1 Introduction

This paper investigates the semantic contribution of the throwing away gesture, henceforth THROW. This gesture consists of a single downward flap of a raised hand at the wrist, as illustrated in Figure 1.1 Within the extensive descriptive literature on pragmatic/interactive gestures (see, e.g., Bavelas et al. 1992; Kendon 2004; Abner et al. 2015; Müller 2017; Wehling 2017), THROW has been discussed, in particular, in recent work by Bressem and Müller (2014; 2017) and Tessendorf (2016). The aim of our paper is to contribute a formal semantic analysis to the body of knowledge on THROW, situated in the newly emerging tradition of formal gesture semantics (Lascarides & Stone 2009a; b; Ebert & Ebert 2014; Schlenker 2018a; b; Esipova 2019).

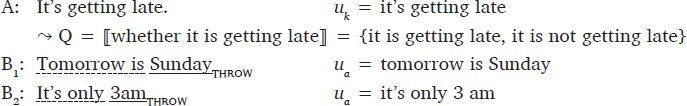

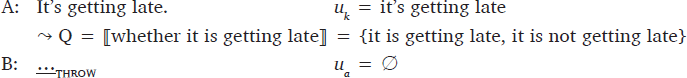

Existing work on THROW has been limited to descriptions of its intuitive effect; Bressem and Müller (2014; 2017) describe THROW as a negative assessment marker belonging to a family of gestures that metaphorically clear unwanted (discourse) objects from the gesturer’s environment. In this paper, we put the distribution and contribution of THROW under the microscope, focusing on uses of THROW that accompany or replace an entire utterance.2 We argue that THROW encodes dismissal, as opposed to other kinds of negative assessment (e.g., denial, disgust, disapproval). A concrete example is given in (1), where underlining indicates the approximate temporal alignment of the subscripted gesture; dotted (e.g.,  ) underlining marks the preparatory phase, where the hand is raised from its rest position, and regular underlining (e.g., Sunday) signifies the stroke, where the hand is lowered. By virtue of the THROW gesture, (1B) dismisses A’s statement (or, as we will argue, the question addressed by A’s statement, as spelled out in (1B-ii)). In doing so, THROW intuitively has a very similar pragmatic function to spoken language discourse markers such as who cares, whatever, so what or pah, as illustrated in (2B), to which we return in Section 4.3

) underlining marks the preparatory phase, where the hand is raised from its rest position, and regular underlining (e.g., Sunday) signifies the stroke, where the hand is lowered. By virtue of the THROW gesture, (1B) dismisses A’s statement (or, as we will argue, the question addressed by A’s statement, as spelled out in (1B-ii)). In doing so, THROW intuitively has a very similar pragmatic function to spoken language discourse markers such as who cares, whatever, so what or pah, as illustrated in (2B), to which we return in Section 4.3

- (1)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

- B:

-

SundayTHROW

SundayTHROW

- i. B’s speech asserts: tomorrow is Sunday

- ii. B’s THROW conveys: it is unimportant whether or not it’s getting late

- (2)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

- B:

- Who cares/Whatever/So what/Pah, tomorrow is Sunday!

The restricted flavour of THROW’s contribution is illustrated by the contrast in (3): THROW is compatible with the speaker’s dismissal of A’s worry in (3B1) but incompatible with the affirmation of that worry in (3B2), even if the speaker of (3B2) is taken to be expressing disapproval or disgust at A’s behaviour. Note that the use of THROW in (3B1) does not deny that A forgot to pay their bill.

- (3)

- A:

- Ack! I think I forgot to pay my credit card bill.

- B1:

-

fineTHROW

fineTHROW

- B2:

-

good#THROW

good#THROW

We propose that THROW has a discourse-managing function; it specifies how a discourse participant relates to the content of the discourse, like a wide range of expressions such as VERUM operators (e.g., Ladd 1981; Büring & Gunlogson 2000; Romero & Han 2004; Romero 2006; Krifka 2017), discourse particles (e.g., German doch, ja; see Zimmermann 2011; Gutzmann 2013; 2015; Repp 2013; Grosz 2020), commitment-related intonational contours (e.g., Gunlogson 2003; Malamud & Stephenson 2015; Rudin 2018; J. Heim 2019), confirmationals like eh and huh (e.g., Wiltschko & Heim 2016; Wiltschko 2021), and emotive markers (e.g., alas, fortunately; see, e.g., Rett 2021; for earlier research on interjections such as alas, see Ameka 1992; Norrick 2009; Goddard 2014; Riemer 2014; Sauter 2014; on evaluative adverbs such as fortunately, see Ernst 2007; 2009; Liu 2012).

The goal of this paper is twofold. Its theoretical goal is to propose a first concrete and precise formal semantic analysis of the THROW gesture. The empirical goal is to provide a detailed description of THROW’s distribution and its contribution in discourse which includes negative evidence (i.e., data about where THROW cannot be used, or what it cannot mean) in addition to positive evidence (i.e., data about where THROW can be used, and what meanings are compatible with it). While positive evidence has already been adduced from corpora in the existing literature, this paper makes an important contribution to a complete picture of THROW. Our aim is for our semantic analysis and empirical description to be precise enough that they can be used to generate testable hypotheses that are relevant to linguistic theory, and which can be evaluated in future experimental studies.

In line with Schlenker (2018b) and related work, we assume that (i) language users have introspective intuitions about the use of utterance-accompanying gestures,4 and (ii) the exploration of carefully constructed examples is a valuable part of the process of generating hypotheses. Such constructed examples and introspective data supplement meticulous corpus work, which has revealed the presence of a THROW gesture in a range of languages including French (Calbris 2011), German (Bressem & Müller 2017), Indonesian (Siahaan 2021), and Polish Sign Language (PJM), German Sign Language (DGS), and Russian Sign Language (RZY) (Kuder 2022). All of our examples, unless otherwise indicated, are constructed, and the reported judgements reflect intuitions from at least four speakers of English; we only included examples where the intuitions were clear and unanimous, and we did not include borderline cases. As far as we can tell, the core intuitions on the semantics of THROW that we report are stable across the speakers of British English, North American English and German who were consulted; this observation does not preclude, of course, that the gesture is used differently in other languages, and that there are nuances in its use that vary even within a given language community or cultural group.5

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 lays out our proposed semantics for THROW and applies it to a range of representative examples; Section 3 illustrates the merits of the proposal by extending it to a variety of case studies that go beyond the initial set of examples; Section 4 addresses similarities and differences between THROW and elements of spoken language; Section 5 discusses consequences of our proposal for theories of speech-accompanying gesture and discourse-managing meanings.

2 Proposal

2.1 Cashing out dismissal

We analyze THROW as an operator that communicates discourse-managing intentions of the person gesturing, in the spirit of Romero & Han (2004), Farkas & Bruce (2010), and Repp (2013), among many others. We also draw on Rett’s (2021) approach to emotive markers (e.g., alas, unfortunately); like these markers, THROW signals an agent’s evaluative attitude towards something in the discourse.6 However, we do not claim that THROW is necessarily emotive. We rather assume a notion of evaluativity in the spirit of, e.g., Ernst (2009: 512), where evaluatives include emotive expressions such as unfortunately and amazingly as well as less clearly emotive expressions such as mysteriously, conveniently, or appropriately – and see Degaetano-Ortlieb (2015) on a discussion of importantly and notably in the context of evaluativity.

Our proposal is that THROW signals a negative evaluation that amounts to dismissal. At its core, we take dismissal to consist of marking something as unimportant. There are in principle several ways of thinking about unimportance in discourse – for example, in terms of low expected utility (e.g. van Rooy 2003; 2004; Bergen et al. 2016; see Daniels 2019), or irrelevance to conversational goals, among other possibilities. Here, we will treat unimportance as a primitive.

2.2 Formal rendition of the analysis

We propose that the use of THROW is governed by the discourse conditions in (4). Note that the utterance un hosting THROW can be devoid of accompanying speech (which we write as …THROW), i.e., THROW has a speech-replacing (or pro-speech) use, as well as a speech-accompanying (co-speech) use, using the terminology introduced in Schlenker (2018a; b).

- (4)

- Discourse conditions for utterance un containing THROW:

- (i) a preceding utterance uk addresses a question Q

- (ii) un’s author considers the question Q unimportant

The analysis in (4) has two core components: a target question (Q) that THROW retrieves from the preceding discourse context, (4-i), and the attitude that THROW communicates regarding this target question, (4-ii). This question-based approach builds on the well-established view that utterances by and large (and, in particular, declarative utterances) evoke alternatives that amount to a question that is being answered (see, e.g., Roberts 2012; Büring 2003; Beaver & Clark 2008: 37).7 We remain agnostic as to whether the unimportance evaluation in (4-ii) is limited to the author, or whether the author conveys that people in general would consider this question unimportant – an issue that also arises for predicates of personal taste such as tasty or fun (see Lasersohn 2005; Stephenson 2007; Pearson 2013).

We will discuss both of the components in (4-i) and (4-ii) in turn, in Sections 2.3 and 2.4, respectively. Before doing so, we wish to highlight an important distinction between an utterance uk that provides the target question Q vs. an accompanying utterance ua, which combines with THROW to yield un (i.e., un = ua + THROW), illustrated in (5B1/5B2). When THROW occurs on its own, as in (6B), un = THROW.

- (5)

- (6)

The only utterance that is relevant for whether the discourse conditions in (4) are fulfilled is the preceding uk utterance, which we focus on in Sections 2.3–2.5. The absence of the accompanying ua utterance from (4) is by design; as we will see in Section 2.6, ua makes its discourse contribution independently from THROW, with the main restriction that the discourse contribution of ua cannot be at odds with the dismissal that THROW communicates, as we saw in example (3).

It is worth pointing out that a co-speech realization of THROW, where the gesture is synchronous with the accompanying utterance, can be hard to distinguish from a pro-speech (or pre-speech) realization where THROW precedes the accompanying utterance. These realizations are most easily distinguished in examples where the accompanying speech has a prosodic peak near the end of the sentence, as in (7). Here, a pro-speech THROW will be realized before I, as indicated in (7B1), whereas the stroke of a co-speech THROW will be aligned with the word containing the nuclear accent, baNAnas, as in (7B2) (see, e.g., Ebert et al. 2011). The two realizations appear to have identical effects in (7B1–B2).

- (7)

- A:

- I’m sorry there was nothing for dinner.

- B1:

- …THROW I ate baNAnas

- B2:

-

baNAnasTHROW

baNAnasTHROW

Going forward, when we probe for the semantic contribution of THROW, the most conservative approach is to look at THROW without an accompanying utterance, as the presence of an accompanying utterance will often trigger additional inferences. For instance, in (5B1), we infer that B’s dismissal is justified by the accompanying assertion that tomorrow is Sunday, which suggests that it does not matter if it gets late on a Saturday night. By contrast, in (5B2), we infer that B’s dismissal is justified by the accompanying assertion that it’s only 3am, which suggests that 3am does not count as late. These inferences are not contributed by THROW, nor does THROW operate on them in any meaningful way. They simply coalesce with the THROW contribution in the pragmatics. The inclusion of an accompanying ua utterance thus introduces a confound into an investigation of THROW proper. In Sections 2.3 and 2.5, we only consider uses of THROW without an accompanying utterance; in Section 2.4, we revisit predictions on the uk-ua interplay, and we return to ua in Section 2.6.

2.3 The target of THROW

We began with the informal intuition that THROW comments on something that has been said in the preceding discourse. There are in principle several ways to cash out this idea formally: we could say that THROW targets i) a proposition, ii) a question, or iii) a speech act. In (4), we have chosen option (ii), for the following reasons.

2.3.1 Comparing a question-based approach to a proposition-based approach

One reason to model THROW as commenting on a question (Q) rather than a proposition (p) is that THROW is not restricted to contexts where the previous discourse move was a (proposition-denoting) declarative, or makes a unique proposition salient; it can equally well respond to interrogatives denoting non-biased questions (i.e., sets of propositions). Taking THROW to evaluate the question addressed by a preceding utterance allows us to capture both kinds of cases in a uniform way. To see this, consider the following two contexts, (8) and (9), in which Q amounts to a polar question (p-or-not-p). If uk is a declarative with unmarked sentential stress, as in (8A1/8A2), its at-issue content is one of the two congruent answers to {p, ¬p}, as indicated in (8B); if uk is a polar question, as in (9A), it directly supplies {p, ¬p}, as indicated in (9B). In (8) and (9), uk is the utterance that immediately precedes the THROW utterance, but we will also see examples where this is not the case (specifically, example (30) in Section 2.6).

- (8)

- A1:

- Sam isn’t coming to the party.

- A2:

- Sam is coming to the party.

- B:

- …THROW (⤳ whether or not Sam is coming is unimportant)

- (9)

- A:

- Is Sam coming to the party tonight?

- B:

- …THROW (⤳ whether or not Sam is coming is unimportant)

By commenting on the question {p, ¬p} addressed by a declarative uk, as in (8), THROW indirectly comments on the proposition p contributed by uk. We make the following plausible assumption: If a question is unimportant, it follows that each of the answers it contains is also unimportant.8 This is why, when the preceding utterance is a declarative, THROW is often felt to be dismissing the proposition that the declarative expresses rather than the issue it addresses. We apply this reasoning to (8) as follows: both in response to (8A1) and in response to (8A2), B communicates (via THROW) that it is unimportant whether or not A is coming. B thereby implies that it is unimportant that A is not coming when responding to (8A1), and that it is unimportant that A is coming when responding to (8A2). The same reasoning applies to all examples in which THROW seems to directly dismiss a proposition.

A question-based approach is corroborated further by the observation that not just any proposition p that arises in the discourse can be dismissed by THROW in this indirect way. If uk is a declarative, we correctly predict that p must be the at-issue content of uk rather than, say, implicated or presupposed, since it is the at-issue content of declaratives that is generally taken to answer an implicit question (see, e.g., Beaver et al. 2017). This restriction is supported by discourses like (10), where A’s utterance plausibly makes salient (at least) the three propositions in p1—p3; we observe that B’s use of THROW can only be understood as dismissing the entailed proposition (p1) by communicating that {p1, ¬p1} is unimportant; it cannot be understood as dismissing p2 or p3. While this generalization would need to be stipulated under a proposition-targeting account, where p2 or p3 should also be accessible, it falls out for free on the view that THROW targets the question addressed by a preceding utterance.

- (10)

- A:

- I saw a cat under C’s car yesterday.

- p1 = A saw a cat under C’s car yesterday. (entailment)

- p2 = A did not see more than one cat under C’s car yesterday (implicature)

- p3 = C has a car. (presupposition)

- B:

- …THROW

- ⤳ B dismisses p1

-

B dismisses p2

B dismisses p2

-

B dismisses p3

B dismisses p3

Our analysis predicts that THROW should also be acceptable in response to wh-questions, as confirmed by (11); similarly, when THROW is used in response to a declarative with narrow focus, illustrated in (12), then the relevant Q can be retrieved by virtue of question-answer congruence (cf. Beaver & Clark’s 2008: 37 Focus Principle). This is in line with the general assumption that the set of alternatives denoted by a question, (11A), and the set of alternatives made salient by a possible answer to that question, (12A), are identical and generated by substituting other elements of the same type for the wh-element (who) or focus constituent (SamF), respectively (see, e.g., Rooth 1992). Therefore, the relevant alternatives for both (11A) and (12A) amount to {Sam told Mel about the party, Alex told Mel about the party, Ming told Mel about the party, …}.

- (11)

- A:

- Who told Mel about the party?

- B:

- …THROW

- (⤳ it is unimportant who told Mel about the party

- ≈ ‘who cares’, ‘it doesn’t matter’, …)

- (12)

- A:

- [SAM]F told Mel about the party!

- B:

- …THROW

- (⤳ it is unimportant who told Mel about the party

- ≈ ‘who cares’, ‘that doesn’t matter’, …)9

The ability to occur in response to wh-questions sets THROW apart from emotive markers that do in fact target propositions; such emotive markers can only comment on questions that make a unique proposition salient (Rett 2021: 317). The lack of such a requirement for THROW lends further credence to the view that THROW comments on questions rather than propositions.

It is worth noting that (11) further corroborates the observation in (10), that THROW targets at-issue content. It is commonly assumed that wh-questions trigger an existential presupposition, i.e., (11A) has the presupposition that someone told Mel about the party (see Katz & Postal 1964; Keenan & Hull 1973, and much subsequent work). In parallel to (10), (11B) seems to lack a reading where THROW targets this existential presupposition, thereby communicating that it is unimportant whether someone told Mel about the party.

We predict that THROW will be acceptable in response to any discourse move that addresses a question. For example, imperatives can be taken to address a decision problem (i.e., a question of the form What should x do? – see Kaufmann 2012); thus, THROW can be used felicitously as in (13B) to convey B’s indifference to the obligation assigned to them by A’s imperative.

- (13)

- A:

- Be careful!/Clean your room!/Don’t forget to call your mother!

- B:

- …THROW

- Possible interpretations:

- ⤳ it is unimportant what I should do

If there are multiple questions that an utterance could in principle address, we expect THROW to be able to target each of them. An example that fits this profile is given in (14).

- (14)

- A:

- Nobody told me that there’s a party today.

- B:

- …THROW

- Possible interpretations:

- i. ⤳ it is unimportant whether there’s a party today

- ii. ⤳ it is unimportant whether anybody told A that there’s a party today

Here, the embedded clause in A’s utterance makes salient the question of whether there is a party today, giving rise to the interpretation in (14i), while the matrix clause makes salient the question of whether anyone told A about the party, in line with (14ii). In the absence of disambiguating speech, THROW can be interpreted as dismissing either of these questions. In Section 3, after discussing the core cases, we will resume our discussion of the preceding utterance uk by reviewing cases in which the speakers themselves utter uk (Section 3.1) and cases in which uk seems to be absent altogether (Section 3.2).

2.3.2 Comparing question dismissal to speech-act dismissal

One might wonder whether THROW could be characterized more generally as targeting a preceding speech act, option (iii) at the beginning of this section. On this view, THROW would target different objects in (8), (9), and (13) – an assertion, a question, and a warning/command/advice, respectively. There are several features that make an analysis in terms of speech acts unattractive. Firstly, while questions are clearly defined semantic objects (sets of propositions) that can be targeted by THROW, a comparable definition for speech acts as targetable semantic objects is missing (see Harris et al. 2018 for a recent survey of the varied theoretical landscape on speech acts); it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a complete analysis of what speech acts are, and which semantic objects they deliver to the discourse. Secondly, it is well known that a single utterance can perform multiple speech acts. For example, the interrogative utterance in (15) can be used to perform both a direct speech act of questioning and an indirect speech act of requesting.

- (15)

- Context: A and B are sitting at opposite ends of a rectangular table at a conference dinner; Sam can reach the salt and is sitting closer to A than B.

- A:

- Can you pass the salt?

- Direct speech: question

- Indirect speech act: request

- B:

- …THROW

- i.

- ⤳

- it doesn’t matter whether I can pass the salt (e.g. because Sam can pass the salt to you; or because I have decided not to pass it to you)

- ii.

- it doesn’t matter that/whether you are asking me to pass the salt to you

If THROW targeted speech acts, we might expect its contribution in (15) to be ambiguous, but this is not the case; B’s use of THROW can only be interpreted as conveying that whether B can pass the salt is unimportant, (15B-i). The absence of the request-targeting reading (15B-ii) is brought out by (16). While it is possible for B to answer A’s question affirmatively while rejecting the indirect speech act, as in (16B1), the same speech-act rejection cannot be achieved by virtue of THROW, as illustrated in (16B2).

- (16)

- A:

- Can you pass the salt?

- B1:

- Yes, I can. But I won’t.

- B2:

- #

canTHROW

canTHROW

Although we could in principle stipulate that THROW only targets direct speech acts, its non-ambiguity in (15) falls out for free if THROW targets questions. In a similar vein, it is possible to construct examples with imperatives where THROW clearly does not target a speech act. For example, in (17), A’s utterance performs the speech act of warning; the use of THROW in (17B1) is not interpreted as conveying that B considers it unimportant that A has warned B to avoid a salient area at night. Instead, THROW is interpreted as conveying that B considers it unimportant whether B should do so, as brought out by the contrast in (17B2) vs. (17B3). This is precisely the reading that is predicted on the question-targeting account.

- (17)

- A:

- Avoid this area at night!

- Speech act: warning

- B1:

- …THROW

- Question addressed (cf. (13)): What should B do?

- B2:

-

outTHROW at night anyway

outTHROW at night anyway - ⤳ it doesn’t matter whether I should avoid this area at night

- B3:

- #

warnedTHROW me, so I absolutely will.

warnedTHROW me, so I absolutely will. -

it doesn’t matter that/whether you are warning me to avoid this area

it doesn’t matter that/whether you are warning me to avoid this area

In the remainder of this paper, we will focus on dialogues where the preceding utterance uk is a polar question, as in (9), or a declarative with neutral sentential stress, as in (8), for ease of exposition. Having established how THROW retrieves its attitudinal target, we can now zoom in on the attitude that THROW communicates.

2.4 The evaluative attitude expressed by THROW

Let us review the details of how the proposal applies when THROW responds to a declarative. In (3), repeated here as (18), A’s assertion of I think I forgot to pay my credit card bill addresses the question {A forgot to pay A’s credit card bill, A didn’t forget to pay A’s credit card bill}. B1’s response of It’ll be fine contextually entails that whether or not A paid their bill is not a serious issue. These are precisely the discourse conditions that make THROW felicitous in (18B1). On the other hand, the response of That’s not good in (18B2) affirms that forgetting to pay a bill is a serious matter; this is in conflict with what THROW requires, hence THROW’s infelicity. While some combinations of THROW and accompanying utterances may simply trigger a search for an explanation of why the gesturer uttered the accompanying speech (see example (29B2) in Section 2.6), such an explanation is out of reach in (18B2) due to the incompatibility of the gestural content and the speech content. When THROW is not accompanied by speech, as in (18B3), it contributes an underspecified dismissive attitude non-exhaustively paraphrasable as don’t worry or who cares.

- (18)

- A:

- Ack! I think I forgot to pay my credit card bill. (= p)

- B1:

-

fineTHROW

fineTHROW

- B2:

- #

goodTHROW

goodTHROW

- B3:

- …THROW ( ⤳ {p, ¬p} is unimportant ≈ ‘don’t worry’, ‘who cares’, …)

When the preceding utterance is a polar question, as in (19), repeated from (9), the analysis works exactly the same way, except that the question dismissed by THROW is overtly pronounced by A. Here, THROW dismisses A’s question rather than answering it; B’s gesture cannot be construed as providing a negative answer to A’s question (i.e., THROW cannot mean ‘no’ in (19)).

- (19)

- A:

- Is Sam coming to the party tonight?

- B:

- …THROW

- (⤳ {p, ¬p} is unimportant

- ≈ ‘Who cares about him?’, ‘Who cares about parties?’, etc.)

As in (19B3), the precise flavour of the dismissal contributed by THROW is underspecified in the absence of speech. In (19B), in particular, the source of unimportance is underspecified; it could be that B does not care about B’s husband, but it could also be that B does not care about parties, among other conceivable readings.

The proposed analysis predicts that THROW will generally be incompatible with accompanying ua utterances expressing sincere interest or concern about the targeted issue. This is exemplified by the infelicity of THROW in (20B) below.

- (20)

- A:

- I think I’m going to quit my job.

- B:

- #

newsTHROW tell me more!

newsTHROW tell me more!

Likewise, THROW is inappropriate (or at best extremely rude/flippant) in situations where weighty matters are under discussion and discourse participants are expected to treat what is said as important. For example, consider (21), where A is a police officer interviewing B as a suspect in a serious crime,10 or (22), where A is performing a sincere, well-planned marriage proposal to their partner B.11

- (21)

- A:

- Did you murder Professor Plum?

- B:

- Yes/No#THROW

- (22)

- A:

- Will you marry me?

- B:

- Yes/No#THROW

In this section, we have already raised the issue of underspecification and interpretational flexibility when it comes to the sources of unimportance. We now present a case study that further elaborates on these.

2.5 Underspecification/flexibility of unimportance

There are many possible sources of unimportance. The proposed analysis is compatible with this flexibility; a THROW dismissal may take on flavours of indifference, (indirect) denial, etc. depending on the context. For example, B’s use of THROW in (23) will, all else being equal, most naturally be interpreted as dismissing the question addressed by A’s assertion on the grounds that B believes A’s answer to be obviously false, and thus highly uninformative (cf. an utterance of nah, no way, or whatever, man).

- (23)

- Context: A is staying at B’s place. B owns a dog, and both A and B know that the dog is not allowed into B’s bedroom.

- A:

- Your dog is lying on your bed.

- B:

- …THROW

If, however, we adjust the context as in (24) so that B has, exceptionally, allowed the dog into the bedroom, B’s use of THROW can instead be interpreted as dismissing the question of whether the dog is on B’s bed as unimportant because both answers are compatible with B’s rules that day, and thus neither answer is noteworthy (cf. an utterance of yeah, I know or it’s fine).

- (24)

- Context: A is staying at B’s place. B owns a dog, and both A and B know that the dog is not allowed into B’s bedroom. However, today there are contractors working in B’s kitchen and so, unbeknownst to A, B has temporarily suspended the bedroom rule.

- A:

- Your dog is lying on your bed.

- B:

- …THROW

Crucially, when THROW communicates the denial of p (as in (23)), we predict that it does so by way of dismissing p – e.g., on the grounds that it is obviously false. This is supported by the observation that THROW cannot be used to provide a direct negative answer (≈ no) to a polar question in examples such as (9) above, as spelled out explicitly in (25). To the extent that (25B) may imply that Sam is not coming, this would once again be a case of dismissing nonsense (≈ whether Sam is coming or not is unimportant, because it is obviously false), parallel to (23).

- (25)

- A:

- Is Sam coming to the party tonight?

- B:

- …THROW (≠ No, he is not coming.)

2.6 Illocutionary independence of THROW

An important feature of our analysis that we have not yet explicitly discussed is the independence of THROW from the utterance ua that it accompanies (if there is one). We propose that this is a virtue of our analysis, since THROW appears to encode an illocutionary act that is separate from any accompanying speech, giving rise to an interpretation along the lines of Krifka’s (2001) speech act coordination. THROW can be accompanied by ua utterances with a variety of clause types, and it behaves uniformly regardless of what spoken content (if any) it accompanies. This is illustrated in (26); in each of B’s responses, THROW appears to dismiss A’s observation that B’s phone buzzed (the uk) as unimportant.

- (26)

- A:

- Your phone buzzed.

- B1:

-

laterTHROW

laterTHROW

- B2:

-

sayingTHROW something?/

sayingTHROW something?/ talkingTHROW about?

talkingTHROW about?

- B3:

-

IgnoreTHROW it/

waitTHROW

waitTHROW

- B4:

- PfftTHROW/EchhTHROW

- B5:

- …THROW

Our analysis of THROW in (4) holds that THROW does not directly interact with or operate on the accompanying ua utterance. Given the different semantic properties of, say, declaratives (26B1), questions (26B2), and imperatives/hortatives (26B3) (see, e.g., Portner 2004), the flexibility of THROW to combine with more or less any type of ua utterance corroborates this approach by making it implausible that THROW comments on the ua utterance that it accompanies. THROW thus crucially differs from the iconic gestures that Schlenker (2018a; b) discusses in that it does not seem to give rise to any non-trivial interactions with accompanying speech. To see this, consider (27); the intended, but unavailable, reading is loosely modelled after Schlenker’s cosuppositional readings, where the contribution of THROW would be conditionalized on a positive answer to B’s question. However, such a use of THROW, in which it would compositionally interact with the question operator in the form of the non-trivial projective behaviour that (27B-i) spells out, is impossible.

- (27)

- A:

- Alex can’t come to your birthday party.

- B:

-

SamTHROW coming?

SamTHROW coming?

- i.

- intended, but unavailable:

- if Sam is coming, then it is unimportant whether or not Alex is coming

- ii.

- available:

- [it is unimportant whether or not Alex is coming] and [I am asking you if Sam is coming]

The unavailability of the reading in (27B-i) sharply contrasts with the availability of that in (27B-ii). In the latter, THROW’s contribution is pragmatically conjoined with B’s request for information about whether something else is the case (namely: Is Sam coming?), giving rise to the speech act coordination [it is unimportant whether or not Alex is coming] and [I am asking you if Sam is coming]. We may intuit that B conveys a causal link along the lines of because Sam might be/is coming, it is unimportant whether or not Alex is coming, but this is plausibly an inference based on standard pragmatic reasoning, possibly involving discourse relations (see, e.g., Hobbs 1979; Lascarides & Asher 1993; Kehler 2002; Asher & Lascarides 2003; Jasinskaja & Karagjosova 2020; see also Lascarides & Stone 2009a; b; Hunter 2019 on the role of discourse relations in gesture-speech interaction). Crucially, no compositional interaction between THROW and the ua is required to derive this effect. Parallel reasoning applies to the interpretation of (28), the declarative variant of (27).

- (28)

- A:

- Alex can’t come to your birthday party.

- B:

- SamTHROW is coming!

- (available: it is unimportant whether or not Alex is coming)

Example (29) further illustrates indirect interactions between THROW and the accompanying utterance ua. Here, the inferred discourse relations (see, e.g., Hobbs 1979; Lascarides & Asher 1993; Kehler 2002; Asher & Lascarides 2003; Jasinskaja & Karagjosova 2020) between A’s utterance and B’s utterance impact the combinability of ua with THROW, as illustrated in (29). In (29B1), the inclusion of only signals a disagreement between B and A, indicating the discourse relation Contrast; this disagreement is compatible with the dismissal that THROW communicates, and in fact supports B’s dismissal of A’s statement. By contrast, the spoken utterance in (29B2) elaborates on A’s utterance without a clear sense of contrast, indicating the discourse relation Elaboration. We maintain that THROW is in fact acceptable in (29B2) as well, but the orthogonal contributions of THROW and the accompanying ua (= it’s 3am) trigger a search for an explanation: why did B elaborate on A’s statement by asserting it’s 3am while at the same time expressing dismissal by means of THROW? This gives rise to a slight oddness of (29B2), indicated by the single question mark.

- (29)

- A:

- B1:

- B2:

- It’s getting late.

-

3amTHROW

3amTHROW

- ?

3amTHROW

3amTHROW

- Discourse relation (A-B1): Contrast

- Discourse relation (A-B2): Elaboration

If THROW encodes a separate illocutionary act that is interpreted in conjunction with the illocutionary act associated with an accompanying utterance, this makes further predictions about the type of speech that THROW can accompany. Specifically, we expect THROW to accompany main clause material and not embedded speech. No such requirement holds for the preceding uk utterance, as we saw in (14). Predicted exceptions are cases where THROW accompanies speech below the root-clause level that has illocutionary force in its own right, and thus hosts ‘embedded root clause phenomena’.

This prediction is confirmed by the distribution of THROW when it accompanies the antecedents of factual vs. hypothetical conditionals. Factual conditionals presuppose that someone believes that the antecedent proposition is true (Iatridou 1991, Haegeman 2003); on the basis of such observations, the antecedent of a factual conditional has been argued to possess illocutionary force separate from that of the consequent (see, in particular, Haegeman 2003: 334–336, who argues, building on Declerck & Reed 2001, that such antecedents “echo someone else’s speech act”). THROW is acceptable when accompanying the antecedents of factual conditionals, as illustrated in (30), but not in connection with the antecedents of hypothetical conditionals like (31), which lack this special property.12

- (30)

- A:

- There’s a typo in my handout.

- B:

- No one will notice.

- A:

- If

noticeTHROW, then I’ll just leave it as it is.

noticeTHROW, then I’ll just leave it as it is.

- (31)

- A:

- There’s a typo in my handout. Can you take a look at it? If

notice#THROW, then I’ll just leave it as it is. But if it’s noticeable, I’ll go and correct it.

notice#THROW, then I’ll just leave it as it is. But if it’s noticeable, I’ll go and correct it.

In this respect, THROW resembles a range of speaker-oriented natural language expressions (see, e.g., Green 1976: 383–384; Repp 2013; Grosz 2020), which are restricted to root contexts in the sense of Hooper and Thompson (1973). An illustration is given in (32), where (32a) is a factual conditional, which allows for German schon in its discourse particle reading, while the hypothetical conditional in (32b) disallows it. The THROW examples (30) and (31) mirror the (32a)–(32b) distinction.

- (32)

- German (Brauße 1994: 112)

- a.

- Wenn

- if

- es

- it

- schon

- schon

- Frost

- frost

- gibt,

- gives

- könnte

- could

- es

- it

- wenigstens

- at.least

- auch

- also

- schneien.

- snow

- ‘If there is frost [as we know], it could at least snow as well.’

- b.

- Wenn

- if

- es

- it

- (*schon)

- (*schon)

- Frost

- frost

- gibt,

- gives

- erfrieren

- freeze

- die

- the

- Rosen.

- roses

- ‘If there is frost, then the roses freeze.’

Note that in (30) THROW does not appear to dismiss the question addressed by B’s immediately preceding utterance of no one will notice (which also happens to be the question addressed by the antecedent proposition of the conditional uttered by A). Instead, A plausibly dismisses the question whether there is a typo in A’s handout or not, which A had addressed earlier.13 As a consequence, A’s use of THROW in (30) makes the same communicative contribution that B would make in (33), quite parallel to our earlier example (3). Here, the statement that no one will notice can be pragmatically construed as the explanation for why the presence/absence of a typo is unimportant.14

- (33)

- A:

- There’s a typo in my handout.

- B:

-

noticeTHROW

noticeTHROW

- (⤳ it is unimportant whether there is a typo in your handout or not)

2.7 Non-at-issue status

Since THROW encodes a separate illocutionary move (making its own contribution to the discourse), we predict that it shares properties with other discourse-managing devices that have been given similar analyses. This prediction has already been confirmed by our comparison of THROW and German discourse particles in examples (30)–(33), which showed that both exhibit a restriction against accompanying—or occurring in—embedded (non-root) clauses. We proceed to show that, like German discourse particles, English emotive markers (e.g., Rett 2021) and a range of other expressives (e.g., Gutzmann 2013), the contribution of THROW cannot be targeted by direct denials, i.e., denials by virtue of No, … or That’s not true, … The response in (34A1) can directly deny the truth-conditional content of (34B)’s speech, but it is not possible to use (34A2) for directly denying the dismissal conveyed by the THROW gesture in (34B). However, the dismissal conveyed by THROW can be targeted in the same way in which other non-at-issue meanings can be targeted, e.g., by virtue of Hey, wait a minute! (see Shanon 1976 and von Fintel 2001), or its short form Hey!, in (34A3); these have been argued to target “a wide range of non-at-issue meanings” (Potts 2012: 2521).

- (34)

- A:

- Did you remember to pay the electricity bill?

- B:

- YeahTHROW

- A1:

- That’s not true; I looked at the account just now, and there’s been no payment!

- A2:

- #That’s not true; (you think that) this is serious/important/worth discussing!15

- A3:

- (Hey!) This is really important!

The unacceptability of (34A2) confirms that THROW encodes non-at-issue meaning. In Rett’s (2021) terms, THROW encodes illocutionary non-at-issue meaning (in contrast to descriptive non-at-issue meaning), in that it encodes an agent’s attitude toward some descriptive content in the discourse.

3 Extension to further uses

3.1 Self-directed uses

The analysis spelled out in (4) does not require that the preceding utterance (uk) is uttered by someone other than the individual who produces THROW. This is desirable, because THROW can be used in monologues like (35).

- (35)

- It’s getting late. Ech,

hurtTHROW

hurtTHROW

Here, as in the dialogues examined in Section 2, the speaker’s use of THROW with the second sentence dismisses the importance of the question addressed by the first. The speaker signals (to themself) that whether it is getting late or not is unimportant; this is presumably because, as they go on to assert, staying up for another half hour will not be harmful. In this way, the speaker raises a fact that could in principle serve as motivation for going to bed; upon consideration, they decide that the lateness issue is unimportant, and so THROW is licensed. The dialogue case in (36) seems to exhibit the same behaviour.

- (36)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

- B:

- Ech,

hurtTHROW

hurtTHROW

The distribution of THROW in monologues thus further supports our analysis; we now take this as our cue to explore what appear to be discourse-free uses in the next section.

3.2 (Apparently) discourse-free uses

The discourse conditions in (4) make reference to a prior utterance. We specified that there does not need to be an overtly expressed utterance ua that accompanies THROW; this was necessary to account for cases of pro-speech THROW (i.e., cases where THROW is produced without accompanying speech). In this subsection, we note that the preceding utterance uk that supplies the question dismissed by THROW may likewise be phonologically empty. To see that this is needed, consider an example like (37).

- (37)

- Context: A is carrying a pile of dirty clothes from the hamper to the washing

- machine. A looks back and notices that they have dropped a sock.

- A: …THROW

Here, THROW is perfectly felicitous despite the absence of an overt preceding uk utterance. This can easily be understood as the self-directed use of THROW outlined in Section 3.1 combined with silent self-talk. If, as Eckardt & Disselkamp (2019) argue, speakers use language in their internal cognitive processes, it should not surprise us that THROW can target the resulting silent utterances. Plausibly, the speaker’s internal monologue in (37) looks something like this:

- (38)

- Context: A is carrying a pile of dirty clothes from the hamper to the washing machine.

- A looks back and notices that they have dropped a sock.

- A:

- Oh, I dropped a sock.

- A:

- …THROW (⤳ whether or not I dropped a sock is unimportant)

With the internal monologue filled in, A’s use of THROW is no longer surprising; it dismisses the current location of the sock as an unimportant issue.

3.3 Insincere uses

Like other meaningful expressions, THROW need not be used sincerely. Depending on the context and the content of the utterance that it accompanies, THROW can be deployed to produce irony, humour, or politeness. Since THROW is by its very nature a negatively evaluative expression, we expect irony to give rise to a positive meaning, much in line with ironic compliments (i.e., negative remarks such as you really did do an awful job that are used ironically for giving praise; see Kreuz & Glucksberg 1989; Kreuz & Link 2002, and Giustolisi & Panzeri 2021: 293 for recent discussion).

While THROW is not used to give compliments, one environment where THROW is particularly common is in response to compliments, as in (39).16 The intuition about such examples is that B accepts the compliment but uses THROW to display modesty.

- (39)

- A:

- You’re really great, you know.

- B1:

-

shucksTHROW

shucksTHROW

- B2:

-

youTHROW

youTHROW

- B3:

-

pfft/pshTHROW

pfft/pshTHROW

- B4:

- AwwTHROW

- B5:

- …THROW

In each of B’s responses, the use of THROW strictly speaking requires that B considers the question of whether they are great to be unimportant. If sincere, this dismissal of A’s compliment would be rather rude. However, it is most naturally understood here as a form of polite pretence; modesty demands that we minimize praise of ourselves. In this case, B’s use of THROW can be seen as a violation of Grice’s (1975) Maxim of Quality (part of the Cooperative Principle) to satisfy Leech’s (1983) Maxim of Modesty (part of the Politeness Principle).17

Another environment where ironic uses of THROW show up is in greetings where the pretended dismissal via THROW is interpreted as an intimacy-generating device, as illustrated in (40). Here, Sam’s use of THROW once again literally dismisses (the question raised by) Alex’s discourse-initial utterance; yet instead of creating a social rift, it seems to serve as a term of endearment. What happens here is very much like the interaction in (41), where Sam’s use of you old devil in (41b) should literally insult Alex but instead serves as a friendly epithet. Note that THROW can be added to this response quite naturally, as in (41c).

- (40)

- a.

- Alex: Hey, it’s good to see you Sam!

- b.

- Sam:

Alex!THROW How have you been?

Alex!THROW How have you been?

- (41)

- a.

- Alex: Hey, it’s good to see you Sam!

- b.

- Sam: Alex, you old devil! How have you been?

- c.

- Sam:

devil!THROW How have you been?

devil!THROW How have you been?

THROW differs from other gestures, including in particular facial expressions, which are known to signal that accompanying speech is to be interpreted ironically (Giustolisi & Panzeri 2021). Such an effect is illustrated in (42), where SICK-FACE stands for a facial expression signalling physical disgust (see Yoder et al. 2016: 303) which thus conveys that the accompanying assertion of tastiness is insincere. By contrast, in (39)–(41), the contribution of THROW itself is understood to be insincere – that is, the dismissal that THROW communicates is to be understood in an ironic way (as appreciation).

- (42)

- This food is deliciousSICK-FACE

This reverse behaviour of gesture and speech with regards to irony can be made even clearer in (43), a variant of (39). Here, THROW does not mark that B’s statement that A is a darling is insincere. In fact, the opposite is the case: B’s statement that A is a darling serves to mark that B’s use of THROW is insincere. To our knowledge, this behaviour of THROW is systematic.

- (43)

- A:

- You’re really great, you know.

- B:

- Oh,

darlingTHROW

darlingTHROW

For present purposes, we here conclude our discussion of the behaviours of THROW and return to a separate issue, flagged in Section 1, namely the question of whether there are natural language counterparts of THROW, and how they compare in their meaning contribution and use.

4 Comparison to spoken material

The notion of discourse management is not new; there are a variety of elements of spoken language – whether spoken morphemes, covert operators, syntactic configurations, or intonational melodies – that have been argued to contribute information about how a discourse participant relates to the content of the discourse. This class includes illocutionary and discourse-managing operators, which signal the speaker’s goals/intentions for how the discourse should develop (e.g., ASSERT, VERUM, FALSUM; see Romero & Han 2004; Krifka 2008; Repp 2013; Cohen & Krifka 2014; Krifka 2017; Frana & Rawlins 2019, i.a.). This class also includes emotive markers, which signal the speaker’s emotive attitude toward a proposition (e.g., mirative intonation, Finnish -pä, English alas, fortunately; see Rett 2021).

Of these, our analysis most closely resembles that of Rett (2021), with the difference that THROW encodes a non-emotive evaluative attitude (dismissal) rather than an emotive attitude (e.g., regret, disappointment, surprise). Rett’s analysis is couched in a version of Farkas & Bruce’s (2010) Table model, with the notion of discourse commitments expanded to capture non-doxastic attitudes. Rett (2021: 330) proposes that the presence of the emotive marker alas, (44), for a sentence S with content p and author a, adds to a’s public discourse commitments the commitment that a is disappointed that p.

- (44)

- Alas, Jane lost the race. (Rett 2021: 328)

An important difference between THROW and alas is the obligatory illocutionary independence of the former from material that it accompanies, which was discussed in Section 2.6. This, in itself, is not a hindrance to comparing the two approaches, since Rett also allows for dialogic uses of alas, illustrated in (45). The effect of alas in (44) and (45B) is equivalent; it conveys that the speaker is disappointed that Jane lost the race. This indicates that it must be possible for the content p that alas targets to be part of the preceding discourse.

- (45)

- A:

- Jane lost the race.

- B:

- Alas! (Rett 2021: 329)

Freestanding uses of THROW behave much like freestanding uses of alas; however, THROW is unable to do what alas does in (44). This is illustrated by the fact that (47) is not equivalent to (46B); in (47), unlike (46B), THROW cannot be understood to be commenting on the importance of whether or not it is getting late. Rather, (47) would have to respond to some preceding utterance (uk) that is dismissed on the basis of it getting late. What (47) emphasizes is a property that sets THROW apart from other discourse-managing devices: its lack of interaction with the spoken material (ua) that it accompanies. As discussed in Section 2.6, discourse-managing THROW does not comment on the information associated with the co-occurring utterance.

- (46)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

- B:

- …THROW (⤳ whether or not it’s getting late is unimportant)

- (47)

-

lateTHROW (not equivalent to (46B))

lateTHROW (not equivalent to (46B))

A natural language expression that seems to pattern like THROW in this respect is the interjection pah (IPA: [pʼaʰ]), as illustrated by the non-equivalence of (48B) and (49).18 Both THROW and pah thus fundamentally differ from discourse particles and interjections of the alas-type, which typically operate on the proposition encoded by their accompanying utterance.

- (48)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

- B:

- Pah! (⤳ whether or not it’s getting late is unimportant)

- (49)

- Pah, it’s getting late. (not equivalent to (48B))

Moreover, the parallels between THROW and pah also concern their semantic contribution. Like THROW, pah appears to contribute dismissal, and like THROW, pah dismisses something that precedes the utterance hosting it. This is illustrated in (50) below; (50B1) below is a near-equivalent of our earlier example (3B1). Moreover, (50B2) is as deviant as the corresponding (3B2) example.

- (50)

- A:

- Ack! I think I forgot to pay my credit card bill.

- B1:

- Pah, it’ll be fine.

- B2:

- #Pah, that’s not good.

As far as we can tell, pah is the closest English-language counterpart to the THROW gesture (with further candidates in who cares, whatever and so what in their uses as conventionalized discourse markers).

- (51)

- Doctors? Pah! Doctors are for wusses.

- (web blog; stored in COCA and retrieved on Dec. 7, 2021 from https://www.escapeartistes.com/2012/07/11/just-a-tummy-bug/)

If we allow Rett’s “sentence S” to be a preceding utterance uk addressing a question Q, our analysis can be translated into Rett’s (2021: 330) terms as follows: for an author a and a sentence S that addresses the question Q, THROW (and, in parallel, pah) adds to a’s public discourse commitments the commitment that a dismisses Q (or, equivalently: that a considers Q unimportant). Note, in this connection, that our choice of treating unimportance as a primitive in the statement that a considers Q unimportant (cf. Sections 2.1 and 2.2) is comparable to Rett’s approach, which takes a is disappointed that p as a primitive.

To conclude this section, a reader may wonder if the content contributed by THROW exhibits properties attested for more familiar linguistic content, such as a discourse participant’s ability to make reports about the content that THROW contributes, the possibility to refer to this content with a propositional anaphor, or scope interactions with natural language operators such as quantifiers or negation. Based on the parallels discussed in this section, we expect that the respective properties of THROW are quite similar to those of the expressive interjection pah. As far as we can tell, this expectation is confirmed. In (52), A is reporting to C on the dismissive content of B’s THROW/pah utterance.

- (52)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

- B:

- …THROW/Pah!

- A turns to C:

- I can’t believe that B just plainly dismissed the issue/question of whether it is getting late!

In contrast, example (53) shows that the content of THROW/pah cannot be picked up by the propositional anaphor that (see e.g. Webber 1988; Asher 1993; Asher & Lascarides 2003; Krifka 2013; Snider 2017).

- (53)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

- B:

- …THROW/Pah!

- A:

- #You don’t know that.

- (intended: ‘You don’t know that it’s unimportant whether it’s getting late.’)

Finally, in line with comparable expressives discussed by Gutzmann (2013), such as ouch, oops and oh, there is no evidence that THROW/pah scopally interact with natural language operators.

5 Discussion and conclusions

5.1 Summary of main findings

This paper has analyzed the THROW gesture as an operator that marks discourse objects (namely questions) as unimportant. It contributes to a growing body of work that applies formal linguistic tools to the study of meaningful gesture (e.g., Lascarides & Stone 2009a; b; Ebert & Ebert 2014; Schlenker 2018a; b; Esipova 2019). However, most formal semantic work in this area has focused on deictic and iconic gestures, with notable exceptions including Ippolito’s (2019) work on the gestural marking of non-canonical questions in Italian, Francis’ (2021) work on gestural objection to discourse moves, and Laparle’s (2021) work on the gestural tracking of discourse topics. We thus take the present work to be part of a much needed filling-in of the theoretical landscape of pragmatic gesture uses. Such formal semantic work on gestures like THROW complements the rich work on pragmatic gesture that has long been underway in other traditions, including Bavelas et al. (1992), Kendon (1995), Müller (2004), Sweetser & Sizemore (2008), Wehling (2017), Cooperrider et al. (2018), and many others.

In addition to providing us with a better picture of how language works in its full multimodal form, the particular evaluative meaning conveyed by THROW is not like other discourse-level meanings that have been described in the formal semantics literature as of now. This paper has presented what is, to our knowledge, the first semantic analysis of a gestural dismissal operator in natural language. Moreover, the proposed meaning is not only expressed gesturally; the striking parallelism between THROW and pah suggests that this meaning is also encoded in spoken language. This dismissal meaning is special among discourse-management operators in that it cannot interact with spoken material that it accompanies; THROW and pah operate on discourse objects (questions) but cannot comment on the discourse object that hosts them (i.e., on the accompanying speech). This obligatory illocutionary independence raises an important question for future research; why do dismissal operators have this property when other discourse-management operators (such as VERUM, discourse particles, alas and fortunately) do not?

5.2 Towards a broader understanding of dismissal operators

We have argued that THROW and pah convey a very general kind of dismissal. This is not the only dismissal meaning that natural language could encode; there could be other operators in this semantic field encoding more specialized flavours of dismissal (e.g., relating to the source of unimportance), targeting different kinds of semantic objects, combining dismissal with other meaning components, or making their contribution in an at-issue fashion. Future work that examines a broader array of dismissal operators will hopefully allow us to pinpoint which of the properties identified here are unique to THROW/pah and which belong to this semantic class more generally. For example, one might imagine that the puzzling illocutionary independence of THROW/pah is a consequence of their meaning. Perhaps it is not useful to dismiss one’s own utterance; if one believes that a question is unimportant, it may not be fully cooperative to address it. However, preliminary investigation suggests that the picture may not be so simple. For example, English shm-reduplication (e.g., table-shmable; see, e.g., Nevins & Vaux 2003; Grohmann & Nevins 2004) appears to comment on its base, in contrast to the illocutionary independence of question-targeting THROW and pah. This is illustrated by (54), where table-shmable seems to convey something along the lines of who cares about tables? (rather than who cares whether Sam is building a table?, though this may be implied). It is an open question whether B’s dismissal targets the stem table- in B’s own utterance or the previous occurrence of table in A’s utterance.

- (54)

- A:

- Sam is building a table.

- B:

- Table-shmable! Call me when Sam has built something worthwhile.

As we consider (54), we observe that THROW/pah have a parallel use. This paper explicitly limited its scope to uses of THROW that accompany or replace entire utterances, as these uses strike us as distinct from uses in which THROW attaches to a word or phrase (see footnote 2). Turning our gaze to the latter, we observe that both (pro-speech) THROW and pah have uses in which they follow a single word, and which pattern exactly like shm-reduplication, in (55B1) and (55B2), respectively. Here, THROW/pah seems to dismiss the noteworthiness of table in the given context, paralleling what we saw in (54). Numerous examples of the sort in (55B2) can be found in large corpora such as Google Books, e.g., for strings such as “computers, pah”, “progress, pah”, or “intelligence, pah”, among many others. Such uses of THROW/pah are potentially distinct from the ones we analyzed in this paper in that their dismissal always seems to target the accompanying material (i.e., the word that precedes them); however, a unified analysis may still be possible, which treats (55B1) on a par with the equally echoic (30), in that THROW in (55B1) comments on the question is Sam building a table? Regardless, we conjecture, based on the parallels between (54) and (55), that the correct analysis of the semantics of shm-reduplication (whichever that may be) can be unified with the analysis of examples of the type in (55).19

- (55)

- A:

- Sam is building a table.

- B1:

- Table! …THROW Call me when Sam has built something worthwhile.

- B2:

- Table, pah! Call me when Sam has built something worthwhile.

Other items in spoken English that may plausibly encode dismissal include discourse markers such as whatever (see, e.g., Kleiner 1998; Benus et al. 2007), meh (see, e.g., Schultz 2019: 5), hmpf (see e.g. Hougaard 2019: 102), and the doubled response particle yeah yeah, to name a few. With an analysis of THROW in hand, we are now in a better position to conduct fine-grained comparisons between operators within this semantic field.

This paper represents a first step toward understanding this kind of meaning; there is, of course, much more to do. For example, we have restricted our investigation to cases where THROW responds to declaratives and questions; it remains to be seen how the analysis can be adjusted to deal with cases where THROW responds to other kinds of discourse moves (e.g., imperatives, exclamatives). While we have so far treated pah as a spoken equivalent to THROW, further investigation is needed to determine whether they do in fact pattern together in all environments. Finally, THROW’s status as a pragmatic manual gesture means that it is articulatorily possible for it to coincide with other gestures (e.g., facial expressions)20 and spoken pragmatic operators (e.g., discourse and emotive markers); how the discourse-management labour is divided among these channels is an open question.

Notes

- Because THROW is a manual gesture, it can in principle combine with a variety of facial gestures. To isolate THROW’s contribution, we attempted to focus our investigation on cases where this gesture is accompanied by a (relatively) neutral facial expression, similar to the example at this URL (last accessed on 27 December 2021): https://giphy.com/gifs/latenightseth-seth-meyers-late-night-lnsm-H3arX25535xQ6ETguW. Depending on the context, this may not always be achievable; see also footnote 20 on uses of THROW that are accompanied by a smile. [^]

- See Bressem & Müller (2017: 5) for a possibly different use of the throwing away gesture co-occurring with phrases below the clause level; they argue that, for example, a use of THROW accompanying the numeral phrase two years signals that the exact duration spelled out by the accompanying speech is irrelevant. It should be noted, however, that they do not provide the preceding discourse context for this example, so it is not clear that this case could not be captured under our analysis. [^]

- An anonymous reviewer raises the question of whether THROW is an emblem (defined, e.g., by Abner et al. 2015: 442 as “‘frozen’ gestural forms that have conventional meanings”). For the purposes of our paper, the question of whether THROW is an emblem or not is inconsequential in that we would, for instance, expect an analysis of pah in (2) to be very similar in its nature to the analysis that we propose for THROW, even though pah is clearly a conventionalized expression of the English language, with the first occurrence in the Oxford English Dictionary traced back to 1592. See https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/136033 (accessed 12 June 2022). [^]

- Gestures are in this respect parallel to language; see Sprouse and Almeida (2012; 2013), Sprouse et al. (2013), and Chen et al. (2020) for validation of introspective data in linguistics. [^]

- In this connection, it is worth pointing out that the anonymous reviewers also largely agreed with the central judgments in the manuscript, but reported divergent judgments in some individual cases. For an illustration of the type of divergent judgments that the reviewers reported, a reader may consider examples (11) and (12) in Section 2.3. While we report identical inferences from THROW in both (11) and (12), one reviewer notes that (11) expresses a more general dismissal for them, whereas (12) expresses a more specific dismissal. A different reviewer reports difficulties with the interpretation of examples (15)–(17), (26B2), and (40). For the sake of systematicity, we are only considering the judgments we elicited with the methodology that we established. [^]

- We do not aim to engage with the question of whether emotions are evaluative, but rather assume that the expression of an emotion or emotive attitude towards x entails some sort of evaluation of x. We refer a reader who is interested in this question to J. M. Müller (2017) and the literature cited therein. [^]

- We do not implement our analysis in terms of Questions Under Discussion (QUDs), but such an implementation would be compatible with our approach; see, e.g., Roberts (2012), Beaver et al. (2017). [^]

- Readers who are skeptical about the idea that an unimportant question implies that each answer is also unimportant may wish to consider examples such as the corpus example (i). As far as we can tell, either of the (constructed) continuations in (ii) would give rise to a contradiction, and hence infelicity, in line with our assumption.

- (i)

- The question of whether alien life exists is unimportant. (COCA, WEB 2012)

[^]- (ii)

- #… but if alien life {does/doesn’t} exist, then that is important!

- The use of THROW in (12B) can also communicate that A’s utterance is obviously false, in which case THROW roughly amounts to ‘No way!’ or ‘Sam wouldn’t do that!’ We return to such readings in Section 2.5. [^]

- Here, (21) is intended to be pronounced without narrow focus. It is worth pointing out that the addition of narrow focus, as in (i), gives rise to a similar effect to the one discussed in connection with (12). Here, narrow focus again makes salient a wh-question, which can be dismissed as shown in (ii).

- (i)

- Did [YOU]F murder Professor Plum?

[^]- (ii)

- YesTHROW but that is the wrong question. What you should be asking is: Why?

- (THROW ⤳ it is unimportant who murdered Professor Plum)

- An anonymous reviewer reports that THROW is acceptable for them in (22B) with an interpretation that amounts to “of course”. They suggest that such a reading would be similar to the insincere uses that we discuss in Section 3.3, which indeed seems highly plausible to us. [^]

- A reviewer notes that these examples also differ in that (30) is a dialogue while (31) is a monologue. A monologue version of (30) would also be acceptable, to the extent that performing extended monologues aloud is acceptable; the relevant example is given below as (i).

[^]

- (i)

- A:

- There’s a typo in my handout. (Thankfully,) no one will notice. (And) if

noticeTHROW, then I’ll just leave it as it is.

noticeTHROW, then I’ll just leave it as it is.

- There is an interesting, non-trivial question of when THROW has to target the immediately preceding utterance as its uk, which was the case in most of the examples that we have looked at so far, and when it can reach back further and target an earlier utterance. We suspect that it is specifically the nature of factual conditionals, namely that they echo a preceding statement, that allows THROW to reach back further when it accompanies such a conditional. Since A’s factual conditional in (30) echoes B’s statement, this seems to make B’s statement unavailable for being targeted by THROW, which in turn allows THROW to target A’s earlier statement instead. We leave a further exploration of these observations open for future research. [^]

- Finally, a reader may wonder if there are restrictions on whether THROW accompanies material that makes an at-issue contribution vs. a non-at-issue contribution. Although the material that THROW accompanies is arguably at-issue in each of (27)–(33), this is not entailed by our analysis. To see that THROW can accompany non-at-issue content, consider (i). Potts & Roeper (2006) argue that expressive small clauses such as You fool! (or, in (i), You loser!) are utterances that have a one-dimensional expressive meaning; by definition, such a meaning is non-at-issue. As shown, there are no restrictions against THROW co-occurring with such a non-at-issue utterance.

- (i)

- A:

- It’s getting late.

[^]- B:

-

loser!THROW (⤳ whether or not it’s getting late is unimportant)

loser!THROW (⤳ whether or not it’s getting late is unimportant)

- A reader may wonder if this is the best paraphrase for the contribution of THROW. However, the challenge to find a suitable paraphrase in itself is reminiscent of the ineffability of expressive content discussed by Potts (2005; 2007); see Blakemore (2011) for more detailed discussion. [^]

- There is an abundance of naturally occurring examples for this use of THROW, including the GIF at the following URL (last accessed on 27 December 2021): https://giphy.com/gifs/burn-cameo-oFeUVZfiuim9G/. [^]

- One question is whether the Maxim of Quality can be straightforwardly applied to the type of non-at-issue content that THROW deploys; we leave this issue open for future research. [^]

- We direct readers who may not have pah in their active vocabulary to the relevant entry on Wiktionary: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pah#Etymology_1 (last accessed on 17th December 2021). The Oxford English Dictionary traces pah back to 1592 and defines it as an interjection “expressing disgust or disdain”. Source: “pah, int. and adj.”. OED Online. December 2021. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/136033?rskey=hbGfZa&result=2&isAdvanced=false (accessed 17 Dec. 2021) [^]

- Observe that native speakers of English generally do not accept co-speech THROW in this context, as indicated by ‘#’ in (i-B), only pro-speech THROW, as in (55B1); this observation highlights a cross-linguistic difference between English and German, worth exploring in future research, as German speakers accept the German counterpart of (i-B).

- (i)

- A:

- Sam is building a table.

[^]- B:

- #TableTHROW! Call me when Sam has built something worthwhile.

- For example, insincere uses of the type discussed in Section 3.3 are often accompanied by a smile: https://giphy.com/gifs/CoachJoshWood-Ft7adwBzipO9AKwcnb (last accessed 28 Dec 2021) [^]

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Jana Bressem and Philippe Schlenker for valuable written comments. For helpful discussion, we thank the audiences at Semantics and Linguistic Theory 32, the DGfS 44 workshop Visual Communication: New Theoretical and Empirical Developments (ViCom), and Cecilia Poletto’s research seminar at the University of Frankfurt. Finally, we thank the Glossa reviewers and the handling editor Ana Aguilar-Guevara for the time they dedicated to reviewing and editing this article. We are particularly grateful to Ana for exceptionally helpful constructive feedback and exchanges which significantly improved the paper. This research was supported by funding from the Faculty of Humanities career development grant at the University of Oslo [PI: Patel-Grosz] and the Horizon 2020 ERC Advanced Grant 787929 SPAGAD: Speech Acts in Grammar and Discourse.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Abner, Natasha & Cooperrider, Kensy & Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2015. Gesture for linguists: A handy primer. Language and Linguistics Compass 9. 437–449. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12168

Ameka, Felix. 1992. Interjections: The universal yet neglected part of speech. Journal of Pragmatics 18. 101–118. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(92)90048-G

Asher, Nicholas. 1993. Reference to abstract objects in English: A philosophical semantics for natural language metaphysics. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Asher, Nicholas & Lascarides, Alex. 2003. Logics of conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bavelas, Janet B. & Chovil, Nicole & Lawrie, Douglas A. & Wade, Allan. 1992. Interactive gestures. Discourse Processes 15. 469–489. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01638539209544823

Beaver, David & Clark, Brady. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning. Malden, MA and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9781444304176

Beaver, David & Roberts, Craige & Simons, Mandy & Tonhauser, Judith. 2017. Questions Under Discussion: Where information structure meets projective content. Annual Review of Linguistics 3. 265–284. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011516-033952

Benus, Stefan & Gravano, Augustin & Hirschberg, Julia Bell. 2007. Prosody, emotions, and… ‘whatever’. Interspeech 2007. 2629–2632. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2007-691

Bergen, Leon & Levy, Roger & Goodman, Noah. 2016. Pragmatic reasoning through semantic inference. Semantics and Pragmatics 9(20). DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/sp.9.20

Blakemore, Diane. 2011. On the descriptive ineffability of expressive meaning. Journal of Pragmatics 43. 3537–3550. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.08.003

Brauße, Ursula. 1994. Lexikalische Funktion der Synsemantika. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

Bressem, Jana & Müller, Cornelia. 2014. The family of Away gestures: Negation, refusal, and negative assessment. In Müller, Cornelia & Cienki, Alan & Fricke, Ellen & Ladewig, Silva H. & McNeill, David & Bressem, Jana (eds.), Body – language – communication. An international handbook on multimodality in human interaction (HSK 38.2), 1592-1604. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110302028.1592

Bressem, Jana & Müller, Cornelia. 2017. The “Negative-Assessment-Construction” – A multimodal pattern based on a recurrent gesture? Linguistic Vanguard 3. 20160053. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2016-0053

Büring, Daniel. 2003. On D-trees, beans and B-accents. Linguistics and Philosophy 26. 511–545. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025887707652

Büring, Daniel & Gunlogson, Christine. 2000. Aren’t positive and negative polar questions the same? Ms. UCSC/UCLA.

Calbris, Geneviève. 2011. Elements of meaning in gesture (Gesture Studies 5). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/gs.5

Chen, Zhong & Xu, Yuhang & Xie, Zhiguo. 2020. Assessing introspective linguistic judgments quantitatively: the case of The syntax of Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 29. 311–336. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-020-09210-y

Cohen, Ariel & Krifka, Manfred. 2014. Superlative quantifiers and meta-speech acts. Linguistics and Philosophy 37. 41–90. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-014-9144-x

Cooperrider, Kensy & Abner, Natasha & Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2018. The Palm-Up puzzle: Meanings and origins of a widespread form in gesture and sign. Frontiers in Communication 3. 23. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00023

Daniels, Micky. 2019. Focus over a speech act operator: A revised semantics for ‘our even’. North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 49. 187–198.

Declerck, Renaat & Reed, Susan. 2001: Conditionals: A comprehensive empirical analysis. Amsterdam: Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110851748

Degaetano-Ortlieb, Stefania. 2015. Evaluative meaning and cohesion: The structuring function of evaluative meaning in scientific writing. Discours 16. 3–29. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/discours.9053

Ebert, Cornelia & Evert, Stefan & Wilmes, Katharina. 2011. Focus marking via gestures. Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 15. 193–208. https://ojs.ub.uni-konstanz.de/sub/index.php/sub/article/view/372.

Ebert, Cornelia & Ebert, Christian. 2014. Gestures, demonstratives, and the attributive/referential distinction. Talk given at Semantics and Philosophy in Europe (SPE 7), 28 June. https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/GJjYzkwN/EbertEbert-SPE-2014-slides.pdf.

Eckardt, Regine & Disselkamp, Gisela. 2019. Self-addressed questions and indexicality: The case of Korean. Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 23. 383–398. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2019.v23i1.539

Ernst, Thomas. 2007. On the role of semantics in a theory of adverb syntax. Lingua 117. 1008–1033. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2005.03.015

Ernst, Thomas. 2009. Speaker-oriented adverbs. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 27. 497–544. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-009-9069-1

Esipova, Masha. 2019. Composition and projection in speech and gesture. New York, NY: New York University dissertation. https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/004676

Farkas, Donka & Bruce, Kim. 2010. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics 27. 81–118. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffp010

Frana, Ilaria & Rawlins, Kyle. 2019. Attitudes in discourse: Italian polar questions and the particle mica. Semantics and Pragmatics 12(16). 1-48. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/sp.12.16

Francis, Naomi. 2021. Objecting to discourse moves with gestures. Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 25. 267–275. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2021.v25i0.936

Giustolisi, Beatrice & Panzeri, Francesca. 2021. The role of visual cues in detecting irony. Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 25. 292–306. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2021.v25i0.938

Goddard, Cliff. 2014. Interjections and emotion (with special reference to “surprise” and “disgust”). Emotion Review 6. 53–63. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1754073913491843

Green, Georgia M. 1976. Main clause phenomena in subordinate clauses. Language 52. 382–397. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/412566

Grice, Paul. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Cole, Peter & Morgan, Jerry (eds.), Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3: Speech Acts, 41–58. New York, NY: Academic Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1163/9789004368811_003

Grohmann, Kleanthes K. & Nevins, Andrew I. 2004. On the syntactic expression of pejorative mood. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 4. 143–179. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/livy.4.05gro

Grosz, Patrick Georg. 2020. Discourse particles. In Gutzmann, Daniel & Matthewson, Lisa & Meier, Cécile & Rullmann, Hotze & Zimmermann, Thomas (eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to semantics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9781118788516.sem047

Gunlogson, Christine. 2003. True to form: Rising and falling declaratives as questions in English. London and New York: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203502013