1. Introduction

This paper investigates the expression of conservative and non-conservative construals of relative measure constructions (RMCs) in Brazilian Portuguese (BrP), focusing on the use of bare singular count nouns (henceforth bare singulars) in these constructions. RMCs are structures that “express the proportional relation of one substance quantity to another quantity” (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 215), as in the company hired 55% of (the) women. In some languages, including English, the presence or absence of the definite determiner gives rise to different interpretations: when the definite determiner is used, the sentence is interpreted as referring to the “ratio of the company’s female hires to all women” (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 215), otherwise the sentence is interpreted as referring to the “ratio of the company’s female hires to all the company’s hires” (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 215). The former corresponds to the conservative interpretation and the latter to the non-conservative interpretation.

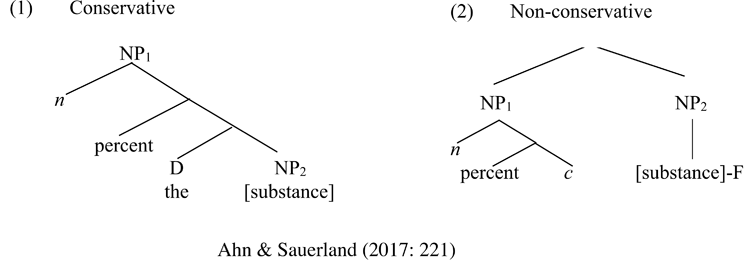

Ahn & Sauerland (2017: 221) argue that the conservative and non-conservative interpretations are associated with different syntactic construals. In conservative construals, a measure noun such as percent forms a constituent with the substance noun (1). In non-conservative construals (2), the measure noun forms a constituent with ‘a contextually determined variable C.’

Based on a preliminary study of nine languages, Ahn & Sauerland (2017) show that conversative and non-conservative construals tend to be associated with different grammatical structures. In languages such as German, Georgian and Greek, the case marking of the conservative construal (3) is different from the non-conservative construal (4):

- (3)

- German (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 219):

- 30 Prozent

- 30 percent-nom

- der

- the-gen

- Studierenden

- students-gen

- arbeiten.

- work

- ‘30 percent of students work.’ (conservative)

- (4)

- German (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 219):

- 30 Prozent

- 30 percent-nom

- Studierende

- students-nom

- arbeiten

- work

- hier.

- here

- ‘30 percent of workers here are students.’ (non-conservative)

Examples (3) and (4) illustrate the contrast between non-conservative and conservative construals in German. Ahn and Sauerland observe that a conservative reading is derived if the substance noun is marked as genitive (Studierenden ‘students’); a non-conservative interpretation is derived if the substance noun is marked as nominative (Studierende ‘students’).

Another predictor of the construction’s construal is word-order. In Korean, the substance noun is marked as genitive (5) when a relative measure construction is interpreted as conservative:

- (5)

- Korean (Ahn & Sauerland 2015: 134; 2017: 235)

- Hoysa-ka

- company-nom

- [yeca-(uy)

- woman-gen

- osip-phulo]-lul

- fifty-percent-acc

- ceyyonghayssta.

- hired

- ‘The company hired fifty percent of the women.’ (conservative)

- (6)

- Korean (Ahn & Sauerland 2015: 134; 2017: 235)

- Hoysa-ka

- company-nom

- yecaf-lul

- woman-acc

- osip-phulo

- fifty-percent

- ceyyonghayssta.

- hired

- ‘The company hired fifty percent women.’ (non-conservative)

Importantly, the measure noun may be separated from the substance noun as in (7), in which case only the non-conservative interpretation is available:

- (7)

- Korean (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 236)

- Hoysa-ka

- Company-nom

- yecaF-lul

- woman-acc

- (maynyen)

- every.year

- osip-phulo

- fifty-percent

- (maynyen)

- every.year

- ceyyonghayssta.

- hired.

- ‘The company hired fifty percent women every year.’ (non-conservative)

In (7), an adverb – maynyen ‘every year’– intervenes between the measure noun and the substance noun, therefore, providing further evidence that the substance noun and the measure noun do not form a constituent in non-conservative constructions (see structure 2).

A third predictor discussed by Ahn and Sauerland is focus. In Mandarin, the distinction between conservative and non-conservative readings is marked by focusing the substance noun in the non-conservative reading. In (8) a non-conservative interpretation is obtained by focusing běndì-rén ‘local person’:

- (8)

- Mandarin Chinese (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 242)

- Tāmen

- 3pl.

- lùyòng

- hire

- le

- perf

- 5%

- 5%

- de

- DE

- běndì-rén

- local-person

- a. ‘They hired 5% of the locals.’ (conservative)

- b. ‘5% of the persons they hired are locals.’ (non-conservative)

The fourth and last predictor of the different construals for conservative and non-conservative interpretations is definiteness, as illustrated in French (see 9 and 10) and Italian (see 11 and 12). Ahn and Sauerland observe that a conservative reading is available only when the argument of the measure noun is a definite phrase (9 and 11):

- (9)

- French (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 241)

- Ce

- This

- film

- movie

- a

- has

- été

- been

- vu

- seen

- par

- by

- deux

- two

- tiers

- thirds

- des

- of the

- journalistes.

- journalists

- ‘Two thirds of the journalists have seen this movie.’ (conservative)

- (10)

- French (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 241)

- Ce

- this

- film

- movie

- a

- has

- été

- been

- vu

- seen

- par

- by

- deux

- two

- tiers

- thirds

- de

- of

- journalistesF

- journalists

- ‘Two thirds of the people who have seen this movie are journalists.’ (non-conservative)

- (11)

- Italian (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 242)

- Gianni

- Gianni

- ha

- has

- parlato

- talked

- a

- to

- un

- a

- terzo

- third

- delle

- of the

- donne.

- women

- ‘Gianni talked to a third of the women.’ (conservative)

- (12)

- Italian (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 242)

- Gianni

- Gianni

- ha

- has

- parlato

- talked

- a

- to

- un

- a

- terzo

- third

- di

- of

- donne.

- women

- ‘A third of those Gianni talked to were women.’ (non-conservative)

Definiteness is also a predictor of conservativity in BrP. While (13) is compatible with a conservative interpretation, (14) is not (although see example (33) in section 3):

- (13)

- Brazilian Portuguese (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 242)

- O

- the

- filme

- movie

- foi

- was

- visto

- seen

- por

- by

- 1/3

- 1/3

- dos

- of.the

- jornalistas.

- journalists

- ‘The movie was seen by 1/3 of the journalists.’ (conservative)

- (14)

- Brazilian Portuguese (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 242)

- O

- the

- filme

- movie

- foi

- was

- visto

- seen

- por

- by

- 1/3

- 1/3

- de

- of

- jornalistas.

- journalists

- ‘One third of the people who saw the movie were journalists.’ (non-conservative)

An interesting feature of RMCs in BrP is that they allow the use of bare singular nominals as substance nouns, as illustrated in (15). The use of bare singulars in RMCs has not been reported in other languages in Ahn & Sauerland (2017)’s sample:

- (15)

- Brazilian Portuguese (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 242)

- O

- The

- filme

- movie

- foi

- was

- visto

- seen

- por

- by

- 1/3

- 1/3

- de

- of

- jornalista.

- journalist

- ‘One third of the people who saw the movie were journalists.’ (non-conservative)

Importantly, unlike in other Romance languages, the distribution of bare singulars is widespread in BrP (16a-b): they may occur in subject and object position, in episodic sentences with definite or indefinite readings, in generic sentences and, according to some authors, with kind-selecting predicates.

- (16)

- a.

- Brazilian Portuguese (Müller & Oliveira 2004: 15)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- leu

- read

- revista

- magazine

- ontem.

- yesterday

- ‘Mary read magazines yesterday.’ (episodic sentence)

- b.

- Brazilian Portuguese (Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011: 2158)

- Baleia

- whale

- está

- is

- em

- in

- extinção.

- extinction

- ‘Whales are/ the whale is on the verge of extinction.’ (kind predication)

This paper aims to provide a description of BrP bare singulars in RMCs, and to consider its implications both for theories of bare nominals and for theories of RMCs. We start with the observation that BrP bare singulars in RMCs give rise both to conservative and to non-conservative readings. If we adopt Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) theory of relative measures or its more recent re-implementation by Pasternak & Sauerland (2020), this means that bare singulars in conservative RMCs must be of type e, while bare singulars in non-conservative RMCs must be of type ⟨e,t⟩. We argue that this split is expected in the light of theories of bare nominals for which argumental bare singulars are DPs of type e, while predicate bare singulars are NPs of type ⟨e,t⟩ (Schmitt & Munn 1999; 2002; Munn & Schmitt 2002; 2005). Nevertheless, we identify an issue for the integration of Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) and Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analyses of RMCs with existing theories of predicative bare nominals. We show that in order to account for non-conservative readings of RMCs with bare singulars in BrP, one must assume that predicative bare singulars denote number neutral properties of objects, as argued by Munn & Schmitt (2005). The issue is that while this analysis accounts for the distribution of bare singulars in RMCs in BrP, it overgenerates in other Romance languages, as we will discuss in section 5: if Munn & Schmitt’s (2005) arguments are correct, then number neutral bare singulars are attested not only in BrP, but also in other Romance languages. This leads to the prediction that everything else being equal, bare singulars should be acceptable in RMCs with non-conservative readings in French and Spanish (and more generally across Romance languages), which appears to be incorrect. We conclude that while we might have a good grasp of the use of bare singulars in RMCs in BrP, more work needs to be done to understand the absence of predicative bare singulars in RMCs in other languages.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 gives an overview of the distribution and interpretation of bare singulars in BrP. Section 3 focuses on the use of bare singulars in RMCs. Section 4 discusses Ahn and Sauerland’s analysis of RMCs. The predictions of this analysis for the distribution of bare singulars in BrP and in Romance languages are explored in section 5.

2. Bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese

The literature on Brazilian Portuguese has shown that bare singulars can occur in a wide range of syntactic environments (Schmitt & Munn 1999; 2002; Munn & Schmitt 2002; Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011; Cyrino & Espinal 2015; Wall 2017, among many others), with different types of verbs, both in subject and object positions, in episodic and generic sentences, and for some authors, with kind-selecting predicates (see Müller 2002; Müller & Oliveira 2004 for a different judgment). In object position, bare singulars are attested with generic readings in characterizing sentences, as arguments of individual level predicates, and with existential readings in episodic sentences, as illustrated by examples (17), (18) and (19) respectively.

- (17)

- Gato

- cat

- come

- eat

- rato.

- mouse

- ‘Cats eat mice’ (Ferreira 2021: 501)

- (18)

- João

- João

- gosta

- likes

- de

- of

- cachorro.

- dog

- ‘João likes dogs’ (Ferreira 2021: 500)1

- (19)

- Ele

- he

- comprou

- bought

- computador.

- computer

- ‘He bought computers/a computer.’ (Schmitt & Munn 2002: 187)

In subject position, the interpretation of bare singular is more restricted. Bare singulars are acceptable as subjects in generic sentences, as illustrated in (20):

- (20)

- Cachorro

- dog

- late

- barks

- (quando

- (when

- está

- is

- bravo)

- angry)

- ‘Dogs bark (when they are angry).’ (Ferreira 2021: 500)

By contrast, bare singulars are generally ungrammatical as subjects of episodic predicates, except in contrastive environments like (21). For a discussion of this point, see Schmitt & Munn (1999), Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein (2011), Pires de Oliveira & Mariano (2011), Menuzzi et al. (2015).

- (21)

- Mulher

- woman

- discutiu

- discussed-perf

- as

- the

- eleições,

- elections

- homem

- man

- discutiu

- discussed-perf

- futebol…

- soccer

- ‘Women discussed politics, men discussed soccer, …’ (Schmitt & Munn 2002: 187)

Regarding kind-selecting predicates, the literature is divided. While some authors have argued that bare singulars are not compatible with kind-selecting predicates (Müller 2002, Müller & Oliveira 2004), others have argued that bare singulars can denote kinds (Schmitt & Munn 2002; Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011):

- (22)

- No

- in.the

- ano

- year

- 2030,

- 2030

- gavião-real

- hawk-royal

- vai

- will

- estar

- be

- extinto.

- extinct

- ‘In the year 2030, royal hawks will be extinct.’ (Schmitt & Munn 2002: 187)

Finally, Cyrino & Espinal (2015) and Wall (2017) show that bare singulars are also attested with definite interpretations, as illustrated in (23):

- (23)

- “Perdi

- lost

- a

- the

- minha

- my

- aliança!”

- ring

- gritou

- shouted

- Didi.

- Didi

- (…)

- E

- and

- nada

- nothing

- de

- of

- encontrar

- find

- aliança.

- ring

- ‘“I have lost my wedding ring!” cried Didi. (…) And it was impossible to find it.’ (Cyrino & Espinal 2015: 480)

On a theoretical level, the literature on bare singulars in BrP has focused on two questions (see Ferreira 2021 for a recent survey): what is the basic denotation of bare singulars (kinds or properties), and are they bare NPs or DPs with a null D? Here, we review the main lines of Schmitt & Munn’s (1999; 2002) and Munn & Schmitt’s (2002; 2005) influential analysis, which will form the basis of our study of bare singulars in RMCs.

At the heart of Schmitt and Munn’s analysis is the observation that bare singulars are number neutral, both when used as arguments and when used as predicates. This is illustrated in (24) for bare singular arguments and in (25) for bare singular predicates:

- (24)

- Eu

- I

- vi

- saw

- criança

- child

- na

- in.the

- sala.

- room

- E

- and

- {ela

- she

- estava

- was

- /

- elas

- they

- estavam}

- were

- ouvindo.

- listening.

- ‘I saw a child/children in the room. And she was/they were listening.’ (Munn & Schmitt 2005: 825)

- (25)

- Ninguém

- nobody

- poderá

- will.be.able

- usar-nos/usá-lo

- to.use-us/him

- como

- as

- testemunha.

- witness

- ‘Nobody will be able to use us/him as witnesses/as witness.’ (Munn & Schmitt 2002)

(24) shows that a bare singular argument (criança, ‘child’) can serve as the antecedent of either a singular or a plural pronoun in a subsequent sentence. (25) shows that a bare singular nominal (testemunha, ‘witness’) can predicated of either a plural (nos, ‘us’) or a singular (lo, ‘him’) argument. Based on such observations, Schmitt and Munn argue that bare singulars are number neutral in BrP. That is to say, the extension of a common noun like criança or testemunha is a set of individuals that include both atoms and pluralities. More precisely, Schmitt & Munn (1999; 2002) and Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) propose that count common nouns denote number neutral properties of individuals (objects rather than kinds in the terminology of Carlson 1977), and that it is the addition of a Num head to a count noun that filters out atoms or pluralities from its denotation and turns it into a semantically singular or plural nominal. The reason why BrP bare singulars are number neutral is that the NumP layer can be omitted in BrP, unlike in languages like English.

Of course, number neutrality is not sufficient to license the use of bare singulars as arguments, since a number neutral property-denoting nominal still has a predicative type (⟨e,t⟩ in extension), and therefore it cannot saturate or bind the argument position of another predicate. Following Chierchia (1998), Schmitt and Munn argue that property-denoting nominals that include pluralities in their extension can be turned into kind-denoting nominals, which allows them to function as arguments. Indeed, the extension of a kind is the maximal individual in the extension of the corresponding property (e.g., the extension of the kind DOG in a world is the plurality consisting of all dogs in that world). Since predicative bare singulars are number neutral in BrP, they can be mapped into names of kinds of type e by selecting the maximal individual in their extension. Unlike Chierchia (1998), Schmitt and Munn assume that this mapping is done by a null D (see Dobrovie-Sorin & Pires de Oliveira 2008 for an explicit discussion of the relation of this null D to Chierchia’s (1998) ‘∩’ function). Argumental bare singulars in BrP are therefore DPs with a null D head that lack a NumP projection, as shown in (26):

- (26)

- [DP D [AgrP Agr [NP N ] ] ]

This analysis predicts that BrP bare singulars will be able to function as arguments of kind selecting predicates. In order to account for existential readings of bare singulars in episodic sentences, as in example (20) above, Schmitt and Munn adopt Chierchia’s (1998) assumption that a mechanism of Derived Kind Predication can apply to kind-denoting nominals as a last resort, which introduces existential quantification over instances of the kind2:

- (27)

- Derived Kind Predication (Chierchia 1998: 364):

- If P applies to objects and k denotes a kind, then P(k) = ∃x[⋃k(x) ∧ P (x)]

While Schmitt & Munn (1999; 2002) and Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) do not discuss compositional details of the generic interpretation of bare singulars, this interpretation can be derived from kind-denoting uses of bare singulars using Chierchia’s (1998) kind to property function ‘⋃’, together with a generic operator GEN that quantifies over instances of the kind (see Chierchia 1998: 367; see also Ferreira 2021:507–512 for a discussion of generic interpretations of bare nominals in BrP):

- (28)

- Cachorro

- dog

- late.

- bark

- ‘Dogs bark.’

- GEN x, s [⋃∩dog(x) ∧ C(x, s)][bark(x, s)]

Finally, since definite interpretations of non-kind-denoting bare singulars will play a role in our analysis of RMCs, we will dedicate some space to their analysis. Since Schmitt & Munn (1999; 2002) and Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) do not discuss this interpretation, we will sketch Cyrino & Espinal’s (2015) analysis, and we will see how it can be recast in a way that is consistent with Schmitt and Munn’s assumptions about the structure and interpretation of bare nominals. Cyrino & Espinal (2015) argue that definite bare singulars are DPs with a null D head. Cyrino & Espinal also depart from Schmitt and Munn’s analysis insofar as they maintain that bare singulars include a Number projection. In their analysis, count nouns inserted in N denote number neutral properties of kinds, and a Number projection is required to map properties of kinds (type (⟨ek,t⟩) to properties of instances of kinds (type (⟨eo,t⟩). Singular number returns a property of atomic objects, and plural number returns a property of plural objects. A null definite determiner specified for number then maps such a property to the maximal individual in its extension. (29) represents the structure of BrP bare singulars in this analysis (cf. Cyrino & Espinal 2015: 484):

- (29)

- [DP D [NumP Num [NP N ] ] ]

It is possible to analyze definite readings of non-kind-denoting bare singulars in Schmitt and Munn’s analysis without departing from the assumptions that count nouns in BrP denote number neutral properties of individuals/objects (type (⟨eo,t⟩) rather than of kinds, and that bare singulars lack a Number projection. The only adjustment that is needed is to accept with Cyrino & Espinal (2015) that definite determiners may be either overt or covert in BrP, contra Chierchia’s (1998) hypothesis (known as the blocking principle) that overt determiners block semantically equivalent but phonologically covert type-shifting operations. One may wonder how singular definite descriptions can be generated by combining a definite determiner with a number neutral noun, since the definite determiner should pick out the maximal individual in the extension of the noun. The answer is that contextual domain restriction will reduce the extension of the property to a singleton set, and the definite determiner will pick out the only member in that set. In example (23), repeated here as (30), contextual domain restriction will shrink the extension of aliança to the singleton set that includes the unique ‘atomic’ wedding ring that is salient in the context of utterance. It is important to note that contextual domain restriction is also needed in Cyrino & Espinal’s (2015) analysis of this example, since otherwise the singular NumP aliança would denote the set of all wedding rings (excluding pluralities), and the DP would fail to refer because no supremum would be defined for the extension of NumP.

- (30)

- “Perdi

- lost

- a

- the

- minha

- my

- aliança!”

- ring

- gritou

- shouted

- Didi.

- Didi

- (…)

- E

- and

- nada

- nothing

- de

- of

- encontrar

- find

- aliança.

- ring

- ‘“I have lost my wedding ring!” cried Didi. (…) And it was impossible to find it.’ (Cyrino & Espinal 2015: 480)

In sum, while Schmitt & Munn (1999; 2002) and Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) do not discuss definite interpretations of non-kind-denoting bare singulars, their analysis can be extended to account for these interpretations, provided we accept that Chierchia’s (1998) blocking principle is inactive with bare singulars in BrP.

The literature on bare singulars in BrP has explored alternative analyses, which differ with respect to the presence or absence of a null D,3 the range of operators that can be spelled out by a null D head,4 the syntactic representation of number,5 and the denotation of the lexical nominal head.6 Nevertheless, one point of agreement in the literature is that bare singulars are number neutral (or, in Cyrino & Espinal’s 2015 analysis, ambiguous between singular and plural interpretations). In the following sections, we will see that number neutrality allows us to make sense of the use of bare singulars in RMCs in BrP, while at the same time raising questions about their absence in other languages in which predicative number neutral bare singulars are attested.

3. Brazilian Portuguese relative measure constructions

As in other Romance languages, in Brazilian Portuguese, the availability of conservative and non-conservative interpretations can be predicted by the presence of a definite article in the genitive complement of the relative measure. As illustrated by the contrast between examples (31) and (32), definiteness is associated with a conservative interpretation:

- (31)

- A

- the

- empresa

- company

- contratou

- hired

- 55

- 55

- porcento

- percent

- das

- of.the

- mulheres.

- women

- ‘The company hired 55 percent of the women.’ (conservative; elicited)

- (32)

- A

- the

- empresa

- company

- contratou

- hired

- 55

- 55

- porcento

- percent

- de

- of

- mulheres.

- women

- ‘55 percent of the people the company hired were women.’ (non-conservative; elicited)

Note that in (32), a kind-denoting interpretation of the bare plural noun phrase mulheres is unavailable. However, in sentences that license kind-denoting interpretations of bare plurals, RMCs can receive a conservative interpretation, as illustrated by example (33):7

- (33)

- Dez

- ten

- porcento

- percent

- de

- of

- Americanos

- Americans

- fumam

- smoke

- Marlboro.

- Marlboro

- ‘Ten percent of Americans smoke Marlboro.’ (conservative; elicited)

Examples like (33) are not counter-examples to the generalization that definiteness is a predictor of conservative interpretations since kind-denoting interpretations are a type of definite interpretation.

The contrast between conservative and non-conservative interpretations is only attested in object position. In subject position, only the conservative reading is available for definites (34) and (kind-denoting) bare plurals (35):

- (34)

- Um

- One

- terço

- third

- das

- of

- mulheres

- women

- e

- and

- meninas

- girls

- é

- is

- vítima

- victim

- de

- of

- violência.

- violence

- ‘One third of the women and girls is victim of violence’ (conservative; elicited)

- (35)

- Um

- One

- terço

- third

- de

- of

- mulheres

- women

- e

- and

- meninas

- girls

- é

- is

- vítima

- victim

- de

- of

- violência.

- violence

- ‘One third of women and girls is victim of violence’ (conservative: news article8)

The same subject-object asymmetry9 is attested in other languages where definiteness is a predictor of conservativity, except Italian (Ahn & Sauerland 2017: 243).10

Definiteness also affects the interpretation of RMCs with substance- (36 and 37) and object-denoting (38 and 39) mass nouns in Brazilian Portuguese. In constructions with such nouns, definiteness is associated with conservative interpretations of the relative measure:

- (36)

- Eles

- they

- beberam

- drank

- 30

- 30

- porcento

- percent

- da

- of.the

- cerveja.

- beer

- ‘They drank 30 percent of the beer.’ (conservative; elicited)

- (37)

- Eles

- they

- beberam

- drank

- 30

- 30

- porcento

- percent

- de

- of

- cerveja.

- beer

- ‘30 percent of what they drank was beer.’ (non-conservative; elicited)

- (38)

- A

- the

- loja

- store

- vendeu

- sold

- 30

- 30

- porcento

- percent

- da

- of.the

- prataria.

- silveware

- ‘The store sold 30 percent of the silverware.’ (conservative; elicited)

- (39)

- A

- the

- loja

- store

- vendeu

- sold

- 30

- 30

- porcento

- percent

- de

- of

- prataria.

- silverware

- ‘30 percent of what the store sold was silverware.’ (non-conservative; elicited)

The features of BrP RMCs that we have discussed up to this point do not set BrP apart from other number marking languages where definiteness is a predictor of conservative readings. A more surprising feature of BrP is the availability of bare singulars in RMCs. Interestingly, both conservative and non-conservative interpretations are attested with bare singulars. Let us begin with some examples of non-conservative readings. Consider for instance example (40):

- (40)

- Context: the Brazilian Senate was debating a rule that would require 30% of candidates put forward by political parties to be women. Twitter users were reacting to this debate:

- Tem que

- must

- colocar

- put

- 30%

- thirty percent

- de

- of

- mulheres,

- women

- certo?

- right

- O

- the

- partido

- part

- que

- that

- não

- neg

- coloca,

- put

- ele

- he

- vai

- will

- incorrer

- incur

- em

- in

- uma

- a

- ilicitude.

- illegality.

- Vários

- many

- candidatos

- candidates

- masculinos

- masculine

- foram

- were

- cortados,

- cut

- porque

- because

- tem que

- must

- ter

- have

- 30%

- thirty percent

- de

- of

- mulher,

- woman,

- disse

- said

- Bivar.

- Bivar

- ‘There must be 30% of women, right? The political party that does not include it will be doing something illegal. Several male candidates were cut because we must have 30% of women, said Bivar.’ (Twitter)

This example illustrates the use of bare plurals (30% de mulheres) alongside bare singulars (30% de mulher) in RMCs. In both cases the interpretation is non-conservative: the percentage (30%) is understood as the ratio of women candidates to all the candidates in a political party. Note that in this and all other examples with the symbol ‘%’, this symbol stands for the singular measure noun porcento (‘percent’). No additional morphological marking on this measure noun would be grammatical in any of the examples.

Another example from social media is given in (41). In this example, the percentage (40%) is understood as the ratio of electric cars owned by US consumers to all US owned cars:

- (41)

- Context: user A posted a link on the production of electric cars in the US by Tesla. User B asked whether electric cars are popular in the US. After B learns that the industry is relatively young, B and A have the following interaction:

- B

- Tipo

- like

- pelo

- about.the

- que

- that

- falam

- speak

- dele

- of.him

- e

- and

- da

- of.the

- empresa

- business

- eu

- I

- penso

- think

- que

- that

- nos

- in.the

- EUA

- USA

- tem

- have

- uns

- some

- 40%

- 40 percent

- de

- of

- carro

- car

- elétrico

- electric

- já

- already

- kk

- kk

- ‘Based on what they say about him [Elon Musk] and his business, I would think that the US already has 40% of electric cars kk’ (Twitter)

- A

- (…)

- Depois

- afterwards

- dá

- give

- uma

- a

- lida

- read

- na

- in.the

- biografia

- biography

- dele.

- of.him

- Mas

- but

- até

- until

- ter

- have

- 40%

- 40 percent

- de

- of

- carro

- car

- elétrico

- electric

- vai

- will

- levar

- take

- uns

- some

- anos

- years

- aí

- there

- de

- of

- muita

- many

- gente

- people

- fabricando

- producing

- carro

- car

- elétrico (…)

- electric

- ‘(…) When you can, read his biography. It will take a few years of many people fabricating electric cars [to have 40% of electric cars] (…)’ (Twitter)

It is important to note that such examples are not restricted to informal conversations on social media, but are also attested in more formal registers, such as example (42) from a news article:

- (42)

- MDB

- MDB

- se

- se

- compromete

- commit

- a

- to

- ter

- have

- 30%

- 30 percent

- de

- of

- mulher

- woman

- nos

- in.the

- cargos

- positions

- de

- of

- direção.

- management

- ‘MDB is committed to including 30% of women in management positions.’ (news article)11

The previous examples illustrated non-conservative uses of bare singulars in RMCs. Conservative interpretations are also attested, as illustrated in (43). In this example, the bare singular livro (‘book’) is interpreted as a singular definite description: it refers to the book that the Twitter user has been reading. The reading is partitive and conservative: the percentage expresses the ratio of the portion of the book that has been read to the whole book.

- (43)

- Context: a Twitter user is commenting on a book they are reading:

- (…)

- Li

- read

- já

- already

- irritada

- irritated

- por

- by

- ser

- be

- cliché

- cliché

- e

- and

- a

- at

- cada

- each

- capítulo

- chapter

- eu

- I

- falo

- speak

- que

- that

- vou

- go

- parar

- stop

- e

- and

- já

- already

- se

- se

- foram

- went

- 20%

- 20 percent

- de

- of

- livro (…).

- book.

- ‘(…) I was already irritated when reading it because it is cliché, and every chapter I tell myself I am going to stop, and 20% of the book is already gone (…).’ (Twitter)

A similar example is shown in (44). Here, the bare singular filme (‘movie’) is also interpreted as a singular definite description, and the interpretation is partitive and conservative: the fraction expresses a ratio whose numerator is the duration of the movie up to Fassbender’s entrance and whose denominator is the duration of the whole movie.

- (44)

- roteiro

- screenplay

- inteligentíssimo.

- most.intelligent

- o

- the

- Michael

- Michael

- Fassbender

- Fassbender

- entra

- enters

- só

- only

- depois

- after

- de

- of

- um

- one

- terço

- third

- de

- of

- filme (…)

- movie

- ‘Extremely intelligent screenplay. Michael Fassbender only enters after one third of the movie (…).’ (Twitter)

Conservative readings of RMCs are also attested with plural definite interpretations of bare singulars, as illustrated by example (45):

- (45)

- (…)

- dos

- of.the

- 190

- 190

- milhões

- millions

- de

- of

- brasileiros

- Brazilians

- 60

- 60

- milhões

- millions

- têm

- have

- menos

- less

- de

- than

- 18

- 18

- anos.

- years

- É

- it.is

- um

- one

- terço

- third

- de

- of

- criança/adolescente

- child/teenager

- da

- of.the

- América

- America

- Latina/Caribe

- Latin/Caribbean

- ‘(…) Of the 190 millions of Brazilians, 60 millions are less than 18 years old. It is one third of the children/teenager of Latin America/the Caribbean.’ (Twitter)

In this example, the bare singular is interpreted as a plural definite description. The interpretation of the RMC is partitive and conservative: the fraction (one third) expresses the ratio of Latin and American and Caribbean children and teenagers who are Brazilian minors to all Latin American and Caribbean children and teenagers. Note that if we acknowledge that bare singulars may denote kinds (pace Müller 2002 and Müller & Oliveira 2004), (45) can also be analyzed as involving a kind-denoting bare singular.

In sum, BrP bare singulars are attested in RMCs both with conservative and with non-conservative readings. Note that all examples of bare singulars in non-conservative RMCs can be substituted by bare plurals without loss of acceptability, and without change of interpretation. We illustrate with (42), which we reproduce here with the bare plural mulheres (‘women’) instead of the bare singular mulher:

- (46)

- MDB

- MDB

- se

- se

- compromete

- commit

- a

- to

- ter

- have

- 30%

- 30 percent

- de

- of

- mulheres

- women

- nos

- in.the

- cargos

- positions

- de

- of

- direção.

- management

- ‘MDB is committed to including 30% of women in management positions.’ (elicited)

This example is acceptable and keeps its non-conservative interpretation: the percentage expresses the ratio of women to be included in management positions to all people in such positions.

By contrast, substituting bare singulars interpreted as singular definite descriptions by bare plurals changes the interpretation, which may result in infelicity. We illustrate with (44), which we repeat here with a bare plural instead of the bare singular in the original example:

- (47)

- #roteiro

- screenplay

- inteligentíssimo.

- most.intelligent

- o

- the

- Michael

- Michael

- Fassbender

- Fassbender

- entra

- enters

- só

- only

- depois

- after

- de

- of

- um

- one

- terço

- third

- de

- of

- filmes

- movies

The fact that bare singulars can be substituted by bare plurals in non-conservative RMCs without change of meaning and acceptability suggests that in these examples, bare singulars receive the same interpretation as bare plurals. By contrast, bare singulars are not always interchangeable with bare plurals in conservative RMCs. Our analysis of RMCs in BrP should capture these facts. In the next section, we review Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analysis of the compositional interpretation of RMCs. In section 5, we show that this analysis can be applied to BrP and that it captures the interpretation of bare singulars in RMCs, although the picture that emerges raises question about the distribution of bare singulars in RMCs in other languages.

4. The semantics of relative measure constructions

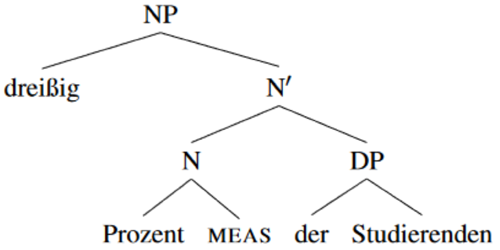

In this section, we will adopt Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analysis of the semantics of RMCs, which builds on Ahn & Sauerland’s (2015; 2017) analysis and improves upon it. Following Ahn & Sauerland (2015; 2017), Pasternak and Sauerland argue that conservative and non-conservative interpretations of RMCs are associated with two different structures. In conservative construals, the measure noun (in 48: Prozent, ‘percent’) combines with a covert head MEAS, and the resulting complex head forms a constituent with the substance noun phrase (here der Studierenden, ‘the students’):

- (48)

- Pasternak & Sauerland (2020: 36)

⟦MEAS⟧c introduces a contextually determined measure function µc. We will restrict our attention to contexts in which µc is cardinality, i.e., µc(x) is the number of atomic individuals that make up x. The complex head ⟦Prozent MEAS⟧c is interpreted as follows (see Pasternak & Sauerland 2020 for details of interpretation):

- (49)

- ⟦Prozent MEAS⟧c = λxλnλy. y ⊑ x ∧ µc(y) ≤ µc(x) ∧ µc(y) ≥ n%[µc(x)]

This complex head then combines with its substance DP and numeral arguments, which leads to the following denotation for (48), where the-students is a shorthand for the denotation of der Studierenden:

- (50)

- ⟦Prozent MEAS⟧c (⟦der Studierenden⟧c)(⟦dreißig⟧c) =

- λy. y ⊑ the-students ∧ µc(y) ≤ µc(the-students) ∧ µc(y) ≥ 30%[µc(the-students)]

(50) is true of an individual y just in case y is part of the students, the cardinality of y is not greater than the cardinality of the students and it is 30% of the cardinality of the students.

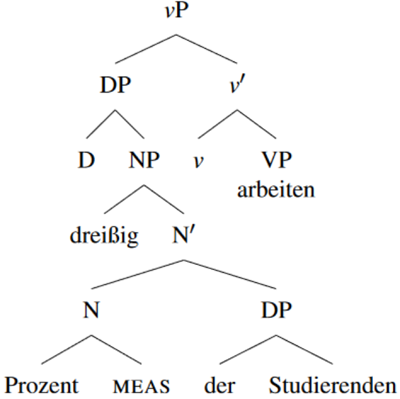

(50) then combines with a covert existential determiner D, as illustrated in (51). Putting aside details of event and tense/aspect semantics, ⟦vP⟧c is true iff there is a part of the students whose cardinality is not greater than that of all the students, this part amounts to 30% of the cardinality of all the students, and it consists of students who work (arbeiten, ‘work’):

- (51)

- Pasternak & Sauerland (2020: 40)

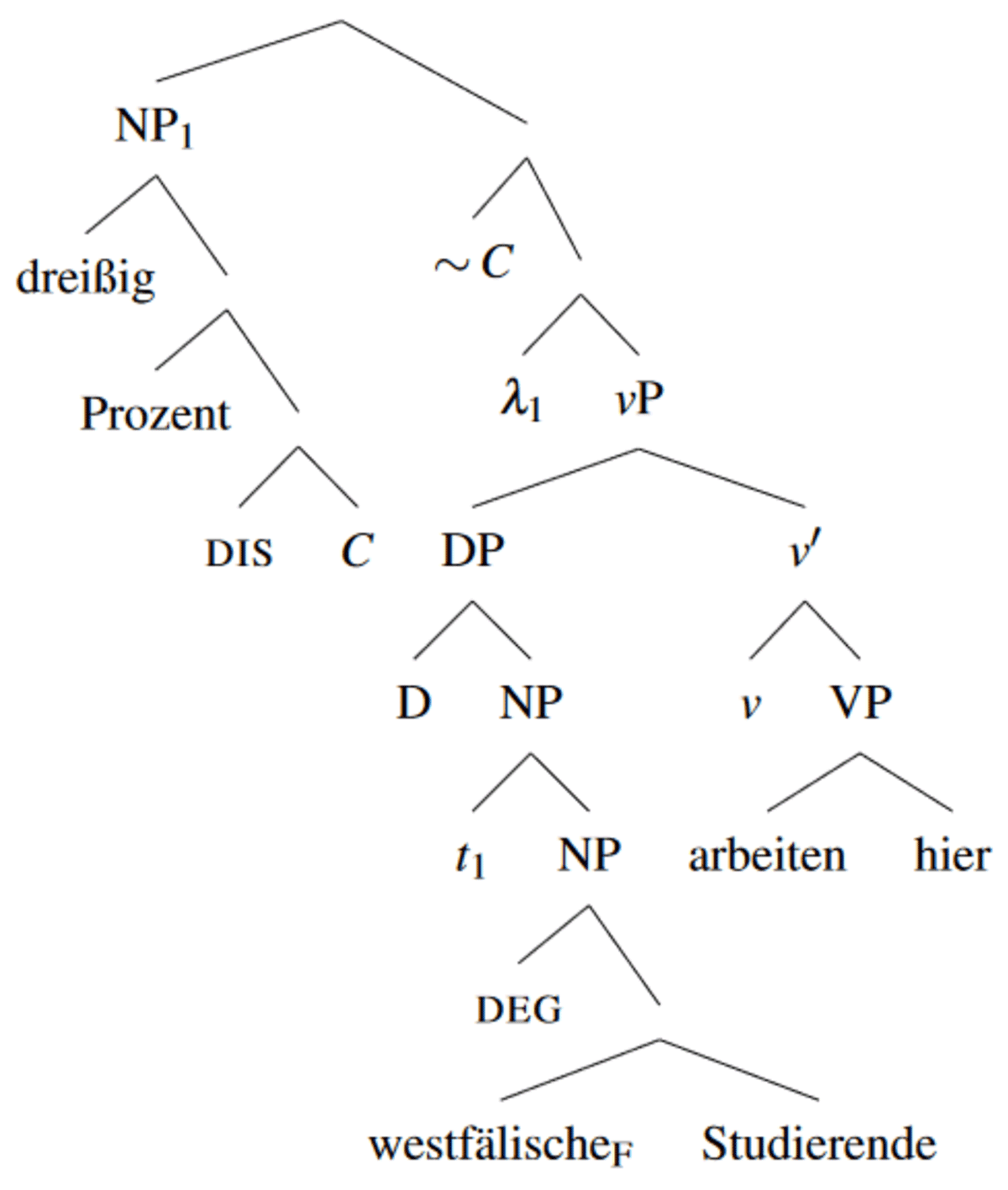

A different structure is required for the non-conservative interpretation. In non-conservative construals, the substance noun/DP is not the complement of Prozent, but undergoes quantifier raising as illustrated in Figure 1, which is the logical form of example (52).

Pasternak & Sauerland (2020: 48).

- (52)

- German (Pasternak & Sauerland 2020: 41)

- Dreißig

- thirty

- Prozent

- percent

- [westfälische]F

- Westphalian

- Studierende

- students

- arbeiten

- work

- here.

- here

- ‘Thirty percent of student workers here are Westphalian.’

In this example, Prozent does not combine with a MEAS operator. Prozent is interpreted as a quantifier over degrees, which combines with a set of degrees D, a numeral n and another set of degrees D′, and returns a statement that is true if and only if D′ is a subset of D and the maximal degree in D′ amounts to n percent of the maximal degree in D:

- (53)

- ⟦Prozent⟧c = λDλn λD′. D′ ⊆ D ∧ max(D′) ≥ n%[max(D)]

In order to derive the correct truth-conditions for example (52), the complement of Prozent must denote the set of positive numbers (i.e., cardinality degrees) that are not greater than the cardinality of all the students who work here, and the sister of NP1 in Figure 1 must denote the set of positive numbers that are not greater than the cardinality of the Westphalian students who work here. The sentence is true if and only if the maximal number in the latter (i.e., the cardinality of the Westphalian students who work here) is thirty percent of the maximal number in the former (i.e., the cardinality of all the students who work here). Let us review briefly how these truth-conditions are derived. The reader is referred to Pasternak & Sauerland (2020) for the full details of the semantic composition.

The sister constituent of the node ~C, which we write in (54) in linear notation, contains the focused expression [westfälische]F. As such, it has both an ordinary denotation and a focus semantic value. Following Rooth’s (1992) analysis of the semantics of focus, the semantic value of the variable C is set to the focus value of this constituent.

- (54)

- λ1 [vP [DP D t1 [NP DEG [westfälische]F Studierende]] arbeiten hier ]

The ordinary denotation of (54) is a set of positive numbers that are not greater than the cardinality of the Westphalian students who work here. The relevant degree argument is introduced by the head DEG:

- (55)

- ⟦(54)⟧c = λd. ∃x [westphalian(x) ∧ student(x) ∧ µc(x) ≤ d ∧ work-here(x) ]

This is the (characteristic function of the) set of degrees that we need as the external argument of ⟦Prozent⟧c in the derivation of the truth-conditions of example (52).

The focus semantic value of (54) is the set of all denotations that are obtained by substituting the property of being Westphalian by an alternative property (such as the property of being Bavarian) in the interpretation of the sister node of ~C:

- (56)

- ⟦(54)⟧c,f = {λd. ∃x [P(x) ∧ student(x) ∧ µc(x) ≤ d ∧ work-here(x) ] | P ∈ ⟦westfälische⟧c,f }

The ~C node sets the semantic value of the variable C to this set. Crucially, Pasternak and Sauerland argue that the universal property λx.⊤, which is true of all individuals, is among the set of alternatives to the property of being Westphalian. Consequently, we can form the set of positive numbers that are no greater than the cardinality of all students who work here by forming the union of all (characteristic functions of) sets in C. This grand union is obtained by combining the operator DIS with C in the complement of Prozent:

- (57)

- ⟦DIS C⟧c = λd. ∃x [student(x) ∧ µc(x) ≤ d ∧ work-here(x) ]

This is the (characteristic function of the) set of degrees that we need as the internal argument of ⟦Prozent⟧c in the derivation of the truth-conditions of example (52).

Let DWS be the set of degrees denoted by (54), and let Dwork be the set of degrees denoted by DIS C. We obtain the following truth-conditions for example (52), which captures the non-conservative construal:

- (58)

- ⟦(52)⟧c = 1 iff DWS ⊆ Dwork ∧ max(DWS) ≥ 30%[max(Dwork)]

It is important to note that while the substance noun phrase must be of type e in Pasternak and Sauerland’s analysis of conservative construals of RMCs (cf. der Studierenden in example (48)), in their analysis of non-conservative construals the substance noun phrase (westfälische Studierende in Figure 1) NP2 must be of type ⟨e,t⟩, otherwise it wouldn’t be able to combine with DEG. In addition, NP2 must be semantically plural or number neutral. Otherwise, if NP2 only included atomic individuals in its extension, the set of cardinalities in (55) would only include the number 1, and max(DWS) could not amount to thirty percent of the cardinality of all students who work here. In sum, Pasternak & Sauerland (2020)’s analysis makes three predictions (which are also predictions of Ahn & Sauerland’s (2015, 2017) analysis):

Definiteness of NP2 (the substance noun) is a predictor of conservative construals.

In non-conservative construals, NP2 must be of predicative (type ⟨e,t⟩).

In non-conservative construals, NP2 must be semantically plural or number neutral.

In the next section, we show that combining Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analysis with existing theories of BrP bare singulars accounts for their distribution and interpretation in RMCs, although it raises questions about the distribution of bare singulars in RMCs in other Romance languages.

5. Analyzing bare singulars in relative measure constructions

In Ahn & Sauerland’s (2015; 2017) and Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analysis of RMCs, conservativity correlates with the interpretation of the substance noun. Substance nouns of type e give rise to conservative readings, while number neutral or plural substance nouns of type ⟨e,t⟩ give rise to non-conservative readings. Together with the analysis of bare singulars we sketched in section 2, this analysis provides a straightforward account of the distribution and interpretation of bare singulars in RMCs.

BrP bare singulars can be used both as arguments of type e and as predicates of type ⟨e,t⟩. In section 2, we reviewed evidence that in both uses, bare singulars are number neutral, as illustrated by examples (24) and (25), repeated here as (59) and (60):

- (59)

- Eu

- I

- vi

- saw

- criança

- child

- na

- in.the

- sala.

- room

- E

- and

- ela

- she

- estava/

- was

- elas

- they

- estavam

- were

- ouvindo.

- listening.

- ‘I saw a child/children in the room. And she was/they were listening.’ (Munn & Schmitt 2005: 825)

- (60)

- Ninguém

- nobody

- poderá

- will.be.able

- usar-nos/usá-lo

- to.use-us/him

- como

- as

- testemunha.

- witness

- ‘Nobody will be able to use us/him as witnesses/as witness’ (Munn & Schmitt 2002)

In (59), the bare singular criança is used as an argument. While in this example criança receives an existential interpretation, Munn and Schmitt argue that this interpretation is derived from a kind-denoting interpretation of type e. Furthermore, we reviewed evidence that non-kind-denoting definite interpretations of bare singulars are also attested in BrP outside of RMCs (see Cyrino & Espinal 2015 and Wall 2017), as illustrated by example (23), repeated here as (61):

- (61)

- “Perdi

- lost

- a

- the

- minha

- my

- aliança!”

- ring

- gritou

- shouted

- Didi.

- Didi

- (…)

- E

- and

- nada

- nothing

- de

- of

- encontrar

- find

- aliança.

- ring

- ‘“I have lost my wedding ring!” cried Didi. (…) And it was impossible to find it.’ (Cyrino & Espinal 2015: 480)

Since definite BrP bare singulars are of type e, Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) analysis predicts that they should be attested in RMCs with a conservative interpretation. This prediction is borne out by the examples of definite bare singulars we reviewed in section 3, such as example (43), repeated here as example (62):

- (62)

- Context: a Twitter user is commenting on a book they are reading:

- (…)

- Li

- read

- já

- already

- irritada

- irritated

- por

- by

- ser

- be

- cliché

- cliché

- e

- and

- a

- at

- cada

- each

- capítulo

- chapter

- eu

- I

- falo

- speak

- que

- that

- vou

- go

- parar

- stop

- e

- and

- já

- already

- se

- se

- foram

- went

- 20%

- 20 percent

- de

- of

- livro (…).

- book.

- ‘(…) I was already irritated when reading it because it is cliché, and every chapter I tell myself I am going to stop, and 20% of the book is already gone (…).’ (Twitter)

The analysis of conservative RMCs sketched in (51) applies directly to this example, as illustrated in (63):12

- (63)

- [S [NP 20 [N [ porcento MEAS ] [ de [DP DDEF [NP livro ]]]]] [VP se foram ]]

Since bare plurals cannot be interpreted as singular definite descriptions in BrP, it is also predicted that bare singulars cannot be substituted by bare plurals in examples like (62). Nevertheless, whenever a bare singular is attested inside a relative measure construction with a kind-denoting interpretation, we expect that it should be substitutable by a kind-denoting bare plural, without changing the conservative interpretation. This prediction appears to be borne out, as illustrated by the equivalence of (64) a and b with the bare plural Americanos and the bare singular Americano:

- (64)

- a.

- Dez

- ten

- porcento

- percent

- de

- of

- Americanos

- Americans

- fumam

- smoke

- Marlboro.

- Marlboro

- ‘Ten percent of Americans smoke Marlboro.’ (elicited)

- b.

- Dez

- ten

- porcento

- percent

- de

- of

- Americano

- American

- fuma

- smoke

- Marlboro.

- Marlboro

- ‘Ten percent of Americans smoke Marlboro.’ (elicited)

BrP bare singulars are also used as predicates with number neutral interpretations, as illustrated in example (60) above. This predicts that bare singulars should be attested in RMCs with non-conservative readings. Since BrP bare plurals are also attested in predicative position with a plural interpretation, we predict that bare singulars should be substitutable by bare plurals in non-conservative RMCs, without changing the interpretation of the constructions. Indeed, we showed examples where two equivalent RMCs occur in the same text, once with a bare singular and once with a bare plural. This was the case in example (40), repeated here as (65), with the RMCs 30% de mulheres and 30% de mulher:

- (65)

- Context: The Brazilian Senate was discussing the approval of a project that would create a rule that in businesses with 50 or more employees 30% of the employees should be women. Some Twitter users discussed how that would impact political parties:

- Tem

- must

- que

- put

- colocar

- thirty

- 30%

- percent

- de

- of

- mulheres,

- women

- certo?

- right

- O

- the

- partido

- part

- que

- that

- não

- neg

- coloca,

- put

- ele

- he

- vai

- will

- incorrer

- incur

- em

- in

- uma

- a

- ilicitude.

- illegality.

- Vários

- many

- candidato-s

- candidate-pl

- masculino-s

- masculine-pl

- foram

- were.pl

- cortados,

- cut.pl

- porque

- because

- tem que

- must

- ter

- have

- 30%

- 30 percent

- de

- of

- mulher,

- woman,

- disse

- said

- Bivar.

- Bivar

- ‘There must be 30% of women, right? The political party that does not include it will be doing something illegal. Several male candidates were cut because we must have 30% of women, said Bivar.’ [Twitter]

Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analysis of non-conservative RMCs also applies directly to these examples, as illustrated in (66):13

- (66)

- [S [NP1 30 [ %[ de [ DIS C ]]]] [ ~C [ λx [S [ D [NP2 tx DEG mulheresF]] [λy[ tem que colocar ty]]]]]]

In sum, given the availability of argumental uses and number neutral predicative uses of bare singulars in BrP, Ahn & Sauerland (2017) and Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analyses provide a straightforward account of the distribution and interpretation of these bare nominals in RMCs. Nevertheless, the success of these analyses in accounting for the use of BrP bare singulars in RMCs raises a question about the acceptability of bare singulars in other Romance languages, where bare singulars have also been argued to have number neutral predicative uses. We formulate this question in the rest of this section.

BrP bare singulars are attested in non-conservative RMCs because they can be interpreted as number neutral predicates of type ⟨e,t⟩. But BrP is not the only Romance language with number neutral predicative bare singulars. Munn & Schmitt (2005) argue that number neutral bare singular predicates are generally attested in Romance languages14 and give evidence of this phenomenon in two Romance languages besides BrP: French and Spanish. We review some of this evidence here.

Like BrP, French and Spanish license bare singular predicates with plural as well as singular subjects:

- a.

- Personne

- nobody

- ne

- NE

- nous/le

- us/him

- pourra

- will.be.able.to

- prendre

- take

- comme

- as

- témoin.

- witness

- ‘Nobody will be able to use us/him as witness.’ (French)

- b.

- Nadie

- nobody

- podrá

- will.be.able.to

- usarnos/usarlo

- use.us/use.him

- como

- as

- testigo

- witness

- ‘Nobody will be able to use us/him as witness.’ (Spanish)

- c.

- Ninguém

- nobody

- poderá

- will.be.able.to

- nos usar/usar-nos/usá-lo

- us to-use/use.us/use.him

- como

- as

- testemunha.

- witness

- ‘Nobody will be able to use us/him as witness.’ (BrP)

Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) also argue that the Spanish and BrP bare singulars cola and rabo (‘tail’) in the part-whole construction illustrated in (68) are predicative15 and can modify plural nouns. While Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) do not give French data for this construction, the same facts hold in French, as illustrated in (69) with the bare singular queue (‘tail’):

- a.

- Compré

- bought

- perros

- dogs

- de

- of

- cola

- tail

- larga.

- long

- ‘I bought dogs with long tails.’ (Spanish)

- b.

- Comprei

- bought

- cachorros

- dogs

- de

- of

- rabo

- tail

- comprido.

- long

- ‘I bought dogs with long tails.’ (BrP)

- (69)

- J’ai

- I=have

- acheté

- bought

- des

- indef.pl

- chiens

- dogs

- à

- with

- queue

- tail

- longue.

- long

- ‘I bought dogs with long tails.’ (French, elicited)

Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) conclude from these facts that number neutral predicative bare singulars are attested not only in BrP but also in French and Spanish. If this argument is correct, then everything else being equal it follows from Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) and Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analyses of RMCs that bare singulars should be attested in RMCs with non-conservative readings not only in BrP but also in French and Spanish. Indeed, predicative bare singulars in these languages have the right type (⟨e,t⟩) and number specification (number neutral) to serve as substance nouns in non-conservative RMCs. As it happens, this prediction is not borne out in French and Spanish, as illustrated by the contrasts between (70) a and b in French and (71) a and b in Spanish:

- (70)

- a.

- Ce

- this

- champ

- field

- contient

- contains

- deux

- two

- tiers

- thirds

- de

- of

- chevaux.

- horses

- ‘Two thirds of the animals in this field are horses.’ (elicited)

- b.

- *Ce

- this

- champ

- field

- contient

- contains

- deux

- two

- tiers

- thirds

- de

- of

- cheval.

- horse

- Intended: ‘Two thirds of the animals in this field are horses.’ (elicited)

- (71)

- a.

- La

- the

- película

- movie

- fue

- was

- vista

- seen

- por

- by

- 1/3

- one third

- de

- of

- periodistas.

- journalists

- ‘Two thirds of the people who have seen this movie are journalists.’ (elicited)

- b.

- *La

- the

- película

- movie

- fue

- was

- vista

- seen

- por

- by

- 1/3

- one third

- de

- of

- periodista.

- journalist

- Intended: ‘Two thirds of the people who have seen this movie are journalists.’ (elicited)

Considering the grammaticality of similar examples in BrP and the shared number neutrality of predicative bare singulars in BrP, French and Spanish, the ungrammaticality of (70) and (71) is unexpected.

It appears then that while we have arrived at a satisfying account of the distribution of BrP bare singulars in RMCs, the combination of Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) and Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analyses of RMCs with number neutral16 analyses of predicative bare singulars in Romance overgenerates in other languages. We have no solution to offer to this dilemma at this moment, and we leave it as a question for future research.

6. Conclusion

We have shown that bare singulars are attested in conservative and non-conservative construals of RMCs in BrP, and we have offered an account of their distribution and interpretation that combines Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) and Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analyses of RMCs with an independently motivated analysis of BrP bare singulars (cf. Schmitt & Munn 1999; 2002; Munn & Schmitt 2002; 2005; Cyrino & Espinal 2015). Insofar as bare singulars are independently attested as arguments of type e, Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) and Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) analyses of RMCs predict that, everything else being equal, they should be felicitous as substance nouns in conservative construals of RMCs. Since BrP are also attested as number neutral predicates of type ⟨e,t⟩, it is also predicted that they should be felicitous as substance nouns in non-conservative construals of RMCs. We showed that these predictions are all borne out. While we have arrived at a satisfying analysis of bare singulars in BrP, we have also identified an outstanding problem for the analysis of bare nominals in RMCs in other Romance languages: non-conservative RMCs with bare singular substance nouns are predicted to be felicitous in any language in which bare singulars have number neutral predicative uses. We showed that this prediction is not borne out, which points to the need for further research on the number neutrality of bare singulars.

Abbreviations

3pl = third person plural, acc = accusative, gen = genitive, indef.pl = indefinite plural, nom = nominative, perf = perfective.

Notes

- Note that gosta (‘likes’) selects prepositional complements introduced by the preposition de (‘of’). In this example, as indicated by the absence of definiteness marking in the glosses, the nominal complement of de is bare. Definiteness of the nominal complement would be marked on the preposition: do(-s) (‘of the.MASC(-PL)’)/da(-s) (‘of the.FEM(-PL)’). [^]

- In (27), ‘⋃’ is a function that maps kinds to properties, so that the extension of ⋃k is the set of instances of the kind k. [^]

- Müller (2002) and Müller & Oliveira (2004) argue that BrP bare singulars are NPs, an analysis that is made possible by their judgments that bare singulars lack kind-denoting interpretations. [^]

- See notably Cyrino & Espinal (2015), who posit a null definite article in D. [^]

- Cyrino & Espinal 2015 maintain that Num is present in bare singulars. [^]

- While Schmitt & Munn’s (1999, 2002), Munn & Schmitt’s (2002, 2005) and others assume that bare singulars are built from common count nouns whose extension only contains singular individuals (Carlsonian objects) and their sums, Cyrino & Espinal (2015) argue that the lexical heads of bare singulars denote properties of kinds rather than of Carlsonian objects. Müller & Oliveira (2004) argue that the extension of common count nouns includes not only individuals but also the ‘stuff’ normally found in the extension of mass nouns, and Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein (2011) argue that BrP count root nouns can be freely lexicalized as mass or count. [^]

- Adapted from Ahn & Sauerland’s (2017) example (16a): Ten percent of Americans smoke Marlboro. [^]

- https://unric.org/pt/um-terco-de-mulheres-e-meninas-e-vitima-de-violencia/. [^]

- Ahn and Sauerland (2017: 243) observe that languages that mark non-conservativity with case (German, Georgian, Greek and Korean) do not display this asymmetry. [^]

- Ahn and Sauerland (2017: 243) report that in Italian, the non-conservative interpretation may be attested in the subject and object positions:

- a.

- Un terzo

- a third

- di

- of

- donne

- women

- ha

- have

- parlato

- talked

- a

- with

- Gianni.

- Gianni

- ‘A third of those who talked to Gianni were women.’ (non-conservative)

[^]- b.

- ?Ha

- have

- parlato

- talked

- a

- with

- Gianni

- Gianni

- un

- a

- terzo

- third

- di

- of

- donne.

- women

- ‘A third of those who talked to Gianni were women.’ (non-conservative)

- https://oglobo.globo.com/epoca/guilherme-amado/mdb-se-compromete-ter-30-de-mulher-nos-cargos-de-direcao-1-24593552. [^]

- In (63), we omit the Agr projection that Schmitt & Munn (1999; 2002) and Munn & Schmitt (2002; 2005) posit in bare singular arguments. [^]

- An anonymous reviewer points out that there is no evidence of syntactic movement of the measure phrase posited by Pasternak & Sauerland (2020) in BrP RMCs. Since this movement is a form of Quantifier Raising, and QR can be covert in BrP, we believe that this is not problematic. The same reviewer points out that there is no prosodic F-marking in non-conservative readings of BrP RMCs, which raises the question whether Pasternak & Sauerland’s (2020) focus sensitive analysis of RMCs is appropriate for BrP. We acknowledge that this is a legitimate concern, since focus is prosodically marked in BrP (see Menuzzi & Roisemberg 2010). We note that the relation between F-marking and its prosodic realization is complex (see Schwarzschild 1999; Büring 2006), and we hypothesize that the substance noun phrase in non-conservative readings of BrP RMCs might be F-marked without necessarily being accented. We leave further investigation of this question to future research. [^]

- More precisely, Munn & Schmitt (2005) argue that number specification can be missing from bare singular predicates in Romance. Schmitt & Munn (1999) and Munn & Schmitt (2002) associate lack of number specification with a number neutral denotation: “On the assumption that Num is what turns an NP into a singular or plural noun, it follows that NPs are undifferentiated for singular or plural. This means that the denotation of a noun consists of both atoms and pluralities of atoms in the case of count nouns (…). When Num is added to a count noun, it either strips away the atoms (in the case of plural) or strips away the pluralities (in the case of singular).” (Schmitt & Munn 2002: 211). [^]

- Munn & Schmitt (2002) analyze these constructions as involving modification rather than primary predication. For the present argument, what matters is that the bare singular has predicative type, i.e. ⟨e,t⟩ rather than e. [^]

- Note that the same problem arises for analyses that interpret the data in (67) to (69) as evidence that bare singulars are ambiguously specified for singular or plural number rather than number neutral, such as Cyrino & Espinal (2015). [^]

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors of this volume, Uli Sauerland and Robert Pasternak, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Ahn, Dorothy & Sauerland, Uli. 2015. The grammar of relative measurement. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 25. 125–142. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v25i0.3062

Ahn, Dorothy & Sauerland, Uli. 2017. Measure constructions with relative measures: Towards a syntax of non-conservative construals. The Linguistic Review 34(2). 215–248. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2017-0001

Büring, Daniel. 2006. Intonation and Meaning. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199226269.001.0001

Carlson, Gregory. 1977. Reference to kinds in English. PhD., University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across languages. Natural language semantics 6(4). 339–405. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008324218506

Cyrino, Sonia & Espinal, M. Teresa. 2015. Bare nominals in Brazilian Portuguese: more on the DP/NP analysis. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 33(2). 471–521. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9264-6

Dobrovie-Sorin, Carmen & Pires de Oliveira, Roberta. (2008). Reference to Kinds in Brazilian Portuguese: Definite Singulars vs. Bare Singulars. Proceedings of Sinn Und Bedeutung 12. 107–121. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2008.v12i0.579

Ferreira, Marcelo. 2021. Bare Nominals in Brazilian Portuguese. The Oxford Handbook of Grammatical Number, 497–521. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198795858.013.24

Menuzzi, Sérgio de Moura & Figueiredo Silva, Maria Cristina & Doetjes, Jenny. 2015. Subject bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese and information structure. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 14(1). 7–44. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.56

Menuzzi, Sérgio de Moura & Roisemberg, Gabriel. 2010. Tópicos contrastivos e contraste temático: um estudo do papel discursivo da articulação informacional. Cadernos de Estudos Linguísticos 52(2). 233–253. DOI: http://doi.org/10.20396/cel.v52i2.8637191

Müller, Ana. 2002. The semantics of generic quantification in Brazilian Portuguese. Probus 14(2). 279–298. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/prbs.2002.011

Müller, Ana & Oliveira, Fátima. 2004. Bare nominals and number in Brazilian and European Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 3(1). 9–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.17

Munn, Alan & Schmitt, Cristina. 2002. Bare Nouns and the Morphosyntax of Number. In Satterfield, Teresa & Tortora, Christina & Cresti, Diana (eds.), Current Issues in Romance Languages: Selected papers from the 29th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), 217–231. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.220.16mun

Munn, Alan & Schmitt, Cristina. 2005. Number and indefinites. Lingua 115(6). 821–855. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2004.01.007

Pasternak, Robert & Sauerland, Uli. 2020. German measurement structures: Case-marking and non-conservativity. Manuscript accessed at https://lingbuzz.net/lingbuzz/005202/v1.pdf

Pires de Oliveira, Roberta & Mariano, Ruan. 2011. MulherF discutiu futebol na festa ontem! Estrutura infomacional e os nomes nus no PB. In Foltran, Maria J. (ed.), Anais do VII Congresso Internacional da Abralin, Curitiba, 3744–3756.

Pires de Oliveira, Roberta & Rothstein, Susan. 2011. Bare singular noun phrases are mass in Brazilian Portuguese. Lingua 121(15). 2153–2175. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2011.09.004

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1(1). 75–116. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF02342617

Schmitt, Cristina & Munn, Alan. 1999. Against the nominal mapping parameter: Bare nouns in Brazilian Portuguese. In Tamanji, Pius & Hirotani, Masako & Hall, Nancy (eds.), Proceedings of North Eastern Linguistic Society 29, 339–354. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Schmitt, Cristina & Munn, Alan. 2002. The syntax and semantics of bare arguments in Brazilian Portuguese. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 2. 185–216. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/livy.2.08sch

Schwarzschild, Roger. 1999. Givenness, Avoid F, and other constraints on the placement of accent. Natural Language Semantics 7. 141–177. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008370902407

Wall, Albert. 2017. Bare Nominals in Brazilian Portuguese: an integral approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.245