1 Utterance Honorifics

Utterance Honorifics (UHs) give an honorific character to the entire speech act associated with the sentence, indicating that the speaker is being respectful to the addressee/audience (McCready 2019, Chap 4).1 Japanese is among the languages in which the UH marking is frequent and pervasive. (1a) is a declarative sentence in the plain form whereas (2a) comes with the utterance honorific marker -mas- attached to the verb.

- (1)

- Plain

- a.

- Maria-wa

- Maria-top

- kaigi-ni

- meeting-loc

- ki-ta.

- come-past

- ‘Maria came to the meeting.’

- b.

- Honorific meaning: Ø

- (2)

- Utterance Honorific

- a.

- Maria-wa

- Maria-top

- kaigi-ni

- meeting-loc

- ki-mashi-ta.

- come-uh-past

- ‘Maria came to the meeting.’

- b.

- Honorific meaning: The speaker is being respectful to the addressee/audience.

The two sentences denote the same semantic content – the proposition that Maria came to the meeting. The difference between them lies in the level of politeness and formality. The presence of -mas- in (2a) indicates that the speaker is being deferential to the addressee in communicating the propositional content of the sentence. It is therefore the preferred style of speech when the conversation is taking place in a formal setting. (1a) can be a monologue when there is no need to make reference to the addressee. When there is an addressee, the relationship between the speaker and the addressee is assumed to be close and friendly, or else it is asymmetric in such a way that the speaker is distinctly higher in the social standing than the addressee – a kind of relationship that makes the speaker feel comfortable and secure enough not to be demonstratively respectful to the addressee.

Since the interpretive effect of an utterance honorific marker concerns the speaker’s attitude towards the addressee/audience, its relevance is computed at the utterance level (hence its name). It is therefore natural to regard the utterance honorific marking as a main clause phenomenon, and analyses along these lines have been proposed. Miyagawa (2012), for instance, categorizes the UH marking in Japanese on a par with the allocutive agreement in Basque and analyzes it as an instance of addressee agreement. The presence of an addressee argument is tied to the Speech Act Phrase (SAP), and given that the projection of SAP is primarily limited to the matrix level, the UH marking is also largely a main clause phenomenon. Portner, Pak & Zanuttini (2019) generally concur with this view. Comparing UHs with content-oriented honorifics (such as subject-oriented honorifics in Japanese), they claim (p.2) that ‘a key grammatical difference between content-oriented and utterance-oriented markers is that the former can be readily embedded, but in many cases the latter cannot be.’ These authors all acknowledge, however, that UHs in Japanese can be found in some embedded contexts (Miyagawa 2012, Section 7; Portner, Pak & Zanuttini 2019, p.28). Indeed, such observations have been reported by several other authors, such as Tagashira (1973), Harada (1976), Minami (1987), Uchibori (2008), and most recently, Yamada (2019).

In this paper, we closely examine UHs under various embedding environments. In doing so, we compare the three UH markers, namely -mas-, which attaches to a verb, and the two varieties of the UH copula -des-: -desN- and -desA-, which suffix to a noun and an adjective, respectively. It will be shown that these UH markers behave differently under embedding, and our first objective is to provide descriptive generalizations of the distributional patterns of those UH markers. We further argue that the embeddability of the Japanese UHs is almost exclusively determined by the morpho-syntactic features of the UH markers and the surrounding functional heads. Our proposal is based on the observation that the three UH markers are mapped onto a clear ordering in terms of how rich the conjugational paradigm is. While -mas- maintains most of the conjugational patterns of a lexical verb, -desN- shows only a small subset of them. The most extreme is -desA-, which is found to be morphologically invariant. This ordering is directly translated into their syntactic position: -mas- is projected in the vP-edge region, as it maintains most of the inflectional patterns of a lexical verb. The UH copulas are inserted in higher positions. Of the two varieties of the copula -des-, -desA- is inserted at the highest layer of the CP periphery whereas the position of -desN- is in the IP periphery, interacting with tense morphology. The difference in the syntactic ‘height’ is argued to correspond, at least partially and possibly entirely, to the embeddability contrast among the UH markers. The lowest UH -mas- is the most embeddable, the highest -desA- resists most strongly to embedding, and -desN- sits in the middle. There are some intricate micro-variations with -desN-, however, and it leads to the speculation that being tensed and being finite are separate notions in Japanese. The paper ends with some speculative discussion on the notion of ‘honorific concord’ and the problem that complement clauses of attitude verbs present.

2 Embedding Patterns of Utterance Honorific Markers

2.1 Three Types of Utterance Honorific Markers in Japanese

In this section, we briefly introduce the three UH markers in Japanese: -mas-, -desN- and -desA-. The basic distributions of these UHs are as follows: (i) -mas- is a suffix which attaches to a verb stem, (ii) -desN- is the utterance honorified copula which attaches to nouns and nominal adjectives, and (iii) -desA- is a suffix which attaches to canonical adjectives. Take a look at (3) and (4a,b), which are examples of -mas-, -desN- and -desA-, respectively.

- (3)

- Maria-wa

- Maria-top

- asa

- morning

- hayaku

- early

- okiru

- rise.pres

- /

- /

- oki-masu.

- rise-uh.pres

- ‘Maria gets up early in the morning.’

- (4)

- a.

- Maria-wa

- Maria-top

- supein-jin-da

- Spain-person-be.plain

- /

- /

- supein-jin-desu.

- Spain-person-be.uh

- ‘Maria is a Spaniard.’

- b.

- Maria-wa

- Marai-top

- yasahii-Ø

- kind-Ø

- /

- /

- yasahii-desu.

- kind-be.uh

- ‘Maria is kind.’

As seen in (3), -mas- attaches to the verb stem oki- ‘rise’. In (4a), -desN- attaches to a noun supein-jin ‘Spaniard’. In (4b), -desA- comes right after an canonical adjective yasahii. Here, some might wonder why we make a distinction between -desN- and -desA- though they are morphologically identical. We will provide a clear reason for this in section 2.3, however, and the important observation at this point is that -desN- replaces the copula -da while -desA- is directly attached to the adjective.

Before getting into the close examination of embedded UHs, we would like to mention the peculiarity of the ‘quotative’ environment. Unlike other subordinate clauses, a quotative phrase with -to can host all the UHs markers above without any restriction. Observe the examples in (5) and (6).

- (5)

- Maria-wa1

- Maria-top

- [pro1

- pro

- mai-asa

- every-morning

- hayaku

- early

- oki-masu]-to

- rise-uh.pres-comp

- it-ta

- say-past

- ‘Maria said, “I get up early every morning”.’

- (6)

- a.

- Anna-wa

- Anna-top

- [Maria-wa

- Maria-top

- supein-jin-desu]-to

- Spain-person-be.uh-comp

- it-ta.

- say-past

- ‘Anna said, “Maria is a Spaniard”.’

- b.

- Anna-wa

- Anna-top

- [Maria-wa

- Maria-top

- yasahii-desu]-to

- kind-be.uh-comp

- it-ta.

- say-past

- ‘Anna said, “Maria is kind”.’

In both (5) and (6), -to indicates that the phrase is an direct quote of what Maria/Anna said. In those cases, UH markers can be embedded under -to as long as Maria/Anna said so. This fact is actually not surprising because even the strictest main clause phenomena, such as Right Dislocation sentences (cf. Tanaka 2001; Tomioka 2016), can appear in this environment as shown in (7).

- (7)

- Maria-wa

- Maria-top

- [ashita

- [tomorrow

- iku-no,

- go-q,

- daigaku-ni]-to

- university-loc]-comp

- kii-ta.

- ask-past

- ‘Maria asked, ‘will (you) go (there), to the University?’

In this respect, the quotative environment is quite different from other subordinate clauses which we are interested in.

It is also noteworthy that the quotative environment does not require the root sentence to be marked with an UH marker. As seen in (5) and (6), the matrix verb it-ta ‘say-past’ stays in a plain form but not in a UH form ii-mashi-ta ‘say-uh-past’. Again, this is not the case of other embedding environments such as relative clauses or conditionals: the embedded UHs under these subordinate clauses require the matrix verb to be UH form as we will see later. Thus, quotative context is very different from other cases. In the rest of this paper, we focus on the embedded UH in non-quotative environments.

2.2 Embedding of -mas-

Among the three UH markers, -mas- has attracted the most attention. For instance, Miyagawa (2012) and Yamada (2019) both focus primarily on this UH marker. Its popularity is probably due to the fact that it is the most embeddable of the three. Let us begin with the following three environments: Attitude Complement with koto ‘fact’ (Yamada 2019), temporal adjuncts, and relative clauses (Harada 1976).

- (8)

- Hayaku

- Quickly

- go-kaifuku-nasai-masu

- hon-recover-do.hon-uh

- koto-o

- fact-acc

- o-inori-shite-ori-masu.

- hon-pray-do-be.humble-uh

- ‘I pray for your speedy recovery.’

- (9)

- Go-touchaku-nasai-masu

- hon-arrival-do.hon-uh

- mae-ni

- before-dat

- o-denwa-o

- hon-phone-acc

- itada-ke-masu-deshou-ka?

- receive-can-uh-modal-q

- ‘Would you give us a call before you arrive?’

- (10)

- Senjitsu

- the.other.day

- okutte-itadaki-mashita

- sent-receivehumble-uh.past

- meron,

- melon

- totemo

- very.much

- oishiku

- delicious

- itadaki-mashita.

- consumehumble-uh

- ‘We truly enjoyed the melons that you sent us the other day.’

These examples share one structural property, namely they are embedded clauses under nominal structures.2 In these embedded structures, the embedded predicates must be in rentai-kei, the adnominal form.3

Additionally, -mas- can appear within the gerundive structure with -te and two conditional antecedents: -tara and -to.

- (11)

- Gorenraku-ga

- report-nom

- okure-mashi-te,

- delay-uh-gerund,

- moushiwake-gozai-masen-deshita

- excuse-exist–uh.neg-uh.past

- ‘I sincerely apologize for the delayed communication. ‘

- (12)

- a.

- Go-kaifuku-nasai-mashi-tara

- hon-recover-do.hon-uh-cond

- zehi

- definitely

- mata

- again

- o-koshi-kudasai

- hon-come-please

- ‘Please do come back when you have made a recovery.’

- b.

- Kore-wa

- this-top

- mizu-o

- water-acc

- kuwae-masu-to

- add-uh-and.then

- bouchou-itashi-masu.

- expand-dohumble-uh

- ‘If you add water to this, it will swell up.’

In the gerundive and the -tara conditional structures, the embedded verbs must be in ren’you-kei, the continuous (adverbial) form, whereas the -to conditional requires the verb to be in shuushi-kei, the conclusive form, which is the form used for a dictionary entry.

There are two more environments that are compatible with -mas-, because-clauses with node and kara and although/but clauses with ga and ke(re)do.

- (13)

- Because-clauses

- Watashi-ga

- I-nom

- yatte-oki-masu-kara

- do-complete-uh-because

- /

- /

- -node,

- -because

- mou

- already

- kaette-mo

- return-even

- ii-desu-yo.

- good-uh-dpart

- ‘You may go home because I can finish it (for you).’

- (14)

- But/although-clauses

- Ame-ga

- rain-nom

- futte-ki-mashi-ta-ga

- fall-come-uh-past-but

- /

- /

- -kedo,

- -but

- konomama

- as.is

- tsuzuke-mashou

- continue-uh.Exhort

- ‘Although it started raining, shall we keep going?’

The embedded structures compatible with -mas- are diverse, and the distribution is quite robust. Compared to the (non-contrastive) topic marker -wa, the embedding of -mas- is more permissive. For instance, -wa-phrases are not allowed in relative clauses or temporal adjuncts. It is not the case, however, that -mas- is freely embedded. There are some subordinate structures that do not permit -mas-. As noted by Minami (1987), clauses embedded under nagara/tsutsu ‘while/during’ cannot have -mas-.4

- (15)

- a.

- Hon-o

- book-acc

- yomi-(*mashi)-nagara,

- read-(uh)-while

- omachi-shite-ori-masu.

- wait-do-behumble-uh

- ‘(I) will be waiting (for you) while reading a book.’

- b.

- Sono

- that

- jikan-wa

- time-top

- ofisu-de

- office-at

- koohii-o

- coffee-acc

- nomi-(*mashi-){nagara/tsutsu},

- drink-(uh)-while,

- shigoto-o

- work-acc

- shite-ori-mashi-ta.

- do-behumble-uh-past.

- ‘Regading that time, I was working in my office drinking a cup of coffee.’

When we look at various main clause phenomena under embedding, we often encounter a situation that can be described as either ‘half-empty’ or ‘half-full’: whether something is a main clause phenomenon that can be embedded in some but not all cases or it is not a main clause phenomenon as it can be embedded in some environments. One may consider -mas- as one of such instances, but we would rather describe it as ‘nearly but not completely full’. The range of -mas- embedding structure is quite wide, and it includes the kinds of embedding environments, such as relative clauses and temporal adjuncts, which are known to be resistant to main clause phenomena.

2.3 Embedding of -des-

As briefly described in Section 2.1, there are two variants of the UH copula -des: one attaches to a nominal category (including an adjectival noun), and the other to an adjective. While the two variants are homophonous and look indistinguishable, they should be kept apart. The tables below highlight the relevant differences.

- (16)

- Noun: ame ‘rain’ Adjectival Noun: shizuka ‘quiet’

Plain Honorific Plain Honorific Present ame-da ame-desu shizuka-da shizuka-desu Past ame-datta ame-deshita shizuka-datta shizuka-deshita

- (17)

- Adjective oishii ‘tasty’

Plain Polite Present oishii-Ø oishii-desu Past oishikatta-Ø oishikatta-desu

We often find the description that -des- is the UH version of the plain copula -da. It is certainly the case for -desN-, the variant that attaches to a nominal category, as shown in (16). Moreover, the copula itself inflects for tense, both in the plain form and in the honorific form. It is a different story for -desA-. As shown in (17), an adjective in the plain form cannot be accompanied by -da. An adjective alone appears in the plain form, and it inflects for tense. The UH copula -des- is added to an inflected adjective, and its morphological form is invariable.

These differences will turn out to be crucial in our explanation for the embeddability contrasts between the two types of -des-, and their significance will be spelled out fully in Section 3. Presently, we believe that separating the two variants of -des- is justified, and we will proceed to describe their distributions under embedding.

2.3.1 Embedding of -desN-

The embedded structures that cannot license -mas-, such as -nagara- and -tsutsu-clauses, also fail to embed -desN-, but some of the environments that are compatible with -mas- cannot accommodate -desN-. In other words, the embedding structures suitable for -desN- are a proper subset of those that can host -mas-.

The following embedded structures can have -desN-: -te gerundive, -tara / -to conditionals, because-clauses, and although/but-clauses.

- (18)

- a.

- Tsuma-ga

- wife-nom

- amerikajin-deshi-te,

- American-be.uh-gerund,

- ie-de-mo

- home-loc-also

- eigo-o

- English-acc

- tsukatte-ori-masu.

- use-be-uh

- ‘My wife being American, we use English at home.’

- b.

- Raishuu-wa

- Next.week-top

- suiyoubi-deshi-tara

- Wednesday-be.uh-past-cond

- aite-ori-masu-ga…

- open-behumble-uh-but…

- ‘About next week, if it’s Wednesday, I will be free.’

- c.

- Kokuseki-ga

- citizenship-nom

- amerika-desu-to,

- America-be.uh-cond,

- biza-ga

- visa-nom

- iri-masu-ne.

- necessary-uh-dpart

- ‘If you are an American citizen, you need a visa.’

- d.

- Raishuu-no

- Next.week-gen

- suiyoubi-wa

- Wednesday-top

- hima-desu-kara,

- leisure-be.uh-because

- zehi

- definitely

- kite-kudasai

- come-please.

- ‘Because I will be free on Wednesday next week, please come (to see me).’

- e.

- Toukyou-wa

- Tokyo-top

- daitokai-desu-ga/kedo,

- big.city-be.uh-but/but,

- sonowarini

- rather.unexpectedly

- anzen-desu.

- safe-be.uh

- ‘Tokyo is a big city, but it is safe (rather surprisingly).’

However, the other embedding structures that permit -mas do not allow -desN-, namely attitude complements with koto, temporal adjuncts, and relative clauses.

- (19)

- a.

- *Shinseihin-ga

- new.product-top

- daiseikou-desu-koto-o

- big.success-be.uh-fact-acc

- o-inori-shite-ori-masu.

- hon-pray-do-be.humble-uh.

- ‘I sincerely hope that your new product will be a big success.’

- b.

- *Kuruma-ga

- car-nom

- ojama-desu-baai-wa

- nuisance-be.uh-case-top

- sugu

- immediately

- o-moushituke-kudasai.

- hon-inform.hon-please.

- When the car is in your way, please tell us immediately.

- c.

- *Tanaka-san-o

- Tanaka-hon-acc

- gozonji-desu-kata-ni

- acquainted-be.uh-person.hon-dat

- go-shoukai-itada-ke-mase-n-ka?

- hon-introduction-receive.humble-can-uh–neg-q?

- ‘Could you introduce (me/us) to someone who knows Mrs. Tanaka?’

These structures have one feature in common. They are subordinate clauses embedded under nominal structures, and the embedded predicates must be in the adnominal form (rentai-kei). Conversely, the embedded clauses that permit -desN- require either the continuous form (ren’you-kei) or the conclusive form (shuushi-kei).

2.3.2 Embedding of -desA-

The second type of the UH copula, -desA-, is banned in all the embedding clauses that disallow -desN-. Thus, -nagara-, -tsutsu-clauses, attitude complements with koto, temporal adjuncts, and relative clauses do not permit -desA-. The distribution of -desA- is further restricted, as some of the -desN-–compatible clauses do not allow -desA-. More concretely, -te gerundive and -tara / to conditionals are not suitable environments for -desA-.

- (20)

- a.

- *Kyou-wa

- Today-top

- isogashii-deshi-te,

- busy-be.uh-gerund,

- sochira-ni-wa

- there-loc-top

- oukagai-deki-mas-en.

- visithumble-can-uh–neg

- ‘It is such a busy day today, regrettably, so I cannot go over there.’

- b.

- *Raishuu

- Next.week

- o-isogashii-deshi-tara

- hon-busy-be.uh-cond

- o-tetsudai-ni

- hon-assist-dat

- ukagai-masu.

- go.humble-uh

- ‘If you are busy next week, I will come to help you.’

- c.

- ???Nedan-ga

- Price

- takai-desu-to,

- high-be.uh-cond

- koushou-shi-naosu-koto-ni

- negotiation-do-repear-fact-dat

- nari-masu.

- become-uh

- ‘If the price is high, we will have to re-negotiate.’

The only embedded structures that can accommodate -desA- are because-clauses and although-clauses.

- (21)

- a.

- Raishuu-wa

- Next.week-top

- isogashii-desu-kara,

- busy-be.uh-because

- saraishuu-ni

- the.week.after.next-dat

- shite-kudasai

- make-please

- ‘Because I will be busy next week, please make it to the following week.’

- b.

- Raishuu-wa

- Next.week-top

- isogashii-desu-ga/kedo,

- busy-be.uh-but/but,

- kanarazu

- certainly

- ai-ni

- see-dat

- iki-masu.

- go-uh

- ‘Although I will be busy next week, I will definitely come see you.’

To sum up, -desA- shows the most restricted distribution under embedding of the three UH markers.

2.4 Summary

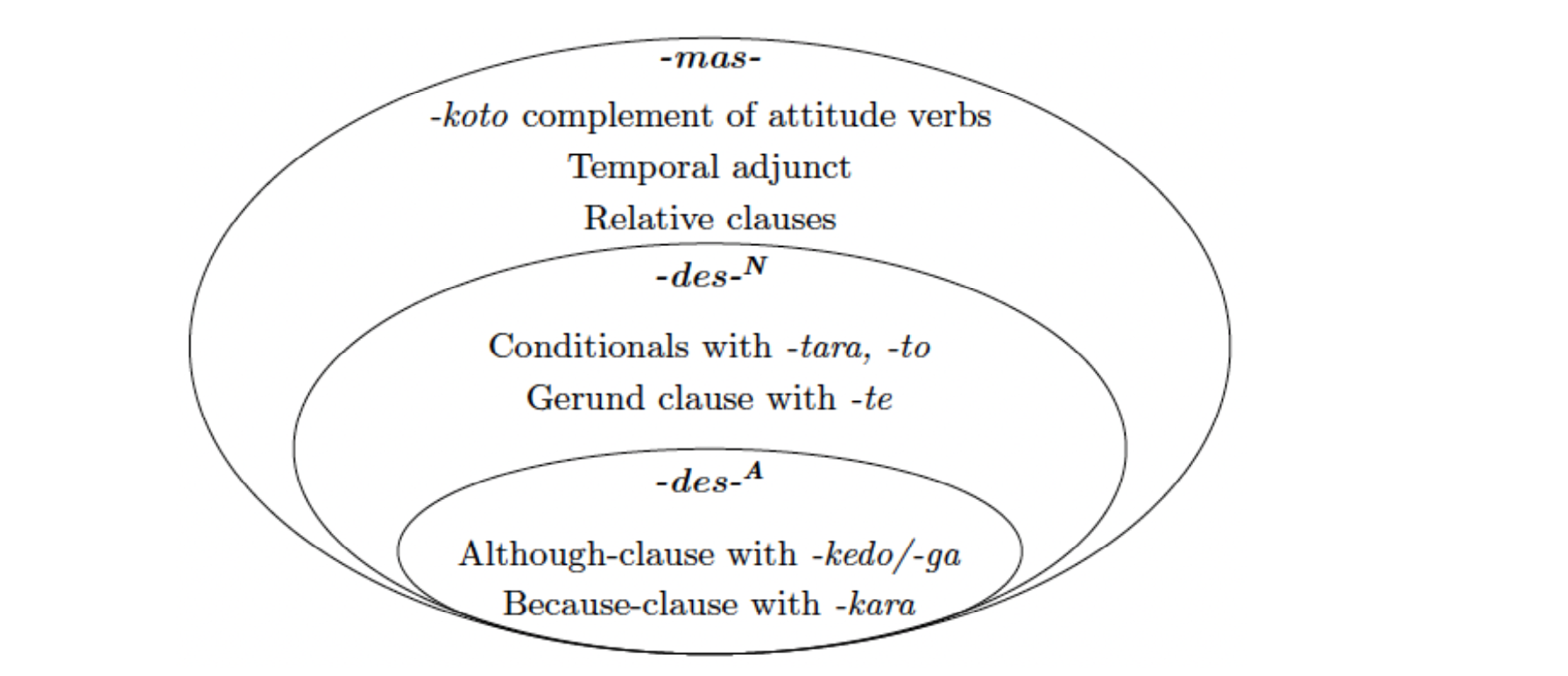

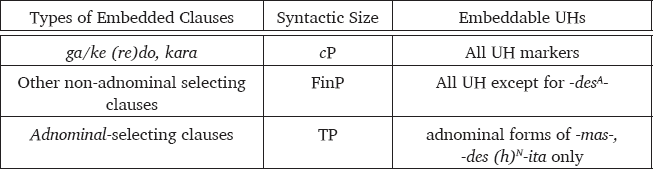

The examination of the embedding possibilities for the three UH markers reveals that their distributional patterns are not just randomly different but show a (proper) subset-superset relation illustrated below.

- (22)

The verbal UH -mas- can be embedded in a wide variety of embedded clauses, but only a proper subset of them are compatible with -desN-. Even a smaller proper subset applies to -desA- with because- and although-clauses being the only compatible structures. In other words, the embeddability of the UH markers becomes progressively more restricted in the order of -mas- → -desN- → -desA-. The pattern is rather surprising since the semantic/pragmatic contributions of UHs do not vary among the three UH markers. They all add such honorific characteristics as politeness, deference, and formality to the utterances.

When a supposed root phenomenon is found within a class of embedded structures, one looks for some ‘root-like’ attribute that is shared by those embedding environments. This kind of solution has been proposed, for instance, for fronting operations under embedding (e.g., Haegeman 2012) and embedded topics with -wa in Japanese (e.g. Tomioka 2015). Most recently, Yamada (2019, 5.3.2) makes a proposal within this tradition. He argues, focusing on -mas-, that the embedding of the UH marker is tied to the embedding of a speech act in the form of a Speaker Projection (SpP) and an Addressee Projection (AddrP). When embedded, an AddrP licenses an embedded occurrence of -mas- via local agreement. While Yamada’s analysis is consistent with the generally accepted view that an agreement relation is established locally, the distributional patterns illustrated above cannot be easily accommodated by such a strategy.5 If the presence of an AddrP in a given embedding environment licenses -mas-, the same environment should license the other UH markers. Moreover, some of the -mas- embedding structures, such as relative clauses, are not known to have strong root-like characteristics, and it is highly unlikely that a relative clause furnishes its own SpP and AddrP. All in all, the common wisdom we have gained from our experiences with embedded root phenomena is not very useful for the problem at hand.

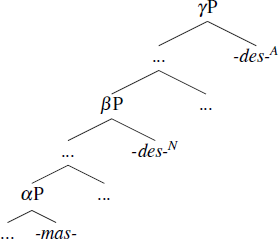

We therefore opt for a dramatically different approach. Our proposal is based on the following steps.

- (23)

- a.

- Different embedders target clauses of different sizes.

- b.

- The three UH markers occupy different syntactic positions at the Spell-Out: -des-A is in the highest position, followed by -des-N and -mas-.

- (24)

The combination of (23ab) gives the implicational pattern from the proper subset-superset relation without any additional ingredients. If a given embedder targets βP, for instance, it can contain -desN- and -mas- but not -desA-. An embedding structure which selects αP can have -mas-, but neither -desN- nor -desA- can be included in it.

In what follows, we will closely examine morphosyntactic characteristics of the three UH markers. We first argue that the structural differences depicted in (23b) are justified. Then, we will investigate whether the structure–embeddability correspondence can account for the proper superset-subset embedding pattern. The answer to this question will turn out to be a little more complex and nuanced, and it depends on how the morphosyntax of the adnominal form of a predicate is translated into the formal syntactic framework that this paper is couched within. In our pursuit of a proper analysis, we will make our best effort to identify the precise syntactic locations of the three UH markers, but there may still be some uncertainties and room for debate. We nonetheless believe that our proposal for the overall relative hierarchical relations among the UHs has strong empirical support.6

3 Morphosyntax of Utterance Honorific Markers

3.1 Theoretical Assumptions

Before analyzing the morphosyntactic characteristics of the three UH markers in detail, we will spell out some crucial theoretical concepts that we assume in our analysis. First of all, we follow Portner et al. (2019) and assume that there is a functional head that encodes the information concerning the speaker’s attitude and relative social standing to the addressee. In Portner et al. (2019), it is c0, and the projection of cP is limited to the root clause level. We generally concur with this view although we will show a few instances of ‘root-like’ subordinate clauses that can embed a cP.

We further assume that the information related to UHs must be morphologically realized. However, the morphological realization does not require that the relevant c0 is filled. We assume instead that the honorific features located in c0 can be made overt anywhere in the extended verbal projection in the sense of Grimshaw (2000; 2005). With the upper periphery being extended to include a cP, the extended verbal projection begins with a lexical verbal projection and ends with a cP. In (25), finer distinctions within a CP of Rizzi (1997; 2004) and other potential functional projections within a TP (e.g., AspP, NegP) are omitted.

- (25)

- [cP

- [CP

- [TP

- [vP

- [VP

- ….. ]]]]]

When an UH marker appears in a lower domain of the extended verbal projection, its appearance is licensed via Agree with c0. The licensing via Agree is straightforward with UHs in root clauses. We will revisit the nature of Agree in connection to UHs in embedded clauses.

We now turn our attention to the morphosyntactic properties of the three UH markers, beginning with -mas-.

3.2 Morphosyntax of -mas-

The UH marker -mas- originated from -mair-as(u), the humble form of ‘go/come’ mair- followed by the causative morpheme -as(u). It acquired more ‘functional’ semantics when it started being used as a humble-benefactive marker, as in (26). Under this use, -mair-as(u) no longer retains the lexical meaning of mair- ‘go/come’.

- (26)

- tasuke-mairas-en-to

- save.life-benefactivehumble-propose-comp

- zonji-sourae-sourou-domo…

- think-humble-humble-but

- ‘Although I think I shall save your life, ….’ from Heike-monogatari, Vol. 9, the death of Atsumori, 14th Century

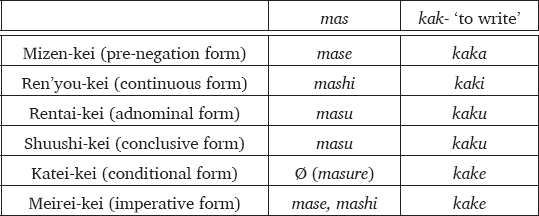

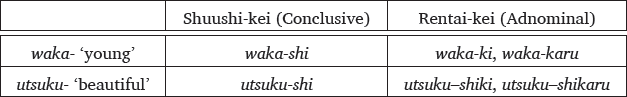

In the traditional grammatical classification of Contemporary Japanese, -mas- is categorized as jodoushi, an auxiliary verb. While it has completely lost the lexical meaning of ‘go/come’, it has kept an almost full conjugational paradigm, as shown below.7 The table also includes the lexical verb kak- ‘to write’ as a reference point.

- (27)

- Conjugational Paradigms of -mas- & kak- ‘to write’

The morphological orderings of -mas- and other verbal suffixes are also revealing. -Mas- always occurs before the negative marker (28a) while it always comes after a voice marker such as causative (28b) or passive (28c). The last two examples also show that -mas- inflects for tense with the past tense suffix -ta following -mas-.

- (28)

- a.

- Mayu-wa

- Mayu-top

- sake-o

- alcohol-acc

- nomi-mase-n-Ø.

- drink-uh–neg-pres

- ‘Mayu does not drink alcoholic beverages.’

- b.

- Mayu-wa

- Mayu-top

- Ken-ni

- Ken-dat

- yasai-o

- vegetables-acc

- tabe-sase-mashi-ta.

- eat-cause-uh-past

- ‘Mayu made Ken eat the greens.’

- c.

- Ken-ga

- Ken-nom

- Mayu-ni

- Mayu-dat

- home-rare-mashi-ta.

- praise-pass-uh-past

- ‘Ken was praised by Mayu.’

These characteristics suggest that -mas- is either a functional category that keeps some lexical attributes or a lexical category whose lexical meaning is bleached out to the extent that, semantically speaking, it is more like a functional category. This intuition translates into two possibilities: (i) a vP can be iterated, and -mas- is a v0 which is generated as the highest v0 or (ii) it is a functional category, yet to be named, that selects a vP. In either case, it is characterizable as a ‘vP–edge’ element. It will be claimed in the following subsection that both versions of -des- are projected relatively higher than -mas-, which is in accordance with the structure–embeddability correspondence scheme shown earlier. One potential complication is that -mas- arguably undergoes a head movement to T0, as it inflects for tense. We will revisit this issue later when we discuss the embeddability of -mas- and -desN-.

3.3 Morphosyntax of -desN- and -desA-

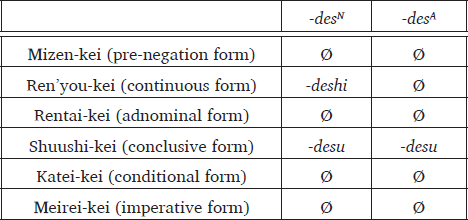

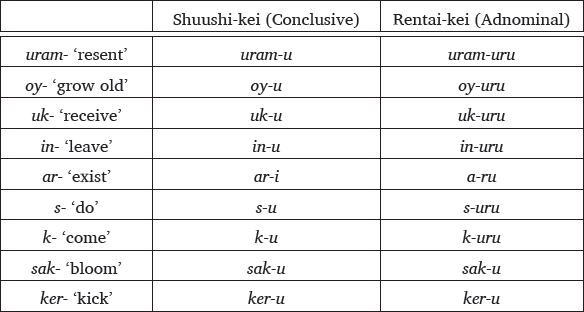

It is not clear exactly how -des- entered the vocabulary of Japanese as there are several hypotheses concerning its origin (Odani 2012). While it was observed as early as in the 17th century, it did not become common among the general population till the early to mid 19th century (Yuzawa 1954). Interestingly, it was almost always with a noun at the beginning, and it started to appear with an adjective in the late 19th century. In Contemporary Japanese, it also is categorized as jodoushi along with -mas-, but its conjugational paradigms are much more impoverished, as illustrated below.

- (29)

- Conjugation Paradigms of -desN- & -desA-

The more impoverished of the two is -desA-, which has only retained the conclusive form. As shown in (17) in Section 2.3, -desA- does not inflect for tense and attaches to an inflected adjective. As a matter of fact, -desA- does not show any morphophonemic variations, and in this sense, it is much more like shuu-joshi a ‘sentence-final particle’. The other version of the UH copula, -desN-, has one additional form, ren’you-kei, the continuous form. It is the form used to combine with the past tense morpheme ta, as in deshi-ta ‘be.uh-past’, and with the gerundive suffix te, as in deshi-te ‘be.uh-gerund’.

As demonstrated in (16) and (17) in Section 2.3, -desN- inflects for tense, just as does its plain counterpart -da. On the other hand, -desA- attaches to an adjective that inflects for tense. Its morphological form is always -desu, and there is no plain/non-honorific version of -desA-. The following sentences exemplify these characteristics.

- (30)

- a.

- Sapporo-wa

- Sapporo-top

- ame-da

- rain-be.plain.-pres

- /

- /

- dat-ta.

- be.plain-past

- ‘It is / was raining in Sapporo’.

- b.

- Sapporo-wa

- Sapporo-top

- ame-des-u

- rain-be.uh-pres

- /

- /

- deshi-ta.

- be.uh-past

- ‘It is / was raining in Sapporo’.

- (31)

- a.

- Sapporo-wa

- Sapporo-top

- samui

- cold.pres

- /

- /

- samuk-atta

- cold-past

- /

- /

- *samui-da

- cold-be-pres

- /

- /

- *samui-datta

- cold-be.uh-past

- ‘It is / was cold in Sapporo.’

- b.

- Sapporo-wa

- Sapporo-top

- samui-desu

- cold.-pres-be.uh

- /

- /

- samuk-atta

- cold-past

- desu

- be.plain.uh

- /

- /

- *samui-deshi-ta

- cold-be.uh-past

- ‘It is / was cold in Sapporo.’

In order to account for the observed patterns, we propose (32).

- (32)

- a.

- -desA- is a morphological realization of the UH features. As such, it is directly inserted to the c0 position.

- b.

- -desN- is a morphological realization of the UH features as well as the information concerning tense. As such, it is inserted to the T0 position, as argued by Yamada (2019, 3.2.3; 2020).

4 Structure – Embeddability Correspondence

4.1 Embedded Utterance Honorifics and Multiple Agree

With the assumption that an UH is licensed via Agree with a c0 with the relevant honorific features, the embedded UH phenomenon can be brought about by either (33a) or (33b).

- (33)

- a.

- Contrary to Portner et al (2019), a cP can be embedded, and an embedded UH is licensed via Agree with the local c0.

- b.

- An embedded UH is licensed via long-distance multiple Agree with the matrix c0. The projection of a cP is mainly limited to a root clause, as in Portner et al (2019).

(33a) is the kind of analysis that we have considered but deemed not feasible. While there are a couple of embedded structures that can host all types of UHs, namely because- and although/but-clauses, the distributional discrepancies among the UH markers cannot be easily accommodated within such an analysis.8 The general scheme of structure–embeddability correspondence that we advocate would be served better by a proposal along the lines of (33b).

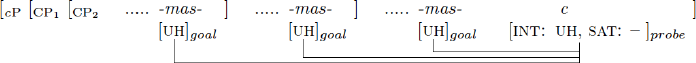

(33b) is motivated by the fact that an embedded UH cannot be licensed when the matrix predicate lacks the comparable UH marking. In other words, an embedded UH is dependent on the matching UH in the matrix. Descriptively speaking, the embedded UH marking is similar to concord phenomena, such as negative concord (Zeijlstra 2004; Giannakidou 2006) and modal concord (Geurts and Huitink 2006; Zeijlstra 2007).9

To incorporate this descriptive idea into our proposal, we assume the schematic structure (34) for the licensing of embedded UHs following the Interaction-Satisfaction model of Agree by Deal (2015; 2021a; 2021b). Under this model of Agree, the probe has two feature specifications which are different from (un)interpretable/(un)valued features: one is [int: ] determining which feature would be the goal for this probe and the other is [sat: ] determining which feature stops the probing operation. Here, we assume that (i) the Phase Impenetrability Condition (Chomsky 2000) does not apply for the long-distance multiple Agree of UH markings, and (ii) c-head is an insatiable probe, whose satisfaction condition is unspecified.

- (34)

Under this configuration (34), the c-head probes the UH features in the structure and interacts with them. Since the feature which halts this probing of UH feature is unspecified, the probing process continues until it exhausts the entire structure. This model nicely explains the examples like (35) noted by Ishii (2020). (35) indicates that an embedded UH is acceptable even when there is an intermediate embedded clause which is not marked for the same UH.

- (35)

- watakushi-wa

- I-top

- [[sensei-ga

- [[teacher-nom

- o-kaeri-ni-nari-mashi-ta

- hon-return-dat-become-uh-past

- koto]-ni

- fact]-dat

- musuko-ga

- my.son-nom

- kizuka-zu-ni

- notice–neg-dat

- i-ta

- exist-past

- koto]-o

- fact]-acc

- zan’nen-ni

- regretful-dat

- omotte-ori-mas-u.

- think-prog-uh-pres

- ‘I regret (polite) that my son didn’t realize (plain) that the professor left (polite).’

The innermost predicate (bold-faced) has the UH -mas-, but the predicate in the intermediate embedded clause (underlined) is in the plain form. This example shows that the lack of UH in the intermediate embedded clause does not disturb the multiple Agree relation between the most embedded UH and the c0. The Interaction-Satisfaction model of Agree can handle this lack of minimality. Under this model, the lack of [uh] feature at the intermediate embedded clause does not stop the long-distance multiple Agree process because of the insatiable c probe.

We are now ready to analyze the embeddability of each of the UH markers. We begin with -desA-, the most restrictive UH marker in terms of embeddability.

4.2 Why -desA- is the least embeddable but not completely unembeddable

Among the three UH markers, we make the most straightforward prediction with -desA-. Its ‘super-high’ syntax as being in the c0 should lead to the distribution comparable to a root phenomenon. The prediction is largely borne out, as it is the most resistant to embedding of the three UH markers. As pointed out earlier, however, there are two embedding environments in which -desA- can appear. One is a because-clause with -kara and the other is an although/but clause with -ga / -ke(re)do. Our analysis leads to the hypothesis that these clauses can embed cPs. In other words, an appearance of -desA- in such a clause is not licensed via a long-distance Agree relation with the matrix cP. It is instead locally licensed by an embedded cP. This conclusion slightly weakens Portner et al’s claim, but we believe that it is possible to justify our hypothesis.

First of all, it is worth reiterating the fact that embedded UHs are typically optional. There seem to be no embedding structures that require UHs in them. In this respect, although/but-clauses are exceptional. Tagashira (1973) notes that with -ga / ke(re)do, the UH form is preferred over the plain form when the matrix clause is also in the polite form.

- (36)

- a.

- Chiisai

- small

- kuni

- country

- ?da

- beplain

- /

- /

- desu

- be.uh

- ga,

- though

- hitobito-wa

- people-top

- yutakana

- rich

- kurashi-o

- life-acc

- shite-i-masu.

- do-prog-uh.-pres

- ‘Though (this) is a small country, people there live in comfort.’

- b.

- Chotto

- a.little

- ?dekakeru

- go.outplain

- /

- /

- dekake-masu

- go.out-uh

- kedo,

- although,

- nanika

- something

- go-iriyou-no

- Honor-necessary-gen

- mono-ga

- thing-nom

- ari-masu-ka?

- exist-uh-q

- ‘I am about to go out now; is there anything I can get for you?’

This fact is consistent with the hypothesis that there is a cP within an although/but-clause. A clause embedded by ga / ke(re)do is a clausal unit whose honorific marking is or can be independently evaluated, and its honorific marking should match with that of the main clause, just as is the case for two consecutive root sentences spoken by one speaker. When they do not, it often causes a kind of stylistic mismatch similar to the observed effect in (36). For instance, the two sentences in (37) sound ‘out of sync’ without UH in the first sentence.

- (37)

- Chotto

- a.little

- #dekakete-kuru

- go.out-comeplain

- /

- /

- dekake-ki-masu.

- go.out-come-uh.

- Nanika

- something

- go-iriyou-no

- Honor-necessary-gen

- mono-ga

- thing-nom

- ari-masu-ka?

- exist-uh-q

- ‘I am about to go out now. Is there anything I can get for you?’

In contrast, kara ‘because’ does not show as clear a contrast as ga / ke(re)do do. In the example below, for instance, it seems that the plain form in the kara-clause causes no observable ill-effects even though the matrix clause has -mas-.

- (38)

- Sensei-mo

- Teacher-also

- o-kaeri-ni

- hon-go.home-dat

- nat-ta

- become-past

- /

- /

- nari-mashi-ta

- become-uh-past

- kara,

- because,

- sorosoro

- about.time

- heikai-to

- adjournment-as

- itashi-masho-u.

- dohumble-uh-Propose

- ‘Now that the professor has gone home, shall we adjourn?’

In this respect, the -kara clause shows a typical UH-embedding structure, in which an embedded UH is merely optional. However, it is possible to detect the independence of UH marking within kara-clauses. The effect surfaces under ellipsis. Consider the following example.

- (39)

- A professor invites a student to dinner. The professor encourages the student to eat more, but the student declines by saying:

- Ie

- No

- ie,

- no,

- mou

- already

- juubun

- enough

- ?itadai-ta

- eathumble-past

- /

- /

- itadaki-mashi-ta

- eathumble-uh-past

- kara.

- because

- ‘No (I respectfully decline your offer) because I have had enough.’

In this example, the embedded verb itadaku is the object-honorific (or humble) from of eat, and in this particular case, it indicates that the speaker (= the grammatical subject) is respectful to the addressee. Without the UH -mas-, however, the sentence does not sound as polite as the context requires. Thus, while the UH marking appears to be merely optional in a -kara clause, it becomes a preferred option when the matrix predicate is missing as a result of ellipsis. This is not a typical pattern with embedded UHs in general. For instance, UHs in temporal adjuncts and -te gerundives are still optional even when the matrix predicates are unexpressed, as illustrated in (40) and (41).

- (40)

- A professor asks ‘Have you met my wife?’, and a student answers;

- Ee,

- Yes,

- senjitsu

- the.other.day

- sensei-no

- teacher-gen

- otaku-ni

- househonor-loc

- o-ukagai

- hon-visit

- shi-ta

- do-past

- /

- /

- shi-mashi-ta

- do-uh-past

- toki-ni.

- time-at

- ‘Yes, when I went to your house the other day.’

- (41)

- A host thanks a distinguished guest for coming;

- Kyou-wa

- Today-top

- o-isogashii-naka

- hon-busy-in.the.middle

- wazawaza

- taking.trouble

- irashite

- comehonor

- itadai-te

- receivehumble-gerund

- /

- /

- itadaki-mashi-te …

- receivehumble-uh-gerund

- ‘(I thank you) for taking trouble to come (to see me) when you are so busy.’

The observed pattern with -kara clauses can be explained as follows. Usually, the presence of a cP is optional within a -kara clause. However, when the matrix predicate is missing due to ellipsis, the speaker is encouraged to use a chance to mark the utterance with an honorific by embedding a cP under -kara. There are no such ‘encourage’ effects with other UH-embedding environments, such as cases like (40) and (41) because the choice of using a cP is not available. Such structures do not allow cPs to be embedded, and the question of embedding cPs does not even arise.

The embeddabilty with because- and although/but-clauses in Japanese presents an interesting cross-linguistic puzzle. Since the lack of inflectional variation of -desA- mimics that of a sentence-final particle, the embedding patterns of -desA- would be expected to be in sync with what we find with the Korean UH markers, which are all sentence-final particles. However, the Korean UH markers are unembeddable even with the comparable because- and although/but-clauses in the language.

- (42)

- a.

- cikap-ul

- wallet-acc

- kkamppakhay-ss-(*sup)-unikka

- forget-past-(*UH)-because

- amwukesto

- anything

- sa-ci

- buy-comp

- mos-hay-ss-supnita/eyo.

- cannot-be-past-uh

- ‘Because I forgot my wallet, I could not buy anything.’

- b.

- cikap-ul

- wallet-acc

- kkamppakhay-ss-(*sup)-ese

- forget-past-(*UH)-because

- amwukesto

- anything

- sa-ci

- buy-comp

- mos-hay-ss-supnita/eyo.

- cannot-be-past-uh

- ‘Because I forgot my wallet, I could not buy anything.’

- (43)

- cikap-ul

- wallet-acc

- kkamppakhay-ss-(*sup)-ciman

- forget-past-(*UH)-but

- hayntuphon-ulo

- phone-Instrumental

- sa-ss-supnita/eyo.

- buy-past-uh

- ‘I forgot my wallet, but I bought things using my phone.’

There are two possible explanations for the cross-linguistic contrast. One hypothesis is that, unlike because- and although/but-clauses in Japanese, their Korean counterparts cannot embed cPs, which implies that embedded clauses under such embedders cannot be independently evaluated for their honorific markings. We must admit, however, that there does not seem to be any empirical evidence either to support or to refute this hypothesis.

Alternatively, we appeal to some morphosyntactic difference between the UH markers in the two languages. The UH markers in Korean are truly sentence-final particles in the sense that no other particles can follow them. In contrast, Japanese has a set of discourse particles, such as -yo, -ne and -na(a) that can be attached to UH-marked predicates.

- (44)

- Kore,

- This

- oishii-desu

- tasty-be.uh

- -yo

- dpart

- /

- /

- -ne

- dpart

- /

- /

- -naa

- dpart

- ‘This is tasty, (I tell you) / (isn’t it?) / (I’m impressed).’

If a sentence includes any one of these particles, it cannot be embedded even with because- and although/but-clauses.

- (45)

- a.

- *Raishuu-wa

- Next.week-top

- isogashii-desu-yo-kara,

- busy-be.uh-dpart-because

- saraishuu-ni

- the.week.after.next-dat

- shite-kudasai

- make-please

- ‘Because I will be busy next week, please make it to the following week.’

- b.

- *Raishuu-wa

- Next.week-top

- isogashii-desu-yo-ga/kedo,

- busy-be.uh-dpart-but/but,

- kanarazu

- certainly

- ai-ni

- see-dat

- iki-masu.

- go-uh

- ‘Although I will be busy next week, I will definitely come see you.’

Extending Davis’ (2009) analysis of the particle -yo, Altinok & Tomioka (2022) argue for the presence of the outermost syntactic projection above Force/Speech Act, which they label Utt (erance)P.10 Altinok & Tomioka (2022) analyze Right Dislocation as an operation involving a movement to an UttP, the outer most periphery in syntax. As briefly touched upon in Section 2, Right Dislocation is strictly a root phenomenon, and its non-embeddability is a consequence of an UttP being not embeddable. Adopting Altinok and Tomioka’s idea, we speculate that Korean sentences with UH markers are not only cPs but also UttPs. In other words, the UH markers are c0 elements, but in the absence of any other particles following the UH markers, a cP is always identified as the largest, outer most projection (i.e., UttP) in Korean. In Japanese, on the other hand, a sentence with an UH marker but without a discourse partible can be a cP. Under this hypothesis, because-clauses and although/but clauses do not have to be dramatically different between Japanese and Korean. The difference is that a ‘bare’ cP is allowed in Japanese but not in Korean. As a consequence, UH markers can be embedded by cP-selecting embedders in Japanese. In Korean, on the other hand, a UH-marked cP always has an additional layer of UttP, and UH markers are banned from embedded structures, just as is the case with discourse particles in Japanese.

4.3 Why the embedding of -desN- is complicated

Recall that we assumed in the previous section that -desN- is inserted at T0 to support the tense feature located there. It created the three way distinction among the UH markers in terms of their syntactic position: -mas- is in the vP-edge region, -desN- in the TP area, and -desA- in the highest position as c0. The differences in their syntactic ‘height’ correspond to their embeddability. The most embeddable is -mas-, -desA- is barely embeddable, and -desN- sits right in the middle.

However, this picture is not workable in a straightforward way. First of all, -mas- also inflects for tense, which indicates that it possibly moves to T0 (see the discussion in the next subsection). If that is the case, -mas- and -desN- are indistinguishable as far as the size of their syntactic constituents. Second, a (finite) TP is embedded in a variety of environments, and if -desN- is at T0 and the constituent size is all that matters for embedding, we would incorrectly predict that -desN- can be embedded rather freely.

It appears that the main difference between -mas- and -desN- comes down to the availability of rentai-kei, the adnominal form. The embedding environments that support -mas- but not -desN- all require the embedded predicates to be in the adnominal form. This descriptive generalization leads to the following theoretical question: What does the availability of the adnominal form mean in the generative syntactic framework? We have suggested that the impoverished conjugational paradigm of -desN- compared to -mas- means that the former is more functional / less lexical than the latter, but such a conjecture does not lead to any concrete solution to the puzzle.

There is another fact that makes the landscape surrounding -desN- even more complicated. Although -desN- in the non-past tense (i.e. -desN-u) cannot be contained within embedded clauses under nominal structures, its past tense counterpart, -deshita, seems more compatible with such structures. While it is perhaps not as clearly acceptable as -mas-, we can definitely construct adequate sentences, as in (46). (46a) involves a koto complement of an attitude verb, (46b) is a relative clause example, and (46c) has -deshita within a temporal adjunct.

- (46)

- a.

- [Kaigi-no

- Meeting-gen

- junbi-ga

- preparation-nom

- fujuubun-deshi-ta]

- inadequate-be.uh-past

- koto-o

- fact-acc

- fukaku

- deeply

- owabi-moushiage-masu.

- apology-sayhumble-uh

- ‘We sincerely apologize for the fact that our preparation for the meeting was inadequate.’

- b.

- ?Sono

- that

- atsumari-ni-wa,

- gathering-at-top

- [Tanaka-sensei-o

- [Tanaka-teacher-acc

- gozonji-deshi-ta]

- knowhonor-uh-past]

- kata-ga

- personhonor-nom

- takusan

- many

- irasshai-mashi-ta.

- be.present-uh-past

- ‘At the gathering, there were many people who knew Professor Tanaka.’

- c.

- [Senjitsu

- the.other.day

- sensei-ga

- teacher-nom

- gobyouki-deshi-ta]

- sickhonor-be.uh-past

- sai-ni

- occasion-at

- omimai-ni

- visithonor-dat

- ukagai-mashi-ta.

- gohumble-uh-past

- ‘When the professor fell sick the other day, I visited her.’

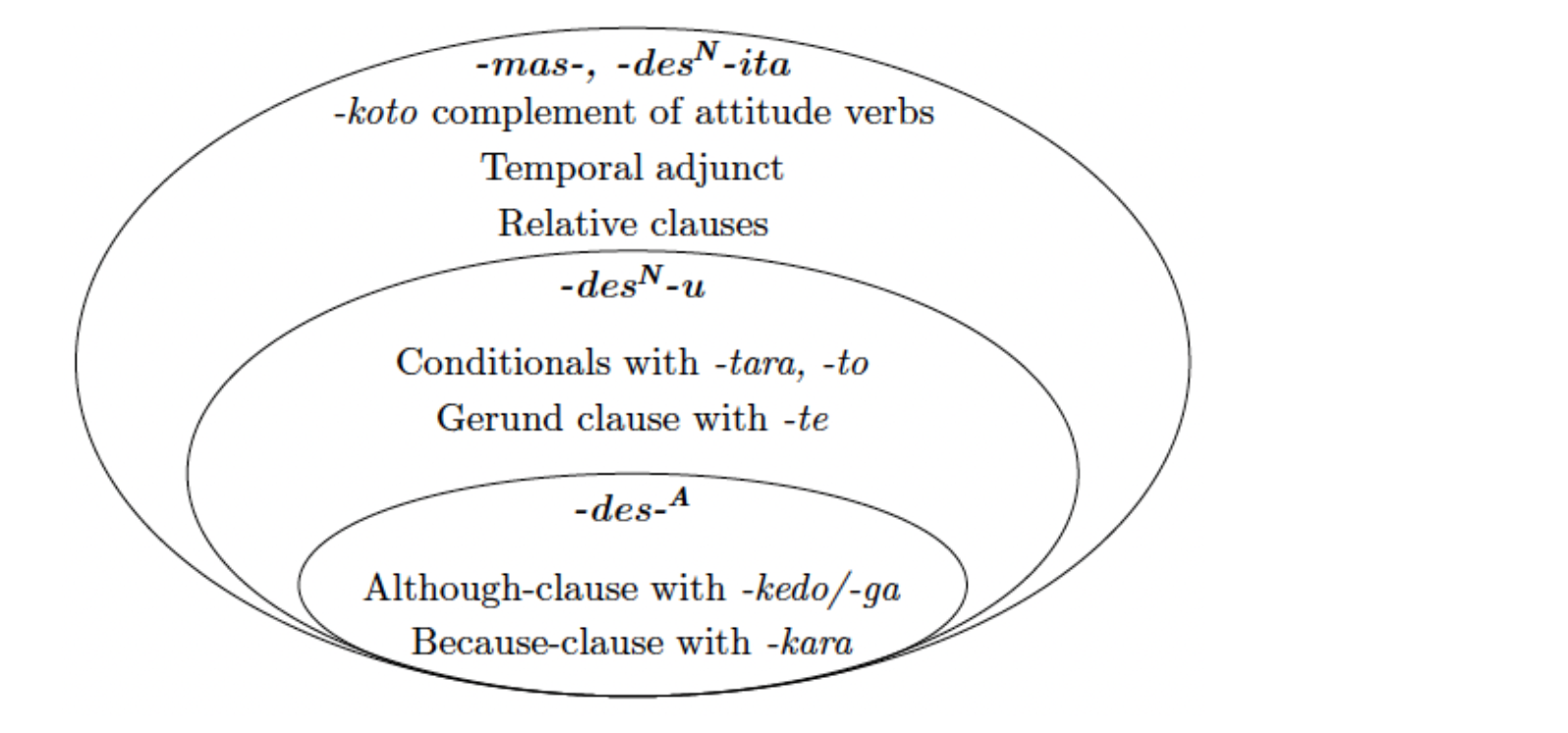

We therefore need to explain not only the contrast between -desN- with the other two UH markers but also the difference between the past and the non-past variants of the same UH marker. As a matter of fact, the past tense of -desN- and -mas- pattern very much alike under embedding, and the previous distributional pattern is now slightly revised.

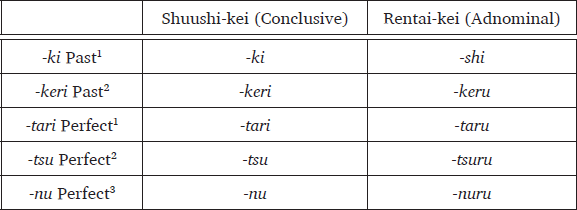

- (47)

The first step is to understand the distinction between the conclusive form and the adnominal form. The two forms are morphologically indistinguishable in verbs and adjectives in Contemporary Japanese. In Classical Japanese, however, the two forms were morphologically distinct for adjectives and certain classes of verbs.11

- (48)

- a.

- Shuushi-kei (Conclusive) & Rentai-kei (Adnominal) of Adjectives in Old Japanese

- b.

- Shuushi-kei (Conclusive) & Rentai-kei (Adnominal) of Verbs in Old Japanese

Even more relevant is the fact that the two past tense morphemes and the three perfect morphemes in Old Japanese all show distinct forms for shuushi-kei and rentai-kei.

- (49)

- Shuushi-kei (Conclusive) & Rentai-kei (Adnominal) of Past Tense and Perfect Morphemes in Old Japanese

Suppose that the conclusive form is the indication that a clause marked with it is a finite clause while the other forms, including the adnominal form, are non-finite. Then, the paradigm above leads to the conclusion that in Old Japanese, being ‘tensed’ and being ‘finite’ were separate notions and were distinct morphological markings because the past tense morphemes have the finite/non-finite contrast. We hypothesize that the distinction has survived and remains relevant in Contemporary Japanese despite the loss of almost all of the morphological differentiations.

This hypothesis is in accordance with the traditional grammatical treatment of the past tense morpheme -ta in Contemporary Japanese. This morpheme, historically derived from the perfect morpheme -tar- in (49), is categorized as a jodoushi, an auxiliary verb, and its conjugational paradigm is believed to include the adnominal form. It takes the form of -ta, which is homophonous to the conclusive form. Hence, -deshi-ta, the past tense of -desN-, is either in the adnominal form or in the conclusive form whereas the non-past counterpart -des-u is unambiguously in the conclusive form.12

The hypothesis is also on the right track when we take a look at nominal adjectives (aka. adjectival nouns / na-adjectives) in Contemporary Japanese. We have stated that Contemporary Japanese has lost almost all distinctions between the adnominal and the conclusive forms. The word almost is added because the distinction between the two forms is still observable with nominal adjectives.

- (50)

- a.

- kono

- this

- ryokan-wa

- inn-top

- teien-ga

- garden-nom

- yuumei-da

- famous-beconclusive

- /

- /

- *-na

- -beadnominal

- ‘Lit. Speaking of this inn, its garden is famous.’

- b.

- [teien-ga

- teien-nom

- yuumei-na]

- famous-beadnominal

- ryokan-ni

- inn-loc

- iki-tai

- go-want

- ‘(I) want to go to an inn which is famous for its garden.’

(50a) shows that a nominal adjective yuumei ‘famous’ requires a be-support at the end of a sentence, and not surprisingly, the copula must be in shuushi-kei, the conclusive form. In (50b), on the other hand, -na, the adnominal form of -da, appears between yuumei ‘famous’ and the following NP ryokan. Notice that the adnominal clause in (50b) can host a nominative case marked argument. This indicates that there should be at least a TP projection (see Takezawa 1987). Moreover, the semantic interpretation of -na is identical to the typical non-past interpretation. Since -na can never replace -da in a root finite clause, we can conclude that a -na–clause is a TP that is capable of licensing a nominative case but is nonetheless non-finite.

By separating the notion of ‘tensed’ from that of ‘finiteness’, we allow a combination that is often regarded as non-existent, namely a tensed non-finite clause, and we argue that a predicate in the adnominal form is precisely that. Furthermore, we can translate the contrast between the adnominal and the conclusive forms into a matter of syntactic size. In the Cartographic Syntax of Rizzi (1997; 2004), there is a separate functional projection FinP immediately above a TP. Thus, the following hypothesis presents itself:

- (51)

- A clause in the adnominal form is a TP whereas a clause in the conclusive form is a FinP.

The idea that a relative clause in Japanese is a TP is not new. Saito (1985) and Murasugi (1991) argue that a relative clause in Japanese does not involve an operator movement, and that, as a consequence, the projection of a CP is not necessary. Miyamoto (2014) adopts the TP-hypothesis to analyze the differences between Chinese and Japanese relative clauses. Given that a temporal adjunct clause, such as toki ‘(the time) when’, is structurally identical to a relative clause, the TP hypothesis also applies to such a clause. As a koto clause clearly lacks an operator movement for its formation, it can also be regarded as a TP.

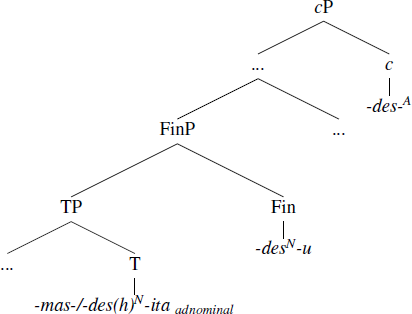

The hypothesis expressed in (51) makes the embedability paradigm of the Japanese UH markers a consequence of the syntactic size of an embedded clause. The tree diagram below illustrates the structural positions of the UH markers. As discussed earlier, -mas- is generated at the vP edge and possibly moves to T0. Importantly, -mas- has the adnominal form, mas-u, the same as the conclusive form (the table in (27)), and when it is in that form, it stays within a TP. In this regard, its structural position is the same as that of deshi-ta, the past tense of -desN.

- (52)

The discussion in the previous subsection concludes that ga/ke(re)do clauses and kara clauses can embed cPs, and -desA- can therefore appear in those embedded environments. According to the hypothesis (51), embedded clauses in the adnominal form are TPs. The remaining UH-embedding environments are at least as large as FinPs but not large enough to be cPs. For convenience, we label them as FinPs below. The structure–embeddability correspondence is shown below.

- (53)

While the analysis spelled out above captures all the distributional patterns of the UH markers in purely structural terms, we acknowledge that other approaches are also possible. First of all, it should be noted that the proponents of the TP-analysis of Japanese relative clauses contrast TP with the traditional definition of CP, rather than the articulated CP structure in the Cartographic Syntax. Thus, their arguments based on the presence vs. absence of a relative-operator movement are largely irrelevant to the TP–FinP distinction. In other words, it is conceivable to reanalyze the adnominal form as in (54).

- (54)

- A clause in the adnominal form is a FinP [-finite] or a FinP [Ø] if finiteness is a privative feature.

With (54), the structure–embedability correspondence is only partially responsible for the embedding patterns of the UHs. The syntactic position of -desA- is still relevant as its high syntactic position leads to the most restricted distribution. On the other hand, the remaining contrast is not a matter of structural size but rather a matter of feature (mis)match. An adnominal-embedding structure requires the embedded clause to be marked with [-finite] (or not to be marked with [+finite]). Since -desN-u, the conclusive form of -desN-, is the manifestation of [+finite], it cannot be embedded under such a structure. While the second possibility requires an additional ingredient to augment the structure–embedability correspondence, the crucial factors remain within the morphosyntax of the UH markers.

4.4 Why -mas- is most embeddable but not freely embeddable

In the previous subsection, -mas- and -deshi-ta are bundled together in the discussion since the two UHs show the same embedding patterns. As mentioned in Section 3.2, -mas- has the adnominal form (i.e., -mas-u), and it is correctly predicted that this UH can appear in an adnominal-selecting embedding clause, regardless of the tense morphology. Recall, however, that there are cases in which -mas- cannot be embedded. In Section 2.2, we identify nagara / tsutsu ‘while/during’ and ren’you-kei (the continuous form) conjunction as such embedding structures. These embedding contexts, which are classified as the smallest embedding units by Mimami (1974) (Type A in his terminology), share two properties: (i) they indicate that the embedded event continuously progresses along with the matrix event and (ii) nagara / tsutsu attach to a verb in ren’you-kei, the continuous form, which is the same form of the conjunctive structure. In this subsection, we address the question of why -mas- cannot be embedded under these embedding markers.

First of all, it is important to be reminded that -mas- does have ren’you-kei, the continuous form (see the table in (27) in Section 3.2). Therefore, the absence of the form cannot be the reason for the unembeddability in nagara / tsutsu clauses and ren’you-kei conjunction. One popular view of the continuous form among Japanese linguists (e.g., Takumi 2008; Mihara 2015; Nishiyama 2016) is that it is the smallest inflectional form in the Japanese verbal conjugational paradigm. Mihara (2015), for instance, argues that it roughly corresponds to a vP. If nagara / tsutsu indeed selects a vP, (55) can explain why -mas- cannot be embedded by them.

- (55)

- -mas- moves out of a vP and to a higher functional head at Spell Out.

It is probably not controversial to suppose that -mas- moves to T0 when it inflects for tense. As discussed extensively by Yamada (2019, 3.3.4), however, T0 may not always be the final destination for -mas-. When combined with the negative morpheme -en, -mas- is not compatible with the past tense morpheme -ta, and a copula must be inserted to support the past tense marker. The interaction between -mas- and negation is an important reason for Yamada’s analysis that -mas- is in the Neg0 position. The statement in (55) leaves the exact Spell-Out location of -mas- rather vague, but it does its job in explaining why the most embeddable UH marker is still not freely embeddable. Given the theoretical assumption that a clause in the continuous form is a vP, it is predicted that -mas- cannot be embedded under nagara / tsutsu.

It should be noted, however, that some instances of -mashi-, the ren’you-kei form of -mas-, are found in embedded structures. The gerundive conjunction and the -tara conditional are among such cases.

- (56)

- a.

- Senjitsu

- the.other.day

- Ginza-ni

- Ginza-loc

- iki-mashi-te,

- go-uh-gerund,

- sokode

- there

- guuzen

- by.chance

- Suzuki-san-ni

- Suzuki-Mr.-dat

- o-ai-shi-mashi-ta.

- hon-meet-do-uh-past

- ‘The other day, I went to Ginza and ran into Mr. Suzuki there.’

- b.

- Go-kaifuku-nasai-mashi-tara

- hon-recover-do.hon-uh-cond

- zehi

- definitely

- mata

- again

- o-koshi-kudasai

- hon-come-please

- ‘Please do come back when you have made a recovery.’

In these examples, -mashi- is followed by a suffix, -te or -tara, whereas nagara and tsutsu select a ‘bare’ ren’you-kei verb without any additional suffix attached to it. Both the conditional marker -tara and the conjunctive -te are morphologically related to the past tense -ta.13 It is therefore natural to assume that these embedding structures are not ‘bare’ vPs but rather some functional projections that can accommodate -mas-.

In summary, -mas- can be embedded by any embedder that selects a TP or larger. However, it cannot appear in a subordinate clause that is a vP since -mas- occupies a position higher than a vP at Spell Out. The second part is an extended part of the structure–embeddability correspondence. Although these embedded clauses that are vPs were not included in the proper subset-superset scheme, structural size matters for them as well: they are too small even for the most embeddable UH -mas-.

4.5 Summary

The discussion of this section is summarized as follows. We have put the structure–embeddability correspondence to test to see whether and how it can account for the distributional patterns of the UH markers. Our examination reveals that it can, at least partially, explain the embedding facts. The adjectival copula -desA- presents the clearest case in favor of the correspondence. It is generated at c0 and is only embeddable under a clause that can exceptionally host a cP, which is primarily found at the root level. Some because- and although/but-clauses are such exceptional cP-hosting clauses. The nominal copula -desN- is the most challenging because its embedding possibilities are sensitive to the tense marking. The past tense, -deshi-ta, is more embeddable than the non-past counterpart, -des-u, and its embeddability matches that of the verbal UH marker -mas-. The difference boils down to the question of whether rentai-kei, the adnominal form, of a given UH marker is defined, as the most restrictive embedding environments require the embedded predicates to be in the adnominal form. Potentially, the structure–embeddability correspondence is all that we need to deal with -desN– and -mas-, but the success of such an analysis depends on a specific analysis of the adnominal form and the conclusive form. If the two forms lead to different sizes in syntax, no ingredients other than the structure–embeddability correspondence are necessary. If the difference between the two forms is a matter of the [± finite] feature, on the other hand, the structure–embeddability correspondence cannot be the whole story and must be augmented with the selection process based on the [± finite] feature. While the choice between the two possible approaches is left as an open question for future research, the indeterminacy on this matter does not affect the overall conclusion that the embeddability variation of the Japanese UHs is determined by the morphosyntactic characteristics of the UH markers.

5 Further Issues

5.1 On Honorific Concord

Based on the fact that the embedded UHs are always licensed by the UH marking in the matrix clause, we hypothesize, as briefly mentioned in Section 4.1, that the embedded UH marking in Japanese is a kind of concord phenomenon. One consequence of analogizing the embedded UH marking to a concord phenomenon is that embedded UHs do not make their own semantic contributions. For instance, a negative concord item has no negation meaning of its own. If it did, its presence would reverse the truth condition of the sentence where it appears.

This perspective seemingly contradicts Yamada’s (2019) observation that the embedded UH marking has an enhancement effect. In the example below, the embedded verb can be either with or without the UH marker -mas-, and the presence of -mas- arguably increases the level of politeness for the whole utterance.

- (57)

- Hayaku

- Quickly

- go-kaifuku-nasaru

- hon-recover–do.hon

- /

- /

- nasai-masu

- do.hon-uh

- koto-o

- fact-acc

- o-inori-shite-ori-masu.

- hon-pray-do-be.humble-uh

- ‘I pray for your speedy recovery.’

While we agree with Yamada’s assessment of some specific cases, the generalization does not seem to us as clear as described by Yamada. First of all, the presence of an embedded UH does not compensate for the understated level of politeness at the matrix level.

- (58)

- ??Hayaku

- Quickly

- go-kaifuku-nasai-masu

- hon-recover-do.hon-uh

- koto-o

- fact-acc

- inot-te-i-masu.

- pray-gerund-be-uh

- ‘I pray for your speedy recovery.’

Unlike (57), this example has an understated honorific marking at the matrix level. It contains only the UH marker -mas- without any content-related honorifics such as the object-honorific o-inori-suru ‘prayhumble’. In this example, the presence of -mas- in the embedded clause does not seem to generate the expected enhancement effect. As a matter of fact, (58) sounds rather odd, and the oddity is due to the politeness level of the matrix predicate being not sufficiently high. In general, an embedded UH, especially one that is embedded under a nominal structure like (57)/(58), should be accompanied by a very high level of honorific marking at the matrix level. If this stylistic requirement is generally operative, the raised honorific marking in the matrix clause, which typically accompanies an embedded UH, may be the main source of the elevated level of politeness.

The uncertainty of enhancement effects is also highlighted by the multiple occurrences of embedded UHs, as in (59).

- (59)

- Sensei-ga

- Teacher-nom

- o-kaki-ni

- Honor-write-dat

- nat-ta

- become-past

- /

- /

- nari-mashi-ta

- become-uh-past

- go-hon-ga

- Honor-book-nom

- shuppan-no

- publish-gen

- hakobi-ni

- plan-dat

- nat-ta

- become-past

- /

- /

- nari-mashi-ta-koto-no

- become-uh-past-fact-gen

- kinen-ni,

- commemoration-dat,

- oiwai-no

- celebration-gen

- kai-o

- party-acc

- hiraki-taku

- hold-want

- zonji-masu.

- think-uh

- ‘For the commemoration of the occasion that the book that the professor wrote will now be published, we would like to host a celebration.’

In this example, the speaker can choose to use the honorific marking for both of the embedded verbs, either one of them, or neither of them. If an embedded UH is computed cumulatively, it would be expected that the level of the politeness increases in the order of ‘neither < either < both’. Our intuition is far from clear, as it is not easy to detect a difference among those possible combinations.

If there is some effect of increased politeness with an embedded UH, it may also be derived conversationally. First of all, the UH marking in an embedded clause is not obligatory, and the speaker can choose not to use UH marking for the embedded clause without sacrificing the overall politeness effect as long as the matrix predicate is appropriately honorified. When the speaker has nonetheless chosen to use UH for the embedded clause, there must be a reason for that choice. One reasonable hypothesis is to emphasize the politeness, which leads to the increased level of politeness. The increased level of politeness via Gricean reasoning of this kind is compatible with the concord hypothesis since it is possible to maintain the idea that an embedded UH is devoid of conventional contribution. The inconsistency of added politeness effect of embedded UHs suggests that the addressee does not necessarily interpret an embedded UH as a sign of emphasizing politeness. Another potential reason is to indicate utterance-level politeness in the early stage of speech. Given the fact that Japanese is a head-final language, the crucial UH marking comes last. Since a sentence with an embedded clause can be long, the speaker may choose not to wait till the end to indicate their respect to the addressee and use an UH on the embedded clause, which the Japanese Grammar allows via multiple Agree.

In addition to the pragmatic effect of embedded UHs, we acknowledge that there are a few syntactic issues in connection to the idea of the honorific concord. One problem is that the concord system we are proposing is made possible via a long-distance Agree relation between an embedded UH and the c0. This idea goes against the typical understanding that an Agree relation is regulated by a locality condition, such as the Phase Impenetrability Condition of Chomsky (2000). A potential solution is to assume that the multiple Agree mechanism for the Japanese honorific concord occurs locally at every FinP level. A UH-related feature in c0 reaches to an UH-marker via the presence of a Fin0. An embedding UH is licensed via Agree with its local Fin0, which itself is in an Agree relationship with the matrix F0 and c0. In other words, an embedded Fin0 acts as a kind of conduit that passes a UH feature over to its local domain.14 One important consequence is that this account requires the weaker version of the structure–embeddability correspondence, in which a clause in the adnominal form is not a TP but a non-finite FinP.

The second issue is the direction of Agree. Under Deal’s (2015; 2021a; 2021b) model of Agree, concord items can be licensed via downward Agree, which is widely assumed in the literature. On the other hand, Zeijlstra (2008) and his subsequent work (e.g., Miyagawa et al. 2016) argue for an upward Agree operation to account for a negative concord phenomenon in Dutch. Though we followed Deal’s model in this paper, we should note that both analyses are compatible with the embedded UHs in Japanese. Thus, further research is necessary for the problem of the direction of Agree, and the future research on the UH embedding phenomena may provide an interesting discussion for this problem.

5.2 Complement Clauses of Attitude Verbs

Another puzzle of embedding UHs is a complement clause of attitude verbs with -to. At the onset of the paper, we mentioned that a complement clause with the complmentizer -to can embed UHs if the embedded clauses are direct quotations. So far we have said nothing of non-quotative attitude complements, and they are rather problematic. Though complements of attitude predicates are often more permissive of main clause phenomena than some of the other embedding environments, such as conditionals or relative clauses, none of the UH markers can be embedded within a complement clause with -to.15 (60a), (60b) and (60c) below show the embedding of -mas-, -desN- and -desA-, respectively.

- (60)

- a.

- [Hayaku

- quickly

- go-kaifuku

- hon-recovery

- nasa-ru

- do.hon

- /

- /

- *nasai-masu]

- do.hon-uh

- to

- comp

- shinjite-ori-masu.

- believe-do-behumble-uh

- ‘I pray for your quick recovery.’

- b.

- [kaigi-wa

- meeting-top

- raishuu-no-suiyoubi-da

- next.week-gen-Wednesday-be

- /

- /

- *-desu]

- be.uh

- to,

- C

- zonjite-ori-masu.

- know-behumble-uh

- ‘I know that the meeting will be held on Wednesday next week.’

- c.

- [senshuu-wa

- last.week-top

- o-isogashi-katta-Ø

- hon-busy-past-Ø

- /

- /

- *-desu]

- -uh

- to,

- C

- ukagatte-ori-masu.

- hearhumble-behumble-uh

- ‘I heard that you were busy last week.’

The restriction is only on the predicate to which to attaches, and as long as the to-adjacent predicate is in the plain form, the complement clause itself can contain an UH, as shown below.

- (61)

- Watakushi-wa

- Iformal-top

- [sensei-ga

- [teacher-nom

- o-kaki-ni

- Honor-write-dat

- nari-mashi-ta

- become-uh-past

- go-hon-o

- Honor-book-acc

- zehi

- definitely

- yom-ase-te

- read-Cause-gerund

- itadaki-tai-(*desu)-to]

- receivehumble-want-(be.uh)-comp]

- omot-te-ori-masu.

- think-gerund-behumble-uh

- (Talking to a professor) ‘I think that I would definitely like to read the book you have written.’

As briefly touched upon in section 6.1, the lack of minimality effect may be solved by assuming that the plain form does not have any relevant honorific features so that it can be ‘skipped over’ in establishing an Agree relation. However, it remains unresolved why the to-adjacent predicate is the only one that must remain in the plain form within an attitude complement.

An interrogative complement of an attitude verb largely patterns with a -to complement clause.

- (62)

- a.

- *[Ashita

- tomorrow

- doko-ni

- where-dat

- mairi-masu-ka]

- gohumble-uh-q

- narubeku

- as.possible

- hayaku

- early

- o-tsutae-itashi-masu

- Honor-inform-do.humble-uh

- ‘I will inform you as soon as possible where (I) will go tomorrow.’

- b.

- *Watashi-wa

- I-top

- [Ken-ga

- Ken-nom

- nansai-desu-ka]

- what.age-Cop.uh-q

- tazune-mashi-ta

- ask-try-uh-past

- ‘I asked how old Ken is.’

- c.

- *Watashi-ga

- I-top

- buchoo-ni

- boss-dat

- [konshuu

- this.week

- o-isogashii-desu-ka(dooka)]

- hon-busy-uh-q

- kakuninshi-mashi-ta

- check-uh-past

- ‘It is I that checked with my boss whether he is busy this week.’

Adjacency is critical with interrogative clauses as well. Only the predicate adjacent to the Q-particle -ka must be in the plain form. The clause itself can contain a phrase that has an UH.

- (63)

- Sensei-ga

- Teacher-nom

- o-kaki-ni

- Honor-write-dat

- nari-mashi-ta

- become-uh-past

- go-hon-ga

- Honor-book-nom

- itsu

- when

- shuppan

- publish

- sare-ru

- do.Pass-pres

- (*sare-masu)

- (do.Pass-uh)

- ka,

- q

- gozonji-no

- knowinghonor-gen

- kara-wa

- person-top

- irasshai-masu-ka?

- existhonor-uh-q

- ‘Is there anyone who knows when the book the professor wrote will be published?’

Interestingly, however, embedded interrogative clauses seem more amenable in terms of embedding UHs. When the clause becomes a locus of negation, for instance, the judgment improves.

- (64)

- a.

- ?[Watakushidomo-ni

- wehumble-dat

- o-kotae-deki-masu-kadooka]

- hon-answer-can-uh-whether

- wakari-mase-n-ga…

- know-uh–neg-but

- ‘(Though) we are not sure whether we can answer your question.’

- b.

- [Musuko-ga

- son-nom

- doko-de

- where-at

- nani-o

- what-acc

- shite-ori-masu-ka]-wa,

- do-behumble-uh-q-top

- watashitachi-ni-mo

- we-dat-even

- wakar-anai-node-gozai-masu

- know–neg-because-behumble-uh

- ‘We ourselves aren’t sure what our son is doing where.’

We acknowledge that attitude complements present an intriguing puzzle to which we are not prepared to give even an speculative answer.

6 Conclusion

Since UHs express the speaker’s attitude towards the addressee/audience in all languages where the UH system is found, it is rather puzzling why there are cross-linguistic variations in terms of their embeddability. We address this issue by examining the embedding patterns of the three UH markers in Japanese. While their semantic/pragmatic import is the same, they show vastly different distributional properties under embedding. Moreover, the variability has an ‘implicational’ pattern in which the embedding becomes progressively more restricted in the order of (i) -mas-/deshiN-ta (the past tense of -desN-), (ii) desN-u (the non-past tense of -desN-), and (iii) -desA-. We have identified the root of the variation in the morphosyntactic attributes of those UH markers. Due to their categorical and inflectional differences, they are placed at different locations in syntax, and we have explored the hypothesis that their syntactic height corresponds to the degree of embeddability. The higher the UH marker is, the less embeddable it becomes, and we have attempted to theorize this correspondence.