1 Introduction

For German, it has been argued that adverbial adjuncts – just as complements – have syntactic base positions in the so-called middlefield, the area between the complementizer and the verbal head in embedded clauses, and are ordered with respect to each other, the verbal arguments, and the base position of the finite verb (Frey & Pittner 1998; Frey 2003). These preferences are reflected in acceptability judgments and online sentence processing for different adverbial types (for an overview, see Stolterfoht & Gauza & Störzer 2019). In the present study, we will focus on propositional adverbials, syntactically high adverbials that take scope over the entire proposition (Steube 2014). (1) provides an example item tested in Störzer & Stolterfoht (2013) with frame and sentence adverbials in their assumed base order. The authors measured reading times on the two adverbials in the base order and a derived order in which the frame adverbial moved across the sentence adverbial (1b).

- a.

- Eva

- Eva

- meint,

- means

- dass

- that

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- [auf

- on

- Mallorca]frame

- Majorca

- alle

- all

- Urlauber

- tourists

- betrunken

- drunk

- sind.

- are

- b.

- Eva

- Eva

- meint,

- means

- dass

- that

- [auf

- on

- Mallorca]frame

- Majorca

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- alle

- all

- Urlauber

- tourists

- betrunken

- drunk

- sind.

- are

- ‘Eva thinks that probably in Majorca all tourists are drunk.’

For frame and sentence adverbials, Störzer & Stolterfoht (2013) attested an immediate increase in reading times and lower ratings in acceptability judgments for the derived order. However, their results reveal an interaction with the referentiality of the DPs within frame adverbials. The base position preference was observed for frame adverbials with non-referential DPs like auf jeder lnsel (‘on every island’), but not for referential ones like auf Mallorca (‘in Majorca’), see example (1). The authors give an explanation in information-structural terms, namely the topicality of frame adverbials. Following Frey (2004), who argues that German is discourse configurational with respect to topics and has a designated topic position within the middlefield above sentence adverbials, frame adverbials with referential DPs seem to preferentially move out of their base position below sentence adverbials to this topic position. According to Frey, sentence adverbials thus serve as a boundary between topic and comment, and only topics can fill the position above sentence adverbials (for a similar view, see Haftka 2003). Consequently, any phrase positioned higher than the sentence adverbial has to express topicality. Frey (2004) argues that frame adverbials are required to be referential in order to occupy the topic position above the base position of sentence adverbials. Whether frame adverbials are referential and are able to be sentence topics will be discussed in the next section.

Additional experimental evidence for a topic position above sentence adverbials and the processing of topic movement for verbal arguments is reported in Stolterfoht & Frazier & Clifton (2007) for English, and in Störzer & Stolterfoht (2013), and Störzer & Stolterfoht (2018) for German (for further evidence, see Repp 2017). These experiments showed that online processing seems to be sensitive to syntactic information only, indicating that processing is facilitated when the adverbial and the subject appear in their base order in an early processing stage. However, relevant information-structural information like the referentiality of the subject DP or of the frame adverbial’s internal argument are evaluated in a later processing step since the effect of referentiality is only visible in the offline rating data. The authors conclude that, at least on sentence level without a preceding context, the processing of information structure takes place in a later processing stage and is hence only visible in the offline data but not in the online self-paced reading data.

Specht & Stolterfoht (2022) report a similar experiment, but used another type of frame adjunct, namely domain adverbials like ‘gesundheitlich’ (healthwise).

- (2)

- a.

- Hanna

- Hanna

- sagt,

- says

- dass

- that

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- [gesundheitlich]domain

- healthwise

- Tim

- Tim

- etwas

- something

- vorgetäuscht

- pretended

- hat.

- has

- b.

- Hanna

- Hanna

- sagt,

- says

- dass

- that

- [gesundheitlich]domain

- healthwise

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- Tim

- Tim

- etwas

- something

- vorgetäuscht

- pretended

- hat.

- has

- ‘Hanna says that healthwise Tim probably faked something.’

To control for ordering effects that might be caused by differences in phrase length between frame and sentence adverbials in the earlier studies, domain adverbials were realized as adjectives and were matched in length with the adjacent sentence adverbials. The results of this self-paced reading experiment provided further evidence that deviations from the base order of propositional adverbials lead to an immediate increase in reading times. This pattern of results shows that propositional adverbials are processed highly incrementally word-by-word and that initial processing is influenced by the semantic adverbial category and syntactic position. What remains to be seen is whether information structure plays a role for domain adverbials as well. Domain adverbials realized as adjectives do not vary with regard to the referentiality of their parts, in contrast to the frame adverbials used in earlier studies.

We will present two acceptability rating studies investigating position preferences for domain adverbials. These data are crucial in shedding further light on the temporal dynamics of adverbial order processing, given the discrepancies between online and offline data in the earlier studies introduced above.

In our first experiment, we will address the following questions:

(I) Are domain adverbials, despite the fact that they do not embed referential DPs, suitable candidates for the topic position above the base position of sentence adverbials?

In our second experiment, we will additionally compare position variations regarding domain adverbials and the sentence’s subject to answer the following second question:

(II) What is the best candidate for the assumed topic position?

Before we present our experiments, we will first outline the syntactic and semantic properties of the propositional adverbials in question. Furthermore, we will address information-structural characteristics of domain adverbials in comparison to frame adverbials and argue that domain adverbials can be analyzed as non-referential topical elements in the sense of delimitation, a function of information packaging.

2 Theoretical background

We derived our predictions with regard to adverbial order preferences from base position accounts for adverbials, such as Frey and Pittner (1998) and Frey (2003). These accounts postulate that adverbials, like complements, are base-generated in the German middlefield (the area between complementizer and the verbal head in embedded clauses) and can undergo scrambling, a movement operation bound to the middlefield in German.

The authors argue that adverbials in German and English fall into five categories according to their lexico-semantic properties. We use these authors’ terminology by referring to the classes as adjuncts and the respective members of the class as adverbials, which reflects the mixed character of the account: the adverbials within one class are classified according to semantic properties, and these properties hence enter the syntactic derivation in terms of syntactic base positions. The classes are ordered with respect to each other and the arguments of the sentence, as well as the finite verb. The predicted relative order is given here:

sentence adjuncts (e.g., sentence adverbials)

frame adjuncts (e.g., frame, and domain adverbials)

event-external adjuncts (e.g., temporal adverbials, causals)

event-internal adjuncts (e.g., locative, instrumental)

process-related adjuncts (e.g., manner adverbials)

In the assumed base position, adverbials c-command the domain they modify. Sentence and frame adjuncts have their base position above the Tense Phrase (TP), and therefore also above the highest-ranked verbal argument. With regard to the relative order, sentence adjuncts are base-generated above frame adjuncts. Event-external adjuncts have their base position above VP, whereas event-internal and process-related adjuncts are inside the VP (adjoined to V’ or V0). Other accounts suggest that adverbials project a functional spine, follow a rigid syntactic order and are not able to move (e.g., Cinque 1999), or that adverbial position is mainly determined semantically (e.g., Haider 2000; Ernst 2001). An extensive discussion about the driving forces, i.e., semantics or syntax, is beyond the scope of this paper, and the interested reader is referred to the cited work. We remain agnostic about the underlying forces of adverbial ordering, i.e., whether they are semantic and/or syntactic in nature, since the empirical predictions with regard to order preferences do not differ across the different accounts. The very detailed base position account for German adverbial ordering, however, allows us (i) to derive precise predictions about order preferences and (ii) to assume that adverbials can scramble and henceforth are able to move out of their base positions. Several psycholinguistic studies on word order variations, mainly focusing on complements, have shown that movement comes with a processing cost (e.g., Rösler et al. 1998; Bader & Meng 1999). The assumption that adverbials occupy base positions and therefore scramble entails that moved adverbials should also lead to higher processing costs and lower ratings.

2.1 Propositional adverbials

For the present study, we will focus on order preferences of propositional adverbials, more precisely on speaker-oriented sentence adverbials and domain adverbials. Sentence and frame adjuncts are assumed to be located high in the sentence structure, namely above the subject (e.g., Cinque 1999; Frey & Pittner 1999; Maienborn 2001). We assume that they are located below the C-head and above TP, and that TP is mapped onto the proposition.

Domain and frame adverbials are both classified as frame adjuncts. Semantically, domain and frame adverbials share the property of restricting the proposition to a certain locative or temporal frame (Maienborn 2001) or to a specific dimension or domain.

- (3)

- a.

- [In

- in

- Australien]frame

- Australia

- sind

- are

- alle

- all

- Schwäne

- swans

- schwarz.

- black

- ‘In Australia, all swans are black.’

- b.

- [Gesundheitlich]domain

- healthwise

- geht

- goes

- es

- it

- Peter

- Peter

- gut.

- good

- ‘Healthwise, Peter is doing fine.’

In example (3a), the truth of the proposition alle Schwäne sind schwarz (‘all swans are black’) is restricted to the local frame in Australien (‘in Australia’). In (3b), Peter geht es gut (‘Peter is doing fine’) holds true only for the health dimension or domain.

Ernst (2004) characterizes domain adverbials as event-modifying. Bellert (1977) and Schäfer (2013) subsume domain adverbials as an instance of sentence adjuncts. We distinguish frame adjuncts from sentence adjuncts because they share some but not all properties with sentence adverbials. Sentence adverbials do not form a homogeneous group, consisting of evidential, epistemic, and evaluative adverbials. We focus on epistemic and evidential speaker-oriented sentence adverbials.1 Semantically, the former expresses the speaker’s expectation regarding the truth of the expressed proposition. The latter relativizes the speaker’s commitment to the truth of the proposition by referring to a certain source. An example for epistemic and evidential sentence adverbials is given in (4). For an overview of the different types of sentence adverbials also see Schäfer (2013).

- (4)

- Präsident

- President

- Franklin

- Franklin

- war

- was

- wahrscheinlichepi /

- probably

- angeblichevi

- allegedly

- Veganer.

- vegan

- ‘President Franklin was probably/allegedly a vegan.’

Like sentence adverbials, but unlike lower event-modifying adverbials, frame adjuncts cannot be in the scope of sentence negation (see (5)).2 However, frame adjuncts do not provide a comment on the proposition as speaker-oriented sentence adverbials do. Finally, they can appear in imperatives in (6a), and are not sensitive to modal operators such as questions in (6b) in contrast to the sentence adverbials in (6c) and (6d) (Pittner 1999).

- (5)

- a.

- Dieses

- this

- Beispiel

- example

- ist

- is

- syntaktisch

- syntactically

- nicht

- not

- (*syntaktisch)

- syntactically

- interessant.

- interesting

- ‘Syntactically, this sentence is not interesting.’

- b.

- Peter

- Peter

- sagt,

- says

- dass

- that

- Björn

- Björn

- (*laut)

- loudly

- nicht

- not

- laut

- loudly

- singt.

- sings.

- ‘Peter says that Björn does not sing loudly.’

- (6)

- a.

- Überarbeite

- Revise

- den

- the

- Artikel

- article

- inhaltlich!

- contentwise

- ‘Revise the article with regard to content.’

- b.

- Hast

- Have

- du

- you

- den

- the

- Artikel

- article

- orthografisch

- orthographically

- verbessert?

- improved

- ‘Did you improve the article regarding orthography?’

- c.

- *Überarbeite

- Revise

- den

- the

- Artikel

- article

- wahrscheinlich!

- probably

- d.

- *Hast

- Have

- du

- you

- den

- the

- Artikel

- article

- wahrscheinlich

- probably

- überarbeitet?

- revised

We therefore assume that frame adjuncts and sentence adjuncts are separate classes. Example (7) reflects the assumed base order of sentence adverbials relative to domain and frame adverbials, according to Frey (2004).

- (7)

- a.

- Eva

- Eva

- meint,

- means

- dass

- that

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- [auf

- in

- Mallorca]frame

- Majorca

- alle

- all

- Urlauber

- tourists

- betrunken

- drunk

- sind.

- are

- ‘Eva thinks that probably in Majorca all tourists are drunk.’

- b.

- Eva

- Eva

- meint,

- means

- dass

- that

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- [finanziell]domain

- financially

- alle

- all

- Studierenden

- students

- Probleme

- problems

- haben.

- have

- ‘Eva thinks that probably financially all students are in difficult situations.’

Before we present our experiments investigating order preferences of sentence and frame adjuncts, we will have a closer look at the information-structural characteristics of both adjunct types.

2.2 Information structural characteristics of frame and sentence adjuncts

As already mentioned in the introduction, Störzer & Stolterfoht (2013) showed that online reading time data exhibit a preference for the assumed base order with the sentence adverbial preceding the frame adverbial, but offline data showed an interaction with the referentiality of the DPs embedded within the frame adverbial. A frame adverbial with a non-referential quantifier DP as its internal argument like auf jeder Insel (‘on every island’) is preferred in its assumed base position below the sentence adverbial, reflected in higher acceptability ratings, whereas a frame adverbial with a referential DP like auf Mallorca (‘in Majorca’) exhibits a preference for the position above the sentence adverbial. Frey (2004) assumes that the position above the sentence adverbial is a position that can only be filled by the sentence topic, which is construed as an aboutness topic. Following Reinhart (1981), aboutness topics are understood as entries in a library catalog. The proposition expressed by a sentence is stored with that entry as it provides information about the respective topic.

- (8)

- (Frey 2004: 5)

- Tell me something about Peter

- a.

- Maria

- Maria

- sagt,

- says

- dass

- that

- Peter

- Peter

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- seine

- his

- Kollegin

- colleague

- heiraten

- marry

- wird.

- will

- b.

- ??Maria

- Maria

- sagt,

- says

- dass

- that

- [wahrscheinlich]sadv

- probably

- Peter

- Peter

- seine

- his

- Kollegin

- colleague

- heiraten

- marry

- wird.

- will

- ‘Maria said that Peter probably will marry his colleague.’

Based on examples like (8), together with several other linguistic tests, Frey concludes that “(I)n the middle field of the German clause, directly above the base position of sentential adverbials (sadvs), there is a designated position for topics: all topical phrases occurring in the middle field, and only these, occur in this position.” (Frey 2004: 5).

Since frame adjuncts do appear in the position above sentence adverbials, Frey concludes that they are able to be aboutness topics, but only if they are, what he calls “referential”, i.e., hosting a referential DP (see also Pittner 2004; Steube 2006).

Nevertheless, frame adjuncts like frame and domain adverbials are non-referential, whether or not they are hosting a referential DP. They are operators that restrict the domain of reality with regard to which the truth of the proposition is evaluated (see e.g., Bellert 1977; Schäfer 2013). One difference between the frame and domain adverbials under consideration (see examples in (1) and (2)) concerns the possibility of a referential internal argument. The open question is whether an adjectival domain adverbial without a referential internal argument is a suitable candidate for the topic position above the sentence adverbial.

With regard to the discourse-structuring function of frame and domain adverbials, they exhibit a quite similar behavior. As already said, both restrict the truth of the proposition to a specific domain. That means that the utterance might only be a partial answer to the current Question-Under-Discussion (QUD) (see e.g., Roberts 1996). The information-structural properties of frame adjuncts have been furthermore described by Jacobs (2001). He assumes four dimensions of topicality. Relevant for the discussion of our findings are the following two given in (9) and (10):

- (9)

- Addressation: In (X Y), X is the address for Y iff X marks the point in the speaker-hearer knowledge where the information carried by Y has to be stored at the moment of the utterance of (X Y)

- (10)

- Frame Setting: In (X Y), X is the frame for Y iff X specifies a domain of (possible) reality to which the proposition expressed by Y is restricted

The characterization of Addressation is compatible with Reinhart’s aboutness topic definition. Frame Setting goes back to Chafe’s (1976) conception of Chinese style topics, which are not understood in terms of aboutness but as restricting the assertion to a spatial, temporal, or locative frame. Krifka (2008a) introduces the term delimitation, under which he subsumed Jacob’s frame setters as well as contrastive topics (e.g., Roberts 1996). He describes the information structural function of delimitation as follows: “If the informational need cannot be satisfied by a simple statement, break up the issue into sub-issues, and indicate how they answer the big issue” (Krifka 2008b: 3). Addressation and delimitation are both selectional functions with regard to information packaging, and delimitators are not required to be referential (for discourse structuring functions of domain adverbials, see also Salfner 2018).

We conclude that Frame Setting, besides Addressation, is a dimension of topicality, and that frame adjuncts are therefore suitable candidates for the topic position above sentence adverbials. We already saw support for this claim with frame adverbials hosting a referential DP (Störzer & Stolterfoht 2013). Higher acceptability ratings for sentences with this type of frame adverbial in the assumed topic position also support the conclusion that constituents fulfill their discourse-structuring function if possible. The question of whether referentiality of the internal argument is a prerequisite of movement to the topic position to fulfill discourse-structuring functions will be addressed in our first experiment.

3 Experiment 1: Acceptability Judgment: Adverbial order

With an acceptability judgment experiment, we are addressing the question of whether a non-referential adjectival domain adverbial is able to move to the topic position above sentence adverbials. The online reading time results in Specht & Stolterfoht (2022) yield evidence for the base order account of propositional adverbials. Movement of a domain adverbial across a sentence adverbial caused processing costs immediately. We saw this pattern of results for frame adverbials also in Störzer & Stolterfoht (2013). But additionally, the authors report a discrepancy of online and offline data, with a preference for a frame adverbial with a referential internal argument preceding the sentence adverbial. Besides order variations of sentence and domain adverbials, Specht & Stolterfoht (2022) also look at order variations of temporal and sentence adverbials in their study, with a different research question not relevant for the current study. We will nevertheless include these materials as control conditions in the present study as well, to keep the materials maximally parallel, but more importantly, to test whether the discourse-structuring function of a domain adverbial is tied exclusively to the position above the sentence adverbial, as suggested by Frey (2004), and cannot be realized above another type of adverbial.

We conducted an acceptability judgment experiment using the same materials as the above-mentioned study. The materials manipulated two independent variables adv_type, sentence adverbial (sadv) vs. temporal adverbial (tadv), and ORDER, base vs. derived, see the examples in (11). The sentence’s subject is in its assumed base position below the two adverbials in all conditions.3

- (11)

- Hanna

- Hanna

- sagt,|

- says

- dass|

- that

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- wahrscheinlichSADV

- gesundheitlichdomain

- healthwisedomain

- gesundheitlichdomain

- gesternTADV

- yesterdayTADV

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- gesundheitlichdomain

- wahrscheinlichSADV

- probablySADV

- gesternTADV

- gesundheitlichdomain

- healthwisedomain

- [sadv-base]

- [sadv-derived]

- [tadv-base]

- [tadv-derived]

- Tim

- Tim

- etwasspill-over

- something

- |

- vorgetäuscht

- pretended

- hat

- has

- |

- und

- sich

- refl

- deshalb

- therefore

- entschuldigt

- excuses

- ‘Hanna says that [adv] Tim [adv] faked something and thus apologizes.’

We derived two possible hypotheses, one referring to the syntactic base position account, assuming that acceptability judgments only reflect syntactic preferences, and an alternative information-structural hypothesis with the assumption that information-structural preferences influence adverbial order:

Syntactic hypothesis 1.a

If the assumed base order of adverbials is reflected in acceptability ratings as well, a main effect Order with overall higher ratings for the syntactic base order (sentence adverbial > domain adverbial and domain adverbial > temporal adverbial) is predicted.

The alternative information-structural hypothesis 1.b

If sentence adverbials – but not temporal adverbials – mark the topic position in German, and domain adverbials move to this position for reasons of discourse structuring, an interaction of ORDER and adv_type with overall higher ratings for the derived order of domain adverbial and sentence adverbial is predicted. For the order variation of domain adverbials and temporal adverbials, we expect no difference for the two orderings, since no discourse structuring function is explicitly marked by temporal adverbials.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

36 students (mean age = 23.03, SD = 8.62) of the University of Tübingen participated in the experiment for either course credit or a financial reimbursement of 5€/30 minutes. All participants were adult native speakers of German, according to their self-reports, and naive with respect to the purpose of the experiment.

3.1.2 Materials

We used the same 24 experimental items as in the self-paced reading study reported in Specht & Stolterfoht (2022). An example item is presented in example (11). The materials manipulated two factors Order (‘base’ vs. ‘derived’) and adv_Type (sadv vs. tadv) within-items and within-subjects. The items consisted of embedded sentences to maintain the verb-final base order of German. The factor adv_type manipulated the types of adverbials paired with the domain adverbial, namely sentence adverbial (sadv) and temporal adverbial (tadv). The experimental items were presented with 48 filler sentences, which contained other types of adverbials.

3.1.3 Procedure

Participants were invited to the lab to fill in a computer-based questionnaire. The experiment was programmed with the software E-Prime 2. Sentences had to be rated on a 5-point Likert scale, 5 = perfectly acceptable and 1 = completely unacceptable. The endpoints of the scales were labeled. Participants were given five practice items. The entire procedure lasted about 15 minutes.

3.2 Results and analysis

For the analysis, we ran a cumulative link mixed model (clmm). As fixed effects, we entered the experimental factors, as well as their interaction. Both factors were analyzed as within-item and -subject manipulations. The model included random intercepts for items and participants with the maximal random effect structure supported by the data. We obtained p-values by Laplace approximation. The descriptive data are presented in Figure 1. The output of the model is shown in Table 1. The data showed low overall ratings for all conditions (‘base’: mean = 2.37, SD = 1.07; ‘derived’: 2.63, SD = 1.13; tadv: mean= 2.47, SD = 1.11; sadv mean= 2.52, SD = 1.11). The model revealed a main effect of Order with higher ratings for the derived order. adv_type did not reach the level of significance. As the interaction of the factors was significant, we conducted a post-hoc Tukey test, which revealed that the difference for the factor ORDER is mainly carried by the sadv conditions (z = –4.812; p <.0001) while the difference between the ‘base’ and ‘derived’ order within the tadv condition is not significant (z= –1.179; p = .64).

Statistical analysis clmm of acceptability ratings.

| Formula: rating ~ order*adv_type + (1 | subject) + (1 | item) | ||||

| Coefficient | SE | z-value | p | |

| order | –0.53 | 0.13 | –4.12 | <.0001*** |

| adv_type | –0.09 | 0.13 | –0.71 | .47 |

| adv_type: order | 0.71 | 0.26 | 2.77 | .005** |

3.3 Discussion

The experiment provided evidence for the information-structural hypothesis 1.b. The model revealed a significant preference for the derived order over the postulated base order. This preference was driven by the sadv conditions, with significantly higher ratings for the derived order (domain adverbial > sentence adverbial), hence the propositional adverbials. We interpret this as evidence for Frey’s assumption that the medial topic position is tied to the position above the sentence adverbials, but cannot be marked by temporal adverbials. As predicted no significant effect of ORDER was observed for temporal adverbials, since temporal adverbials do not mark position relevant for information structure. But there might be a plausible alternative explanation of this result in information-structural terms. Temporal adverbials like ‘yesterday’ can also be interpreted as frame adjuncts, and might be interpreted as such if they appear above the domain adverbial. With this in mind, the missing rating difference for the two orderings is due to the fact that temporal adverbials as well as domain adverbials are able to fulfill a discourse-structuring function if they appear at the highest position in the middlefield, and therefore, no difference is observed for the two orderings. The question of whether this is a reliable explanation remains a topic for further research.

With regard to our research questions, we could show that (i) the medial topic position is open to delimitators, (ii) domain adverbials are preferred in this position, as has been already shown for frame adverbials, and (iii) referentiality of the internal argument within the frame adjunct is not a prerequisite for movement to the medial topic position. Based on the results by Specht and Stolterfoht (2022), we assume that the base position of domain adverbials is nevertheless below the sentence adverbial, which was shown in the online data, but they preferably move to meet information-structural constraints, which is evaluated in a later processing step, revealed by the offline acceptability ratings.

One characteristic of our results needs further explanation. The data showed, independent of the experimental factors, low overall ratings for both order variations (‘base’: mean = 2.37, SD 1.07; ‘derived’: 2.63, SD = 1.13), and both adverbial types (tadv: mean = 2.47, SD = 1.11; sadv: mean = 2.52, SD = 1.11). A possible reason for the generally low ratings might be that the subject of our sentences stays in its base position below the adverbials (see also footnote 3). All the subject DPs in our experimental items were proper names hence definite referential DPs. A definite DP is a prototypical candidate for an aboutness topic, and therefore might move preferentially to the designated topic position higher up in the structure. As already mentioned above, we used this word order to preserve the base order of the adverbials and the subject. The low ratings we attested for this order are thus not caused by a derived syntactic structure but might be due to a violation of an information-structural preference.

In section 2.2 we introduced two dimensions of topicality, Frame Setting and Addressation. Delimitators fulfill the dimension of Frame Setting, whereas aboutness topics realize Addressation. Referential subject DPs are the most prototypical instances of aboutness topics. Krifka (2008b) assumes that Addressation applies to a basic principle of how humans store information. He understands addresses as pointers from which information can be accessed and where it will be attached. He further assumes that address-centered storage coincides with linguistic strategies. One such strategy is Address first!, which states that identifying the pointer first facilitates information management. The materials in Experiment 1 violated this strategy since in all four conditions, the address, the topical referential subject DP, follows the frame setting domain adverbial (see examples in (11)).

Consequently, the subject DP should be preferred in the medial topic position and thus precede the delimitators. Sentences obeying the Address first! principle should receive higher ratings. We will test this explanation for the overall low ratings with a second acceptability judgment experiment.

4 Experiment 2: Adverbial order and information structure

We argue that the low ratings in Experiment 1 were subject to a violation of more general discourse-structuring preferences that enable efficient information management, namely Addressation over Frame Setting. To test this hypothesis, we created a new set of materials. We assume that domain adverbials should be preferred in their base position below sentence adverbials when a prototypical aboutness topic like a definite DP fills the medial topic position and, therefore, blocks the domain adverbial’s movement into the medial topic position.4

Example (12) illustrates the experimental conditions we tested in Experiment 2. We manipulated Position (adverbials first ‘adv_first’ vs. subject first ‘subj_first’) and Order (‘base’ vs. ‘derived’) of the adverbials.

- (12)

- Lukas

- Lukas

- berichtet,|

- reports

- dass|

- that

- a.

- b.

- c.

- d.

- vermutlichsadv

- wirtschaftlichdomain

- Clarasubject

- Clarasubject

- Clara

- -

- -

- wirtschaftlichdomain

- vermutlichsadv

- vermutlichsadv

- wirtschaftlichdomain

- economically

- -

- -

- Clarasubject

- Clarasubject

- wirtschaftlichdomain

- vermutlichsadv

- presumably

- [adv_first-base]

- [adv_first-derived]

- [subj_first-base]

- [subj_first-derived]

- informiert

- informed

- ist.

- is

- ‘Lukas reports that Clara is presumably economically informed.’

Based on the discussion in the previous section, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2

According to Address first! and on the basis of the results of Experiment 1, Addressation by a referential subject DP in the assumed topic position above the sentence adverbial is preferred over a domain adverbial in this position. We therefore predict a main effect of Position with higher ratings for the adverbials following the subject.

Hypothesis 3

According to Adress first!, and the assumption that the subject in topic position blocks the movement of a domain adverbial to this position, the preferred order of adverbials following the subject is the base order whereas preceding the subject, the derived order is preferred.

We therefore predict an interaction of Order and Position with overall higher ratings for the derived order (domain adverbial > sentence adverbial) if the subject stays in its base position, but a preference for the base order (sentence adverbial > domain adverbial) if the adverbials precede the subject.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

32 participants (mean age = 31.9; SD = 11.2) were recruited in Prolific.co. All participants were adult native speakers of German, according to their self-reports, and were paid 2,20 € for 15 minutes.

4.1.2 Materials

We constructed 24 sentence quadruplets and manipulated the two factors Position (subject first ‘subj_first’ vs. adverbials first ‘adv_first’) and Order (‘base’ vs. ‘derived’) within-items and within-subjects (see examples in (12)). As in the previous experimental materials, the items consisted of embedded sentences to maintain the verb-final base order of German. In contrast to the previous experiment, we used stative copula constructions instead of eventive verbs. The eventive verbs in the earlier experiments were required to allow for event modification with temporal adverbials, but since we were only interested in propositional adverbials in the current study, we used only copula-adjective constructions, which make the potential reading of domain adverbials as event-modifying (method-oriented or manner adverbials) highly unlikely. The experimental items were presented with 48 filler sentences, which contained other types of adverbials.

4.1.3 Procedure

The experiment was programmed as an online questionnaire with the help of the open-source experimental software PsychoPy3 (Peirce et al. 2019) and the hosting platform Pavlovia.org. In the experiment, sentences had to be rated on a 5-point Likert scale, 5 = perfectly acceptable and 1 = completely unacceptable. The endpoints of the scale were labeled. Participants were given five practice items. The entire procedure lasted about 15 minutes.

4.2 Results and analysis

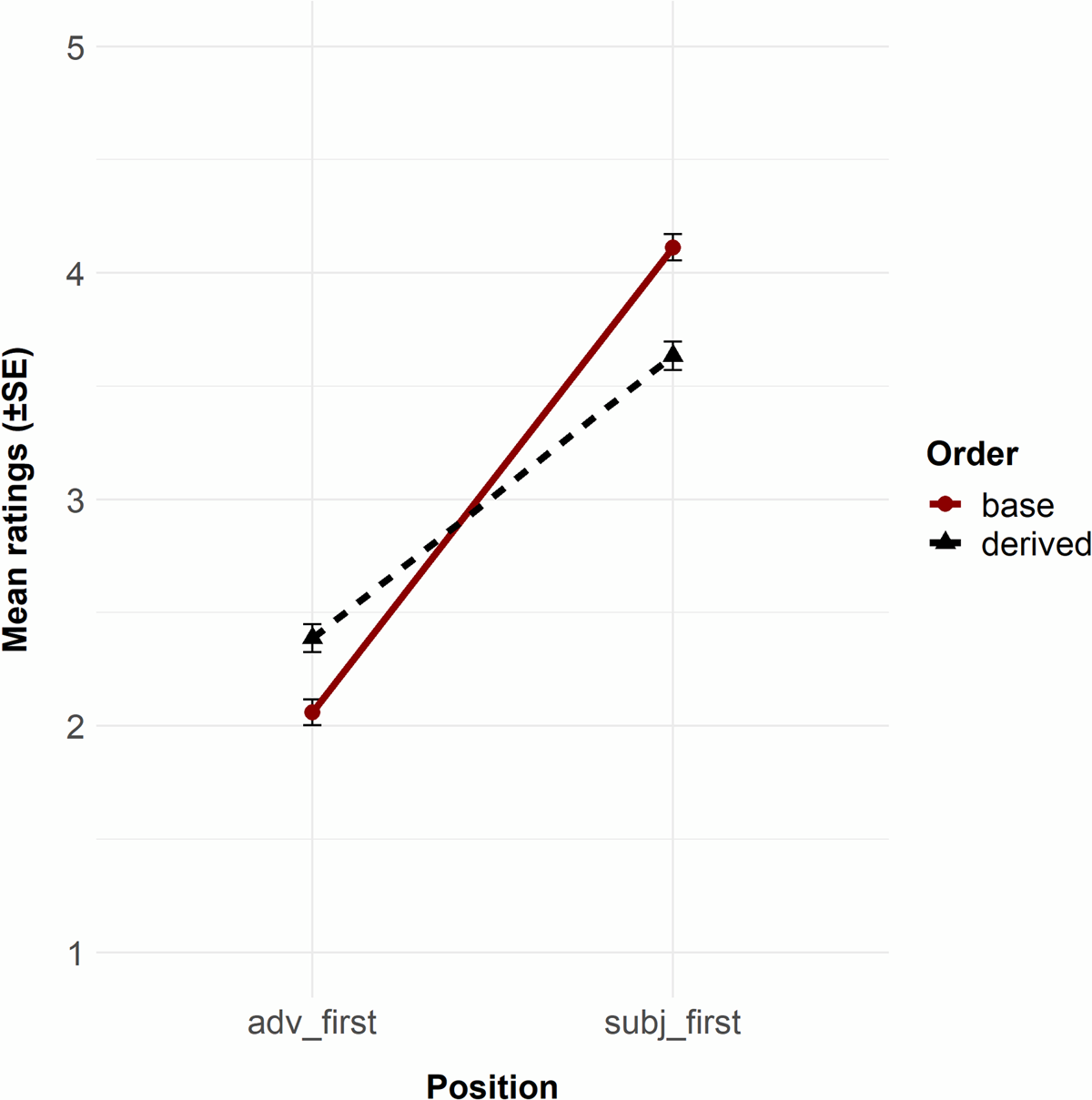

The mean acceptability ratings for the four conditions are given in Figure 2. The ratings were analyzed by means of a cumulative link mixed model (clmm). We entered the independent variables Position and Order as fixed factors, and subject and items as random intercept and slopes. Table 2 gives the model formula and the output with the maximal random effect structure supported by the data. We obtained p-values by Laplace approximation. The model shows a highly significant main effect for Position caused by a preference for the subject preceding the adverbials. Furthermore, the interaction of Position and Order was highly significant. As predicted, the derived order was rated higher in the pre-subject position, and the base order received higher ratings in the post-subject position. Order did not reach the level of statistical significance. Compared to the results of Experiment 1, the subject in a position preceding the adverbials improved ratings profoundly (condition ‘subj_first’: mean= 3.87, SD = 1.18).

Statistical analysis clmm of acceptability ratings.

| Formula: rating ~ order*position + (order*position | item) + (order*position | subject) | ||||

| Coefficient | SE | z-value | p | |

| Position | –3.61 | 0.4 | –9.02 | <.0001*** |

| Order | 0.25 | 0.19 | 1.31 | 0.19 |

| Position: Order | –2.1 | 0.4 | –5.28 | <.0001*** |

4.3 Discussion

As predicted by Hypothesis 2, we found an overall preference for the subject-first order. Ratings were significantly higher if the referential subject DP, a prototypical aboutness topic, was in the structural topic position preceding the sentence adverbial. We interpret this as evidence for the assumption that referential subject DPs are better candidates for topics than non-referential domain adverbials, and are therefore preferred in the medial topic position described by Frey (2004). The significant interaction between the factors Position and Order are in line with Hypothesis 3, assuming that the subject in topic position blocks the movement of the domain adverbial to this position. The base order of the adverbials (sentence adverbial > domain adverbial) received higher mean ratings when the topic position was filled with the subject, and the derived order (domain adverbial > sentence adverbial) was rated more acceptable when the subject has remained in situ below the adverbials. One can also conclude from this pattern of results that participants prefer sentences with a filled topic position. If the preferred sentence topic candidate, the subject, is not available because it remained in situ, the other discourse-structuring element, in this case, the domain adverbial, is preferred in this position. Our results also provide strong support for the Address first! principle proposed by Krifka (2008b), assuming that address-centered storage facilitates discourse management. This is reflected in the overall higher ratings for the subject-first sentences. Krifka also described the high positioning of delimitators as a strategy to signal that the following assertion only serves as a partial answer to the QUD. It thus seems reasonable to prefer discourse-structuring devices in a high, and hence early position, as this facilitates information packaging. Consequently, the attested movement of a discourse-structuring entity, i.e., the domain adverbial, to the designated medial topic position in the conditions with the subject below the adverbials seems to be preferred in order to facilitate information packaging.

5 General Discussion

Our experiments aimed to control for possible confounding factors that might have affected the order preferences for frame and sentence adverbials in Störzer & Stolterfoht (2013) and to experimentally test how the information-structural status of domain adverbials as delimitators affect order preferences for propositional adverbials. We presented evidence from two acceptability judgment experiments. Furthermore, we showed that the medial topic position is not restricted to referential subject DPs and frame adverbials with a referential internal argument, but also a suitable landing site for other discourse-structuring elements. We, therefore, replicated the results of Störzer & Stolterfoht (2013) with another type of frame adjunct, namely domain adverbials, which were realized as non-referential, adjectival adverbials, and therefore excluded referentiality of the internal argument as a possible confounding factor. Additionally, we found further evidence for the postulated base position of frame adjuncts below sentence adjuncts. More importantly, and similar to earlier studies, we attested a discrepancy between the online reading times for domain and sentence adverbials reported in Specht & Stolterfoht (2022) and the offline data reported in the current study. Movement of the domain adverbial across the sentence adverbial, i.e., the deviation from the base order, leads to an immediate processing cost, whereas the offline data in Experiment 1 revealed a preference for the derived order, an effect that can be plausibly explained by the described discourse-structuring principles. These principles, however, did not affect online sentence processing, which seems to be modulated by syntactic base order preferences only. These results are further evidence for a two-stage processing of single sentences without context, in which syntactic and semantic constraints affect processing immediately, and information structure is evaluated with delay.

We also argued that the low ratings in our first experiment were caused by a violation of the Address first! strategy described in Krifka (2008b), and that the preference for the derived order, on the other hand, reflects an information-structural preference, maintaining efficient discourse management. Domain adverbials can fulfill the function of delimitators. Therefore, the movement of domain adverbials to the medial topic position is preferred, at least in the absence of a structurally marked aboutness topic, and thus overrides the preference for the base order. This does not put the base position account for adverbials in jeopardy but shows that information-structural constraints can override syntactically-based preferences in a second processing step. Experiment 2 confirmed this hypothesis, the base order of the adverbials was preferred when the topic movement of the domain adverbial was inhibited by a referential subject, i.e., a prototypical aboutness topic, in the designated medial topic position.

Our findings are an essential piece to the puzzle of how adverbials are processed. Earlier studies on adverbial order processing showed that the base order of propositional adverbials affects processing immediately. With the current study, we present further evidence for the hypothesis that information-structural properties of the adverbials affect later processing stages since information-structural constraints were only visible in the offline data. Early processing stages are guided by syntactic and semantic information, and information-structural characteristics are processed with delay. We could not identify the point in time when information-structural processing starts. Therefore, an alternative explanation of the discrepancy of the online and offline data could be that the nature of the rating task forces participants to make sense of a somehow deviant structure. The domain adverbial, as a discourse-structuring element, was then interpreted as such only if participants were forced to evaluate the sentences. However, our results align with several neurocognitive studies on the interaction of context and word order during online processing of non-canonical ordering of complements in German. It has been shown that initial processing is guided by syntactic principles, whereas information-structural properties are only processed in later stages and on a global sentence level (Bader & Meng 1999; Paterson et al. 1999; Bornkessel et al. 2003; Stolterfoht 2005; Bornkessel & Schlesewsky 2006). The processing of propositional adverbials further supports a two-stage processing mechanism on sentence level.

In our experiments, participants were asked to rate a sentence without a preceding context. The question of how context interacts with adverbial order processing is subject to future research. With first results from the processing of frame adverbials, Störzer (2017) observed that topic marking of a frame adverbial by a preceding context facilitates online processing, but only in the spill-over region following the frame adverbial and not immediately on the region with the frame adverbial itself. What we can conclude from her and our findings is that without overt information-structural marking by a preceding context, first processing stages are guided purely by syntactic and semantic information. Information-structural processing might set in later because participants have to accommodate information-structural characteristics such as topicality, givenness, and delimitation when it is not explicitly marked by a preceding context. In cases where contextual information is available beforehand, processing can proceed in a forward-looking, anticipatory fashion to reduce processing cost (Altmann & Kamide 1999; Kaiser & Trueswell 2004).

To sum up, our results provide evidence for (i) two-stage processing on the level of single sentences, and (ii) the discourse-structuring effects of adverbial ordering, even in cases where referentiality of the internal argument and length are excluded as possible confounding factors.

Notes

- Evaluative sentence adverbials (e.g., unfortunately), however, differ profoundly in semantic aspects from the other two types. Evaluatives, in contrast to epistemics and evidentials, are veridical and thus presuppose factivity of the modified sentence. They are known to have different ordering preferences (Störzer 2017). [^]

- This observation is restricted to wide sentence scope of negation. Narrow scope with a contrastive focus accent on the domain adverbial is still possible. [^]

- Native speakers of German might be puzzled, because all four sentences do not exhibit the preferred order, which would be one with the adverbials following the referential subject DP. We will discuss this observation in section 3.3 and test hypotheses derived from this discussion with our second experiment. [^]

- An anonymous reviewer correctly pointed out, that – since the sentence (12d) is acceptable – it seems to be possible to have two topical constituents in the position above the sentence adverbial, but this requires the domain adverbial to be interpreted as a contrastive topic. Several psycholinguistic studies showed that participants preferentially assign wide focus readings to sentences without a preceding context during reading. Narrow and contrastive focus induced by a following context leads to costly focus structural and prosodic revision processes (see e.g., Bader 1998; Stolterfoht & Friederici & Alter & Steube 2007). We therefore assume that a sentence with one topical element is preferred over one with two topical elements. [^]

Abbreviations

clmm = cumulative link mixed model, delim = delimitator, epi = epistemic sentence adverbial, evi = evidential sentence adverbial, QUD = question under discussion, refl = reflexive, sadv = sentence adverbial, tadv = temporal adverbial, temp = temporal adverb

Data availability

Supplementary file 1: Appendix. Scientific data related to experiments 1 and 2. DOI: https://osf.io/8mcjg/?view_only=2a47e34cf6cb4cf4ad37badfe73a3300

Ethics and consent

The studies were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Psychological Research at the University of Tübingen (Stolterfoht_2021_0501_225). https://uni-tuebingen.de/en/faculties/faculty-of-science/faculty/advisory-boards/ethics-committee-of-the-faculty-of-science/

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Amelie Eisinger, Valentina Mayer, Tamara Stoyke, and Tabea Lange for their help with material construction and data collection in Experiment 1. Furthermore, we wish to thank Kerstin Dorothea Gösele, Franziska Sperling, Shuyue Yu, and Lin Zhang who helped with the construction of materials and data collection for Experiment 2. We would also like to thank Álvaro Cortés Rodríguez, Martin Schäfer and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that have significantly improved this paper. Finally, thank you to Tamara Stoyke for her support in proof reading and finalizing the article.

Funding information

The research reported here was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (project B8 of the SFB 833 “The Construction of Meaning”).

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Altmann, Gerry T. M. & Kamide, Yuki. 1999. Incremental interpretation at verbs: Restricting the domain of subsequent reference. Cognition 73(3). 247–264. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00059-1

Bader, Markus. 1998. Prosodic influences on reading syntactically ambiguous sentences. In Fodor, Janet Dean & Ferreira, Fernanda (eds.), Reanalysis in sentence processing (Studies in Theoretical Psycholinguistics 21), 1–46. Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9070-9_1

Bader, Markus & Meng, Michael. 1999. Subject-object ambiguities in German embedded clauses: An across-the-board comparison. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 28(2). 121–143. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023206208142

Bellert, Irena. 1977. On semantic and distributional properties of sentential adverbs. Linguistic Inquiry 8(2). 337–351. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4177988

Bornkessel, Ina & Schlesewsky, Matthias. 2006. The role of contrast in the local licensing of scrambling in German: Evidence from online comprehension. Journal of Germanic Linguistics 18(1). 1–43. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1470542706000018

Bornkessel, Ina & Schlesewsky, Matthias & Friederici, Angela D. 2003. Eliciting thematic reanalysis effects: The role of syntax-independent information during parsing. Language and Cognitive Processes 18(3). 269–298. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01690960244000018

Chafe, Wallace L. 1976. Givenness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics, and point of view. In Li, Charles N. & Thompson, Sandra A. (eds.), Subject and topic: A new typology of language, 27–55. New York: Academic Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ernst, Thomas. 2001. The Syntax of Adjuncts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511486258

Ernst, Thomas. 2004. Domain adverbs and the syntax of adjuncts. In Austin, Jennifer R. & Engelberg, Stefan & Rauh, Gisa (eds.), Adverbials: The interplay between meaning, context, and syntactic structure, 103–130. Amsterdam: Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.70.05ern

Frey, Werner. 2003. Syntactic conditions on adjunct classes. In Lang, Ewald & Maienborn, Claudia & Fabricius-Hansen, Cathrine (eds.), Modifying adjuncts, 163–209. Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110894646.163

Frey, Werner. 2004. A medial topic position for German. Linguistische Berichte 198. 153–190.

Frey, Werner & Pittner, Karin. 1998. Zur Positionierung der Adverbiale im deutschen Mittelfeld. Linguistische Berichte 176. 489–534. http://homepage.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/Karin.Pittner/FreyPittner98.pdf

Frey, Werner & Pittner, Karin. 1999. Adverbialpositionen im deutsch-englischen Vergleich. In Bierwisch, Manfred & Doherty, Monica (eds.), Sprachspezifische Aspekte der Informationsverteilung (Studia Grammatica 47), 14–40. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783050078137-002

Haftka, Brigitta. 2003. Möglicherweise tatsächlich nicht immer: Beobachtungen zur Adverbialreihenfolge an der Spitze des Rhemas. Folia Linguistica 37(1–2). 103–128. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/flin.2003.37.1-2.103

Haider, Hubert. 2000. Adverb placement: Convergence of structure and licensing. Theoretical Linguistics 26(1–2). 95–134. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/thli.2000.26.1-2.95

Jacobs, Joachim. 2001. The dimensions of topic-comment. Linguistics 39(4). 641–681 DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/ling.2001.027

Kaiser, Elsi & Trueswell, John C. 2004. The role of discourse context in the processing of a flexible word-order language. Cognition 94(2). 113–147. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2004.01.002

Krifka, Manfred. 2008a. Basic notions of information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55(3–4). 243–276. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1556/ALing.55.2008.3-4.2

Krifka, Manfred. 2008b. What do contrastive topics and frame setters have in common? The Role of Addressing and Delimitation in Information Structure. Talk presented at the Conference on Contrastive Information Structure Analysis (CISA) 2008, University of Wuppertal, March 18–19, 2008.

Maienborn, Claudia. 2001. On the position and interpretation of locative modifiers. Natural Language Semantics 9(2). 191–240. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012405607146

Paterson, Kevin B. & Liversedge, Simon P. & Underwood, Geoffrey. 1999. The influence of focus operators on syntactic processing of short relative clause sentences. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Section A 52(3). 717–737. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/713755827

Peirce, Jonathan & Gray, Jeremy R. & Simpson, Sol & MacAskill, Micheal & Höchenberger, Richard & Sogo, Hiroyuki & Kastman, Erik & Lindeløv, Jonas Kristoffer. 2019. PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behavior Research Methods 51(1). 195–203. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y

Pittner, Karin. 1999. Adverbiale im Deutschen: Untersuchungen zu ihrer Stellung und Interpretation. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Pittner, Karin. 2004. Where syntax and semantics meet: Adverbial positions in the German middle field. In Austin, Jennifer R. & Engelberg, Stefan & Rauh, Gisa (eds.), Adverbials: The interplay between meaning, context and syntactic structure, 253–287. Amsterdam: Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.70.09pit

Reinhart, Tanya. 1981. Pragmatics and linguistics: An analysis of sentence topics. Philosophica 27. 53–94. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21825/philosophica.82606

Repp, Sophie. 2017. Structural topic marking: Evidence from the processing of grammatical and ungrammatical sentences with adverbs. Lingua 188. 53–90. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2016.09.002

Roberts, Craige. 1996. Information structure in discourse: Towards a unified theory of formal pragmatics. Ohio State University Working Papers in Linguistics 49. 91–136.

Rösler, Frank & Pechmann, Thomas & Streb, Judith & Röder, Brigitte & Hennighausen, Erwin. 1998. Parsing of sentences in a language with varying word order: Word-by-word variations of processing demands are revealed by event-related brain potentials. Journal of Memory and Language 38(2). 150–176. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.1997.2551

Salfner, Fabienne. 2018. Semantik und Diskurssstruktur: Die mäßig-Adverbiale im Deutschen (Studien zur Deutschen Grammatik 96). Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Schäfer, Martin. 2013. Positions and interpretations: German adverbial adjectives at the syntax-semantics interface (Trends in Linguistics, Studies and Monographs (TiLSM) 245). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110278286

Specht, Larissa & Stolterfoht, Britta. 2022. Incrementality in the processing of adverbial order variations in German. In Featherston, Sam & Hörnig, Robin & Konietzko, Andreas & von Wietersheim, Sophie (eds.), Proceedings of Linguistic Evidence 2020: Linguistic Theory Enriched by Experimental Data. Tübingen: Universität Tübingen.

Steube, Anita. 2006. The influence of operators on the interpretation of DPs and PPs in German information structure. In Molnár, Valéria & Winkler, Susanne (eds.), The architecture of focus (Studies in Generative Grammar 82), 489–516. Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110922011.489

Steube, Anita. 2014. Satzadverbien, Satznegation und die sie umgebenden Kontextpositionen. In Assmann, Anke & Bank, Sebastian & Georgi, Doreen & Klein, Timo & Welsser, Philipp & Zimmermann, Eva (eds.), Topics at InfL (Linguistische Arbeitsberichte 92), 561–580. Leipzig: Institut für Linguistik, Universität Leipzig.

Stolterfoht, Britta. 2005. Processing word order and ellipses. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences dissertation. http://hdl.handle.net/11858/00-001M-0000-0010-D2DB-1

Stolterfoht, Britta & Frazier, Lyn & Clifton, Charles, Jr. 2007. Adverbs and sentence topics in processing English. In Featherston, Sam & Sternefeld, Wolfgang (eds.), Roots: Linguistics in search of its evidential base (Studies in Generative Grammar 96), 361–374. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110198621.361

Stolterfoht, Britta & Friederici, Angela D. & Alter, Kai & Steube, Anita. 2007. Processing focus structure and implicit prosody during reading: Differential ERP effects. Cognition 104(3). 565–590. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.08.001

Stolterfoht, Britta & Gauza, Holger & Störzer, Melanie. 2019. Incrementality in processing complements and adjuncts: Construal revisited. In Carlson, Katy & Clifton, Charles, Jr. & Fodor, Janet Dean (eds.), Grammatical approaches to language processing: Essays in honor of Lyn Frazier (Studies in Theoretical Psycholinguistics 48), 225–240. Cham: Springer International Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01563-3_12

Störzer, Melanie. 2017. Weshalb auf Mallorca wahrscheinlich alle Urlauber betrunken sind: Zur syntaktischen Position von Frameadverbialen und der Rolle der Informationsstruktur bei ihrer Verarbeitung. Tübingen: Universität Tübingen dissertation. DOI: http://doi.org/10.15496/publikation-20900

Störzer, Melanie & Stolterfoht, Britta. 2013. Syntactic base positions for adjuncts: Psycholinguistic studies on frame and sentence adverbials. Questions and Answers in Linguistics 1(2). 57–72. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/qal-2015-0004

Störzer, Melanie & Stolterfoht, Britta. 2018. Is German discourse-configurational? Experimental evidence for a topic position. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3(1): 20. 1–24. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.122