1 Introduction

Wechsler (1999) attempts to provide an argument against GB and Minimalist approaches to syntax based on the so-called “Balinese Bind,” which concerns the binding of complex reflexives in Balinese, an Austronesian language.1 Wechsler observes that promotion of an argument to subject position does not create new antecedents for binding in simple transitive constructions; within a GB/Minimalist framework, this suggests that the landing site for Balinese subjects, which I identify as Spec,TP, comprises an A’-position.2 However, in raising constructions, the raised subject does appear to be a potential antecedent for binding, suggesting that Spec,TP is in fact an A-position, leading to a potential paradox.

The problem is illustrated as follows. Like many Austronesian languages, Balinese exhibits two transitive voice markings: Agentive Voice (AV), in which the external argument is promoted to what appears to be a subject (SVO word order), and Objective Voice (OV), in which the internal argument is promoted (OVS word order).3 AV is marked with a phonologically conditioned nasal prefix, as in (1a), while the OV is morphologically unmarked, as in (1b):

- (1)

- a.

- Tiang

- 1

- ngatap

- av.cut

- biu

- banana

- ‘I cut a banana.’

- b.

- Biu

- banana

- gatap

- ov.cut

- tiang

- 1

- ‘I cut a banana.’

In AV, a complex reflexive that is coreferent with its coargument must be post-verbal; it cannot be pre-verbal, as seen in (2a)–(2b). In OV, the reflexive must instead appear pre-verbally; it cannot be post-verbal, as shown in (2c)–(2d). For Minimalism, this suggests that Spec,TP is not an A-position in Balinese, such that binding conditions must be satisfied before movement:4

- (2)

- a.

- Ayui

- Ayu

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ‘Ayui pinched herselfi.’

- b.

- *Awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- Ayui

- Ayu

- (Lit.) ‘Shei pinched Ayui.’

- c.

- Awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- jimpit

- ov.pinch

- Ayui

- Ayu

- (Lit.) ‘Shei pinched Ayui.’

- d.

- *Ayui

- Ayu

- jimpit

- ov.pinch

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ‘Ayui pinched herselfi.’

However, in raising constructions with the verb ngenah ‘seem’ (which does not undergo the AV/OV alternation) the raised subject appears able to bind an anaphor within an optional experiencer-PP adjoined to the matrix clause, as in (3). In such constructions, which I will henceforth refer to as Balinese Bind constructions, it thus appears that Spec,TP is an A-position after all, such that raising to Spec,TP does create new possibilities for anaphoric binding:

- (3)

- Ayui

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui seemed to herselfi to be very ugly.’

Comparing simple transitive cases with raising constructions, it looks as though Spec,TP is both an A- and A’-position in Balinese. According to Wechsler (1999), this seeming contradiction poses a serious problem for proponents of a GB/Minimalist approach to binding. On the other hand, Wechsler claims that the distribution of Balinese anaphors can be accounted for straightforwardly within HPSG, concluding that the latter framework is therefore empirically superior.5

My primary goal is to present and discuss the implications of the properties of Balinese anaphora. Based on a wealth of novel data, I show that the complex anaphor awakne seen above can receive a logophoric interpretation in the absence of an overt local binder, the possibility of which previous work on the Balinese Bind does not explore. I believe the fact that awakne must be interpreted logophorically in (3) to be the key to unraveling the Balinese Bind. I motivate an account of the Balinese Bind that incorporates the insights of Charnavel’s (2020) theory of logophoricity, building on Udayana (2013), who was the first to note awakne’s logophoric properties.6

I provide one illustrative unacceptable example of logophoricity at play in (4) below, indicating that awakne must be obligatorily read de se in this construction.

- (4)

- Non-de se context: Ayu is very drunk at a weekend party at her friend’s house. She sees a portrait of herself that her friend has hanging up, and calls the woman in the portrait ugly, though she does not realize that she is the woman in the photo.

- #Ayu

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awak-ne

- self-poss.3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayu seemed to herself to be very ugly.’

Furthermore, I make the novel observation that Balinese anaphora contradict a long-standing generalization in the literature that if a language has both simplex and complex anaphors, then the complex anaphor cannot receive a long-distance interpretation; this generalization is stated most clearly by Haspelmath (2008). I show that Balinese anaphors behave the opposite way: simplex anaphors must be interpreted locally while complex anaphors may have logophoric, long-distance antecedents in any syntactic context.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents tests from Charnavel (2020) to establish that awakne can be logophorically licensed, and extends them to the Balinese Bind construction. Based on these findings, I argue that awakne is obligatorily logophoric in this context. Section 3 presents a formal account of the Balinese Bind, and Section 4 discusses further implications of the data, including the aforementioned generalization. Section 5 concludes.

2 The Data

I introduce the reader to Charnavel’s (2020) framework of logophoricity in 2.1, which gives us various empirical tests to determine the presence of a perspectival center. Extending these tests to Balinese, in 2.2, I establish that awakne may optionally be interpreted logophorically. In 2.3, I turn my attention to the Balinese Bind construction, and I make the argument that the reflexive in that context must be anteceded by a perspectival center.

2.1 Background on empirical tests for logophoricity

It has long been noted in the literature that there are contexts in which anaphors are clearly subject to Chomsky’s (1986) Condition A, according to which anaphors must be bound within their local domain.7 Such a context is illustrated in (5) with an example from Charnavel and Sportiche (2016:37(2)), who refer to well-behaved anaphors as in (5a) as plain anaphors:

- (5)

- a.

- [The moon]i spins on itselfi.

- b.

- *[The moon]i influences [people sensitive to itselfi].

On the other hand, it has likewise been observed–by Ross (1970), Kuno (1972), Bouchard (1985), Lebeaux (1985), Pollard & Sag (1992) and Reinhart & Reuland (1993) among many others–that there are circumstances in which anaphors appear to not be subject to Condition A. For example, himself can be bound by David, though under any definition of locality, David is the farthest possible antecedent for the anaphor in (6):

- (6)

- Davidi said to Mary that nobody would believe linguists like himselfi.

Seemingly exceptional anaphors such as himself in (6) are referred to as exempt anaphors (cf. Pollard & Sag (1992), Charnavel & Sportiche (2016), Charnavel (2020). Charnavel (2020) provides a phase-based account of why, in so many languages, plain and exempt anaphors are phonetically identical despite apparent differences in their licensing conditions.

She argues that, contrary to appearances, plain and exempt anaphors are one and the same: though lacking an overt local antecedent, exempt anaphors are locally bound by a phonetically null logophoric pronoun, prolog, that is identified with the individual whose perspective is adopted by the speaker. Hence, even seemingly exceptional anaphors satisfy Condition A, albeit covertly.

In support of this proposal, Charnavel observes that exempt reflexives are necessarily animate.8 For example, notice that (5b) improves significantly if the moon is replaced with an animate subject in (7a). A similar contrast is observed in (7b) and (7c), where I see that the newspaper cannot antecede a reflexive in the embedded clause despite being a source of information:

- (7)

- a.

- Trumpi influences [people sensitive to himselfi].

- b.

- Caitlin learned from Johni that there was a story about himselfi on TV.

- c.

- *Caitlin learned from [the newspaper]i that there was a story about itselfi on TV.

The effect of animacy is explained under Charnavel’s hypothesis: because only animate individuals are potential perspectival centers, only animate reflexives can be bound by prolog. Crucially, though animacy is a necessary condition for logophoric binding, it is not sufficient. Charnavel (2020) makes two empirical generalizations:

- (8)

- a.

- An exempt anaphor must be anteceded by an attitude holder or an empathy locus. This is its logophoric antecedent.

- b.

- The constituent containing an exempt anaphor has to express the first-personal perspective of its antecedent. This is its logophoric domain.

Further details of this hypothesis will be provided in section 3.1. Important for the present is Charnavel’s taxonomy for exemption (i.e., logophoric binding), given in Table 1 below:

Taxonomy for exemption.

| Logophoric antecedent | Logophoric domain | Tests |

| Attitude holder | De se attitude | First-person morphology Anti-attitudinal epithets Double orientation |

| Empathy locus | First-personal perception | Emphatic ‘his dear’ |

I now present some illustrative examples–from Charnavel & Zlogar (2015)–of some tests from Table 1 applied to English, beginning with tests targeting logophoric binding by an attitude holder. Consider example (9), in which the reflexive himself is neither local to nor c-commanded by its (overt) antecedent, John, but is acceptable.

- (9)

- According to John, the article was written by Anne and himself. Kuno (1987), p. 121

The first, known as the epithet test, is inspired by Dubinsky & Hamilton’s (1998) observation that epithets–for instance, the idiot–cannot corefer with the perspectival center associated with the context in which the epithet occurs. This is because epithets must reflect an attitude of the speaker, and not the attitude holder. Charnavel and Zlogar demonstrate that epithets may be used to detect antecedence by an attitude holder, defining the epithet test as follows:

- (10)

- Epithet test: Replace the exempt anaphor with a co-referring epithet and check whether the sentence becomes unacceptable.

As (11) shows, substitution of the reflexive in (9) with a co-referring epithet renders the sentence unacceptable. This is because the antecedent of the reflexive, John, is an attitude holder, and the clause containing the reflexive expresses John’s de se attitude towards the writing of the article.

- (11)

- *According to John, the article was written by Ann and the idiot.

The result of the epithet test is corroborated by another test proposed by Charnavel and Zlogar, the double orientation test, which they define as in (12):

- (12)

- Double Orientation Test: Replace the exempt anaphor with an evaluative expression and check whether it can be evaluated by both the speaker and the antecedent.

This test derives from the fact that an evaluative expression–for example, a good woman–can be evaluated from the perspective of an attitude holder rather than the speaker if it occurs within an attitudinal context associated with that attitude holder. Charnavel and Zlogar apply this test to the sentence in (9) as shown in (13), noting that the author may be great in the eyes of either the speaker or the attitude holder, John.

- (13)

- According to John, the article was written by Anne and a great author.

In addition to the epithet and double-orientation tests, antecedence by an attitude holder can also be diagnosed by determining whether the anaphor must be read de se. Obligatory de se interpretations have often been cited as a property of logophors by Huang & Liu (2001), Anand (2006), Charnavel & Zlogar (2015) and Charnavel (2020), among others. Charnavel & Zlogar (2015) show with the example in (14) that the anaphor in (9) becomes unacceptable in a context that does not support a de se reading:

- (14)

- John is looking at a research article that he co-wrote with Ann many years ago, but does not recognize it as one of his own papers. Instead, he falsely assumes that Ann’s co-author is a colleague of his who happens to have the same name as him.

- #According to Johni, the article was written by Ann and himselfi.

Attitude holders are only one sort of perspectival center identified by Charnavel (2020) as a potential antecedent for seemingly exempt anaphora; as stated in the generalization in (8), empathy loci may likewise license exemption in some languages. First, to see why attitude holders are not sufficient, note that the following sentence from Charnavel & Zlogar (2015) in (15a) passes the epithet test in (15b), indicating that his in (15a) is not an attitude holder:

- (15)

- a.

- Hisi computer screen-saver features a picture of himselfi kissing a fish.

- b.

- Hisi computer screen-saver features a picture of [the idiot]i kissing a fish.

The idea of an empathy locus was first presented by Kuno (1987) based on data from Japanese, who defines it as follows:

- (16)

- Empathy Locus: the event participant that the speaker identifies with or empathizes with (in other words, takes the mental perspective of).

As Charnavel & Zlogar (2015) note, this is a technical definition which is not to be confused with informal notions such as ‘pity’ or ‘sympathy.’ Kuno noted that empathy loci may be present with non-attitude verbs such as yaru and kureru, meaning ‘give.’ According to Kuno, these verbs encode different points of view from each other: in the case of yaru, the giving event is from the perspective of the subject, while in the case of kureru the event is from the perspective of the receiver. According to Kuno, this explains the distribution of yaru and kureru in (17a)–(17b) below:

- (17)

- a.

- Boku-ga

- I-nom

- Hanako-ni

- Hanako-dat

- okane-o

- money-acc

- [*kure-ru/ya-ru]

- give-prec

- ‘I give money to Hanako.’

- b.

- Taroo-ga

- Taroo-nom

- boku-ni

- me-dat

- okane-o

- money-acc

- [kure-ru/*ya-ru]

- give-pres

- ‘Taroo gives me money.’

Let us turn back to reflexives. Reflexives anteceded by empathy loci occur in the absence of intensional operators and, as demonstrated by Charnavel & Zlogar (2015), behave differently than attitudinal anaphors with respect to the epithet and double orientation tests. Consider the English contrast in (18)–(19) from Charnavel & Zlogar (2015).

- (18)

- Anonymous posts about herself on the internet hurt Lucy’s feelings.

- (19)

- *Anonymous posts about herself on the internet hurt Lucy’s popularity.

The presence of the psychological expression Lucy’s feelings in (18) allows the speaker to have empathy for Lucy, whereas this is not possible with a non-psychological expression such as (19). As a result, Lucy can be an antecedent for the anaphor in (18) but not (19).

We find that the reflexive in (18) may be replaced with a co-referring epithet. Hence, Lucy does not appear to refer to an attitude holder in (18).

- (20)

- Anonymous posts about the idiot hurt her feelings.

Nevertheless, Lucy’s first-personal perspective is adopted by the speaker in uttering (18). This is revealed by Charnavel & Zlogar’s beloved test, defined as in (21a) and deployed in (21b). (21c) is once again ruled out because Lucy’s popularity is a non-psychological expression:9

- (21)

- a.

- Beloved Test: Replace the exempt anaphor by his/her beloved NP and check whether the sentence is acceptable (under a non-ironic reading).

- b.

- Anonymous posts about her beloved son on the internet hurt Lucy’s feelings.

- c.

- *Anonymous posts about her beloved son on the internet hurt Lucy’s popularity.

In the sections that follow, I apply these tests to Balinese, in order to determine whether Balinese complex reflexives may likewise be exempt if and only if they take a logophoric antecedent and, if so, which sorts of logophoric antecedents are relevant to Balinese.

2.2 Balinese complex anaphors as potentially logophoric

I show that awakne can be anteceded by either an overtly local antecedent, whether animate or inanimate, or by the perspectival center of the sentence–the availability of which depends on discourse and syntactico-semantic factors, as detailed in Charnavel (2020) (cf. Anand (2006)). These findings lay the groundwork for section 2.3, in which I argue that reflexive experiencers are bound not by the raised subject in raising constructions but, rather, are necessarily anteceded by a perspectival center.

As is common of anaphors in many languages, all anaphors in Balinese are derived from words meaning body.10 I focus on the reflexives derived from the low register awak. Following Haiduck (2014), I take for granted that the third person complex anaphor is made of the possessive suffix -ne and the simplex anaphor. Unspecified for number, awakne can have either singular or plural antecedents.

I begin by establishing that awakne exhibits both plain and exempt behavior, just like English herself. As shown in (22a)–(22d), awakne is compatible with both animate and inanimate antecedents when Condition A is overtly satisfied, i.e., when it is bound locally by an overt DP:

- (22)

- a.

- Injil

- Bible

- ngrujuk

- av.reference

- awak-ne

- self-poss.3

- ‘The Bible references itself.’

- b.

- Yesus

- Jesus

- ngrujuk

- av.reference

- awak-ne

- self-poss.3

- ‘Jesus references himself.’

- c.

- Ayu

- Ayu

- demen

- happy

- ajak

- with

- foto-n

- photo-lnk

- awak-ne.

- self-poss.3

- ‘Ayu likes a picture of herself.’

- d.

- Buku-ne

- Book-def

- misi

- contain

- foto-n

- photo-lnk

- awak-ne.

- self-poss.3

- ‘The book contains a picture of itself.’

As shown in (23b), awakne can also appear in the absence of an overt local binder. Crucially, as captured in the contrast between (23a) and (23b), this is possible only if the antecedent of awakne is animate. Inanimate awakne must have an overt local binder, even in a position that permits exemption, consistent with what we observed in English above.

- (23)

- a.

- *Injili

- Bible

- nglalahin

- av.influence

- anak

- person

- sane

- rel

- kenyih

- sensitive

- teken

- to

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ‘The Biblei influences people who are sensitive to itselfi.’

- b.

- Yesusi

- Jesus

- nglalahin

- av.influence

- anak

- person

- sane

- rel

- kenyih

- sensitive

- teken

- to

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ‘Jesusi influences people who are sensitive to himselfi.’

Hence, controlling for animacy as in Charnavel & Sportiche (2016) and Charnavel (2020), we find that Balinese awakne is plain when its antecedent is inanimate but can be exempt when its antecedent is animate. Crucially, it is not the case that animacy is a sufficient condition for apparent exemption. In (24), we find that animate awakne requires a perspectival center:

- (24)

- [Bapan

- Father

- Ayuj]I

- Ayu

- sing

- neg

- nemen-in

- av.like-appl

- awak-nei,*j,*k

- self-poss.3

- ‘Ayuj’s fatheri does not like himselfi,*j,*k.’

As predicted under Charnavel’s hypothesis, we observe that awakne can optionally have a long-distance antecedent when it can be construed as a perspectival center, as in (23b). As observed already by Udayana (2013), apparent exemption is also permitted for animate awakne when it appears in an attitudinal context created by an intensional verb such as ngaden ‘think’:11

- (25)

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ngaden

- think

- Ayuj

- Ayu

- nanjung

- av.kick

- awak-nei,j

- self-poss.3

- ‘Nyomani thinks Ayuj kicked him/herselfi,j.’

Charnavel (2020) observes that while split antecedents are not licensed for plain anaphors, both are possible with exempt anaphors. we find that awakne can take a split antecedent in logophoric contexts, as predicted:12

- (26)

- Ayui

- Ayu

- ngorahin

- av.told

- Nyomanj

- Nyoman

- awak-nei+j

- self-poss.3

- lakar

- will

- malaib

- run

- ‘Ayui told Nyomanj that theyi+j will run.’

Long-distance interpretations of awakne are unavailable if the intended antecedent is not construed as the perspectival center associated with the domain in which the reflexive occurs. Consider the contrast in binding possibilities shown in (27a) and (27b). In (27a), we find that awakne can be anteceded by the subject of ngorahin ‘tell,’ whereas antecedence by the indirect object is dispreferred. Conversely, in (27b) we see that antecedence by the subject of ningeh uli ‘hear from’ is dispreferred. This is because the source of information is the object Arta and not the subject Nyoman. Antecedence by Ayu is fully acceptable (Udayana (2013)):

- (27)

- a.

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ngorahin

- av.tell

- Artaj

- Arta

- Ayuk

- Ayu

- nanjung

- av.kick

- awak-nei,*j,k

- self-poss.3

- ‘Nyomani told Artaj that Ayuk kicked him/herselfi,*j,k.’

- b.

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ningeh

- av.hear

- uli

- from

- Artaj

- Arta

- Ayuk

- Ayu

- nanjung

- av.kick

- awak-ne

- self-poss.3*i,j,k

- ‘Nyomani heard from Artaj that Ayuk kicked him/herself*i,j,k.’

The pattern that emerges from the examples in (27a)–(27b) are consistent with the long-standing observation that sources of information are more likely perspectival centers than recipients of information (Sells (1987), Udayana (2013), i.a.). When the source of information is not expressed, as in (28), antecedence by the recipient becomes possible:13

- (28)

- Iai

- 3

- ningeh

- av.hear

- cangj

- 1

- gedeg

- angry

- teken

- with

- awak-nei/*j

- self-poss.3

- ‘(S)he heard that I was angry with him/her.’ (Udayana 2013: p.199)

What sorts of antecedents can license logophoric binding? Consider again the example in (25). Uttered in a context in which Ayu is very drunk and has unknowingly kicked herself, coreference between awakne and Ayu is nevertheless perfectly acceptable, revealing that awakne need not be read de se if bound by an overt local antecedent.

- (29)

- Ayu is very drunk, and she accidentally kicked herself thinking it was someone else.

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ngaden

- think

- Ayuj

- Ayu

- nanjung

- av.kick

- awak-nej

- self-poss.3

- ‘Nyomani thinks Ayuj kicked herselfj.’

But we find that awakne must be read de se if its antecedent is not overtly local, for instance when anteceded by Nyoman in (25). This is made apparent by the unacceptability of coreference between awakne and Nyoman when (25) is paired with a non-de se context as in (30):

- (30)

- Nyoman heard that Ayu accidentally kicked someone who had fallen asleep at a party. While he thinks this is true, he doesn’t realize that he was the one who had fallen asleep.

- #Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ngaden

- think

- Ayuj

- Ayu

- nanjung

- av.kick

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ‘Nyomani thinks Ayuj kicked himselfi.’

The de se requirement is also observed of awakne in (31)–(32a), in which the reflexive appears as the subject of the clausal complement of ngorahang ‘say’:14

- (31)

- Ayu sees a picture of herself, and is pleased by how beautiful she is.

- Ayui

- Ayu

- ngorahang

- av.say

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- (ngenah)

- (seem)

- jegeg

- beautiful

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui said that shei looks very beautiful.’

(31) is infelicitous in a context like (32a)’s, according to which Ayu does not realize that she is the girl in the photo who she thinks is beautiful:

- (32)

- Ayu sees a picture taken at a party. She remarks that one of the girls in the photo looks very beautiful, but she doesn’t realize that she is the girl in the photo.

- a.

- #Ayui

- Ayu

- ngorahang

- av.say

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- (ngenah)

- (seem)

- jegeg

- beautiful

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui said that shei looks very beautiful.’

The de se requirement for long-distance antecedence in (25)–(32a) suggests that the antecedent is in both cases an attitude holder, and that the reflexive falls in a de se attitudinal domain.

This conclusion is further supported by application of the tests for antecedence by an attitude holder summarized in Table 1. Applying the double orientation test to the Balinese example in (32a), we find that the evaluative expression in (33a) can indeed be evaluated by the antecedent rather than the speaker. This is made apparent in the acceptability of a continuation that expresses a contradictory opinion on the part of the speaker, as in (33b).

- (33)

- a.

- Ayu

- Ayu

- ngorah-ang

- av.said-appl

- anak

- person

- sane

- rel

- masolah

- behave

- becik

- good

- jegeg

- beautiful

- sajan…

- very

- ‘Ayu said that a good person is very beautiful…’

- b.

- …nanging

- …but

- tiang

- 1

- ngerasa

- feel

- anak-e

- person-def

- ento

- dem

- tusing

- neg

- masolah

- behave

- becik.

- good

- ‘…but I think that person isn’t good.’

Likewise extending the epithet test to Balinese by building upon (31), we observe that substitution of awaknewith a coreferent epithet is impossible:

- (34)

- *Ayui

- Ayu

- ngorahang

- av.say

- [idiot-e

- idiot-def

- ento]I

- dem

- (ngenah)

- (seem)

- jelek

- ugly

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui said that the idioti looks very ugly.’

I thus conclude that attitude holders can antecede logophoric reflexives in Balinese.15

It is worth observing also that, just as in English (cf. (7c)) and French (Charnavel (2020)), sourcehood is not sufficient to license apparent exemption from Condition A (pace Sells (1987)). In particular, inanimate sources such as surat kabar ‘newspaper’ cannot antecede overtly non-local reflexives, as shown in (35).

- (35)

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ningeh

- av.hear

- uli

- from

- [surat

- document

- kabar]j

- news

- Ayuk

- Ayu

- nanjung

- av.kick

- awak-ne

- self-poss.3

- ‘Nyomani heard from [the newspaper]j that Ayuk kicked him/herself*i,*j,k.’

I now discuss the possibility of empathy loci licensing apparent exemption from Condition A in Balinese. Consider the examples in (36a) and (36b):

- (36)

- a.

- Komen

- comment

- sane

- rel

- jelek

- mean

- indik

- about

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ring

- on

- Instagrame

- ngae

- av.make

- Ayui

- Ayu

- sebet.

- sad

- ‘Mean comments about herself on Instagram made Ayu sad.’

- b.

- Indik

- that

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- awak-nei,j

- self-poss.3

- ngae

- av.make

- Ayuj

- Ayu

- gedeg

- mad

- ‘That Nyomani pinched himselfi/herselfj annoyed Ayuj.’

Here again we find awakne in the absence of an overt local binder; in fact, the reflexive in both cases lacks a c-commanding antecedent entirely. But like English herself, awakne does not fall within the scope of an overt intensional expression in (36a) or (36b). Moreover, Charnavel (2020) argues from English and French data that the subjects of psych-verbs and equivalent psychological constructions do not express the attitude of their object. Is awakne therefore anteceded by an empathy locus rather than attitude holder in these examples?

Applying the tests introduced above, we find that awakne actually does appear to be anteceded by an attitude holder. Illustrating with (37), we find that substitution of awakne with a co-referential epithet is not possible:

- (37)

- *Indik

- that

- Nyoman

- Nyoman

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- [idiot-e

- idiot-def

- ento]j

- dem

- ngae

- av.make

- Ayuj

- Ayu

- gedeg

- mad

- ‘That Nyoman pinched [the idiot]j annoyed Ayuj.’

An evaluative expression in the same context can be evaluated from the perspective of Ayu rather than the speaker, as shown by the compatibility of (38a) with the continuation in (38b):

- (38)

- a.

- Indik

- that

- Nyoman

- Nyoman

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- anak

- person

- masolah

- behave

- becik

- good

- ngae

- av.make

- Ayu

- Ayu

- gedeg…

- mad

- ‘That Nyoman pinched a good person made Ayu mad…’

- b.

- …nanging

- but

- tiang

- 1

- ngerasa

- feel

- ia

- 3

- tusing

- neg

- masolah

- behave

- becik

- good

- ‘…but I think (s)he is not a good person.’

These findings suggest that Balinese contrasts with English and French in that individuals may be identified as attitude holders even without intensional expressions. They also leave open the question of whether antecedence by an empathy locus is ever possible for exempt anaphors in Balinese. I leave further investigation of both points for future research.

Finally, there appear to be cases in which awakne behaves as a pronoun. For at least one of the native speakers I have consulted, awakne does have the appearance of a pronoun in certain contexts, namely when its referent is previously established as the topic of conversation:16

- (39)

- Tiang

- 1

- ningeh

- av.hear

- kabar

- news

- indik

- about

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- … awak-nei

- … self-poss.3

- demen

- like

- ajak

- with

- Ayu

- Ayu

- ‘I heard something about Nyomani … hei likes Ayu.’

Note in this case that the referent of awakne, Nyoman, is not likely the source of the information that follows. In fact, as we see in (40), matrix subject awakne cannot refer to an established source if a disjoint individual is established as topic:

- (40)

- Artai

- Arta

- ngorahin

- av.tell

- tiang

- 1

- kabar

- news

- indik

- about

- Nyomank … awak-ne*i/k

- Nyoman … self-poss.3

- demen

- like

- ajak

- with

- Ayu

- Ayu

- ‘Artai told me something about Nyomank … he*i/k likes Ayu’

It seems that a separate licensing mechanism for awakne may be available in Balinese in addition to logophoricity, for instance binding by a null topic. Additional data is needed to adjudicate between these options.

2.3 The Balinese Bind Construction

Having established the distributive properties of awakne, I would now like to look at the Balinese Bind construction, repeated in (41).17

- (41)

- Ayui

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui seemed to herselfi to be very ugly.’

I have shown that awakne does not always require an overt local binder, in particular when it is anteceded by a perspectival center. This observation alone is sufficient to weaken Wechsler’s claim that Balinese Bind constructions present a paradox for GB/Minimalism, as it is possible for awakne to appear in such constructions without being bound by the raised subject. This is exemplified in (42), in which awakne is anteceded by the overtly non-local attitude holder Nyoman.

- (42)

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ngaden

- think

- Ayuj

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awak-nei/j

- self-poss.3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan

- very

- ‘Nyomani thinks Ayuj seemed to himselfi/herselfj to be very ugly.’

However, in this section I make a stronger claim. I argue that when awakne is an experiencer in a raising construction, it is never a plain anaphor bound by the raised subject. Rather, it is always logophoric. I begin by observing that the reflexive experiencer is available even in the absence of raising. Indeed, as shown in (43), this is exactly what we find: given the context and questions in (43a) and (43b), one can answer with (43c).

- (43)

- Context: Arta took a photo of Ayu and Nyoman. Ayu doesn’t like the way she looks in the photo, so she hid the photo in the closet.

- a.

- What does Ayu think of the photo?

- b.

- Why did Ayu hide the photo?

- c.

- Ngenah

- Seem

- sig

- to

- awak-ne

- self-poss.3

- ia

- 3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- (lit.) ‘It seems to herself that she is very ugly.’

Moving on, although I will introduce the properties of the simplex anaphor awak in further detail in section 4.1, I will show that it can never be interpreted logophorically. I therefore predict that it cannot be present as an experiencer in this construction. This prediction is borne out:

- (44)

- *Ayui

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awaki

- self

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- (lit.) ‘Ayui seemed to herselfi to be very ugly.’

Another piece of evidence is that the reflexive experiencer must be read de se. Consider for example the unacceptability of (41) when paired with the context in (45).

- (45)

- Ayu is very drunk at a weekend party at her friend’s house. She sees a portrait of herself that her friend has hanging up, and calls the woman in the portrait ugly, though she does not realize that she is the woman in the photo.

- #Ayu

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awak-ne

- self-poss.3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayu seemed to herself to be very ugly.’

Crucially, the unacceptability of (45) does not arise from the incompatibility of the proper name with the perspective of the experiencer. This is made apparent in (46a)–(46b), which demonstrates that both de dicto (46a) and de re (46b) interpretations are available for the raised subject; in the latter case, Ayu does not recognize Nyoman as the person who strikes her as unattractive in the photo–just as she does not recognize herself in the context in (45)–and yet the DP Nyoman is still felicitous.

- (46)

- Ayu is looking through photos from a party last weekend. In one photo she recognizes Nyoman, who she thinks is very handsome. In another is someone she doesn’t recognize, but who seems to be unattractive. In fact, the person in the other photo was also Nyoman!

- a.

- Nyoman

- Nyoman

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- Ayu

- Ayu

- ganteng

- handsome

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Nyoman seems to Ayu to be very handsome.’

- b.

- Nyoman

- Nyoman

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- Ayu

- Ayu

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Nyoman seems to Ayu to be very ugly.’

I therefore conclude that (45) is ruled out because the reflexive must receive a de se reading: it cannot be used in a context in which the referent does not recognize herself. Recall from section 2.1 that de se readings are obligatory only for exempt anaphors. If awakne could be locally bound by the subject in Spec,TP, then we would expect the de se interpretation to be optional, in which case (45) would be acceptable, contrary to fact. Hence, the de se requirement observed in Balinese Bind constructions reveals that awakne must be exempt in this context: licensed by antecedence by a perspectival center rather than overt local binding.

This conclusion is supported by the double orientation test. As mentioned previously, evaluative expressions that fall within an attitudinal domain can be evaluated by either the speaker or by the attitude holder; in all other contexts, only evaluation by the speaker is available. Consider a context in which Ayu thinks that a certain individual who holds a negative opinion of her appearance is a good person, whereas the speaker considers this same individual to be a bad person. Both (47a) and (47b) can be felicitously uttered:

- (47)

- a.

- Ayu

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- anak

- person

- bagus

- good

- ento

- dem

- jelek

- bad

- sajan

- very

- ‘Ayu seems to a good man to be very ugly.’

- b.

- Ayu

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- anak

- person

- jelek

- bad

- ento

- dem

- jelek

- bad

- sajan

- very

- ‘Ayu seems to a bad man to be very ugly.’

The final piece of evidence is the epithet test, which I predict to be unacceptable, and it is:

- (48)

- *Ayui

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- [idiot-e

- idiot-def

- ento]i

- dem

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui seemed to the idioti to be very ugly.’

I conclude that reflexive experiencers in Balinese Bind constructions are necessarily co-referent with a perspectival center, in particular an attitude holder. It may be surprising to find binding by an attitude holder in this context, since the experiencer-PP does not fall within the scope of an overt intensional operator. I provide a tentative discussion of this puzzle in section 3.4.

3 Untangling the Balinese Bind

After having provided the empirical basis for the solution, I now focus on its theoretical aspects. Section 3.1 introduces the theoretical formulation of Charnavel’s account of logophoric binding. 3.2 provides a theoretical account of the Balinese Bind: appealing to covert logophoric binding allows me to sidestep the issue of whether Spec,TP is an A- or A’-position. 3.3 discusses Levin’s (2014) solution to the paradox, concluding that his account does not predict the interpretative constraints on awakne. 3.4 compares and contrasts with reflexive experiencers in English.

3.1 Background Assumptions

As noted above, Charnavel (2020) argues that it is not coincidental for plain and exempt anaphors to be identical in all the languages that she discusses. For her, plain and exempt anaphors are one and the same: they both must have local antecedents, and the various properties of exempt anaphors–namely, their availability to take partial, split, and long-distance antecedents–are an illusion. The appearance of exemption rather arises from optional binding by a covert logophoric pronoun that syntactically realizes the perspectival center associated with the content of the domain containing the anaphor. She thus adopts the formulation of Condition A given in (49).

- (49)

- Phase-based formulation of Condition A:

- An anaphor must be bound within its smallest Spell-Out domain.

According to Charnavel, every Spell-Out domain optionally contains a logophoric projection on top, LogP, headed by a perspectival operator OPLOG. This operator licenses a covert logophoric pronoun, prolog, as its specifier and requires that its complement, schematized as P in (50a), is compatible with the first-personal perspective of the referent of prolog, as captured in the denotation in (50b). The intuition behind this is that each phase can be specified as being presented from the perspective of a certain individual:

- (50)

- a.

- [LogP prolog-i OPLOG [P …logophori… ]]

- b.

- ⟦ OPLOG ⟧ = λP.λx: P from x’s first-personal perspective

I schematize the difference between plain and exempt anaphors below, where Ph0 refers to a phase head, and XP is the Spell-Out domain of Ph0 in (51b), and LogP is the Spell-Out domain in (51a). This is to illustrate the very similar syntactic structure between the two, where the only difference between an exempt and plain anaphor is the binder: the former is covertly locally bound by a perspectival center while the latter is still locally bound, but not by prolog. It should be noted that, like other forms of pronouns, including covert pro, prolog does not require a local binder.

- (51)

- a.

- Exempt anaphor: [PhP Ph0 [LogP prolog-i OPLOG [XP … exempt anaphori …]]]

- b.

- Plain anaphor: [PhP Ph0 [XP … DPi … plain anaphori …]]

Before we turn to the Balinese Bind, it is important to first account for the distribution of reflexives in simple transitive sentences. Recall from section 1 data which is repeated in (52a)–(52d) below: complex reflexives like awakne must be post-verbal in AV, but pre-verbal in OV:

- (52)

- a.

- Ayui

- Ayu

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ‘Ayui pinched herselfi.’

- b.

- *Awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- Ayui

- Ayu

- (Lit.) ‘Shei pinched Ayui.’

- c.

- Awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- jimpit

- ov.pinch

- Ayui

- Ayu

- (Lit.) ‘Shei pinched Ayui.’

- d.

- *Ayui

- 3

- jimpit

- ov.pinch

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- ‘Ayui pinched herselfi.’

Following Charnavel & Sportiche (2016) and Charnavel (2020), I assume that reflexives must be bound within the minimal Spell-out domain containing them. To account for the binding pattern in (52a)–(52d), I adopt a variant of Levin’s (2014) account of the Austronesian voice alternation, which itself is based on Aldridge (2008).

Levin and Aldridge adopt Baker’s (1988) Uniformity of Theta-Assignment Hypothesis (UTAH), according to which external arguments (EA) are always generated as the specifier of the verb, such as Spec,vP, while internal arguments (IA) are always generated as its complement. The sentences (53a)–(53b) below have the same syntactic structure at one point in the derivation:

- (53)

- a.

- Tiang

- 1

- ngatap

- av.cut

- biu

- banana

- ‘I cut a banana.’

- b.

- Biu

- banana

- gatap

- ov.cut

- tiang

- 1

- ‘I cut a banana.’

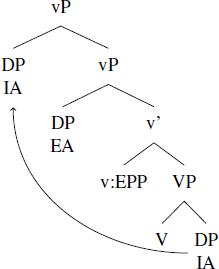

Both voices also have in common an additional movement step of the IA to Spec,vP above the EA, as illustrated in the tree (54) below. For Levin, this movement is driven by an EPP feature on v.

- (54)

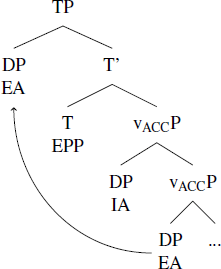

The difference between the two voices is Case assignment. AV clauses are argued to be similar to English, in that v0 in AV assigns accusative case to the IA (vACC). But v0 in OV (vERG) does not assign ergative case to either the IA or EA. This means that the IA in OV will remain an Active goal in the sense of Chomsky (2001) and hence available for probing by higher functional heads, such that the IA is able to move to Spec,TP. Levin, following Baker (1985), assumes that the post-verbal EA incorporates to avoid the Case Filter. By contrast, when accusative case is assigned to the IA in AV, it is rendered Inactive for further probing by higher functional heads, and only the EA may move to Spec,TP. This is illustrated in the trees (55)–(56) below:

- (55)

- OV derivation

- (56)

- AV derivation

I now move on to the raising construction.18

3.2 The Solution

Recall the Balinese Bind construction, repeated in (57) below:

- (57)

- Ayui

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui seemed to herselfi to be very ugly.’

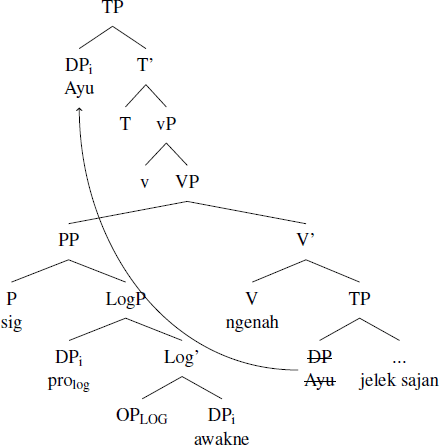

We have two choices regarding the position of the logophoric projection and the perspectival center, given that there are two Spell-Out domains under Ayu. The first possibility is the Spell-Out domain of P, which is DP. This is in light of Citko’s (2014) claim that PPs–with or without subjects–may also comprise phases. Though the phasehood of P may be less certain, this is the choice that I will make, represented in (58) below.

- (58)

The second possibility is to place the logophoric projection on top of the Spell-Out domain of v, which is VP. This possibility is schematized in below:

- (59)

- [TP Ayui … [vP [LogP prolog-i OPLOG [VP [PP sig awaknei] [V’ ngenah [TP ti jelek sajan]]]]]

This is problematic. Recall that I am agnostic as to whether Spec,TP in Balinese is an A- or A’-position. If it is an A’-position, then as an anonymous reviewer has pointed out, this would lead to a strong crossover violation. In order to overcome this problem, one would have to stipulate certain conditions of invisibility to Charnavel’s perspectival center, which would be stipulatory. By contrast, (58) does not instantiate even a weak crossover structure, so it is preferable.

Ultimately, however, I would like to note that my solution of the Balinese Bind paradox does not hinge on the technical machinery of Charnavel’s proposal. The key point I am making is simply that the empirical observation of the logophoricity of awakne is the key to unraveling the paradox. Awakne is obligatorily interpreted logophorically in the Balinese Bind construction. As an anonymous reviewer has suggested, a solution in which awakne receives a value from a sufficiently discourse-prominent element due to its logophoric properties would also be sufficient. I have only taken for granted Charnavel’s framework in this paper is because it is the most well-developed in the generative literature thus far. As long as my empirical observation is made, I believe that the paradox can be straightforwardly untangled in GB or Minimalist frameworks.

In short, I propose that the licensing of reflexive experiencers in the Balinese Bind construction arises not from binding by the raised subject but, rather, by a null logophoric pronominal located within the Spell-Out of PP. These constructions do not contradict the observation that binding from Spec,TP is otherwise not possible. Let us now look at previous solutions.

3.3 Previous GB/Minimalist solutions to the Balinese Bind

Within the GB/Minimalist framework, a prima facie solution to the paradigm presented in (52a)–(52d) is to posit that only θ-roles are relevant for binding. Notice that in the paradigm presented in (52a)–(52d) above, the receiver of the Agent θ-role is always the binder of the reflexive, and the reflexive itself is the Theme. Indeed, another solution of the Balinese Bind could be to posit an account in which reflexive binding in Balinese is based on θ-roles. This is precisely what Travis (1998; 2012) suggests: A-positions which assign θ-roles allow binding whereas ones which do not assign θ-roles do not allow binding.

Levin (2014) points out an empirical argument against this idea, however. Spec,TP in both voices appears to be an A-position–at least in control constructions. Notice that in Balinese control constructions, as shown in (60a)–(60d), pre-verbal objects cannot be present in the embedded clause regardless of whether the embedded verb is AV or OV. PRO of course must occupy a T-position, as PRO was originally posited due to violations of the θ-Criterion:

- (60)

- a.

- Tiang

- 1

- edot

- want

- pro

- pro

- periksa

- ov.examine

- dokter.

- doctor

- ‘I want to be examined by a doctor.’

- b.

- *Tiang

- 1

- edot

- want

- dokter

- doctor

- periksa

- ov.examine

- pro.

- pro

- ‘I want to examine a doctor.’

- c.

- Tiang

- 1

- edot

- want

- pro

- pro

- meriksa

- av.examine

- dokter.

- doctor

- ‘I want to examine a doctor.’

- d.

- *Tiang

- 1

- edot

- want

- dokter

- doctor

- meriksa

- av.examine

- pro.

- pro

- ‘I want to be examined by a doctor.’

It could of course be possible for Travis to further argue that Spec,TP is a θ-position in embedded OV constructions, in contrast with matrix OV. However, as Levin points out, this sort of move would render a mixed-status analysis less plausible–as it would amount to saying that Spec,TP is a T-position whenever it needs to be, which is not a satisfying solution.

Taking up the task of defending Minimalist binding approaches against the objections raised by Wechsler (1999), Levin (2014) proposes a solution to the Balinese Bind that incorporates his proposal for Balinese voice alternation outlined above with the Agree-based anaphor licensing mechanisms put forth by Rooryck & Vanden Wyngaerd (2011) (R&W). Levin’s account sidesteps the issue of whether Spec,TP is an A- or A’-position in Balinese by positing that binding takes place lower in the syntax of raising constructions. In particular, Levin argues that reflexive binding in Balinese uniformly occurs within vP, whether in AV, OV, or raising constructions.

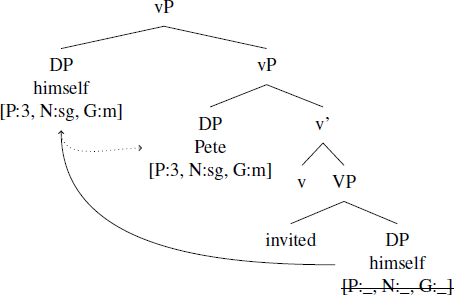

An illustrative tree of a derivation of the sentence Pete invited himself from Rooryck & Vanden Wyngaerd (2011) is given in (61) below; the anaphoric element raises to an adjoined position such as Spec,vP, at which point the anaphor ends up c-commanding its antecedent (and subsequent short movement of the verb above vP, and the EA above the anaphor, which is not shown):

- (61)

This may seem counterintuitive at first glance. The unvalued φ-features on the anaphor cause it to probe the antecedent that it ends up c-commanding, and its features are valued. At LF, the nominal that was valued during the derivation is interpreted as bound. As noted by R&W, this proposal does not immediately extend to complex anaphors within PPs, as these anaphors do not c-command their antecedent at any point in the syntactic derivation. To account for such cases, R&W propose that the anaphor covertly moves out of the PP at PF in order to adjoin to a position from which it can probe its antecedent.

Levin extends R&W’s approach to Balinese binding. He first proposes that the IA raises to a specifier of vP, as shown in 3.1. From there, an anaphoric IA c-commands the EA, allowing it to probe the EA in order to check its unvalued φ-features. The binding relationship is thus established between two elements, each of which are in Spec,vP, prior to T even being Merged, thereby obviating need to appeal to Spec,TP as a potential locus of binding. This correctly predicts the effect of voice alternation on the surface distribution of reflexives seen in (52a)–(52d), since binding is established within vP prior to promotion of the pivot to Spec,TP.

In order to account for binding in raising constructions, Levin compares the Balinese Bind construction to (62). If the PP in (62) above were to undergo movement to Spec,vP and above the EA, the anaphor would be unable to value its φ-features as it is too far embedded:

- (62)

- Tim looked at himself in the mirror.

According to R&W, the anaphor in (62) covertly moves outside of the PP and adjoins to Spec,vP, c-commanding the EA. This is precisely what Levin proposes for the Balinese Bind construction, as well: the reflexive experiencer moves covertly to a position that c-commands the embedded subject, allowing it to check its unvalued features before raising occurs.

Levin’s proposal is able to handle the data that have previously appeared in literature discussing the Balinese Bind. But Levin makes no mention of logophoric interpretations of Balinese complex anaphors, which are available even when the anaphor is a syntactic object–which I believe any analysis of the Balinese Bind construction must include. Indeed, there is one case in which our respective accounts make distinct predictions, which was presented previously in (43c). I predict the reflexive experiencer to be available in the absence of raising, and it is:

- (63)

- Context: Arta took a photo of Ayu and Nyoman. Ayu doesn’t like the way she looks in the photo, so she hid the photo in the closet.

- a.

- What does Ayu think of the photo?

- b.

- Why did Ayu hide the photo?

- c.

- Ngenah

- Seem

- sig

- to

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- iai

- 3

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- ‘(lit.) It seems to herself that she is very ugly.’

By contrast, Levin (2014) does not predict that binding would be possible in (63). The embedded clause in (63) appears to be full and finite and therefore a phase, as evidenced by the overt pronoun that has been licensed as the subject of the embedded clause.19 Awakne is not able to agree with its “antecedent” which it c-commands, given the phase barrier between the two. Agreement between awakne and its “antecedent” is made even less likely by the fact that Levin adopts a very strict conception of the Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) following R&W, in which elements within the c-command domain of the phase head become unavailable for probing as soon as the specifier of the phase is Merged.

Indeed, the strictness of the PIC leads to undesirable consequences more generally. As an anonymous reviewer notes, it is not clear how Levin’s approach can derive binding within finite embedded clauses in which the anaphor is a subject, as seen in example (31) above, repeated in (64) below. There is no mechanism under Levin’s framework for the anaphor to move out of the full and finite embedded phase.

- (64)

- Ayui

- Ayu

- ngorahang

- av.say

- awak-nei

- self-poss.3

- (ngenah)

- (seem)

- jegeg

- beautiful

- sajan.

- very

- ‘Ayui said that shei looks very beautiful.’

To conclude, these approaches do not shed further light on the properties of Balinese anaphora, and do not make further predictions of their own: they are technical fixes. My account is at an advantage here.20

3.4 Reflexive experiencers in English

Even so, multiple questions still remain open to future research. As an anonymous reviewer points out, perhaps the most pressing problem is the syntax and semantics of the seem-construction in both Balinese and English. Unlike Balinese, in English, it seems that the reflexive experiencer can never be logophorically bound. One test that helped to establish the presence of a perspectival center do not work in English; the reflexive cannot be read long-distance. Based on this approach to Balinese, I would predict English to behave similarly, but it doesn’t:

- (65)

- *John thinks that Lisa seems to himself to be very happy.

Also recall the obligatory de se test seen in (45) previously. When we use this test for such constructions in English, we find that although the context-sentence pair in Balinese was not acceptable, it was acceptable to the native English speakers that I consulted:

- (66)

- Ayu is very drunk at a weekend party at her friend’s house. She sees a portrait of herself that her friend has hanging up, and calls the woman in the portrait ugly, though she does not realize that she is the woman in the photo.

- Ayu seems to herself to be very ugly.

Similarly to Balinese, though, myself is not possible in this position:

- (67)

- *Lisa seems to myself to be very happy.

That the anaphor is not logophorically bound in such cases in English does not change the fact that anaphor in the Balinese Bind construction is logophorically bound in Balinese. Rather than being a problem for my analysis, I believe that this is an instance of crosslinguistic variation. It appears that a perspectival center is present in such constructions in Balinese but not in English. This would account for the differences between these languages we have just seen above.

Indeed, I predict that Balinese is not the only language which allows logophoric licensing with complex anaphors in this context. And this prediction is borne out. Turkish raising constructions behave similarly to Balinese ones, in which the simplex anaphor kendi is not allowed:

- (68)

- Handei

- Hande

- Zeynepk

- Zeynep

- [kendi-si]i/k-ne

- self-poss.3-to

- çirkin

- ugly

- görün-üyor

- seem-pres.3

- de-di.

- say-pst.3

- ‘Handei said that Zeynepk seems to herselfi/k to be ugly.’

Just like Balinese, in this context, it is not possible for a pronoun to occur instead of the logophoric anaphor; it must be interpreted as a free pronoun in (69):

- (69)

- Handei

- Hande

- Zeynepk

- Zeynep

- o*i/*k/j-na

- self-poss.3-to

- çirkin

- ugly

- görün-üyor

- seem-pres.3

- de-di.

- say-pst.3

- (Lit.) ‘Handei said that Zeynepk seems to her*i/*k/j to be ugly.’

At the very least, Turkish demonstrates that this problem is not unique to Balinese. But I must leave further technical details of the difference between Turkish and Balinese on one hand, and English on the other, to future research, although I provide one potential avenue below.21

One possibility is to determine whether there are constraints on Charnavel’s mechanism for logophoric binding. Recall that under her framework a perspectival center can be inserted inside every Spell-Out domain. The difference between Balinese and Turkish vs. English seems to demonstrate that this is too strong: there are at least some Spell-Out domains in which a perspectival center cannot be inserted, and it can vary across languages.22 Perhaps PP in raising constructions allows the insertion of LogP in Turkish and Balinese but not English. I must leave why this is so for future work, however.

4 The simplex anaphor awak

Although I have proposed a novel solution to the Balinese Bind paradox, this does not yet conclude our discussion of Balinese anaphora. The simplex anaphor awak has been neglected in the literature on the Balinese Bind construction, even though it is an important piece of the puzzle. In 4.1, I present awak’s basic properties and its limited distribution, and compare it to the related Indonesian simplex anaphor diri. In 4.2, I argue that Balinese contradicts a long-standing generalization in the literature regarding long-distance reflexives and monomorphemicity, showing the literal opposite of the expected pattern: the long-distance reflexive must be complex while the simplex anaphor must be read locally.

4.1 Awak as a potential reflexivizer

We have so far seen the properties of complex anaphors like awakne. It has not been noted in works discussing the Balinese Bind construction, such as Wechsler (1999) or Levin (2014) that Balinese also has simplex anaphors like awak. This anaphor cannot occur in this construction:

- (70)

- *Ayui

- Ayu

- ngenah

- seem

- sig

- to

- awaki

- self

- jelek

- bad

- sajan.

- very

- (lit.) ‘Ayui seemed to herselfi to be very ugly.’

Given that this is directly relevant to untangling the Balinese Bind, I will now provide a discussion of awak.

In these works, awakne has been glossed as ‘self,’ and the possessive and definite suffixes left unanalyzed. Awak is not specified for φ-features such as person, number or gender, and it can occur with any kind of subject binder. Furthermore, it has a very limited distribution; it is almost always restricted to the direct object, right-adjacent position of certain AV verbs:

- (71)

- a.

- Ayui

- Ayu

- nyimpit

- av.pinch

- awaki

- self

- ‘Ayui pinched herselfi.’

- b.

- *Awaki

- self

- nyimpit

- AV.pinch

- Ayui

- Ayu

- (Lit.) ‘Shei pinched Ayui.’

- c.

- *Awaki

- self

- jimpit

- ov.pinch

- Ayui

- Ayu

- (Lit.) ‘Shei pinched Ayui.’

- d.

- *Ayui

- 3

- jimpit

- OV.pinch

- awaki

- self

- ‘Ayui pinched herselfi.’

It cannot undergo coordination, indicating its clitic-like properties:23

- (72)

- *Ia

- 3

- nyimpit

- AV.pinch

- awak

- self

- teken

- with

- Nyoman

- Nyoman

- ‘(S)he pinched herself and Nyoman.’

The verbs that it can occur with are what Udayana (2013) calls high transitivity verbs like nyimpit ‘pinch’, which usually assign agent and theme θ-roles. It cannot be present as the object of a low transitivity verb like nepukin ‘see’. This is because such verbs bear experiencer and stimulus arguments; the stimulus object argument is not affected by the action of the verb. But it appears that as long as the experiencer of an AV verb is experiencing strong emotions, awak can be licensed. Thus, it is in fact possible to have awak as the object of a verb like love or hate. This indicates that awak is not always restricted to agent-theme verbs:

- (73)

- a.

- *Cangi

- I

- nepukin/ningeh

- AV.see/AV.hear

- awaki.

- self

- ‘I heard/saw myself.’

- b.

- Arta

- Arta

- ngedegin

- AV.hate

- awak.

- self

- ‘Arta hated himself.’

The only exception to the almost consistent distribution of awak–the object position of high transitive AV verbs–is that it can sometimes appear in the oblique position of a low transitive, non-AV verb. This violates both of the restrictions discussed above: right-adjacency and high-transitivity. This is illustrated below:

- (74)

- Ia

- She

- inget

- remember

- teken

- with

- awak

- self

- nista.

- poor

- ‘She had strong awareness of being poor.’ Udayana (2013) (p. 162)

Udayana suggests that this is acceptable because this implies that the referent of awak is experiencing strong emotions due to being poor. If we replace nista ‘poor’ with something like labuh ‘to fall’ or telat ‘late’ the complex anaphor must instead be used. This is perhaps because strong emotions implies greater transitivity, as Udayana points out.

- (75)

- Ia

- She

- inget

- remember

- teken

- with

- awak-*(ne)

- self-*(POSS.3)

- labuh/telat.

- fall/late

- ‘She remembered that she fell/was late.’ Udayana (2013) (p. 163)

We now move onto awak’s most important property. We have already seen that awakne may always have a long-distance antecedent. However, awak can never be interpreted logophorically, so this precludes it from receiving long-distance antecedents.

- (76)

- Nyomani

- Nyoman

- ngaden

- think

- Ayuj

- Ayu

- nanjung

- AV.kick

- awak*i,j

- self

- ‘Nyomani thinks Ayuj kicked herself*i,j.’

It turns out that awak has different properties from simplex anaphors in closely related languages. I would now like to compare it to the Indonesian simplex anaphor diri, for which an analysis has recently been provided by Kartono et al. (2021), in which diri is a reflexivizer; that is, it is a marker of intransitivity, rather than an argumental reflexive.24 I conclude that such an analysis cannot be straightforwardly be extended to awak.

Like awak, diri only occurs with a limited class of verbs. Reinhart & Siloni (2005) provide a study of reflexivization across languages, arguing that a reflexive interpretation can also be obtained by reducing the object argument, yielding an intransitive verb. Under their analysis, two of the verb’s thematic roles (such as agent-theme) are bundled together and assigned to the subject. This is seen only with grooming verbs in English, such as Mary washed.

It is less restricted in Indonesian. Bare diri is restricted to agent-theme verbs, in line with Reinhart & Siloni’s (2005) generalization.25 Unlike awak, it cannot occur as the object of hate:

- (77)

- a.

- Anton

- Anton

- mem-basuh

- AV.wash

- diri.

- body

- ‘Anton washes himself.’

- b.

- *Anton

- Anton

- mem-benci

- AV.hate

- diri.

- body

- ‘Anton hates himself.’ Indonesian

Furthermore, while awak can appear in agent-benefactive constructions, diri cannot according to I Nyoman Udayana (p.c.); the complex anaphor dirinya is greatly preferred:

- (78)

- a.

- Iai

- She

- meli-ang

- AV.buy-APPL

- awaki

- self

- baju.

- shirt

- ‘(S)he bought him/herself a shirt.’

- b.

- *Dia

- (S)he

- membeli-kan

- AV.buy-APPL

- diri-*(nya)

- self-*(3.GEN)

- baju.

- shirt

- ‘(S)he bought him/herself a shirt.’ Indonesian

Finally, and most importantly, it appears that diri cannot appear after any preposition, unlike awak as previously seen in (74). Overall, awak has a significantly less restricted distribution compared to diri. Extending Kartono et al.’s (2021) analysis of diri as a reflexivizer to awak may not be impossible, though it appears to be difficult. Perhaps Balinese specifies different conditions for thematic role bundling than Indonesian, though this leaves open (74) and (78) above.

4.2 Long-distance reflexives and monomorphemicity

With the properties of awak established, I would like to note that we have just seen data which contradicts a long-standing generalization concerning reflexives first pointed out by Faltz (1985): long-distance anaphors tend to be monomorphemic. Pica (1987) on the other hand claims that they are required to be monomorphemic. A classical example of this, and perhaps the most studied, is the Chinese reflexive ziji.26 Ziji can have long-distance antecedents as the syntactic object of the embedded verb:

- (79)

- Zhangsani

- Zhangsan

- zhidao

- know

- Lisij

- Lisi

- xihuan

- like

- zijii/j.

- self

- ‘Zhangsani knows Lisij likes himselfi/j.’ (Giblin 2016: p. 58)

The dominant position in the literature–first argued for by Pica (1987) and later by Cole et al. (1990)–is that the availability of non-local binding in examples like (79) follows from the monomorphemicity of ziji. The reasoning is simple: the morphologically complex reflexive ta-ziji, made up of the addition of the third person pronoun ta, precludes the possibility of long-distance binding in any context; an illustration is given below:

- (80)

- Zhangsani

- Zhangsan

- zhidao

- know

- Lisij

- Lisi

- xihuan

- like

- ta-ziji*i/j.

- 3-self

- ‘Zhangsani knows Lisij likes himself*i/j.’ (Giblin 2016: p. 58)

One explanation for this is given as follows. Cole et al. (1990) argues that long-distance reflexives are interpreted via head movement, and this can only occur with morphologically simplex anaphors. Complex anaphors are not capable of head movement, so they can only be bound locally.27 But there are obvious problems with Pica’s (1987) strong assertion that long-distance anaphors must be monomorphemic; as discussed in section 2.1 previously, English’s him/herself, which seems to be a complex anaphor, can have non-local antecedents in certain contexts.

To avoid this issue, Haspelmath (2008) provides the most generous interpretation possible of this generalization. The definition is as follows (Haspelmath 2008: p. 19):

- (81)

- Haspelmath’s Universal 7: If a language has different reflexive pronouns in local and long-distance contexts, the local reflexive pronoun is at least as complex phonologically as the long-distance one.

In other words, if the local and long-distance reflexives in a language differ, long-distance pronouns must be simpler (or monomorphemic) and local pronouns must be more complex (bimorphemic or bigger). Here are some examples:

Local and long-distance reflexives, Table 9 from Haspelmath (2008) with Balinese added.

| Local reflexive | Long-distance reflexive | |

| Mandarin | (ta)ziji | ziji |

| Icelandic | sjalfan sig | sig |

| Dutch | zichzelf | zich |

| Telugu | tanu tanu | tanu |

| Bagvalal | e-b-da | e-b |

| Malay | diri-nya | diri-nya |

| English | him-self | him-self |

| Balinese | awak | awak-ne |

As is made apparent in the table above, Balinese contradicts Haspelmath’s Universal 7, exhibiting the exact opposite pattern than is predicted. The simplex anaphor is monomorphemic and can never be long-distance. On the other hand, the complex anaphor is bimorphemic, and yet behaves as an exempt anaphor.28

One way out of this problem might be to argue that awak in Balinese is an reflexivizer, as Kartono et al. (2021) propose for diri in Indonesian. As we have seen, such an approach cannot be straightforwardly extended to awak–which may be an argumental reflexive. Regardless, though, I believe that even if awak is a reflexivizer, this would still disprove Haspelmath’s generalization, for two reasons.

First, Haspelmath (1997) himself has a much broader definition of a pronoun, in that it does not need to be an argument–it is simply a grammatical item which can replace a noun or a noun phrase (p. 10). Furthermore, he greatly extends the definition to include so-called pro-verbs, pro-adjectives and so forth, which are grammatical items that can replace verbs and adjectives respectively. Thus, reflexivizers are still pronouns under Haspelmath’s own definition.

Finally, Déchaine & Wiltschko (2017) provide a formal typology of reflexives under which reflexives come in five different sizes crosslinguistically: DP > ϕP > ClassP > nP > NP. The difference between reflexivizers and, for example, English herself is captured by differences in size: herself is a full DP. For our purposes we need not get into the details of this account, but for them, reflexivizers are nPs, which are still argumental reflexive pronouns that are the object of a verb.29 Adopting this approach would also enable one to maintain the idea that reflexivizers are reflexive pronouns. Thus, I ultimately believe that Balinese anaphors pose a problem for this generalization.

5 Conclusion

I have tried to show that the Balinese Bind construction does not pose a problem to GB and Minimalist theories of syntax. In order to accomplish this, I have presented a wealth of novel data to demonstrate a property of Balinese complex anaphors like awakne that has previously gone unnoticed: they are obligatorily interpreted logophorically in the Balinese Bind construction. This observation allows one to provide an alternate solution of the Balinese Bind, which I have done here, in the framework of Charnavel (2020). Ultimately, it is not relevant whether Spec,TP is an A- or A’-position in Balinese. This proposal also improves on previous GB/Minimalist approaches as well as Wechsler’s HPSG approach, none of which predict awakne’s wider distribution and interpretive properties.

In addition to unraveling the Balinese Bind, I have also attempted to shed light on other issues in the literature on anaphora. Balinese provides a genuine counterexample to a prominent generalization in the literature: if a language has both long-distance and local anaphors available, the local anaphor is at least as complex phonologically as the long-distance one. Balinese is literally the opposite, plainly contradicting this generalization. To conclude, further study into the anaphora of understudied languages might shed light on current theories of reflexives.

Notes

- Previous works, such as Wechsler (1999) and Levin (2014), have not noted that this issue is unique to complex reflexives; Balinese also has simplex reflexives, as discussed in section 4, but these cannot occur in the constructions which Wechsler alleges are problematic to Minimalist approaches. It should also be noted that Balinese has many different anaphors depending on registers. For simplicity, in this paper, I will illustrate only with the reflexives made up of the low register, simplex reflexive awak. [^]

- This assumption reflects the standard within the Minimalist Program and is shared by Levin (2014), whose account for the Balinese Bind is discussed in section 3. Note, however, that nothing hinges on whether Balinese subjects raise to Spec,TP or some other projection. As long as subjects land in the same position in AV, OV, and raising constructions, I am faced with the apparent paradox detailed below. As Wechsler & Arka (1998) point out, there is ample evidence from raising, relativization, extraposition, quantifier float and control that the subject moves to Spec,TP (under a Minimalist account) in OV constructions, just as in AV. [^]

- For further discussion, the reader is referred to Wechsler & Lee (1996), Wechsler & Arka (1998), Udayana (2013) and Levin (2014). [^]

- There have been different analyses of -ne in the literature. For simplicity, I follow Haiduck’s (2014) analysis of -ne as a third person possessive suffix, who argues against decomposing -ne further. An anonymous reviewer notes that the complex anaphor awakne is a simplification of awak ia-ne ‘his/her body,’ done in order to encode possession. The pronoun can be replaced in situ by a question word, ex. bapak nyen-ne ‘whose father’. The correct analysis of ne does not matter for the purposes of this paper, however. [^]

- In particular, under the assumption that binding relations are determined within the argument structure (ARG-S) associated with the lexical description of a predicate, Wechsler argues that licensing of the reflexive in (3) follows from inclusion of the raised NP within the ARG-S of ngenah, where it a-commands the experiencer-PP. I refer the reader to Wechsler’s paper for illustration of the ARG-S assumed for ngenah ‘seem’ along with further details regarding the assumptions of the HPSG approach to binding. [^]

- The data that is presented in this paper was primarily obtained via a mixture of in person and Zoom elicitation sessions from a single native speaker of Balinese. This data was supplemented with additional data via discussion with a Balinese linguist, I Nyoman Udayana. [^]

- Different authors have different ideas of what this local domain is. Under some versions of a Chomskyan analysis, it was the domain containing the anaphor and a subject distinct from that anaphor. I follow Charnavel & Sportiche (2016) in assuming that it is the Spell-Out domain of a phase head, as this formulation is based on the behavior of inanimate anaphora and thus avoids the confound of logophoric licensing. [^]

- Minkoff (2004) also discusses the role of animacy, though he refers to it as consciousness instead, defining a novel Principle E to account for the distribution of such logophoric anaphors. [^]

- I refer the reader to Charnavel & Zlogar (2015) and Charnavel (2020) for further details regarding motivation for the beloved test. [^]

- See Faltz (1985) for the typology of anaphora. [^]

- Note that awakne is the internal argument of a syntactic predicate; this fact runs counter to the predictions of the predicate-based binding theories put forth by Pollard & Sag (1992) and Reinhart & Reuland (1993). [^]

- Charnavel (2020) also predicts partial antecedents to be available for exempt anaphors. In Balinese, the partial reading requires the adverb ajak makejang ‘with all’ in (i), otherwise it is ungrammatical. It is possible that this is due to reasons independent of binding, for instance disambiguation, as awakne ajak makejang is more specified:

[^]

- (i)

- Ayui

- Ayu

- ngorahang

- AV.say

- [awak-ne

- self-POSS.3

- ajak

- with

- makejang]i+

- all

- lakar

- will

- malaib

- run

- ‘Ayui said that theyi+ will run.’

- Awakne is not subject to the blocking effect, unlike with ziji in Chinese (see Giblin (2016)). [^]

- The possibility of subject reflexives is consistent with the absence of verbal agreement in Balinese: under Rizzi’s (1990) anaphor agreement effect, according to which the unacceptability of anaphoric subjects in languages like English follows from the incompatibility of anaphoric elements with syntactic positions construed with agreement, anaphoric subjects are predicted to be possible in languages that lack subject agreement (cf. Woolford (1999)). [^]

- I have seen some variation between my native speaker consultants in their acceptance of the first-person morphology tests. According to Charnavel (2020), the speaker is always a salient attitude holder and, hence, that first-person anaphors like myself can always lack an overt local binder. For I Nyoman Udayana and I Wayan Arka (p.c.), it is very awkward for the first-person anaphor, awak cange, to be mentioned “out of the blue,” as in (i). But (i) and similar examples were fully acceptable for another consultant: