1 Introduction

I will begin with a reminder of what it means for an attitude to be de se: a notion that has been discussed in detail in works such as Lewis (1979), Chierchia (1990), Anand (2006) and Pearson (2018), among many others. Take a context in which Caitlin looks into a mirror to dress up for an event and she thinks to herself “wow, I look beautiful.” Paired with such a context, it is felicitous to use (1) below; after all, this is the usual way in which a sentence like (1) would be read. As such, the pronoun she in (1) is a pronoun read de se; such pronouns are interpreted from the first-personal perspective of the attitude holder, which is Caitlin in (1).

- (1)

- Caitlin believes that she looks beautiful.

A sentence like (1) seems prima facie to be acceptable, however, even if Caitlin is not self-attributing the property of being beautiful to herself. Take a context in which a photo of Caitlin had been taken before the date; decades have passed since the photo was taken, and Caitlin has gone senile. She sees the photo of herself and thinks “wow, the girl in that photo is beautiful!” rather than “I look beautiful.” These two beliefs are different, even though the two pronouns end up referring to the same person. Under such a context, she in (1) would be read de re. In contrast to one read de se, it is not interpreted from the first-personal perspective of Caitlin.

With the de se vs. de re distinction in mind, we now have the theoretical tools needed to help understand the intricacies that arise with the predicate dream. This predicate is interesting as it shows that we can take the first-personal perspective of someone else; in other words, we can experience the world in someone else’s shoes. Imagine that you have a dream in which you are Biden during the 2020 election, and Biden beats Trump in the dream. Under such a context, it is felicitous to use (2), even though you, the reader, are most likely not Biden in the real world.

- (2)

- I dreamed that I was Biden and I defeated Trump.

It is possible for you to have the perspective of Biden in dream-worlds. Biden, then, is your dream-self, a notion we will be coming back to throughout this paper. But as Lakoff (1972) has pointed out, even if your dream-self is Biden, it is possible for your bodily counterpart to appear in the dream, but in the third-person. Let us call this your real-self. Imagine that your real-self is running for President, and Biden, your dream-self, is running for Vice President; your real-self beats Trump in the dream. (2) can be felicitously paired with such a context. The first conjunct rules out a potential ambiguity, making it clear that the dream-self is different from the real-self.

The dream- and real-selves can therefore be different, leading to interesting semantic consequences. A dream-self need only be a mental counterpart to you, while your real-self need only be a bodily counterpart. Of course, in most dreams, mental and bodily counterparts overlap. But we have seen that the first-person pronoun can refer to either the mental or the bodily counterpart. Furthermore, given that in the dream, the mental counterpart is just the one which you have the first-personal perspective of, this is also your de se counterpart. The bodily counterpart is your de re counterpart. In other words, the first-person pronoun which refers to the dream-self is pronoun read de se, while one which refers to the real-self is read de re.

Percus & Sauerland (2003b) points out an asymmetry that arises when we have two pronouns, one referring to the dream-self and the other to the real-self, in the same sentence, like in (3) in which one pronoun c-commands the other. They note that there are three possible readings while one is dispreferred. We will be focusing on the readings in bold, 2 and 4, in this paper:

- (3)

- Possessor blocking: I dreamed that I was Trump and I kissed my daughter.

- Possible reading 1: In the dream, Trump kissed Ivanka. (de se kissed de se’s d)

- Possible reading 2: In the dream, Trump kissed my daughter. (de se kissed de re’s d)

- Possible reading 3: In the dream, I kissed my daughter. (de re kissed de re’s d)

- Less plausible reading 4: In the dream, I kissed Ivanka. (de re kissed de se’s d)

Let us call this instance “possessor blocking.” Such contrasts have been verified experimentally by Pearson & Dery (2013) via picture choice tasks, though I use context-sentence pairs instead in this paper. Anand (2006) expands this to configurations like I kissed me, which are unacceptable unless in dream-contexts, as Arregui (2007) points out. Principle B does not apply here. With I kissed me, we obtain the same contrast as in (3) above: we again find that (4) is best paired with a context in which the dream-self (de se) is the one kissing the real-self (de re).

- (4)

- Generic blocking: I dreamed that I was Biden and I kissed me.

- Possible reading: In the dream, Biden kissed me. (de se kissed de re)

- Less plausible reading: In the dream, I kissed Biden. (de re kissed de se)

Let us call such instances “generic blocking.” We will get further into the details of each account in the next section, but the generalization, following Anand (2006), seems to be more general than just dream, as such contrasts arise in other languages as well, with constructions that have other obligatorily de se anaphors. So Anand defines the de re blocking effect as follows: an obligatorily de se anaphor cannot be c-commanded by its de re counterpart.

Works such as Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and Anand (2006) have attempted to come up with accounts for this–ranging from movement and agreement to an independently defined binding constraint–but I will argue that neither can account for the novel pieces of data presented in this paper. Based on experimental evidence, I will show that there are at least some instances of the de re blocking effect which cannot be accounted for via syntactic accounts that appeal to c-command or locality.

For example, let us take (4) and invert the position of the pronouns–by passivizing the embedded clause. I provide experimental evidence in this paper indicating that we have the same blocking configuration as in (4); the existing accounts which rely on syntactic constraints would predict the opposite pattern:

- (5)

- Passive blocking: I dreamed that I was Biden and I was kissed by me.

- Possible reading: In the dream, Biden kissed me. (de se kissed de re)

- Less plausible reading: In the dream, I kissed Biden. (de re kissed de se)

Another example involves a configuration where blocking seems to arise even if the two pronouns are not in the same clause, as long as they are semantically connected.1 Empirical evidence indicates that blocking does not arise in configurations like I said that I ate a Big Mac; I propose this is because fire is a performative utterance:

- (6)

- Blocking across clauses: I dreamed that I was Biden and I said that I was fired.

- Possible reading: In the dream, Biden fired me. (de se vs. de re)

- Less plausible reading: In the dream, I fired Biden. (de re vs. de se)

We will refer to such instances as “blocking across clauses.” Anand’s definition of the de re blocking effect (DRBE) predicts such asymmetries might arise outside of the same clause, but Percus & Sauerland (2003b), for example, cannot straightforwardly derive blocking outside clause boundaries. Furthermore, the fact that this blocking appears to be lexical cannot be derived by either account.

The experiment confirms the instance of possessor blocking that was originally reported by Percus & Sauerland (2003b) seen above, in addition to instances of generic blocking noted by Anand (2006). But one unexpected finding of the experiment is given in (7) below, in which the possessor is now embedded inside the subject rather than the object. As it turns out, it is more acceptable for the de re counterpart’s daughter to fire the de se self, rather than the de se counterpart’s daughter firing the de re self.

- (7)

- Inverted blocking with possessors

- I dreamed I was Trump and my daughter fired me.

- Possible reading: In the dream, my daughter fired Trump. (de re’s d fires de se)

- Less plausible reading: In the dream, Ivanka fired me. (de se’s d fires de re)

My primary goal in this short paper is to show that Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and Anand (2006)’s accounts are not sufficient. I present the experiment which provides the evidence that the novel instances of the de re blocking effect seen above exist. I provide theoretical discussion by exploring an alternative in which it arises via thematic restrictions–which would be a very natural analysis of passive blocking seen above, for example. I ultimately conclude that there is currently no single satisfactory analysis of the de re blocking effect–a mixture of the syntactic and thematic theory would be able to attain most, if not all of the instances of blocking.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, I introduce the reader to the concepts needed to fully understand the paper. Section 3 provides experimental evidence that the de re blocking effect actually does take place in the instances of blocking seen above. Section 4 concludes that the novel instances of blocking, if they do exist as I have argued, cannot be accounted for via existing accounts. Section 5 concludes.

2 Background

The goal for this section is to give the necessary background to understand the data and its discussion in sections 3 and 4. I first introduce the reader to the primary semantics for pronouns read de se that will be used in this paper in 2.1, and discuss an alternate approach. I provide a brief introduction to de re semantics in terms of concept generators in 2.2. I then go into detail on two of the papers mentioned in the introduction prior: Percus & Sauerland (2003b) in 2.3, and Anand (2006) in 2.4.

2.1 The semantics of de se

It is clear that (1) has different truth-conditions depending on whether the pronoun is read de se or de re. Therefore, (1) has a different semantics based on which kind of pronoun is present: but how exactly does it differ? I must first provide the background on some necessary notions.

Centered worlds are pairs <w, x> consisting of a possible world w and an entity x present in w. Imagine that we are presenting the matrix subject, say Caitlin, pairs of worlds and entities (in other words, centered worlds) and asking them whether they could be entity x in world w. The centered worlds to which Caitlin would say yes to are called the doxastic alternatives, often used in the semantics for a predicate like believe:

- (8)

- Doxx,w = {<w’, y>: it is compatible with what x believes in w for x to be y in w’}

We will get into the denotation of believe in the next subsection. In a semantics for de se attitude reports like Lewis (1979)’s, the de se LF of (1)–Caitlin believes that she looks beautiful–is as follows. This LF states that Caitlin consciously self-ascribes the property of looking beautiful:

- (9)

- ∀<x,w’> ∈ DoxCaitlin, w: x looks beautiful in w’

This LF will not hold in a de re scenario, because Caitlin does not identify herself in those centered worlds. Now, we can see that she can be interpreted either de se or de re. But some anaphoric elements are obligatorily read de se. For example, this is the case for PRO, as Chierchia (1990) notes in his account of de se, inspired by Lewis (1979). It cannot be read de re, indicating that PRO is an obligatorily de se anaphor:

- (10)

- Jack is a high school student who has lost all of his memories. He watches a video of a high school student solving a very difficult math problem in front of all of his classmates, and the teacher congratulates that student. Jack thinks to himself “that student is very clever!” But that student is actually Jack himself, though Jack doesn’t know it.

- #Jack claimed to be clever.

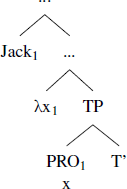

To derive the necessity of this reading, Chierchia used a lambda abstractor base-generated into the left-periphery of the embedded clause; PRO itself is a bound variable:

- (11)

Abstraction operators bind coindexed variables at LF just in case they are of the same type. The matrix subject itself does not bind PRO; PRO is bound by an individual abstractor. The lexical entry for claim is given in (12), where (12b) is the embedded clause built-up from the bottom up and (12c) is the matrix clause:

- (12)

- a.

- ⟦claim⟧c,g = λP<e,<st>>λxeλws.∀<w’,y> ∈ claimx,w: P(y)(w’) where claimx,w = {<w’,y>: what x claims in w is true w’ and x identifies herself as y in w’}

- b.

- ⟦CP2⟧c,g = λx. λw. x is clever in w

- c.

- ⟦CP1⟧c,g = λw. ∀<w’,y> ∈ claimJack,w: y is clever in w’ (Pearson 2015: 82)

This semantics is based on Hintikka (1969)’s semantics for attitude reports where the content of an attitude is not a set of worlds. Chierchia and Pearson’s semantics makes it possible for one to bear an attitude de se towards a property just in case that property is self-ascribed. This is because the attitude predicate quantifies over centered worlds rather than worlds. We need not always use doxastic alternatives in the lexical entry for attitude verbs: for example, for claim, these are the sets of claim-alternatives <w’,y> such that it is compatible with the attitude holder saying she is y in w’.

Again, the definition given in (12) entails that the attitude holder would be willing to refer to the person in the claim-alternative worlds as herself, and this is not the case in a de re scenario.

Chierchia’s account is one of the major LFs given for de se binding in the literature. But another is worth discussing briefly, too. As Lewis (1979), Schlenker (2005) and Anand (2006) among others suggest, de se ascription could just be a kind of de re ascription with a special self-identity acquaintance relation, rendering the approach just seen potentially superfluous:

- (13)

- Caitlini wants of herselfi, under self-identity, [CP shei is beautiful.]

This account differs from the one above in that Chierchia has a dedicated LF for de se binding. In this account, the de se reading is reduced to the same LF as de re, for which we will discuss a treatment of concept generators in the next subsection. Therefore, de se-as-de re readings involve a concept generator as well, so under this account, de se is called a special kind of de re. Furthermore, this indicates that complements of attitude predicates are propositions rather than properties, contra the account just seen, where a property is de se if it is self-ascribed.

Although this seems to reduce de se to de re and may seem like a desirable consequence, several have noted that this approach makes incorrect predictions, and is not enough on its own. This has led some authors, such as Anand (2006), to argue that the property and the concept generator approach to de se LFs are both needed to account for the presence of the de re blocking effect with dream but not with other predicates. Similarly, Pearson (2018) has argued that de se as de re cannot account for counterfactual reports involving counter-identity, and dedicated de se binding is needed for these instances. We now discuss the LFs of de re readings.

2.2 Concept generators for de re LFs

The semantics of de re attitudes has been discussed in great detail in the literature. But for our purposes it suffices to discuss the notion of a concept generator, which allows for the DP associated with the res to remain in situ–the res being the individual the de re attitude is about. As Anand (2006) and Charlow & Sharvit (2014) have pointed out, it is problematic to assume that the res moves covertly. I will then assume, following Percus & Sauerland (2003a) that de re attitude ascription involves concept generators, which has been further defended by Anand (2006) and Charlow & Sharvit (2014).

I define concept generators as follows, following Charlow & Sharvit (2014):2

- (14)

- G is an acquaintance-based concept generator for x in w iff:

- a.

- G is a function from entities to centered concepts of type <e, <s, <e, e>>>

- b.

- For all y, G(y) is an acquaintance-based y-concept for x in w

A concept generator is a function which takes a res as an argument, and outputs a centered concept, which is a function from a centered world to an entity.3 It is therefore a function of type <e, <s, <e, e>>>. For example, if (1) is paired with the de re context provided, then Caitlin may be associated with the following centered concept:

- (15)

- [λw. λx. the girl x saw in the photo in w]

In concept generators, the centered concept outputs the res when two things are applied to it: the ordered pair of the actual world, and the attitude holder is applied to it. The res itself is embedded covertly in a resP, which contains a variable over concept generators that is abstracted over:

- (16)

- Caitlin believes that [λG [[resP G she] is beautiful]].

Note that this is simplified: there are two more variables present in the resP that are abstracted over. Percus & Sauerland (2003a) assume, further, that syntactic structures contain variables over possible worlds and abstractors over these variables. In addition, there is also an individual abstractor, and a covert individual pronoun present in the resP, as well.

All of this ensures that the constituent resP contributes a certain individual; namely the one which is associated with the concept at each of the centered worlds that are quantified over by the attitude predicate. A more precise LF of (1) is given below:

- (17)

- λw. Caitlin in w believes [λG. λx. λw’. [resP G she w’ x] is beautiful in w’]

Believe is analyzed a two-place predicate, which takes a concept generator and the attitude holder (ex. Caitlin) as an input, and returns a proposition. It is therefore of type <esee, <e, st>>. Believe is then an existential quantifier over concept generators, whose denotation is given:

- (18)

- ⟦believe⟧w, g = λP<esee, est>. λx. λw. ∃G: G is an acquaintance-based concept generator for x in w & ∀<w’, y> ∈ Doxx,w: P(G(x))(y)(w’) = 1]

Together with this semantics for believe, after the LF given in (17) above is fully computed, we are left with the truth conditions as follows:

- (19)

- λw. ∃G: G is an acquaintance-based concept generator for Caitlin in w & ∀<w’,x> ∈ DoxCaitlin, w: G(Caitlin)(x)(w’) is beautiful in w’

We can now provide a semantics for dream, following Anand (2006). With this treatment of concept generators in mind, an attitude predicate like believe or dream is a function which takes functions from concept generators to properties as inputs:

- (20)

- ⟦dream⟧w, g = λP<esee, est>. λx. λw. ∃G: G is an acquaintance-based selfless concept generator for x in w & ∀<w’, y> ∈ dreamx,w: P(G(x))(y)(w’) = 1

The basic idea is that a pronoun read de se cannot be a special case of de re in dream-complements. This is what will enable the DRBE to arise under Anand (2006)’s account.

2.3 The Oneiric Reference Constraint

As mentioned in the introduction, the use of dream reports allows us to shed further light on the de se and de re distinction. This is because a pronoun referring to the dream-self, despite clearly being a different person from the dreamer, is interpreted de se. This entails that a pronoun referring to the real-self in a dream, if distinct from the dream-self, will be de re. I repeat (4) in (21) below, in which we see that the pronoun denoting the real-self cannot c-command the one for the dream-self in the same clause.

- (21)

- I dreamed that I was Biden and I kissed me.

- Possible reading: In the dream, Biden kissed me. (de se kissed de re)

- Less plausible reading: In the dream, I kissed Biden. (de re kissed de se)

Percus & Sauerland (2003b) note that a sentence like (21) can in fact express two more possibilities than the ones noted above.4 We have seen that the dream-self may kiss the real-self. Another alternate reading for (21) is that the dream-self kisses himself, or for the real-self to kiss him or herself. These possibilities for (21) are represented below (the real-self in the first person):

- (22)

- a.

- In my dream, the dream-self kisses me. (de se + de re)

- b.

- In my dream, the dream-self kisses himself. (de se + de se)

- C.

- In my dream, I kiss myself. (de re + de re)

- d.

- #In my dream, I kiss my dream-self. (de re + de se)

The only combination of the de re vs. de se forms that is ruled out is the one in which the de re form c-commands the de se form. Their Oneiric Reference Constraint is defined as follows:

- (23)

- Oneiric Reference Constraint(ORC) (Percus & Sauerland 2003b: 5)

- A sentence of the form X dreamed that … pronoun … allows a reading in which the pronoun has the dream-self as its correlate only when the following condition is met: some pronoun whose correlate is the dream-self on the reading in question must not be asymmetrically c-commanded by any pronoun whose correlate is X.

Of course, this alone isn’t enough to account for the distribution given in (22); we would prefer to explain why the ORC is present. To do so, they make two crucial assumptions. Following Chierchia (1990), they assume that dream has a denotation which selects for properties rather than propositions. Their definition is given below:

- (24)

- ⟦dream⟧g = λP. λx. λw. ∀<y,w’> in dreamx, w, P(y)(w’) = 1.

They further assume that de se pronouns bear a special diacritic, represented by *. This moves the pronoun to the left-periphery of the embedded clause complement of the attitude verb. A lambda abstractor that binds the trace is inserted by movement, deriving Chierchia (1990)’s semantics of the de se pronoun. The crucial difference is that under this account, the de se semantics is generated via movement, but base-generated on Chierchia’s account.

The blocking effect seen in (22d) is analyzed as an instance of Superiority. The lower de se pronoun, c-commanded by the de re pronoun, cannot move, because the de re pronoun is a closer potential Goal for the probe P:

- (25)

- *I λf dreamed [CP me* λx H If kissed tx]

The movement constraint explicitly refers to morphological features such as first- or third-person features, noting that there are restrictions on what morphological features a pronoun can have. This can be seen in the contrast in (26): the form of the bound pronoun must match up with the argument of only.

- (26)

- Context: I did my homework, but no one else did his homework.

- a.

- Only I did my homework.

- b.

- *Only I did his (or her) homework.

This is despite the seeming fact that the morphological features of bound pronouns are not interpreted (ex. the person feature of my). It seems that bound variable pronouns must share features with the complement of only; they extend this reasoning to de se pronouns in dream-complements, as well. As such, the ORC is derived by reference to movement and agreement.

2.4 The de re blocking effect

Anand argues that the ORC just presented is not general enough. He notes that the ORC bears a striking resemblance to an interaction between logophoric and non-logophoric pronouns in Yoruba, first pointed out by Adesola (2006). Ordinary pronouns (o-forms) cannot c-command the logophoric pronoun òun under coreference–logophoric pronouns are usually obligatorily read de se. This is despite the fact that ordinary pronouns and logophoric pronouns may both co-occur in the same logophoric environment (as the subject of an attitudinal embedded clause).

- (27)

- Olui

- Olu

- so

- say

- pé

- that

- o*i/j

- 3sg

- ri

- see

- bàbá

- father

- òuni.

- log

- ‘Olui said that he*i/j had seen hisi father.’

As Anand points out, if we trade the logophoric pronoun for the dream-self (de se) and the ordinary pronoun for the real-self (de re), these two puzzles seem to be the same. As such, he defines the de re blocking effect below, which is the most crucial notion for this paper:

- (28)

- De re blocking effect

- No obligatorily de se anaphor can be c-commanded by a de re counterpart.

Based on this, one prediction that we would make is that obligatorily de se logophors in other languages would also undergo the de re blocking effect. This prediction is borne out with ziji in Chinese and ordinary pronouns:5

- (29)

- Zhangsani

- Zhangsan

- renwei

- think

- Lisij

- Lisi

- gei

- give

- tai

- 3sg

- ziji*i, j-de

- self-poss

- shu.

- book

- ‘Zhangsani thinks that Lisij gave himi his*i, j book.’ Anand (2006)

Pan (1997) and Huang & Liu (2001), among others, points out that ziji, like PRO, is an obligatorily de se anaphor. When paired with a de re context, Huang & Liu (2001) reports that the sentence below is unacceptable:

- (30)

- Zhangsan says: “that thief stole my purse!” without knowing that it is his purse.

- a.

- #Zhangsani

- Zhangsan

- shuo

- say

- pashou

- pickpocket

- tou-le

- steal-perf

- zijii-de

- refl-de

- pibao.

- purse

- ‘Zhangsani said that the pickpocket stole hisi purse.’ Huang & Liu (2001)

The notion of a “de re counterpart” is supposed to be inclusive enough to include bodily counterparts with dream and ordinary pronouns. Anand offers another method to derive the de re blocking effect, arguing that it is not via Superiority. He first notes that it seems unclear how Percus & Sauerland’s derivation of the ORC via movement and agreement could apply to the cases we have just seen in Yoruba and Chinese without major modifications to their syntactic assumptions.

Under Anand’s semantics, dream selects for a CP headed by the logophoric operator OPlog, an individual abstractor. Anand’s basic idea is that there is competition between two potential binders of de se me, as shown below:

- (31)

- I dreamed OPlog λx I λy I fired melogx. (λx binds me, non-local)

- (32)

- I dreamed OPlog λx I λy I fired melogx. (λy binds me, local)

The logophoric operator would skip past the subject to bind the object in the non-local configuration, so this is not preferred over the de re embedded subject binding the de se object. To derive this contrast, Anand appeals to a modification of Fox (2000)’s Rule H, so that de se vs. de re interpretations are not included, allowing it to rule out the non-local configuration:

- (33)

- Rule H (mod de se, simplified)

- A variable, x, cannot be bound by antecedent, A, in cases where a more local antecedent, B, could bind x and yield the same semantic interpretation.

I now present experimental evidence for the DRBE potentially being present in novel contexts.

3 Data

In this section, I present the experiment that provides the empirical foundation for this paper. The goal of this experiment is to first establish that the DRBE really does exist in the cases that were originally reported in the literature: generic blocking and possessor blocking. I then establish the three novel cases, all of which involve the predicate dream.

The experiment was a survey with context-sentence pairs–a context together with a sentence–and participants were asked to judge the naturalness of a sentence paired with its context, on a Likert scale from 1 (very unnatural) to 6 (very natural). To keep the survey as short and as simple as possible, the survey had no more than seven questions visible to the participant. Furthermore, the survey began with two practice examples explaining the notion of naturalness, which were the following:

- (34)

- John and Mary are school kids. John complains that Mary kicked him.

- a.

- Natural: John said that Mary kicked him.

- b.

- Unnatural: John said that Mary kicked himself.

- (35)

- I asked my wife what time it is.

- a.

- Natural: What time is it?

- b.

- Unnatural: What time it is?

The survey was conducted on Qualtrics and participants were recruited from Prolific; a custom prescreening for native English speakers was applied to ensure that someone who is not a native speaker of English could not take the survey.

To ensure that each survey had the highest quality answers possible, some answers were discarded; the criteria for both experiments was the same. The first criteria was, if the participant gave every context-sentence pair the same score, their answer was automatically discarded. This is not an arbitrary criteria of exclusion because in each case this happened, the participant completed the survey significantly quicker than the median time. This indicates that the participant did not pay full attention to the survey, and therefore, their answers ought not to be used.

The second criteria was based on the participant’s judgment of a baseline sentence, which was the first question of the survey. Baseline context-sentence pairs are used to ensure that participants understand the experiment, and filter out the participants who did not understand it. If a participant gave a naturalness judgment of 2 or 1 on a baseline sentence that is clearly acceptable to native speakers, then the entire set of their answers was automatically discarded.

Finally, p < 0.0001 was determined to be significant. P-values were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, in which two sets of data are paired, because the responses are on a scale and do not follow a normal distribution.

3.1 Experimental Design

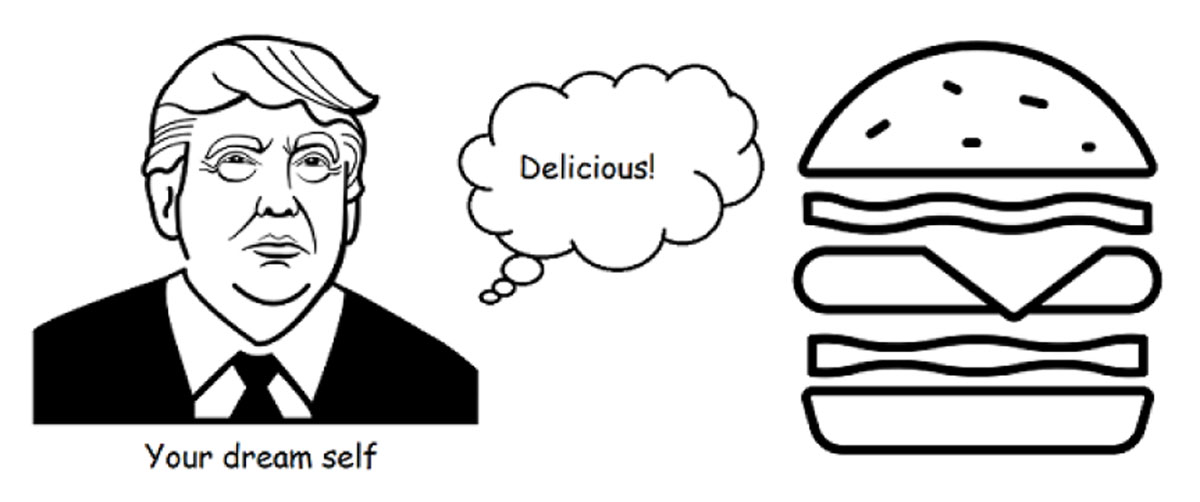

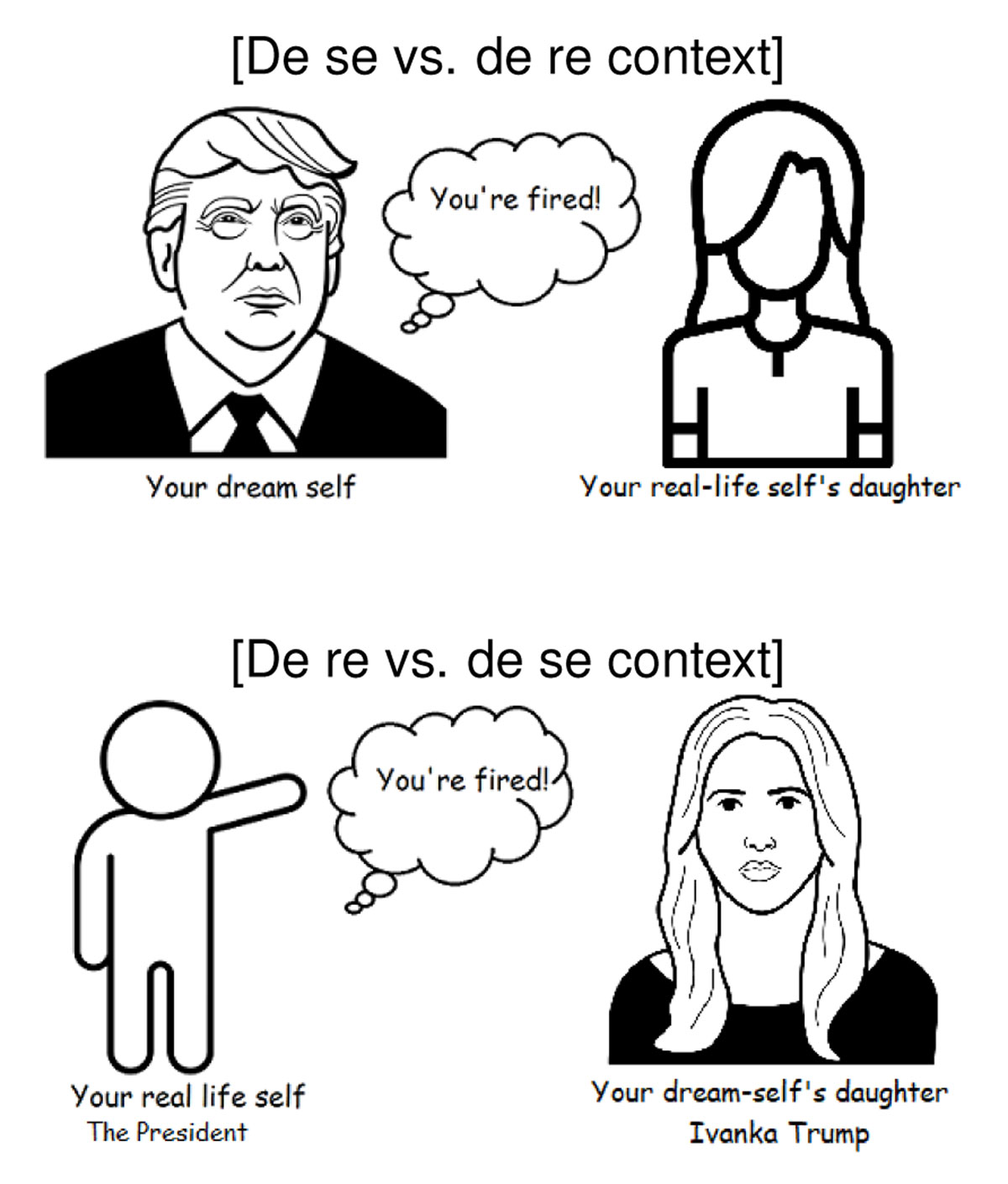

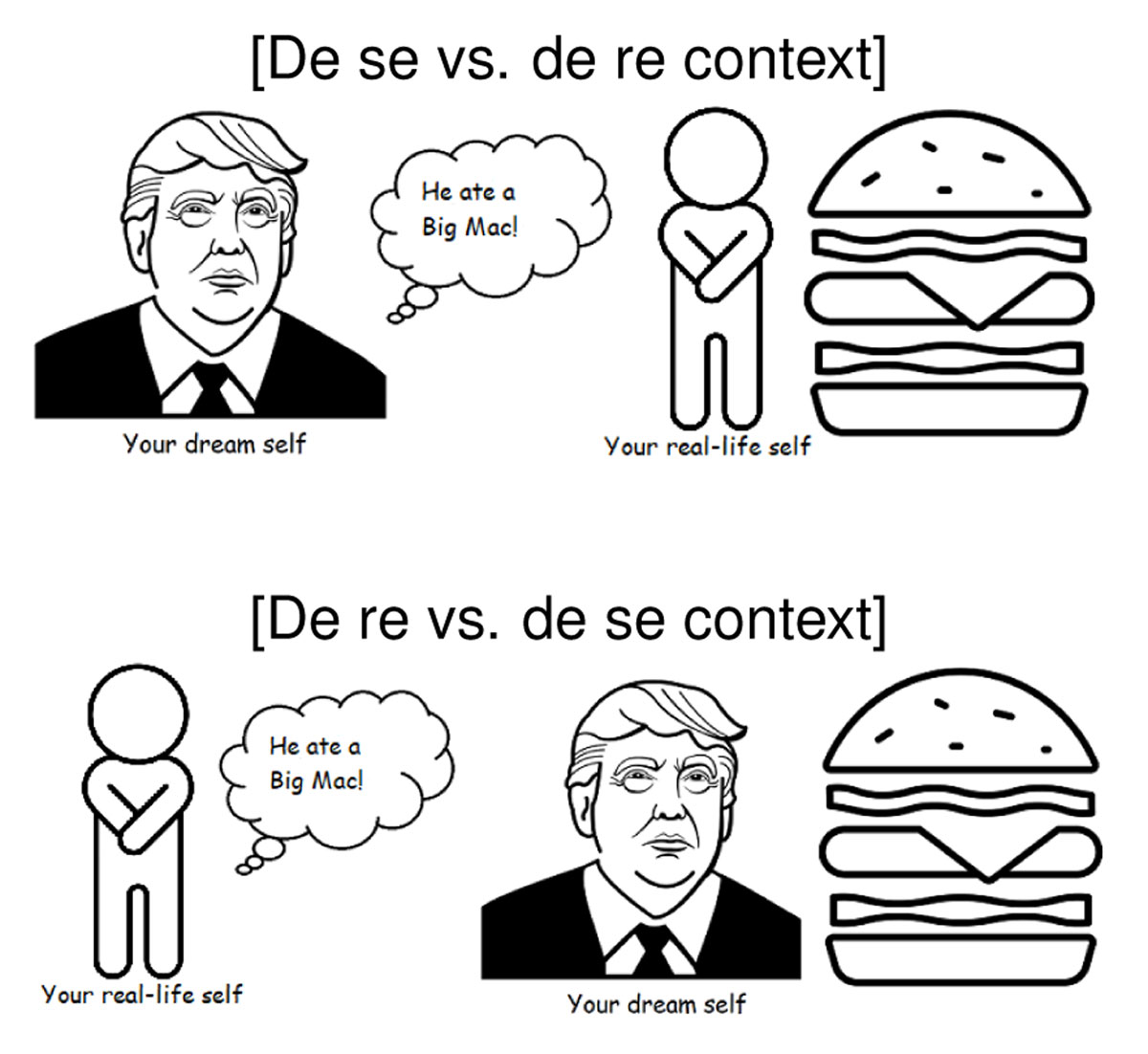

In addition to context-sentence pairs, pictures such as those in Figure 1 following were paired together with all of the contexts apart from two, to make the experiment more understandable.

The image of Donald Trump was used, and the participant was asked to imagine themselves as Donald Trump, given that he is a very well-known individual. In addition, the surveys consisted of similar sentences for the same scenarios to make it easier for the participant to conceive of the context-sentence pairs, and just focus on the difference in acceptability between the same contexts. This experiment consisted of a few baseline context-sentence pairs. The first was “I dreamed I was Donald Trump and I ate a Big Mac,” which was paired with the following image in Figure 2. Anyone who gave this pair a 2 or 1 was automatically rejected, given that the sentence is intuitively clearly acceptable to native English speakers.

In the first survey, two baseline questions to establish generic blocking were asked: “I dreamed that I was Trump and I fired me” was paired with readings in which the dream-self c-commanded the real-self, as seen in (a) of Figure 1, and vice versa, as seen in (b) of Figure 1. Two questions to test blocking across clauses, “I said I was fired” were asked, and paired with Figure 1.

One potential problem with this experiment is using the verb fire together with the character of Trump, as Donald Trump is an individual who is associated with firing people. The asymmetry may arise simply because it is difficult for the participant to imagine Trump being fired, rather than doing the firing. To eliminate this possibility, I included 2 questions for a context-sentence pair with the predicate kiss rather than fire, expecting the results to not differ significantly.

All of the questions of the survey were ordered randomly. Furthermore, not all participants saw every question: there was a 50/50 chance that each participant would see either “I fired me” or “I kissed me.” However, all of the participants did see “I said I was fired” and “I was fired by me.” This is because, as I will discuss in section 4, the blocking effect in blocking across clauses “I said I was fired” arises due to the unique lexical semantics of fire. Furthermore, whether there was a blocking effect in passive blocking “I was fired by me” was also tested; the prediction was that it would still be present, but inverted.

A second survey was also conducted, also with 100 separate participants. The participant could see every question, and they were randomly ordered. Instead of having a single survey with double the number of questions, a second separate survey was preferred to keep the survey as short as possible, as Prolific participants are more likely to lose focus or drop out of the survey if it is too long. This survey, for the most part, had questions involving simple possessive structures like my daughter, which I dubbed possessor blocking. This was the original configuration discussed in Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and the strongest evidence in favor of syntactic approaches like theirs. Baseline pairs involving possessor blocking were presented as follows as seen in Figure 3:

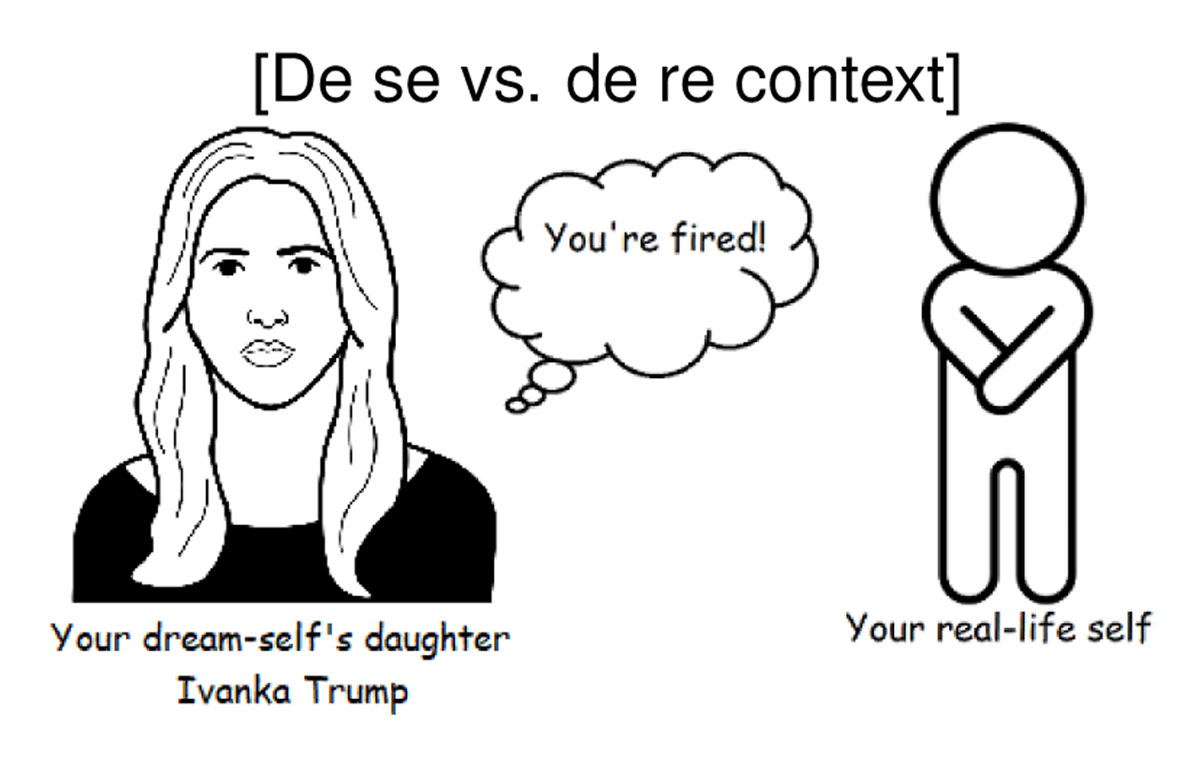

Sentences of the form I dreamed that my daughter fired me, which I call “inverted possessor blocking” were included as well, as seen in Figure 4. Under syntactic approaches to blocking like Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and Anand (2006)’s, the prediction would be that no blocking would occur, and there ought to be no significant difference between these sentences. Indeed, Percus & Sauerland (2003b) discusses such configurations, claiming that both readings below are available:

Furthermore, given that I believe it is plausible that there may be a lexical element to the DRBE in I said that I was fired, it would be important to test configurations such I said that I ate a Big Mac. Syntactic approaches which rely on locality or c-command would predict that blocking would arise regardless of the semantics of the predicate, whereas the lexical approach proposed in this paper–to be detailed further in section 4–would predict blocking would arise regardless. Here is an example of the contexts, in Figure 5 below:

My hypothesis is as follows. The DRBE should arise in cases that were originally reported in the literature, in addition to two of the novel cases: passive blocking and blocking across clauses, if there truly is a lexical element to the DRBE. These predictions were borne out:

- (36)

- Total: 9 questions (Survey 1) & 7 questions (Survey 2)

- Each sentence begins with “I dreamed that I was Trump and…”

- a.

- Baseline with dream: expected to be natural

- b.

- Baseline “I fired me” (2 questions): the de se vs. de re context-sentence pair is expected to have a higher average than the de re vs. de se context-sentence pair

- c.

- Baseline “I kissed me” (2 questions): the de se vs. de re context-sentence pair is expected to have a higher average than the de re vs. de se context-sentence pair

- d.

- “I was fired by me” (2 questions): the de se vs. de re context-sentence pair is expected to have a higher average than the de re vs. de se context-sentence pair

- e.

- “I said that I was fired” (2 questions): the de se vs. de re context-sentence pair is expected to have a higher average than the de re vs. de se context-sentence pair

- f.

- “I said that I ate a Big Mac” (2 questions): no meaningful difference expected

- g.

- Baseline “I fired my daughter” (2 questions): the de se vs. de re context-sentence pair is expected to have a higher average than the de re vs. de se context-sentence pair

- h.

- “My daughter fired me” (2 questions): no meaningful difference expected

I have left a question mark in (36h) above because it has been reported in the literature, such as Percus & Sauerland (2003b), that no blocking is present. I added this sentence into the survey to see whether the result might have some relevance.

3.2 Results and Discussion

With the crucial exception of the pattern in my daughter fired me in (36h), all of these predictions were borne out (the unpredicted result has been put in bold). This experiment was conducted with 100 participants for each of the 2 surveys. In Table 1 below, the column “de se vs. de re average” refers to the sentences that were paired with the image (a) in Figure 1. The “de re vs. de re average” column refers to the sentences that were paired with image (b).

A summary based on 200 answers. 21 discarded.

| Kind of sentence | de se vs. de re average | De re vs. de se average | Significant? |

| “I fired me” | 3.56/6 | 2.34/6 | Yes |

| “I kissed me” | 3.29/6 | 2.29/6 | Yes |

| “I was fired by me” | 3.59/6 | 2.97/6 | Yes |

| “I said that I was fired” | 3.62/6 | 2.87/6 | Yes |

| “I said that I ate a Big Mac” | 3.41/6 | 3.54/6 | No |

| “I fired my daughter” | 4.46/6 | 3.49/6 | Yes |

| “My daughter fired me” | 3.29/6 | 4.12/6 | Yes |

I merely want to show that, when there is a significant difference with the baseline cases reported in the literature by Percus & Sauerland (2003b), there is also a significant difference with my novel cases. The reader may be confused as to why the difference is so small; normally, in studies that use the Likert scale, we would expect a difference as large as three or four out of six to represent a meaningful difference. Why should a difference as small as 1/6 or even less in some cases, such as blocking with passives, prove anything? But the judgments here are very difficult. Notice that even with Percus & Sauerland (2003b)’s first reported case of I fired my daughter involves a difference of 0.97, which itself is significant (p < 0.0001). As such, it is necessary to rely on small differences like this, even if it is less than desirable. But what determines whether a difference matters is significance according to the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

For each kind of sentence, the average of the de se vs. de re context and average of the de re vs. de se context were paired and the p-value of the difference was calculated via the Wilcoxon rank sum test. In each instance, the difference between the two scores was significant at p < 0.0001, in support of my hypothesis. At the very least, my goal is to show that there is at least a significant subset of English speakers–perhaps the majority–who have blocking effects in these novel cases involving dream. And this prediction appears to be borne out. I will now discuss the consequences of this data in the next section.

4 Theoretical Discussion

I argue that neither Percus & Sauerland (2003b) nor Anand (2006) predict the existence of the potential novel cases of the DRBE. Some of these cases can be accounted for in terms of a thematic account of blocking–which would be a very natural way of analyzing passive blocking. I will show that this does not account for the full range of facts. As a result, there remains no single satisfactory analysis of the DRBE, but both analyses together can get all of the facts.

We have seen experimental evidence of the de re blocking effect arising in the cases of passive blocking, blocking across clauses and inverted possessor blocking. I will now provide LFs them:6

- (37)

- #Generic blocking (GB)

- Mirandai dreamed that [shei fired heri].

- LF: Miranda λf dreamed OPlog λx [shef fired herlogx].

- In Miranda’s dream worlds, her real-self fires her dream-self.

- A de re pronoun c-commands a de se pronoun, both of which are relative to Miranda.

- ⟦GB⟧w, g: λw. ∃G: G is a selfless concept generator for Miranda in w & ∀<w’,y> ∈ dreamMiranda, w: G(Miranda)(y)(w’) fired y in w’

- (38)

- #Blocking across clauses (BC)

- Mirandai dreamed that [shei said that [shei was fired.]]

- LF: Miranda λf dreamed OPlog λx [shef said that [shelogx was fired]].

- In Miranda’s dream-worlds, her real-self says that her dream-self is fired.

- A de re pronoun c-commands a de se pronoun, both of which are relative to Miranda.

- ⟦BC⟧w, g: λw. ∃G: G is a selfless concept generator for Miranda in w & ∀<w’, y> ∈ dreamMiranda, w: ∀<w”, z> ∈ sayG(Miranda)(w’)(y), w’: y was fired in w”

Let us begin with passive blocking, which I repeat below in (39). The passive blocking configuration has an identical LF to the one of generic blocking in (37) above.

- (39)

- Passive blocking: I dreamed that I was Biden and I was kissed by me.

- Possible reading: In the dream, Biden kissed me. (de se kissed de re)

- Less plausible reading: In the dream, I kissed Biden. (de re kissed de se)

It is easy to see why the passive blocking facts are problematic for both existing theories. The de re blocking effect is identical to that of generic blocking, yet the pronouns have changed place. Yet, it looks like the DRBE still arises.

Now, it may prima facie seem possible for Percus & Sauerland (2003b) or Anand (2006) to rely on base-generated positions for blocking to occur. If a defender of these theories assumes a form of UTAH like Baker (1988)–in which all Agents and Themes are base-generated in the exact same position, so Agents will always c-command Themes–this could be possible.

However, recall that under Chomsky (1995)’s Minimalist Program, trees are built bottom up and all syntactic operations like passive formation have already taken place before being transferred to LF. In other words, the syntax of the passive that is sent to LF for semantic interpretation–in which the Theme c-commands the Agent–is what is semantically interpreted, has the following basic form, simplified greatly:

- (40)

- I dreamed that Ii was tk kissed ti by mek.

Given that the syntactic relations that the pronouns have to each other have already been inverted when they are shipped to LF, both Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and Anand (2006) would have to stipulate that the copies of the pronouns post-movement are simply ignored. And it is not clear to me whether such a stipulation would be justified. Furthermore, syntacticians have commonly assumed that reconstruction is not a property of A-movement, which is what takes place in passives, since at least Chomsky (1993)–therefore, it would not be possible to stipulate reconstruction, either. Reconstruction is usually considered to be a property of A’-movement.

Moving on, recall from the experiment that I verified that a blocking effect existed across clauses with the predicate fire:

- (41)

- Blocking across clauses: I dreamed that I was Biden and I said that I was fired.

- Possible reading: In the dream, Biden fired me. (de se vs. de re)

- Less plausible reading: In the dream, I fired Biden. (de re vs. de se)

But not so with I ate a Big Mac. The fact that blocking may arise due to the lexical semantics of the predicate embedded into the complement clause of say seems difficult to derive with both Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and Anand (2006)’s approaches, both of which predict that there ought to be no difference between these cases, given the c-command relations are the same.

- (42)

- I dreamed that I was Biden and I said that I ate a Big Mac.

- Possible reading: In the dream, Biden said that I ate a Big Mac. (de se vs. de re)

- Also possible reading: In the dream, I said that Biden ate a Big Mac. (de re vs. de se)

One very natural analysis of passive blocking and blocking across clauses is the idea the DRBE may sometimes arise from thematic restrictions. Notice that in the original case, blocking was obtained when the de re argument was an Agent while the de se argument was a Theme. This still remains the case; what this indicates is that the surface syntactic structure of this sentence may sometimes not be relevant for the purposes of blocking. We could attempt to define the DRBE as follows:

- (43)

- In a configuration in which an (obligatorily) de se and a de re counterpart have a thematic relation to the same event, the de re counterpart must be a Theme.

In order to elucidate this, I must get into a brief and very simple introduction of Parsons’s θ-semantics. For example, take a sentence such as Mary fired John. This might be given an LF as follows, where there is an event e such that it is an event of firing, and Mary is the Agent of the event while John is the Theme of the event:

- (44)

- ∃e. [fire(e) & Agent(e, Mary) & Theme(e, John)]

As such, John and Mary are linked to each other, because they have a thematic relation with the same event, e. The semantics given in (44) for Mary fired John has an identical LF to the passive form of the sentence John was fired by Mary, so the links between John and Mary are the same.

We can now start to consider how blocking would apply with the definition given in (43), at least for generic and passive blocking, instead of using c-command or locality as in previous accounts. In generic blocking, the de se and de re counterparts are linked because they have each a thematic relation concerning the same event, which is an event of firing, or whatever predicate the reader chooses to substitute in. Furthermore, the de se counterpart is a Theme, while the de re counterpart is an Agent. Both generic and passive blocking are ruled out by (43): the good cases are not ruled out.

Let us move onto blocking across clauses, repeated as follows.

- (45)

- #I dreamed that Ide re said that Ide se was fired.

It is not obvious how the two pronouns in this case are linked, as they are not in the same clause. However, notice that, if in a context you meet your employee to fire them, this entails that you said that your employee was fired. To say “you’re fired” is a performative utterance which changes the social reality that the speaker is describing, by firing the listener. When the firing-person says that the fired-person is fired, it is the same event as the firing of the fired-person.

In other words, in a sentence like “My boss said that I was fired,” the boss is the Agent of the event of the firing, and the listener is the Theme of this event. When the boss says that his employee is fired, this is exactly the same event as the firing itself. This means that there is a link between the individual that was responsible for the firing, and the individual that was fired. Therefore, such a sentence has an LF just like (44), at least for the purposes of θ-relations.

This is how the de re blocking effect could be derived in blocking across clauses: with no regard to clause boundaries, blocking takes place because the de re and de se pronouns are linked due to the lexical semantics of fire. This makes a prediction that can be strong evidence for my account: the de re blocking effect shouldn’t arise past clause boundaries between anaphoric elements which are not linked. And this prediction was been confirmed in Experiment 1.

The descriptive generalization bears a striking resemblance to another one made by Jackendoff (1972) concerning reflexives, given in (46):7

- (46)

- Thematic Hierarchy Condition (THC)

- A reflexive cannot precede its antecedent on the following hierarchy:

- Agent, Experiencer > Location, Source, Goal > Theme

There are many pieces of evidence that this generalization covers. But here is one that bears resemblance to the blocking that we have just seen, in which the reflexive must be a Theme:

- (47)

- a.

- The artist painted herself in a realistic style. (Theme reflexive)

- b.

- *The artist was painted by herself in a realistic style. (Agent reflexive)

According to Ray Jackendoff (p.c.), the reason why such a hierarchy might exist is because reflexives are stereotypically are acted upon, rather than vice versa. In other words, it is difficult for one to conceive of a reflexive being an actor rather than acted upon. One natural solution, then, is to assume that de re and de se counterparts also interact with a thematic hierarchy. But before I propose such an interaction, I must discuss what thematic hierarchies are.

Since Fillmore (1968), thematic hierarchies have been used to overcome certain limitations involving traditional semantic roles like Agent, Instrument and Theme, which alone are not able to explain why Themes can sometimes be subjects but must be objects in the presence of an Agent or an Instrument. Here are illustrative examples from Fillmore (1968) (p. 33), along with the generalization that we obtain in (48):

- (48)

- If there is an Agent, it becomes the subject, otherwise if there is an Instrument it becomes the subject, otherwise the subject is the Theme or Patient.

- a.

- The door opened. (Theme/Patient subject)

- b.

- Dana opened the door. (Agent subject, Theme/Patient object)

- c.

- The chisel opened the door. (Instrument subject, Theme/Patient object)

- d.

- Dana opened the door with a chisel. (Agent subject, Theme/Patient object, instrument in PP)

- e.

- *The door opened by Dana. (Theme/Patient subject, Agent is not subject)

- f.

- *The chisel opened the door by Dana. (Instrument subject, Agent is not subject)

In (48), we see that the Theme can be the subject as long as there is no Agent or Instrument; the Instrument can be the subject as long as there is no Agent, and the Agent must be the subject, if present. This is why the final two examples in (48) are ungrammatical. As such, the following thematic hierarchy (Agent > Instrument > Patient/Theme) is able to straightforwardly account for the pattern seen in (48), together with the assumption that the argument of the verb bearing the highest-ranked semantic role must be the subject.

Although each of the hierarchies in (49) below agree with Fillmore’s general hierarchy of Agent > Instrument > Patient/Theme, there is unfortunately a great deal of disagreement as to what the correct thematic hierarchy is, as Hovav & Levin (2007) notes. Here are some examples provided by Hovav & Levin (2007), which I have simplified:

- (49)

- a.

- Fillmore (1968): Ag > Inst > Pat/Th

- (No Exp, Goal, Loc)

- b.

- Belletti & Rizzi (1988): Ag > Exp > Th

- (No Goal, Loc, Inst)

- c.

- Grimshaw (1990): Ag > Exp > Goal/Source/Loc > Th

- (Goal above Pat/Th)

- d.

- Jackendoff (1972): Ag, Exp > Loc, Source, Goal > Th

- (Loc and Goal above Pat/Th)

- e.

- Jackendoff (1990): Ag > Pat/Ben > Th > Goal/Source/Loc

- (Goal and Loc below Th, Pat above Goal, Loc, Th)

- f.

- Baker (1997): Ag > Pat/Th > Goal/Source/Loc

- (Goal and Loc below Pat/Th)

- g.

- Bresnan & Kanerva (1989): Ag > Ben > Exp > Inst > Pat/Th > Loc

- (Loc below Pat/Th)

This lack of agreement leads Newmeyer (2002) to reject that thematic hierarchies exist at all given the lack of agreement in their formulations after three decades, in spite of the ubiquity of thematic hierarchies. However, as Hovav & Levin (2007) points out, different hierarchies may be at play for different phenomena and no single hierarchy may be enough. This does not mean that we ought to get rid of the notion of thematic hierarchies entirely.

The hierarchy given in (50) below which I use for this account is identical to Belletti & Rizzi (1988)’s as seen in (49).

- (50)

- Thematic Hierarchy for De Re and De Se Counterparts (THC)

- A de re counterpart cannot precede a de se counterpart on the following hierarchy:

- Agent, Experiencer > Theme

It is still unclear as to why this hierarchy exists. It may exist simply due to conceptual factors: Tanenhaus et al. (1989) among others, suggests that verb-based thematic roles “help guide parsing decisions and mediate between discourse information, general knowledge and parsing” (p. 212)–thematic roles are simply aspects of conceptual information.8 Seen in this way, it may simply be difficult to conceive of, or process, a de se counterpart–the bearer of one’s first-personal perspective–having a thematic role lower on the hierarchy than the thematic role of the bodily (de re) counterpart. One, then, could try to extend Jackendoff’s observation concerning reflexives to de se and de re counterparts: it may be more difficult for one to conceive of a de re counterpart being an actor in an event in which the de se counterpart is also a participant, and the acted-upon.

Ultimately, though, it is clear that a thematic account of the DRBE is not enough, simply because instances of simple possessor blocking as in (3), repeated in (51) below, show that c-command is necessary at least for some instances of the DRBE. In these examples, the bearer of the thematic relation is the one who is performing an action, but the DRBE arises via a pronoun whose referent has no thematic relation to the event at all:

- (51)

- Possessor blocking: I dreamed that I was Trump and I kissed my daughter.

- Possible reading 1: In the dream, Trump kissed Ivanka. (de se kissed de se’s d)

- Possible reading 2: In the dream, Trump kissed my daughter. (de se kissed de re’s d)

- Possible reading 3: In the dream, I kissed my daughter. (de re kissed de re’s d)

- Less plausible reading 4: In the dream, I kissed Ivanka. (de re kissed de se’s d)

We have two theories, then, with their own advantages and disadvantages. One possibility is to assume that both syntactic, in the sense of Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and Anand (2006) and thematic constraints–which I have just presented–are relevant for the DRBE. This would be able to account for all of the instances of blocking that have been discussed thus far. But inverted blocking with possessors might a problem for both theories. Thematic relations are not at play here, for the same reason as possessor blocking above. Furthermore, there is no c-command relationship between the pronouns here:

- (52)

- Inverted blocking with possessors

- I dreamed I was Trump and my daughter fired me.

- Possible reading: In the dream, my daughter fired Trump. (de re’s d fires de se) Less plausible reading: In the dream, Ivanka fired me. (de se’s d fires de re)

In this case, the acceptable reading is the one in which the de re pronoun is embedded in a possessive structure which c-commands the de se pronoun. The less plausible reading is the one in which the de se pronoun is embedded inside a possessive structure that c-commands the de re pronoun. It is not clear what the elusive factor at play here is to lead to this difference. However, it is possible that the difference in acceptability between the two contexts does not involve a de re blocking effect at all. If something like a blocking effect was involved here, it would be difficult to reconcile that with instances of generic blocking such as I fired me. Though one wants to know what the source of this difference in acceptability is, which I must leave to future research.

5 Conclusion

I have presented three novel contexts in which the DRBE may arise, based on experimental evidence:

- (53)

- a.

- Blocking across clauses: I dreamed that I said I was fired.

- but not: I dreamed that I said I ate a Big Mac.

- b.

- Passive blocking: I dreamed that I was fired by me.

- c.

- Inverted possessor blocking: I dreamed that my daughter fired me.

I have claimed that neither of the existing syntactic accounts of blocking presented in Percus & Sauerland (2003b) and Anand (2006) are able to account for these cases. As an alternative, I have explored a thematic account of the DRBE which is able to account for cases of passive blocking and blocking across clauses, but cannot be extended to instances of possessor blocking, which was the original motivation for these syntactic accounts.

At this point, it appears that only assuming both theories together is able to get the full range of facts with the potential exception of (53c) above. The obvious problem with such a mixed account, however, is that it is not parsimonious: it stipulates too much additional machinery, when we would preferably have just one theory for all instances of de re blocking. In addition to being not optimal from a scientific perspective, it might run into issues with learnability. It is not clear, for example, how a child would be able to learn that there are two kinds of de re blocking: both syntactic and lexical.

Thus, a fully satisfactory account of the DRBE currently remains elusive. But ultimately, the goal of this paper has been to open interesting paths for future research, and expand the empirical terrain on an understudied phenomenon in formal semantics.

Notes

- One might object to the asymmetry in (42), and claim that it arises because of the verb fire: as we associate Biden with a position of power and the ability to fire people. I will discuss this point further in section 3, but experimental data indicates that this same asymmetry arises even with predicates like kiss, where it is equally natural to think of Biden kissing the real-life self. The verb fire was used due to its unique lexical semantics, as will be discussed in section 4.2. [^]

- The notion of what it means for a concept generator to be acquaintance-based is not too relevant for us. This notion is based on Lewis (1979); an acquaintance-based relation is one which stands in to one’s experience. For example, the individual that “the girl x saw the photo of in w” is the unique one Caitlin has the acquaintance relation “saw the photo of” in w. In the de re context, this individual ends up being Caitlin. [^]

- Here I am not following Percus & Sauerland (2003a) in assuming that de re readings are based on concepts of type <s, e>. As such, concept generators are of type <e, <s, e>. I instead follow Charlow & Sharvit (2014), Pearson (2015) among others with my treatment of concept generators with centered concepts here. Centered concepts are of type <s, <e, e>>. [^]

- As noted section 1, this is actually not the kind of configuration that Percus & Sauerland discuss. They instead discuss configurations of the form I kissed my daughter, involving a simple possessive structure as the object of the embedded verb. Anand (2006) expands this to constructions like I kissed me, which Arregui (2007) are actually acceptable in dream-contexts. I will use Anand’s configuration more frequently throughout the paper for simplicity. [^]

- This is not as simple as I have described; Anand (2006) claims that there are two dialects of Mandarin, and only one shows the blocking effect. [^]

- The passive has an identical LF to the generic form, so I will use the generic here. [^]

- But given that the THC has been around for decades, it has been discussed and challenged in great detail in the literature: for example, by Safir (2004), Büring (2005) and Varaschin (2020) among others, and few today would take it as a theoretical primitive–though discussing the objections would go beyond the scope of this paper. However, Jackendoff’s observations still need to be accounted for: Varaschin (2020) attempts to reduce Jackendoff’s THC, while accounting for its counterexamples, in terms of a more detailed interpretive factor involving logophoricity. To be more specific, Varaschin notes that contexts which originally motivated the THC have a semantic property, namely that they involve proxy functions applied to a semantic argument. His “Logophoric Strategy” is defined as follows: When a reflexive marker cannot be the argument of a syntactic predicate which is semantically reflexive, the variable to which it corresponds must refer to an entity that bears a logophoric discourse role – i.e. to some kind of perspective bearer. [^]

- For further evidence for this claim, the reader is referred to the review of several studies in Tanenhaus et al. (1989). [^]

Abbreviations

3 Third Person

LOG Logophoric

PERF Perfective

POSS Possessive

REFL Reflexive

SG Singular

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Gennaro Chierchia, Kathryn Davidson and Isabelle Charnavel for helpful comments. The drawings used in this paper are attributed to the following: “big mac” by Boyan from thenounproject.com (CC BY 3.0), “Donald Trump” by Katunger from thenounproject.com (CC BY 3.0), “Ivanka Trump” by Lorie Shaull from thenounproject.com (CC BY 3.0), “person” by Valerie Lamm from thenounproject.com (CC BY 3.0) and “person” by Valerie Lamm from thenounproject.com (CC BY 3.0).

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Adesola, Oluseye. 2006. On the absence of Superiority and Weak Crossover effects in Yoruba. Linguistic Inquiry 37(2). 309–318. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2006.37.2.309

Anand, Pranav. 2006. De de se: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.

Arregui, Ana. 2007. Being me, being you: Pronoun puzzles in modal contexts Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 11. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18148/SUB/2007.V11I0.629

Baker, Mark. 1988. Incorporation. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Baker, Mark. 1997. Thematic roles and syntactic structure. In Haegeman, Liliane (ed.), Elements of grammar, 73–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-5420-8_2

Belletti, Adriana & Rizzi, Luigi. 1988. Psych verbs and theta-theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 6(3). 291–352. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00133902

Bresnan, Joan & Kanerva, Jonni M. 1989. Locative inversion in Chichewa: a case study of factorization in grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 20(1). 1–50.

Büring, Daniel. 2005. Bound to bind. Linguistic Inquiry 36(2). 259–274. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/0024389053710684

Charlow, Simon & Sharvit, Yael. 2014. Rethinking the LFs of attitude reports. Semantics and Pragmatics 7. 1–43. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/sp.7.3

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1990. Anaphora and attitudes de se. In Semantics and contextual expression, 1–32. Dordrecht. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110877335-002

Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In Hale, Ken & Keyser, Jay (eds.), The view from Building 20, 1–52. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Fillmore, Charles. 1968. The case for case. In Bach, Emmon & Harms, Richard (eds.), Universals in linguistic theory, 1–90. New York, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Fox, Danny. 2000. Economy and semantic interpretation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1990. Argument structure. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Hintikka, Jaakko. 1969. Semantics for propositional attitudes. In Davis, J. W. & Hockney & Wilson (eds.), Philosophical logic, 21–45. Reidel. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-9614-0_2

Hovav, Malka & Levin, Beth. 2007. Deconstructing thematic hierarchies. Architectures, rules, and preferences: Variations on themes by Joan W. Bresnan, 385–402.

Huang, C.-T. James & Liu, C.-S. Luther. 2001. Logophoricity, attitudes and ziji at the interface. In Cole, Peter & Hermon, Gabriella & Huang, C.-T. James (eds.), Syntax and semantics: long distance reflexives, 150–195. Academic Press.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1990. On Larson’s treatment of the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 21(3). 427–455.

Lakoff, George. 1972. Linguistics and natural logic, 545–655. D. Reidel. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-2557-7_19

Lewis, David. 1979. Attitudes de dicto and de se. The Philosophical Review 88(4). 513–543. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2184843

Newmeyer, Frederick J. 2002. Grammatical functions, thematic roles, and phrase structure: their underlying disunity. In Davies, William D. & Dubinsky, Stanley (eds.), Objects and other subjects, 53–76. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0991-1_3

Pearson, Hazel. 2015. The interpretation of the logophoric pronoun in Ewe. Natural Language Semantics 23. 77–118. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-015-9112-1

Pearson, Hazel. 2018. Counterfactual de se. Semantics and Pragmatics 11(2). 1. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/sp.11.2

Pearson, Hazel & Dery, Jeruen. 2013. Dreaming de re and de se: Experimental evidence for the ORC. In Proceedings of sinn und bedeutung, vol. 18. 322–340.

Percus, Orin & Sauerland, Uli. 2003a. On the LFs of Attitude Reports. In Weisberger, Matthias (ed.), Proceedings of sinn und bedeutung 7. 228–242. Universitat Konstanz.

Percus, Orin & Sauerland, Uli. 2003b. Pronoun Movement in Dream Reports. In Proceedings of the 33rd North East Linguistic Society. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.

Safir, Ken. 2004. The Syntax of (In)dependence. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6595.001.0001

Schlenker, Philippe. 2005. Non-redundancy: Towards a semantic reinterpretation of Binding Theory. Natural Language Semantics 13(1). 1–92. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-004-2440-1

Tanenhaus, Michael K. & Carlson, Greg & Trueswell, John C. 1989. The role of thematic structures in interpretation and parsing. Language and Cognitive Processes 4(3–4). SI211–SI234. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01690968908406368

Varaschin, Giuseppe. 2020. Anti-reflexivity and logophoricity: an account of unexpected reflexivization contrasts. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 1(5). DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.974