1 Introduction

This article deals with a particle based verum strategy in Spanish that will be compared to the semantically equivalent strategies in German and English. All three languages have a variety of different ways to achieve an effect akin to verum. The empirical focus of this article is on the three strategies that are given in (1). The reason that these are chosen is because they can be shown to result from stress on sentence mood. It is possible that in other strategies the verum effect arises for different reasons and warrant a different analysis. In the English strategy in (1-a), verum is expressed through stress on an auxiliary. In the German strategy, it is expressed through stress on the finite verb (1-b). Finally, in the Spanish strategy relevant here, a particle is inserted (1-c).

- (1)

- A: I don’t know whether John is coming to the party or not.

- a.

- English1

- B: He is coming.

- b.

- German

- B:

- Er kommt.

- he comes

- c.

- Spanish

- B:

- Sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- viene.

- comes

In the Spanish verum construction, sí can be followed by que. I indicate this throughout this article by placing que in parenthesis. This should not be taken to mean that que is optional. On the contrary, the presence of que does have an effect on the interpretation of verum sentences: See Kocher (2022) who analyzes que as an expression that attributes a commitment to p to the hearer. In verum sentences this commitment attribution results in an emphatic insistence of the speaker that the hearer is (also) committed to p. In recent work, Villa-García & Rodríguez (2020a; b) argue that there are actually three constructions in Spanish that superficially look alike: There are the two verum-variants, sí que and the que-less counterpart sí ∅, which are able to co-occur with sentence negation. Additionally, there is a third construction which, according to the authors, is a bare sí that is never followed by que and that functions as a marker of emphatic affirmation. It differs from verum-sí in particular because it cannot be combined with sentence negation. The present article only deals with the former two constructions.

The theoretical aim of the present article is to corroborate Lohnstein’s sentence mood theory of verum focus and to show that it can account not only for verb-stress verum in German and English, which Lohnstein based his theory on, but also for particle verum in Spanish.

In a nutshell, the proposal is the following: Verum focus is focus on sentence mood. There is a projection in the lower section of the left periphery dedicated to sentence moods that is labeled MoodP. Focus on mood is represented by a focus feature on the mood feature. The superficial differences in the expression of verum in the three languages result from independent parametric differences that condition verb movement. In German declaratives, the finite verb reaches MoodP, so the focus feature is expressed directly as stress on the verb. In English, the lexical verb remains in VP. The sentence mood feature is inherited by TP where an auxiliary is stressed. In Spanish, neither finite lexical nor auxiliary verbs reach the left peripheral MoodP in a declarative, nor is the feature inherited by TP, therefore the particle sí is introduced in SpecMoodP where focus is then realized. Crucial evidence for my proposal comes from verum in certain non-declarative sentence types, in which the ungrammaticality of Spanish sí follows from the fact that MoodP is occupied, hindering the merger of sí.

The article is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the notion of verum. Section 2.1 marks out the empirical base. Section 3 lays out my revised version of the sentence mood theory of verum focus. Section 4 relates this theory to Rizzi (1997)’s cartographic approach. Section 4.1 deals with verb movement. In section 4.2 I present my analysis of verum focus in declaratives, and in section 4.3 I present my analysis for verum focus in interrogatives and imperatives. In section 4.4, I extend the analysis to embedded verum focused declaratives. Finally, in section 5, I conclude.

2 On verum

This section presents a descriptive approach toward what is usually meant with the term verum. It also illustrates the pragmatic felicity conditions that govern its use. The conception of verum as focus on sentence mood, that is at the core of this article, is developed in detail in section 3.

Höhle (1992) describes the meaning of verum as emphasizing the expression of truth of a proposition. An intuitive paraphrase of the verum focus strategy in (2) would therefore be ‘It is true that John is coming to the party’.

- (2)

- John is coming to the party.

- ∼ ‘It is true that John is coming to the party.’

There are certain pragmatic requirements that have to be met in order to felicitously utter a verum focused proposition. A common insight in the literature is that verum focus is only felicitous if the proposition p, and its negation not p constitute a question under discussion (cf. Ginzburg 1996; Roberts 1996; Engdahl 2006). This means that, in order to felicitously utter John is coming to the party., whether he is coming or not needs to be a question that the interlocutors are currently trying to resolve. Gutzmann et al. (2020) show that an even stronger requirement must be met: There either needs to be a conflict between salient alternatives (p or not p for a declarative) or the verum sentence needs to constitute the final settlement of a question (regarding salient alternatives). The first case is illustrated in (3). Speaker A puts the question whether p or not p on the table, which renders speaker B’s verum focus reply felicitous.

- (3)

- A: I don’t know whether John is coming to the party or not.

- B: He is coming.

The scenario of a final settling of a question is illustrated in (4). A committee of four people decide on a Mars mission that requires a unanimous vote. Only in the case when all the previous votes were positive, verum is licensed in the last vote.

- (4)

- D: Let’s vote. Should we start a Mars mission or should we not start a Mars mission?

- A: We start a Mars mission. / # We do start a Mars mission.

- B: We start a Mars mission. / # We do start a Mars mission.

- C: We start a Mars mission. / # We do start a Mars mission.

- D: Alright, we do start a Mars mission.

- (Gutzmann et al. 2020: 14: ex 34)

Conversely, verum is infelicitous in out-of-the-blue contexts like the one in (5), where whether John is coming or not is unlikely to be a question under discussion.

- (5)

- Have you heard the news? #John is coming.

Gutzmann (2012) and Gutzmann et al. (2020) furthermore show that it is actually not sufficient for the proposition and its negation to be a question under discussion, since the propositional content of the verum-sentence also needs to be given. In (6), John’s activities are introduced as a question under discussion. For the sake of the present example, consider that the set of salient activities include John’s coming to the party and his not-coming to the party. This means that whether p or not p constitutes a question under discussion in the context, but crucially, p is not given. B’s verum focus response to A’s question is infelicitous. The declarative with the same propositional content, yet without verum focus, is felicitous.

- (6)

- A: What is John doing?

- B: #He is coming.

- B’: He’s coming.

The data in (3)–(6) illustrate the English verum strategy. In (7) and (8) I show that German and Spanish verum are felicitous and infelicitous in much the same contexts. Therefore, all of them, in fact, qualify as verum strategies.

- (7)

- a.

- German

- A:

- Ich

- I

- frage

- ask

- mich,

- myself

- ob

- whether

- Hans

- Hans

- auch

- too

- zur

- to-the

- Feier

- party

- kommt.

- comes

- B:

- Er

- he

- kommt.

- comes

- ‘A: I wonder whether Hans will come to the party. B: He will come.’

- b.

- Hast

- have

- du

- you

- schon

- already

- gehört?

- heard

- #Hans

- Hans

- kommt

- comes

- zur

- to-the

- Feier.

- party

- ‘Have you heard the news? #John is coming.’

- c.

- A:

- Was

- what

- macht

- does

- Hans?

- Hans

- B:

- #Er

- he

- kommt.

- comes

- B’:

- Er

- he

- kommt.

- comes

- ‘A: What is Hans doing? B: #He is coming. B’: He’s coming.’

- (8)

- a.

- Spanish

- A:

- Me

- myself

- pregunto

- ask

- si

- whether

- Juan

- Juan

- viene

- comes

- a

- to

- la

- the

- fiesta.

- party

- B:

- Sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- viene.

- comes

- ‘A: I wonder whether Juan will come to the party. B: He will come.’

- b.

- ¿Te

- cl.2sg

- has

- have

- enterado?

- found out

- #Juan

- Juan

- sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- viene.

- comes

- ‘Have you heard the news? #John is coming.’

- c.

- A:

- ¿Qué

- what

- hace

- does

- Juan?

- Juan

- B:

- #Sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- viene.

- comes

- B’:

- Viene.

- comes

- ‘A: What is Juan doing? B: #He is coming. B’: He’s coming.’

In (7-a) and (8-a), the verum focused sentence is felicitously uttered in a context where its propositional content and its negation are given and they are questions under discussion. In (7-b), (8-b) the same sentence is infelicitous in an out-of-the-blue context. Finally, (7-c) and (8-c) show that the verum focused sentence is infelicitous when its propositional content is not given.

2.1 The empirical base

The empirical base of the present investigation are the verum strategies in Spanish, English and German illustrated in (1). The three languages also possess other strategies that can result in an interpretation similar to verum focus for instance relying on adverbs such as Englisch really, German wirklich or Spanish de verdad. For Spanish, furthermore a left peripheral use of bien (que) ‘well (that)’ (Hernanz 2007) and a syntactic fronting strategy by which not the fronted expression but the whole proposition is contrastively focused (Escandell-Vidal & Leonetti 2009a), have been described as giving rise to emphatic polarity or verum. Although a comparison of the precise meaning would certainly be interesting, these alternative strategies are not part of the empirical base of the present article. But see Kocher (2023) for a comparison of different strategies in Spanish. The reason I focus on the ones presented in (1) is that in these strategies verum focus can be shown to result from focus on sentence mood. In the other cases, the verum interpretation might arise for different reasons.

In German declaratives, verum focus is marked through prosodic stress on the finite verb (Höhle 1992; Lohnstein 2016) (cf. (9-a) and (9-b)).

- (9)

- a.

- German

- A:

- Ich

- I

- frage

- ask

- mich,

- myself

- ob

- whether

- Hans

- Hans

- auch

- too

- zur

- to-the

- Feier

- party

- kommt.

- comes

- B:

- Er

- he

- kommt.

- comes

- ‘A: I wonder whether Hans will come to the party. B: He will come.’

- b.

- A:

- Ich

- I

- frage

- ask

- mich,

- myself

- ob

- whether

- Hans

- Hans

- auch

- too

- zur

- to-the

- Feier

- party

- gekommen

- come

- ist.

- is

- B:

- Er

- He

- ist

- is

- gekommen.

- come

- ‘A: I wonder whether Hans has come to the party. B: He has come.’

Superficially, the German strategy is ambiguous: In addition to verum focus, it can also be interpreted as focus on the lexical verb, compare (9-a) to (10-a), or as focus on TAM, compare (10-b) to (9-b).

- (10)

- a.

- German

- A:

- Schlägt

- hits

- Hans

- Hans

- den

- the

- Hund?

- dog

- B:

- Nein,

- no

- er

- he

- streichelt

- pets

- ihn.

- it

- ‘A: Does Hans hit the dog? B: No, he pets it.

- b.

- A:

- Wird

- will

- Hans

- Hans

- zur

- to-the

- Feier

- party

- kommen?

- came

- B:

- Er

- he

- ist

- is

- gekommen.

- come

- ‘A: Will Hans come to the party? B: He has come.

In English declaratives, verum focus is expressed by stressing an auxiliary verb. In analytic tenses like in (11-b), the corresponding auxiliary is stressed. In synthetic tenses, the auxiliary do is inserted and stressed (11).

- (11)

- a.

- A: I wonder whether John eats meat.

- B: He does eat meat.

- b.

- A: I wonder whether John will come to the party.

- B: He has come already.

In English, only TAM focus is syncretic with verum focus. Focus on the lexical verb is expressed through stress on the verb itself (cf. the translations of (10)).

In Spanish, irrespective of whether the tense is synthetic (12-a) or analytic (12-b), the particle sí can be used to express verum focus (Batllori & Hernanz 2008; Escandell-Vidal & Leonetti 2009a, 2009b; Escandell-Vidal 2011; Kocher 2017; 2019; 2022; 2023; Villa-García & Rodríguez 2020a; b). The particle can be followed by the complementizer que. The pragmatic function of que is described in detail in Kocher (2022). Again, in this article I am only interested in the Spanish strategy that is associated with a verum meaning. A recent analysis of sí as a marker of emphatic affirmation can be found in Villa-García & Rodríguez (2020b).

- (12)

- a.

- Spanish

- A:

- Me

- myself

- pregunto

- ask

- si

- whether

- Juan

- Juan

- viene

- comes

- a

- to

- la

- the

- fiesta.

- party

- B:

- Sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- viene.

- comes

- ‘A: I wonder whether Juan will come to the party. B: He will come.’

- b.

- A:

- Me

- myself

- pregunto

- ask

- si

- whether

- Juan

- Juan

- ha

- has

- venido

- come

- a

- to

- la

- the

- fiesta.

- party

- B:

- Sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- ha

- has

- venido.

- come

- ‘A: I wonder whether Juan has come to the party. B: He has come.’

In Spanish, neither focus on the lexical verb (13-a) nor TAM focus (13-b) is syncretic with verum focus. Both are realized as stress directly on the lexical or auxiliary verb.

- (13)

- a.

- Spanish

- A:

- ¿Pega

- hits

- al

- dom-the

- perro?

- dog

- B:

- No,

- no

- lo

- it

- acaricia.

- pets

- ‘A: Does he hit the dog? B: No, he pets it.’

- b.

- A:

- ¿Llegará

- will-come

- Juan

- Juan

- a

- to

- la

- the

- fiesta?

- party

- B:

- Ha

- has

- llegado.

- come

- ‘A: Will Juan come to the party? B: He has come.’

For the present proposal, the behavior of verum focus in non-declarative clause types is of central interest. Verum focus in polar question is illustrated in (14). In English, just as in declaratives, there is stress on an auxiliary (14-a). Similarly, in German in (14-b), stress falls on the finite verb. The same happens in wh-questions: English and German, just as in a declarative, respectively stress an auxiliary (15-a) or (15-b) the finite verb.

- (14)

- A: Charles is writing a book. B: No, Charles is not writing a book.

- a.

- English

- C: So is Charles writing a book?

- b.

- German

- C:

- Was

- what

- den

- mod.part

- nun?

- now

- Schreibt

- writes

- Karl

- Karl

- ein

- a

- Buch?

- book

- c.

- Spanish

- C:

- ¿Entonces

- then

- qué?

- what

- ¿Sí

- part

- (*que)

- que

- escribe

- writes

- un

- a

- libro?

- book

- (15)

- A: Charles lives in Seville. B: That’s not true. He lives in Granada.

- a.

- English

- C: So where does Charles live?

- b.

- German

- C:

- Was

- what

- den

- mod.part

- nun?

- now

- Wo

- where

- wohnt

- lives

- Karl?

- Karl

- c.

- Spanish

- C:

- ¿Entonces

- then

- qué?

- what

- ¿Dónde

- where

- vive

- lives

- (de verdad)?

- really

- /

- #¿Dónde

- where

- sí

- part

- vive?

- lives

The case is more complex in Spanish: While sí, but not sí que, is attested in polar questions to express verum (15-c), the same is not true for Spanish wh-questions. In these, verum is either left unmarked or a lexical strategy with the adverbial de verdad is used (14-c).

The fact that sí in polar questions cannot be combined with que can be explained straightforwardly from the pragmatic function of que Kocher (2022): It is used to attribute a commitment to the proposition to the hearer. The effect of que in polar questions is that the speaker is biased to expect an affirmative answer from the hearer. In verum focused polar questions, however, there is no speaker bias. On the contrary, the speaker does not express their expectation of one answer over the other. Rather, they are confronted with incompatible information and press the interlocutors to give the true answer and possibly to support their commitment to p with further evidence.

In Spanish wh-questions, verum is not expressed by sí. It will be argued that this is due to the fact that the position sí would be merged in, is occupied by the wh-operator (see section 4.3). There are, however, cases where sí follows the wh-expression in wh-questions. These are not verum focused wh-questions. They are rather cases where a contrast is established between alternative expressions. It usually appears in a context where the same wh-expression followed by the negative particle no is given.

- (16)

- a.

- ¿Qué

- what

- sí

- part

- y

- and

- qué

- what

- no

- not

- cabe

- fits

- en

- in

- el

- the

- mundo

- world

- Kujo?

- Kujo

- ‘What does and what doesn’t fit into Kujo’s world?’ (CdE)2

- b.

- ¿Qué

- what

- no

- not

- debe

- should

- hacer

- do

- ante

- in view of

- la

- the

- picadura

- sting

- de

- of

- alacrán?

- scorpion

- [ … ]

- ¿Qué

- what

- sí

- part

- debemos

- should

- hacer

- do

- ante

- in view of

- la

- the

- picadura

- sting

- de

- of

- un

- a

- alacrán?

- scorpion

- ‘What should I not do in the case of a scorpion sting? What should we do in case of a scorpion sting?’ (CdE)

The alternatives that positively satisfy the proposition are not given in the previous context but only follow once the question has been asked. This is different from the verum-context in (15), where alternative answers are already given and the speaker presses the interlocutors to give the true answer, in other words the speaker presses the interlocutors to commit to one of the given alternatives and potentially provide support for it.

Sí (que) can also be found in echoic questions like (17) (cf. also Villa-García & Rodríguez 2020a; b).

- (17)

- Spanish

- A:

- Sí

- part

- que

- que

- viene

- comes

- Juan.

- Juan

- B:

- No

- not

- te

- cl

- he

- have

- entendido:

- understood

- ¿Quién

- who

- sí

- part

- que

- que

- viene?

- comes

- ‘A: Juan is coming. B: I haven’t understood (what you said): Who is coming?’

Finally, verum focus in imperatives is illustrated in (18). Spanish does not permit sí (que) (18-c) while German and English stress the imperative verb.

- (18)

- A: John, please grab a chair. B: (no reaction) A: Darling, would you please grab a chair? B: (no reaction)

- a.

- English

- A: grab a chair at once!

- b.

- German

- A:

- Jetzt

- now

- nimm

- grab

- dir

- yourself

- endlich

- finally

- den

- the

- Stuhl!

- chair

- c.

- Spanish

- A:

- ¡Cógete

- grab-cl

- una

- a

- silla

- chair

- de

- at

- una vez! /

- once

- *¡Sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- cógete

- grab

- una

- a

- silla

- chair

- de una vez!

- at once

This brief presentation of the empirical base shows that German and English make use of roughly the same strategy irrespective of the clause type. The case is different in Spanish: The sí (que)-strategy is only grammatical in declaratives and polar questions and ungrammatical in wh-questions and imperatives. In section 4, I review these facts again and show how they follow from the analyses I develop in this article.

3 A (revised) sentence mood theory of verum focus

The theoretical backdrop to the analyses I present in section 4 is a revised version of Lohnstein’s (2016) sentence mood theory of verum focus. Before going into the details of the theory, I would like to briefly address the terminological issue of distinguishing sentence mood and clause type. The two terms are often used interchangeably as they are closely related concepts. However, while clause types are grammatically defined classes of sentences (declarative, imperative, interrogative), sentence moods (also declarative, imperative, interrogative), according to Portner (2017), tell us how clause types are used to perform conversational functions. Clause type and sentence mood often coincide, for instance in English there are three clause types and three sentence moods. In languages that have a more finely grained mood distinction, this is however not the case (see for instance Sadock & Zwicky 1985; König & Siemund 2007). Therefore, clause type and sentence mood cannot always be identified with one another.

- (19)

- a.

- Italian

- Mi

- me

- chiedo

- ask

- se

- if

- ci

- there

- siano

- are.subj

- corsi

- courses

- d’inglese.

- of English

- ‘I wonder whether there are English courses.’ (Portner 2017: 5: ex 1)

- b.

- Ci

- there

- sono

- are

- corsi

- courses

- d’inglese?

- of English

- ‘Are there English courses?’

The clause type of the embedded sentence in (19-a) is interrogative, but its subjunctive verbal mood means that it cannot be used as a root sentence to ask a question. This means it does not have an interrogative sentence mood because it cannot perform the conversational function of an interrogative. In other words, (19-a) does not add Are there English courses? to the top of the stack of questions under discussion. Although an interlocutor might answer the embedded question (I think so., There are.), they cannot use the simple answer particles (yes/no) in this context. A felicitous context, however, would also be one where the interlocutor does not answer the embedded question at all (That would be useful.; What makes you wonder?). The clause type of the main sentence in (19-b) is interrogative because it has the grammatical properties of an Italian polar question expressed through word order and intonation. Contrary to the embedded sentence in (19-a), it also has the sentence mood of an interrogative because it can perform the dedicated conversational function of asking a question. It is added to the stack of questions under discussion and a cooperative interlocutor will do their best to resolve the question by answering it.

The approach to verum focus that is adopted here differs from most others proposed in the literature in that it does not assume that there is a verum operator responsible for the interpretation. Gutzmann (2012) and Gutzmann et al. (2020) broadly distinguish two types of analyses of verum based on their theoretical conceptions. The focus accent thesis assumes that verum is a silent operator that is always present and can be focused (Höhle 1992; Büring 2006). The lexical operator thesis assumes that verum is a conversational operator (Romero & Han 2004; Romero 2005; Lai 2012; Gutzmann & Castroviejo 2011; Gutzmann et al. 2020). The operator is only present if verum is realized and is otherwise absent. As stated above, in Lohnstein’s sentence mood theory of verum focus, no dedicated verum operator is assumed. The verum interpretation results from focus on a sentence mood feature.3

In Table 1 the central properties of prominent versions of the focus accent and the lexical operator theses are compared to the (revised) sentence mood theory of verum focus.

Comparison of the focus accent thesis by Höhle (1992) (FAT), the lexical operator thesis by Gutzmann et al. (2020) (LOT) and the (revised) sentence mood theory (SMT).

| verum meaning contributed | FAT: stressed verum operator | LOT: conversational operator | SMT: by-product of focus on mood feature |

| focus | yes | no | yes |

| in every sentence | yes | no | yes |

| non-declaratives | no | no | yes |

| embedded contexts | no | no | yes |

The central difference between the three accounts is how verum is conceptualized: In the focus accent thesis by Höhle (1992), verum is a silent predicate of truth. In the lexical operator thesis by Gutzmann et al. (2020), the meaning of the conversational operator is a type of use conditional meaning that licenses verum in a context where the speaker wants to prevent a downgrading of the current question under discussion with ¬p. In my revised sentence mood theory of verum focus, the verum meaning results from the function associated with each sentence mood. For declaratives it results in a stressed commitment to p. The three accounts take different positions with respect to focus. In the focus accent thesis and the sentence mood theory verum is focus, in the lexical operator thesis it is not. The accounts furthermore differ in their assumptions about the presence of the operator. In the focus accent thesis a verum operator is present in every sentence. The verum meaning arises when this operator is focused. In the lexical operator thesis, not every sentence contains a verum operator. The operator is only present when verum is realized. In the sentence mood theory verum is a result of focus on a sentence mood feature. The feature is present in every sentence, however, it does not have a dedicated verum meaning. The verum effect is a by-product. Finally, the accounts differ in their empirical base. While the focus accent and lexical operator theses draw their evidence from verum in declaratives, the sentence mood theory of verum focus has the advantage of broader empirical coverage. Cases of verum in interrogatives, imperatives and embedded contexts are mentioned in Höhle (1992) and Gutzmann et al. (2020), but neither of them can straightforwardly explain the pragmatic effect of verum in non-declarative sentences, nor do they account for the syntactic restrictions of verum focus in different clause types and in embedded contexts. In turn, as will become clear shortly, these empirical data are at the center of the sentence mood theory of verum focus.

Although I argue in favor of the sentence mood theory of verum focus, I want to emphasize again that I maintain that focus on sentence mood might be only one way to achieve a verum effect. In principle, the different conceptions of verum I sketched above can co-exist and can each be best equipped to account for a subset of empirical phenomena. See also Gutzmann et al. (2020) and Lohnstein (2016) for a deeper comparison of the different accounts.

For my account, I adopt Lohnstein’s core assumptions: I thus consider verum meaning to result from focus on sentence mood and focus, in the sense of Krifka (2008), to function to reduce alternatives. I also adopt the assumption that the relevant salient alternatives when sentence mood is focused are derived from the function of the speech act, i.e. the corresponding clause type in a discourse situation.4 In my revised version of the theory, the functions of the sentence moods are different from the original version. Lohnstein’s theory is built on a mental conception of commitments. In recent speech-act theory, however, the social obligations that are involved in commitments are granted more importance than mental attitudes or judgments. My revision thus constitutes a reformulation of the functions as commitments in this sense. By revising the theory in this way, it is not only brought in accordance with the newest insights from research on speech acts, it also solves an issue of overgeneralization the original theory faces: According to Lohnstein (2016), the function of a declarative is to express a belief. Thus, the relevant alternatives that are focused are believe p and not believe p. A problem that follows from this definition is that it wrongly predicts that a verum focused declarative is felicitous in a context where whether or not the interlocutors believe p is under discussion.5

- (20)

- A: I am so unsure. Will Mary come to the party? Jane believes that she will come. What do you believe?

- B: #Mary WILL come to the party, even though there is a big chance that she will not come.

As stated above, I adopt a social rather than a mental conception of commitment. In previous theories, a commitment to a proposition translated to believing that the proposition is true. In more recent theories, this conception is given up in favor of social norms (cf. Brandom 1983; 1994; 2000 Kibble 2006a; b; Geurts 2019; Shapiro 2020, among others). Proponents of this new conception of commitment propose that what is important for asserting a proposition is not so much whether or not the speaker believes p, but the social obligations towards the interlocutors that arise. In line with Brandom (1983; 1994; 2000), I assume that by asserting p a speaker expresses their commitment towards p. Expressing a commitment consists of two parts: The first part, which is important in the present context, is the responsibility to justify p. A speaker takes up a responsibility to show that they are entitled to the commitment, in other words that they are required to defend p if challenged or if unable, to retract their assertion of p (a similar idea can be found in Kibble 2006b). The second part is the authority over p. The speaker authorizes further assertions and the commitments they express. These can either be inferential or communicational, in the sense that a hearer, when challenged for their assertion of p, can pass justificational responsibility to the original asserter of p (cf. also Shapiro 2020).

The expression of a belief of p still plays a role in assertions, since speakers take up a commitment to p, meaning they take up responsibility to justify it and license further assertions, mostly in cases when they believe that p is true. A belief of p, however, is not a precondition for expressing a commitment to p. There are examples when a belief of p on the part of the speaker is not relevant. Geurts (2019) discusses cases of performative speech acts.

- (21)

- I find the defendant guilty of armed robbery. (Geurts 2019: 14: ex7)

When (21) is uttered by a judge it does not really matter whether or not they privately believes that the defendant is guilty. What is important is that the judge is committed to act on p, meaning in accordance with the truth of p.

An anonymous reviewer suggested that the mental conception presented in Lohnstein (2016) could still be maintained by adopting Frege’s notion of judgment which is defined as an attitude towards p. For declaratives the attitude is either a belief of p or it is unmarked. Associating assertions with an unmarked judgment is very close to what I have in mind here. By separating belief from assertion, it allows us to maintain that a belief of p does not have to be a precondition to assert p, i.e. commit to it in my sense. This makes it possible to deal with cases like (21) and to also treat propositions that express doubt or low epistemic certainty as assertions. Finally, the conception of an unmarked judgment makes it possible to assume that the order of belief and assertion can be inverted: By asserting p the speaker commits to it and (the ascription of a) belief of p might come about by way of an inference. This brief discussion goes to show that Frege’s judgment is, in principle, compatible with the theory I develop here. However, the social conception of commitment is still better suited to account for verum. If we assumed that verum focus were stressing a judgment in Frege’s sense, we would be faced with two problems: If the judgment is a belief of p, the focus alternatives are the same that Lohnstein (2016) proposed, namely believe p and not believe p, provoking the issue of overgeneralization discussed around example (20). If, in turn, the judgment is unmarked, it is not clear what the focus alternatives would constitute. I therefore stand with my choice to think of commitments in social rather than mental terms.

Based on the reconception of commitments, I propose to redefine the functions of the sentence moods and their verum focused alternatives as summarized in Table 2.

Sentence Moods with their corresponding functions and verum focused alternatives in the new conception.

| sentence mood | function | alternatives |

| declarative | committed to p | committed to p,not committed p |

| polar interrogative | make hearer expresscommitment to p, not p | hearers’ commitment to p,hearers’ commitment to not p |

| wh-interrogative | make hearer express commitment to one of n alternative answers | hearers’ commitment to one of n alternative answers |

| imperative | make hearer behave inaccordance with commitment to p | n alternative behaviors |

The function of a declarative related to the assertive illocutionary force, is to express a commitment towards p.

- (22)

- A: I don’t know whether John will come to the party or not.

- B: He will come.

In (22), speaker A establishes whether John will come to the party as a question under discussion by putting the two alternatives on the table. Speaker B uses verum focus to reduce the alternatives so that only the alternative “John will come”, which corresponds to the alternative B is committed to, is presented as true (cf. Lohnstein 2016: 17–18). By stressing their commitment, speaker B emphasizes that they takes up the responsibility to justify p.

Directives, such as questions and commands, are different from assertions. They do not commit the speakers to p, but rather they commit them to a goal that can usually only be realized by the addressee (Geurts 2019). The discourse function of polar questions has traditionally been said to be giving a true answer out of two possible alternatives (cf. for instance Karttunen 1977; Groenendijk & Stokhof 1985). In my conception, their function is to make an addressee express their commitment towards one of the two possible alternatives. This is the goal the speaker commits to. The speaker who utters the polar question is not in a position to judge whether the proposition expressed is true or false. In the present system, the effect of verum focus in a polar question is to demand that the addressee(s) justify their (previously expressed) commitment to p or not p in fulfillment of the function of the sentence mood.

- (23)

- A: Charles is writing a book.

- B: No, Charles is not writing a book.

- C: So is Charles writing a book?

- (translation of Gutzmann 2012: 31: ex 91)

In (23), speaker C, who utters the verum focused polar question, does not know whether Charles is writing a book or not. The alternatives provided by speaker A and B are contradictory. In a discourse situation, like the one sketched in (23), verum focused polar questions are often used to put an end to a discussion. The effect of verum in this context is that speaker C presses speakers A and B to justify their commitment. Speaker C would not be satisfied if speakers A and B merely restated their commitments without further justification. In fact, by using verum focus, speaker C calls them out to take up the responsibility to defend p or not p by providing evidence in favor.

- (24)

- A: He is, he sent me a draft.

- B: What he sent you is not his draft but John’s. Charles pretends he wrote it. John told me all about it.

A possible continuation to the conversation in (23) could be (24), where speaker A and B each present a justification for why they are committed to either p or not p.

The function of a wh-question is to make a hearer commit to one of n possible alternatives.6 Once again, the speaker who utters the verum focused wh-question does not know the true answer. Verum focus is used to stress the function of the mood of wh-questions and demand the true answer from the addressee(s).

- (25)

- A: Charles lives in Seville.

- B: That’s not true. He lives in Granada.

- C: So where does Charles live?

In (25), speaker C does not know where Charles lives. A and B propose contradicting alternatives, which do not help C in finding the true answer. Speaker C wants to settle the discussion, the effect of verum focusing the wh-question is that speaker C presses their interlocutors to provide justification for their expressed commitment. Speaker C requires more than just a repetition of the interlocutors’ commitments to find the true answer. Speaker C asks them to give their reasons and defend their commitment. A possible continuation of (25) is given in (26).

- (26)

- A: Well, I assumed it was Seville when he told me he lived in big city in Andalusia, but actually he never mentioned the name of the city.

- B: Yeah, he meant Granada. I visited him there last month.

Finally, with imperatives the speaker is again committed to a goal that only the addressee can realize. Their function is to make the hearer behave in accordance with the truth of p, in other words, make the addressee do whatever the corresponding proposition expresses. Imperatives do not have truth values so there are no propositional alternatives that can be focused. I adopt the idea from Lohnstein (2016) that the relevant alternatives are the possible alternative behaviors of the addressee. A verum focused imperative, therefore, seeks to reduce the addressee’s behavior to the one expressed by the imperative.

- (27)

- A: John, please grab a chair.

- B: (no reaction)

- A: Darling, would you please grab a chair?

- B: (no reaction)

- A: grab a chair at once! (translation of Gutzmann 2012: 31: ex 93)

In (27), the speaker makes use of verum focus in order to put an end to the addressee’s lack of reaction or hesitation by demanding that they fulfill the action expressed by the imperative.

The revised sentence mood theory of verum focus can also explain the other pragmatic properties of verum focused sentences. The infelicitousness of verum in out-of-the-blue contexts in (28-a) (repeated from (5)) or as answers to general questions in (28-b) (repeated from (6)) follows straight forwardly in this theory. Verum is considered a type of focus, thus the relevant focus alternatives need to be salient. This condition is not met in an out-of-the-blue or general-question context.

- (28)

- a.

- Have you heard the news? #John is coming.

- b.

- A: What is John doing?

- B: #He is coming.

- B’: He’s coming.

The licensing of verum in a final settling of a questions can also be explained. The verum effect in declaratives, in the present theory, results from stressing the comittment to p. Thereby a speaker stresses that they are in a place to justify and defend p. In turn, this means that verum is not going to be used, if a speaker cannot or does not want to take up this responsibility.

- (29)

- D: Let’s vote. Should we start a Mars mission or should we not start a Mars mission?

- A: We start a Mars mission. / # We do start a Mars mission.

- B: We start a Mars mission. / # We do start a Mars mission.

- C: We start a Mars mission. / # We do start a Mars mission.

- D: Alright, we do start a Mars mission.

- (Gutzmann et al. 2020: 14: ex 34)

In the example in (29) (repeated from (4)), when asked for a vote, A, B and C express a preference. They are actually not asked to commit to the Mars mission taking place, but to state what they think is best. They all vote in favor, which means that they commit to act on p, meaning to act in accordance with the truth of p, should all involved parties take up the commitment. In fact, since a unanimous vote is required, neither A, B nor C are in a place to commit to the Mars mission taking place. D, contrary to A, B and C, does not state their preferences, they stress their commitment to p. Only speaker D is in a position to commit to p and even to stress their commitment, because all four parties voted in favor and therefore speaker D can justify the joint commitment.

4 The syntax of verum focus

The sentence mood theory of verum focus functions as a conceptual backdrop to the syntactic analyses that I develop in the following sections. The analyses are formulated within a cartographic framework. The approach is based on the idea that the left periphery of a clause is split into a number of hierarchically ordered functional projections mediating the interface between syntax, pragmatics and information structure. In accordance with Lohnstein (2016), I assume that the left periphery contains a projection dedicated to sentence mood termed (sentence) MoodP. In previous syntactic analyses of verum focus and similar polarity related phenomena, it has often been proposed that there is a projection in the same area of the left periphery dedicated to polarity (see Laka 1990; Martins 2006; Hernanz 2007; Batllori & Hernanz 2008; Rodríguez Molina 2014; Villa-García & Rodríguez 2020b). Since the present analysis is grounded in the idea that the interpretive effect of verum results from focusing sentence mood, a dedicated projection for verum becomes obsolete.

The structure in (30) gives the full extension of the functional heads proposed by Rizzi with the addition of the proposed MoodP in the lower section of the left periphery and SubP as the highest projection.

- (30)

- [ SubP [ TopP [ IntP [ TopP [ FocP [ ModP [ TopP [ MoodP [ TopP [ FinP [ TP]]]]]]]]]]]

- (Rizzi 1997; 2001; 2004; 2013; Lohnstein 2016; Kocher 2022)

A position dedicated to clause typing was part of the original structure developed in Rizzi (1997) as the highest projection, ForceP. In more recent analyses, ForceP, or decompositions thereof, has been re-purposed as projections mediating the link between clause types and illocutionary force and also other aspect of pragmatics (Coniglio & Zegrean 2010; Corr 2016; Speas & Tenny 2003). While the line of research concerned with the syntactic representation of pragmatics is certainly interesting, it has also met criticism (cf. for instance Gärtner & Steinbach 2006; Kocher 2022). I take a more cautious approach here, since I believe that the principles that govern pragmatics are to a large part inherent to this area of grammar and are therefore difficult to map onto syntactic structure and mechanisms. In accordance with Haegeman (2006) and Kocher (2022), I assume that the highest functional head in the left periphery is associated with a traditionally syntactic function, namely that of clausal subordination. The projection is accordingly labeled SubP in the structure in (30). Motivation and discussion can be found in Haegeman (2006) and Kocher (2022).

While Rizzi placed the original clause typing projection ForceP at the top left edge of the periphery, MoodP is placed in the lower right area of the functional field. I adopt this position because new evidence has shown that clause typing shows reflexes lower in the left periphery. Notably, Haegeman (2004; 2006) independently proposed a restructured left periphery, with a projection responsible for clause typing (named ForceP in her proposal) coinciding with the position I assume for MoodP. See Kocher (2022) for further empirical evidence for the precise position of MoodP within the functional field.

Versions of the cartographic approach have been widely adopted to account for word order in Romance languages. It is a particularly useful tool to analyze languages of this family because they exhibit a rich left peripheral structure, providing solid motivation for an extensive functional field like the one in (30). Other languages, however, seem to make do with a less elaborate structure. A conclusion one can draw from these differences is that not all languages project all heads of the functional field. There also appear to be language-internal differences with respect to whether all heads are projected in certain clause types or configurations. Haegeman (2004; 2006) notes differences in size between various adverbial clauses. de Cuba & MacDonald (2013) discuss differences in size between factive and non-factive complements. Concerning the languages at the center of the present article, empirical facts suggests that Romance CPs are larger than Germanic CPs (cf. Roberts 2001). Although the precise size and structure of the German and English CP will not be mapped out here, the contrast between (31) and (32) illustrate that there is in fact a difference in the availability of structural positions. The examples in (31) show that a left dislocated topic is grammatical in a main declarative in all three languages.7

- (31)

- a.

- English

- A: Who brought the beer and the wine? B: The beer I brought, the wine’s Mary’s.

- b.

- German

- A:

- Wer

- who

- hat

- has

- das

- the

- Bier

- beer

- und

- and

- den

- the

- Wein

- wine

- mitgebracht?

- brought

- B:

- Das

- the

- Bier

- beer

- hab

- have

- ich

- I

- mitgebracht.

- brought

- Der

- The

- Wein

- wine

- ist

- is

- von

- from

- Maria.

- Maria

- c.

- Spanish

- A:

- ¿Quién

- who

- ha

- has

- traído

- brought

- la

- the

- cerveza

- beer

- y

- and

- el

- the

- vino?

- wine

- B:

- La

- the

- cerveza

- beer

- la

- cl.fsg

- he

- have

- traído

- brought

- yo,

- I

- el

- the

- vino

- wine

- es

- is

- de

- from

- María.

- María

The facts are different in embedded contexts: While Spanish and English permit a topic below the complementizer (32-a), (32-c), the same word order is ungrammatical in German (32-b) (but see section 4.4 for a closer look into this issue).

- (32)

- a.

- English

- John said that the beer, he has brought.

- b.

- German

- *Hans

- Hans

- hat

- has

- gesagt,

- said

- dass

- that

- das

- the

- Bier

- beer

- er

- he

- mitgebracht

- brought

- hat.

- has

- c.

- Spanish

- Juan

- Juan

- dijo

- said

- que

- that

- la

- the

- cerveza

- beer

- la

- cl.fsg

- ha

- has

- traído.

- brought

While the precise architecture of the functional field in each of the languages is left to be determined in future research, these contrasts support the assumption that the German left periphery is more reduced than the Spanish and English one.

4.1 Parametic differences in verb movement

It has been observed in the literature that there are parametric differences in the position a verb reaches in German, English and Romance declaratives (cf. Emonds 1976; Belletti 1990; Williams 1994; den Besten 1983; Suñer 1994; Benedicto 1998; Ordóñez 1998; Toribio 2000; Roberts 2001, Goodall 2002; Zagona 2002; Truckenbrodt 2006; Schifano 2018). The examples in (33)–(34) illustrate this by comparing the word order of finite verbs and functional adverbs in the three languages. The diagnostic employed here goes back to Emonds (1976) and Pollock (1989) and is based on the assumption that the position of the adverbs in the periphery of the VP is fixed cross-linguistically (for a proposal of a universal hierarchy of modifiers see Cinque 1999). The contrast between (33-a) and (33-b) shows that in English, the finite verb follows the VP adverb and cannot precede it. This has been taken to suggest that the verb remains in V0.

- (33)

- a.

- John often [V0 kisses] Mary.

- (Pollock 1989: 367: 4c, analysis by myself)

- b.

- *John kisses often Mary.

- (Pollock 1989: 367: 4c)

In Spanish, the opposite pattern emerges. The only grammatical order is the one where the finite verb precedes the VP adverb in (34-b). The reverse order is ungrammatical (34-a). This indicates that the verb moves to T0 in Spanish.

- (34)

- a.

- Spanish

- *Juan

- Juan

- frecuentemente

- often

- besa

- kisses

- a

- dom

- María.

- María

- b.

- Juan

- Juan

- [T0

- besa]

- kisses

- frecuentemente

- often

- a

- dom

- María

- María

- [V0 t].

- (Lorenzo González 1995: 28: ex 20d, analysis by myself)

German superficially shows the same pattern as Spanish: The order where the VP adverb precedes the verb in (35-a) is ungrammatical and the order where the VP adverb follows the verb in (35-b) is grammatical. The example in (35-c) illustrates that German is a V2 language. The word order restrictions show that in a declarative the finite verb necessarily occupies the second position of the sentence. It is assumed for German that the finite verbs moves even higher than TP to a position in the CP. In line with Lohnstein (2016), I identify this projection with Mood0.

- (35)

- a.

- German

- *Hans

- Hans

- oft

- often

- küsst

- kisses

- Maria.

- Maria

- b.

- Hans [Mood0

- Hans

- küsst]

- kisses

- Maria

- Maria

- oft

- often

- [V0 t].

- c.

- In letzter Zeit

- lately

- (*Hans)

- Hans

- (*oft) [Mood0

- often

- küsst]

- kisses

- (*oft)

- often

- Hans

- Hans

- Maria

- Maria

- (oft).

- often

- ‘Lately, Hans often kisses Maria.’

The core argument of this section is that the projection hosting the mood feature is occupied by different material in the various sentence moods and languages. The variation we observe is the result of the fact that focus on mood, giving rise to verum, is expressed on different things. This section presents a formalization of the empirical data from Spanish, German and English relying on existing accounts on verbal movement and feature inheritance. The aim is not to develop a new theoretical motivation for verbal movement, rather the more modest goal is to systematize the empirical data and find a formal way to describe them. I am fully aware that further research is pending to motivate certain aspects of the analysis.

There are various options to model head movement and its triggering factors. A comprehensive overview of the main conceptual alternatives and their merits can be found in Dékány (2018). For the present analyses, I adopt the reprojection approach developed in Biberauer & Roberts (2010) and Roberts (2010). In this account complex heads are externally merged in their inflected forms. Certain formal features on these complex heads require to be checked in a structurally higher position. This provokes movement of the head out of its position and internal merge of it as the sister of the previous phrase. The moved head projects the label of the new syntactic phrase. Biberauer & Roberts (2010) propose that in Romance varieties that have rich tense inflection such as Spanish, the finite verb carries a tense feature that provokes reprojection of a TP. In English, the verb lacks rich tense inflection and its unvalued tense feature cannot project. Head movement from V-to-T does not take place. The tense feature on the verb is valued through agree, which in their accounts is defined as a mechanism that copies feature values from a probe, T in our case, to a c-commanded goal, V, with a matching unvalued feature. Biberauer & Roberts (2010) argue that there is agreement between T and V even in cases when T is filled by an auxiliary. This is based on the data in (36) which show that the verb in V is non-finite.

- (36)

- a.

- John has eaten

- b.

- John is eating

- c.

- John was eaten

- d.

- John must eat-∅

- e.

- For John to eat-∅-… (Biberauer & Roberts 2010: 270: ex 6)

In German, a V2 language that also lacks rich tense inflection, the finite verb surfaces in a C-position. Just as in English, German’s poor tense inflection means that V does not carry a tense feature. Reprojection of TP and V-to-T movement do not take place. Instead, according to Biberauer & Roberts (2010) the German verb does not pass through T but moves directly to a C-position. This contrasts with English and Spanish declaratives, where the verb does not reach a C-position. It reprojects T in Spanish, and remains in V in English.8

A second central ingredient to analyze the parametric differences in verb positions is Ouali’s system of feature inheritance. He distinguishes between three logical options of how features can be inherited by a head: keep (the head retains the features), share (the head copies features to another head) and donate (the head passes features to another head without keeping a copy). Biberauer & Roberts 2010 propose C donates φ- and tense features to T in Romance and English and keeps them in German.

In order to formalize my ideas within this system, I have to add some additional assumptions. I am of course aware that some of these assumptions are in need of more empirical proof. As I stated at the beginning of this section, as a first step, the goal is to find a formal description relying on existing tools from the theoretical literature. More elaboration and proof should follow in the future.

With this caveat in place, I make the following assumptions: I assume that there is a third important feature involved, namely mood. I also assume that the C-head in Biberauer & Roberts (2010) and Ouali (2008) can be identified with Mood. I furthermore assume that it is possible to donate only a subset of the features and keep the rest. This possibility has also been explored in Biberauer & Roberts (2010: 291–293) for Welsh. Finally, I assume that feature inherence can differ between clause types. What I propose for German, English and Spanish is presented in Table 3, leaving out φ features for simplicity.

Feature inherence between Mood and T in German, Spanish and English.

| declarative | interrogative | imperative | |

| German | keeps tense, mood | keeps tense, mood | keeps tense, mood |

| English | donates tense, mood | keeps tense, mood | donates tense, mood |

| Spanish | keeps mood, donates tense | keeps mood donates tense | keeps tense, mood |

In the present approach, every clause contains a mood feature (in MoodP). This picks up a traditional idea maintained in the literature (cf. for instance Baker 1970; Rizzi 1990; Cheng 1991; Rivero & Terzi 1995, Han 1998). The alternative view, that clauses are not typed by an abstract feature but through a combination of grammatical properties is maintained for instance by Altmann (1987),Brandt et al. (1992); Lohnstein (2000); Truckenbrodt (2006); Sode & Truckenbrodt (2018). It is also a prominent position in construction grammar (cf. Michaelis & Lambrecht 1996; Kathol 2000; Ginzburg & Sag 2000).

There are differences across languages and across clause types in terms of whether the mood feature is kept in Mood or donated to T. In all German clause types, Mood keeps the mood and tense feature, triggering movement of the finite verb to this position. In English declaratives and imperatives, the sentence mood features along with the tense features are donated to T. In declaratives, T agrees with V and values its unvalued features. In imperatives, the finite verbs moves to T. In English interrogatives, in contrast, Mood keeps the mood and tense feature and the finite verb moves there. In Spanish, Mood keeps the sentence mood feature in all clause types. In imperatives the tense feature is also kept by Mood resulting in head movement of the finite verb to this position. In Spanish declaratives and interrogatives, however, the tense feature is donated to T where the finite verb moves and is valued with its tense feature. Altogether, these patterns support the argument presented in Biberauer & Roberts (2010) that head movement is triggered by tense rather than φ (or mood) features. Building on the typology in Table 3, in the following sections I show how verum focused declaratives (4.2), imperative and interrogatives (4.3) are derived.

The mood feature is different from the tense feature, whose behavior and inheritance, according to Biberauer & Roberts (2010) has to do the richness and poverty of the tense morphology of a given language. None of the three languages have a distinct morphological form for the different sentence moods declaratives, interrogatives and imperatives. Only imperatives are distinguished morphologically. The mood feature impacts the structural properties that are used to encode the sentence moods. Therefore, rightly, English declaratives and interrogatives have a different configuration since their structural properties are in fact very different.

4.2 Analysis of verum focused declaratives

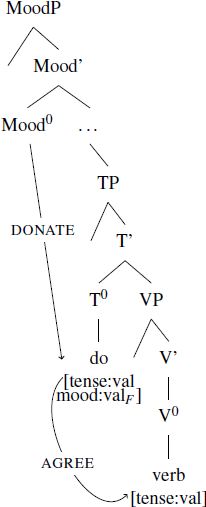

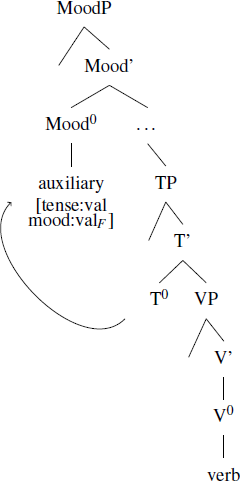

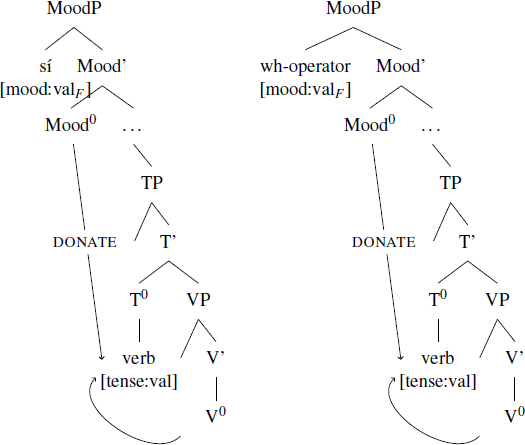

For verum focus in declaratives I propose the following analyses. In German, Mood keeps the tense and the mood feature and attracts the verb to this position. Focus on mood is expressed through prosodic stress on the finite verb. A simplified scheme of the derivation is found in (37).

- (37)

In synthetic tenses the finite verb moves from V to Mood (cf. Biberauer & Roberts 2010), in analytic tenses the auxiliary moves from T to Mood. The mood and tense feature are valued in Mood. As explained at length in the previous sections, I take verum to result from focus on the sentence mood feature. Thus, if the feature is focused it is realized as prosodic stress on whatever checks the mood feature, which is a lexical verb in (38-a) and an auxiliary in (38-b).9

- (38)

- a.

- [MoodP Hansi [Mood’ [Mood0 KOMMTj[mood:val_F, tense: val]] [… [VP ti [V’ [V0 tj ]]]]]]

- b.

- [MoodP Hansi [Mood’ [Mood0 ISTj[mood:val_F, tense: val]] ] [… [TP ti [T’ [VP ti [V’ [V0 gekommen ]]] [T0 tj ] ]]]]

In English, Mood donates tense and mood features to T. The finite lexical verb remains in the VP. Its unvalued features are valued via agree between T and V.

- (39)

In analytic tenses, an auxiliary is merged in TP where focus on mood is expressed through stress on this auxiliary. In synthetic tenses, ‘do’ is merged in T triggered by the focus feature on mood. Biberauer & Roberts (2010: 272), despite not using the term verum, suggests that English overt do is triggered by an additional feature they call [+ Affect] that results in a special discourse effect. I propose what they call [+ Affect] is in fact a focused mood feature.

- (40)

- a.

- [MoodP [Mood’ [Mood0 ] [… [TP Johni [T’ [T0 does[mood:val_F, tense: val] ] [VP ti [V’ [V0 come[tense: val] ]]]]]]]]

- b.

- [MoodP [Mood’ [Mood0 ] [… [TP Johni [T’ [T0 hasj[mood:val_F, tense: val]] [VP ti [V’ [V0 come[tense: val] ]]]]]]]]

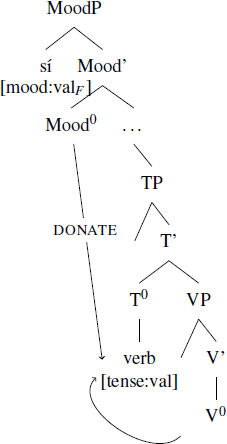

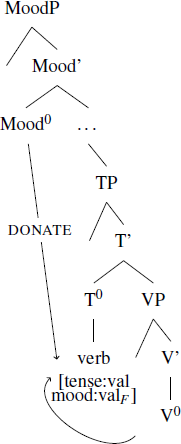

In Spanish declaratives, tense (and φ) features are donated to T, but mood features are kept in Mood. The Spanish finite verb moves from V to T in synthetic tenses and is merged directly in T in analytic tenses. Crucially it does not move beyond this position. The particle sí is merged directly in the specifier of MoodP.

- (41)

- (42)

- a.

- [TopP Juani [Top’ [Top0 ] [MoodP sí[mood:val_F] [Mood’ [Mood0 ] [… [TP ti [T’ [T0 vienej[tense:val] ] [VP ti [V’ [V0 tj ]]]]]]]]]]

- b.

- [TopP Juani [Top’ [Top0 ] [MoodP sí[mood:val_F] [Mood’ [Mood0 ] [… [TP ti [T’ [T0 ha[tense:val] ] [VP ti [V’ [V0 venido ]]]]]]]]]]

There are reasons to believe that Spanish developed the particle-based strategy because of a restriction on the verb movement, offering further support for the underlying relation between the Spanish particle based and German and English verb-based verum strategies. The empirical point in favor is the fact that the first attestation of sí (que) coincides with the loss of V2 in Old Spanish (cf. Fontana 1993 on Old Spanish V2, and Rodríguez Molina 2014 and Kocher 2017 on the history of sí que). In other words, the need to merge sí in MoodP to check the focus feature only arose after verb movement to the left periphery was no longer available. A link between the emergence of the particle and the loss of V2 also extends to other Romance varieties: Ledgeway (2008) proposes that Old Neapolitan sí was merged in the CP to satisfy a V2 requirement. In the context of the present argumentation, the loss of V2 in Old Spanish might constitute the parametric shift between a system akin to the one we find in modern German where tense features triggering head movement are kept by Mood and the system of modern Spanish where these tense features are donated to T.10

To summarize, the analyses I propose for verum focused declaratives boil down to the following: German Mood keeps tense and mood features, which triggers head movement of the verb to this position. The focus feature, which gives rise to the verum interpretation, is expressed on the element that carries the mood feature, i.e. the finite verb. In English declaratives tense and mood features are donated to T. Focus is realized as prosodic stress and needs lexical material to be expressed on. This is why, in the absence of an auxiliary required by the tense, ‘do’ is inserted in T. In Spanish declaratives there is no movement of the finite verb to Mood either. While the tense feature is donated to T, the mood feature remains in Mood in this clause type. The focus feature on mood in MoodP triggers the merger of sí in the specifier of MoodP.

4.3 Analysis of verum focused interrogatives and imperatives

In the present section, I look at the strategies the three languages use to express verum focus in non-declarative clause types and show how I account for them. This section provides crucial evidence for the link between verum focus and sentence mood. The interesting empirical observation is that German and English use a similar strategy as in declaractives, while in Spanish the sí (que) strategy is not available in imperatives and wh-interrogatives.

Verum focus in polar questions, as illustrated in section (18), is a device to press the interlocutor to provide a true answer out of the two salient alternatives. Similarly, verum focus in wh-questions is used as a means to press the interlocutor for a true answer out of n salient alternatives. German employs the same strategy in wh- (43-a) and polar questions (43-b) as in declaratives: It stresses the finite verb.

- (43)

- a.

- German

- A:

- Karl

- Karl

- wohnt

- lives

- in

- in

- Sevilla.

- Sevilla

- B:

- Das

- that

- stimmt

- be-right

- doch

- mod.part

- gar

- at all

- nicht.

- not

- Er

- he

- wohnt

- lives

- in

- in

- Granada.

- Granada

- C:

- Was

- what

- denn

- mod.part

- nun?

- now

- Wo

- where

- wohnt

- lives

- Karl?

- Karl

- b.

- A:

- Karl

- Karl

- schreibt

- writes

- ein

- a

- Buch.

- book

- B:

- Nein,

- no

- Karl

- Karl

- schreibt

- writes

- kein

- no

- Buch.

- book

- C:

- Was

- what

- denn

- mod.part

- nun?

- now

- Schreibt

- writes

- Karl

- Karl

- ein

- a

- Buch?

- book

- ‘A: Karl is writing a book. B: No, Karl isn’t writing a book. C: Tell me now: is Karl writing a book?’ (Gutzmann 2012: 31, ex 91)

In English verum focused interrogatives, just as in declaratives, there is stress on do in synthetic tenses and on the auxiliary in analytic tenses (cf. (44) repeated from (23) and (45-a) repeated from (25)).

- (44)

- A: Charles is writing a book.

- B: No, Charles is not writing a book.

- C: So is Charles writing a book?

Notably, do is also present in subject questions that do not require the auxiliary in a neutral, non-verum focused context (Who lives in Seville?) (cf. (45-b)). In my proposal, this is expected because, just as in declaratives, do is triggered by a focus feature on mood.

- (45a)

- a.

- A: Charles lives in Seville.

- B: That’s not true. He lives in Granada.

- C: So where does Charles live?

- b.

- A: Charles lives in Seville.

- B: That’s not true. John lives there.

- C: So who does live in Seville?

In Spanish polar questions, verum can be expressed with the particle sí but not with sí que (cf. (46-a)). As has been explained in section 2.1, this is because que is used in polar questions to express a speaker bias, which is not compatible with the effect of verum in polar questions. In the contexts that elicit a verum interpretation of a wh-question, speakers resort to lexical strategies, employing for instance the adverbial de verdad ‘really’ (46-b).11

- (46)

- a.

- Spanish

- A:

- Carlos

- Carlos

- escribe

- writes

- un

- a

- libro.

- book

- B:

- Que

- que

- no!

- no

- Carlos

- Carlos

- no

- not

- escribe

- writes

- ningún

- no

- libro.

- book

- C:

- ¿Entonces

- then

- qué?

- what

- ¿Sí

- part

- (*que)

- que

- escribe

- writes

- un

- a

- libro?

- book

- b.

- A:

- Carlos

- Carlos

- vive

- lives

- en

- in

- Sevilla.

- Seville

- B:

- No

- not

- es

- is

- verdad:

- truth

- Vive

- lives

- en

- in

- Granada.

- Granada

- C:

- ¿Entonces

- then

- qué?

- what

- ¿Dónde

- where

- vive

- lives

- (de verdad)? /

- really

- #¿Dónde

- where

- sí

- part

- vive?

- lives

Imperatives express the speaker’s demand to make the propositional content of the imperative a fact. Verum focus in imperatives is licensed when the speaker insists on their demand that the addressee should do whatever the proposition expresses and rejects an alternative behavior, defined as any salient behavior that differs from the one requested by the speaker. In contexts like these, German once again stresses the finite verb (47).

- (47)

- German

- Jan,

- Jan

- bitte,

- please

- nimm

- grab

- den

- a

- Stuhl.

- chair

- (no reaction)

- Liebling,

- darling

- würdest

- would

- du

- you

- dir

- yourself

- bitte

- please

- den

- the

- Stuhl

- chair

- nehmen?

- grab

- (no reaction)

- Jetzt

- now

- nimm

- grab

- dir

- yourself

- endlich

- finally

- den

- the

- Stuhl!

- chair

In the parallel context in English, there is also stress on the finite imperative verb ((48) repeated from (27)). So in English verum focused imperatives, different from what we find in declaratives or interrogatives, do is not inserted.

- (48)

- John, please grab a chair. (no reaction) Darling would you please grab a chair? (no reaction) grab a chair at once!

There is another version of an English imperative featuring do. It is however not licensed in a context such as that illustrated in (48). It typically appears in contexts where the addressee is hesitant about which behavior is required of him or when the speaker wants to signal politeness. The contexts also differ from those that elicit verum focus in that the proposition does not have to be given.

- (49)

- [Winston Churchill at his first audience with the new queen Elisabeth II unsure about the etiquette required by the occasion:]

- Queen: Do sit down, Prime Minister. [The Crown 2016 S01E03 – Windsor]

In Spanish imperatives, just as in wh-questions, sí (que) is not an option (50).12

- (50)

- Spanish

- Juan,

- Juan

- por favor,

- please

- cógete

- grab-cl

- una

- a

- silla.

- chair

- (no reaction)

- Cariño,

- darling

- ¿te

- cl

- podrías

- could

- coger

- grab

- una

- a

- silla?

- chair

- (no reaction)

- ¡Cógete

- grab-cl

- una

- a

- silla

- chair

- de

- at

- una

- once

- vez! /

- *¡Sí

- part

- (que)

- que

- cógete

- grab

- una

- a

- silla

- chair

- de

- at

- una vez!

- once

The empirical facts outlined above are compatible with the following analyses of verum focus in non-declarative clause types. In German, it appears that in all unembedded sentences irrespective of their clause type, the finite verb moves to Mood where the focus feature is expressed. In my account, this means that Mood keeps all relevant features in all clause types in German, so the structure in (38) also holds true for interrogatives and imperative.

In English interrogatives there is movement of the auxiliary from T to Mood. This means that the verb moves to a higher position than in a declarative. This high structural position of the auxiliary in English questions finds support in the fact that (neutral) polar questions are verb initial (51-a)13 and wh-questions (51-b) do not permit an intervening subject between the wh-pronoun and the verb. Neither would be expected if the auxiliary remained in T.

- (51)

- a.

- *Charles does live in Seville?

- b.

- *Where Charles does live?

In my account, Mood in interrogatives is different from Mood in declaratives in English: It keeps its features. The focus feature is realized as prosodic stress on the auxiliary that occupies Mood (cf. (52)).

- (52)

In imperatives, no auxiliary is merged. There is evidence that the lexical verb also moves higher than in declaratives in this clause type. This is illustrated by the word order contrasts in (53). In the declarative in (53-a), the adverb often precedes the verb and in the imperative in (53-b), it follows the verb.

- (53)

- a.

- You often call me.

- b.

- Call me often!

I propose that the lexical verb moves to T in imperatives (see also Han 2000) and does not remain in V as in declaratives. The sentence mood feature and the focus feature, if present, are donated to T. This explains why do-insertion does not take place in imperatives.

- (54)

- a.

- You call me often!

- b.

- Nobody move! (Han 2000: 277: ex 8b)

- c.

- *Move nobody!

Motivation for locating the finite verb in T rather than Mood stems from examples like (54-a) and (54-b) contrasting with (54-c). They show that if a subject is realized in English imperatives, it precedes the verb (cf. (55)).

- (55)

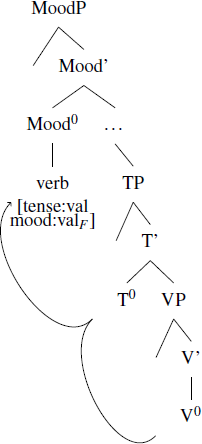

In Spanish, the strategy employed in declaratives is only grammatical in polar questions, but not in wh-questions nor imperatives. I suggest that this is the case because Mood is not empty but occupied in Spanish imperatives and wh-interrogatives, which makes the merger of the particle impossible. For wh-interrogatives, I propose that Mood is occupied by the wh-operator (cf. also for instance Rizzi 2001 and Prieto & Rigau 2007 for an operator account of interrogatives).

The word order of Spanish interrogatives differs from declaratives: There is subject-verb inversion which is obligatory in wh-questions and optional in polar questions. This could be taken to suggest that the verb itself occupies Mood. In spite of this, my analysis does not assume movement of the verb to the left periphery in interrogatives (contra Torrego 1984 and Rizzi 1996). In line with Suñer (1994); Belletti (2004) and Cardinaletti (2007) I assume that the verb remains in T (cf. (57)). One of the arguments against T-to-Mood movement put forward in the literature is related to TP peripheral adverbs in interrogatives. Just as in declaratives, adverbs like todavía ‘still’ tend to precede the finite verb, suggesting that the verb remains in TP in polar (56-b) and wh-questions (56-a).14

- (56)

- a.

- Spanish

- ¿Qué

- which

- idioma

- language

- todavía

- still

- estudia

- studies

- Pepita

- Pepita

- en

- in

- su

- her

- tiempo

- time

- libre?

- free

- ‘Which language does Pepita still study in her free time?’

- (Suñer 1994: 354, ex. 21c)

- b.

- ¿Todavía

- still

- estudia

- studies

- Pepita

- Pepita

- ruso

- Russian

- en

- in

- su

- her

- tiempo

- time

- libre?

- free

- ‘Does Pepita still study Russian in her free time?’

Notably, in English, only the order in which the verb precedes the adverb is grammatical (cf. the translation of the examples in (56)). This fact again supports the analysis of English do in Mood.

- (57)

The properties of Spanish (verum focused) interrogatives are captured by the analyses in (57). The finite verb moves from V to T and the sentence mood feature is checked by the wh-operator in Mood in the wh-question and expressed on sí in the polar question.

The properties of Spanish imperatives support an analysis that assumes T-to-Mood movement of the imperative verb. The verb precedes high adverbs like todavía. The reverse order is ungrammatical (58-a) vs. (58-b). As stated above, this contrasts with the orders we find in unmarked declaratives (58-c) and interrogatives (58-d) where todavía precedes the verb.15

- (58)

- a.

- Spanish

- ¡Escucha

- listen

- todavía!

- still

- ‘Listen some more!’ (CdE)

- b.

- *¡Todavía

- listen

- escucha!

- still

- c.

- Juan

- Juan

- todavía

- still

- escucha

- listens

- la

- the

- misma

- same

- canción.

- song

- ‘Juan is still listening to the same song.’

- d.

- ¿Todavía

- still

- escucha

- listen

- la

- the

- misma

- same

- canción?

- song

- ‘Is he still listening to the same song?’

Another strong argument in favor of the T-to-Mood movement of imperative verbs is the postverbal position of clitic pronouns, illustrated in (59-a) and (59-b).

- (59)

- a.

- Spanish

- ¡Llámame!

- call-me

- ‘Call me!’

- b.

- *¡Me

- me

- llama!

- call

In interrogatives (60-a) (vs. (60-b)), just as in declaratives, clitics are preverbal. This once again supports the idea that in these clause types finite verbs remain in T.

- (60)

- a.

- Spanish

- ¿Me

- me

- llamas?

- call

- ‘Will you call me?’

- b.

- *¿Llamas

- call

- me?

- me

The analysis I assume is given in (61). The finite verb moves from V to T to Mood.

- (61)