1 Introduction

Bantu languages are characterized as having a NOM/ACC alignment in agreement. In many of them, the specific agreement pattern is the following: one ф-probe agrees with the highest DPs in the clause (“subject agreement”, italicized in (1)), and another ф-probe agrees with a lower DP (“object agreement”, bolded in (1)).1

- (1)

- U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- w-a-yi-phek-a

- 1s-pst-9o-cook-fv

- i-nyama. Ndebele

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani cooked the meat.’

Despite being well known, this pattern in Bantu languages is not well understood. As I argue here, it cannot be derived from fine-tuning the positions of ф-probes in the clause or from case-discrimination in agreement. Focusing on Zimbabwean Ndebele, I propose that the NOM/ACC agreement pattern can be deduced from two existing hypotheses. The first hypothesis is that ф and epp are in some sense bundled together in this language family (Baker 2003; 2008; Collins 2004; Carstens 2005). The second states that relative timing of Agree and internal Merge may vary when the two operations are triggered by features of the same head (i.a. Bruening 2005; van Koppen 2005; Anand & Nevins 2006; Heck & Muller 2007; Georgi 2014). I specifically propose that the Ndebele NOM/ACC alignment is a consequence of movement preceding and bleeding agreement so that the object-agreement probe cannot reach the highest argument, even through cyclic expansion.

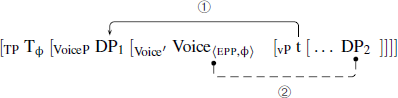

In section 2, I describe the agreement pattern in Ndebele. There are two ф-probes in the Ndebele clause: one in T and one in Voice. Importantly, both probes c-command all arguments in their base position. The instantiation of NOM/ACC alignment discussed in this paper is the inability of Voice to agree with the highest argument in the clause (DP1 in (2)).

- (2)

- The NOM/ACC phenomenon analyzed in this paper

The pattern in (2) is manifested in the inability of the thematically highest argument to control object agreement – whether the highest argument moves to Spec,TP (3-a) or stays in situ (3-b).

- (3)

- a.

- U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- w-a-(*m)-phek-a

- 1s-pst-(*1o)-cook-fv

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- Subject in Spec,TP

- ‘Thabani cooked meat.’

- b.

- Kw-a-(*m)-phek-a

- 15s-pst-(*1o)-cook-fv

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- Subject in situ

- ‘Thabani cooked meat.’

In section 3, I consider three possible sources for the NOM/ACC agreement pattern in Ndebele: i) fine-tuning the position of the object agreement probe, ii) case-discriminating agreement and iii) countercyclic probing by T before Voice. I then demonstrate that independently known properties of Bantu languages make it very difficult to pursue the first two types of analyses, and conclude that the countercyclic analysis is undesirable on theoretical grounds.

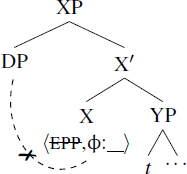

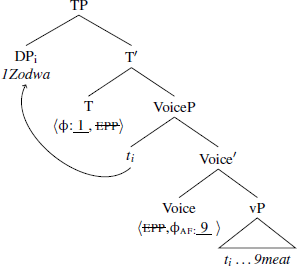

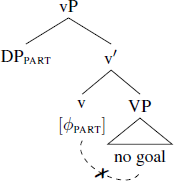

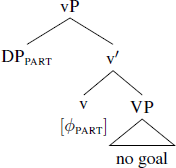

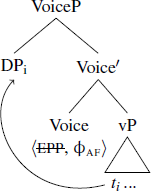

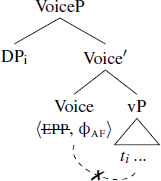

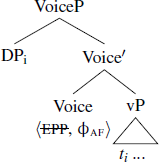

Section 4 develops the proposal, capitalizing on an existing hypothesis according to which ф-probes in Bantu languages obligatorily cooccur with epp on the same head. Thus, a ф probe in Voice entails an epp probe in Voice. By hypothesis, epp probes first, removing the highest DP from the search domain of the ф-probe in Voice, as shown in (4).

- (4)

The ф–epp bundling hypothesis explains why DP1 fails to control agreement on Voice even when it remains in situ. Assuming that VoiceP in Ndebele is phasal (see section 6.2 for evidence), movement out of it requires epp in Voice. For the subject to stay in situ, Voice must lack epp. The absence of epp entails the absence of ф, by the bundling parameter. Thus, when the subject is in situ, there is no ф-probe in Voice to begin with, hence no object agreement with in-situ subjects. This analysis is laid out in section 4.1, at the end of which I discuss its implications for the ф–epp bundling. In section 4.2, I propose an explanation of why cyclic expansion of probes cannot “undo” the NOM/ACC pattern by allowing the object-agreement probe to reach the subject in Spec,VoiceP in cases where there is no matching goal inside of Voice’s complement. In brief, the hypothesis is that probes may only expand to the root node. Movement bleeds probe expansion because it creates a new root node. This limits the search domain to the complement, giving rise to a rigid downward-Agree pattern, as opposed to a cyclic-Agree pattern.

In section 5, I discuss the implications of the proposed analysis for the connection between object agreement and object dislocation. Even though agreed-with objects must be dislocated in Ndebele, the object agreement probe and the object-dislocation probe are not located on the same head. The reason why the two operations cooccur is that the triggering probes (epp and ф) are relativized to the same feature (Antifocus, Zeller 2008; 2015). If an object bears that feature, it is a matching goal for both ф in Voice and an epp feature higher in the clause.

Section 6 further supports the proposed analysis by demonstrating that it derives three seemingly unrelated properties of Ndebele ф-agreement and A-movement: defective intervention effects in VSO clauses (6.1), the optionality of subject raising and agreement (6.2), and an object agreement asymmetry in passives of ditransitives (6.3). Section 7 concludes the paper and situates its findings in a crosslinguistic context.

2 The NOM/ACC agreement alignment in Ndebele

The core data in this paper come from Zimbabwean Ndebele (Bantu, Nguni group, S44), but many of the phenomena discussed here are very robust across the Bantu language family and have been discussed in the literature for related languages, such as Zulu (i.a. van der Spuy 1993; Buell 2005; Zeller 2006; 2008; 2012; Adams 2010; Halpert 2012; 2015), Xhosa (Carstens & Mletshe 2015), and others (see e.g. Diercks & Carstens to appear for an overview).

2.1 Background on Ndebele agreement and A-movement

Ndebele exhibits subject agreement and object agreement (5). Subject agreement is obligatory, while object agreement appears only when the object is discourse-given.2

- (5)

- a.

- U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- u-za-yi-phek-a

- 1s-fut-9o-cook-fv

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- subject and object agreement

- ‘Thabani will cook the meat.

- b.

- U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- u-za-pheka

- 1s-fut-cook-fv

- i-nyam-a.

- a-9meat

- only subject agreement

- ‘Thabani will cook meat.’

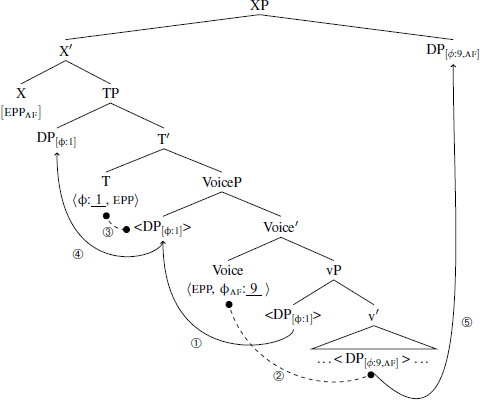

The object marker in southern Bantu languages is normally treated as a morpheme/head located outside the argument structure domain (i.a. Downing 1999a; 2001; Julien 2002; Sibanda 2004; Buell 2005; Zeller 2015; Halpert & Zeller 2015; Pietraszko 2016; Diercks 2022). There is no consensus as to the category of this head. Julien (2002) and Zeller (2015) refer to it simply as X0, Buell (2005) as AgrO, and yet other authors proposed that it is related to information structure (Buell 2008; Diercks 2022). What these proposals have in common is that the object marker is projected higher than all arguments. I propose to call this head Voice since, as I argue in this paper, it is the locus of the clause internal phase – a property often attributed to Voice. I further assume, following Zeller (2008; 2015), that the object agreement probe is relativized to DPs bearing the Antifocus feature (af) borne by discourse-given DPs. The subject agreement probe, located on T, is not relativized in this way.3 As shown in (6), the agreeing subject undergoes A-movement to Spec,TP. The verb in Ndebele moves out of the vP (Pietraszko 2017b). I assume that the landing site of verb movement is T.4

- (6)

- Derivation of (5-a) (to be completed in (8))

Another relevant aspect of Ndebele clause structure is the fact that agreed-with objects undergo dislocation, to the right (7-a) or to the left (7-b) (Pietraszko, 2021). In this paper, I only discuss right-dislocation, which can be diagnosed by the relative order of the object and a post-verbal adverb, such as kahle ‘well’ (Pietraszko, 2021). As we see in (7-a), agreed-with objects must appear outside of vP.

- (7)

- a.

- UThabani

- 1Thabani

- u-∅-yi-phek-a

- 1s-cnj-9o-cook-fv

- [vP tV

- {*inyama} ]

- 9meat

- kahle

- well

- {✓inyama}.

- 9meat

- ‘Thabani cooks the meat well.’

- b.

- Inyamai

- 9meat

- uThabani

- 1Thabani

- u-∅-yi-phek-a

- 1s-cnj-9o-cook-fv

- [vP tV ti ]

- kahle.

- well

- ‘The meat, Thabani cooks it well.

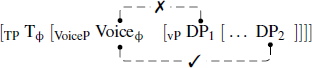

The derivation in (6) is thus not complete: it should involve a final step of object movement to the right periphery, shown in (8). I take this position to be a rightward specifier of a phrase above TP, whose head X triggers movement of DPs with the af feature.

- (8)

- Complete derivation of (5-a)

Since this paper is concerned with phenomena taking place inside TP, i.e. before object dislocation applies, I will represent objects as located in their base positions even when they control object agreement, keeping in mind that they undergo further movement once TP is merged with X. I return to the discussion of object dislocation in section 5.5

2.2 The NOM/ACC agreement pattern in Ndebele

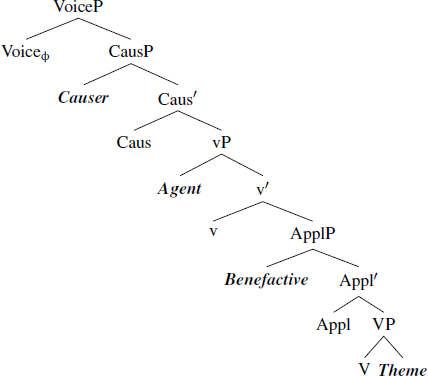

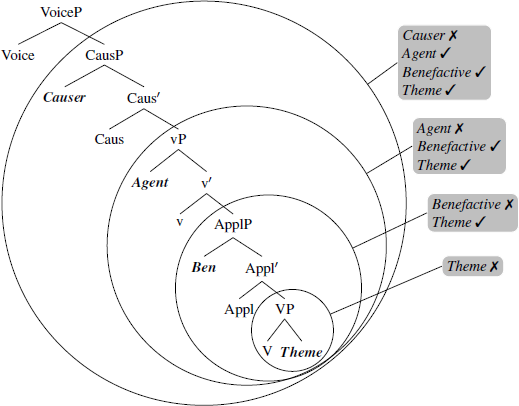

Turning to the core data, subject agreement in Ndebele is typically6 controlled by the highest DP in the argument structure domain, irrespective of where that DP is generated. Building on Halpert’s (2015) analysis of Zulu, I assume that the argument structure domain in Ndebele has the syntax given in (9).7

- (9)

- The assumed syntax of the argument structure domain

I use the term canonical subject to refer to the thematically highest DP in a given clause. The agreeing subject may be a Causer (10), an Agent (11), a Benefactive (12), or a Theme (13).

- (10)

- U-Zodwa

- a-1Zodwa

- w-a-phek-is-a

- 1s-pst-cook-caus-fv

- a-bantwana.

- a-2child

- ‘Zodwa made the children cook.’ Causer subject

- (11)

- U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- w-a-phek-a.

- 1s-pst-cook-fv

- ‘Thabani cooked.’ Agent subject

- (12)

- A-bantwana

- a-2child

- b-a-phek-el-w-a.

- 2s-pst-cook-app-psv-fv

- ‘The children were cooked for. Benefactive subject

- (13)

- I-sihlahla

- a-7tree

- s-a-w-a.

- 7s-pst-fall-fv

- ‘The tree fell.’ Theme subject

As previously observed (Zeller 2015; Diercks 2022), the structure in (9) creates a countercyclicity problem: the canonical subject appears to move out of VoiceP before Voice starts probing. Otherwise, the ф-probe in Voice should be able to Agree with the canonical subject giving rise to the subject controlling agreement on both Voice and T. This is not possible, irrespective of where the subject is base-generated (14)–(17).

- (14)

- *U-Zodwa

- a-1Zodwa

- w-a-m-phek-is-a

- 1s-pst-1o-cook-caus-fv

- a-bantwana.

- a-2child

- ‘Zodwa made the children cook.’ Causer

- (15)

- *U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- w-a-m-phek-a.

- 1s-pst-1o-cook-fv

- ‘Thabani cooked.’ Agent

- (16)

- *A-bantwana

- a-2child

- b-a-ba-phek-el-w-a.

- 2s-pst-2o-cook-app-psv-fv

- ‘The children were cooked for.’ Benefactive

- (17)

- *I-sihlahla

- a-7tree

- s-a-si-w-a.

- 7s-pst-7o-fall-fv

- ‘The tree fell.’ Theme

The canonical subject cannot control agreement on Voice even when it remains in situ (18)-(19).8 Note that an in-situ subject cannot control agreement on T either (class 15 is default/lack of agreement). I return to agreement on T in sections 4 and 6.2.

- (18)

- a.

- Kw-a-phek-a

- 15s-pst-cook-fv

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- i-suphu.

- a-9soup

- ‘Thabani cooked soup’ Agent

- b.

- *Kw-a-m-phek-a

- 15s-pst-1o-cook-fv

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- i-suphu.

- a-9soup

- ‘Thabani cooked soup’

- (19)

- a.

- Kw-a-w-a

- 15s-pst-fall-fv

- i-sihlahla.

- a-7tree

- ‘A tree fell.’ Theme

- b.

- *Kw-a-si-w-a

- 15s-pst-7o-fall-fv

- i-sihlahla.

- a-7tree

- ‘A tree fell.’

It is worth noting here that in-situ subjects in Ndebele are typically focused. Object agreement, on the other hand, targets non-focused DPs. Therefore, a possible explanation of (18-b) and (19-b) is in terms of discourse properties of in-situ subjects. This explanation would not, however, extend to the facts in (14)–(17), where the subject is not focused. Moreover, it would predict that agreement on Voice could be controlled by the object in (18). As discussed in section 6.1, this is an incorrect prediction. Therefore, a different account is needed.

This pattern of agreement is a clear example of the NOM/ACC argument alignment: the highest argument in the clause is treated uniformly by the agreement system, irrespective of its thematic status. However, given the structure in (6), it is not clear how this pattern arises, i.e. why the probe in Voice ignores the closest DP in its c-command domain. Three types of analyses come to mind. The first would be to hypothesize that the object agreement probe is, in fact, not in Voice, but rather in a position from which it does not c-command the canonical subject. Second, this alignment might be due to an interaction between agreement and case that prevents Voice from agreeing with the subject. And third, the pattern could follow from the timing of subject movement and object agreement. In the next section, I entertain each possibility and discuss the challenges they face. Then, in section 4, I develop a version of the last type of analysis, arguing that the NOM/ACC agreement alignment in Ndebele is due to the interaction between subject movement and object agreement. I demonstrate that this interaction is, in fact, a consequence of an independently motivated parameter for Bantu languages, according to which ф-probes must cooccur with an epp feature on the same head (Baker 2003; 2008; Collins 2004; Carstens 2005).

3 Possible derivations of the NOM/ACC pattern in Ndebele

In this section, I present and reject three different ways of deriving the NOM/ACC agreement pattern described in the previous section: i) finding a position for the object-agreement probe that would derive of this pattern simply from probe-goal locality (section 3.1), ii) case-discrimination in agreement (section 3.2), and iii) countercyclic probing by T before Voice (section 3.3).

3.1 Hypothesis 1: Fine-tuning the position of the object agreement probe

Recall from the previous section that the standard analysis of the object marker in Ndebele and closely related languages treats this morpheme as located outside of the argument structure domain (Downing 1999a; 2001; Julien 2002; Sibanda 2004; Buell 2005; Halpert & Zeller 2015; Zeller 2015; Pietraszko 2016; Diercks 2022). Different authors have given different reasons for this analysis, including how OM-ing relates to information structure (Buell 2008; Zeller 2015; Diercks 2022), head movement (Julien 2002), and morphophonological domains in the verb word (Barrett-Keach 1986; Hyman 1993; Mchombo 1993; Myers 1998; Downing 1999b; 2001; Hyman & Mtenje 1999; Julien 2002; Sibanda 2004; Pietraszko 2016). The latter type of evidence is especially compelling. Many authors have shown that the object marker is outside of the domain that contains argument-introducing morphology (so called extensions) and the Final Vowel – a morpheme that fusionally realizes tense, mood and polarity. The structure in (20) has been argued for extensively in the literature cited above, and is the standard analysis of verb morphology in Bantu languages. See Downing (2001) and Pietraszko (2016) for evidence for this structure specifically in Ndebele.9

- (20)

- Inflection [Macrostem OM [Stem Root + (extensions) + FV]]

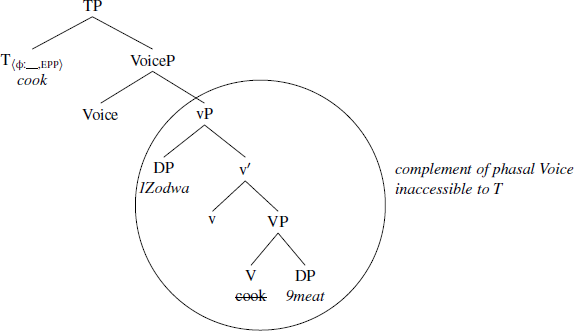

Despite being well-motivated, the assumption that the object agreement probe is outside of the argument structure domain (here, in Voice) creates the puzzle laid out in the previous section: The object agreement probe in Voice is expected to agree with the canonical subject. In this section, I explore (and reject) the possibility that locating the probe lower in the structure might solve this problem and thus derive the NOM/ACC agreement alignment discussed above.

Locating the object agreement probe on little v, as has been proposed for many other languages,10 derives the inability of Agents to control object agreement. Assuming downward Agree (Chomsky 2000; 2001; Preminger 2013; Polinsky & Preminger 2015; 2019; Diercks et al. 2020; Rudnev 2020, contra Adger 2003; Merchant 2006; 2011; Baker 2008; Wurmbrand 2011; Zeijlstra 2012; Bjorkman & Zeijlstra 2019), Agents cannot control agreement on v because they are not c-commanded by it. As should be clear, this account does not extend to other arguments. For instance, it incorrectly predicts agreement between v and the sole argument of unaccusatives, contrary to fact ((17), (19)).11 Similarly, in passives of applicatives, we would expect v to agree with the applied argument, again incorrectly (16).

Another incorrect prediction of this account is that Agents should always be unable to control object agreement. This is, however, not true. An Agent is unable to control object agreement only when it is the highest argument. In causativized agentive verbs, where there is a Causer above the Agent, the Agent can in fact control object agreement. Consider a causativized transitive verb, with an Agent as the indirect object (IO) and a Theme as the direct object (DO). First, note that both the Agent and the Theme can control object agreement in such a construction:

- (21)

- a.

- Ngi-∅-

-phek-is-a

-phek-is-a - 1sg.s-cnj-2o-cook-caus-fv

- [vP tV

- i-nyama ]

- a-9meat

- a-bantwanai.

- a-2child

- ‘I’m making the children cook meat.’

- b.

- Ngi-∅-

-phek-is-a

-phek-is-a - 1sg.s-cnj-9o-cook-caus-fv

- [vP

- tV

- a-bantwana

- a-2child

-

]

] - inyamaj.

- a-9meat

- ‘I’m making children cook the meat.’

As argued by Zeller (2015), the absence of minimality observed in (12-b) is only apparent: since the probe is looking specifically for a DP with the af feature, the DO (‘meat’) is the most local matching goal whenever the IO (‘children’) has no such feature (recall that dislocation takes place after object agreement). The interpretation corroborates this analysis: the IO in (21-b) is an indefinite DP (not discourse-given). That object agreement does in fact obey minimality becomes clear when both objects have af, and thus are both viable goals for object agreement. The af feature of the objects is diagnosed by their dislocated position, which in turn is diagnosed by placing both objects after an adverb, as in (22). In this scenario, only the indirect object may be agreed with, revealing that it is a closer goal to the object-agreement probe than the direct object.12 Note that the relative order of the dislocated objects does not play a role in (22-b).

- (22)

- a.

- Ngi-ya-

-phek-is-a

-phek-is-a - 1sg.s-dsj-2o-cook-caus-fv

- [vP

- tV

tj ]

tj ] - kahle

- well

- a-bantwanai

- a-2child

- i-nyamaj.

- a-9meat

- ‘I’m making the children cook the meat well.’

- b.

- *Ngi-ya-

-phek-is-a

-phek-is-a - 1sg.s-dsj-9o-cook-caus-fv

- [vP tV ti

]

] - kahle

- well

- {i-nyamaj}

- a-9meat

- a-bantwanai

- a-2child

- {i-nyamaj}.

- a-9meat

- ‘I’m making the children cook the meat well.’

Next, observe that there can only be one object agreement morpheme on the verb (23).

- (23)

- *Ngi-ya-

-phek-is-a

-phek-is-a - 1sg.s-dsj-{9o}-2o-{9o}-cook-app-fv

- [vP tV

]

] - kahle

- well

- a-bantwanai

- a-2child

- i-nyamaj.

- a-9meat

- ‘I’m making the children cook the meat well.’

Together, these facts show that there is only one object agreement probe in the Ndebele clause and that it can access the Agent of the verb cook (here, the indirect object). In light of this conclusion, the inability of the Agent in (24) to control object agreement cannot be explained by its inaccessibility to the object agreement probe.

- (24)

- a.

- A-bantwana

- a-2child

- b-a-(*ba)-phek-a

- 2s-pst-(*2o)-cook-fv

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Children cooked meat.’

- b.

- Kw-a-(*ba)-phek-a

- 15s-pst-(*2o)-cook-fv

- a-bantwana

- a-2child

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Children cooked meat.’

The same argument can be made from applied objects. An applied argument in an active clause (with a higher Agent) can control object agreement. But when the Agent is demoted under passivization, the same applied argument can no longer control agreement on Voice. What these facts show is not only that the probe is not in v, but more generally, that there is no single head to which we can fine-tune the position of this probe that would derive its inability to find the highest argument.13

3.2 Hypothesis 2: The NOM/ACC alignment is due to case-discrimination in agreement

Let us turn to another possibility, which links agreement with case. It has been claimed for a number of languages that ф-agreement may be case-discriminating. For instance, Dative and Genitive DPs cannot control ф-agreement in many languages. A known example comes from Icelandic, in which Dative subjects do not control agreement on T (25).

- (25)

- Þeim

- they.

- var

- be.pst.

- hjálpað

- helped

- ‘They were helped.’ (Icelandic, Holmberg & Hróarsdóttir 2003: 998)

Similarly, Genitive subjects in Slavic languages like Russian and Polish cannot control subject agreement. The Polish example below shows the so called Genitive of Negation replacing Nominative marking on the subject in a negative clause (26).14

- (26)

- a.

- Oni

- they.

- byli

- be.pst.

- w

- at

- domu. NOM → agreement

- home

- ‘They were at home.’

- b.

- Ich

- they.

- nie

- not

- było

- be.pst.

- w

- at

- domu. GEN → no (default) agreement

- home

- ‘They weren’t at home.’ (Polish)

What would it take for the agreement pattern in Ndebele to be explained in terms of case discrimination? The language would have to have a case system that assigns the same case to any DP that’s base-generated in the highest position in the clause. Let us call that case Nominative. The ф-probe in Voice (but crucially, not the one in T) would have to discriminate against this case (27).

- (27)

- [TP Tф [VoiceP Voiceф[-NOM] [vP DPNOM … ]]]

In the configuration above, ф in Voice probes first but, since it discriminates against Nominative DPs, it is not able to target the highest DP in the vP.

As straightforward as it may initially seem, there are two problems with this solution. First, known instances of case-discriminating agreement are ones where the probe is specified to look for a DP with a specific case (on the assumption that the terms ‘nominative’ and ‘absolutive’ refer to a specific case feature), or for a DP that is altogether caseless (on the assumption that ‘nominative’ and ‘absolutive’ amount to caselessness; Bittner & Hale 1996; Bobaljik 2008; McFadden & Sundaresan 2011; Kornfilt & Preminger 2015). I am not aware of instances of case-discrimination against one particular case marking. This would have to be implemented in one of two ways. One way would be to encode probe relativization as a disjunctive list (e.g. ACC ∨ DAT ∨ INST …), which would include all case features present in the language except NOM (recall that object agreement in Ndebele can target any DP except for the highest one). The other way would be to specify case features on DPs negatively (e.g. state ‘accusative’ as [–NOM, –DAT, –INSTR …]) and have the probe be relativized to [–NOM], as is done in (27). Neither implementation is explanatory, but without one of them, this type of case-discrimination is not statable.

A different possibility is to adopt the parametric setting that Bobaljik (2008) proposes for languages like Nepali. Based on the Marantzian (1991) case hierarchy: unmarked > dependent > lexical/inherent, a language can be parametrized to exhibit agreement with i) all case types, ii) only the first two, iii) only the first one or iv) none. If the cutoff for agreement is between dependent and lexical/inherent case and the language happens to have only one lexical/inherent case, we incidentally arrive at an agreement system which discriminates against a single case (the lexical/inherent case). Applying this to the issue at hand would mean that the highest DP in Ndebele has lexical/inherent case, and no other DPs bear that case. This is extremely unlikely. Recall that the set of DPs invisible to object agreement cannot be defined by their lexical/thematic properties. The only defining factor is structural: these DPs are simply the highest DP in their respective argument-structure domains. Suppose now that Ndebele has no inherent/lexical case and the cutoff for agreement is between unmarked and dependent case. The highest DP could then be invisible to the probe by virtue of having dependent-case. This, however, is not a possibility either, since the ban on object agreement with the highest DP is observed in intransitive clauses, where no dependent case could be assigned. The only other option that the hierarchy gives us is to ban agreement with all DPs, which is naturally incorrect. Finally, the highest DP is not generally immune to agreement – it controls agreement on T. This means that there can be no language-wide parameter banning agreement with it.

The second issue with the case-discrimination hypothesis is its deep incompatibility with what is known about case in Bantu languages, which have neither morphological case marking nor the kind of restrictions on DP distribution that have long been associated with abstract case in other languages (“Vergnaud licensing”; Vergnaud 1977; Chomsky & Lasnik 1977; Chomsky 1981). This has led some to argue that case is absent in this language family altogether (Harford Perez 1985; Diercks 2012; Carstens & Diercks 2013) or that it is rare (van der Wal 2015; Sheehan & van der Wal 2018). Others have proposed that Bantu languages do have case, but the system is quite different from that of NOM/ACC Indo-European languages (Carstens 2001; 2011; Baker 2003; 2008; Halpert 2012; 2015; Carstens & Mletshe 2015; Schneider-Zioga 2019; Pietraszko 2021). To the best of my knowledge, no existing theory of case in closely related languages is able to explain the NOM/ACC alignment in terms of case-discrimination.

In Halpert’s (2012; 2015) theory of case in Zulu, case is morphologically reflected as the presence or absence of the so called augment vowel on nominals (glossed as a here). Augmentless DPs have a much more limited distribution than DPs with an augment. Like in Zulu, augmentless DPs in Ndebele can appear e.g. as in-situ subjects in negative sentences. When possible, augment drop is typically optional (28).

- (28)

- A-ku-phek-i

- neg-15s-cook-neg

- (u)-Zodwa.

- (a)-1Zodwa

- ‘Zodwa didn’t cook’

According to Halpert, Zulu has a two-case system. Structural case, licensed by a head between T and Voice, is exponed by the absence of an augment. DPs with an augment bear inherent case assigned by the augment itself. If agreement on Voice is case-discriminating, it could target either augmented DPs or augmentless DPs. This seems in initially plausible since, in general, only augmented DPs can control object agreement (29).

- (29)

- a.

- A-ngi-(*m)-bon-i

- neg-1sg.s-(*1o)-see-neg

- Zodwa

- 1Zodwa

- ‘I don’t see Zodwa’

- b.

- A-ngi-(m)-bon-i

- neg-1sg.s-1o-see-neg

- u-Zodwa

- a-1Zodwa

- ‘I don’t see Zodwa’

However, the highest DP cannot control agreement on Voice irrespective of the presence of an augment (30).

- (30)

- a.

- A-ku-(*m)-phek-i

- neg-15s-(*1o)-cook-neg

- Zodwa.

- 1Zodwa

- ‘Zodwa didn’t cook’

- b.

- A-ku-(*m)-phek-i

- neg-15s-(*1o)-cook-neg

- u-Zodwa.

- a-1Zodwa

- ‘Zodwa didn’t cook.’

If Halpert’s theory is the correct theory of case in Ndebele (see Pietraszko 2021 for an argument that it is), the contrast between (29-b) and (30-b) cannot be due to case.

Analyzing Xhosa, another closely related language, Carstens & Mletshe (2015) argue that in-situ subjects in this language may bear a number of different cases: i) structural, ii) focus-related lexical case or iii) theta-related inherent case.

- (31)

- Different cases borne by in-situ subjects in Xhosa (Carstens & Mletshe 2015)

- a.

- [vP AgentStructural Case ]

- b.

- [vP AgentFocus Case Theme ]

- c.

- [vP ThemeStructural Case ]

- d.

- [vP ExperiencerInherent Case ]

In such a case system, Voice would have to discriminate against all the cases in (31), including structural case. This incorrectly rules out agreement with objects of SVO clauses which, as Carstens & Mletshe propose, bear structural case as well. Moreover, there is evidence that Voice does not discriminate against the case borne by Experiencer arguments in Ndebele. First, Experiencer subjects, like all other subjects, can be either preverbal or postverbal. As with all other subjects, they cannot control agreement on Voice, whether moved to Spec,TP (32-a) or left in situ (32-b).

- (32)

- a.

- U-Zodwa

- a-1Zodwa

- u-(*m)-dan-ile.

- 1s-1o-sad-pst.dsj

- ‘Zodwa was sad.’

- b.

- Ku-(*m)-dan-e

- 15s-1o-sad-pst.cnj

- u-Zodwa.

- a-1Zodwa

- ‘Zodwa was sad.’

However, the same Experiencer argument can control agreement on Voice if it is not the highest DP in the clause. This is the case when the verb ‘be sad’ (the same verb used in (32)) is causativized, which results in the presence of a higher argument, the Causer:

- (33)

- Ba-m-dan-is-e

- 2s-1o-sad-caus-pst.cnj

- u-Zodwa.

- a-1Zodwa

- ‘They made Zodwa sad.’

Thus, even if Experiencers bear a special inherent case, this case cannot be the reason why Voice cannot agree with it in (32).

Finally, many authors have independently argued that ф-agreement in Bantu languages is insensitive to case, irrespective of their view on the case system itself (i.a. Ndayiragije 1999; Carstens 2001; 2011; Baker 2003; 2008; Halpert 2012; 2015; Carstens & Mletshe 2015). Given all of this, an analysis of the puzzle at hand in terms of case-discrimination seems rather hopeless.

3.3 Hypothesis 3: NOM/ACC alignment is due to the timing of agreement and movement

A third way to derive the NOM/ACC agreement alignment in Ndebele is by manipulating the timing of subject movement and object agreement. In particular, the subject would have to move out of the c-command domain of the object agreement probe before the probe initiates its operation.

It is typically assumed that the first step of A-movement that targets the subject is triggered by epp in T. Object agreement is triggered by a lower head, such as Voice. These assumptions, when combined, entail that the timing of operations must be countercyclic: T must probe before Voice (34).

- (34)

Analyzing the same facts in Zulu, Zeller (2015) proposes the following principle to enforce the desired order of operations (35).

- (35)

- The “T Always Probes First” principle (Zeller 2015)

- The first vP-external probe-goal relation in a derivation must involve the uninterpretable features of T.

As should be clear, this principle is a stipulation and should be avoided if possible, particularly if we want to maintain the restrictiveness brought about by assuming cyclicity.

As it turns out, it is possible to avoid (35). Note that the countercyclicity problem would not arise if the subject movement probe and the object agreement probe were both located in T. Such a derivation would be cyclic in the sense that no features of a higher head would probe before the features of a lower head. This type of analysis has been proposed to account for (apparent) countercylic effects in Icelandic experiencer constructions (Holmberg & Hróarsdóttir 2003) and for V-Stranding VP Ellipsis (Sailor 2018). However, there is good evidence that the object agreement probe is not located in T in Ndebele. In compound tenses, object agreement must be realized on the participle, while T is affixed to an auxiliary (36).

- (36)

- Ngi-za-{*yi}-be

- 1sg.s-fut-{*9o}-aux

- ngi-sa-{yi✓}-phek-a.

- 1sg.s-prog-{9o✓}-cook-fv

- ‘I will still be cooking it.’

There is another way for the subject movement feature and the object agreement probe to appear on the same head: both could be in Voice. This, in turn, would mean that the first step of A-movement subjects undergo in this language is short, middlefield movement to Spec,VoiceP. In the remainder of this paper, I argue that this is indeed the case in Ndebele. In the next section, I lay out the details of the analysis and demonstrate how it derives the basic pattern of agreement in Ndebele. In section 6, I provide further evidence for this analysis by showing that it offers a straightforward explanation for three other puzzles: i) defective intervention effects in VSO clauses (6.1), ii) the optionality of movement to Spec,TP, (6.2), and iii) an object agreement asymmetry found in passives (6.3).

4 Proposal: movement bleeding agreement

I propose that the NOM/ACC alignment in agreement in Ndebele is a consequence of parametric bundling of ф with epp and an ordering of Merge before Agree in Voice. As detailed in section 4.1, a ф-probe in Voice entails an epp feature in Voice, which removes highest DP from the c-command domain of the object-agreement probe. The inability of an in-situ subject to control object agreement is also derived from the bundling parameter: the subject remains in-situ only when Voice lacks epp and, by the bundling parameter, the absence of epp entails the absence of ф. Thus, there is no object-agreement probe in VS orders. In section 4.2, I offer an explanation of why the ф-probe in Voice does not undergo cyclic expansion and why we observe a rigid downward-Agree pattern, instead of a cyclic-Agree pattern.

4.1 The analysis and derivation of core data

A well-known property of Bantu languages is the interdependence of agreement and movement. It is manifested robustly in the realm of canonical subjects, which must raise to Spec,TP in order to control agreement on T (37-a). In-situ subjects cannot control agreement (37-b).

- (37)

- a.

- U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- u-phek-a

- 1s-cook-fv

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani cooks meat’

- b.

- *U-phek-a

- 1s-cook-fv

- [vP

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- i-nyama].

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani cooks meat’

When the subject stays in situ, T surfaces with class 15 agreement (38-a). Default agreement is not possible if the subject raises to Spec,TP (38-b).

- (38)

- a.

- Ku-phek-a

- 15s-cook-fv

- [vP

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- i-nyama].

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani cooks meat’

- b.

- *U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- ku-phek-a

- 15s-cook-fv

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani cooks meat’

This one-to-one correspondence between movement and agreement is almost exceptionless in Bantu languages and it underlies proposals that link agreement with movement in this language family.15 Baker (2008) explains their cooccurrence by proposing that Agree is upward in Bantu languages, which effectively requires DPs to move before they can control agreement. A different implementation is found in Carstens (2005), who proposes that ф-probes in Bantu languages have an epp subfeature, notated as фepp. Here, I follow Baker (2003) and Collins (2004), who implement to cooccurrence of movement and agreement as parametric bundling of ф and epp:

- (39)

- The ф → epp Parameter

- A ф-probe must cooccur with an epp feature on the same head.

According to (39), whenever we see ф, there is also an epp feature. Where there is no epp, there is no ф. (It is important to note that this is a one-way implication – the epp feature can occur on its own, i.e. without ф.)

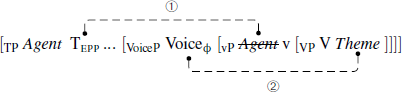

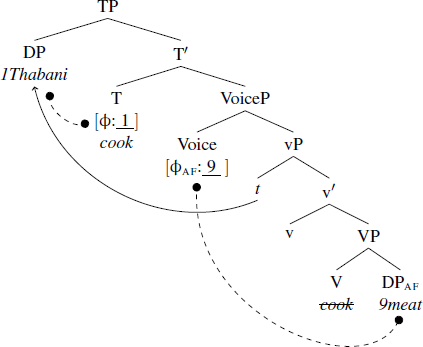

Recall that subject agreement in Ndebele is triggered by a ф-probe in T, and object agreement by a ф-probe in Voice. Due to the bundling parameter, both heads additionally bear epp. Following previous literature, I assume that operations – here, Agree and internal Merge – triggered by features of the same head can be ordered with one another (Bruening 2005; van Koppen 2005; Anand & Nevins 2006; Heck & Müller 2007; Sigurðsson & Holmberg 2008; Müller 2009; Asarina 2011; Halpert 2012; 2015; Richards 2013; Georgi 2014).16 I represent this ordering using the ordered set notation for probe features, as in (40). I propose that in T, ф probes before epp, while in Voice, epp probes before ф.17

- (40)

- [TP T⟨ф,epp⟩ [VoiceP Voice⟨epp, ф⟩ [vP Agent v [VP V Theme ]]]]

Since arguments can stay in situ, the ⟨epp, ф:__⟩ bundle is optional in Voice (but is always present in T). Finally, I propose that VoiceP is the locus of the verb-level phase (see section 6.2 for evidence). The proposal is summarized in (41).

- (41)

- Proposal

- a.

- T has ⟨ф:__, epp⟩

- b.

- Voice has ⟨epp, ф:__af ⟩ optionally

- c.

- Voice is a phase head

With these details in place, we can derive the NOM/ACC agreement pattern in a way that does not involve countercyclicity, as detailed below.

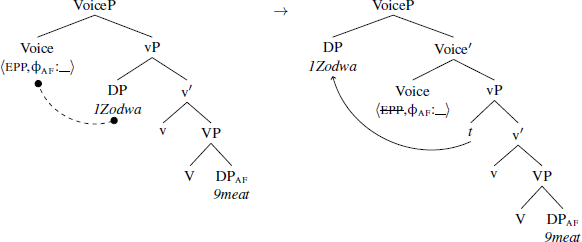

An SVO sentence with object agreement, such as (42), is derived when Voice has ⟨epp, ф:__ ⟩. epp, being the first element of the ordered set, probes first, finds the closest goal (here, the Agent), and triggers its movement to Spec,VoiceP (43).

- (42)

- U-Zodwa

- a-1Zodwa

- w-a-yi-phek-a

- 1s-pst-9o-cook-fv

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Zodwa cooked the meat’

- (43)

- Step 1: epp in Voice finds the external argument

I assume that the epp feature is deleted after it triggers this operation. This leaves Voice with an agreement probe, which finds the object due to its af feature, as shown in (44). (Subject DPs can themselves have the af feature; however, it is well-established that traces/lower copies of moved constituents do not count for the purposes of minimality and intervention. See Holmberg & Hróarsdóttir (2003) and related literature.)

- (44)

- Step 2: The ф-probe in Voice, relativized to af, finds the object

Since epp in Voice probes before ф, it is impossible for the highest argument (in this case, the Agent) to control agreement on Voice, despite being c-commanded by this probe in the base position. The Agent necessarily vacates the c-command domain of Voice before Voice engages in ф-probing. This derivation is cyclic in the sense that all features of Voice probe before any features of T do.

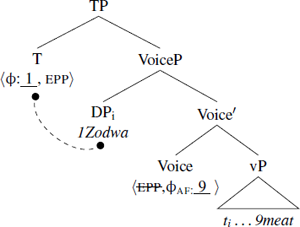

At this point in the derivation, object agreement has been established with the internal argument and the external argument has moved to the left edge of the VoiceP phase. In this position, the Agent is accessible to probes in T (before movement, the Agent was contained in the VoiceP phase):

- (45)

- Step 3: ф in T agrees with the Agent

- Step 4: epp finds the same goal as ф

The probe ordering in T gives rise to apparent spec-head agreement: T first agrees with the Agent in Spec,VoiceP and subsequently merges it as its own specifier.

SVO sentences without object agreement, such as (46), arise when ф in Voice does not find a matching goal, e.g. when the object does not bear an af feature. This correlates with the object being discourse-new/part of focus.

- (46)

- U-Zodwa

- a-1Zodwa

- w-a-pheka

- 1s-pst-cook

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Zodwa cooked meat’ [Can answer: “What did Zodwa cook/do?”]

When ф in Voice fails the search of its c-command domain, it fails to agree altogether (see section 4.2 for discussion of why it does not agree with the subject in this case). The unvalued ф-probe in Voice has no overt exponence (47-a). This is different from an unvalued ф-probe in T, whose exponence is class 15 agreement prefix ku-/kw- (47-b).

- (47)

- a.

- [Voice, ф] → ∅

- b.

- [ф] → /ɣu/(‘ku/kw’)

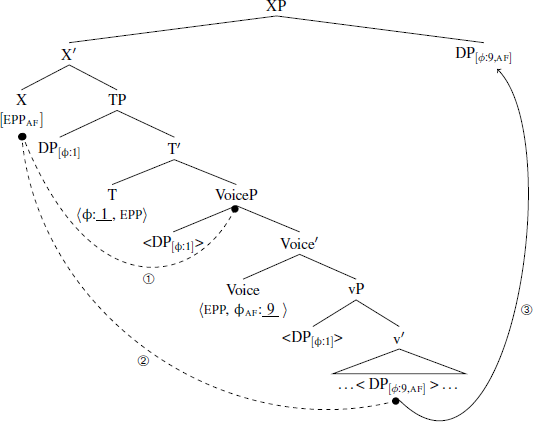

Now consider the VSO version of the same sentence (48).

- (48)

- Kw-a-(*m)-phek-a

- 15s-pst-(*1o)-cook-fv

- u-Zodwa

- a-1Zodwa

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Zodwa cooked meat’

The in-situ subject is contained in the VoiceP phase, and so T cannot reach it. T’s epp remains unchecked and its unvalued ф-probe is realized as class 15 agreement.18 What does it take for the highest argument to not move to Spec,TP? Voice must lack epp, which would otherwise move the subject to the edge of the VoiceP phase, and then inevitably to Spec,TP. Recall that, parametrically, ф-probes in Ndebele only occur on heads with an epp feature (39). If there is no epp in Voice, there can be no ф. This means that when the subject stays in situ, there is no ф-probe in Voice.

- (49)

- The structure of (48)

A similar analysis was proposed by Carstens & Mletshe (2015) for Xhosa, namely that in VS orders, T and v (which, for them, is the head with the object agreement probe) are both featurally deficient: they have neither epp nor ф (nor Case):

- a.

- SVO: [TP T[+epp/Agr/Case] … [vP v[+epp/Agr/Case]]]

- b.

- VSO: [TP T[-epp/Agr/Case] … [vP v[-epp/Agr/Case] ]]

On this account, an in-situ subject is only possible when T is defective. For Carstens & Mletshe (2015), a defective T entails a defective v, and vice versa (capturing the fact that the presence of object agreement is contingent on the presence of subject agreement; see section 6.1 for a discussion of the same facts in Ndebele). To ensure this, Carstens & Mletshe propose that the following principle holds in Xhosa:

- (51)

- defective T ↔ defective v

While this account derives the fact that an in-situ subject cannot control object agreement (v does not have an agreement probe in VS orders), it does not explain why the subject cannot control object agreement in non-defective clauses, before it is probed by T. It is also not clear what (51) would follow from, and so dispensing with it would be preferable. Finally, (51) is problematic for Ndebele, where infinitival verb forms do not show subject agreement but they do allow object agreement (52).

- (52)

- Ngi-thembis-e

- 1sg.s-promise-pst.cnj

- u-mama

- a-1mother

- [ uku-yi-klin-a

- inf-9o-clean-fv

- i-ndlu

- a-9house

- kusasa].

- tomorrow

- ‘I promised mother to clean the house tomorrow.’

The temporal anchoring of infinitive in (52) is different than that of the matrix clause: the infinitive is future-oriented relative to the matrix clause. This strongly suggests that the infinitival clause is a TP (see e.g. Wurmbrand 2014 and references cited there). If the infinitive is indeed a TP, its T head is ф-defective as it does not show agreement with any DP. Nonetheless, Voice (or v, on Carstens & Mletshe’s account) is not defective here since it agrees with the object. Thus, (52) shows that a ф-defective T does not entail a ф-defective Voice in Ndebele.19

The present analysis derives the fact that A-movement and object agreement are not sensitive to the base-generation position of arguments. No matter where a DP originates, if it’s the highest, it will move out of the search domain of the object agreement probe before probing begins. This robust pattern in schematized in (53), where each circle corresponds to a different argument structure, each of which is illustrated in (54)–(57).20

- (53)

- Possible controllers of ф-agreement with Voice in different argument structures

- (54)

- Causer + Agent: Voice can agree with Agent but not with Causer

- a.

- I-nkazanai

- a-9girl

- y-a-(*yi)-phek-is-a

- 9s-pst-(*9o)-cook-caus-fv

- ti

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- ‘The girl made Thabani cook.’

- b.

- Kw-a-(*yi)-phek-is-a

- 15s-pst-(*9o)-cook-caus-fv

- i-nkazana

- a-9girl

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- ‘The girl made Thabani cook.’

- c.

- I-nkazanai

- a-9girl

- y-a-m-phek-is-a

- 9s-pst-1o-cook-caus-fv

- ti

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- ‘The girl made Thabani cook.’

- (55)

- Agent + Benefactive: Voice can agree with Benefactive, but not with Agent

- a.

- U-Thabanii

- a-1Thabani

- w-a-(*m)-phek-el-a

- 1s-pst-(*1o)-cook-app-fv

- ti

- a-bantwana.

- a-2child

- ‘Thabani cooked for children.’

- b.

- Kw-a-(*m)-phek-el-a

- 15s-pst-(*1o)-cook-app-fv

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- a-bantwana.

- a-2child

- ‘Thabani cooked for the children.’

- c.

- U-Thabanii

- a-1Thabani

- w-a-ba-phek-el-a

- 1s-pst-2o-cook-app-fv

- ti

- a-bantwana.

- a-2child

- ‘Thabani cooked for the children.’

- (56)

- Benefactive + Theme: Voice can agree with Theme, but not with Benefactive21

- a.

- A-bantwanai

- a-2child

- b-a-(*ba)-phek-el-w-a

- 2s-pst-(*2o)-cook-app-pass-fv

- ti

- i-nyama

- a-9meat

- ngu-mama.

- by-mother

- ‘The children were cooked meat by mother.’

- b.

- A-bantwanai

- a-2child

- b-a-yi-phek-el-w-a

- 2s-pst-9o-cook-app-pass-fv

- ti

- i-nyama

- a-9meat

- ngu-mama.

- by-mother

- ‘The children were cooked the meat by mother.’

- (57)

- Theme only: Voice cannot agree with anything

- a.

- I-sihlahlai

- a-7tree

- s-a-(*si)-w-a

- 7s-pst-(*7o)-fall-fv

- ti.

- ‘The tree fell.’

- b.

- Kw-a-(*si)-w-a

- 15s-pst-(*7o)-fall-fv

- i-sihlahla.

- a-7tree

- ‘The tree fell.’

This analysis derives the apparent asymmetry in the directionality of agreement triggered by Voice and by T. T always agrees with the DP in its specifier – a spec-head agreement pattern (58). In contrast, Voice always agrees downwards and cannot reach its specifier – a rigid downward Agree pattern (59). Both patterns are derived via the same operation, (downward) Agree, combined with variable timing relative to internal Merge.

- (58)

- Spec-head agreement pattern

- a.

- Description: head H always agrees with its specifier.

- b.

- Source: ⟨ф, epp⟩ in H

- (59)

- Rigid downward-Agree pattern

- a.

- Description: head H agrees either downward or not at all

- b.

- Source: ⟨epp, ф⟩ in H

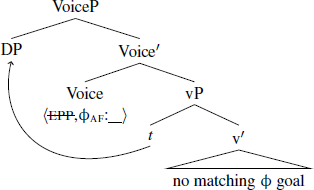

Note that the analysis presented so far only explains why the ⟨epp, ф⟩ ordering allows downward Agree. It does not explain why the ф-probe cannot undergo cyclic expansion (Rezac 2003; 2004; Béjar & Rezac 2009) and agree with its specifier just in case there is no matching goal in its complement. I address this issue in section 4.2.

A key feature of the proposed analysis is the ф→epp parameter (Baker 2003; Collins 2004), which itself is a specific implementation of the observation that agreement cooccurs with movement in this language family. Two other implementations that can be found in the literature in include i) upward Agree (Baker 2008) and ii) a multifunctional probe that triggers both agreement and movement (Carstens 2005). The facts discussed in this paper are problematic for both of these implementations. The upward Agree approach incorrectly predicts that the object-agreement probe should agree with the canonical subject immediately after the subject moves out of vP. If agreement and movement cooccur because they are triggered by the same feature (фepp for Carstens), then we expect the two operations to always target the same DP. This is crucially not the case in the Ndebele Voice, where epp targets the subject, while ф targets some lower DP (an object). Disjoint satisfaction of epp and ф has been previously observed in Zulu hyperraising constructions (Halpert 2012; 2015). Thus, the present findings contribute further evidence that, apart from their obligatory cooccurrence, epp and ф in Bantu languages are not special: they are separate features that probe their c-command domain.

4.2 The Bleeding of Probe Expansion

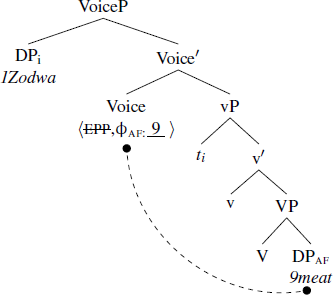

In section 4.1, I proposed that epp and ф in Voice find different goals, deriving the NOM/ACC agreement pattern. One aspect of this analysis requires elaboration: what exactly happens when Voice finds no matching ф-goal in its complement? This would be the case in intransitive clauses, or in clauses with objects that do not have the af feature to which ф in Voice is relativized (60).

- (60)

- No goal for ф in Voice

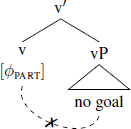

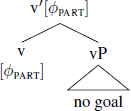

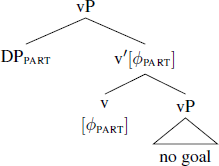

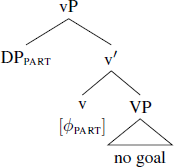

Recall that, in the absence of a c-commanded goal, ф in Voice remains unvalued and is spelled out with a null exponent. One might expect, however, that, after failing to locate a goal in its c-command domain, the ф-probe would undergo cyclic expansion (Rezac 2003; 2004; Béjar & Rezac 2009) – that is, project to the bar level, from where it would c-command the DP in its specifier under sisterhood. If the subject in Spec,VoiceP has the af feature, we would expect agreement in Voice to be controlled by the canonical subject in this scenario. This, as we have seen, is never the case – Voice can never agree with the canonical subject and so probe expansion must be unavailable here. Descriptively, one might characterize this restriction as follows: if a probe fails to agree with a goal inside of its complement, it cannot take a second pass at agreeing with it after the goal moves to the probe’s specifier. The canonical subject originates in the c-command domain of Voice (61). Since Voice does not agree with it in that position (because epp probes before ф (62)), it doesn’t get to agree with this DP again after movement (63).

- (61)

- (62)

- (63)

Note that if epp and ф appeared in the reverse order in (61), we would derive spec-head agreement of the kind we find in TP. Crucially, this agreement would not be a case of probe expansion but rather of downward Agree applying before movement (see (45)).

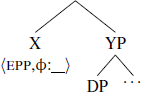

I propose that the absence of probe expansion in the case at hand is ultimately due to the ordering of epp before ф. Let us assume, following Chomsky (1994), that the intermediate and maximal projections of a given head are of the same category as the head. Crucially, however, I note here that reprojection of the probe is not an automatic consequence of Bare Phrase Structure alone. I follow Béjar & Rezac (2009) in taking probe expansion to be a syntactic operation. (In Béjar & Rezac’s analysis, other operations can in fact be coupled with this particular derivational step; see ibid., p. 57 for example). A precise description of this operation is therefore required, and I provide one in (64).

- (64)

- Probe Expansion

- Structural Description:

- i.

- nodes α, β of the same category s.t. β is a root node immediately dominating α, and

- ii.

- probe feature F of α that failed the search of its c-command domain

- Structural Change: β → β[F]

As we will see immediately below, the crucial aspect of (64) is that probes expand only to root nodes. Let us see how this derives classic cases of cyclic Agree, such as those discussed by Béjar (2003) and Béjar & Rezac (2009). In Georgian, for example, a part(icipant)-probe in v agrees with the internal argument, if one is present (65-a). Otherwise, it agrees with the external argument (65-b).

- (65)

- A cyclic Agree paradigm (Georgian, data from Halle & Marantz 1993: 117)

- a.

- g-xatav

- 2sg-draw

- part object → agreement with object

- ‘I draw you’

- b.

- v-xatav

- 1sg-draw

- non-part object → agreement with subject

- ‘I draw him’

This cyclic Agree pattern follows from the definition of Probe Expansion in (64). When v is Merged with its complement, the part-probe immediately searches its complement for a matching goal. If it finds one, it agrees with it, giving rise to (65-a). If it fails, it expands, as shown in (66).

- (66)

- a.

- Agree (failed)

- b.

- Probe Expansion

- c.

- Merge of EA

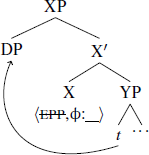

(66)-a meets the structural description for Probe Expansion: root node β (here, v’) immediately dominates node α of the same category (the v head), and α bears a feature that failed the search of its complement. Consequently, the root node inherits the probe. The next step in the derivation is external Merge of a DP in Spec,vP. In this configuration, the expanded part-probe c-commands and Agrees with the specifier DP, deriving (65-b). Importantly, for the probe to expand, Merge of the external argument must take place after ф-probing.22 The reverse order of Merge and Agree would bleed Probe Expansion, as shown in the counterfactual scenario in (67).

- (67)

- a.

- Merge of EA

- b.

- Agree (failed)

- c.

- No Probe Expansion

(67)-b does not meet the structural description for Probe Expansion: there is no β that is both the root node and immediately dominates α, the v head. Merge of the external argument before Agree would thus bleed Probe Expansion by creating a new root node, vP.

Such a bleeding derivation is responsible for the absence of Probe Expansion in VoiceP in Ndebele. As proposed above, Merge applies before Agree in Voice, creating a new root node and thus bleeding the expansion of the unvalued ф-probe. The only difference between Ndebele and the counterfactual Georgian scenario in (67) is that Merge in Ndebele VoiceP is internal, not external:

- (68)

- a.

- Internal Merge

- b.

- Agree (failed)

- c.

- No Probe Expansion

Again, because only root nodes can inherit probes, Probe Expansion cannot percolate the ф probe from Voice to Voice′ in (68-c). Thus, if ф in Voice fails the search of its complement, it fails the search terminally – a rigid downward Agree pattern.

A noteworthy consequence of the proposed definition of Probe Expansion is that expanded probes can only agree with externally Merged specifiers. (And even then, the probe will expand only if Merge applies before Agree – see (66) vs (67)). If the specifier is the result of internal Merge, neither ordering of Merge and Agree is compatible with Probe Expansion: If the feature ordering is ⟨epp, ф⟩, Probe Expansion is bled by Merge, as in the Ndebele VoiceP. If the feature ordering is ⟨ф, epp⟩, ф-agreement takes place when the goal DP is still in the probe’s complement, and so no expansion is needed in the first place. In other words, it is derivationally impossible for a ф-probe to have a goal in its c-command domain at some point in the derivation, but only agree with it after the goal has moved out of that domain. This gives rise to a limited set of contexts for Probe Expansion, which I summarize in (69).

- (69)

- Probe Expansion by context (Merge type and relative timing of Merge and Agree)

⟨Agree, Merge⟩ ⟨Merge, Agree⟩ External Merge Yes No Internal Merge No No

A further consequence of this view is that it allows us to treat expansion as a general property of probing, present even in languages/constructions which do not exhibit a cyclic Agree pattern. The lack of such a pattern could be due to the bleeding of Probe Expansion, rather than due to its absence from the grammar altogether. This hypothesis requires an empirical evaluation that’s beyond the scope of this article.

5 Implications for object dislocation

As in related Bantu languages, object agreement in Ndebele requires object dislocation (see section 2.1). A common assumption is that, like subject agreement, object agreement is triggered by the head that attracts the agreeing DP to its specifier/adjunct position (e.g. Baker 2008; Halpert & Zeller 2015). A consequence of the present analysis is that object agreement and object dislocation are triggered by different heads. Object agreement is triggered by ф on Voice, but epp on Voice is satisfied by the canonical subject, not the agreeing object. In this section, I propose that right-dislocation is triggered by an epp probe located above TP and relativized to af-bearing phrases.

Before introducing the analysis, it should be made clear that dislocated objects in Ndebele are indeed moved, rather than base-generated in the dislocated position. Under the base-generation view, object agreement would be controlled by a pro in a vP-internal object position and the overt object would be base-generated in a dislocated position. The pro-analysis is, however, incompatible with the fact that Ndebele allows extraction out of dislocated objects. More importantly, the extraction position does not c-command the dislocated position of the object. We observe this in dislocated raising-to-object CPs. As shown in (70-a), the CP complement of the verb funa ‘want’ can be dislocated to the right of a matrix adverb (kakhulu ‘a lot/really’). Alternatively, the embedded subject – here, the interrogative pronoun ‘who’ – may raise to matrix object, followed by remnant right-dislocation of the complement CP (70-b).

- (70)

- a.

- U-∅-fun-ak

- 2sg.s-cnj-want-fv

- [vP tk tj ]

- kakhulu

- a.lot

- [CP

- ukuthi

- COMP

- *(u)-bani

- *(A)-1who

- a-buy-e?

- 1s-come-sbjv

- ]j

- ‘Who do you really want to come?’

- b.

- U-∅-fun-ak

- 2sg.s-cnj-want-fv

- [vP tk

- banii

- 1who

- tj ]

- kakhulu

- a.lot

- [CP

- ukuthi

- comp

- ti

- a-buy-e?

- 1s-come-sbjv

- ]j

- ‘Who do you really want to come?’

The use of an interrogative pronoun as the raising DP helps us diagnose the landing position of raising-to-object. It has been previously shown that interrogative pronouns in Ndebele may lack the augment prefix (here u-) only when they are vP-internal (Pietraszko 2021; see Halpert 2015, Halpert & Zeller 2015 for similar findings in Zulu).23 Thus, the interrogative pronoun in (70-a) must have an augment since it is in Spec,TP. The absence of an augment on the raised interrogative pronoun in (70-b) reveals that the raised object is inside matrix vP. In the same sentence, we see that the CP in which the pronoun originated is outside of matrix vP, as it appears to the right of a matrix adverb. If the dislocated CP were base-generated in the dislocated position, (70-b) would involve A-movement of the DP bani ‘who’ to a non-c-commanding position. Assuming that that’s not a possibility, we conclude that the right-dislocation of the CP complement arose via movement.

Returning to the main issue, I propose that right-dislocation is triggered by a probe located immediately above TP. This is motivated by the fact that right dislocation can target temporal adverbs, such as ‘yesterday’, which, by assumption, are base-generated in the tense-aspect domain:24

- (71)

- [TP

- Ngi-yi-phek-ile

- 1sg.s-9o-cook-pst.dsj

- {izolo}

- yesterday

- ]

- inyama

- meat

- {izolo}.

- yesterday

- ‘I cooked the meat yesterday.’

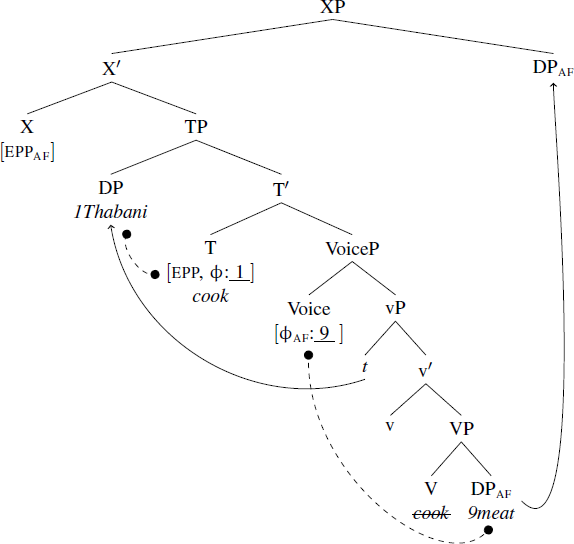

Following Zeller (2008; 2015), I propose that the dislocation probe in X is relativized to DPs with an af (Antifocus) feature, as shown in (72).

- (72)

- Object right-dislocation in a transitive clause

We can now see why object agreement entails object dislocation, despite the fact that the two are not triggered by probes on the same head. The dislocation probe is relativized to af-bearing DPs, just like the the ф-probe in Voice. This means that, when there is a goal for object agreement, there is a goal for the dislocation probe, and vice versa. Therefore, the two always go hand in hand.

An immediate question arises: why can X access the in-situ object across the VoiceP phase boundary? This is made possible by the fact that the ф-probe in Voice is relativized to af: [фaf], which, I propose, amounts to Voice having the af feature. Thus, Voice (and by Bare Phrase Structure (Chomsky, 1994), VoiceP) is itself a matching goal for the dislocation probe. This means that the dislocation probe always finds VoiceP first (73).

- (73)

- Object dislocation: eppaf finds af in VoiceP and then in the object DP

Following Rackowski & Richards (2005) and Halpert (2012; 2015), I assume that, when a probe agrees with a phasal category, the phasal domain becomes transparent for that probe. Note that VoiceP cannot itself be dislocated, as only DPs can satisfy the epp on X fully. VoiceP is only a partially matching goal, which is enough to “unlock” the phase but not enough to undergo movement (in this respect, VoiceP is analogous to CP in Halpert’s analysis of hyperraising in Zulu).

As we saw in section 3.1, multiple DPs may undergo dislocation in Ndebele. This suggests that X’s epp is an insatiable probe (Deal 2015; to appear; Clem 2019; to appear), meaning that it is not deleted after establishing one relation and consequently, it may attract multiple DPs. (See Bošković 1999 for an alternative treatment of similar effects, in the context of multiple-wh movement.) This is the case when both objects of a double-object construction bear the af feature (see also the analysis of (70-b), above). Recall that, in those cases, object agreement must be controlled by the higher, indirect, object:

- (74)

- U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- [VoiceP

- u-ya-ba-phek-el-a

- 1s-dsj-2o-cook-app-fv

- ti tj ]

- a-bantwanai

- a-2child

- i-nyamaj.

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani is cooking the meat for the children’

The dissociation of the object agreement probe and the dislocation probe makes it unsurprising that the direct object may be dislocated without controlling agreement, or more generally, that there can be multiple dislocated objects but only one instance of object agreement. ф-agreement is not what is responsible for object dislocation. ф in Voice is a simple (i.e. a non-insatiable) probe, which becomes inactive after being valued. The dislocation probe is an insatiable movement probe and does not require ф-agreement with its goals. It only requires access to the content of VoiceP, made possible by agreement with VoiceP itself.

Another correct prediction of this account is that subjects bearing af can also be dislocated:

- (75)

- U-∅-phek-a

- 1s-cnj-cook-fv

- i-suphu

- a-9soup

- pandle

- outside

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- ‘Thabani cooks soup outside.’

As predicted, the insatiable probe on X will dislocate both the subject and the object if both bear af:

- (76)

- U-ya-yi-phek-a

- 1s-dsj-9o-cook-fv

- pandle

- outside

- i-suphu

- a-9soup

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- ‘Thabani cooks the soup outside.’

Related to this is the generalization that dislocated subjects in Ndebele, as in many other Bantu languages, must control subject agreement:

- (77)

- *Ku-∅-pheka

- 15s-cnj-cook

- i-suphu

- a-9soup

- pandle

- outside

- u-Thabani. (cf. (75))

- a-1Thabani

- ‘Thabani cooks soup outside.’

The ungrammaticality of (77) falls under the generalization observed for many Bantu languages that vP-external subjects necessarily control subject agreement (see e.g. Baker 2003; Baker 2008). One way this generalization could be derived is through a requirement that dislocation must proceed through an agreeing position, such Spec,TP. However, we independently know that no such requirement holds for objects, which can be dislocated directly from their in-situ position (see, e.g. (73)) and without controlling agreement (see the direct object in (74)). In contrast, the ungrammaticality of (77) follows directly from the present account. For the subject to remain in-situ, Voice must lack epp. This in turn means that Voice lacks a ф-probe, as well (recall (39), above). Since the ф-probe on Voice bears the af feature that renders VoiceP a viable target for X, a ф-less VoiceP cannot be “unlocked”. Consequently, an in-situ subject is invisible not only to T, but also to X.

Finally, we correctly predict that object dislocation is impossible if the subject remains in situ:

- (78)

- *Ku-∅-(yi)-pheka

- 15s-cnj-(9o)-cook

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- pandle

- outside

- i-suphu.

- a-9soup

- ‘Thabani cooks soup outside.’

The ungrammaticality of (78) receives a similar explanation as (77). An in-situ subject entails that Voice lacks фaf, which in turn prevents unlocking the VoiceP phase and renders all arguments invisible to VoiceP-external probes, including X. Thus, object dislocation obligatorily cooccurs not just with object agreement but also with subject agreement. The properties of dislocation derived by this account and their explanations are summarized in (79).

- (79)

- Properties of right-dislocation and their explanation under the present account

- i.

- Dislocation can target both subjects and objects.

- Explanation: epp on X is an insatiable movement probe.

- ii.

- Dislocation is required for agreed-with objects.

- Explanation: The dislocation probe is relativized to af, just like the object-agreement probe. If there is a goal for latter, there is a goal for the former.

- iii.

- Dislocation is not required for agreed-with subjects.

- Explanation: Dislocation is relativized to af, but ф on T is not (see section 6.2 for evidence). A subject without af can agree with T but cannot be dislocated.

- iv.

- Dislocation (of any argument) is contingent on subject agreement.

- Explanation: The lack of subject agreement indicates that the subject is in-situ, which in turn means that VoiceP lacks фaf, and without it, VoiceP phase remains opaque.

6 Further evidence

In this section, I discuss three puzzles in agreement and A-movement in Ndebele that receive a simple explanation under the proposed account of the agreement pattern discussed so far. These puzzles have been observed in other Bantu languages and they include: i) defective intervention effects in VSO clauses, ii) optionality of subject movement and agreement, and iii) an object agreement asymmetry in passives of ditransitives.

6.1 Deriving defective intervention effects in object agreement

The account presented in section 4 derives the fact that in situ subjects do not control agreement on Voice, despite being c-commanded by it:

- (80)

- Kw-a-(*m)-phek-a

- 15s-pst-1o-cook-fv

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani cooked meat’

In fact, Voice cannot agree with an object in this configuration, either:

- (81)

- Kw-a-(*yi)-phek-a

- 15s-pst-9o-cook-fv

- u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘Thabani cooked meat’

(80) and (81) together look like a case of defective intervention: the higher DP cannot control agreement on Voice and at the same time it blocks agreement with a lower, otherwise legitimate, goal. It is difficult to see, however, what would make the subject a defective intervener. As discussed in section 3.2, ф in Voice does not seem to be relativized to any specific case, so case-based intervention is an unlikely explanation.

The analysis proposed here derives the ungrammaticality of (81) in a straightforward way. Recall that, in order for the subject to stay in situ, Voice must lack its epp probe. Since ф-probes are parametrically restricted to appear only on heads with epp (39), there is no ф-probe in Voice when the subject stays in situ. This means that Voice cannot agree with any DP in VS orders. Strictly speaking, then, the phenomenon at hand is not an instance of intervention at all: if the intervener (the subject) is there (in situ), there is no probe to intervene with; and when the probe is present, the intervener is always moved out of the ф-probe’s c-command domain (by epp on Voice) before probing begins.

These facts additionally argue against an alternative analysis of why in-situ subjects do not control agreement on Voice: one might propose that an in-situ subject is not a possible goal for ф on Voice. Indeed, in-situ subjects are normally in focus and so they likely lack the af feature to which ф in Voice is relativized. However, this explanation incorrectly predicts that in-situ subjects should not block object agreement with lower DPs since af-less DPs are otherwise not interveners for object agreement (see section 3.1 for a discussion of double-object constructions, in which the lower object can be agreed with as long as the higher object lacks af).25

6.2 Deriving the optionality of subject movement and agreement

The present analysis provides a solution to another well-known property of many Bantu languages, namely the optionality of subject movement to Spec,TP and agreement with T. If T has epp and ф, it remains unclear why the probes sometimes find the subject but other times they do not. Here, the answer is the following: if Voice does not have epp, the subject is trapped in vP and is invisible to T due to phasal VoiceP. That is, T always has epp and ф, but the accessibility of the subject depends on the presence of epp in Voice, which is optional.

A different solution has been proposed for Zulu by Zeller (2008; 2015) and for Xhosa by Carstens & Mletshe (2015). As discussed in section 4, Carstens & Mletshe propose that T optionally lacks epp and ф. In the absence of those features, the subject remains in situ and does not control agreement on T. However, as pointed out by Zeller (2015), this account incorrectly predicts that there should be no subject agreement exponent whatsoever in VS orders (since there is nothing to expone). The facts are different – both in Zulu, as shown by Zeller, and in Ndebele, as shown in (82).

- (82)

- a.

- Kw-a-phek-a

- 15s-pst-cook-fv

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- ‘Thabani cooked’

- b.

- *A-phek-a

- pst-cook-fv

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- ‘Thabani cooked’

When T does not agree with the subject, its ф-probe is exponed as class 15 agreement. This, in turn, suggests that the probe is present but remains unvalued (Preminger 2009). It has previously been argued that class 15 is featurally the most underspecified class (Carstens 1991; Pietraszko 2019). In feature-geometric terms (Harley & Ritter 2002), it can be described as a geometry consisting of just the topmost ф-node. Thus, the shape of a ф-probe that has failed to be valued is identical with class 15 geometry, explaining the morphological form of the unvalued ф probe in T (82-a).

The other possible explanation of why sometimes T doesn’t interact with the subject was proposed by Zeller (2008; 2015) for Zulu. Zeller proposes that the probe on T is not in fact a ф-probe, but rather a probe that looks for topical DPs – specifically, DPs bearing the Antifocus feature. This is the analysis assumed here for object agreement and movement, but not for subjects, which, as shown below, can move to Spec,TP with or without the af feature.

For Zeller (2008), the ф-agreement in T (and in other heads) is parasitic on af-agreement (which could be implemented as a ф probe relativizated to af).26 Zeller’s motivation for this account is the fact that in Zulu, in-situ subjects are always in focus (narrow or wide presentational focus), while preverbal, agreeing subjects are topical. This is largely true in Ndebele, as well, as illustrated in (83) by the distribution of DPs modified by the focus particle kuphela ‘only’, which is normally incompatible with a preverbal position.

- (83)

- a.

- Kw-a-phek-a

- 15s-pst-cook-fv

- [u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- kuphela].

- only

- ‘Only Thabani cooked.’

- b.

- *[U-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- kuphela]

- only

- w-a-phek-a.

- 1s-pst-cook-fv

- ‘Only Thabani cooked.’

On Zeller’s account, only-DPs, being necessarily focused, do not have the af feature and therefore cannot raise to T. This correlation between agreement and Antifocus does not hold for all Bantu languages, however. Schneider-Zioga (2007) shows that focused DPs in Kinande can control subject agreement in certain clause types (in brief, in clauses where topicalization of the subject is blocked.) Similar facts are found in Ndebele (Pietraszko 2017a; 2021): preverbal, agreeing subjects may be focused in some clause types. For instance, relative and subjunctive clauses allow preverbal subjects to be narrowly focused. (Carstens & Zeller 2020 report that the same is true for some speakers of Zulu.) I illustrate this for Ndebele with a subjunctive clause in (84-a). Note that, as in other clause types, raising to Spec,TP is optional in subjunctive clauses (84-b).

- (84)

- a.

- Ngi-fun-a

- 1sg-want-fv

- ukuthi

- comp

- [u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- kuphela]

- only

- a-phek-e.

- 1s-cook-sbjv

- ‘I want it to be the case that only Thabani cooks.’

- b.

- Ngi-fun-a

- 1sg-want-fv

- ukuthi

- comp

- ku-phek-e

- 15s-cook-sbjv

- [u-Thabani

- a-1Thabani

- kuphela].

- only

- ‘I want it to be the case that only Thabani cooks.’

(84) shows that movement to Spec,TP and agreement with T cannot be linked to discourse related features: the same kind of focus is available for the subject whether it moves to Spec,TP or stays in situ.

We have thus ruled out two alternative explanations of why T does not always find the canonical subject. This fact is not due to an optional absence of [ф,epp] in T. Nor is it due to af-relativization of the probes in T. This strongly supports the proposal made here: VoiceP is phasal in this language and consequently the subject’s visibility to T depends on whether it moves to Spec,VoiceP or not.

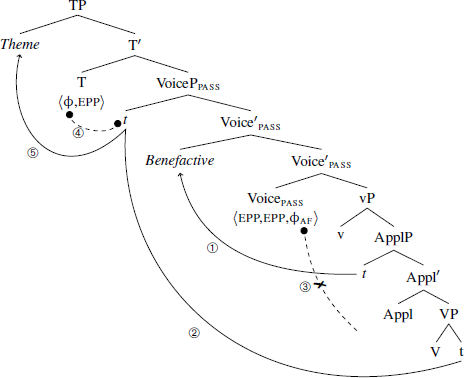

6.3 Deriving an object agreement asymmetry in passives of distransitives

The final, but important, piece of evidence for A-movement to Spec,VoiceP comes from object agreement in passives. Passives of double-object constructions are symmetric in that either object can move to Spec,TP and become the surface subject (85). Constructions in which the Theme (the lower of the two arguments) undergoes this movement will be referred to as Theme passives, and constructions in which the applied argument moves will be called Benefactive passives.27

- (85)

- a.

- I-nyamaj

- a-9meat

- y-a-phek-el-w-a

- 9s-pst-cook-app-psv-fv

- a-bantwana

- a-2child

-

. Theme passive

. Theme passive

- ‘The meat was cooked for children.’

- b.

- A-bantwanai

- a-2child

- b-a-phek-el-w-a

- 2s-pst-cook-app-psv-fv

- i-nyama. Benefactive passive

- a-9meat

- ‘The children were cooked meat.’

One possible analysis of this kind of symmetry is A-scrambling of the Theme to a position in which it is a closer goal (or at least an equidistant goal) to T. Which head allows the scrambling? It is neither Appl nor v – each would overgenerate symmetric phenomena in the language. If the Theme could optionally scramble to the outermost specifier of ApplP, we would expect object agreement to be truly symmetric, contrary to fact (see section 3.1). If the Theme could scramble to the edge of vP, we would expect that the Theme could raise to Spec,TP across an Agent. While some Bantu languages, for instance Luguru (86), allow such Agent–Theme inversion constructions, this is not possible in Ndebele (87).

- (86)

- a.

- Imw-ana

- 1-child

- ka-tula

- 1s-broke

- ici-ya.

- 7-pot

- ‘The child broke the pot.’

- b.

- Ici-ya

- 7-pot

- ci-tula

- 7s-broke

- imw-ana.

- 1-child

- ‘The child broke the pot.’ Luguru, (Marten & van der Wal 2014: 330–331)

- (87)

- #I-nyama

- a-9meat

- y-a-phek-a

- 9s-pst-cook-fv

- u-Thabani.

- a-1Thabani

- #’The meat cooked Thabani.’

- Cannot mean: ‘Thabani cooked meat.’

Thus, the scrambling of the Theme necessary for its passivization can be neither to the edge of ApplP nor to the edge of vP. Another possibility is scrambling to the edge of VoiceP. Under this hypothesis, inversion would arise due to the features of Voice. This offers a new way of understanding these facts: passive Voice can trigger A-scrambling, but active Voice cannot. This explains why inversion is possible in (85) but not in (87) – only the former is construed with Voicepass, the head that allows such scrambling. We also derive the lack of symmetrical object agreement in active clauses (I turn to object agreement in passives shortly). Given this, I propose that Voicepass has an optional extra epp feature, triggering movement of the Theme to the outermost specifier of VoiceP. When present, this epp feature will give rise to a Theme passive. When the extra epp is absent, the more local Benefactive becomes the subject.28

Despite this symmetry observed in passives of ditransitives, there exists a puzzling asymmetry between them, described in (88) and illustrated in (89).

- (88)

- Object agreement asymmetry in passives

- a.

- In Benefactive passives, the Theme can control object agreement.

- b.

- In Theme passives, the Benefactive cannot control object agreement.

- (89)

- a.

- A-bantwana

- a-2child

- b-a-yi-phek-el-w-a

- 2s-pst-9o-cook-app-psv-fv

- i-nyama.

- a-9meat

- ‘The children were cooked meat.’

- b.

- I-nyama

- a-9meat

- y-a-(*ba)-phek-el-w-a

- 9s-pst-2o-cook-app-psv-fv