1 Introduction

Emojis (often bare plural emoji (OED 2023a)) are a relatively new form of visual communication that exist currently as an option on most digital keyboards. They are symbols that depict objects, signs, ideas, and facial expressions. People from all backgrounds and in various languages use emojis in daily computer-mediated communication (CMC), and to varying degrees. Use of emojis is now so frequent that they can be seen in advertisements (Knudson 2017), in print (Evans 2017), on clothing (WOWPresents 2015), and even personified in film (Leondis 2017).

Emojis have been researched by computer scientists, psychologists, sociologists, and linguists (Bai et al. 2019). The majority of linguistic research on emojis has focused on the semantics. This research follows the recent trend of asking the questions how can extralinguistic information contribute to the information conveyed in language? and can nonlinguistic meaning be modeled with tools form formal semantics? This contributes to the growing body of literature on so-called super semantics (Schlenker 2019). Yet, emojis bring up a multitude of interesting linguistic questions. The sociolinguistic use of emojis has been documented (Moschini 2016), and some have asked whether or not emojis have a syntax (Cohn & Engelen & Schilperoord 2019).

The focus of this paper, however, is the morphosyntactic properties of emojis that appear as elements inside of sentences, exemplified by the following well-known sentence.1

- (1)

- I

NY

NY

This example may seem straightforward and relatively uninteresting, but there is a wealth of data from Twitter and other websites that show very interesting morphosyntactic properties of emojis that appear as grammatical elements. The data is confirmed by the judgments of language users who are proficient with emojis. From these data and their analysis I show that these grammatical emojis represent predictable and cohesive morphological units that can participate in morphosyntactic processes such as inflection, derivation, lexicalization, and grammaticalization. Following previous work that discusses the possibility of non-linguistic units functioning as lexical elements (Wiese 1996), I even raise the question of whether some of these emoji words are uniquely represented in language users’ lexicons as independent units.

The paper is structured as follows: in Section 2 I outline a brief history of emojis and their use. In Section 3 I describe three functions that emojis can have in a written utterance. In Section 4 I expand in detail upon the facts surrounding the distribution of emojis that appear within sentences instead of words in three languages: English (4.1.1.), German (4.1.2.), and Spanish (4.1.3.). I discuss data of these emojis taking inflectional (4.1.) and derivational (4.2.) affixes. I then discuss morphological regularization (4.3.) and summarize the findings (4.4.). In Section 5 I show that these emojis are sensitive to processes of morphosyntactic change such as lexicalization (5.1.) and grammaticalization (5.2.). In Section 6 I discuss a possible two-way classification of these emojis based on how they represent lexical elements. Section 7 concludes.

2 Some Background on Emojis

The first emoji-like elements (in-text ideographic pictures not composed of preexisting characters) emerged in Japan in the late 1990s to convey the meanings of facial expressions seen in manga (Danesi 2017). These symbols eventually evolved into what we know as emojis. The word emoji comes from Japanese 絵 e ‘picture’ and 文字 moji ‘character’, and was first introduced by emoji inventor Shigetaka Kurita in 1999 (Evans 2017). The resemblance this word bears to English emoticon is pure coincidence, as emoticon is a portmanteau of emotion and icon that is attested since the mid-1980s. The emoji keyboard was introduced for Apple digital keyboards on the iPhone in 2008 with iOS 2.2 and is now a standard feature on almost all smartphones, tablets, and computers (Evans 2017).

Using ideograms in writing to convey emotion is no new feature of written language, though. The first attested smiling face – or smiley – in a text is found in a financial record in the town of Trenčín, Slovakia next to the author’s signature (Ladislaides, 1635). The symbol was used identically to one of the ways in which contemporary emojis are used, to indicate the author’s positive feelings about the preceding text (Votruba 2018).

The first recorded use of the emoticons :-) and :-( in CMC, a predecessor to emojis that are still frequently used, occurred in 1982 in a computer forum (Fahlman 1982). Though some have proposed that the expressive symbol consisting of a colon followed by a closed parenthesis is attested since the seventeenth century (Stahl 2014), these instances are more than likely coincidental.

The original Apple emoji keyboard contained 471 emojis, but there are 4,084 at the time of writing this paper. Each emoji has its own Unicode entry, keywords, and a short name (“grinning face”, “squid”, “flag of Australia”, etc.), which I will be subsequently referring to as emoji’s name or label. The original was comprised of 32 smileys, a number of pictograms and ideograms depicting various animals, objects, and abstract symbols, as well as the flags of ten countries. The current emoji keyboard contains over 100 smileys, over 100 pictograms of humans and human body parts in six different skin colors, hundreds upon hundreds of miscellaneous pictograms and ideograms, flags for every country in the world, and flags for the gay and trans communities (Emojipedia). New emojis are added often.

3 Functions of Emojis in Sentences

Emojis have multiple possible configurations of where they can go in a sentence, and these positions correspond to different linguistic functions. In this section I identify three broad categories of where emojis can go. I borrow terminology from the domain of super linguistics and the body of research on the semantics of gestures (Schlenker 2018) to name the categories post-text emojis, emojis that follow an utterance (3.1.), co-text emojis, emojis that immediately follow and are directly associated with one specific word or constituent embedded in a sentence (3.2.), and pro-text emojis, which are emojis that are actually syntactically projected in the sentence, and will be the main focus of the morphological analysis of this paper (3.3.). These terms have been used before as they relate to emojis (Pierini 2021; Maier 2023).

3.1 Post-text emojis

The vast majority of the current literature on formal linguistics of emojis is about the semantics of sentences containing post-text emojis (Gawne & McCulloch 2019; Grosz & Kaiser & Pierini 2021; Pierini 2021; Pasternak & Tieu 2022; Maier 2023), in which the semantics of these emojis are often analyzes in the same way as the semantics of gestures that follow an utterance. Within post-text emojis, Grosz & Kaiser & Pierini (2021) distinguish between two types: face emojis (2–3) and activity emojis (4).

- (2)

- a.

- Did you see that guy?

(Grosz et al. 2022)

(Grosz et al. 2022)

- b.

- That fried chicken sandwich they make

- c.

- If a movie is violent, Alex hates it

These face emojis in (2) are expressive elements that provide information on the attitudes that the speaker feels toward the proposition in the text. For example, the “smiling face with heart-eyes” emoji in (2a) indicates that the speaker feels infatuation about the aforementioned guy. In (2c), the “worried face” emoji expresses the speaker’s negative emotions about Alex’s hatred of violent movies. The examples in (2) are all dependent, which means that the interpretation in the text influences the interpretation of the emoji since the emoji comments on the proposition of the text, and this is the focus of Grosz et al. (2022), but there are examples where the emoji is independent as it offers no comment on the speaker’s attitude toward the text. See these below.

- (3)

- a.

- How did the interview go?

(Grosz et al. 2022)

(Grosz et al. 2022)

- b.

- How are you coping?

These examples are the most clearly similar to gestures and facial expressions in terms of how their meaning contributes to the sentence. The activity emojis in (4), while also appearing after the sentence, serve a different function. For Grosz, Kaiser, & Pierini (2021) these are event descriptions.

- (4)

- a.

- Arsenal really impressed me !

(Grosz & Kaiser & Pierini 2021)

(Grosz & Kaiser & Pierini 2021)

- b.

- Getting ready for tomorrow!

- c.

- My job is pretty fun

Post-text emojis do not represent syntactic constituents, and it would be erroneous to suggest that they are projected in the syntax of the sentences they modify, just as no one suggests that post-speech gestures are projected syntactically. This is not to say, however, that no emojis can be represented in the syntax of a written utterance.

3.2 Co-text emojis

There are also co-text emojis, where emojis directly follow (often without spacing) a word or phrase that they modify.

- (5)

- I can build a house

rebuild a car

rebuild a car  and dig your grave!!!

and dig your grave!!!

- (6)

- Breathe on me while I sleep

tonight Lord!

tonight Lord!

- (7)

- Trans

people are human!!

people are human!!

- (8)

- drink

like Peter // hate like Stewie

like Peter // hate like Stewie  // be fly

// be fly  like Quagmire

like Quagmire  // roll like Joe

// roll like Joe

These emojis are comparable to co-speech gestures, which occur during an utterance and are associated with a specific constituent in speech (Esipova 2019; Hunter 2019). Co-text emojis and post-text emojis may be difficult to distinguish from one another when the word/phrase modified by the emoji is utterance-final, such as the  ,

,  , and

, and  emojis in example (8). More work will be needed to differentiate these cases. To me it seems that co-text emojis iconically enrich syntactic constituents smaller than the level of an utterance, so the function of the emojis in (5) could be analyzed the same way as the activity emojis in (4).

emojis in example (8). More work will be needed to differentiate these cases. To me it seems that co-text emojis iconically enrich syntactic constituents smaller than the level of an utterance, so the function of the emojis in (5) could be analyzed the same way as the activity emojis in (4).

I believe there is much interesting work to be done on co-text emojis, but this paper focuses on the morphology of the class of emojis described in the following section.

3.3 Pro-text emojis

The third class of emojis, pro-text emojis, are syntactically projected within a written utterance. These are so named for pro-speech gestures, which are also iconic elements that are syntactically projected within an utterance (Schlenker 2018). They are incredibly frequent across CMC in a variety of languages2, and are even commonly seen in some forms outside of electronic communication.

- (9)

- I

[int: love; beer]3

[int: love; beer]3

Several researchers have pointed out instances in which emojis appear as parts of speech within as sentence (Al-Rashdi 2018; Cohn et al. 2018; Pierini 2021). Pierini (2021) calls these at-issue emojis, and compares them to Schlenker’s typology of pro-speech gestures. While some work suggests that these emojis replace written words (Tieu et al. 2023), the facts I show in this paper suggest a more interesting morphological process. Take the following example from Pierini (2021).

- (10)

- She is the

[int: bomb] (Pierini 2021)

[int: bomb] (Pierini 2021)

In this example, if the emoji  is understood to be a replacement on an orthographic level for the fully formed English word ‹bomb›, then the possibility of morphosyntactic processes such as affixation happening with pro-text emojis would be surprising.

is understood to be a replacement on an orthographic level for the fully formed English word ‹bomb›, then the possibility of morphosyntactic processes such as affixation happening with pro-text emojis would be surprising.

The central argument of this paper, to be discussed and analyzed in detail in the remaining sections, is that pro-text do not replace words at all, but in fact represent free stems. I do this by demonstrating that, across a variety of languages, emojis can take affixes, which would not be expected if the emojis are merely replacing words on an orthographic level. Furthermore, these affixes often times do not correspond to the morphology of the word that is associated with an emoji. I then show that emojis can appear in cases where there is no clear equivalent in spoken language at all, and that emojis can undergo morphosyntactic processes such as lexicalization and grammaticalization. Additionally, I show that pro-text emojis need not be associated with covert spoken words, which is something Schlenker (2017: 38) claims of pro-speech gestures as well. Experimental evidence (Cohn et al. 2018; Tieu et al. 2023) suggests that pro-text emojis can behave and be interpreted as other stems are.

The use of pro-text emojis has several potential factors, including but not limited to abbreviation, iconic enrichment (Schlenker 2017), or simply stylistic choice of the speaker. While language users’ motivations in selecting a pro-text emoji over a preexisting word are certainly an interesting area worthy of more exploration, this choice has no effect on the morphological generalizations I explore in the following sections.

4 Morphology of Pro-text emojis

Here I introduce data showing pro-text emojis in various languages. In addition to showing emojis as grammatical elements, I also show them combining with different kind of affixes. The restrictions on affixations are crucial to the analysis here. Discussion of what this means for the morphological categorization of these emojis follows.

All of the data, unless noted otherwise, come from Twitter4. I collected these data using Twitter’s search tool, which allows users to search for a specific token (in this case, an emoji) and filter by several different factors, the most relevant one here being language. A search that returns very few results I take to be poorly attested and a search that returns no results I consider completely unattested, and is thus preceded by an asterisk. A drawback of Twitter’s search tool is that it does not return specific numbers of results, so if a search yields a volume of results that is too high to manually count, then the exact number of results remains unknown. It is possible to get more specific numbers using Twitter’s API tool, but since the acquisition of Twitter by Elon Musk in 2023 and several policy changes following that, the API tools are far more restricted and difficult to access. Another challenge is that, to my knowledge, no parsed corpus of language from Twitter considers the possibility that emojis may be grammatical elements. My examples – unless otherwise noted – are not isolated occurrences; rather, there are several pages worth of results. Any form of an emoji-affix combination with over 100 or so results I consider well-attested, and the grammatical examples I show are – unless otherwise noted – well-attested.

The notion that emojis combining with certain affixes can be grammatical or ungrammatical is further corroborated by the intuitions of native speakers who are proficient with emojis as a form of communication. Grammaticality judgments about the examples initially gathered from Twitter were collected both in-person and online from between 7 and 10 informants for non-English languages, and quite significantly more informants for the English examples (>25), elicited in both individual and group settings. I treat these judgments as any other types of grammaticality judgments are treated for syntactic theory (Collins 2019). Collecting grammaticality judgments about pro-text emojis – or any visual elements for that matter – seems to be a relatively new task that has not been done much elsewhere. As such, several considerations must be made clear.

It is not the case that every language user is proficient in using and understanding pro-text emojis to the same degree. While most English speakers would likely not have trouble understanding an example like (1), almost all of my informants over the age of 40 (and many who are younger as well) reported having no judgments about pro-text emojis taking affixes. Why some people have judgements on these data and others do not is certainly an issue of modality (Cohn & Schilperoord 2022). Just as gestures and spoken language constitute separate modalities, pictorial symbols such as – but of course not limited to – emojis constitute a separate modality from speech and written language (Kress 2009). Cohn & Schilperoord (2022) distinguish between three modalities for human communication: graphic, vocal, and bodily, with emojis falling into the graphic category, speech into the vocal category, and gestures into the bodily category.

It is simultaneously true that every language user has access to these modalities, but some people have much more developed and refined grammatical systems for certain modalities than others do. For example, virtually all humans use gestures in communication (Abner & Cooperrider & Goldin-Meadow 2015), yet sign language users gestures in a far more frequent, systematic, and granular way than non-signers do (Goldin-Meadow & Brentari 2017). Another example is that people who are not fully proficient in visual languages are still able to create and recognize basic shapes (Cohn 2012). As such, while most language users may be able to understand basic instantiations of pro-text emojis, it does not follow from that fact that every language user should have refined judgments about the acceptable distribution of pro-text emojis.

Cohn (2012, 2022) raises questions of acquisition of different modalities, which is relevant to explain who exactly can be said to be proficient with pro-text emojis. To acquire a visual communication system specific to CMC, engaging regularly in CMC is crucial. It is known that younger age groups tend to spend more time online (Scott et al. 2017; Perrin & Atske 2021). Additionally, younger people who have spent little to no time growing up in a world without regular access to CMC and digital keyboards are far more likely to be “natively” familiar with emojis in a way that older people are not. Indeed, many young people do not even remember a time in which their digital keyboard layouts did not have the capability of producing emojis. Therefore, age is taken to be a predictor of who is most likely to have reliable judgments about the grammaticality of pro-text emojis, as younger age is associated with more time spent online and greater familiarity with emojis. This is also reflected in the fact that younger people tend to use emojis in creative and innovative ways that people in older age brackets tend not to understand (Ishmael 2021).

This is to say that those who provided grammaticality judgments for pro-text emojis in this project are people who are native speakers of the language in question who regularly engage in CMC and who are highly familiar with using emojis. The author also qualifies as one such person for English. Interestingly, Romance language speakers who do not use emojis frequently all share strong judgments about the ungrammaticality of certain examples, which I explore further later on. Several individuals who do not identify as proficient emoji users were also asked for judgments, most of whom reported having none.

The examples in this paper are naturally occurring, are backed up by grammaticality judgments from a significant number of relevant language users, and are confirmed by being well-attested or not attested forms online.

4.1 Inflectional Affixation

Pro-text emojis appear where one would normally expect a word. Examples of these are numerous and easy to find in a multitude of languages and in several syntactic categories. Verbs in (11), nouns in (12), and adjectives in (13).

- (11)

- a.

- I

TEXAS! [int: love]

TEXAS! [int: love]

- b.

- We

you Prime Minister…[int: see]

you Prime Minister…[int: see]

- c.

- I’m gonna

u on ur forehead u look 2 cute [int: kiss]

u on ur forehead u look 2 cute [int: kiss]

- d.

- I need to

before I see the end of this game or I’ll be

before I see the end of this game or I’ll be  I missed it [int: sleep, sad]

I missed it [int: sleep, sad]

- (12)

- a.

- My hair has gotten so long I feel like a

[int: mermaid]

[int: mermaid]

- b.

-

is where the

is where the  is! [int: home; heart]

is! [int: home; heart]

- c.

- i play the

& the

& the  [int: violin; guitar]

[int: violin; guitar]

- d.

- joon’s eating

cubes from his iced

cubes from his iced  … [int: ice; coffee]

… [int: ice; coffee]

- (13)

- a.

- Pratik is always good at heart, he is a

person [int: happy, good]

person [int: happy, good]

- b.

- This has made me chuckle I needed this after a

day! [int: shit(ty)]

day! [int: shit(ty)]

- c.

- Just glad my

passport allows entry to New Zealand…. [int: Australian]

passport allows entry to New Zealand…. [int: Australian]

- d.

- Some

people were discriminated against at protest grounds [int: gay, LGBT]

people were discriminated against at protest grounds [int: gay, LGBT]

Examples such as these are, of course, not limited to English. See verbs (14) and nouns (15) in several languages below.

- (14)

- a.

- Я

- I love

- минское

- minsk-ADJ

- море

- sea

- и

- and

- мою

- my-ACC

- подружку

- girlfriend-ACC

- Леру (Russian)

- Lera-ACC

- ‘I love the Minsk sea and my girlfriend Lera’

- b.

- Al

- to-the

- rato

- while

- vamos

- go-1.pl

- a

- to

- see

- a

- to

- militares

- soldiers

- dando

- giving

- clases

- classes

- en

- in

- kinder (Spanish)

- kindergarten

- ‘Pretty soon we’ll see soldiers teaching Kindergarten classes’

- c.

- Agora

- now

- eu

- i

- fly

- pelo

- for-the

- mundão (Brazilian Portuguese)

- world

- ‘Now I’ll fly around the world’

- (15)

- a.

- Les

- The

- elephant

- de

- of

- la.

- the

- colère !

- anger!

- Laissez

- leave-imp

- nous

- us

- en

- in

- paix

- peace

- vous

- you

- humains ! (French)

- humans !

- ‘Angry elephant ! Leave us in peace humans !

- b.

- Der

- the

- football

- rollt! (German)

- rolls

- ‘The football rolls!’

- c.

- el

- the

- pinchazo

- thorn-AUG

- en

- in

- el

- the

- heart

- cuando

- when

- te

- you

- dicen

- say-3.pl

- algo

- something

- que

- that

- temías (Spanish)

- fear-2.sg.ipfv

- ‘The thorn in the heart when someone tells you something were afraid to hear’

It is abundantly clear from Twitter data alone that emojis can represent elements that are projected in the syntax of a sentence, and this is evident in many languages in the world. But is it appropriate to simply say that emojis represent words? The following data show that emojis can take affixes, which suggests that emojis represent something smaller than what is conventionally referred to as a word. If emojis simply replace a word at the level of a sentence, then affixation should not be possible, but it is. Therefore more analysis is needed.

4.1.1 English Inflectional Affixes

See emojis in English taking inflectional – or grammatical – affixes for third person singular present agreement (16), past tense inflectional morphology (17), present progressive inflection (18), and participial inflection (19). All English inflectional affixes are well-attested with pro-text emojis.

- (16)

- a.

- He

s to

s to  [int: loves; read]

[int: loves; read]

- b.

- If in bed and she

’s his face while we do the nasty….I’m cool wit dat! [int: looks at]5

’s his face while we do the nasty….I’m cool wit dat! [int: looks at]5

- c.

- But you must walk him often and he

’s his diaper a lot. [int: poops]

’s his diaper a lot. [int: poops]

- (17)

- a.

- My therapist

ed me so I took selfies in the parking lot [int: ghosted]

ed me so I took selfies in the parking lot [int: ghosted]

- b.

- IMO we

ed better without him. [int: looked]

ed better without him. [int: looked]

- c.

- …

d each other like brothers… [int: loved]

d each other like brothers… [int: loved]

- (18)

- a.

- fuck disney plus im

ing [int: pirating]

ing [int: pirating]

- b.

- likeeee the secondhand embarrassment is

ing meee [int: killing]

ing meee [int: killing]

- c.

- …you may Think they

ing marathon to win gold… [int: running]

ing marathon to win gold… [int: running]

- (19)

- a.

- This was someone else’s twt, but I would have

d it had it been yours [int: loved]

d it had it been yours [int: loved]

- b.

- This world has

ed my soul with its pain, asking for its return in code [int: kissed]

ed my soul with its pain, asking for its return in code [int: kissed]

- c.

- We look forward to seeing what gets you

’ed up next. [int: fired up]

’ed up next. [int: fired up]

English also allows the pluralization of nominal emojis.

- (20)

- a.

- The way

’s act like it was so long ago when its just in their backyard [int: whites]

’s act like it was so long ago when its just in their backyard [int: whites]

- b.

- Good luck to all our

s swimming today [int: dolphins]

s swimming today [int: dolphins]

- c.

- a couple of

s smoking

s smoking  s [int: fags; fags]

s [int: fags; fags]

Comparative and superlative affixes also appear on English adjectival emojis.

- (21)

- a.

- Bitch say it to my face I’ll drop u

er than 4 o’clock [int: deader]

er than 4 o’clock [int: deader]

- b.

- This is the

est scene ever created! I’m dying!!!!! [int: whitest]

est scene ever created! I’m dying!!!!! [int: whitest]

- c.

-

er than the price of gas [int: higher]

er than the price of gas [int: higher]

The main generalization from these English data are clear: pro-text emojis can appear with affixes in English. Before making more meaningful claims about this, though, it is necessary to look at data from other languages with different morphology. I use German and Spanish here.

4.1.2 German Inflectional Affixes

These processes are not only possible in English. Take the following German examples showing verbal affixation (22), pluralization of nouns (23), diminutive affixes on nouns (24), and comparative/superlative morphology on adjectives (25).

- (22)

- a.

- Und

- and

- dann

- then

- kommen

- come.3pl

- erst

- {for

- mal

- now}

- 3

- 3

- Tweets,

- tweets

- die

- that

- Du

- you

- ge

t

t - PTCP-love-PST

- hast.

- have.2sg.pst

- ‘And then there’s the three tweets that you’ve liked’

- b.

- Mehr

- more

- so

- so

- vornerum

- in.front.of.around

- ge

- PTCP-eye.v

- ‘More like eyeing around in front’

- c.

- Wir

- we

-

en

en - block-1.pl.pres

- alle!

- all!

- ‘We block everyone!’

- (23)

- a.

- Vielen

- many

- lieben

- fond

- Dank

- thank

- fur

- for

- die

- the

-

e,

e, - star-PL

- liebe

- love

- ‘Many thanks for the stars, love’

- b.

- Ich

- I

- geb zu,

- {admit}

- ich

- I

- habe

- have

- gehamstert

- hoarded

-

alles

alles -

everything

everything - für

- for

- die

- the

-

n

n - cat-PL

- ‘I admit, I’ve been hoarding – (I’d do) everything for the cats.’

- c.

- Gewitter

- thunderstorm

-

n,

n, - goat-pl,

-

n,

n, - cat-pl,

-

e,

e, - pig-pl,

- blaue

- blue

- Kartoffeln

- potatoes

- un

- and

- Scheekönige.

- snow.kings.

- Biz

- Until

- jetzt

- now

- super!

- great

- ‘A thunderstorm, goats, cats, pigs, blue potatoes and snow kings. So far all is great!’

- (24)

- a.

- Guten

- good

- Morgen

- morning

- meine

- my

-

chen

chen - dear-DIM

- ‘Good morning my dear ones’

- b.

- Wünsche

- wish.1sg.prs

- dir

- you.dat

- heute

- today

-

- luck-music-love

- und

- and

- immer

- always

- ein

- a

- lecker

- tasty

-

chen

chen - coffee-DIM

- ‘Today, I wish you luck, music, love, and that you may always have nice coffee’

- c.

- Wer

- who

- bis

- until

- hierher

- here

- gelesen

- read.ptcp

- hat:

- has:

- ich

- I

- mag

- like

- dich.

- you.acc.

- Kriegst

- get.2sg.prs

- ein

- a

-

chen

chen - little-star-DIM

- ‘(To) those who have read all through here: I like you, you get a star”

- (25)

- a.

- Ihr

- y’all

- seid

- are

- unsere

- our

-

sten

sten - beloved-SPRL

- Menschen.

- humans

- ‘You are our most beloved people’

- b.

-

sten

sten - heartfelt-SPRL

- Dank

- thank

- liebe

- dear

- Alexandra,

- Alexandra,

- Selbiges

- the.same

- wünsche

- wish.1sg.prs

- ich

- I

- dir

- you.dat

- auch

- also

- ‘My most heartfelt thanks, dear Alexandra, I wish the same to you’

It seems, then, that German pro-text emojis can take the same kinds of inflectional affixes as English emojis, including the diminutive suffix. In the German examples we can see cases of more robust agreement systems than English involving verbal agreement markers and plural markers on nouns that change based on Case. This is not surprising since German has a much larger inventory of inflectional affixes than English does.

Despite differences in the number of available inflectional affixes, English and German share many similarities in their inflectional systems. English inflectional morphology is always done to an uninflected base form that itself can stand alone as a word (or a ‘free form’ as described in Bloomfield (1933)). The same is true of German nouns and adjectives, but not necessarily of verbs (Kastovsky 1994). This means that for English inflectional stems and for German nominal and adjectival inflectional stems, there is an unmarked base form that also corresponds to a possible freestanding word. For German verbs, however, there is no unmarked base form. This means that German verbal stems need not correspond to a possible freestanding word.

Kastovsky (1994) describes the inflectional system of German nouns and adjectives and of English as a whole as word-based (Sapir 1925), since the inflectional stems can function as standalone words. He contrasts this with a stem-based system, such as the one for German verbs, in which the base form cannot function as a freestanding word. Before continuing with this discussion of morphological levels, it is necessary to look at data from another, non-Germanic language.

4.1.3 Spanish Inflectional Affixes

Pro-text emojis in Spanish can be seen taking a variety of inflectional affixes as well. Plural suffixes are well-attested for nouns (26) and adjectives (27).

- (26)

- a.

- Que

- that

- los

- the-masc.pl

-

s

s - dog-pl

- sigan

- continue-3.pl.sbjv

- ladrando

- stealing

- ‘May the dogs keep on stealing’

- b.

- Si

- if

- captas

- capture-2.sg

- o

- or

- saco

- take-1.sg

- las

- the-fem.pl

-

s

s - pear-pl

- y

- and

- las

- the-fem.pl

-

s.

s. - apple-pl

- ‘If you capture or I take out the pears and the apples’

- c.

- Unos

- some

-

s

s - coffee-pl

- para

- for

- el

- the

- frío

- cold

- y

- and

- sueño

- dream

- ‘Some coffees for the cold and tiredness’

- (27)

- Podría

- can-1.sg.cond

- comer

- eat

- chilaquiles

- chilaquiles

- todos

- all-masc.pl

- los

- the-masc.pl

-

s

s - dog-pl

- días.

- days.

- ‘I could eat chilaquiles every damn day’

The Spanish diminutive suffix (28) and augmentative suffix (30) can also be seen with pro-text emoji nouns. Interestingly, the diminutive suffix seems sensitive to the phonological information of the stem as both the allomorphs -ito and -cito are attested. Though, interestingly, many emojis that can take -cito as a diminutive suffix can also take -ito (compare (28b,c) to (29)), which is evidence that pro-text emojis are not inherently specified for phonological form.

- (28)

- a.

- Solito

- alone-DIM

- como

- like

- un

- a

-

ito

ito - dog-DIM

- me

- me

- dejarom

- left-3.pl

- ‘They left me alone like a puppy dog’

- b.

- Alto

- high

- finde,

- weekend

- el

- the-masc.sg

-

cito

cito - heart-DIM

- lleno

- full

- de

- of

- amorrr

- love

- ‘Great weekend, my heart is full of love’

- c.

- Fan

- fan

- del

- of-the

-

cito

cito - sun-DIM

- de

- of

- otoño-invierno

- autumn-winter

- ‘Fan of the little sun of autumn-winter’

- (29)

- a.

- Amo

- love-1.sg

- a

- to

- mi

- my

- novio

- boyfriend

- con

- with

- todo

- all

- mi

- my

-

ito

ito - heart-DIM

- ‘I love my boyfriend with all my heart-DIM’

- b.

- Un

- one

- día

- day

- más

- more

- sin

- without

- el

- the

-

ito

ito - sun-DIM

- ‘One more day without the sun-DIM’

- (29)

- a.

- Así

- so

- me

- me

- pone

- put-3.sg

- el

- the

- dog

-

azo

azo - sun-AUG

- ‘The fucking sun makes me like this’

- b.

- Otro

- other

-

AZO

AZO - goal-AUG

- de

- of

- Ángel

- Angel

- Robles

- Robles

- y

- and

- goal

- de

- of

- Guillermo

- Guillermo

- Martinez

- Martinez

- ‘Another big goal for Angel Robles and a goal for Guillermo Martinez’

- c.

- No

- no

- pues

- then

- gracias

- thanks

- por

- for

- el

- the-masc.sg

-

azo

azo - plane-AUG

- monumental!

- monumental

- ‘No thanks for the monumental disaster!’

According to Twitter data and the intuitions of native Spanish speakers, these are the only inflectional affixes with pro-text emojis that are possible in Spanish. This notably leaves out gender suffixes on nominals and verbal agreement/tense suffixes, which is important for this analysis.

Observe the following examples, which are confirmed ungrammatical by a significant number of native Spanish speakers who are proficient emoji users. Additionally, Twitter searches for emojis followed by verbal phi-feature and tense agreement markers (and infinitival suffixes) and those followed by nominal/adjectival gender suffixes yield zero results. As such, I confidently label these examples ungrammatical due to not being attested at all and also being ubiquitously rejected by all native speakers questioned.

- (31)

- a.

- *Yo

- I

-

o

o - love-1.sg

- a

- to

- mi

- my

- novio

- boyfriend

- [int: yo amo a mi novio]

- ‘I love my boyfriend’

- b.

- *Quiero

- want-1.sg

-

ar

ar - watch-INF

- la

- the

- tele

- TV

- [int: quiero mirar la tele]

- ‘I want to watch TV’

- c.

- *Nos

- refl

-

ábamos

ábamos - kiss-1.sg.ipfv

- [int: nos besábamos]

- ‘We kissed each other’

- (32)

- a.

- *Todos

- all the

- los

os

os - dog-m.pl

- días

- days

- [int: todos los perros días]

- ‘Every fucking day’

- b.

- *Toda

- all the

- la

a

a - dog-f.sg

- gente

- people

- [int: toda la perra gente]

- ‘All of the fucking people’

With this additional data showing what is and is not possible with pro-text emojis in Spanish, the task of coming up with a morphological theory of these emojis becomes much clearer. I make sense of these examples in the following subsection.

4.1.4 Emojis as Stems

At this point it is clear that pro-text emojis do not merely replace words in a sentence after the derivation has been completed: they represent something smaller than a word that actually is part of the morphosyntactic construction of the sentence. Since emojis take affixes, they must represent something below the level of a word in a hierarchy of morphological levels that is something akin to the following (Lieber 1976; Selkirk 1982; Olsen 1986):

- (33)

- Words > stems > roots

I take ‘word’ here to mean any freestanding form of a given syntactic category with any acceptable number of inflectional and derivational affixes. Words are typically independently meaningful and often the target of syntactic operations such as movement. Stems, the level below words, are a lexically-typed base to which inflectional affixation is done. Stems may themselves contain affixes and their forms may or may not correspond with an acceptable freestanding words. Roots are bare elements containing zero affixes of any kind and often do not correspond to any freestanding form. There is much variation of these definitions in the literature (Kiparsky 2020; Lohndal 2020). These notions – especially that of a stem – are very important to this analysis and will be explored in detail in this section and following sections.

Stems are specified for a given syntactic category and are the target of affixation (Aronoff 1994). Notions of different types of morphological stems will be useful in determining what exactly pro-text emojis can represent, morphosyntactically speaking. The idea of the level-ordering hypothesis in morphology (Siegel 1974; Giegerich 1999; 2005; Kiparsky 2015; Bermúdez-Otero 2018) echoes what came up in Section 4.1.2. from Kastovsky (1994) about word-based and stem-based morphology by distinguishing between word-level and stem-level affixes.

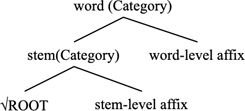

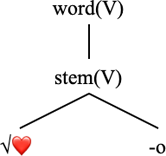

To reiterate, all English inflectional affixes and all German nominal/adjectival inflectional affixes are word-based, while all German verbal affixes are stem-based. The terminology ‘word’ and ‘stem’ starts to get confusing as there are several slightly-competing definitions of these concepts floating around in the literature. Here I clarify that stem-level affixes promote roots to lexically-typed free stems, and word-level affixes promote lexically-typed stems (which may or many not already be able to function as a freestanding word6) to inflected freestanding words. Therefore, the names ‘word-level’ and ‘stem-level’ refer to the output of the affixation, not the input. I now give an example of the representation of morphological structure assumed here on out. Roots are the lowest level that combine with an affix, that affix being a word-level affix. Intermediate stem levels combine with word-level affixes from which they are either promoted to words or become a stem for more affixes. The highest node represents a freestanding word.

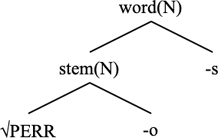

- (34)

- Morphological structure of words

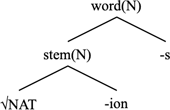

Before getting into pro-text emoji examples, take the English word nations as an example of these levels. Here we have the root √NAT, the derivational stem-level suffix -ion, and the inflectional word-level suffix -s.

- (35)

- Structure of English nations

The root √NAT must take some form of derivational morphology (here, the nominalizing suffix -ion to be promoted to a lexically typed (meaning that it is specified for a given syntactic category) stem, otherwise it is not a candidate for inflectional affixation, hence the ungrammaticality of a form like *nats with this root. Some English roots, such as √OPT may be promoted to a lexically typed stem via a null derivational morpheme.

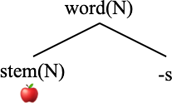

With these generalizations in mind, let us take a grammatical example of a pro-text emoji such as  s, meaning apples [N, pl]. I am assuming in the morphological and syntactic derivations that these pro-text emojis directly represent the stems merged into these positions, as opposed to replacing something else at a later point in the derivation of the utterance.

s, meaning apples [N, pl]. I am assuming in the morphological and syntactic derivations that these pro-text emojis directly represent the stems merged into these positions, as opposed to replacing something else at a later point in the derivation of the utterance.

- (36)

- Structure of English

s

s

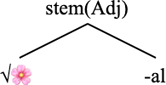

We can contrast this with an unattested form such as * al,7 meaning floral [Adj], the structure of which is given below. In addition to being unattested, this form is also judged unacceptable by English speaking emoji users, especially in contrast to an example like

al,7 meaning floral [Adj], the structure of which is given below. In addition to being unattested, this form is also judged unacceptable by English speaking emoji users, especially in contrast to an example like  s above.

s above.

- (37)

- Structure of English *

al

al - *

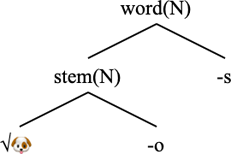

This contrasts suggests that emojis are unavailable as roots and must instead represent lexically-typed stems, since pro-text emojis are not able to appear taking a stem-level affix that combines directly with a root. As further evidence of this, I introduce the differences between two types of Spanish nominal suffixes: gender and number suffixes.

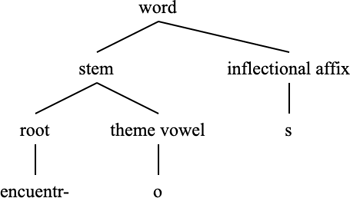

Gender suffixes are always closest to the root in Spanish, and number always follows gender. Take the Spanish example perros ‘dogs’, with the base form √PERR followed by the masculine suffix -o and the plural suffix -s. The order ROOT-GEN-NUM is the only possible configuration of these morphemes, and no other combination is possible (*perrso is completely impossible). This means that gender is undeniably closer to the root than number, but how close exactly is a matter of some contention. The first possibility is that gender is an inflectional suffix that attaches to nominal stems (Picallo 1991; Alexiadou 2004). See perros with this internal structure, in which the root √PERR must be an available candidate for affixation. The second option, which is that gender features are actually located on the nominalizing head, means that the gender suffix itself is what promotes the root to a nominal stem. This analysis is explored in detail in Kramer (2016). For our purposes, this means that the gender suffix is directly adjoined to the root, creating a nominal stem that can be inflected.

- (38)

- Structure of Spanish perros with gender nominalizer

There is sufficient evidence to suggest emojis cannot represent roots, With (38), the gender suffix is what turns the root into a nominal, as the gender feature is located on the nominalizing head in the analysis from Kramer (2016). As the stem, not the root, is the target of inflectional affixation, this means that the smallest possible stem in the word perros does not correspond with the root √PERR, but is the root plus the nominalizing head -o: perro. In other words, the gender suffix is a stem-level suffix, and the number suffix is a word-level suffix. So, the internal structure of  s would be as follows.

s would be as follows.

- (39)

- Structure of Spanish

s

s

Since emojis are not available to represent roots, * os is ruled out as an acceptable form.

os is ruled out as an acceptable form.

- (40)

- Structure of Spanish *

os

os - *

Assuming stems are what are stored in the language user’s lexicon (Anderson 1992; Zwicky 1992; Aronoff 1994), these bare root forms of Spanish nominals are not actually available as morphosyntactic primitives since they are not accessible directly from the lexicon. Stems, however, do contain this necessary morphosyntactic information. The gender suffixes of Spanish nouns and adjectives,, as they create a stem from the root, are the smallest unit in the lexicon of elements of these syntactic categories. Bermúdez-Otero (2013: 5) gives the following tree, slightly modified for the purpose of this paper, for the noun encuentros [masc, pl].

- (41)

- Structure of Spanish encuentros

In this structure, the stem is entered in lexicon, not anything lower. As this relates to pro-text emojis, this means that they cannot appear as nouns or adjectives in Spanish as anything smaller than what is entered in the lexicon – anything smaller than a stem.

This paradigm also explains the inability of Spanish verbal emojis to appear with inflectional affixes, as these inflectional affixes also combine directly with the root. The differences between English and Spanish verbal emojis and this proposed explanation here are in line with preexisting observations about English and Spanish verbal morphology. We would not expect some primitive Spanish verbal root without affixes to exist in the lexicon. According to Lasnik (1995), French verbs are fully inflected in the lexicon of French speakers, so every possible inflected form of a verb is stored in the speaker’s lexicon, which is related to the fact that there are no bare forms of verbs, with even the infinitive forms having a suffix (the same is true of Spanish). Lasnik also argues that all English forms are bare in the lexicon, with verbal affixes being inserted in the syntax. Indeed, the same contrast between affixation with English and Spanish verbal emojis also exists with English and French, with an example such as (42) being incredibly well-attested online and confirmed acceptable by multiple native speakers. In contrast, (43), and examples like it of a verbal inflectional affix containing phi and tense information attaching to a pro-text emoji are not attested whatsoever online and are universally rejected by French speakers.

- (42)

- Nous

- we

- love

- Paris

- Paris

- ‘We love Paris’

- (43)

- *Nous

- we

-

ons

ons - love-1.pl

- Paris

- Paris

- ‘We love Paris’

This analysis of French verbal morphology can indeed be extended to Spanish, as Spanish verbs are also stored in the lexicon this way as inflected stems. For the Spanish verb amar (love), there is no root form in the lexicon am- without the infinitival suffix. Rather, there are lexical entries for every possible verb form including the infinitive and all inflectional combinations of person, number, and tense (am-o, am-as, am-a, am-amos, etc.). This unavailability of the bare form as a lexical stem means that the inflectional affixes are inseparable from the root on a lexical level. Since there is no bare verbal form available in Spanish, an emoji in the following position is not possible.

- (44)

- Structure of Spanish *

o (love-1.sg) [int: amo]

o (love-1.sg) [int: amo] - *

Spanish verbal emojis cannot appear with affixes because there exists no level in the lexicon at which the inflected Spanish verbal stems are separable from their roots. This is different from English, where verbs are stored in the lexicon as bare stems, hence the grammaticality of (16–19). Spanish gender suffixes for nouns and adjectives, as well as Spanish verbal inflectional affixes, form part of the basic elements of the lexicon; they are stem-level affixes. All of the examples thus far demonstrate that emojis appear in positions of lexically-typed stems.

Saying that pro-text emojis are available as roots would vastly overpredict the places where we see them and the types of affixes that we see them combine with. Looking at the affixes that pro-text emojis do and do not combine with in different languages, it is clear that pro-text emojis prefer taking word-level affixes. As such, across the languages discussed so far, it is clear that the distribution of pro-text emojis corresponds perfectly with other elements that are known to be stems, not roots, so it is safe to say that pro-text emojis represent stems. Preliminary data suggest that this is also the case in Slavic languages such as Russian (Thelin 1973), where forms like (45a) are attested and used by native speakers, whereas forms like (45b) are not attested at all and judged unacceptable by native speakers.

- (45)

- a.

- Я

- I

- love

- тебя

- you.acc

- ‘I love you’

- b.

- *Я

- I

-

лю/ю

лю/ю - love-1.sg.pres

- тебя

- you.acc

- ‘I love you’

Perhaps the intuition that pro-text emojis are words is not so far-off, an intuition reflected by the Oxford Word of The Year in 2015, which was the emoji  . The truth of this intuition is that pro-speech only combine with word-level affixes, not stem-level affixes. It is accurate to say, then, that pro-text emojis must represent something that can be lexically represented.

. The truth of this intuition is that pro-speech only combine with word-level affixes, not stem-level affixes. It is accurate to say, then, that pro-text emojis must represent something that can be lexically represented.

4.2 Derivational Affixation

Thus far we have only seen inflectional affixes. In English, all inflectional affixes are word-level affixes, but this clearly is not the case in a language such as Spanish. So, what happens in English with stem-level affixes? For this we must turn to derivational – or word changing – affixation. Many English speakers accept these examples, and there is no shortage of them online. Examples including but not limited to adjective forming -ly (46), adjective forming -y (47) nominalizing -ness (48), and adjective forming -ish (49) are abundant. Even the agentive -er suffix is attested (50).

- (46)

- Have a

ly Day! [int: lovely]

ly Day! [int: lovely]

- (47)

- a.

- so

y boys [int: icy]

y boys [int: icy]

- b.

- now no one can say I am being dramatic when I call it a

y day!!!! [int: shitty]

y day!!!! [int: shitty]

- c.

- Just

y. [int: shitty]

y. [int: shitty]

- (48)

- a.

- Happy New Year Krystal all the love and

ness to you [int: happiness]

ness to you [int: happiness]

- b.

- Looking at this picture, just brings me great

ness [int: sadness]

ness [int: sadness]

- c.

- Some days I think I’ve reached my peak

’ness. [int: gayness]

’ness. [int: gayness]

- (49)

- a.

- I real feel

ish [int: awkwardish?]

ish [int: awkwardish?]

- b.

- This

is just getting

is just getting  ish. [int: childish]

ish. [int: childish]

- (50)

- a.

- Most under rated

-er [int: writer]

-er [int: writer]

- b.

- Trump doesn’t see a problem with that because he is a 1st class

er [int: ass-kisser]

er [int: ass-kisser]

- c.

- Every

er should have a stash [int: smoker]

er should have a stash [int: smoker]

These examples are not to suggest that all derivational affixes are compatible with pro-text emojis. Take another unattested example that native English speakers proficient with emojis judge ungrammatical.

- (51)

- *

ity killed the cat [int: Curiosity killed the cat]

ity killed the cat [int: Curiosity killed the cat]

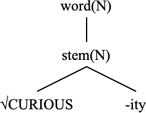

Once again, the choice of emoji is not what makes this sentence ungrammatical. Language users surely could make endless arguments about what emoji better conveys curious better among the many possible emojis, but it is the position of the emoji here that makes it ungrammatical. No emoji is attested as being modified by the nominalizing suffix -ity, whereas there are abundant examples of emojis being modified by -ness. There even are examples of emojis with -ness that have a similar interpretation to curiousness, which are also judged to be better than (51) by emoji-proficient native speakers.

- (52)

- I feel like I remember him commenting on the

-ness of her outfit [int: curiousness]

-ness of her outfit [int: curiousness]

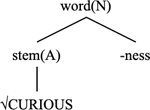

The difference between these cases is that -ity is a stem-level derivational affix, while -ness is a word-level derivational affix (Kiparsky 2020). This distinction between derivational affixes is also noted in Distributed Morphology (Marantz 2007; Embick & Marantz 2008). Here the difference is captured by the terms inner derivation and outer derivation. Inner derivation is the process of attaching derivational affixes to roots while outer derivation is the process of attaching derivational affixes to lexically-typed stems.

The difference between curiosity and curiousness, then, is that the -ity of curiosity attaches directly to the root √CURIOUS, whereas -ness in curiousness attaches to the adjectival stem curious. This distinction is also visible in the phonological and orthographic effects that these processes have on their final products, as -ity changes the stress and spelling of the root, whereas the root curious as it is pronounced in isolation is preserved in the word curiousness. Since pro-text emojis cannot be roots,  ness is acceptable as curiousness, but *

ness is acceptable as curiousness, but * ity is not acceptable as curiosity. See the structures below.

ity is not acceptable as curiosity. See the structures below.

- (53)

- Structure of English curiosity

- (54)

- Structure of English curiousness

- (55)

- Structure of English *

ity

ity

- (56)

- Structure of English

ness

ness

It is the case that inner layer derivational affixes may not appear after a pro-text emoji. This is completely expected under the assumption that emojis must represent lexically-typed stems, not roots. This assumption is generalized as the following condition.

- (57)

- The Pro-Text Emoji Condition

- Pro-text emojis must represent a stem that is specified for a given syntactic category.

I now turn to an apparent violation of the Pro-Text Emoji Condition. But first, the inability of a certain English affix to combine with pro-text emojis must be established.

- (58)

- a.

- *I only wear

als in the spring [int: floral]

als in the spring [int: floral]

- b.

- *You look

ar to me [int: familiar]

ar to me [int: familiar]

- c.

- *We have

al insurance [int: dental]

al insurance [int: dental]

- d.

- *Ready for the

ar new year [int: lunar]

ar new year [int: lunar]

Based on these data, it seems as if emojis with the adjective-forming -al/-ar suffix are not permitted. The suffix -al (and its allomorphic variant -ar) is a stem-level suffix (Kiparsky 2020), so this is in line with the condition above. Yet, the following example somewhat attested (though I am not sure if I myself accept these as grammatical).

- (59)

- a.

- Operation Normal: Trump Goes

-al [int: global]

-al [int: global]

- b.

- The

to disrupting the

to disrupting the  al hegemony is controlling the inventory of laundromats

al hegemony is controlling the inventory of laundromats

- c.

- We are currently at 420ppm CO2 & +1.1°C increase in

al temp

al temp

I now turn to a few other examples in which emojis appear after what look like inner-layer derivational affixes.

- (60)

- a.

- Le Président…is going to avoid the term

-ization from now [int: Finlandization]

-ization from now [int: Finlandization]

- b.

- same Montreal street before/after

ization [int: pedestrianization]

ization [int: pedestrianization]

- c.

- TRUMP NK DE

IZATION: FAILED [int: denuclearization]

IZATION: FAILED [int: denuclearization]

- (61)

- a.

- the whole trump administration literally…

ized it [int: weaponized]

ized it [int: weaponized]

- b.

- …as symptoms of the end-stage disease of

ized society [int: atomized]

ized society [int: atomized]

- c.

- We’re getting

ized. [int: Islamized]

ized. [int: Islamized]

Examples (59)–(61) all show stem-level affixes (Kiparsky 2020) appearing after pro-text emojis. (59) shows adjective-forming -al, and (60) and (61) both show verb-forming -ize, with (60) having more derivational affixes stacked on top of it, and (61) showing an inflectional affix following it. While these examples may seem problematic, the fact is that these affixes can either be word-level and stem-level (Siegel 1974; Aronoff 1976; Selkirk 1982; Aronoff & Sridhar 1983). Giegerich (1999) refers to these as dual membership affixes, while Kiparsky (2020) calls them chameleon affixes. The affixes can attach to bound roots as well as words (Giegerich 1999: 13). This contrast is clear with the attested pro-text emoji examples, as well as the unattested examples.

The  emoji in (59) clearly corresponds to the English free morpheme globe. Looking at (58), the emojis correspond to the bound roots flor- (a), famili- (b), dent- (c), and lun- (d). Similarly, the examples in (60) and (61) all correspond to free morphemes in English. Some of these are proper names such as Finland and Islam, which intuitively must be specified as nominal. Additionally some of these emojis correspond to words that contain category-specific morphology of some kind, i.e. -ar of nuclear and -ian of pedestrian. As such, it only makes sense to posit that these instances of -al and -ize are actually word-level affixes. An example of the stem-level suffix -ize would be a word such as militarize, in which the root is a bound morpheme of no specific syntactic category. Indeed, it is not possible to represent this root with an emoji, as something like *

emoji in (59) clearly corresponds to the English free morpheme globe. Looking at (58), the emojis correspond to the bound roots flor- (a), famili- (b), dent- (c), and lun- (d). Similarly, the examples in (60) and (61) all correspond to free morphemes in English. Some of these are proper names such as Finland and Islam, which intuitively must be specified as nominal. Additionally some of these emojis correspond to words that contain category-specific morphology of some kind, i.e. -ar of nuclear and -ian of pedestrian. As such, it only makes sense to posit that these instances of -al and -ize are actually word-level affixes. An example of the stem-level suffix -ize would be a word such as militarize, in which the root is a bound morpheme of no specific syntactic category. Indeed, it is not possible to represent this root with an emoji, as something like * ize or *

ize or * ize is not attested at all (on Twitter or Google) and admittedly very difficult to parse. This again lends credence to the condition that pro-text emojis can only occur as lexically-typed stems.

ize is not attested at all (on Twitter or Google) and admittedly very difficult to parse. This again lends credence to the condition that pro-text emojis can only occur as lexically-typed stems.

4.3 Morphological Irregularities

Circling back to inflectional morphology, there are inflectional forms in English that are irregular which can be regularized in the presence of a pro-text emoji. See the following examples.

- (62)

- a.

- counting

s to fall asleep [int: sheep]

s to fall asleep [int: sheep]

- b.

- Lemme tell you bout these 3 blind

s [int: mice]

s [int: mice]

- c.

- Finna search for some bigger

s for my

s for my  s [int: diamond;, teeth]

s [int: diamond;, teeth]

Similarly, while the following examples are attested, there are no attested instances of * i or *

i or * i, which are degraded.

i, which are degraded.

- (63)

- a.

- whos idea was it to put

’s at the headboard of a bed tf [int: cactuses]

’s at the headboard of a bed tf [int: cactuses]

- b.

- We need

s &

s &  es in that case! [int: crabs, octopuses]

es in that case! [int: crabs, octopuses]

Irregular forms that involve ablaut or plural suffixes other than -s are not available for pro-text emojis as the emojis themselves are the stem. In other words, the stem has no vowels to be ablauted. For the irregular plural suffixes such as cacti, the derivation would involve stem-level affixation to the root as these forms come from Latin, which forms plurals via stem-level derivation, which we have already established that emojis cannot do.

4.4 Interim Summary

So far I have demonstrated, among the ways in which emojis are used in language, there is a distinct category of emojis functioning as grammatical elements, called pro-text emojis. Upon further examination of data from Twitter as well as the judgments of native speakers in English, German, Spanish (and French and Russian to some degree) it becomes clear that pro-text emojis felicitously and regularly are modified by both inflectional and derivational affixes. Analysis of the types of affixation possible across the aforementioned languages as well as of current morphological theory strongly suggests that pro-text emojis are only possible as stems of a specified syntactic category that take word-level affixes, which in English includes inflectional affixes and some derivational affixes. This generalization, summarized in The Pro-Text Emoji Condition of (57), has been reached not by operating under the assumption that pro-text emojis must work the same way in different languages, but by observing in multiple languages a similarity in the types of affixes that are permitted and not permitted with pro-text emojis.

There is an interesting cross-linguistic contrast from the data in this section that merits discussion as well, namely that the Romance ungrammatical examples are more disliked than the English ungrammatical examples. By this I mean that even the Spanish and French speakers who are not proficient in emoji use have strong intuitions that the ungrammatical examples of pro speech emojis are bad, while also accepting the grammatical ones. This is notably different from English speakers who are not proficient emoji users who often do not have strong judgments either way about these examples (though those who are proficient emoji users do have strong judgments). From the conversations I have had with some German speakers about this issue, German patterns more closely to English in this respect. This points to interesting differences in the morphological systems of English (or, Germanic, perhaps more broadly) and Romance as a whole. This builds on work by Lasnik (1995) and Uriagereka & Gallegos (2023) about the way that inflected verb forms are represented in the lexicon in English and Romance, respectively. According to these approaches,

Evidence from the regular inflectional morphology of pro-text emojis whose closest lexical equivalent inflects irregularly suggests that pro-text emojis can be morphologically totally distinct from the words whose meanings they correspond to. This does not necessarily mean, however, that pro-text emojis are always distinct lexical items on their own. It is important to keep in mind that emojis are first and foremost orthographic units. Just as it is not necessary to posit that eleven and 11 are not representations of distinct lexical items, it may not be necessary to posit that every pro-text emoji suggests a distinct lexical item from a preexisting word with a similar or identical meaning, but as seen in Section 4.3., they may not always be the same, either. As such, pro-text emojis, since they do not specify phonological content like traditional orthography does, may be ambiguous as to exactly what lexical item they refer to. Take the following examples of the same emoji referring to multiple lexical items (64) and different emojis referring to the same lexical item (65) as evidence of this.

- (64)

- a.

- I want to

forever [int: sleep]

forever [int: sleep]

- b.

- This edible about to have me in my

like… [int: bed]

like… [int: bed]

- c.

-

of lies [int: tired]

of lies [int: tired]

- (65)

- a.

- I want to

forever [int: sleep]

forever [int: sleep]

- b.

- Don’t disturb me, I’m trying to

[int: sleep]

[int: sleep]

- c.

- I

on and off all day! [int: sleep]

on and off all day! [int: sleep]

With this ambiguity, it is possible to have several different types of lexical representation for pro-text emojis. In Section 5 I show that pro-text emojis can undergo processes of lexical change such as lexicalization and grammaticalization, and in Section 6 I discuss issues of iconicity and representation, showing that certain types of pro-text emojis may be directly represented in the lexicon.

5 Pro-text emojis and Language Change

As grammatical elements, it stands to reason that pro-text emojis are sensitive to processes of morphosyntactic change, which is exactly what we see. This means undergoing category changes, being borrowed between languages, novel forms being innovated, and the like. In this section I discuss pro-text emojis undergoing morphological processes of language change, namely lexicalization (Section 5.1.) and grammaticalization (Section 5.2.).

5.1 Lexicalization

In this section I discuss cases of emojis undergoing lexicalization, which here means that pro-text emojis become uniquely associated with a novel stem in the language user’s lexicon. I also compare these to processes of lexicalizing abbreviations, which is another common phenomenon in CMC, though not exclusive to CMC, just as the use of pictograms to represent grammatical elements can be found outside of CMC as well.

5.1.1 Novel Pro-Speech Emojis

It is quite common to see expressive emojis functioning as verbs.

- (66)

- a.

- Well you can see me

ing but yeahhh i signed up for this. [int: facepalming]

ing but yeahhh i signed up for this. [int: facepalming]

- b.

- my brother caught me

ing [int: just standing there]

ing [int: just standing there]

To focus on a specific example, take  as an expressive emoji.

as an expressive emoji.

- (67)

- a.

- He flew 40 hours from the UK to take me on our first date

- b.

- friendly reminder that Grogu got Din a father’s day gift

- c.

- Pisces moon got me wanting some love & affection

Now, observe the same emoji with verbal morphology. Here I leave out a translation of the emoji in brackets in the examples as I discuss it in the text.

- (68)

- a.

- Don’t

at me, you little bottom

at me, you little bottom

- b.

- never in my life have i

ed at a girl like this

ed at a girl like this

- c.

- can we all just take a second to

at the show’s twitter bio

at the show’s twitter bio

- d.

- are u

ing other bitches

ing other bitches

- e.

- I’m a top and I

all the time stop this slander

all the time stop this slander

What exactly this emoji means is hard to formalize. Many compare it to the expression ‘uwu’, but that is even more meaningless to those who are outside of communities who say that. Undoubtedly,  is highly expressive as it clearly resembles a human facial expression. Emojipedia describes as a “face with furrowed eyebrows, a small frown, and large, ‘puppy dog’ eyes, as if begging or pleading. May also represent adoration or feeling touched by a loving gesture.” The website also mentions that it can be “somewhat suggestive” and even “horny” (Burge 2020). As a verb, then,

is highly expressive as it clearly resembles a human facial expression. Emojipedia describes as a “face with furrowed eyebrows, a small frown, and large, ‘puppy dog’ eyes, as if begging or pleading. May also represent adoration or feeling touched by a loving gesture.” The website also mentions that it can be “somewhat suggestive” and even “horny” (Burge 2020). As a verb, then,  means something along the lines of ‘to make the facial expression

means something along the lines of ‘to make the facial expression  ’.

’.

Also interesting is that there is no clear spoken English equivalent of this verb. This is unlike the following cases, where the emojis could be compared to ‘smile(v)’ and ‘laugh(v)’, respectively.

- (69)

- a.

- This made me

saw a

saw a  going nom nom while I was watching tv [int: smile; rabbit]

going nom nom while I was watching tv [int: smile; rabbit]

- b.

- over here

ing at the Yankees [int: laughing]

ing at the Yankees [int: laughing]

This is independent evidence that this emoji does not replace a preexisting word, as there is no word that  could replace. The data in this section show that the

could replace. The data in this section show that the  emoji is no longer just an expressive emoji, but is now a pro-text emoji that represents a stem that is not associated with another English lexical item. The emoji represents a novel lexical item in this way.

emoji is no longer just an expressive emoji, but is now a pro-text emoji that represents a stem that is not associated with another English lexical item. The emoji represents a novel lexical item in this way.

Another example comes from Brazilian Portuguese. In Brazil in the spring of 2022 a video of a lobster went viral online. In this video, the lobster can be seen walking up to and jumping in a pot of boiling oil.8 This video quickly became a meme that was shared in video and GIF form across social media. In the wake of this, the use of the emoji  shown below appeared.

shown below appeared.

- (70)

- a.

- vou

- go-1.sg

- me

- self

- kill

- hj

- today

- 13h

- 13-hours

- ‘I’m going to kill myself today at 1:00pm’

- b.

- vc

- you

- se

- self

- kill

- ‘Kill yourself’

- c.

- Começando

- beginning

- o

- the

- feriadão

- holiday

- com

- with

- cólica

- colic

- vou

- go-1.sg

- me

- self

- kill

- ‘Starting the holiday with colic I’m going to kill myself’

Before this, the lobster emoji can be seen consistently as a pro-text emoji of the category Noun in Brazilian Portuguese tweets. A Twitter search for the  emoji in Portuguese prior to 2022 shows no uses of the emoji as in (70).

emoji in Portuguese prior to 2022 shows no uses of the emoji as in (70).

- (71)

- a.

- Não

- No

- vai

- go-3.sg

- mais

- more

- comer

- eat

- lobster

- tão

- so

- cedo

- soon

- ‘Don’t go eating eating lobster so soon’

- b.

- Vontade

- wish

- de

- of

- comer

- eat

- lobster

- ‘Feel like eating lobster’

- c.

- Só

- only

- vou

- go-1.sg

- parar

- stop

- quando

- when

- acabar

- finish

- a

- the

- lobster

- e

- and

- wine

- ‘I’m only going to stop when the lobster and wine runs out’

In this case the pro-text emoji  is going from representing a Noun to representing a Verb. One informant9 even states that they would pronounce the verbal emoji

is going from representing a Noun to representing a Verb. One informant9 even states that they would pronounce the verbal emoji  as lagostar, which is the nominal form lagosta plus the verbal infinitival suffix -ar, which is what would expected of a verb derived from a noun in Brazilian Portugese. Interestingly, though, the meaning is completely unpredictable from the form, quite unlike a case such as fish (N) and fish (V) in English. Here the meaning is dependent on the shared understanding of the meme among language users.

as lagostar, which is the nominal form lagosta plus the verbal infinitival suffix -ar, which is what would expected of a verb derived from a noun in Brazilian Portugese. Interestingly, though, the meaning is completely unpredictable from the form, quite unlike a case such as fish (N) and fish (V) in English. Here the meaning is dependent on the shared understanding of the meme among language users.

5.1.2 Borrowing of Pro-text emojis

One of the main processes of lexicalization is borrowing from other languages (Hilpert 2019). This can happen with pro-text emojis as well. While it may seem like the same pro-text emoji appearing in different languages is just an instance of two different lexical items in the same language (el  in Spanish and ‘the

in Spanish and ‘the  ’ in English, for example), this is not always the case. There are verifiable instances of pro-text emojis being borrowed from one language to another.

’ in English, for example), this is not always the case. There are verifiable instances of pro-text emojis being borrowed from one language to another.

Take the acronym G.O.A.T., which stands for ‘greatest of all time’ in English and is a very popular superlative on Twitter, especially used to describe athletes (Curtis 2017). Due to this acronym’s orthographic and phonological similarity to the noun ‘goat’, the emoji  is often used as a predicative adjective as well. See the following example.

is often used as a predicative adjective as well. See the following example.

- (72)

- He is the

but I need to see the batfleck in his own movie

but I need to see the batfleck in his own movie

This use of the emoji has been borrowed into Spanish as well, and is very commonly used by Spanish speakers on Twitter.

- (73)

- a.

- Garnacho

- Garnacho

- sabe

- knows

- quien

- who

- es

- is

- el

- the-masc.sg

- ‘Garnacho knows who the G.O.A.T. is’

- b.

- El

- the

- y

- and

- Messi

- Messi

- a

- to

- su

- his

- lado.

- side

- ‘The G.O.A.T. and Messi by his side’

The masculine determiner in these examples is important to note because the word for goat in Spanish is feminine (la cabra), so it is not the case that this is an instance of a pro-text emoji that corresponds to the Spanish word for goat being used in a novel way. Spanish pro-text emojis contain grammatical gender information while not needing an overt gender suffix, which makes sense considering the nature of gender morphology in Spanish, and this gender typically corresponds to the gender of the emoji’s closest synonym. While it may be possible that the emoji is being used in a way closer to a word such as cabrón ‘bastard’, which is masculine, the sentiment of the Spanish tweets containing  is almost entirely positive and is used in the same sports contexts and it is in English.

is almost entirely positive and is used in the same sports contexts and it is in English.

5.1.3 Abbreviations

The lexicalization processes seen above with emojis are not new in any way; no new means of lexicalization need to be posited for pro-text emojis. They are immediately recognizable as similar to lexicalization of other elements, especially those commin in CMC.

Abbreviations in CMC such as lol ‘laugh out loud’ or lmao ‘laugh my ass off’ represent VPs, but they are able to be lexicalized as verbs that can take objects (74), or even nouns (75). (74b) is especially interesting when considering that the possessive pronoun ‘my’ is clearly no longer part of the composition of the verb.

- (74)

- a.

- im on harry styles baldtok im lmaoing

- b.

- my gf just lmao’d at a non-funny tweet.

- (75)

- a.

- Twitter should ban Elon Musk just for the lols

- b.

- Thank you for a mighty LOL. That thread is gold.

This is, of course, not specific to CMC, though. Similar processes lead to apparent redundancies such as ‘ATM machine’, ‘PIN number’, ‘NYI institute’, ‘BIPoC people’, and so forth.