1 Introduction

Malagasy has a process referred to as N-bonding, a term coined by Keenan (2000) to describe a morphological process in which material from nominal arguments is morphologically bound to certain heads.1 In the usual case, a segment n is used as a bonding element between the two components. This process is shown in (1) illustrating the N-bonding element (bolded) between a verb and the following external argument, as in (1a), between a possessee and its possessor (1b), and between a preposition and its complement (1c).2 Here and throughout, the N-bonding element is glossed as n.

- (1)

- a.

- Voa-voha-n’-ilay

- pv-open-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- ilay

- dem

- varavarana.

- door

- ‘That door was opened by that girl.’ Verb + EA

- b.

- trano-n’-ilay

- house-n-dem

- olona

- person

- ‘that person’s house’ Possessee + Possessor

- c.

- ami-n’-ilay

- prep-n-dem

- seza

- chair

- ‘on that chair’ Preposition + Complement

As Keenan (2000) notes, both the presence of the N-bonding element and its shape depend on the forms of the two components being bound. Thus, it is not always the case that a bonding element n is realized on the surface. For example, the sentences in (2) below are similar to those in (1) in that they include a verb and an adjacent external argument (2a) or a possessee followed by a possessor (2b), both constructions in which N-bonding is expected. However, when the noun or verb ends in a final syllable ka or tra, that final syllable becomes ky or try, and no additional n segment is observed, as shown in (2). According to Keenan (2000), no N-bonding element is inserted in (2). Instead, the pattern observed in these constructions is derived by a rule that raises the word-final vowel /a/ to /i/ (see Keenan & Polinsky 1998). Note that the vowel /i/ is represented with an orthographic y in word-final position.3

- (2)

- a.

- Tapaky

- pv.cut

- ny

- det

- olona

- person

- ny

- det

- tady.

- cord

- ‘The cord is cut by the person.’ Verb + EA

- a.

- tongotry

- foot

- ny

- det

- zaza

- child

- ‘the child’s feet’ Possessee + Possessor

Although structures like those in (1) and (2) are seen regularly in the literature on Malagasy, the role of N-bonding and whether the process arises due to syntactic or morphophonological reasons, or both, is not well understood. Moreover, the details regarding the distribution of N-bonding and the possible variation in shape of the N-bonding element require further exploration. I assume, following proposals by Paul (1996) and Pearson (2005), that in (2), the y is a possible surface form of the N-bonding element and surfaces instead of n due to the surrounding phonological context. Therefore, the N-bonding element is present in all of the examples in (1) and (2). We return to the particular cases of phonological variation in Section 5. The main claim is that N-bonding occurs consistently in these constructions and the aim is to understand the properties that are shared among them that give rise to N-bonding.

The primary goal of this paper is to provide a unified syntactic account of N-bonding that explains how N-bonding is derived, accounts for its distribution, and is consistent with the observed phonological patterns. In terms of its derivation, I propose that N-bonding reflects a particular configuration, namely head-head adjunction. Following Levin (2015), I assume that Malagasy employs a licensing strategy called Local Dislocation (Embick & Noyer 2001), a post-syntactic operation that yields a complex head. I argue that this strategy is used when an argument cannot be licensed by the structural licensing mechanisms available in the language. The resulting configuration then feeds a language-specific morphophonological operation within Ornamental Morphology (Embick & Noyer 2007; Embick 2015). Finally, I propose that the final product of these operations is the insertion of a bundle of phonological features that, depending on the phonological environment, surface as the N-bonding element. Under this approach, the distribution of N-bonding is accounted for and the associated phonological patterns follow straightforwardly. Moreover, this analysis provides additional empirical support to existing theoretical accounts on nominal licensing and morphological operations, while offering an alternative view of underlying clausal structure and voice morphology in Malagasy.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Sections 2 and 3 provide background information and an overview of the distribution of N-bonding in Malagasy. Section 4 presents the assumptions of basic Malagasy clause structure and spells out the analysis of N-bonding as a reflection of nominal licensing. Section 5 overviews the post-syntactic processes and phonological variation observed in N-bonding and provides an analysis which characterizes insertion of the N-bonding element as a language-specific morphophonological operation. Section 6 concludes.

2 Malagasy Background: Word Order and Voice Morphology

Malagasy is an Austronesian language belonging to the Western Malayo-Polynesian branch and is spoken on the island of Madagascar. Dialects of Malagasy are divided into three main groups: the eastern, western, and intermediate dialects (Andriamanatsilavo & Ratrema 1981; Kikusawa 2012; Adelaar 2013) which are distinguished by certain phonemic oppositions (see Beaujard 1998; Rasoloson & Rubino 2005). The data presented here are from the Merina dialect, a central eastern dialect spoken in the capital Antananarivo, and central plateau region. For general background on Malagasy, see also Randriamasimanana (1986), Keenan & Polinsky (1998), Paul (2000), Pearson (2001), and the many references cited therein.

Basic word order in Malagasy is predicate-initial. The examples in (3) show that this word order holds across clausal predicates of different syntactic categories. The predicate phrase can be verbal as in (3a), a bare nominal (3b), a prepositional phrase (3c), a weak quantifier (3d), or an adjectival phrase (3e). Note that the language does not mark gender and number on nouns, and phrases are generally head-initial. Thus determiners precede head nouns and prepositions are initial in PPs.

- (3)

- Basic predicate-initial word order

- a.

- M-i-hinana

- av-pfx-eat

- ny

- det

- akondro

- banana

- Rabe

- Rabe

- ‘Rabe is eating the banana.’ Verbal predicate

- b.

- Dokotera

- doctor

- iBakoly.

- det.Bakoly

- ‘Bakoly is a doctor.’ Nominal predicate

- c.

- Tany

- pst.there

- an-tsena

- at-market

- izy.

- 3sg.nom

- ‘She was at the market.’ Prepositional predicate

- d.

- Roa

- two

- ny

- det

- zana-dRasoa.

- child-Rasoa

- ‘Rasoa has two children.’

- (lit. ‘Rasoa’s children are two.’) Weak quant. predicate

- e.

- Feno

- full

- rano

- water

- ny

- det

- tavoahangy.

- bottle

- ‘The bottle is full of water.’ Adjectival predicate

Malagasy clauses contain a referentially and/or structurally prominent constituent, underlined throughout this section, a pattern observed across many Western Austronesian languages. In Malagasy, this constituent, which I call the trigger following Schachter (1987) and Pearson (2005), occurs in clause-final position and must be formally definite.4 Thus, in each of the sentences in (3), the underlined argument is also identified as the trigger. Like many other Western Austronesian languages, Malagasy exhibits a rich voice system wherein voice morphology appears on the verb reflecting the thematic role of the trigger. Malagasy exhibits three distinct voices: Agent Voice (AV), Patient Voice (PV), and Circumstantial Voice (CV), shown in (4)–(6).

In AV, the agent is the trigger and appears in clause-final position and the verb takes the AV prefix m-.5 In AV, the verb also takes one of two verbal prefixes, aN- and i-, which are shown in (4a) on the verb didy ‘cut’ and (4b) on the verb petraka ‘live’, respectively.6

- (4)

- a.

- M-an-didy

- av-pfx-cut

- ny

- det

- trondro

- fish

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ny

- det

- vavy.

- girl

- ‘The girl cuts the fish with the knife.’

- b.

- M-i-petraka

- av-pfx-live

- any

- there

- Antsirabe

- Antsirabe

- ny

- det

- vehivavy.

- woman

- ‘The woman lives in Antsirabe.’ (Pearson 2005)

In PV, the theme is the trigger and appears in clause-final position, and the verb takes a PV prefix a- or suffix -Vn, where the vowel V is lexically determined. These are shown in (5a) and (5b), respectively.7 Though not traditionally reported as a PV morpheme, the prefix voa- is also used when the theme is the trigger, as shown in (5c). This prefix has been analyzed as the telic counterpart to the PV -Vn suffix (see Keenan & Manorohanta 2001 and Travis 2005 for more discussion on voa- in Malagasy).

- (5)

- a.

- A-tao-n’-ilay

- pv-make-n-dem

- vehivavy

- woman

- ny

- det

- fiomanana.

- preparation

- ‘The preparations are being made by that woman.’

- b.

- Didi-a(n)-n’-ilay

- cut-pv-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ny

- det

- trondro.

- fish

- ‘The fish is cut by that girl with the knife.’

- c.

- Voa-voha-n’-ilay

- pv-open-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- ny

- det

- varavarana.

- door

- ‘The door was opened by that girl.’

Finally, in CV the nominal that expresses a peripheral participant role (such as instrument, location, manner, etc.) is the trigger and appears in clause-final position, as shown in (6). In CV, the verb takes the CV suffix -an and also carries a verbal prefix as in AV. A breakdown of the voice morphemes is shown in Table 1 (adapted from Pearson 2005).

Malagasy verb template and voice morphemes.

| Voice | Template | Root | Surface Form |

| Agent Voice | m- Pfx- ROOT |

didy hira |

m-an-didy m-i-hira |

| Patient Voice |

a- ROOT voa- ROOT ROOT -Vn |

tao didy didy voha |

a-tao voa-didy didi-an voha-in |

| Circumstantial Voice | Pfx- ROOT -an |

didy vidy |

an-didi-an i-vidi-an |

- (6)

- N-a-metrah-a(n)-n’-ilay

- pst-pfx-put-cv-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- ny

- det

- boky

- book

- ny

- det

- latabatra.

- table

- ‘The books were put on the table by that girl.’

Although the trigger typically occupies clause-final position, certain kinds of complement clauses and sentence-level adverbials such as omaly ‘yesterday’ and matetika ‘generally’ can follow the trigger, as shown in (7). For more discussion of post-trigger constituents, see Pearson (2001).

- (7)

- a.

- Nanoratra

- pst.av.write

- taratasy

- letter

- ny

- det

- mpianatra

- student

- omaly.

- yesterday

- ‘Yesterday the student wrote a letter.’

- b.

- Mandamina

- av.arrange

- ny

- det

- trano

- house

- Rakoto

- Rakoto

- matetika.

- generally

- ‘Generally Rakoto puts the house in order.’

Word order in Malagasy additionally reflects certain adjacency requirements of the language. Relevant to the topic at hand, non-trigger agents (i.e. agents in PV and CV) must be strictly adjacent to the verb, as shown in (8) where an adverbial cannot intervene between the verb nohanina ‘eat’ and the non-trigger agent ny gidro ‘the lemur’.

- (8)

- a.

- Nohanin’-ny

- pst.pv.eat-det

- gidro

- lemur

- haingana

- quickly

- ny

- det

- voankazo

- fruit

- omaly.

- yesterday

- ‘The fruit was eaten by the lemur quickly yesterday.’

- b.

- *Nohanina haingana ny gidro ny voankazo omaly.

- c.

- *Nohanina omaly ny gidro ny voankazo omaly. (Pearson 2005)

This adjacency requirement, however, does not hold for other arguments such as non-trigger internal arguments and sole arguments of intransitives, as shown in (9). The reader is referred to the Appendix for additional discussion on adjacency patterns in the language. Following Levin (2015), I assume that this adjacency requirement is due to licensing constraints of the language; the non-trigger agents are unable to be structurally licensed in their merged position and consequently have to be adjacent to a preceding head as a means to satisfy licensing requirements. I return to the implications of adjacency and licensing constraints in Section 4.

- (9)

- a.

- Nijinja

- pst.av.cut

- an-tsirambina

- carelessly

- ny

- det

- vary

- rice

- ny

- det

- mpamboly.

- farmer

- ‘The farmer harvested the rice carelessly.’

- b.

- Maty

- pst.av.die

- angamba

- probably

- ny

- det

- vadiny.

- wife.3sg

- ‘His wife probably died.’ (Pearson 1998)

With this background on word order and voice morphology in place, I turn to the discussion of N-bonding in Malagasy. In the following sections I present the distribution of N-bonding across the verbal and nominal domains, connecting the empirical observations to a licensing approach.

3 Distribution of N-bonding

The following sections illustrate the distribution of N-bonding in Malagasy across the verbal and nominal domains. The constructions in which N-bonding is found are listed in (10). I start by showing the patterns of N-bonding in the verbal domain in Section 3.1. I will then show in Section 3.2 that the same patterns are reflected in the nominal domain. Crucially, the environments in which N-bonding occur are described as being genitive in the literature. I return to the connection between N-bonding and nominal licensing in Section 4.

- (10)

- N-bonding Environments

- a.

- between non-Agent Voice verbs and non-trigger agents

- b.

- between possessees and possessors

- c.

- between certain prepositions and their complement

- d.

- between certain adjectives and their complement8

3.1 N-bonding in the verbal domain

N-bonding occurs in both PV and CV sentences, but not in AV sentences, as shown in (11). (11b) and (11c) show PV sentences and (11d) shows a CV sentence. In both cases, N-bonding is observed between the non-Agent Voice verb and the following agent. In the literature, this post-verbal agent is described as being genitive (see e.g. Paul 1996; Keenan & Manorohanta 2001). In contrast, (11a) illustrates an AV sentence for which N-bonding is not observed.

- (11)

- a.

- Agent Voice

- M-an-didy

- av-pfx-cut

- ny

- det

- trondro

- fish

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ilay

- dem

- vavy.

- girl

- ‘That girl cuts the fish with the knife.’

- b.

- Patient Voice (-Vn)

- Didi-a(n)-n’-ilay

- cut-pv-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ny

- det

- trondro.

- fish

- ‘The fish is cut by that girl with the knife.’

- c.

- Patient Voice (voa-)

- Voa-didi-n’-ilay

- voa-cut-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ny

- det

- trondro.

- fish

- ‘The fish was cut by that girl with the knife.’

- d.

- Circumstantial Voice

- An-didi-a(n)-n’-ilay

- pfx-cut-cv-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- ny

- det

- trondro

- fish

- ny

- det

- antsy.

- knife

- ‘The knife is used by that girl to cut the fish.’

In PV and CV sentences, the verb often takes a suffix voice morpheme. For example, the verb didy ‘to cut’ takes the PV suffix -an in (11b) and the CV suffix -an in (11d). (Recall that the PV suffix is -Vn, where the vowel is lexically determined. For the verb didy, the PV suffix is realized as -an.) When the N-bonding element comes between the agent and preceding verb, where the verb takes a suffix that ends in n, it is not always clear that the N-bonding element is independent from the voice morpheme.9 I include (11c) to show the presence of the N-bonding element in the absence of a voice suffix. Rather than taking the PV suffix -Vn, the verb in (11c) takes the prefix voa-.10 This example shows that the N-bonding element is distinct from the preceding verb and the following demonstrative.

Note also that the presence or absence of N-bonding in these environments is not optional. That is, the presence of N-bonding in an AV sentence leads to ungrammaticality, as shown in (12a). On the other hand, the absence of N-bonding in PV and CV sentences leads to ungrammaticality, as shown in (12b) and (12c).

- (12)

- a.

- Agent Voice

- *M-an-didi-n’-ny

- av-pfx-cut-n-det

- trondro

- fish

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ilay

- dem

- vavy.

- girl

- Intended: ‘That girl cuts the fish with the knife.’

- b.

- Patient Voice (voa-)

- *Voa-didy

- voa-cut

- ilay

- dem

- vavy

- girl

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ny

- det

- trondro.

- fish

- Intended: ‘The fish was cut by that girl with the knife.’

- c.

- Circumstantial Voice

- *An-didi-ana

- pfx-cut-cv

- ilay

- dem

- vavy

- girl

- ny

- det

- trondro

- fish

- ny

- det

- antsy.

- knife

- Intended: ‘The knife is used by that girl to cut the fish.’

In the verbal domain, N-bonding also does not occur between a verb and an adjacent argument if that argument is the trigger. This is shown in (13) where the theme is the sole argument of the clause and is thus the trigger. Similarly, N-bonding does not occur between a verb and an adjacent prepositional phrase, as shown in (14). Therefore, within the verbal domain it is not the case that N-bonding occurs between non-Agent Voice verbs and any adjacent constituent. Rather, N-bonding occurs only between a non-Agent Voice verb and a non-trigger (genitive) agent.

- (13)

- No N-bonding between verb and trigger

- Voa-didy

- pv-cut

- ny

- det

- trondro.

- fish

- ‘The fish was cut.’

- (14)

- No N-bonding between verb and prepositional phrase

- Voa-didy

- pv-cut

- amin’-ny

- prep-det

- antsy

- knife

- ny

- det

- trondro.

- fish

- ‘The fish was cut with the knife.’

3.2 N-bonding in the nominal domain

In the nominal domain, N-bonding is observed in possessive constructions, as shown in (15a), and between certain prepositions and adjectives and their complements, as shown in (15b) and (15c). These examples additionally show that the shape of the D-material (i.e. definite determiner ny, demonstrative ilay, etc.) does not affect the form of the N-bonding element, which consistently appears as n.11

- (15)

- a.

- Possessee + Possessor

- trano-n’-ilay

- house-n-dem

- olona

- person

- ‘that person’s house’ (Keenan & Polinsky 1998)

- b.

- Prep + Complement

- ami-n’-ilay

- prep-n-dem

- seza

- chair

- ‘on that chair’ (Pearson 2005)

- c.

- Adj + Complement

- mainti-n’-ny

- black-n-det

- molaly

- soot

- ‘blackened by (the) soot’ (Paul 1996)

The observation that N-bonding occurs with certain prepositions and adjectives requires further explanation. In Malagasy, complements of prepositions and adjectives are marked for one of three distinct cases. These are traditionally labeled as ‘nominative’, ‘accusative’, and ‘genitive’. I adopt these labels for descriptive purposes, but will return to the distribution of case in Malagasy in Section 4. Distinct case morphology occurs most consistently in the pronominal system, which is presented in Table 2.

Malagasy pronoun series.

| Nominative | Accusative | Genitive | |

| 1st SG | izaho, aho | ahy | -ko/-o |

| 2nd SG | ianao | anao | -nao/-ao |

| 3rd SG | izy | azy | -ny |

| 1st PL Incl | isika | antsika | -ntsika/-tsika |

| 1st PL Excl | izahay | anay | -nay/-ay |

| 2nd PL | ianareo | anareo | -nareo/-areo |

| 3rd PL | izy (ireo) | azy (ireo) | -ny/izy ireo |

I start with prepositions. A given preposition can assign either nominative, accusative, or genitive case to its complement. The sentences in (16)–(18) show that patterns of N-bonding emerge only when the complement is marked for genitive case. In (16), the complement of the preposition noho ‘because of’ is marked for nominative case and as a result no N-bonding occurs; no additional N-bonding element is found in the construction. The same pattern is found when the complement of a preposition is marked for accusative case. This is seen in (17) for the preposition lavitra ‘far from’. Lastly, the examples in (18) show the presence of N-bonding when the complement of a preposition is marked for genitive case. For example, (18a) shows that the preposition aloha ‘in front of’ takes the genitive pronoun -ny and (18b) shows that when the complement of the preposition is a nominal DP, the N-bonding element n appears between the two. We will return to the connection between N-bonding and the pronominal paradigm in Section 4.3.3.

- (16)

- Preposition + nominative complement

- a.

- noho

- because.of

- izy

- 3sg.nom

- ‘because of him/her’

- b.

- Vaky

- broken

- ny

- det

- vilia

- plate

- noho

- because.of

- ilay

- dem

- zaza.

- child

- ‘The plate is broken because of that child.’

- (17)

- Preposition + accusative complement

- a.

- lavitra

- far.from

- azy

- 3sg.acc

- ‘far from him/her’

- b.

- Mipetraka

- av.live

- lavitra

- far.from

- ny

- det

- tsena

- market

- ny

- det

- vavy.

- girl

- ‘The girl lives far from the market.’

- (18)

- Preposition + genitive complement

- a.

- aloha-ny

- in.front-3sg.gen

- ‘in front of him/her’

- b.

- aloha-n’-ilay

- in.front-n-dem

- fiara

- car

- ‘in front of that car’

There is a similar division for adjectival predicates in Malagasy, which occur with a following nominal in one of three forms (see Ralalaoherivony 1995) listed in (19).

- (19)

- Three forms of Adj+DP constructions

- i. Nominal is marked for accusative case.

- ii. Preposition appears between the adjective and nominal, where the nominal is marked for accusative case.

- iii. Nominal is not marked for accusative case.

Examples of the three different forms are illustrated in (20). Crucially, N-bonding occurs only when the nominal appears without accusative case (20c). This provides preliminary support for a licensing account for N-bonding, which I develop in more detail in Section 4.3.

- (20)

- Adjective + DP construction

- a.

- antra

- compassionate

- olona

- person.acc

- ‘compassionate to people’

- b.

- tsara

- good

- ho

- prep

- azy

- 3sg.acc

- ‘good for him’

- c.

- mainti-n’-ny

- black-n-det

- molaly

- soot

- ‘blackened by soot’ (Paul 1996)

Taken together, the data provided in this section show that the patterns of N-bonding in the nominal domain mirror those described in the verbal domain from Section 3.1 above. To summarize the discussion so far, N-bonding occurs across the verbal and nominal domains in Malagasy and is found between a non-Agent Voice verb and following non-trigger agent, a possessee and possessor, and between certain prepositions and adjectives and their complements. Importantly, these are all environments that are descriptively genitive. All of these facts, I argue, can be explained under a licensing approach.

4 Structure and licensing in Malagasy

I propose that N-bonding arises as a reflection of a particular syntactic environment, namely one in which a nominal cannot be structurally licensed, and that this occurs in Malagasy due to the absence of a dedicated abstract case for external arguments, in combination with details of the voice system, discussed below. I begin by outlining the basic clausal structure of Malagasy in Section 4.1. In Sections 4.2 and 4.3, I establish the distribution of voice morphemes and present the assumptions regarding structural licensing within the proposed structure. I will then show that the absence of abstract case for external arguments results in the possibility of a nominal remaining unlicensed at spell-out. I review the implications of this limitation in structural licensing in Section 5. Following previous analyses, I provide an overview of an alternative licensing strategy, namely Local Dislocation, a post-syntactic operation which creates the conditions necessary for N-bonding in Malagasy.

4.1 Malagasy clause structure

I start by outlining the basic clausal structure of Malagasy, with the assumption that there are only two structural licensors in the language: CT0 and v/Voice0. In Section 4.1.1, I propose a joint CT0 in Malagasy, a high functional head responsible for hosting an Ā-featured DP in its specifier and assigning it nominative case. This follows from previous proposals such as those by Aldridge (2004; 2021), Legate (2014), and Erlewine (2018). In Section 4.1.2, I show that deriving the right outcomes of movement to trigger position relies on a lower functional head, namely v/Voice0, the head responsible for merging the external argument and assigning accusative case. I return to the implications of such licensing patterns in Section 4.3.

4.1.1 The Malagasy trigger in Spec,CTP

Recall that each clause in Malagasy contains a trigger, a referentially prominent DP which is tied to the particular voice of the clause and occurs in clause-final position. Examples are given in (21), where the trigger is underlined.

- (21)

- a.

- M-an-didy

- av-pfx-cut

- ny

- det

- trondro

- fish

- ny

- det

- vavy.

- girl

- ‘The girl cuts the fish.’

- b.

- Didi-a(n)-n’-ny

- cut-pv-n-det

- vavy

- girl

- ny

- det

- trondro.

- fish

- ‘The fish is cut by the girl.’

- c.

- An-didi-a(n)-n’-ilay

- pfx-cut-cv-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- ny

- det

- trondro

- fish

- ny

- det

- antsy.

- knife

- ‘The knife is used by that girl to cut the fish.’

Following the intuition that the trigger picks out what the sentence is about (for discussion see e.g. Pearson 2005; Chen 2017; Hsieh 2020), I assume that the trigger is predetermined by information structural considerations and bears a discourse-motivated Ā-feature. This feature is then probed by a higher functional head, prompting movement to trigger position.12

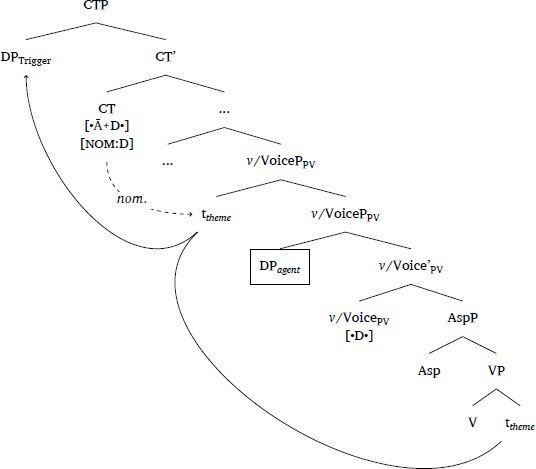

Much discussion in the Austronesian literature has centered around whether the trigger, the agent, or both/neither constitutes the grammatical subject of the sentence. I adopt an analysis similar to that of Guilfoyle, Hung, and Travis (1992) wherein the ‘subject’ function is associated with both the trigger and the agent. Following Guilfoyle et al., I assume that the agent is generated in a vP-internal subject position, a position associated with the thematic and binding properties of subjects. The trigger is located in the nominative case position, a position associated with the case- and extraction-related properties of subjects. Following previous work (e.g. Aldridge 2004; Rackowski & Richards 2005; among others), I assume that structural nominative case is assigned in Malagasy by a high functional head to the trigger.

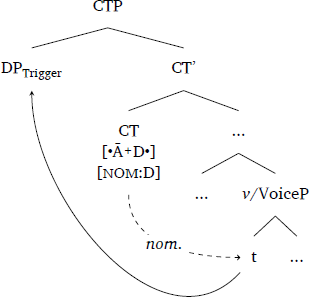

- (22)

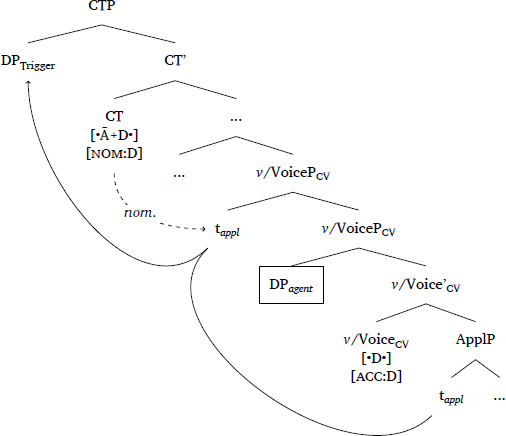

Although it is common across many languages for C0 (complementizer) and T0 (tense) to be independent from one another, with C0 bearing the responsibility of fulfilling information-structural Ā-movement and T0 being associated with A-movement and properties of subjects (Chomsky 1986; among others), this sharp division between C0 and T0 is not as apparent in Austronesian languages exhibiting voice systems that interact with extraction asymmetries. I assume that in Malagasy C0 and T0 are bundled into a single head, which I call CT0 following Martinović (2015; 2017) (see also Legate 2014; Aldridge 2017; and Erlewine 2018 which discuss the application of a joint CT0 in other Austronesian languages). This CT0 raises the highest Ā-bearing DP in its c-command domain to its specifier and assigns it nominative case, as illustrated in (22). I will show that the responsibility of ensuring that the trigger DP will be the target for this movement to Spec,CTP lies with a lower functional head, namely v/Voice0, which I discuss in Section 4.1.2. Some analyses place the trigger in a specifier position to the right of the head which projects it (see Guilfoyle et al. 1992; Pearson 2005). The current analysis does not depend on whether this Spec position is to the left or right. To obtain the correct surface order for the structures proposed in this paper, I assume a predicate-fronting analysis as proposed by Pearson (1998), Rackowski & Travis (2000), Travis (2005), among others, not represented in the trees for simplicity.

For the current analysis, I assume that movement and Case assignment occur as a result of probe-goal relationships between functional heads and target nominals (Chomsky 2001) (see also Erlewine 2018 for a similar account of probing in Toba Batak). Functional heads are merged with features which constitute probes that search their c-command domain for a goal with matching features. When a probe finds a goal, it enters into an Agree relationship with it. The CT0 in Malagasy has a [nom:D] feature, for nominative case assignment, and a movement-triggering feature (standardly proposed to be an [EPP] feature associated with Ā-features of C0 or A-features of T0). I propose that this movement-triggering feature on CT0 probes for the highest target that simultaneously bears Ā- and D-features (see Coon et al. 2021 and Scott 2021 for a formal implementation of such a probe).13 I represent this feature as [•Ā+D•] (notation adapted from Adger 2003; Sternefeld 2006; Heck & Muller 2007; Georgi 2017; Branan & Erlewine to appear). Exactly how the features are organized within the shared CT0 is not essential to this analysis and will not be discussed in detail (but see Coon & Bale 2014; Deal 2015; van Urk 2015; Erlewine 2018; Scott 2021; Coon et al. 2021 for further discussion regarding probing for combinations of features). What is crucial to the present analysis is that there exists a single high functional head in the structure that can do the work of both C0 and T0, namely moving an argument to its specifier and assigning the argument structural nominative case.

The proposal of a joint head stems from the Feature Inheritance approach (Chomsky 2005; 2008; Richards 2007; Ouali 2008; Legate 2011; Coon et al. 2021; among others) which proposes that all features associated with C0 and T0 start on one head and are then spread over a larger amount of structure. Along the same lines, according to Martinović’s (2015) theory of CT head-splitting, C0 and T0 begin the derivation as a single head, CT0, which splits under certain circumstances. For example, Martinović (2019) argues that the CT0 in Wolof can remain unified for V-raising clauses but must split for wh-raising clauses to account for differences in available subject positions. Erlewine (2018) claims that a bundled CT0 head is used in Toba Batak to front nominal wh-phrases and focused nominals. Additionally, Aldridge (2021) proposes that the patterns of DP extraction in Tagalog, and Austronesian languages more generally, can be explained under a feature inheritance approach. More specifically, Aldridge argues that a lack of CT-inheritance leads to a competition between subjects and other DPs for a single specifier position of CTP. Following these accounts, I propose that a bundled CT0 approach can similarly be used in Malagasy.

Support for this single specifier position of CTP comes from wh-questions and voice morphology. In Malagasy wh-questions, the wh-phrase typically surfaces in clause-initial position (Paul 2000; Potsdam 2006). This pattern is shown in (23), where the wh-phrase is clause-initial and followed by the focus particle no (Pearson 2005). When an agent is questioned, the verb must appear in AV form (23a), when the theme is questioned, the verb appears in PV form (23b), and when a DP other than the agent or theme is questioned, the verb appears in CV form (23c).

- (23)

- a.

- Iza

- who

- no

- foc

- mamono

- av.kill

- ny

- det

- akoho

- chicken

- amin’-ny

- prep-det

- antsy?

- knife

- ‘Who is killing the chickens with the knife?’

- b.

- Inona

- what

- no

- foc

- vonoin’-ny

- pv.kill-det

- mpamboly

- farmer

- amin’-ny

- prep-det

- antsy?

- knife

- ‘What is the farmer killing with the knife?’

- c.

- Inona

- what

- no

- foc

- amonoan’-ny

- cv.kill-det

- mpamboly

- farmer

- ny

- det

- akoho?

- chicken

- ‘What is the farmer killing the chicken with?’

Alternatively, Malagasy wh-phrases can stay in-situ. When this occurs, the verb reflects regular AV, PV, and CV morphology with the non-wh-argument that has moved to trigger position, as in (24). In Malagasy, every clause must contain either a trigger or a focused DP, but, as (25) shows, the two cannot co-occur (Pearson 2005).

- (24)

- a.

- Nividy

- pst.av.buy

- inona

- what

- Rabe?

- Rabe

- ‘Rabe bought what?’

- b.

- Nividy

- pst.av.buy

- ny

- det

- vary

- rice

- taiza

- where

- Rabe?

- Rabe

- ‘Rabe bought the rice where?’ (Sabel 2003)

- (25) *

- Inona

- what

- no

- foc

- mamono

- av.kill

- amin’-ny

- with-det

- antsy

- knife

- ny

- det

- mpamboly?

- farmer

- Intended: ‘What is the farmer killing with the knife?’

Adopting proposals by Paul (2001; 2003), Pearson (1996; 2005), and Potsdam (2006), I assume that Malagasy wh-questions are pseudocleft structures that involve movement of a null wh-operator.14 Crucially, these wh-operators must be licensed in Spec,CTP. Thus, following Pearson (2005), I assume that the trigger in Malagasy is an Ā-element and is mutually exclusive with wh-operator movement within a clause because the trigger and operator compete for the same landing site, namely Spec,CTP. I take this as support for a bundled CT0 which raises either the trigger or a wh-operator. I also assume, following Pearson (2005), that in order to capture the presence of a trigger (or clause-initial wh-DP) in every clause, the specifier position of this bundled CT0 must be filled in Malagasy.

As mentioned earlier in Section 2, the thematic role of the trigger is reflected in the voice morphology that appears on the verb. Thus we expect the argument that participates in this movement to Spec,CTP (i.e. trigger position) to differ in tandem with the voice of the clause. In the following section, I will illustrate that these different outcomes occur as a result of the properties of a lower v/Voice0, the functional head responsible for merging an external argument and assigning accusative case to the theme (see e.g. Legate 2014; Harley 2017).

4.1.2 v/Voice

I assume that Malagasy exhibits different flavours of a bundled v/Voice0, following proposals by Pylkkänen (2008) and Harley (2017). That is, rather than a division of labour between separated v0 and Voice0, I assume the bundled v/Voice0 bears the responsibility of introducing an external argument, assigning accusative case, and raising an argument to its outer specifier position. I argue that it is the different combinations of these functions of v/Voice0 that derive the correct patterns of voice morphology, movement to trigger position, and Case assignment in Malagasy.

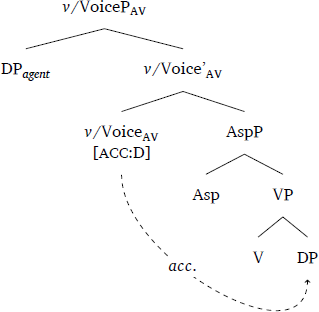

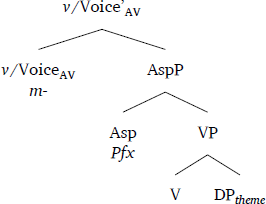

Across the three voices, v/Voice0 introduces an external argument. I assume this is the result of a Merge feature [•D•], which I do not include in the structures for simplicity. In an AV clause, the agent DP is the referentially prominent argument and is merged in Spec,v/VoiceP, bearing an Ā-feature. I further assume that v/VoiceAV has a Case-licensing feature which assigns accusative case to the structurally closest DP argument. In an AV sentence, the goal for this probe will be the internal argument. The features on v/VoiceAV are illustrated in (26). After merging the external argument in its specifier, v/VoiceAV assigns accusative case to the internal argument, discharging [acc:D].15

- (26)

- v/VoiceAV assigns accusative case to internal argument

In an AV clause, the agent is the highest DP with both Ā- and D-features. Therefore, following the assumptions described above, once CT0 merges, the features on CT0 will Agree with the agent DP, assign it nominative case, and raise it to Spec,CTP to become the trigger (as illustrated in (22)).

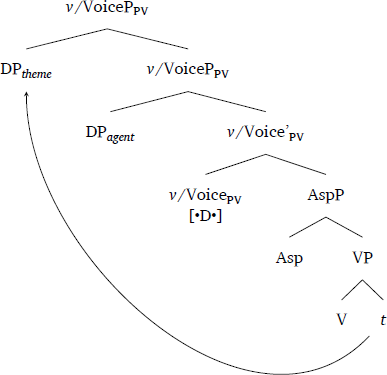

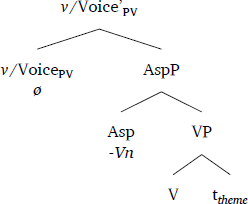

I turn next to PV. Unlike v/VoiceAV, I propose that the v/Voice0 in PV (v/VoicePV) cannot assign accusative case to the internal argument (see Legate 2014 for a similar analysis of Acehnese Object Voice). Instead, v/VoicePV bears two Merge [•D•] feaures: one merges the external argument and the other triggers movement of the closest DP in its c-command domain to the outer specifier position, above the agent. In PV, the internal argument is the referentially prominent DP and is the highest DP in the c-command domain of v/Voice0PV. Thus the internal argument will raise to the outer specifier position of v/VoiceP and will be the highest DP in the clause, as shown in (27).16

- (27)

- v/VoicePV raises internal argument to outer specifier position

Therefore in a PV sentence, once CT0 merges, the [•Ā+D•] feature on CT0 will Agree with the theme DP, assign it nominative case, and raise it to Spec,CTP to become the trigger.

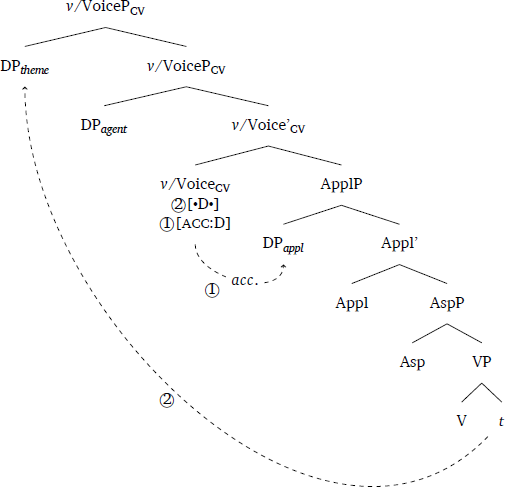

Finally, I turn to CV which displays a combination of AV and PV v/Voice0 properties. That is, v/VoiceCV behaves like v/VoiceAV in that it is able to assign accusative case to the theme, but is like v/VoicePV in that it has a movement-triggering feature [•D•]. Since it is the applied argument that must raise to trigger position, the [•D•] feature on v/VoiceCV must first raise the applied argument to its outer specifier position. Evidence from binding in Malagasy shows that the applied argument c-commands the internal argument but is still lower than the agent (see Travis 1988). I thus assume that the applied argument is in the specifier of an Applicative Phrase (ApplP) that merges directly below v/VoiceP.

From this position, the applied argument will raise to the outer Spec,v/VoiceP position. Once the applied argument has raised, v/VoiceCV will agree with the internal argument and assign it structural accusative case. Finally, upon merge of CT0, the [•Ā+D•] feature on CT0 will Agree with the applied argument, assign it nominative case, and raise it to Spec,CTP to become the trigger, in the same way as agents in AV sentences and themes in PV sentences. The lower structure of a CV sentence is shown in (28).

Note that this ApplP projection appears only in CV constructions to host applied arguments which are otherwise general PP arguments in AV and PV counterparts. Hsieh (2020) makes a similar proposal for Tagalog wherein peripheral arguments are introduced into the derivation as applied objects only if they later become the trigger and are otherwise general PP arguments (see also Rackowski 2002; Nie 2019).

- (28)

- v/VoiceCV raises applied argument to its specifier then assigns accusative case to the internal argument

It’s important to note that the movement-triggering feature [•D•] and Case-licensing feature [acc:D] on v/VoiceCV must probe in the order specified above to make correct predictions for the language. Under economy conditions, it may seem ideal for v/VoiceCV to be able to assign accusative case and move an argument to its outer specifier position in one operation (i.e. with a single Agree relation). In other words, it is desirable to minimize the number of operations that take place, an idea in line with proposals such as the Feature Maximality constraint (Longenbaugh 2019) or Multitasking condition (van Urk & Richards 2015). However, if movement is tied to case assignment, then the applied argument being the highest nominal under v/VoiceCV would be the sole goal, robbing the internal argument of the opportunity to receive structural accusative case.

Alternatively, if these operations took place independently from one another but occurred in the wrong order (i.e. if v/VoiceCV could assign accusative case before moving an argument to its outer specifier position), the applied argument would be the goal for the [acc:D] feature on v/VoiceCV. Then, assuming that a nominal can only enter into a single Agree relationship, the internal argument would be the only remaining goal for the movement-triggering [•D•] feature on v/VoiceCV and will consequently raise above both the applied argument and the agent. Two problems arise in this situation. First, in a CV clause, the internal argument is not the referentially-prominent DP. Therefore, when CT0 merges, it will not find a matching goal and the internal argument would not raise to Spec,CTP to receive nominative case and hold trigger status. Second, this would block the applied argument from ever becoming the trigger and incorrectly predicts that circumstantial voice sentences are not possible in the language. A structure with the incorrect ordering of features is schematized in (29).

- (29)

- v/VoiceCV incorrectly assigns accusative case to applied argument

Such economy principles must therefore be sensitive to other needs of the derivation. In this case it is the requirement for nominals to be licensed and the requirement for Spec,CTP to be filled which must be satisfied. We can achieve the desired outcome by specifying an order of feature-probing (see also Georgi 2017 for discussion on the effects of relative ordering of Merge and Agree) or by asserting that only the proposed order will result in a converging derivation. A similar proposal has been made by Newman (2020) for theta role assignment.

A summary of the features on the different v/Voice heads is provided in (30). v/VoiceAV assigns accusative case to the internal argument and does not raise an argument to its outer specifier position. v/VoicePV cannot assign accusative case but does raise an argument to its outer specifier position. v/VoiceCV is a combination of both v/VoiceAV and v/VoicePV in that it assigns accusative case to the internal argument and raises an argument (i.e. the applied argument) to its outer specifier position. The organization of these features determine the spell-out of v/Voice0, described next.

- (30)

- Distribution of Movement-triggering and Case-licensing probes on v/Voice

Voice [•D•] [Case] v/VoiceAV ✖ ✔ v/VoicePV ✔ ✖ v/VoiceCV ✔ ✔

4.2 Spelling out voice morphology

With the clausal structure outlined above, we can connect the properties of v/Voice0 with the different voice morphemes in Malagasy. Recall the voice morpheme distribution repeated in Table 3. In AV the verb takes the AV prefix m- and a verbal prefix (e.g. aN-). I propose that the AV prefix m- is realized on v/VoiceAV, reflecting the absence of the movement-triggering [•D•] feature. In contrast, when there is such a feature on v/Voice0 (i.e. in PV and CV), v/Voice0 is null.

Malagasy verb template and voice morphemes.

| Voice | Template | Root | Surface Form |

| Agent Voice | m- Pfx- ROOT |

didy hira |

m-an-didy m-i-hira |

| Patient Voice |

a- ROOT voa- ROOT ROOT -Vn |

tao didy didy voha |

a-tao voa-didy didi-an voha-in |

| Circumstantial Voice | Pfx- ROOT -an |

didy vidy |

an-didi-an i-vidi-an |

Following Pearson (2005), I assume that the verbal prefixes are realized on the same head as the PV affixes: Asp.17 When the theme moves out of the complement of Asp0, Asp0 is spelled out as a PV affix. Otherwise, Asp0 is spelled out as a verbal prefix.18 Following Pearson (2005), I assume the CV suffix -an is the spell-out of the Appl0. As traditionally assumed, all affixes combine with the verb root as it raises via successive head movement. Following Travis (1994; 2006) I assume that verb movement in Malagasy is contained within the heads that are event related and therefore the verb moves only as far as E0, an event related functional head situated between CTP and vP which defines the edge of an event (see Travis 1994 for more discussion on E0).19 AV and PV structures with the corresponding voice morphemes are shown in (31).

- (31)

- a.

- Agent Voice

- b.

- Patient Voice

The observation that Appl0 is spelled out as -an only when the applied argument raises out of the specifier position of ApplP, can be explained under a generalized version of the Doubly-Filled Comp Filter, as in (32) (following Sportiche 1992; Koopman & Szabolcsi 2000; Pearson 2005).

- (32)

- Doubly-Filled Comp Filter

- If H is a category containing some feature F, *[HP XP [H’ H0…]] when XP and H0 both overtly encode F.

The spell-out of v/Voice0, Asp0, and Appl0 for each of the three voices is summarized in Table 4. In AV, there is no movement-triggering feature on v/Voice0, resulting in the spell out of v/Voice0 as the AV prefix m-. In contrast, the movement-triggering feature is present on v/Voice0 in both PV and CV, resulting in the spell-out of a null v/Voice0. Verbal prefixes are spelled out on Asp0 in AV and CV when the theme remains within the complement of Asp0. In PV, on the other hand, when the theme is raised due to the [•D•] feature on v/VoicePV, Asp0 is spelled out as a PV affix. Lastly, the CV suffix -an is the spell out of Appl0 (projected only in CV), when the applied argument raises.

Spell-out of Malagasy voice morphemes.

| Voice | v/Voice0 | Asp0 | Appl0 |

| Agent Voice | m- | Pfx | |

| Patient Voice | ø- | a-/-Vn | |

| Circumstantial Voice | ø- | Pfx | -an |

In the next section I explain how these assumptions regarding the structural organization and licensing constraints in the language lead to N-bonding.

4.3 Case and licensing in Malagasy

4.3.1 Licensing in the verbal domain

I assume that Malagasy complies with the Case Filter (see Vergnaud 1977/2008; Chomsky 1980; 1981), a requirement that all nominals receive Case. When we consider the availability of structural nominative and accusative case from CT0 and v/Voice0, respectively, the main properties that underlie the process of N-bonding emerge. With nominative case being available only to the trigger DP and accusative case being available to the internal argument, any DP argument that is not in one of those two positions is left unlicensed. Crucially, I propose that v/Voice0 in Malagasy is unable to license an argument in its specifier. In other words, there is no inherent ergative case assignment available in Malagasy like there is in some other languages (see e.g. Massam 2006 on Niuean; Aldridge 2008 on Tagalog; Legate 2014 on Acehnese; and Legate 2008 on inherent ergative more generally). Therefore, in-situ agents that are merged in Spec,v/VoiceP and do not raise to trigger position cannot be licensed by any of the structural mechanisms available in the language. This occurs in sentences when a DP other than the agent raises to trigger position (i.e. PV and CV sentences), which are the same types of sentences in which we observe N-bonding. The structure of a PV sentence is illustrated in (33) highlighting the in-situ agent that cannot be licensed in its structural position. The structure in (34) shows the same restriction in a CV sentence.

- (33)

- Non-trigger agent in PV clause cannot be structurally licensed

- (34)

- Non-trigger agent in CV clause cannot be structurally licensed

When we consider the patterns of N-bonding in the verbal domain within the current proposal of structural licensing in Malagasy, we see that the arguments that do not receive structural case are exactly the arguments that undergo N-bonding. In the following section I extend this analysis to the nominal domain.

4.3.2 Licensing in the nominal domain

As just described for the verbal domain, under the current analysis the only types of structural case assignment that are available in Malagasy are nominative and accusative, with the result being that N-bonding occurs when a nominal cannot receive either one. In Section 3.2 we saw the presence of N-bonding in the nominal domain in constructions described as being ‘genitive’. In these constructions, N-bonding appears between a possessor and possessee, and in some cases between a preposition or adjective and its complement. The data is repeated in (35).

- (35)

- a.

- Possessee + Possessor

- trano-n’-ilay

- house-n-dem

- olona

- person

- ‘that person’s house’ (Keenan & Polinsky 1998)

- b.

- Prep + Complement

- ami-n-ilay

- prep-n-dem

- seza

- chair

- ‘on that chair’ (Pearson 2005)

- c.

- Adj + Complement

- mainti-n’-ny

- black-n-det

- molaly

- soot

- ‘blackened by (the) soot’ (Paul 1996)

If we extend the same licensing proposal of N-bonding from the verbal domain to the nominal domain, we predict that the bonded elements in (35) do not reflect genitive case assignment but rather a lack thereof. I take the case of prepositions as an example. If we assume that the language possesses only abstract nominative and accusative case, we can reframe the distribution of nominal complements to prepositions as follows: some prepositions assign nominative case, as in (36) for the preposition noho ‘because of’. Other prepositions assign accusative case, as shown in (37) for the preposition lavatra ‘far from’. Yet other prepositions do not assign case at all, as seen in (38) for the preposition aloha ‘in front of’. I propose that N-bonding occurs only when the preposition does not assign case.

- (36)

- Preposition + nominative marked nominal

- a.

- noho

- because.of

- izy

- 3sg.nom

- ‘because of him/her’

- b.

- Vaky

- broken

- ny

- det

- vilia

- plate

- noho

- because.of

- ilay

- dem

- zaza.

- child

- ‘The plate is broken because of that child.’

- (37)

- Preposition + accusative marked nominal

- a.

- lavitra

- far.from

- azy

- 3sg.acc

- ‘far from him/her’

- b.

- Mipetraka

- av.live

- lavitra

- far.from

- ny

- det

- tsena

- market

- ny

- det

- vavy.

- girl

- ‘The girl lives far from the market.’

- (38)

- Preposition + unmarked nominal

- aloha-n’-ny

- in.front-n-det

- fiara

- car

- ‘in front of the car’

We can take the same approach for adjectives which show variation between nominals that are marked for accusative case and nominals that are unmarked for case. Examples are repeated in (39) and (40). As illustrated, N-bonding occurs only when the nominal appears without accusative case (40).

- (39)

- Adjective + accusative marked nominal

- a.

- antra

- compassionate

- olona

- person.acc

- ‘compassionate to people’

- b.

- tsara

- good

- ho

- prep

- azy

- 3sg.acc

- ‘good for him’

- (40)

- Adjective + unmarked nominal

- mainti-n’-ny

- black-n-det

- molaly

- soot

- ‘blackened by soot’ (Paul 1996)

Moreover, this analysis is easily applied to the possessive construction, which is described as being expressed in Malagasy using the ‘genitive construction’ (Paul 1996). An example is repeated in (41) illustrating the presence of N-bonding in the possessive construction. If abstract genitive case is not available in the language, then the observation that possessive constructions also show N-bonding is explained.

- (41)

- Possessee + Possessor

- trano-n’-ilay

- house-n-dem

- olona

- person

- ‘that person’s house’ (Keenan & Polinsky 1998)

In sum, N-bonding reflects a construction in which a nominal cannot receive nominative or accusative case. Moreover, these patterns reflect a more general property of the language, namely that it lacks abstract genitive case. Further support for this analysis is found in the distribution of pronouns in Malagasy, which I turn to next.

4.3.3 Reassessing Malagasy pronouns

Thus far, we have seen that N-bonding occurs consistently with nominals. In this section, I will show that the same analysis can be extended to pronouns. Moreover, reviewing the distribution of pronouns under an N-bonding lens allows us to simplify the pronominal paradigm in Malagasy. Specifically, I will argue that ‘nominative’ and ‘genitive’ forms can be collapsed into a single pronoun series that is unmarked for case. I will further show that N-bonding easily accounts for the variation observed within the ‘genitive’ series.

Traditional descriptions of Malagasy pronouns generally assume that the language shows three distinct cases: nominative, accusative, and genitive (Keenan 1976; Voskuil 1993; among others), as displayed in Table 5. The nominative forms are usually used when the pronoun functions as the trigger, as in (42), while the accusative forms are used when the pronoun is a predicate-internal theme, as in (43). Lastly, the genitive forms are used more widely, encoding both non-trigger agents (44a) and pronominal possessors (44b) (Pearson 2005). The genitive pronouns are also used in the complement position of certain adjectives and prepositions, as described above.

Malagasy pronoun series.

| Nominative | Accusative | Genitive | |

| 1st SG | izaho, aho | ahy | -ko/-o |

| 2nd SG | ianao | anao | -nao/-ao |

| 3rd SG | izy | azy | -ny/-y |

| 1st PL Incl | isika | antsika | -ntsika/-tsika |

| 1st PL Excl | izahay | anay | -nay/-ay |

| 2nd PL | ianareo | anareo | -nareo/-areo |

| 3rd PL | izy (ireo) | azy (ireo) | -ny/izy ireo |

- (42)

- Nominative Pronoun

- a.

- Namangy

- pst.av.visit

- ny

- det

- ankizy

- children

- izy.

- 3nom

- ‘He/she/they visited the children.’

- b.

- Novangian’

- pst.pv.visit.n

- ny

- det

- ankizy

- children

- izy.

- 3nom

- ‘He/she/they were visited by the children.’

- (43)

- Accusative Pronoun

- a.

- Namangy

- pst.av.visit

- azy

- 3acc

- ny

- det

- ankizy.

- children

- ‘The children visited him/her/them.’

- b.

- Mieritreritra

- prs.av.think

- anao

- 2acc

- aho.

- 1nom

- ‘I am thinking of you.’

- (44)

- Genitive Pronoun

- a.

- Novangia-ny

- pst.pv.visit-3gen

- ny

- det

- ankizy.

- children

- ‘The children were visited by him/her/them.’

- b.

- ny

- det

- trano-ny

- house-3gen

- ‘his/her/their house’

However, it has been observed that the nominative forms have a wider distribution than previously described. While the distribution of the pronoun forms remains to be explained, I will show that N-bonding occurs consistently in the expected environments (e.g. between a verb and a following non-trigger agent), regardless of the form of the pronoun. Following Pearson (2005), I take this variability as potential evidence that the nominative and genitive pronominal forms do not spell out abstract case features.

Examples outlining some of the variability that has been observed in previous literature regarding the use of nominative and genitive pronominal forms are provided in (45)–(47) (Zribi-Hertz & Mbolatianavalona 1999; Pearson 2005). With post-verbal agents, a position in which we expect to find the genitive form, as illustrated in (45), the nominative form can be found when the pronoun is coordinated with another DP (46a), followed by the restrictive modifier irery ‘only/alone’ (46b), or when the pronoun is modified (e.g. by the verb mivady ‘be married’) (46c).20

- (45)

- Post-verbal agent with genitive pronoun

- Nojere-ny

- pst.pv.watch-3gen

- tany

- there

- antokotany

- garden

- i

- det

- Koto.

- Koto

- ‘He/she/they watched Koto in the garden.’

- (46)

- Post-verbal agent with nominative pronoun

- a.

- Hita-n’-izaho

- pst.pv.see-n-1nom

- sy

- and

- ny

- det

- zaza

- child

- tany

- there

- antokotany

- garden

- i

- det

- Koto.

- Koto

- ‘I and the child watched Koto in the garden.’

- b.

- Jere-n’-ianao

- prs.pv-n-2nom

- irery

- alone

- ilay

- dem

- alika.

- dog

- ‘This dog is being watched by you alone.’

- c.

- Nojere-n’-izy

- pst.pv.watch-n-3nom

- mivady

- av.married

- tany

- there

- antokotany

- garden

- i

- det

- Koto.

- Koto

- ‘They, the married couple, watched Koto in the garden.’

Note that the nominative pronouns in (46) cannot be replaced with their corresponding genitive forms, as shown in (47a) and (47b). In direct contrast, (47c) and (47d) illustrate a case in which the genitive form is instead required. Thus the nominative and genitive pronominal forms do not follow a strict complementary distribution. One possibility is to instead think of this alternation between ‘nominative’ (or free) and ‘genitive’ (or bound) forms as being determined by certain discourse- and other related factors.21

- (47)

- Coordination and modification with genitive pronoun

- a.

- *Nojere-ko

- pst.pv.watch-1gen

- sy

- and

- ny

- det

- zaza

- child

- tany

- there

- antokotany

- garden

- i

- det

- Koto.

- Koto

- Intended: ‘I and the child watched Koto in the garden.’

- b.

- *Nojere-ny

- pst.pv.watch-3gen

- sy

- and

- ny

- det

- zaza

- child

- tany

- there

- antokotany

- garden

- i

- det

- Koto.

- Koto

- ‘He/she and the child watched Koto in the garden.’

- c.

- *Nojeren’ianareo

- pst.pv.watch-n-2pl.nom

- sy

- and

- ny

- det

- zaza

- child

- tany

- there

- antokotany

- garden

- i

- det

- Koto.

- Koto

- Intended: ‘You all and the child watched Koto in the garden.’

- d.

- Nojere-nareo

- pst.pv.watch-2pl.gen

- sy

- and

- ny

- det

- zaza

- child

- tany

- there

- antokotany

- garden

- i

- det

- Koto.

- Koto

- ‘You all and the child watched Koto in the garden.’

Crucially, in environments where we expect N-bonding to occur, the N-bonding process behaves systematically regardless of the form of the following pronoun. This supports the idea that the post-verbal agent, regardless of its morphological form, has not been assigned abstract case. Given these assumptions, we can reduce the pronominal paradigm in Malagasy to two series: the first is marked for accusative case and is used for predicate-internal themes, as in the traditional analysis, and the second is unmarked for case and has the free/bound alternation as described above. A revised representation of the pronominal paradigm is produced in Table 6.

Malagasy pronoun series: interim revision.

| Accusative | Unmarked | ||

| Free | Bound | ||

| 1st SG | ahy | izaho, aho | -ko/-o |

| 2nd SG | anao | ianao | -nao/-ao |

| 3rd SG | azy | izy | -ny/-y |

| 1st PL Incl | antsika | isika | -ntsika/-tsika |

| 1st PL Excl | anay | izahay | -nay/-ay |

| 2nd PL | anareo | ianareo | -nareo/-areo |

| 3rd PL | azy (ireo) | izy (ireo) | -ny/izy ireo |

When we consider the surface forms of the pronouns with N-bonding in mind, we can simplify the pronominal paradigm in Malagasy even further. The clitic pronoun series is traditionally described as showing contextually-determined allomorphy (as shown in Table 6). With the exception of the first person pronoun, the two forms of clitic pronouns can be derived from one another; each pronoun either includes or lacks an initial n segment.22 This allomorphy is described as being dependent on preceding phonological context such that the initial n is absent when the preceding segment is a non-continuant consonant, and is otherwise present. If we reanalyze this initial n segment as being the N-bonding element, the presence of the n segment is independently motivated and the variation among the clitic pronouns is easily explained. In Malagasy, there exists only one series of clitic pronouns (the forms without the initial n) and these pronouns are always in a position to undergo N-bonding. A final representation of the pronominal paradigm is produced in Table 7.

Malagasy pronoun series revised.

| Accusative | Unmarked Free/Bound | |

| 1st SG | ahy | izaho, aho/-ko |

| 2nd SG | anao | ianao/-ao |

| 3rd SG | azy | izy/-y |

| 1st PL Incl | antsika | isika/-tsika |

| 1st PL Excl | anay | izahay/-ay |

| 2nd PL | anareo | ianareo/-areo |

| 3rd PL | azy (ireo) | izy (ireo)/-y |

The variation between the presence and absence of the N-bonding element on the surface reflects syllable structure constraints in the language more generally, which I return to in Section 5. Under the current approach we largely obviate the need for contextually-determined allomorphy of the clitic pronouns and are able to achieve a systematic pronominal paradigm within the language.

4.4 Interim summary

In Section 3, I presented the distribution of N-bonding across the verbal and nominal domains in Malagasy. I then outlined the proposed clausal structure for the language in Section 4, tying the N-bonding observations to licensing constraints. Specifically, I proposed that Malagasy has only two structural licensors: CT0 and v/Voice0, which are responsible for assigning nominative and accusative case, respectively. The constructions in which we find N-bonding all contain a nominal that cannot be structurally licensed due to the absence of abstract genitive case in Malagasy. This analysis was further supported by the distribution of the pronominal forms in the language (Pearson 2005). Having established the syntactic conditions that underlie N-bonding, I turn next to an account of the post-syntactic operations that are involved in its derivation.

5 Deriving N-bonding post-syntactically

In this section I present N-bonding as the result of two independent morpho-phonological operations that produce (i) the ‘bonding’ configuration and (ii) the insertion of /n/ as the bonding element. In Section 5.1, I present an analysis of ‘bonding’ as a result of Local Dislocation, a post-syntactic operation required to satisfy the Case Filter in Malagasy. Section 5.2 provides further evidence from Malagasy compounds to support this analysis. I will then argue in Section 5.3 that the result of Local Dislocation feeds an independent language-specific operation which inserts the N-bonding element. Section 5.4 provides an analysis of the N-bonding element as a bundle of features to account for the observed phonological variation.

5.1 N-bonding as a result of Local Dislocation

Recall from Section 4 that the deficiency of structural licensing in Malagasy leaves nominals in certain constructions unlicensed. If Malagasy complies with the Case Filter, defined as requiring all nominals to receive Case within the syntactic derivation, then the analysis thus far suggests that the Case Filter is violated in Malagasy. Following Levin (2015), I assume that languages can make use of post-syntactic licensing strategies and that we can maintain a version of the Case Filter by appealing to the proposal that the Case Filter is satisfied not at the end of the syntactic derivation, but later along the PF branch.

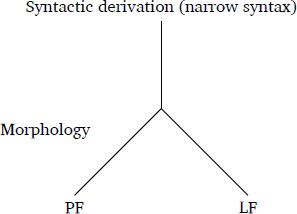

Before turning to the operations that are required to derive the account, I first spell out my assumptions about the overall structure of the grammar. I assume a conventional Y-model as illustrated in (48):

- (48)

Once completed, the syntactic derivation is sent to Phonological Form and Logical Form. Following the Distributed Morphology framework (Halle 1990; Halle & Marantz 1993; and much subsequent work) I assume that Morphology represents a set of processes along the PF branch which interpret the output of the syntactic derivation (Embick & Noyer 2001). See Embick and Noyer (2001) for a detailed breakdown of proposed operations that take place along the PF branch. The operation relevant for the discussion of N-bonding in Malagasy is Local Dislocation, which I turn to next.

Embick & Noyer (2001) developed Local Dislocation as a variety of Merger, or Morphological Merger, as first proposed by Marantz (1988) (see Embick & Noyer 2001 for detailed discussion on the development of this operation).23 Local Dislocation is an operation that combines two linearly adjacent terminal nodes to create a complex atomic head (Embick & Noyer 2001; 2007).24 This adjunction operation is schematized in (49), where X•Y denotes a requirement that X must linearly precede and be adjacent to Y.25

- (49)

- Local Dislocation schema

- X • Y → X+Y

I assume following Levin (2015) that nominal licensing can be achieved via linear (i.e. post-syntactic) adjacency. As such, the licensing needs of Malagasy can motivate the implementation of Local Dislocation in the language. More specifically, Levin proposes that adjunction by Local Dislocation allows the nominal to count as part of the verbal extended projection, which obviates the need for the nominal to be Case-licensed. See Levin (2015) for further discussion on licensing by adjacency and proposals on modifying the Case Filter. For the purposes of this analysis, we can think of Local Dislocation as a last-resort licensing mechanism along the PF branch (see Erlewine 2018 for a similar proposal for Toba Batak). This post-linearization operation is also consistent with the empirical data from Malagasy. In a non-AV sentence for example, Local Dislocation can apply to a non-Agent Voice verb and in-situ agent, which will always be linearly adjacent. An example is schematized in (50), for a non-Agent Voice verb voavoha ‘opened’ followed by a non-trigger agent ny vavy ‘the girl’.

- (50)

- Local Dislocation in the verbal domain

- a.

- [T V0] • [DP D0 … ] → [T V0 + D0] [DP … ]

- b.

- [T Voavoha] • [DP ny vavy … ] → [T Voavoha + ny] [DP vavy… ]

We can apply the same machinery to the nominal domain, as schematized in (51) for the preposition aloha ‘in front of’ and its complement ny fiara ‘the car’. Since the preposition and following nominal are linearly adjacent after spell-out, Local Dislocation can apply, rendering the nominal part of the extended projection of the preposition and thus licensed via adjacency.

- (51)

- Local Dislocation in the nominal domain

- a.

- [T P0] • [DP D0 … ] → [T P0 + D0] [DP … ]

- b.

- [T aloha] • [DP ny fiara … ] → [T aloha + ny] [DP fiara… ]

According to Levin (2015), Local Dislocation will not only result in the observed adjacency requirements (e.g. between non-Agent Voice verbs and following agents), but should also ensure that the adjacent components form a tight phonological unit at PF. Evidence from the presence of domain-internal phonological processes are compatible with this approach. For example, evidence of adjunction is found when the in-situ agent is a proper name, as in (52). In (52a), the non-Agent Voice verb novidin ‘bought’ and proper name Rabe are written as a single word, where the N-bonding element ‘n’ and following ‘r’ fuse to form the prenasalized affricate [ndr], a phonological process that otherwise only applies word-internally in Malagasy (Pearson 2005).26 Assuming that local dislocation is also at play in the nominal domain (52b), the parallel outcomes and phonological effects of ‘bonding’ (i.e. fusion) are simply a reflection of adjunction and are thus unsurprising.

- (52)

- a.

- novidi-n-dRabe

- pst.pv-buy-n-Rabe

- ‘bought by Rabe’

- b.

- ami-n-dRabe

- prep-n-Rabe

- ‘with Rabe’

Together, the empirical data is consistent with the proposal that N-bonding in Malagasy is linked to the licensing constraints of the language; N-bonding is observed in constructions where a nominal, as a result of not being structurally licensed, is post-syntactically licensed via adjunction. The licensing analysis described up to this point effectively accounts for the distribution of N-bonding and the phonological consequences are in line with the syntactic account.

5.2 Evidence from Malagasy compounds

So far, we have seen that the N-bonding element reflects the adjunction configuration created by Local Dislocation and carries no specific meaning or function other than to reflect that the adjunction operation has taken place. This provides a similar effect to that of linking elements which occur between two constituents of a compound. The -s- in Mainland Scandinavian and the -o- in Modern Greek are two examples of morphemes that are used in compounds as linking elements but are semantically empty (Josefsson 1997; Ralli 2013; among others). If the N-bonding element surfaces as a reflection of adjunction configurations more generally, then we predict the element to also occur in other head-head constructions in Malagasy, such as compounds. This prediction is borne out.

In Malagasy, a class of compounds called “linking compounds” is formed with a “linking morpheme” (Ntelitheos 2012). The structure of these compounds is also described as being parallel to the structure of possessive constructions in Malagasy (Ntelitheos 2012). The examples in (53) show that in these compound forms, the N-bonding element appears between the two nouns which are concatenated and is subject to word-level morphophonological processes of the language such as consonant mutation and prenasalization (Keenan & Razafimamonjy 1996; Paul 1996; Keenan & Polinsky 1998). For example, in (53a) the initial consonant of vava ‘mouth’ undergoes mutation from ‘v’ to ‘b’ which forms a prenasalized stop with the preceding N-bonding nasal.

- (53)

- a.

- ambi-m-bava

- excess-n-mouth

- ‘a surplus of food’

- b.

- lamba-m-baravarana

- cloth-n-window/door

- ‘curtain’

- c.

- feo-n-kira

- sound-n-song

- ‘melody’

- d.

- trano-n-kala

- house-n-spider

- ‘spider-web’

This data from compounding provides further support for the use of Local Dislocation within the language and extends the distribution of N-bonding to head-head configurations more generally.27 As a result, we can reformulate our generalization of N-bonding to a language-wide condition as stated in (54).

- (54)

- N-bonding Condition

- N-bonding occurs in head-head adjunction configurations.

5.3 The N-bonding element is a morpho-phonological ornament

Since Local Dislocation is a post-syntactic operation and is sensitive only to linear order rather than hierarchical structure, I assume that the insertion of the N-bonding element must also be post-syntactic (i.e. inserted at PF). Elements of this type are described as ornamental (Embick & Noyer 2007), such that they introduce syntactico-semantically unmotivated structure (i.e. nodes) and features which ornament the syntactic representation. In other words, any such ornamentations introduce material into the PF expression but crucially do not add or eliminate information necessary for semantic interpretation. There are two types of elements that can be added in the PF component: features and terminal nodes, as defined in (55) and (56) (Embick & Noyer 2007). These definitions do not explicitly state whether or not the dissociated feature or node is strictly syntactic. I return to this point below.

- (55)

- Dissociated Feature

- A feature is dissociated iff it is added to a node under specified conditions at PF.

- (56)

- Dissociated Node

- A node is dissociated iff it is added to a structure under specified conditions at PF.

These inserted elements are deemed dissociated, emphasizing that this material signals the presence of certain syntactic morphemes, features, or configurations, but does not itself represent the actual spell-out of these. I assume, following Embick and Noyer (2007), that the implementation of dissociated features/nodes is governed by language-specific rules. Post-syntactic insertion operations involving dissociated elements have been discussed in recent literature for compounds (see Tat 2013 on Turkish and Dolatian 2021 on Armenian), in which linking vowels/compound markers are semantically empty and are proposed to be added during phonological spell-out in PF (see also Aronoff 1994; Oltra-Massuet 1999; Ralli 2008), as discussed above for Mainland Scandinavian and Modern Greek. Post-syntactic insertion has also been discussed for Korean subject honorification, for which honorific agreement suffixes are implemented by so-called node-insertion (Choi & Harley 2019). More recently, this form of introducing a dissociated or ornamental element has been re-dubbed node-sprouting by Choi and Harley (2019), a term that more explicitly conveys that the insertion (or ‘sprouting’) of such post-syntactic material can only occur when certain conditions are met.

I propose that a similar approach can be adopted for N-bonding in Malagasy. The N-bonding element is a dissociated element and the condition necessary for its insertion is head-head adjunction, which we’ve seen can come about as a result of Local Dislocation or compounding. Extending previous interpretations of dissociated elements, I further assume that the types of dissociated elements that can be inserted, as well as the conditions in which they can sprout, are not restricted to syntactic features/conditions, but can also include phonological features/conditions. More specifically, I propose that the insertion of the N-bonding element involves the insertion of a bundle of phonological features which can sprout as different surface realizations depending on surrounding phonological context. This will correctly derive the surface representation of N-bonding and its phonological variation, which I turn to next.

5.4 Accounting for phonological variation

In order to provide a complete representation of the N-bonding element, we must first examine the variation that exists in its surface realization. This section aims to provide a brief sketch of the variation of the N-bonding element. Specifically, I will show that the N-bonding element has two possible surface representations: /n/ and /i/, and that the preceding phonological context is what determines which representation surfaces. When the N-bonding element is preceded by a non-nasal consonant, it surfaces as /i/. In all other cases, the N-bonding element surfaces as /n/.

Recall the data from (1) and (2), repeated in (57) and (58) below. The examples are similar in that they include (a) a non-Agent Voice verb and an adjacent external argument or (b) a possessee followed by a possessor—both constructions in which we expect to find N-bonding. However, the N-bonding element n is seemingly not present in (58). This is puzzling given the described distribution of N-bonding in the language. If N-bonding is indeed present in (58), then at least two questions arise: (i) is the N-bonding element realized in the surface representation of constructions like those in (58)? and (ii) how do we account for the variation in the form of the N-bonding element? In this section I will argue that the N-bonding element is indeed realized in the surface representation of constructions like those in (58) and that the N-bonding element has an underlying representation /n/ which surfaces as /i/ when it is preceded by a non-nasal consonant and as /n/ elsewhere.

- (57)

- a.

- Voa-voha-n’-ilay

- pv-open-n-dem

- vavy

- girl

- ilay

- dem

- varavarana.

- door

- ‘That door was opened by that girl.’ Non-AV + EA

- b.

- trano-n’-ilay

- house-n-dem

- olona

- person

- ‘that person’s house’ Possessee + Possessor

- (58)

- a.

- Tapaky

- pv.cut

- ny

- det

- olona

- person

- ny

- det

- tady.

- cord

- ‘The cord was cut by the person.’ Non-AV + EA

- b.

- tongotry

- foot

- ny

- det

- zaza.

- child

- ‘the child’s feet’ Possessee + Possessor