1 Introduction

Ideophones have long been considered one of the few examples of lexicalised iconicity in spoken language. Examples include the English splish-splash and helter-skelter and German plitsch-platsch and holterdiepolter. Until now research into ideophones has focused on areas such as sound-symbolism or semantic typology (see Dingemanse 2012 for an overview) and there has been little to no research on their pragmatic status. Recent years, however, have seen a growing interest in understanding the role of iconicity in spoken language and how iconic enrichments, such as ideophones and gestures, contribute to meaning. Experimental investigations into iconic co-speech gestures (cf. Tieu et al. 2017; 2018; Ebert et al. 2020) have, for example, shown that these gestures are by default not at-issue. It has been argued that iconic co-speech gestures contribute information in a similar manner to linguistic items such as expressives (i.e. damn) and appositives, as in the highlighted clause in (1), (cf. Ebert & Ebert 2014; Ebert et al. 2020), while others have claimed that they resemble presuppositions (cf. Schlenker 2018a).

- (1)

- Peter, who is the best musician in town, came to dinner last night.

Here, we present experimental research that expands the exploration of iconic meaning from gestures into the spoken modality by empirically testing the at-issue status of ideophones in German. As far as we are aware this is the first study into the at-issue status of ideophones. We claim that sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German, such as in (2),1 can also contribute not-at-issue information.

- (2)

- Der

- The

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

Using an adapted version of Ebert et al. (2020)’s co-speech gesture experiment, we tested sentences containing ideophones in a sentence-context matching task. The results indicate that sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German can contribute not-at-issue information. While German is not necessarily a prototypical ideophonic language, we argue that ideophones do form part of its linguistic system and that the findings and observations presented here align with the crosslinguistic evidence on the at-issue status of ideophones. Furthermore, the findings are comparable, but not identical, to the results of experimental work conducted on iconic co-speech gestures, which contributes to our overall understanding of the at-issue status of iconic enrichments, as well as our knowledge of the relationship between iconic gestures and ideophones, as two of the main iconic enrichments in spoken language (cf. Dingemanse 2013; 2015; 2017; Dingemanse & Akita 2016; Nuckolls 2019).

This paper will be structured as follows: Section 2 will give background information on pragmatic contributions and at-issueness, as well as previous research conducted on iconic gestures. Section 3 will discuss previous research on ideophones and the nature of ideophones in German. Section 4 will outline two pre-studies and two experiments that were conducted as part of this research. Section 5 will include a discussion of what exactly the meaning contribution of not-at-issue ideophones could be, based on the evidence in this paper, before considering the implications of this research for our understanding of the contributions of iconic enrichments in language. Section 6 will conclude the paper.

2 Background

2.1 Iconicity in language

Within formal linguistics, it is generally assumed that form-meaning relations in spoken language are arbitrary and not iconic. De Saussure (1916) argued that there is no logical or intrinsic relationship between the linguistic sign and the object or concept to which it refers. For example, there is no logical reason a chair is called chair; it could just as well be called table. Instead of iconic mappings, speech communities rely upon arbitrary, conventionalised forms in order to communicate. Linguistic forms that do employ iconicity, such as onomatopoeic words like bang or ideophones like splish splash, have been considered exceptions to this rule, with arbitrariness being considered a major principle in natural language. Hockett (1960) even named arbitrariness as a design feature of human language.

Recently, however, researchers have begun to examine iconicity in spoken language more closely. Blasi et al. (2016) found strong associations between basic vocabulary items and specific human speech sounds. Upon analysing word lists of 100 basic vocabulary items from almost two thirds of the world’s languages, Blasi et al. (2016) found that a large proportion of these languages show biases for carrying or avoiding specific sound segments. Biases were particularly common in items referring to body parts, with “tongue”, for example, often being associated with the lateral “l” and “nose” with the alveolar nasal “n”. This data raises questions about how arbitrary conventionalised linguistic items are, with iconicity seeming to play a larger role than previously thought. Furthermore, Blasi et al. (2016) argue that these associations emerge independently from one another, suggesting that they are not due to vocabulary items sharing linguistic origins, but rather that languages share preferences for sound-symbolic encodings.

Perniss et al. (2010) have also argued for the importance of iconicity in language after reviewing iconic mappings in signed and spoken language. It has often been claimed that sign languages are naturally more iconic than spoken language due to their occurrence in the visual modality, which, it is argued, allows for a greater exploitation of iconicity. Perniss et al. (2010), however, found that iconic mappings are used across both the spoken and signed modality and that both speakers and signers exploit iconicity in language processing and acquisition. For example, they cite studies which indicate that children may acquire iconic vocabulary more easily than arbitrary vocabulary. They argue that while arbitrariness still plays a crucial role in language, iconicity should also be considered as a general property of language. Flaksman (2017) has gone a step further and argued that language has a requirement for expressivity, which is satisfied by iconic words. She proposes the “iconic treadmill hypothesis”, where iconic words necessarily lose their iconicity over time, due to the pressure of the arbitrary system, meaning that they also lose their expressivity. This loss of expressivity then forces the introduction of new iconic coinages, which explains the continuing emergence of new iconic words across languages.

It has also been suggested that gestures should be taken into account when considering iconicity in spoken language, as they may allow speakers the same iconic expressiveness that is available to signers (cf. Goldin-Meadow & Brentari 2017; Schlenker 2018c). Indeed, in pioneering work conducted by Kendon (1980) and McNeill (1992), it was found that gestures can introduce information additional to that contributed by the accompanying speech. Nevertheless, while gestures have been of great interest in semiotics and other fields of linguistics, such as language acquisition, only recently has the nature of their meaning contributions become of interest to semanticists. Ebert et al. (2020), Schlenker (2018a) and Esipova (2019) have all proposed theories concerning the meaning contributions of iconic gestures, focusing on their pragmatic status and in particular on whether they are at-issue or not (see Section 2.3).

Similarly, there has been much research into the crosslinguistic typology of ideophones and their sound symbolism, but there has been little to no research into their pragmatic status and only little consideration given to their semantics (cf. Dingemanse 2012; 2013; Dingemanse et al. 2016; Henderson 2016; Kawahara 2020). In this research, we aim to give an initial overview of the evidence around the (non-)at-issueness of ideophones in the existing crosslinguistic literature before looking more closely at the at-issue status of ideophones in German and gathering initial experimental data using the framework established by Ebert et al. (2020) in their work on iconic co-speech gestures.

In the remainder of this section, we will provide an explanation of what is meant by at-issue status, as well as the theoretical background on at-issueness, before moving on to discuss the research conducted into the at-issue status of iconic gestures.

2.2 Pragmatic status: At-issue vs. not-at-issue

It has long been acknowledged that information contributed by conventional implicatures and presuppositions appears to differ from that of standard assertions; this information is not at-issue. Potts (2005) introduced the terms at-issue and not-at-issue to describe what Paul Grice (1975) termed “what is said” and “what is implicated”. At-issue information is that which the speaker primarily wants to focus on in conversation; it indicates the direction in which the speaker wishes to steer the conversation. Not-at-issue information, on the other hand, is that which the speaker provides as additional information, but that they do not want to pursue in the conversation. Simons et al. (2010) argue that at-issueness is determined by relevance to the Question Under Discussion (QUD). An assertion is relevant to the QUD if it contextually entails a complete or partial answer to the QUD, whereas a question is relevant if it has an answer which contextually entails a complete or partial answer to the QUD. Simons et al. (2010) define relevance to a QUD using the yes/no question associated with a proposition; ?p denotes the question whether p, or the partition of the set of worlds into p and ¬p. They then give the following formal definition of at-issueness (p.323):

- (3)

- a.

- A proposition p is at-issue iff the speaker intends to address the QUD via ?p.

- b.

- An intention to address the QUD via ?p is felicitous only if:

- • ?p is relevant to the QUD, and

- • the speaker can reasonably expect the addressee to recognise this intention.

According to this definition, at-issueness depends predominantly on the QUD; if information is a potential answer to the QUD, then it is at-issue. Simons et al. (2010) also highlight that some constructions and lexical items conventionally mark their content as not at-issue. In such cases, if the sentence is otherwise felicitous, speakers will assume the item linguistically marked as not at-issue does not address the QUD. Nevertheless, they also argue that such items are marked in a way that allows the items to be interpreted as at-issue, when necessary.

Expressives such as damn are common instances of lexical items with not-at-issue content, as can be seen in (4).

- (4)

- Ed refuses to look after Sheila’s damn dog.

- Potts (2003: p.2)

Here, what is at-issue is that Ed refuses to look after Sheila’s dog; the speaker asserts this and we can see intuitively that it is the main aim of their utterance. However, damn provides additional information about the speaker’s attitude to Sheila’s dog or the general situation at hand, for example, that the speaker does not like dogs or disapproves of Ed being asked to look after the dog. This meaning is not at-issue and is not put up for discussion by the speaker; they are not attempting to address the QUD via damn. As such, while it is perfectly possible to target the asserted, at-issue information with a direct denial, the not-at-issue contribution cannot be targeted in this manner, but must be addressed via a discourse interrupting interaction, as in (5) (see von Fintel 2004, who originally proposed the ‘Hey wait a minute’ as a way to test for presuppositional content; Potts 2015 who extended the test to all not-at-issue content; and Syrett & Koev 2014 who provide critical discussion of the limitations of this test).

- (5)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- Ed refuses to look after Sheila’s damn dog.

- No, that’s not true. Ed is happy to look after Sheila’s dog.

- #No, that’s not true. Sheila’s dog is lovely.

- Hey, wait a minute! Sheila’s dog is lovely.

Other key characteristics of not-at-issue information are that it cannot be interpreted in the scope of modal operators or negation, i.e. it projects, and it can be ignored under ellipsis (Potts 2005).

Alongside expressives, appositives are another oft-cited source of not-at-issue information. This can be seen in (6), where again it intuitively seems that the speaker does not want to discuss whether or not Peter is the best musician in town, but rather their aim is to communicate that Peter came for dinner the previous evening.

- (6)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- Peter, the best musician in town, came for dinner last night.

- No, that’s not true. Peter went to the Smiths’ for dinner last night.

- #No, that’s not true. Maria is the best musician in town.

- Hey, wait a minute! Maria is the best musician in town!

However, in both experimental research conducted by Syrett & Koev (2014) and theoretical work by Anderbois et al. (2013) and Nouwen (2007), it has been shown that while nominal appositives, such as in (6), and sentence-medial appositive relative clauses (i.e. who is the best musician in town) are predominantly not at-issue, sentence-final appositive relative clauses can be at-issue, as in (7), where the appositive can be targeted by direct denial. This indicates that the structural position of information can also impact upon its at-issue status.

- (7)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- Last night we had dinner with Peter, who is the best musician in town.

- No, that’s not true. Peter went to the Smiths’ for dinner last night.

- No, that’s not true. Maria is the best musician in town.

Syrett & Koev (2014) argue that the reason why who is the best musician in town can be at-issue in (7), but not in (6) is because appositive relative clauses are able to compete with the main assertion for at-issue status. By varying their order relative to the main clause, they become more viable candidates for at-issue status. This explanation is compatible with a graded view of at-issueness (cf. Ebert 2017; Tonhauser et al. 2018), where information competes for at-issue status, so that the more standalone a piece of information is, the more likely it is to be at-issue; hence why appositive relative clauses occurring sentence finally would be better candidates for at-issue status.

Contrary to traditional literature on not-at-issue content, which claims that such items do not straightforwardly contribute to truth values (cf. Bach 1999; Dever 2001), Syrett & Koev (2014) argue that their experiment shows that false information presented in an appositive will impact on overall truth conditions, resulting in a truth value judgement of false for the entire sentence. However, experimental research by Kroll & Rysling (2019) investigated the impact of false information presented in appositives and main clauses on truth value judgements. Their findings indicate that information which is false, but also irrelevant to the QUD will, in fact, have less impact on truth values than false information which is relevant to the QUD. Assuming Simons et al. (2010)’s definition of at-issueness as relevance to the QUD, we can then surmise that information which is not relevant to the QUD and therefore not at-issue will have less of an impact on truth values. Interestingly, Kroll & Rysling (2019) argue that this impact is seen regardless of whether the false information is presented in an appositive or not. It is possible then that participants in Syrett & Koev (2014)’s experiment interpreted the false information in the appositives as relevant to the QUD and therefore at-issue, hence the greater impact that this had on truth value judgements. Whether this is due to their experimental design or a property of appositives themselves remains to be seen.

As well as being well attested in arbitrary linguistic items, research conducted by Ebert et al. (2020) and Schlenker (2018a) has shown that iconic co-speech gestures, similarly to expressives and appositives, can also contribute not-at-issue information in addition to the information contributed by the speech with which they co-occur. There has, up to now, been no experimental work conducted on ideophones. However, Dingemanse (2013) has argued that they do not describe, but rather depict, meaning that, through the use of an iconic performance, ideophones illustrate an event rather than using arbitrary linguistic signs to refer to concepts. Although this in itself does not necessarily indicate that ideophones are not at-issue, it does imply that they contribute information in a different manner to arbitrary items, which could suggest that they are not at-issue. A further indication of ideophones’ not-at-issue status is that they appear to share characteristics of typically not-at-issue items, namely that they appear to not be subject to negation (cf. Kita 1997; 2001; Dingemanse 2017; Toratani 2018) and similarly to supplements they tend to provide new information rather than old or backgrounded information (cf. Dingemanse 2017).

In the following section, we will provide background on the aforementioned studies that have been conducted on iconic gestures, focusing particularly on Ebert et al. (2020), as our research on ideophones uses an adapted version of their experimental design.

2.3 Iconic gestures

Gestures are for the most part non-conventionalised, non-combinatorial and non-recursive and are typically performed simultaneously with speech (co-speech gestures) (Kendon 1980; McNeill 1992). Co-speech gestures can, as previously discussed, add new information in addition to the speech (Kendon 1980; McNeill 1992), although all co-speech gestures typically rely on the context in which they occur for interpretation (cf. McNeill 1992; Lücking et al. 2013). There are also a variety of different gestures, including emblematic gestures, such as the thumbs up gesture, beat gestures and turn-taking gestures (McNeill 1992). In this paper, we will only be concerned with iconic gestures.

Several studies on iconic co-speech gestures have found evidence for their default not-at-issue status. Tieu et al. (2017; 2018), for example, performed experiments with truth-value judgements, picture-matching tasks and inferential judgements showing that co-speech gestures project in a way that would be unlikely if they were at-issue. Ebert et al. (2020) also provided evidence for the not-at-issue status of co-speech gestures in an experiment using a sentence-picture matching task.

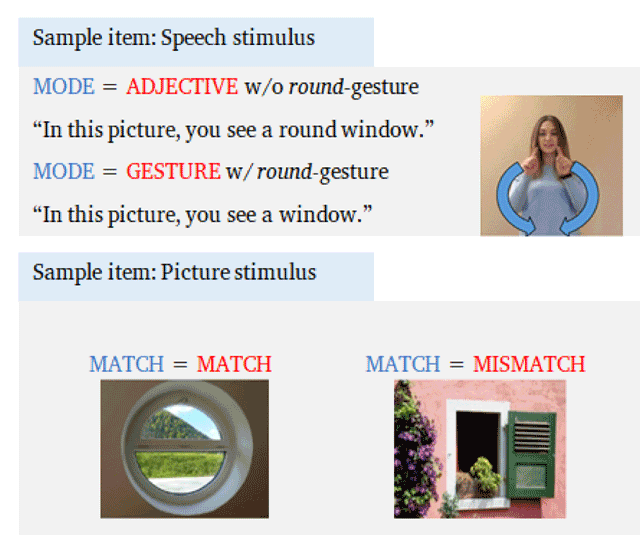

The experiment used a 2 × 2 design with two mode conditions, iconic co-speech gestures and adjectives, and two match conditions, match and mismatch. In the experiment, participants were shown a video of a female speaker uttering a sentence which was either accompanied by a gesture, which was temporally aligned with an NP, or an adjectival description of an NP. The video was paired with a picture, which either matched the sentence or was a mismatch, as in Figure 1. Participants were then asked to rate how well the given description matched the image.

Sample item (Ebert et al. 2019).

According to traditional literature on not-at-issue meaning, speakers will struggle to judge a sentence as true or false when it contains false not-at-issue information, but true at-issue information (cf. Bach 1999; Dever 2001). Per Bach (1999) speakers will find something both wrong and right with such a sentence. As such, this experiment employed an indirect test of at-issue status, where participants evaluated the truth of the target sentence relative to the situation given in the picture by rating how well the circumstances in the target sentence matched those in the picture. This use of a scale and meta-question, in place of directly asking if the sentence was true or false, allowed for subtleties of judgements, with participants still being able to indicate that they disliked sentences with false not-at-issue content. There was also an implicit, generic QUD such as ‘What is happening?’, which was assumed for the whole experiment. It was expected that speakers’ judgements concerning how well the description given in the video matched the picture they were shown should be more strongly impaired by mismatches induced by information deemed relevant to the QUD, i.e. at-issue material, than by mismatches induced by information not relevant to the QUD, i.e. not at-issue material. The specific hypothesis of the experiment was, therefore, an interaction of the factors mode and match such that, if iconic co-speech gestures are not at-issue, then the mismatch effect, i.e. the difference in ratings for matching and mismatching conditions, would be significantly larger for mismatches induced by adjectives, which clearly contribute at-issue information, than those induced by gestures.

The mismatch effect was significantly larger for sentences containing adjectival descriptions than those accompanied by iconic co-speech gestures, supporting the hypothesis of the experiment and therefore indicating that iconic co-speech gestures are not at-issue.

Although Schlenker (2018a) and Ebert et al. (2020) agree upon the default not-at-issue status of iconic co-speech gestures, the exact contribution of these gestures is still disputed. Schlenker (2018a) argues, for example, that they are a special type of presupposition, which he terms cosuppositions. Ebert et al. (2020), however, give an analysis of iconic co-speech gestures as Pottsian supplements, treating them as equivalent to appositives. These two theories make different predictions about the behaviour of the gestures in terms of their informativity and how they behave when they are embedded, for example under negation and negative quantifiers.

Co-speech gestures can also contribute at-issue information, although again, there are differing analyses as to when and why this is the case. Schlenker (2018a) argues that co-speech gestures, as cosuppositions, can be locally accommodated in the same manner as presuppositions. Ebert et al. (2020), on the other hand, propose that co-speech gestures can only be at-issue if they are accompanied by a dimension shifter. Dimension shifters can include particular prosody, focus or facial expressions, such as an eyebrow raise. Ebert et al. (2020) have also shown experimentally that demonstratives can shift co-speech gestures to at-issue status and have argued for demonstratives as dimension shifters. They repeated the previously described experiment, this time including a third MODE condition, where the iconic gesture was accompanied by the German demonstrative SO. All other aspects of the experiment were kept the same. The results for adjectives and iconic gestures without a demonstrative remained the same, however, in the mismatching condition, iconic gestures accompanied by a demonstrative showed a larger mismatch effect than those without a demonstrative, although not as large as that seen for the adjectives. This indicates that the demonstrative SO shifts the co-speech gesture towards at-issueness, but also suggests that at-issueness is not necessarily binary, but rather gradient. In contrast to Ebert et al. (2020) and Schlenker (2018a), Esipova (2019) presents a third view of when iconic gestures are at-issue or not, arguing that at-issueness is independent of modality and that at-issue and not-at-issue content should instead be considered in terms of restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers, respectively.

As noted by McNeill (1992), the temporal alignment of speech and gesture also plays an important role and it appears that it can also affect the gesture’s pragmatic status, just as the structural positioning of appositives affects their at-issue status (Syrett & Koev 2014). In a graded approach to at-issueness (cf. Section 2.2), co-speech gestures always face competition from the accompanying speech for at-issue status and therefore, unless they are shifted to at-issue status, for example by being accompanied by a demonstrative such as SO, they are generally not at-issue. However, in cases where gesture replaces speech completely, so-called pro-speech gestures (cf. Schlenker 2018b), there is no competition and so the gesture is at-issue. Ebert (2017) has also proposed that post-speech gestures are more likely to be at-issue due to the lack of competition with speech and their standalone temporal positioning, which would demonstrate another similarity between iconic gestures and appositives. It would then also be expected that pre-speech gestures are more at-issue, although these may be deemed more odd as they do not have a gesture referent given by previous speech.

In the following section, we will turn to ideophones and discuss previous research on these, focusing particularly on the predictions this makes for their at-issue status and the factors that may play a role in this, before looking at how this aligns with the evidence from ideophones in German.

3 Ideophones

Ideophones have been argued to be a universal or near-universal feature of human language (cf. Diffloth 1972, Kilian 2001; both as per Dingemanse 2012), but as Dingemanse (2012) notes, some languages have a much larger inventory than others. Japanese, the Bantu languages of South Africa and Quechua are all considered to be prototypical ideophonic languages containing ideophones that depict a range of sensory and perceptual imagery (cf. Dingemanse 2012; 2019). While the class of ideophones in German does not come close to the systems present in these languages, we argue that German ideophones do meet the definition given by Dingemanse (2019) and therefore do form part of the linguistic system in German (see Section 3.2 for further discussion).

Dingemanse (2019: p.16) defines ideophones as “an open lexical class of marked words that depict sensory imagery”, in that they are conventionalised items with specifiable meanings that are structurally marked in their given languages and rely upon “perceptual knowledge that derives from the sensory perception of the environment and the body” (Dingemanse 2012: p.655). Dingemanse (2019) argues that the size of ideophones’ lexical class in languages such as Japanese is comparable to other open syntactic classes, indicating that ideophones also belong to an open class, although the items within the class do not necessarily all belong to the same syntactic category. Furthermore, new ideophones can be added to the class via ideophonisation and ideophone creation. Crucially, Dingemanse argues that ideophones depict rather than describe. Dingemanse (2013) illustrates the difference between description and depiction using an ideophone, tyádityadi, from Ewe, a Kwa language spoken in Ghana and Togo, which is roughly equivalent to “be walking with a limp”. While the latter describes an event of walking with a limp, using arbitrary signs interpreted according to a conventionalised linguistic system, the former is iconic and according to Dingemanse part of a performance that illustrates the event of walking with a limp through a combination of speech rate, loudness, phonation type and even gesture. Dingemanse highlights that the ideophone would likely be accompanied by intonational foregrounding and extra reduplication when used in Ewe.

In the rest of Section 3, we will look at previous research and literature on ideophones and discuss how this enables us to make predictions for the at-issue status of ideophones, before moving on to look at how these predictions play out for ideophones in German.

3.1 Ideophones and at-issueness

Up to now, research on ideophones has predominantly focused on sound symbolism and iconicity, as well as their crosslinguistic typology, which includes exploring the semantic categories that can be expressed by ideophones. However, there has been little investigation of their semantics or pragmatics (see Henderson 2016; Kawahara 2020 for semantic analyses of ideophones in Tseltal and Japanese, respectively). In discussing their pragmatic properties, Nuckolls (1992) has argued that ideophones are an example of sound-symbolic involvement, where the speaker iconically simulates the salient features of an event and in doing so, encourages the listener to project themselves into the simulation and they, therefore, become involved in the narrative. Tolskaya (2011) has also given an account of ideophones, in which they are restricted to reports of events that the speaker themselves has witnessed, although the prevalent use of ideophones in narration and storytelling makes this theory seem unlikely. Dingemanse (2011) instead argues that due to their depiction of sensory imagery, ideophones index epistemic authority, where the speaker has relative authority over their interlocutor(s) with respect to what is said, which seems to encapsulate the core idea of Tolskaya (2011)’s analysis, without making such a strong claim. As far as we are aware, though, there is no research which directly investigates the at-issueness of ideophones. Nevertheless, the crosslinguistic research is rich enough that we are able to make reasonable predictions about the (not)at-issueness of ideophones and the factors that may impact upon it.

As discussed in Section 2.2, for us, the fact that ideophones depict rather than describe, indicates that they contribute information in a different manner to other more arbitrary items.

Other characteristics of ideophones also appear to support a not-at-issue analysis, as they exhibit properties typical of not-at-issue content. Dingemanse (2017) notes that ideophones in Siwu are generally not subject to negation or used in questions and that they also provide new, rather than old or backgrounded information, which Potts (2005) has argued is characteristic of supplements (see Section 5.1 for further discussion of the exact not-at-issue contribution of ideophones). He also indicates that this is the case across many languages and indeed, it has been noted in Japanese by Kita (1997; 2001) and Toratani (2018). Kita (1997; 2001) in fact provides a two-dimensional analysis of Japanese ideophones that shares similarities with the multidimensional account of conventional implicatures given by Potts (2005). In this account, ideophones occur in the affecto-imagistic dimension, while other parts of speech occur in the analytic dimension, which, he argues, explains why ideophones in Japanese cannot be logically negated. Although more recent accounts of not-at-issue content have adopted a uni-dimensional approach (cf. Anderbois et al. 2013) to allow for anaphoric relations between at-issue and not-at-issue content, the analysis provided by Kita (1997; 2001) seems to be fundamentally compatible with a not-at-issue interpretation of ideophones.

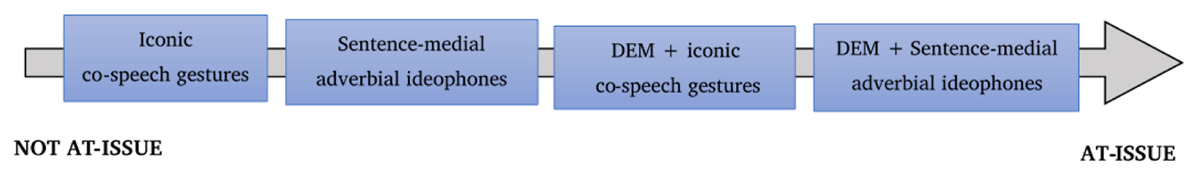

There do appear however to be other additional factors which can impact on the at-issue status of ideophones. In particular, the crosslinguistic literature indicates three factors which influence the (not-)at-issue interpretation of ideophones, namely: how morphosyntactically integrated the ideophone is, whether it is accompanied by a demonstrative or quotative marker and its alignment and timing with respect to the main utterance. We will address now each of these factors individually.

3.1.1 Morphosyntactic integration

Dingemanse (2017) distinguishes between Bound and Free ideophone constructions in Siwu. Adverbial ideophones, along with complement and holophrase ideophones account for around 84% of corpus tokens for Siwu and due to their relative syntactic flexibility, fall into the Free category. On the other hand, adjectival and predicative ideophones, which account for 11% of tokens, are Bound constructions, being more syntactically integrated and according to Dingemanse, behaving much more like ordinary words. Importantly, Dingemanse (2017) also highlights that Bound ideophone constructions are able to be negated, can be used in questions and can provide old or backgrounded information, which is not the case for the Free constructions, nor for many ideophone constructions in other languages, as noted in Section 3.1. In other words, the more morphosyntactically integrated ideophones appear to demonstrate more typical at-issue behaviour. Kita (2001) has also noted a similar distinction for predicative and adverbial ideophones in Japanese. According to Dingemanse (2017), more frequently used ideophones in Siwu are also more likely to be used as verbs, behave like ordinary words and be subject to deideophonisation. Furthermore, Dingemanse (2017) suggests that more morphosyntactically integrated ideophones in Siwu are less expressive,2 something that Dingemanse & Akita (2016) have also shown for ideophones in Japanese. It appears therefore that there is a relationship between morphosyntactic integration and the at-issue status of ideophones, where the more morphosyntactically integrated an ideophone is, the more likely it is to be at-issue. This is also logical as predicative or adjectival ideophones are clearly important for the integrity of an utterance and hence such ideophones would be required to be at least partially at-issue in order for the utterance to be interpretable. This relationship could also impact upon the iconicity of ideophones, with more at-issue ideophones generally appearing to be less iconic.

3.1.2 Demonstrated or quoted ideophones

As discussed in Section 2.3, Ebert et al. (2020) have shown through experimental work that the demonstrative SO shifts iconic co-speech gestures towards at-issueness and argue that demonstratives such as German SO and English like are dimension shifters, shifting not-at-issue content to the at-issue dimension. Similarly, Davidson (2015) has argued that the be like construction in English is quotative and provides an analysis of quotation as demonstration, where the speaker can iconically depict the demonstrated speech act or event. Henderson (2016) adapts and formalises the analysis given by Davidson (2015) to provide an account of ideophones in Tseltal, arguing that these are a specialised form of demonstration distinct from quotational-demonstration. According to Henderson, ideophones introduce an operator ideo-demo, which “[…] takes a linguistic expression […] and derives a relation between demonstrations and events” (p.673). This operator requires that there be an event which the ideophone represents and that there be a structural similarity between the demonstration event and the demonstrated event. Henderson (2016) gives an example with the Tseltal (Mayan) ideophone tsok’ which roughly depicts the sound of something frying in oil. A sentence such as ‘it goes «tsok’» in the lard’ would have truth conditions requiring there be an event where something frying in lard emitted such a sound and this sound was represented by the ideophone tsok’. While Henderson does not directly refer to the at-issue status of ideophones in his analysis, we argue that the inclusion of ideophones in the truth conditions require them to be interpreted as at-issue, as the sentences would be rendered uninterpretable if the ideophone demonstration were to be removed. As with morphosyntactic integration, it seems logical that quoted or demonstrated ideophones would be more at-issue, as the quotation or demonstration would form an integral part of the sentence they occur in. As such, we agree with Henderson’s analysis in so far as it suggests an at-issue interpretation of quoted or demonstrated ideophones and we would furthermore predict that ideophones accompanied by demonstratives are also examples of quotation-demonstration, with the demonstrative also shifting the ideophone towards at-issueness.

3.1.3 Alignment and timing

A further factor that may impact on the at-issue status of ideophones is that of the ideophone’s alignment or timing with respect to the main part of the utterance. As discussed in Section 2, a gradient approach to at-issueness (cf. Ebert 2017; Tonhauser et al. 2018) predicts that the more standalone a piece of information is, the more likely it is to be at-issue and experimental work from Syrett & Koev (2014) has provided evidence for this for appositives in sentence-final position. According to Dingemanse (2013), ideophones at clause edges generally have more prosodic foregrounding and expressive morphology compared to ideophones that are embedded in structures. These modifications would make the ideophone more prominent both prosodically and semantically and could therefore also indicate a shift towards at-issue status. As such, we predict that ideophones occurring sentence finally, or generally at clause edges, may be more at-issue than those occurring sentence medially. Crucially here we refer to the alignment of ideophones of the same syntactic class, for example, an adverbial ideophone occurring sentence finally would be more at-issue than an adverbial ideophone occurring sentence medially. This is therefore a distinct factor to that of the morphosyntactic integration of ideophones, although clearly there is an interaction between the two factors as more morphosyntactically integrated ideophones will likely have much less syntactic freedom and therefore will not be able to be manipulated in the same manner.

3.1.4 Internal vs. external enrichments

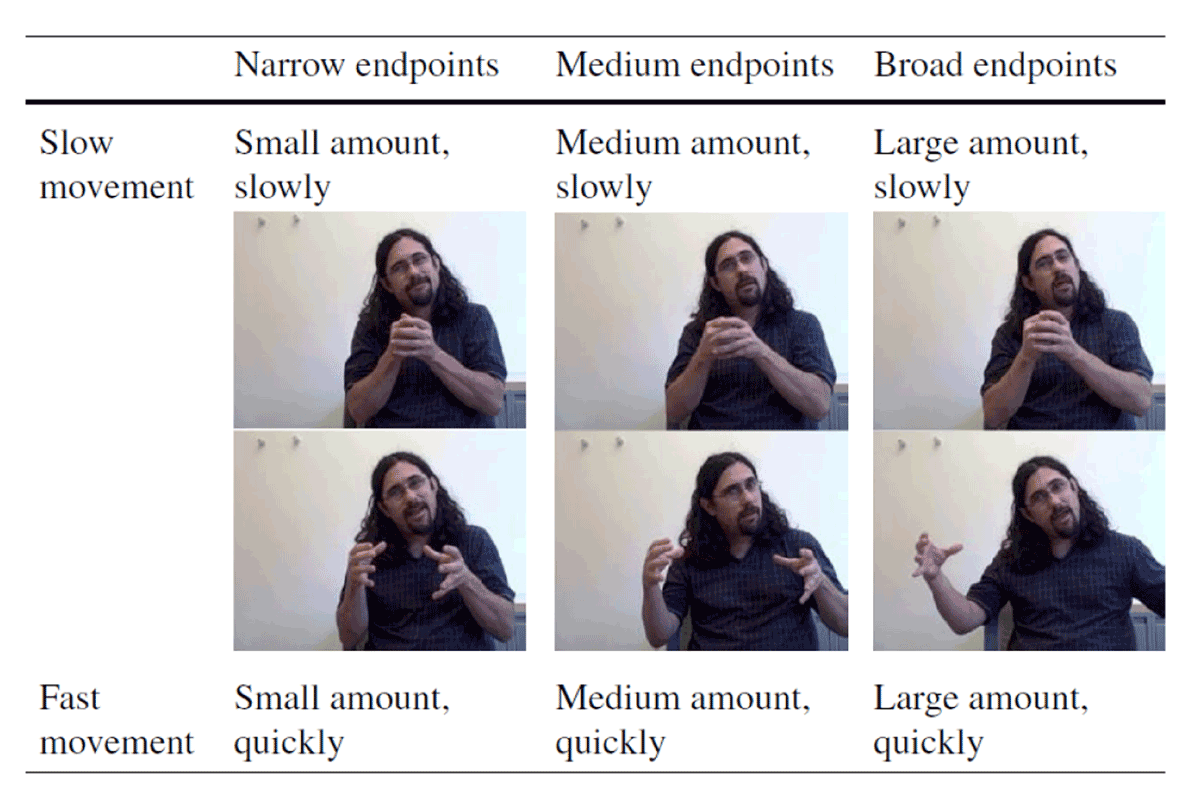

Both predicative and quotational-demonstrational uses of ideophones can be connected to the concept of external and internal iconic enrichments, as described by Schlenker (2018b). Schlenker argues that external enrichments can be eliminated without affecting the integrity of any at-issue information and therefore the acceptability of the utterance, while internal enrichments are integrated into the at-issue contribution and thus cannot be eliminated. According to Schlenker, internal enrichments can therefore be either at-issue or not at-issue and external enrichments are not at-issue. An example of an external enrichment would be co-speech gestures, whereas Schlenker (2018b) uses the sign GROW in American Sign Language (ASL) as an example of an internal enrichment. The sign can be iconically modified so that it describes different amounts and speeds of growth, depending on how far apart and how quickly the signer moves their hands. This can be seen in Figure 2.

Iconic modifications of GROW in ASL (Schlenker 2018b).

The iconic modification is therefore directly integrated with the at-issue contribution made by the sign GROW and cannot be eliminated without affecting the integrity of the sign. As such, Schlenker (2018b) argues that the iconic modification can be at-issue. Schlenker’s distinction between internal and external enrichments provides a good account for the more at-issue status of more morphosyntactically integrated and quotational-demonstrational uses of ideophones; they too are integrated into the at-issue contribution of the utterance and therefore, in contrast to Schlenker, we argue that they must be at least partially at-issue in order for the utterance to be interpretable. We propose an analysis of the at-issue status of such ideophones in which they are similar to mixed items, as described by authors such as Gutzmann (2011); McCready (2010) for expressives. We argue that, in cases where the ideophone is an internal enrichment and therefore necessarily makes some sort of at-issue contribution, the ideophone in fact contributes two types of meaning; one in the at-issue dimension, which allows the sentence to be interpreted, and one in the not-at-issue dimension, which contains the iconic information provided by the ideophone. In this respect, these ideophones are similar to expressives such as Köter ‘cur’ in German, which makes an at-issue contribution denoting a dog, as well as providing the not-at-issue implication that the speaker holds a negative attitude towards said dog.

This proposal also borrows from Kawahara (2020), who offers an account of Japanese ideophones as subjective predicates based on the analysis of subjective attitude verbs (SAVs) given by Kennedy & Willer (2016). Kawahara (2020) notes that ideophones such as karikari, sakusaku, paripari in Japanese share a core at-issue meaning referring to the crispiness of the described referent, however, speakers may disagree as to which ideophone best iconically depicts the crispiness of a given object. Kawahara (2020) argues that this is where the sound-symbolic nature of ideophones comes into play, as speakers may interpret one ideophone as being more appropriate for describing the crispiness of a pie based on how well its phonological form represents the layers of the pie breaking. Within this account, Japanese ideophones are sorted into sets of alternatives which share a core at-issue meaning component3 but differ with respect to their iconicity, which is pragmatically determined by speakers’ linguistic practices. For our analysis, we adopt Kawahara’s proposal of a core meaning for ideophones, which is separate to the ideophone’s iconic contribution. Hence in cases such as predicative or quoted ideophones, this core meaning is shifted towards at-issueness, rendering the sentence interpretable, while the ideophones continue to contribute not-at-issue, iconic information (see Section 3.2 for an adapted version of this proposal for a German ideophone). We also find it highly plausible that speakers interpret the iconicity of ideophones subjectively and have differing views about when which kinds of iconicity should be employed, however, we must leave further investigation of this to future research.

3.1.5 Crosslinguistic predictions for ideophones

Based on the observations discussed in this section, we can then make some general predictions for the at-issue status of ideophones crosslinguistically. Firstly, we would expect adverbial ideophones in languages where adverbials are fairly syntactically free to be not-at-issue. Certainly, the description of adverbial ideophones and their pragmatic behaviour in Siwu, given by Dingemanse (2017), supports this prediction. It is then also plausible that these ideophones could become more at-issue when they occur sentence finally rather than sentence medially. In addition, we may be able to make generalisations across languages about the at-issue status of ideophones based on their level of morphosyntactic integration and potentially their syntactic category. Less integrated ideophones, such as adverbials, would be expected to be less at-issue than more integrated ones such as predicative ideophones. Similarly, Dingemanse (2017) describes a typological continuum of morphosyntactic integration of ideophones across languages, with some, such as Somali, having a greater degree of morphosyntactic integration in their ideophones than Semai, whose ideophones are more expressive, but less integrated. Based on this continuum then, it may also be possible to predict that ideophones in more morphosyntactically integrated languages are more likely to be at-issue than those in less integrated languages. Finally, we would predict that ideophones accompanied by a quotative marker or a demonstrative would be more at-issue than ideophones without such markers, as the latter are “quoted” and form an integral part of the sentence, without which it would be infelicitous. Nevertheless, we would like to highlight that this is a preliminary attempt at making crosslinguistic predictions and there may be language specific conditions which impact upon ideophones’ at-issue status outside of these factors. For example, ideophones without the quotative to in Japanese can appear in two different constructions; the highly colloquial utterance edge construction, as in (8a) and the collocational construction, as in (8b), where an adverbial ideophone modifies its host verb:

- (8)

- a.

- Boon boon,

- idph

- hanabi-ga

- firework-nom

- agat-ta.

- rise-pst

- ‘Boom-boom, fireworks have been shot off.’

- b.

- Hanabi-ga

- firework-nom

- boon boon

- idph

- agat-ta.

- rise-pst

- ‘Fireworks have been shot off.’

While the utterance edge ideophone is presumably less at-issue than quotative ideophones in Japanese, the collocational ideophone actually forms a complex predicate with the host verb and therefore may be more at-issue than quotative uses of ideophones.4

Overall then, there appears to be a range of factors which could impact on ideophones’ at-issue status, all of which warrant further investigation, which will, in turn, allow us to establish general parameters for the at-issue status of ideophones crosslinguistically.5 In the final part of this section, however, we will return to ideophones in German and look at how these align with the predictions made above.

3.2 Ideophones in German

As previously noted, German does not share the range of ideophones seen in prototypical ideophonic languages such as Japanese, however, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that ideophones do form part of its linguistic system. Ideophones in German meet the definition given by Dingemanse (2019: p.16) as “[…] an open lexical class of marked words that depict sensory imagery”:

open lexical class Dingemanse (2019) argues that the size of the ideophone class in languages such as Japanese are evidence for describing ideophones as an open lexical class, as they are comparable to other open classes in these languages. German does not have this size of ideophone class, however, corpus work conducted by Ćwiek (submitted) has shown that ideophones are both idiosyncratically manipulated and created in German, as well as being created ad hoc, which Dingemanse (2019) also argues is evidence for ideophones being an open class.6

marked Ideophones in German are marked through their unusual morphophonology, such as reduplication, as can be seen in examples such as husch-husch and zack-zack. This distinguishes them from regular German lexical items.

words German ideophones are conventionalised words, whose meanings can be specified and listed, with allowances for variations due to subjective speaker interpretations.

depict German ideophones also depict rather than describe, as they represent an event through some sort of structural similarity. As an example, plitsch-platsch in (12) iconically represents the sounds of a frog’s wet feet moving on the steps of the stairs.

sensory imagery It could be argued that German ideophones are predominantly sound-symbolic or onomatopoeic, which are categories of ideophones that, as Nuckolls (2019) notes, have been traditionally viewed as marginal and simplistic. However, Nuckolls argues against this view, highlighting that phonetic research shows producing sound-symbolic utterances involves effort in terms of vocal manipulation and that neurolinguistic research has shown the importance of cross-modal relationships between sound and other sensory modalities. Indeed, Nuckolls (2019) highlights that Quichua speakers rarely perceive sound-imitative ideophones as only encoding sound. Similarly, experimental work by Ćwiek (submitted) highlights that many ideophones in German, which could be described as onomatopoeic, actually encode multisensory information. A key example is holterdiepolter, which generally refers to a situation with loud, chaotic movement, roughly equivalent to English helterskelter and which speakers therefore perceive as encoding information about both movement and sound.

In terms of their at-issue behaviour, there appear to be clear parallels between the ideophones described in the crosslinguistic literature and those in German.

Firstly, sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German demonstrate typical properties of ideophones as described by Dingemanse (2017), such as not being acceptable under negation, as in (9) and (10), which we argue are only acceptable as meta-linguistic utterances, and being restricted to contributing new information, as in (11), where it seems to be strange to use plitsch-platsch after already describing the wet, splashing sounds the frog makes.

- (9)

- ??Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- nicht

- not

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog does not go splish-splash up the stairs.’

- (10)

- ?Niemand

- nobody

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘Nobody goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

- (11)

- Der

- The

- Frosch

- frog

- ist

- is

- ganz

- completely

- nass

- wet

- und

- and

- macht

- makes

- laut

- loud

- platschende

- splashing

- Geräusche,

- noises

- als

- as

- er

- he

- voran

- forward

- springt.

- jumps

- #

- Er

- he

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog is completely wet and makes loud splashing noises as he jumps along. He goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

As previously discussed, these properties are indicative of not-at-issue content and this is shown for German sentence-medial, adverbial ideophones in (12), where it only seems to be possible to target the information provided by the ideophone with a discourse interrupting interjection, as in (12d).

- (12)

- a.

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

- b.

- Nein,

- No

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- runter.

- down

- ‘No, that’s not true. The frog goes down the stairs.’

- c.

- #Nein,

- No

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- doch

- but

- völlig

- completely

- geräuschlos

- silently

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘No, that’s not true. The frog goes up the stairs in complete silence.’

- d.

- Hey,

- hey

- warte

- wait

- mal.

- once

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- doch

- but

- völlig

- completely

- geräuschlos

- silently

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘Hey, wait a minute! The frog goes up the stairs in complete silence.’

Furthermore, greater morphosyntactic integration of ideophones in German leads to a reversal of these properties and a more at-issue interpretation, which also fits with crosslinguistic descriptions of the differing behaviour of ideophones in differing syntactic categories (cf. Dingemanse 2017; Dingemanse & Akita 2016; Kita 1997; 2001; Toratani 2018). For example, it seems to be perfectly acceptable to target the ideophones in (13) and (14) with a direct denial.

- (13)

- a.

- Es

- it

- macht

- makes

- plitsch-platsch!

- plitsch-platsch

- ‘It goes splish-splash!’

- b.

- Nein,

- No

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- Es

- it

- hört

- sounds

- sich

- refl

- ganz

- completely

- anders

- different

- an!

- on

- ‘No, that’s not true. It sounds completely different!’

- (14)

- a.

- Das

- that

- geht

- goes

- aber

- but

- holterdiepolter!

- holterdiepolter

- ‘That’s a bit helter-skelter!’

- b.

- Nein,

- no

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- Es

- it

- läuft

- runs

- doch

- but

- völlig

- completely

- geordnet

- orderly

- ab!

- off

- ‘No, that’s not true. It is completely orderly!’

Although the ideophones in (13) and (14) are clause final, graded at-issueness does not seem to be the cause of their at-issue interpretation.7 Instead, we argue that the verbs machen and gehen form predicates with the ideophones, resulting in a predicative ideophone construction, which causes the information they contribute to shift towards at-issue status and renders them an essential part of the main assertion.

Furthermore, ideophones in quotational-demonstration constructions also appear to be more at-issue in German. For example, ideophones accompanied by the demonstrative so also appear to be shifted towards at-issueness. For example, in (15), it seems possible to have an ideophone accompanied by a demonstrative in the focus of an answer, whereas this appears odd for ideophones not introduced by a demonstrative, as in (16).

- (15)

- a.

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- SO

- dem

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog goes like splish-splash up the stairs.’

- b.

- Wie

- How

- geht

- goes

- der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch?

- high

- ‘How does the frog go up the stairs?’

- c.

- So

- dem

- plitsch-platsch.

- plitsch-platsch

- ‘Like splish-splash.’

- (16)

- a.

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

- b.

- Wie

- How

- geht

- goes

- der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch?

- high

- ‘How does the frog go up the stairs?’

- c.

- #Plitsch-platsch.

- plitsch-platsch

- ‘Splish-splash.’

The alignment of ideophones in German with respect to the main utterance also seems to play a role. For example, plitsch-platsch appears to be more at-issue in (18), where it occurs sentence finally, than when it occurs sentence-medially in (17) and hence plitsch-platsch in (18) is more easily targeted by a direct denial.

- (17)

- a.

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

- b.

- #Nein,

- No

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- doch

- but

- völlig

- completely

- geräuschlos

- silently

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘No, that’s not true. The frog goes up the stairs in complete silence.’

- (18)

- a.

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch -

- high

- plitsch-platsch!

- plitsch-platsch

- ‘The frog goes up the stairs – splish-splash!’

- b.

- (?)

- Nein,

- no

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- doch

- but

- völlig

- completely

- geräuschlos

- silently

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘No, that’s not true. The frog goes up the stairs without a sound.’

Finally, certain adverbial ideophones in German also seem to be more at-issue despite the lack of any factors outlined above. Although ratzfatz also occurs sentence-medially in (19), as plitsch-platsch does in (12), it seems to be easier to directly address the information provided by ratzfatz.

- (19)

- a.

- Die

- the

- Bank

- bank

- hat

- has

- ratzfatz

- ratzfatz

- eine

- a

- Milliarde

- billion

- gewonnen.

- won

- ‘The bank earned a billion very quickly.’

- b.

- Nein,

- no

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- Es

- it

- war

- was

- nur

- only

- zehn

- ten

- Millionen.

- million

- ‘No, that’s not true. It was only ten million.’

- c.

- (?)

- Nein,

- no

- das

- that

- stimmt

- is right

- nicht.

- not

- So

- so

- schnell

- quickly

- ging

- went

- das

- that

- gar

- absolutely

- nicht.’

- not

- ‘No, that’s not true. It wasn’t that quick at all!’

A second observation is that the meaning of ratzfatz in (19) appears to be more easily specified than plitsch-platsch in (12); ratzfatz clearly refers to the speed at which the bank earned the money. The ideophone plitsch-platsch, however, appears to evoke sensory images of both how wet the frog is and how this wetness affects the noise it makes as it goes up the stairs. This is perhaps an explanation for why ratzfatz seems to be more at-issue than plitsch-platsch, as the latter expresses a much more nuanced concept which is difficult to target with a direct denial. In general, ideophones such as ratzfatz and ruckzuck appear to have more specifiable meanings and also appear to be more at-issue than ideophones such as plitsch-platsch or holterdiepolter, while still being iconic. As an initial analysis for these ideophones, we propose the same mixed item analysis as that discussed in Section 3.1.4 for predicative and quoted or demonstrated ideophones. Alongside a core (more) at-issue meaning, ideophones such as ratzfatz and ruckzuck also have an iconic component, which we argue is not at-issue. The crucial difference between these ideophones and other adverbial ideophones is that the core meaning of such ideophones is more conventionalised and as such can be interpreted as more at-issue even in adverbial structures when they are not necessarily an integral part of the sentence.

The question then remains as to how ratzfatz and ruckzuck have developed a more specifiable or conventionalised meaning in comparison to other ideophones. We propose that this could be due to a process of deideophonisation. As described by Dingemanse (2017) for Siwu, more frequently used ideophones are more likely to be used as normal words. One potential explanation for ratzfatz and ruckzuck then could be that their core meaning has become more conventionalised due to frequent use and hence the ideophones themselves are becoming more at-issue.8

In summary, the previous examples indicate that ideophones in German are able to contribute at-issue and not-at-issue information. While we do plan to conduct further research on all of the cases discussed above, the experimental work presented in the following section focuses on non-predicative, sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German, which we have claimed are not at-issue. Section 4 outlines the experiments we conducted on these ideophones, which provide evidence to support this claim.

4 Experiments

This section provides a description of the experiments we conducted on sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German. The experiments were based upon the experimental design of Experiment 1 in Ebert et al. (2020). They compared adverbial ideophones to ordinary adjectives in matching and mismatching contexts, with target sentences presented visually (Experiment 1) or auditorily (Experiment 2). Two pre-studies were conducted to ensure that appropriate adverbials were selected as equivalents to the ideophones, as it is not always immediately obvious which arbitrary linguistic items are appropriate counterparts (Diffloth, 1972; as cited by Dingemanse 2013). We will briefly discuss the pre-studies before moving on to discuss the main experiment.

4.1 Pre-study 1

The aim of this study was to gain information on how native speakers interpreted ideophones which were being considered for use in the main experiment. 18 ideophones were chosen and each embedded within a sentence. The pre-study was conducted using an informal questionnaire on Google Forms. A link to the questionnaire was circulated to native speakers among the staff and students within the Institute for Linguistics at Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main. The stimulus sentences were presented one after another on a separate page. For each item, participants were first asked whether they understood the sentence. If they affirmed, the stimulus sentence was presented again with the ideophone replaced by a gap. Participants inserted a close paraphrase for the ideophone into a blank space by means of the keyboard. If participants did not affirm, they continued with the next sentence. 27 participants in total completed the questionnaire. The data were analysed qualitatively, with identical or closely similar paraphrases being grouped together and used to inform the second pre-study.

4.2 Pre-study 2

The second pre-study was a forced choice questionnaire, which aimed to establish the best adverbial paraphrases of the ideophones, which would then be used in the main experiment. 23 ideophone target sentences were each paired with three candidate paraphrases of the ideophone. 18 of the ideophones were used in Pre-study 1. The three candidates were (a) the paraphrase originally envisaged in preparation of the main experiment, (b) the paraphrase most frequently produced in Pre-study 1, and (c) one of the remaining paraphrases produced in Pre-study 1 that matched the context constructed for the main experiment especially well (see Section 4.3). The candidates for the additional five ideophones not tested in Pre-study 1 were paraphrases that were selected on the basis of dictionary definitions and native speaker intuitions. The questionnaire was created using Sosci.9 It was run online on the platform Prolific.10 Participants were compensated with £3.75. For each item, participants were first asked whether they understood the sentence. If they affirmed, they were shown the three alternatives and asked to select the candidate they considered the closest paraphrase of the ideophone. If they did not affirm, they continued with the next item. 12 German native speakers completed the questionnaire. For all ideophones except one, a majority of participants opted for one of the candidates, ranging from 100% (12:0:0) to 42% (5:4:3). This candidate was selected for inclusion in the corresponding adverbial phrase in the main experiment. For the remaining ideophone, there was a tie between two candidates (5:5:0). We selected the one that we considered to better match the context constructed for the main experiment.

4.3 Experiment 1: Visual targets

4.3.1 Method

Participants. 42 native speakers of German completed Experiment 1. They were recruited via Prolific and compensated with £3.75.

Design and materials. The 2 × 2-design of the experiment crossed the two-level factors category (Adverbial vs. Ideophone) and match (Match vs. Mismatch), in close adaptation of the first experiment in Ebert et al. (2020). The design was implemented both within participants and items. The ideophones and the corresponding adverbials were selected based on the results of the pre-studies described in Sections 4.1 and 4.2. The variation of category was implemented in the target sentence as illustrated in (20).11

- (20)

- a.

- Ideophone

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

- b.

- Adverbial

- Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- mit

- with

- einem

- a

- platschenden

- splashing

- Geräusch

- noise

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog goes up the stairs with a splashing noise.’

Whether the target sentence instantiated a match or a mismatch was varied by means of the context preceding the target sentence, cf. (21). The continuation of the context in (21a) renders the target sentence a match for the context; the continuation in (21b) renders the target sentence a mismatch.

- (21)

- Da die Königstochter ihn nicht mitnimmt, muss der Frosch sich allein auf den Weg zum Schloss machen. Er ist immer noch ganz nass vom Teich, …

- ‘Because the king’s daughter did not take him with her, the frog must make his own way to the castle. He is still completely wet from the pond …’

- a.

- Match

- … so dass das Wasser auf den Pfad und auch noch auf die Treppe des Schlosses tropft, als er zur Königstochter hüpft.

- ‘… and the water drips off him on the path and on the stairs of the castle as he hops after the king’s daughter.’

- b.

- Mismatch

- … aber die Sonne brennt. Das Wasser von seinem Körper tropft noch auf den Pfad, aber als er die Treppe des Schlosses erreicht, hat die Sonne ihn fast ausgetrocknet und er ist so durstig wie noch nie in seinem Leben.

- ‘… but the sun is burning down. The water drips from his body on to the path, but as he reaches the stairs to the castle, the sun has almost completely dried him out and he is thirstier than he has ever been.’

Overall, there were a total of 20 experimental items, all of them instantiating each of the four conditions. 2 items tested in Pre-study 2 were selected to be used as practice items and 1 was excluded completely. The experimental items were distributed across four lists according to a Latin square design such that each list contained five items in each condition. 24 fillers were constructed in addition to the experimental items. Ten of the fillers (critical fillers) were used to decide whether a participant was included in the analyses or not (cf. Section 4.3.2).

Procedure. The data were gathered via the platform Prolific. Participants were informed that the upcoming short texts would be based on fairy tales. Sessions started with three practice trials (the two remaining ideophone items from Pre-study 2 and one adverbial example), followed by the 20 experimental trials intermixed with the 24 fillers, in randomized order for each participant. A trial started with the presentation of the context. When participants felt ready, they continued with the target sentence by pressing the space bar. In the next step, participants rated how well the target sentence matched the context on a visible scale from 1 = “does not match at all” to 5 = “matches perfectly.” Then the session proceeded with the next trial.

Hypothesis. We presume that the mismatch effect—the decrease in how well the target sentence is perceived to fit the context due to the mismatch—is stronger if the mismatch is induced by information relevant to the QUD, i.e. at-issue information, than by information not relevant to the QUD, i.e. not-at-issue information. As we view adverbials as at-issue information and ideophones as not-at-issue information we predicted an interaction of the two factors category and match to the effect that the difference between the match and the mismatch condition is significantly larger for adverbials than for ideophones.

4.3.2 Results

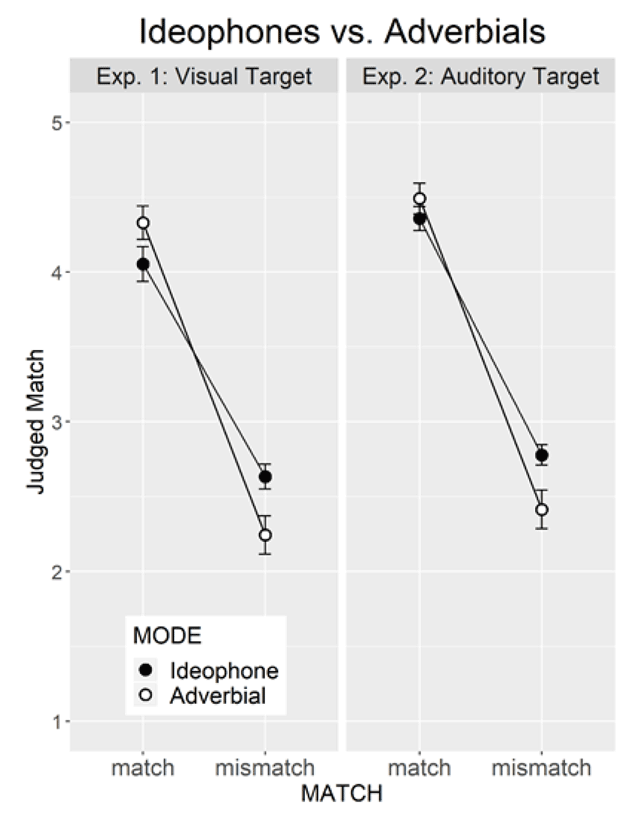

Participants were included in the analyses if their scores for the five matching critical fillers were more than two points higher than their scores for the five mismatching fillers. 40 of the 42 participants were included in the analyses on this criterion. The data of these 40 participants were subjected to analyses of variance with participant (F1) or item (F2) as random factor. The mean ratings for ideophones were 4.05 (matching) and 2.64 (mismatching), yielding a mismatch effect of 1.42. The mean ratings for adverbials were 4.33 (matching) and 2.25 (mismatching), yielding a mismatch effect of 2.09. Mean ratings are plotted in the left panel of Figure 3.

The analyses revealed a significant main effect of match [F1 (1,39) = 310.7, p < .001, η2 = .89; F2 (1,19) = 153.6, p < .001, η2 = .89] but not of category [F1 (1,39) = .35, p > .5, η2 = .009; F2 (1,19) = .35, p > .5, η2 = .02]. As predicted, the factors interacted significantly [F1 (1,39) = 16.1, p < .001, η2 = .29; F2 (1,19) = 7.7, p < .01, η2 = .29]. The left panel of Figure 3 corroborates that the mismatch effect is larger for adverbials than for ideophones. This is expected if ideophones convey not-at-issue information whereas adverbials convey at-issue information.

4.4 Experiment 2: Auditory targets

4.4.1 Method

Participants. 40 participants who did not participate in Experiment 1 completed Experiment 2. They were also recruited via Prolific and compensated with £3.75.

Design and materials. The design and the materials were identical to Experiment 1, except that the target sentences of the experimental items were articulated by a male speaker and recorded for auditory presentation. The final sentences of the critical fillers were treated the same and were presented auditorily, too.

Procedure. The procedure was the same as in Experiment 1, except that when participants felt ready after reading the context of an experimental item, they continued by listening to the recording of the target sentence instead of reading it. Participants started the recording by clicking on the play button of a small audio app displayed on the screen. They could listen to the recording as often as they liked. The procedure was the same for critical fillers. The remaining fillers were again presented entirely visually, i.e. in exactly the same way as in Experiment 1.

Hypothesis. We expected to replicate the significant interaction between category and match from Experiment 1.

4.4.2 Results

Participants had to meet the same criterion as in Experiment 1 to be included in the analyses. One participant failed to meet the criterion and thus only the data of the remaining 39 participants were subjected to analyses of variance, F1 and F2. The mean ratings for ideophones were 4.36 (matching) and 2.78 (mismatching), yielding a mismatch effect of 1.58. The mean ratings for adverbials were 4.49 (matching) and 2.42 (mismatching), yielding a mismatch effect of 2.08. Mean ratings are plotted in the right panel of Figure 3.

The analyses revealed a significant main effect of match [F1 (1,38) = 269.5, p < .001, η2 = .88; F2 (1,19) = 121.9, p < .001, η2 = .87] but not of category [F1 (1,38) = 3.2, p > .08, η2 =.08; F2 (1,19) = .65 p > .4 η2 = .03]. Importantly, the interaction of the two factors was again significant [F1 (1,38) = 16.7, p < .001, η2 = .31; F2 (1,19) = 4.7, p < .05, η2 = .20]. As is evident from Figure 3, right panel, the mismatch effect was stronger for spoken adverbials than for spoken ideophones.

5 Discussion

The results of both experiments support our claim that sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German can contribute not-at-issue information. The mismatch effect or the difference between sentence ratings in matching and mismatching contexts was significantly larger for the sentences containing ordinary adverbials than that of sentences containing ideophones. This indicates that participants’ judgements were more strongly impaired by mismatches induced by ordinary adverbials than those induced by ideophones, which supports the experimental hypothesis and indicates that such ideophones are not at-issue. Notably, ideophones were rated poorly compared to ordinary adverbials in matching conditions, which we attribute to the general markedness of ideophones.12 As ideophones are marked items, they will always be dispreferred by speakers and we would therefore expect ideophones to almost always be rated poorly in comparison to more standard linguistic items. Our hypothesis does not make predictions about how ideophones and ordinary adverbials behave in comparison to each other in matching conditions, but rather focuses on the mismatch effect for ideophones and adverbials separately, meaning that the specific ratings in the matching condition are not critical.

Overall, the data from these experiments supports our predictions around the at-issue status of sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German, namely that they are by default not-at-issue. This research is, however, only an initial step in understanding the pragmatic contribution of ideophones and there is much that warrants further investigation. Equally, the claims from this research must be properly scoped. While the evidence presented here makes a valuable contribution to research on ideophones and makes interesting predictions crosslinguistically, German is not a prototypical ideophonic language and the applications of this research in other languages must be carefully considered.

In the final part of this paper, we would like to turn to two questions which are particularly important in the context of understanding the meaning contributions of iconic enrichments; firstly, what exactly is the nature of ideophones’ not-at-issue contribution, i.e. are they conventional implicatures, supplements, presuppositions, and secondly, how comparable are ideophones to other iconic enrichments and in particular iconic gestures.

5.1 What is the pragmatic contribution of ideophones?

This paper has, up to this point, focused on discussing the at-issue status of ideophones and has only hinted towards what the exact contribution of not-at-issue ideophones could be. This distinction is important, as the characteristics previously discussed for ideophones are typical of not-at-issue content, in particular the ability to project from under semantic operators such as negation, but are not a diagnostic for identifying exactly what kind of not-at-issue content an ideophone is, for example, a conventional implicature or a presupposition. This section then addresses this question, discussing evidence indicating the exact contribution of not-at-issue ideophones. We limit ourselves to two possible forms of not-at-issue content, which have previously been discussed in detail as analyses of iconic enrichments and co-speech gestures in particular. The first follows Ebert et al. (2020)’s analysis and treats not-at-issue ideophones as having the same meaning contribution as appositives, hence as supplements. The second approach would be to treat not-at-issue ideophones as cosuppositions following Schlenker (2018a) and his handling of iconic co-speech gestures. As the two approaches make different predictions concerning whether an ideophone should contribute old or new information and how they should behave when embedded under negation and negative quantifiers, we can make predictions about which approach better applies to ideophones by observing their behaviour in the given situations.

In terms of whether they contribute old or new information, cosuppositions as a form of presupposition should contribute old information, as they should already be established in the common ground and must be true according to the conversational context. Supplements, on the other hand, usually contribute new information (cf. Potts 2005). One potential way to determine whether not-at-issue ideophones behave as supplements or cosuppositions would be to see if they contribute old or new information. As we saw in (11), repeated in (22), ideophones in German appear to provide new information. The use of plitsch-platsch after the description of the sounds the frog makes appears odd.

- (22)

- Der

- The

- Frosch

- frog

- ist

- is

- ganz

- completely

- nass

- wet

- und

- and

- macht

- makes

- laut

- loud

- platschende

- splashing

- Geräusche,

- noises

- als

- as

- er

- he

- voran

- forward

- springt.

- jumps

- #

- Er

- he

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog is completely wet and makes loud splashing noises as he jumps along. He goes splish-splash up the stairs.’

As previously noted, this intuition is also supported by crosslinguistic literature, where ideophones most commonly contribute new information (cf. Dingemanse 2017). However, as Schlenker (2018a) argues, cosuppositions can easily be locally accommodated, therefore it is difficult to empirically test whether an item contributes new information. Further consideration must be given to how to experimentally evaluate this property.13

We can also consider the behaviour of ideophones under negative quantifiers and negation. Under a supplemental analysis, ideophones would be expected to be marked when embedded under these structures, whereas under a cosuppositional analysis they should project and therefore be acceptable within these structures. Again, as we saw in (9) and (10), repeated in (23) and (24), when ideophones are embedded in such structures, they seem to only be acceptable as meta-linguistic utterances, for example, used in response to something previously asserted.

- (23)

- ??Der

- the

- Frosch

- frog

- geht

- goes

- nicht

- not

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘The frog does not go splish-splash up the stairs.’

- (24)

- ?Niemand

- nobody

- geht

- goes

- plitsch-platsch

- plitsch-platsch

- die

- the

- Treppe

- stairs

- hoch.

- high

- ‘Nobody goes splish-splash up the stairs.’