French missing object constructions (henceforth MOCs) are infinitival phrases introduced by marker à that involve a dependency between a direct object (DO) that is locally missing, but that corresponds to an external argument that the construction modifies or predicates on. An example is given in (1), in which à lire is an instance of a MOC, its antecedent noun (livre) corresponding to the missing object of the verb lire. As can be seen from the translation, such constructions can (at least in some uses) find an English equivalent in a similar phrase headed by to.

- (1)

- un

- a

- livre

- book

- à

- to

- lire

- read

- ‘a book to read’

The MOC has been treated variously as a long distance extraction, as a bounded reduced relative and as a kind of passive. In this paper we borrow insights from the last two treatments and propose an analysis as an infinitival passive with an extended but bounded locality.

In the first section we will describe the external properties of the MOC, before turning to its internal properties in Section 2. In Section 3, we present new data relating to the internal properties in the form of a corpus study on the locality of the construction. Sections 4–5 present and discuss previous analyses, and our proposal is exposed in detail in Section 6.

1 Distribution

We find four distinct contexts that license the MOC in French: attributive, subject predication, object predication, and tough contexts.

1.1 Attribute

Probably the most wide-spread use of the MOC is the attributive one, illustrated by example (1), where the MOC modifies an antecedent noun that corresponds to the missing object. This property displays some superficial similarity to infinitival relatives (Abeillé et al. 1998), as in (3). However, the two constructions differ from each other in that the subject in the MOC can be realised internal to the infinitival clause by an optional by-phrase (see (2) and Section 2.1), an option not found with infinitival relatives.

- (2)

- un

- a

- livre

- book

- à

- to

- lire

- read

- par

- by

- chaque

- every

- parent

- parent

- à

- at

- mon

- my

- avis

- opinion

- ‘a book to read by every parent in my opinion’

- (3)

- un

- a

- endroit

- place

- où

- where

- aller

- go

- pour

- to

- se détendre

- relax

- ‘a place to go to relax’

1.2 Subject predication

Similar to other attributes in French, the construction can also be used predicatively:

- (4)

- Ce

- this

- livre

- book

- est

- is

- à

- to

- lire.

- read

- ‘This book is to be read.’

This use extends to other copular verbs, e.g. sembler, and does not find an equivalent in English, as the change to a passive in the translation demonstrates.

1.3 Object predication

Predicative use of the MOC is not limited to subject predication, but it extends to object predication as well. For example, it can be used with verbs like avoir as an object predicate:

- (5)

- J’

- I

- ai

- have

- un

- a

- livre

- book

- à

- to

- lire.

- read

- ‘I have a book to read’ or ‘I have to read a book.’

- (6)

- Je

- I

- l’

- 3sg.m

- ai

- have

- à

- to

- lire.

- read

- ‘I have to read it.’

At first glance, the sentence in (5) could simply be interpreted as an attributive use of the MOC attaching to the direct object’s head noun, with the meaning ‘I have a book to read’. This is in fact one of the possible analyses of (5), which is structurally ambiguous; in (6), the alternative structure is revealed by independent pronominalisation of the DO, with the MOC left in situ. Since such pronominalisation normally targets saturated phrases and not partial NPs, this should count as robust evidence for an object predication structure. The semantics of this object predication are slightly but noticeably different: the missing object, expressed as a direct object of avoir, is not interpreted as an argument of it – that is, no possession relation need exist between the subject and the book here, and the sentence could felicitously be uttered of a book that has yet to be bought or borrowed.

Most importantly, this object predication structure comes with an additional control relation where the subject of avoir ‘have’ is interpreted as the subject of the infinitive. With other verbs displaying this object predication pattern (donner, laisser, …), however, the controller is not the matrix subject but an indirect object, as is the case in example (7).

- (7)

- Je

- I

- le

- 3sg.m

- donnerai

- will give

- à

- to

- lire

- read

- aux

- to the

- étudiant‧es

- students

- ‘I will give it for the students to read.’

This control phenomenon poses a challenge for existing accounts of the missing object construction, as any analysis will need to expose pointers to both core arguments of a MOC to be accessed by the upstairs verb. The downstairs logical object will be realised as an upstairs NP complement, while the downstairs logical subject can be controlled by some argument of the upstairs verb: avoir exerts subject control, whereas donner exerts control by means of its indirect object.

1.4 Tough constructions

Finally, the MOC appears as the complement of so-called tough adjectives, its missing object being understood to correspond to the adjective’s external argument: this will be the head noun in the case of attributive use (8), or the subject in the case of predicative use (9).

- (8)

- un

- a

- livre

- book

- facile

- easy

- à

- to

- lire

- read

- ‘a book that is easy to read’

- (9)

- Ce

- this

- livre

- book

- est

- is

- facile

- easy

- à

- to

- lire.

- read

- ‘This book is easy to read.’

Similarly to English, tough predicates are not strictly limited to adjectives, but may include (idiomatic) nominals like de la tarte ‘piece of cake’ (10a) or verbal expressions like prendre (du temps) ‘to take (time)’, coûter (une somme) ‘to cost (something)’ (10b–10c).

- (10)

- FrWaC (2010) examples (Baroni et al. 2009)

- a.

- Example from france5.fr

- un

- a

- avortement

- abortion

- c’

- it

- est

- is

- pas

- not

- de la

- part.f.sg

- tarte

- pie

- à

- to

- assumer

- take responsibility for

- ‘having had an abortion is not a piece of cake to live with’

- b.

- Example from lesverts.fr

- c’

- it

- est

- is

- le

- the

- genre

- kind

- de

- of

- renseignement

- information

- qui

- that

- prend

- takes

- du

- part.m.sg

- temps

- time

- à

- to

- obtenir

- obtain

- ‘it’s the kind of information that takes time to obtain’

- c.

- Example from hardware.fr

- Ce

- this

- GPU

- GPU

- coûte

- costs

- très

- very

- cher

- expensive

- à

- to

- fabriquer

- make

- à

- to

- Nvidia

- Nvidia

- ‘This GPU costs Nvidia a lot to produce’

- (11)

- a.

- Ce GPU coûte très cher à Nvidia à fabriquer

- b.

- Ce

- this

- GPU

- GPU

- coûte

- costs

- des

- indef.pl

- milliers

- thousands

- d’

- of

- euros

- euros

- à

- to

- fabriquer

- make

- à

- to

- Nvidia

- Nvidia

- ‘This GPU costs Nvidia thousands of euros to produce’

- c.

- *Ce

- this

- GPU

- GPU

- est

- is

- des

- indef.pl

- milliers

- thousands

- d’

- of

- euros

- euros

- à

- to

- fabriquer

- make

- (‘This GPU is worth thousands of euros to produce’)

This last example displays an additional case of control of the subject of the MOC: the tough use of verbs like coûter not only raises the missing object to subject (as do all tough predicates), but additionally licenses an indirect object controller (à Nvidia) interpreted as the subject of the infinitive. Importantly, this indirect object is a dependent of the matrix verb and not internal to the MOC, as evidenced by its ability to permute with the MOC (11a); neither could it be a dependent of cher (otherwise known as a tough adjective on its own), as it can be replaced by a noun phrase expressing a cost such as des milliers d’euros (‘thousands of euros’) in (11b), which cannot function as a tough predicate (11c). Tough predicates therefore further support the case for an analysis that keeps the subject available for control in addition to externalising the missing object.

Notice that French lacks several other cases of missing object constructions found in English, namely purpose infinitives, too and enough complements, and need predicates (Grover 1995), which simply do not find any parallel in French.

Finally, we leave aside substantival uses of the MOC that do not express the missing object as in à manger ‘food’ (‘eatable material’, literally ‘to eat’), à boire ‘drink’ (‘drinkable material’, literally ‘to drink’), an unproductive pattern (e.g. à lire cannot form an NP to mean ‘reading material’), which we consider to be lexicalised phrases.

2 Internal properties

2.1 Passive properties

The examples given so far leave the subject of the infinitive of the MOC unexpressed (although in the object predication and tough uses, it may be controlled). Yet this subject can be realised internally as an oblique marked by par (‘by’), a realisation typically found with participial passives:

- (12)

- un

- a

- livre

- book

- à

- to

- lire

- read

- par

- by

- toute

- all

- la

- the

- classe

- class

- ‘a book to be read by the whole class’

Together with the promotion of the same verb’s DO to be used as a general external argument, this property has led to analyses of the MOC as a modal (see next section) infinitival passive (Giurgea & Soare 2007).

2.2 Modality

As in English, the MOC carries some modality: un livre à lire denotes a book that one either must or can read. However, the status of modality in the tough construction is less clear. Although an analysis of tough adjectives as covert (bouletic) modals has been proposed for English (Fleisher 2008), the specifically deontic/epistemic modality that exists in all other uses is clearly different from the circumstantial modality tough predicates may carry. Conversely, deontic/epistemic modality is actually found in at least two other French infinitival constructions, the infinitival relative (13) and interrogative (14) clauses.

- (13)

- un

- a

- endroit

- place

- où

- where

- aller

- go

- ‘a place to go’ = ‘a place where one can/must go’

- (14)

- a.

- Où

- where

- aller ?

- go

- ‘Where to go?’ = ‘Where can/must one go?’

- b.

- Je

- I

- ne

- neg

- sais

- know

- pas

- not

- où

- where

- aller.

- go

- ‘I do not know where to go.’ = ‘I do not know where one can/must go.’

2.3 Locality

French MOCs have been claimed since at least Kayne (1974; 1975) to be VP bounded: the dependency between the antecedent and the missing object is said not to hold across an embedding predicate like essayer below.

- (15)

- Abeillé et al. (1998: 4), our gloss

- a.

- *Le

- the

- travail

- work

- était

- was

- facile

- easy

- à

- to

- essayer

- try

- de

- to

- finir.

- finish

- ‘The assignment was easy to try to finish.’

- b.

- The assignment was easy to try to finish.

This contrasts with English, where this construction has been treated by Pollard & Sag (1994) as a (weak) unbounded dependency:

- (16)

- Grover (1995: 20)

- Kim would be easy for you to persuade Lee to talk to.

- (17)

- Dalrymple et al. (2000: 16)

- Mary is hard for me to believe Leslie kissed.

French tense auxiliaries, however, have been observed to be transparent to this dependency:

- (18)

- Abeillé et al. (1998: 24), our gloss

- des

- indef.pl

- gens

- people

- utiles

- useful

- à

- to

- avoir

- have

- fréquenté

- socialised with

- ‘people useful to have known’

Abeillé et al. (1998) have related this transparency to complex predicate formation with tense auxiliaries, a phenomenon involving apparent argument structure sharing between two predicates, namely here the lexical participle and the tense auxiliary. Such argument sharing (or more appropriately raising) is suggested mainly by clitic climbing (19), in which pronominal arguments of the former are hosted by the latter.1

- (19)

- Elle

- she

- l’

- 3sg.m

- a

- has

- lu.

- read

- ‘She has read it.’

Under this perspective, the transparency of clitic climbing verbs does not contradict the traditional generalisation that missing objects are always strictly local: such apparently non-local missing objects would actually be local raised objects of the upstairs auxiliary. This reasoning makes an important prediction: all and only clitic climbing verbs should be observed to license embedded missing objects. The first half of this statement is easily verified by looking at the rest of the limited class of French clitic climbing verbs, namely causative faire, laisser and the perception verbs voir, entendre, regarder, écouter.2 As illustrated below for faire (20a) and voir (20b), natural examples from corpus can be found.

- (20)

- FrWaC (2010) examples

- a.

- Example from cndp.fr

- les

- the

- différentes

- different

- compétences

- skills

- à

- to

- faire

- make

- acquérir

- acquire

- aux

- to the

- élèves

- students

- de

- of

- cycle

- cycle

- 1

- 1

- ‘the different skills to make the preschool pupils acquire’

- b.

- Example from free.fr

- donner

- give

- leur

- their

- avis

- opinion

- sur

- on

- ce

- this

- problème

- problem

- et

- and

- sur

- on

- tous

- all

- ceux

- those

- qui

- that

- leur

- dat.3pl

- sembleraient

- would seem

- intéressants

- interesting

- à

- to

- voir

- see

- discuter

- discuss

- ‘to give their opinion on this problem and on all those that would seem interesting to see being discussed’

However, the second half of the prediction does not seem to prove empirically accurate. Abeillé et al. (1998) already mention the possibility of transparent modal, movement and aspectual verbs for some speakers:

- (21)

- Abeillé et al. (1998: 4), our glosses

- a.

- %

- un

- a

- livre

- book

- à

- to

- devoir

- must

- lire

- read

- dès

- as soon as

- aujourd’hui

- today

- ‘a book to have to read today’

- b.

- %

- une

- a

- ville

- town

- difficile

- difficult

- à

- to

- aller

- go

- visiter

- visit

- en ce moment

- nowadays

- ‘a town difficult to go to visit now’

To the best of our knowledge, no speakers of modern French allow clitic climbing with such verbs. The two properties – transparency to a missing object dependency and clitic climbing –therefore appear to be actually distinct, though certainly overlapping.

To determine with more precision the extent of the class of non-climbing predicates that may embed a missing object infinitive, we conducted a corpus study on frWaC (Baroni et al. 2009), which is presented in the next section.

3 Corpus study

3.1 Method

The corpus study was carried out on FrWaC (Baroni et al. 2009), a lemmatised and PoS-tagged 1.3 billion word web-harvested corpus of French. We decided on the corpus precisely because of this large size, since we were looking not just for a particular, somewhat infrequent construction, but for particular sub-cases of this construction (those that involve an embedded missing object).

The corpus queries were conducted using Corpus Query Language (CQL – Jakubíček et al. 2010) expressions in Sketch Engine.3 The basic search pattern for MOCs is illustrated in (22): essentially we searched for sequences of à followed by two infinitives. The use of optional search terms allowed us to cater for potentially intervening adverbs, pronominal clitics, and the markers de and à that precede some embedded infinitives (e.g. finir de, commencer à).

- (22)

- Basic CQL expression for the MOC:[word = “à”] [tag = “ADV”]? [tag = “ADV”]? [tag = “PRO.*”]? [tag = “PRO.*”]? [tag = “VER:infi”] [lemma = “de”| lemma = “à”]? [tag = “ADV”]? [tag = “ADV”]? [tag = “PRO.*”]? [tag = “PRO.*”]? [tag = “VER:infi”]

- ADV = Adverb, PRO.* = Personal pronoun, VER:infi = Infinitive verb

As the corpus does not contain structural information, it was not possible for the expressions to be sensitive to a missing object, and so the results of such queries contained many infinitival phrases marked by à that were not MOCs, such as can occur as complements of various predicates in French. The method we used was therefore to further restrict the search pattern by providing left context appropriate for the MOC, which is only licensed in four different contexts (recall Section 1). Leaving out object predication,4 we defined three different CQL search terms to provide left context corresponding to subject predicative, attributive, and tough use. Subject predicative context was defined by a disjunction of lemmata termed as predicative in the machine-readable Lefff valency lexicon (Sagot 2010) immediately before the MOC. Attributive context was simply defined by the presence of a noun immediately before the MOC. As for tough constructions, the query was built by prefixing a disjunction of tough adjectives (other categories of tough predicates were deemed too infrequent). Starting from the list provided by the Grande Grammaire du français (Abeillé & Godard 2021: Table VI-8), the list of adjectives was extended by making an inventory of tough adjectives by searching the corpus for sequences of an adjective followed by à and an infinitive. The full list of tough adjectives identified in that way is given below.

- (23)

- absurde, admirable, adorable, affreux, agréable, aisé, alléchant, amer, amusant, appétissant, âpre, ardu, assommant, atroce, balaise, banal, beau, bizarre, bon, bouleversant, bénéfique, bête, capital, cauchemardesque, chaud, cher, chiant, chouette, chronophage, comique, commode, complexe, compliqué, con, confortable, contraignant, cool, coriace, coton, coûteux, crucial, cruel, cuisant, curieux, dangereux, difficile, différent, dingue, distrayant, douloureux, doux, drôle, dur, dégoûtant, dégueulasse, délicat, délicieux, délirant, dément, déplaisant, dérangeant, déroutant, désagréable, désirable, désolant, économique, effrayant, effroyable, élémentaire, embarrassant, empoisonnant, encombrant, énervant, ennuyant, ennuyeux, énorme, épouvantable, éprouvant, épuisant, éreintant, essentiel, étonnant, étrange, évident, excellent, extraordinaire, fabuleux, facile, fascinant, fastidieux, fastoche, fatigant, flou, fondamental, formidable, fou, fragile, fun, gonflant, grand, grandiose, gratuit, grave, grisant, gros, génial, gênant, hallucinant, hasardeux, haut, hideux, hilarant, honteux, horrible, hyperfacile, idiot, idéal, illicite, immédiat, important, impossible, impressionnant, impropre, impératif, inaudible, inconfortable, incroyable, indispensable, infect, infernal, infâme, inintéressant, injuste, insoutenable, insupportable, intelligent, interminable, intolérable, intuitif, intéressant, inutile, irritant, joli, jouissif, joyeux, judicieux, laborieux, laid, lassant, lent, long, louable, lourd, lourdingue, léger, magique, magnifique, majestueux, malaisé, malcommode, malheureux, malin, marrant, mauvais, meilleur, merveilleux, mignon, moche, moindre, monstrueux, mortel, méchant, naze, net, nul, nécessaire, obligatoire, obscène, palpitant, paradoxal, passionnant, pathétique, perplexe, personnel, pertinent, petit, physique, pitoyable, plaisant, polluant, possible, poussif, pratique, primordial, prioritaire, précieux, préférable, prématuré, pénard, pénible, périlleux, raide, raisonnable, rapide, rare, ravissant, redoutable, reposant, ridicules, rigolo, risqué, rude, réaliste, réjouissant, sain, salubre, savoureux, sidérant, simple, simplissime, somptueux, souple, spectaculaire, splendide, stressant, subjugant, sublime, suffisant, super, superbe, surprenant, sympa, sympathique, sympatoche, tendre, terrible, terrifiant, toxique, triste, trivial, troublant, ultra-facile, ultra-simple, ultrarapide, urgent, utile, vexant, vital, vulgaire

Further restrictions were added to the queries to help identify the target construction more efficiently by filtering out the most common sources of noise (false positives). Firstly, personal pronouns preceding the infinitive that always express direct objects (le, la, les) were filtered out, as they indicate a direct object that is not missing but pronominalised. Secondly, the word directly after the second infinitive was constrained to not be a determiner, as determiners in this position very frequently introduced an expressed (i.e. non-missing) direct object. Thirdly, we identified, via successive refinement, some lexical items that were prone to yield an incommensurate number of false positives, and consequently excluded them from the search pattern. For example, the nouns manière and façon (‘manner, way’) were ruled out in the attributive search pattern, as they very frequently head a saturated (i.e. with no MO) à-infinitival complement (e.g. de manière à trouver du travail, ‘in order to find work’); similarly, dire was excluded from the predicative search pattern as it was overly frequent because of its use in c’est à dire ‘that is to say’.

These measures were not sufficient to suppress all false positives from the results, but they were effective enough to permit manual inspection of the results to identify legitimate instances of MOCs. Although these restrictions may have precluded some valid examples from being turned up by the search patterns (false negatives), such as e.g. an unlikely use of manière as an antecedent noun modified attributively by a MOC, we feel this effect was minimal and did not greatly affect the number of results gathered. Further notable limitations of this study can be traced to the limitations of the chosen corpus: as a web-harvested corpus, frWaC often contains spelling mistakes, which in turn limited the effectiveness of searching by tag. Although false positives returned because of spelling or tagging issues could easily be discarded when browsing the results, it is possible that such issues prevented valid examples of embedded missing objects from being properly retrieved.

3.2 Results

The first infinitive verb of each successfully identified missing object construction that was returned by the query was added to an inventory of transparent embedding predicates. These verbs are listed below, followed by one of the sentences they occurred in. The numbers in brackets denote the amount of unique occurrences in the corpus.

- (24)

- Movement verbs

- a.

- aller (189) – example from allocine.fr

- Un

- a

- bon

- good

- film

- film

- à

- to

- aller

- go

- voir

- see

- pour

- for

- le

- the

- plaisir

- pleasure

- des

- of the

- yeux.

- eyes

- ‘A good film to go and watch for your visual pleasure.’

- b.

- venir (61) – example from angers.fr

- des

- indef.pl

- panneaux

- signposts

- de

- of

- petites

- little

- annonces

- advertisements

- à

- to

- venir

- come

- consulter

- refer to

- sans

- without

- modération

- moderation

- ‘posting boards with advertisements to come and browse without moderation’

- (25)

- Modal verbs

- a.

- devoir (4) – example from probb.fr

- Histoire

- in order

- de

- to

- ne pas

- neg

- avoir

- have

- trop

- too

- d’

- of

- autocollants

- stickers

- à

- to

- devoir

- have to

- coller

- stick

- sur

- on

- la

- the

- carrosserie

- car’s body

- ‘So as to avoid having too many stickers to place on your car’

- b.

- pouvoir (4) – example from yozone.fr

- les

- the

- deux

- two

- Italiens

- Italians

- ont

- have

- tant

- so many

- de

- of

- portes

- doors

- à

- to

- pouvoir

- be able to

- entrouvrir

- half-open

- qu’

- that

- on

- we

- peut

- can

- s’attendre

- expect

- à

- to

- de

- indef.pl

- magnifiques

- magnificent

- surprises

- surprises

- ‘the two Italians have so many doors to be able to open that we can expect some beautiful surprises’

- c.

- manquer de (3) – example from ird.fr

- Les

- the

- laboratoires,

- laboratories

- équipes

- teams

- ou

- or

- départements

- departments

- et

- and

- les

- the

- chercheurs

- researchers

- à

- to

- ne pas

- neg

- manquer

- miss

- de

- to

- visiter.

- visit

- ‘The labs, teams or departments and the researchers to be sure to visit.’

- (26)

- Aspectual verbs

- a.

- finir de (37) – example from greluche.fr

- J’

- I

- ai

- have

- aussi

- also

- trois

- three

- tonnes

- tons

- de

- of

- billets

- blog posts

- à

- to

- finir

- finish

- d’

- to

- écrire

- write

- ‘I also have a million blog posts to finish writing’

- b.

- commencer à (1) – example from club.fr

- les

- the

- cartes

- maps

- et

- and

- la

- the

- frise

- timeline

- à

- to

- commencer

- start

- à

- to

- apprendre

- learn

- page

- page

- 31

- 31

- ‘the maps and the timeline to begin to memorise on page 31’

- c.

- continuer à/de (3) – example from hardware.fr

- J’

- I

- ai

- have

- récupéré

- retrieved

- un

- a

- projet

- project

- de

- of

- la

- the

- fac

- uni

- à

- to

- continuer

- continue

- de

- to

- developper

- develop

- en

- in

- html

- html

- php

- php

- javascript.

- javascript

- ‘I have retrieved a project from uni to continue to work on in html php and javascript.’

- (27)

- Cognition verbs

- a.

- savoir (34) – example from ac-lille.fr

- On

- we

- créera

- will create

- aussi

- also

- pour

- for

- chaque

- each

- élève

- student

- un

- a

- carnet

- booklet

- orthographique

- orthographical

- où

- where

- seront

- will be

- regroupés

- collected

- par

- by

- ordre

- order

- alphabétique

- alphabetical

- les

- the

- mots

- words

- à

- to

- savoir

- know

- écrire

- write

- et

- and

- les

- the

- règles

- rules

- intuitives

- intuitive

- ‘We will also create for each student a spelling notebook in which the words they need to know how to write will be collected in alphabetical order’

- b.

- apprendre à (2) – example from forumpro.fr

- C’

- It

- est

- is

- le

- the

- plus

- most

- aisé

- easy

- à

- to

- apprendre

- learn

- à

- to

- utiliser

- use

- et

- and

- pour

- for

- la

- the

- mise en page

- formatting

- c’

- it

- est

- is

- nettement

- clearly

- plus

- more

- pratique

- practical

- ‘It’s the easiest one to learn to use and it’s a lot more practical for formatting’

- c.

- oublier de (6) – example from voyage.fr

- Voyage

- Voyage

- vous

- dat.2pl

- propose

- proposes

- une

- a

- petite

- little

- liste

- list

- de

- of

- choses

- things

- à

- to

- ne pas

- neg

- oublier

- forget

- de

- to

- faire

- do

- ‘Voyage provides you with a short list of things to not forget to do’

- d.

- penser à (1) – example from noosblog.fr

- Je

- I

- réalisais

- realised

- accessoirement

- coincidentally

- que

- that

- je

- I

- n’

- neg

- avais

- had

- toujours

- still

- pas d’

- no

- information

- information

- sur

- on

- ce qu’

- what

- on

- we

- y

- there

- mangeait,

- ate

- ni

- nor

- à

- at

- quel

- what

- prix,

- price

- petits

- little

- details

- details

- à

- to

- penser

- think

- à

- to

- demander

- ask

- si

- if

- toutefois

- however

- j’

- I

- étais

- was

- rappelée

- called back

- ‘I coincidentally realised that I still had no information on what could be had for food there, or at what price, little details I should not forget to ask about, if they even called me back’

- (28)

- Volition verbs:5

- a.

- décider de (1) – example from club.fr

- ma

- my

- question

- question

- c’

- it

- est

- is

- :

- comment

- how

- trouver

- find

- ce qu’

- what

- il y a

- there is

- de

- of

- possible

- possible

- à

- to

- décider

- decide

- de

- to

- faire

- do

- ‘my question is: how to find out what possible things to decide to do there are’

- b.

- vouloir (1) – example from listesratures.fr

- La

- the

- qualité,

- quality

- donc

- so

- l’

- the

- appréciation

- appreciation

- des

- of the

- lecteurs,

- readers

- semble

- seems

- l’

- the

- objectif

- objective

- logique

- logical

- à

- to

- vouloir

- want

- atteindre.

- reach

- ‘Quality, i.e. readers’ esteem, seems like the logical goal to want to reach.’

- c.

- tenter de (6) – example from jussieu.fr

- Parmi

- among

- les

- the

- médicaments

- medications

- à

- to

- tenter

- attempt

- de

- to

- diminuer

- diminish

- puis

- then

- d’

- to

- arrêter

- stop

- de principe,

- a priori

- on

- we

- retient

- memorise

- les

- the

- médicaments

- medications

- à

- with

- effet

- effect

- anticholinergique

- anticholinergic

- ‘Among the drugs to try to diminish and a priori to quit using, drugs with an anticholinergic effect stand out’

- d.

- oser (1) – example from ens-lsh.fr

- J’

- I

- ai

- have

- une

- a

- fureur

- furor

- pour

- to

- assister

- attend

- à

- to

- ces

- these

- audiences,

- audiences

- qui,

- which

- par fois,

- sometimes

- sont

- are

- à

- to

- n’

- neg

- oser

- dare

- qualifier,

- describe

- comme

- like

- cette,

- this

- prescription

- prescription

- rétrograde,

- backward

- ce

- this

- voyage

- trip

- en

- in

- 1744

- 1744

- qu’

- that

- on

- they

- voudrait

- woud want

- faire

- have

- faire

- made

- aux

- to the

- homes

- men

- de

- of

- 1832

- 1832

- ‘I am outraged to attend these audiences, which, sometimes, one must not dare to describe, like this backward prescription, this trip to 1744 that they would have the men of 1832 do’

- e.

- éviter de (1) – example from free.fr

- Le

- the

- padding

- padding

- est

- is

- à

- to

- éviter

- avoid

- de

- to

- modifier

- modify

- ‘Padding is not to be modified’

These results show that the class of verbs that are transparent to the missing object dependency is broad and quite heterogeneous. It contains many verbs without clitic climbing (24-28), and at least two more semantic types than previously thought (we find cognition (27) and volition (28) verbs in addition to the movement, modal and aspectual verbs recognised by Abeillé et al. 1998). Furthermore, the verbs of this class exhibit various syntactic behaviours, including raising verbs like pouvoir contrasting with control verbs like vouloir, as well as different complement patterns regarding the embedded infinitive (e.g. bare VP with vouloir, marked by à with penser, or marked by de with décider). We therefore reject argument composition as the mechanism responsible for embedded missing objects, and will propose instead in Section 6 an alternative analysis of such cases.

4 Previous analyses

4.1 Movement analysis

The first analysis of French MOCs (specifically in their tough use) is due to Kayne (1977) and it is essentially based on syntactic movement. Although he does note the passive-like effect associated with the construction, he still rejects an analysis along these lines on several grounds. Firstly, he claims that MOCs, unlike participial passives, do not license a par/de-phrase. While we concur on the impossibility of a de-phrase, this is likely due to the associated stative semantics of the verb, which seem incompatible with the agentive interpretation of the subjects of MOCs. Par-phrases, on the other hand, seem to us to be entirely grammatical in this context, and corpus examples abound on frWaC: searching for a tough adjective + à + Vinf + par, we found 546 unique examples of agentive par-phrases, some of which are given below.

- (29)

- FrWaC (2010) examples

- a.

- Example from asso.fr

- Ces

- these

- mélanges

- mixes

- se présentent

- present

- sous

- under

- une

- a

- forme

- form

- liquide,

- liquid

- facile

- easy

- à

- to

- assimiler

- assimilate

- par

- by

- l’

- the

- intestin,

- intestine

- et

- and

- bien

- well

- tolérés

- tolerated

- par

- by

- l’

- the

- estomac.

- stomach

- ‘These mixes appear in liquid form, easy to assimilate by the intestine, and well tolerated by the stomach.’

- b.

- Example from allocine.fr

- Michael

- Michael

- Douglas

- Douglas

- a

- has

- du

- had to

- tout de même

- still

- être

- be

- très

- very

- difficile

- difficult

- à

- to

- manier

- hanfle

- par

- by

- David

- David

- Fincher

- Fincher

- ‘Michael Douglas still must have been difficult for David Fincher to direct.’

- c.

- Example from gouv.fr

- Ce

- this

- contrat

- contract

- est

- is

- global

- global

- et

- and

- plus

- more

- simple

- simple

- à

- to

- gérer

- manage

- par

- by

- les

- the

- autorités

- authorities

- publiques

- public

- ‘This contract is global and simpler for public authorities to manage’

Secondly, Kayne provides the following contrast involving se-verbs:

- (30)

- Kayne (1977: 337–338), our glosses and intended translation

- a.

- Ce

- this

- livre

- book

- est

- is

- difficile

- difficult

- à

- to

- se

- refl

- procurer

- procure

- ‘This book is difficult to procure.’

- b.

- *Ce

- this

- livre

- book

- sei

- refl

- sera

- is

- procuré

- acquired

- (par

- by

- Jeani)

- Jean

- (‘This book is acquired by Jean.’)

Transitive verbs with intrinsic or reflexive se like se procurer (‘to acquire’) can enter a MOC, but not become passive participles. We come back to this point in Section 6.4.

Finally, Kayne notes the possibility of long distance MOCs involving causative faire:

- (31)

- Kayne (1977: 337–338), our gloss

- Cette

- this

- decision

- decision

- sera

- will be

- difficile

- difficult

- à

- to

- faire

- make

- accepter

- accept

- au

- to the

- comité

- committee

- ‘This decision will be difficult to get the committee to accept.’

- (32)

- *Cette

- this

- decision

- decision

- a

- has

- été

- been

- fait(e)

- made

- accepter

- accept

- au

- to the

- comité

- committee

- (‘This decision was made to be accepted by the committee.’)

Essentially, the author rightfully notes that MOCs can be non-local dependencies, while participial passives are not generally non-local (32). However, we can adduce two cases that hint at a more complex picture of the locality of passive-like operations in French. Firstly, medio-passive se can operate non-locally:

- (33)

- Grâce

- thanks

- à

- to

- la

- the

- mode

- trend

- du

- of

- cat-sitting,

- cat-sitting,

- les

- the

- chats

- cats

- se

- refl

- font

- make

- plus

- more

- facilement

- easily

- garder.

- keep

- ‘Thanks to the trend of cat-sitting, it is easier to have your cats kept.’

Secondly, non-local participial passives are in fact found in French, although the class of verbs they can occur with is limited:

- (34)

- a.

- Ce

- this

- monument

- monument

- sera

- will be

- fini

- finished

- de

- to

- construire

- build

- en

- in

- 2023.

- 2023

- ‘This monument will be finished building in 2023.’

- b.

- Achevé

- finished

- d’

- to

- imprimer

- le

- the

- 11

- 11

- décembre

- december

- 1987

- 1987

- ‘Printed on December 11 1987’ (standard phrasing in French edition notices)

The idea of a movement analysis suggested by the author furthermore raises the question of the boundedness of the dependency: although such an approach could certainly deal with examples like (31), it remains unexplained how a movement rule would correctly account for the peculiar locality of the construction that we uncovered in the previous section, and would likely overgenerate to an unbounded dependency.

4.2 Reduced relative analyses

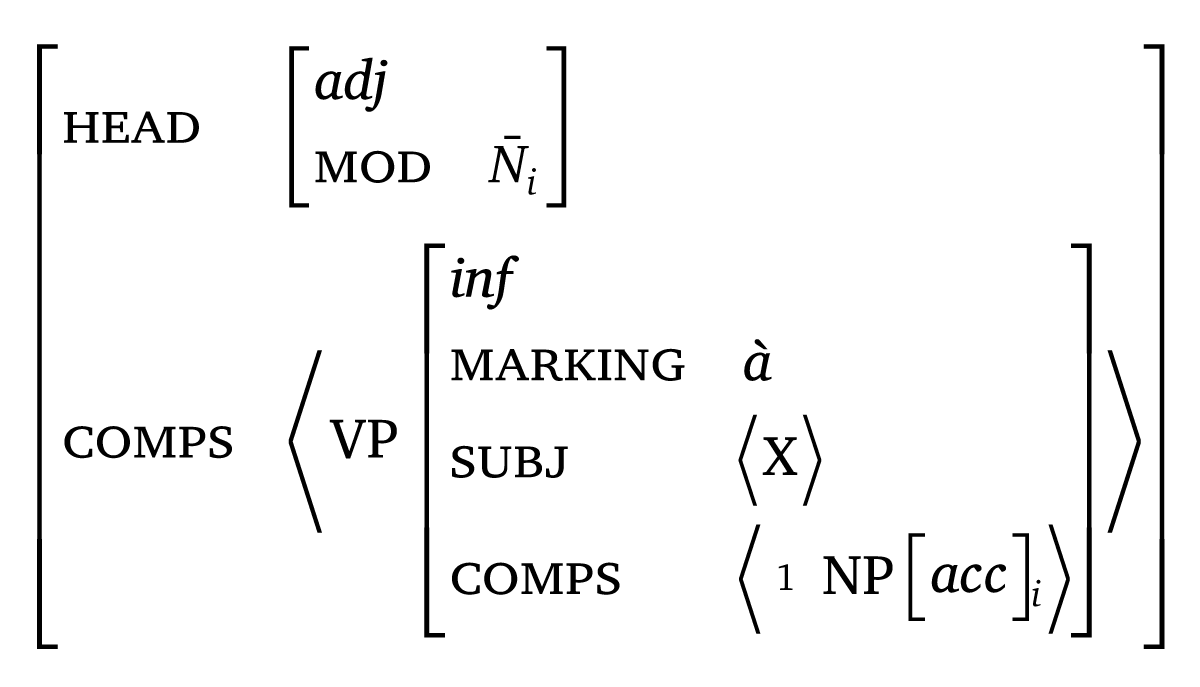

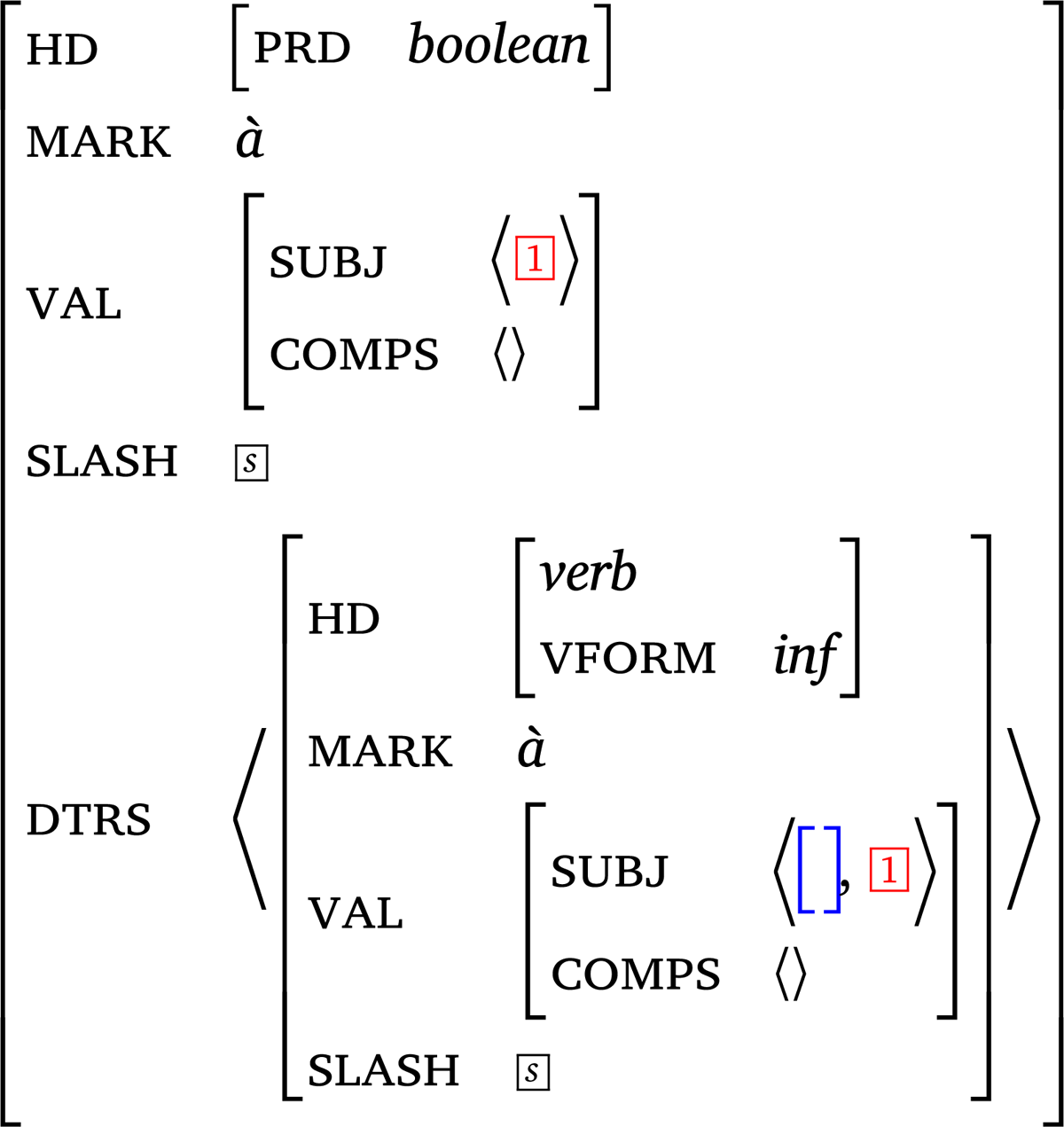

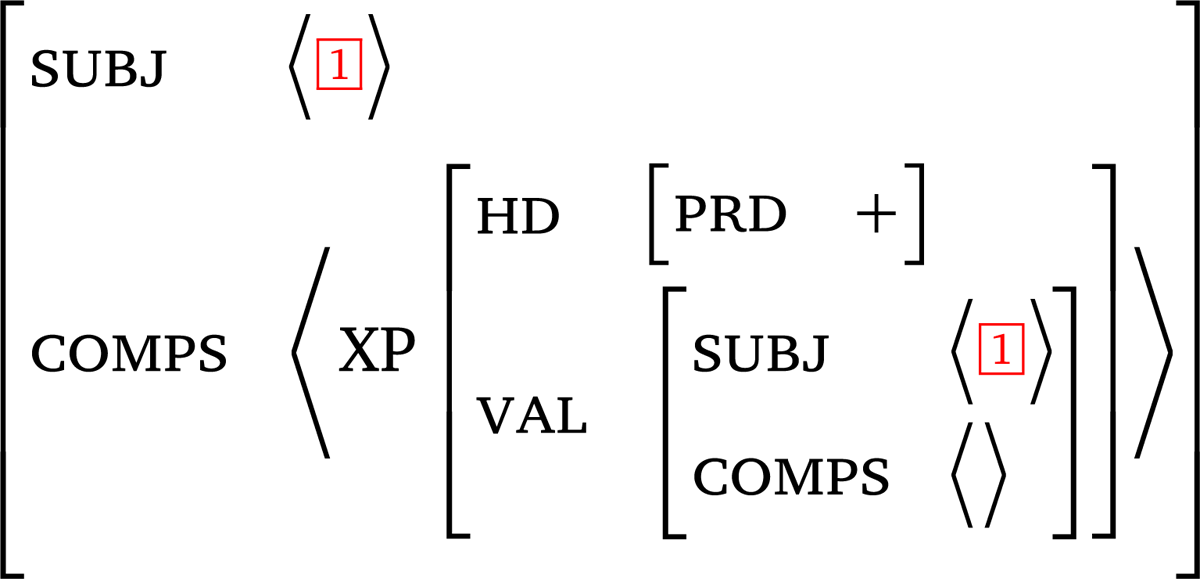

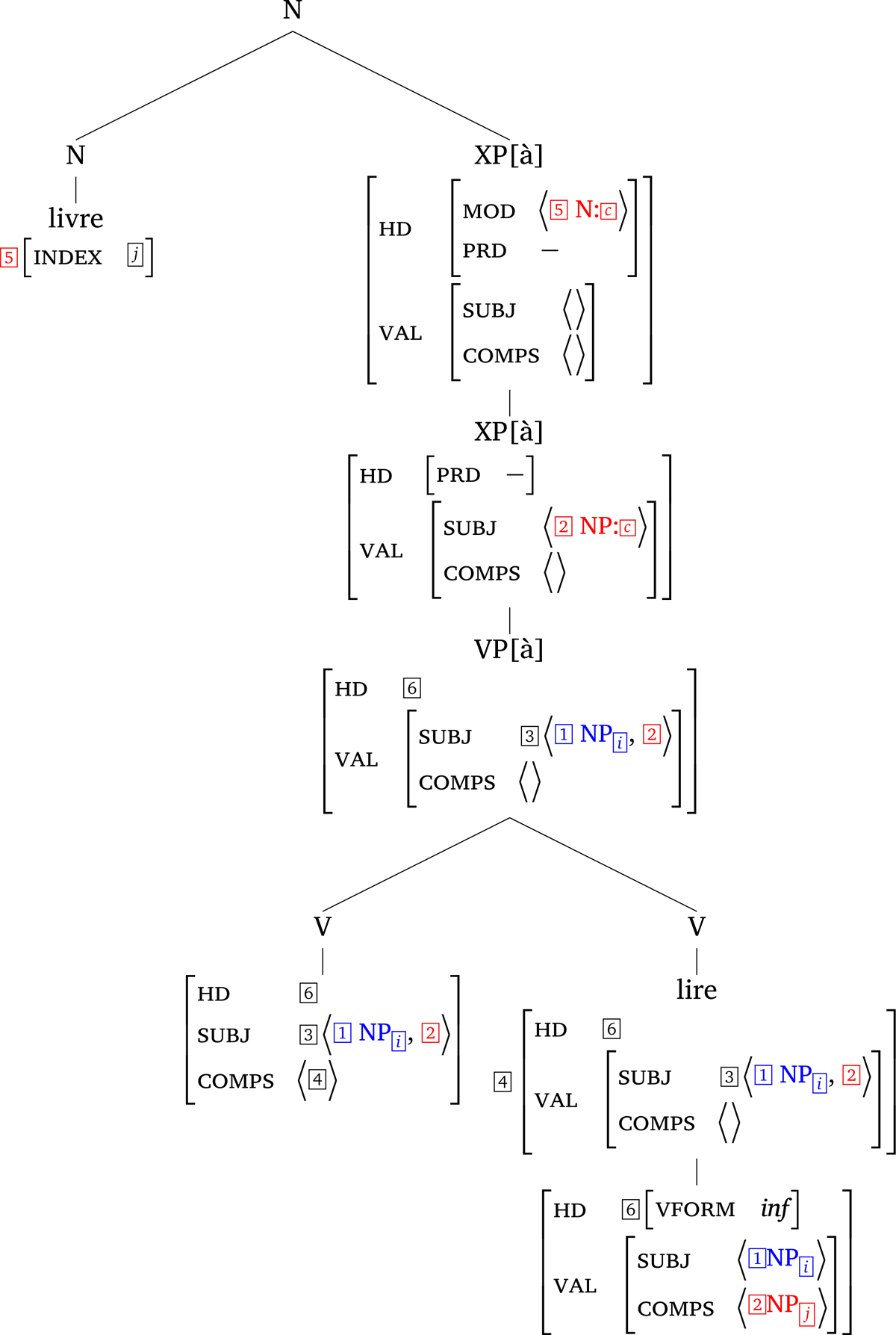

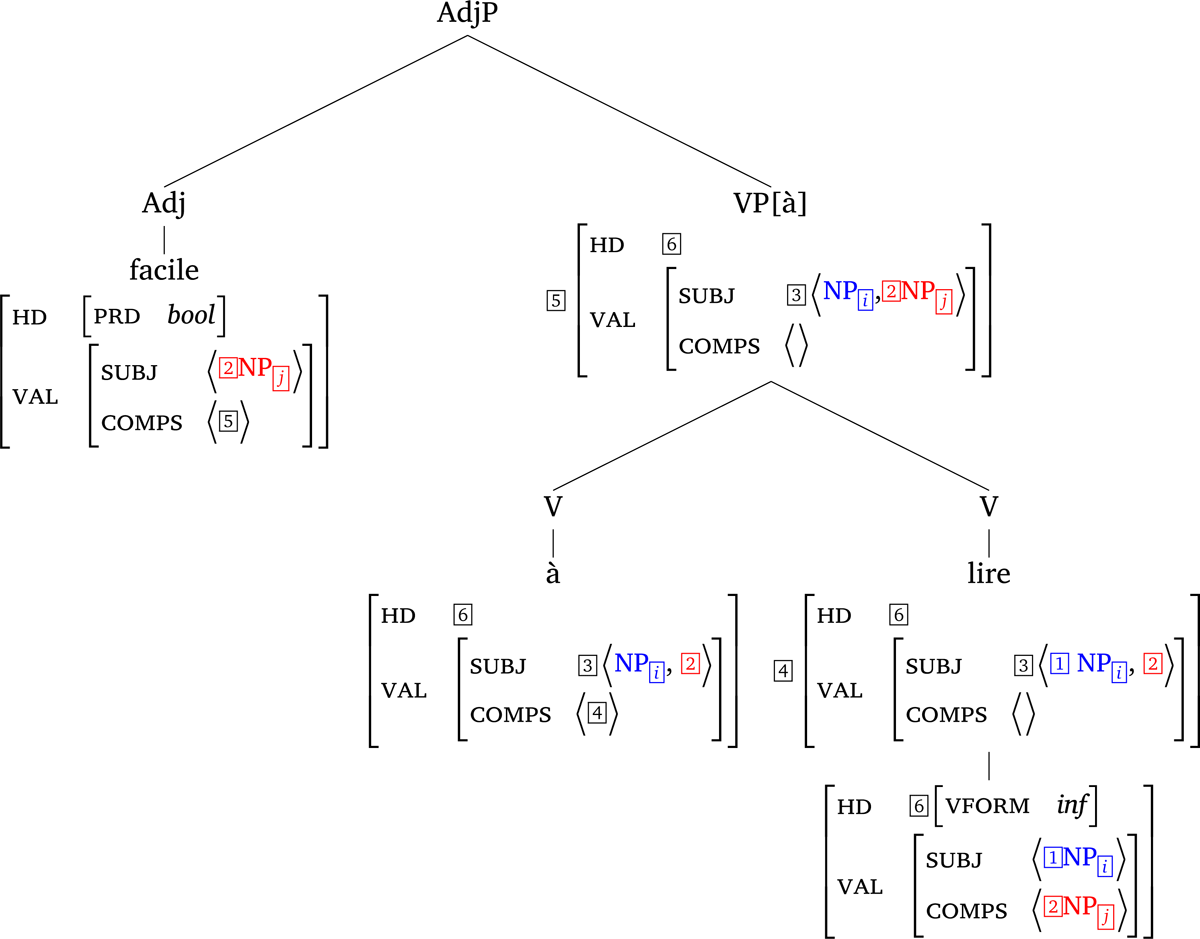

In their analysis of French MOCs, Abeillé et al. (1998) capitalise on the restricted locality of the construction, claiming that only argument composition verbs like the tense auxiliaries avoir/être, as well as faire/laisser and perception verbs are transparent to the MOC. What these verbs have in common is that they permit clitic climbing, which Abeillé et al. regard as local morphological expression of raised arguments. The analysis of French tough constructions crucially builds on this: the lexical entry of tough adjectives have their external argument (selected via subj or mod) co-indexed with an unsaturated direct object valency of their à-infinitival complement, as detailed in Figures 1, 2.

Facile – attributive variant (from Abeillé et al. 1998: 7).

Facile – predicative variant (from Abeillé et al. (1998).

Attributive uses of the MOC receive a similar analysis. Abeillé et al. (1998) treat them as infinitival relative clauses, suggesting that there are three ways in which an antecedent noun can be related to an argument within the relative: either by way of an unbounded dependency (slash) or by direct co-indexation with an unsaturated subj (qui-relatives) or comps valency (MOC).

There are several problems with this line of analysis: first, an infinitival relative analysis is intrinsically limited to attributive uses and tough constructions. Most crucially, this approach does not extend to subject predications, since the verbs used in these contexts, like copula être or sembler, are subject-to-subject raising verbs, not object-to subject raising verbs.

Second, as we have shown in Section 3, the class of verbs transparent to the MOC is by no means limited to clitic climbing or argument composition verbs, but comprises a larger class of VP-taking control and raising verbs, most of which do not exhibit the kind of behaviour that Abeillé & Godard (2002) associate with argument composition.

Third, the passive-like properties of the construction remain entirely unaccounted for. This holds most obviously for the realisation of the logical subject as an oblique par-phrase. But it also treats as a mere coincidence the fact that the external argument in a MOC is always the logical direct object.

- (35)

- une

- a

- petition

- petition

- à

- to

- signer

- sign

- par

- by

- tous

- all

- les

- the

- membres

- members

- ‘a petition to be signed by all members’

4.3 Raising

4.3.1 A-movement in Romance

Giurgea & Soare (2007) discuss tough constructions in Romance, noting the formal similarities to predicative and attributive uses of the missing object construction. They suggest that these constructions are passive-like and should therefore be captured in terms of A-movement (raising).

Giurgea & Soare (2007), however, do not address the issue of locality: in the light of the data presented in Section 3, A-movement will have to cross intervening PRO subjects, essentially leading to principle A violations. Similarly, their proposal does not address the case of external control either. Thus, while we concur with their perspective of the missing object construction as an instance of grammatical function change, we do note that A-movement per se is insufficient to do full justice to internal and external control.

4.3.2 Missing object constructions in English

While English tough constructions are often regarded as unbounded dependencies (cf. Pollard & Sag 1994), it has been noted that extraction from finite clauses may be subject to individual or dialectal variations (Hukari & Levine 1987). Studying a wide range of missing object constructions in British English, including tough constructions and parasitic gaps, Grover (1995) observes that non-locality of the dependency uniformly involves chains of control or raising verbs.

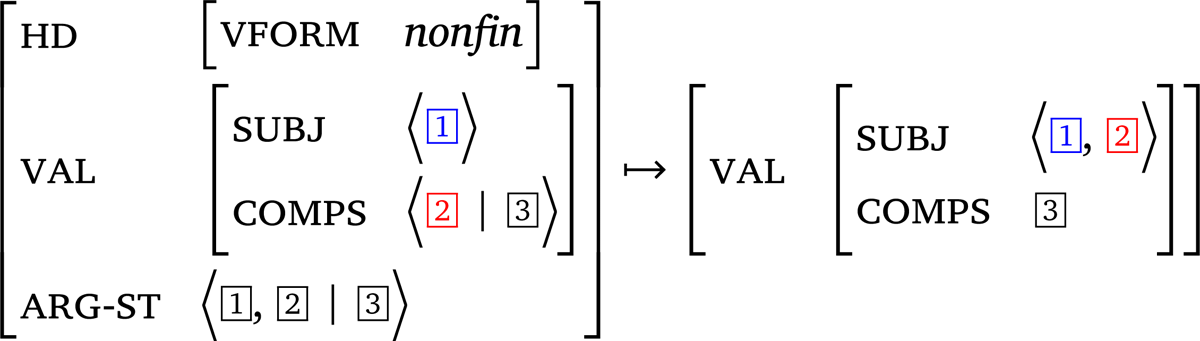

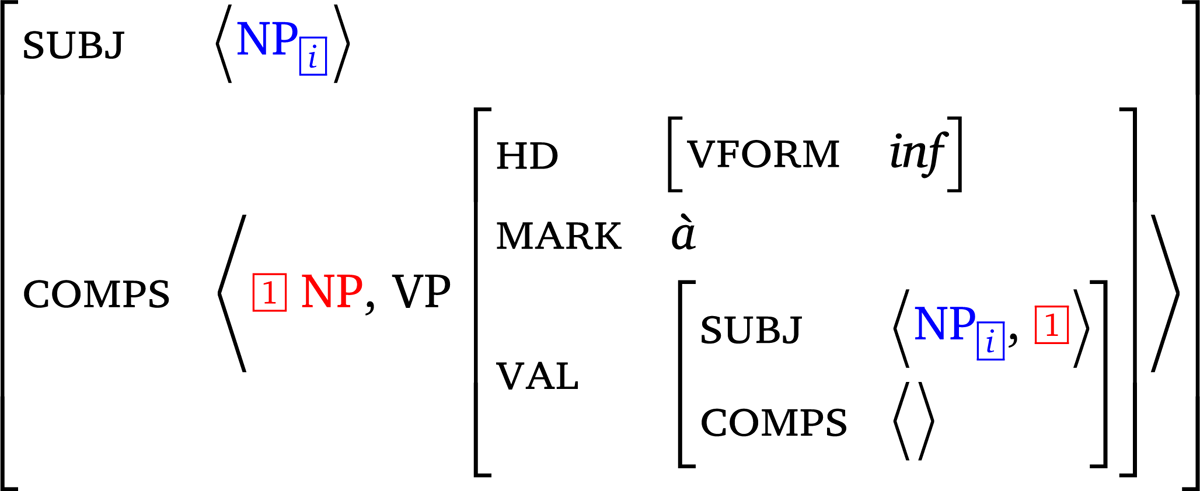

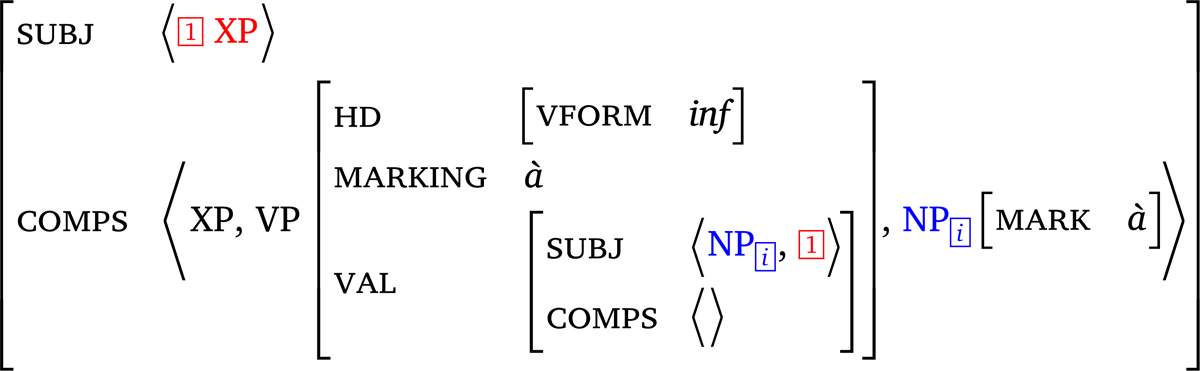

Consequently, Grover (1995) suggests that missing objects are removed from comps, akin to direct objects in true passives, but that they are promoted to secondary subject status: technically, this is implemented by appending the erstwhile direct object valency to the subj list. Control and raising continue to target the first element of a complement’s subj list, but additionally structure-share (=inherit) the list remainder, thereby implementing a notion of secondary subject raising that goes piggy-back on existing control and raising dependencies.

Given the partial overlap between missing object constructions in English and French and the parallelism regarding locality conditions and control relations, our formal analysis of the French data will actually build on Grover’s account.

5 Discussion: Subject status in the missing object construction

As we have seen in the previous sections, the French missing object construction shares some properties with standard lexical passives. First, the argument that remains unexpressed in situ is always the direct object. Second, the missing object behaves as the external argument of the construction, being co-referent with the antecedent noun in attributive use or the grammatical function being predicated on. Third, the downstairs logical subject is either omitted, or else realised by a by-phrase.

While the missing object behaves as the external argument of the construction as a whole, subject status within the construction does not reflect this: most notably, whenever a (subject) control verb intervenes (see Section 3 above), the logical subject of the control verb is co-referent with the logical subject of its infinitival complement, and crucially not with the missing object.

The logical subject of the verb whose object is locally missing is not only available to control within the construction, but can also be controlled from outside. E.g. with object predication, the missing object of the downstairs infinitive corresponds to the direct object of donner or avoir, while at the same time the logical subject of the à-infinitive is controlled by some other function of the object predication verb, i.e. by the subject in the case of avoir, or by the indirect object, in the case of donner. Similarly, control of the logical subject from outside was also found with tough predicates like coûter ‘cost’ and prendre ‘take’, cf. example (10c).

These observations show that we are confronted here with two notions of subject-hood being operative at the same time. One way we can make sense of this is in terms of a two-step passivisation, separating promotion of the direct object from demotion of the logical subject. More precisely, we shall assume that, in a first step, a lexical rule promotes the direct object to secondary subject in the sense of Grover (1995), without demotion of the logical subject, which stays available for control. At the top of the à-infinitive, the grammatical function change is finally concluded.

6 Analysis

We now propose a unified analysis of the MOC as an infinitival passive phrase able to act as a predicate, a modifier, or a selected complement (tough uses). This analysis is formalised in Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG – Pollard & Sag 1994). The chosen approach shall expose two of the construction’s core arguments, viz. not only the missing direct object but also the logical subject which needs to be available for external control. We also take care to account for the particular locality of the dependency independently of argument composition by allowing select lexical heads (i.e. verbs of the class of aller that were found to naturally occur in this position) to intervene transparently within the construction.

We rely specifically on the double subject approach suggested by Grover (1995) to encode the dependency with the missing object. Lexically, the direct object valency is promoted to secondary subject, which accounts not only for the absence of a local direct object complement, but also makes the direct object available to raising. This approach captures the fact that the MOC behaves externally like a passive, but internally maintains canonical control relations by intervening infinitives in non-local cases.

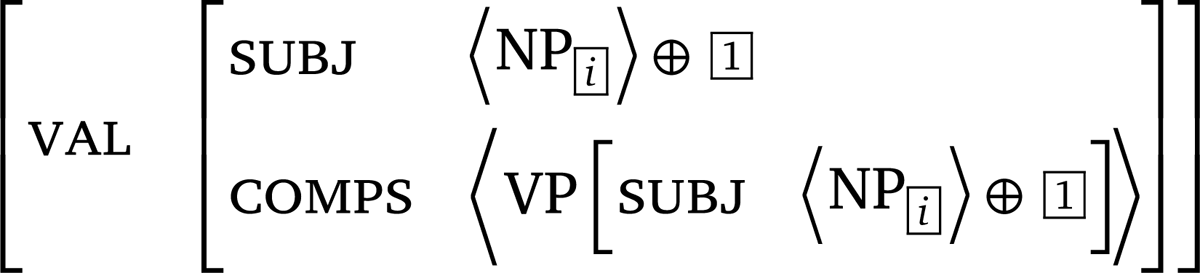

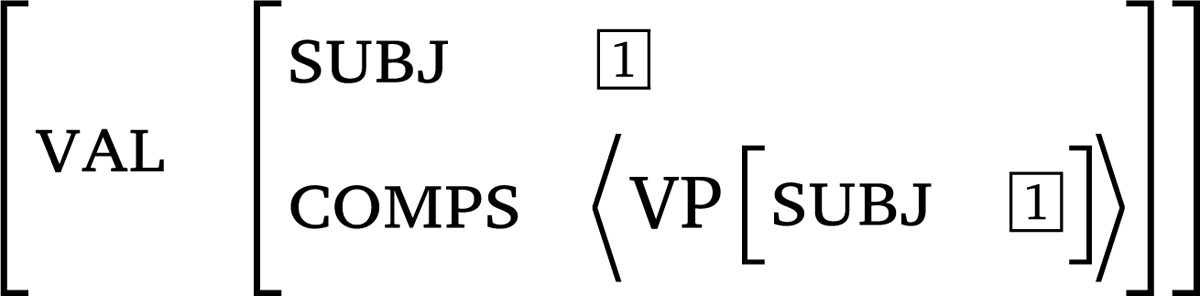

6.1 The bottom of the construction: A lexical rule for passive infinitives

We implement the first step of the passivisation effect, i.e. the local suppression of a direct object valency, by means of a lexical rule operating on valence lists (cf. Grover 1995). This rule, given in Figure 3, applies to a non-finite verb and blocks the realisation of its direct object by taking it off the comps list. As in Grover (1995), the dependency is established on the subj list: the blocked DO becomes a secondary subject of the verb.6 This is enough to license downstairs infinitives or participles with an unexpressed object, while at the same time it constrains the distribution of such passive verbs: as contexts for finite phrases require a single subject under standard HPSG theory, the double subject value effectively limits occurrences of passive infinitives to the special contexts we define below. This can be enforced by a constraint on head-subject phrases requiring the subject list being saturated to have exactly one element, as in Figure 4.

6.2 The top of the construction

As we have seen in the discussion of the empirical patterns, the missing object construction features in four different contexts: attributive use, subject predicatives, object predication (e.g. avoir and donner), and tough constructions. While in the case of tough predicates and object predication verbs the missing object construction is specifically selected by the lexical entry of the governing predicate, this is certainly not the case for the attributive use, and it is not necessarily the case for subject predicatives either, if we take absolute predicatives into account, cf. (36).

- (36)

- Avec

- with

- cinq

- five

- livres

- books

- à

- to

- lire,

- read

- il

- he

- est

- is

- vraiment

- really

- en retard.

- behind

- ‘With five books to read, he is really behind.’

We therefore propose that missing object constructions in French can be licensed in one of two ways: either lexically by a governing predicate, or constructionally.

This distinction is further corroborated by the differences regarding control: while the subject of the à-infinitive can undergo obligatory control from outside, this again appears to be limited to the cases where the missing object construction is specifically selected by a governing lexical head, as is the case for object predication verbs, and some tough predicates, cf. (10c), but crucially not for ordinary attributive and predicative uses. Furthermore, the fact that there is lexical variation among tough predicates with respect to control provides additional support for a lexical perspective.

Furthermore, we observed in Section 2.2 that missing object constructions differ also with respect to the modality they introduce: while attributive and predicative uses clearly involve necessity or possibility, this is not the case for tough predicates. Thus, it appears preferable to associate modality not with the à-infinitive directly, but rather make it a property of the context in which it is used.

Finally, there is no evidence that the marker à found at the top of the infinitival construction behaves any different from ordinary infinitival markers: in particular, modal infinitives do not constitute extraction islands, as shown below.7

- (37)

- Abeillé & Godard (2021: VI – 60d), our gloss and translation

- À

- to

- qui

- who

- est-ce

- is it

- que

- that

- ce

- this

- film

- film

- est

- is

- facile

- easy

- à

- to

- montrer ?

- show

- ‘Who is this film easy to show to?’

This contrasts with prepositions, which, unlike VP markers, are indeed islands (Abeillé et al. 2006). If the marker à is unlikely to be a preposition, the predicative and attributive properties are best conceived of as properties of the construction, rather than of its initial lexical marker.

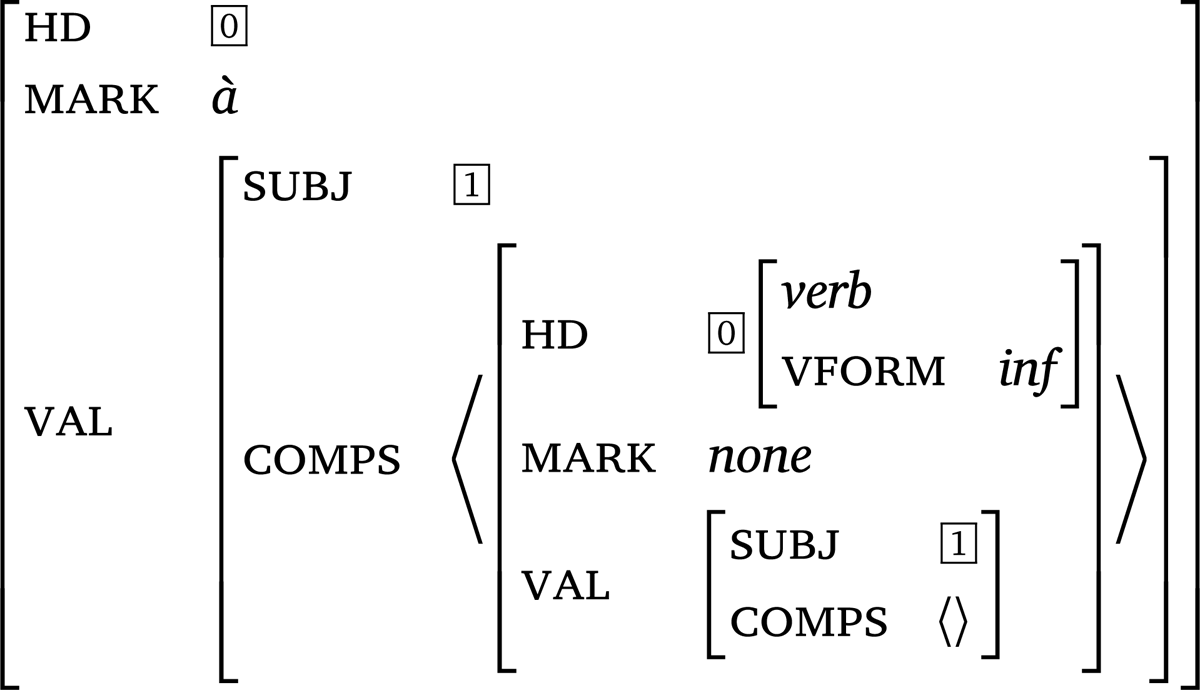

6.2.1 The infinitival marker à

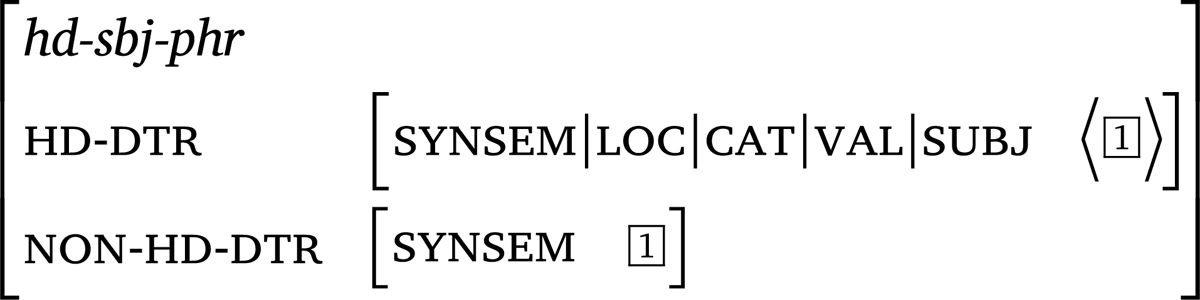

Given the fact that missing object constructions are not extraction islands, thus patterning with ordinary à-marked VPs, we propose that the marker found at the top of the MOC is indeed the ordinary infinitival VP marker.

We shall essentially follow Abeillé et al. (2006), treating the marker as a weak head, as depicted in Figure 5.

In a nutshell, the marker takes an infinitival VP complement, with which it shares the subj and h(ea)d values. It differs from its bare VP complement, however, in terms of its mark value.

6.2.2 Constructional licensing of MOCs: predicative and attributive uses

As we have observed above, attributive and subject predicative uses differ from tough constructions and object predications in two crucial respects: first, there is no specific lexical governor selecting the missing object construction and there is no control of the infinitive’s primary subject from outside. Moreover, French VPs do not normally have attributive or predicative uses.

We therefore suggest that predicative and attributive uses are actually licensed by a specific construction, implemented by the unary rule detailed in Figure 6. The rule projects an XP[prd boolean] from a double subject à-marked VP. Crucially, this rule ignores the primary subject of the VP daughter, and raises that daughter’s secondary subject to its own subj value, thereby concluding the passivisation effect.

Subject predication

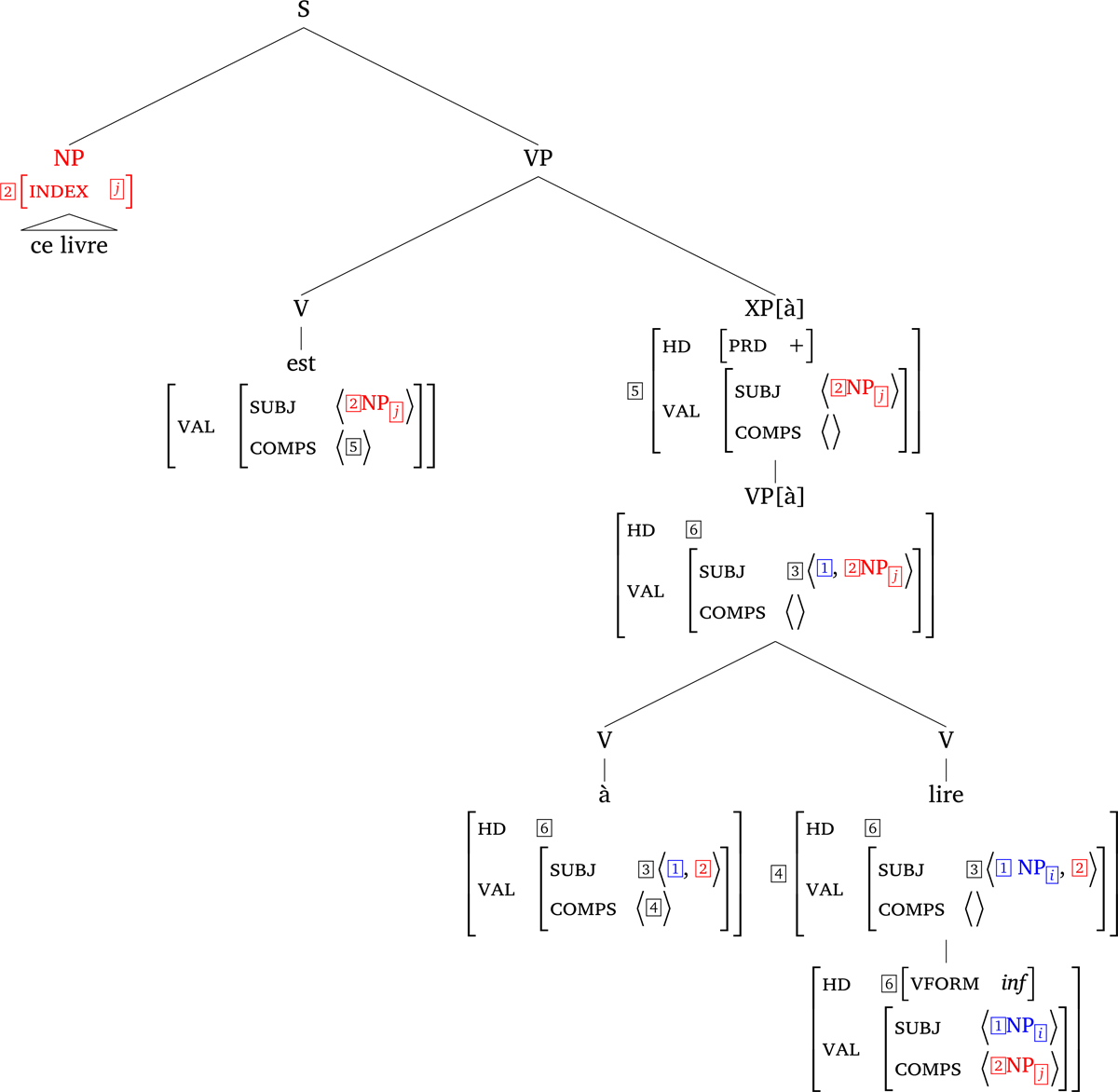

The predicative use of the MOC is straightforwardly derived under a standard HPSG account by subject-to-subject raising. A lexical entry for the copula is given in Figure 7; similar entries can be given to other copular verbs.

The tree in Figure 8 illustrates the analysis of a simple predicative instance of the construction, ce livre est à lire (‘this book is to be read’).

Attributive use

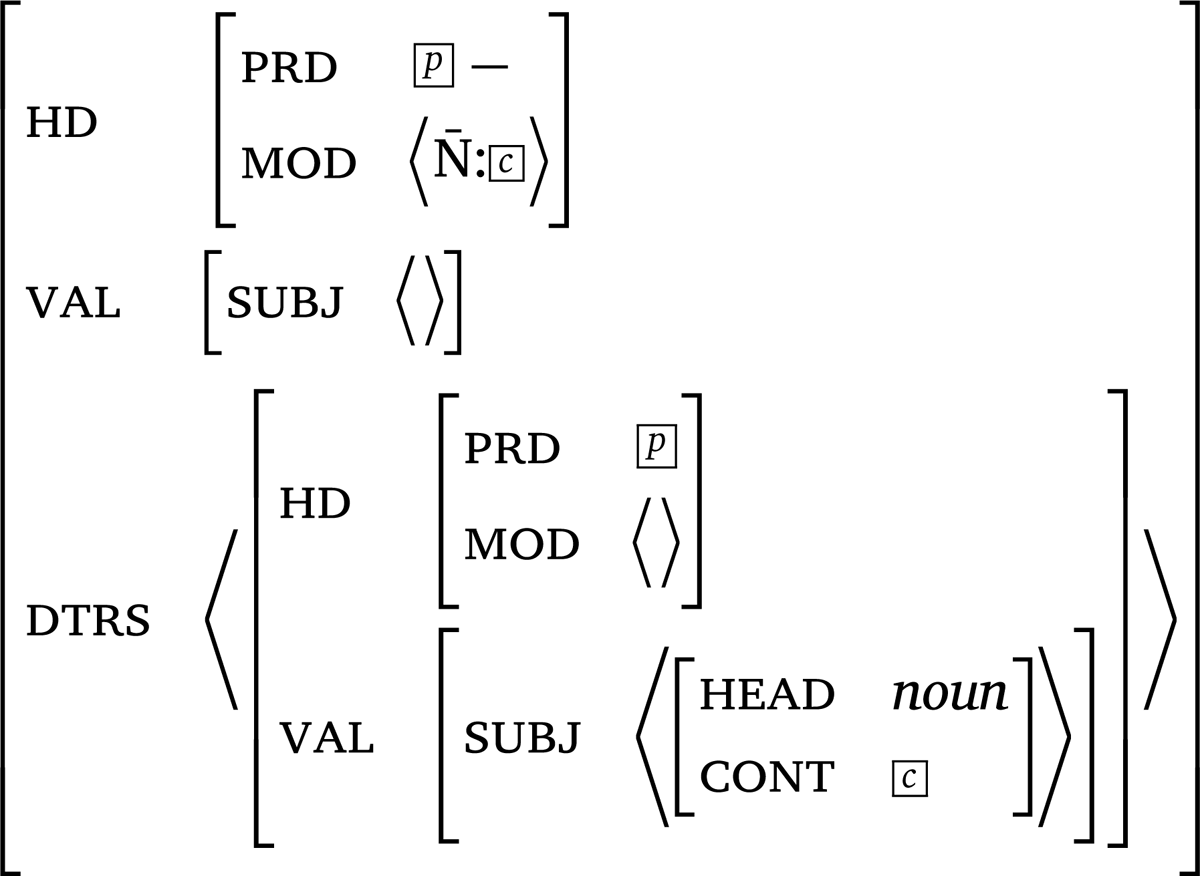

Just like English, French displays a systematic alternation between predicative and attributive uses for e.g. adjectives. We model this alternation by means of a unary rule deriving the latter from the former. This rule is given in Figure 9. The rule simply shifts the valence from subj to mod(ifier). As the predicative/attributive alternation in general may have exceptions both ways (non-attributive predicates and non-predicative attributes), the feature pr(e)d(icative) controls which elements may undergo it, restricting application to signs for which prd is defined and where the value unifies with –, which includes boolean.

A sample derivation for a simple local attributive MOC, livre à lire ‘book to read’, is given in Figure 10.

6.2.3 Lexical licensing of MOCs

Lexical heads selecting for the missing object construction include object predication verbs, such as avoir, donner, or laisser, as well as tough predicates. In contrast to attributive and subject predicative uses, we also find control of the primary subject of the à-infinitive. Thus, we assume that in these constructions, the governing lexical item directly subcategorises for a double subject à-infinitive.

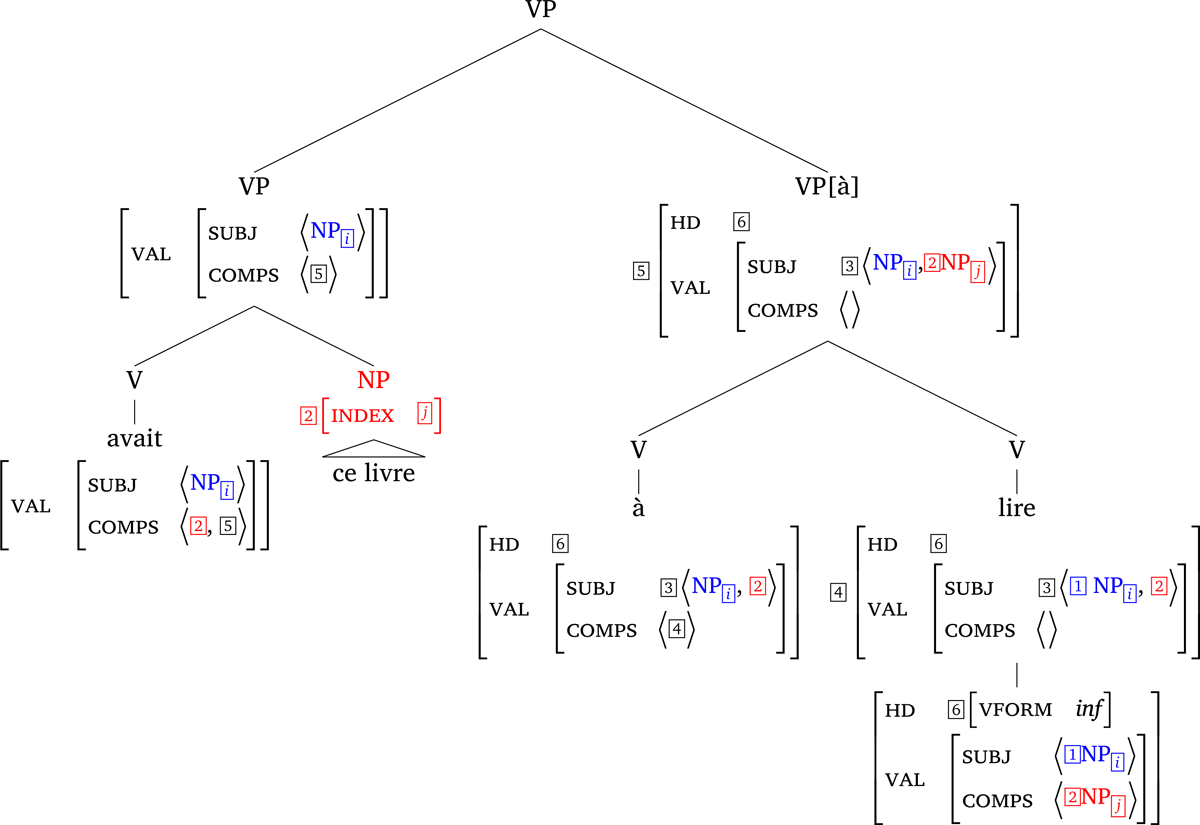

Object predication

We treat object predication as involving both control and raising. A lexical entry for avoir is given in Figure 11. As can be seen in the entry, the subject of avoir exerts control over the primary subject of the MOC, just like control is done within the MOC. The secondary subject of the à-infinitive is raised to object.

Donner works very similarly to avoir in this context, only it is the indirect object rather than the subject that acts as a controller for the primary subject of the à-infinitive (Figure 12).

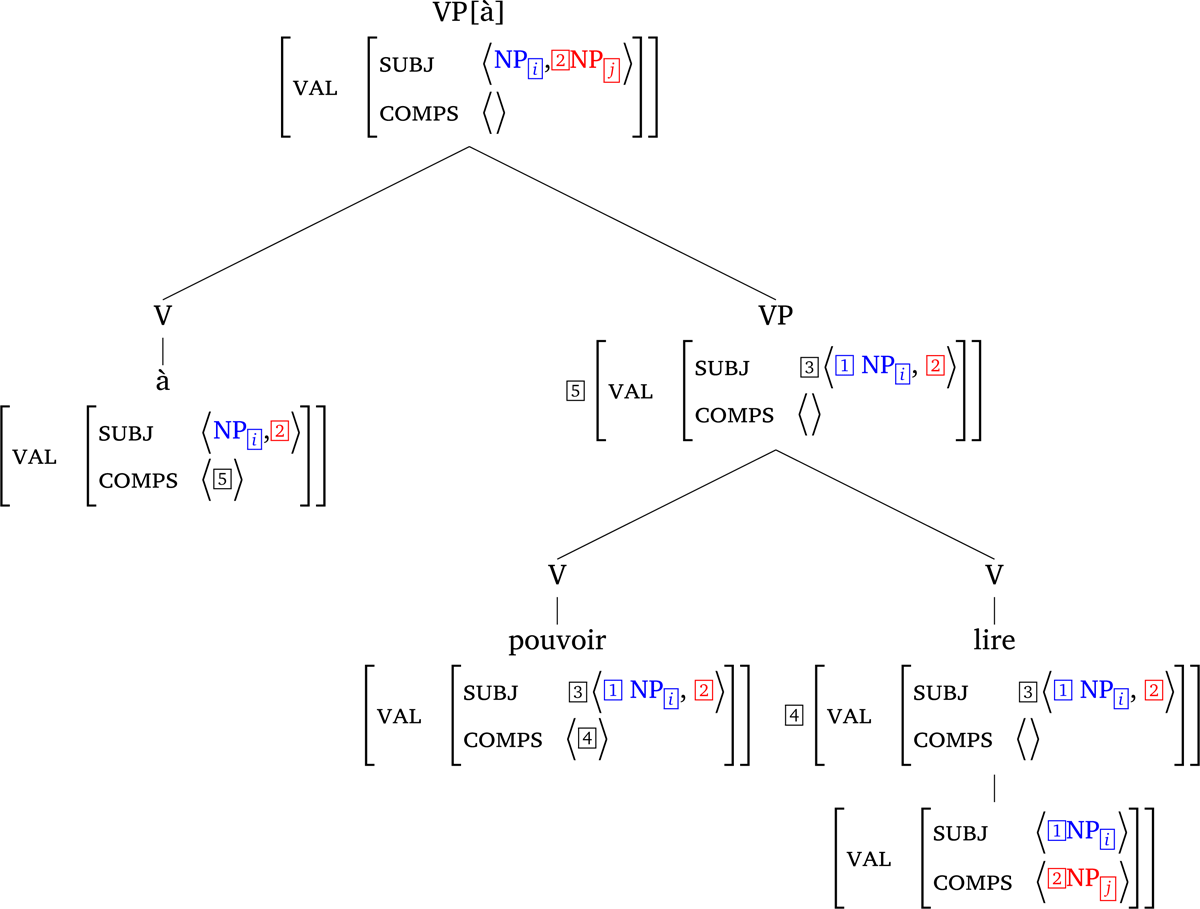

The different raising and control relations are illustrated in Figure 13, which derives avait ce livre à lire ‘had to read this book’.

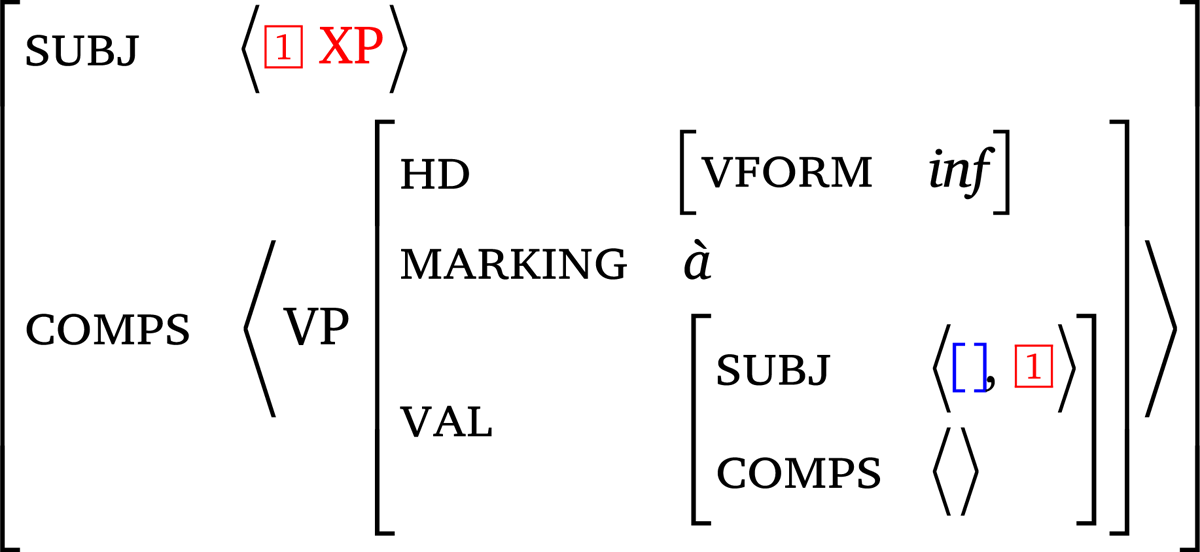

Tough uses

We also analyse tough predicates in terms of raising of a secondary subject. A lexical entry for facile is given in Figure 14, and a sample derivation for facile à lire in Figure 15. Note that attributive uses of tough adjectives can be derived by the unary rule previously given (Figure 9).

As for tough predicates that introduce a controlling argument such as coûter, they can again specify the control relation between the controller and the MOC’s primary subject (Figure 16), analogous to the object predication verbs we discussed above.

6.3 Boundedness

As was found in Section 3, a class of verbs may intervene in the dependency with the missing object, comprising both subject raising and subject control verbs. Our analysis is simply to treat such verbs as optional raisers of secondary subjects. Turning first to subject control verbs like aller, we can give an entry as in Figure 17, which displays the raising of an optional secondary subject. Note that at this point in the structure, the primary subject is still the logical subject, which means control of the subject functions as usual with no further specifications.

As for subject raising verbs like pouvoir, they simply raise their complement’s entire subject list, whether simple or double (Figure 18). This extends quite naturally to the tense auxiliary avoir, with the sole difference of a participial and not infinitival verb form.

As for verbs that are opaque to the dependency, their entries simply require a complement with a singleton subject list, in keeping with standard HPSG.

Finally, some of the transparent verbs discovered embed not a bare infinitive, but one marked with à or de. This requires the minor adjustment of making the two markers subject-list raisers in the same way as pouvoir. The entry for à given in Figure 5 above already takes this into account.

The trees in Figures 19, 20 summarise the analysis of non-local missing objects with intervening control and raising verbs, respectively.

6.4 Reflexive transitives

We can now turn back to the issue concerning reflexive se procurer, which Kayne (1977) cites as evidence against a passive analysis. The relevant contrast is repeated below from (30).

- (38)

- Kayne (1977: 337–338), our glosses and intended translation

- a.

- Ce

- this

- livre

- book

- est

- is

- difficile

- difficult

- à

- to

- se

- refl

- procurer

- procure

- ‘This book is difficult to procure.’

- b.

- *Ce

- this

- livre

- book

- sei

- refl

- sera

- is

- procuré

- acquired

- (par

- by

- Jeani)

- Jean

- (‘This book is acquired by Jean.’)

In our view, the different behaviours of the two passives can ultimately be attributed to the difference in verb form required by the two contexts. While the infinitive form used in the MOC can easily host pronominal clitics of any kind, French syncretic passive-past-perfective participles are morphologically defective, and can never combine with reflexive pronouns such as se. Of course, given the possibility of clitic climbing to the copula in the passive case, this fact alone does not predict the impossibility of (38b). However, facts from another voice phenomenon involving clitic climbing, namely the causative faire-construction, illustrate a peculiarity of the interaction of voice and reflexivity in French:

- (39)

- Ili

- he

- si/*j’

- refl

- est

- is

- fait

- made

- coiffer

- do one’s hair

- par

- by

- Camillej.

- Camille

- ‘He got his hair done by Camille.’

- (40)

- Ili

- he

- a

- has

- fait

- made

- sej/*i

- refl

- coiffer

- do one’s hair

- les

- the

- enfantsj

- children

- ‘He got the children to do each other’s/their hair.’

Essentially, when se originates from the argument structure of a verb in a causative construction, its placement (climbing or local) dictates how it is interpreted: upstairs se is bound by the subject of the causative event, while downstairs se is bound by the lexical verb’s subject. In other words, reflexive se is always locally interpreted, i.e. bound by the local subject of the verb it attaches to. We take the causative situation to be parallel to the participial passive case, and therefore expect that the only way for participial passives to express the binding of se by the logical subject as in (38b) is by downstairs realisation of se. This realisation is however ruled out by morphological defectiveness, whereas upstairs realisation would come with a different binding relying on the passive subject (e.g. the original DO), which explains the ungrammaticality of (38b). The MOC’s passive, which, on the other hand, is an infinitive, can freely realise se locally downstairs, where it is accordingly bound by the lexical verb’s original subject, accounting for (38a).

6.5 Missing sentential complements

Before we conclude, let us briefly address a particular case of the MOC in which the missing object is not an object NP, but a complement clause introduced by que:8

- (41)

- Ruwet (1976: 79–83), our gloss and translation

- Que

- that

- Nixon

- Nixon

- ne soit

- neg.be

- pas

- not

- impliqué

- involved

- […]

- est

- is

- difficile

- difficult

- à

- to

- croire.

- believe

- ‘That Nixon is not involved […] is difficult to believe.’

- (42)

- Que

- that

- Nixon

- Nixon

- ne soit

- neg.be

- pas

- not

- impliqué

- involved

- est

- is

- à

- to

- ne pas

- not

- croire

- believe

- une

- a

- seconde.

- second

- ‘That Nixon is not involved is not to be believed for a second.’

This situation is in fact to be expected under a passive analysis, as que-complements are passivisable in French:

- (43)

- Qu’

- that

- il

- he

- ne soit

- neg.be

- pas

- not

- impliqué

- involved

- est

- is

- encore

- still

- cru

- believed

- par

- by

- beaucoup.

- many

- ‘That he is not involved is believed by many.’

The distribution of such missing sentential complements seems restricted compared to the missing direct objects: attributive uses are excluded, a fact readily derived by the description of the rule in Figure 9, which applies only to nominal heads; object predication uses are also excluded, which we attribute to selectional constraints for NP by the relevant verbs (e.g. avoir, donner; cf. Figures 11, 12); subject predication is possible (42), and allowed by our underspecified description of the subject of copular verbs (Figure 7); as for tough predicates, they also take underspecified XP subjects (Figures 14, 15, 16), correctly allowing sentential complements.

7 Conclusion

In this paper we have presented an in-depth investigation of the French missing object construction (MOC), studying its properties in tough constructions, as well as attributive and subject and object predicative uses. While we concur with previous research regarding the bounded status of the dependency, we have shown on the basis of a corpus study that the class of verbs that can intervene in this construction extends beyond tense auxiliaries and includes a wide range of subject control and subject raising verbs. Furthermore, while the missing object serves as the external argument of the construction, the logical subject remains available for realisation by a by-phrase, as well as for control, both by an intervening verb and from outside. Building on Grover (1995), we have proposed a formal HPSG analysis that treats the missing object as a secondary subject: promotion to secondary subject status not only accounts for the passive-like behaviour of the infinitival construction, but it also captures the potential for obligatory control both within the construction and from outside. Finally, the way raising of the secondary subject depends on existing subject control or raising for the primary subject readily models the locality conditions of the construction.

Abbreviations

dat = dative, f = feminine, indef = indefinite, inf = infinitive, m = masculine, neg = negative, part = partitive, pl = plural, refl = reflexive, sg = singular

Notes

- See, however, Abeillé & Godard (2002) and Aguila-Multner & Crysmann (2020) for a more comprehensive discussion. [^]

- There is another case of clitic climbing in French found with être and other copular verbs, but their complementation pattern restricts them to predicative XPs, which never take DO complements in French, precluding their use in MOCs. [^]

- Kilgarriff et al. (2004; 2014). https://www.sketchengine.eu/. [^]

- Several cases of object predication were in fact returned while searching for attributive uses, all of them complements of avoir. As object predication is much more infrequent than the other contexts, and since cases in which it differs in surface form as a left context from attributive uses are a fortiori even rarer, we do not expect that a significant number of examples were missed by not creating a search expression specific to object predication contexts. [^]

- Two examples involving essayer (‘try’) escaped the attributive queries for technical reasons, but were found while looking specifically for this verb:

- (i)

- Example from free.fr

- Tu

- you

- dis

- say

- :

- “la

- the

- religion

- religion

- vise

- aims

- un

- a

- idéal

- ideal

- à

- to

- essayer

- try

- d’

- to

- atteindre”.

- reach

- ‘You say: “religion aims for an ideal to try to reach”.’

[^]- (ii)

- Example from optimum-blog.net

- l’

- the

- économie

- economy

- est

- is

- un

- a

- truc

- thing

- à

- to

- étudier

- study

- (ou

- or

- à

- to

- essayer

- try

- de

- to

- comprendre)

- understand

- ‘the economy is something to study (or to try to understand)’

- The possibility of having more than one element on the subj valence list has also been explored for the treatment of the Double Nominative Construction in Korean (Lee 2003; Ko 2010; Ryu 2013). Similarly, Müller & Ørsnes (2013) propose an analysis of object shift in Danish that has multiple elements on the spr list, alongside the subject. [^]

- We thank one of the reviewers for having pointed this out to us. [^]

- Another noteworthy case involves a missing object that is part of a V-NP idiom together with the infinitive:

As Ruwet (1983: 40–47) notes, this property of idioms is shared with participial passives. Although we do not provide a sample analysis of such cases, it should be sufficiently clear that these cases are easily captured by the passive-like approach we defend here. [^]

- (i)

- Ruwet (1983: 42), our gloss and translation

- La

- the

- soirée

- evening

- s’annonçait

- promised to be

- sinistre,

- sinister

- mais,

- but

- grâce

- thanks

- à

- to

- ce

- this

- boute-en-train

- jolly fellow

- de

- of

- Gaston,

- Gaston

- la

- the

- glace

- ice

- a

- has

- été

- been

- facile

- easy

- à

- to

- briser.

- break

- ‘The evening promised to be dreadful, but thanks to that jolly fellow Gaston the ice was easy to break.’

Acknowledgements

Some of the ideas presented here have been presented at the 13th Colloque de Syntaxe et Sémantique à Paris (CSSP 2019). We are highly grateful to the audience of that event for extensive discussion of the data and our proposal, in particular Marianne Desmets, Danièle Godard, Philip Miller, Adam Przepiorkowski, Laurent Roussarie and Manfred Sailer. Furthermore, a great many thanks go to Anne Abeillé and Jean-Pierre Koenig for discussing various aspects of this work at several occasions. All remaining errors are of course ours.

Funding information

This work has been supported by a doctoral grant from U Paris to Gabrielle Aguila-Multner and has also benefited from a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the program “Investissements d’Avenir” (reference: ANR-10-LABX-0083). It contributes to the IdEx Université Paris Cité, Laboratoire de linguistique formelle, CNRS – ANR-18-IDEX-0001. Authors’ names are listed in alphabetical order.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Abeillé, Anne & Bonami, Olivier & Godard, Danièle & Tseng, Jesse. 2006. The syntax of French à and de: an HPSG analysis. In Saint-Dizier, Patrick (ed.), Syntax and semantics of prepositions, 147–162. Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3873-9_10

Abeillé, Anne & Godard, Danièle. 2002. The syntactic structure of French auxiliaries. Language 78(3). 404–452. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2002.0145

Abeillé, Anne & Godard, Danièle (eds.). 2021. La grande grammaire du français. Éditions Actes Sud.

Abeillé, Anne & Godard, Danièle & Miller, Philip & Sag, Ivan. 1998. French bounded dependencies. In Dini, Luca & Balari, Sergio (eds.), Romance in HPSG, 1–54. Stanford: CSLI publications.

Aguila-Multner, Gabrielle & Crysmann, Berthold. 2020. French clitic climbing as periphrasis. Lingvisticæ Investigationes 43(1). 23–61. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/li.00039.agu

Baroni, Marco & Bernardini, Silvia & Ferraresi, Adriano & Zanchetta, Eros. 2009. The WaCky wide web: a collection of very large linguistically processed web-crawled corpora. Language resources and evaluation 43(3). 209–226. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-009-9081-4

Dalrymple, Mary & King, Tracy Holloway & Butt, Miriam. 2000. Missing-object constructions: Lexical and constructional variation. In On-line proceedings of the LFG2000 Conference.

Fleisher, Nicholas. 2008. A crack at a hard nut: Attributive-adjective modality and infinitival relatives. In Proceedings of the 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, vol. 91, 163–171.

Giurgea, Ion & Soare, Elena. 2007. When are adjectives raisers? tough to get it. In Falk, Yehuda (ed.), Proceedings of the Israel Association of Theoretical Linguistics (IATL) 23. Tel Aviv University.

Grover, Claire. 1995. Rethinking some empty categories: University of Essex dissertation.

Hukari, Thomas E. & Levine, Robert D. 1987. Rethinking connectivity in unbounded dependency constructions. In Crowhurst, Megan (ed.), Proceedings of the Sixth West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. 91–102. Stanford: Stanford Linguistics Association.

Jakubíček, Miloš & Kilgarriff, Adam & McCarthy, Diana & Rychlý, Pavel. 2010. Fast syntactic searching in very large corpora for many languages. PACLIC 741–47.

Kayne, Richard. 1974. French relative que. Recherches Linguistique de Vincennes II, 40–61.

Kayne, Richard. 1975. French relative que. Recherches Linguistique de Vincennes III, 27–92.

Kayne, Richard. 1977. Syntaxe du français: le cycle transformationnel. Ed. du Seuil.

Kilgarriff, Adam & Baisa, Vít & Bušta, Jan & Jakubíček, Miloš & Kovář, Vojtěch & Michelfeit, Jan & Rychlý, Pavel & Suchomel, Vít. 2014. The Sketch Engine: ten years on. Lexicography, 7–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9

Kilgarriff, Adam & Rychlý, Pavel & Smrž, Pavel & Tugwell, David. 2004. Itri-04-08 the sketch engine. Information Technology.

Ko, Kil Soo. 2010. La syntaxe du syntagme nominal et l’extraction du complément du nom en coréen: description, analyse et comparaison avec le français: Paris 7 dissertation.

Lee, Sun-Hee. 2003. Korean tough constructions and double nominative constructions. In Kim, Jong-Bok & Wechsler, Stephen (eds.), The proceedings of the 9th international conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar, 187–208. Stanford: CSLI Publications. http://cslipublications.stanford.edu/HPSG/3/. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21248/hpsg.2002.10

Müller, Stefan & Ørsnes, Bjarne. 2013. Towards an HPSG analysis of object shift in Danish. In Morrill, Glyn & Nederhof, Mark-Jan (eds.), Formal Grammar: 17th and 18th International Conferences, FG 2012, Opole, Poland, August 2012, Revised Selected Papers, FG 2013, Düsseldorf, Germany, August 2013. Proceedings (Lecture Notes in Computer Science 8036). 69–89. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York, NY: Springer Verlag. http://hpsg.fu-berlin.de/~stefan/Pub/object-shift.html.

Pollard, Carl J. & Sag, Ivan A. 1994. Head-driven phrase structure grammar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ruwet, Nicolas. 1976. Note sur la montée de l’objet. Recherches linguistiques de Saint-Denis IV. 185–208.

Ruwet, Nicolas. 1983. Du bon usage des expressions idiomatiques dans l’argumentation en syntaxe générative. Revue québécoise de linguistique 13(1). 9–145. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7202/602507ar

Ryu, Byong-Rae. 2013. Multiple case marking as case copying: A unified approach to multiple nominative and accusative constructions in Korean. In Müller, Stefan (ed.), Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Freie Universität Berlin, 182–202. http://cslipublications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2013/ryu.pdf. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21248/hpsg.2013.10

Sagot, Benoît. 2010. The Lefff, a freely available and large-coverage morphological and syntactic lexicon for French. In 7th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2010).