1 Introduction

The goal of this paper is to advance a unified analysis of the diachronic evolution of possessive phrases in Romance languages. Most current analyses for different Romance languages are based on the following empirical picture: in languages such as French or Spanish there is an emerging ban on the co-occurrence of prenominal possessives with overt determiners while in others, such as Portuguese and Italian, there is a emerging requirement of their co-occurrence (Alexiadou 2004, among others). A quantitative study by Butet (2018) shows, however, that in historical French, which features two morphologically distinct paradigms of prenominal possessives, forms from the so-called long paradigm tend to co-occur with determiners more frequently than the so-called short ones. This paper presents novel quantitative data and statistically examines quantitative profiles of co-occurrence with determiners for short and long prenominal possessives in French, Spanish, and Portuguese. These data show that there is indeed a quantitative difference between the two paradigms and that the difference can be represented as a successful spread of determiners with long forms and a failed spread, in the sense of a failed change of Postma (2010), with short ones. It is also shown that across these three Romance languages, the two paradigms evolve in a strikingly similar way with respect to the co-occurrence with determiners.

All early medieval Romance languages feature prenominal possessive morphemes which can co-occur with determiners in the prenominal position. Examples (1)–(3) illustrate this for medieval French, Spanish, and Portuguese.

- (1)

- medieval French

- la

- def

- tue

- your

- aname

- soul

- el

- in.def

- ciel

- heaven

- seit

- be.sbjv

- absoluthe!

- absolved

- “…that your soul may be absolved in heaven!” 10XX-ALEXIS-PENN-V,82.751

- (2)

- medieval Spanish

- Bevemos

- we.drink

- so

- their

- vino

- wine

- e

- and

- comemos

- we.eat

- el

- def

- so

- their

- pan

- bread

- “We are drinking their wine and we are eating their bread.” Cid, 1104, cited from Ishikawa (1997: 62)]

- (3)

- medieval Portuguese

- u

- where

- o

- def

- seu

- his

- nome

- name

- era

- was

- escrito

- written

- “… where his name was written.” Graal,1245, cited from Labrousse (2018: 1620)

The evolutionary outcome for this configuration is different for each language. In Modern French and Spanish, prenominal possessives never co-occur with determiners, as (4) and (5) show.

- (4)

- Modern French

- Que

- That

- (*la)

- def

- ton

- your

- âme

- soul

- soit

- be.sbj

- absolue !

- absolved

- “That your soul may be absolved!”

- (5)

- Modern Spanish

- Puedes

- you.can

- tomar

- take

- (*el)

- def

- mi

- my

- libro

- book

- “You can take my book.”

European Portuguese, along with other Romance languages such as Italian, that we do not consider here, took a seemingly opposite path: Modern European Portuguese requires that prenominal possessives be accompanied by a determiner, as in (6).

- (6)

- Modern (European) Portuguese

- *(Os)

- def

- meus

- my

- dias

- days

- são

- are

- melhores

- better

- que

- than

- as

- def

- vossas

- your

- noites

- nights

- “My days are better than your nights.” From Miguel (2002: 221)

The (non)co-occurrence property has been analysed as evidence of the morphosyntactic status of possessives. Lyons (1985) draws a distinction between adjectival (co-occurring) and determiner-like (non-co-occurring) possessives and adjectival-genitive-languages and determinative-genitive languages, respectively. The same distinction, based on the (non)co-occurrence pattern, is drawn in Schoorlemmer (1998). Schoorlemmer (1998) argues that in languages where the functional head Pos is specified with [+definite] feature, the possessive form moves from Spec,PosP to D, thus precluding the insertion of another determiner, whereas in languages where Pos does not carry [+definite], no such movement happens, making possible co-occurrence with a determiner.1 Cardinaletti (1998) distinguishes between three types of adnominal possessives: strong possessive adjectives, weak possessive adjectives, and (clitic) possessive determiners. While the former two types can co-occur with determiners, the latter cannot because, according to Cardinaletti (1998), it syntactically incorporates into D, which makes the use of another determiner impossible. Ihsane (2000), likewise, identifies three types of possessives. The first one are determiner possessives, which move from AgrPossP to the DP layer, because of their [+definite] specification and therefore compete with definite and indefinite determiners.2 The second type are adjectival possessives, not marked with [+definite] and therefore not moving to the DP. The hallmark of this class, as in other classifications, is their ability to co-occur with determiners. The third type are pronominal possessives, occurring without nominal heads, which we do not consider in this paper.

On this view, the contrast between (4)–(5) on the one hand and (6) on the other indicates that in French and Spanish prenominal possessives acquired a [+definite] feature or switched their status from adjectival to determiner-like (e.g. Alexiadou 2004; Van Peteghem 2012), while in Portuguese (and other languages with similar patterning) they did not.

We argue, however, against the reanalysis of prenominal possessive morphemes. Taking as a starting point the observation made by Butet (2018) for historical French that the two morphologically distinct possessive paradigms in this language co-occur with determiners at different frequencies, we examine short and long paradigms separately in large historical treebanks and morphologically annotated corpora of French, Spanish, and Portuguese. We show that all nominal expressions, including all possessive phrases, in the Romance languages under consideration underwent the same change, viz. a rise in frequency of overt determiners. Uniformly across the three languages, this change succeeded with one type of prenominal possessive morphemes, long possessives, and failed with another, short possessives. We further analyse the spread of determiners with possessives, both failed and successful, in terms of a pan-Romance shift from an (extended) NP grammar, which characterized their Latin ancestor that did not have articles, to a DP grammar, the latter involving a systematic use of morphological triggers of existential presupposition at the nominal level.

This paper focuses on prenominal possessives because it is in the prenominal position that we register evolutionary changes in the co-occurrence of possessives and determiners.

The paper is organized in the following way. In the next three sections we present philological and quantitative data on the distribution of short and long prenominal possessives in French (section 2), Spanish (section 3) and Portuguese (section 4). We present syntactic and semantic details of the proposed unified account in section 5 and conclude in section 6.

2 French

In this section we present novel quantitative corpus evidence suggesting that the pan-Romance rise in determiner frequency proceeded very differently with two different morphological types of possessives in French, short and long. Along with other descendants of (Vulgar) Latin, the earliest documented stages of French (ca. ninth c.) show that at that point the language did not make use of determiners in the same way Modern French does. This situation is entirely expected since Latin did not have any consistent (in)definiteness marking, the absence of nominal determination being largely dominant (see Carlier & Lamiroy (2018) for quantitative data, based on a small corpus). In older stages of Romance languages we find bare nouns in contexts which strictly require a determiner in today’s varieties. In particular, it can be observed that over time the frequency of determiners grows in the context which require them in Modern French (see Simonenko & Carlier (2020b) for quantitative data and statistical modeling of this evolution from the ninth to the fourteenth c.). In contrast, while in older stages we observe determiners in the context of prenominal possessives, the frequency of such co-occurrences seems to go down with time and reaches zero in Modern French. We show in this section that the latter generalization is empirically inaccurate, and that we need to take into account that Old French had two morphologically distinct paradigms of prenominal possessives, a fact well-known from the grammatical descriptions but whose quantitative ramifications we can evaluate only now with the help of treebanks and statistical modeling techniques.

2.1 Two possessive paradigms

Old French features two morphologically distinct paradigms of prenominal possessive morphemes. The two paradigms are illustrated for the first person possessives in Tables 1, 2 from Buridant (2019: 219). We label the paradigms “short” and “long” as pre-theoretical descriptions referring only to their relative phonological weight.3 By the end of the fourteenth century, long forms virtually go out of use.4

Old French short prenominal possessive forms.

| singular | plural | |||

| nominative | oblique | nominative | oblique | |

| masculine | mes | mon | mi | mes |

| feminine | ma | ma | mes | mes |

Old French long prenominal possessive forms.

| singular | plural | |||

| nominative | oblique | nominative | oblique | |

| masculine | miens | mien | mien | miens |

| feminine | meie | meie | meies | meies |

We investigate the distribution of the two series in the treebanks of Martineau et al. (2010) and Kroch & Santorini (2021).5 We extracted from these corpora all noun phrases with possessives in 1st, 2nd, or 3rd person singular (N = 25,104 noun phrases), since only these distinguish between short and long forms. Figure 1 shows the relative frequency of the two paradigms across time.

There is no consensus in the literature as to whether or to which extent the morphological contrast is a reflection of syntactic and semantic differences. Gamillscheg (1957) argues that the choice between the paradigms is governed by metrical considerations only.6 Arteaga (1995) notes that the two types can be coordinated, which suggests their syntactic and semantic equivalence. In contrast, Butet (2018) and Buridant (2019) argue that the two series differ with respect to the possibility of co-occurrence with determiners: while short forms tend to not co-occur, long forms tend to do so. Butet (2018) takes the co-occurrence to be a hallmark of an adjectival status, and absence of co-occurrence as a signature of the determiner status. Our corpus data show that while both types of possessives do occur with and without determiners, diachronic trajectories differ dramatically.

2.2 Co-occurrence with determiners

Examples (7) and (8) illustrate co-occurrence of a short form tos and a long form tuen, respectively, with an l-determiner (i.e., le/la/les).7

- (7)

- Los

- def

- tos

- your.short

- enfanz

- children

- qui

- that

- in

- in

- te

- you

- sunt,

- are

- a

- to

- males

- bad

- penas

- pains

- aucidront;

- succumb

- “Your children inside you will succumb to violent pains”. 1000-PASSION-BFM-P,100.41

- (8)

- E

- and

- tantes

- many

- lermes

- tears

- pur

- for

- le

- def

- tuen

- your.long

- cors

- body

- plurét

- cried

- “And she shed so many tears after you.” (10XX-ALEXIS-PENN-V,95.860)

Examples (9) and (10) illustrate co-occurrence of short and long forms, respectively, with indefinite determiners.

- (9)

- il

- he

- aueit

- had

- un

- a

- sol

- single

- cheual

- horse

- qu

- which

- il

- he

- balia

- took

- a

- to

- un

- indef

- son

- his.short

- parent.

- relative

- “he had a single horse, which we had taken from a relative of his.” 122X-PSEUDOTURPIN-P-MCVF,270.180

- (10)

- Mais

- but

- uns

- one

- siens

- his.long

- moines

- monk

- donat

- gave

- sa

- his.short

- pense

- thought

- a

- to

- mobiliteit,

- mobility

- “But one of his monks was planning to leave.” 1190-DIALGREG2-BFM-P,92.815

In Modern French, co-occurrence of (short) possessives with any determiner type is strictly ungrammatical, as (11) and (12) illustrate.

- (11)

- Modern French

- Que

- that

- (*la)

- the

- ton

- your

- âme

- soul

- soit

- be

- absolue!

- absolved

- “That your soul may be absolved!”

- (12)

- Modern French

- Il

- he

- veut

- wants

- parler

- speak

- de

- of

- (*un)

- a

- son

- his

- fils.

- son

- “He wants to talk about his son.”

Modulo the claim by Butet (2018) that short and long possessives co-occur with determiners at different frequencies, it has been commonly assumed that the general trend in the co-occurrence pattern is that of a continuous decrease in the frequency of determiners in noun phrases with prenominal possessives. As mentioned above, this has been taken to indicate a progressive reanalysis of prenominal possessives from adjectives, capable of co-occurrence, to determiner heads, incompatible with another determiner. There has been however no large-scale quantitative studies testing the original empirical assumption underlying the reanalysis view. In order to carry out such a quantitative study, we fit logistic regression models of the form in (13) to three datasets: noun phrases with short possessives (N = 24,607 noun phrases), noun phrases with long possessives (N = 497 noun phrases) and noun phrases without possessives (N = 186,768 noun phrases).

- (13)

The logistic function, which describes processes that have phases of a slow take-off, rapid growth, and again a slow attenuation, has been identified as a model particularly suitable for capturing successful language changes (see Altmann et al. (1983); Kroch (1989); Niyogi & Berwick (1997); Kauhanen & Walkden (2018) for details). In our case, the model predicts the probability that the binary variable Determiner takes on the value yes given variable Date as a predictor. The coefficient β reflects the importance of the time factor for predicting the determiner probability, while α corresponds to the predicted probability at an (idealized) time point 0. By estimating the parameters of a model fitted to our data on the determiner-possessive co-occurrence and also by comparing the performance of this predictive model and an alternative one which describes non-monotonic processes, we can evaluate to which extent the assumption about a steady co-occurrence decrease is reliable.

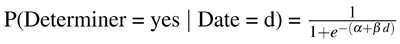

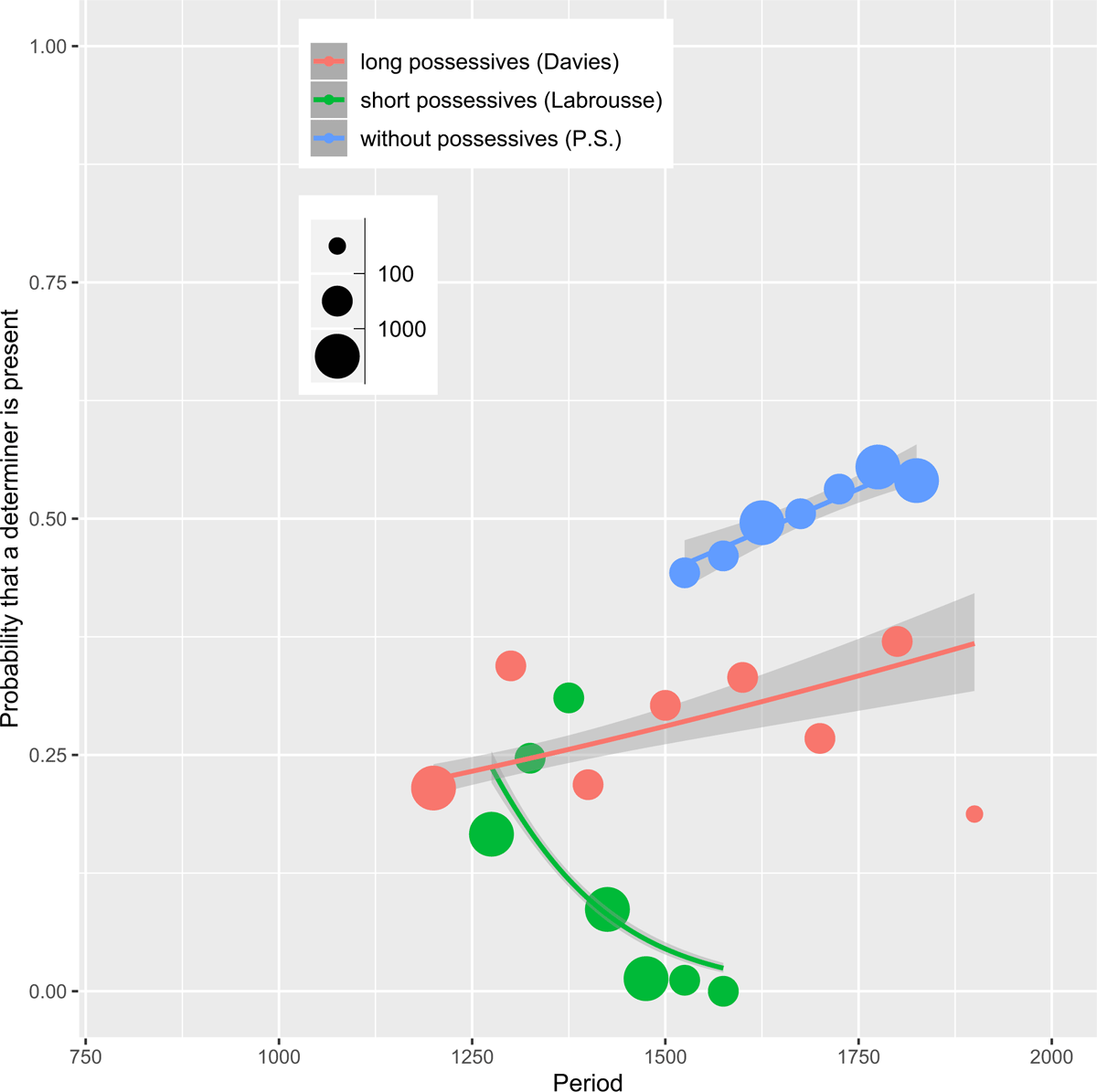

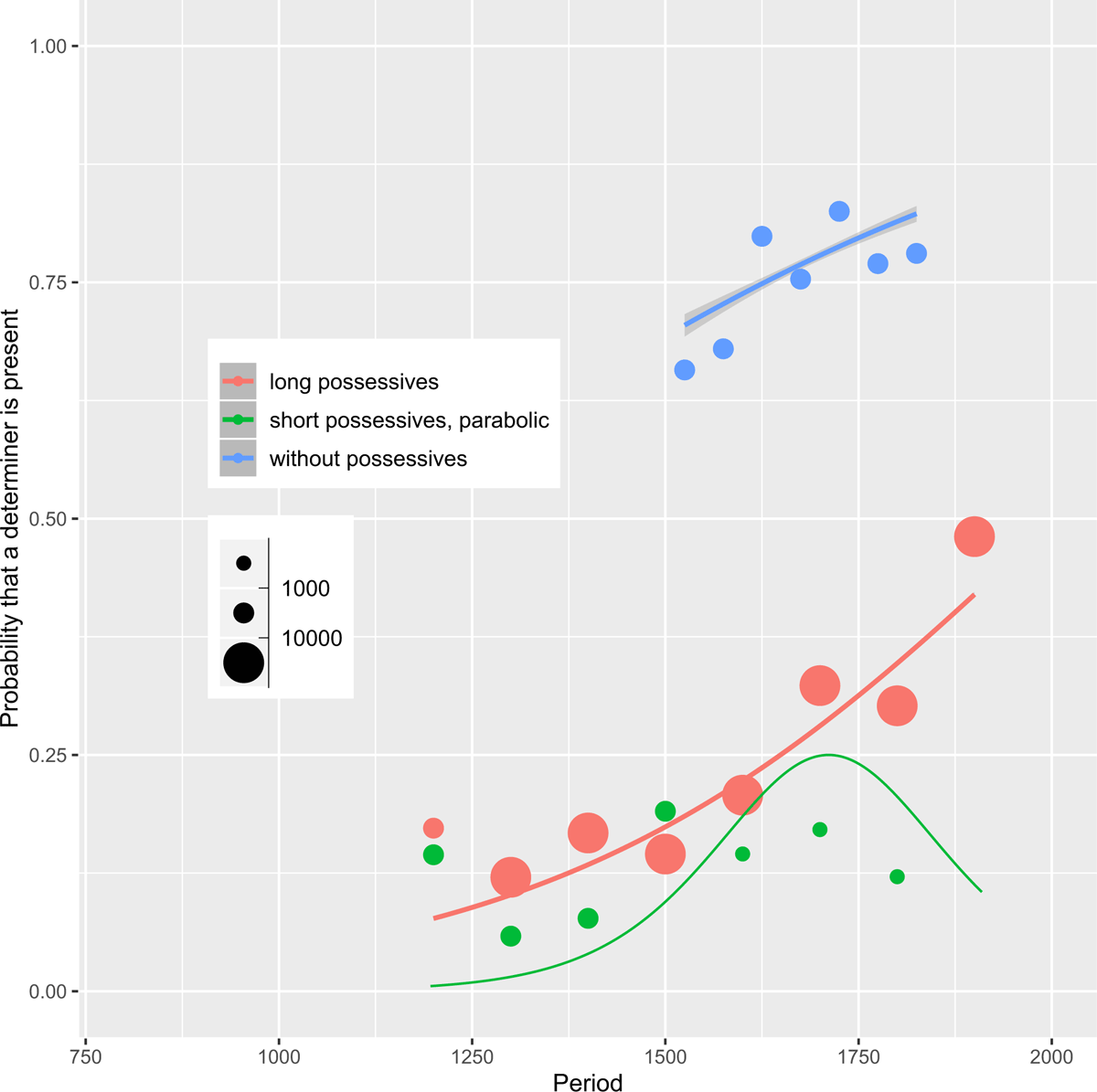

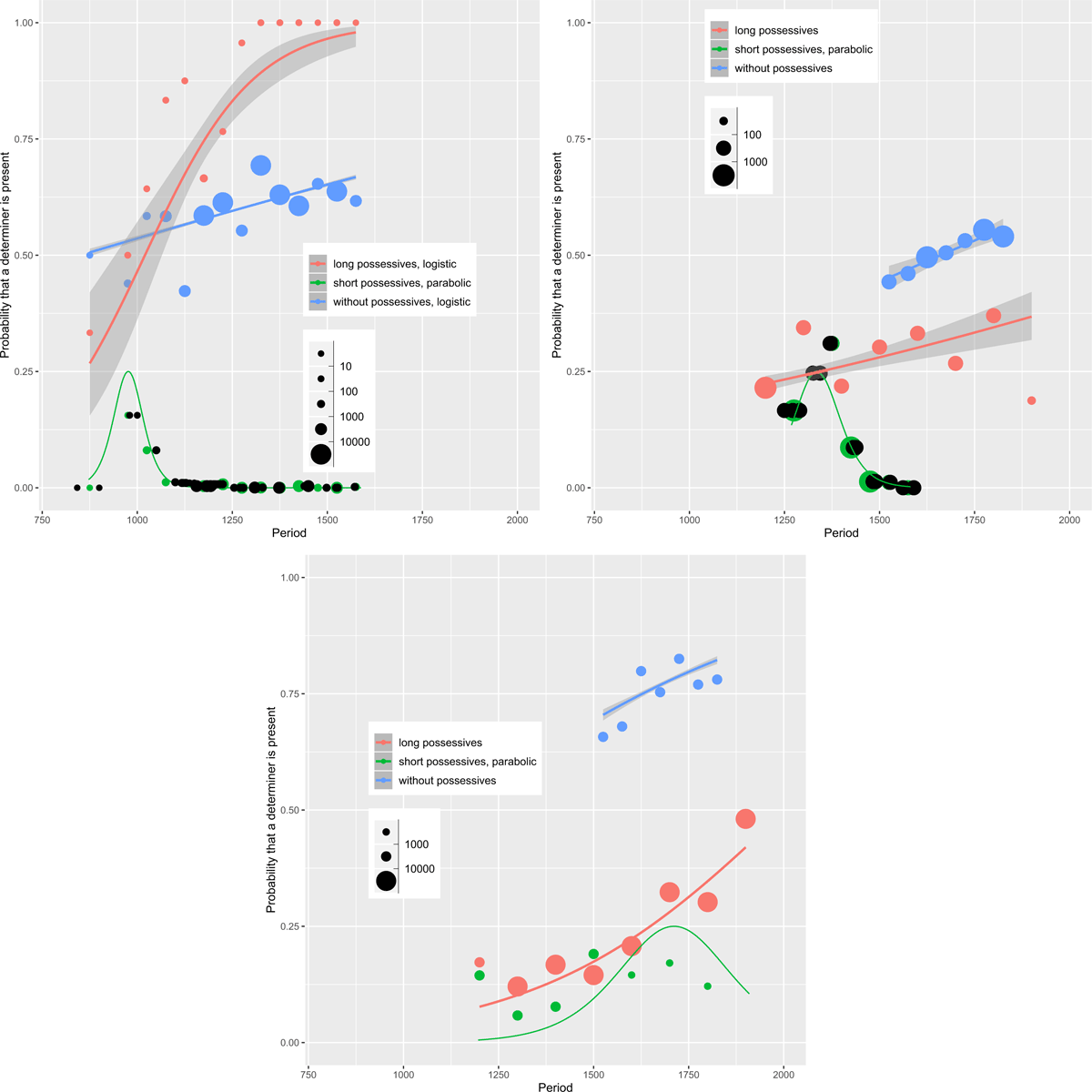

The three logistic regression models are plotted in Figure 2 together with data points which correspond to the empirical frequencies of determiners in the three types of noun phrases in 50 year intervals.8 For model fitting, we used a normalized time period variable, to facilitate comparisons across languages, since different time spans are available for observation in each case.

The parameter estimates for the three models are given in Table 3.

Logistic model parameter estimates for French.

| Possessives | no | long | short |

| Intercept | 0.4243 | 1.8539 | –6.1032 |

| Std. Error | 0.0047 | 0.1772 | 0.1616 |

| z-value | 89.49 | 10.460 | –37.778 |

| p-value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | <0.001*** |

| Time coefficient | 0.1221 | 0.9064 | –1.2242 |

| Std. Error | 0.0048 | 0.1496 | 0.1485 |

| z-value | 25.60 | 6.061 | –8.245 |

| p-value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | <0.001*** |

The model fit to the dataset without possessives detects a significant rise in the use of determiners (time coefficient = 0.1221, p < 0.001***). This means that the likelihood that the perceived diachronic trend is due to chance and that the weight of the time factor is zero is very small. That the coefficient is positive means that that for the higher values of date the model predicts higher probabilities of determiner appearance or, put differently, that the frequency of determiners increases over time in noun phrases without possessives. This matches the results presented in Simonenko & Carlier (2020b) on the general increase in the frequency of determiners in historical French.

In the dataset with long possessives we find a similar trend. The frequency of determiners in noun phrases with long possessives increases in Old French at a statistically significant positive rate (time coefficient = 0.9064, p < 0.001***). This means that at least for the long possessives, the assumption about co-occurrence decrease is wrong. It appears that the frequency of determiners in noun phrases with long possessives goes towards its maximum about the same time that they disappear from the language.

The dynamics of the co-occurrence pattern in noun phrases with short possessives are more complex. In this case, the model detects a significant decline in determiner use (time coefficient = –1.2242, p < 0.001***). On the face of it, this result matches the assumption about a steady co-occurrence decrease. In the following section, however, we present both statistical and linguistic arguments suggesting that a monotonic decrease assumption may be erroneous for the short possessives as well.

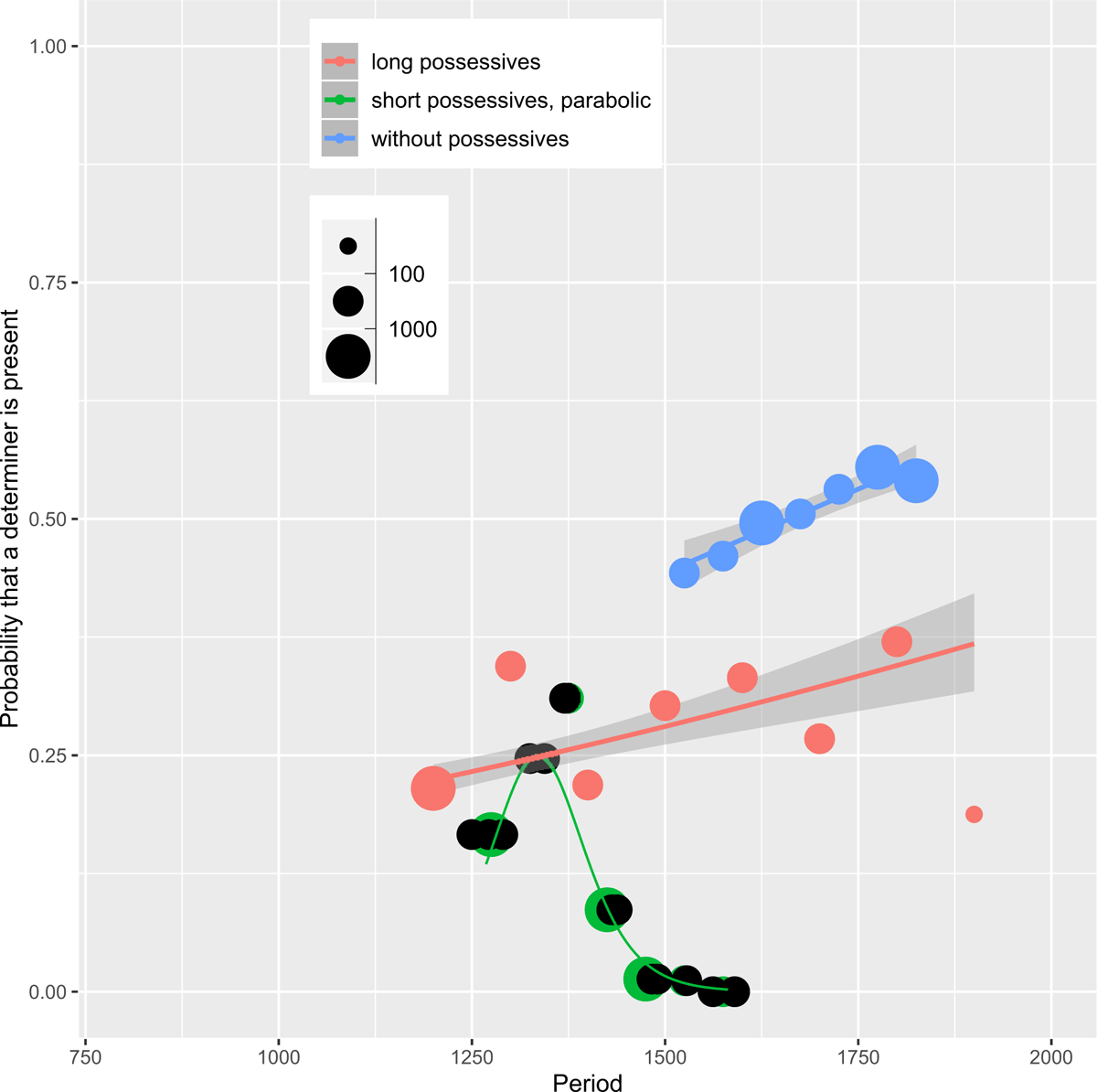

2.3 A failed change

Although the model fitted to the noun phrases with short possessives detects a diachronic trend, it does not fit the data particularly well for the texts composed before 1000. Moreover, the distribution of data points that correspond to individual texts (in black in Figure 3) makes one suspect a different, non-monotonic trend, namely, the rise of the co-occurrence frequency before 1000 and a decline afterwards. Such a trend is entirely expected given the general philological reasoning. While Classical Latin did not have a consistent marking of (in)definiteness, from Late Latin onwards, definiteness marking at the noun phrase level increases (Carlier & De Mulder 2010). This increase continues in Old French, in the form of the definite determiner derived from Late Latin demonstrative ille (Simonenko & Carlier 2020a). It is therefore highly plausible that, in comparison with the Classical and even Late Latin baseline, the stage of the determiner loss in noun phrases with short possessives that we clearly observe in Old French after 1000 has been preceded by their rise in this context before 1000. We therefore suggest that instead of a steady decline in the frequency of short possessive-determiner co-occurrence, a rise-and-fall or a bell-shaped pattern should be assumed. The rise-and-fall evolution hypothesis is all the more plausible in view of the fact that the possessive only rarely co-occurs with a (demonstrative) determiner in Latin (including in Late Latin). In general, the rate of bare nouns in Classical Latin has been estimated to be 77% (Carlier & Lamiroy 2018), while at the beginning of the Old French period it is down to approximately 40% (Simonenko & Carlier 2020a). The empirical question at stake here is whether the rise-and-fall pattern can be detected in the observable time period, that is, after 800, or whether the rise of determiners with short possessives precedes the earliest preserved records in the vernacular. In what follows, we will formally evaluate the assumption that the rise-and-fall can be observed in the available data.

An initial rise in the frequency of a particular grammatical phenomenon followed by its decline has been referred to as a “failed change” pattern since Postma (2010). A failed change is not a particularly rare phenomenon. On the basis of data presented in Oliveira e Silva (1982), Postma (2010) argues that in Brazilian Portuguese, the frequency of determiners in noun phrases with possessives first rises and then goes down between 1650 and 1850. Another example is the failed do-support in positive declarative contexts in English. This construction grows in frequency from around 1500 to 1560 and rapidly declines afterwards (Postma 2010). The distribution of to-marking with the recipient argument in English ditransitive constructions has likewise been analyzed as a failed change by Bacovcin (2017). Truswell et al. (2019) describe the pattern characterizing the use of the ne … not construction from Early Middle English until the fifteenth century as a failed change.

Postma (2010) proposes to use a bell-shaped or parabolic function of the type in (14) to model such failed changes.9

- (14)

If a parabolic function in (14) fits the data on the determiner (non)occurrence in the set of noun phrases with short possessives as good or better than a simple monotonically decreasing logistic function, we can conclude that the failed change assumption for the evolution of determiners with short possessives in the observable data window is as viable or more viable than the simple decline assumption.

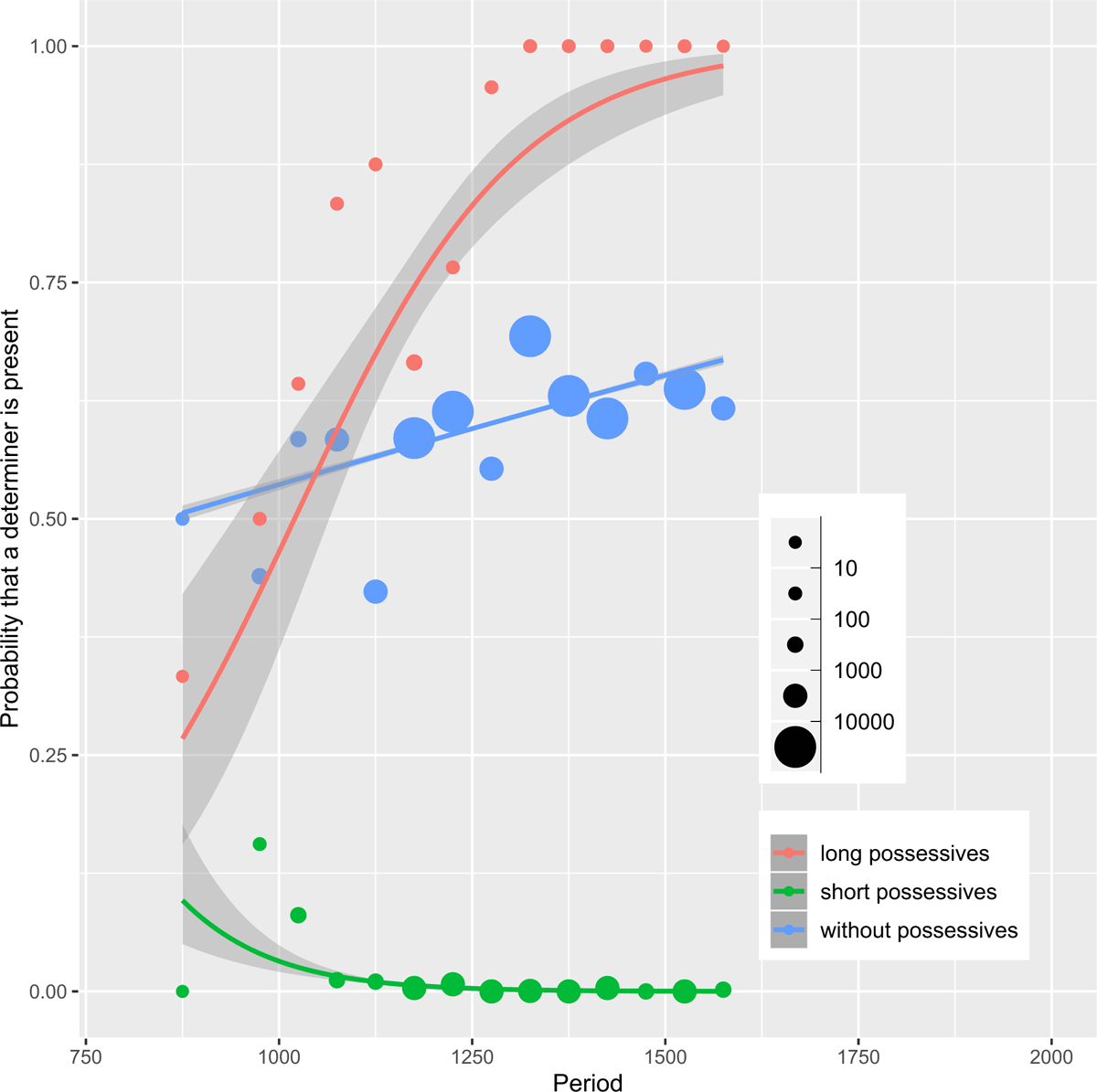

To evaluate a parabolic model, we fit it to the dataset consisting of noun phrases with prenominal short possessive forms. The result is illustrated in Figure 3, where green points correspond to 50 year bins (used for model fitting) and black ones – to determiner frequencies in individual texts, which are unevenly distributed across centuries.

The parameter estimates for the parabolic model are given in Table 4.

Parabolic model parameter estimates for French.

| Possessives | short |

| Intercept | 12.0000 |

| Std. Error | 2.4900 |

| z-value | 4.8193 |

| p-value | <0.001*** |

| Time coefficient | 5.0000 |

| Std. Error | 1.7686 |

| z-value | 2.8270 |

| p-value | <0.005** |

Sparsity of determiner occurrences in noun phrases with short possessives in general and before 1000 in particular makes it difficult to compare the simple logistic vs. parabolic models. The two earliest texts, which do not contain any determiners in noun phrases with short possessives, are very short. The first one, Sermons de Strasbourg (composition date 842 A.D.), consists of 115 words and contains 2 noun phrases with short possessives, as in (15), and 4 with long, of which 1 with a determiner, (16)–(17) (second noun phrase) and 3 without, (17) (first noun phrase).

- (15)

- medieval French

- si

- so

- cum

- how

- om

- one

- per

- by

- dreit

- law

- son

- his.short

- fradra

- brother

- salvar

- save

- dift

- should

- “as one should protect one’s brother” 0842-STRASB-BFM-P,.2

- (16)

- medieval French

- si

- so

- salvarai

- save.will

- eo,

- I

- cist

- that

- meon

- my.long

- fradre

- brother

- Karlo

- Charles

- “I shall protect my brother Charles” 0842-STRASB-BFM-P,.2

- (17)

- medieval French

- qui

- which

- meon

- my.long

- vol

- will

- cist

- that

- meon

- my.long

- fradre

- brother

- Karle

- Charles

- in

- in

- damno

- loss

- sit

- be

- “which, by my will, would be to the loss for my brother Charles” ID 0842-STRASB-BFM-P,.3

The second earliest text, Séquence de sainte Eulalie (composition date 881), counts 189 words and has only 1 noun phrase with a short possessive and without other determiners, (18). It also has 2 noun phrases with long possessives, one with, (19), and one without a determiner, (20).

- (18)

- medieval French

- Qu’

- than

- elle

- she

- perdesse

- loses

- sa

- her.short

- virginitet

- virginity

- “than losing her virginity” 0900-EULALI-BFM-P,.13

- (19)

- medieval French

- Ell’

- she

- ent

- of.there

- adunet

- gathers.up

- lo

- def

- suon

- her.long

- element

- force

- “She gathers up her strength” 0900-EULALI-BFM-P,.12

- (20)

- medieval French

- et

- and

- a

- to

- lui

- Him

- nos

- us

- laist

- lets

- venir

- come

- par

- by

- souue

- his.long

- clementia

- mercy

- “and allows us to come to Him by His mercy’ 0900-EULALI-BFM-P,.26

Although absolute numbers of noun phrases with either short or long possessives in these earliest texts are very low, we nevertheless do see determiners with the long, but not with the short paradigms.

We now proceed to the evaluation of both models in terms of classificatory accuracy. In particular, we compare the predictive performance of simple logistic and parabolic models using their receiver operating characteristics (ROC), which correspond to the relation between model’s sensitivity (proportion of true positive cases predicted to be positive among all true positive cases) and specificity (proportion of true negative cases predicted to be negative among all true negative cases) across multiple possible cut-off points, that is, different arbitrary thresholds for predicted probabilities below which a case is classified as negative and above which it is classified as positive. To compare models’ ROCs, we use the area under the curve measure (AUC). A greater AUC indicates a greater predictive accuracy of a model across multiple cut-offs. ROC (AUC) is 0.7115 for the logistic model corresponding to the steady decrease assumption within the observable window, and 0.7116 for the parabolic model, which assumes a rise-and-fall pattern within the attested data window. The models’ performance proves to be essentially identical and in both cases quite good. The search for a better model will not be pursued further here.10 However, this result allows us to conclude that a parabolic or rise-and-fall model is at least as good at capturing the distribution of determiners with short possessives as a steady decline model. We would like to stress that the rise-and-fall evolution hypothesis is the only one which is able to reconstruct the gap between Late Latin and Old French, and the question we have just explored is whether this pattern manifests itself in the observed data window. We conclude that it is plausible that it does, namely, that the available Old French sources offer evidence of a failed change in the context of short possessive noun phrases.

In Postma’s perspective, a change can be “doomed” to fail from the outset: the frequency of certain forms rises only to go down in the next generation because of an inherent suboptimality of the configuration resulting from the change. On this view, which we adopt, short possessive forms intrinsically have a property (or properties) making their co-occurrence with overt determiners suboptimal. We argue that this property is their determiner-like semantics, which enables them to spell out D (details are given in section 5).

3 Spanish

It will be shown below that in Spanish, just like in French, determiner frequency grows with long possessives, as well as in noun phrases without possessives. Unlike in French, long forms do not disappear from the language completely but rather stop occurring in the prenominal position. With regard to the co-occurrence of short possessives with determiners, again, just like in French, we show that it is plausible to assume an “up and down” pattern rather than a steady decrease. Once again, the two paradigms evolve very differently with respect to the presence of determiners.

3.1 Two possessive paradigms

Medieval Spanish features two paradigms of possessives, short and long forms, both of which can occur in the prenominal position. Sub-paradigms of both types for the first person are given in Tables 5, 6.

Spanish short prenominal possessive forms.

| singular | plural |

| mi | mis |

Spanish long prenominal possessive forms.

| singular | plural | |

| masculine | mío | míos |

| feminine | mía | mías |

Similarly to French (cf. Figure 1), long forms disappear from the prenominal position, as illustrated in Figure 4. Our dataset consists of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person short and long prenominal possessives (N = 1,275,626 noun phrases, of which 3657 have long possessives) taken from Davies (2006-).

3.2 Co-occurrence with determiners

In medieval Spanish, both short, (21)–(22), and long, (23)–(24), series can be used with and without determiners in the prenominal position (Labrousse 2018: 38).

- (21)

- Medieval Spanish

- cuanto

- how.much

- los

- def

- sus

- their.short

- scriptores

- scribes

- lo[s]

- them

- quisieron

- wanted

- crescer

- magnify

- y

- and

- ensalçar

- praise

- “How much their scribes wanted to magnify and to praise him.” Amadís, 1490, from Labrousse 2018: 2296

- (22)

- Medieval Spanish

- por

- for

- ser

- being

- a

- to

- él

- him

- según

- according

- su

- his.short

- flaqueza

- weakness

- más

- more

- conformes

- compliant

- ”for being more compliant to him according to his weakness” Amadís, 1490, from Labrousse 2018: 2303

- (23)

- Medieval Spanish

- fuestes

- you.were

- mio

- my

- vasallo

- vassal

- e

- and

- heredado

- inherited

- en

- to

- el

- def

- mio

- my.long

- regno

- reign

- “You were my vassal and inherited my reign” Livro del cavallero Cifar, 1300, from Davies 2006.

- (24)

- Medieval Spanish

- mande

- send.imp

- seellar

- seal

- esta

- this

- carta

- letter

- con

- with

- mio

- my.long

- seello

- seal

- de

- of

- plomo.

- lead

- “have this letter sealed with my lead seal” Documentos castellanos de Alfonso X, 1221, from Davies 2006-

In Modern Spanish, short forms cannot co-occur with determiners, while long forms, restricted to the postnominal position, can, as illustrated in (25)–(26).11

- (25)

- Modern Spanish

- (*la)

- the

- su

- his/her

- casa

- house

- “his/her/their house”

- (26)

- Modern Spanish

- la

- the

- casa

- house

- suya

- her

- “his/her/their house”

Below it is shown that, just like in medieval French, the frequency of determiners increases in medieval Spanish with long forms (until the long forms disappear from the prenominal position), as well as in noun phrases without prenominal possessives, and decreases with short forms. Again, as in medieval French, we show that it is very plausible that the frequency of determiners in the latter case follows an “up-and-down” pattern and thus constitutes a case of failed change.

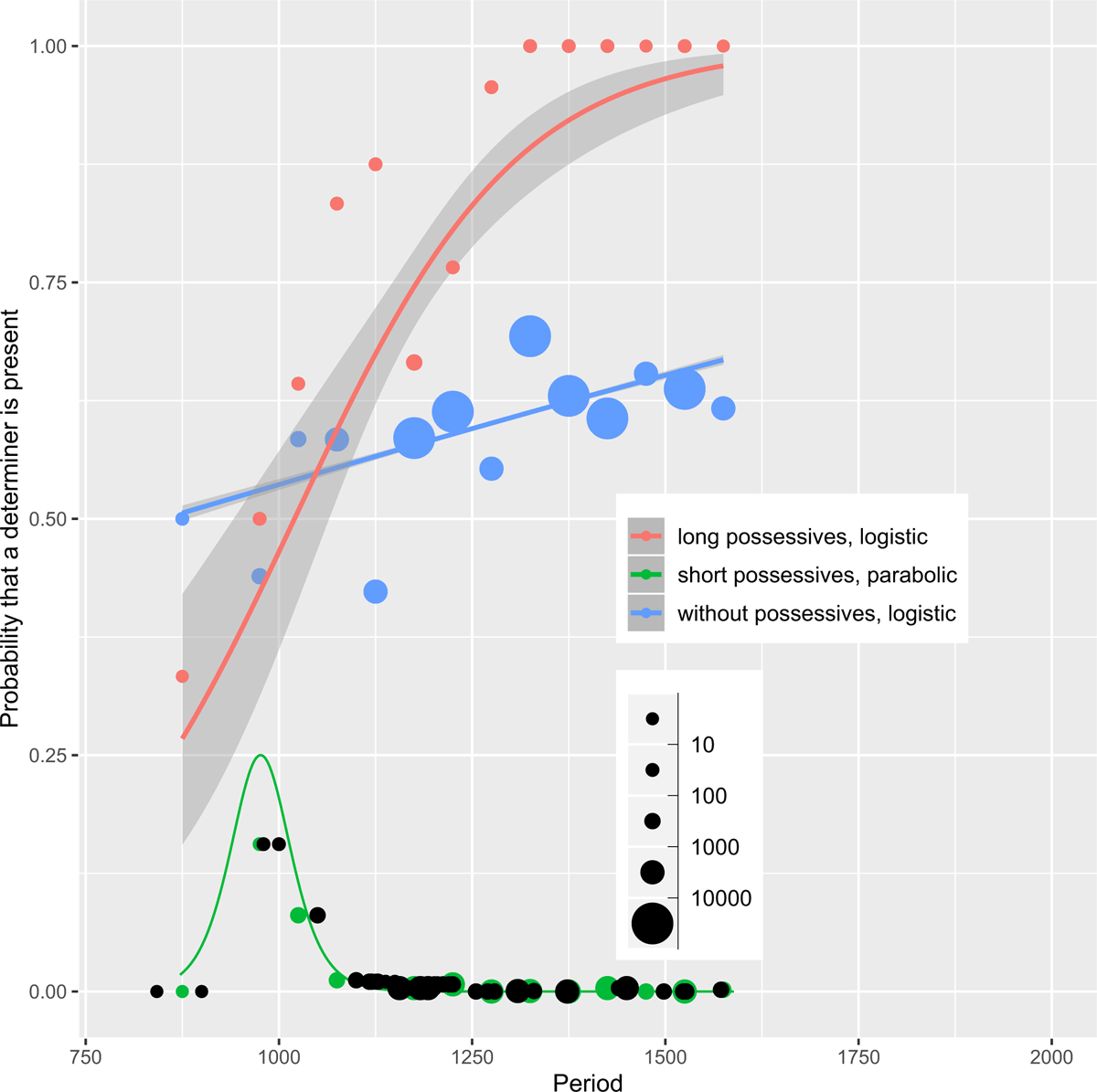

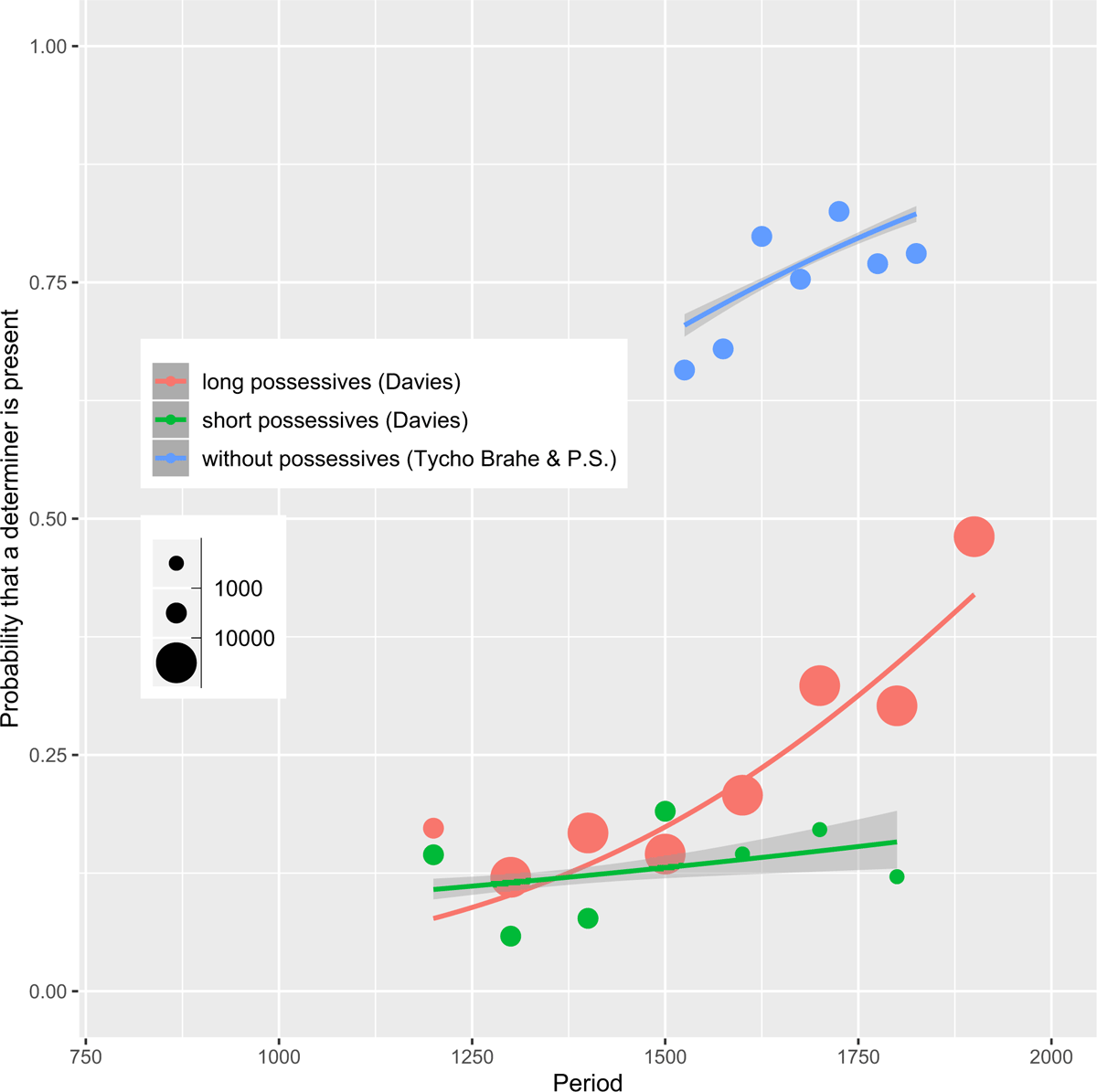

In order to evaluate the plausibility of the monotonic decrease vs. failed change assumptions for the short possessives, we first fit logistic regression models of the form in (13) to three data sets: noun phrases with (mostly) short possessives (N = 7703 noun phrases from Labrousse 2018: 79), noun phrases with prenominal long forms from Davies (2006-) (N = 3657 noun phrases), and noun phrases without possessives from P.S. Post Scriptum (2014) corpus (N = 6121 noun phrases).12 These models are graphed in Figure 5, and the parameter estimates are given in Table 7.

Logistic model parameter estimates for Spanish.

| Possessives | no | long | short |

| Intercept | –2.3537 | –2.4455 | 9.5303 |

| Std. Error | 0.4437 | 0.2582 | 0.5866 |

| z-value | –5.304 | –9.473 | 16.25 |

| p-value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | <0.001*** |

| Time coefficient | 0.0014 | 0.001 | –0.0084 |

| Std. Error | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 |

| z-value | 5.425 | 5.257 | –19.26 |

| p-value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | <0.001*** |

The models detect a negative trend with short forms (time coefficient = –0.0084, p < 0.001***), a positive trend with long ones (time coefficient = 0.001, p < 0.001***), and a positive trend in noun phrases without possessives (time coefficient = 0.0014, p < 0.001***).13

3.3 A failed change

We further evaluate the assumption that in Spanish noun phrases with short possessives, an up-and-down pattern is observable in the available data window. As in the case of French, the hypothesis of an initial rise of determiner frequency, before its decline, is the only one which is able to reconstruct the gap between Late Latin and Old Spanish. To see how plausible this assumption is, we fit a bell-shaped model of the type in (14) to this dataset. The latter replaces the logistic model in Figure 6. Data points for individual texts (in black) have been added here, in addition to 50 year bins (in green). Parameter estimates of the parabolic model are given in Table 8.

We compare the predictive accuracy of the two models, s- and bell-shaped, using ROC (AUC) characteristics. For the s-shaped or logistic model ROC (AUC) equals 0.70 and for the bell-shaped model – 0.76, which indicates a somewhat better performance of the latter. Hence, the assumption about the evolution of determiners with short possessives following an up-and-down trajectory within the observable data window is no less (or slightly more) plausible than the monotonic decrease assumption.

Parabolic model parameter estimates for Spanish.

| Possessives | short |

| Intercept | 1.5864 |

| Std. Error | 0.0600 |

| z-value | 26.424 |

| p-value | <0.001*** |

| Time coefficient | 2.4924 |

| Std. Error | 0.0691 |

| z-value | 36.038 |

| p-value | <0.001*** |

4 European Portuguese

4.1 Two possessive paradigms

Short and long prenominal possessive paradigms from medieval Portuguese are illustrated in Tables 9, 10 for the first person.14

Portuguese short prenominal possessive forms.

| singular | plural | |

| masculine | mo | not attested |

| feminine | m(h)a | mhas |

Portuguese long prenominal possessive forms.

| singular | plural | |

| masculine | meu | meus |

| feminine | mi(nh)a | mi(nh)as |

In contrast to French (and Spanish prenominal position), it is the short forms that do not survive. We track the distribution of the two types in the prenominal position (N = 324,599 noun phrases) using the corpus of Davies (2002-). The results are visualized in Figure 7.

4.2 Co-occurrence with determiners

In historical texts, both long and short forms are attested with and without determiners in the prenominal position. Examples (27)–(28) and (29)–(30) offer illustrations for long and short forms, respectively.

- (27)

- Early Modern Portuguese

- e

- and

- assim

- like.this

- fiquei

- stayed

- sem

- without

- poder

- be.able

- negar

- deny

- a

- the

- minha

- my.long

- vaidade.

- vanity

- “and so I was unable to deny my vanity” Reflexões, 1705, A_001_PSD,07.53

- (28)

- Early Modern Portuguese

- Assim

- like.this

- que

- as

- meu

- my.long

- pai

- father

- morrer

- dies

- “As soon as my father dies.’’” Maria Moisés, 1826, B_005_PSD,16.405

- (29)

- Medieval Portuguese

- Pois

- for

- como

- how

- dizedes

- you.say

- vos

- you

- aa

- to.def

- mha

- my.short

- alma

- soul

- “For how you say to my soul…” Livro das Aves, 1184, from Davies (2002-)

- (30)

- Medieval Portuguese

- Flérida

- Flérida

- Aquel

- Aquel

- tal

- that

- que

- which

- lamenta

- regrets

- su

- his.short

- ventura

- fate

- y

- and

- exclama

- exclaim

- su

- his.short

- tristeza

- sadness

- “Flérida Aquel, the one who regrets his fate and exclaims his sadness” Gil Vicente, Obra completa, 1465, from Davies (2002)

In Modern European Portuguese, in the prenominal position, long (and only long, short forms having disappeared) possessives normally co-occur with definite determiner, whereas in the postnominal position they are used with indefinite determiners, numerals, wh-words, as well as without determiners (cf. Brito (2007: 31), among many others).15

- (31)

- Modern European Portuguese

- o

- the

- meu

- my

- livro

- book

- ‘my book’

- (32)

- Modern European Portuguese

- um

- a

- livro

- book

- meu

- my

- ‘a book of mine’

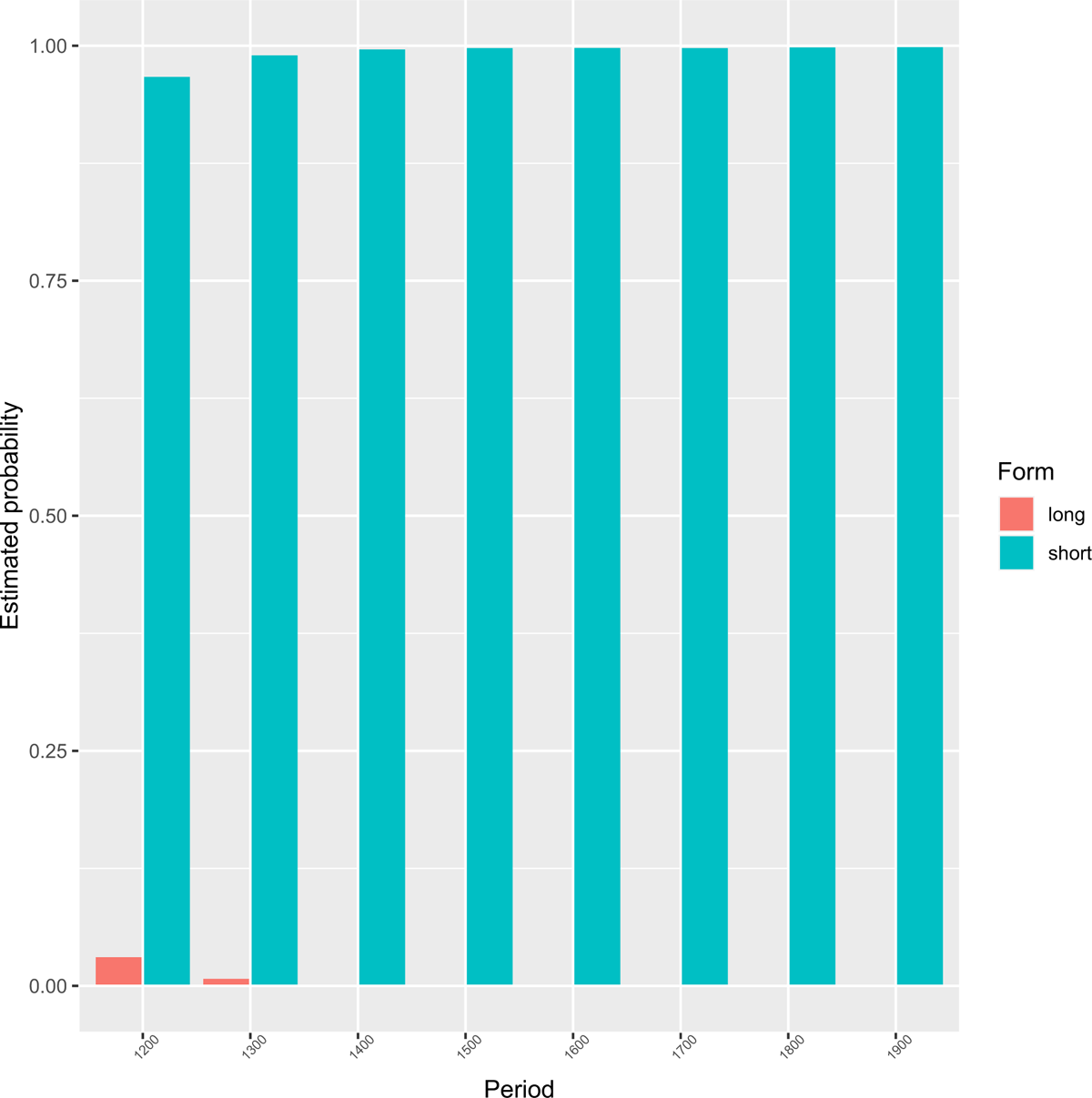

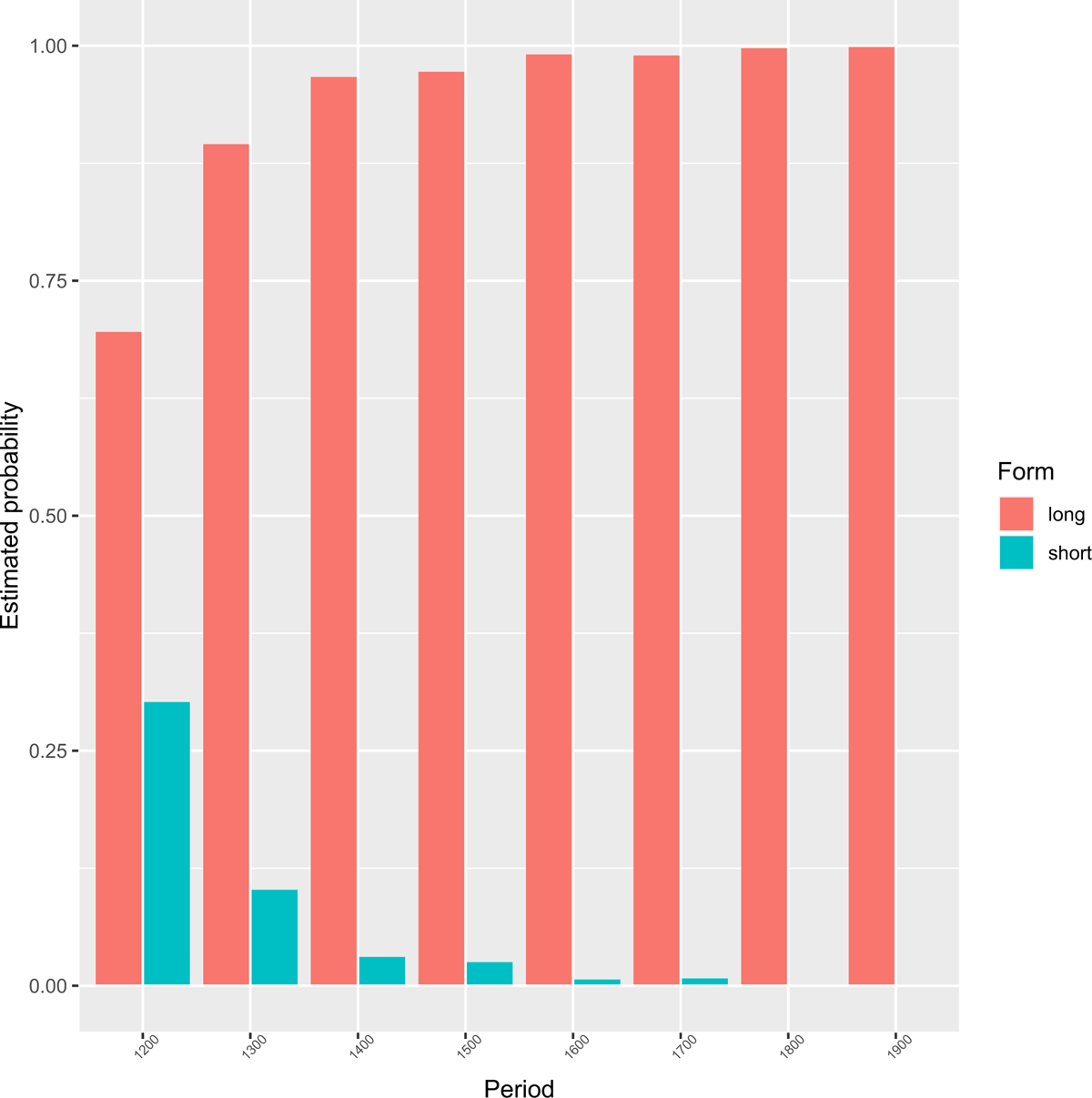

In order to evaluate the overall trends (increase or decrease) in the frequency of determiners and, in particular, the monotonicity assumption in the case of short possessives, we once again fit logistic regression models of the type in (13) to the datasets consisting of noun phrases with long prenominal possessives (N = 318,550 noun phrases, from Davies (2002-)), with short prenominal possessives (N = 6,409, from Davies (2002-)), and without possessives (N = 27,705 noun phrases, from Galves et al. (2017) and P.S. Post Scriptum (2014)). We visualize this in Figure 8.

As can be seen from Table 11, a logistic model detects a positive trend both in all three contexts, time coefficient being 0.5965 (p < 0.001***) with long possessives, 0.1881 (p < 0.001***) in noun phrases without prenominal possessives, and 0.1107 with short possessives (p = 0.0037**). In the latter case, the model’s estimates are the least reliable, especially after 1600. As Figure 7 indicates, around this time short possessives become vanishingly rare in the language.

Logistic model parameter estimates for Portuguese.

| Possessives | no | long | short |

| Intercept | 1.2199 | –0.9472 | –2.0017 |

| Std. Error | 0.0144 | 0.0042 | 0.0398 |

| z-value | 84.70 | –227.0 | –50.3 |

| p-value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | <0.001*** |

| Time coefficient | 0.1881 | 0.5965 | 0.1107 |

| Std. Error | 0.0143 | 0.0047 | 0.0382 |

| z-value | 13.13 | 127.1 | 2.9 |

| p-value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | 0.0037** |

The use of determiners with short possessives, however, seems to substantially differ from their distribution in noun phases with long possessives. We fit a bell-shaped model in (14) to the determiner distribution with short possessives in order to evaluate the plausibility of an up-and-down change trajectory in the context of short possessives. The result is plotted in Figure 9 and the parameter estimates of the parabolic model are given in Table 12.

Parabolic model parameter estimates for Portuguese.

| Possessives | short |

| Intercept | –0.2000 |

| Std. Error | 0.0954 |

| z-value | –2.0956 |

| p-value | <0.0361* |

| Time coefficient | 2.0000 |

| Std. Error | 0.0655 |

| z-value | 30.5563 |

| p-value | <0.001*** |

Comparing the two models, logistic and parabolic, in terms of their predictive ability as measured by ROC (AUC), is not very informative in this case: both perform very poorly, at around the chance level, with ROC (AUC) being 0.52 for the former and 0.41 for the latter. While evaluating the two models for the context of short possessives in Portuguese, we need to keep in mind that unlike the data on short possessives in French and Spanish, this dataset comes from a corpus without syntactic annotation and contains a degree of noise. The exploration of the determiner use trends in noun phrases with short possessives in Portuguese remains somewhat inconclusive, except for the important quantitative fact that their distribution in this environment clearly differs from the trend observed in the context of long possessives.

4.3 A comparison between French, Spanish, and Portuguese

For the ease of comparison of the evolution of determiner distribution in possessive and non-possessive noun phrases in the three Romance languages under consideration, we present the corresponding plots side by side in Figure 10.

These Figures for the three Romance languages under study visualise several important and previously unreported empirical results.

First, the determiner frequency grows during at least a certain period in all environments we have considered, that is, with short and long possessives, as well as in noun phases without possessives. In case of long possessives and noun phrases without possessives, the monotonic growth period correspond to the whole observed period. For the short possessives, we showed that it is likely that there is an initial growth period followed by the period of decline (except for the inconclusive results on Portuguese, where neither monotonic nor a bell-shaped models perform very well).

Second, the development in the context of long possessives seems to be largely in line, in terms of the general temporal trends rather than absolute rates, with the evolution of determiners frequencies in noun phrases without possessives. Moreover, in Spanish and Portuguese the two seem to follow a roughly parallel course (red and blue lines in the figures above).16

The third important result is that there is a strong difference in the trends observed in the environment of long prenominal possessives vs. short ones. While in the former environment the frequency of determiners clearly grows with time, in the latter it either declines or follows the up-and-down pattern (French and Spanish). Again, the quality of the Portuguese data on short possessives prevents us from deciding between a logistic model predicting a very slow growth or a model corresponding to a bell-shaped pattern. In either case, in Portuguese as well, the difference between the two environments is indisputable.

The fourth relevant observation that emerges from language comparison is that changes in determiner frequency in the context of long forms precede changes in the context of short possessives.

The analysis that we develop in the following section builds on these new empirical findings, as well as on the general theoretical consideration we mentioned before, namely, that it is necessary to admit that the frequency of determiners in the context of short possessives must have increased before it began decreasing in order to account for the transition between Late Latin and early Romance languages, whether we can capture this quantitative trend on the basis of the available empirical data or not.

5 Analysis: The rise of DP

5.1 Grammatical shift

In order to account for the fact that across the three examined languages, the growth of determiner frequency is observed both in noun phrases without prenominal possessives and with long possessives, as well as, initially, with short possessives (as established on theoretical and partially empirical grounds), rather than postulating changes at the level of individual possessive forms, we propose, following Simonenko & Carlier (2020a), that there is a general rise in frequency of the grammar where (in)definiteness is obligatorily marked at the noun phrase level. In other words, a single shift happens: a replacement of a grammar parsing nominals with their modifiers as an NP structure, as in (33a), by a grammar which parses them as a DP, as in (33b).17

- (33)

- a.

- [NP N] old nominal grammar

- b.

- [DP D [NP N]] new nominal grammar

Our analysis of this shift is couched in the perspective of grammar competition which assumes that in a given population of speakers more than one syntactic or semantic analysis of an utterance can be available (e.g., Kroch (1989) as one of the foundational works and Pintzuk (2003) for an overview). If with time the probability of using one of the grammars grows and that of using the “competing” grammar correspondingly declines, we can speak of a language change. The grammar competition approach has already been engaged for explaining the diachronic rise in frequencies in the determiner use in historical Spanish (Batllori & Roca 2000) and French (Simonenko & Carlier 2020a). We assume that the increasingly frequent parsing of nominals as structures with a determiner layer is a consequence of an emerging pressure to morphologically mark existential presupposition or its absence at the noun phrase level because marking it at the sentential level by means of constituent order and/or prosodic means becomes progressively unavailable, as suggested by Simonenko & Carlier (2020b) for French, among others. We adopt the latter point about causality as a conjecture without trying to develop and prove it further here.

In the following section, we present our account of the semantic and syntactic composition of long and short possessives that is compatible with the quantitative empirical results we have obtained.

5.2 Semantics of long and short forms

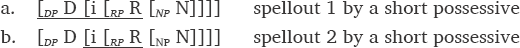

On the basis of our quantitative results, we endorse the widely advocated view that short and long forms have different semantico-syntactic properties, without subscribing to the claim that either paradigm underwent a semantic evolution. We propose, in particular, that they differ minimally in the presence of the DP layer in their internal structures. This difference, we argue, holds across all time periods and is independent of the NP-to-DP grammar shift operating in the diachrony of the three languages. Nominal expressions with long and short forms correspond to the structures in (34) and (35), respectively, where the parts in bold correspond to the internal structure of a possessive morpheme.

- (34)

- [[i [RP R [NP N]]]]

- nominal expression with a long possessive

- (35)

- [DP D [i [RP R [NP N]]]]

- nominal expression with a short possessive

Here R is a relational operator that introduces a possessive pronoun with index i in its specifier (cf. R in the semantics of demonstratives in Elbourne (2008) and in the semantics of possessives in Simonenko (to appear)). The semantics of R is given in (36), where P argument at the Logical Form level corresponds to the denotation of the nominal predicate and y to the denotation of the possessive index (a possessor individual). We also assume that R introduces a presupposition that there exist individuals with the nominal property P in the relevant situation of evaluation (for the discussion see Simonenko (2014)). R relates individuals with the property denoted by the nominal to a contextually given possessor by a possessive relation, broadly conceived.18

- (36)

- ⟦R⟧ = λP<e,<s,t>> . λye . λxe . λsσ : ∃x[P(x)(s)] . P(x)(s) & x is possessed by y in s

For D, we assume a Fregean semantics from Heim (2011) in its situational implementation, as in Schwarz (2009), whereby D denotes a function which takes a situation s, a property P, and returns a Sharvy’s maximal individual that has P in s, provided that there exists such individual in the relevant situation, as in (37).

- (37)

- ⟦D⟧ = λsσ. λP<e,σt> : ∃!x[Max(P)(x)(s)] . ιx[Max(P)(x)(s)],

- where Max(P) = λxe. λsσ . P(x)(s) & ¬∃y[P(y)(s) & x < y]19

There is non-quantitative evidence from Modern Portuguese, which retained long possessives in the prenominal position, that prenominal long possessives spell out a functional head rather than an adjectival phrase. Brito (2007) shows that in European Portuguese, prenominal possessives cannot be modified by “exclusion” adverbs (só, apenas “only, just”), (38), in contrast to postnominal possessives, (39).

- (38)

- Modern Portuguese

- *O

- def

- só

- only

- meu

- my

- problema

- problem

- é

- is

- que

- that

- não

- not

- percebo

- understand

- nada

- nothing

- disto.

- of.this

- Intended: “My only problem is that I don’t understand it.” Brito (2007: 32)

- (39)

- Modern Portuguese

- Um

- indf

- problema

- problem

- só

- only

- meu

- my

- é

- is

- que

- that

- não

- not

- percebo

- understand

- nada

- nothing

- disto.

- of.this

- “My only problem is that I don’t understand it.” Brito (2007: 32)

Castro & Costa (2002) show that prenominal possessives in Portuguese cannot be coordinated. Coupling this fact with the assumption that heads cannot be coordinated (Kayne 1994), they propose these forms spell out heads, rather than phrases.20

Our proposal also captures the fact that in Modern Portuguese, in the prenominal position long possessives occur virtually exclusively with definite determiners. Since R introduces a presupposition that the extension of RP is not empty in the relevant situation, RP, if felicitous in a given context, satisfies the existential part of the presuppositional requirements of a definite determiner (the other part being the maximality requirement), as given in (37).21 On the basis of the empirical data extracted from the corpus of Davies (2002-), we argue that this situation extends onto the Medieval period as well: the use of prenominal possessives with indefinites (relative to the overall use with indefinite, definite, and demonstratives determiners) was already very marginal in the twelfth century, 0.013, and never became higher. Given the Maximize Presupposition! reasoning, our proposal explains why prenominal long possessives occur almost only with a definite D, rather than an indefinite D.

Given the representation for nominals with short possessives in (35), it can be expected that determiners are never used in this context, since there is already a D head present as part of the internal structure of short possessives. Empirically, however, we observe the co-occurrence pattern for some period of time, which, we argued, likely followed a bell-shaped trajectory. Assuming that a lexical item can spell out a subset of the features it is specified with, as in the nano-syntactic approach to lexicalization (see Starke (2018) for a recent exposition), we propose that the short possessives are compatible with either of the spellout options represented in (40). On the first option schematized in (40a), they spell out both the RP and the DP layers, whereas on the second only the RP layer.22

- (40)

We propose that the second spellout option, in (40b), is not competitive, in the long run, in comparison to alternatives that are more economical in terms of processing: short possessives without overt determiners or long possessives with overt determiners. The reason is that in order to generate a sequence ‘determiner + short possessives + noun’, some type of lookahead or post-insertion syntactic realignment is needed to make a short possessive morpheme match only R instead of D-R when D is lexicalized by another determiner. Alternative spellouts, which is to lexicalize both D and R by a single item (i.e., ‘short possessive + noun’) without adding a separate determiner (and thus avoid readjustment) or to lexicalize R by a morpheme which can lexicalize only R and therefore, again, does not require readjustment (‘determiner + long possessive + noun’), are simpler in terms of processing and therefore, we argue, preferred options. Nevertheless, the force of analogy with the constructions ‘determiner + noun’ and ‘determiner + long possessive + noun’ drives the use of ‘determiner + short possessive + noun’ for some time, before it starts decreasing again.

The analogy-based argument, in addition to conceptual considerations, rests on the aforementioned quantitative fact that the rise in determiner frequency begins earlier in the context of noun phrases with long possessives than with short ones in the languages we investigated, as Figure 10 shows. From a diachronic viewpoint, the tension between analogy and economy is eventually resolved in favour of the latter in all three languages, and the frequency of ‘determiner + short possessives + noun’ goes down.

6 Conclusions

This paper examined diachronic changes in the distribution of determiners in noun phrases with short and long prenominal possessives and in noun phrases without possessives in three Romance languages. Focusing on the co-occurrence between possessives and determiners, it was demonstrated, for the first time, that French, Spanish, and Portuguese have remarkably similar evolutionary paths: determiner frequency first starts growing in noun phrases without possessives, then in noun phrases with long possessives, and, finally, in noun phrases with short possessives. In the latter context, shortly after the onset, the frequency goes down and tends to zero. We showed that a parabolic model describing a process that follows a bell-shaped trajectory and suggested in Postma (2010) for failed changes, in general fits the data as good as a logistic model used for monotonic processes (in this case constant decrease).

This study provides the first-ever historico-comparative analysis of possessives in Romance languages using quantitative data from large databases and statistical modeling. One of its major original contributions is to have revealed clearly diverging diachronic evolution of the determiner use in the context of short vs. long possessives in Romance languages. More generally, with the exception of Postma (2010) treatment of Brazilian Portuguese possessives, we are not aware of statistical modelling applied to the evolution of possessive noun phrases in Romance languages. It is also the first study to provide statistical arguments for assuming that the evolution of the determiner use in the context of short possessives in French, Spanish, and Portuguese follows the so-called failed change pattern, rather than monotonically decreasing. Apart from statistical considerations, we argued that the failed change assumption is the only one that can account for the transition from Late Latin, lacking systematic definiteness marking, and the early Romance languages, showing high rates of definiteness marking at the noun phrase level.

In order to account for the fact that determiner frequency grew for some period in nominal expressions both with and without possessives, we argue that the noun phrase structure in Romance changes in a uniform way, shifting in the direction of using existential presupposition marking at the nominal, rather than clausal, level. In the context of this shift, nominal expressions without prenominal possessives, as well nominal expressions with longs possessives are increasingly parsed as DP, rather that (extended) NP. As to short possessives, which, in our view, contain a determiner head as part of their semantico-syntactic architecture, it is hypothesized that the force of analogy caused a temporal spike in their use with overt determiners.

One of the most intriguing outstanding questions concerns, of course, the different fates of short and long paradigms across Romance languages: long forms only subsist as pronouns in French, can no longer be used to spell out relational head R in the prenominal position in Spanish, and are still used in Portuguese both pre- and postnominally (while the short forms are lost in this language). We speculate that at least part of the explanation lies in a change related to prosody. In French, the disappearance of word-level stress is sometimes invoked as a possible trigger behind some syntactic changes such as the disappearance V2 order (see Rainsford (2011) for a discussion). An explanation along this lines can be conceived for the disappearance of long possessives from the prenominal position. Another decisive factor may be the general principle of economy and, in particular, the preference of Late Merge over movement (Van Gelderen 2004): this would explain why in French postnominal long possessives, whose derivation presumably involves an N-over-AP movement, are replaced by possessive PPs (à moi “of mine” etc.). We leave further investigation to the future.

Abbreviations

def = definite, indf = indefinite, dem = demonstrative, sbjv = subjunctive.

Notes

- In addition, Schoorlemmer (1998) proposes that in some languages without [+definite] features, the possessive form may nevertheless cliticize onto D, precluding insertion of a determiner and making such languages superficially similar to the languages with [+definite] specification (see Ihsane (2000) for a critical discussion). [^]

- Ihsane (2000) proposes that a determiner possessive can move either from AgrPoss to D or from Spec,AgrPoss to Spec,DP, depending on whether it is a (morpho-phonologically) weak or strong form, respectively. [^]

- In the literature the labels stressed/unstressed (tonique/atone in French) are sometimes used (e.g. Buridant (2019)). We opt for long/short to stay agnostic with respect to the prosodic properties of the forms in question. [^]

- Today, prenominal long forms are attested sporadically in an archaic or ironic style, e.g. cette mienne vie lit. “this mine life” (M. Proust, À la recherche du temps perdu, 1913). Their only synchronically active use is as pronouns, in noun-less phrases, as in j’ai pris ton livre et le mien (“I took you book and mine”). [^]

- In order to obtain the quantitative data, we extracted all prenominal possessive forms in the corpora of Martineau et al. (2010) and Kroch & Santorini (2021), classified them manually into types that abstract away from purely orthographic variation, and then classified the types into short and long forms. The exact procedure can be found in the supplied CorpusSearch (Randall 2010) query and R script. Our classification is based on grammatical descriptions such as Buridant (2019), and previous works on the topic, such as Butet (2018). For those forms that appeared in neither, because of a substantial orthographic variation, we made decisions based on their surface morpho-phonological shape, classifying mono-syllabic forms as short and disyllabic as long. [^]

- Cited from Alexiadou (2004). [^]

- We do not consider vocative noun phrases, as well as de-noun phrases in the scope of negation or a quantifier (e.g. Pierre n’a pas d’eau “Pierre doesn’t have any water”, Pierre a bu beaucoup d’eau “Pierre has drank a lot of water”). We also exclude noun phrases with quantifiers that are incompatible with a morphologically overt determiner. We are also dealing here only with possessives which occur with full nominal predicates, leaving aside possessive pronouns used in noun-less phases, which are morphologically long forms. [^]

- The plotted relative frequency corresponds to the proportion of noun phrases with a determiner (definite, indefinite or demonstrative) among all relevant noun phrases. Each point corresponds to the proportion plotted at the middle of a given 50 year span, for instance, for the span 1100–1150, we plot a dot at 1125 on the x-axis with y-value corresponding to the average frequency for the texts in this period. [^]

- This parabolic function happens to be the first derivative of a logistic regression (as in (13)) with the same parameters. This relation is important for Postma (2010), who argues that the slope parameter of the model describing a failed change is identical to the slope of the corresponding successful change. In our case this would mean that the successful change (that is, the rise of the determiner frequency with long possessives) and the failed one (the raise and fall of determiner frequency with short possessives) proceed with the same speed, which would correspond to the hypothesis that these developments are reflections (in different contexts) of the same general grammatical shift, assuming the Constant Rate Hypothesis of Kroch (1989). Here we content ourselves with evaluating how well a parabolic model, with parameters estimated independently of the “successful” logistics, captures the determiner occurrence with the short possessives. [^]

- In further work, it would be interesting to consider bell-shaped curves with asymmetrical slopes, which can be generated, in particular, by models involving a multiplication of logistic regressions with different coefficients, such as the ones discussed in Bacovcin (2017). [^]

- One vestige of the archaic system in Modern Spanish, restricted to a formal written register and unattested in spoken language, is the co-occurrence of short prenominal forms with demonstrative, as in en esta su casa “in this house of his” (Picallo i Soler & Rigau 1999: 977). Such co-occurrences are not attested in spoken Spanish. In addition, according to Picallo i Soler & Rigau (1999: 977), some Northern dialects, such as those of Léon and Austurias, allow for the co-occurrence of short forms with definite determiners, as in la mi casa “the house of mine”. [^]

- The rates of long forms in the dataset of Labrousse (2018: 88) are negligible, ranging from 0% to 0.6% except in the earliest text where it is 13%. We therefore consider the dataset to be representative of short forms. [^]

- No mention is made of data on noun phrases without possessives in Labrousse (2018), and P.S. Post Scriptum (2014) corpus spans a later period (Early Modern Spanish). We opted for P.S. Post Scriptum (2014) rather than for Davies (2006-) because the former corpus has a syntactic annotation layer which makes pattern retrieval extremely reliable, in contrast to the latter corpus. [^]

- Like in Old French, there is a lot of spelling variation. All the variants listed in Labrousse (2018: 40–41) have been retained, as well as the plural forms. [^]

- Exceptions are vocative phrases and predicative positions, where prenominal long possessives can occur without determiners. [^]

- Noteworthily, all changes take effect earlier in French than in Spanish, and in both earlier than in Portuguese. This temporal ordering, which will not be explored further in this study, is in line with claims made by Carlier et al. (2012) and Carlier & Lamiroy (2018). [^]

- We abstract away here, for the sake of clarity, from (the evolution of) a number of important functional layers, such as number and case projections. [^]

- We assume that “possessed by” in the semantics of R can stand for a wide range of relations and that the exact interpretation is determined by the context (see the discussion in Partee & Borschev (2003), among others). [^]

- The symbol “<” stands for a proper part relation. [^]

- According to Brito (2007: 34), coordination of prenominal possessives is marginally acceptable in Portuguese provided one of the coordinated members is focalised. It is preferred, however, to use postnominal possessives in cases of coordination. [^]

- Specifically, we assume that the existential presupposition of the definite determiner is satisfied by the combined workings of the existential presupposition introduced by R (that the nominal extension is not empty in a given situation) and a general principle militating against restricting an extension known to be not empty to an empty set. That is, the principle states that restricting the nominal denotation by the property of being related to a possessor, introduced by R, cannot result in an empty extension. We give this principle a working label “No extension annihilation!”. We speculate that this semantic mechanism is responsible for at least a share of cases known in morphosyntactic terms as definite feature percolation or definiteness spreading (e.g., in Modern Hebrew, Danon (2008)). Stated generally, the mechanism in question implies that if one part of a complex nominal expression is presupposed to have a non-empty extension, the whole nominal expression is entailed to have a non-empty extension, which can manifest itself as multiple definiteness marking. [^]

- Since spellout targets constituents, we assume that R-to-D movement takes place prior to lexicalization. This assumption essentially matches Cardinaletti (1998) proposal that clitic possessives head-adjoin D. Miguel (2002) proposes that the short possessives in medieval Portuguese are D-adjoined clitics. [^]

Supplementary files

The datasets that we have used in our analysis are available at a repository: https://osf.io/92kqw/. DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/92KQW. The repository also contains an R file which calls on the datasets and contains all the relevant data manipulations, along with statistical analysis and visualisation functions.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Gertjan Postma, George Walkden, Beatrice Santorini, and Mallorie Labrousse for the discussions that helped us analyse the data.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2004. On the development of possessive determiners: Consequences for DP structure. In Fuß, E. & Trips, C. (eds.), Diachronic Clues to Synchronic Grammar 72. 31. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.72.03ale

Altmann, Gabriel & von Buttlar, Haro & Rott, Walter & Strauß, Udo. 1983. A law of change in language. In Brainerd, Barron (ed.), Historical linguistics [Quantitative Linguistics 18], 104–115. Bochum: Brockmeyer.

Arteaga, Deborah. 1995. On Old French genitive constructions. In Contemporary Research in Romance Linguistics: papers from the 22nd Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages, El Paso/Cd. Juárez, February 1992. 79–91. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.123.08art

Bacovcin, Hezekiah Akiva. 2017. Modelling interactions between morphosyntactic changes. In Mathieu, Eric & Truswell, Robert (eds.), From Micro-change to Macro-change 23. 94–103. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198747840.003.0007

Batllori, Montserrat & Roca, Francesc. 2000. The Value of Definite Determiners from Old Spanish to Modern Spanish. In Tsoulas, Gerog & Pintzuk, Susan & Warner, Andrew (eds.), Diachronic Syntax. Models and Mechanisms, 241–254. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brito, Ana Maria Barros de. 2007. European Portuguese possessives and the structure of DP. Cuadernos de lingüística del I. U. I. Ortega y Gasset 14. 27–50.

Buridant, Claude. 2019. Grammaire du français médiéval (GFM): XII–XIVe siècles. Strasbourg: ELIPHI, Éditions de linguistique et de philologie.

Butet, Lise-Marie. 2018. Étude empirique des possessifs dans les premiers textes du français dans le cadre d’une étude plus globale des possessifs du latin au français: Université de Lille MA thesis.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 1998. On the deficient/strong opposition in possessive systems. In Alexiadou, Artemis & Wilder, Chris (eds.), Possessors, Predicates and Movement in the Determiner Phrase 22. 17–53. Amsterdam: Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.22.03car

Carlier, Anne & De Mulder, Walter. 2010. The emergence of the definite article in Late Latin: ille in competition with ipse. In Cuykens, Hubert & Davidse, Kristin & Van de Lanotte, Lieven (eds.), Subjectification, Intersubjectification and Grammaticalization, 241–275. The Hague: Mouton De Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110226102.3.241

Carlier, Anne & Lamiroy, Béatrice. 2018. The emergence of the grammatical paradigm of nominal determiners in French and in Romance: Comparative and diachronic perspectives. Canadian Journal of Linguistics/Revue canadienne de linguistique 63(2). 141–166. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/cnj.2017.43

Carlier, Anne, Lamiroy, Béatrice & De Mulder, Walter. 2012. The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. Folia Linguistica 46. 287–301. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/flin.2012.010

Castro, Ana & Costa, João. 2002. Possessivos e advérbios: formas fracas como X˚. Actas do XVII Encontro Nacional da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística 101–111.

Danon, Gabi. 2008. Definiteness spreading in the Hebrew construct state. Lingua 118(7). 872–906. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2007.05.012

Davies, Mark. 2002-. Corpus do Português: 45 million words, 1300s–1900s (Historical/Genres). http://www.corpusdoportugues.org/hist-gen/.

Davies, Mark. 2006-. Corpus del Español: 100 million words, 1200s–1900s. (Historical/Genres). http://www.corpusdelespanol.org/hist-gen/.

Elbourne, Paul. 2008. Demonstratives as individual concepts. Linguistics and Philosophy 31(4). 409–466. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-008-9043-0

Galves, Charlotte & de Andrade, Aroldo Leal & Faria, Pablo. 2017. Tycho Brahe Parsed Corpus of Historical Portuguese. http://www.tycho.iel.unicamp.br/~tycho/corpus/texts/psd.zip. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/lv.00004.gal

Gamillscheg, Ernst. 1957. Historische Französische Syntax. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Heim, Irene. 2011. Definiteness and indefiniteness. In Maienborn, Claudia & von Heusinger, Klaus & Portner, Paul (eds.), Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning, Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

Ihsane, Tabea. 2000. Three types of possessive modifiers. Generative Grammar in Geneva 1. 21–54.

Ishikawa, Masataka. 1997. A note on reference and definite articles in Old Spanish. Word 48(1). 61–68. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1997.11432463

Kauhanen, Henri & Walkden, George. 2018. Deriving the Constant Rate Effect. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 36(2). 483–521. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9380-1

Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. The MIT Press.

Kroch, Anthony. 1989. Reflexes of grammar in patterns of language change. Language Variation and Change 1(3). 199–244. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394500000168

Kroch, Anthony & Santorini, Beatrice. 2021. Penn-BFM Parsed Corpus of Historical French (PPCHF). https://github.com/beatrice57/mcvf-plus-ppchf/.

Labrousse, Mallorie. 2018. Étude diachronique et comparée de l’alternance [article+possessif+ nom]-[possessif+ nom] en catalan, espagnol et portugais, du 13e au 20e siècle.: Paris 8 dissertation.

Lyons, John. 1985. A possessive parameter. Sheffield Working Papers in Language and Linguistics 2. 98–104.

Martineau, France & Hirschbühler, Paul & Kroch, Anthony & Morin, Yves Charles. 2010. Corpus MCVF annoté syntaxiquement, (2005–2010), dirigé par France Martineau, avec Paul Hirschbühler, Anthony Kroch et Yves Charles Morin.

Miguel, Matilde. 2002. Possessive pronouns in European Portuguese and Old French. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 1(2). 215–240. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.43

Niyogi, Partha & Berwick, Robert. 1997. A dynamical systems model for language change. Complex Systems 11(3). 161–204.

Oliveira e Silva, Giselle. 1982. Estudo da regularidade na variayao dos possessivos no Portugues do Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro dissertation.

Partee, Barbara H. & Borschev, Vladimir. 2003. Genitives, relational nouns, and argument-modifier ambiguity. In Cathrine Fabricius-Hansen Ewald Lang, Claudia Maienborn (ed.), Modifying adjuncts, vol. 4.

Picallo i Soler, M. Carme & Rigau, Gemma. 1999. El posesivo y las relaciones posesivas. In Bosque, Ignacio & Demonte, Violeta (eds.), Gramática descriptive de la lengua española 1. 973–1024. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

Pintzuk, Susan. 2003. Variationist approaches to syntactic change. In Joseph, Brian D. & Janda, Richard D. (eds.), The Handbook of Historical Linguistics, 509–528. Wiley Online Library. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756393.ch15

Postma, Gertjan. 2010. The impact of failed changes. In Breitbarth, Anne & Lucas, Christopher & Watts, Sheila & Willis, David (eds.), Continuity and Change in Grammar, 269–302. John Benjamins Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.159.13pos

P.S. Post Scriptum. 2014. P.S. Post Scriptum. Arquivo Digital de Escrita Quotidiana em Portugal e Espanha na Época Moderna. http://ps.clul.ul.pt.

Rainsford, Thomas Michael. 2011. The emergence of group stress in medieval French: University of Cambridge dissertation.

Randall, Beth. 2010. CorpusSearch. http://corpussearch.sourceforge.net/.

Schoorlemmer, Maaike. 1998. Possessors, articles, and definiteness. In Alexiadou, Artemis & Wilder, Chris (eds.), Possessors, Predicates and Movement in the Determiner Phrase (Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today 22), 55–86. Amsterdam: Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.22.04sch

Schwarz, Florian. 2009. Two Types of Definites in Natural Language: University of Massachusetts, Amherst dissertation.

Simonenko, Alexandra. 2014. Grammatical Ingredients of Definiteness: McGill University dissertation.

Simonenko, Alexandra. to appear. Full vs. clitic vs. bound determiners. Oxford Handbook of Determiners, ed. Martina Wiltschko and Solveiga Armoskaite. https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/004519.

Simonenko, Alexandra & Carlier, Anne. 2020a. Between demonstrative and definite: A grammar competition model of the evolution of french l-determiners. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 65(3). 393–437. https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/004947. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/cnj.2020.14

Simonenko, Alexandra & Carlier, Anne. 2020b. Givenness presupposition marking in a mixed system: Constituent order vs. determiners. In Gergel, Remus & Watkins, Jonathan F. (eds.), Quantification and Scales in Change, 203–233. Language Science Press.

Starke, Michal. 2018. Complex left branches, spellout, and prefixes. In Baunaz, Lena & Haegeman, Liliane & De Clercq, Karen & Lander, Eric (eds.), Exploring nanosyntax, 239–249. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190876746.003.0009

Truswell, Robert & Alcorn, Rhona & Donaldson, James & Wallenberg, Joel. 2019. A parsed linguistic atlas of early middle english. In Alcorn, Rhona & Kopaczyk, Joanna & Los, Bettelou & Molineaux, Benjamin (eds.), Historical Dialectology in the Digital Age, 19–38. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9781474430531.003.0002

Van Gelderen, Elly. 2004. Grammaticalization as economy, vol. 71. Amsterdam: Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.71

Van Peteghem, Marleen. 2012. Possessives and grammaticalization in Romance. Folia Linguistica 46. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/flin.2012.020