1 Introduction

In this paper we focus on cases of root allomorphy in Slovenian in which two allomorphs of the root can be observed (one in the non-finite and one the finite forms of the verb) and these two allomorphs cannot be derived from the same underlying representation by general phonological rules:

- (1)

- a.

- ˈʒ-e-ti, ˈʒanj-e-mo ‘to reap, we reap’1

- b.

- ˈwz-e-ti, ˈwzam-e-mo ‘to take, we take’

- c.

- ˈp-e-ti, ˈpɔj-e-mo ‘to sing, we sing’

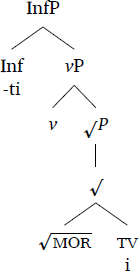

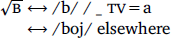

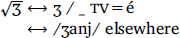

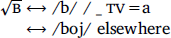

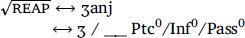

This data was previously discussed in Božič (2016; 2019), who treats such cases as examples of non-local root allomorphy. Working within Distributed Morphology (Halle & Marantz 1993; 1994), in which vocabulary insertion is typically taken to obey locality (Embick 2010), and assuming that roots are subject to late insertion (see, e.g., Harley (2014)), Božič proposes that cases such as the ones in (1) are subject to contextual application of vocabulary insertion. The root allomorph found in finite forms is taken to be the elsewhere item, while the allomorph found in non-finite forms is triggered by the Ptc0/Inf0/Pass0 heads, (2). Crucially, this triggering happens across the theme vowel (-e- in all examples in (1)). Božič’ analysis of cases under discussion as non-local allomorphy therefore hinges on the presence of an overt theme vowel in all forms, its position (that is, the structure of the Slovenian verb), and the proposed trigger.

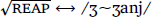

In what follows, we will reevaluate the data (using a larger set of verbs) and reconsider the structure of the verb in Slovenian (focusing primarily on the position of the theme vowel). As a result, we will show that root allomorphy in Slovenian occurs only in a very limited number of theme-vowel classes, making the inventory of theme-vowel classes crucial for the correct analysis. Furthermore, while the analysis in Božič (2016) assumes full suppletion, i.e. two Vocabulary Items with independent exponents, (2), we argue for an analysis in terms of phonologically conditioned allomorph selection (see Nevins 2011 for an overview) whereby a single Vocabulary Item with a complex phonological representation gets inserted and then phonological constraints select the final shape of the exponent (Kager 2008), (3).

- (2)

- Vocabulary Item for ʒeti~ʒanjemo ‘to reap ~we reap’ proposed in Božič (2016: 5)

- (3)

- The proposed Vocabulary Item for ʒeti~ʒanjemo ‘to reap~we reap’

We assume that the output of vocabulary insertion is passed on to phonology, that we formalize in terms of Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky 1993). Specifically, we are using an Optimality Theory (OT) grammar sensitive to phasal information (for comparable approaches, see, e.g., Gribanova 2015; Sande & Jenks & Inkelas 2020). This means that we are ultimately proposing an analysis in which the structural representation (in terms of Distributed Morphology (DM)) feeds into the OT evaluation and therefore build a proposal in which the two frameworks work hand in hand (for further proposals that combine the two approaches see, for example, Trommer (2001); Wolf (2008)).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we give an overview of the verb in Slovenian. We discuss the analysis of the structure of the verb within DM in 2.1. In 2.2 we turn to stress in Slovenian verbs, whereas 2.3 focuses on the inventory of theme vowels. In 2.4 we discuss the theme-vowel classes that are involved in cases of root allomorphy, showing that verbs with root allomorphy often display class indeterminacy due to the partial overlap of the theme-vowel exponents (e.g., the theme vowel a/e partially overlaps with a/je). In Section 3 we give a detailed overview of roots displaying unpredictable root allomorphy in Slovenian and the different parsings available for each verb. We argue for one approach for resolving theme-vowel class indeterminacy in Section 4. Section 5 brings the analysis of root allomorph selection couched in Optimality Theory. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Slovenian verb – the assumptions

As indicated in Section 1, the paper focuses on root allomorphy in Slovenian verbs, a phenomenon in which a crucial role is played by the interaction between the root and the theme vowel. This section addresses four issues that will be central to our analysis: (i) the structure of the (simplex) verb in Slovenian, (ii) verbal stress in Slovenian, (iii) the inventory of theme vowels and (iv) cases of theme-vowel class indeterminacy.

2.1 Structure of the verb

In Slovenian, as in many other languages, the theme vowel is one of the basic parts of the verb, appearing between the root and the inflectional ending, as -a- in (4).

- (4)

- koˈɾak

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- koˈɾak

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to march, we march’

It is less straightforward to determine what the role and the structural position of the theme vowel is. Limiting the discussion to Distributed Morphology (Halle & Marantz 1993; 1994), theme vowels are often taken to be ornamental, i.e. relevant for the morphological well-formedness, but with no influence for syntax, as proposed for Latin by Embick (2010: 75). Theme vowels are further assumed to get inserted post-syntactically to mark a verbalized root (and potentially every other functional head, see Oltra-Massuet (1999) for the original proposal and Oltra-Massuet (2020) for an overview of the issue). However, many recent works on Slavic, e.g., Jabłońska (2007) on Polish, Medová & Wiland (2019) for Czech and Polish, Dyachkov (2021) for Russian and Milosavljević & Arsenijević (2022) in this issue for BCS, show that some items indeed have no syntactic or semantic contribution, while several items traditionally taken to be theme vowels can have syntactic input. This indicates that (at least for Slavic) sets of assumed theme vowels need to be reconsidered in order to tease apart ‘proper’ theme vowels from affixes with vocalic exponents that appear between the root and the inflectional ending. While the issue goes beyond the scope of this paper, we return to some aspects of it in 2.4.

Turning to Slovenian, we first consider two existing proposals for the position of the theme vowel that have emerged within Distributed Morphology. Marvin (2002: 95) argues that the relation between the theme vowel and the root is extremely local, assuming that the theme vowel adjoins to the root, forming a root phrase for reasons of morphological well-formedness. It is then the whole root phrase that gets verbalized. This is shown for moɾiti ‘to murder’ in (5), taken from Marvin (2002: 95).

- (5)

This account poses a conceptual problem, as it makes roots in verbs different from all other roots. Specifically, the account predicts that the categorial affiliation of verbal roots (i.e., roots that eventually get verbalized) will be encoded already on the root. This goes against the assumption that roots do not carry categorial information (see Embick & Marantz (2008) for a discussion of the categorization assumption). It is also unclear if each “verbal root” would have to be stored more than once if it appears under categorizers other than v (e.g., if nouns like koɾak ‘step.n’ would include a different root than the verb koɾakati in (4)).

On the other hand, Božič (2015) argues that the root is verbalized with a phonologically empty verb head, while the theme vowels are exponents of the Aspect head, as indicated in example (6) (a representation for a finite verb form) taken from Božič (2016: 140).

- (6)

The proposal in Božič (2015) needs to be commented on more extensively, since this proposal was adopted to argue for a non-local analysis of root allomorphy in Slovenian in Božič (2016).

Working on the verbal domain in Novo Mesto Slovenian, Božič (2015) proposes that theme vowels are in Asp0 based on the following reasoning: secondary imperfective suffixes (in this variety uυa/uje and eυa/eυa) cannot co-occur with semelfactive suffixes (ni/ne) and semelfactives cannot co-occur with theme vowels, so this suggests that theme vowels and the two types of suffixes occupy the the same projection. As noted in Božič (2015), a similar proposal has also been made for Russian in Gribanova (2015). However, similarly to the analysis of secondary imperfectives that we will propose in Section 2.3, Gribanova (2015) decomposes Russian secondary imperfective suffixes and proposes that theme vowels are sisters of Asp0 (following Oltra-Massuet (1999), these are post-syntactically associated with a functional head). And while Božič (2015) mentions such a decomposition as a possible alternative account, only the account with theme vowels, semelfactives and secondary imperfectivizers as exponents of the same head is implemented in his analysis of root allomorphy given in Božič (2016) (explicitly based on Božič (2015)).

There are several obstacles to implementing Božič (2015) in our analysis. Firstly, it is not necessarily the case that aspectual suffixes are in complementary distribution with theme vowels, since secondary imperfectivizers can arguably be reanalyzed as combinations of suffixes and theme vowels. Secondly, while it does hold that the majority of simplex verbs in Slovenian are imperfective (e.g., iˈɡɾati ‘to play.ipfv’ in the a/a class or ˈmisliti ‘to think.ipfv’ for the i/i class), there is no strict relation between the choice of the theme vowel and perfectivity. Prefixless perfective verbs belonging to the same theme-vowel classes also exist, e.g., konˈtʃati ‘to end/finish.pfv’ (a/a), doˈb-i-ti ‘to get.pfv’ (i/i). Following the proposal in Božič (2015), this would mean that the same head with different featural specification (and, consequently, interpretation) is realized by the same exponent.2 Note also that prefixation, which typically changes the aspect of the simplex verb in Slovenian from imperfective to perfective, never changes the theme vowel (compare example (4) to (7), and examples in (ia) and (ib) in footnote 10.).

- (7)

- ot-

- from-

- koˈɾak

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ot-

- from-

- koˈɾak

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to march away.pfv, we march away.pfv’

We therefore depart from Marvin (2002) and Božič (2015), and follow Quaglia et al. (submitted), who propose an analysis of the verbal domain in Slavic that avoids the issues that the two mentioned proposals face.

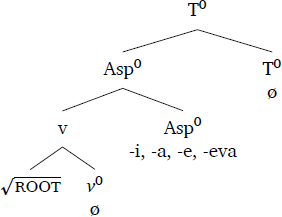

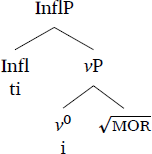

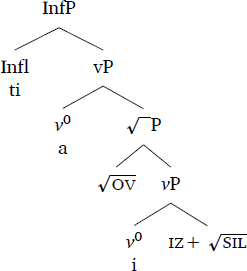

The analysis in Quaglia et al. (submitted) builds on observed parallels between roots and derivational verbal suffixes (in their paper they only discuss secondary imperfective suffixes), where they crucially show that both get verbalized by theme vowels and can display allomorphy (we return to this in Section 2.4). They assume an approach in which derivational affixes (such as secondary imperfective suffixes) are roots (Lowenstamm 2014). We will not give a detailed overview of Lowenstamm (2014) here, suffice it to say that he proposes that derivational affixes are transitive (or bound) roots, which take as their complement a phrase or a root and need to be categorized, just like all other roots. This effectively means that what is traditionally viewed as verbalizing, nominalizing etc. affixes are actually a combination of a transitive root and a categorial head (see Fábregas (2017) for the application of this approach to the Spanish verb, Simonović & Mišmaš (2022) and Simonović (accepted) for Slovenian). As for theme vowels in Slavic verbs, Quaglia et al. (submitted) propose that that they are the spellout of the verbalizing head v0 (see also Fábregas (2017) for Spanish) and argue that theme vowels (re)verbalize each (category-free) √P into a verbal projection. Example (8) shows the structure of the simplex verb moˈɾ-i-ti ‘to murder’.

- (8)

In order to show how the model in Quaglia et al. (submitted) deals with the interaction between theme vowels and secondary imperfective affixes, we turn to the aspectual triplet ˈsil-i-ti ‘to force.ipfv’ – is-ˈsil-i-ti ‘to extort.pfv’ – is-sil-j-eˈυ-ati ‘to extort.ipfv’. The “simplex” verb ˈsil-i-ti has the same structure as (8). The perfective verb has an additional prefix, which originates below the root  . Since this is not crucial to our analysis, we use the shortcut

. Since this is not crucial to our analysis, we use the shortcut  (but see Quaglia et al. (submitted) for a detailed analysis). As for the secondary imperfective is-sil-j-eˈυ-ati ‘to enforce.ipfv’, it has the structure in (9).

(but see Quaglia et al. (submitted) for a detailed analysis). As for the secondary imperfective is-sil-j-eˈυ-ati ‘to enforce.ipfv’, it has the structure in (9).

- (9)

The underlying representation that gets spelled out to phonology is /iz+sil+i+oυ+a+ti/, which turns to [issiljeˈυati] by productive phonological rules.

Cases like this, where two theme vowels are phonologically realized, are straightforwardly accounted for by the analysis in Quaglia et al. (submitted), whereas they present a problem for approaches such as Gribanova (2015: 543–544), who takes theme vowels to be post-syntactically associated with Asp0. This latter view implies that there can only be a single theme vowel per verb form.

The structure in (9) also shows the observed parallelism between roots such as  and the secondary imperfective suffix. Both the suffix and the “lexical” root are in this approach taken to be verbalized roots (whereas the theme vowel is associated with v0).

and the secondary imperfective suffix. Both the suffix and the “lexical” root are in this approach taken to be verbalized roots (whereas the theme vowel is associated with v0).

Having completed the discussion of the structure of the verbal domain, we now turn verbal stress in Slovenian.

2.2 Stress in Slovenian verbs

Slovenian is a system with lexical stress where all vowels can carry stress (Toporišič 2004), though mid lax vowels have been shown to avoid stress (Becker & Jurgec 2020), as does schwa. Nouns are the most liberal class with respect to stress (in line with cross-linguistic tendencies observed in Smith (2011)). As the examples below show, nouns can have stress on any syllable:

- (10)

- ˈpamet-i ‘mind-gen’

- (11)

- tʃeˈljust-i ‘jaw-gen’

- (12)

- oblaˈst-i ‘authority-gen’ (next to oˈblast-i)

Out of the three patterns illustrated in (10)–(12), the stem-final pattern in (11) is by far the most frequent and has been argued to be default, e.g., in Jurgec (2019), Becker & Jurgec (2020), Simonović & Mišmaš (2020) and Simonović (2020). For specific frequency counts across categories, see Becker & Jurgec (2020) and Simonović & Mišmaš (2020).

Verbal prosody is far more restricted than is the case in nouns. The stress patterns possible in a verbal form are essentially two: stress either falls on the theme vowel or on the syllable preceding it. The segmental content of the theme vowel is not sufficient to predict the stress pattern. This is illustrated below on three verbs from the i/i class.

- (13)

- Variable stress in i/i verbs3

inf pres.1pl Gloss ˈur-i-ti ˈur-i-mo ‘to drill’ doˈb-i-ti doˈb-i-mo ‘to get’ loˈm-i-ti ˈlom-i-mo ‘to break’

The only exceptions to the restriction on verbal stress (to two positions: theme vowel and the syllable preceding it) can be found in denominal verbs, such as the verb in (14), in which nominal stress is preserved. This specific verb is also the only exceptional one with respect to stress among the 3000 most common verbs in Slovenian. For further examples and a denominal analysis of the prosody of such verbs, see Simonović (accepted).

- (14)

- ˈpɾidig-a ‘a sermon’ → ˈpɾidig-a-ti ‘to preach’

Reviewing evidence that verbal stress is limited to two positions, Simonović (accepted) argues for a phasal-spellout analysis of stress assignment in the verbal domain (building on Marvin 2002), claiming that “verbal stress is controlled by the theme vowel”, but does not provide an account of how this is computed. In what follows, we present a proposal of verbal stress assignment in regular verbs.

In a nutshell, theme vowels are underlyingly either stressed or stressless. Every vP is spelled out with final stress (shown to be the default in Jurgec 2019, Simonović (2020), Simonović & Mišmaš (2020), Simonović (accepted)). The two-way surface distinction is a consequence of a selective incorporation of the theme vowel in the spellout of the vP. While stressed theme vowels are incorporated into the verbal phase, unstressed theme vowels are spelled out in the following phase.

Our proposal of the spellout mechanism is informed by the surface inventory of roots across theme-vowel classes. In the class of verbs without root allomorphy, there are two shapes of roots: some roots contain vowels (e.g., in (15)), while others are consonantal (e.g., (16)).

- (15)

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to work, we work’

- (16)

- ˈsp

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈsp

- √

- -i

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to sleep, we sleep’

As the examples in (15) and (16) show, both syllabic and consonantal roots are possible in the theme-vowel classes which have vocalic exponents of theme vowels. On the other hand, in the theme-vowel classes where the theme vowel can have a null exponent (∅/e and ∅/ne), there are only syllabic roots, i.e., there are verbs like that in (17), but no verbs like that in (18).

- (17)

- ˈpas

- √

- -∅

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈpas

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to pasture, we pasture’

- (18)

- *s -∅

- √-tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- s -e

- √-tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- unattested

The unattestedness of verbs like the one in (18) indicates that there is a minimality requirement on the spellout of the vP: there has to be a stress foot projected and for this, a vowel is necessary (see Guekguezian (2017) for a discussion of minimality requirements). In our OT analysis the constraint that enforces stress assignment on the vP phase is Culminativity, defined in (19). Since every vP is spelled out with a stress mark, Culminativity is undominated.

- (19)

- Culminativity

- Assign a violation mark for every candidate that does not have exactly one stress mark.

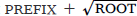

Now we can turn to the issue of stress position. We use ɡoljuˈf-a-ti ‘to cheat’ to exemplify forms with a stressed theme vowel and zaˈnim-a-ti ‘to interest’ to exemplify forms with stress on the syllable preceding the theme vowel. We follow Simonović (accepted) in the assumption that all verbal prosody depends on the prosodic specification of the theme vowel.4 The most basic contrast is that between stressed and unstressed theme vowels. It is straightforward that surface-stressed theme vowels correspond to lexically stressed theme vowels, e.g., in ɡoljuˈfati ‘to cheat’ that plausibly corresponds to /goljuf-á-ti/. However, it is not immediately clear why unstressed theme vowels all surface as prestressing, e.g., why /zanim-a-ti/ yields zaˈnimati ‘to interest’.

As previewed above, we argue that stressed theme vowels are incorporated into the cycle, whereas unstressed theme vowels are spelled out in the following cycle. The stress pattern in zaˈnim-a-ti is then a result of the default final stress assignment. On this account, the stress pattern in zaˈnim-a-ti is the normal case, where the complement is spelled out without the head, and the head gets spelled out in the following phase.

In the literature on phasal spellout, there is an ongoing debate on whether what gets spelled out is just the complement or it also includes the head (see, e.g., Sande & Jenks & Inkelas (2020) for a model arguing for the former, currently dominant view, and Bošković (2016) for the opposing view). In our model, the incorporation of the head into the spellout domain is available but dispreferred, so both the form with incorporation and without incorporation will be in the candidate set, but the constraint defined in (20) will assign a violation mark to all candidates with head incorporation.

- (20)

- *Incorporate

- Assign a violation mark to each candidate that includes the phase head into the spellout.

As mentioned above, every spellout of the vP has rightmost stress, indicating that Rightmost (a well established alignment constraint proposed already in Prince & Smolensky (1993)), defined in (21), will be in the top stratum together with Culminativity.5

- (21)

- Rightmost

- Assign a violation mark for every stress mark that is not at the right edge of the prosodic word.6

Incorporation takes place only when the theme vowel has lexical stress, as a way to avoid assigning epenthetic stress. In OT terms,*Incorporate gets violated when this violation helps to satisfy FaithStress, defined in (22) based on the constraint Prosodic-Faithfulness from Alderete (1999). This constitutes a ranking argument for placing FaithStress above *Incorporate.

- (22)

- FaithStress

- Assign a violation mark for every candidate that has different stress specifications in input segments and the corresponding output segments.

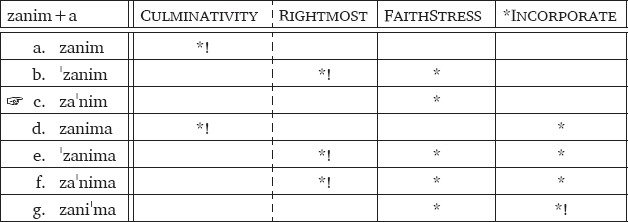

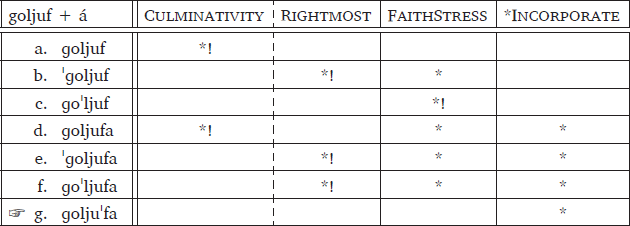

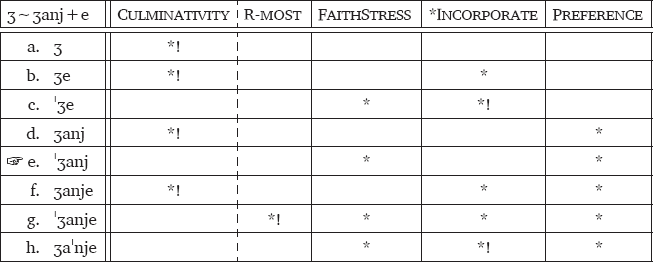

Now we can turn to evaluations by the established ranking, where Culminativity and Rightmost are in the topmost stratum followed by FaithStress » *Incorporate. The tableau in (23) shows stress assignment in cases with no stress on the theme vowel. Such words need to be assigned epenthetic stress in order to satisfy Culminativity and this stress needs to be final due to Rightmost. Since no lexical stress is available, FaithStress needs to be violated. Incorporating the head into the spellout domain does not help in any way, so *Incorporate blocks candidate g. This is how root-final stress is achieved.

- (23)

- Root + unstressed TV: zaˈnimati ‘interest’

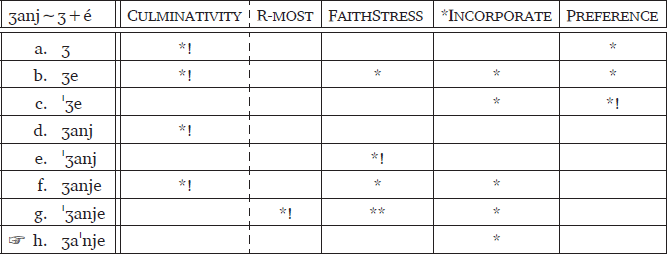

The tableau in (24) shows stress assignment in verbs with a stressed theme vowel. The key difference is that now there is underlying stress in the input and FaithStress can be satisfied by incorporating the head in the spellout domain, to the detriment of *Incorporate. This is how surface stressed theme vowels come about.7

- (24)

- Root + stressed TV: ɡoljuˈf-a-ti ‘cheat’

This concludes our analysis of stress assignment in regular verbs. We now turn to the issue of the inventory of theme-vowel classes.

2.3 Inventory of theme-vowel classes

In Slovenian, as in many other languages, theme vowels can be conceptualized as morphemes that define conjugation classes, see Oltra-Massuet (2020) for a recent overview. However, there is an important difference between Slovenian and Romance languages, which are often used to illustrate theme vowels, in that in Slovenian we cannot identify the theme-vowel class of the verb based on a single verbal form (such as the infinitive). Rather, at least two forms are necessary to identify the theme-vowel class: one finite and one non-finite form. This is illustrated in (25) and (26). While the infinitive of the verb in (25) appears analogous to that of the verb in (26), their present tense forms reveal different theme vowels (tv).

- (25)

- ˈkis

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈkis

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to acidify, we acidify’

- (26)

- ˈɾis

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈɾis

- √

- -je

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- [ˈri∫emo]

- ‘to draw, we draw’

While a model that derives both exponents of the theme vowel from a single underlying representation would be preferred, no such model can be plausibly proposed for modern Slovenian (see Simonović & Mišmaš (2022) for a detailed discussion). We therefore assume, together with recent descriptive works (e.g., Šekli 2010), that theme-vowel classes are identified by pairs of theme vowels: the one showing up in non-finite forms and the one showing up in finite forms.8 In this article, we therefore use the infinitive and the first person plural form of the present tense to illustrate verbs.

As discussed in 2.1, some items included in the theme-vowel inventory potentially have some syntactic or semantic contribution. Such items do not fit the definition of the theme vowel as a “a piece of morphology that carries no syntactic information, such as agreement or case, and makes no contribution to meaning” (Marvin 2002: 95). In fact, as noted in Svenonius (2004), exhaustive lists of theme-vowel classes for Slavic languages often include items with such contribution. One such “theme vowel” often included among theme-vowel classes in Slavic languages, is the inchoative -e-, which can be observed in the e/i class in Slovenian.

In order to establish the inventory of theme vowels in Slovenian, we have considered 3000 most common Slovenian verbs (with the exclusion of the irregular verbs ˈbiti ‘to be’, ˈiti ‘to go’ and iˈmeti ‘to have’).9 The inventory is given in Table 1, which includes the list of the classes, an example for each theme-vowel class and the information about the size of the class. The size refers to the number of verbs in the database that belong to each individual TV-class and not the number of different roots within a class. This means that some of the smaller classes in fact include only a small number of different roots (e.g., 4 different roots in the ∅/ne class).

Theme-vowel classes in Slovenian.

| Theme-vowel class | Example (infinitive, 3p.pl) | Size of the class |

| a/a | igˈɾ-a-ti, igˈɾ-a-mo ‘to play’ | 34.8% (1044) |

| i/i | goυoˈɾ-i-ti, goυoˈɾ-i-mo ‘to talk’ | 28.8% (863) |

| a/je | oˈɾ-a-ti, ˈoɾ-je-mo ‘to plow’ | 12.6% (378) |

| ∅/e | ˈgris-∅-ti, ˈgriz-e-mo ‘to bite’ | 9.5% (285) |

| ni/ne | ˈɾi-ni-ti, ˈɾi-ne-mo ‘to push’ | 4.8% (143) |

| e/i | zoˈɾ-e-ti, zoˈɾ-i-mo ‘to ripen’ | 4.3% (128) |

| a/e | ˈbɾ-a-ti, ˈbɛɾ-e-mo ‘to read’ | 1.5% (46) |

| a/i | ˈsliʃ-a-ti, ˈsliʃ-i-mo ‘to hear’ | 1.2% (36) |

| e/e | ˈsm-e-ti, ˈsm-e-mo ‘to be allowed’ | 1.6% (47) |

| ∅/ne | poˈsta-∅-ti, poˈsta-ne-mo ‘to become’ | 0.9% (27) |

Before we proceed, some notes on the proposed list of theme vowels are in order. While different authors propose different inventories of theme vowels in Slovenian (cf., e.g., Toporišič (2004); Šekli (2010), Simonović & Mišmaš (2022)), in this paper we assume the same classification and guidelines to determine theme-vowel classes as adopted for the annotation of the Database of the Western South Slavic verbal system (Arsenijević et al. 2021). In general, the guideline was to consider items that determine conjugation classes as theme vowels. As already indicated at the beginning of this section, this meant that we occasionally deviated form the standard understanding of theme vowels and also included some items that correlate with argument structure or aspectual properties on the list. For example, e/i, typically associated with inchoatives, as illustrated by the example in Table 1, has been argued to be a derivational affix in Simonović & Mišmaš (2022), but we include it in the list of theme vowels.

Another group that stands out is ni/ne. The morpheme ni/ne arguably marks semelfactivity (see, e.g., Dickey 2001 for an overview of Slavic) and is potentially a complex item n-i/n-e. However, other complex “verbal affixes” can be plausibly analyzed into an affix and an independently attested theme vowel (e.g., oυa/uje can be analyzed as containing the theme vowel a/je, and the biaspectual affix iɾa/iɾa can be analyzed as iɾ-a/iɾ-a, which is why it is subsumed under the a/a class). On the other hand, i/e never appears without -n- (i.e. there is no such verb as del-i-ti~del-e-mo). Pending further evidence, we remain agnostic whether semelfactivity is a property of -n- and i/e is the theme vowel or if we are dealing with a single item and leave this to future research. Crucially, the themes often associated with syntactic/semantic effects (such as e/i and ni/ne) do not host any verbs with root allomorphy, so the issue of their correct analysis is not central to our account.

One additional guideline we have used in the annotation was to assume as few classes as possible to capture as much data as possible. Based on this, some items which are sometimes taken to be theme vowels were reconsidered and reanalyzed as a combination of a verbal affix and a theme vowel. One such example prominently absent from our list is oυa/uje, which operates as a verbalizer and secondary imperfectivizer (see Simonović & Mišmaš (2022), Simonović (accepted)). Reanalyzing this element as oυ-a/u-je enabled us to reduce the number of TV-classes and subsume this class under the a/je class.10 Finally, one of the reviewers proposes two further reductions of the 10 theme-vowel classes. The first is that ∅/e should be analyzed as e/e. This suggestion is motivated by the fact that many verbs in the ∅/e class have a root-final [e] in the infinitive, e.g., uˈmre-∅-ti ‘to die’ and ˈwre-∅-t∫i ‘to throw’. However, these verbs lose this [e] in the past participle, e.g., uˈməɾ-∅-l-a ‘die-tv-pst.ptcp-f’ and ˈυəɾɡ-∅-l-a ‘throw-tv-pst.ptcp-f’ (see 3.1 for the phonological rules applying in these verbs). This is in sharp contrast with comparable verbs which keep the [e] in both the infinitive and the past participle, e.g., ˈwɾ-e-ti ‘to boil’, ˈwɾ-e-l-a ‘boil-tv-pst.ptcp-f’, which we take to be genuine e/e verbs.

The second suggestion was for the ∅/ne class to be subsumed under the a/e class because verbs like poˈstati~poˈstanemo ‘to become~we become’ can be added to this class as well and because the ∅/ne class is very small. We agree with the reviewer that this is indeed a small class. In fact, the ∅/ne class (based on the annotation in the database) only includes verbs that have 4 different roots. These are exemplified in the verbs: poˈsta-∅-ti~poˈsta-ne-mo ‘to become~we become’, ˈwspe-∅-ti~ˈwsp-nɛ-mo ‘to climb~we climb’, oˈde-∅-ti~oˈde-ne-mo ‘to cover~we cover’, zaˈtʃ-∅-ti~zaˈtʃ-nɛ-mo ‘to start~we start’. As evident form this list of ∅/ne verbs, not all the infinitives have the segment [a] before the infinitive ending, and all have -ne- in the finite form. We therefore leave the two groups as is.

The discussion of these theme-vowel classes already indicates some issues that emerge in determining the inventory of theme-vowel classes in Slovenian. The issue becomes even more pressing if we consider theme-vowel classes that also contain verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy. We focus on these in the following section.

2.4 Theme-vowel indeterminacy

Returning to our overview of theme-vowel classes in Table 1, three theme-vowel classes have the same segment as the exponent of the theme vowel in the finite and non-finite forms: a/a, i/i and e/e. The classes a/a and i/i constitute the biggest theme-vowel classes in Slovenian and are, according to Marvin (2002), also the default theme vowels.

The remaining seven classes have different exponents of theme vowels in the non-finite and in finite forms. One analytical problem that arises for some of the classes with two different exponents of the theme vowel is the issue of theme-vowel indeterminacy. That is, some verbs are analytically ambiguous and can be assigned to different theme-vowel classes. For instance, a verb like oˈɾati, illustrated in (27), could be analyzed, purely based on the final segments, as belonging to classes a/je, (27a), a/e, (27b) and ∅/e, (27c). However, the parsings in (27b) and (27c) would enforce assuming unpredictable root allomorphy, oɾ~oɾj and oɾa~oɾj, respectively.11 Therefore, the parsing in (27a) is preferred. Similarly, a verb like ˈʒɡati, illustrated in (28) could be analyzed as belonging to theme-vowel classes a/e, (28a), and ∅/e, (28b), but only the former analysis allows avoiding unpredictable root allomorphy ʒɡa~ʒɡ.

- (27)

- a.

- oˈɾ

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈoɾ

- √

- -je

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (a/je)

- b.

- oˈɾ

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈoɾj

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (a/e)

- c.

- oˈɾa

- √

- -∅

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈoɾj

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (∅/e)

- ‘to plow, we plow’

- (28)

- a.

- ˈʒg

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈʒg

- √

- -ɛ

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (a/e)

- b.

- ˈʒga

- √

- -∅

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈʒg

- √

- -ɛ

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (∅/e)

- ‘to burn, we burn’

The situation is slightly more complex in cases where the verb can be assigned to multiple classes without assuming root allomorphy, e.g., daˈjati ‘to give’, illustrated in (29). Here, the parsing in (29c) can be excluded due to unnecessary root allomorphy daja~daj, but the other two solutions both yield equally good results assuming the same root for both forms. In such cases, we non-crucially assume that verbs join the most common class, in this case a/je.

- (29)

- a.

- daˈj

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈdaj

- √

- -je

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (a/je)

- b.

- daˈj

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈdaj

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (a/e)

- c.

- daˈja

- √

- -∅

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈdaj

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (∅/e)

- ‘to give, we give’

Finally, there are cases where no theme-vowel class can offer a solution that avoids unpredictable root allomorphy. One is the verb ˈklati~ˈkoljemo ‘to slaughter~we slaughter’, illustrated in (30).

- (30)

- a.

- ˈkl

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈkol

- √

- -je

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (a/je)

- b.

- ˈkl

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈkolj

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (a/e)

- c.

- ˈkla

- √

- -∅

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈkolj

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (∅/e)

- ‘to slaughter, we slaughter’

Under every parsing in (30) there is root allomorphy (which cannot be derived by phonological rules, we return to this in 3.1) and there is no obvious way of choosing between the three options. Notably, in cases like ˈklati, the theme vowels have different exponents in finite and non-finite forms in all the possible parsings. In other cases, there is a choice between parsings with (segmentally) identical theme vowels in finite and non-finite forms and parsings with different theme vowels. A case in point is the verb ˈwzeti~ˈwzamemo ‘to take~we take’, illustrated in (31).

- (31)

- a.

- ˈwz

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈwzam

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (e/e)

- b.

- ˈwze

- √

- -∅

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈwzam

- √

- -e

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- (∅/e)

- ‘to take, we take’

Here the choice is between the classes e/e and ∅/e and this choice may be non-trivial for the analysis of root allomorphy. If we assume that the two exponents of the theme vowel e/e are indistinguishable, then in (31a), the two root allomorphs have the same piece of morphology adjacent to them and allomorphy has to be triggered non-locally, across the theme vowel. This is exactly what is proposed in Božič (2016). On the other hand, if we assume the parsing in (31b), root allomorphy could in principle still be local, i.e. triggered by the theme vowel or even by the linearly adjacent inflection ending.

The main focus of this paper is on cases like (30) and (31), which constitute an overwhelming majority of verbs with root allomorphy in Slovenian. A correct analysis of such verbs requires establishing the correct parsing into roots and theme vowels, as well as a theory of what can trigger root allomorphy. We will offer an account which involves local root allomorphy restricted to the domain of the phonological cycle in which the root is spelled out.

3 Root allomorphy in Slovenian verbs

In Section 2.4 we have shown examples of verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy, along with different possible parsings into roots and theme vowels. We also mentioned that the majority of verbs with root allomorphy in Slovenian allow multiple parsings. In this section we provide the data that support this claim, followed by generalizations about root allomorphy that can be made based on this data. We start this section by defining what we take unpredictable root allomorphy (not) to be.

3.1 What is unpredictable root allomorphy

We start by constraining the set of data we will consider, i.e. by defining what we take to be unpredictable root allomorphy. As in Bonet & Harbour (2012) we take an item (in Bonet & Harbour (2012) a set of features) to be allomorphic if it does not have a single exponent, but rather at least two contextually conditioned exponents.

A single exponent can have different phonologically derived surface forms which all correspond to the same underlying string. A clear case of phonologically predictable root allomorphy is ˈɡris-∅-ti~ˈɡriz-e-mo ‘to bite~we bite’, where the underlying /ɡɾiz/ surfaces as [ɡɾis] in the infinitive as a result of regressive voicing assimilation. Such cases which do not require special allomorphic vocabulary items and are therefore excluded from our data set. When classifying allomorphic patterns as predictable, we also allowed for the application of morphologized rules, as long as they apply across the verbal domain (see Marković 2018 for an overview of these rules in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, the closest relative of Slovenian). In (32), we list three verbs which illustrate various phonological rules.12 The URs of the three verbs can also be reconstructed from the past participle forms (ˈɡnɛt-∅-l-a ‘knead-tv-pst.ptcp-f’, uˈməɾ-∅-l-a ‘die-tv-pst.ptcp-f’ and ˈυəɾg-∅-l-a ‘throw-tv-pst.ptcp-f’, respectively, where all the segments of the root are underlying except for the schwas, which get inserted by a rule discussed below).

The first verb illustrates the general rule which turns dental stops into fricatives before [t] (in the infinitive of verbs). This rule is restricted to verbs,13 but there it applies without exceptions. Even more restricted is the next rule, which inserts an [e] between a [ɾ] and the infinitival ending, ensuring that there are no infinitives in [-ɾti] or [-ɾtʃi] in Slovenian. Finally, the last verb displays a considerable amount of allomorphy, but it can all be derived using general rules which apply in the verbal domain or more generally. The UR of the infinitive is /υɾɡ-∅-ti/, which turns to υɾkti by the general Slovenian regressive voicing assimilation (see, e.g., Jurgec (2007: 14–18)), which then becomes υɾtʃi by another infinitive-specific rule, that turns the sequence /kt/ into [tʃ]. Finally, an [e] is inserted by the infinitive-specific rule already mentioned for the second verb, whereas the initial [υ] becomes [w] by a general rule.14 In the present tense, a schwa is inserted in front of the [ɾ] between two consonants by a general rule (Jurgec 2007: 4) and the theme vowel [e] causes velars to map onto palatals, turning /υɾɡ-e-mo/ into [ˈυəɾʒemo]. This latter rule is part of a more general highly morphologized pattern of velar palatalisation which applies in different environments (Jurgec 2016; Zymet 2018; Jurgec & Schertz 2020).

- (32)

- Examples of phonologically predictable allomorphy

Gloss inf pres.1pl Common UR Relevant rule(s) ‘to knead’ ˈgnɛs-∅-ti ˈgnɛt-e-mo /ɡnɛt/ t → s /_ t ‘to die’ uˈmɾe-∅-ti uˈmɾ-ɛ-mo /umɾ/ ∅ → e / r _ ti (in the inf) ‘to throw’ ˈwɾe-∅-t∫i ˈυəɾʒ-e-mo /υɾɡ/ regressive voicing assimilation kt → t∫ (in the inf) ∅ → e / r _ ti/t∫i (in the inf) υ → w / _C ∅ → ə / C _ rC g → ʒ / _ e (theme vowel)

We presented a detailed discussion of the three verbs because, despite a sizable amount of surface allomorphy, they stand in sharp contrast with verbs like ˈklati~ˈkoljemo ‘to slaughter~we slaughter’ or ˈʒeti~ˈʒanjemo ‘to harvest~we harvest’, which we take to be genuine cases of unpredictable allomorphy. In order to analyze these latter verbs as deriving from a single UR string, we would need to assume processes which have no support in the rest of the system. This has already been discussed in Božič (2016: 140), who states that we can purely descriptively relate the two exponents by a deletion process but also states that “the occurrence of the vowels and sonorants […] that delete is in no way restricted by the synchronic phonology of Slovenian.” We will return to the relation between the phonological shapes of the two allomorphs in 3.3.

In addition to excluding all items where allomorphy is predictable, we also excluded items which plausibly express only functional structure and therefore may have no roots. In this sense, we follow the DM tradition in distinguishing between suppletion and morphophonological allomorphy. As Harley & Noyer (2014: 474) state, “suppletive allomorphy occurs where different Vocabulary Items compete for insertion into an f-morpheme”. This typically leads to the insertion of items which have no phonological overlap (like go and went in English). Morphophonological allomorphy, on the other hand, targets l-morphemes and “occurs where a single Vocabulary Item has various phonologically similar underlying forms, but where the similarity is not such that Phonology can be directly responsible for the variation” (see also Siddiqi 2009: 46). This criterion eliminated four verbs with their derivational families from our data set. These verbs are listed in (33).15 Apart from their meaning, these verbs also show a range of morphological and morphosyntactic effect not encountered in the rest of the verbal domain, as, for instance, portmanteau allomorphs which also include negation, illustrated by ˈnismo ‘we are not’ and ˈnot∫emo ‘we don’t want’.

- (33)

- Verbs with suppletion

Gloss inf pres.1pl ‘to be’ ˈbiti ˈsmɔ ‘to go’ ˈiti ˈgɾemo ‘to want’ xoˈteti ˈxot∫emo (ˈt∫mɔ/ˈt∫ɛmo) ‘to can’ ˈmɔt∫i ˈmoɾemo

Having eliminated items where root allomorphy is phonologically predictable, as well as those where the presence of a root is questionable, we are left with a list of items which will be presented in the following section.

3.2 Overview of verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy

In what follows we overview verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy from the database described in footnote 9, which contains the 3000 most common verbs in Slovenian. The part of the database that contains information about root allomorphy (and inflection) is already available in Marušič et al. (2022). While the list is not exhaustive (for example, the verb ˈkleti~ˈkɔwnemo ‘to swear~we swear’ did not make the cut), we believe the data is representative and substantial enough to establish the relevant generalizations about allomorphy in Slovenian verbs.

The verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy in our sample are given in two tables. Table 2 lists the few verbs with root allomorphy that can only be analyzed as belonging to one theme-vowel class. We give each verb in two forms, based on which the allomorphs of each individual root are apparent.

Verbs with root allomorphy – one analysis possible.

| Theme-vowel class | Example (infinitive, prs.1pl) | Gloss |

| a/i | ˈst-a-ti, stoˈj-i-mo | ‘to stand’ |

| a/i | ˈb-a-ti, boˈj-i-mo | ‘to fear’ |

| ∅/e | ˈjes-∅-ti, ˈj-e-mo | ‘to eat’ |

Table 3 lists all the verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy in our database that can be analyzed as belonging to different theme-vowel classes. All the possibilities are given in the table. In the database, the verbs were always annotated as belonging to the biggest of the possible theme-vowel classes, i.e. the leftmost possible class in the table.

Verbs with root allomorphy and alternative parsings.

| a/je | a/e | ∅/e | ∅/ne | e/e | Gloss | |

| inf | ˈkl-a-ti | ˈkl-a-ti | ˈkla-∅-ti | ‘to slaughter’ | ||

| prs.1pl | ˈkol-je-mo | ˈkolj-e-mo | ˈkolj-e-mo | |||

| inf | ˈgn-a-ti | ˈgna-∅-ti | ˈgna-∅-ti | ‘to goad’ | ||

| prs.1pl | ˈʒɛn-e-mo | ˈʒɛn-e-mo | ˈʒɛ-ne-mo | |||

| inf | poˈυed-a-ti | poˈυeda-∅-ti | ‘to tell’ | |||

| prs.1pl | poˈυ-e-mo | poˈυ-e-mo | ||||

| inf | po-ˈzυ-a-ti | po-ˈzυa-∅-ti | ‘to call’ | |||

| prs.1pl | po-ˈzɔυ-e-mo | po-ˈzɔυ-e-mo | ||||

| inf | ˈbɾ-a-ti | ˈbɾa-∅-ti | ‘to read’ | |||

| prs.1pl | ˈbɛɾ-e-mo | ˈbɛɾ-e-mo | ||||

| inf | pɾeˈje-∅-ti | pɾeˈj-e-ti | ‘to recieve’ | |||

| prs.1pl | ˈpre̞jm-e-mo | ˈpre̞jm-e-mo | ||||

| inf | ˈmle-∅-ti | ˈml-e-ti | ‘to grind’ | |||

| prs.1pl | ˈmelj-e-mo | ˈmelj-e-mo | ||||

| inf | ˈwne-∅-ti | ˈwn-e-ti | ‘to ignite’ | |||

| prs.1pl | ˈwnam-e-mo | ˈwnam-e-mo | ||||

| inf | pɾiˈje-∅-ti | pɾiˈj-e-ti | ‘to grab’ | |||

| prs.1pl | ˈpɾim-e-mo | ˈpɾim-e-mo | ||||

| inf | ˈpe-∅-ti | ˈp-e-ti | ‘to sing’ | |||

| prs.1pl | ˈpɔj-e-mo | ˈpɔj-e-mo | ||||

| inf | ˈυede-∅-ti | ˈυed-e-ti | ‘to know’ | |||

| pres.1pl | ˈυ-e-mo | ˈυ-e-mo | ||||

| inf | ˈʒe-∅-ti | ˈʒ-e-ti | ‘to reap’ | |||

| prs.1pl | ˈʒanj-e-mo | ˈʒanj-e-mo | ||||

| inf | za-ˈt∫e-∅-ti | za-ˈt∫e-∅-ti | za-ˈt∫-e-ti | ‘to begin’ | ||

| pres.1pl | za-ˈt∫n-ɛ-mo | za-ˈt∫-nɛ-mo | za-ˈt∫n-ɛ-mo | |||

| inf | ˈme-∅-ti | ˈme-∅-ti | ˈm-e-ti | ‘to rub’ | ||

| prs.1pl | ˈman-e-mo | ˈma-ne-mo | ˈman-e-mo |

To make Table 3 easier to follow, we only included one verb per alternation pattern, so the total number of roots with allomorphy is larger than what the table shows. The verbs that are not shown in the table are ˈpɾati ‘to wash’ (behaves exactly like ˈbɾati ‘to read’), ˈsneti ‘to take off’, obˈjeti ‘to hug’ and ˈwzeti ‘to take’ (behave like ˈwneti ‘to ignite’) and zaˈpeti ‘to close’ (behaves like zaˈt∫eti ‘to begin’).

Some further remarks about Tables 2 and 3 are needed. First, when possible, we only included simplex, i.e. unprefixed, verbs. For example, Table 3 includes only the verb ˈbɾati ‘to read’, but verbs like pɾeˈbɾati ‘to finish reading’ and razˈbɾati ‘to figure out’ also exist and are included in the database. Since the prefix influences neither the form of the root (i.e. same allomorphs are found in prefixed verbs) nor the theme vowel, excluding prefixation does not influence the set of roots and allomorphs. This, however, does mean that the number of verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy is larger than what is shown in the table.

The verb ˈbɾati is also an example of a verb with two interpretations – ‘to read’ and ‘to gather’. Since both meanings are associated with the same allomorphy pattern, we only list it once. The situation is different with the verb ˈpeti ‘to sing’. Its prefixed version zaˈpeti ‘to start singing’ is homophonous with zaˈpeti ‘to close’ only in the infinitive, but the present tense forms of these verbs reveal totally different allomorphic patterns: za-ˈpɔjemo ‘we start singing’ and zaˈpnɛmo ‘we close off’, respectively. These two are therefore registered as separate verbs.16

Some verbs included in Table 3 have a prefix separated with a hyphen. These verbs illustrate roots that only ever appear with prefixes (i.e. *t∫eti does not exist, but za-ˈt∫eti ‘to start’, po-ˈt∫eti ‘to do’ etc. do and are in the database). Verbs that historically contain a prefix, but are not perceived as prefixed in modern Slovenian are marked as simplex, e.g., ˈsneti ‘to take off’, ˈwzeti ‘to take’ and poˈυedati ‘to tell’. Roots which only appear with prefixes are not specific to the class of verbs with root allomorphy, they can be found among regular verbs as well. Examples of regular ‘bound’ verbs are -u-∅-ti, e.g., in oˈb-u-∅-ti ‘to put shoes on’ or -ˈɡəɾ-ni-ti, in za-ˈɡəɾ-ni-ti ‘to draw close’, po-ˈɡəɾ-ni-ti ‘to spread out’, od-ˈɡəɾ-ni-ti ‘to draw back’.

3.3 Unattested patterns

The first, most salient generalization is that four theme-vowel classes are totally absent from the overview of verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy: a/a, i/i, ni/ne and e/i. The first two are the most common theme-vowel classes, which account for almost two thirds of all verbs and have been argued to be default in Marvin (2002). The other two have been mentioned in the introduction as the best candidates for ‘atypical’ theme vowels, which carry syntactic/semantic information.

A second generalization can be made concerning the exponents of the theme vowel. In the context of the discussion of non-local allomorphy, the case for non-local allomorphy in Božič (2016) was built on cases like ˈʒeti~ˈʒanjemo ‘to harvest~we harvest’, segmented as ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo, where root allomorphy is triggered across the same theme vowel. If we leave aside the possibility of classifying this verb as ∅/e, and stick to the parsing proposed by Božič, there is still one aspect in which the two exponents of the theme vowel are different: stress. The verb is stressed ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo. If stress is taken into account, in the entire dataset of verbs with root allomorphy, there is no single verb in which the finite and the non-finite forms have the exact same exponent of the theme vowel.

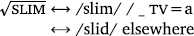

The third generalization, which also relates to stress, is that there are no verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy which have overt theme vowels in both finite and non-finite forms and have stress on the root in both finite and non-finite forms. So, while there are regular verbs like ˈsliʃ-a-ti~ˈsliʃ-i-mo ‘to hear~we hear’, there are no verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy like ˈslim-a-ti~ˈslid-i-mo. This may seem like a minor point, but the stress pattern in ˈsliʃ-a-ti~ˈsliʃ-i-mo is by far the most common in Slovenian, so its absence from verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy is telling.

Finally, there is a tendency (whose strength depends on the chosen parsing) especially important for cases like ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo. In an overwhelming majority of cases, such verbs have one root allomorph which has a vowel and one which only consists of consonantal material. Since the issue of assignment of verbs in our data set to theme-vowel classes has important consequences for the analysis of root allomorphy, we turn to the issue of theme-vowel class indeterminacy first.

4 Resolving theme-vowel class indeterminacy and the triggers of root allomorphy

In assigning verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy to theme-vowel classes, we can follow two general approaches. One is concentrating all verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy in as few theme-vowel classes as possible. Applied to our data set, this would put all verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy in only two classes: ∅/e and a/i, see tables 2 and 3. The other approach is to follow the guideline “if it looks like a theme vowel, it is a theme vowel”, i.e. making root allomorphs as small as possible and theme vowels as big as possible. This approach leads to a classification (shown in Table 3) where up to five theme-vowel classes can host verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy: a/je, a/e, ∅/e, ∅/ne and e/e.

The first approach makes the analysis of root allomorphy extremely simple. For the two roots in the a/i class, root allomorphy will be triggered by one of the theme vowels, whereas in all other cases, it can be triggered by the absence of an overt theme vowel, i.e. by the exceptionally adjacent Infl. The latter type of analysis has been proposed for Italian in Calabrese (2015). However, this solution has an important problem: out of 20 roots that would be classified as ∅/e, in front of the null theme, 6 would have the vowel [a] and 13 would have the vowel [e]. This is especially unexpected because in the much bigger domain of regular ∅/e verbs, there is no verb whose root exponent ends in [a], i.e. there are no verbs like pona-∅-ti~pona-je-mo ([j] being the epenthetic hiatus-resolver) and there are only two roots that end in [e]: ˈgɾe-∅-ti~ˈgɾe̞-je-mo ‘to heat~we heat’ and ˈ∫te-∅-ti~ˈ∫te̞-je-mo ‘to count~we count’. Finally, both generalizations concerning prosody from Subsection 3.3 would be accidental.

This is why we will implement the alternative approach, analyzing theme vowels as being maximally big and roots as being maximally small. In the few cases where the choice is between the classes e/e and ∅/ne (in the type illustrated by za-ˈt∫eti~za-ˈt∫nɛmo ‘to start~we start’, where under each parsing two segments belong to theme vowels), the parsing was made in such a way to have one syllabic and one consonantal root allomorph. This choice is not crucial and was made to have more testing ground for the purely phonological account which we propose for verbs that have this type of allomorphy.

In Table 4, we repeat the overview of root allomorphy types from Tables 2 and 3 with the parsing assumed here.

Verbs with root allomorphy – theme vowels being maximally big, roots maximally small approach.

| TV class | Example (infinitive, prs.1pl) | Gloss | Other examples |

| a/i | ˈb-a-ti, boˈj-i-mo | ‘to fear’ | ˈstati ‘to stand’ |

| ∅/e | ˈjes-∅-ti, ˈj-e-mo | ‘to eat’ | |

| ∅/ne | za-ˈt∫e-∅-ti, za-ˈt∫-nɛ-mo | ‘to start’ | zaˈpeti ‘to close’ |

| a/je | ˈkl-a-ti, ˈkol-je-mo | ‘to slaughter’ | |

| a/e | ˈbɾ-a-ti, ˈbɛɾ-e-mo | ‘to read’ | ˈpɾati ‘to wash’ |

| a/e | ˈɡn-a-ti, ˈʒɛn-e-mo | ‘to goad’ | |

| a/e | poˈυed-a-ti, poˈυ-e-mo | ‘to tell’ | |

| a/e | po-ˈzυ-a-ti, po-ˈzɔυ-e-mo | ‘to call’ | |

| e/e | ˈʒ-e-ti, ˈʒanj-e-mo | ‘to reap’ | |

| e/e | ˈp-e-ti, ˈpɔj-e-mo | ‘to sing’ | |

| e/e | pɾeˈj-e-ti, ˈpɾe̞jm-e-mo | ‘to receive’ | |

| e/e | pɾiˈj-e-ti, ˈpɾim-e-mo | ‘to grab’ | |

| e/e | ˈυed-e-ti, ˈυ-e-mo | ‘to know’ | |

| e/e | ˈml-e-ti, ˈmelj-e-mo | ‘to grind’ | |

| e/e | ˈm-e-ti, ˈman-e-mo | ‘to rub’ | |

| e/e | ˈwz-e-ti, ˈwzam-e-mo | ‘to take’ | ˈwneti ‘to ignite’ |

| ˈsneti ‘to take off’ | |||

| obˈjeti ‘to hug’ |

As shown in Section 3.3, if we take stress into account, all verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy have different exponents of the adjacent theme vowel. This means we could use allomorphic Vocabulary Items which only refer to the exponent of the theme vowel to obtain allomorphy. We show this in (34) and (35) for ˈb-a-ti~boˈj-i-mo ‘to fear~we fear’ and ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo ‘to harvest~we harvest’, respectively.

- (34)

- (35)

The model we have presented so far predicts that root allomorphs can be triggered in all verbs that have (segmentally and/or prosodically) different exponents of theme vowels. Here we encounter the problem of over-generating. The present version of the model can derive the type ˈslim-a-ti~ˈslid-i-mo, with both theme vowels overtly expressed and unstressed. The relevant Vocabulary Item which would derive such a verb is shown in (36).

- (36)

In the following section, we will refine the model to exclude verbs like ˈslim-a-ti~ˈslid-i-mo. We will argue that the spellout of the root can only be influenced by a subset of theme vowels, i.e. those theme vowels that are spelled out together with the root. As argued in 2.2, only stressed theme vowels are spelled out together with the root, and can therefore trigger root allomorphy. We turn to the implementation of this idea in the following section.

5 Spellout domains and allomorph selection in Slovenian verbs

In 2.2 we argued, based on the prosody of regular verbs in Slovenian, that stressed theme vowels get spelled out in the same phase as the root, whereas unstressed theme vowels get spelled out in the following phase. Assuming that the spellout domain defined in 2.2 is also the locality domain within which root allomorphy can be triggered enables us to exclude the unattested type ˈslim-a-ti~ˈslid-i-mo. In other words, only the theme vowels that get spelled out in the same cycle with the root (i.e. stressed theme vowels) can influence the spellout of the root. In this section, we will discuss the exact mechanisms by which this triggering can occur.

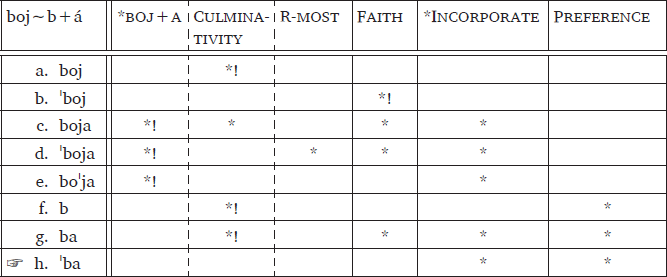

We first turn to the few cases where no phonological conditioning can be assumed. At the end of Section 4, we proposed DM style Vocabulary Items for roots with unpredictable allomorphy. In (37) we repeat the proposed Vocabulary Item for ˈb-a-ti~boˈj-i-mo ‘to fear~we fear’.

- (37)

This is essentially a root-specific spellout instruction. In our OT implementation, it can be translated into a root-specific constraint, as defined in (38).

- (38)

- *boj+a

- Assign a violation mark for every candidate in which

is expressed as /boj/ when the adjacent morpheme is the theme vowel -a-.

is expressed as /boj/ when the adjacent morpheme is the theme vowel -a-.

We implement the underlying representations of roots with unpredictable root allomorphy as ordered pairs (a,b), where a and b are the elsewhere and the context-dependent allomorph, respectively (see Nevins 2011 for an overview of phonological treatments of allomorphy). In the case of the root  that would be (boj, b). The root-specific constraint is never violated, so it is placed at the top stratum of the ranking. At the bottom, we added the constraint Preference, which militates against using the second allomorph in the ordered-pair representation.

that would be (boj, b). The root-specific constraint is never violated, so it is placed at the top stratum of the ranking. At the bottom, we added the constraint Preference, which militates against using the second allomorph in the ordered-pair representation.

- (39)

- Preference

- If a morpheme’s underlying representation is the ordered pair (a,b), assign a violation mark for every candidate in which b is the exponent of that morpheme.

- (40)

- Complex UR + stressed theme (with a root-specific constraint): ˈbati ‘to fear’

- (41)

- Complex UR + stressed theme (with a root-specific constraint): boˈjimo ‘we fear’

One advantage of this approach is that there is no need to stipulate that root-specific constraints can only refer to stressed/local theme vowels. This generalization follows from the ranking. Since the root-specific constraint only refers to the output of the first phase, it only blocks candidantes which also violate *Incorporate, so that the root-specific constraint never decides the winner. This is shown in (42), where the same underlying representation as in the tableau above is combined with an unstressed theme. Now the winner ˈboj-a-ti has the elsewhere allomorph, and no root allomorphy emerges (just like in attested verbs like ˈsli∫-a-ti~ˈsli∫-i-mo ‘to hear~we hear’). Crucially, in such cases, the root-specific constraint plays no role in the evaluation and can be omitted from the grammar without any consequence. Moreover, the second member of the ordered pair does not surface and can therefore be expected to be eliminated from the underlying representation.

- (42)

- Complex UR + unstressed theme (with a root-specific constraint)

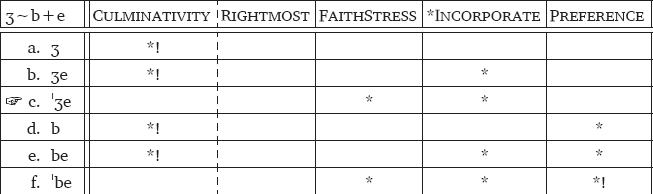

Our proposed ranking has the virtue of correctly restricting the domain within which root-specific allomorphy can be triggered in Slovenian. However, it is clear that root-specific constraints that need to be memorized together with their ranking are quite a burden for the learner and the system may be expected to tend towards simplification. This is exactly what we find. As mentioned in Section 3.3, in addition to having one stressed and one unstressed theme vowel, a vast majority of verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy have one syllabic and one consonantal allomorph. One example of such a verb is ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo ‘to harvest~we harvest’. In what follows, we show that the root-allomorphy pattern of such verbs can be derived without any root-specific constraints.

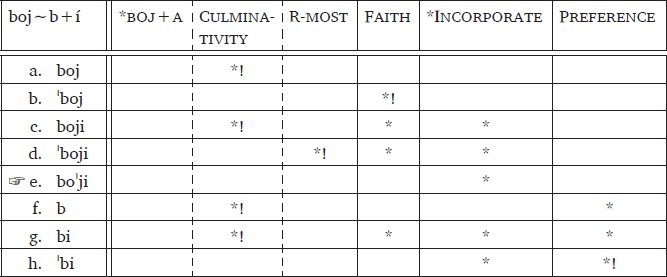

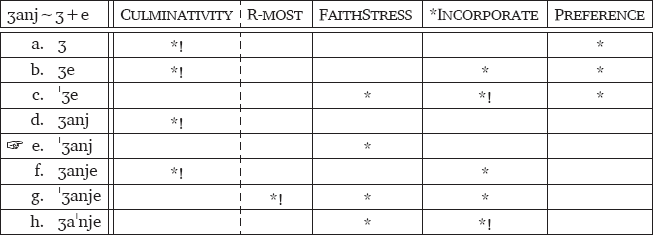

The stress pattern in ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo indicates that the theme vowel of the non-finite forms is stressed, whereas the theme vowel of finite forms is unstressed. Such a pattern is also attested in regular verbs like ɾazuˈm-e-ti~ɾaˈzum-e-mo ‘to understand~we understand’. If the underlying representation of the allomorphic root is (ʒ, ʒanj), the allomorphy is derived by the ranking, without any root-specific constraints. The tableau in (43) shows the evaluation with a stressed theme vowel. As with regular verbs, the incorporation of the theme vowel is enforced and it is only Preference that decides between the two incorporating candidates.

- (43)

- Complex UR + stressed theme: ˈʒeti ‘harvest’

In the tableau in (44), we show the evaluation with the same underlying representation with an unstressed theme vowel. The winner is now the candidate which features the disprefered root allomorph without the incorporation of the theme vowel. This yields the combination ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo without any further assumptions or morpheme-specific constraints.

- (44)

- Complex UR + unstressed theme: ˈʒanjemo ‘we harvest’17

The allomorphic pattern can be obtained in this way for a vast majority of verbs in our sample. Out of the 16 types of allomorphic roots in Table 4, 13 can be analyzed as ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo without any further assumptions, two (preˈj-e-ti~ˈpre̞jm-e-mo ‘to receive~we receive’ and priˈj-e-ti~ˈprim-e-mo ‘to grab~we grab’) require some further assumptions regarding the internal structure of the root, and only the type illustrated by ˈb-a-ti~boˈj-i-mo ‘to fear~we fear’ definitely requires a root-specific constraint.

Completing our analysis, we need to make sure that including complex URs does not open the door for unattested types of root allomorphy. In the domain of syllabic/consonantal pairs, the root allomorphy pattern featured in ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo is only predicted in cases where the root has a preferred consonantal allomorph and a dispreferred syllabic allomorph. In the opposite case, a regular verb emerges, as shown in (45) and (46). As in the evaluation in (42), the dispreferred allomorph never surfaces, so that it can be excluded from the UR without any consequences.

- (45)

- Unattested complex UR (ʒanj, ʒ) + stressed theme

- (46)

- Unattested complex UR (ʒanj, ʒ) + unstressed theme

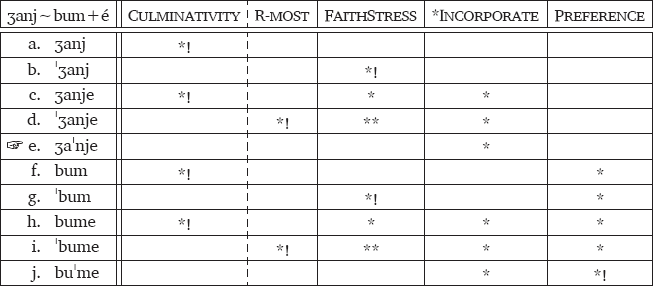

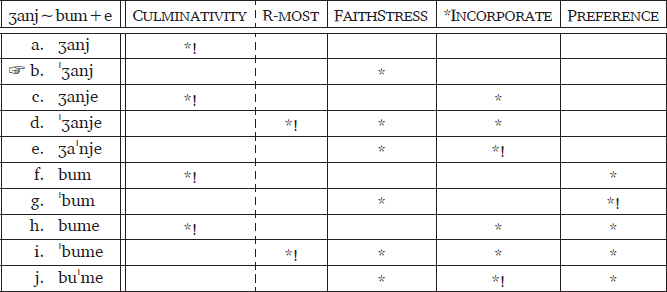

We need to also check whether complex representations displaying the same shape (i.e. two syllabic or two consonantal allomorphs) stand any chance of producing root allomorphy. The tableaux in (47) and (48) show the evaluation of the non-existing complex UR (ʒanj, bum). The result is again a regular verb and the UR can be reduced to ʒanj.

- (47)

- Unattested complex UR ʒanj∼bum + stressed theme

- (48)

- Unattested complex UR ʒanj∼bum + unstressed theme

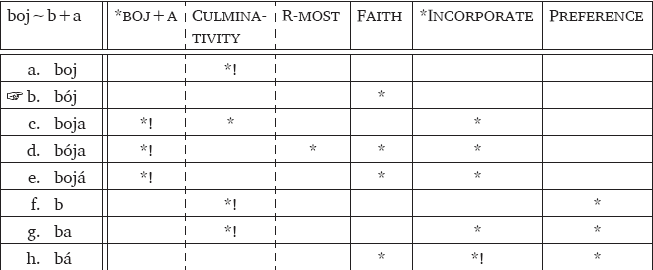

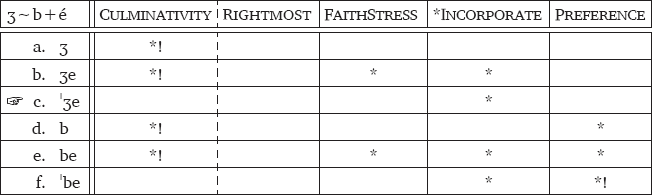

Finally, in the tableaux in (49) and (50), we show the evaluation of the non-existing complex UR (ʒ, b). The result is again a regular verb (comparable to the attested ˈsm-e-ti~ˈsm-e-mo ‘to be allowed ~ we are allowed’) and the UR can be reduced to ʒ.

- (49)

- Unattested complex UR ʒ∼b + stressed theme

- (50)

- Unattested complex UR ʒ∼b + unstressed theme

This concludes our analysis of root allomorphy patterns in Slovenian verbs. We have shown that a correct account of the data can be provided by implementing ordered-pair representations for allomorphic roots in an OT ranking which, apart from standard phonological constraints, also involves a violable constraint on the incorporation of the head into the spellout domain.

5.1 Residual issues: Similarities between the allomorphs and intrinsic ordering of the allomorphs

In this section we address two residual issues related to the complex representations assumed here. One is the issue of phonological similarities between the two listed allomorphs, the other is the possibility of dispensing with the ordering of the allomorphs and the constraint Preference that refers to it.

As discussed in 3.1, we follow Božič (2016: 140) in the assumption that the two root allomorphs cannot be derived from a single underlying string although they display some similarities. We remained faithful to this idea, even though we in the end united the two allomorphs under the same underling representation, because this underlying representation is complex and its two elements are independent from each other. In this we also follow Kager (2008), who assumes complex representations in a minor allomorphy pattern in Dutch that could be described as lengthening for an overwhelming majority of items. The main argument is that this is a minor pattern, found in only a handful of words, whereas the rest of the language shows no length alternation. In relation to this, one of the reviewers raises the issue of the similarities between the two root allomorphs in our data set. Specifically, using the toy underlying representation /ʒ~bum/ and combining it with theme vowels é/e and our proposed constraint ranking, they arrive at the verb ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈbum-e-mo. The reviewer claims that such a verb is impossible because all allomorph pairs in our data set have the same initial consonant “except when a predictable phonological rule applies, as in the case of ˈgnati~ˈʒɛnemo ‘to prod~we prod’ and that therefore our analysis produces a pathology. Our intuition is that it is all but clear that modern speakers can derive the initial consonants in ˈɡnati~ˈʒɛnemo from the same underlying segment. While there is growing body of evidence that velar palatalisation is productive at the morpheme boundary (Jurgec 2016; Zymet 2018; Jurgec & Schertz 2020), we are not aware of any robust evidence for active root-internal velar palatalisation, which would lead the speakers towards the analysis assumed by the reviewer. Jurgec & Schertz (2020) do show that in nonce words speakers prefer postalveolars over velars morpheme-internally, but this cannot be taken as direct evidence of active morpheme-internal palatalisation, since speakers can also assume underlying postalveolars in such words. Moreover, Slovenian speakers are also exposed to exceptions to the velar palatalisation even at morpheme boundaries in the verbal domain (e.g., in ˈʒɡati~ˈʒɡɛmo ‘to burn~we burn’).18 We agree, however, that further descriptive and experimental research is necessary in order to establish the full picture. In case it is established that initial consonant faithfulness has some reality, one solution to test would be that proposed by Kager (2008) for non-alternating aspects of the Dutch allomorphy pattern: Output-Output Faithfulness (Burzio 1996; Benua 1997, but see Bobaljik 2012 for a critical assessment in DM terms), which puts a limit to how different the two allomorphs can be. Alternatively, the limitations of allomorphy can be formalized in terms of lexical conservatism (Steriade 1997).

One important aspect in which our proposed analysis differs from Kager’s lies in the fact that our complex underlying representations are ordered pairs, whereas Kager uses unordered pairs. In what follows we briefly consider the possibility of reducing our representations to unordered pairs. Leaving aside the few cases where root-specific constraints need to be assumed (and where therefore either order of the listed allomorphs can be assumed without any consequence), all examples of complex representations that result in root allomorphy look like ʒ~ʒanj (which results in ˈʒ-e-ti~ˈʒanj-e-mo), i.e. with the consonantal allomorph listed first. This means that the effect of the constraint Preference can be achieved by another constraint which prefers the shorter allomorph. The best candidate is *Structure (Prince & Smolensky 1993; Zoll 1993), which militates against any amount of structure. This constraint has been used in comparable analyses of Slovenian before (Simonović & Mišmaš (2020) and Simonović (2020)), but since it has been criticized on more general grounds (Gouskova 2003), we attempted at formulating the proposal without it.

6 Conclusion

In this paper we tackled the interaction of theme vowels and roots in Slovenian, especially in the domain where this interaction leads to phonologically unpredictable root allomorphy. We addressed the problem of analytical ambiguity caused by the fact that theme-vowel exponents of some theme-vowel classes contain theme-vowel exponents of other classes. This issue was shown to be especially pressing in verbs that exhibit root allomorphy, as the analysis of such verbs requires establishing the correct parsing into roots and theme vowels, as well as a theory of what can trigger root allomorphy.

We offered an account of root allomorphy informed by the more general account of how prosody is computed in the system. We showed that root allomorphy is local, i.e. restricted to the domain of the phonological cycle in which the root is spelled out. This locality follows from the proposed OT ranking, which includes a violable constraint on the incorporation of the head into the spellout domain.

While our account covered various aspects of root allomorphy in verbs in Slovenian, there are certainly many open questions left for further research. One puzzle that still remains open is that of the four classes which never host verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy listed in 3.3: the two largest classes (a/a and i/i) and the two classes argued to have syntactic/semantic content (e/i and ni/ne). All of these classes allow stressed theme vowels, so the position of the theme vowel cannot be the reason. In resolving this issue, both a synchronic and a diachronic perspective will be instructive, since verbs with unpredictable root allomorphy all belong to the oldest stratum of Slovenian lexicon and their restrictions to certain theme-vowel classes may reflect some regularities of older stages of Slovenian.

Abbreviations

1 = first person, 2 = second person, 3 = third person, f = feminine, inf = infinitive, ipfv = imperfective, pl = plural, pfv = perfective, prs = present, pst = past, ptcp = participle, sg = singular

Notes

- We use IPA for Slovenian examples throughout the paper. [^]

- In fact, Gribanova (2015: 539) notes the same for Russian, but nonetheless associates the theme vowel -a- in Russian to the imperfective Aspect head, because the imperfect interpretation is much more common. [^]

- For completeness, we provide the relative frequences of the three stress patterns in our sample of 3000 verbs. The pattern with stress on the syllable preceding the theme vowel (illustrated by ˈur-i-ti~ˈur-i-mo) is encountered in 65% of all verbs and 57% of the verbs in the i/i class. The pattern with stress on the theme vowel (illustrated by doˈb-i-ti~doˈb-i-mo) is attested in 20% of all verbs and 41% of the verbs in the i/i class. Finally, the mobile pattern illustrated by loˈm-i-ti~ˈlom-i-mo is encountered in 23% of all verbs and 24% of i/i verbs. The percentages do not add up to 100% because some verbs were marked for more than one stress pattern. [^]

- We have not identified any pressing evidence that roots which show up under vP have lexical prosody, which is why we will assume that the two roots have the underlying representations /ɡoljuf/ and /zanim/. However, even if lexically stressed versions of these roots are implemented in our OT evaluation, the same two-way contrast arises, the only difference being that all roots stressed at the end will surface with lexical root stress. Crucially, no additional prosodic patterns arise. [^]

- As one of the reviewers notes, undominated Rightmost is not comapatible with the exceptional denominal items like ˈpɾidiɡ-a-ti ‘to preach’. We follow the analysis in Simonović (accepted), in which denominal verbs are spelled out differently, with just the nominal structure in the first phase (in this case the sequence [ˈpɾidiɡ]). This nominal structure preserves the lexical stress because of the ranking be Faith-Noun»Faith, which also accounts for far more liberal prosody in nouns than in other categories. [^]

- This only concerns primary stress, but see Jurgec (2007; 2010) for secondary stress in Slovenian. As for the footing in Slovenian, Jurgec (2007; 2010) argues for trochaic feet, whereas Simonović (accepted) argues for iambs. [^]

- One of the reviewers points out that we should also consider a theme vowel with a complex representation, with one accented and one unaccented allomorph, e.g., /á~a/. In this case, FaithStress would be satisfied by all candidates and *Incorporate would block head incorporation, which would result in root-final stress. This means that the theme vowel /á~a/ would yield the same result as /a/. Consequently, the former can be simplified to the latter. [^]

- The form of the root does not influence the choice of the theme vowel class, as two roots with the same surface form can appear with different themes.

- (i)

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to work, we work’

[^]- (ii)

- deˈl

- √

- -i

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- deˈl

- √

- -i

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to share, we share’

- This sample represents the Slovenian database of the larger Database of the Western South Slavic verbal system or WeSoSlav (Arsenijević et al. 2021). The Slovenian database consists of 3000 most frequent verbs in the (partial) Slovenian national corpus Gigafida (Logar-Berginc et al. 2012). We take these 3000 verbs as representative of the entire Slovenian verbal system. These verbs were annotated for several different properties, such as stress, root allomorphy, argument structure etc. The annotation for stress was based on the intuitions of 2 annotators and the stress marks in the dictionary of standard literary Slovenian (Bajec 2014). While this led to many verbs marked for more than one stress pattern, there was no variation for the verbs in focus here. In addition to the annotation for stress, information about root allomorphy and theme-vowel class is available in the already published part of the database (Marušič et al. 2022). [^]

- One of the reasons why oυa/uje is traditionally considered on a par with theme vowels is that oυa/uje often appears to replace the original theme vowel in secondary imperfectivizations. In order to illustrate this with an example, we give a minimal overview of the most typical way aspect morphology is expressed in Slovenian in (i). Simplex verbs (i.e. those that only contain a root, a theme vowel and inflectional morphology) are typically imperfective, (ia), (Toporišič 2004: 348). They most commonly get perfectivized trough prefixation, (ib). The perfective verb can again become imperfectivized trough suffixation, (ic).

- (i)

- a.

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to work.ipfv, we work.ipfv’

- b.

- pɾe-

- prefix-

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -ti,

- -inf,

- pɾe-

- prefix-

- ˈdel

- √

- -a

- -tv

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to process.pfv, we process.pfv’

The elements marked as sec.imp in (ic) appear in the same position as the theme vowel -a- in (ia). However, as discussed in Quaglia et al. (submitted), and as clear from our example in (9) above, some secondary imperfectivizers arguably preserve the original theme vowel of the perfective verb. Moreover, all secondary imperfectivizers are complex and they all end in a theme vowel. In the case of oυa/uje, the parsing is oυ-a/u-je, and this group of verbs can be included in the theme-vowel class a/je. The parsing oυ-a/u-je is accepted even in more traditional approaches. For instance, Šekli (2010: 141) has oυ-a/u-je verbs as a separate class (next to the a/je class), but consistently includes the segmentation used here. This class is also the only class in his list characterized by a complex alternating sequence. [^]- c.

- pɾe-

- prefix-

- del

- √

- -oˈυa

- -sec.imp

- -ti,

- -inf,

- pɾe-

- prefix-

- deˈl

- √

- -uje

- -sec.imp

- -mo

- -prs.1pl

- ‘to process.ipfv, we process.ipfv’

- Avoiding excessive allomorphy is not only an analytical tool, but has also been assumed to be part of the constraint set in many OT approaches (e.g., Uniform Exponence in Kenstowicz (1996)). [^]

- We describe these patterns in terms of rules for presentational purposes, but a constraint-based analysis is also possible. The descriptions of the phonological processes are by no means meant as exhaustive phonological accounts, but rather serve as illustrations of processes that apply more broadly and therefore never lead to listed allomorphs. [^]

- Although there are occasional non-transparent derivations in other domains, e.g., ˈslast ‘deliciousness’ is related to the adjective ˈslad-ək ‘sweet’ and the noun slad-ˈitsa ‘desert’. [^]

- More precisely, this underlying /υ/ is realized as a prelabialisation of the following consonant (Jurgec 2007: 95), so the more accurate representation would be wɾetʃi. [^]

- We also excluded all the prefixed forms of ˈiti ‘to go’ where the former has allomorphs i, id, for example zaˈiti~zaˈidemo ‘to stray~we stra’, odˈiti~odˈidemo’to leave ~we leave’, ˈsniti~ˈsnidemo ‘to meet ~we meet’. In the last verb sn- is no longer a productive prefix. [^]

- A note on database is in order here. The starting point of the database was a list of infinitive forms based on the Slovenian national corpus Gigafida, in which verbs are not annotated for meaning. This means that homophonous verbs are counted as one. For example, the abovementioned zaˈpeti means both ‘to start to sing’ and ‘to close’. In such cases, the annotators were instructed to select one meaning of the infinitive that they consider more prominent and annotate the properties of the verb with that meaning. In the case of zaˈpeti the annotators selected the meaning ‘close’. [^]

- This tableau contains the ranking argument for ranking *Incorporate above Preference, as under the opposite ranking candidate c would have won. [^]