1 Introduction

Two major groups of analyses of the past tense in English and across languages are: (i) existential semantics with appropriate domain restriction, and (ii) pronominal analysis. In particular, the literature has extensively explored the idea that English has a pronominal tense (Partee 1973; Abusch 1994; Heim 1994; Kratzer 1998; Sharvit 2014).1 In the literature on this topic, ‘pronominal’ means that (i) the past tense is a variable of type i, receives its value from the assignment function g, and infelicitous without a salient antecedent in the context; (ii) the possible values of the past tense are presupposed to precede the speech time’;2 (iii) it can be bound like a pronoun (Chen et al. 2020). While we can find many instances of the English past tense that fit these criteria, there are also data that cannot be fully integrated into this analysis. These involve the (obligatory) use of the English simple past without any salient antecedent, as the following sentences illustrate.3

- (1)

- (Pointing at a church:)

- Who built/#has built this church?

- Borromini built/#has built this church.

- (Kratzer 1998)

- (2)

- Mary, my colleague, was born/#has been born in New Zealand.

To explain these data, previous authors have proposed two major groups of analyses: that the English past is lexically ambiguous between a pronominal past and an existential past, or ambiguous between a pronominal past and a sort of present perfect reading. In any case, these data, and the vast amount of other data suggesting the the English past is pronominal, create a dilemma for a unified semantic analysis. In addition, there is no satisfactory analysis that accounts for the distribution of the pronominal and the non-pronominal readings.

In this paper, I propose that the distribution of these ‘problematic’ instances of the English past tense can be predicted: they suggest that the English past tense is lexically ambiguous between a pronominal tense, and a tense that presupposes existence and uniqueness of a past reference time with respect to a certain property. The English past tense also displays similar presupposition projection patterns observed with anaphoric and unique definite DPs in the nominal domain.

The literature on definite descriptions has an intensive discussion on whether definiteness is better characterized by uniqueness (Russell 1905; Kadmon 1990; Elbourne 2013; Hawkins 2015) or familiarity (Kamp 1981; Heim 1982; Kamp & Reyle 2013). However, the recent literature on definiteness suggests that ‘familiarity’ or ‘uniqueness’ may not be a matter of different analyses for definiteness, but rather different sub-concepts of definiteness that languages can use separate morphology to mark (Schwarz 2009; 2013; Jenks 2015; 2018; Arkoh & Matthewson 2013: a.o.). The novel observation regarding the English past tense suggests that we may be able to extend this idea to the temporal domain. I would like to argue that the data in this paper suggest that the English past tense is lexically ambiguous between an anaphoric past tense and a unique past tense. In other words, the English past tense behaves more like the definite article the, rather than pronouns.

This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, I discuss data that are difficult to explain under a pure pronominal analysis of the English past and the previous attempts to account for them. In Section 3, I argue that these data can be accounted for if we allow the English past tense to also carry existence and uniqueness presuppositions, parallel with similar patterns in definite DPs. In Section 4, I will discuss one possible way to formalize this idea. Following the recent analyses of the two kinds of definites, I propose that the English past tense is lexically ambiguous between the two readings, with the anaphoric past tense having an additional index argument, which can be dynamically bound.

The data in this paper are obtained from three speakers mostly: one speaker from New Zealand, one from the UK, and one Australian. The speakers are given the context provided in the examples, and two different tasks: (i) produce sentences under the intended reading and context; (ii) compare the past tense and present perfect in a given sentence. In particular, the first task is used to determine the distribution of the past tense and whether it is the most natural choice for speakers in contexts with and without a salient past reference time (e.g. we are talking about what Mary did at yesterday’s party, and the speaker is invited to describe the situation; we are looking at an open window with no contextually salient past reference time, and the speaker asks about that opening event). It is motivated by the observation in Kratzer (1998), that a strictly anaphoric past tense should be prohibited in contexts without a salient antecedent, where the present perfect is preferred. The second task compares the past tense and the present perfect directly, and helps distinguish some sutble differences where both forms are possible (see Section 3.2). Throughout this paper, the examples will be given in both the past tense and the present perfect. We conclude that in general, if the past tense is obligatory, the present perfect is prohibited.

While I will not provide an analysis of the present perfect in the scope of this paper, this asymmetry between the past tense and the present perfect is too strong and consistent to be ignored. I will assume the more ‘relaxed’ version of the Extended Now analysis of the present perfect as in Grønn & Von Stechow (2017). This analysis says that the present perfect allows the reference time to be either an Extended Now interval (overlapping the speech time), or a past interval. It follows that whenever the reference time is a past interval, the English past tense with either the anaphoricity or the uniqueness presupposition, will be a presuppositionally stronger alternative than the present perfect. By Maximize Presupposition or similar principles (Heim 1991; Percus 2006; Sauerland 2008; Singh 2011; Sudo 2017: a.o.), the present perfect will be prohibited whenever the presupposition of the past tense is satisfied.

2 Challenges to pronominal tense theories and previous solutions

Partee (1973) first noted that there are parallels between the English past tense and pronouns. She noted that a simple quantificational approach cannot capture the correct reading of the following sentence.

- (3)

- I didn’t turn off the stove.

Regardless of the scoping choices, treating the past tense as the simple existential quantifier ∃ derives the wrong readings: either ∃t[the speaker does not turn off the stove (t)], or ¬∃t[ the speaker turns off the stove (t)]. Partee (1973) points out that the correct reading of the sentence seems to be a deictic one: the speaker is making an assertion about the time before (s)he left the house, namely that (s)he did not turn off the stove at that time.

Although Partee (1973) labels this as the ‘deictic’ use of tense, there does not seem to be a fundamental difference between the deictic use and the typical anaphoric use of pronouns with an explicit antecedent. When the antecedent is a past time, regardless of whether it is explicitly given by an adverbial (4), or salient in the context (5), the past tense must be used.

- (4)

- Yesterday, John played catch/#has played catch with his dog in the park.

- (5)

- (Mary and Sue are planning to go to the gym, but Sue has to cancel last minute. Mary goes alone and comes back after an hour.)

- Sue: So, how was your workout/#has your workout been?

These observations motivate the analysis that the English past tense behaves like a pronoun. It denotes a contextually salient time interval, in a way just like pronouns denote contextually salient individuals.

2.1 The perfect aspect

However, Kratzer (1998) noted that there are instances of the English past tense that are surprising under the pronominal account. These are out-of-the-blue uses of the past tense when there is no contextually salient past time in the context.4

- (6)

- (Pointing at a church. There is no contextually salient past time when the following question comes up:)

- Who built this church? Borromini built this church.

In contrast, the German simple past tense behaves as expected, being unacceptable in this context.5 In the absence of a contextually salient past time, the present perfect must be used instead.

- (7)

- #Wer

- Who

- baute

- built

- diese

- this

- Kirche?

- church

- Borromini

- Borromini

- baute

- built

- diese

- this

- Kirche.

- church

- (8)

- Wer

- Who

- hat

- has

- diese

- this

- Kirche

- church

- gebaut?

- build

- Borromini

- Borromini

- hat

- has

- diese

- this

- Kirche

- church

- gebaut.

- built

- ‘(Lit.) Who has built this church? Borromini has built this church.’

Note that we cannot analyze the English data as some sort of accommodation of the antecedent. Assuming that the pragmatics of accommodation works the same across languages given the same context, we would not expect this contrast. This suggests that the contrast between English and German illustrates the different grammatical properties of the past tenses.

Kratzer also refutes the idea that maybe this contrast is a matter of terminology. She points out that the German past tense is strictly anaphoric, quoting the following contrast:

- (9)

- a.

- We will answer every letter that we got.

- ✔in context: Uttered without contextually salient past times.

- ✔in context: Referring to the letters we received over a salient past interval.

- b.

- Wir

- we

- werden

- will

- jeden

- every

- Brief

- letter

- beantworten,

- answer

- den

- that

- wir

- we

- bekamen.

- got

- ‘We will answer every letter that we got.’

- #in context: Uttered without contextually salient past times.

- ✔in context: Referring to the letters we received over a salient past interval.

In (9a), the English past tense can be used without previously mentioned or contextually salient past times. This contrasts with its German counterparts: the German simple past can only be used if there is a contextually salient past time. If this time is not available, the present perfect is obligatory.

In order to account for the English data, Kratzer proposes that the English simple past sentences without salient antecedent times actually have the semantics of a perfect aspect (10) with present reference time. In other words, the English simple past morphology is lexically ambiguous between the pronominal past reading and a present perfect reading.

- (10)

- a.

- ⟦Perfect⟧ = λP.λt.λw.∃e[τ(e) ≺ t ∧ P(e)(w) = 1]

- b.

- ⟦Borromini built this church⟧ = λw.∃e[B.build-churchτ(e) ≺ tc]

After saturating λt with tc, the church example will have the meaning in (10b). The ‘past’ reading is due to the fact that the event is located prior to the speech time. Hence, (6) is not a counterexample to the pronominal past tense analysis, because it does not actually contain a past tense in the semantic sense.

Note that the present perfect semantics here is not to be confused with the present perfect construction (in the morphological sense). Kratzer (1998) proposes the difference between English and German follows from the fact that languages can vary in what the simple past morphology spells out. In particular, while the English simple past can spell out a present reference time with a perfect aspect, in (standard) German, only the present perfect construction can spell out this combination. In German, the simple past is restricted to past references times that are contextually salient.

However, Matthewson et al. (2019) argue that explaining the acceptability of (6) ‘via a present perfect reading of the past tense form runs into the complication that the English present perfect is itself infelicitous in’ (6) (Matthewson et al. 2019: p.1). Matthewson et al. (2019) propose that (6) instead shows that the English past tense is ambiguous between a pronominal and an existentially quantified tense.

2.2 Domain restriction of the existential past

The idea of restricting the domain of an existentially quantified past tense has also been previously explored in the literature. The central idea is that Partee’s stove sentence (11a) only shows that the English past tense needs salient contextual domain restriction. Authors who adopt this view (Ogihara 1995; 2011; Matthewson et al. 2019: a.o.) argue that the stove sentence should have the semantics in (11b). They adopt a quantificational analysis of the simple past, with a domain restrictor C (Von Fintel 1994) restricting the domain of quantification to a contextually salient time interval, such as the time before the speaker leaves the house.6

- (11)

- a.

- I didn’t turn off the stove.

- b.

- ¬∃ t ⊆ the 20 minutes before I left the house

- such that[I-turn-off-stove(t)]]

This idea of domain restriction has been applied to those uses of the English past problematic for the pronominal analysis. In particular, Matthewson et al. (2019) propose that (6) is indeed an instance of the existential past tense.

However, assuming a simple existential analysis runs into the obvious problem that the existential reading of the simple past is not always available in contexts without a salient past time. This leads to the question of why domain restriction works in some cases but not others. This is illustrated in the following contrast noted by Matthewson et al. (2019).

- (12)

- (I am curious which of my friends has read Emma at some point in their life:)

- #Who read Emma? Julia read Emma.

- (13)

- (There has been confusion about what our book club’s chosen book was this month. Some of us read Emma and some read Persuation.)

- Who read Emma? Julia read Emma.

In (12), there is no contextually salient past time, hence the past tense is infelicitous. This contrasts with (13), where there is a salient reference time in the context. Matthewson et. al point out that this contrast would follow if the English past were purely pronominal, but this would leave the church example (6) unexplained. In other words, there needs to be some kind of restriction of the ‘existential’, i.e. the ‘out-of-the-blue’ use of the English past tense.

In order to reconcile the existential past analysis for (6) with the many other sentences where the past tense is infelicitous without salient reference times, Matthewson et al. (2019) propose that the English past tense on its existential reading must have non-vacuous domain restriction. In particular, (13) can be analysed as an existential past with the domain restricted to the times within the past month. On the other hand, (12) is infelicitous because there is no non-vacuous domain restriction.

The resulting reading is similar to Ogihara’s (2011) semantics for the existential past. Ogihara’s analysis would lead to the following semantics (14).

- (14)

- ∃t[t ⊆ the past month ∧ read(Julia, Emma, t)]

Matthewson et al. (2019) argue that the past tense’s domain restriction can be provided by a specific event, even if the exact run time of the event is unknown. This is crucial because in the discourse in (6), the speakers need not to known when exactly the church was built to make the past tense felicitous. All that is needed is the fact that ‘there was clearly at some point a particular building event of that church’.

Matthewson et al. (2019) also noted similar patterns with several other predicates, where the knowledge of a specific event licenses the use of the past tense (15)–(16).

- (15)

- (I bought a brand new copy of Emma and now I see the pages are creased. I ask:) Who read Emma?

- (16)

- Who littered?

- #in the context: I am curious about who has ever done anti-social things in a forest.

- OK in the context: I am walking in the forest and notice a piece of litter on the ground.

However, requiring the event to be specific seems to both over- and undergenerate this use of the past tense, since Matthewson et al. (2019) do not define the criterion for specificity. In (17), suppose the speaker wants to talk about a chess game between Sue and Mary that took place a week ago. The event is specific enough: it is a losing event involving Mary, Sue and a chess game. However, without a contextually salient past time (e.g. the sentence is about what happened at a tournament that they both participated in, or about what happened during the past week), the past tense still seems infelicitous.

- (17)

- (Uttered without any contextually salient past time:)

- ??Mary lost a chess game against Sue.

For states, too, we cannot tell the difference between (18a) and (18b). The former is about a specific state of Sheldon being a child prodigy, and the latter about a specific state of Sheldon Cooper being sick.

- (18)

- (Uttered without any contextually salient past time:)

- a.

- Sheldon Cooper, the physicist over there, was a child prodigy.

- b.

- #Sheldon Cooper, the physicist over there, was sick.

In general, for these examples, it seems that what’s needed is not the specificity of the event, but rather, the (specific) event must be known or can be inferred by both participants.

A remaining problem is whether a domain restricted existential past can be distinguished from a pure pronominal past.7 Matthewson et al.’s analysis differs from Ogihara’s analysis in that they treat the English past tense as ambiguous between an existential reading and a pronominal reading. Since we can just analyze the ‘pronominal’ past examples along the lines of (11b) and (14), it seems that we could just analyze all instances of the past tense as existential with domain restriction. In other words, the pronominal analysis becomes unnecessary without further evidence.

In Section 3, I will argue that those instances that Matthewson et al. (2019) take to be the existential past are instances of the past tense presupposing existence and uniqueness, and they can indeed be distinguished from the typical pronominal past tense.

2.3 Indefinite past tense?

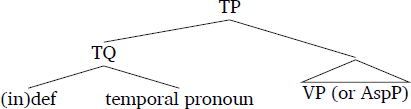

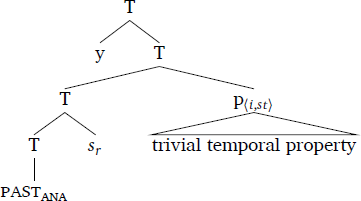

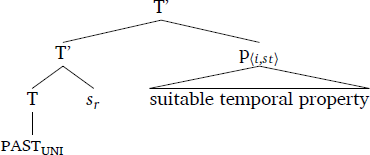

A previous account based on the notion of definiteness is Grønn & Von Stechow (2016). They propose that the past tense in English is ambiguous between a definite and an indefinite reading, with the meaning of ‘definiteness’ being one of familiarity.

In particular, the indefinite reading of the English past is meant to cover the data considered problematic for a pure pronominal tense approach. This is achieved by adding a covert indefinite article (and a covert definite articles for the typical pronominal past). The definite an indefinite articles presuppose familiarity/novelty of the discourse referent for tense, respectively.

- (19)

- The tense architecture of Grønn & Von Stechow (2016)

- (Grønn & Von Stechow 2016: fig.11.1, simplified)8

This analysis is similar to Matthewson et al.’s (2019). Likewise, the major problem with this analysis is that there is no restriction on the distribution of the covert definite and indefinite articles. From the discussion in Matthewson et al. (2019), we see that the ‘indefinite’ past tense is not freely available. There is clearly a difference between certain verbal predicates and contexts that always require the use of the past tense despite not having an antecedent time, and others that only allow the past tense with an antecedent. While we can analyze all the past tenses with an antecedent as ‘definite’ and all the ones without an antecedent as ‘indefinite’, doing so seems too descriptive.

2.4 Unmarked for anaphoricity?

Michaelis (1994) compares the simple past and the present perfect in English, and believes that the data discussed earlier require an existential analysis of tense, namely, an event occurred at some time prior to now. In order to allow the simple past to be used this way, she then concludes that the simple past is unmarked for anaphoricity. On the other hand, in order to account for sentences like (20), known as the Present Perfect Puzzle in the literature, she argues that the present perfect is explicitly marked for non-anaphoricity.

- (20)

- #Mary has cleaned her room yesterday.

However, if the present perfect is specifically marked for non-anaphoricity, then in the absence of any explicit or implicit antecedent, most theories of markedness or competition would predict that the present perfect should be the most appropriate form to use. Using the past tense in this case would give rise to pragmatic inferences due to not using the most appropriate present perfect. This prediction is not borne out. The actual observation is that, for those ‘existential’ uses of the past tense, the present perfect is prohibited in these contexts (21).

- (21)

- (Pointing at a church. There is no contextually salient past time when the following question comes up:)

- #Who has built this church? Borromini has built this church.

In addition, it has been noted that in such contexts, using the present perfect would give rise to inferences such as ‘hot news’ or some kind of repeatability (Portner 2003), illustrated below. If the Common Ground entails our world knowledge that humans already know the art of printing, the present perfect in (22a) is infelicitous. In (22b), however, the sentence becomes acceptable. Portner notes that from the perspective of the demon, the time of Gutenberg’s discovery would be quite a recent progress, a kind of ‘hot news’ reading.

- (22)

- a.

- (There is no contextually salient past time when the following question comes up:)

- Gutenberg discovered/#has discovered the art of printing.

- b.

- (There is a demon orchestrating important discoveries in human history, observing the humans, he says:)

- Now that Gutenberg has discovered printing, it’s time to lead these humans to do the next thing… (Portner 2003: adapted)

The repeatability inference is illustrated in (23). Given that Mary is already an adult (being the speaker’s colleague), it cannot be that the speaker is announcing her recent birth. To the extent that the sentence can be interpreted, the only interpretation seems to be that Mary has been born several times, each time at a different place, and now she is born in New Zealand, which is of course impossible.

- (23)

- (Uttered without any contextually salient past time:)

- ??Mary, my colleague, has been born in New Zealand.

However, Michaelis (1994) would predict that the present perfect is fine in these sentences, since there is no contextually salient past time, and non-anaphoricity is satisfied.

Hence, I conclude that Michaelis’ (1994) analysis is not tenable: the past tense cannot be unspecified for anaphoricity (as opposed to the present perfect being specified for non-anaphoricity), since their distribution does not align with the pattern in typical markedness contrasts.

3 Uniqueness presuppositions of the English past tense

As the preceding section shows, there is a group of data where the English past tense can be used without any contextually salient antecedent, which poses a challenge for the pure pronominal analysis. Previous analyses can be roughly grouped into three categories: (i) the English past tense is lexically ambiguous between the anaphoric reading and a ‘present perfect’ reading (Kratzer 1998); (ii) the English past tense is lexically ambiguous between an anaphoric reading and an existential reading (Michaelis 1994; Grønn & Von Stechow 2016; Matthewson et al. 2019). These analyses all fail to control for the distribution of the anaphoric and non-anaphoric past tenses.

In addition, there are two worth noting points here: (i) the past tense is not just allowed to appear in those out-of-the-blue contexts, but obligatory; (ii) these data have in common in that the reference time seems to be presupposed rather than presented as new information.

As pointed out by Matthewson et al. (2019), if these data simply illustrate some kind of present perfect reading, then there is no obvious reason why the present perfect is prohibited in those examples. The present perfect is known to have the existential reading (Iatridou et al. 2003: a.o.), where an event is asserted to have taken place (and culminated) prior to the speech time. There are several possible analyses of this reading in the literature, with the resulting semantics having little difference from Kratzer’s (1998) perfect aspect with the present tense. It is also not easy to distinguish it from the existential past tense, which also locates an event to a time prior to the speech time. I will not discuss the details of the present perfect due to limited space. The reader may refer to survey articles like Portner (2011) and Grønn & Von Stechow (2017).

However, there is one observation regarding the present perfect I would like to point out. In (24), if we want to assert that there does not exist an event of Borromini building this church, the negated present perfect sentence should simply be true. However, even in this case, the past tense is obligatory:

- (24)

- (Pointing at a church:)

- a.

- #Borromini hasn’t built this church./#This church hasn’t been built by Borromini.

- b.

- Borromini didn’t built this church./This church wasn’t built by Borromini. Michelangelo did./It was built by Michelangelo.

It seems that the building event of this church is presupposed, and the assertion is not about its existence, but rather who the agent is. In Section 3.1, I will elaborate on this idea and propose that these ‘out-of-the-blue’ uses of the past tense have in common that the reference time is presupposed to exist and be unique. In other words, the English past tense is lexically ambiguous between an anaphoric past and a unique past. Examples like (24) reflect one way of satisfying the uniqueness of the reference time, namely, letting it be the time span of the unique change-of-state event giving rise to the current state.

There are two other ways in which this uniqueness presupposition can be satisfied: (i) when the event is assumed to have taken place in the past; (ii) when the reference time is taken to be the (past) lifetime or time span of a person or entity under discussion. I will illustrate these in Sections 3.2 and 3.3.

In the rest of this section, I will show that the uniqueness of the reference time is indeed a presupposition, and compare it with patterns observed with anaphoric and unique definites in the nominal domain. I will also discuss some evidence supporting analyzing uniqueness as a separate presupposition of the English past tense.

3.1 Perceivable change-of-state events

Let us first consider a group of data that always license the past tense without a contextually salient reference time.

- (25)

- (Talking about my colleague Mary, without any contextually salient past time:)

- Mary was born in New Zealand./#Mary has been born in New Zealand.

- (26)

- (Mary is looking at a new book on Sue’s desk. There is no contextually salient past time:)

- a.

- Where did you get it?/#Where have you gotten it?

- b.

- Who wrote this book?/#Who has written this book?

- (27)

- (Pointing at a church, without any contextually salient past time:)

- Who built this church?/#Who has built this church?

- Borromini built this church./#Borromini has built this church.

- (28)

- (Uttering the sentence knowing that we already have the technology of printing. There is not contextually salient past time.)

- The art of printing was discovered by Gutenberg./#has been discovered

- (29)

- (Mary enters the office. She opened the window an hour ago, but now it is closed. She asks:)

- Who closed the window?/#Who has closed the window?

- (30)

- (Mary is looking at a huge mess in her kitchen. She asks her roommates angrily:)

- Who did this?/#Who has done it?

In each of these examples, it is true that the Common Ground entails a state which must have followed from a previous change-of-state event (be born, get, write, build, etc.). Given this perceivable result state, it automatically follows that there is a unique change-of-state event. I argue that I argue that this information is equivalent to the Common Ground entailing a unique past interval that corresponds to the time span of that unique change-of-state event.

In other words, the reference time in these examples is the time span of the unique change-of-state event that gives rise to a state in the Common Ground. Since time is dense, there can be infinitely many large intervals in which the unique change-of-state event is located. In order to guarantee uniqueness and be formally precise, I adopt von Fintel et al.’s (2014) notion of maximal informativeness with respect to a property q.

- (31)

- Maximal informativeness

- For a temporal property q⟨i,st ⟩, a time interval t is maximally informative w.r.t. q in w iff

- a.

- q(t)(w) = 1, and

- b.

- For all other t′ such that q(t′)(w) = 1, we have

- {w′|q(t)(w′) = 1} ⊆ {w′′|q(t′)(w′′) = 1}.

- i.e. t is maximally informative if q(t)(w) = 1, and the proposition q(t) entails the proposition q(t′) for any other t′.

Here, we can define q as:

- (32)

- Temporal property to determine the unique reference time for change-of-state events (cos)

- λt.λw.∃e[τ(e) ⊆ t]

- where e is the change-of-state event which gives rise to the current state.

In other words, the first group of contexts where the presupposition of the unique past tense can be summarized as:

- (33)

- Unique reference time for change-of-state events

- If the context satisfies:

- a.

- There is a unique change-of-state event e which gives rise to some state in the context;

- b.

- The event under discussion is that change-of-state event;

- then the reference time is the (unique) maximally informative time interval with respect to: ∃e[τ(e) ⊆ t] in the actual world w0, where e is the unique change-of-state event, satisfying the uniqueness presupposition of the past tense.

3.2 Events assumed to have taken place

The other group of data where the past tense is obligatory even without a previously mentioned past reference time is shown in (34). Unlike the examples in the previous subsection, these examples do not involve a perceived change-of-state event.

- (34)

- (Uttered without contextually salient past times:)

- a.

- (We know Sheldon is an adult.)

- Sheldon was raised in Texas.

- b.

- (Leonard is currently in his late twenties and we know that he has a degree:)

- Leonard went to Princeton.

- c.

- (Penny is currently in her late twenties:)

- Penny didn’t go to college.

- d.

- (Bill is currently in his late twenties:)

- Bill didn’t finish high school.

- (Zhao 2019: modified)

These examples suggest that we need a different mechanism to derive the reference time in these sentences. Let us consider what they have in common. In (34a), we know that there must have been such a time during which Sheldon was a child. In (34b), the speaker is assuming that Leonard indeed went to university, and the reference time is the interval corresponding to his university years. In (34c), on the other hand, the reference time is the interval in which Penny could have gone to university, except that she did not actually go, unlike in (34b). The same applies to (34d), where Bill is assumed to have been in high school and he was supposed to have graduated. The assertion is that he did not actually graduate during that time.9

Unlike in the existential past analyses, the past reference time is not asserted as new information, but rather as a background assumption. I argue that, like the examples in the previous subsection, the past reference time is also presupposed to exist in these examples, and they also satisfy uniqueness. In particular, the context entails that there is a unique past interval in which a particular event is expected or assumed to have taken place, but it may or may not actually did.

The following example further confirms that the reference time should be presupposed rather than asserted:

- (35)

- Mary is 12. #She didn’t go to university.

In (35), if the past tense here is simply existential, the sentence should be just true: there does not exist a past interval in which Mary goes to university. However, native speakers judge (35) to be infelicitous instead of simply true or redundant. Following the reasoning presented above for (34), (35) is infelicitous because Mary is only 12, and our world knowledge tells us that we probably cannot find a past interval in which she was supposed to be in university. (37) shows that if the context entails information that licenses this assumption, the past tense improves.

- (36)

- (Mary is a twelve-year-old child prodigy. Her school usually recommends children like her to attend university classes by the end of the fourth grade.)

- But Mary didn’t go.

We can compare the past tense with the present perfect for this reading. The present perfect version of (35) here is fine, without the oddness of (35):

- (37)

- Mary is 12. (Of course) she hasn’t been to university.

The contrast between (35) and (37) further suggests that the present perfect here has the simple existential reading (cf. the existential perfect in Iatridou et al. (2003: a.o.)), without the presupposition of the past tense sentence.

Unlike the change-of-state examples in the previous subsection, the reference time for these expected and assumed events can be accommodated more easily. Whether accommodation takes place affects the felicity of the present perfect. (38) illustrates the subtle difference between the present perfect and the past version of the same sentence.

- (38)

- (I’m introducing my friend Alex to another friend. There is no contextually salient past time:)

- a.

- This is Alex. She didn’t go to university.

- b.

- This is Alex. She hasn’t been to university.

(38a) sounds a bit more condescending, because it has an assumption that there is a past time in which Alex could/should have gone to university, but she did not for some reason. (38b) does not rely on this assumption. In the former case, the listeners also need to accommodate this assumption upon hearing the past tense. This judgment is further confirmed by the following example, where the past tense is strongly preferred:

- (39)

- (Bill, who is 25, comes from a family that greatly values education. All his siblings have a degree.)

- But Bill didn’t go to/hasn’t been to university.

Since Bill is already 25 years old, given what we know about his family, he was probably expected to enroll in college when he was about 18. The sentence then asserts that he did not actually go during that time. The present perfect sentence, on the other hand, does not make an assertion about that past interval, and simply asserts that Bill hasn’t been to university (yet).

Having concluded that these examples indeed involve a presupposed past reference time, let us now consider how this interval is unique. Like before, we can adopt maximal informativeness. In plain words, the reference time in these examples should be the unique maximally informative interval with respect to a temporal property like λt.λs.t is a past interval in which some P-event should have taken place, according to the stereotypical expectations in s. Since it is not necessary that a P-event actually takes place in the actual world w0 (e.g. Bill did not actually finish high school although there was a time interval in which he should have), an accurate definition requires the use of ordering sources (Kratzer 1981: a.o.) which enables us to rank how well a world complies with the stereotypical expectations (accessed from the actual world), illustrated below.

- (40)

- Ordering source and the set of best worlds

- a.

- The ordering source is a function that assigns to any evaluation world w a set of propositions S, whose truth is demanded by a set of rules in w.

- b.

- For a set of worlds W and any pair of worlds w1, w2 from W, we say that w1 is ‘better’ than w2 iff w1 makes more propositions from S true than w2 does. This defines a partial order <S on W:

- ∀w1, w2 ∈ W, w1 <S w2 iff {p ∈ S | p(w2) = 1} ⊂ {p ∈ S | p(w1) = 1}.

- c.

- For any set of worlds W, the set of the ‘best worlds’ according to the set of stereotypical expectations S is MAXS(W) = {w ∈ W | ¬∃w′ ∈ W[w′ <S w]}].

Even if the evaluation world is the actual world w0 and the set of rules are the rules in w0, w0 itself may not actually be in the set of the best worlds according to this criterion. For the purpose of our proposal, the set S is inferred from our world knowledge, stereotypical expectations, as well as information available in the Common Ground: if the speaker believes that a P-event should have taken place during some past time, according to the information available in the Common Ground, then we can say that any world in which a P-event has indeed taken place at that time is better than the worlds in which this is not true. For example, in (34c), any world in which Penny actually went to university during her late teens/early twenties is better than one in which she did not.

Having defined the set of best worlds according to this standard, we can say that if the speaker believes that a P-event should have taken place at some point in the past according to world knowledge, stereotypical expectations and Common Ground information, the reference time when talking about that P-event is the maximally informative time interval t with respect to the following temporal property q in the actual world w0 (in the sense of Von Fintel et al. (2014)):

- (41)

- Temporal property to determine the unique reference time for an expected P-event (exp)

- λt.λw.∀w′ ∈ MAXS(V), ∃e[P(e) ∧ τ(e) ⊆ t] in w′ and t is connected, where:

- S is the set of propositions that satisfy the stereotypical expectations and other Common Ground information in w;

- V is the Context Set in the sense of Stalnaker (2002);

- an interval t is connected iff for any two points a, b in t, we can find connected path between a and b.

The unique maximally informative interval with respect to this temporal property will be the unique minimal time interval that would envelop all the possible τ(e)’s in those worlds in which e did happen in the past. For example, if Penny was expected to attend university at any point between her late teens to her early twenties (according to our world knowledge about what most people do), this interval will be the that entire interval. Penny may not have gone to university during that time in the actual world w0, but in the best worlds (where she did), that event would have fallen into that interval. Hence, we can use the past tense in a sentence like Penny did not go to college since the reference time would be unique.

Let us illustrate it with an example.

- (42)

- Let w be a world in the Context Set.

- a.

- Suppose the best possible worlds according to the speakers’ expectations about Penny’s education in w are:

- w1: Penny goes to university from 2015–2019

- w2: Penny goes to university from 2010–2014

- w3: Penny goes to university from 2017–2021

- (We actually don’t know if she actually went to university in w or when exactly the time was, but we know that she had a chance and it would be sensible for her to go.)

- b.

- exp

- λt.λw.∀w′ ∈ maxS(V), ∃e[P(e) ∧ τ(e) ⊆ t] in w′ and t is connected

- The unique maximally informative t with respect to exp in w, will be the interval 2010–2021.

In addition, it is important that the P-event or state is bounded (i.e. τ(e/s) ⊆ t). To see this, consider the temporal property if the event or state is unbounded:

- (43)

- λt.λw.∀w′ ∈ maxS(V), ∃s[P(s) ∧ t ⊆ τ(s)] in w′ and t is connected.

In this case we would not be able to find a unique maximally informative time interval with respect to this property. For instance, if we do not know if the state of Sheldon being a boy has ended or not, and suppose in some world in the Context Set w1, he was born in 1980, in w2 he was born in 2005. Both worlds comply with the world knowledge in the actual world w0 that Sheldon would be a child before he turns 18, and hence both are in MAXS(V). It turns out that we cannot find any time interval which is maximally informative with respect to q in w0. This is because the τ(s)’s of Sheldon’s boyhood would be disjoint in w1 and w2, and there cannot be a connected t which satisfies ∀w′ ∈ MAXS(V)∃s[Sheldon-boy(s) ∧ t ⊆ τ(s)].

I believe this is a good prediction because in all of the examples with the expected event/state, the event or state is assumed to have taken place and completed/terminated.

For sentences in (34), this analysis will give us the unique time intervals such as Sheldon’s childhood span, the time in which Leonard/Penny was at the appropriate age for university, and the time in which Bill was supposed to be in high school. I argue that these intervals are the reference times for these sentences.

We can also test this theory by constructing some new contexts, such as:

- (44)

- (It is required by law that every child receives the polio vaccine before the age of 7. There is no contextually salient past time when the following is uttered:)

- Mary (walking with her friend, passing a hospital): I was/#have been vaccinated for polio at this Hospital.

As expected, in (44), the past tense can be used without any contextually salient antecedent time. In addition, using the present perfect seems to suggest that it is not required by law that everyone must take the polio vaccine.

We can summarize the second case of uniqueness as:

- (45)

- Unique reference time for events assumed to have taken place

- If the context satisfies:

- a.

- There is a set of stereotypical expectations and Common Ground information, according to which some event is expected to have taken place in the past;

- b.

- The event under discussion is such an event;

- then the reference time is the (unique) maximally informative time interval with respect to (41) above.

3.3 Lifetime as reference time

The English past tense is also obligatorily used without an antecedent when talking about a dead person (46a), or an entity that no longer exists (46b).

- (46)

- (Uttered without a contextually salient past time:)

- a.

- Madam Curie was a physicist.

- b.

- The Northern Wei was an imperial dynasty that ruled over Northern China.

When the speakers are ignorant about whether the person/entity under discussion still exists, using the past tense without an antecedent has an inference that the the person/entity no longer exists. This inference is especially strong with individual-level predicates.

- (47)

- (Uttered without a contextually salient past time:)

- Mary was very talented.

- Inference: Mary is dead.

It is tempting to analyze the inference in (47) as a result of failing to use the present tense to describe a living person (Sauerland 2002; Magri 2011: a.o.). However, this analysis is not sufficient, because it only solves part of the puzzle, which is where the ‘Mary is dead’ inference comes from. The puzzle actually has another part, that is, why would the past tense even be considered an alternative here? Assuming that the past tense is strictly anaphoric, whether the speaker fails to use the present tense in this context should not change the fact that there is no antecedent for the reference time. We would expect (47) to be out regardless, simply due to the fact that the anaphoric past cannot be licensed. This goes back to the debate about whether the English past tense should be pronominal. The second reason is, as with perceived change-of-state events and events following stereotypical expectations, we have an asymmetry between the past tense and the present perfect in English, illustrated below.

- (48)

- a.

- #Madam Curie has been a physicist.

- b.

- #The Northern Wei has been an imperial dynasty that ruled over Northern China.

There is nothing obvious in the assertive semantics of the present perfect that prohibits these examples: it is clear that in some time span leading up to the speech time, there is a bounded state of Marie Curie being a physicist and the Northern Wei being an imperial dynasty. Since we are describing past states, these examples cannot be covered by the competing present tense analysis. We will also need to derive the infelicity of the present perfect. In addition, as Matthewson et al. (2019) point out, simply allowing the English past tense to spell out a perfect aspect as in Kratzer (1998) will not be helpful.

- (49)

- (Talking about Einstein. There is no contextually salient past time.)

- a.

- Einstein visited Princeton.

- b.

- #Einstein has visited Princeton.

- (50)

- (Talking about Princeton. There is no contextually salient past time.)

- a.

- #Princeton was visited by Einstein.

- b.

- Princeton has been visited by Einstein.

(49)-(50) are a set of famous examples illustrating how the topic can affect the felicity of the tenses. In both examples, there is no contextually salient past time that would license the anaphoric use of the past tense. However, in (49), given the common knowledge that Einstein is no longer alive, the past tense is chosen over the present perfect. In (50) where the topic is Princeton (which still exists), we observe the opposite pattern. There are various proposals in the literature on the present perfect that try to derive this pattern, such as Inoue (1979), Michaelis (1994), Katz (2003), Portner (2003; 2011). These two examples are particularly difficult to explain, due to the fact that the events described are exactly the same (Einstein visiting Princeton).

I argue that the past tense is obligatory in all the examples above because the uniqueness presupposition is satisfied. The reference time is taken to be the lifetime or the time span of the person/entity under discussion, which is a unique interval.

In this case, the relevant temporal property is:

- (51)

- Temporal property to determine the unique lifetime (life)

- λt.λw.∃s[Einstein-alive(s) ∧ t ⊆ τ(s)]

The unique maximally informative interval t is then the largest possible interval such that Einstein is alive throughout t (i.e., t ⊆ τ(s)), namely, the entire span of Einstein’s life τ(s).

We can summarize the third case of uniqueness as:

- (52)

- Unique reference time as lifetime

- If the context satisfies:

- a.

- The person or entity under discussion no longer exists;

- then the reference time is the (unique) maximally informative time interval with respect to (51) above.

3.4 Regarding identification and other data points

There is a group of data worth mentioning. It has been noted by Heny (1982) and Partee (1984) that the speakers do not need to identify the past reference time to utter the following sentences.

- (53)

- How did Cicero die?

- He was executed by Marcus Antonius.

- (54)

- Shakespeare said ‘In many’s looks the false heart’s history is writ.’

Partee (1984: p296) comments that ‘[the hearer does] not have to know when it happened to know who did it, given that it could only have happened once if it happened at all. In [this] case, the reference time could potentially be the whole of the past.’ These examples are later used by Michaelis (1994) as evidence that the English past tense is unmarked for anaphoricity. She comments that ‘when a sentence has a reference time equated with the whole of the past, the sentence in essence lacks a reference time.’

Under my analysis, both (53) and (54) would be instances of the uniqueness reading. Both the reference times are unique (the lifetime of Cicero or Shakespeare), and the asserted events are located in that time.

There seems to be an implicit assumption in these previous accounts that if the reference time cannot be identified, then it is not an anaphoric reading. However, it seems that identification is not necessary in general, even for the anaphoric reading. The classic stove example in Partee (1973) is felicitous in contexts like the following:

- (55)

- (At the office, Bill suddenly tells his friend:)

- I didn’t turn off the stove!

The sentence is naturally interpreted as about the ‘20 minutes before Bill left the house this morning’. The speakers do not need to first have that interval in mind (or as a topic), since this interval should be easily accommodated given the speakers’ world knowledge. The speakers also do not need to know when exactly Bill left the house.

Similarly, a sentence like (56) sounds perfectly natural, despite the absence of an explicit past time.

- (56)

- (Two friends meet up after a long time.)

- How are you?

- I bought a new car!

The reference time of the past tense sentence is naturally interpreted as about ‘the past interval since we last saw each other’. Again, the speakers do not need to identify the exact date they last met. This example does not seem so different from the stove example above in this sense. In the stove example, there are (infinitely) many intervals in the past during which the speaker did not turn off the stove. In (56), likewise, the speaker could have bought a car many times before they last met, but the assertion is really only about ‘the past interval since the friends last saw each other’. A simple existential analysis without appropriate domain restriction will not be able to capture this reading. I take examples like this to reflect the anaphoric reading of the past tense just like the stove example, and it also illustrates a typical way of accommodating the antecedent time: when the speakers catch up with each other after a certain period of absence, they will be able to use that interval as the reference time.

3.4.1 Already and the past tense

There is one group of data that cannot be subsumed under the uniqueness analysis, however. It involves the use of already, and has been noted to be more prevalent in American English.

- (57)

- (There is no contextually salient past time:)

- a.

- I already told you, I’m not interested!

- (Michaelis 1994)

- b.

- Can you clean the kitchen?

- I already did. (…and I mowed the lawn too.)

The use of the past tense in these examples seems indistinguishable from the resultative use of the present perfect. Unlike the earlier examples such as (55) and (56), in (57b), it is difficult to come up with an appropriate past interval that would serve as the antecedent for the past tense. The reference time does not seem to satisfy any kind of uniqueness either.

Since these examples with already is limited to American dialects of English, I take these data as reflecting a dialectal variation or possibly a change in progress, where the past tense would have both the unique and anaphoric readings observed in the earlier sections, as well as this use with already.

3.5 Comparison with the domain of entities

The use of Maximal Informativeness to derive uniqueness and the relevant smallest and largest intervals is similar to the proposal of Von Fintel et al. (2014) for entities. They give the following definition of the definite article:

- (58)

- a.

- ⟦the ϕ⟧ is defined in w iff there is a unique maximal object x, based on the ordering ≥ϕ, such that ϕ(w)(x) is true.

- When defined, the reference of the ϕ is this maximal element.

- b.

- For all x, y of type α and property ϕ of type ⟨s, ⟨α, t⟩⟩, x ≥ϕ y iff {w|ϕ(w)(x)} ⊆ {w′|ϕ(w′)(y)}.

- (Von Fintel et al. 2014)

If ϕ is an upward monotone property, the maximally informative object will be the ‘biggest’ possible object. An example is (59).

- (59)

- a.

- the height of this tree

- b.

- ϕ = λw.λd.this tree is d tall in w

(59a) refers to the maximally informative measure with respect to ϕ, namely, the biggest possible measure d such that this tree is d-tall in w.

On the other hand, if ϕ is a downward monotone property, the maximally informative object will be the ‘smallest’ possible object. This is the case in (60).

- (60)

- a.

- the number of people sufficient to lift this piano

- b.

- ϕ = λw.λn.it is sufficient for n people to lift this piano in w

We can see that (60a) refers to the smallest possible number of people who can lift the piano in w.

This result is similar to our analysis in the previous subsections. In Section 3.1 and 3.2, the unique past tense denotes the smallest possible interval t with respect to the relevant properties, and in Section 3.3, it is the largest possible interval t.

3.6 Presupposition projection tests

We can also show that the uniqueness of the past tense is a presupposition by standard presupposition projection tests. Two typical environments where presuppositions project out are negation and yes-no questions. We can see that the existence and the uniqueness inference survives all of these environments, for both change-of-state and non-change-of-state events.10

- (61)

- Perceived change-of-state events

- (There is no contextually salient past time:)

- a.

- This church wasn’t built by Borromini./It is not the case that this church was built by Borromini.

- Inference: There is a unique maximally informative past interval in which the building event of this church can be located.

- b.

- Was this church built by Borromini?

- Inference: There is a unique maximally informative past interval in which the building event of this church can be located.

- (62)

- Events assumed to have taken place

- (There is no contextually salient past time:)

- a.

- Bill didn’t finish high school.

- Inference: There is a unique maximally informative past interval in which Bill was expected/supposed to finish high school.

- b.

- Did Bill finish high school?

- Inference: There is a unique maximally informative past interval in which Bill was expected/supposed to finish high school.

- (63)

- Lifetime/time spans

- Marie Curie wasn’t a mathematician.

- Inference: There is a unique maximally informative past interval during which Marie Curie was alive.

In addition, we also other reasons to believe that this kind of past tense cannot be existential. Chen et al. (2020) provide several diagnostics for the pronominal vs. existential past tenses. ‘The pronominal analysis of past tenses predict that they are scopeless, allow deictic, anaphoric, and bound uses, and are infelicitous without a contextual reference time. The existentially quantified analysis predicts the opposite: they have scope interactions, no deictic, anaphoric or bound uses, and are felicitous in out-of-the-blue contexts’ (Chen et al. 2020: Section 4).

Applying these tests to the English past tense, we can see that the unique past tense does not fit the criteria for the existential tense, in that it does have the bound use (see next section) and it is also scopeless, like the pronominal past. For example:

- (64)

- This church wasn’t built by an Italian.

The interpretation of the past tense in (64) is independent of the negation, just like in I didn’t turn off the stove. I take this to be a piece of evidence that both uniqueness and anaphoricity are presuppositions.

3.7 Distinguishing the unique and anaphoric presuppositions

3.7.1 Two different presupposition patterns of definites

In the discussion above, we tried to determine the reading of the past tense using mostly one criterion: whether the past tense is felicitous without a previously mentioned antecedent. Sometimes the judgement can be subtle, especially for expected events. In this subsection, I present a group of data unnoticed in the previous literature, which systematically determines which kind of presupposition the English past tense has.

In particular, the two readings of the English past tense correspond to the two readings of the definite article. One way to distinguish the anaphoric and unique definites is the presupposition projection pattern in quantified sentences.

Briefly, in a sentence of the form every A B, with B containing an anaphoric pronoun, the sentence overall still presupposes the antecedent (65), unless the antecedent is introduced in A (66).

- (65)

- Every student saw it1.

- Presupposition: There is some contextually salient (or previously mentioned) individual serving as the antecedent of it.

- (66)

- Every student who has a1 cat pets it1.

- Presupposition: none.

The same applies to an anaphoric definite. For example, the German strong article (as opposed to the weak article) has been shown to be strictly anaphoric (Schwarz 2009), and we can see that it follows the same pattern as anaphoric pronouns. In particular, in (67), the situations quantified over can be presumed to be one in which uniqueness does not hold. The uniqueness-only weak article is ruled out, yet the strong article is fine due to the presence of an indefinite antecedent in the restrictor. The sentence overall does not presuppose a contextually salient antecedent for the anaphoric strong article.

- (67)

- In

- in

- jeder

- every

- Bibliothek,

- library

- die

- that

- ein

- a

- Buch

- book

- über

- about

- Topinambur

- topinambur

- hat,

- has

- sehe

- look

- ich

- I

- #im/

- in-theweak/

- in

- in

- dem

- thestrong

- Buch

- book

- nach,

- part

- ob

- whether

- man

- man

- Topinambur

- topinambur

- grillen

- grill

- kann.

- can

- ‘In every library that has a book about topinambur, I check in the book whether one can grill topinambur.’

- (Schwarz 2009: p.242)

On the other hand, if B contains a unique definite whose uniqueness is evaluated in some situation involving A, then every A B overall presupposes that in every such situation for each A, there is a unique B.11 This is known as the ‘covarying’ reading of B with respect to A.

- (68)

- In every car, the steering wheel is on the left.

- the steering wheel is a unique definite, evaluated with respect to each car.

- Presupposition: every car has a unique steering wheel.

If the unique definite is a larger situation definite, whose uniqueness is evaluated globally, then the sentence does not have a covarying reading.

- (69)

- Everyone in this company hates the boss.

Here, the boss is the unique boss of this company, and does not vary for each person.

Before we proceed, I will first address a theoretical issue: can this contrast justify the separation of the two definite readings?

Under a familiarity-only analysis of definites, such as Heim (1982; 1983), the contrast between the non-covarying and the covarying readings of the definite in the nuclear scope of a quantifier has been attributed to global vs. local accommodation of the antecedent for the anaphoric-only definite. Under a uniqueness-only analysis, the covarying reading of a donkey pronoun or a unique definite can be accounted for with appropriate domain restriction. However, I argue that the contrast we see in (65)—(68) reflects an actual difference between the anaphoric and the unique readings, for the following reasons (some of which have been noted in the previous literature):

(i) For a sentence of the form Every A B, the observation with pronouns is that without a explicitly introduced antecedent in A, the pronoun it in B cannot possibly have the covarying reading.

(ii) The sentence (66) with an anaphoric pronoun under the covarying reading does not have a presupposition any more, while (68) with the unique definite still has a presupposition that each A must satisfy the uniqueness presupposition. If the covarying reading is simply a result of locally accommodating the antecedent under a familiarity-only ac- count, this difference is unexpected.

(iii) The antecedent-anaphor relationship between an indefinite and an anaphoric element seems to be special, and cannot be simply captured by uniqueness-only accounts with domain restriction. and it is related to the problem of the formal link in the literature (Heim 1990: a.o.). This problem is illustrated below:

- (70)

- (Assuming all couples here are in a cisgender relationship.)

- a.

- Every married woman is sitting next to him.

- # under the covarying reading.

- b.

- Every married woman is sitting next to the man.

- # under the covarying reading.

- c.

- Every woman married to a man is sitting next to him.

In (70a), the anaphoric pronoun him fails to get the covarying reading despite the possi- bility of locally accommodating its obvious antecedent, namely, the husband. In (70b), the man also fails to get this reading, despite the possibility of having a contextually supplied domain restrictor which easily restricts the situations quantified over to ones that contain just one man (namely, the husband). The infelicity contrasts sharply with the judgement for (70b), with an explicit indefinite antecedent. The only exception is relational nouns, such as the husband and the author below.

- (71)

- a.

- (Assuming all couples here are in a cisgender relationship.)

- Every married woman is sitting next to the husband.

- b.

- (Assuming that each book here has a unique author.)

- Every book is signed by the author.

Interestingly, relational nouns require the anaphoric-only strong article in German (Schwarz 2009). This suggests that relational nouns with the covarying reading are licensed via the same mechanism as anaphoric pronouns, instead of simply uniqueness.

3.7.2 Two presupposition projection patterns of the English past tense

For the purpose of this paper, the crucial observation is that under the uniqueness reading of the English past tense, the presupposition projection patterns with the covarying reading of unique definites in (68), which would be unexpected if it were strictly anaphoric.

To test this, first observe that the English present perfect can provide an antecedent for the anaphoric past tense.

- (72)

- a.

- Mary has met Sue already. She met her at a party.

- b.

- Sue has been to Egypt. She saw some pyramids.

Without getting into the details of the present perfect, I will simply use the present perfect as an indefinite in the testing the antecedent-anaphor relationship.12

The past tense in the following sentences can be uttered without a previously mentioned antecedent, illustrated in the (a) sentences below. This is the case for perceived change-of-state events (73a), expected events (74a), and lifetime (75a). The (b) sentences show that when we put the past tense under every or both, it gets a covarying reading: in (73b), each church may have been built at different times in the past, but for each church this time is uniquely identifiable and is in the past, and we see that the reference of was covaries with each church; in (74b), the context is such that we can assume each person at the gathering has a past time when they graduated from an American university, although this time is probably different for each of them; for (75b), the reference time is taken to be the lifetime of Einstein and Curie, respectively. Since there is no contextual information regarding the Nobel Prize of a particular year, the reference time cannot be that year. In addition, the two people actually won the prize in different years, which the speakers need not to know to utter (75b) felicitously. Likewise, for (76), the participants need not know anything more than the fact that these people are all dead to felicitously use the past tense. The actual birth and death dates are not important.

- (73)

- (Looking at churches in a town. There is no contextually salient past time.)

- a.

- This church was built by an Italian.

- b.

- Every church in this town was built by an Italian.

- Presupposition: For each church, there is a unique maximally informative past interval containing the construction event.

- (Satisfied.)

- (74)

- (At a gathering of alumni from several American Universities. There is no contextually salient past time.)

- a.

- This woman here graduated from an American university.

- b.

- Every person here graduated from an American university.

- Presupposition: For each person here, there is a unique maximally informative past interval in which they probably graduated from an American University.

- (Satisfied.)

- (75)

- (Knowing that Einstein and Marie Curie are no longer alive. There is no contextually salient past time.)

- a.

- Marie Curie won the Novel Prize in physics.

- b.

- Both Albert Einstein and Marie Curie won the Nobel Prize in physics.

- Presupposition: For each of Einstein and Curie, there is a unique maximally informative past interval during which they were alive.

- (Satisfied.)

- (76)

- (Talking about dead famous people from different eras–Marie Curie (20th century), Michael Faraday (19th century), Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (18th century); Archimedes (ancient Greece). There is no contextually salient past time.)

- a.

- Marie Curie made several important scientific discoveries.

- b.

- Each of these people made important scientific discoveries.

- Presupposition: For each person, we can find a unique interval identified as his/her lifetime.

- (Satisfied.)

To compare, under the strictly anaphoric interpretation of the past tense, we will not be be able to get the covarying reading. This is illustrated in (77). (77) on its non-habitual interpretation, strongly suggests a non-covarying, anaphoric reading that every boy danced during the same salient past interval (e.g. at the party last Friday).13 This patterns with the observation in (65) with pronouns.

- (77)

- Every boy danced with Mary.

- Presupposition: The utterance is about a contextually salient past interval which serves as the antecedent of the past tense.

As I mentioned above in (72), it is possible to use the present perfect as a sort of indefinite past. We can introduce an antecedent to the anaphoric past tense in the nuclear scope with the present perfect in the restrictor of every, in which case the anaphoric past tense does get a covarying reading similar to donkey anaphora, and it will not project its presupposition out (78), just like what we observed earlier with pronouns.

- (78)

- a.

- Every girl who has been to this club danced.

- Presupposition: None (under the reading that each girl danced during her visit to the club, but this visit may have happened at different times for each girl).

- b.

- Every boy who has visited Paris also went to Marseilles.

- Presupposition: None (under the reading that each boy went to Marseilles on the same trip to France, but this visit may have happened at different times for each boy).

In addition, the previous accounts reviewed in Section 2 cannot account for this contrast satisfactorily. One major issue is that they cannot control for the distribution of the ‘out-of-the-blue’ (i.e. unique past for us) use of the past tense. In addition, analyzing the past tense as existential fails to account for the presupposition projection patterns observed.

4 Unique and anaphoric definites in the tense domain

In the previous section, we established that there are data which cannot be satisfactorily explained with a pure pronominal (i.e. anaphoric) analysis of the English past tense, and we also found evidence that these instances of the past tense are actually similar to unique definites. In other words, the English past tense (with the relevant temporal property) behaves more like the definite article the (plus an NP) than pronouns.

4.1 Lexical ambiguity tests

This novel observation opens up a possibility of analyzing the English past tense on par with the analysis of definites in the recent literature, where familiarity and uniqueness are separated as sub-concepts of definiteness, and that languages may have different lexical items for each definite reading (Schwarz 2009; 2013; Jenks 2015; 2018; Arkoh & Matthewson 2013: a.o.). In these accounts, the anaphoric definite is made up of the meaning of the unique definite with an additional anaphoric index argument (y in (79)).

- (79)

- a.

- Unique definites

- λsr.λP: ∃!x[P(x)(sr)].ιx.P(x)(sr)

- b.

- Anaphoric definites

- λsr.λP.λy: ∃!x[P(x)(sr) ∧ x = y].ιx.P(x)(sr) ∧ x = y

- Schwarz (2009: (299))

For the English past tense, since both the anaphoric and the uniqueness readings are expressed with the same morphology, we may suggest a lexical ambiguity analysis. However, there is a concern: in general, even if other languages may morphologically distinguish the two readings, there is no good reason to believe that English is lexically ambiguous, in both the nominal (the) and the temporal domains (the past tense). For example, many languages distinguish different genders for pronouns morphologically, but a language like Hungarian does not. It does not follow that Hungarian pronouns are lexically ambiguous for gender. This point is not addressed in the previous discussion on this topic (cf. Grønn & Von Stechow (2016); Matthewson et al. (2019)). Apart from lexical ambiguity, we may also argue for a lexical underspecification analysis, where the English past tense is simply marked as ‘definite’, but it leaves open which kind of definite reading the tense may have.

Some commonly used tests for lexical ambiguity include: conjunction, ellipsis, and contradiction, illustrated below (Zwicky & Sadock 1975; Kennedy 2011).

- (80)

- a.

- The colours are light.

- b.

- The feathers are light.

- c.

- ??The colours and feathers are light.

- (81)

- I saw his duck and swallow under the table and I saw hers too.

- (82)

- The bank isn’t a bank.

- Intended reading: The bank (institution) isn’t a bank (of the river).

(80) tests the two senses of the adjective light (brightness and weight). In general, a conjunction construction does not allow two readings at the same time, hence the weirdness of (80c) shows that there is indeed a lexical ambiguity here.14 (81) distinguishes the bird reading and the action reading of the words duck and swallow: the elided part can only have the same reading as the previous one. (82) shows that bank is lexically ambiguity between the financial institution and the land around a river. The fact that there is no contradiction shows that this word is indeed lexically ambiguous.

If a word is underspecified, however, these tests would give us the opposite results: the conjunction would be allowed, the elided part may have the other reading, and we would observe a contradiction. For example, in English, child is underspecified for gender, and we have:

- (83)

- a.

- John has a son.

- b.

- Mary has a daughter.

- c.

- Both John and Mary have a child.

- (84)

- Mary likes her child, and John does too.

- (85)

- a.

- #John’s child isn’t a child.

- Intended reading: John’s boy isn’t a girl.

- b.

- #John has a boy, and he doesn’t have a child.

- Intended reading: John has a boy, and he doesn’t have a girl.

Similarly, NPs in classifier-languages, such as Mandarin Chinese, is underspecified for number. We have the same test results:

- (86)

- a.

- Zhangsan

- Zhangsan

- you

- has

- yi

- one

- zhi

- cl

- mao.

- cat

- ‘Zhangsan has a cat.’

- b.

- Lisi

- Lisi

- you

- has

- liang

- two

- zhi

- cl

- mao.

- cat

- ‘Lisi has two cats.’

- c.

- Zhangsan

- Zhangsan

- he

- and

- Lisi

- Lisi

- dou

- all

- you

- have

- mao.

- cat

- ‘Both Zhangsan and Lisi have cats.’

- d.

- Zhangsan

- Zhangsan

- xihuan

- likes

- ziji

- self

- de

- gen

- mao.

- cat

- Lisi

- Lisi

- ye

- two

- shi.

- cop

- ‘Zhangsan likes his single cat, and Lisi does too. (Lisi likes his own multiple “cats”)’

- (87)

- a.

- #Zhangsan

- Zhangsan

- de

- gen

- mao

- cat

- bu

- neg

- shi

- cop

- mao.

- cat

- ‘(Intended:) Zhangsan’s cat is not multiple “cats”.’

- b.

- #Lisi

- Lisi

- you

- has

- liang

- two

- zhi

- cl

- mao,

- cat

- suoyi

- therefore

- ta

- he

- bu

- neg

- shi

- cop

- you

- has

- mao.

- cat

- ‘(Intended:) Lisi has two cats, therefore it’s not the case that he has a single cat.’

The general patterns of lexical ambiguity and underspecificity with respect to the tests are summarized below:

| Lexical ambiguity | underspecification | |

| Conjunction | # | ✔ |

| Ellipsis | same interpretation only | different interpretations allowed |

| Contradiction | ✔ | # |

4.2 Conjunction test

Testing the English past tense for the two readings can be tricky, because even if we have conjoined NPs as an argument of the VP, there is still one tense in the sentence. However, we can still construct some examples, such as the following. Imagine that we are in Florence, and the speaker is pointing at the famous dome of the Florence Cathedral. The background information is that both Brunelleschi and Ghiberti were involved in the project in 1418, but Ghiberti was only briefly involved and Brunelleschi eventually got all the credit for the construction of the dome:

- (88)

- (Pointing at the dome of the Florence Cathedreal:)

- Who built this dome? And what did Ghiberti do in 1418?

- ??Ghiberti and Brunelleschi built this dome.

- (89)

- Answering two questions at the same time

- What did Penny do Monday night? And what about Leonard?

- They both hung out with Sheldon (on Monday night).

Here, it is impossible for the past tense to both be unique (as in Brunelleschi built this dome) and anaphoric to the antecedent 1418 (Ghiberti built this dome in 1418). Note that here, the oddness cannot be due to answering two questions at once, which is in general allowed (see (89)). The only possible issue here is that maybe the building event of the dome lasted many years and not just in 1418, so the unique reference time may be a longer time interval. To avoid this complication, let us construct an example that involves a smaller time interval.

Consider the following example. Here the background information is that Marie Curie and Pierre Curie were both involved in the discovery of radium in 1898.

- (90)

- Who discovered radium? And what did Pierre Curie achieve in 1898?

- ?Marie Curie and Pierre Curie discovered radium in 1898.

Here, the sentence is again odd despite the fact that there is nothing wrong with the statement itself. Again, I take it to be a clash between the two senses of the past tense, in particular, their different presuppositions. From the discussion in the previous sections, we conclude that sentences with the unique past tense in general presupposes the existence and the uniqueness of past interval (but crucially not which interval it exactly is).

This presupposition is satisfied when the speakers talk about the discovery of a substance known today. Hence, (90) with the unique past tense has the discovery event (and the unique reference time) as old information, and both Marie Curie and Pierre Curie and in 1898 as new information. On the other hand, the same sentence as an intended answer to the second question, requires the past tense to be interpreted anaphorically, the old information now is the (exact identity of the) reference time in 1898 and one of the agents Pierre Curie, and both the discovery event and the additional agent of that event Marie Curie are now new information. As a result, (90) is judged as infelicitous because having the two senses of the past tense in one sentence requires something to be both old and new information at the same time.

A related point here is that even without the conjunction, a sentence like Marie Curie discovered radium cannot answer both a question with a unique past tense (Who discovered radium?) and an anaphoric one (What did Marie Curie achieve in 1898?). This is because the different presuppositions and assertions will trigger two conflicting stress patterns:

- (91)

- a.

- Who discovered radium?

- MARIE CURIE discovered radium.

- b.

- What did Marie Curie achieve in 1898?

- Marie Curie discovered RADIUM.

If we take away the temporal adverbial in 1898 from the answer in (90), speakers judge it to be only answering the first question, despite the fact the Pierre also appears as the agent of the event, and in principle, the sentence should be able to answer the second question.15 I take this as another piece of evidence that a single instance of the past tense cannot get both the uniqueness and the anaphoric readings at the same time.