1 Introduction

Ahn (2012) and Sauerland (2014) first observed that proportional measurement (PM) phrases (proportions), namely fractions (e.g. two thirds in (1a)) and percentages (e.g. seventy percent in (1b)), exhibit an interesting property when they are part of a sentence: the restrictor and the predicate can be switched by minimal morpho-syntactic modifications, beyond word order variations. This phenomenon is exemplified for English percentages by (2a) and (2b): dropping of the in (2b) leads to the switch of restrictor and predicate, as illustrated by the two free translations. In turn this fact poses a challenge for the current understanding of determiners semantics. This observation began an ongoing thread of research by Sauerland and colleagues which produced already a detailed and systematic description of PM structures in Korean and in German, as well as possible formal models of how the reversal could come about (Ahn & Sauerland 2015a; b; 2017; Pasternak & Sauerland 2022, from now on S&co).

- (1)

- a.

- two thirds of [the nurses]

- b.

- seventy percent of [the nurses]

- (2)

- a.

- The hospital hired seventy percent of [the nurses].

- ‘The hospital hired seventy percent of [the nurses].’

- b.

- The hospital hired seventy percent nurses.

- ‘Seventy percent of the people hired by the hospital are nurses.’

The present article contributes to this recent research line providing the first detailed empirical description of the morpho-syntax and interpretation of Italian PM structures observed through the restrictor and predicate reversal phenomena lens.

These Italian structures are discussed in Falco & Zamparelli (2019: §4) and in Falco & Zamparelli (Submitted), however in those analyses the reversal phenomena were not considered. Following the terminology adopted in Falco & Zamparelli (2019: §4), we will designate the nouns inside the square bracket as inner nominals and their determiners as the inner determiners.1 The fraction nominal (thirds) and the percent adverb (percent) will be referred to as outer nominals, and the numerals two and seventy will be simply called numerals. Exploring the Italian data, sometimes we will see also a determiner on the left of the numerals, and this will be called the outer determiner.

While in Korean overt quantifier floating and in German case are the morpho-syntactic markers for the restriction and predicate switch, a detailed investigation of Italian shows five different morpho-syntactic factors: definiteness of the inner nominal, definiteness of the outer determiner, pre-V or post-V position (as direct or indirect object, or as post-verbal subject) in the main clause, but not in subordinate clauses, verb agreement with the entire PM DP or with its inner noun. Furthermore, while Korean and German both require contrastive focus on the PM DP for the non-conservative interpretation according to S&co, Italian shows the role of three different interpretive factors: accessibility of the complement set of the inner noun, type of predicate in the clause, and given or new information status of the PM DP.

The interpretation of PM structures, like any other quantifier structure, depends on which phrase is interpreted as restrictor and which phrase is interpreted as predicate. Generally, restrictor and predicate are determined by their linear position and inverting their order produces sentences with completely different meanings as shown for Italian and for the English translations in (3): while (3a) is plausible, (3b) is definitely false.2

- (3)

- a.

- Due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- degli

- of the

- infermieri

- nurses

- sono

- are

- donne.

- women

- ‘Two thirds of the nurses are women.’

- b.

- Due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- delle

- of the

- donne

- women

- sono

- are

- infermiere.

- nursesF.PL

- ‘Two thirds of the women are nurses.’

The omission of the definite determiner preceding the inner noun women in the Italian example brings about the reversed interpretation in (4b), as the translation shows: people hired, that is the set denoted by the predicate hired, is interpreted as restrictor of two thirds, while women is interpreted as its predicate, even though it linearly comes after people hired and it is adjacent to the percentage it is not interpreted as its restrictor (cf. Ahn & Sauerland 2015b: ex.20).3

- (4)

- a.

- L’ospedale

- the hospital

- ha

- has

- assunto

- hired

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- delle

- of the

- donne.

- women

- ‘The hospital has hired two thirds of the women.’

- b.

- L’ospedale

- the hospital

- ha

- has

- assunto

- hired

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- donne.

- women

- ‘Two thirds of the people hired by the hospital are women.’

The reversed interpretation we just saw (4b) is limited to PM phrases.4 In sentences containing absolute measure phrases (e.g. un centinaio ‘about a hundred’), the same definite and indefinite alternation is possible (5), but it is impossible to detect a reversal of restriction and predicate in the presence of an indefinite inner noun, as indicated in the translation of (5b).

- (5)

- a.

- L’ospedale

- the hospital

- ha

- has

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- centinaio

- about a hundred

- delle

- of the

- donne.

- women

- ‘The hospital has hired about one hundred of the women.’

- b.

- L’ospedale

- the hospital

- ha

- has

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- centinaio

- about a hundred

- di

- of

- donne.

- women

- ‘The hospital has hired about one hundred of women.’

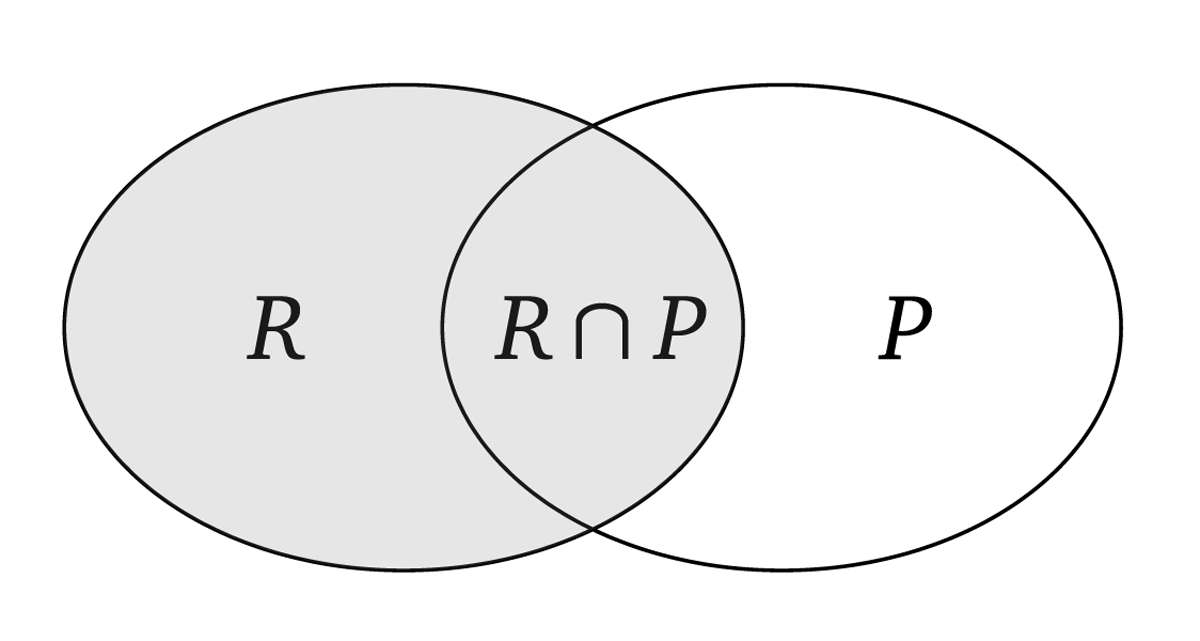

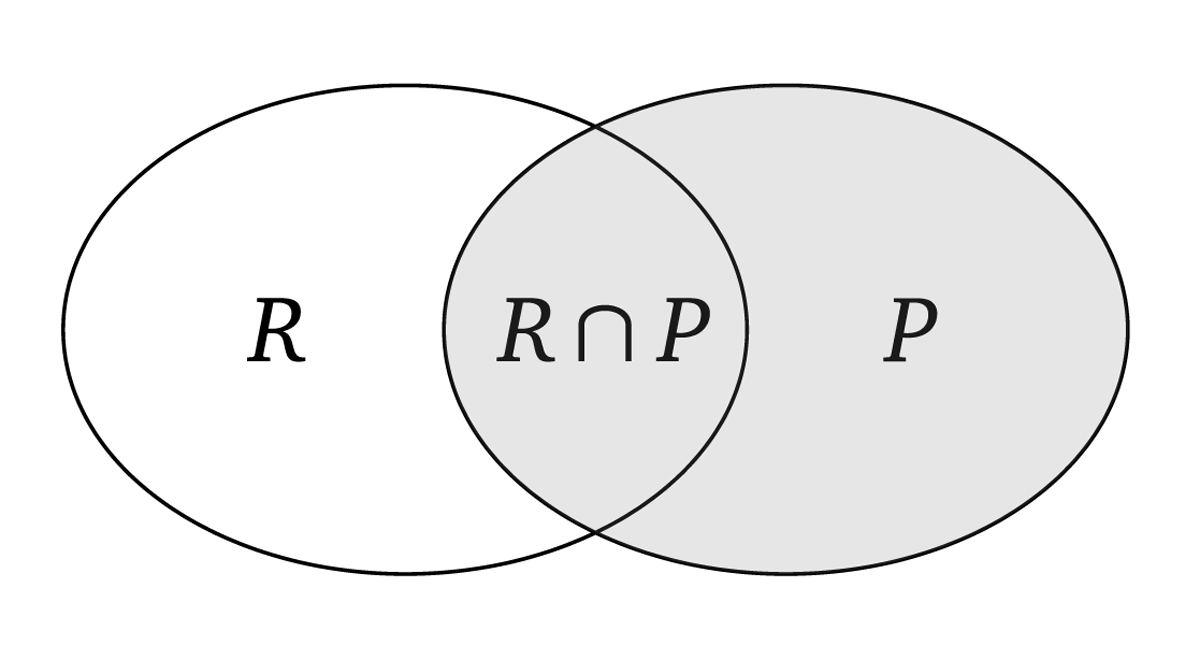

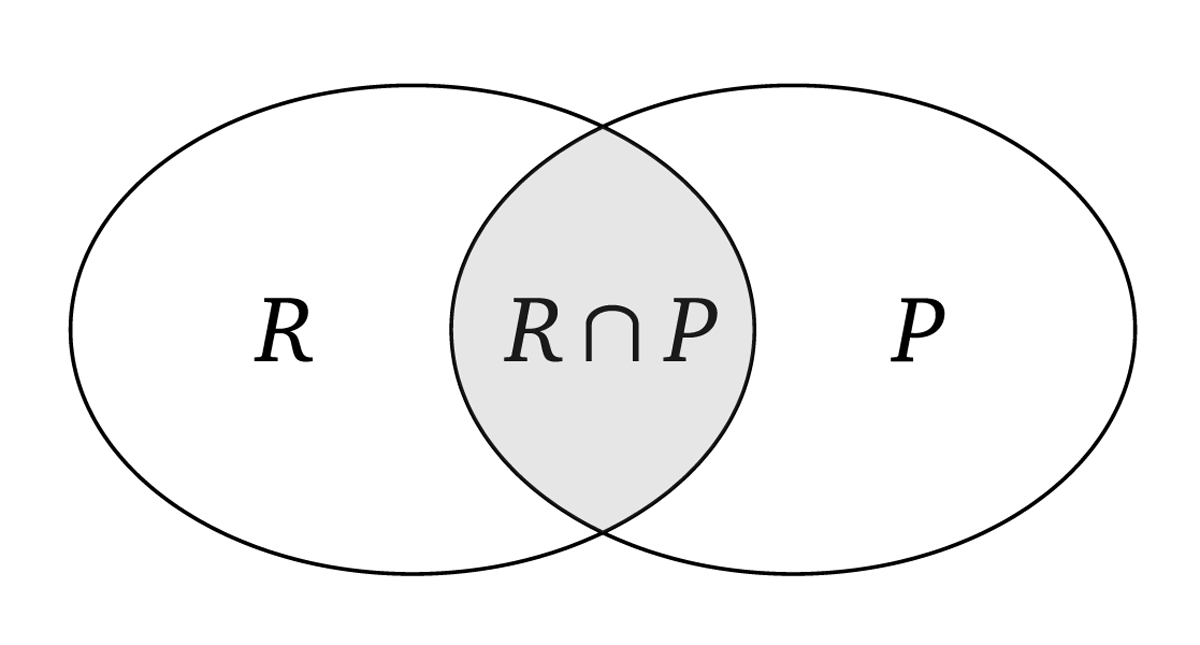

At first glance, it may seem that an ad-hoc structure for PM phrases (4), different from absolute measurement phrases (5), is necessary to account for the difference in terms of reversal. Actually, the different semantics of the two structures explains this difference thus pointing to structural uniformity (Ahn & Sauerland 2015a: §§2.2). As represented in the figures below, the two construals of a PM such as (4) consider the relation between the intersection of the restrictor (R) and the predicate (P) sets to either one of the two, namely for (4a) Figure 1 and for (4b) Figure 2. However for an absolute measure, be it with a definite or indefinite inner noun, only the intersection itself enters the truth-conditions as shown by Figure 3. Therefore, we can assume that the structure of relative and absolute measure phrases is the same and the structural and interpretive mechanism at play in (4b) are at play also in (5b), but apply vacuously, without producing an interpretive difference. In any case, the systematic presence of reversed readings (4b) raises the question of how to derive their interpretation from the syntax/semantics.

Reversed interpretations cases such as (4b) are crucial for our understanding of determiners interpretation and quantification in general, as they seem counterexamples to the so called conservativity universal (6c), proposed by Keenan & Stavi (1986: 260): conservativity is a property that could restrict the range of functions denoted by determiners. This property is illustrated for the determiner every by the informal equivalence (6a), formalised in (6b).

- (6)

- a.

- Every determiner is conservative = Every determiner is a conservative determiner

- b.

- Conservativity = A function f is conservative iff for all R, P: f(R)(P) = f(R)(R ∩ P)

- c.

- Conservativity universal: all determiners in natural languages denote conservative functions

In simple words, (6b) means that in order to determine whether f(R)(P) is true or false, we do not need to look at those entities in set P that are not in set R, that is all that matters is the entities in R. For example, in evaluating the sentence every determiner is conservative in (6a), all needs to be considered is the entities in the set of determiners: if all of them are also in the set of conservative entities, the sentence is true, otherwise it is false. In other words, the entities that are not in the set of determiners do not matter for the truth or falsity of this sentence. Sentences involving linearly interpreted PM phrases and absolute measure phrases behave like sentences containing every with respect to conservativity. In order to interpret (4a) and (5a)–(5b), we can zoom in the set of women only (set R in Figure 1 and in Figure 3). Therefore, the determiners occurring in these sentences obey and support the conservativity universal. Instead, the determiners appearing in reversely interpreted sentences, at least apparently, contradict the conservativity universal. In order to evaluate (4b), we need to look beyond the set of women, at non-women in the set of people hired (set P in Figure 2). Given this difference with respect to conservativity, the reversed interpretations are named non-conservative and the linear non-reversed interpretations conservative.5 In summary, the non-conservative case poses an issue for the conservativity universal and raises the question if it is actually invalid and should be discarded, or if the non-conservative cases actually respect conservativity, through invisible structure and rearrangement operations at the syntax/semantics interface. Crucially, the posited structure and operations need to be substantiated by morpho-syntactic evidence to be gathered by looking at how (non-)conservativity is marked cross-linguistically.

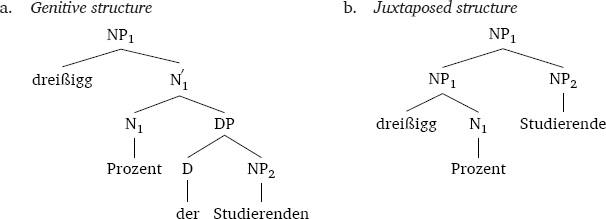

Until the present special issue, non-conservative interpretations with PM have been systematically investigated only in Korean and in German (S&co). In these two languages quantifier floating and case marking respectively play a crucial role in determining the two interpretations. For example Ahn & Sauerland (2017: p.219) report the following distinction in German between genitive conservative (7a) and nominative non-conservative (7b) measurement structures with proportions.

- (7)

- a.

- Genitive, conservative

- Dreißig

- thirty

- Prozent

- percent

- der

- theGEN

- Studierenden

- studentsGEN

- arbeiten.

- work

- ‘Thirty percent of the students work.’

- b.

- Nominative, non-conservative

- Dreißig

- Thirty

- Prozent

- percent

- [Studierende]FOC

- [studentsNOM]FOC

- arbeiten

- work

- hier.

- here

- ‘Thirty percent of the workers here are students.’

Semantically, according to S&co, the distinction between the linear and the reversed interpretation correlates also with a necessary difference in focus placement: the reversed interpretation requires contrastive focus on the inner noun (marked with subscript FOC in (7b)), while the linear interpretation allows different focus positioning. This fact plays an important role in S&co analysis. Nevertheless, it does not hold in Italian where new information focus, conveying which part of the sentence contributes new information, is instead at play. In particular, the PM DP must be part of the new information focus in order to get a non-conservative interpretation.

As we saw in the examples above with fractions (4a) vs. (4b) Italian marks the distinction through the presence or absence of a definite determiner on the inner noun. The facts are more complex and interesting when we consider also percentages, the second type of PM structures. In fact, Italian percentages require an overt definite or indefinite outer determiner (8), differently from English, as noted in Falco & Zamparelli (2019: ex.55).6

- (8)

- {il

- {the

- /

- /

- un

- a

- /

- /

- *∅}

- *∅}

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

In turn the definite and indefinite alternation of the outer determiner affects the possibility of the inner noun (studenti) to be indefinite, and thus exhibit a non-conservative interpretation. As a matter of fact, di is unacceptable in (9a) when it is preceded by a definite article, and it is possible only in (9b).7

- (9)

- a.

- il

- the

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- {*di

- {of

- /

- /

- degli}

- of the}

- italiani

- Italians

- b.

- un

- the

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- {di

- {of

- /

- /

- degli}

- of the}

- italiani

- Italians

Looking beyond the DP level, according to my informants and contrary to Ahn & Sauerland (2017: ex.44), in Italian only post-V indefinite percentages with an indefinite inner noun get a non-conservative construal, while sentences with the same percent DPs placed in pre-V position are marginally acceptable with neutral intonation and get a conservative construal (10), as shown by the free translation.

- (10)

- ?Un

- a

- sessanta

- sixty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- donne

- women

- ha

- has

- superato

- passed

- l’esame. Conservative

- the exam

- ‘About sixty percent of the women passed the exam.’

Furthermore, in the indefinite cases, singular masculine agreement with the whole DP is much preferred ((11a) vs. (11b)), so that (11b) with feminine plural agreement with the inner noun is marginal. Furthermore, to the extent that agreement with the inner noun could be accepted, it erases the non-conservative interpretation reinstating the conservative construal. In other words, in (11b) agreement with the inner noun makes di donne (‘of women’) interpretively equivalent to delle donne (‘of the women’).8

- (11)

- a.

- Non-conservative, PM DP agreement

- È

- is

- stato

- beenM.SG

- assunto

- hiredM.SG

- [[un

- [[a

- terzo]

- third]M.SG

- di

- of

- donne].

- womenF.PL]M.SG

- ‘One third of the people hired here are women.’

- b.

- Conservative, inner noun agreement

- ??Sono

- were

- state

- beenF.PL

- assunte

- hiredF.PL

- [[un

- [[a

- terzo]

- third]M.SG

- di

- of

- donne].

- womenF.PL]M.SG

- ‘One third of the women were hired.’

Finally, looking beyond the simple clause into complex sentences, proportions with an indefinite inner noun extracted from a relative clause get a non-conservative interpretation with an object, but crucially also with a subject relative clause (12), again with a strong preference for singular verb agreement with the whole PM DP. Note that here the non-conservative construal is confined in the relative clause itself.9

- (12)

- Il

- [the

- sessanta

- sixty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- donne

- womenPL]SG

- che

- who

- ha

- hasSG

- superato

- passed

- l’esame

- the exam

- scritto

- written

- ha

- hasSG

- superato

- passed

- anche

- also

- l’orale.

- the oral

- ‘Sixty percent of all people who passed the exam were women and those women passed also the oral exam.’

To summarise, the five morpho-syntax factors determining the interpretation of Italian PM structures were introduced: the (in-)definiteness of inner determiner, the (in-)definiteness of the outer determiner, the position of the PM DP with respect to the verb in main clauses, the verb agreement with the inner noun or with the entire PM DP, and the irrelevance of the position of the PM DP in subordinate clauses (Table 1).

Morpho-syntactic factors and conservative/non-conservative interpretations.

| Morpho-syntactic factors | Conservative interpretation | Non-Conservative interpretation |

| 1. inner noun determiner | definite | absent |

| 2. outer noun determiner | definite | absent/indefinite |

| 3. main clause position | pre-V | post-V |

| 4. verb agreement | inner noun | whole DP |

| 5. subordinate clause position | pre-V or post-V | pre-V or post-V |

Apart from the morpho-syntactic factors peculiar of Italian which are the focus of the present contribution, we will see that three other factors, traditionally pertaining to other linguistic domains, affect the (non-)conservative interpretation: the lexical semantics of the inner noun, the lexical semantics of the predicate of the clause containing the PM DP, and the information status of the PM DP in the sentence (Table 2).

Non morpho-syntactic factors and conservative/non-conservative interpretations.

| Non morpho-syntactic factors | Conservative interpretation | Non-Conservative interpretation |

| 1. inner noun lexical semantics | inaccessible complement set | accessible complement set |

| 2. predicate lexical semantics | individual-level | stage-level |

| 3. focus | given information | new information |

In order to get the non-conservative construal all the eight factors listed under the relevant column must be fulfilled, in other words whenever at least one of the factors is not fulfilled the conservative construal prevails. As we have already seen in some of the examples introduced so far, the eight factors display mutual interactions and entailments which are to be uncovered and which a satisfactory account should explain.

Methodologically, since some of the judgements which constitute the empirical basis for the generalisations are not clear-cut, six Italian native speakers from four different Italian regions (Lazio, Lombardy, Sicily, Tuscany) were asked to judge the examples proposed throughout the paper.

In the rest of the article, each of the listed factors is analysed in detail. Preliminarily, the background on the morpho-syntax of Italian measures structures in general (§2) and specifically on fractions (§§2.2) and on percentages (§§2.3) is laid off as the basis for the discussion. Then the factors affecting conservativity at the DP level are described (§3): §§3.1 shows how the definiteness of the inner and outer determiners shape the conservative and non-conservative interpretations, which can be facilitated by the inner noun lexical semantics, while §§3.2 presents data on complex inner NPs including an adjective which highlights how contrastive focalisation interacts with conservativity, but is orthogonal to it. After the intra PM DP level, the paper looks outside of the PM DP by placing it in the context of the simple clause (§4), where the predicate lexical semantics becomes relevant. §§4.1 discusses the role of the position of the PM DP with respect to the verb and relates the position to the information status the PM DP gets, while §§4.2 shows how verb agreement affects (non-)conservativity in the simple clause. At this point we further zoom out of the simple clause and look at PM DPs in the context of complex sentences with a relative clause, where the indefiniteness and the position requirements, seen in simple clauses, become irrelevant (§§5). §§5.1 presents the effects of verb agreement in relative clauses, while §§5.2 describes the interaction between (non-)conservativity and contrastive focus in complex sentences. The final section (§6) illustrates why current theories of PM structures fail to fully account for the uncovered generalisations, but they offer a solid ground for building a comprehensive account of the Italian data.

2 Background on Italian proportions

In this section the background on Italian measure structures, both absolute and relative, is introduced with a gradual approach. We begin presenting Italian relative measure structures in relation to absolute measure and to counting structures §§2.1. At this level, the forms that simple measure phrases can take are considered abstracting away from the restrictions some of them impose on the DP internal syntax and on the DP external syntax. DP internal syntax refers to requirements the simple measure phrases impose on the syntactic form of the wider DPs they belong to. For example, we will see that some definite measure phrases require a modifier attached to them. DP external syntax refers to how these DPs themselves interact with the whole clause or sentence where they appear. We will see that this brings up the issue of the of conservative vs. non-conservative construals at the centre of this paper. The lexical meaning of fractions DPs and of percent DPs are described in §§2.2 and in §§2.3 respectively, taking into account also the DP internal restrictions they impose. The DP external syntax of PM structures will be the topic of the subsequent sections.

2.1 Measurement structures

Paradigmatic measurement structures involve mass nouns (water, sugar, rice, …) and measure terms (13) or container nouns (14) or classifiers (15) plus numeral modifiers. Plural measurements structures, as indicated by the determiners in round parenthesis in the three examples, can be bare, without an overt definite article, or they can preceded by a definite plural or indefinite determiner. When the indefinite determiner un introduces a counting structure, it has a meaning of approximation which can be expressed in English by the adverb about, but it has the grammatical role of the determiner, as shown in the translations and glossae respectively.10 Here the possible forms are listed abstracting away from the requirements some forms impose on the wider DP they occur in. Given the appropriate structural context, all the four combinations of the outer and inner, definite and indefinite determiners are possible.11

- (13)

- Measure term

- a.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- litri

- liters

- di

- of

- acqua

- water

- ‘(the) two liters of water’

- b.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- litri

- liters

- di

- of

- acqua

- water

- ‘(about) two liters of water’

- c.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- litri

- liters

- dell’acqua

- of the

- water

- ‘(the) two liters of the water’

- d.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- litri

- liters

- dell’acqua

- of the

- water

- ‘(about) two liters of the water’

- (14)

- Container noun

- a.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- cucchiaini

- teaspoons

- di

- of

- zucchero

- sugar

- ‘(about) two teaspoons of sugar

- b.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- cucchiaini

- teaspoons

- di

- of

- zucchero

- sugar

- ‘(about) two teaspoons of sugar

- c.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- cucchiaini

- teaspoons

- dello

- of the

- zucchero

- sugar

- ‘(the) two teaspoons of the sugar

- d.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- cucchiaini

- teaspoons

- dello

- of the

- zucchero

- sugar

- ‘(about) two teaspoons of the sugar

- (15)

- Classifier

- a.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- chicchi

- grains

- di

- of

- riso

- rice

- ‘(the) two grains of rice

- b.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- chicchi

- grains

- di

- of

- riso

- rice

- ‘(about) two grains of rice

- c.

- (i)

- (a)

- due

- two

- chicchi

- grains

- del

- of the

- riso

- rice

- ‘(about) two grains of the rice

- d.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- chicchi

- grains

- del

- of the

- riso

- rice

- ‘(about) two grains of the rice

Quantities of plural count nouns can be counted as well, as illustrated in (16): the classifier (boxes) repackages pluralities into higher order entities which can be counted.12

- (16)

- Classifier and count noun

- ({le

- ({the

- /

- /

- un})

- a})

- due

- two

- scatole

- boxes

- di

- of

- libri

- books

- ‘({the / about}) two boxes of books’

Measurements structures in Italian and in English contrast with simple counting structures which typically involve count nouns (cats, books, …) and numeral modifiers directly modifying the count nouns as in (17).

- (17)

- Count noun

- ({i

- ({the

- /

- /

- un})

- a})

- tre

- three

- gatti

- cats

- /

- /

- libri

- books

- ‘({the / about}) three cats / books’

Counting structures involving a substance expressed by mass nouns are ungrammatical with a basic counting meaning (18a). However, mass nouns are possible in prima facie counting structures when they receive a kind interpretation (18b), namely types of sugar and types of rice (as shown by the translation of (18b)) and the counting operation applies to these higher order entities. This shift through the presence of a silent classifier (types) in (18b) makes it parallel to the classifier measure structure with a mass noun (15) above. Therefore, the same DP in the two structures below is ungrammatical as a basic counting structure (18a), but it is acceptable as an absolute measurement structure (18b) involving a silent classifier.13

- (18)

- a.

- Mass noun

- *({i

- ({the

- /

- /

- un})

- a})

- tre

- three

- zuccheri

- sugars

- /

- /

- risi

- rices

- ‘({the / about}) three sugars / rices’

- b.

- Mass noun, kind interpretation

- ({i

- ({the

- /

- /

- un})

- a})

- tre

- three

- zuccheri

- sugars

- /

- /

- risi

- rices

- ‘({the / about}) three types of sugar / types of rice’

To summarise, counting structures involve count nouns whereas absolute measure structures involve mass nouns. If a count noun appears in an absolute measure structure, it must be repackaged into a higher order entity through a classifier (16).14 When a mass noun appears in a count structure, a silent classifier can be present at the interpretive level, thus shifting it from a counting structure (18a) into an absolute measure structure (18b).

Proportional (or relative) measurements are a special type of measurements where the measure is expressed in proportion to the quantity of the inner noun, instead of being expressed in absolute terms. PM come in two varieties: fractions (19) and percentages (20).

- (19)

- Fraction of mass noun

- a.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- acqua

- water

- ‘(the) two thirds of water’

- b.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- acqua

- water

- ‘(about) two thirds of water’

- c.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- dell’acqua

- of the water

- ‘(the) two thirds of the water’

- d.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- dell’acqua

- of the water

- ‘(about) two thirds of the water’

- (20)

- Percentage of mass noun

- a.

- il

- the

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- acqua

- water

- ‘the twenty percent of water’

- b.

- un

- a

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- acqua

- water

- ‘about twenty percent of water’

- c.

- il

- the

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- dell’acqua

- of the water

- ‘the twenty percent of the water’

- d.

- un

- a

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- dell’acqua

- of the water

- ‘about twenty percent of the water’

Fractions (21) and percentages (22) similarly to absolute measurements can both involve also count nouns. However, differently from absolute measurements which must combine with a measure term or a classifier in order to be measured, proportional measures, thanks to their proportional nature, can combine directly with count nouns and do not require a (overt or covert) classifier to be measured (21): {di / degli} italiani (‘{of / of the} Italians’) does not refer to types of Italians and it is perfectly formed.

- (21)

- Fraction of count noun

- a.

- (i)

- (the)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘(the) two thirds of Italians’

- b.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘(about) two thirds of Italians’

- c.

- (i)

- (i)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- degli

- of the

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘(the) two thirds of the Italians’

- d.

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- degli

- of the

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘(about) two thirds of the Italians’

- (22)

- Percentage of count noun

- a.

- il

- the

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘the twenty percent of Italians’

- b.

- un

- (a)

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘about twenty percent of Italians’

- c.

- il

- the

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- degli

- of the

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘the twenty percent of the Italians’

- d.

- un

- a

- venti

- twenty

- percento

- percent

- degli

- of the

- italiani

- Italians

- ‘about twenty percent of the Italians’

2.2 Structure of fraction DPs

Italian fractions are masculine nouns referring to the numerator of a fraction, while the fraction name is derived from its denominator.15 For example, for the fraction noun quinto (‘fifth’) the denominator is the number five from Latin quinque.16 As NPs fractions exhibit a productive inflectional morphology and can be singular (23a) or plural (23b). Syntactically, the singular fraction NP is postponed to a singular indefinite article (23a), while the plural fraction NP must be combined with a numeral expressing an integer equal to or greater than 2 (23b). In both cases, the DP formed with the numeral can be part of a more complex one, including an inner noun with or without determiner inside a prepositional phrase ({di / degli} studenti ‘{of / of the} students’) in (23a) and (23b)).

- (23)

- a.

- (*un)

- about

- un

- a/one

- quinto

- fifth

- ({di

- ({of

- /

- /

- degli}

- of the}

- italiani)

- Italians)

- b.

- (un)

- (about)

- due

- two

- quinti

- fifthsPL

- ({di

- ({of

- /

- /

- degli}

- of the}

- italiani)

- Italians)

In addition to the bare cases illustrated in (23a) and (23b), fractions (plus numeral) can be preceded by various determiners. Interestingly, between the determiners choice on the main DP and on the inner noun inside the PP there is a relation subject to restrictions banning some combinations. Singular fractions can be preceded by a definite article or demonstrative instead of the indefinite article, but in this case the inner nouns must be definite (24a).17 Also plural fractions can be preceded by a plural definite or demonstrative determiner and also in this case the inner noun must be definite. Contrary to the case of singular fractions (24a), an integer must be present after the definite plural determiners or the determiner becomes ill-formed (due ‘two’ in (24b)). Note that in (24a) un (‘a’) must be omitted because it is totally recoverable from the morphology of the singular fraction quinto (‘fifth’), whereas in the morphology of the plural fraction in (24b) quinti (‘fifths’) is compatible with an infinite number of numbers, therefore the number must be obligatorily specified.

- (24)

- a.

- {il/l’

- {the/the

- /

- /

- quel}

- that}

- (*un)

- (a)

- quinto

- fifth

- (degli

- (of the

- italiani)

- Italians)

- b.

- {i

- {thePL

- /

- /

- quei}

- those}

- *(due)

- *(two)

- quinti

- fifth

- (degli

- (of the

- italiani)

- Italians)

Getting back to inflectional morphology, when definite determiners appear in Italian fractions they must agree in gender and number with the denominator noun quinti in (25), which means that they are masculin plural.

- (25)

- {i

- {theM.PL

- /

- /

- *il

- theM.SG

- /

- /

- *le

- theF.PL

- }

- }

- due

- two

- quinti

- fifthsM.PL

- delle

- of_the

- donne

- women

As we saw, when the whole fraction DP is headed by a definite or by a demonstrative determiner, the inner NP must necessarily be headed by a definite determiner. Actually, in these cases also an indefinite with a modifier, typically a relative clause, produces a grammatical result (26a) and (26b). This is due to the semantics of the definite article, which comes with a familiarity (among others Heim 1982) and uniqueness (among others Russell 1905) requirement. As originally noted by Kayne (1994: Ch.8) and discussed by Barker (1998) and Zamparelli (1998), the presence of the relative clause allows for these two requirements to be met, even in the absence of a definite determiner on the inner noun.18

- (26)

- a.

- {il

- {the

- /

- /

- quel}

- that}

- *(un)

- (a)

- quinto

- fifth

- di

- of

- studenti

- students

- *(che

- (that

- ha

- has

- superato

- passed

- l’esame)

- the exam)

- b.

- {i

- {thePL

- /

- /

- quei}

- those}

- due

- two

- quinti

- fifth

- di

- of

- studenti

- students

- *(che

- (that

- hanno

- have

- superato

- passed

- l’esame)

- the exam)

2.3 Structure of percent DPs

Italian percento, also spelled per cento, lexically is an adverbial locution with the same meaning as English percent, that is every one hundred. Syntactically, percento is postponed to a number (dieci ‘ten’ in (27)) which in Italian must be preceded by a determiner to form a DP. This DP can be part of a more complex one, including an inner noun inside a prepositional phrase (degli studenti) (27a). Morphologically, as an adverbial locution percento does not exhibit productive inflectional morphology (27b).19

- (27)

- a.

- {il

- {the

- /

- /

- quel}

- that}

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- (degli

- (of the

- studenti)

- students)

- b.

- *{i

- {thePL

- /

- /

- quei}

- thosePL}

- dieci

- ten

- percenti

- percentsPL

- (degli

- (of the

- studenti)

- students)

In addition to the definite article and the demonstrative illustrated in (27a), the determiners on the main percent DP can also be the indefinite article with a meaning of approximation we already saw (28), but an article must always be present.20 In this case also the determiner inside the inner PP in addition to the definite determiner illustrated in (27a) has the possibility of being absent and only the bare preposition remains (di).

- (28)

- {un

- {about

- /

- /

- *∅}

- ∅}

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- {di

- {of

- /

- /

- degli

- of the

- /

- /

- di

- of

- quegli}

- those}

- studenti

- students

Interestingly, between the determiners choice on the main DP and on the inner noun inside the PP there is a relation subject to restrictions. When the whole percent is definite or demonstrative, the inner NP must necessarily be definite (29a), or an indefinite modified by a relative clause (29b), for the same reasons we saw for fractions ((25) and (26)).

- (29)

- a.

- {il

- {the

- /

- /

- quel}

- that}

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- {*di

- {of

- /

- /

- degli}

- of the}

- studenti

- students

- b.

- {il

- {the

- /

- /

- quel}

- that}

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- studenti

- students

- *(che

- (that

- hanno

- have

- superato

- passed

- l’esame)

- the exam)

There is one exception to the restriction on the main DP and the inner noun determiners just identified. Existential sentences (30a) and sentences with containment predicates (30b) involving percent DPs with a mass inner noun (zucchero) allow the outer determiner to be definite and the mass inner noun to be indefinite. This is not the case for fractions (30c) and (30d), where the outer determiner (i ‘thePL’) must be dropped.

- (30)

- a.

- In

- in

- questa

- this

- marmellata

- jam

- c’è

- there is

- il

- the

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- zucchero.

- sugar

- ‘Of all the ingredients in this jam ten percent is sugar.’

- b.

- Questa

- this

- marmellata

- jam

- contiene

- contains

- il

- the

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- zucchero.

- sugar

- ‘Of all the ingredients contained in this jam ten percent is sugar.’

- c.

- In

- in

- questa

- this

- marmellata

- jam

- ci

- there

- sono

- are

- (*i)

- (thePL)

- due

- two

- quinti

- fifths

- di

- of

- zucchero.

- sugar

- ‘Of all the ingredients in this jam two fifths are sugar.’

- d.

- Questa

- this

- marmellata

- jam

- contiene

- contains

- (*i)

- (thePL)

- due

- two

- quinti

- fifths

- di

- of

- zucchero.

- sugar

- ‘Of all the ingredients contained in this jam two fifths are sugar.’

Italian percentages always take singular number and masculine gender, even when the inner noun is feminine (31).

- (31)

- {il

- {theM.SG

- /

- /

- *i

- theM.PL

- /

- /

- *le

- theF.PL

- /

- /

- *la}

- theF.SG}

- due

- two

- percento

- percent

- delle

- of the

- donne

- womenF.PL

In singular percent DPs, also in the case of a singular numeral (un percento ‘one percent’), a definite or an indefinite article beside the numeral must be present (un ‘a’) (32). This requirement contrasts with what we saw for fraction DPs, where in the same context an indefinite article cannot be present (23a).

- (32)

- {un

- {about

- /

- /

- *∅}

- ∅}

- un

- one

- percento

- percent

- {di

- {of

- /

- /

- degli

- of the

- /

- /

- di

- of

- quegli}

- those}

- studenti

- students

Finally, to reinforce the requirement of a (singular) determiner in percentages, in (33) we see that a plural outer determiner (due ‘two’), although not perfect and limited to peculiar contexts where the entirety is reached, is better than no determiner at all (Falco & Zamparelli 2019: ex.66).21

- (33)

- {?Due

- {two

- /

- /

- *∅}

- ∅}

- cinquanta

- fifty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- un

- a

- salario

- salary

- fanno

- make up

- un

- a

- salario

- salary

- intero.

- whole

- ‘Two fifty percents of a salary make up a whole salary.’

To conclude the section we briefly summarise the differences between fraction and percent DPs. The first difference is at the lexical level: fractions are nouns whereas percento is an adverbial locution. This leads to the difference described at the morphological level: fractions are morphologically productive whereas percento is not. At the syntactic level, while fraction DPs can appear without a determiner, or with a singular or plural determiner, percent DPs always require the presence of a singular definite or indefinite determiner. This requirement is also due to the adverbial, non nominal, nature of percento, which needs an overt determiner to form a full-blown argumental DP phrase in Italian.

3 The DP and (non-)conservative interpretations

Having introduced the internal structure of Italian PM DPs §2, we are now ready to describe their interpretation focusing on how the structural possibilities at the DP level determine a clear distinction between conservative and non-conservative construals. At this level the fundamental morphological marker is the indefiniteness of the inner determiner, which in turn is constrained by the outer determiner (§§3.1). A second factor affecting (non-)conservativity at the DP level is the possibility to get multiple non-conservative interpretations when a modifier occurs in the PM DP. The study of this factor sheds light on the role played by contrastive and new information focus in Italian (§§3.2).

Crucially, in order for the conservative vs. non-conservative interpretations to emerge we need to zoom out of the DP internal level, which has been the focus of the description so far, to the clausal level including a predicate. When the clause is considered, two further morpho-syntactic markers come into play, namely the position of the PM DP with respect to the verb and the verb agreement pattern. Nevertheless, for the sake of clarity of presentation, in this section we abstract away from these factors until §4, and focus here on how the two construals are shaped by the determiners choice. For this reason, in this section the PM DPs are placed in the object position of the clause they belong to, since pre-V subject positions generally block non-conservative interpretations, and post-V subjects trigger verb agreement, which will be discussed later (§§4.2).

Furthermore, we need to make a preliminary remark on the lexical choices in the examples. Certain inner nouns get more easily contrasted with another set than others, since the properties they denote are decisively contrastive. These nouns include minorities, gender, sexual orientations, nationalities, social classes among others. For example, the set of black people easily evokes its complement set of non-black people or the set of women evokes its complement set of people who are not women, while the same cannot be said for a stage level property such as drunk or sleepy, which denote impermanent and nuanced properties (34).22 Since this dimension seems tied to the lexical semantics and social aspects of language meaning, we will put aside the specific mechanisms at play here, assuming that they are not grammatical in nature.

- (34)

- Semantic generalisation 1: In order to get a non-conservative interpretation the lexical semantics of the inner noun must evoke its complement set.

3.1 (In-)definiteness of the inner noun

In this subsection we describe how the conservative vs. non-conservative interpretation are shaped by the inner and outer determiners patterns in PM DPs.

If the whole PM DP has a definite determiner, then its inner noun must include a definite determiner as well or an indefinite determiner modified by a relative clause for both fraction DPs (§§2.2) and percent DPs (§§2.3); the difference between the two DPs is that the main determiner is obligatory in the case of percentages, but optional in the case of fractions. If we insert this type of measure DP in a clause with a predicate we can evaluate how it affects the interpretation. In this configuration, with definite determiners, the interpretation of the PM phrase is obligatorily conservative, as shown for percent DPs in (35a) and for fraction DPs in (35b).

- (35)

- a.

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- il

- the

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- {dei

- {of the

- /

- /

- *di}

- *of}

- non vaccinati.

- unvaccinated

- ‘They hired thirty percent of the unvaccinated.’

- b.

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- i

- the

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- {dei

- {of the

- /

- /

- *di}

- *of}

- non vaccinati.

- unvaccinated

- ‘They hired two thirds of the unvaccinated.’

When the head of the whole percent DP is an indefinite determiner, the inner noun can either be introduced by a definite determiner, as in (36a), or no (overt) determiner, as in (36b). In the former case, the interpretation is again conservative, just like (35a), while in the latter case, a non-conservative reading is forced.

- (36)

- a.

- Conservative, definite inner noun

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- dei

- of the

- non vaccinati.

- unvaccinated

- ‘They hired about thirty percent of the unvaccinated.’

- b.

- Non-conservative, indefinite inner noun

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- non vaccinati.

- unvaccinated

- ‘About thirty percent of the people they hired were unvaccinated.’

The same pattern is found with fraction DPs. The inner determiner can be definite, as in (37a), or an (overt) inner determiner can be absent, as in (37b). In the former case, the interpretation is again conservative, just like (35b), while in the latter case, the non-conservative reading comes about.

- (37)

- a.

- Conservative, definite inner noun

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- dei

- of the

- non vaccinati.

- unvaccinated

- ‘They hired (about) two thirds of the unvaccinated.’

- b.

- Non-conservative, indefinite inner noun

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- (un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- non vaccinati.

- unvaccinated

- ‘About two thirds of the people they hired were unvaccinated.’

Furthermore, the relevance of the inner noun indefiniteness for non-conservative proportional readings is further supported by the fact that the actual Italian word proporzione (‘proportion’) requires an indefinite inner noun (38a) and produces a much degraded outcome when it combines with a definite inner noun (38b).23

- (38)

- a.

- Che

- what

- proporzione

- proportion

- di

- of

- donne

- women

- hanno

- they have

- assunto?

- hired?

- ‘What proportion of women did they hire?’

- b.

- ?*Che

- what

- proporzione

- proportion

- delle

- of the

- donne

- women

- hanno

- they have

- assunto?

- hired?

- ‘What proportion of the women did they hire?’

To summarise, in order to get a non-conservative interpretation the proportional measure DP must contain an indefinite inner noun and this in turn requires in the default cases that the outer determiner is indefinite or absent, the latter is possible only in the case of fractions. However, there is an exception to the indefiniteness requirement for the outer determiner, namely a context where it is actually definite and the inner determiner is nevertheless indefinite. The generalisation on inner determiners and non-conservative construals remains valid also for this exceptional outer determiner pattern: as long as the inner determiner is absent the non-conservative reading arises.

The exception was illustrated in (30a) and repeated in (39a). Existential sentences involving percent structures with a mass inner noun (zucchero) allow the main DP to be definite and the mass inner noun to be indefinite (39a). As shown by the translation, the configuration produces a non-conservative interpretation. The parallel construction with a fraction introduced in (30c) and repeated in (39b) does not constitute an exception to the DP determiners generalisation, in fact when the inner noun is indefinite the main DP determiner must be dropped or must be an indefinite, just like in (37b).

- (39)

- a.

- In

- in

- questa

- this

- marmellata

- jam

- c’è

- there is

- il

- the

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- zucchero.

- sugar

- ‘Of all the ingredients in this jam ten percent is sugar.’

- b.

- In

- in

- questa

- this

- marmellata

- jam

- ci

- there

- sono

- are

- (*i

- (thePL

- /

- /

- un)

- a)

- due

- two

- quinti

- fifths

- di

- of

- zucchero.

- sugar

- ‘Of all the ingredients in this jam (about) two fifths are sugar.’

Note that these exceptions cannot be analysed as examples where the inner noun gets a kind/generic interpretation, as in that case we expect it to behave as a definite of semantic type <e> and give rise to a conservative construal (40) (see footnote 7).

- (40)

- Il

- the

- novanta

- ninety

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- italiani

- Italians

- si

- self

- sono

- are

- vaccinati. Conservative

- vaccinated

- ‘Ninety percent of the Italians got vaccinated.’

Modulo this exception which we leave for further research, we reach the following two descriptive morpho-syntactic generalisations.24

- (41)

- Morpho-syntactic generalisation 1: In order to get a non-conservative interpretation the PM DP must contain an indefinite inner noun.

- (42)

- Morpho-syntactic generalisation 2: In order to get a non-conservative interpretation the outer determiner of the PM DP must be indefinite.

3.2 Adjectives and contrastive focus

Another factor affecting (non-)conservativity at the DP level emerges when we consider DPs with modifiers, namely the presence of multiple non-conservative construals. Pasternak & Sauerland (2022: ex.82, reported in (43)), note this phenomenon for German and claim that the two different interpretations, shown in the free translations, actually correspond to different accent patterns marking a particular contrastive focus structure that deviates from the default accent pattern. The account of non-conservativity proposed by S&co crucially builds on this observation and on the analysis of contrastive focalisation (Rooth 1985).

- (43)

- a.

- Dreißig

- thirty

- Prozent

- percent

- [westfälische

- [WestphalianNOM

- Studierende]FOC

- studentsNOM]FOC

- arbeiten

- work

- hier.

- here

- ‘Thirty percent of the workers here are Westphalian students.’

- b.

- Dreißig

- thirty

- Prozent

- percent

- [westfälische]FOC

- [WestphalianNOM]FOC

- Studierende

- studentsNOM

- arbeiten

- work

- hier.

- here

- ‘Thirty percent of the student workers here are Westphalian.’

In Italian, contrary to German, the marking of the complex DP part which is contrasted can be obtained in-situ only through an explicit preceding question or through an explicit continuation (called tag), while a peculiar accent pattern is not sufficient (44).25

- (44)

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- [virologi

- [virologists

- italiani],

- Italian],

- non

- not

- infermieri

- nurses

- russi.

- russian

- ‘About ten percent of the professionals they hired were Italian virologists.’

Rizzi (1997) observes that focalization (fronting of a focus) is available for contrastive focus in Italian, and notes that there is another kind of focus which is not fronted (left in situ, and indicated by stress) and which may or may not be contrastive. Unfortunately, we cannot use Italian focus fronting to test the role of focus with respect to conservativity because the fronting itself or the obligatory insertion of ne when an of-phrase is fronted reinstate a conservative interpretation as illustrated by the free translation of (45).26

- (45)

- [Di

- of

- virologi

- virologists

- italiani]FOC

- Italian

- ne

- ones

- hanno

- they have

- assunti

- hired

- un

- a

- dieci

- ten

- percento,

- percent,

- (non

- (not

- di

- of

- infermieri

- nurses

- russi).

- Russian)

- ‘They hired about ten percent of the Italian virologists.’

Non-conservative measure DPs with an indefinite inner noun and an adjective show three different interpretations depending on the continuation tag. It can contrast either the entire inner noun (46a), or solely the adjective (46b), or solely the noun without the adjective (46c).

- (46)

- a.

- {Un

- {a

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- /

- /

- (Un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi}

- thirds}

- di

- of

- [virologi

- [virologists

- italiani]FOC

- Italian]FOC

- b.

- {Un

- {a

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- /

- /

- (Un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi}

- thirds}

- di

- of

- [virologists

- [virologists

- [italiani]FOC]

- [Italian]FOC]

- c.

- {Un

- {a

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- /

- /

- (Un)

- (a)

- due

- two

- terzi}

- thirds}

- di

- of

- [[virologi]FOC

- [[virologists]FOC

- italiani]

- Italian]

In the paradigm presented in §§3.1 we were dealing with two sets, one evoked by the inner noun inside the PM DPs and one evoked by the predicate of the clause, these two sets lead to a single non-conservative interpretation. Instead, in the paradigm we are looking at in this subsection, four sets are involved. We have the set evoked by the predicate of the clause, and three sets evoked by the modified inner noun: the set denoted by the entire inner noun including the adjective, the set denoted by the adjective alone and the set denoted by the inner noun alone. Each of these sets can give rise to a different non-conservative interpretation and be interpreted as the predicate of the PM instead of its restriction.

If we insert the three percentage DPs introduced in (46) as objects of a clause, we obtain the three interpretations in the free translations in (47). They are all non-conservative but the complement set at stake changes according to focus placement: so in the example in (47a) the set of Italian virologists is contrasted with the set of all the professionals who are not Italian virologists; in (47b) it is contrasted with the set of virologists who are of other nationalities; finally, in (47c) it is contrasted with the set of other Italian professionals.27

- (47)

- a.

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- [virologi

- [virologists

- italiani]FOC,

- Italian]FOC,

- non

- not

- infermieri

- nurses

- russi.

- russian

- ‘About ten percent of the professionals they hired were Italian virologists.’

- b.

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- [virologi

- [virologists

- [italiani]FOC],

- [Italian]FOC],

- non

- not

- virologi

- virologists

- russi.

- russian

- ‘About ten percent of the virologists they hired were Italian.’

- c.

- Hanno

- they have

- assunto

- hired

- un

- a

- dieci

- ten

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- [[virologi]FOC

- [[virologists]FOC

- italiani],

- Italian],

- non

- not

- infermieri

- nurses

- italiani.

- Italian

- ‘About ten percent of the Italian professionals they hired were virologists.’

The same pattern is found if we replace the three percent DPs with the three fraction DPs introduced in (46).

We conclude that contrastive focus is orthogonal to non-conservativity: it certainly interacts with it modifying the interpretations, but it is not necessary to obtain non-conservative construals in Italian. Indeed, all the examples seen in the previous sections do not involve contrastive focus since they lack an explicit antecedent question or subsequent tag.

The same pattern we reported here for inner nouns modified by adjectives applies also to more complex inner noun modifiers such a relative clauses. However, before approaching systematically the topic of focus with relative clause modifiers (§§5.2) we need to study verb agreement patterns and how they affect the (non-)conservative construal in main clauses §§4.2 and in complex sentences with subordinate clauses §§5.1.

4 The simple clause and (non-)conservative interpretations

We can now zoom out of the DP level and look at PM DPs in the context of the simple clause. Two factors affecting (non-)conservativity emerge at this level, the PM DP position, related to new information focus §§4.1, and the role of verb agreement §§4.2. Since we are now introducing clauses, we need to preliminary bring up the relevance of the individual-level vs. stage-level distinction of intransitive predicates for the conservative vs. non-conservative distinction (already mentioned in footnote 22). The terms individual-level and stage-level predicate were coined by Carlson (1977) (following the proposal of Milsark 1974) in order to make a distinction between predicates that apply respectively to an individual or entity for the entire duration or just to a stage of its existence. The individual vs. stage level distinction is fluid, but it is relevant for a number of grammatical phenomena. For example, individual-level predicates are not compatible with locative and temporal expressions, with existential constructions and with (unstressed) weak subjects; instead, stage-level predicates, occur with (overt or covert) locatives and temporal expressions, appear in existential constructions, and require weak subjects.

We propose to add to these phenomena also the conservative vs. non-conservative distinction.28 Sentences with individual level predicates and a PM DP with indefinite inner and outer determiners are quite marginal. Insofar as they can be accepted, they give rise to the conservative construal, irrespective of the PM DP form and the verb agreement pattern. In (48a) the predicate be intelligent denotes an individual level property: being intelligent is an inherent property which normally does not change and thus is incompatible with a locative and temporal restriction. Intuitively, individual level properties being inherent to the inner noun women have a strong tie to it and for this reason cannot be easily applied to the complement set of the inner noun, even if the structural requirements are respected. Furthermore, the individual-level predicate lacks a location argument (Kratzer 1995: p.136) which delimits the set of individuals who are intelligent. Instead, stage level predicates (be present in (48b)) could be easily applied to the complement set of the inner noun, thus facilitating the non-conservative interpretation when the structural requirements are respected. Furthermore, the stage level predicate does have a location argument (Kratzer 1995: p.136) enabling the definition of the set of individuals who are present, which acts as the restriction of the proportion in the non-conservative construal. Actually, sentences with intransitive verbs get a non-conservative construal when this location argument is overtly realised.

- (48)

- a.

- Individual level predicate, conservative

- ??È

- is

- intelligente

- intelligent

- un

- a

- sessanta

- sixty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- donne.

- women

- ‘Sixty percent of the women are intelligent.’

- b.

- Stage level predicate, non-conservative

- Qui

- here

- è

- is

- presente

- present

- un

- a

- sessanta

- sixty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- donne.

- women

- ‘Of all the people here sixty percent are women.’

Therefore, we can add the semantic generalisation in (49), to the ones we already reached in the previous sections.

- (49)

- Semantic generalisation 2: In order to get a non-conservative interpretation intransitive predicates must denote a stage level property.

Since this distinction belongs to the lexical semantics of the predicates, we do not discuss it further here. However, in order to study the role of verb agreement patterns in producing conservative and non-conservative construals, we have to avoid individual-level intransitive predicates.

4.1 Proportions position and new information focus

Contrary to contrastive focus (§§3.2), new information or wide focus is a crucial factor in Italian. In fact, non-conservative construals are not attested in Italian when the DP is in pre-verbal subject position, which has a givenness/topic nature (Chafe 1976). Contrary to Ahn & Sauerland (2017: ex.44), according to the pool of 6 native speakers, in Italian only post-V indefinite percentages and indefinite fractions with an indefinite inner noun get a non-conservative construal, while sentences with the same percent DPs placed in pre-V position are marginally acceptable with neutral intonation and get a conservative construal (50).

- (50)

- a.

- ?Un

- a

- sessanta

- sixty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- donne

- women

- ha

- has

- acquistato

- bought

- il

- the

- libro. Conservative

- book

- ‘About sixty percent of the women bought the book.’

- b.

- ?Un

- a

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- donne

- women

- ha

- has

- acquistato

- bought

- il

- the

- libro. Conservative

- book

- ‘About two thirds of the women bought the book.’

In this subsection we reached a semantic/pragmatic generalisation concerning new information focus (51), related to a syntactic difference in the word order in the sentence (52).

- (51)

- Semantic generalisation 3: In order to get a non conservative interpretation the PM DP must be in a new information position, as opposed to given information position.

- (52)

- Morpho-syntactic generalisation 3: In order to get a non-conservative interpretation the PM DP must be in a post-V position.

4.2 Proportions and verb agreement

Italian adjectives normally agree both in number and in gender with the preceding noun. Therefore, when adjectives occur within a complex DP, such as a measure phrase, they should agree with the adjacent name they modify. In the case of measure phrases this means that adjectives must agree with the inner noun as we saw throughout the paradigms in §§3.2. Instead, agreement of an individual level adjective with the measure DP head is ungrammatical, as illustrated by the sharp ungrammaticality of the examples in (53), involving an absolute measure, a percentage and a fraction respectively.29

- (53)

- a.

- *[un

- [about

- centinaio]

- a hundred]M.SG

- di

- of

- [donne

- [womenF.PL

- italiano]

- ItalianM.SG]

- b.

- *[un

- [about

- dieci

- ten

- percento]

- percent]M.SG

- di

- of

- [donne

- [womenF.PL

- italianoM.SG]

- ItalianM.SG]

- c.

- *[due

- [two

- terzi]

- thirds]M.PL

- di

- of

- [donne

- [womenF.PL

- italiani]

- ItalianM.PL]

Contrary to adjectives, in colloquial Italian verbs with complex subject DPs, such as PM DPs, can easily agree either with the entire DP or with the inner NP. In order to abstract away from verb agreement, so far we used mainly object DPs, which do not trigger agreement, and limited the examples with post-V subject PM DPs, which do trigger agreement on the preceding verb.

The agreement patterns are introduced with a passive construction built with a participle presenting both number and gender agreement in Italian, taking care to put the DP in post-V position. This possibility is attested in Italian as a pro-drop language allowing the subject of passive and unaccusative verbs to remain in post-verbal position, where it is base-generated. Therefore, these verbs permit to explore the full spectrum of the agreement paradigm with the appropriate measure DP choice. Of course, it is not necessary to see both number and gender agreement: any mismatch is sufficient to discriminate which is the agreement trigger.

In the following paradigms we illustrate the space of possibilities allowed by the agreements patterns with passive verbs with post-verbal PM DPs, without describing how these affect the conservative vs. non-conservative interpretations for of the clauses at this introductory stage. For this reason, these examples are glossed, but the free translation is not provided. In percent DPs which are always masculine singular in Italian but can feature a countable plural inner noun, it is possible to observe a mismatch in both number and gender using a plural feminine inner noun ((54a) vs. (54b), where pc stands for percento ‘percent’).30 In fraction DPs it is possible to obtain the same agreement pattern as in percentages when the fraction is singular and denotes one part and the inner noun is plural (un terzo di/delle donne ‘a third of/of the women’). Instead, when the fraction is plural a number and gender agreement contrast can be obtained with a singular mass feminine inner noun ((54c) vs. (54d)).31

- (54)

- a.

- [Sono

- [are

- state

- been

- assunte]

- hired]F.PL

- [[un

- [[a

- dieci

- ten

- pc]

- pc]M.SG

- {??di/delle}

- {of/of the}

- donne].

- womenF.PL]M.SG

- b.

- [È

- [is

- stato

- been

- assunto]

- hired]M.SG

- [[un

- [a

- dieci

- ten

- pc]

- pc]M.SG

- {di/delle}

- {of/of the}

- donne].

- womenF.PL]M.SG

- c.

- [È

- [is

- stata

- been

- venduta]

- sold]F.SG

- [[due

- [[two

- terzi]

- thirds]M.PL

- {??di/della}

- {of/of the}

- birra].

- beerF.SG]M.PL

- d.

- [Sono

- [are

- stati

- been

- venduti]

- sold]M.PL

- [due

- [[two

- terzi

- thirds]M.PL

- {di/della}

- {of/of the}

- birra].

- beerF.SG]M.PL

There are quite a few psycholinguistic studies on agreement processing looking at verb agreement with complex subject DPs (proximity concord, for Italian starting from Vigliocco et al. 1995). These studies generally consider all the instances of agreement with the inner noun processing errors. The majority of the examples these works discuss involve, indeed, processing errors, however, we maintain that in the structures we are studying here, namely PM DPs, there is an actual grammatical optionality with two different underlying structures (and corollary interpretation) depending on the verb agreement pattern (Manzini 2019: §1). The interpretive import of this variation can be fully appreciated by looking at how the conservative vs. non-conservative interpretations are affected by the two agreement options.

We can now test number (55) and gender (56) agreement in isolation with the appropriate inner noun choice and study how they shape the conservative and non-conservative interpretations. When a conservative PM DP (with a definite inner D) is the subject agreement is irrelevant for conservativity, since both number agreement patterns lead to conservative construals due to the presence of the definite inner D (55a)–(56a) (of the blacks, of the beer see (41)). If a non-conservative PM DP (with an indefinite inner noun and outer D) is the subject, agreement becomes relevant for the conservative vs. non-conservative distinction: agreement with the outer D ((55b)–(56b)) actuates a non-conservative construal, while agreement with the inner noun, to the extent it is acceptable, triggers a conservative construal ((55c)–(56c)): the indefinite inner noun behaves like a definite with respect to conservativity and (55c)–(56c) are parallel to (55a)–(56a).32

- (55)

- a.

- {È

- {[is

- stato

- been

- assunto

- hired]M.SG

- /

- /

- Sono

- [are

- stati

- been

- assunti}

- hired]M.PL}

- {il

- {the

- /

- /

- un}

- a}

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- dei

- of the

- neri.

- blackM.PL]M.SG

- ‘(About) thirty percent of the black people were hired.’

- b.

- È

- [is

- stato

- been

- assunto

- hired]M.SG

- un

- [a

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- neri.

- blackM.PL]M.SG.

- ‘About thirty percent of the people hired are black people.’

- c.

- ??Sono

- [are

- stati

- been

- assunti

- hired]M.PL

- un

- [a

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- neri.

- blackM.PL]M.SG

- ‘About thirty percent of the black people were hired.’

- (56)

- a.

- {È

- {[is

- stata

- been

- venduta

- sold]F.SG

- /

- /

- È

- [is

- stato

- been

- venduto}

- consumed]M.SG}

- {il

- [{the

- /

- /

- un}

- a}

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- della

- of the

- birra

- [beer

- tedesca.

- German]F.SG]M.SG

- ‘(About) thirty percent of the German beer was sold.’

- b.

- È

- [is

- stato

- been

- venduto

- sold]M.SG

- un

- [a

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- birra

- [beer

- tedesca.

- German]F.SG]M.SG

- ‘About thirty percent of all the beer sold was German beer.’

- c.

- ??È

- [is

- stata

- been

- venduta

- sold]F.SG

- un

- [a

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- birra

- [beer

- tedesca.

- German]F.SG]M.SG

- ‘About thirty percent of the German beer was sold.’

The same pattern we saw for percentages applies to fraction DPs (54c)–(54d), but we omit the paradigms for the sake of brevity.

In conclusion, in this section we have reached the morpho-syntactic generalisation in (57):

- (57)

- Morpho-syntactic generalisation 4: In order to get a non-conservative interpretation the main verb cannot agree with the inner noun, otherwise it behaves as a definite.

5 Complex sentences and (non-)conservative interpretations

We can now zoom out of the simple clause to look at complex sentences including a subordinate relative clause attached to the PM DP. These sentences pose two challenges to the descriptive generalisations reached so far. Firstly, when a PM DP is the head of a relative clause its inner determiner can be indefinite while the outer determiner must be definite. Secondly, the generalisation concerning the ban on a non-conservative interpretation for pre-V PM DPs (52) does not hold in subordinate clauses.

When a relative clause is attached to a PM DP with an indefinite inner noun and verb agreement with the outer D (and incompatible with the inner noun), the outer D must be definite so that the relative clause can attach to the DP. This requirement applies in the same way to percentages (58a) and to fractions (58b).33 As shown by the translations, both these constructions give rise to a non-conservative construal confined within the relative clause itself.34

- (58)

- a.

- La

- the

- ditta

- company

- ha

- has

- licenziato

- fired

- il

- [the

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- donne

- womenPL]SG

- che

- that

- ha

- hasSG

- avuto

- had

- il

- the

- Covid.

- Covid

- ‘Thirty percent of the employees who had Covid are women and the company fired those women.’

- b.

- La

- the

- ditta

- company

- ha

- has

- licenziato

- fired

- i

- [the

- due

- two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- personale

- [staff

- femminile

- female]SG]PL

- che

- that

- hanno

- havePL

- avuto

- had

- il

- the

- Covid.

- Covid

- ‘Two thirds of the staff who had Covid are female staff and the company fired that female staff.’

These same sentences are strongly degraded when the definite article is omitted and the verb agreement patterns in the relative clause are incompatible with the inner noun (but they become marginally acceptable if the verb in the relative clause agrees with the inner noun see §§5.1).

- (59)

- a.

- *?La

- the

- ditta

- company

- ha

- has

- licenziato

- hired

- un

- a

- trenta

- thirty

- percento

- percent

- di

- of

- donne

- women

- che

- that

- ha

- hasSG

- avuto

- had

- il

- the

- Covid.

- Covid

- b.

- *?La

- The

- ditta

- company

- ha

- has

- licenziato

- fired

- due

- [two

- terzi

- thirds

- di

- of

- personale

- [staff

- femminile

- female]SG]PL

- che

- that

- hanno

- havePL

- avuto

- had

- il

- the

- Covid.

- Covid.

In conclusion, the Morpho-syntactic generalisation 2 (42) must be modified to accomodate the facts concerning subordinate clauses (60).

- (60)

- Morpho-syntactic generalisation 2 revised: In order to get a non-conservative interpretation the outer determiner of the PM DP must be indefinite, unless it is the head of a relative clause.