*čak+samo

- even+just

- / *samo+čak)

- just+even

- 8

- 8

- Vimbldona.

- Wimbledon.

- ‘Federer won as many as / just 8 Wimbledons.’

We propose that the ungrammaticality of samo with iako-clauses is regulated by the same mechanism: its meaning is incompatible with the meaning of (covert) čak because both of them would have the same target – the alternatives activated by i, leading to the opposing effects on ranking alternatives within the relevant scale.

In the next two subsections (§3.2–§3.3), we show how our proposal accounts for the impossibility of combining čak with the conjunctions mada and premda. Before that, one important issue remains to be addressed: If covert even-like particles in English and Serbian have the same contribution as otherwise widely employed overt particles (even and čak, respectively), what licenses the distribution of two ‘realizations’ of the same underlying item? In the case of Serbian concessives, the overt realization of čak is also by far less frequent than the covert alternative, as we have seen in §2.2. While this topic deserves an exploration of its own, for the purposes of this paper, we contend that the two types of realizations have different pragmatic effects. The overt form (explicated čak) produces more emphasis/intensification – in accordance with Levinson’s (2000) M-principle. This principle is founded on the correlation between the marked form and the marked meaning – where the marked form implies the marked meaning.

3.2 Mada: ma(kar) ‘at least, even’ + da (comp)

In this section, we propose that the concessive conjunction mada can be decomposed into the scalar particle ma(kar) ‘at least, even’ and the subordinator/relativizer da, as suggested also in Arsenijević (2021: 26–27). The incompatibility with the particle čak ‘even’ follows, on this view, from the fact that only one scalar particle is possible at the same time targeting the same position. This is corroborated by the fact that the combination of the particles čak and makar is banned across the board in Serbian, i.e. also beyond concessive constructions. The relativizer da, just like ako in i-ako, introduces a proposition of the concessive relative clause and links it to the one of the main clause. The referential properties of standard mada-concessives are dependent on those of the matrix clause: mada-clauses refer to a definite/specific TS due to their coreference with a definite/specific TS of the main clause – just like in the case of iako-concessives (cf. §3.1; see §4 for a more detailed syntactic account of concessives). The difference between ako and da boils down to ako having a conditional ‘flavor’, while da is more neutral, probably the most neutral relativizer, as briefly illustrated in §3.2.2 (see also Todorović 2015; Arsenijević 2020).

We introduce these two components – ma(kar) and da – in the following two subsections.

3.2.1 The particle ma(kar) ‘at least, even’

An argument for treating ma(kar)15 as a scalar particle comes from contexts like (49–55), where it has a domain-widening effect (Arsenijević 2021: 26–27), which is traditionally conceived as a kind of concessive meaning (Grickat 1953). It can be combined with indefinite/non-specific pronouns, as in (49–50), with clauses, traditionally also described as concessive ones (Grickat 1953), as in (51–53), but also with a range of other expressions, e.g. NPs, quantifiers, etc., as in (54–55).

- (49)

- (Arsenijević 2021: 27, adjusted)

- Nije

- cop.neg

- ona

- she.nom

- ma(kar)

- at_least

- ko.

- who.nom

- ‘She isn’t just anyone.’

- (50)

- (Grickat 1953: 227, adjusted)

- Ma

- part

- od

- from

- koga

- whom.gen

- da

- comp

- primiš

- receive.2sg

- poklon,

- gift.acc

- treba

- should

- da

- comp

- se

- refl

- zahvališ.

- thank.2sg

- ‘No matter who you receive a gift from, you should thank them.’

- (51)

- (Grickat 1953: 218, adjusted)

- Sve

- all

- životinjske

- animal

- vrste,

- kinds

- ma(kar)

- at_least

- to

- that.dem.nom

- bile

- were

- i

- and

- najniže,

- the_lowest

- imaju

- have.3pl

- osećaj

- feeling.acc

- dodira.

- touch.gen

- ‘All animal species, even the lowest ones, have a sense of touch.’

- (52)

- Ma(kar)

- at_least

- da

- comp

- je

- cop

- i

- and

- najružniji

- most_ugliest

- na

- on

- svetu,

- world.loc

- meni

- I.dat

- se

- refl

- sviđa.

- likes

- ‘Even if he is indeed the ugliest in the world, I like him.’

- (53)

- (Arsenijević 2021: 27, adjusted)

- Poješću

- eat.fut.1sg

- ga

- it.acc.cl

- ma(kar)

- at_least

- me

- I.acc.cl

- ubilo.

- killed

- ‘I’ll eat it even if it killed me.’

- (54)

- Uradi

- do.imp.2sg

- makar

- at_least

- najlakši

- the_easiest

- zadatak!

- task.acc

- ‘Do at least the easiest task!’

- (55)

- Taj

- that

- zadatak

- task.nom

- se

- refl

- može

- can.3sg

- rešiti

- solve.inf

- na

- on

- makar

- at_least

- dva

- two

- načina.

- ways

- ‘That problem can be solved in at least two ways.’

In all the examples above, ma(kar) adds a presupposition that the referents or propositions are at the periphery, i.e. the least expected ones on the relevant pragmatic scale (cf. also Crnič 2011c for magari in Slovenian). Putting aside examples with indefinite/non-specific pronouns, ma(kar) corresponds either to English even, in downward entailing environments (51–53), or to at least (54–55), in modal contexts such as imperatives or the modal verb moći ‘can’. In this respect, ma(kar) resembles concessive scalar particles in other languages (e.g. magari in Slovenian, Crnič 2011c; siquiera in Spanish, Alonso-Ovalle & Heredia Murillo 2023), and can be analyzed as spelling out two focus-sensitive operators (even and at least), as proposed in Crnič (2011c) for concessive scalar particles.16 If this analysis is correct, it offers an explanation for the incompatibility of the particles čak and ma(kar) in Serbian – as both include an even-like component.17

The particle ma in Serbian is also used as an emphatic discourse particle indicating that the speaker’s presuppositions are at odds with the actual state of affairs (Ivić 2005), with different nuances illustrated in (56–60). We take this use of ma to be essentially the same as the typical scalar use illustrated above, but at the speech act (instead of propositional) level.

- (56)

- (Ivić 2005: 90, adjusted)

- [Emphatic refutation of the presented information about a given factual situation]

- A:

- Jovan

- Jovan.nom

- nije

- aux.neg

- otišao.

- left

- ‘Jovan didn’t leave’

- B:

- Ma

- part

- jeste!

- aux

- ‘He did!’

- (57)

- (Ivić 2005: 91, adjusted)

- [Emphatically expressed disagreement with what was just said]

- Ma

- part

- šta

- what.acc

- to

- that.acc

- govoriš?!

- speak.2sg

- ‘What are you saying?!’

- (58)

- (Ivić 2005: 90, adjusted)

- [Emphatic disobedience]

- A:

- Ti

- you.nom

- ćeš

- will

- otići

- leave.inf

- da

- comp

- kupiš

- buy.2sg

- karte.

- tickets.acc

- ‘You will go buy tickets.’

- B:

- Ma

- part

- nemoj!

- don’t

- A

- and

- ti

- you.nom

- da

- comp

- sediš.

- sit.2sg

- ‘You do not say! And you are going to sit.’

- (59)

- (Ivić 2005: 91, adjusted)

- [Questioning]

- Ma

- part

- gde

- where

- ja

- I.nom

- sad

- now

- da

- comp

- idem

- go.1sg

- po

- over

- toj

- that

- vrućini?

- heat.loc

- ‘Where should I go in this heat?’

- (60)

- (Ivić 2005: 91, adjusted)

- [Surprise + disbelief]

- Ma

- part

- je

- aux

- li

- q

- ono

- that

- tamo

- there

- Marko?

- Marko.nom

- ‘Is that Marko over there?’

The connection between the particle ma in examples like (56–60) with the conjunction mada is particularly prominent in rectifying uses of mada, since in such uses mada-clauses introduce exceptions from expectations triggered by the proposition of the main clause. This is clear from examples in (61–62).

- (61)

- Ona

- she

- je

- cop

- dobra

- good

- majka,

- mother.nom

- mada

- although

- ponekad

- sometimes

- ume

- knows

- da

- comp

- bude

- be

- previše

- overmuch

- stroga

- strict

- prema

- toward

- svom

- refl.poss

- potomstvu.

- offspring.loc

- ‘She is a good mother, although sometimes she can be too much severe with her offspring.’ (srWaC)

- (62)

- U

- in

- kojim

- which

- situacijama

- situations.loc

- najsočnije

- juiciest

- psujete?

- curse.2pl

- –

- Najčešće

- most_often

- u

- in

- šalterskim

- administrative

- situacijama

- situations.loc

- u

- in

- Srbiji,

- Serbia.loc

- koje

- which.nom

- gotovo

- almost

- uvek

- always

- podrazumevaju

- involve.3pl

- ozbiljno

- serious

- poniženje.

- humilitation.acc

- Ipak,

- however

- češće

- more_often

- psujem

- curse.1sg

- u

- in

- sebi…

- refl.loc

- mada

- although

- mi

- I.dat.cl

- se

- refl

- omakne

- slips

- i

- and

- naglas.

- loud

- ‘In what situations do you curse the most? – Most often in administrative situations in

- Serbia, which almost always involve serious humiliation. However, more often than not I curse silently… although I also do curse out loud.’ (srWaC)

A very tight link between the conjunction mada and the particle ma is even more evident from examples like (63), where mada operates at the discourse level – it is used as a true discourse particle rather than as a concessive conjunction. Crucially, similarly to the particle ma, it expresses the speaker’s stance toward the preceding statement, signifying that the information it introduces is the least expected, given the prior flow of the discourse.

- (63)

- Hodali

- walked

- smo

- aux

- po

- over

- suncu

- sun.loc

- i

- and

- sasvim

- totally

- neobavezno

- facultative

- pričali.

- talked

- Ne,

- no

- nismo

- aux.neg

- pričali

- talked

- o

- about

- Bogu.

- God.loc

- Mada…

- although

- Setila

- remembered

- sam

- aux

- se

- refl

- nečega

- something.gen

- što

- comp

- mi

- I.dat.cl

- je

- aux

- Fon

- Fon

- Hauzburg

- Hausburg.nom

- rekao

- told

- kasnije,

- later

- jednom

- once

- drugom

- second

- prilikom.

- occasion.ins

- Rekao

- told

- je:

- aux

- – O

- about

- Bogu

- God.loc

- nema

- has_not

- šta

- what.acc

- da

- comp

- se

- refl

- kaže.

- says

- ‘We walked in the sun and talked casually. No, we did not talk about God. Although… I remembered something von Hauzburg told me later, on another occasion. He said: – There is nothing to say about God.’ (CCS)

Importantly, the conjunction mada implies the involvement of the speaker in standard concessives as well, i.e. the speaker is a perspectivizing center – in contrast with the conjunction iako, which is neutral in this regard. For instance, in (64), it is strongly implied that the proposition introduced by mada takes the speaker’s perspective, rather than the one of the subject of the matrix clause (Ignjat). If iako were used instead of mada in this example, it would be fully compatible with the respective subject’s perspective, e.g. it would be plausible that Ignjat acts as a perspectivizer/Judge.

- (64)

- Poslovođa

- manager.nom

- Ignjat

- Ignjat.nom

- je

- aux

- čistio

- cleaned

- pred

- in_front_of

- radnjom,

- shop.ins

- mada

- although

- nije

- aux

- imalo

- had

- šta

- what.nom

- da

- comp

- se

- refl

- čisti.

- cleans

- ‘Manager Ignjat was cleaning in front of the shop, although there was nothing to clean.’ (CCS)

Judging by our preliminary data (which still has to be subjected to more detailed quantitative research), the degree of involvement of the speaker’s perspective is what distinguishes between iako- and mada-standard-concessives across the board. Compare, in that sense, the minimal pair of sentences in (65), which differ only in the choice of the conjunction. The two sentences have the same truth-conditional meaning, and in both cases, there is a scalar ranking characteristic of standard concessives: {It is raining & Pera is running} is less likely/expected than {It is not raining & Pera is running}. The only difference that emerges, at least for the speakers that we consulted, is that this likeliness is obligatorily from the speaker’s perspective in the case of mada, while in the case of iako it can be from the perspective of either the speaker or the matrix subject (which indicates that iako is neutral in this regard).

- (65)

- a.

- I-ako

- and-if

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Although it’s raining, Pera is running.’

- b.

- Ma-da

- at_least-comp

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Although it’s raining, Pera is running.’

3.2.2 The relativizer da

The subordinator/relativizer da has a vast array of uses in Serbian, encompassing both subjunctive and indicative contexts (cf. Todorović 2015; Arsenijević 2020). In subjunctive contexts, it can, for instance, introduce counterfactuals, as in (66), complements to modal verbs (67), or purpose clauses (also (67)).

- (66)

- Da

- comp

- imam

- have.1sg

- para,

- money.gen

- ne

- not

- znam

- know.1sg

- šta

- what

- bih

- would

- radila

- worked

- sa

- with

- njima.

- them.ins

- ‘If I had money, I don’t know what I would do with it.’

- (67)

- Moram

- must.1sg

- da

- comp

- požurim

- hurry.1sg

- da

- comp

- bih

- would

- stigao

- arrived

- na

- on

- taksi.

- taxi.acc

- ‘I have to hurry up to catch up the taxi.’

Finite complement clauses with verbs of speaking or speech act verbs are yet another typical type of clause headed by da, as illustrated in (68); see Arsenijević (2009b) for an analysis of these clauses as relative clauses, modifying a (covert) nominal head from the main clause (cf. also §4).

- (68)

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- je

- aux

- rekao

- said

- /

- tvrdio

- claimed

- da

- comp

- pada

- falls

- kiša.

- rain.nom

- ‘Pera said/claimed that it was raining.’

Da-complements (like their English that-counterparts) do not generally contribute to the truth value of the proposition of the main clause. However, as noted in Hinzen (2007) and Arsenijević (2009b; 2021), there are contexts in which they indirectly affect the truth value of the proposition of the main clause, such as (69–70). In (69), the complement clause (together with its head, which can be lexicalized by the demonstrative to ‘that’) affects the truth value of the main clause because it actually acts as its propositional subject, asserted to be true. In (70), the da-clause modifies a pronominal head (again lexicalized by to ‘that’), and the entire construction is used as a complement of the evidential verb sećati se ‘remember’ – by virtue of which it contributes to the overall truth condition of the main clause.

- (69)

- (Inspired by a similar English example in Arsenijević 2009b)

- Tačno

- true

- je

- aux

- (to)

- that

- da

- comp

- je

- aux

- Meri

- Merry.nom

- ubila

- killed

- Džona.

- John.acc

- ‘It is true that Merry killed John.’

- (70)

- (Arsenijević 2021: 27, adjusted)

- Sećam

- remember.1sg

- se

- refl

- (toga)

- that.gen

- da

- comp

- si

- aux

- dolazio.

- came

- ‘I remember that you came.’

Let us now see how the described behavior of da can be linked to da from concessives (as part of ma-da). In his analysis of concessives, Arsenijević (2021) notes that the assertion about the actual situation is not incompatible with da in Serbian (based on examples like (70)), but he still concludes that it being a part of the concessive conjunction is unexpected: da predominantly introduces subjunctive clauses, thus clashing with the referential properties of mada-concessives, which in his analysis are assertionas about definite/specific situations. However, once we assume that the referential status of mada-clauses, similarly to iako-clauses (see §3.1), is determined via the coreference of their TS with a definite/specific TS of the matrix clause, the role of da is the same in concessives and all other contexts: it introduces a relative clause that is referentially underspecified. Since the antecedent of its relativization site (TS) is definite/specific, targeting the actual situation, the proposition introduced by da is evaluated against the actual situation too (see §4 for more details). This is reminiscent of the referential uses of complement da-clauses in constructions like (69–70) discussed above: in all these cases, the referential status of da-clauses depends on the coreference with some element in the matrix clause.

Finally, note that da, apart from introducing subordinate clauses, can also introduce yes-no questions, as in (71).

- (71)

- Da

- comp

- li

- q

- dolaziš?

- come.2sg

- ‘Are you coming?’

The connection between da in subordinate clauses and questions is straightforward once the subordinator da is analyzed as a relative pronoun (cf. §4). Namely, cross-linguistically, items introducing relative clauses often serve as question markers too – the most typical example being wh-words in English and their counterparts in other languages. Arsenijević (2009b: 47) proposes that the same holds for da: it introduces subordinate clauses reanalyzed as relative clauses, but also questions, in this case – yes-no questions.18

3.3 Premda: prem ‘opposite’ + da (comp)

In this subsection, we turn to the question of why the particle čak ‘even’ is not possible with premda-concessives. We propose that prem-da consists of the scalar contrastive particle prem that marks a parallel and/or opposite relation between two entities, while da is a relativizer, just as in the case of ma-da. Since premda-concessives (like iako- and mada-concessives) already contain a scalar particle – in this case the contrastive particle prem – čak is infelicitous with them for the same reason it cannot be combined with mada-concessives: the two particles, čak and prem, are in complementary distribution. The role of da has already been presented in the previous subsection, which is why we focus here on the role of prem and its overall contribution to the distribution of premda-concessives.

That prem marks some kind of parallel and/or opposite relation can be seen from examples like (72–73), where it is used as an independent word: prem-a ‘opposite’.19

- (72)

- Rezultat

- result.nom

- utakmice

- match.gen

- je

- cop

- jedan

- one

- prema

- opposite

- jedan.

- one

- ‘The result of the match is 1:1.’

- (73)

- Kuća

- house.nom

- je

- cop

- okrenuta

- turned

- prema

- opposite

- zgradi.

- building.loc

- ‘The house faces the building.’

The contrastive contribution of prem can be clearly traced in premda-concessives. As shown in §2.2, premda-concessives are predominantly used to describe a parallel relation between two propositions. This role of premda is particularly evident in rhetorical concessives (recall from §2.2 that premda-concessives are the most frequent among rhetorics), as in (19), repeated as (74), and rectifying concessives, illustrated in (75–76). As for the former, two propositions with ‘equal strength’ are contrasted, while in rectifying contexts, the proposition introduced by the main clause is rectified by introducing its antithesis. In (76), the relation between the two propositions is almost pure contrast, i.e. the ‘concessive flavor’ is completely bleached.

- (74)

- Najgori

- worst

- je

- cop

- đak

- student.nom

- po

- by

- učenju,

- learning.loc

- premda

- although

- najbolji

- best

- po

- by

- vladanju.

- governance.loc

- ‘He is the worst student in terms of learning, although he is the best when it comes to behavior.’ (CCS)

- (75)

- Poezija

- poetry.nom

- je

- cop

- sva

- totally

- usmerena

- directed

- na

- on

- to

- that.dem.acc

- da

- comp

- zabavi,

- entertains

- premda

- although

- ona

- she.nom

- i

- and

- koristi.

- benefits

- ‘Poetry is all aimed at entertaining, although it also benefits.’ (CCS)

- (76)

- Predeo

- landscape.nom

- oko

- around

- njih

- them.loc

- postajao

- become

- je

- aux

- go

- naked

- i

- and

- neplodan,

- barren

- premda

- although

- je

- aux

- nekad

- once

- davno,

- long_ago

- kako

- how

- im

- they.dat.cl

- je

- aux

- Torin

- Torin.nom

- rekao,

- told

- bio

- was

- zelen.

- green

- ‘The landscape around them was becoming barren, although once upon a time, as Torin told them, it had been green.’ (CCS)

While the contrastive nature of premda is most salient in rhetorical and rectifying uses of concessive clauses, its contrastive role also underlies all the complex sentences whose concessive clause is introduced by premda, including standard concessives. This is particularly clear if we compare sentences that only differ in the choice of conjunction. For this purpose, let us upgrade our example in (65) above by adding the same sentence with premda, as in (77).

- (77)

- a.

- I-ako

- and-if

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Although it’s raining, Pera is running.’

- b.

- Ma-da

- at_least-comp

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Although it’s raining, Pera is running.’

- c.

- Prem-da

- opposite-comp

- pada

- falls

- kiša,

- rain.nom

- Pera

- Pera.nom

- trči.

- runs

- ‘Although it’s raining, Pera is running.’

While, as discussed in §3.2, mada and iako differ in the degree of the speaker’s involvement (always present with mada, neutral with iako), both crucially rely on the scalar ranking in terms of expectedness/likeliness. The standard concessive introduced by premda is used when parallelism or contrast between the two propositions is intended, with the ‘concessive’ flavor emerging from the indicated contrast. As also pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, standard premda-concessives are similar to mada-concessives regarding the perspective holder: the perspective of the subject is excluded, and the propositions of the concessive and matrix clauses are evaluated by the speaker as epistemically dependent on each other. This epistemic dependency is expected under our proposal that the concessive does not bring about an independent assertion and that only the focus particle (but not the concessive itself) is merged in an epistemic projection, the point we immediately turn to in §4.

4 A note on the syntax of concessives

In this section, we point out some significant consequences for the syntactic analysis of standard concessives that follow from our analysis. Since we do not intend a full-fledged syntactic proposal, our analysis is necessarily sketchy, requiring additional technical elaboration. Standard concessives have recently been proposed to modify perspective-related projections EpistP/EvidP (Lund & Charnavel 2020),20 or Krifka’s (2023) JudgeP (Frey 2020). Frey (2020) proposes that standard concessives are themselves JudgePs. JudgeP in Krifka (2023) represents subjective epistemic and evidential attitudes of a Judge (the speaker by default), i.e. all the operators in JudgeP relate to the epistemic and evidential modifications of the proposition the speaker is committed to. As outlined in §3, Arsenijević (2021) analyzes concessives, like other subordinate clauses, as relative clauses (cf. Arsenijević 2006; 2009a; b). Our decompositional analysis in §3 has led us to suggest a novel approach to the syntax of concessives, which shares with the previous approaches (Frey 2020; Lund & Charnavel 2020; Arsenijević 2021) some important features, but also differs from them in some crucial aspects. For simplicity, we illustrate our approach with iako-concessives as the primary example.

Since we adopt Arsenijević’s relativization analysis of subordinate clauses, let us first provide a brief justification of this proposal. The rationale behind it is that all complex sentences can be analyzed as follows: the main clause contains a (pro)nominal element, i.e. antecedent, which is modified by a subordinate (relative) clause, whereas the relative clause contains an operator that can be lexicalized as a relativizer. If the antecedent is not overtly expressed, its meaning and/or pragmatic function can be easily retrieved (cf. Arsenijević 2006: 488). For instance, in typical complement clauses introduced by the subordinator/relativizer da in Serbian, it is possible to make the antecedent explicit by employing the demonstrative pronoun to ‘that’, especially when the complement clause is focalized, as in (78). This sentence has a typical relative-clause structure: it contains the antecedent to, and the relativizer da, where the subordinate relative da-clause modifies the pronomial to rather than complementing the matrix verb directly.

- (78)

- Jovan

- Jovan

- je

- aux

- rekao

- said

- to

- that.dem.acc

- da

- that

- Marija

- Marija

- ustaje

- gets_up

- rano.

- early

- ‘Jovan said that Marija gets up early.’

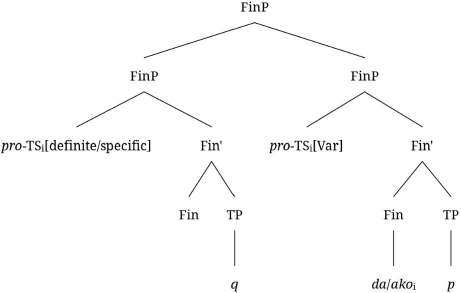

In the case of concessives, the relative clause itself is introduced by ako (in i-ako concessives) and da (in ma-da and prem-da concessives), which serve as relativizers over TSs (cf. Arsenijević 2021). For concreteness, we take that these relative clauses are hosted in Fin(iteness)P – a projection immediately dominating TP that hosts a TS pronoun (following Hinterhölzl 2019).21 They are adjoined to the FinP of the matrix clause, as depicted in (79). The relativizer takes two arguments: TP (hosting a proposition) as its complement, and proTS (a TS pronoun) as its specifier.22

- (79)

- Concessive relatives at FinP

Assuming with Klein (2006) that Fin0 of subordinate clauses is referentially defective, it follows that proTS cannot receive its value independently, by being directly anchored to the context.23 Under the relativization analysis, proTS is a variable that serves as a relativization site of a concessive relative and gets its value via the coreference with the definite/specific TS of the matrix clause; this is marked by co-indexation in (79). While both the TS of the matrix clause and the one of the relative clause are typically realized as pro (as in the tree above; see also Arsenijević 2021), the pronoun standing for the TS of the matrix clause can actually be lexicalized, as illustrated in (80).

- (80)

- [Looking through the window]

- Jel’

- q

- to

- that

- Marko

- Marko.nom

- trči,

- runs

- iako

- although

- (*to)

- that

- pada

- falls

- kiša?!

- rain.nom

- ‘Is that Marko running, although it’s raining?!’