1 Introduction

Final nasalization (henceforth FN) is a process whereby an oral segment becomes a nasal stop in the word-final position. In this paper, we use the term to refer specifically to the final nasalization of stops. Final nasalization (of stops) is phonetically unmotivated, i.e. it does not arise as a consequence of universal articulatory or perceptual tendencies. As such, final nasalization can be deemed an impossible sound change. In Steriade’s (2001) phonetically-grounded theory of phonology (perceptibility map or P-map), this intuition has been further enshrined by rendering final nasalization a synchronically impossible phonological process as well (p. 3).

Nonetheless, synchronic systems that repair the marked configuration of a voiced stop in the word-final position (*D#) with nasalization have been recently reported in Noon (Cangin) (Merrill 2015) and a number of Austronesian languages (Blust 2005; 2016). Merrill (2015) demonstrates that Noon’s final nasalization arose through a combination of sound changes. Specifically, Proto-Cangin prenasalized stops (*ND) denasalized intervocalically (> D / V _ V) and deoralized word-finally (> N / _ #).1

Blust (2005; 2016) reports final nasalization in four Austronesian languages: Kayan-Murik, Berawan dialects, Kalabakan Murut, and Karo Batak. Yet, no traces of prenasalized stops are found to explain it. As such, Blust (2005; 2016) concludes that final nasalization had to operate as a single sound change. Except for Blust’s (2005; 2016) proposals, final nasalization has never been reported to operate as a single sound change.

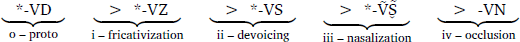

We argue that final nasalization is not a single sound change in these reported cases and results from a combination of changes. In section 3, we demonstrate that in Kayan-Murik (§3.1), Berawan (§3.2), and Kalabakan Murut (§3.3), final nasalization proceeded through a series of steps involving (i) the fricativization of voiced stops, (ii) devoicing of the fricatives, (iii) spontaneous nasalization before voiceless fricatives (plus at least partial voicing of the fricatives), and—finally—(iv) the occlusion of nasalized fricatives to nasal stops. This development is a subtype of the blurring process, as described in Beguš (2019; 2020).2

Following Beguš (2019), we define natural sound changes as following the direction of universal phonetic tendencies, i.e. “phonetic pressures motivated by articulatory or perceptual mechanisms … that passively operate in speech production cross-linguistically and result in typologically common phonological processes” (p. 691).3 (For an overview of phonetic mechanisms, see Garrett & Johnson 2013.) According to this definition, each of the four proposed changes is natural. We discuss the phonetic motivation for each of the changes in section 2. By comparison, a single-change final nasalization as posited by Blust (2005; 2016) would be unmotivated because final nasalization does not reflect a universal phonetic tendency. Moreover, in Kayan-Murik (Beguš 2019), Berawan (Beguš & Dąbkowski 2023), and Kalabakan Murut, the fricativization stages are independently motivated by other diachronic developments and dialectal correspondences, further strengthening our proposal. We suggest that word-final nasalization in Karo Batak might have arisen via analogical extension (§3.4).

In section 4, we extend our account to a set of correspondences in Sioux (Siouan). Lakota word-final voiced stops correspond to voiceless stops or nasals in related languages. We propose that word-final nasalization in Dakota proceeded through an intermediate stage of fricativization. Lakota word-final stop voicing proceeded through an interstage of preconsonantal and pre-pausal fricativization and occlusion. Lastly, in section 5, we note that final nasalization has been reported in three other languages (Hueyapan Nahuatl, Bribri, and Southeastern Tepehuan) and briefly speculate on their diachronic trajectory.

By reducing final nasalization to a series of phonetically motivated sound changes, our results shed light on the role of phonetic naturalness in diachrony and synchrony. We maintain that while phonetically unnatural phonological processes (e.g. Coetzee & Pretorius 2010; Hyman 2001; Beguš et al. 2022; Dąbkowski 2023; Beguš & Dąbkowski 2023; Merrill 2015) may arise via a set of sound changes or analogical extension, regular sound changes are always phonetically motivated.

2 Phonetic motivation for the proposed changes

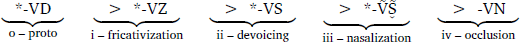

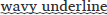

The development of final nasalization we propose for Kayan-Murik (§3.1), Berawan (§3.2), and Kalabakan Murut (§3.3) involves four consecutive changes: (i) fricativization of voiced stops, (ii) devoicing of the fricatives, (iii) spontaneous nasalization before voiceless fricatives (including at least partial voicing of the fricatives), and (iv) occlusion of the nasalized fricatives to nasal stops. This schematized development is given in (1).4 Here, we motivate each change as phonetically grounded.

- (1)

- Final nasalization as a series of changes

2.1 Fricativization

Step I involves the fricativization of voiced stops. The articulation of voiced stops makes conflicting demands: On one hand, airflow must be maintained to produce voicing. On the other hand, the airflow must be obstructed to produce a stop. This competition means that voiced stops are often cross-linguistically avoided. Intervocalically, voiced stops are commonly lenited to fricatives (Kirchner 2001: 102–122; Kümmel 2007: 55–75; Kaplan 2010: 13; Beguš 2018: 101; Beguš 2019; 2020). Beguš (2020) counts about 47 cases of postvocalic fricativization of voiced stops based on approximately 294 languages surveyed in Kümmel (2007). We propose that in Kayan-Murik, Berawan dialects, and Kalabakan Murut, voiced stop fricativization was generalized to any postvocalic position, including word-finally. Evidence supporting this claim is presented in section 3.

2.2 Devoicing

Step II involves (at least partial) word-final devoicing of voiced fricatives. Voiced fricatives, like voiced stops, are articulatorily difficult. Voicing requires the pressure in the oral cavity to be as low as possible, while frication requires it to be as high as possible (Ohala 1983; 1997; Smith 1997; Ohala 2006). Due to these opposing demands, maintaining voicing in fricatives is strenuous. Additionally, voicing in the word-final position is particularly dispreferred, making final devoicing one of the most common phonological processes across many language families (Beguš 2020). As such, final devoicing is attested and articulatory motivated. Note that due to the fricativization in Step I, there are no word-final voiced stops left, so Step II can be stated simply as word-final devoicing, without restricting it to the devoicing of word-final fricatives to the exclusion of word-final stops. This being said, Davidson (2016) shows that English word-final fricatives tend to devoice more often than stops, which suggests that voiced fricatives are particularly difficult to produce word-finally.

2.3 Nasalization

Step III involves spontaneous nasalization of voiceless fricatives. While spontaneous nasalization (henceforth SN) is generally rare typologically, the vicinity of voiceless fricatives constitutes the one environment where this development is attested and phonetically grounded (other such environments include affricates and aspirated stops; Ohala & Ohala 1993). Instances of spontaneous nasalization can be observed e.g. in some developments from Indo-Aryan to Modern Hindi (2) and Early Modern Breton borrowings from French (3). These instances of spontaneous nasalization are recurrent, i.e. they affect large classes of words, but they are not regular.

- (2)

- SN in Indo-Aryan (Grierson 1922; Ohala & Ohala 1993: 240)

- i.

- ii.

- Sanskrit

- Modern Hindi

- pakʂa

- pə̃ŋkʰa

- side

- akʂi

- ãkʰ

- eye

- uččaka-

- ū̃ča

- high

- sarpa-

- sãp

- snake

- (3)

- SN in E Mod Breton (Jackson 1967: 174; Ohala & Ohala 1993: 240)

- i.

- ii.

- French

- E Mod Breton

- maçon

- mançzonner

- mason

- rosse

- rounçe(e)t

- horse

- vis

- binçz, biñs

- screw

Ohala & Ohala (1992; 1993) propose a phonetically grounded explanation for the relationship between high airflow segments, such as fricatives, and perceived nasalization—voiceless fricatives require a greater glottal opening which ends up creating an acoustic effect similar to nasalization. Ohala & Ohala’s (1993) explanation is reproduced verbatim in (4).

- (4)

- High airflow segments →perceived nasality. (Ohala & Ohala 1993: 240)

- i.

- “High airflow segments like voiceless fricatives and aspirated stops require for their production a greater than normal glottal opening (vis-à-vis comparable voiceless segments like voiceless unaspirated stops).”

- ii.

- “This greater than normal glottal opening may spread via assimilation to the margins of adjacent vowels, even though these vowels may remain completely voiced.”

- iii.

- “This slightly open glottis creates acoustic effects due to some coupling between the oral and the subglottal cavities that mimic the effects of coupling of the oral and nasal cavities, i.e., lowered amplitude and increased bandwidth of F1.”

- iv.

- “Vowels that sound nasal to listeners, even though they are not physiologically nasal, can be reinterpreted and produced as nasal, thus precipitating a sound change.”

Ohala & Amador (1981) demonstrate that the spectral effects of fricatives are indeed similar to those of nasalization. Ohala & Amador (1981); Ohala & Ohala (1992) show that speakers of English, Spanish, and Hindi judge fricative-adjacent vowels as significantly more nasal than vowels not adjacent to fricatives. Khattab & Al-Tamimi & Alsiraih (2018) demonstrate that Iraqi Arabic pharyngeals exhibit various degrees of nasalization when combined with nasals and suggest that their variable realization may act as a precursor for sound change.

In particular, nasality shows a particularly strong connection to glottal articulation. The close affinity between the two classes of sounds has been dubbed rhinoglottophilia by Matisoff (1975). Ohala’s (1975) summary of its phonetic basis is given in (5).

- (5)

- Phonetics of rhinoglottophilia (Ohala 1975: 303)

- “[h] may produce an effect on vowels that ‘mocks’ that of nasalization. Because of the open glottis during phonation accompanying an [h] (or breathy-voice), the spectrum of the vowel will be changed in the following ways: there will be upward shifting of the formants, especially F1 …, increased bandwidth of the formants, presence anti-resonances in the spectrum and an overall lowering of the amplitude of the vowel … This is identical to the effect of nasalization on vowels. Articulatory re-interpretation may occur, i.e., actual nasalization may be produced on the vowel” (quoted in Blevins & Garrett 1993: 220–1).

The rhinoglottophilic connection between nasals and glottals is reflected in their frequent synchronic and diachronic connections. For example, Johnson et al. (2019) show that Thai non-high vowels spontaneously nasalize after the glottal consonants h and ʔ. Blevins & Garrett (1992; 1993) propose that Proto-Ponapeic geminates developed into Ponapean nasal-stop sequences through a stage of preaspiration (*Tː > *hT > NT), demonstrating, if correct, that spontaneous nasalization can give rise to a regular sound change (6).

- (6)

- Rhinoglottophilia in Ponapean (Blevins & Garrett 1993: 215–6)

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

- Pre-Proto-Ponapeic

- Proto-Ponapeic

- Pre-Ponapean

- Ponapean

- *ič̣č̣a

- *ihč̣a

- *iṇč̣a

- ṇč̣a

- blood

- *pap-pap

- *pah-pap

- *pam-pap

- pam-pap

- swimming

While we propose that in Austronesian and Dakota, spontaneous nasalization was triggered by all voiceless fricatives (not only h), the phonetics of rhinoglottophilia is similar to that of other cases of spontaneous nasalization, lending indirect support to our account.

Finally, we speculate that preaspiration may be an intermediate step linking voiceless fricatives to nasalization. Gordeeva & Scobbie (2010: 169–170) show that female speakers of Scottish Standard English (SSE) often produce word-final voiceless fricatives with a considerable preaspiration. For example, grass may be realized as [gɹahs]. SSE preaspiration affects only fricatives; stops are not preaspirated. Thus, we suggest that final nasalization in the cases at hand may have arisen via the intermediate step of preaspiration. Word-final voiceless fricatives first preaspirated, and then preaspiration gave rise to rhinoglottophilic nasalization, i.e. VS > VhS > ṼS̬̃ / _ #. Positing this intermediate stage has two advantages. First, it connects spontaneous nasalization to preaspiration, which has been argued to give rise to nasalization as a regular sound change (Blevins & Garrett 1993). Second, since fricative preaspiration has been reported word-finally (Gordeeva & Scobbie 2010: 170), it helps explain why voiced stops nasalized only in the word-final position.

2.4 Occlusion

Step IV involves the occlusion of nasalized fricatives. Frication requires high oral air pressure while nasalization consists of lowering the velum and redirecting a part of the pulmonic airflow through the nasal cavity. Ohala (1975); Ohala & Ohala (1993) suggest that the remaining oral air pressure might be too low to produce a nasal fricative. This makes nasal fricatives very articulatorily difficult (and typologically rare). As such, a change away from nasalized fricatives is to be expected.

The development from spontaneously nasalized fricatives to nasal stops might have proceeded along several different paths. First, nasalized fricatives could have developed into nasal stops as a single sound change, i.e. ṼS̬̃ > VN. While we are not aware of previously reported instances of this change, we speculate it might be due to the overall typological rarity of nasal fricatives.

Second, the occlusion of nasalized fricatives might have itself involved a combination of two changes: fricative approximantization and approximant occlusion, i.e. ṼS̬̃ > ṼR̃ > VN. The change of a fricative into an approximant is very well attested, with many reports of unconditioned β, v > w; ð > l, ɾ (> r); ʝ, ʓ > j; and ɣ > w (Kümmel 2007: 78–88).5 In the scenario at hand, the fricatives undergoing the change are at least partially nasalized. The aerodynamic difficulty involved in the production of nasalized fricatives (Ohala 1975; Ohala & Ohala 1993) makes their approximantization all the more likely. Indeed, one of the possible implementations of Scottish Gaelic phonologically nasal fricatives is as nasal approximants (Warner et al. 2015).6

In this scenario, the approximantization of nasal fricatives is then followed by the occlusion of nasal approximants. This again is a typologically attested change. For example, the Medieval Polish nasal vowel ã (< Proto-Slavic *ę and *ǫ) developed into the Standard Polish ɔw̃ (and ɛw̃,7 following a conditioned split). The diphthongized ɔw̃ further developed into ɔm in Greater Poland (Stieber 1973: 129; Baranowska & Kaźmierski 2020; Kaźmierski & Szlandrowicz 2020). In A’ingae, nasal stops in the coda position nasalized the preceding vowel and underwent deletion. Additionally, most instances of ɲ and some instances of m go back to sequences of *nj and *nʋ (Sanker & AnderBois t.a.). Regardless of the relative ordering of the two changes, A’ingae developments testify to the occlusion of nasalized approximants: *Vnj (> *Ṽj) > Ṽɲ; *Vnʋ (> *Ṽʋ) > Ṽm. In Samoyed and in Lappish, word-initial *j- became ɲ- if a nasal consonant is present later in the word, i.e. *j- > ɲ- / # _ VN (Collinder 1960: 63; Mikola 1988: 228f; Kümmel 2007: 159). In Kamassian, *w- changed into m- in the same environment, i.e. *w- > m- / # _ VN (Collinder 1960: 66; Mikola 1988: 228f; Kümmel 2007: 159). Both changes presumably resulted from nasal spreading with nasalized approximants as the intermediate stage, i.e. *j- > * j̃- > ɲ- and * w- > * w̃- > m-.

Finally, the step of occlusion might have proceeded as follows: (i) the spontaneously nasalized vowel unpacks into an oral vowel followed by a nasal stop, (ii) the postnasal fricative hardens to a stop, (iii) the resulting stop is ultimately deleted. This sequence of changes can be schematized as ṼS̬̃ > VNS̬ > VND > VN. The unpacking is attested in the development of Portuguese nasal vowels into sequences of oral vowels followed by a nasal stop in Portuguese-based creoles. E.g., in Casamancese Creole (Biagui & Quint 2013), kõˈtar > konta ‘tell’ (p. 42), ũ > uŋ ‘one’ (p. 43), ˈsĩku > siŋku ‘five’ (p. 43). In Papamientu (Birmingham, Jr. 1970), ʒɐ̃ˈtar > žaːnta ‘eat’ (p. 6), tɐ̃ˈbɐ̃j̃ > taːmbɛ ‘also, too’ (p. 6), ˈbõ > bõŋ ‘good’ (p. 34). (Yet another example is the previously discussed development of the Medieval Polish ã into the Greater Poland Polish ɔm.) The latter sequence of fricative hardening followed by stop deletion is, among others, a familiar development from German, e.g. Germanic *tanθ > Old High German zand > German Zahn ‘tooth.’

In sum, we propose that final nasalization in Austronesian and Siouan arose from a sequence of sound changes which are natural, i.e. motivated by facts of speech production and perception. First, voiced stops underwent fricativization. Second, the fricatives devoiced. Third, voiced fricatives triggered spontaneous nasalization. Finally, fricatives in the vicinity of nasalization occluded to nasal stops. Nasal occlusion might have involved an intermediate approximantization, proceeded via post-nasal hardening, or consisted of a single sound change. Our accounts are compatible with any of the three scenarios. As such, we remain agnostic about the possible incremental changes involved in the final step.

3 Final nasalization in Austronesian

Now we present the details of our account of final nasalization in four Austronesian languages: Kayan-Murik, Berawan dialects, Kalabakan Murut, and Karo Batak. A previous account of the data has been proposed by Blust (2005; 2016), who argues that final nasalization took place as a single sound change, without any intervening steps. We take a different stance. While it is true that final voiced stops in proto-languages of the four languages with final nasalization correspond to observed final nasals (as presented in Blust 2016), reflexes of voiced stops in other positions suggest that additional steps were involved in the development of final nasalization.

Beguš’s (2019); Beguš & Dąbkowski’s (2023) work on two of the four languages shows that intermediate stages of fricativization are independently necessary to account for the phonologically unnatural developments. Beguš (2019) demonstrates that Murik post-nasal devoicing proceeded through a change of voiced stops to voiced fricatives. Beguš & Dąbkowski (2023) show that Berawan intervocalic devoicing involves a similar step of fricativization. Our account builds on their findings and provides additional language-internal and dialectal data supporting the claim that stop fricativization preceded final nasalization. Beguš (2019); Beguš & Dąbkowski (2023) also argue that the occlusion of fricatives back to stops is independently attested in both Berawan and Murik, which bears high resemblance to the occlusion of nasalized fricatives in the present case.

3.1 Kayan-Murik

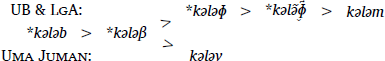

Let us first take a look at the Kayan-Murik (KM) data. Kayan-Murik (or Kayanic) is a branch of Austronesian languages spoken in Borneo, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Blust (2016) reports (at least) two dialects to have undergone final nasalization: Uma Bawang (UB) and Long Atip (LgA) dialects of Kayan (7). Proto-Kayan-Murik (PKM) final *-b and *-d (7a) correspond to Uma Bawang and Long Atip -m and -n (7b-c). In Uma Juman (UJ), the PKM word-final *-b fricativizes to -v and *-d lenites to -r (7d). While the data is limited, Blust (2016) observes that Murik seems to have devoiced PKM *-b, but nasalized PKM *-d (7e).

- (7)

- Word-final developments of PKM voiced stops (Blust 2016)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- e.

- Proto-KM

- Uma Bawang

- Long Atip

- Uma Juman

- Murik

- *kələb

- kələm

- kələm

- kələv

- kələp

- tortoise

- *añud

- añun

- añun

- añur

- añun

- adrift

Word-initially, the voiced stops *d- and *b- do not undergo any changes in Uma Juman, Uma Bawang, or Long Atip. Word-internally, *-d- lenites to -r- in all four languages. Crucially, Uma Juman intervocalic *-b- fricativizes to -v-. In Murik, word-initial *d- lenites to l-; Murik non-final *b does not change. These developments are summarized in (8).

- (8)

- Summary of KM developments (Blust 2005: 259; Blust 2013; Blust 2016)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- Proto-KM

- UB & Lga

- Uma Juman

- Murik

- *b-

- b-

- b-

- b-

- *-b-

- -v-

- -v-

- -b-

- *-b

- -m

- -v

- -p

- *d-

- d-

- d-

- l-

- *-d-

- -r-

- -r-

- -r-

- *-d

- -n

- -r

- -n

Additionally, Murik also shows phonetically unnatural post-nasal devoicing (henceforth PND), whereby Proto-Kayan-Murik voiced stops devoice after nasal consonants (8).

- (9)

- Murik post-nasal devoicing (Blust 2005: 259–262; Blust 2013: 668)

- a.

- b.

- Proto-KM

- Murik

- *kelembit

- kələmpit

- shield

- *lindem

- lintəm

- dark

- *nɟʝi

- ncçi

- one

- *tuŋgan

- tuŋkan

- dibble stick

The development of unnatural post-nasal devoicing in Murik and twelve other languages receives extensive treatment in Beguš (2019), who demonstrates that post-nasal devoicing always arises from a sequence of (at least) three changes, in the course of which (i) “[a] set of segments enters complementary distribution,” (ii) “[a] sound change occurs that operates on the changed/unchanged subset of those segments,” and (iii) “[a]nother sound change occurs that blurs the original complementary distribution” (p. 735). Beguš (2019) refers to a combination of sound changes that fit that description as the blurring process. Changes involved in the post-nasal devoicing in Murik are summarized in (10). For more on the mechanics and subtypes of the blurring process, see e.g. Beguš (2018; 2019; 2020; 2022); Beguš et al. (2022).

- (10)

- Development of PND in Murik (based on Beguš 2019: 725–726)

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- iv.

- Pre-PKM

- Proto-KM

- Proto-KM

- Murik

- *b-

- *β-

- *β-

- b-

- *VbV

- *-β-

- *-β-

- -b-

- *Nb-

- *-b-

- *-p-

- -p-

- *d-

- *ð-

- *ð-

- l-

- *VdV

- *-ð-

- *-ð-

- -r-

- *Nd-

- *-d-

- *-t-

- -t-

First (10i), voiced stops *b and *d fricativize to *β and *ð if not directly preceded by a nasal. Second (10ii), all the remaining (i.e. post-nasal) voiced stops devoice. Finally (10iii), word-initial and intervocalic *ð lenites to l- and -r- respectively,8 and *β occludes to b. This combination of sound changes in Murik gives rise to the appearance of unnatural post-nasal devoicing. However, due to the preceding fricativization (*b, *d > *β, *ð) in other positions, the devoicing of stops was unconditioned (and hence phonetically natural) at the time of its actuation.

Evidence for the proposed trajectory of development (10) comes from the reflexes of Pre-PKM *d. The alveolar stop lenites word-initially and intervocalically but devoices post-nasally, suggesting a stage of complementary distribution. The lenited reflexes point to a stage of fricativization since *d is likely to develop into l and r through an interstage with *ð (Beguš 2019).

We extend Beguš’s (2019) argument to propose that Uma Bawang and Long Atip underwent a similar fricativization. Unlike in Murik however, the UB and LgA voiced stops develop into voiced fricatives in all post-vocalic positions, including word-finally. This reconstruction is supported by evidence from the closely related dialect of Uma Juman. Uma Juman lacks final nasalization, but voiced stops develop into voiced fricatives in all post-vocalic positions, including word-finally (7d): PKM *-b develops into *-β > -v and PKM *-d develops into -r, likely through an interstage with *-ð. In Uma Bawang and Long Atip, the word-final fricatives devoice, creating a precondition for spontaneous nasalization. Finally, nasalized fricative occlude to nasal stops. The developments of PKM word-final *-b and *-d are exemplified in (11).

- (11)

- Developments of PKM word-final voiced stops in UB, LgA, and UJ

- a.

- Developments of Proto-Kayan-Murik *-b

- b.

- Developments of Proto-Kayan-Murik *-d

We observe that Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) did not have phonemic non-strident fricatives (except for *h) (Blust 2013: 585–6, 591–3), and we have no reasons to believe that the immediate ancestors of Kayan-Murik, Berawan (§3.2), Kalabakan Murut (§3.3), or Karo Batak (§3.4) had the non-strident phonemic fricatives either. As such, the stages of fricativization and devoicing did not result in any mergers with *β, *ð, *ɣ, or *ɸ, *θ, *x.

Proto-Malayo-Polynesian had two fricatives *s and *h (Blust 2013: 591–3). The alveolar fricative *s does not trigger spontaneous nasalization. However, *s is a sibilant. Sibilants have a higher amplitude and pitch than non-sibilant fricatives. As a consequence, sibilants and non-sibilants are often found to pattern differently. Our discussion of Austronesian fricatives is restricted to the non-sibilant ones, to the exclusion of the *s.

Finally, PMP had the non-strident glottal fricative *h (Blust 2013: 591–3). In most Malayo-Polynesian languages, word-final *-h has been lost (Blust & Trussel & Smith 2023). The PMP word-final *-h does not have nasal reflexes, suggesting that it had been lost in the daughter languages before the sequence of changes in (1) took place.

In sum, we propose that final nasalization in Uma Bawang and Long Atip proceeded through the interstage of fricativization. Fricativization is independently motivated by the facts of Murik post-nasal devoicing and synchronically attested in the closely related Uma Juman.

3.2 Berawan

The second language with reported final nasalization that shows independent evidence of fricativization of voiced stops is Berawan. Berawan is a group of closely related dialects spoken in the Malaysian state of Sarawak. Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) word-final voiced stops (12a) correspond to nasal stops in the Berawan dialects of Long Terawan (12b), Batu Belah (12c), and Long Jegan (12d).

- (12)

- Word-final developments of PMP voiced stops (Blust 2016)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- Proto-MP

- Long Terawan

- Batu Belah

- Long Jegan

- *asəb

- cam

- cam

- cam

- smoke

- *tumid

- tumin

- tumiŋ

- tomən

- heel

Intervocalically, the Berawan voiced stops undergo other unusual developments. The Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *-g- devoices to -k-; *-b- also devoices and velarizes to -k-. PMP *-d- does not devoice, but rather lenites to -r-. Word-initially, the three voiced stops do not undergo any changes. Some of these developments are exemplified in (13). The developments of voiced stops in all positions are summarized in (14).

- (13)

- Devs. of PMP voiced stops elsewhere. (Blust 2013; Burkhardt 2014: 387–395)

- a.

- b.

- Proto-MP

- Batu Belah

- *bibi

- biki

- edge

- *bəlibiəw

- bəlikiw

- rat

- *bigiu

- bikiw

- typhoon

- *gigun

- gikuŋ

- cloud

- *dibiən

- dikin

- parent-in-law

- (14)

- Summary of Berawan developments. (based on Blust 2016; Burkhardt 2014: 273)

- a.

- b.

- Proto-MP

- Berawan

- *b-

- b-

- *-b-

- -k-

- *-b

- -m

- *d-

- d-

- *-d-

- -r-

- *-d

- -n

- *g-

- g-

- *-g-

- -k-

- *-g

- -ŋ

The phonetically unnatural intervocalic devoicing receives treatment in Beguš & Dąbkowski (2023), who propose that like the post-nasal devoicing in Murik, Berawan’s intervocalic devoicing is also the outcome of a sequence of sound changes (the blurring process) (15).

- (15)

- Invervocalic devoicing in Berawan (Beguš & Dąbkowski 2023)

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

- iv.

- Proto-MP

- Pre-Berawan

- Pre-Berawan

- Pre-Berawan

- Berawan

- *b-

- *b-

- *b-

- *b-

- b-

- *-b-

- *-β-

- *-ɸ-

- *-x-

- -k-

- *d-

- *d-

- *d-

- *d-

- d-

- *-d-

- *-ð-

- *-r-

- *-r-

- -r-

- *g-

- *g-

- *g-

- *g-

- g-

- *-g-

- *-ɣ-

- *-x-

- *-x-

- -k-

First (15i), voiced stops fricativize intervocalically. Second (15ii), *ð lenites to *r,9 while the other voiced fricatives devoice unconditionally. Third (15iii), the labial fricative *ɸ velarizes to *x. The velarization of labial fricatives is typologically attested (Kümmel 2007: 222) and phonetically motivated (because non-strident fricatives are perceptually confusable; Redford & Diehl 1999). Finally (15iv), the remaining *x occludes to k. The unconditioned change of *x > k has been reported e.g. from Proto-Tacanan to Cavineña (Key 1968). A similar change of *x > kʰ has been reported from Proto-Tai to several Tai languages (Li 1977: 207–214).

Several pieces of evidence support Beguš & Dąbkowski’s (2023) reconstruction. First, the lenition of *-d- to -r- likely went through an intermediate step of *-ð-, pointing to a stage of fricativization. Second, the velarization of labial fricatives is more common than velarization of labial stops (Kümmel 2007: 221–2). Third, unless an interstage of intervocalic fricativization is postulated, the changes of devoicing and velarization cannot be ordered. Ordering devoicing before velarization incorrectly predicts the velarization of Pre-Berawan *p > ×k. Ordering velarization before devoicing incorrectly predicts the velarization of Pre-Berawan word-initial *b- > ×g-. The only way out of the ordering paradox is to say that the velarization of stops (an already unusual change) occurred only intervocalically. This is highly implausible since the place of articulation of stops is best articulatorily cued specifically between vowels. For a full exposition of the argument, see Beguš & Dąbkowski (2023).

We extend Beguš & Dąbkowski’s (2023) analysis in proposing that—similarly to Kayan-Murik—Berawan fricativization takes place in all post-vocalic positions, including word-finally. Next, we reconstruct that the fricatives devoice. Note that the unconditioned devoicing of fricatives in Berawan is independently motivated in the account of Berawan’s intervocalic devoicing (15ii). Finally, word-final fricatives nasalize and occlude, yielding apparent word-final nasalization. This development in Long Terawan is exemplified in (16).10

- (16)

- Developments of Pre-Berawan word-final voiced stops in Long Terawan

- a.

- Development of Pre-Berawan *-b

- *cab > *caβ > *caɸ > *cãɸ̬̃ > cam

- b.

- Development of Pre-Berawan *-d

- *tumid > *tumið > *tumiθ > *tumĩθ̬̃ > tumin

In Berawan, only the word-final voiceless fricatives trigger spontaneous nasalization. There are at least three ways in which one may try to account for this fact. First, Berawan devoicing might have taken place in two steps, separated by spontaneous nasalization. At first, word-final fricatives devoice. Next, voiceless fricatives nasalize. Lastly, devoicing affects all other fricatives.

Second, it may be the case that only word-final fricatives nasalized because articulatory cues in the final position are the weakest. i.e., word-final fricatives and adjacent vowels are most readily misperceived as nasalized (via the mechanism of Ohala & Amador 1981).

Third, Berawan final nasalization might have involved an intermediate stage of fricative preaspiration, as discussed in subsection 2.3. In Standard Scottish English, only word-final fricatives preaspirate (Gordeeva & Scobbie 2010: 170). If the same facts held of Berawan preaspiration, only word-final fricatives would be then affected by rhinoglottophilic nasalization. Due to a lack of additional evidence, we do not take a strong stance on why only word-final fricatives nasalize in Berawan.

In sum, we propose that final nasalization in Berawan arose through the intermediate stage of voiced stop fricativization. The interstage of fricativization is motivated independently by the facts of Berawan intervocalic devoicing.

3.3 Kalabakan Murut

In two out of four reported languages with final nasalization, a stage of voiced stop fricativization must be reconstructed for reasons completely independent of final nasalization. In Kayan-Murik, the interstage of fricativization accounts for phonetically unnatural post-nasal devoicing (Beguš 2019). In Berawan, fricativization explains the unusual devoicing of stops between vowels (Beguš & Dąbkowski 2023). In one additional language—Kalabakan Murut—there exists strong internal and dialectal evidence that final nasalization arises through an interstage with fricativization as well.

Kalabakan Murut (MKal) is a language of the Sabahan branch of Austronesian spoken in Malaysia. Blust (2016) reports that Kalabakan Murut underwent final nasalization (17). Proto-Murutic (PMur) final voiced stops *-b, *-d, and *-g (17a) develop to -m, -n, and -ŋ (17b). Notably, Proto-Murutic *-b-, *-d-, and *-g- yield -b-, -r-, and -h- intervocalically at morpheme boundaries when followed by a vowel-initial prefix (17c). Word-initially, voiced stops do not change. The Kalabakan Murut developments are summarized in (18).

- (17)

- Developments of Proto-Murutic voiced stops (Blust 2016)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- PMurutic

- MKal _ #

- MKal V _ -V

- *takub

- an-akum (av.npst)

- takub-on (ov.npst)

- catch

- *takod

- an-akon (av.npst)

- tokor-on (ov.npst)

- climb tree

- *ipag

- aŋ-ipaŋ (av.npst)

- ipah-in (lv.npst)

- call

- (18)

- Summary of Kalabakan Murut developments (based on Blust 2016)

- a.

- b.

- PMurutic

- MKal

- *b-

- b-

- *-b-

- -b-

- *-b

- -m

- *d-

- d-

- *-d-

- -r-

- *-d

- -n

- *g-

- g-

- *-g-

- -h-

- *-g

- -ŋ

To account for the Kalabakan Murut reflexes, we propose that—like in Kayan-Murik and Berawan—the Proto-Murutic voiced stops (19) fricativize word-medially and finally, i.e. in all post-vocalic positions (19i). The reflexes of Proto-Murutic *d and *g point directly to this interstage. Intervocalically, *d > *ð lenites to r. The velar fricative *g > *ɣ unconditionally devoices to *x. The other fricatives devoice word-finally (19ii). Word-final fricatives spontaneously nasalize (19iii). At last, fricatives occlude, yielding word-final nasal stops (19iv). In Karo Batak (discussed briefly in §3.4), the voiceless velar fricative x is word-finally in free variation with voiceless glottal fricative h (Woollams 1996: 17), pointing to an ongoing sound change x > h. We propose that this debuccalization takes place in Kalabakan Murut as well.

- (19)

- Kalabakan Murut developments step-by-step

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

- iv.

- PMurutic

- Pre-MKal

- Pre-MKal

- Pre-MKal

- MKal

- *b-

- *b-

- *b-

- *b-

- b-

- *-b-

- *-β-

- *-β-

- *-β-

- -b-

- *-b

- *-β

- *-ɸ

- *-ɸ̬̃

- -m

- *d-

- *d-

- *d-

- *d-

- d-

- *-d-

- *-ð-

- *-r-

- *-r-

- -r-

- *-d

- *-ð

- *-θ

- *-θ̬̃

- -n

- *g-

- *g-

- *g-

- *g-

- g-

- *-g-

- *-ɣ-

- *-x-

- *-x-

- -h-

- *-g

- *-ɣ

- *-x

- *-x̬̃

- -ŋ

This proposed sequence of developments yields the synchronic alternation between final -m, -n, and -ŋ (17b) and medial -b-, -r-, and -h- (17c), which directly points to an interstage with frication, e.g. aŋ-ipaŋ ∼ ipah-in or an-akon ∼ tokor-on.

In Kalabakan Murut, only the word-final *-x spontaneously nasalized, even though the Proto-Murutic word medial *-g- had also fricativized to *-x-. It is possible that, like in Berawan, only the final fricatives triggered spontaneous nasalization because articulatory cues in the final position are least robust (i.e. word-final fricatives and adjacent vowels are most readily misperceived as nasalized). This scenario is particularly plausible if the velar fricative had debuccalized before nasalizing, i.e. *-x > *-h > *-h̃. Word-finally, the realization of h is very weak, which may have further precipitated reinterpreting the glottal fricative cues as nasal.

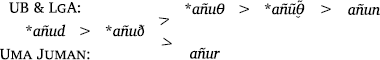

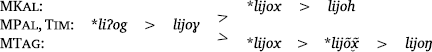

The reconstruction of the stages of fricativization (19i) and word-final devoicing (19ii) is further supported by data from closely related dialects (Lobel 2013). In Murut Paluan (MPal) and Murut Timugon (MTim), the Proto-Greater Murutic (PGMur) voiced velar stop *-g develops word-finally into the voiced velar fricative -ɣ (e.g. PGMur *liʔog ‘neck’ > MPal, MTim lijoɣ). In Murut Tagol (MTag), the fricative further debuccalizes to -h (> MTag lijoh). The Kalabakan Murut cognate shows word-final nasalization (> MKal lijoŋ). The developments of the Proto-Murutic voiced stops in the word-final position are illustrated in (20).

- (20)

- Developments of Proto-Murutic word-final voiced stops

- a.

- Development of PMur *-b in Kalabakan Murut

- *takub > *takuβ > *takuɸ > *takũɸ̬̃ > (t)akum

- b.

- Development of PMur *-d in Kalabakan Murut

- *takod > *takoð > *takoθ > *takõθ̬̃ > (t)akon

- c.

- Devs. of PGMur *-g in MKal, Pal, Tim, & Tag (based on Lobel 2013)

In sum, three out of the four Austronesian languages with final nasalization reported in Blust (2016) show strong evidence for an interstage in which voiced stops develop into fricatives. In two of these (Kayan-Murik and Berawan), the evidence for a stage with fricativization is independent of final nasalization data. In Kalabakan Murut, word-final nasals still alternate with an approximant r (< *ð) and a voiceless fricative h (< *x < *ɣ), pointing directly to a stage of fricativization. Thus, the three Austronesian languages—we argue—had a stage of word-final voiced stops surfacing as fricatives, which is precisely the environment where spontaneous nasalization is phonetically motivated (§2). We propose that the fricatives devoice word-finally (if not already devoiced as in Berawan). Next, word-final rimes nasalize (VS > ṼS̬̃) due to the perceptual similarity between fricative-adjacent and nasalized vowels (Ohala & Amador 1981). Finally, the nasalized fricatives occlude to nasal stops.

3.4 Karo Batak

Finally, we turn to discuss the case of Karo Batak, a Northern Batak language spoken by the Karo people in North Sumatra. Blust (2016) reports that Proto-Batak (PB) (21a) word-final voiced stops devoice in Southern Batak (SB), including Toba Batak (TB) (21b), but nasalize in Northern Batak (NB), including Karo Batak (KB) (21c). However, in Karo Batak, no direct evidence for an interstage with frication exists.

- (21)

- Word-final developments of Proto-Batak voiced stops (Blust 2016)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- Proto-Batak

- Toba Batak

- Karo Batak

- KB affixed

- *tərəb

- tərəm

- mass of people

- kə-tərəm-ən

- receive many

- guests at once

- *alud

- alut

- alun

- massage

- ŋ-alun-i

- to massage

- *dələg

- dolok

- dələŋ

- mountain

There are three possible explanations for final nasalization in Karo Batak. First, final nasalization in Karo Batak could have resulted from a single sound change (22) (as proposed by Blust 2016), which would distinguish Karo Batak from the other languages discussed above, where evidence for intermediate stages is present.

- (22)

- Hypothesis one: KB final nasalization as a single sound change

- o.

- i.

- Proto-Batak

- Karo Batak

- *tərəb

- tərəm

- *alud

- alun

- *dələg

- dələŋ

Second, Karo Batak FN could have arisen from the same combination of sound changes as in the other Austronesian languages (23). In this familiar scenario, post-vocalic stops fricativize (23i), devoice word-finally (23ii), spontaneously nasalize (23iii), and lastly occlude (23iv).

- (23)

- Hypothesis two: KB final nasalization via a series of changes

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

- iv.

- Proto-Batak

- Pre-KB

- Pre-KB

- Pre-KB

- Karo Batak

- *tərəb

- *tərəβ

- *tərəɸ

- *tərə̃ɸ̬̃

- tərəm

- *alud

- *aluð

- *aluθ

- *alũθ̬̃

- alun

- *dələg

- *dələɣ

- *dələx

- *dələ̃x̬̃

- dələŋ

In other positions, KB fricatives undergo occlusion without devoicing or nasalization, i.e. *-b- > *-β- > -b-, *-d- > *-ð- > -d-, and *-g- > *-ɣ- > -g-. We reconstruct this sequence of sound changes in Berawan, Kalabakan Murut, and Murik as well. For example, in Murik and Kalabakan Murut, the intervocalic labial fricative *β (< *b) occludes back to b. In Berawan, occlusion occurs in the velar series (*b, *g > *x > k). What distinguishes Karo Batak from the other languages is that in KB, fricatives occlude in all places of articulation, blurring the evidence for the initial development of frication.

While we are unaware of direct evidence for the sequence of changes outlined above, languages closely related to Karo Batak exhibit spontaneous nasalization of fricatives, which is precisely the step we are proposing in the history of Karo Batak’s final nasalization. These developments further support our incremental scenario. For example, NB picat ‘to squeeze sth., to massage breasts’ corresponds to TB, Simalungun pisat and and Angkola Mandailing (AnMa) piñat (Adelaar 1981: 15). The AnMa mañabia, manabia is a borrowing from Sanskrit vāyavya (Adelaar 1981: 16). Sanskrit lakṣa ‘hundred thousand’ has been borrowed into NB as laksa ‘ten thousand’ and becomes TB laso and in AnMa laño (Adelaar 1981: 15). These examples reveal the directionality of change—in AnMa, fricatives (and approximants) have undergone spontaneous nasalization.

Finally, Karo Batak’s final nasalization could also have resulted from analogical extension. While the Proto-Batak final voiced stops *-b, *-d, and *-g correspond to Karo Batak -m, -n, and -ŋ, these nasalized final stops do not alternate (21d). For example, PB *tərəb ‘mass of people’ yields KB tərəm, but when the stop appears in a non-final position, it also surfaces as a nasal, e.g. kə-tərəm-ən ‘receive many guests at once.’ This stands in contrast with Kalabakan Murut which preserves a synchronic alternation (17b-c), e.g. aŋ-ipaŋ ∼ ipah-in or an-akon ∼ tokor-on.

While by itself, this piece of evidence does not necessarily mean nasalization has to be analogical, evidence from the related Toba Batak points to a stage which could have been its precursor. Toba Batak has a sandhi phenomenon whereby word-final nasal (24a) and oral voiced stops merge to oral stops before word-initial stops (24b-c).

- (24)

- Sandhi in Toba Batak (Blust 2013: 250)

- a.

- minum

- to drink

- b.

- minub (bir)

- to drink (beer)

- c.

- minup (purik)

- to drink (rice water)

If the same sandhi phenomenon was a stage in Karo Batak, the word-final nasal variant could have arisen via generalization. In this scenario, *N D- and *-D D- both merge to *-D D- in sandhi. Then, nasal articulation gets analogically extended from the sandhi merger position. This hypothesis is illustrated in (25). The analogically extended form is marked with  .

.

- (25)

- Hypothesis three: KB FN by analogy (based on Blust 2016; Adelaar 1981)

- o.

- i.

- Proto-Batak

- Pre-KB

- *tanem D- :

- *taneD D- :

- *tanem ::

- *tanem ::

- to bury

- *tərəb D- :

- *tərəD D- :

- *tərəb

- mass of people

In sum, it is difficult to assess which of the three scenarios actually gave rise to final nasalization in KB. Nonetheless, given the evidence from related languages and the plausibility of analogical extension, it is likely that Karo Batak FN did not arise from a single sound change.

Finally, while we propose that the sequence of sound changes in (1) took place in three (or four) Austronesian languages, we note that sequence (1) is not shared by their common ancestor. We also do not have any evidence suggesting that final nasalization is an areal feature. As such, we consider final nasalization to be an independent development in each of the four Austronesian languages in question.

It has been often observed that related languages tend to undergo the same changes independently of each other (Bowern 2015). While we do not have a definitive answer as to why, we speculate that cases of similar developments across related but non-interacting languages might be due to information-theoretic (Cohen Priva 2017), phonological (Fruehwald 2013), or phonetic (Ohala & Ohala 1993) precursors already present in the mother language, which constitute preconditions favoring certain pathways of change.

4 Final voicing and nasalization in Sioux

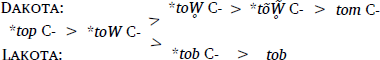

Finally, we turn to two related word-final developments in Lakota and Dakota, two varieties of Sioux (Siouan). In Lakota, Proto-Siouan voiceless stops undergo phonetically unnatural final voicing. In Dakota, they develop word-finally into nasals. We propose that the Lakota final voicing results from a combination of changes with an interstage of fricativization in weak positions. In Dakota, the fricativization is a precursor to spontaneous nasalization.

Lakota is a Mississippi Valley Siouan language spoken mainly in North and South Dakota. Lakota voiceless /p/, /t/, and /k/ voice to [b], [l], and [g] in codas. In addition to voicing, the coronal /t/ also develops into the sonorant [l]. Lakota coda voicing is a static phonotactic restriction (26a) as well as an active phonological alternation. As an active alternation, it can be observed, for example, between vowel-final citation forms where the medial stop syllabifies as an onset (26b) and forms with apocope of final vowels (26c) or in a variety of morphophonological environments where the final vowel is dropped, such as reduplication (26d) and compounding (Rood 2016; Riggs 1893; Blevins & Egurtzegi & Ullrich 2020). The process of coda voicing occurs in native Siouan words as well as recent borrowings, testifying to its productivity (Blevins & Egurtzegi & Ullrich 2020).

- (26)

- Lakota stop voicing in codas (Blevins & Egurtzegi & Ullrich 2020: 301, 303)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- coda

- medial onset

- apocope

- reduplication

- ób.tu

- to be among

- tó.pa

- tób

- tob.tó.pa

- four

- -kel

- kind of

- na.pó.tA

- na.pól

- na.pól.potA

- to wear sth. out

- with the feet

- ka.ȟlóg.ʔo.štaŋ.pi

- vest

- šó.kA

- šog

- šog.šó.kA

- to be thick

On the surface, coda voicing is an unnatural alternation. Nonetheless, its origin be can be illuminated by comparative data which suggest that Lakota’s final voicing is in fact a result of three sound changes. Previous accounts which posit a complex history for Lakota final voicing include Rankin (2001); Rood (2016), who reconstruct Lakota’s voiced stops as going back to nasals. We propose an alternative path of development, with voiced stops arising from the occlusion of voiced fricatives. We argue that our reconstruction better captures the variety of outcomes in the individual daughter languages.

First, consider the alveolar coda reflex -l. The Lakota l goes back to the Proto-Siouan “obstruent resonant” *R (Rankin & Carter & Jones 1998; Rankin et al. 2015). In the daughter languages, *R (27a) yields variously r (27b), l (27c), d (27d), n (27e), or t (27f).

- (27)

- Reflexes of Proto-Siouan *R (Rankin et al. 2015)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- e.

- f.

- Proto-Siouan

- Hidatsa

- Lakota

- Dakota

- Omaha-Ponca

- Quapaw

- *Ráhe

- lá

- da

- (wa)na

- (wa)ttá

- beg

- *RásE

- (á•)raci

- lazáta

- dazáta

- (a)nazatta

- behind,

- in back

- *aRé•

- are•´, aré•

- ilé

- idé

- ine

- téde, idé

- burn

- *Roksí

- rohcÉ

- (a)lóksohą

- doksí

- nosi

- tosí

- armpit

- *i-Ró•te

- ro•tiška, no•tiška

- loté

- doté

- nó•de

- tótte

- throat

In the labial series, Rankin & Carter & Jones (1998) reconstruct another obstruent resonant *W (28a), which yields w (28b), b (28c), m (28d), or p (28e).11 The phonetic status of *W and *R is unclear. Rankin & Carter & Jones (1998) categorize them as “obstruent resonants,” which we identify with voiced fricatives of high sonority, plausibly [β̞] and [ð̞]. We concur with their proposal.12

- (28)

- Reflexes of Proto-Siouan *W (Rankin et al. 2015)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- e.

- P-MS-Valley

- Lakota

- Chiwere

- Omaha-Ponca

- Quapaw

- *Wa-

- wa-

- ba-

- má-

- pa-

- cutting

- instrumental

- *Wá•su

- wasú

- ba•θú

- mási

- pási

- hail

- *Wá•ɣE

- wáɣačhą

- bá•xʔe

- máʔa

- báxʔa, páxʔa

- poplar,

- cottonwood

- *Wé•

- wétu

- béhu

- me

- pe

- spring

- *Wi•

- wí

- bí, bi•, (m)pí•

- mi

- mi

- sun

We propose that Lakota final voicing arose through an intermediate step of fricativization (29). First, voiceless stops *p, *t, *k fricativize and voice to obstruent resonants in the coda position, where articulation is generally weakened (29i). (We reconstruct an additional obstruent resonant *G in the velar series.) Such a development is phonetically motivated and has a parallel in the development of Spanish voiceless stops that have various realization syllable-finally. For example, the Spanish /k/ can be realized as [x], [ɣ], or [g] before a stop like /t/ (Quilis 1993). From here, coda *W and *G develop into b and g. The alveolar *R undergoes its regular development into l (29ii).

- (29)

- Development of Lakota voicing in medial codas

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- Pre-Proto-Sioux

- Proto-Sioux

- Lakota

- *top.tó.pa

- *toW.tó.pa

- tob.tó.pa

- *na.pót.potA

- *na.póR.potA

- na.pól.potA

- *šok.šó.kA

- *šoG.šó.kA

- šog.šó.kA

We propose that coda voicing in the word-final position results from the same mechanism of pre-consonantal lenition (30i) and occlusion (30ii) across word boundaries. Then, the voiced realization of stops is extended to all positions, including utterance-finally (30iii).

- (30)

- Development of Lakota voicing in final codas

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

- Pre-Proto-Sioux

- Proto-Sioux

- Pre-Lakota

- Lakota

- *tóp C-

- *tóW C-

- *tób C-

- tób

- *na.pót C-

- *na.póR C-

- *na.pól C-

- na.pól

- *šók C-

- *šóG C-

- *šóg C-

- šóg

Our reconstruction is supported by independent language-internal and dialectal evidence. First, bilabial sonorants in Lakota are known to occlude to b in preconsonantal positions (31). Additionally, comparative evidence shows that velar voiceless stops (*k) also fricativize in clusters. For example, Proto-Dakota *kri ‘arrive here’ yields Dakota hdi and Lakota glí (Rankin et al. 2015).

- (31)

- Preconsonantal occlusion of *w in Lakota (Rankin et al. 2015)

- a.

- b.

- Proto-MS-Valley

- Lakota

- *wRé

- blé

- lake, water

- *wRó•ke

- blokétu, blokéhą

- summer

Finally, we turn to Dakota, a Sioux dialect closely related to Lakota. In Dakota, the cognates of Lakota word-final voiced stops are nasal stops (Riggs 1893). This is to say, the Lakota coda-voicing corresponds to Dakota’s final nasalization (32).

- (32)

- Dakota stop voicing in coda position (Riggs 1893: 9–10)

- a.

- b.

- medial onset

- apocope

- nape

- nam

- hand

- topa

- tom

- four

- watopa

- watom

- to row

- waniča

- wanin

- none

- yuta

- yun

- to eat

- kuya

- kun

- below

We propose that the Dakota final nasalization arose through an interstage with fricativization, in a way that closely parallels Austronesian (§3). First (33i), preconsonantal coda stops fricativize to *W and *R. (This stage is common to both Lakota and Dakota.) Second (33ii), the Dakota obstruent sonorants devoice. Third (33iii), voiceless fricatives create a precondition for spontaneous nasalization. Finally (33iv), nasalized fricatives occlude. The developments of the Pre-Proto-Sioux *top C- are illustrated in (34).

- (33)

- Development of Lakota final nasalization

- o.

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

- iv.

- Pre-Proto-Sioux

- Proto-Sioux

- Pre-Dakota

- Pre-Dakota

- Dakota

- *top C-

- *toW C-

- *toW̥ C-

- *tõW̥̃ C-

- tom C-

- *yut C-

- *yuR C-

- *yuR̥ C-

- *yũR̥̃ C-

- yun C-

- (34)

- Developments of Pre-Proto-Sioux *-p C-

In sum, we discussed phonetically unnatural developments in two closely related branches of Sioux. In Lakota, coda stops undergo voicing. In Dakota, word-final stops undergo nasalization. We demonstrated that in both languages, the unusual developments are best understood as arising from a combination of several natural sound changes.

5 Final nasalization in other languages

Our paper focuses mainly on Austronesian and Sioux. Nonetheless, final nasalization has been reported in other languages as well. In this section, we briefly discuss three additional cases in Hueyapan Nahuatl, Bribri, and Southeastern Tepehuan. While we do not have enough language-internal and dialectal data to present fully fleshed-out accounts, there is suggestive evidence for each of the three languages that final nasalization arose via a sequence of phonetically motivated changes.

5.1 Hueyapan Nahuatl

In Hueyapan Nahuatl (Southern Uto-Aztecan), the bilabial fricative β (< Classic Nahuatl w) is realized as h word-finally after (historically) short vowels, but as ŋ after (historically) long vowels (Pharao Hansen 2018). For example, β alternates with h in kioβi ‘it rains’ ∼ oːgioh ‘it rained,’ where the preceding vowel is short (p. 3), but with ŋ in tɛlɑ:βi ‘it rains heavily’ ∼ oːtɛlɑːn ‘it rained heavily,’ where the preceding vowel is long (p. 4). We propose that β developed into h and ŋ through an interstage with the voiceless bilabial fricative *ɸ. After short vowels, the voiceless fricative debuccalized to h. After long vowels, the fricative additionally nasalized to ŋ. Our proposal is supported by dialectal data. For example, not͡ɬɑːgah ‘my man/husband’ is realized by some speakers from Atlahuilco as not͡ɬagaɸ (p. 7), directly testifying to the stage of final devoicing.

5.2 Bribri

In section 3, we apply our incremental sound change explanation to word-final nasalization. However, nothing in our account precludes the same sequence of changes from taking place word-internally. Another case where nasal stops plausibly developed along a path similar to (35) includes codas in Bribri (Chibchan). In Bribri, the voiced bilabial stop /b/ is realized as a nasal [m] in the coda position, e.g. /ǰéb/ [ǰém] ‘espavel (type of tree),’ /bâbbǎ/ [bâmbǎ] ‘hot’ (Constenla 1981: 112). The voiced dental stop /d/ is realized as a nasal [n] before voiced consonants, e.g. /dîddǐ/ [dîndǐ] ‘sharp’ (p. 112–113). The voiceless velar stops /k/ is realized as a nasal [ŋ] before voiced stops, e.g. /tkʊ̂kdʊ̀/ [t͡k̯x̯ʊ̂ŋdʊ̀] ‘to sit’ (p. 112). Language-internal and dialectal evidence both point to earlier stages of lenition, including fricativization. For example, the Bribri /d/ is realized as a voiced alveolar tap or trill [r] (possibly from an earlier *ð) before voiceless consonants and pause, e.g. /iũ̂dkẽ̀/ [iũ̂rkẽ̀] ‘it flies,’ /uʊ̂kìd/ [wʊ̂kìr] ‘head’ (p. 112–3). In many related languages, Proto-Chibchan (PCh) stops are realized as fricatives. For example, the PCh *p and *b become Térraba ɸ in word-initial position (p. 219, 221). PCh *b becomes Muisca β (p. 222). PCh *d becomes s in Boruca intervocalically before an oral vowel, and in Muisca before oral vowels in non-morpheme-final position (p. 225–6). PCh *g becomes Cabécar /h/ before i and u (presumably via an interstage with *x < *ɣ) (p. 230).

5.3 Southeastern Tepehuan

We suggest that the development of final nasalization in several Austronesian languages (§3), Dakota (§4), and plausibly Hueyapan Nahuatl as well as Bribri, proceeded through an interstage with fricativization. Nonetheless, other pathways have also been attested. In Noon (§1), for example, final nasalization developed from the deoralization of prenasalized stops (Merrill 2023; 2015). A third trajectory—different yet—is suggested by Southeastern Tepehuan (Uto-Aztecan). In Tepehuan, voiced stops (and an affricate) /b/, /d/, /dž/, and /g/ are realized as preglottalized nasals [ʔm], [ʔn], [ʔñ], and [ʔŋ] in codas (Willett 1991: 13), e.g. ˈkai.baʔ ‘it will ripen’ but kaiʔm ‘it (has) ripened’ (p. 17). We suggest that a likely course of events involved, first, the preglottalization of coda stops (*-VD > *-VʔD), and second, post-glottal nasalization (> -VʔN). Both changes are well motivated—the glottalization of coda stops is independently attested, and so is spontaneous nasalization in the vicinity of glottals (rhinoglottophilia in Matisoff 1975). Thus, while many a pathway may lead to the phonetically unmotivated word- (or syllable-)final nasalization, each of them can be explained as proceeding through a series of phonetically grounded steps.

In sum, a preliminary look at each of the three additional languages suggests that final nasalization developed via a sequence of natural sound changes. In Hueyapan Nahuatl and Bribri, word-final and coda nasalization plausibly developed via interstages with fricativization. In Southeastern Tepehuan, final nasalization likely involved a stage of stop preglottalization followed by post-glottal nasalization.

6 Discussion and conclusions

In conclusion, we have presented detailed investigations of five cases of word-final nasalization. In four of the five cases (Kayan-Murik, §3.1; Berawan, §3.2; Kalabankan Murut, §3.3; Dakota, §4), final nasalization is plausibly demonstrated to have a complex history, involving a sequence of four sound changes: (i) fricativization of voiced stops, (ii) devoicing of the fricatives, (iii) spontaneous nasalization before voiceless fricatives, and (iv) occlusion of the nasalized fricatives to nasal stops (35).

- (35)

- Final nasalization as a series of changes

Each of the changes is articulatorily or perceptually grounded, i.e. phonetically natural. The interstages of fricativization (and devoicing in Berawan) are supported by independent language-internal or dialectal evidence. In the last case (KB, §3.4), final nasalization can arise from a series of changes or by analogical extension. In addition, we have also proposed a new explanation for the development of unnatural final voicing in Lakota.

Our findings bear on the division of labor and the role of phonetic naturalness in diachrony and synchrony. While unnatural phonological processes are attested (e.g. Hyman 2001; Coetzee & Pretorius 2010; Merrill 2015; Beguš 2020; 2022; Beguš et al. 2022; Beguš & Dąbkowski 2023; Dąbkowski 2023; Russell in prep.), we maintain that the sound changes are always grounded in the realities of language production and perception. As such, our findings lend support to the long-held assumption that synchronic processes, including unnatural alternations, can be traced back to phonologizations of natural sound changes (Hyman 1976; Ohala 1981; 1983; Blevins 2004; 2007; 2008; 2013). Cumulatively, the cases of final nasalization suggest that Beguš’s (2019) blurring process, which derives unnatural phonological processes from specific sequences of sound changes, can be useful for understanding unnatural alternations.

Finally, we address the relation of our “incremental” account to Occam’s razor, or the principle of parsimony, which states that a plurality of entities should not posited unless necessary (Joseph & Janda 2003: 23–26; Maurer 1978). In other words, when faced with two empirically equivalent accounts, the simpler one is preferred.

Occam’s razor is invoked by Blust (2005; 2023), who proposes that a number of phonetically unmotivated developments result from single unnatural sound changes, and opposes incremental accounts which posit a series of natural changes that lead to an unnatural development. Blust (2005; 2023) motivates his stance primarily with the principle of economy—he sees the intermediate stages as an unmotivated departure from theoretical simplicity. We believe that Blust’s (2005; 2023) argument is unfounded on both empirical and theoretical grounds.

First, Occam’s razor is used to decide between two empirically equivalent accounts. Otherwise, empirical adequacy always trumps parsimony. The intermediate stages we posit are independently motivated by language-internal developments (Beguš 2019; Beguš & Dąbkowski 2023) and dialectal correspondences. As such, the interstages are not arbitrary. Since our proposal makes sense of a greater number of interrelated facts, it has a stronger empirical standing than a single-change account. This is to say, the incremental account would be preferable even if it were less parsimonious.

Second, even if there were no empirical upsides to our account, a proposal that succeeds at reducing an unnatural development to a combination of phonetically motivated sound changes would still be preferable. While it is true that an incremental account postulates a number of additional sound changes for each development, Blust’s (2005; 2023) theory allows completely unnatural changes. In doing so, Blust (2005; 2023) radically expands the total set of feasible sound changes, challenging several centuries of linguistic scholarship. Accepting Blust’s (2005; 2023) proposal would be tantamount to accepting a vastly more powerful theory of language change, where arguments from phonetics and typology become less influential. Thus, we conclude, our incremental account of final nasalization is preferable to a single-change account on both empirical and theoretical grounds.

Notes

- Merrill (2023) provides further evidence for this diachronic proposal from other Cangin languages, and shows that Ndut-Paloor, as well as all dialects of Noon-Laalaa (except the Thiès dialect), have the same N∼D alternation. In Japanese, a similar phenomenon is found in coda positions (albeit not word-finally due to the languages’ phonotactic constraints). The Japanese D∼N alternation, e.g. root-finally in asob-u ∼ ason-de ‘play,’ goes back to a prenasalized voiced stop with different reflexes depending on the verb form. In most environments, the Old Japanese prenasalization was lost, i.e. *asoᵐb-u > *asob-u. However, in gerund forms, voicing assimilation and elision took place, but the prenasalization was retained, i.e. *asoᵐb-ite > ason-de (Frellesvig 2010: 34–36, 54, 193). Notably, the Japanese N∼D alternation also arises from two sound changes affecting an earlier ND. [^]

- Specifically, the development exemplifies the blurring chain, a subtype of the blurring process. In the blurring chain, at least three sound changes operate, schematically represented as (i) B > C / X; (ii) C > D, and (iii) D > A, ultimately resulting in B > A / X. The first change (fricativization) creates a complementary distribution. The next two changes (devoicing, nasalization) operate on the newly created fricatives. The last change (occlusion) blurs the original complementary distribution created by fricativization, because the devoiced and nasalized sounds are no longer fricatives. [^]

- Following Beguš (2019), we use the term tendency to indicate that the universal facts of language production and perception are reflected in each language’s phonetic implementation to varying degrees and may, but need not, give rise to sound changes—not to indicate that in some cases the opposite sound changes, which go against the phonetic trend, are expected. For example, velars tend to universally palatalize before front vowels due to co-articulation (although the degree of palatalization differs from language to language). As such, we consider velar palatalization before front vowels to be a possible sound change. It does not follow that the reverse sound change (i.e. the velarization of palatals before front vowels) is expected in a minority of cases. [^]

- The following natural class abbreviations have been used: C = (voiceless) consonant, D = voiced oral stop, G = voiced consonant, N = nasal stop, R = approximant, S = (voiceless) fricative, T = (voiceless) oral stop, V = vowel, X̃ = nasalized segment, Z = voiced fricative. [^]

- The most frequent cases of fricative approximantization involve voiced fricatives. This is congruent with our proposal since the preceding (spontaneous) nasalization most likely results in at least partial voicing of the adjacent fricative. Nonetheless, the approximantization of voiceless fricatives is also attested, e.g. *ɸ > w, *θ > w, *x > w / _ C (Old Armenian; Kümmel 2007: 87); *f > w / V _ C (Zaza, Gorani, Kurdish; Kümmel 2007: 87); *f > ʋ / # _ (Proto-Finnish; Hakulinen 1979); *f > j (Marshallese; Hale 2007: 89); *s > *j / #C0V _ # (Proto-Tocharian; Kümmel 2007: 88); s̺ > j / V _ # (common Eastern Romance; Kümmel 2007: 88); θ > l (Kurdish; Kümmel 2007: 80); *ʆ > j / _ T (central and south Sami; Kümmel 2007: 88); *ɬ > l (Proto-Omotic; Ehret 1995); and *ç > j / (V) _ t and/or s (northwestern Italian, common Romance, common French, Franco-Provençal, Gascon, and others, the exact environment depending on the language; Kümmel 2007: 88). Many of these changes are unconditioned or take place word-finally, postvocalically, or before a consonant, i.e. in environments similar to the hypothesized cases of approximantization in Austronesian and Sioux. [^]

- Other attested realizations include “nasalization of [h̃], nasalization on the preceding vowel,” as well as “sequential frication and nasalization” (Warner et al. 2015). [^]

- Additionally, the latter component of the Polish nasal diphthongs assimilates with respect to the place of articulation of the following obstruent, giving rise to a number of conditioned allophones. [^]

- Alternatively, *-d- might have lenited to -r- without the intermediate stage of *-ð-, since d (> r) > r is a common sound change in its own right. Either trajectory attests to the intervocalic lenition of voiced stops. [^]

- As in Murik, *-d- might have lenited to -r- without the intermediate stage of *-ð-. Positing the intermediate stage of *-ð- allows for parallel treatment of all three series of stops. On the other hand, a direct change of *-d- > -r- helps explain why *-d- does not devoice, while the other Proto-Malayo-Polynesian stops-turned-fricatives do. Either trajectory attests to the postvocalic lenition of voiced stops. [^]

- If *-d had lenited to *-r as a single sound change, as discussed in the preceding footnotes, the word-final -n could have developed from *-r directly, without the intermediate stage of fricativization. Nonetheless, this explanation does not extend to the other series, still necessitating an incremental approach with a sequence of step-wise changes. [^]

- For comparison, the Proto-Siouan regular approximant *r usually yields r, l, n, ð, or y, and the regular approximant *w yields w or m in most daughter languages (Rankin & Carter & Jones 1998). [^]

- Rankin et al. (2015) suggest that *R might be, at least in some cases, traced back to an epenthetic glide (p. 746). Most instances of *W derive from sequences of *w-w, arising from medial vowel syncope (< *wV-w) (p. 135). As such, *W and *R may ultimately go back to glides, which later underwent fortition. [^]

Abbreviations

av actor voice 15

lv locative voice 15

npst nonpast 15

ov object voice 15

Funding information

Our research has been partly funded by the Georgia Lee Fellowship in the Society of Hellman Fellows to Gašper Beguš.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Alex Elias for drawing our attention to the examples of nasal unpacking in Portuguese-based creoles and to Katie Russell for feedback on a previous version of this paper.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Adelaar, K. Alexander. 1981. Reconstruction of Proto-Batak phonology. In Historical linguistics in Indonesia, vol. 1, 1–20.

Baranowska, Karolina & Kaźmierski, Kamil. 2020. Polish word-final nasal vowels: Variation and, potentially, change. Sociolinguistic Studies 14(1–2). 135–162. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1558/sols.37918

Beguš, Gašper. 2018. Unnatural phonology: A synchrony-diachrony interface approach. Harvard University dissertation.

Beguš, Gašper. 2019. Post-nasal devoicing and the blurring process. Journal of Linguistics 55(4). 689–753. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S002222671800049X

Beguš, Gašper. 2020. Estimating historical probabilities of natural and unnatural processes. Phonology 37(4). 515–549. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0952675720000263

Beguš, Gašper. 2022. Distinguishing cognitive from historical influences in phonology. Language 98(1). 1–34. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2021.0084

Beguš, Gašper & Dąbkowski, Maksymilian. 2023. The blurring history of intervocalic devoicing. Manuscript. University of California, Berkeley. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/qkjn2

Beguš, Gašper & Nazarov, Aleksei I. & Björklund, Anna & Baldoceda, Blas Puente. 2022. Lexicon against naturalness: Unnatural gradient phonotactic restrictions in Tarma Quechua. PsyArXiv Preprints. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/gw6vj

Biagui, Noël-Bernard & Quint, Nicolas. 2013. Casamancese Creole. In Michaelis, Susanne Maria & Maurer, Philippe & Haspelmath, Martin & Huber, Magnus (eds.), The Survey of Pidgin & Creole Languages. Vol. 2 (3): Portuguese-based, Spanish-based and French-based Languages, 40–49. Oxford University Press.

Birmingham, Jr., John Calhoun. 1970. The Papiamentu language of Curaçao. University of Virginia dissertation.

Blevins, Juliette. 2004. Evolutionary Phonology: The emergence of sound patterns. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511486357

Blevins, Juliette. 2007. The importance of typology in explaining recurrent sound patterns. Linguistic Typology 11. 107–113. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/LINGTY.2007.009

Blevins, Juliette. 2008. Consonant epenthesis: Natural and unnatural histories. In Good, Jeff (ed.), Language Universals and Language Change, 79–107. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199298495.003.0004

Blevins, Juliette. 2013. Evolutionary Phonology: A holistic approach to sound change typology. In Honeybone, Patrick & Salmons, Joseph (eds.), Handbook of Historical Phonology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232819.013.006

Blevins, Juliette & Egurtzegi, Ander & Ullrich, Jan. 2020. Final obstruent voicing in Lakota: Phonetic evidence and phonological implications. Language 96(2). 294–337. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2020.0022

Blevins, Juliette & Garrett, Andrew. 1992. Ponapean nasal substitution: New evidence for rhinoglottophilia. In Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, vol. 18, 2–21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v18i1.1585

Blevins, Juliette & Garrett, Andrew. 1993. The evolution of Ponapeic nasal substitution. Oceanic Linguistics. 199–236. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/3623193

Blust, Robert. 2005. Must sound change be linguistically motivated? Diachronica 22(2). 219–269. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/dia.22.2.02blu

Blust, Robert. 2023. *b > -k-: a Berawan sound change for the ages. University of Hawai’i at Manoa Manuscript.

Blust, Robert. 2013. The Austronesian Languages. Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics.

Blust, Robert. 2016. Austronesian against the world: Where the P-Map ends. Talk and handout presented at the 42nd meeting of Berkeley Linguistic Society. Feb. 5–6. Available on March 20, 2018 at: www.researchgate.net/publication/294732706.

Blust, Robert & Trussel, Stephen & Smith, Alexander D. 2023. CLDF dataset derived from Blust’s “Austronesian Comparative Dictionary” (v1.2) [Data set]. Zenodo.

Bowern, Claire. 2015. Linguistics: Evolution and language change. Current Biology 25(1). R41–R43. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.053

Burkhardt, Jürgen M. 2014. The reconstruction of the phonology of Proto-Berawan. Johann-Wolfgang-Goethe-Universität zu Frankfurt am Main dissertation.

Coetzee, Andries W. & Pretorius, Rigardt. 2010. Phonetically grounded phonology and sound change: The case of Tswana labial plosives. Journal of Phonetics 38. 404–421. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2010.03.004

Cohen Priva, Uriel. 2017. Informativity and the actuation of lenition. Language. 569–597. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2017.0037

Collinder, Björn. 1960. Comparative Grammar of the Uralic Languages (A Handbook of the Uralic Languages 3). Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Constenla, Adolfo. 1981. Comparative Chibchan phonology. University of Pennsylvania dissertation.

Dąbkowski, Maksymilian. 2023. Postlabial raising and paradigmatic leveling in A’ingae: A diachronic study from the field. In Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America, vol. 8, 5428. Washington, DC: Linguistic Society of America. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v8i1.5428

Davidson, Lisa. 2016. Variability in the implementation of voicing in American English obstruents. Journal of Phonetics 54. 35–50. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2015.09.003

Ehret, Christopher. 1995. Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): Vowels, tone, consonants, and vocabulary. Vol. 126. Univ of California Press.

Frellesvig, Bjarke. 2010. A history of the Japanese language. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511778322

Fruehwald, Josef. 2013. The phonological influence on phonetic change. University of Pennsylvania dissertation.

Garrett, Andrew & Johnson, Keith. 2013. Phonetic bias in sound change. In Yu, Alan (ed.), Origins of Sound Change: Approaches to Phonologization, 51–97. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199573745.003.0003

Gordeeva, Olga & Scobbie, James. 2010. Preaspiration as a correlate of word-final voice in Scottish English fricatives. In Fuchs, Susanne & Toda, Martine & Żygis, Marzena (eds.), Turbulent Sounds: An Interdisciplinary Guide (Interface Explorations 21), 167–207. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter Mouton. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110226584.167

Grierson, George A. 1922. Spontaneous nasalization in the Indo-Aryan languages. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 54(3). 381–388. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00053570

Hakulinen, Lauri. 1979. Suomen kielen rakenne ja kehitys [The structure and development of the Finnish language]. Helsinki: Otava.

Hale, Mark. 2007. Historical linguistics: Theory and method (Blackwell Textbooks in Linguistics). Blackwell.

Hyman, Larry M. 1976. Phonologization. In Juilland, Alphonse (ed.), Linguistic studies presented to Joseph H. Greenberg, 407–418. Saratoga, CA: Anna Libri.

Hyman, Larry M. 2001. The limits of phonetic determinism in phonology: *NC revisited. In Hume, Elizabeth & Johnson, Keith (eds.), The Role of Speech Perception in Phonology, 141–186. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Jackson, Kenneth Hurlstone. 1967. A historical phonology of Breton. Dublin, Ireland: Institute for Advanced Studies.

Johnson, Sarah E. & Barlaz, Marissa & Shosted, Ryan K. & Sutton, Brad P. 2019. Spontaneous nasalization after glottal consonants in Thai. Journal of Phonetics 75. 57–72. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2019.05.001

Joseph, Brian D. & Janda, Richard D. (eds.). 2003. The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Blackwell. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756393

Kaplan, Abby. 2010. Phonology shaped by phonetics: The case of intervocalic lenition. University of California, Santa Cruz dissertation.

Kaźmierski, Kamil & Szlandrowicz, Marta. 2020. Word-final /ɔ̃/ in Greater Poland Polish: A cumulative context effect? Research in Language 18(4). 381–394. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18778/1731-7533.18.4.02

Key, Mary Ritchie. 1968. Comparative Tacanan phonology with Cavineña phonology and notes on Pano-Tacanan relationship. The Hague: Mouton.

Khattab, Ghada & Al-Tamimi, Jalal & Alsiraih, Wasan. 2018. Nasalisation in the production of Iraqi Arabic pharyngeals. Phonetica 75(4). 310–348. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1159/000487806

Kirchner, Robert Martin. 2001. An effort based approach to consonant lenition. New York/London: Routledge.

Kümmel, Martin Joachim. 2007. Konsonantenwandel: Bausteine zu einer Typologie des Lautwandels und ihre Konsequenzen für die vergleichende Rekonstruktion. Wiesbaden: Reichert.