1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

In this paper we provide a semantic analysis of the determiner system in Nata (Eastern Bantu), and we compare Nata’s determiner system with the strikingly similar determiner system of St’át’imcets (a.k.a. Lillooet; Salish). Our core proposal is that determiners in both these languages reflect whether the speaker is committing themselves to the claim that the noun phrase’s referent exists. The determiner systems of the two languages are not quite identical, however. We show that Nata and St’át’imcets differ in whether the determiners that require the speaker’s existential commitment also carry an evidential requirement that the speaker has personally witnessed the referent(s). This work contributes to the landscape of potential determiner meanings across languages, by showing that speaker commitment to existence is a robust and recurring semantic distinction for determiners, and that the precise properties of existence determiners can vary cross-linguistically depending on other features of the languages.

In the remainder of the introduction, we provide background on the languages of study and our methodology. In section 2, we introduce determiners in Nata, including their basic syntactic properties and the polarity sensitivity of one determiner. In section 3 we repeat this process for St’át’imcets. In section 4, we argue that determiners in both languages encode neither definiteness nor specificity, but instead distinguish whether the speaker commits to the existence of a referent for the DP. We provide a basic analysis of this distinction in both languages, relying on choice functions for the existence determiners, and a low-scoping existential quantifier that is restricted to non-veridical environments for the non-existence-related determiners. Section 5 addresses the empirical differences between Nata and St’át’imcets Ds. Section 6 presents our analysis of both languages. Finally, section 7 expands the landscape to Bantu more broadly, and concludes with an outlook for future research.

1.2 Languages and methodology

Nata is an Eastern Bantu language (E45)1 spoken in northwest Tanzania. It currently has around 7,000 speakers, but the numbers are rapidly decreasing. It is classified as being at endangerment level 6b (‘threatened’) by Ethnologue (www.ethnologue.com/language/ntk).

St’át’imcets (also known as Lillooet) is a Salish language, from the Northern Interior branch. It is spoken in British Columbia, Canada. It has a very small number of first-language speakers at this time. There are active community efforts to retain and revitalize the language.

Our Nata data come from native-speaker intuitions of the first author, and from fieldwork conducted by the first author in Tanzania. Our St’át’imcets data come from fieldwork by the second author and by Henry Davis. Data collection in both languages employed face-to-face elicitations and standard semantic fieldwork methodologies (Matthewson 2004). Most of the elicitation tasks involve setting up a relevant context of use, and sometimes we used visual aids such as pictures and storyboards (see Bruening 2008; Burton & Matthewson 2015).

2 Determiners in Nata

2.1 Introduction to the augment/D

Like many other Bantu languages, Nata has a noun-class system and an element called the augment (a.k.a the ‘pre-prefix’). The augment is the leftmost element of the nominal domain. When it appears, it precedes the noun-class prefix, as shown in (1).

- (1)

- a.

- e=ɣí-taβo

- aug=c7-book

- ‘a/the book’

- b.

- ɣí-taβo

- c7-book

- ‘a/any book’

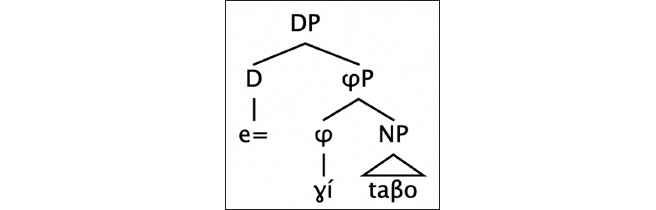

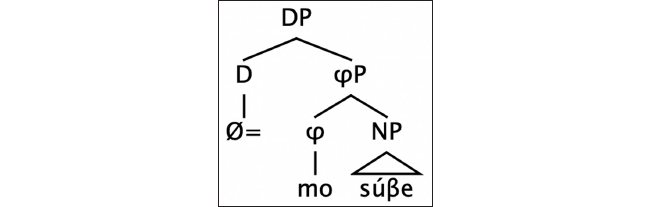

We assume the standard hypothesis that nominal arguments are DPs (Stowell 1989; Longobardi 1994; 2001; 2008), and we further assume that the Bantu augment instantiates the category of D(eterminer), as shown in Figure 1 for the phrase in (1)a. (The class prefix is analyzed as the head of φP, although this is not crucial for current concerns; see Déchaine & Wiltschko 2002.) On the correlation between augments and D, see e.g., Visser (2008), de Dreu (2008), Taraldsen (2010), Gambarage (2012; 2013; 2019), Carstens & Mletshe (2016).

A core intriguing fact about noun phrases in Bantu languages is that the augment/D can either be present or missing on argument DPs. This is illustrated in (2)a,b:

- (2)

- a.

- Masato

- Masato

- ta-a-ɣor-iré

- neg-pst-buy-pfv

- e=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Masato didn’t buy a/the book.’

- b.

- Masato

- Masato

- ta-a-ɣor-iré

- neg-pst -buy-pfv

- __ ɣí-taβo.

- __c7-book

- ‘Masato didn’t buy any book.’

Consistent with the assumption that nominal arguments are DPs, we claim that nominal arguments all contain determiners, but vary according to whether the D is pronounced (overt) or unpronounced (covert). The conditions under which the D is overt vs. covert, and by extension the semantic contribution of the overt vs. missing/covert D, have been a matter of extensive debate in the Bantu literature. It has been noticed by many that arguments without an overt augment are subject to licensing restrictions, and as such are not freely available in all sentence types. This has led some authors to claim that DPs without overt augments are negative polarity items (e.g., Progovac 1993, for Kinande; Hyman & Katamba 1993, for Luganda; Adams 2010, for Zulu). Another fairly common proposal is that the augment system encodes (non)specificity or (non)referentiality (Bokamba 1971, for Dzamba; Givón 1970; 1978, for Bemba; Visser 2008, for Xhosa; Allen 2014, for Runyankore-Rukiga). Alternatively, it has been argued that the augment system encodes (in)definiteness (Mould 1974, for Luganda; Bokamba 1971, for Dzamba). Other lines of thought involve information-structural notions: DPs without overt augments are licensed by a focus operator (Carstens & Mletshe 2016, for Xhosa and Zulu; Hyman & Katamba 1993, for Luganda), or overt augments are used when the noun phrase functions as a topic (Petzell 2003, for Lugulu). Finally, Halpert (2012; 2015) argues that in Zulu, the augment encodes a kind of Case. Although Halpert’s focus is on the syntax rather than the semantics, there is an interesting possible connection to our findings, since cross-linguistically there is often a link between Case marking and semantics, including notions such as specificity or definiteness (e.g., Enç 1991, among many others).

Our analysis of the Nata data differs from all these previous analyses; we will claim that the Nata augment system encodes whether the speaker believes that the referent of the DP exists. Before we turn to the semantics of the augment, we establish in the next sub-section that arguments which lack an overt augment contain a covert augment/D, and that only predicate nominals lack a D.

2.2 Arguments without overt Ds contain a covert D

When there is no overt augment in an argument nominal, we assume there is a covert (phonologically null) D. This is shown in Figure 2 for the DP Ø=mo-súβe ‘a man’.

The evidence for covert D in argument nominals comes from a contrast between argument and predicate nominals. As illustrated in (3), predicate nominals in Nata always lack a D. The discourse context here ensures that mo-súβe ‘a man’ is functioning as a predicate.

- (3)

- [What gender is Masato?]

- a.

- Masato

- Masato

- m=mo-súβe.2

- cop=c1-man

- ‘Masato is a man.’

- b.

- #Masato

- Masato

- n=o=mo-súβe.

- cop-det=c1-man

In contrast, argument nominals always allow overt D, and in affirmative declarative sentences they even require it, as illustrated in (4). Although (3) and (4) both contain copular verbs, the context in (4) is an equational one in which the nominal functions as an argument, and here, unlike in (3), the overt D is obligatory.

- (4)

- [Out of the two people standing here, which one is Masato?]

- a.

- Masato

- Masato

- n=o=mo-súβe.

- cop=det=c1-man

- ‘Masato is the man.’

- b.

- #Masato

- Masato

- m=mo-súβe.

- cop=c1-man

This pattern, whereby Ds are absent on predicative NPs and present on argumental DPs, follows straightforwardly from the widespread assumption that NPs are of predicative type (type <e,t>) and that D functions to create a phrase of argumental type (e.g., type e). We therefore adopt this hypothesis for Nata. See for example Stowell (1989); Longobardi (1994; 2001; 2008), among many others.3

Now, having provided evidence for the claim that the overt D in Nata functions to turn predicative NPs into argumental DPs, what are we to make of argumental contexts where overt Ds are optional, as in (2) above, repeated here with the covert D represented as Ø?

- (5)

- a.

- Masato

- Masato

- ta-a-ɣor-iré

- neg-pst-buy-pfv

- e=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Masato didn’t buy a/the book.’

- b.

- Masato

- Masato

- ta-a-ɣor-iré

- neg-pst-buy-pfv

- Ø=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Masato didn’t buy any book.’

The most obvious assumption is that arguments without overt Ds, as in (5)b, contain a phonologically null D which does its job of creating an argumental type. From this it follows that there is a structural difference between predicative nominals as in (3)a – which lack a D – and argumental nominals as in (5)b – which contain a D – in spite of their surface identity. These claims are summarized in Table 1.4

Correlations between argumenthood and Ds in Nata.

| Sentence | Nata phrase | D? | Predicate / argument | Semantic type | Syntactic category |

| (What gender is Masato?…) Masato is a man. |

mo-suβe c1-man ‘a man’ |

no | predicate | <e,t> | NP |

| (Out of the two people standing here, which one is Masato?…) Masato is the man. |

o=mo-suβe det=c1=man ‘the man’ |

yes, overt | argument | e | DP |

| Masato didn’t buy any book. | Ø=ɣí-taβo det=c7-book ‘any book’ |

yes, covert | argument | <<e,t>,t> | DP |

The rest of this paper is devoted to analyzing the semantic difference between the overt and covert Nata Ds, and in comparing them to the determiner system of an unrelated language, St’át’imcets. We begin our semantic investigation in the next section by introducing a core fact about DPs containing a covert D in Nata: their need for a licensor.

2.3 Covert D requires a higher operator

In this section we show that the Nata covert D is polarity sensitive, in the following sense: it is only licensed when there is a higher operator such as negation, a modal, a conditional operator, or a question marker.

The first relevant fact is that in affirmative declarative sentences, an overt D is required on all nominal arguments. This was already illustrated above for an equational copular sentence in (4); in (6) we see it confirmed for the object argument of an ordinary transitive clause, and in (7) for a subject argument.

- (6)

- a.

- Masato

- Masato

- a-ka-ɣór-a

- sa1-pst-buy-fv

- e=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Masato bought a/the book.’

- b.

- *Masato

- Masato

- a-ka-ɣór-a

- sa1-pst-buy-fv

- Ø=ɣí-taβo.

- det=C7-book

- Intended: ‘Masato bought a book.’

- (7)

- a.

- E=ɣí-taβo

- det=c7-book

- ɣi-kaɣw-a

- sa1-pst-fall-fv

- ha-asé.

- C16-down

- ‘A/the book fell down.’

- b.

- *Ø=ɣi-taβo

- det=c7-book

- ɣi-kaɣw-a

- sa1-pst-fall-fv

- ha-asé.

- C16-down

- Intended: ‘A book fell down.’

The covert D becomes possible when the sentence contains negation, as shown in (8) (see also (5)), a modal (9), the question operator (10), or the conditional operator (11).5

- (8)

- a.

- O=mu-kari

- det=c1-woman

- ta-seegh-ire

- neg-like-pfv

- Yohana.

- Yohaná

- ‘The woman doesn’t like John.’

- b.

- Ø=mu-kari

- det=c1-woman

- ta-seegh-ire

- neg-like-pfv

- Yohana.

- Yohaná

- ‘No woman likes John.’ negation

- (9)

- a.

- Hamwe

- maybe

- Masato

- Masato

- a-ka-ɣór-a

- sa1-pst-buy-fv

- e=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Maybe Masato bought a/the book.’

- b.

- Hamwe

- maybe

- Masato

- Masato

- a-ka-ɣór-a

- sa1-pst-buy-fv

- Ø=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Maybe Masato bought a book.’ modal

- (10)

- a.

- Ango

- q

- u=mw-ána

- det=c1-child

- a-ka-rɔŕ-a

- 3s-pst-see-fv

- María?

- Mary

- ‘Did the child see Mary?’

- b.

- Ango

- q

- Ø=mw-áana

- det=c1-child

- a-ka-rɔŕ-a

- 3s-pst-see-fv

- María?

- Mary

- ‘Did any child see Mary?’ question

- (11)

- a.

- Masato

- Masato

- a-a-ŋga-ɣor-iré

- sa1-pst-cond-buy-pfv

- e=ɣí-taβo

- det=c7-book

- ɲ-a-ŋga-tʃɔmiir-u.

- 1sg-pst-cond-be.happy-fv

- ‘If Masato bought a/the book, I would be happy.’

- b.

- Masato

- Masato

- a-a-ŋga-ɣor-iré

- sa1-pst-cond-buy-pfv

- Ø=ɣí-taβo

- det=c7-book

- ɲ-a-ŋga-tʃɔmir-u.

- 1sg-pst-cond-be.happy-fv

- ‘If Masato bought a book, I would be happy.’ conditional

These data show that in argument positions in Nata, either an overt or a covert D is in principle possible. However, the covert D is licensed only under operators. In the next section we turn to an unrelated language which shows a strikingly similar pattern in its determiners.

3 Determiners in St’át’imcets

Like Nata, St’át’imcets displays clear evidence for a strict correlation between argumenthood and the presence of a determiner. All argument nominals must contain an overt D, as shown in (12) (note that St’át’imcets is a predicate-initial language). The determiners in these examples all contain an enclitic portion =ɑ, as well as a proclitic portion which encodes number and deictic features; both portions are obligatory on arguments, although the proclitic portion can be dropped in fast speech. (Following Matthewson 1998 and anticipating the analysis we adopt, we gloss the enclitic portion as exis, for ‘existential’.)

- (12)

- a.

- Q’wez-ílc

- dance-aut

- *(ti=)smúlhats*(=a).

- *(det=)woman*(=exis)

- ‘A woman danced.’

- b.

- Léxlex

- intelligent

- *(i=)smelh…múlhats*(=a).

- *(det.pl=)pl…woman*(=exis)

- ‘Women are intelligent.’

- c.

- Wa7

- ipfv

- ts’aqw-an’-ítas

- eat-dir-3pl.erg

- *(i=)t’éc*(=a)

- *(det.pl=)sweet*(=exis)

- *(i=)míxalh*(=a).

- *(det.pl=)bear*(=exis)

- ‘Bears eat honey.’ (adapted from Matthewson 2013:19)

Example (13) shows the other half of the evidence for an argument/D correlation in St’át’imcets: predicative nominals may not contain an overt D.

- (13)

- (*Ti=)Kúkwpi7(*=a)

- (*det=)chief(*=exis)

- kw=s=Rose.

- det=nmlz=Rose

- ‘Rose is a chief.’ (adapted from Matthewson 2013:19)

It is not possible to provide a fully minimal pair with the Nata examples in (3)–(4) above, which showed a contrast between ‘Masato is a man’ (with a predicative nominal and no determiner) and equational ‘Masato is the man’ (with an argumental nominal and a determiner). The reason is that St’át’imcets lacks equational copular sentences, and expresses equational meanings via a clefting structure. Nevertheless, the determiner facts are as predicted: the predicative nominal sqaycw ‘man’ in (14) has no D, and the (clefted) argumental nominal in (15) has a D.6

- (14)

- [Is Robin a man or a woman?]

- a.

- Sqaycw

- man

- s=Robin.

- nmlz=Robin

- ‘Robin is a man.’

- b.

- *Ta=sqáycw=a

- det=man=exis man

- s=Robin.

- nmlz=Robin

- (15)

- [Out of the two people standing over there, which one is Robin?]

- a.

- Nilh

- cop

- ta=sqáycw=a

- det=man=exis

- s=Robin.

- nmlz=Robin

- ‘Robin is the man.’

- b.

- *Nilh

- cop

- sqáycw

- man

- s=Robin.

- nmlz=Robin

The full St’át’imcets determiner system is given in Table 2. We see that there is one determiner ku= which lacks the enclitic portion (plus a rare plural version of it, kwelh=); this is the determiner which we will argue corresponds semantically to the Nata covert D.7

| present | absent | remote |

ku= (kwelh=) |

|

| singular | ti=…=a | ni=…=a | ku=…=a | |

| plural | i=…=a | nelh=…=a | kwelh=…=a | |

| collective | ki=…=a | |||

3.1 DPs with ku= require a higher operator

St’át’imcets argument DPs with the determiner ku= and which lack the enclitic =ɑ are polarity sensitive, in the sense that they require a higher operator to be licensed. We see in (16) that in plain declaratives, a D with =ɑ is required on argument nominals and ku= is ungrammatical.

- (16)

- a.

- Áz’-en-as

- buy-dir-3erg

- ti=sts’úqwaz’=a

- det=fish=exis

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie bought a/the fish.’

- b.

- *Áz’-en-as

- buy-dir-3erg

- ku=sts’úqwaz’

- det=fish

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

Under negation, ku= is licensed, as shown in (17).

- (17)

- a.

- Cw7aoz

- neg

- kw=s=áz’-en-as

- det=nmlz=buy-dir-3erg

- ti=sts’úqwaz’=a

- det=fish=exis

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie didn’t buy a/the fish.’

- b.

- Cw7aoz

- neg

- kw=s=áz’-en-as

- det=nmlz=buy-dir-3erg

- ku=sts’úqwaz’

- det=fish

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie didn’t buy a fish.’ (adapted from Matthewson 1998:55)

Ku= is also licensed under modals, as shown in (18) for the future morpheme =kelh.

- (18)

- a.

- Tecwp-mín=lhkan=kelh

- buy-rlt-1sg.sbj=fut

- ti=púkw=a

- det=book=exis

- natcw.

- tomorrow

- ‘I might/will buy a/the book tomorrow.’

- b.

- Tecwp-mín=lhkan=kelh

- buy-rlt-1sg.sbj=fut

- ku=púkw

- det=book

- natcw.

- tomorrow

- ‘I might/will buy a book tomorrow.’ (adapted from Matthewson 1998:54)

Similarly, the polar question morpheme licenses the polarity sensitive determiner ku=, as shown in (19).

- (19)

- a.

- Ats’x-en-tsí-has=ha

- see-dir-2sg.obj-3erg=q

- ti=szús-cal=a?

- det=tie.up-act=exis

- ‘Did a/the policeman see you?’

- b.

- Áts’x-en-tsí-has=ha

- see-dir-2sg.obj-3erg=q

- ku=szús-cal?

- det=tie.up-act

- ‘Did a policeman see you?’ (adapted from Matthewson 1998:195)

Finally, conditionals also license ku=, as shown in (20).

- (20)

- a.

- Cuz’

- prosp

- tsa7cw

- happy

- kw=s=Mary

- det=nmlz=Mary

- lh=t’íq=as

- comp=arrive=3sbjv

- ti=qelhmémen’=a.

- det=old.person[dimin]=exis

- ‘Mary will be happy if an elder comes.’

- b.

- Cuz’

- prosp

- tsa7cw

- happy

- kw=s=Mary

- det=nmlz=Mary

- lh=t’íq=as

- comp=arrive=3sbjv

- ku=qelhmémen’.

- det=old.person[dimin]

- ‘Mary will be happy if any elder comes.’ (Matthewson 1999:90)

In this section we have seen that St’át’imcets – just like Nata – shows a distinction in its determiner system between one set of determiners that are not polarity sensitive, and one determiner that is polarity sensitive. The only difference is that in Nata, the polarity sensitive determiner happens to be phonologically covert, while in St’át’imcets, it is overt (but lacks the enclitic portion shared by all the non-polarity-sensitive determiners).

In the next section we turn to the question of what semantic distinction is encoded by the determiner systems of Nata and St’át’imcets.

4 D distinctions in Nata and St’át’imcets: The importance of existence

So far we have shown that Nata and St’át’imcets, two completely unrelated languages, both have systems involving one determiner which requires licensing by a higher operator. Moreover, the higher operators seem to be the same in both languages: negation, modals, polar questions and conditionals.8 The basic structure of the determiner systems is summarized in Table 3.

Nata and St’át’imcets determiner systems.

| plain determiners | polarity sensitive determiner | |

| Nata | overt augment | covert augment |

| St’át’imcets | determiners ending in =ɑ | ku= |

The question now is what semantic distinction is conveyed by the choice between overt and covert Ds in Nata, and between determiners of the form X=…=ɑ and ku= in St’át’imcets.

Some frequently attested determiner distinctions in the world’s languages are definiteness (Frege 1892; Russell 1905; Heim 1982; 1991, among others) and specificity (Enç 1991; Ionin 2006, among others). In this section we argue that Nata and St’át’imcets determiners encode neither definiteness or specificity, and that instead they reflect the speaker’s commitment to the existence of a referent for the DP.

4.1 Nata and St’át’imcets Ds do not encode definiteness or specificity

4.1.1 Nata Ds do not encode definiteness

Definites typically have referents which are familiar to the addressee, while indefinites typically introduce novel discourse referents. In (21) we see that an overt D can be used for both novel and familiar referents. This shows that the overt/covert D contrast in Nata does not correlate with familiarity vs. novelty.

- (21)

- Hayo

- there

- kárɛ

- long.ago

- n=a-arɛ-ho

- foc=sa1-be-loc

- o=mu-tɛmi …

- det=c1-chief…

- ‘Long ago there was a chief …’ (novel)

- Mbɛ

- so

- o=mu-tɛmi

- det=c1-chief

- a-ɣa-kóm-a

- sa1-pst-gather-fv

- a=βáa-to.

- det=c2-people

- ‘So, the chief gathered the people.’ (familiar)

Definites are also well-known to assert or presuppose uniqueness, while indefinites do not (Russell 1905; Frege 1892; Heim 1982; 1991). The Nata overt/covert D contrast also does not correlate with uniqueness, as shown in (22): an overt D can be used for both unique and non-unique referents.

- (22)

- a.

- I=rjooβá

- det=c5-sun

- n-de-ku-βára

- foc-c5-prog-shine

- tʃwɛɛ.

- indeed

- ‘The sun is really shining.’ (unique)

- b.

- A=n-tʃɔtá

- det=c9-star

- y-e-ku-βara

- cop-c3-prog-shine

- tʃwɛɛ.

- indeed

- ‘A star is really shining.’ (non-unique)

4.1.2 St’át’imcets Ds do not encode definiteness

In St’át’imcets, determiners ending in =ɑ can be used for both novel and familiar referents, as shown in (23).

- (23)

- Húy’=lhkan

- prosp=1sg.sbj

- ptakwlh,

- tell.story

- ptákwlh-min

- tell.story-rlt

- lts7a

- here

- ti=smém’lhats=a …

- det=woman[dimin]=exis

- ‘I am going to tell a legend, a legend about a girl …’ (novel)

- Wá7=ku7

- ipfv=report

- ílal

- cry

- láti7

- deic

- ti=smém’lhats=a.

- det=woman[dimin]=exis

- ‘The girl was crying there.’ (familiar)

- (adapted from van Eijk and Williams 1981:19; cited in Matthewson 1998:34)

As shown in (24), Ds ending in =ɑ can also be used for both unique and non-unique referents. This confirms that the major distinction within the St’át’imcets determiner system does not reflect a definiteness contrast.

- (24)

- a.

- Ka-hál’h-a

- circ-show-circ

- ta=snéqwem=a.

- det=sun=exis

- ‘The sun appeared.’ (unique)

- b.

- Ka-hál’h-a

- circ-show-circ

- ta=nkakúsent=a.

- det=star=exis

- ‘A star appeared.’ (non-unique)

- (adapted from Matthewson 1999:107;109)

4.1.3 Nata Ds do not encode specificity

There are many analyses of specificity in the literature; here we assume a classic understanding whereby a specific referent is known to the speaker as a particular individual, while a non-specific DP can be approximately rendered by simple existential quantification. A language which overtly encodes a specificity distinction is Persian, as shown in (25); the suffix –RA on a noun phrase signals specificity.

- (25)

- a.

- Emruz

- today

- ye

- a/one

- vakil-(i)-o

- lawyer-(I)-ra

- mi-bin-am.

- dur-see-1sg

- ‘I am seeing a (particular) lawyer today.’

- b.

- Emruz

- today

- ye

- a/one

- vakil

- lawyer

- mi-bin-am.

- dur-see-1sg

- ‘I am seeing a lawyer today (some lawyer or other).’ (Hedberg et al. 2009)

In Nata, an overt D can be used for specific referents, as illustrated in (26), but an overt D can also be used for non-specific referents, as in (27). Note that in English, specific indefinite this is infelicitous in (27)A; see for example Gundel et al. (1993) for discussion of specific indefinite this.9 These data therefore show that the overt/covert D distinction in Nata is not a specificity distinction.

- (26)

- [You bought a few cups from a fair-trade company. You used one for tea this morning and found out that it didn’t have a fair-trade label, but the others did. I walk in and see you looking a bit annoyed and I ask what’s up. You reply:]

- a.

- N-dɛ́ɣir-ɛ

- 1sg-hate-SBJV

- e=ɣi-kɔ́mbɛ ki-nɔ

- det=C7-cup C1-that

- ny-a-gor-ire.

- 1SG-PST-buy-PFV

- ‘I hate a cup that I bought.’ (specific)

- b.

- #N-dɛ́ɣir-ɛ

- 1sg-hate-SBJV

- Ø=ɣi-kɔ́mbɛ

- det=C7-cup

- ki-nɔ

- C1-that

- ny-a-gor-ire.

- 1SG-PST-buy-PFV

- Intended: ‘I hate a cup that I bought.’

- (27)

- [There are a bunch of cups lying on the table.]

- A:

- N-uu-h-ɛ

- 1sg-2SG-give-SBJV

- e=ɣi-kɔ́mbɛ!

- det=C7-cup

- ‘Pass me a cup!’ (non-specific)

- B.

- Ki-h-ɛ

- C7-give-SBJV

- ki-jɔ?

- C7-which

- Which one?

- A:

- Kjɔ-kj-ɔ́sɛ

- REDUP-C7-any

- haŋu!

- just

- ‘Just any!’

4.1.4 St’át’imcets Ds do not encode specificity

In St’át’imcets as well, as shown by Matthewson (1998), the contrast between determiners that end in =ɑ and the determiner which does not is not a specificity distinction. This is shown in (28)–(29), where we see the same determiner ti=…=ɑ being used for both specific (28) and non-specific (29) referents.

- (28)

- [You bought a few cups from a fair-trade company. You used one for tea this morning and found out that it didn’t have a fair-trade label, but the others did. I walk in and see you looking a bit annoyed and I ask what’s up. You reply:]

- Qvl-s=kán

- bad-caus=1sg.sbj

- ta=zaw’áksten=a

- det=cup=exis

- n=s=tecwp.

- 1sg.poss=nmlz=buy

- ‘I hate a cup that I bought.’ (specific)

- (29)

- [There are a bunch of cups lying on the table.]

- A:

- Sima7-cí-ts

- come-ind=2sg.obj

- ta=zaw’áksten=a!

- det=cup=exis

- ‘Pass me a cup!’ (non-specific)

- B:

- Nka7

- where

- ku=zaw’áksten

- det=cup

- ku=xát’-min’=acw?

- det=want-red=2sg.sbjv

- ‘Which do you want?’

- A:

- Sima7-cí-ts

- come-ind=2sg.obj

- ku=nká7=as=t’u7

- det=where=3sbjv=excl

- ku=zaw’áksten!

- det=cup

- ‘Just pass me ANY cup!’

4.2 Nata and St’át’imcets Ds reflect speaker commitment to existence

We argue that Nata and St’át’imcets Ds distinguish the contrast between the presence and absence of the speaker’s commitment to the existence of a referent for the DP. An informal definition of this notion of ‘existence’, taken from Givón’s (1978:293–294) discussion of the Bantu language Bemba, is “Roughly, the speaker’s intent to ‘refer to’ or ‘mean’ a nominal expression to have non-empty references – i.e. to ‘exist’ – within a particular universe of discourse (i.e., not necessarily within the real world).” Applied to Nata and St’át’imcets, our proposal is that Nata overt Ds and St’át’imcets Ds containing =ɑ convey the speaker’s commitment to the existence of a referent for the noun phrase. Nata covert Ds and St’át’imcets ku= convey a lack of speaker commitment to existence.10

We will spell this out more formally in section 6 below. In the remainder of this section we provide data in support of the notion of speaker-oriented existence as the deciding factor in determiner choice in both languages.

4.2.1 Nata Ds encode existence

In a plain affirmative sentence such as (30), it is no surprise that the speaker is committed to the existence of a book which Makuru bought.

- (30)

- Makurú

- Makuru

- a-ka-ɣór-a

- sa1-pst-buy-pfv

- e=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Makuru bought a/the book.’

- “There exists a book which Makuru bought.”

The two negated sentences in (31)–(32) show the effect of determiner choice. In (31) with an overt D, the speaker is committed to the existence of a book which Makuru didn’t buy. This is compatible with a scenario in which Makuru bought one or more of the available books, as long as there is at least one he did not buy. Example (32), with the covert D, is not compatible with there having been any books that Makuru bought; the sentence is only true if Makuru bought no book at all.

- (31)

- Makurú

- Makuru

- t-a-a-ɣor-iré

- neg-sa1-pst-buy-pfv

- e=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Makuru did not buy a/the book.’

- “There exists a book which Makuru didn’t buy.”

- (32)

- Makurú

- Makuru

- t-a-a-ɣor-iré

- neg-sa1-pst-buy-pfv

- Ø=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- ‘Makuru did not buy a/any book.’

- “There does not exist a book which Makuru bought.”

The covert D cannot appear in a plain affirmative sentence, as shown in (33). We will derive this fact by requiring that the covert D scopes under a higher intensional operator (i.e., that it appears in a non-veridical context; see immediately below for the definition of non-veridicality).

- (33)

- *Makurú

- Makuru

- a-ka-ɣór-a

- sa1-pst-buy-pfv

- Ø=ɣí-taβo.

- det=c7-book

- Intended: Makuru bought a book.

The speaker’s commitment to existence of a referent includes existence in dreams, as shown in (34)–(35).

- (34)

- N-ka-rɔɔt-a

- 1sg-pst-dream-fv

- a=ma-nani

- det=c6-ogres

- ɣa-ra-rwáan-a.

- sa-prog-fight-fv

- ‘I dreamed about ogres fighting with each other.’

- (35)

- *N-ka-rɔɔt-a

- sa-1sg-pst-dream-fv

- Ø=ma-náni

- det=c6-ogres

- ɣa-ra-rwáan-a.

- sa-prog-fight-fv

- ‘I dreamed about ogres fighting with each other.’

The patterning of dream contexts with speaker beliefs is found in other languages. For example, in her study of polarity-sensitive elements across languages, Giannakidou (1998) argues that the relevant notion for the licensing of polarity items is (non-)veridicality, defined as follows:

- (36)

- A propositional operator Op is veridical if and only if the truth of Op(p) in a context c requires that p be true in some individual’s epistemic model in c. An operator Op is nonveridical if and only if the truth of Op p in c does not require that p be true in some such model in c. (Giannakidou 1998:112)

Relevant for current concerns is the fact that according to Giannakidou (1998:32–33;112), the epistemic models that count for (non-)veridicality, and therefore for polarity licensing, include not only belief models (worlds compatible with what an individual believes about the actual world), but also dream models (worlds compatible with what an individual dreams). This accounts for the fact that the attitude verb dream, at least in some languages, is veridical and takes an indicative rather than a subjunctive embedded clause; see Farkas (1992); Giannakidou (1998), among others.

This same phenomenon – the patterning of dream contexts with ordinary belief – is interestingly at play also in the Nata determiner system. Below, we will adopt an analysis of Nata and St’át’imcets determiners that pays attention to the (non-)veridicality distinction. While we will not work out a full formal account of the dream cases, we anticipate that the ideas found in Giannakidou’s work will play a role in the final account of these.

4.2.2 St’át’imcets Ds encode existence

In St’át’imcets as in Nata, the semantic contrast between the two determiner types reflects the speaker’s (non-)commitment to the existence of a nominal referent. This was originally proposed by Matthewson (1998), who termed the determiners which end in =ɑ ‘assertion of existence’ determiners. The sentences in (37)-(40) parallel the Nata examples above. We see in (37) that a determiner ending in =ɑ is compatible with an affirmative declarative, which entails the existence of the relevant referent. (38)-(39) show that when an =ɑ determiner co-occurs with negation, the sentence as a whole unambiguously asserts that there exists at least one fish that Sophie did not buy, but when the ku= determiner co-occurs with negation, there must exist no fish at all that she bought. Finally, (40) reveals that ku= is not licensed in an ordinary declarative sentence.

- (37)

- Áz’-en-as

- buy-dir-3erg

- ti=sts’úqwaz’=a

- det=fish=exis

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie bought a/the fish.’

- “There exists a fish which Sophie bought.”

- (38)

- Cw7aoz

- neg

- kw=s=áz’-en-as

- det=nmlz=buy-dir-3erg

- ti=sts’úqwaz’=a

- det=fish=exis

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie didn’t buy a/the fish.’

- “There exists a fish which Sophie didn’t buy.”

- Can be true if Sophie bought 3 out of the 4 available fish.

- (39)

- Cw7aoz

- neg

- kw=s=áz’-en-as

- det=nmlz=buy-dir-3erg

- ku=sts’úqwaz’

- non.exis.det=fish

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie didn’t buy a fish.’

- “There does not exist a fish which Sophie bought.”

- Only true if Sophie bought no fish at all.

- (40)

- *Áz’-en-as

- buy-dir-3erg

- ku=sts’úqwaz’

- non.exis.det=fish

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- Intended: Sophie bought a fish.

A further striking parallel between the two languages is that in St’át’imcets as well as Nata, the existence-entailing determiners are the ones used to convey existence within dream-worlds.

- (41)

- Kw7íkwlacw=kan

- dream=1sg.sbj

- kwas

- det+nmlz+ipfv+3poss

- túp-un’-as

- punch-dir-3erg

- s=John

- nmlz=John

- ti=plísmen=a.

- det=policeman=exis

- ‘I dreamed that John hit a policeman.’

- (42)

- *Kw7íkwlacw=kan

- dream=1sg.sbj

- kwas

- det+nmlz+ipfv+3poss

- túp-un’-as

- punch-dir-3erg

- s=John

- nmlz=John

- ku=plísmen.

- non.exis.det=policeman

- (adapted from Matthewson 1998:132)

Summarizing this section, we have argued that neither Nata nor St’át’imcets determiners encode a definiteness contrast, and nor do they encode specificity. Instead, they encode a distinction between whether the speaker is committed to the existence of a referent for the nominal, in either the real world or in dreams. One might term these ‘speaker-oriented existence’ determiners, because there is no impact of the common ground on determiner choice (as there is, for example, in English): the speaker’s belief or knowledge state is the sole factor involved in the choice between the two classes of determiners in each language (in Nata: overt vs. covert; in St’át’imcets: determiners ending in =ɑ vs. ku= without an =ɑ).

The parallels between these two unrelated languages are striking. However, the story does not end here. We are about to see that the two languages differ in the precise contexts in which their existence determiners are possible.

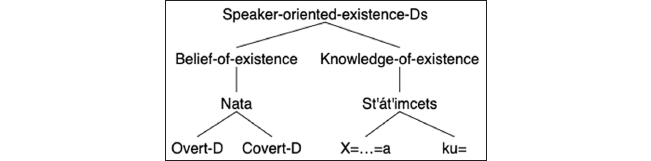

5 The difference between Nata and St’át’imcets: Belief vs. knowledge

In this section we argue that there is a difference between Nata and St’át’imcets in the particular semantics of their speaker-oriented existence determiners. In Nata, the overt D is used to convey the speaker’s belief in the existence of a nominal referent, whereas in St’át’imcets, the =ɑ Ds are used to convey the speaker’s knowledge of the existence of the referent. Notice that knowledge of existence entails belief of existence but not vice versa: if one knows something, one also believes it, but one can believe something without knowing it. This means that the St’át’imcets existence determiners are used in a subset of the contexts in which the Nata existence determiners are used.

The landscape of speaker-oriented existence determiners we are proposing is schematized in Figure 3. In the discussion immediately below, we empirically motivate our suggested distinction between Nata and St’át’imcets along the belief-knowledge dimension.

In Nata, the overt determiner is used when the speaker has personal knowledge of the referent, but also when the speaker was, for example, only told by someone that the referent exists (and the speaker believes the report). This is shown in (43), and (44) shows that in these contexts, the covert determiner is disallowed.

- (43)

- O=mu-tɛmi

- det=c1-chief

- a-kaa-tʃá

- sa1-pst-come

- ku-n-dɔr-a

- inft-1sg.obj-see-fv

- itʃɔ.

- yesterday

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’

- Good in context: I saw him.

- Good in context: Someone told me.

- (44)

- *Ø=mu-tɛmi

- det=c1-chief

- a-kaa-tʃá

- sa1-pst-come

- ku-n-dɔr-a

- inf-1sg.obj-see-fv

- itʃɔ.

- yesterday

- Intended: A chief came to see me yesterday.

In St’át’imcets, on the other hand, an X=…=ɑ determiner is used if the speaker has personal knowledge of the referent, as in (45), but if the speaker was only told that the referent exists, the non-existence D ku= must be used, as shown in (46).11

- (45)

- a.

- T’ak

- go

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7=a

- det=chief=exis

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I saw him/her]

- (adapted from Matthewson 1998:179)

- b.

- *T’ak

- go

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7

- non.exis.det=chief

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I saw him/her]

- (46)

- a.

- *T’ák=ku7

- go=report

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7=a

- det=chief=exis

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I was told; I didn’t see him/her]

- b.

- T’ák=ku7

- go=report

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7

- non.exis.det=chief

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I was told; I didn’t see him/her]

The second domain where Nata and St’át’imcets determiner use diverges is in what we call (following Gambarage 2019) ‘surmising contexts’. In Nata, speakers may ‘surmise’ the existence of an entity based on a variety of cultural assumptions, and in these contexts a belief-of-existence overt D is – in fact, must be – used. Some examples of common cultural assumptions which license overt determiners include the belief that a sun-shower means that a leopard has given birth, that biting one’s tongue while eating means that someone is talking about you, and that seeing a trail of ants carrying their food means that there will be beef in the next meal. An example is provided in (47).

- (47)

- [There is a sun-shower outside. B says…]

- a.

- Á=ŋ-gwe

- det=c9-leopard

- j=e-ku-βá

- foc=sa9-prog-be

- e-ri-iβór-a.

- sa9-PERS-give.birth-fv

- ‘A leopard will be giving birth.’

- b.

- *Ø=ŋ-gwe

- det=c9-leopard

- j=e-ku-βá

- foc=sa9-prog-be

- e-ri-iβór-a.

- sa9-PERS-give.birth-fv

- Intended: A leopard will be giving birth.

St’át’imcets is different. In ‘surmise’ contexts where the speaker does not have personal knowledge of the referent, the polarity D ku= must be used, as shown in (48).12

- (48)

- [Suppose there is a belief in this community that if you see a ts’úqum’ (chickadee), somebody’s going to visit. Can you say:]

- #Cuz’

- prosp

- t’iq

- arrive

- ta=ucwalmícw=a

- det=person=exis

- lh=kalál=as.

- comp=soon=3sbjv

- ‘Someone is going to visit.’

- Consultant: Corrects ta=…=ɑ to ku= (ta=…=ɑ is okay if you know the person that might be coming).

The third difference between the languages is that in Nata, speakers use the overt D to commit to a belief in the existence of non-materialized referents (referents that do not exist yet at the time of utterance), as in (49)-(50), while in St’át’imcets, speakers have to use the non-existence D ku= when the referents of the noun phrase do not yet exist, as shown in (51)-(52).

- (49)

- N=ne-ɣo-kwir-u

- FOC-1sg-fut-marry-pass

- na

- with

- o=mu-temi

- det=c1-chief

- u-nɔ

- c1-who

- a-kuu-tʃ-a.

- sa1-fut-come-fv

- ‘I will marry the next chief.’

- (50)

- *N=ne-ɣo-kwir-u

- FOC-1sg-fut-marry-pass

- na

- with

- Ø=mu-temi

- det=c1-chief

- u-nɔ

- c1-who

- a-kuu-tʃ-a.

- sa1-fut-come-fv

- Intended: ‘I will marry the next chief.’

- (51)

- Cúz’=lhkan

- prosp=1sg.sbj

- melyí-s

- marry-caus

- ku=cúz’

- non.exis.det=prosp

- kúkwpi7

- chief

- láku7

- deic

- Fountain.

- Fountain

- ‘I will marry the next chief of Fountain.’ (whoever it is).

- (adapted from Matthewson 1998:57)

- (52)

- *Cúz’=lhkan

- prosp=1sg.sbj

- melyí-s

- marry-caus

- ku=cúz’=a

- det=prosp=exis

- kúkwpi7

- chief

- láku7

- deic

- Fountain.

- Fountain

- ‘I will marry the next chief of Fountain.’ (whoever it is).

The similarities and differences between Nata and St’át’imcets determiners are summarized in Table 4. Both languages allow existence determiners when the speaker has personal knowledge of the referent of the noun phrase (the first row), and they both disallow existence determiners when there is no belief of existence in the referent (the last row). In between are the contexts where the speaker has reason to believe that there might be a referent, but does not have direct personal knowledge of the referent. In all these cases, Nata allows an overt D, but St’át’imcets disallows an X=…=ɑ D.13

When an overt D / X=…=ɑ D can be used.

| Nata | St’át’imcets | |

| speaker’s personal knowledge | ✔ | ✔ |

| reported knowledge | ✔ | ✖ |

| cultural assumptions | ✔ | ✖ |

| not yet materialized | ✔ | ✖ |

| no belief of existence | ✖ | ✖ |

The data above have shown that Nata overt Ds are more permissive than St’át’imcets X=…=ɑ Ds. This reflects the fact that knowledge of existence asymmetrically entails belief of existence.

6 Analysis

We have shown that in both Nata and St’át’imcets, Ds encode a speaker-oriented distinction based on the existence of a referent for the noun phrase. In St’át’imcets, Ds ending in =ɑ are used when the speaker knows that a referent exists. In Nata, overt Ds are used when the speaker has reason to believe that a referent exists.

For the St’át’imcets X=…=ɑ determiners, we adopt a choice function analysis, following Matthewson (1999; 2001). This analysis was designed to account for the extraordinary widest-scope effects of these determiners. Matthewson (1998; 1999) shows that DPs containing X=…=ɑ determiners take wide scope over quantifiers, if-clauses, negation and modals, no matter whether they are embedded inside syntactic islands. An example is given in (53) (repeated from (20a), but here with more information about the available readings). We see that the DP ti=qelhmémen’=ɑ ‘an elder’ takes obligatory wide scope outside the if-clause, something which is not achievable via standard analyses of Quantifier Raising (cf. Reinhart 1997; Winter 1997).

- (53)

- Cuz’

- prosp

- tsa7cw

- happy

- kw=s=Mary

- det=nmlz=Mary

- lh=t’íq=as

- comp=arrive=3sbjv

- ti=qelhmémen’=a.

- det=old.person[dimin]=exis

- ‘Mary will be happy if an elder comes.’

- Accepted in context: There are a bunch of elders in this community. Mary dislikes most of these elders and doesn’t want them to come. There is just one elder who she wants to come.

- Rejected in context: Mary will be happy if any elders come, but that’s impossible, because there are no elders in this community. (Matthewson 1999:90)

Choice functions are operations which apply to a set (e.g. the set of elders) and choose one member from that set. As shown by Kratzer (1998), choice functions can be used to achieve widest-scope effects (what Kratzer terms ‘pseudo-scope’). Following Kratzer’s analysis (also adopted by Matthewson 2001), we propose that X=…=ɑ Ds introduce free variables over choice functions which are assigned a value via the assignment function. The choice function is parameterized to the speaker: it provides a way of choosing, for the speaker, an individual from a set of individuals.14

How this works is illustrated in (54)–(55) for affirmative and negative sentences respectively; similar effects are derived for X=…=ɑ DPs ‘scoping’ over other operators.

- (54)

- Áz’-en-as

- buy-dir-3erg

- ti=sts’úqwaz’=a

- det=fish=exis

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie bought a/the fish.’

- [buy (Sophie, fspkr(fish)]

- ≈ ‘According to the speaker’s method of choosing one fish from the set of fish, Sophie bought the fish chosen by that method.’

This denotation entails that there exists a fish which Sophie bought.

- (55)

- Cw7aoz

- neg

- kw=s=áz’-en-as

- det=nmlz=buy-dir-3erg

- ti=sts’úqwaz’=a

- det=fish=exis

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie didn’t buy a/the fish.’

- ¬ [buy (Sophie, fspkr(fish)]

- ≈ ‘According to the speaker’s method of choosing one fish from the set of fish, Sophie didn’t buy the fish chosen by that method.’

This denotation entails that there exists a fish which Sophie did not buy. It correctly still allows her to buy other fish.

It is important to note that the speaker does not have to know the identity of the individual chosen by the choice function. In this we follow Kratzer (2003), who argues that ‘a person can successfully refer to a choice function without necessarily knowing what that choice function is. And even if she knows what the function is, that all by itself doesn’t imply that she knows what the actual individual is that the function picks out.’ As a result of this, the choice function determiners are not necessarily specific, in the sense that a referent is known to the speaker as a particular individual. Thus, we still successfully rule in non-specific uses of choice-function determiners as in (29) above.

For DPs containing the non-existence determiner ku=, following Matthewson (1998; 1999) we assume that these are interpreted as existential quantifiers which obligatorily must take narrow scope under a non-factual operator. The obligatory narrow scope of ku=DPs is illustrated in (56), and a statement of the truth conditions for a simple sentence containing negation is given in (57).

- (56)

- Cuz’

- prosp

- tsa7cw

- happy

- kw=s=Mary

- det=nmlz=Mary

- lh=t’íq=as

- comp=arrive=3sbjv

- ku=qelhmémen’.

- non.exis.det=old.person[dimin]

- ‘Mary will be happy if any elder comes.’

- Rejected in context: There are a bunch of elders in this community. Mary dislikes most of these elders and doesn’t want them to come. There is just one elder who she wants to come.

- Accepted in context: Mary will be happy if any elders come, but that’s impossible, because there are no elders in this community. (Matthewson 1999:90)

- (57)

- Cw7aoz

- neg

- kw=s=áz’-en-as

- det=nmlz=buy-dir-3erg

- ku=sts’úqwaz’

- non.exis.det=fish

- kw=s=Sophie.

- det=nmlz=Sophie

- ‘Sophie didn’t buy a fish.’

- ¬ ∃x [fish (x) & buy (Sophie, x)]

- ≈ ‘It is not the case that there is a fish which Sophie bought.’

(57) is true only if Sophie bought no fish at all.

An analysis in terms of non-veridicality seems warranted here, following ideas by Giannakidou (1998). According to Matthewson (1998:190), ‘All the environments in which ku is allowed are environments in which the truth of a proposition is not asserted.’ These are non-veridical environments, and Giannakidou’s ‘affective polarity items’ are licensed in all the contexts we have discussed for St’át’imcets and Nata polarity determiners: under negation, modals, future marking, in conditional antecedents, and in questions. In Giannakidou’s (1998) formal analysis, polarity items have sensitivity features, encoding that they are deficient in some respect and a licensing context is required to provide the missing piece. Affective polarity items are existential quantifiers that fail to introduce discourse referents in the actual world, or in some individual’s epistemic model. This is shown in (58); the subscript ‘ni’ stands for ‘no introduction of discourse referent’ (Giannakidou 1998:70).

- (58)

- An existential quantifier ∃xni is dependent iff the variable xni it contributes does not introduce a discourse referent in the speaker’s epistemic model.

- (adapted from Giannakidou 1998:140)

This analysis derives the ban on ku= DPs in affirmative matrix environments. As Giannakidou (1998:140) writes, ‘If we use a dependent existential in a veridical domain … the quantifier will not be able to introduce a discourse referent and the resulting formula cannot be assigned a truth value.’

Given all this, the denotation of the polarity determiner ku= can be rendered as in (59). It is exactly like an ordinary existential quantifier, except for the dependency that restricts it to non-veridical environments. The determiner takes two predicative arguments and asserts that there is an individual that satisfies both of them, but the individual does not introduce a discourse referent in the speaker’s epistemic model so the determiner must scope under a non-veridical operator.

- (59)

- ⟦ ku= ⟧ = λP<e,t> λQ<e,t>. ∃xni [P(xni) & Q(xni)]

Turning to Nata, there is evidence for a similar approach, although we will have to deal with the difference between knowledge and belief of existence. In terms of the scope facts, Gambarage (2019) shows that just like with St’át’imcets X=…=ɑ Ds, the Nata overt D displays widest-scope effects, while the covert D takes obligatory narrow scope. This is illustrated in (60) and (61). Crucially, in (60) the DP that contains an overt D, o=mu-ɣáruka ‘a/the elder’, is not only allowed, but even required, to be interpreted outside the scope of the if-clause.

- (60)

- O=mu-ɣáruka

- det=c1-elder

- a-ŋga-βɔnɛk-ire

- sa3-cond-show.up-pfv

- Maria

- Maria

- n=a-ŋga-tʃɔɔmir-u.

- foc=pst-cond-be.happy-fv

- ‘If an/the elder showed up Mary would be happy.’

- (adapted from Gambarage 2019:202–203)

- Accepted in context: A mother has a sick child and only elderly people know the traditional cure for the disease. There is a specific elder who knows the medicine for the disease. The mother says she will be happy if that elder showed up.

- Rejected in context: A mother has a sick child and only elderly people know the traditional cure for the disease. She would be happy if any elder comes, but that’s impossible, because there are no elders in this community.

- (61)

- Ø=mu-ɣáruka

- det=c1-elder

- a-ŋga-βɔnɛk-ire

- sa1-cond-show.up-pfv

- Maria

- Maria

- n=a-ŋga-tʃɔɔmir-u.

- foc=sa1-cond-be.happy-fv

- ‘If any elder showed up Mary would be happy.’

- (adapted from Gambarage 2019:166–167)

- Rejected in context: A mother has a sick child and only elderly people know the traditional cure for the disease. There is a specific elder who knows the medicine for the disease. The mother says she will be happy if that elder showed up.

- Accepted in context: A mother has a sick child and only elderly people know the traditional cure for the disease. She would be happy if any elder comes, but that’s impossible, because there are no elders in this community.

See also (31)-(32) above, where it was shown that Nata DPs with overt determiners obligatorily scope over negation, while DPs with covert determiners obligatorily scope under negation.15

Based on these facts, it looks as if Nata is amenable to the St’át’imcets analysis: overt determiners introduce choice functions that are given their value by the assignment function (leading to ‘pseudo-scope’ effects), and covert determiners introduce existential quantifiers which obligatorily scope under non-factual operators. However, this would leave unexplained the ways in which the two languages differ: in cases where the speaker has only heard about the referent via a report (43)–(46), in ‘surmising’ contexts (47)–(48), and with non-materialized referents (49)–(52). In these contexts, Nata allows the overt determiner, but St’át’imcets does not allow an X=…=ɑ determiner.

As we argued above, the unifying theme behind the set of contexts where Nata and St’át’imcets differ is that in these contexts, the speaker believes in the existence of a referent, but does not know that one exists. We tentatively propose that the difference between the languages’ determiner system is related to another independent difference between Nata and St’át’imcets: only St’át’imcets has a grammaticalized evidential system.

St’át’imcets possesses a set of evidentials (analyzed formally as epistemic modals by Matthewson et al. 2007; Rullmann et al. 2008; Matthewson 2012). These include the reportative =ku7, inferential =k’a, and perceived-evidence =an’, as illustrated in (62)–(64).

- (62)

- [It’s March and you’re thinking about the snow up in Lillooet.]

- Wá7=k’a

- ipfv=infer

- tsu7c

- melt.inch

- ta=máq7=a.

- det=snow=exis

- ‘The snow must be melting.’

- (63)

- [Your friend told you the snow is melting at the moment.]

- Wá7=ku7

- ipfv=report

- tsu7c

- melt.inch

- ta=máq7=a.

- det=snow=exis

- ‘The snow is melting (I was told).’

- (64)

- [You see little streams of water running down from the mountain.]

- Wa7=as=an’

- ipfv=3sbjv=perc.evid

- tsu7c

- melt.inch

- ta=máq7=a.

- det=snow=exis

- ‘The snow is melting (I perceive).’

If there is no overt evidential, as in (65), it is strongly implied that the speaker has direct evidence for the prejacent event.

- (65)

- [You saw the snow melting.]

- Wa7

- ipfv

- tsu7c

- melt.inch

- ta=máq7=a.

- det=snow=exis

- ‘The snow is melting (I saw it).’

Nata lacks such an evidential system, as shown by the fact that the sentence in (66) is appropriate with a range of different evidential situations. The case parallel to (62), where the speaker is reasoning based on inference, is as in (67). The tense/aspect morphology is different from the other cases in (66), but there is no explicitly evidential morphology in any of the contexts.

- (66)

- [Context: Your friend told you the snow is melting at the moment.]

- [Context: You see little streams of water running down from the mountain.]

- [Context: You saw the snow melting.]

- A=βaráfu

- det=c9.snow

- i-yáyok-ire.

- sa9-melt-pfv

- ‘The snow has melted.’

- (67)

- [It’s June and you’re thinking about the snow up in Mt. Kilimanjaro.]

- A=βaráfu

- det=c9.snow

- y=e-kuβá

- foc-sa9-be

- i-yáyok-ire.

- c9-melt-pfv

- ‘The snow must be melting.’

Given this independent variation between Nata and St’át’imcets, it could be that the difference in determiner meanings falls out from evidentiality. Suppose that the contexts in which Nata allows existence determiners, but St’át’imcets does not, are actually contexts in which the speaker believes in the existence of a referent, but does not have direct evidence that it exists. The speaker has not personally witnessed the referent – either because it was witnessed by a third person who gave the speaker a report, or because its existence is inferred using cultural assumptions, or because it is only postulated to exist in the future.

This would means that in both languages, the existence determiners introduce speaker-oriented choice functions and sentences containing them commit the speaker to the belief that the referent of the DP exists. In St’át’imcets, there is an additional requirement (independently attested) that an indirect propositional-level evidential must be used when the speaker lacks direct evidence for the entailments of their assertions. This will rule out the X=…=ɑ determiners in ‘surmising’ and other similar contexts.16 In Nata, there is no such evidential requirement. So when a Nata speaker talks about leopards giving birth that they have not personally witnessed, that is appropriate. They believe such leopards exist, so they make the assertion, which entails existence of the leopards. A St’át’imcets speaker cannot do this, and must in these contexts use a non-existence determiner instead.17

This also explains the interaction between determiners and the reportative evidential in examples (45)–(46) above, repeated here as (68)–(69). In (68), there is no overt evidential so the speaker has direct evidence for the prejacent proposition; this includes that they saw the chief, so the only appropriate determiner is an existence D. In (69), the reportative conveys that the speaker did not personally witness the chief’s visit; this means they do not have direct evidence that there existed a chief who visited, and the only appropriate determiner is ku=. Of course, if one does have direct evidence for the existence of an individual, but only indirect evidence of an event they are involved in, then a reportative evidential can co-occur with an existence determiner. An example of that can be found in (63) above.18

- (68)

- a.

- T’ak

- Go

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7=a

- det=chief=exis

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I saw him/her]

- (adapted from Matthewson 1998:179)

- b.

- *T’ak

- Go

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7

- non.exis.det=chief

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I saw him/her]

- (69)

- a.

- #T’ák=ku7

- go=report

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7=a

- det=chief=exis

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I was told; I didn’t see him/her]

- b.

- T’ák=ku7

- go=report

- áts’x-en-ts-as

- see-dir-1sg.obj-3erg

- ku=kúkwpi7

- non.exis.det=chief

- i=nátcw=as.

- when.pst=day=3sbjv

- ‘A chief came to see me yesterday.’ [I was told; I didn’t see him/her]

7 Conclusion

7.1 Summary of findings

In this paper we have proposed that the augment in Nata is a D(eterminer), and that it has overt and covert versions. The overt/covert D distinction corresponds to the notion of ‘belief of existence’ – whether the speaker believes the referent of the DP exists. We have further argued that Ds in Nata are very similar to Ds in St’át’imcets, which also distinguish speaker-oriented existence. The languages pattern similarly in that the existence determiners are obligatory in ordinary declarative sentences, and that the Ds that do not commit the speaker to a belief in existence are polarity determiners: they require licensing by a non-factual operator such as negation, if-clauses, modals or in questions.

The Nata and St’át’imcets determiner systems, while very similar, display one systematic difference: there is a set of cases in which Nata existence Ds are allowed, but St’át’imcets existence Ds are not. These include what we have called ‘surmising’ contexts – cases in which cultural beliefs lead a speaker to believe in the existence of a referent for which they do not have direct personal evidence. We have proposed that this difference is a function of the fact that St’át’imcets is a language with grammaticized evidentials; in the absence of an indirect evidential, a St’át’imcets speaker commits themself to having direct evidence for their assertions, and therefore to having direct evidence for the existence of any referents. Another way to look at this is that Nata determiners encode belief of existence, while St’át’imcets determiners encode knowledge of existence.

7.2 Extensions – cross-linguistic variation within Bantu

Looking beyond Nata, there is evidence that a D contrast based on a core notion of ‘existence’ is pertinent to other Bantu languages with augments; see Gambarage (2019) for detailed discussion. Gambarage illustrates with evidence from Runyankore-Rukiga, Haya, Luganda, Kinande, Xhosa, Zulu, Bemba and Dzamba that Bantu augment languages present microparametric variation in existence-D systems. In some languages, the D systems encode speaker knowledge. Gambarage (2019) shows that the D system of Bemba, for instance, is similar to the St’át’imcets system in involving knowledge-of-existence (KoE) Ds. Gambarage also discusses Bantu languages with D systems in which existence is only believed. Languages such as Runyankore-Rukiga, Haya, Luganda, Kinande, Xhosa and Zulu have D systems that pattern like the Nata belief-of-existence (BoE) system. Gambarage further argues that it is possible to have augment languages that do not encode existence at all. Dzamba, a language spoken in the Northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo, appears to have a D distinction that is based on novelty–familiarity (definiteness) (see also Bokamba 1971). Table 5 summarises Gambarage’s findings on the different D contrasts in Bantu in relation to the notion of existence.

Types of D system across a selection of Bantu languages.

| Languages/ Ds encode | Definiteness | Specificity | KoE | BoE |

| Luganda | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ |

| Kinande | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ |

| Haya | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ |

| Xhosa | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ |

| Zulu | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ |

| Runyankore-Rukiga | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ |

| Bemba | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ |

| Dzamba | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ |

The similarities between Bantu and Salish – two unrelated families – suggest that speaker-oriented existence is robustly available as a determiner distinction. While it is clear to us that the notion of speaker-oriented existence drives determiner choice in many languages, our results also raise a number of outstanding questions for further research. One diachronic question is what the historical direction of change is in Bantu and Salish determiner semantics – is there a tendency for languages to develop from a knowledge-of-existence system to a belief-of-existence system, or vice versa? Can we find diachronic evidence and/or evidence from a large sample of languages to support our proposal that knowledge-of-existence determiners correlate with grammaticalized evidentials, while belief-of-existence determiners appear in non-evidential languages? And finally: are there determiner systems which have been analysed or described as conveying either definiteness or specificity, but which on closer examination might turn out to really involve speaker-oriented existence?

Abbreviations

1 = first person, 2 = second person, 3= third person, abs = absent, act = active intransitivizer, aug = augment, aut = autonomous intransitivizer, c = noun class, caus = causative, circ = circumstantial modal, comp = complementizer, cond = conditional, cop = copula, deic = deictic adverb, det = determiner, dimin = diminutive, dir = directive transitvizer, dur = durative, erg = ergative, excl = exclusive marker, exis = existential, foc = focus, fut = future, fv = final vowel, inch = inchoative, ind = indirective applicative, infer = inferential, inft = infinitive, ipfv = imperfective, neg = negation, nmlz = nominalizer, obj = object, pass = passive, perc.evid = perceived evidence, pers = persistive aspect, pfv = perfective, pl = plural, poss = possessive, prep = preposition, prog = progressive, prosp = prospective, pst = past, report = reportative, rlt = relational applicative, q = question, sa = subject agreement, sbjv = subjunctive, sbj = subject, sg = singular.

Notes

- Nata is in Zone E, Group 40 and index 5. The coding system was developed by Guthrie (1948); it is used to distinguish many Bantu languages which were ambiguously named before the introduction of ISO 639–3 coding. [^]

- The copula nasal is underlyingly /n/, but here is realized as [m] after assimilating its place features to the following bilabial consonant. [^]

- The data in (3) and (4) are presented to support the claim that in Nata, there is a strict one-to-one correspondence between argumenthood and D. Predicative nominals are NPs, and therefore they lack an augment/D, while argumental nominals are DPs, and therefore they have an augment/D, even if it is null. As is well known, English does not display the same strict correspondence. For example, English predicative NPs contain an indefinite article, rather than appearing fully determiner-less (e.g., Masato is ɑ man). This has been much discussed in the literature; for a recent discussion of some of the complexities in this area, focusing on French, see Matushansky & Spector (2019). A clear one-to-one correlation between argumenthood and DP-hood is instantiated in other languages besides Nata, including Salish ones (see e.g., Matthewson 1998; Gillon 2013; section 2.3 below). [^]

- Table 1 is adapted from a table provided by an anonymous reviewer, whom we thank. The ‘semantic type’ column can be safely ignored if desired; see section 6 for our formal analysis. [^]

- Nata allows covert Ds inside subjects as well as objects, as shown in (8) and (10). The facts are different in some other Bantu languages, which show subject-object asymmetries in the licensing of polarity determiners; see for example Halpert (2012); Buell (2008) for discussion. Gambarage (2019: chapter 6) analyzes the cross-Bantu differences in subject D-licensing in terms of whether licensing happens before or after Spell-out. [^]

- Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for asking for these data. [^]

- Observant readers may notice that ku= (and kwelh=) can also appear with the enclitic portion (these are the ‘remote’ determiners). When we refer to ku= in the discussion, we mean the clitic-less version. There is dialectal variation in the pronunciation of the present and absent singular determiners ti=…=ɑ and ni=…=ɑ; these sometimes appear in the data as ta=…=ɑ and na=…=ɑ respectively. [^]

- There is one difference in the licensing operators between the two languages. As discussed in Gambarage (2019:212–215), attitude verbs such as ‘want’ license the polarity determiner inside their complements in St’át’imcets, but not in Nata. We return to this briefly in section 5 below. [^]

- Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out. The same reviewer also observes that in Turkish, accusative case (taken to be an indicator of specificity in that language) is infelicitous in (27)A. [^]

- Existence-related determiners may exist in language families beyond Bantu and Salish. For example, van den Heuvel (2006) observes that determiners in the Austronesian language Biak may encode existence, expressing whether an entity ‘really exists’ within the world of discourse (2006:207). Thanks to Sören E. Tebay (p.c.) for pointing us to this reference. [^]

- Recall that the existence determiner ku=…=ɑ in (45)a and (46)a is distinct from the non-existence determiner ku= in (45)b and (46)b, which lacks the enclitic portion (see Table 2). [^]

- A reviewer asks about determiner licensing in proverbs. These would count as surmising contexts, so we predict that existence determiners will be possible in proverbs in Nata, but not in St’át’imcets. We are unable to test this prediction for St’át’imcets as there are no known proverbs in the language, but the prediction is upheld for Nata, as shown in (i).

[^]

- (i)

- A=ma-ruɣi

- det=c6-rat

- ma-aru

- C6-many

- ɣa-ta-ha-tuk-a

- sa6-neg-hab-dig

- mw-oβo

- c3-pit

- o-gh-i.

- rel-go-fv

- ‘When many rats are working, they usually don’t dig a deep pit.’

- (i.e., similar to ‘Many cooks spoil the broth.’)

- As mentioned in footnote 8, Nata and St’át’imcets also differ in whether attitude verbs such as ‘want’ license non-existence Ds in their complements. This is illustrated in (i)-(ii). Existence Ds are also licensed under ‘want’ in St’át’imcets, as long as the speaker knows the wanted thing exists.

- (i)

- Ni-kwend-a

- 1sg-want-fv

- *(a)=Ø-swé.

- *(det)=c9-fish

- ‘I want some fish.’ (Nata; Gambarage 2019:213)

Gambarage (2019) suggests that this may derive from the semantics of the verb ‘want’ in Nata, such that it requires belief in the existence of the wanted object. [^]- (ii)

- Xát’-mín’=lhkan

- hard-rlt-1sg.sbj

- ku=ts’úqwaz’.

- non.exis.det=fish

- ‘I want some fish.’ (St’át’imcets; Matthewson 1998:193)

- The parameterization to the speaker is taken from Gluckman’s (2022) adaptation of earlier work on Nata by Gambarage (2019). Gluckman’s paper is an investigation of epistemic marking on nouns in Nyala East, another Bantu language. [^]

- There is one exception to this generalization: Nata DPs containing an overt D can scope under the singular distributive universal quantifier sg-ọsẹ ‘every’. Gambarage (2019) leaves this puzzle open, as do we. [^]

- There is another possible way to implement the idea that the determiner differences between Nata and St’át’imcets relate to evidentiality. This is to assume that the St’át’imcets Ds themselves encode evidentiality, while the Nata ones do not. Under this approach, the denotations for the Nata and St’át’imcets determiners would differ. In both languages, one set of determiners introduces choice functions, and the other introduces a narrow-scoping existential quantifier. However, St’át’imcets X=…=ɑ determiners would in addition encode direct evidentiality, while Nata determiners would be agnostic about evidence. This approach would be in line with work by Gutierrez & Matthewson (2012), Huijsmans et al. (2020), who propose evidential analyses of determiners in Nivacle (Matacoan-Mataguayan), St’át’imcets, and ʔayʔaǰuθəm (a.k.a. Comox-Sliammon, a Central Salish language). We set aside the issue of deciding between the two evidential approaches for future research. [^]

- A reviewer observes that in Kinande (a language that according to Gambarage 2019 has a belief of existence determiner system similar to that of Nata), there is a distinction between two copular verbs that encodes a type of evidentiality. If evidentiality were systematically marked in Kinande it would pose a counter-example to the line of reasoning we are developing here, but further research is required. [^]

- A reviewer doubts that the knowledge/belief distinction can be reduced to direct vs. indirect evidence, because there are languages where the two notions seem to diverge, for example allowing indirect evidentials to be used even when there is knowledge. However, in St’át’imcets all the indirect evidentials are modals (Matthewson et al. 2007), and they never entail knowledge of their prejacent proposition.

The reviewer’s comment did lead us to discover that ‘direct evidence’ in St’át’imcets must be defined so as to allow certain types of necessary truths to count, even without direct witness. In (i), the speaker never met their great-grandmother, yet uses an existential determiner.

In many languages, direct evidentials allow certain types of indirect evidence to count as direct. For example, the Cuzco Quechua direct evidential allows ‘undisputed common and learnt knowledge’ (Faller 2010). The St’át’imcets direct evidential has stricter standards than the Cuzco Quechua one: for example, St’át’imcets speakers prefer to use the reportative evidential when talking about common-knowledge propositions one has only heard by report. But the proposition that one’s great-grandmother existed is trivially true and this licenses direct evidentiality. [^]

- (i)

- [My great-grandmother died before I was born.]

- Ka-hál’h-a=ku7

- circ-appear-circ=report

- na=nts’ao7mík=a

- det.abs=great.grandmother=exis

- l=ta=tsal’álh=a.

- prep=det=Tsal’álh=exis

- ‘My great-grandmother was born in Tsal’álh.’

Ethics and consent

This research received ethical approval through the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board, approval certificate number H16-01331.

Funding information

This paper draws on research supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Nata language consultants Sabhiti Winyanya, Mnata Sarota, Nyabhikwabhe Yati (Baunsa), Mugesi Machota, Wasato Gambarage and Peter Kishora, and to St’át’imcets consultants Carl Alexander, the late Beverley Frank, the late Gertrude Ned, the late Laura Thevarge, and the late Rose Agnes Whitley.

Many thanks to Henry Davis for collecting some of the St’át’imcets data. For feedback on earlier drafts or presentations of this material, thanks to Vicki Carstens, John Gluckman, Manfred Krifka, Ken Safir, Sören E. Tebay, Malte Zimmermann, and three anonymous reviewers.

We also want to thank the audiences at various conferences at which various parts of this paper were presented: audiences at the Annual Conference of African Linguistics (ACAL) 50, the 29th annual meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA), the ninth edition of the Triple A workshop for semantic fieldworkers (Triple A) at the university of Manchester, and the Bantu9 Conference at the Malawi University of Science and Technology.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Adams, Nikki. 2010. The Zulu ditransitive verb phrase. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago dissertation.

Allen, Asiimwe. 2014. Definiteness and specificity in Runyankore-Rukiga. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University dissertation.

Bokamba, D. Georges. 1971. Specificity and definiteness in Dzamba. Studies in African Linguistics 2(3). 217–237.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2008. The scope fieldwork project. http://udel.edu/~bruening/scopeproject/scopeproject.html.

Buell, Leston. 2008. VP-internal DPs and right-dislocation in Zulu. Linguistics in the Netherlands 25, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, 37–49. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/avt.25.07bue

Burton, Strang & Matthewson, Lisa. 2015. Targeted construction storyboards in semantic fieldwork, In Bochnak, M. Ryan & Matthewson, Lisa (eds.), Semantic fieldwork methodology, 135–156. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190212339.003.0006

Carstens, Vicki & Mletshe, Loyiso. 2016. Negative concord and nominal licensing in Xhosa and Zulu. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34. 761–804. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9320-x

de Dreu, Merijn. 2008. The internal structure of the Zulu DP. Leiden: Universiteit Leiden Master’s thesis.

Déchaine, Rose-Marie & Wiltschko, Martina. 2002. Decomposing pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 33. 409–442. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/002438902760168554

Enç, Mürvet. 1991. The semantics of specificity. Linguistic Inquiry 22. 1–26.

Faller, Martina. 2010. A possible worlds semantics for Cuzco Quechua evidentials. Semantics and Linguistic Theory. Vol. 20. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v20i0.2586

Farkas, Donka F. 1992. On the semantics of subjunctive complements. In Hirschbühler, Paul & Koerner, Konrad (eds.), Romance languages and modern linguistic theory, 69–104. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.91.07far

Frege, Gottlob. 1892[1997]. On sense and reference. In Ludlow, Peter (ed.), Readings in the philosophy of language, 563–583. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gambarage, Joash J. 2012. Context-of-use of augmented and unaugmented nouns in Nata. UBC Working Papers in Linguistics 34. 45–59.

Gambarage, Joash J. 2013. Vowel harmony in Nata: An assessment of root faithfulness. In 2013 CLA Conference Proceedings, 1–15.

Gambarage, Joash J. 2019. Belief-of-existence determiners: Evidence from the syntax and semantics of Nata augments. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia dissertation.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1998. Polarity sensitivity as (non)veridical dependency. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.23

Gillon, Carrie. 2013. The semantics of determiners: Domain restriction in Skwxwú7mesh. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Givón, Talmy. 1970. Studies in Chibemba and Bantu grammar. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, Los Angeles dissertation.