1 Introduction

Psych verbs, i.e., verbs expressing emotions, are puzzling across languages in many respects. In current debates, there are two types of views. Some scholars argue that psych verbs are essentially similar to other well-known verb classes (cf. Pesetsky 1995; Arad 1998 a, b, 1999; Rothmayr 2009; Grafmiller 2013; Alexiadou & Iordăchioaia 2014, henceforth A&I; Żychliński 2016; Hirsch 2018, van Gelderen 2018; Garcia-Pardo 2020, i.a.), but that their special property is that they are usually ambiguous between several regular patterns, which is reflected, among others, in their participation in verb alternations and in their (non-)acceptability in contexts that impose particular aspectual interpretations. However, there are analyses that attribute the puzzling properties of psych-verbs to the different nature of emotional eventualities or to the experiencer participant (cf. Rozwadowska 2003, 2007, 2012, 2020; Landau 2010; Marín & McNally 2011; Fábregas & Marín 2015, 2017, 2020; Temme & Verhoeven 2016; Fritz-Huechante et al. 2018; Biały 2020; Cançado et al. 2023). One of the assumptions in contemporary research on the lexicon-syntax interface is that verbs that undergo similar alternations form natural grammatical and semantic classes (Levin 1993) and thus the exploration of alternating patterns can provide evidence for the (non)-special nature of psych verbs.

As noted in Ramchand (2013), argument relations have an inherent structure to them, which is manifested in the syntactic representation. Therefore, argument structure alternations provide a good testing ground for identifying wide classes of verbs with semantically recognizable profiles for which a particular alternation is productively available. Our aim is to capture the regular patterns (as opposed to other regular patterns) through syntactic representations which account for the similarities and differences between psych verbs and COS verbs, thus contributing to the debate related to the puzzle of experiencer predicates and meeting the goal of the present volume, which is to bring together various strands of recent research on argument structure that promote dialogue between the proponents of derivational and non-derivational accounts of various convictions. Moreover, in accord with the general consensus in the literature, we assume that it is the event structure which determines the argument structure and syntactic representations. We attribute the differences in argument alternations to different temporal organization of subevents described by the verb classes analyzed in this paper.

We focus on the alternation between two types of psychological predicates in Polish, viz. EO verbs and their ES counterparts and compare it to the causative/anticausative alternation, since such comparison is important in deciding whether psych verbs can be reduced to causative COS verbs. The EO/ES alternation is common cross-linguistically (cf. Sonnenhauser 2010 for Russian, A&I for Greek and Romanian, Biały 2005 for Polish, Hirsch 2018 for German, Cançado et al. 2023 for Brazilian Portuguese, i.a.), and is illustrated for English in (1):

- (1)

- a.

- The television set worried John.

- b.

- John worried about the television set.

- (Pesetsky 1995: 57)

Whereas John in both (1a) and (1b) acts as an experiencer – object or subject, respectively – the other argument – the television set – may function as a causer in (1a), while in (1b) it represents a T(arget)/S(ubject)M(atter) argument (Pesetsky 1995), not a causer. The EO/ES alternation in (1) is not frequent in English; only a few verbs participate in it, such as worry, (1), puzzle, grieve, and delight (Pesetsky 1995: 73).1 Pesetsky (1995: 96) notes that English lacks non-activity ES verbs expressing emotions such as anger, annoyance and satisfaction. In other words, English has no verbs meaning ‘to be amused’ and ‘to be pleased’, or their inchoative variants, such as ‘to become amused’ and ‘to become pleased’.

The EO/ES alternation has been commonly viewed in the literature as an instance of the well-studied causative/anticausative alternation (Haspelmath 1993; Levin & Rappaport Hovav 1995; Piñon 2001; Reinhart 2002; Chierchia 2004; Schäfer 2008; Koontz-Garboden 2009; Alexiadou et al. 2006, 2015). The causative/anticausative alternation is typically associated with COS verbs (Alexiadou et al. 2006, 2015; Schäfer 2008, 2009; Tubino-Blanco 2020, a.o.),2 and is illustrated in (2) below:

- (2)

- a.

- John broke the window.

- b.

- The window broke.

The causative/anticausative alternation relates pairs of transitive and intransitive verbs, where the intransitive variant, (2b), describes an eventuality in which the theme has undergone a COS and the transitive variant expresses causation of the COS, (2a) (cf. Mangialavori Rasia this volume, for an analysis of intransitive causatives in English and Romance expressing a COS). Eventive EO verbs have also been treated as COS predicates by the proponents of the non-special nature of psych verbs, because the pattern in (3), taken from Reinhart (2002: 34), is similar to (2).

- (3)

- a.

- The doctor worried Max.

- b.

- Max worried.

The EO verb in (3a) co-occurs with the experiencer and the causer argument, while the ES alternant in (3b) is monadic with just the ES argument. Thus, (3a) is similar to (2a), while (3b) resembles (2b). The EO/ES alternation in English is not morphologically marked, in contradistinction to other languages, including Polish, as in (4) below, where the ES counterpart, (4b), of the EO verb, (4a), is marked with the reflexive clitic się, similarly to the anticausative variant of COS verbs, participating in the causative alternation, presented in (5).

- (4)

- a.

- Brak

- lack.nom

- pieniędzy

- money.gen

- zirytował

- irritated

- Marię.

- Mary.acc

- ‘Lack of money irritated Mary.’

- b.

- Maria

- Mary.nom

- zirytowała

- irritated

- się

- rf

- (brakiem

- lack.inst

- pieniędzy)

- money.gen

- ‘Mary started to be irritated with lack of money.’

- (5)

- a.

- Podmuch

- gust.nom

- wiatru

- wind.gen

- złamał

- broke.perf

- gałąź.

- branch.acc

- ‘The gust of wind broke the branch.’

- b.

- Gałąź

- branch.nom

- złamała

- broke.perf

- się

- rf

- (od

- from

- podmuchu

- gust

- wiatru).

- of-wind

- ‘The branch broke from the gust of wind.’

- c.

- Gałąź

- branch.nom

- złamała

- broke.perf

- się

- rf

- (*podmuchem

- (gust.inst

- wiatru).

- wind.gen)

- ‘The branch broke (*with the gust of wind).’

Note, however, that with COS verbs, the optional causer argument cannot appear in the instrumental case, (5c), in contradistinction to the non-experiencer argument in (4b). If present, the causer is expressed by an od ‘from’- PP, (5b).

Pesetsky (1995) argues that English differs from French, Italian, and Russian (as well as from Polish, (4b)) in that it does not have reflexive clitics, which is responsible for the absence of ES counterparts of bound EO verb roots in English. According to Pesetsky (1995), the reflexive clitic added to the verbal root yields a non-causative form, and since English has no reflexive clitics, the non-causative ES form cannot be derived.3 The morphological marking has often served as an argument that there is a derivational relationship between the two variants (Dowty 1979; Williams 1981; Grimshaw 1990; Levin & Rappaport Hovav 1995; Reinhart 2000; Chierchia 2004; Kallulli 2007; Koontz-Garboden 2009). However, cross-linguistically the causative/anticausative alternation shows a lot of morphological variation, which makes it impossible to univocally determine the directionality relationship between the causative and the anticausative variant (cf. Haspelmath 1993, and Alexiadou et al. 2015: chapter 2 for the criticism of derivational approaches to the causative/anticausative alternation).

The causative/anticausative alternation has been analysed in the literature in the following three ways: (i) decausativisation, (ii) causativisation and (iii) the common-base approach (Schäfer 2009; Tubino-Blanco 2020). These three approaches also prominently figure in the analyses of the EO/ES alternation. In the decausativisation account of the EO/ES alternation, proposed by Reinhart (2002), the ES variant is derived from the EO one by removing the causer argument in the lexicon. In their analysis of Spanish reflexive psychological verbs, Machicao y Priemer & Fritz-Huechante (2020) postulate a lexical rule to derive the morphologically more complex (but semantically simpler) cliticized forms from the morphologically simpler (but semantically more complex) transitive causative EO verbs. In the causativisation analysis, due to Pesetsky (1995), the ES form represents the basic variant from which the EO form is derived by means of the zero CAUS morpheme. In the common-base approaches (Embick 2004; Alexiadou et al. 2006, 2015, A&I; Pylkkänen 2008), EO and ES verbs share a part of syntactic structure – the common base. In the decausativisation and causativisation accounts, EO verbs and their ES cognates are viewed as derivationally related either by a lexical rule (Reinhart 2002; Machicao y Priemer & Fritz-Huechante 2020) or by a syntactic rule (Pesetsky 1995). In common-base approaches, EO verbs and their ES counterparts are considered not to be derivationally related, since neither variant acts as the basic one.

The aims of this paper are twofold. Our first aim is to check whether the EO/ES alternation in Polish, (4), may be subsumed under the causative/anticausative alternation, (5), as proposed in Haspelmath (1993), Levin & Rappaport Hovav (1995), Reinhart (2002), and A&I. The second objective is to provide a structural analysis of alternating EO verbs and their ES counterparts with a view to determining whether they are derivationally related in the syntax. We argue that the EO/ES alternation in Polish cannot be subsumed under the causative/anticausative alternation. This is because EO verbs do not pattern with COS verbs (cf. Section 2), as regards the realization of the alleged causer and the event structure configuration. We attribute the differences between the two alternations to different sub-event composition. Consequently, we treat the EO/ES alternation in Polish as an alternation of its own kind, called the psych verb alternation after Rott et al. (2020: 402).

An analysis of the syntactic structure of eventive EO verbs and their ES counterparts demonstrates that they cannot be derivationally related by a syntactic rule. We argue that they share a common base which corresponds to an unergative vP with an experiencer as an external argument, which nonetheless does not occupy Spec, VoiceP, but a lower Spec, vP position (Tollan 2018; Oikonomou & Alexiadou 2022). We thus propose that the ES and EO are merged in a uniform structural position, viz. Spec, vP, in conformity with Baker’s (1988) Uniformity of Theta Assignment Hypothesis (UTAH). EO verbs differ from their ES variants in Voice, which in the latter is expletive (non-thematic), filled with the reflexive marker się, while in the former it is thematic, introducing the causer. Despite sharing the common base, EO verbs and their ES counterparts do not stand in a derivational relationship with each other, since neither the structure of EO verbs nor the structure of their reflexive ES alternants can be viewed as the basic one. The causer argument of EO verbs occupies Spec, VoiceP, not Spec, vP (contra Alexiadou & Anagnostopoulou 2019, 2020, henceforth A&A), since Polish causative EO verbs can form verbal passive, the structure dependent on the projection of Voice (A&A 2019, 2020). Moreover, we propose that the reflexive marker found with ES alternants of eventive EO verbs in Polish has no reflexive function, but it acts as a valency reducing operator. We argue that both with reflexive ES verbs and reflexively marked anticausatives, the reflexive marker occupies the same structural position, viz. the head of expletive Voice (Schäfer 2008), and thus blocks the realization of an argument in Spec, VoiceP in these two structures.

The paper consists of four sections. In Section 2 we provide arguments against subsuming the EO/ES alternation in Polish under the causative/anticausative alternation. In Section 3, we focus on the syntactic structure of causative EO verbs and their ES counterparts. We analyse the status of the reflexive marker, found with Polish reflexive ES verbs, and the structural position of the EO and the ES. We also present evidence that despite sharing a common base, EO verbs in Polish and their ES cognates cannot be derivationally related by a syntactic rule. Finally, we juxtapose the structure of eventive EO/ES verbs with the structure of causative/anticausative predicates to account for the similarities and differences that these two types of alternation show. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2 EO/ES alternation in Polish is not a psych causative alternation

In this section we show that the EO/ES alternation in Polish is not an instance of the causative/anticausative alternation in the psych domain (called the psych causative alternation by A&I). Section 2.1 contains a brief overview of A&I’s analysis of the EO/ES alternation in Greek and Romanian as the psych causative alternation. Section 2.2 presents evidence that Polish EO verbs and their reflexive ES counterparts cannot be viewed as COS verbs, which typically undergo the causative/anticausative alternation (Alexiadou et al. 2006, 2015; Schäfer 2009; Tubino-Blanco 2020, a.o.). Section 2.3 focuses on reflexive ES alternants of eventive causative EO verbs in Polish co-occurring with two types of alleged causers – instrumental DPs and od ‘from’-PPs. We argue that instrumental DPs are not causers, but rather T/SM arguments, while od-phrases are not licensed by the causative semantics of reflexive ES verbs – they have inherent causative meaning of their own. We claim that reflexive ES verbs are neither anticausative nor causative. In Section 2.4 we postulate that alternating EO/ES verbs have a different event structure from COS verbs, namely eventive EO verbs and their ES counterparts consist of an initial boundary event that triggers the following unbounded state, in contrast to COS verbs, whose complex event structure is a sequence of the causing sub-event and a result state. Finally, Section 2.5 summarizes the discussion on the nature of the EO/ES alternation in Polish.

2.1 The causative/anticausative alternation in the psych domain

In their analysis of alternating psych verbs in Greek and Romanian, A&I argue that the different behaviour of psych verbs results from their aspectual ambiguity rather than from the presence of the experiencer in their argument structure. In particular, A&I demonstrate that eventive EO verbs in Greek and Romanian (in contrast to stative EO verbs) are indeed causative and participate in the causative/anticausative alternation like COS verbs.

The arguments put forward by A&I to support their claim are: (i) the same morphological marking of the EO/ES alternation and the causative/anticausative alternation, (ii) the licensing of causer-PPs, and (iii) event complexity. First, both in Greek and Romanian, the morphological form of ES counterparts of eventive EO verbs is the same as that of anticausative variants of causative verbs, i.e., the non-active morphology in Greek, and the reflexive clitic in Romanian (6b, 7b).4 Secondly, Greek and Romanian ES counterparts of eventive EO verbs combine with causer-PPs, i.e., me ‘with’ in Greek and de la ‘from’ in Romanian, (6b), which can also appear with anticausatives, (7b).

- (6)

- a.

- Ştirile

- news.the

- au

- have

- enervat-o

- annoyed-her

- pe Maria. Romanian EO verb

- acc Mary

- ‘The news has annoyed Mary.’

- b.

- Maria

- Mary

- s-a

- rf-has

- enervat

- annoyed

- de la ştiri. Romanian ES verb

- of at news

- ‘Mary got annoyed with the news.’

- (7)

- a.

- Ion

- John

- a

- has

- ars

- burnt

- mâncarea. Romanian causative verb

- food.the

- ‘John burnt the food.’

- b.

- Mâncarea

- food.the

- s-a

- rf-has

- ars

- burnt

- de la

- of at

- focul

- fire

- puternic. Romanian anticausative verb

- strong

- ‘The food burnt with the strong fire.’ (A&I: 63, ex. (30), (29))

Thus, ES alternants of eventive EO verbs pattern like anticausatives. Prepositions me ‘with’ and de la ‘from’ can only introduce causers, and they differ from prepositions which introduce the T/SM argument, namely ja ‘about’ in Greek and de ‘of’ in Romanian. The latter only appear with stative EO verbs, which do not participate in the causative/anticausative alternation. Note that in A&I, the stativity vs. eventivity is diagnosed by standard telicity test, namely the co-occurrence with durative for-adverbials and time span in-adverbials, respectively. In other words, eventive interpretation is telic, whereas stative interpretation is atelic. Telicity is understood there as termination of the process leading to the result state. The authors admit that it is not always easy to identify all possible interpretations. According to A&I, the presence of causative prepositions typical of anticausatives with ES alternants of causative EO verbs, (6b), indicates that these ES verbs are also anticausative like (7b).

The final argument for treating the EO/ES alternation as the psych causative alternation comes from event complexity. A&I assume, following the “received” view (Grimshaw 1990; Levin & Rappaport-Hovav 1995, 2005; Rothmayr 2009), that complex events are composed of two sub-events: the causing event and the result state, ordered in time. This corresponds to predicate decomposition in Dowty (1979), Levin & Rappaport Hovav (1995, et seq). According to these approaches, achievements have the structure as in (8), and accomplishments as in (9), either with an agent, (9a) or a causer, (9b):

- (8)

- [become [x <state>]]

- (9)

- a.

- [[x act<manner>] cause [become [y <state>]]]

- b.

- [x cause [become [y <state>]]]

It is commonly assumed that causativity and change of state go together, so any change of state is taken to describe a change culmination that is part of the bi-eventive eventuality (see Grimshaw 1990; Pustejovsky 1991; Rappaport Hovav & Levin 1998; Reinhart 2002; Ramchand 2008; Rothstein 2008; Verhoeven 2010; Cuervo 2015, a. o.). Consequently, the presence/absence of change affects the presence/absence of causation. Thus, the event structure of an accomplishment predicate consists of an activity and a resulting state, where the result is predicated of the direct object, whereas the subject is engaged in the activity that causes the result (COS). A cause argument “will always be associated with the first sub-event, which is causally related to the second sub-event” (Grimshaw 1990: 26). Some researchers also postulate stative causation (Arad 1998a, b, 1999; Pylkkänen 2000; Rothmayr 2009; García-Pardo 2020), where both sub-events are co-temporal.

Following Chierchia (2004), Alexiadou et al. (2006) and Koontz-Garboden (2009), A&I argue that anticausatives, like causatives, involve a causative event, and are thus bi-eventive. In addition to the presence of causer-PP diagnosing the causing subevent, the support for their bi-eventivity comes from the presence of the result state, diagnosed by applying the adverb again and its relevant interpretation. Following von Stechow (1995, 1996), A&I note that again in causative contexts may have two interpretations, i.e., repetitive (denoting the repetition of the causing event) and restitutive (denoting the restitution of the previous state). These two interpretations are also associated with again in anticausatives, (10):

- (10)

- The door opened again. (A&I: 66)

- a.

- Something happened again and as a result the door is open. repetitive

- b.

- Something happened and as a result the door is open again. restitutive

In the repetitive interpretation, again modifies the CAUSE component, and in the restitutive interpretation again modifies the result state, (11):

- (11)

- a.

- (again [CAUSE [BECOME the door <OPEN>]]) repetitive

- b.

- [CAUSE [BECOME (again [the door <OPEN>])]] restitutive

- (modelled on A&I: 65, ex. (37))

A&I argue that ES cognates of causative EO verbs in Greek and Romanian, when modified by equivalents of again, trigger the repetitive and restitutive interpretation, in the way analogous to anticausatives.5 With this background, let us examine the properties of EO/ES alternation in Polish.

2.2 Comparison of EO/ES alternation with causative/anticausative alternation in Polish

To verify the claim that the special behaviour of psych verbs and their appearance in different morphosyntactic patterns might be related to their aspectual ambiguity rather than to their specialness as a semantic class, in the first part of this section, we present patterns of the EO/ES alternation in Polish, found with different aspectual classes of psych verbs. We distinguish grammatical aspect from lexical aspect and examine the way they affect the alternation. Afterwards, we compare the EO/ES alternation with the causative/anticausative alternation in Polish.

First, let us observe that the majority of Polish verbs, including psychological predicates, appear in two distinct aspectual forms: perfective and imperfective. This aspectual contrast is crucial for verifying previous claims regarding the sensitivity of psych causative alternation to aspect. The perfective/imperfective contrast is exemplified for an EO verb fascynować ‘to fascinate’ in (12) below:

- (12)

- a.

- Muzyka

- nusic.nom

- klasyczna

- classical

- fascynowała

- fascinated.imp

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- ‘Classical music fascinated Mark.’

- b.

- Muzyka

- nusic.nom

- klasyczna

- classical

- zafascynowała

- started_to_fascinate.perf

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- ‘Classical music started to fascinate Mark.’

The perfective form in (12b) has a prefix za-, while its imperfective counterpart in (12a) has no prefix. Imperfective EO verbs describe a state, whereas perfective EO verb forms refer to an onset of a state (Rozwadowska 2012, 2020) and are therefore viewed as eventive. The contrast between stative imperfective EO verb forms and eventive perfective EO verb forms is shown in (13) and (14):

- (13)

- Muzyka

- nusic.nom

- klasyczna

- classical

- fascynowała

- fascinated.imp

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- #Stało

- happened

- się

- rf

- to

- this

- dzięki temu,

- thanks this

- że

- that

- jego

- his

- rodzice

- parents

- brali

- were_taking

- go

- him

- na koncerty

- to concerts

- w filharmonii.

- in concert_hall

- ‘Classical music fascinated Mark. #This happened because his parents were taking him to concerts in the concert hall.’

- (14)

- Muzyka

- nusic.nom

- klasyczna

- classical

- zafascynowała

- fascinated.perf

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- Stało

- happened

- się

- rf

- to

- this

- dzięki temu,

- thanks this

- że

- that

- jego

- his

- rodzice

- parents

- brali

- were_taking

- go

- him

- na koncerty

- to concerts

- w filharmonii.

- in concert_hall

- ‘Classical music started to fascinate Mark. This happened because his parents were taking him to concerts in the concert hall.’

Example (13) shows that the imperfective EO verb form is incompatible with the verb stać się ‘to happen’, in contradistinction to its perfective variant, (14). This supports the claim that imperfective EO verb forms are stative, whereas the perfective ones are eventive (for more tests to distinguish stative from eventive EO verbs in Polish, cf. Biały 2005).6

Both stative (imperfective) and eventive (perfective) EO verbs in Polish participate in the alternation in which the experiencer surfaces in the subject position, cf. (15) and (16), which correspond to (12a) and (12b), respectively:

- (15)

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- fascynował

- fascinated.imp

- się

- rf

- muzyką

- music.inst

- klasyczną.

- classical

- ‘Mark was fascinated with classical music.’

- (16)

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- zafascynował

- started_to_be_fascinated.prf

- się

- rf

- muzyką

- music.inst

- klasyczną.

- classical

- ‘Mark got fascinated with classical music.’

The ES variants of EO verbs surface with the reflexive marker się, and the non-experiencer argument appears in the instrumental case.7 The non-experiencer argument of stative EO verbs represents a T/SM argument of Pesetsky (1995), (12a), while with eventive transitive EO verbs it is ambiguous between a trigger of emotion (possibly, a causer) or a T/SM, (12b). This potential ambiguity of the non-experiencer argument of eventive EO verbs raises the question of the status of the instrumental DP found with reflexive ES verbs. The instrumental DP is obligatory with some verbs, (15) and (16), but it need not be so. There are ES counterparts of stative (imperfective) and eventive (perfective) EO verbs, where the instrumental DP is optional, cf. (17b) and (18b) below.8

- (17)

- a.

- Filmy

- films.nom

- w telewizji

- on TV

- (z)nudziły

- bored.perf/imp

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- ‘Films on TV bored/started to bore Mark.’

- b.

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- (z)nudził

- bored.perf/imp

- się

- rf

- (filmami

- (films.inst

- w telewizji).

- on TV)

- ‘Mark got bored with films on TV.’

- (18)

- a.

- Głupie

- idle

- gadanie

- talk.nom

- (z)denerwowało

- annoyed.perf/imp

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- ‘Idle talk started to annoy/annoyed Mark.’

- b.

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- (z)denerwował

- annoyed.perf/imp

- się

- rf

- (głupim

- idle

- gadaniem).

- talk.inst

- ‘Mark got annoyed with idle talk.’

The argument patterns in (15)–(18) are identical for both eventive (perfective) and stative (imperfective) verbs. We conclude that neither the form of the non-experiencer argument in the ES alternant nor its obligatoriness/optionality are sensitive to grammatical aspect.

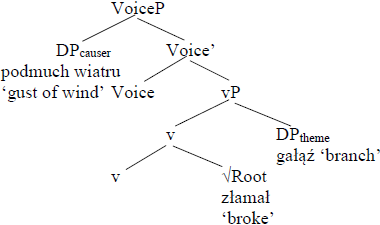

As for the lexical aspect, following Arad (1998a, b), Biały (2005) divides Polish EO verbs into lexically stative and lexically eventive psych verbs. Accordingly, fascynować ‘to fascinate’ in (15) and (16) is a lexically stative EO verb, whereas the verbs like (z)nudzić ‘to bore’ or (z)denerwować ‘to annoy’ in (17) and (18), are classified as lexically eventive. Again, both types systematically occur with the instrumental case-marked DP in the reflexive ES alternant. Thus, we observe that the realization of the non-experiencer argument in reflexive ES variants as the instrumental DP is the same for lexically eventive and lexically stative EO verbs. With some (arguably) lexically eventive psych verbs illustrated in (17b)–(18b) this argument is optional, with others – such as the lexically stative OE verb in (15)–(16), it is obligatory. Therefore, following Rozwadowska & Bondaruk (2019), we conclude that the EO/ES alternation is not sensitive to aspectual distinctions, either grammatical or lexical (in contrast to Greek and Romanian or to Brazilian Portuguese, cf. Cançado et al. 2023). We refer to this alternation here as the psych verb alternation (Rott et al. 2020), and focus on a detailed comparison of the EO/ES alternation with the causative/anticausative alternation, presented in (5), and repeated for convenience in (19):

- (19)

- a.

- Podmuch

- gust.nom

- wiatru

- of-wind

- złamał

- broke.perf

- gałąź.

- branch.acc

- ‘The gust of wind broke the branch.’

- b.

- Gałąź

- branch.nom

- złamała

- broke.perf

- się

- rf

- (od

- from

- podmuchu

- gust

- wiatru).

- of-wind

- ‘The branch broke from the gust of wind.’

- c.

- Gałąź

- branch.nom

- złamała

- broke.perf

- się

- rf

- (*podmuchem

- (gust.inst

- wiatru).

- wind.gen)

- ‘The branch broke (*with the gust of wind).’

Sentence (19a) represents a causative structure, whereas (19b) corresponds to its anticausative variant. Importantly, the verb in the anticausative variant appears with the reflexive marker się, as in the reflexive ES variant in the EO/ES alternation, cf., e.g. (15)–(16). Sentence (19b) also hosts an optional causer-PP, introduced by the preposition od ‘from’. Note that the causer in anticausatives can never be realized as a DP in the instrumental case, (19c), in contrast to the reflexive ES construction (see (15), (16), (17b), and (18b)). This is different from Greek and Romanian, where non-experiencers with ES alternants of eventive EO verbs appear in the same form as causers in anticausatives of COS verbs (cf. (6) and (7)).

Summing up, the fact that the instrumental DP cannot realize a causer with anticausatives, (19c), but is felicitous with reflexive ES verbs indicates that ES verbs systematically do not pattern like anticausatives. Moreover, with some ES verbs the instrumental DP is obligatory, whereas the PP causer in anticausatives is always optional. This makes us conclude that the psych reflexive alternation in Polish cannot be subsumed under the causative/anticausative alternation. Importantly, both aspectual verb forms as well as eventive and stative roots pattern in the same way (15)–(18). Thus, there is no evidence that the participation in the alternation depends on aspect (either grammatical or lexical). From now on we will concentrate on eventive forms of psych verbs, i.e., their perfective variants.

2.3 Instrumental DPs vs. od ‘from’-PPs

To provide further arguments for the claim that the instrumental DP with Polish reflexive ES alternants of EO verbs is a T/SM and not a causer, let us adopt Pesetsky’s (1995: 57–58) one-way implicational relation between statements about the T/SM and statements about causers, quoted in (20), and let us construct the relevant Polish sentences in (21).

- (20)

- a.

- If X worried about Y, then Y worried X. [true]

- b.

- If Y worried X, then X worried about Y. [false]

- (21)

- a.

- Artykuł

- article.nom

- w gazecie

- in newspaper

- zdenerwował

- annoyed.perf

- Marka,

- Mark.acc

- ale Marek

- but Mark.nom

- nie

- not

- zdenerwował

- annoyed.perf

- się

- rf

- artykułem

- article.inst

- (tylko

- only

- tematem,

- subject

- którego

- which

- ten

- this

- artykuł

- article

- dotyczył).

- dealt

- ‘The newspaper article annoyed Mark, but Mark did not start to be annoyed with the article (only with the topic it dealt with).’

- b.

- Choroba

- illness.nom

- zmartwiła

- worried.perf

- Marka,

- Mark.acc

- ale

- but

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- nie

- not

- zmartwił

- worried.perf

- się

- rf

- chorobą

- illness.inst

- (tylko

- only

- koniecznością

- necessity.inst

- opuszczenia

- missing.gen

- zajęć.)

- classes.gen

- ‘The illness worried Mark, but Mark did not start to be worried with the illness but with the necessity to miss the classes.’

Sentences in (21) demonstrate that causer is distinct from the T/SM and that the latter is encoded as an instrumental DP.

Still another piece of evidence that the instrumental DP in the Polish psych verb alternation is a T/SM comes from the ‘verbs of interest’ subclass. Verbs of interest are uncontroversially stative across languages and do not co-occur with a causer but with a T/SM. In Polish, their T/SM participant is always realized as an instrumental DP, (22) (see also (15)):

- (22)

- Janek

- John.nom

- interesuje

- interest.imp

- się

- rf

- składnią

- syntax.inst

- ‘John is interested in syntax.’

Finally, with some EO verbs we can augment the argument structure by adding the prefix za-, which not only perfectivizes the verb, but also allows the addition of an agent on top of the experiencer and T/SM. This is most frequent for the EO verb interesować ‘to interest’, but also possible with some other verbs, (23):

- (23)

- a.

- Nauczyciel

- teacher.nom

- zainteresował

- interested.perf

- Marka

- Mark.acc

- matematyką.

- maths.inst

- ‘The teacher got Mark interested in mathematics.’

- b.

- Premier

- prime minister.nom

- zaniepokoił

- bothered.perf

- nas

- us.acc

- podwyżkami

- rise.instr

- podatków.

- taxes.gen

- ‘The Prime Minister made us irritated with tax rises.’

In triadic structures (23a)–(23b), the agent acts as a kind of causer and the instrumental DP cannot be a causer, but a T/SM – positively or negatively evaluated by the experiencer.

Let us also note that ES alternants of EO verbs in Polish may sometimes occur with the causer realised as od ‘from’-PP, (24b) and (25b):

- (24)

- a.

- Nadmiar

- excess.nom

- obowiązków

- duties.gen

- zirytował

- irritated.prf

- Marię.

- Mary.acc

- ‘Excessive duties irritated Mary.’

- b.

- Maria

- Mary.nom

- zirytowała

- started_to_irritate.prf

- się

- rf

- od

- from

- nadmiaru

- excess

- obowiązków.

- duties.gen

- ‘Mary started to be irritated from excessive duties.’

- (25)

- a.

- Słowa

- words.nom

- pocieszenia

- consolation.gen

- uspokoiły

- calmed.perf

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- ‘The words of consolation calmed Mark.’

- b.

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- uspokoił

- calmed.perf

- się

- rf

- od

- from

- słów

- word

- pocieszenia.

- consolation.gen

- ‘Mark calmed from the words of consolation.’

The pattern in (24b) and (25b) is reminiscent of the one found with the anticausative in (19b). In (19b), od ‘from’-PP is used to signal the cause in the unaccusative structure (the reflexive anticausative variant of the causative sentence in (19a)). In (24b)–(25b) this phrase co-occurs with the reflexive ES counterpart of the transitive EO verbs in (24a)–(25a). However, despite the surface similarity between (19b) and (24b)–(25b), these data do not provide support for the causative/anticausative nature of the EO/ES alternation, because causer od ‘from’-PPs are rather rare and unproductive with reflexive ES verbs, in contrast to their productivity with anticausatives of COS verbs. Compare (26), where the ES variant of (26a) is ungrammatical with the od ‘from’-PP, and it becomes acceptable only when this PP is replaced with a different causer PP z powodu ‘because of’, (26b).

- (26)

- a.

- Wysokie

- high

- koszty

- costs nom

- utrzymania

- living.gen

- zdenerwowały

- annoyed.perf

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- ‘High costs of living annoyed Mark.’

- b.

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- zdenerwował

- annoyed.perf

- się

- rf

- (*od

- from

- wysokich

- high

- kosztów

- costs

- utrzymania)

- living.gen

- /z powodu

- for reason

- wysokich

- high

- kosztów

- costs

- utrzymania.

- living.gen

- ‘Mark got annoyed because of high costs of living.’

Moreover, the occurrence of causer od ‘from’-PP is not restricted to unaccusative structures (in contradistinction to its English counterpart from, cf. Alexiadou et al. 2006, 2015, Schäfer 2009), but phrases of this type may also co-occur with unergatives (cf. Rozwadowska & Bondaruk 2019), like skakać ‘jump’, (27):

- (27)

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- skakał

- jumped

- od

- from

- nadmiaru

- excess

- energii.

- energy

- ‘Mark was jumping because of having too much energy.’

The causer od ‘from’-PP can also co-occur with adjectives, (28):

- (28)

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- jest

- is

- gruby

- fat

- od

- from

- obżarstwa.

- gluttony

- ‘Mark is fat because of gluttony.’

Since causer od ‘from’-PPs may be found not only with unaccusative, but also with unergative verbs and with adjectives, we conclude that the occurrence of these PPs with reflexive ES verbs does not bear on the anticausative (unaccusative, cf. Section 3.2.1) status of these predicates.9

To wrap up, we have adopted Pesetsky’s (1995) one-way implicational relation between statements about the T/SM and statements about causers to demonstrate that the two roles are distinct (in line with Pesetsky). We have argued that in the alternation analysed here, instrumental DPs realize T/SMs, not causers. Instrumental DPs differ from od ‘from’-PPs, which themselves introduce the causative semantics and do not depend on the causative semantics of the predicate they co-occur with.

2.4 The complexity of EO psych events

As discussed above, verb participation in (psych) causative/anticausative alternation is correlated with complexity of event structure (cf. Section 2.1). Change of state, typical of accomplishments and achievements, is taken to describe a change culmination that is part of the bi-eventive eventuality (cf. (8) and (9)). Cross-linguistically, eventive EO verbs represent a controversial class of predicates, because there is no agreement as to whether they should be classified as activity verbs, achievements or accomplishments (e.g., Grimshaw 1990; van Voorst 1992; Tenny 1994; Author; Landau 2010, i.a.). Rozwadowska (2020) argues that psych verbs (both EO and ES) have logical and temporal entailments opposite to those of COS verbs, and that there is a need to introduce left-bounded eventualities in addition to right-bounded events (see also Bar-el 2005; Marín & McNally 2011; Fritz-Huechante et al. 2018; Machicao y Priemer & Fritz-Huechante 2020). We argue that alternating EO/ES verbs are not composed of the causing subevent culminating in the result state. Instead, we treat psych predications as descriptions of eventualities consisting of an instantaneous triggering (inceptive) eventuality that initiates an unbounded state.10 The concept of the “trigger” is reminiscent of the trigger in stative causation in Arad (1998b) and Pylkkänen (2000). It is also adopted in Cançado et al. (2023) in their analysis of stative EO verbs in Brazilian Portuguese. However, our account is crucially different. First, these accounts concern stative EO verbs, whereas we analyze eventive psych verbs. Second, the above-mentioned authors assume co-temporality of two sub-eventualities (the causing state and the experiencing/perception state). In contrast, we appeal to the left boundary trigger (initiating subevent), marked by the perfective form of the verb, and not to the temporal coexistence of two states. In our analysis, we use selected logical and temporal entailments, at the same time rejecting the again test as not helpful here.11

Rozwadowska (2003, 2012, 2020) argues that the logico-temporal entailments of psych verbs are a mirror image of the logico-temporal entailments of telic COS verbs. The most relevant are tests diagnosing the visibility of end points. Following Smith (1997), Bar-el (2005), and Rozwadowska (2020), we use a selection of such tests below. Compare the opposite logico-temporal entailments with COS verbs and psych verbs in (29):

- (29)

- a.

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- czyścił

- clean.pst.imp

- buty

- shoes.acc

- aż

- until

- je

- them

- wyczyścił.

- clean.pst.perf

- ‘Mark was cleaning the shoes until he cleaned them.’

- b.

- Wiatr

- wind.nom

- suszył

- dry.pst.imp

- pranie

- laundry.acc

- aż

- until

- je

- it.acc

- wysuszył.

- dry.pst.perf

- ‘The wind was drying the laundry until it dried it.’

- c.

- Pranie

- laundry.nom

- suszyło

- dried.imp

- się

- rf

- na

- on

- słońcu,

- sun.loc

- aż

- until

- się

- rf

- wysuszyło.

- dried.perf

- ‘The laundry was drying in the sun until it dried.’

- d.

- #Nagroda

- prize.nom

- cieszyła

- please.pst.imp

- Marka,

- Mark.acc

- aż

- until

- go

- him

- ucieszyła.

- pleased.pst.perf

- ‘#The prize pleased/was pleasing Mark until it pleased him.’

- e.

- #Marek

- Mark.nom

- cieszył

- pleased.imp

- się

- rf

- nagrodą,

- prize.inst

- aż

- until

- się

- rf

- nią

- it.inst

- ucieszył.

- pleased.perf

- ‘#Mark was pleased with the prize until he started to be pleased with it.’

The corresponding logical entailments involving negation are illustrated in (30):

- (30)

- a.

- Marek

- wind.nom

- czyścił

- dried.imp

- buty,

- laundry.acc

- ale

- but

- ich

- it.acc

- nie

- not

- wyczyścił.

- dried.perf

- ‘The wind was drying the laundry, but it has not dried it.’

- b.

- Wiatr

- wind.nom

- suszył

- dried.imp

- pranie,

- laundry.acc

- ale

- but

- go

- it.acc

- nie

- not

- wysuszył.

- dried.perf

- ‘The wind was drying the laundry, but it has not dried it.’

- c.

- Pranie

- laundry.nom

- suszyło

- dried.imp

- się

- rf

- na

- on

- słońcu,

- sun.loc

- ale

- but

- się

- rf

- nie

- not

- wysuszyło.

- dried.perf

- ‘The laundry was drying in the sun, but it has not dried.’

- d.

- #Nagroda

- prize.nom

- cieszy(ła)

- pleased.imp

- Marka,

- Mark.acc

- ale

- but

- go

- him

- nie

- not

- ucieszyła.

- pleased

- ‘#The prize pleases/ed Mark but it did not start to please him.’

- e.

- #Marek

- Mark.nom

- cieszy(ł)

- pleased.imp

- się

- rf

- nagrodą,

- prize.inst

- ale

- but

- się

- rf

- nią

- it.inst

- nie

- not

- ucieszył.

- pleased.perf

- ‘#Mark is/was pleased with the prize, but he did not start to be pleased with it.’

The data above indicate that the beginning of the state marked by the perfective prefix is a necessary entailment with stative (imperfective) psych verbs, whereas the imperfective COS verb describes the change of state before it culminates, as summarized in (31):

- (31)

- a.

- COS verbs:

- imperfective at t does not entail perfective at t’ < t (ex. 30a,b,c)

- perfective at t entails imperfective at t’ < t (ex. 29a,b,c)

- b.

- Psych verbs:

- Perfective at t entails imperfective at t’ > t (ex. 29d, e)

- Perfective at t does not entail imperfective at t’ < t (ex. 29d,e)

- imperfective at t entails perfective at t’ < t (ex. 30d, e)

We explain this contrast by distinguishing left boundary (onset) of an eventuality from right boundary (set terminal point). Both are expressed by means of the perfective form, but with psych verbs the perfective form refers to the beginning of the state described by the verb, whereas with COS verbs, the perfective form refers to the termination point of the process of change described by the verb.

Another test used to check telicity and the visibility of the end point is culmination cancellation (see Bar-el 2005). Again, there is a difference between culminating complex events composed of the causing sub-event and the result state on one hand, and inceptive eventualities on the other hand.

- (32)

- Culmination cancellation: Y x–ed … but/and Y didn’t finish (x-ing)

- a.

- #Janek

- John.nom

- z-budował

- z-pfv-built.pst

- dom

- house.acc

- i/ale

- and/but

- nie

- not

- skończył/przestał

- finish/stop.3sg.pst.perf

- go budować.

- it build.inf

- ‘#Janek built a house, and/but didn’t finish/stop building it.’

- b.

- Językoznawstwo

- linguistics.nom

- za-fascynowało

- za.pfv-fascinate.pst

- Janka

- John.acc

- i

- and

- nie

- not

- przestało/*skończyło

- stop.3sg.pst.pfv

- go

- him

- fascynować.

- fascinate.inf.’

- ‘Linguistics started to fascinate John and didn’t stop to fascinate him.’

Example (32b) indicates that the alleged final point can be easily cancelled, thus is not visible in the event structure, in contrast to telic events with result states as in (32a). The absence of the end point is also evident from another contrast between (32a) and (32b). In Polish, there are two aspectual verbs related to the termination of an event: przestać ‘stop’ and skończyć ‘finish’. Culminating complex events are compatible with both these verbs, whereas non-culminating events only with przestać, (32b). Since psych verbs are compatible only with przestać, no culmination (i.e., no result) is ever entailed by the meaning of psych verb.12

Finally, let us construe one more test to diagnose the visibility of the initial point followed by a state, modeled on the tests used by Smith (1997) and Bar-el (2005) to diagnose culmination and end point. Perfective psych verbs entail the state that follows its initial boundary, i.e., its beginning, since the addition of any information to the contrary results in a contradiction, (33a). Sentence (33a) testifies to the visibility of the initial point followed by a state, because the cancellation of the continuation results in unacceptability. The lack of continuation is perfectly natural with COS verbs in (33b) and (33c), because here the perfective form refers to the end of the event, and not to its beginning.

- (33)

- a.

- #Składnia

- syntax.nom

- zainteresowała

- za.perf-interest.pst

- moich

- my

- studentów,

- students.acc

- więc

- so

- już

- anymore

- ich

- them

- nie

- not

- interesuje.

- interest.3sg.prs.imp

- ‘# Syntax started to interest my students, so it doesn’t interest them anymore.’

- b.

- Sąsiad

- neighbour.nom

- wybudował

- wy.perf-build.pst

- dom,

- house.acc

- więc

- so

- go

- it

- już

- anymore

- nie

- not

- buduje.

- build.3sg.prs.imp

- ‘The neighbour built the house, so he doesn’t build it anymore.’

- c.

- Suszarka

- dryer.nom

- wysuszyła

- wy.perf-dry.pst

- pranie,

- laundry.acc

- więc

- so

- go

- it

- już

- anymore

- nie

- not

- suszy.

- dry.3sg.prs.imp

- ‘The dryer dried the laundry, so it doesn’t dry it anymore.’

Sentences (29)–(33) demonstrate that perfective psych verbs code both the initial boundary triggering event and the subsequent state following it, thus behaving in a different way from COS verbs. The imperfective form of the psych verb is entailed by its perfective form, (33a), whereas the imperfective form of COS verbs (achievements or accomplishments) is not entailed by the perfective form, (33b, c). Let us now summarize the temporal and aspectual properties of Polish psych verbs and non-psych verbs discussed above in Table 1.

Logico-temporal tests of psych verbs and non-psych verbs.

| Tests | Psych verbs | Non-psych telic verbs: (accomplishments and achievements) | |

| 1. | Perfective at time t entails imperfective at time t’ < t Ex. (29–30) |

* | O.K. |

| 2. | Perfective at time t entails imperfective at time t’ > t Ex. (29–30) |

O.K. | * |

| 3. | Compatibility with the aspectual verb przestać ‘stop’ (32) | O.K. | O.K. |

| 4. | Compatibility with the aspectual verb skończyć ‘finish’(32) | * | O.K. |

| 5. | Visibility of the initial point (33) | O.K. | * |

Table 1 shows that psych verbs significantly differ from COS verbs in logico-temporal entailments, which strongly supports the conclusion that they are irreducible to COS verbs. Our view on the event structure of Polish psych verbs follows Rozwadowska (2012, 2020) and is similar to what Marín & McNally (2011) independently proposed for Spanish reflexive psychological verbs (cf. also Fritz-Huechante et al. 2018; Machicao y Priemer & Fritz-Huechante 2020). Marín & McNally suggest the existence of a possible semantics that refers to inchoativity without referring to change itself. In other words, it is imaginable that a predicate refers to the initial interval of a state (its onset) without referring to any prior interval before the state’s onset. According to them, that the state does not obtain before the onset is a matter of inference – not semantics, which is an entirely different view on inchoativity than the one that dominates in the literature. By examining logico-temporal entailments of Polish psych verbs, we have provided support for the claim that perfective forms of psych verbs refer to the beginning (onset) of a state without referring to the change itself, in contrast to COS verbs.

2.5 Interim summary

In Section 2, by comparing the realization of the non-experiencer participant vs. the realization of the causer in the anticausative alternation typical of COS verbs, we have provided evidence that the psych reflexive alternation in Polish cannot be subsumed under the causative/anticausative alternation and that the instrumental DP is not a causer but a T/SM. Moreover, we have shown on the basis of Polish EO/ES alternation that one cannot attribute the special properties of psych verbs to their aspectual ambiguity. Instead, we have argued that the EO/ES alternation in Polish is an alternation of its own kind, called the psych verb alternation after Rott et al. (2020). We have attributed the differences between the reflexive psych alternation and the causative/anticausative alternation to the fact that EO verbs are not COS verbs. This is because the event structure of EO verbs is not a sequence of a causing event culminating in a result state. Instead, they describe left bounded inceptive eventualities describing the beginning of an emotional state and its unbounded continuation. We have supported our view on the different event structures of psych verbs and COS verbs by appealing to the logico-temporal entailments of both verb classes.

3 A structural analysis of causative EO verbs and their ES cognates in Polish

In this section, we analyze the syntactic structure of eventive (causative) EO verbs in Polish and their ES alternants to check whether they are derivationally related by a syntactic rule. First, in Section 3.1, we scrutinize the structural position of the causer argument of eventive EO verbs. The position of the causer is crucial in determining the structural difference between EO verbs and their ES counterparts, presented in Section 3.3. In Section 3.2, we examine the structure of reflexive ES variants of eventive causative EO verbs. We first provide evidence that reflexive ES verbs in Polish are unergative, not unaccusative (Section 3.2.1). Then, we focus on the reflexive marker of ES verbs (Section 3.2.2), which corresponds to the reflexive marker of Polish anticausatives (cf. Section 2). We argue that with both reflexive ES verbs and anticausatives, się occupies the same structural position and has the same function. We also examine the structural position of the ES of alternating reflexive ES verbs in Polish. Finally, in Section 3.3, we provide the structure of causative EO verbs, which incorporates a part of the structure postulated for ES verbs. Since causative EO verbs and their ES counterparts share a part of their structure, we check whether there is a derivational relationship between these two types of psych verbs in Polish. Subsequently, we juxtapose the structures of EO/ES verbs with the structures of causative/anticausative predicates to account for the similarities and differences between the EO/ES alternation and the causative/anticausative alternation in Polish.

3.1 The structural position of the causer argument of Polish eventive EO verbs

Before examining the position of the causer argument of eventive EO verbs in Polish, let us focus on the structure of the verb phrase adopted in our analysis. We assume that within the verb phrase, there is a vP (Chomsky 1995) and a VoiceP (Kratzer 1996), merged above the vP. Voice introduces an external argument, assigns a theta role to it, and is the source of accusative case (Alexiadou et al. 2006; Pylkkänen 2008; Legate 2014). Voice values accusative when it is equipped with φ-features (Schäfer 2008). If Voice has no φ-features, it cannot value any case. Voice may also be expletive, viz. incapable of assigning a theta role (Schäfer 2008). This is the case in marked unaccusatives in a number of languages, including Polish (Bondaruk 2021a) (for details, cf. Section 3.3). The v head introduces an eventuality variable, and it verbalizes the root. The root provides the lexical semantics for the eventuality expressed by the verb phrase (Pesetsky 1995; Marantz 1997).

In the literature, the causer argument of causative EO verbs is placed either in Spec, VoiceP, like an agent argument, or in Spec, vP, as an event modifier, not an event participant different from the agent. The latter stance is strongly voiced in A&A (2019, 2020), who specify that causative EO verbs in Greek cannot co-occur with an agent argument and resist verbal passive. A&A (2019, 2020) emphasize that the availability of verbal passive is dependent on the presence of Voice. Consequently, the causer argument of Greek EO verbs cannot be merged in Spec, VoiceP, but must reside in Spec, vP; the Spec VoiceP being reserved only for agents.

Following A&A (2019, 2020), we assume that passivisation depends on the presence of Voice. Thus, if Polish eventive EO verbs can form verbal passive, as we shall see presently, we must conclude that their causer argument occupies Spec, Voice, not Spec, vP. Polish has two types of verbal passive, viz. (i) with the auxiliary zostać ‘become’ and the perfective passive participle, and (ii) with the auxiliary być ‘to be’ and the imperfective passive participle (Zabrocki 1981). Here, we only analyse perfective EO verbs, as they are unambiguously eventive (cf. Section 2.2), and therefore we only examine zostać ‘become’-passive, which contains the perfective passive participle. First, let us note that agentive EO verbs form verbal passive, (34), where the verb zaniepokoić ‘to bother.perf’ is passivised:

- (34)

- Lokatorzy

- residents.nom

- budynku

- building.gen

- zostali

- became

- zaniepokojeni

- bothered.perf

- przez

- by

- policję

- police

- ‘Residents of this building were bothered by the police.’

In (34), the agent argument is present in przez ‘by’-phrase. Eventive EO verbs in Polish can also form zostać ‘become’-passive, cf. (35) from the National Corpus of Polish Language (www.nkjp.l), which contains the same verb as (34), this time used with an eventive interpretation (for more instances of eventive EO verbs in the passive, cf. Bondaruk et al. 2017 and Bondaruk 2020b):

- (35)

- Lokatorzy

- residents.nom

- budynku

- building.gen

- zostali

- became

- zaniepokojeni

- bothered.perf

- hałasami

- noises.inst

- dochodzącymi

- coming

- z

- from

- jednego

- one

- z mieszkań.

- of flats

- ‘The residents of this building were bothered by the noises coming from one of the flats.’

The causer in the passive sentence in (35) is realised as an instrumental DP. However, the causer may also correspond to przez ‘by’-phrase, (36):

- (36)

- Lokatorzy

- residents.nom

- budynku

- building.gen

- zostali

- became

- zaniepokojeni

- bothered.perf

- przez

- by

- hałasy

- noises

- dochodzące

- coming

- z

- from

- jednego

- one

- z mieszkań.

- of flats

- ‘The residents of this building were bothered by the noises coming from one of the flats.’

The EO verb passivized in (34)–(36) has the reflexive ES counterpart, (37), where the instrumental DP functions as a T/SM, not a causer (cf. Section 2.3):

- (37)

- Lokatorzy

- residents.nom

- budynku

- building.gen

- zaniepokoili

- bothered.perf

- się

- rf

- hałasami

- noises.inst

- dochodzącymi

- coming

- z

- from

- jednego

- one

- z mieszkań.

- of flats

- ‘The residents of this building got bothered with the noises coming from one of the flats.’

Since eventive EO verbs in Polish can form verbal passive like agentive EO verbs, we must conclude that both types of EO verbs contain a Voice layer in their structure, with the agent and the causer placed in the same structural position, i.e. the specifier of VoiceP (for different structural positions of agents and causers in Catalan resultative passive and Spanish extent verbs, cf. Crespi, and Gibert-Sotelo & Marín, this volume, respectively). In Section 3.3, we will show that the Spec, VoiceP position of the causer of eventive EO verbs bears on the structural difference between eventive EO verbs and their ES cognates in Polish.

3.2 The structure of reflexive ES alternants of Polish causative EO verbs

In this section, we first address the question whether monadic reflexive ES alternants of causative EO verbs are unaccusative or unergative (Section 3.2.1). Subsequently, we examine the function of the reflexive marker się, and the structural position of the ES (Section 3.2.2).

3.2.1 Monadic reflexive ES verbs in Polish are unergative not unaccusative

Monadic ES cognates of causative EO verbs have been treated as either unaccusative (Belletti & Rizzi 1988; Pesetsky 1995; A&I) or unergative (Reinhart 2002; Marelj 2004; Rákosi 2006). Here, we examine whether monadic ES alternates, (38), of causative EO verbs, (39), in Polish, represent unaccusative or unergative predicates.

- (38)

- Marek

- Mark.nom

- zdenerwował

- annoyed

- się.

- rf

- ‘Mark got annoyed.’

- (39)

- Wysokie

- high

- koszty

- costs.nom

- utrzymania

- living

- zdenerwowały

- annoyed.perf

- Marka.

- Mark.acc

- ‘High living costs annoyed Mark.’

A number of tests have been proposed to distinguish unaccusative from unergative verbs. Some of them either do not apply to Polish or do not yield conclusive results (for an overview of the tests and their applicability to Polish, cf. Bondaruk 2020a). Therefore, we will only concentrate on those tests which shed some light on the unaccusative or unergative status of monadic ES verbs in Polish like (38) above. The majority of the tests adopted here come from Cetnarowska (2000, 2002).

The first unaccusativity diagnostic relates to impersonal passives in -no/-to, which are felicitous with unergatives, but not with unaccusatives, as in (40) and (41) from Cetnarowska (2002: 64).

- (40)

- *Wyrośnięto

- grew-up_to.perf

- w

- in

- atmosferze

- atmosphere.loc

- terroru.13

- terror.gen

- unaccusative

- ‘They grew up in an atmosphere of terror.’

- (41)

- Zadzwoniono

- phoned_no.perf

- po

- for

- lekarza.

- doctor.acc

- unergative

- ‘They phoned for a doctor.’

The monadic ES verb zdenerwować się ‘to get annoyed’ in (38) above, may be used in -no/-to impersonals, (42), thus patterning like an unergative predicate in (41) and unlike an unaccusative verb in (40):

- (42)

- Zdenerwowano

- got_annoyed_no.perf

- się.

- rf

- ‘They got annoyed.’

The second unaccusativity test concerns distributive po-phrases (cf. Pesetsky 1982 for a similar test adopted for Russian). These phrases are felicitous with objects of transitive verbs, (43).

- (43)

- Kupiliśmy

- bought.1pl

- po

- po

- książce.

- book.loc

- ‘We bought a book each.’

This test is also applicable to derived subjects of some unaccusative verbs, (44):14

- (44)

- Z

- from

- każdej

- each

- klasy

- class

- przyszło

- came

- po

- po

- rodzicu.

- parent.loc

- ‘There came a parent from each class/grade.’ (Cetnarowska 2000: 41)

In contrast, unergative verbs are much less acceptable with po-phrases, as can be seen in (45):

- (45)

- ?*Z

- from

- każdej

- each

- klasy

- class

- zadzwoniło

- phoned

- do

- to

- szkoły

- school

- po

- po

- rodzicu.

- parent.loc

- ‘A parent from each class/grade phoned the school.’ (Cetnarowska 2000: 41)

The distributive po-phrases test applied to monadic ES variants of causative EO verbs leads to ungrammaticality, (46):

- (46)

- *Z

- from

- każdej

- each

- klasy

- class

- zdenerwowało

- got_annoyed.perf

- się

- rf

- po

- po

- uczniu.

- pupil.loc

- ‘A pupil from each class got annoyed.’

The ungrammaticality of (46) indicates that monadic reflexive ES verbs pattern like unergatives, (45), not like unaccusatives, (44).

The third unaccusativity diagnostic, adopted after Cetnarowska (2000, 2002), involves na- and po-prefixed verbs (cf. Pesetsky 1982 and Schoorlemmer 1995 for a similar test applied to Russian). Na- and po-prefixed verbs can quantify over their objects, as in (47), where the phrase książek ‘books’ surfaces in the partitive genitive case:

- (47)

- Nakupili

- na_bought.3pl

- książek.

- books.gen

- ‘They have bought a lot of books.’

These prefixed verbs can also quantify over the sole argument of an unaccusative verb if the verb refers to appearance or movement, (48):15

- (48)

- Narosło

- na_grew

- chwastów. (Cetnarowska 2002: 59)

- weeds.gen

- ‘There have grown so many weeds.’

In contrast, prefixed unergative verbs do not license the partitive genitive, (49):

- (49)

- *Naśpiewało

- na_sang

- dzieci

- children.gen

- w

- in

- naszym

- our

- bloku. (Cetnarowska 2002: 59)

- block

- ‘There have sung so many children in our block of flats.’

Monadic ES variants of causative EO verbs may be prefixed with na- or po-, (50):

- (50)

- Nadenerwowało

- naannoyed

- się

- rf

- ludzi.

- people.gen

- ‘*A lot of people got annoyed.’

However, (50) differs from (48), because it lacks the interpretation ‘A lot of people got annoyed’, corresponding to the one in (48). It only has the impersonal meaning, viz. “Somebody made many people annoyed”. Thus, this test allows us to draw only the negative conclusion, namely that monadic ES verbs in Polish differ from unaccusatives but tells us nothing about their alleged unergative status. All in all, the diagnostics presented in this section indicate that monadic ES alternants of causative EO verbs in Polish do not pattern like unaccusative, but rather like unergatives.

3.2.2 The structural position of the reflexive marker and the ES of reflexive ES verbs in Polish

In this section, we first focus on the syntactic function of the reflexive marker of alternating ES verbs. The same reflexive marker occurs with reflexively marked anticausatives (cf. (52) below), and we will argue in Section 3.3 that się has the same function in these two types of structure. Subsequently, we examine the structural position of the ES with reflexive ES verbs, and propose the structure of reflexive ES verbs.

The reflexive marker się represents a SE-type anaphor in Reinhart and Reuland’s (1993) typology. Się is multifunctional, since it appears in a number of structures, including reflexive verbs, (51), reflexively marked anticausatives, (52), and antipassives, (53) (Saloni 1975; Laskowski 1984; Kupść 2000; Rivero & Milojević Sheppard 2003; Fehrmann et al. 2010; Krzek 2013; Bondaruk 2021b).

- (51)

- Ewa

- Eve.nom

- myje

- washes

- się

- rf

- wieczorem.

- evening.inst

- ‘Eve washes in the evening.’

- (52)

- Drzwi

- door.nom

- otworzyły

- opened

- się.

- rf

- ‘The door opened.’

- (53)

- Ten

- this

- chłopak

- boy.nom

- się

- rf

- bije.

- hits

- ‘This boy hits others.’

The reflexive marker of reflexive ES verbs in Polish cannot have the reflexive function, because reflexive structures like (51), have two theta roles – an agent and a theme – where the theme is identified with the agent (e.g. via bundling as in Reinhart & Siloni 2004), whereas reflexive ES verbs realise just one – experiencer theta role, (54):

- (54)

- Ewa

- Eve.nom

- zdenerwowała

- annoyed.perf

- się

- rf

- wieczorem.

- evening.inst

- ‘Eve got annoyed in the evening.’

Sentence (54) has an inceptive interpretation, according to which Eve started to feel annoyed in the evening. The inceptive meaning in (54) is associated with the perfective prefix z-, attached to the verb denerwować ‘to annoy’, and does not depend on się. To obtain the reflexive interpretation in (54), się must be replaced with the SELF-type anaphor siebie, (55):

- (55)

- Ewa

- Eve.nom

- zdenerwowała

- annoyed.perf

- siebie

- rf

- (samą).

- (emph)

- ‘Eve made herself annoyed.’

Sentence (55) sounds natural only if the anaphor siebie is accompanied by the emphatic element samą. In (55), Eve is no longer an experiencer, but an agent or causer that triggers annoyance in herself.

Beside the reflexive function, SE-type anaphors, including the reflexive marker się, may also serve as valency reducing operators suppressing an argument of the predicate (Reinhart & Siloni 2004; Fehrmann et al. 2010, i.a.). The reflexive marker się suppresses an external argument in reflexively marked anticausatives, (52). As noted in Section 2, reflexively marked ES variants of eventive EO verbs cannot co-occur with the causer argument, they can only appear with the T/SM argument. We would like to argue that się blocks the realization of causer argument with reflexive ES cognates of eventive EO verbs, in the same way as it blocks the realization of an external argument with anticausatives. However, there is an important difference between reflexive ES verbs and anticausatives in that the former are unergative (Section 3.2.1), while the latter are unaccusative (for details, cf. Section 3.3).

Willim (2020: 238) argues that the reflexive marker of alternating ES verbs in Polish has an antipassive function, because reflexive ES verbs can either appear without an internal argument, (56), or with an oblique instrumental, (57), but they can never co-occur with an accusative case-marked internal argument, (57). In antipassives, się detransitivises the predicate by either suppressing an internal argument (cf. (53) above) or by shifting it to an oblique (Polinsky 2005: 438).

- (56)

- Ewa

- Eve.nom

- zdenerwowała

- annoyed.perf

- się

- rf

- ‘Eve got annoyed.’

- (57)

- Ewa

- Eve.nom

- zdenerwowała

- annoyed.perf

- się

- rf

- (utratą

- loss.inst

- pieniędzy)

- money.gen

- /*utratę

- *loss.acc

- pieniędzy.

- money.gen

- ‘Eve got annoyed with the loss of money.’

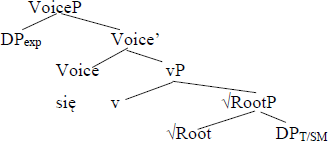

Willim (2020) proposes that się with reflexive ES verbs realizes an active Voice as in (58):

- (58)

In (58), the experiencer acts as an external argument filling Spec, VoiceP, the reflexive się is merged in Voice, and the instrumental case marked T/SM argument (cf. (57) above) merges directly with the root.

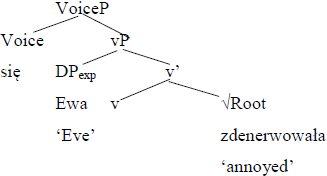

Following Willim (2020), we take się of ES verbs to fill the Voice position (cf. (58)). However, we will argue that the ES does not occupy Spec, VoiceP, but rather a lower Spec, vP position. After Tollan (2018), we assume that unergative subjects may be merged lower than transitive subjects, viz. in Spec, vP, not in Spec, VoiceP. Tollan (2018), who focuses primarily on Samoan, argues that not only unergatives project an external argument in Spec, vP, but also a number of ES verbs. She specifies that an external argument in Spec, VoiceP and the one in Spec, vP share the property of either initiating or experiencing an event. However, the two types of external argument exhibit some differences. The external argument in Spec, VoiceP shows the following properties: (i) it triggers an effect upon another entity, (ii) it brings about a change of state, (iii) it is effortful, (iv) it is volitional, and (v) it concludes an event (Tollan 2018: 17). The external argument in Spec, vP, in turn, (i) does not affect another entity or is physically affected, and (ii) it does not bring about or undergo a change of state (Tollan 2018: 17). The properties typical of external arguments in Spec, vP also characterize ESs of reflexive ES verbs. First, the ES is not physically affected nor does it affect another entity. To prove this, we can use the affectedness test, mentioned by Tollan (2018: 15), based on the ‘what happened to X is Y’ diagnostic (Cruse 1973), which can be adapted to Polish as in (59):16

- (59)

- a.

- – Co

- what

- się

- rf

- stało

- happened

- Ewie?

- Eve.dat

- ‘What happened to Eve?’

- b.

- – Ewa

- Eve.nom

- przewróciła

- fell.down.perf

- się.

- rf

- ‘Eve fell down.’

- c.

- – #Ewa

- Eve.nom

- zdenerwowała

- annoyed.perf

- się.

- rf

- (=(56))

- ‘Eve got annoyed.’

Only (59b) with an unaccusative verb and an affected subject is a felicitous answer to the question in (59a), whereas (59c) with a reflexive ES verb is infelicitous in this context, which indicates that the ES subject of reflexive ES verbs is not physically affected. Likewise, the ES of reflexive ES verbs in Polish does not bring about or undergo a change of state. As has been observed for (54) above, reflexive ES verbs have an inceptive interpretation (in contrast to culminating affected interpretation), according to which the ES starts to perceive a particular emotion (annoyance in (54)–(56)) and no change of state is involved. (see Section 2.4). The COS interpretation is typical of internal arguments – patients or themes (Dowty 1991), (59b). Moreover, Tollan (2018: 17–19) notes that unlike external arguments placed in Spec, VoiceP, external arguments in Spec, vP do not conclude the event, and hence participate in events that are atelic, viz. lacking endpoints. This observation is also valid for Polish psych verbs in general (cf. Rozwadowska 2020), including reflexive ES verbs (see Section 2.4).

Since ESs of reflexive ES verbs in Polish show all the properties that Tollan (2018) posits for external arguments placed in Spec, vP, we propose the following structure for Polish reflexive ES verbs like (56) above:

- (60)

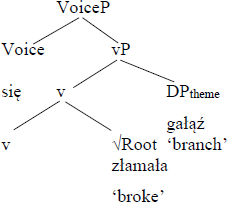

In (60), the ES occupies Spec, vP, and the reflexive się is merged in Voice.17 The structure with an external argument in Spec, vP, similar to the one in (60), is proposed for antipassives by Oikonomou & Alexiadou (2022). Kovačević (2021) argues that the ES of reflexive ES verbs in Serbian occupies Spec, vP, with the reflexive marker filling the Voice head, analogously to our analysis in (60).

Summarising, alternating ES verbs in Polish have an unergative structure in (60) above, with the experiencer in a low external argument position, viz. Spec, vP, as proposed for unergatives and some psych predicates in Samoan by Tollan (2018). As we shall see in Section 3.3, the low position of experiencers opens up a possibility for a uniform treatment of ES and EO, and for a novel structural account of eventive EO verbs in Polish.

3.3 Are causative EO verbs and their reflexive ES variants derivationally related in Polish?

In this section, we first examine the structure of eventive EO verbs in Polish. Then, we compare it with the structure of reflexive ES verbs from Section 3.2.2 (cf. (60)) to check whether these two predicate types are derivationally related. Finally, we juxtapose the structure of EO/ES verbs with the structure of causative/anticausative predicates to highlight the similarities and differences between these two alternation types.

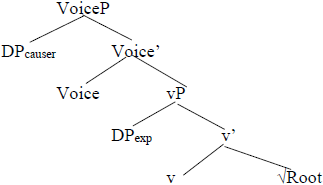

As argued in Section 3.1, the causer argument of eventive EO verbs in Polish occupies Spec, VoiceP. We propose that the structure of eventive EO verbs incorporates a part of the structure of reflexive ES verbs, provided in (60), and it looks as follows:18

- (61)

In (61), the EO of eventive EO verbs occupies the same structural position as the ES of reflexive ES verbs in (60), viz. Spec, vP. This allows us to maintain the same structural position for the two types of experiencer, in conformity with the UTAH. The structures in (60) and (61) contain the same unergative vP, and they only differ at the Voice level. Whereas the Voice of reflexive ES verbs is filled with the reflexive marker się, (60), it is empty in the case of eventive EO verbs, (61). The reflexive marker się in (60) is defective since it lacks φ-features,19 and once it merges in Voice, the Voice is deprived of φ-features, and therefore it cannot value accusative. In (60), the ES in Spec, vP gets its theta role from v, not from Voice; consequently, the Voice in (60) is expletive (non-thematic). However, in (61) the Voice is thematic, and it assigns the causer role to its specifier. The Voice in (61) has unvalued φ-features and an accusative case feature. It enters into Agree with the experiencer, whereby it has its φ-features valued, and it values the case feature of the experiencer as accusative.

Since eventive EO verbs, (61), and their reflexive ES alternants, (60), share the vP layer, they have a common base (cf. A&I and Hirsch 2018, for a similar conclusion concerning the EO/ES alternation in Greek, Romanian and German). However, despite sharing the common base, eventive EO verbs and their ES cognates in Polish are not derivationally related by a syntactic rule, because neither of the two variants can be taken as the basic one. The two variants clearly differ at the Voice level – the Voice is expletive in reflexive ES verbs and thematic in eventive EO verbs; so the EO/ES alternation boils down to a different type of Voice projected above the same vP.

On the surface our analysis seems to be similar to Reinhart’s account (2002), in which eventive EO verbs and their unergative ES counterparts are derivationally related in the lexicon by decausativisation, viz. an operation that removes a causer from the lexical entry of the verb. The structure of eventive EO verbs, (61), has a causer argument, which is missing in the corresponding ES structure, (60). However, we do not relate the absence of the causer in (60) to any lexical rule, but to the presence of a special kind of Voice, the expletive one, filled by the reflexive marker się which cannot introduce a thematic argument whatsoever.

Our account is different from Pesetsky’s (1995) analysis, in which eventive EO verbs are derived from reflexive ES counterparts. In Pesetsky’s (1995) account, EO verbs are derived from reflexive ES verbs in French, Italian and Russian, which are unaccusative (cf. footnote 17), by attaching the zero CAUS morpheme to the verb root, which then makes the reflexive marker disappear. Pesetsky (1995: 121) argues that the reflexive marker must disappear when the CAUS affix is added to the verb, (62a), because then the reflexive (the A-Causer in Pesetsky’s terminology) fails to be c-commanded by the experiencer, (62b):

- (62)

- a.

- Le bruit étonne-CAUS Marie.

- b.

- *Le bruit s’étonne-CAUS Marie.

- (Pesetsky 1995: 121)

(62b) is ungrammatical because the reflexive is c-commanded by the causer, not by the experiencer. (62a), in turn, is perfectly licit, as it contains no reflexive marker. Pesetsky’s (1995) account cannot be applied to Polish, because reflexive ES verbs in Polish are not unaccusative, but unergative (cf. Section 3.2.1). Hence, the derivation proposed by Pesetsky (1995), in which the ES originates VP-internally, like the EO, and subsequently moves to Spec, IP/TP (cf. footnote 17) cannot be maintained for Polish.