1 Introduction

This paper discusses honorific mismatches between an allocutive/addressee agreement marker and a 2P pronoun within the same clause. Allocutive languages can be divided into two groups based on whether or not they allow mismatches between allocutivity and 2P pronouns. Languages such as Punjabi ban any mismatch between the allocutive marker and the 2P pronoun. An illustration is given in (1). Punjabi uses its plural forms as singular honorific forms. Subsequently, the plural allocutive marker je used for a singular, honorific addressee can co-occur only with the plural 2P pronoun. Using the singular 2P pronoun (meant for a non-honorific addressee) results in ungrammaticality. By contrast, languages such as Japanese allow all combinations of the honorific allocutive marker with 2P pronouns, which may be honorific or non-honorific, as shown in (2).

- (1)

- Maa

- mother.nom

- {twaa/*tai}-nuu

- 2pl.obl/2sg.obl-dom

- bulaa

- call

- rayii

- prg.f.sg

- je.

- alloc.pl

- ‘Mother is calling you.’

- (2)

- {Anata/kisama}-ni-wa

- 2h/2nh-dat-top

- wakar-anai

- understand-neg

- des-yoo-ne.

- cop.alloc.h-prs-sfp

- ‘You do not understand (this).’

In view of this variation in mismatches across Punjabi and Japanese, this paper aims to answer two questions:

- (3)

- a.

- Where in grammar are honorific mismatches between pronouns and allocutive markers ruled out — in the syntactic or in the pragmatic component?

- b.

- How does Japanese permit various combinations of the honorific allocutive marker with honorific/non-honorific 2P pronouns?

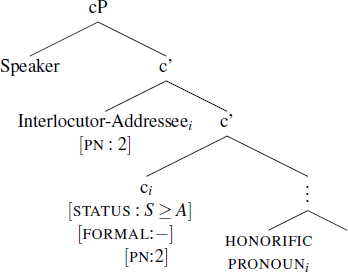

With regard to the first question, there are two existing approaches in the literature. According to the first approach, which we label as the syntactic approach, honorificity is encoded on a functional projection cP in the clause-periphery, via a feature (e.g., [status]). This projection is responsible for licensing honorificity on all 2P items in the clause — via binding on 2P pronouns and via agreement on allocutive markers (Portner et al. 2019; Alok 2021). Since the 2P pronoun and the honorific allocutive marker are syntactically associated with the same c head, no mismatch is tolerated in syntax. The second approach is the semantic-pragmatic approach to honorificity. It requires that the expressive honorific content on the lexical entries of the two items (i.e., the 2P pronoun and the allocutive marker) is comparable in semantics/pragmatics (Potts 2007; McCready 2019). If a speaker uses an item which honors the addressee, and also an item that dishonors the addressee within the same sentence, the combination would be conceptually strange and language would work to block the combination. Subsequently, mismatches are ruled out for pragmatic reasons. Under both approaches, a mismatch in honorificity is predicted to be infelicitous. However, as we show in Section 2, genuine mismatching examples with literal readings are found in Japanese, raising a challenge for both approaches.

Examining honorific mismatches in Japanese, this paper argues that the insights of the two approaches are essentially on the right track. However, the syntactic approach does not generalize to all languages, and the pragmatic approach requires revisions relating to whether or not the meanings of 2P pronouns and allocutivity are comparable across all languages. A crucial premise of the syntactic binding based account is that pronouns are functional (and not lexical) items that can be bound. More specifically, it assumes that honorificity must be a feature of pronouns akin to phi-features such as person and number, and not descriptive content. We claim that this premise of the syntactic approach to mismatches is not universal since the morphosyntax of honorific pronouns varies across languages. Honorificity on Punjabi 2P pronouns is indeed a formal feature like other phi-features. Thus, honorific 2P pronouns in Punjabi are functional items that may be construed as bound variables, forcing matching between 2P pronouns and the allocutive marker in syntax. However, honorificity on Japanese pronouns corresponds to descriptive content, making them lexical items. Following existing literature (Noguchi 1997; Déchaine & Wiltschko 2002, among many others), lexical items cannot be construed as bound variables. Subsequently, the honorific specification on Japanese pronouns is syntactically independent of the honorific content on the allocutive marker. This is the subject matter of Section 3.

Even if honorificity on pronouns and allocutive markers in Japanese is independent of each other in syntax, the following question remains to be answered: why are mismatches not banned by the pragmatic requirement for consistency? As we argue in Section 4, this is because the meanings of Japanese 2P pronouns and honorific allocutivity are not only distinct, as already advocated by McCready (2019), but also incomparable. In particular, while the lexical honorific information encoded in pronouns is the speaker’s positive/negative evaluation of the addressee, the allocutive marker purely encodes the speaker’s intent to be polite, independent of the characteristics of the addressee. It is possible for these two meanings to be expressed simultaneously in select conversational set-ups, leading to felicitous mismatching structures in the language. Section 5 concludes the paper with some open issues.

2 Empirical landscape of honorific (mis)matching

Allocutivity, also known as allocutive or addressee agreement, is a phenomenon where certain languages have distinct verbal morphology that encodes the addressee of the speech act (Oyharçabal 1993; Miyagawa 2012; 2022; Antonov 2015; Kaur 2017; 2020a; 2020b; Alok & Baker 2018; Haddican 2018; Yamada 2019; McFadden 2020; Alok 2021 etc.).1 A classic example comes from Basque in (4), where based on the properties of the addressee (male/female and peer), the verb bears unique morphology -k and -n.

- (4)

- Basque (Oyharçabal 1993)

- a.

- Pette-k

- Peter-erg

- lan

- work

- egin

- do.pfv

- di-k

- 3erg-m

- ‘Peter worked.’ (said to a male friend)

- b.

- Pette-k

- Peter-erg

- lan

- work

- egin

- do.pfv

- di-n

- 3erg-f

- ‘Peter worked.’ (said to a female friend)

All documented allocutive languages allow allocutivity to co-occur with 2P pronouns in the main clause (Antonov 2015). However, the co-occurring 2P pronoun can vary based on: (a) whether it triggers agreement, and (b) whether it can mismatch in features vis-à-vis the allocutive marker. This divides allocutive languages into two groups.

2.1 Group 1: Punjabi

Group 1 consists of allocutive languages which allow only non-agreeing 2P pronouns with allocutivity. Furthermore, no featural-mismatch is allowed between the 2P pronoun and the allocutive marker. Languages like Basque, Tamil, Magahi and Punjabi belong to Group 1. We illustrate with Punjabi.

Punjabi has two 2P pronouns tuu (tai is its oblique form) and tusii (twaa is its oblique form). The form tuu can only be used for a singular non-honorific addressee while tusii can be used either for a plurality of addressees independent of their honorificity, or for a singular honorific addressee. A similar divide is seen in allocutive marking. The form ii/aa is the singular non-honorific form, while je is the plural form used both for a plurality of addressees as well as a singular, honorific addressee.

First, there is an agreement based restriction on the co-occurrence of a 2P pronoun and the allocutive marker in this language: when tusii is in the subject position and bears nominative case, it triggers corresponding agreement on the verbal complex. In such structures, the allocutive marker cannot occur. As shown in (5a), the nominative 2P pronoun tusii must trigger corresponding 2P agreement o. The allocutive marker je cannot occur in such a sentence. Contrast this with the example in (5b), where the 2P pronoun appears in the object position bearing an oblique case. Consequently, it does not trigger agreement — allocutivity is allowed in such a sentence. Note that truth-conditionally, no difference arises due to the use of the 3P person auxiliary e versus the allocutive marker je in (5b).

- (5)

- a.

- Tusii

- 2pl.nom

- maa-nuu

- mother-dom

- bulaa

- call

- raye

- prg.m.pl

- {o/(*je)}

- be.prs.2pl/alloc.pl

- ‘You are calling mother.’

- b.

- Maa

- mother.nom

- twaa-nuu

- 2pl.obl-dom

- bulaa

- call

- rayii

- prg.f.sg

- {e/je}

- be.prg.3sg/alloc.pl

- ‘Mother is calling you.’

Secondly, when the two addressee-oriented expressions (i.e., a 2P pronoun and an allocutive marker) co-occur, they are not allowed to mismatch. The 2P plural/honorific form je can only co-occur with the 2P plural/honorific pronoun twaa-nuu, but not with the 2P singular/non-honorific form tai-nuu, as shown in (6a). Similarly, the non-honorific allocutive marker aa/ii can only occur with the 2P singular/non-honorific form tai-nuu, as shown in (6b).

- (6)

- a.

- Maa

- mother.nom

- {twaa-nuu/*tai-nuu}

- 2pl.obl-dom/2sg.obl-dom

- bulaa

- call

- rayii

- prg.f.sg

- je.

- alloc.pl

- ‘Mother is calling you.’

- b.

- Maa

- mother.nom

- {tai-nuu/*twaa-nuu}

- 2sg.obl-dom/2pl.obl-dom

- bulaa

- call

- rayii

- prg.f.sg

- aa.

- alloc.sg

- ‘Mother is calling you.’

2.2 Group 2: Japanese

In contrast with Group 1, Group 2 allows allocutivity with all 2P arguments, regardless of agreement and (mis)matching features. Languages such as Korean and Japanese belong to Group 2. We illustrate with Japanese.

Japanese has an honorific form of the allocutive marker -mas, which appears on the verb. When the sentence lacks a verb — for example, when it is predicated by an adjective or a noun in a copula construction, des- appears instead of -mas.2 Since there is no phi-agreement in Japanese — i.e., a 2P pronoun in any structural position does not control agreement on the predicate — the allocutive marker can always be licensed regardless of whether the 2P pronoun appears in the subject or in the object position in a clause. This is shown in (7).

- (7)

- a.

- Anata-wa

- 2h-top

- okaasan-o

- mother-acc

- yon-dei-masi-ta.

- call-prg-alloc.h-pst

- ‘You were calling (your) mother.’

- b.

- Okaasan-wa

- mother-top

- anata-o

- 2h-acc

- yon-dei-masi-ta.

- call-prg-alloc.h-pst

- ‘(Your) mother was calling you.’

Moreover, Group 2 allows featural mismatches (in honorificity) between the allocutive marker and 2P pronouns. To show this, we first present the pronominal paradigm in Japanese.3 The language has numerous forms for pronouns of each person specification. Consider the paradigm of pronominal forms in Japanese in Table 1 (see also McCready 2019 for a detailed description of the pronouns). As is evident from the table, while the pronouns vary in the person feature, and in gender for 3P, there are no distinct singular and plural pronominal forms. The language employs associative markers to encode plurality. Second, for each person specification, pronouns vary based on honorific meanings. Table 2 shows an approximated honorific scale for 2P pronouns.

Japanese: pronominal paradigm.

| Person | SG |

| 1 | watakusi, watasi, wasi, atakusi, atasi, assi (archaic), atai, kotti, kotira, wai, wagahai (archaic), ore, ora, oira, boku, uti, mii, sessya (archaic), soregasi (archaic), tin (archaic), … |

| 2 | omae, onusi (archaic), kisama, kimi, anata, anta, anchan, temee, soti (archaic), sotti, sotira, … |

| 3 | kare (m), kanozyo (f), yatu, aitu, … |

Japanese: honorific scale for 2P pronouns.

| non-honorific ←-- | --------- | ------------------- | ---------→ honorific |

| kisama, | omae, | kimi, sotti, | anata, |

| temee | anta | onusi (archaic) | soti (archaic), sotira |

Keeping this in mind, we examine the (mis)matching examples in Japanese. First, consider the sentence in (8a).

- (8)

- a.

- Kare-wa

- he-top

- anata-ni

- 2h-dat

- kore-o

- this-acc

- makase-masi-ta.

- entrust-alloc.h-prs

- ‘He entrusted this to you.’

- b.

- Kare-wa

- he-top

- sotira-ni

- 2h-dat

- kore-o

- this-acc

- makase-masi-ta.

- entrust-alloc.h-prs

- ‘He entrusted this to you.’

As shown in (8a), an honorific 2P pronoun anata can co-occur with the honorific allocutive marker -mas. Not surprisingly, a similar matching example can obtain with sotira, another honorific pronoun, as shown in (8b).

What is interesting is that it is also possible to combine the honorific allocutive marker -mas with pronouns in the mid-honorific range in Table 2 (i.e., kimi, omae, and anta). Consider the examples in (9), where the relevant pronouns are glossed as mh (mid-honorific).

- (9)

- a.

- Kimi-wa

- 2mh-top

- dare-to

- who-with

- siawasena

- happy

- akubi-o

- yawn

- si-mas-u-ka?

- do-alloc.h-q

- ‘With whom do you give a happy yawn?’ (Lyrics by Noriyuki Makihara)

- b.

- [Ore,

- I

- tuutyoo

- passbook

- mite-no

- see-gen

- toori

- as

- okane-no

- money-gen

- kanri

- management

- mattaku

- never

- deki-nai

- can-neg

- kara]

- since

- omae-ni

- 2mh-dat

- makase-mas-u.

- trust-alloc.h-prs

- ‘Since, as you can see from my passbook, I cannot ever manage my money, I will leave it up to you.’ (https://trip-partner.jp/8204)

- c.

- Hirot-ta

- pick-pst

- yatu-o

- thing-acc

- anta-ni

- 2mh-dat

- osie-masi-ta-yo.

- teach-alloc.h-sfp

- ‘I showed you the thing I had found.’4

Most interestingly, honorific allocutivity can also occur with kisama and temee, which are on the far non-honorific end of the scale in Table 2, as shown in (10). We gloss kisama and temee as nh (non-honorific).

- (10)

- a.

- Kisama-ni-wa

- 2nh-dat-top

- wakar-anai

- understand-neg

- des-yoo-ne.

- cop.alloc.h-epi-sfp

- ‘You do not understand (this).’

- b.

- Temee-ni-wa

- 2nh-with-top

- kankee

- relation

- nai

- absent

- des-u-yone?

- cop.alloc.h-prs-sfp

- ‘This has nothing to do with you, right?’

In this way, the honorific allocutive marker -mas/des- can not only occur with pronouns on the honorific end of the scale but also with pronouns on the mid and low honorific ends. Note that these mismatching examples in (10) are instances of genuine mismatches in honorificity, since they also have literal (and not only sarcastic) readings, as we will elaborate upon in Section 4.

To summarise the cross-linguistic landscape, in languages such as Punjabi, mismatches are completely ungrammatical. An honorific allocutive marker can only occur with an honorific 2P pronoun. By contrast, in languages such as Japanese, the honorific allocutive marker can co-occur with 2P pronouns of distinct honorific levels. This leads us to the following question: what allows varying (non-)honorific combinations of the allocutive marker and pronouns in Japanese but not in Punjabi?

3 Syntactic approach to honorificity: arguments against its universality

In the spirit of the Performative Hypothesis, which situates information about the speech act and its participants (speaker, addressee) in the clause-periphery (Speas & Tenny 2003; Hill 2007; Miyagawa 2012; 2017, a.o.), Portner et al. (2019) locate honorificity on a functional head in the left-periphery of the clause.

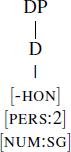

- (11)

As shown in the representation in (11), the clause-periphery hosts a projection cP. The head of cP has a valued [status] feature, among other honorificity-related features. Following Baker (2008) and Kratzer (2009), 2P pronouns are analyzed as bound elements, which enter syntax without any pre-valued features. These features are acquired in syntax through operator-variable agreement with the Interlocutor argument. When a pronoun is syntactically bound by Interlocutor, mediated by c as a λ-abstractor, it refers to the interlocutor-addressee and reflects the feature values of c. Allocutive markers can be treated as the morphological realization of c, or as a clitic/agreement marker that is associated with the Interlocutor argument merged in the specifier of c. Since both the allocutive marker and 2P pronouns are syntactically dependent on the same Interlocutor/c for honorificity licensing, there is no room for featural mismatching under this approach.

A crucial premise of the above binding based account is that pronouns are functional (and not lexical) items that can be bound. More specifically, it assumes that honorificity must be a feature of pronouns akin to phi-features such as person and number, and not descriptive content. However, as we demonstrate in the rest of this section, this assumption is not correct. The morphosyntax of honorific pronouns varies across languages. While honorificity on Punjabi 2P pronouns is indeed a formal feature, it corresponds to descriptive content on Japanese pronouns. Thus, honorific 2P pronouns in Punjabi are functional items that may be construed as bound variables, but honorific pronouns in Japanese must be treated as lexical items. The syntactic explanation to banning mismatches between 2P pronouns and allocutive markers is therefore not universal — it can only apply to systems such as Punjabi but not to Japanese.

3.1 Punjabi pronouns

We start with Punjabi. Unlike the Japanese pronominal paradigm in Table 1, Punjabi pronouns form a closed class with significantly fewer honorific forms. First, honorific forms are available only for 2P and 3P. There are no 1P honorifics. Secondly, there are only two levels of honorificity in Punjabi (i.e., honorific and non-honorific). This is shown in Table 3, where H stands for honorific and NH for non-honorific.

Punjabi: pronominal paradigm.

| Person | singular | plural |

| 1 | maiN | asii |

| 2 | tuu (NH) | tusii (H) |

| 3 | o (NH) | o (H) |

As is also evident from the table, Punjabi re-uses its phi-forms as honorific forms, as is well-known for many Indo-European languages like French, German, Spanish among others. Thus, in addition to its use as a plural 2P pronoun which is insensitive to the (non-)honorificity of the addressee, the form tusii is also used to refer to a singular honorific addressee. In contrast, the singular form tuu can only refer to a singular non-honorific addressee. Similar facts hold for the 3P plural pronoun in the language o which is used to refer to a group of people as well as to refer to a singular honorific third person. The singular 3P pronoun is only used for a non-honorific third person referent.5

Akin to the pronominal paradigm, the agreement paradigm in Punjabi also re-uses the phi-agreement forms. Plural pronominal forms, when used for a plural referent, trigger corresponding plural agreement. This is shown for a 2P plural honorific referent in (12a). Notably, the plural pronoun triggers plural agreement on both the verb and the predicative adjective also when used for a singular honorific addressee. This is demonstrated in (12b).

- (12)

- a.

- [Context: A student is appreciating her teachers. She says:]

- Tusii

- 2pl.nom

- (saare)

- all

- syaane

- smart.m.pl

- o.

- be.prs.2pl

- ‘You (all) are smart.’

- b.

- [Context: A granddaughter is appreciating her grandfather. She says:]

- Tusii

- 2pl.nom

- (*saare)

- (*all)

- syaane

- smart.m.pl

- o.

- be.prs.2pl

- ‘You (*all) are smart.’

Contrast with singular agreement, which obtains only with the singular form tuu.

- (13)

- Tuu

- 2sg.nom

- syaanaa

- smart.m.sg

- ẽ.

- be.prs.2sg

- ‘You are smart.’

The same pattern is maintained with the 3P plural form, which always triggers 3P plural agreement, even when used to refer to a singular honorific 3P, as shown in (14a). Singular agreement obtains only with the singular 3P pronoun, as in (14b).

- (14)

- a.

- O

- 3pl.nom

- syaane

- smart.m.pl

- ne.

- be.prs.3pl

- ‘They are smart.’ OR ‘(S)he (honorific) is smart.’

- b.

- O

- 3sg.nom

- syaanaa

- smart.m.sg

- e.

- be.prs.3sg

- ‘He is smart.’

In summary, Punjabi only has a two-way distinction in honorificity available only for 2P and 3P. This is easily analyzable by positing positive and negative values of a feature such as [HON]. However, since there is no unique morphology separating the honorific feature from phi-features either in the pronominal or in the agreement make-up, it is worth asking if honorificity even constitutes a distinct feature in Punjabi or if it is purely a matter of interpretation that the plural forms can be interpreted as honorific. We argue that [HON] is a distinct formal feature in the language, where ‘formal’ is defined as follows:

- (15)

- A feature is formal if it is involved “[…] in inflectional paradigms, or trigger syntactic movement or agreement, or play some other demonstrably formal role” (Cowper & Hall 2014: 146; see also Zeijlstra 2008).

Evidence for a formal encoding of honorificity in Punjabi comes from syncretism in agreement in the feminine paradigm. In Punjabi, the copula only shows person and number inflection. The verbal form inflected for aspect shows gender and number inflection. We show the perfective verbal forms for the verb ‘go’ in Table 4. Crucially, note that the table consists of an extra row to present the honorific, singular agreement forms.

Punjabi: perfective verb forms for ‘go.’

| Number/gender | masculine | feminine |

| singular | gayaa | gayii |

| plural | gaye | gayiyaaN |

| honorific singular | gaye | gaye |

As shown in Table 4, the masculine plural form gaye obtains not only for agreement with a plural subject but also for an honorific singular subject. With a feminine nominal, however, the forms differ across the feminine plural and the honorific singular usage. This is illustrated in the following examples.

- (16)

- a.

- Tuu

- 2sg.nom

- bajaar

- market

- gayii

- go.pfv.f.sg

- sa͠i.

- be.pst.2sg

- ‘You went to the market.’ Singular non-honorific

- b.

- Tusii

- 2pl.nom

- bajaar

- market

- gayiyãã

- go.pfv.f.pl

- so.

- be.pst.2pl

- ‘You all went to the market.’ Plural

- c.

- Massii-jii,

- aunt-h

- tusii

- 2pl.nom

- bajaar

- market

- {gaye/*gayiyãã}

- go.pfv.m.pl/go.pfv.f.pl

- so.

- be.pst.2pl

- ‘Aunt, you went to the market.’ Singular honorific

As expected, a singular non-honorific feminine subject triggers singular agreement as in (16a), and its plural counterpart, regardless of honorificity, triggers plural agreement, as in (16b). With a singular honorific feminine subject, we expect the feminine plural form gayiyãã. However, the agreement form that obtains is syncretic with the masculine plural form, as shown in (16c).

The same pattern is observed across differing aspectual forms of the verb, as well as with predicative adjective. We argue that an analysis of the above-mentioned syncretism between feminine singular honorific and masculine plural agreement necessitates an honorificity based feature in morpho-syntax. To see this, consider an account where morpho-syntax lacks an honorific feature. In such a scenario, the masculine paradigm can be derived in a straightforward way. Regardless of its (non-)honorific interpretation, a nominal specified as masculine plural in syntax triggers plural agreement. This generates the same agreement form across-the-board, regardless of whether it is interpreted as masculine plural honorific, masculine plural non-honorific or masculine singular honorific. In contrast, a noun specified as masculine singular in syntax triggers singular agreement.

- (17)

- a.

- [m.sg] ↔ /gayaa/

- b.

- [m.pl] ↔ /gaye/

However, the same analysis cannot explain the feminine paradigm. Consider (18), where a noun specified as feminine singular in syntax triggers singular agreement, which is correct. However, for a feminine noun specified as plural in syntax, the account only generates gayiyãã, which is incorrect.

- (18)

- a.

- [f.sg] ↔ /gayii/

- b.

- [f.pl] ↔ /gayiyãã/

We propose an alternative solution which employs a (non-)honorific feature in syntax. Two revisions are proposed: first, feminine is the marked gender feature with masculine being unmarked. Secondly, in addition to their phi-specifications, the nominal and agreement forms also bear honorific specifications via a [HON] feature. In Punjabi, it can have two possible values: + or –, where the former indicates that the addressee is honorific to the speaker, while the latter shows that he/she is not. Given these two modifications, consider the following rules of Vocabulary Insertion/VI for masculine agreement forms.

- (19)

- a.

- [sg, -HON] ↔ /gayaa/

- b.

- [pl, +HON] ↔ /gaye/

- c.

- [pl, –HON] ↔ /gaye/

- d.

- [sg, +HON] ↔ /gaye/

For the feminine agreement forms, the following VI rules apply.

- (20)

- a.

- [f, sg, –HON] ↔ /gayii/

- b.

- [f, pl, –HON] ↔ /gayiyãã/

For the [f, sg, +HON] bundle, we propose that the marked feminine feature is deleted in the presence of the [sg, +HON] bundle. This is shown via the impoverishment rule in (21). The only lexical item that can be inserted to realise the subsequent feature bundle is gaye.

- (21)

- *[FEM] on the same complex node as [sg, +HON]

- (22)

- [sg, +HON] ↔ /gaye/

Thus, unless we assume that Punjabi has a distinct formal [HON] feature visible in morpho-syntax, the syncretism between feminine singular honorific agreement and masculine plural/honorific agreement cannot be explained. This feature can be positively or negatively specified, yielding a two-way honorificity distinction.

3.2 Japanese pronouns

In contrast with Punjabi, pronouns constitute an open class in Japanese — there are numerous 2P forms that vary for honorificity, as we saw earlier in Section 2.2. In this section, we show that honorificity on pronouns in Japanese corresponds to descriptive content, in sharp contrast with the Punjabi system.

Recall from Table 1 in Section 2.1.2 that pronouns in Japanese vary in the person feature, and in the gender feature for 3P. This is not unlike the better-studied Germanic and Romance linguistic systems. However, Japanese pronouns stand out with regard to the range of (non-)honorific forms they have for each person specification. For instance, in the 2nd person, the language has, at least, ten forms, which vary for honorificity. Given this large number of pronouns, we examine if honorificity in Japanese is encoded via a formal feature, making the pronoun a functional item, or if honorificity is descriptive content, making the pronoun a lexical item on a par with nouns like ‘cat’, ‘dog’ etc.

To this end, we first try to identify one (or more) suitable honorificity-related feature(s). Distinct values of the honorific features should differentiate all forms of 2P pronouns. If this is not tenable, it would indicate that Japanese pronouns are lexical items — they consist of the person feature, and honorificity as descriptive content. As is evident, a feature like [HON] employed for honorific systems like Punjabi cannot be extended directly to Japanese. This is because [HON] is limited to two values (i.e., positive/negative), which yields only two distinct pronouns. Therefore, we adopt the [status] feature from Kim-Renaud & Pak (2006). Proposed initially for Korean, the [status] feature encodes a hierarchical relation between the speaker and addressee and can have five different values (less than, less than or equal to, equal to, greater than or equal to, greater than). Ignoring the archaic forms and focusing on the following eight pronouns in Japanese for now (omae, kisama, kimi, anata, anta, sotti, temee, and sotira), we observe that the values of the [status] feature would yield 5 distinct spellout forms, which do not suffice to explain the availability of 8 distinct 2P singular forms. Furthermore, 2P pronouns in Japanese do not vary for the values of the [status] feature. As shown in Table 5, six of the eight pronominal forms end up having the same specification for [status] in that they can be used by a speaker who is in a superior position to the addressee. With sotti, the speaker can also be equal to the addressee in status, and with sotira, (s)he may be inferior.

Japanese: [status] in pronouns.

| Pronoun | person | status |

| kisama | 2 | Sp>Adr |

| temee | 2 | Sp>Adr |

| omae | 2 | Sp>Adr |

| anta | 2 | Sp>Adr |

| kimi | 2 | Sp>Adr |

| sotti | 2 | Sp>/=Adr |

| sotira | 2 | Sp>/<Adr |

| anata | 2 | Sp>Adr |

Thus, [status] alone does not suffice to demarcate the 2P forms from each other. Let us entertain the possibility of an additional feature [politeness], which, regardless of the [status] of the speaker, encodes his/her intent to be polite to the addressee. It has two possible values: [Politeness: +/–], where + encodes the intent of the speaker to show respect and – indicates the lack of this intent. Various combinations of [status] and [politeness] would yield 10 distinct possibilities of spell-out, which should be enough to accommodate 8 pronouns. However, even this does not suffice to demarcate the pronouns, as shown in Table 6, where the top five forms end up with identical features.

Japanese: [status] and [politeness] in pronouns.

| Pronoun | person | status | politeness |

| kisama | 2 | Sp>Adr | – |

| temee | 2 | Sp>Adr | – |

| omae | 2 | Sp>Adr | – |

| anta | 2 | Sp>Adr | – |

| kimi | 2 | Sp>Adr | – |

| sotti | 2 | Sp>/=Adr | +/– |

| sotira | 2 | Sp>/<Adr | + |

| anata | 2 | Sp>Adr | + |

We can keep trying this experiment with more honorificity-related features. However, it is worth noting that the meanings that can disambiguate 2P pronouns valued identically for [status] and [politeness] do not seem translatable into a non-descriptive feature at all. To illustrate, consider omae and anta — both forms are sensitive to status and are typically uttered when Sp > Adr, and do not encode the Sp’s intent to be polite. The distinction between these two forms is loosely related to the speaker’s gender: anta seems to be used more often by a female speaker, and omae by a male. This gender based distinction, however, is not borne out in all instances. Moreover, note that this gender distinction corresponds to the gender of the speaker, and not the individual picked by the 2P feature (i.e., the addressee). Hence, positing a gender feature in these two pronouns cannot be correct. Similarly, take kisama, which differs from temee with regard to the degree of offensiveness it brings and the specificity of the situation it can be used in (it is typically used in quarrels). Another meaning which demarcates some pronouns from others is the self-image that the speaker is trying to portray. For instance, by using kimi, the speaker attempts to project a noble/sophisticated image of him/herself, which is distinct from the use of anta, which emphasises the speaker’s humble background. Such meanings are clearly concept-denoting. Based on this discussion, we claim that honorificity in Japanese pronouns is not encoded via a formal feature, but is instead descriptive in nature. Japanese pronouns, subsequently are lexical items. All 2P pronouns bear the same formal feature (i.e., 2P) — this should only yield one 2P pronominal form. However, given the descriptive nature of honorificity (a label used to denote a range of complex meanings) also hosted on the 2P pronouns, the language allows for a large class of 2P pronouns, which are distinguished from each other via their varying honorificity related meanings.

Prima facie, this finding seems incompatible with the syntactic nature of object honorification/OH, which bears all characteristics of Agree. We make a small digression in the following subsection to show that the descriptive nature of honorificity on pronouns can be reconciled with OH.

3.2.1 Reconciliation with object-honorification

Japanese has an OH construction, which is used when the object refers to a person who is respected by the speaker (Niinuma 2003; Yamada 2019; Ikawa 2021; Ikawa & Yamada to appear). The sentence in (23a) is the plain, baseline example. In the presence of a non-honorific object, the verb does not host any OH morphology. In contrast, in the presence of an honorific object in (23b), the verb bears distinct morphology to encode the speaker’s respect towards the referent of the direct object.

- (23)

- Object-honorific construction

- a.

- John-ga

- John-nom

- Akira-o

- Akira-acc

- sagasi-masi-ta.

- look for-alloc.h-pst

- ‘John looked for Akira (non-honorific).’

- b.

- John-ga

- John-nom

- sensei-o

- teacher-acc

- osagasisi-masi-ta.

- look for.oh-alloc.h-pst

- ‘John looked for the teacher (honorific).’

As shown by Ikawa (2021), the availability of OH also requires that not only the speaker but also the subject of the clause honor the individual denoted by the object. Thus, if the subject of the clause is superior to the object, OH cannot be used. For instance, in (23b), if John is the college principle who is superior to the object (i.e., teacher), OH would be infelicitous.6

In the presence of a speaker and a subject that honor the referent denoted by the object, there are several structural requirements that must be met for OH to obtain (Boeckx & Niinuma 2004; Hasegawa 2017; Yamada 2019; Ikawa 2021; Ikawa 2022 a.o.). First, if the object pronoun is an adjunct and not an object argument of the verb, OH cannot take place even if the speaker and the subject honor the referent of the object. To elaborate, in Japanese, the to-marked phrase can either be a complement or an adjunct. Consider the sentences below.

- (24)

- Complement-adjunct distinction

- a.

- Taroo-wa

- Taroo-top

- anata-to

- 2h-with

- oaisi-ta.

- meet.oh-pst

- ‘Taroo met you.’

- b.

- Taroo-wa

- Taroo-top

- anata-to

- 2h-with

- Hanako-o

- Hanako-acc

- {#otasukesi/tasuke}-ta.

- help.oh/help-pst

- ‘Taroo helped Hanako with you.’7

In (24a), the verb oaisi ‘meet’ selects a to-marked complement. In contrast, in (24b), the verb tasuke ‘help’ selects an o-marked accusative object. The to-marked phrase in this sentence is an adjunct — it describes the person with whom Taroo participated in the helping event. It is possible to use OH for the direct object in (24a) since it is the complement. By contrast, if the direct object Hanako is non-honorific, OH is not possible in (24b) even if the speaker and subject respect the individual denoted by the 2P pronoun in the adjunct position.8

The second structural factor that OH is sensitive to pertains to the phase condition. OH in the matrix verb cannot associate with an honorific object argument in the embedded clause, as shown in the following example from Ikawa (2021).

- (25)

- Phase condition

- Taroo-wa

- Taroo-top

- [anata-ga

- 2h-nom

- o-kirei

- h-beautiful

- da-to]

- cop-that

- {*oomoisi/omot}-ta.

- think.oh/think-pst

- ‘Taroo thought (OH) [you were beautiful].’

Finally, object honorifics (OH) in Japanese are sensitive to intervention effects in ditransitives (Niinuma 2003; Boeckx & Niinuma 2004; Ikawa 2022; Ikawa & Yamada to appear, among others). Specifically, in the presence of an indirect object (IO), which is non-human, the OH can be associated with the honorific direct object (DO), as in (26a). However, in the presence of a human IO, the relation between the OH and the DO fails to be established, as in (26b).

- (26)

- a.

- Hanako-ga

- Hanako-nom

- gakkaikaizyoo-ni

- conference room-dat

- anata-o

- 2h-acc

- oturesi-ta.

- take.oh-pst

- ‘Hanako took (OH) you to the conference room.’

- b.

- #Hanako-ga

- Hanako-nom

- doroboo-ni

- thief-dat

- anata-o

- 2h-acc

- gosyookaisi-ta.

- introduce.oh-pst

- ‘Hanako introduced (OH) you to the thief.’

We should note that the presence of an honorific argument in the IO position, with the DO being non-honorific can also generate OH. For instance, if anata were in the IO position with ‘thief’ being the DO, OH would be allowed, as is shown in (27).9

- (27)

- Hanako-ga

- Hanako-nom

- anata-ni

- 2h-dat

- doroboo-o

- thief-acc

- gosyookaisi-ta.

- introduce.oh-pst

- ‘Hanako introduced (OH) the thief to you.’

Given that the target of honorification is sensitive to several syntactic factors, it is reasonable to conclude that OH involves Agree (Niinuma 2003; Boeckx & Niinuma 2004). A purely pragmatic approach cannot explain OH. This finding seems incompatible with our proposal that honorificity on Japanese pronouns is descriptive. Indeed, earlier syntactic accounts of OH have assumed a formal [HON] feature on the object which undergoes agreement with v (Niinuma 2003; Boeckx & Niinuma 2004). However, recent work by Ikawa (2022) clearly demonstrates that, although syntactic, OH in Japanese does not underlie agreement between the probe and the object in a [HON] feature. Instead OH is the result of agreement in an index feature.

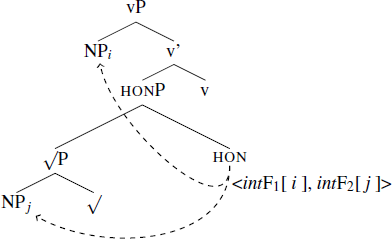

To elaborate, following Ikawa & Yamada (to appear), Ikawa (2022) proposes that the functional head that participates in OH is HON0 situated below v. HON0 contains two interpretable but unvalued index features, labeled as intF1[ ] and intF2[ ]. All animate nouns and pronouns bear an index (i,j,k and so on) that can value the index feature on HON0. Note that use of the index feature as participating in agreement is not new; for differing versions of this feature, see Hicks (2009), Kratzer (2009), a.o.. Assuming bidirectional Agree (e.g., Baker 2008), the feature intF1[ ] probes downward to be valued by the index feature of the closest animate object while intF2[ ] probes upward to be valued by the index feature on the subject within the same phase. This values HON0 with the indices that the object and the subject bear respectively.

- (28)

The feature on HON0 are interpretable, which allows them to survive the syntactic derivation. They are parts of the semantic representation of HON0, as shown below.

- (29)

In summary, honorificity on Japanese pronouns is descriptive content, which is inactive in syntax. This finding is not at odds with the syntactic nature of OH if OH is treated as agreement in the index feature, in line with Ikawa (2022).

3.3 Functional versus lexical pronouns: consequences for binding

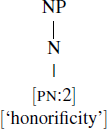

So far, we have seen that honorificity in Punjabi pronouns is a formal feature on par with phi-features, while it is descriptive content in Japanese pronouns. Given the composition of Punjabi pronouns, which contain only formal features (person, number and honorificity), we propose that they are functional items. More specifically, we follow the analysis of Abney (1987) to propose that pronouns in Punjabi are intransitive determiners. There is no N head since the pronoun lacks descriptive content. We provide a structure for the non-honorific singular 2P pronoun tuu in (30). The DP lacks an NP, with the D head hosting all relevant features.

- (30)

- Punjabi

In contrast with Punjabi, honorificity on 2P pronouns in Japanese is treated as descriptive content. We follow Noguchi’s (1997) N-pronoun analysis of Japanese 3P pronouns to claim that Japanese pronouns are NPs. The descriptive content of 2P pronouns i.e., honorificity, is situated on N. Furthermore, following Rouveret (1991), we also situate the person feature on N. The structure is shown in (31).10

- (31)

- Japanese

The N-pronoun analysis for 2P pronouns in Japanese predicts nominal-like behavior of 2P pronouns in Japanese, which is borne out. First, some Japanese 2P pronouns clearly show an etymological relation with common nouns. For example, temee is etymologically a N-N compound, decomposable into te ‘hand’ and mae ‘front,’ and originally means ‘front of (my) hand’ (i.e., ‘a person in front of me/your (my/your hand)’). It is natural to assume that these distinct morphemes in honorific pronouns gradually became unanalyzable to an extent that they are now seen as a single word (Vovin 2003: 95; Frellesvig 2010: 245–246). Secondly, it is well-known that 3P pronouns in Japanese, like nouns, can be modified by a demonstrative, an adjective and a relative clause (Kuroda 1965: 105; Noguchi 1997: 777). We show that just like 3P pronouns, 1P and 2P pronouns can also be modified in the language. The 2P pronoun anata can be modified by a demonstrative and an adjective, as in (32a), and by a demonstrative and a relative-clause like structure, as in (32b).

- (32)

- a.

- ano

- that

- kasikoi

- smart

- anata

- you

- ‘that smart you’

- b.

- ano

- that

- [atama-ga

- head-nom

- ii]

- good

- anata

- you

- ‘that you who is smart’

Thus, based on the formal v/s descriptive nature of honorificity on pronouns, 2P pronouns in Punjabi are DPs but those in Japanese are NPs. If our D versus N-pronoun analysis of Punjabi and Japanese pronouns is on the right track, we expect to see differences in their binding patterns. The functional (D/phi) versus lexical status of 3P pronouns has been tied to their binding ability in the literature (Noguchi 1997; Déchaine & Wiltschko 2002; Koak 2008, among others). For instance, pronouns in English are functional which allows them to be construed as a bound variable, as is shown in (33). Similar observation has been made for Shuswap pronouns, analysed as functional items (Déchaine & Wiltschko 2002), as in (34). In contrast, pronouns which are lexical in nature cannot be construed as bound variables. This is well-known for the Japanese 3P pronoun kare, as in (35) (Saito & Hoji 1983; Hoji 1991; Noguchi 1997 etc.).

- (33)

- Everyonei likes hisi father.

- (34)

- Shuswap

- [Xwexwéyt]i

- all

- re

- det

- swet

- who

- xwis-t-0-és

- like-trans-3sg.obj-3sg.subj

- [newt7-s]i

- emph-3

- re

- det

- qe7tse-si.

- father-3.poss

- ‘Everyonei likes hisi father.’ (Lai 1998, as cited in Déchaine & Wiltschko 2002)

- (35)

- *Daremoi-ga

- everyone-nom

- karei-no

- he-gen

- hahaoya-o

- mother-acc

- aisite-iru.

- love-prs

- ‘Everyonei loves hisi mother.’ (Noguchi 1997: 770)

Since the 2P pronoun in Japanese is lexical, it should not be possible to construe these pronouns as bound variables. For Punjabi, the prediction is not so clear since being a functional item is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for an item to be construed as a variable. To see what a bound variable reading of 1P/2P pronouns looks like, consider the following illustration from English in (36) (Rullman 2004; Kratzer 2009, among others).

- (36)

- Only you did your homework.

- Referential paraphrase: Nobody else did your homework.

- Bound variable paraphrase: Nobody else did their homework.

We observe that Japanese 2P pronouns cannot obtain a bound variable reading. As shown in (37), the possessive 2P pronoun can only receive a referential interpretation. To obtain a bound reading, the reflexive zibun must be employed instead. Bound construals of 2P pronouns are also unavailable in relative clauses, (38).

- (37)

- a.

- Anata-dake-ga

- 2h-only-nom

- anata-no

- 2h-gen

- heya-ni

- room-in

- i-ru.

- be-prs

- ‘Only you stay in your room.’ (√ referential; *bound)

- b.

- Anata-dake-ga

- 2h-only-nom

- zibun-no

- self-gen

- heya-ni

- room-in

- i-ru.

- be-pst

- ‘Only you stay in your room.’ (√ bound)

- (38)

- Anata-ga

- 2h-nom

- [anata-no

- 2h-gen

- heya-ni

- room-in

- i-ru]

- be-prs

- yuitu-no

- only-gen

- ningen

- man

- da.

- cop

- ‘You are the only person who is in your room.’ (√referential, *bound)

In Punjabi, sentences such as ‘only you did your homework’ with a 2P possessive pronoun do not allow a bound reading; a reflexive is needed instead.

- (39)

- a.

- ?Sirf

- only

- tuu

- 2sg.nom

- teraa

- 2sg.poss

- kamm

- work

- kittaa

- do.pfv.m.sg

- e.

- be.prs

- ‘Only you have done your work.’ (√ referential; *bound)

- b.

- Sirf

- only

- tuu

- 2sg.nom

- apnaa

- self

- kamm

- work

- kittaa

- do.pfv.m.sg

- e.

- be.prs

- ‘Only you have done your work.’ (√ bound)

However, there are certain instances, where the bound construal of a 1P/2P pronoun is available. Consider the following example with a 1P plural pronoun, based on Rullman (2004). 11

- (40)

- Saanuu

- 1pl.dat

- lagdaa

- feel.m.pl

- e

- be.prs

- ki

- that

- asii

- 1pl.nom

- syaane

- smart

- ãã.

- be.prs.1pl

- Referential reading: ‘Each of us feels that we (speaker and his/her associates) are smart.’

- Bound variable reading: ‘Each of us feels that he/she is smart.’

To summarise, 2P pronouns in Punjabi are functional items that may participate in syntactic binding. This makes the syntactic approach a live possibility to explain the ban on honorific mismatches in the language.12

However, the syntactic approach to banning mismatching honorificity (Portner et al. 2019), which requires pronouns to be bound by c, cannot be extended to Japanese. Japanese 2P pronouns are lexical items that cannot be construed as bound variables. Since Japanese pronouns cannot be bound by a syntactic c-like head, the honorific specification of pronouns is syntactically independent of that on the allocutive marker. This, in principle, makes room for honorific mismatches between 2P pronouns and allocutivity in Japanese.

4 Towards a pragmatic approach to mismatches in Japanese

If the difference in honorific mismatching were purely due to syntax, the contrast between Punjabi and Japanese would be easy to explain: in Punjabi, pronouns need to be syntactically bound by c, which also licenses allocutivity, making matching obligatory. In contrast, in Japanese, there is no syntactic binding of pronouns, allowing 2P pronouns to mismatch with honorific allocutivity.

However, this is not such a simple matter: it remains unexplained why the two distinct honorific meanings from a non-honorific 2P pronoun and an honorific allocutive marker in Japanese do not conflict in pragmatics. To see this problem better, consider the sentence in (41).

- (41)

- #I am 2 inches taller than my father, and I am also 2 inches shorter than my father.

This sentence is grammatical, but is infelicitous, because each clause delivers contradicting information. As an analogy, even if the mismatch in Japanese is syntactically allowed, we would predict that the mismatching sentence containing a non-honorific 2P pronoun and an honorific allocutive marker is filtered out post-syntactically. Nevertheless, a mismatch is allowed in Japanese. Why is this language so flexible?

4.1 Previous approaches to Japanese honorificity

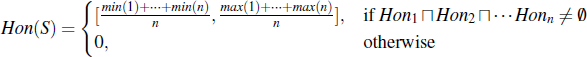

In the formal semantics literature on honorificity, researchers have proposed a consistency rule to explain matching among honorific items in a clause (Potts & Kawahara 2004; Potts 2007; McCready 2014; 2019). For illustration, we consider McCready (2014), who proposes that (i) each honorific expression is assigned a particular honorific range (e.g., Hon1), and (ii) the honorific level of the entire sentence is calculated as an average of all expressions used in the sentence, unless the intervals have empty interactions (ibid., 508), as shown below.13

- (42)

Under this view, “high and low-level items cannot be used together, though combinations of high and mid-level items are possible, as are combinations of mid- and low-level items (ibid., 508).”

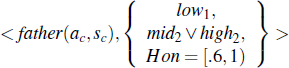

McCready (2019: Ch.7), however, proposes a sightly different view from the above analysis. While maintaining the conditional rule in (42) as a general principle for honorific expressions (McCready 2019: 32), she explicitly analyzes Japanese pronouns as not encoding intervals but something different, distinguishing them from those found in other honorific languages (e.g., Thai). She motivates this treatment based on the observation that 1P pronouns of a low politeness register and 2P pronouns of a high politeness register can coexist within the same sentence in Japanese but not in Thai (McCready 2019: 110). If we consider that both pronouns merely denote an interval in Japanese, we wrongly predict that there is no overlap in politeness register and conclude that such sentences are unacceptable. Thus, rather than directly specifying the register, she hypothesizes that pronouns “carry information relevant to register assignment” — more specifically, the speaker expectations and commitments relating to the social behavior of the conversational participants — and let the register specification be done via pragmatic inference.

To see the implementation of her system for Japanese, consider the following example:

- (43)

- Anata-wa

- 2h-top

- ore-no

- 1-gen

- titioya

- father

- des-u.

- cop.alloc.h-prs

- ‘You are my father.’

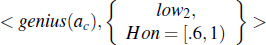

For the at-issue meaning, we obtain the proposition that the addressee is the father of the speaker (father(ac, sc)). For the expressive dimension, we have three pieces of information; (i) the 2P pronoun anata indicates that the speaker makes public an expectation that they will behave formally or somewhat formally toward the addressee (mid2 ∨ high2); (ii) the 1P pronoun ore indicates that the speaker makes public that they do not expect formal behavior from the addressee toward them (low1); and (iii) the allocutive marker denotes an politeness interval for a high register (e.g., 0.6 to 1.0). Thus, we have the set of meanings as shown below.

- (44)

In the above example, low1 and mid2 ∨ high2 are semantic objects of the same type, and they differ from the semantic type (Hon = [.6, 1)). Since the meanings low1 and register (Hon = [.6, 1)) are different semantic objects, there is no conflict in meaning. Despite being of the same type, low1 and mid2 ∨ high2 are also compatible, because the former is the expectation about the addressee’s behavior toward the speaker, and the latter is about the speaker’s behavior toward the addressee. Under such an analysis where mismatching expressive meanings of two semantic objects that are of distinct types (1P pronoun and allocutive marker above) does not cause conflict, one may predict that mismatching instances between 2P pronouns and allocutive markers are also accepted. But McCready (2019) observes that a sentence as in (45a) is infelicitous: it lacks a literal reading, and can only be interpreted sarcastically. To explain this, she proposes that the low2 and Hon = [.6, 1) are in fact comparable, and have no overlapping range in intervals (McCready 2019: 120).14

- (45)

- a.

- #Temee-wa

- 2nh-top

- tensai

- genius

- des-u.

- cop.alloc.h-prs

- ‘You are a genius (intended).’

- b.

She explains: “the fact of a high register implies that the speaker should behave formally, given ordinary social obligations […]; this is not compatible with the content of [temee], which indicates an absolute lack of commitment to formal behavior by the speaker and in addition insults the addressee […] (ibid. 120–122).”

If this is the case, why are the mismatching examples in (10) (repeated below in (46)) felicitous? This comparison is the subject matter of the next subsection.

- (46)

- a.

- Kisama-ni-wa

- 2nh-dat-top

- wakar-anai

- understand-neg

- des-yoo-ne.

- cop.alloc.h-will-sfp

- ‘You do not understand (this).’

- b.

- Temee-ni-wa

- 2nh-with-top

- kankee

- relation

- nai

- absent

- des-u-yone?

- cop.alloc.h-prs-sfp

- ‘This has nothing to do with you, right?’

4.2 Literal readings in mismatching sentences

In McCready’s work, the mismatch between a 2P pronoun and the allocutive marker is at the heart of a non-literal/sarcastic reading. Although the sarcastic interpretation is not detailed upon in her work, we entertain a possible sarcastic interpretation, naturally derived from her analysis. Consider the following example from English15:

- (47)

- Do you want to go to San Francisco? I think that it is a very ugly and boring place.

- (shrugging) Okay, I’ll drive you to beautiful San Francisco tomorrow.

In the above example, the meaning contributed by ‘beautiful’ (which is arguably not-at-issue, ‘beautiful’ being non-restrictive here) is the opposite of that contributed by the use of ‘ugly’ in the first part of the speaker’s utterance. This makes the whole utterance inconsistent at the level of literal meaning. However, the use of ‘ugly’ clarifies that the speaker is using ‘beautiful’ sarcastically, not being committed to its truth (opting out from the Gricean Quality maxim). The sentence is thereby consistent under a sarcastic reading.

On a par, the use of -mas/des- in the same sentence that contains a non-honorific pronoun such as kisama or temee, as in (45a) leads to inconsistency at the level of literal meaning since one item is treated as an honorific expression and the other as non-honorific. Like the use of ‘ugly’ and ‘boring’ in (47), the use of temee shows that the speaker is not observing the Maxim of Quality for the moment. That is, although the speaker uses -mas/des-, she is not committed to its truth. Instead, -mas/des- is being used sarcastically with its inverted meaning to convey the lack of politeness.

Although plausible at first, this line of reasoning is not correct. It predicts that in the case of a mismatch, the meaning of one of the honorific items (typically, the one positively specified for honorificity, i.e., -mas/des-) is inverted. However, under the sarcastic reading for the sentence in (45a), it is the meaning of ‘genius’ that is inverted. Both honorific items retain their meaning — the 2P pronoun temee retains its non-honorific meaning, and -mas/des- continues to indicate speaker’s politeness. This reading is provided in (48). The same facts obtain with a mismatching structure containing kisama and -mas/des-.

- (48)

- Available sarcastic reading

- (i)

- You are not a genius. (the at-issue meaning)

- (ii)

- The speaker expresses a negative attitude towards the addressee, and the speaker is higher in social status than the addressee (< temee).

- (iii)

- The speaker is polite. (< des-)

This shows that a mismatching 2P pronoun and allocutive marker are in principle compatible under their sincere meanings in a clause. Instead, it is the presence of ‘genius’ which gives rise to sarcasm, potentially because it denotes the extreme end of a normatively-loaded scale, and is thereby a natural target for sarcasm. Sarcastic inversion applied to ‘genius’ like items contributes a value at the scale’s extreme other end (e.g., Camp 2012).

If we are on the right track and sarcasm is not due to the mismatching pronoun and allocutive marker, we make three predictions: (a) we should optionally obtain a literal reading for (45a) (pace McCready 2019), as in the English sentence You are a genius, where ‘genius’ can be interpreted both literally and sarcastically, (b) a sarcastic reading should also obtain with a matching 2P pronoun and -mas/des- in the presence of an evaluative predicate such as ‘genius’ and (c) replacing genius with a non-evaluative predicate in a mismatching sentence should yield literal readings with more ease. All of these predictions are borne out.

First, let us begin with a context where (45a) can be used literally.16 Consider a speaker who is generally hostile towards X and addresses him via temee. In a specific situation, the speaker is completely amazed by the achievement of X: in such a situation, the utterance of the sentence in (45a) by the speaker truly means that the addressee is a ‘genius’. She continues to use temee because she cannot change the convention used up until then. While there is some weakening in the negative nuance conveyed by temee, it can still not be interpreted as polite. The meaning of -mas/des- as a politeness marker is maintained as well.

- (49)

- Available literal reading

- (i)

- You are a genius. (the at-issue meaning)

- (ii)

- There is a negative attitude towards the addressee, and the speaker is higher in social status than the addressee (< temee)

- (iii)

- the speaker is polite. (< des-)

Secondly, a sarcastic reading also obtains with the predicate ‘genius’ in a sentence containing two expressions that match in honorificity, such as anata and -mas/des-, as shown in (50). Imagine a context where the addressee did something foolish. Instead of accusing the addressee directly, the speaker can utter the following sentence with ‘genius’ to convey the opposite meaning.

- (50)

- Anata-wa

- 2h-top

- tensai

- genius

- des-u.

- cop.alloc.h-prs

- ‘You are a genius.’

Finally, we show that replacing the evaluative predicate with a non-evaluative one in a mismatching sentence yields literal readings freely. Consider our examples in (51a), which contain a non-evaluative predicate such as ‘understand’, which is standardly not taken to evoke normative scales. The sentence in (51a) is a mismatching example, with temee and des- in the presence of ‘understand’. In contrast, the matching sentence in (51b) with the same predicate contains anata and des-.

- (51)

- a.

- Temee-ni-wa

- 2nh-dat-top

- watasi-no

- 1sg-gen

- kuroo-wa

- struggle-top

- wakar-anai

- understand-neg

- des-yoo-ne.

- alloc.h-epi-sfp

- ‘You will never understand my struggles.’

- b.

- Anata-ni-wa

- 2h-dat-top

- watasi-no

- 1sg-gen

- kuroo-wa

- trouble-top

- wakar-anai

- understand-neg

- des-yoo-ne.

- alloc.h-epi-sfp

- ‘You will never understand my struggles.’

If the mismatch between temee and -mas/des- is truly incompatible at the level of literal meaning, we should only obtain a sarcastic reading for (51a), where the meaning of -mas/des- is inverted. Such meaning inversion should not be obligatory in (51b), which contains two matching honorific items. However, if the sarcastic reading in (45a) is due to other reasons (e.g., meaning of ‘genius’) and not due to the mismatch between temee and -mas/des-, (51a) should allow a literal interpretation. We obtain a literal reading for (51a). It is used felicitously in a quarrel between two people of a high social status (e.g., two officials in an office). Imagine a context where the speaker is an official who is upset with the addressee (who is also an official) because she blames him for the decrease in income despite her considerable efforts in the project. Due to being particularly upset with the addressee, the speaker uses temee to indicate hostility. However, since the speaker wants to appear decent in view of her high status, she also uses des- with its literal meaning. The same interpretation obtains for des- in (51b) where the pronoun is matching (i.e., honorific).

In summary, this section has shown that in structures with mismatching honorific items, sarcastic readings may seem prominent in the presence of evaluative predicates. However, literal readings are available too. In Table 7, we summarise the availability of literal readings with different combinations of 2P pronouns and allocutivity with different predicates.

Literal readings across (mis)matching structures with different predicates.

| Allocutivity | 2P Pronoun | Predicate | Literal readings |

| Honorific | Non-honorific | Non-evaluative | Y |

| Honorific | Honorific | Non-evaluative | Y |

| Honorific | Non-honorific | Evaluative | Y |

| Honorific | Honorific | Evaluative | Y |

The obvious question that arises is as follows: what allows the sincere co-occurrence of the honorific allocutive marker with a non-honorific 2P pronoun in the pragmatic component of Japanese?

4.3 Proposal

To explain the grammatical co-occurrence of kisama with -mas/des- within the same sentence, we propose that:

- (52)

- a.

- The meanings of 2P pronouns and honorific allocutivity are distinct in Japanese.

- b.

- The meanings of 2P pronouns and honorific allocutivity are incomparable in Japanese.

The first bullet in (52a) is what is already assumed in McCready (2019). (52b) constitutes the major revision that we propose. Given (52a) and (52b), meanings of 2P pronouns and allocutivity are not only distinct but also incomparable. This means that nothing should prevent non-honorific 2P pronouns and honorific allocutivity from coexisting within a single sentence. As long as we can find an accommodating context, we can felicitously use mismatching sentences, as in (46).

4.3.1 (Un)specified addressee

A natural question that needs to be answered is: how do -mas and des- differ in their expressive meaning vis-à-vis 2P pronouns? We will argue that unlike the 2P pronoun, -mas/des- encode the speaker’s intent to be polite to an unspecified addressee.

A speech act usually consists of two speech act participants: a speaker and an addressee. We label an addressee who the speaker is talking to directly at utterance time tu as a Specified Addressee (henceforth Adr). On the other hand, an addressee towards whom a certain message is targeted but who is not being spoken to directly is an Unspecified Addressee (henceforth Adr*). Adr* requires the presence of some addressee in the context; however, the addressee is usually understood as nonspecific. In other words, this addressee may remain unidentified. Akin to Portner et al. (2019), we propose that lexical items that encode the hierarchical relation between the speaker and the addressee presuppose the reference to an Adr. In contrast, for lexical items that are uninformative about the hierarchical relation between the speaker and the addressee, the addressee may remain unidentified (Adr*). In view of this divide, we propose that 2P pronouns in Japanese reference an Adr, as opposed to -mas/des- that makes reference to an Adr*. We start with the allocutive marker.

First of all, -mas/des- cannot be used in a monologue/soliloquy, where there is no addressee in the speech act, so it is safe to say that they are allocutive elements, which make reference to some addressee, as has been claimed in the previous literature (Miyagawa 1987; 2012; 2017; 2022; Yamada 2019).17

- (53)

- [Context: The speaker is walking alone asking himself what he will cook for dinner.]

- Kyoo-wa

- today-top

- nani-ni

- what-dat

- {sur-u/?*si-mas-u}?

- do-prs/do-alloc.h-prs

- ‘What will I cook today?’

However, the notion of the addressee expressed via -mas/des- is that of an Adr*, and not an Adr that a speaker is talking to directly in an interaction. To this end, we first show that the use of -mas and des- is orthogonal to the social status/hierarchy of the addressee. To clarify this property, Yamada & Donatelli (2021) propose the teacher-student test, as in (54).

- (54)

- Teacher-Student Test

- Can a teacher/president (someone with a higher social status) use the honorific form to a student/employee (someone with a lower social status) without intentionally violating the expectation in the society?

It has been observed for Korean in the literature that a superior sometimes uses an honorific marking to an inferior intentionally in order to make a certain conversational effect. For example, a mother may temporarily use an honorific allocutive marker to her son to praise his achievement (Portner et al. 2019). But such a temporal shift is not what the teacher-student test concerns. It asks whether a superior uses an honorific allocutive marker ‘normally’ to an inferior such that this use is not considered exceptional (e.g it does not praise the addressee). For example, suppose that a teacher is teaching history to elementary school students, and utters the following sentence.

- (55)

- [Context: in a lecture in an elementary school]

- Dainizi

- second

- sekai

- world

- taisen-wa

- war-top

- 1945-nen-ni

- 1945-year-in

- owari-masi-ta.

- end-alloc.h-pst

- ‘The WWII ended in 1945.’

Even though the teacher is considered to have a socially higher status than the students, the sentence in (55) can be felicitously uttered without praising them; if anything, this is the unmarked speech style for teachers. Furthermore, the Emperor uses addressee-honorific markers when talking to the citizens. Thus, Japanese honorific allocutivity can be used both when the addressee has a higher or a lower social status. This can underlie two possibilities: (a) either -mas has a feature that encodes the hierarchical relation between the speaker and the addressee (e.g., status), which is valued as Sp>/<Adr, or (b) -mas lacks such a feature altogether. Under both possibilities, -mas can be used both by a speaker who is higher than the addressee, and by a speaker lower than the addressee. However, possibility (a) where -mas contains a status like feature presupposes a specific addressee (who can be lower or higher in status than the speaker), while no such presupposition is made in possibility (b). We show that possibility (b) is correct since -mas can be used felicitously in a situation where the speaker does not know who they are talking to. To this end, we propose the flyer-test, as defined below.

- (56)

- Flyer test

- Can an honorific allocutive marker felicitously used in a flyer (i.e., in a situation where the writer (the speaker) cannot identify who the addressee is)?

It has previously been noted for languages such as Punjabi and Korean that they disallow (non-)honorific encoding allocutive markers in contexts that lack a specific addressee (see Portner et al. 2019 for Korean, and Kaur 2020b for Punjabi). For example, let us imagine that there is a poster on the wall alerting people to the dangers of heat stroke. As is shown in (57a), the Punjabi honorific allocutive marking would be infelicitous on such a poster. The honorific allocutive marker je is felicitious only when the speaker is talking directly to an individual. Contrast this with the Japanese sentence in (57b), which is perfectly acceptable on such a poster, suggesting that identification of the addressee is not a necessary condition on the use of these allocutive markers. In other words, the addressee of -mas and des- can be unspecified.

- (57)

- a.

- Garmii

- summer

- bimaariyãã-daa

- diseases-gen

- mausam

- season

- {e/#je}.

- be.prs/alloc.pl

- ‘Summer is the season of diseases.’

- b.

- Natsu-wa

- summer-top

- nettyusyo-no

- heatstroke-gen

- kisetsu

- season

- {da/des-u}.

- cop.alloc.h-prs

- ‘Summer is the season of heat stroke.’

These observations reveal the semantic and pragmatic profile of Japanese honorific allocutivity. First, it is assumed that there is an addressee, since allocutivity in Japanese cannot be used in a soliloquy. However, allocutivity in Japanese does not evaluate the characteristics of the addressee: it does not provide information on the hierarchical relation between the speaker and the addressee (the teacher-student test), and can be used in contexts that lack a specific addressee (the flyer test). We claim that -mas/des- only encode the speaker’s intent to be polite, irrespective of the properties of a specific addressee (Yamada 2019: Ch.4). Thus, we claim that the allocutive marker in Japanese references the Adr*.18 A range of factors including social distance, psychological distance, formality and many other factors combinatorially affect the speaker’s decision to use allocutive markers and express their politeness (Shibatani 1998; McCready 2014; 2019; Yamada 2019; Yamada & Donatelli 2021).

For non-native speakers of this language, this notion of ‘politeness’ might be hard to understand. As an analogy, an honorific allocutive marker is akin to ‘an individual’s (say X’s) choice to wear a suit.’ By wearing a suit, X can express his/her polite formal attitude to people seeing them, regardless of their own status or that of the people watching them. Of course, this is not obligatory, and X can wear a T-shirt. However, when wearing a suit, the audience would infer X’s intent to be polite/well-behaved. X can also take a picture of himself to make a poster, and he can wear a suit in that picture. It is not known who will see the poster at the time of taking the picture. But people seeing the picture receive the message of politeness on the basis of X’s decision to wear a suit, as opposed to him wearing a T-shirt, thus creating a well-behaved publicized-image of the wearer (i.e., X) (Yamada 2019: Ch. 4). The aforementioned properties of allocutivity in Japanese are also evident in the suit-wearing scenarios. First, someone wearing a suit presupposes the presence of an addressee. But this addressee can be unspecified. Second, wearing a suit does not evaluate the property of the addressee. What it encodes is the speaker’s intent to be polite. The motivation for wearing a suit can also not be predicted by a single social factor. Psychological and sociological factors jointly have an influence on people’s decision to present themselves as well-behaved and proper.

In contrast with the allocutive markers, 2P pronouns in Japanese are lexical items that obligatorily provide information about the hierarchical relation between the speaker and the addressee. Therefore, they make reference to the Adr (and not just Adr*). Consider the use of anata. It is a polite 2P pronoun, usually uttered by a speaker who is socially superior to the addressee. For instance, it is felicitously used by a teacher (higher speaker) to a student (lower addressee). However, to the extent that pronouns can be used to address teachers, a student cannot use anata to a teacher, as shown in (58). The status requirement is too strong to be pragmatically nullified.

- (58)

- [Context: from a student to a teacher]

- #Anata-wa

- 2P-top

- sensei

- teacher

- des-u.

- cop.alloc.h-prs

- ‘You are a teacher (intended).’

Similarly, take a pronoun like sotti, which is more flexible in that it can be used by a higher speaker to a lower addressee (e.g., teacher to student). In addition, it can be used by a speaker equal in status as the addressee (a teacher to another teacher). Again, students generally cannot use it when talking to a teacher. If however, a student uses it, a special effect is generated; the student would be perceived as being ill-behaved since (s)he is assuming that their status is at least as high as that of the teacher. Thus, there is an intentional violation of the social expectations.

Thus, unlike -mas/des- which can be used by a speaker who is either higher or lower than the addressee without generating any special conversational effects, 2P pronouns pattern differently. The 2P pronoun anata comes specified for a certain hierarchical relation between the speaker and the addressee (Sp > Adr), which cannot be reversed. With sotti, which is specified as (Sp >/= Adr), it is occasionally possible for a lower speaker (e.g., a student) to use it. However, this is interpreted as a violation of the social expectations. We take this to suggest that 2P pronouns encode the speaker-addressee hierarchy, which in turn presupposes a specified addressee (Adr).

In summary, 2P pronouns and -mas/des- vary in their expressive meaning pertaining to the evaluation of the addressee. While 2P pronouns express the attitude of the speaker based on the characteristics of a specific addressee (Adr), the use of -mas/des- underlies an Adr*. -mas/des- encode the speaker’s intent to be polite, as a tool to enhance his/her self-image, irrespective of who the addressee is.

4.3.2 Deriving mismatches

The genuine mismatching examples are no longer a mystery. Let us revisit the mismatching examples, repeated here as (59):

- (59)

- a.

- Kisama-ni-wa

- 2nh-dat-top

- wakar-anai

- understand-neg

- des-yoo-ne.

- cop.alloc.h-epi-sfp

- ‘You do not understand (this).’

- b.

- Temee-ni-wa

- 2nh-with-top

- kankee

- relation

- nai

- absent

- des-u-yone?

- cop.alloc.h-prs-sfp

- ‘This has nothing to do with you, right?’

First, the ‘honorific’ information on the pronoun kisama/temee lies in the N-layer and therefore has no syntactic relation with a clause peripheral licenser (e.g., c). Hence, there is nothing in syntax that forces the pronoun to match the honorific allocutive marker in honorificity. Second, dispensing with the tacitly accepted assumption in the previous literature that honorific expressive meaning on 2P pronouns and allocutive markers are always comparable, we have shown that the meanings encoded by the 2P pronouns and -mas/des- are not comparable, and contribute independently to the meaning of the entire sentence.

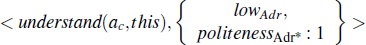

The mismatches can be derived in the following way: in line with McCready (2019), we assume that a non-honorific 2P pronoun such as temee or kisama indicates that the speaker makes public an expectation that they will not behave formally toward the addressee based on their negative evaluation of the addressee. It is crucial that this semantics encodes reference to a specific addressee (Adr), which we indicate via a subscript ‘Adr’. In contrast, for the allocutive marker, which does not make reference to a specific addressee but only Adr*, we label the semantic meaning only as ‘Politeness’. Instead of an interval-based analysis of -mas/des- as assumed earlier in (45b), we utilize a non-negative integer (e.g., 0(–) and 1(+)) to encode the speaker’s intent to be polite in the presence of an Adr*. Thus, for a sentence as in (59b), we have the set of of meanings as shown below.

- (60)

Since lowAdr and politenessAdr*:1 are semantically distinct objects, no comparison is made. Each of these semantic objects update different components of the structured discourse context. As is widely assumed in dynamic pragmatics, the discourse context is structured such that it contains distinct components, which are updated by distinct types of semantic information. For instance, Portner’s (2004; 2007) version of the structured discourse context contains a common ground, a question set, and a To-Do list function. A common ground is a set of propositions, a question set is a set of questions and a To-Do list function is a function from individuals to a set of properties. The semantic value of a declarative sentence is a proposition, and it updates the common ground. Similarly, the semantic value of an interrogative sentence updates the question set, and so on and so forth. In line with the above discussion, which assumes that different components of a discourse context do the job of representing different aspects of the discourse, we posit distinct discourse components relevant for honorific elements. Based on the semantic type of each honorific element, a distinct component of the discourse context is updated. Since the meanings of pronouns and -mas/des- in Japanese have two distinct semantic values, i.e., lowAdr and politeness:1, they update different discourse components (cf., Yamada & Donatelli 2021).19 Consequently, the seemingly contradicting example in (59) does not result in a fatal pragmatic error, generating grammatical combinations of -mas with both honorific and non-honorific 2P pronouns. Albeit rare, there are suitable conversational setups where a combination of -mas/des- with a non-honorific 2P pronoun is felicitously used to be aggressive toward someone while still being polite. For instance, recall that examples as in (59) are felicitous in a quarrel between two people in high social status.

5 Conclusion and future directions