1 Introduction

German has two main types of demonstrative pronouns — the der/die/das-paradigm (DPros) and the diese/dieser/dieses-paradigm (DemPros). However, it is not completely clear what functions differentiate them. Fuchs & Schumacher (2020) proposed that they differ in their referential shift potential; demonstrative pronouns can trigger a shift of the ranking of the entities in discourse, and DPros appear to initiate a shift that has a long-lasting effect on the unfolding discourse, while DemPros often merely trigger a brief change, like a parenthetical, before the previously prominent entity — or another entity (see Schumacher et al. 2022) — is picked up. Patil et al. (2020) showed that language formality is a distinguishing feature such that DPros prefer informal, whereas DemPros prefer formal language. Zifonun et al. (1997), using the contrast between DPros and DemPros in (1a) and (1b), suggested that DPros can refer to the information structurally prominent, i.e. topical, referent (Peter) as well as the less prominent (non-topical) referent (Benz) but DemPros can only refer to the last-mentioned referent, Benz, which makes the DemPro continuation in (1a) implausible (see Patterson et al. 2022 for experimental evidence of the last-mentioned preference for DemPros).

- (1)

- a.

- Peter

- Peter

- will

- wants

- einen

- a

- Benz

- Benz

- kaufen.

- buy

- Der

- he_DPro

- /

- /

- *Dieser

- *he_DemPro

- hat

- has

- wohl

- perhaps

- zu

- too

- viel

- much

- Geld.

- money

- ‘Peter wants to buy a (Mercedes-)Benz. He apparently has too much money.’

- b.

- Peter

- Peter

- will

- wants

- einen

- a

- Benz

- Benz

- kaufen.

- buy

- Der

- he_DPro

- /

- /

- Dieser

- it_DemPro

- soll

- should

- aber

- but

- nicht

- not

- so

- so

- teuer

- expensive

- sein.

- be

- ‘Peter wants to buy a Benz. But it should not be too expensive.’

However, if we consider (2), it is clear that in this case both demonstrative pronouns cannot refer to the topic easily.1 We hypothesize that in (1a), the DPro can refer to Peter because it involves an evaluation of Peter by the (abstract) speaker, thereby making the speaker more prominent than this referent (as proposed by Hinterwimmer & Bosch 2017). Since only the DPro is acceptable in (1a), we extend the proposal in Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017) and hypothesize that only DPros are sensitive to prominence manipulation through evaluative expressions, but not DemPros.

- (2)

- Peter

- Peter

- wollte

- wanted

- einen

- a

- Benz

- Benz

- kaufen.

- buy

- ?Der

- ?he_DPro

- /

- /

- *Dieser

- *he_DemPro

- hatte

- had

- kürzlich

- recently

- eine

- a

- Gehaltserhöhung

- salary increase

- bekommen.

- gotten’

- ‘Peter wanted to buy a Benz. He had recently gotten a salary increase.’

Here we follow Himmelmann & Primus (2015) and von Heusinger & Schumacher (2019) in assuming that prominence is a relational property that singles out one element from a set of elements of equal type and structure and makes this element available for a higher number of operations than its competitors.2 Prominence ranking is assumed to apply at different linguistic levels ranging from the phonological level to the discourse level. On the discourse level, the relevant elements are the discourse referents that have been introduced, and they are assumed to be ranked with respect to various prominence-related scales such as grammatical function, thematic role and order of mention. Crucially, the resolution options of various types of pronouns are assumed to be sensitive to the prominence status of their potential antecedents, with personal pronouns preferring and demonstrative pronouns strongly avoiding maximally prominent discourse referents as antecedents.

Essentially, we propose evaluation as yet another dimension along which the two demonstrative pronouns differ. We report two experiments that test this hypothesis and also carry out exploratory analyses to tease apart the constraints on the two demonstrative pronouns. The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we first briefly summarize the existing proposals that empirically tested the differences between DPros and DemPros, and then discuss the analysis of DPros proposed by Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2016; 2017), on which our own proposal is based. In Section 3, we first outline our proposal (3.1), and then we present the two experiments that we conducted to test the hypotheses derived from that proposal (3.2). In Section 4, the experimental results are discussed with respect to their broader theoretical implications.

2 Previous research on the two types of demonstrative pronouns

2.1 Register and modality

One distinguishing feature of the two types of demonstrative pronouns may be register, with DemPros occurring in more formal contexts than DPros (Wiemer 1996). Patil et al. (2020) followed this line of argumentation and investigated the role of register in a behavioral task. They found that DemPros strongly preferred the formal language register such that contexts involving informal language elicited a sharp decrease in the use of DemPros. For example, in sentences such as (3a) and (3b) where participants had to choose a pronoun from multiple options to fill in the missing word in the sentence, participants chose the DemPro more often in (3a), the formal context, than in (3b), the informal context, where informality was for instance marked by using proper names with determiners and contractions like ‘nen (for the indefinite determiner einen). In contrast, the DPro was almost entirely dispreferred in the formal language environment. Both demonstrative pronouns also preferred the antecedent that was less prominent in terms of grammatical function/thematic role, i.e. the object or patient antecedent was preferred over the subject or agent antecedent.

- (3)

- a.

- Formal

- Die

- the

- Richterin

- judge

- informierte

- informed

- den

- the

- Staatsanwalt,

- public prosecutor

- dass

- that

- {er,

- {he_PPro,

- der,

- he_DPro,

- dieser}

- he_DemPro}

- einen

- another

- weiteren

- Fall

- case

- annehmen

- take on

- müsse.

- must

- ‘The judge informed the public prosecutor that {he_PPro, he_DPro, he_DemPro} must take on another case.’

- b.

- Informal

- Die

- the

- Nadine

- Nadine

- hat

- has

- dem

- the

- Mark

- Mark

- gesagt,

- told

- dass

- that

- {er,

- {he_PPro,

- der,

- he_DPro,

- dieser}

- he_DemPro}

- ‘nen

- a

- Brief

- letter

- bekommen

- got

- hat.

- has

- ‘Nadine told Mark that {he_PPro, he_DPro, he_DemPro} got a letter.’

In a follow-up experiment, using word order variation (canonical vs. non-canonical), Patil et al. (2020) also tested if the DemPro preferred the object antecedent only because it was the last-mentioned antecedent or because it was less prominent being the object. They found that although grammatical function was the main factor influencing the antecedent preference for DemPros, the order of mention of the antecedents had a small effect such that the object antecedent was less strongly preferred when it was mentioned first (see also Fuchs & Schumacher 2020 for an effect of grammatical/thematic role over order of mention).

It has further been suggested that the difference between the two types of demonstrative pronouns may not be due to register but to modality such that DemPros are the preferred choice in the written modality and DPros emerge in the auditory modality (Weinert 2011; Portele & Bader 2016; Voigt 2022). However, register and modality are intertwined, which might account for the mixed findings in rating tasks reported in Patterson et al. (ms.): On the one hand, (unaccented) DPros and DemPros were rated better in spoken modality with an informal register and DPros showed a much stronger effect of modality than DemPros in this case. On the other hand, when the stimuli reflected a formal register, there was no effect of modality for either of the demonstrative pronouns.

2.2 Referential preferences and shift potential

Fuchs & Schumacher (2020) compared the referential preference of DPros and DemPros (along with personal pronouns, PPros) and also the referential shift potential of the pronouns through a story continuation task. The task involved completing stories as in (4) where the context sentence had either an active accusative verb or a dative experiencer verb. In the context sentence of the active accusative condition, the first-mentioned referent was the proto-agent subject and the second-mentioned referent was the proto-patient object. In the dative experiencer condition, the first-mentioned referent was the proto-agent object, the experiencer, and the second-mentioned referent was the proto-patient subject, the stimulus (see Dowty 1991; Primus 1999 for proto-roles). Participants were given only one of the three pronouns in each trial and had to complete the stories by writing down six sentences. The continuations with six sentences made it possible to analyze the referential shift potential of these pronouns by looking at the frequency of mentioning a referent over a longer discourse.

- (4)

- a.

- Active accusative verb

- Jeden

- Every

- Morgen

- morning

- hat

- has

- der

- the

- Pfleger

- nurse.M

- den

- the

- Heimbewohner

- resident.M

- gekämmt.

- combed

- Dabei

- in the process

- hat

- has

- er

- he_PPro

- /

- /

- der

- he_DPro

- /

- /

- dieser

- he_DemPro

- oft

- often

- …

- …

- ‘Every morning the (male) nurse combed the (male) resident. During this process he often …’

- b.

- Dative experiencer verb

- Im

- At the

- Hafen

- harbour

- ist

- is

- dem

- the

- Segler

- sailor.M

- der

- the

- Urlauber

- tourist.M

- aufgefallen.

- noticed

- Wenig

- little

- später

- afterwards

- hat

- has

- er

- he_PPro

- /

- /

- der

- he_DPro

- /

- /

- dieser

- he_DemPro

- dann

- then

- …

- …

- ‘At the harbour, the (male) sailor noticed the (male) tourist. Shortly afterwards he then …’

As far as the choice of referent is concerned, the story completion task revealed that both DPros and DemPros preferred the second-mentioned referent (for DPros 74% and for DemPros 73% of all cases) and PPros preferred the first-mentioned (65% of all cases) irrespective of the verb type, lending support to the claim that thematic role information and/or order of mention represents a more highly ranked cue than grammatical function. There was no statistical difference in the referential preferences for the two demonstrative pronouns. The results from referential shifts in the story continuation were more nuanced. Based on the frequency of mentions of the two referents from the context sentence in the story continuation and the likelihood of using one of the three pronouns to refer to them, Fuchs & Schumacher (2020) concluded that although both demonstrative pronouns showed referential shift potential (in contrast to referential maintenance conveyed by personal pronouns), shifts triggered by DPros had a more long-lasting effect on the discourse structure than DemPros, which initiated only a momentary, parenthetical shift to their referent.

Patterson & Schumacher (2021) reported three acceptability rating studies using two-sentence items as in (5) and they compared the antecedent preferences of DPros and DemPros (along with PPros). This design of items allowed them to compare the antecedent preference of the pronouns, mentioned in the second sentence, with respect to three referents introduced in the preceding (context) sentence. Since the context sentence was a ditransitive construction, the three referents, which were the arguments of the ditransitive verb, had three different thematic roles – agent, recipient and patient. The example item is from Experiment 1a, but the other two (Experiment 1b and 2) had a comparable design where either the gender of the referents was changed or the order of patient and recipient was reversed. Because of the different thematic roles and different linear positions of the three referents in the context sentence, Patterson & Schumacher (2021) could compare the effect of thematic role and order of mention on pronoun resolution in three variations of the target sentence (5a) – (5c). Crucially, the target sentence licensed only a single referent for the pronoun based on gender congruency and verb semantics.

- (5)

- a.

- [Pronoun refers to referent-1 = AGENT]

- Context sentence

- Die

- The

- Eigentümerin

- owner.F

- vermietete

- rented

- dem

- the

- Anwohner

- resident.M

- die

- the

- Parkfläche.

- parking space.F

- ‘The (female) owner rented the parking space to the (male) resident.’

- Target sentence

- Sie

- She_PPro

- /

- /

- Die

- She_DPro

- /

- /

- Diese

- She_DemPro

- war

- was

- froh

- delighted

- über

- over

- den

- the

- langfristigen

- long-term

- Vertrag.

- contract

- ‘She was delighted about the long-term contract.’

- b.

- [Pronoun refers to referent-2 = RECIPIENT]

- Context sentence

- Der

- The

- Eigentümer

- owner.M

- vermietete

- rented

- der

- the

- Anwohnerin

- resident.F

- die

- the

- Parkfläche.

- parking space.F

- ‘The (male) owner rented the parking space to the (female) resident.’

- Target sentence

- Sie

- She_PPro

- /

- /

- Die

- She_DPro

- /

- /

- Diese

- She_DemPro

- war

- was

- froh

- delighted

- über

- over

- den

- the

- langfristigen

- long-term

- Vertrag.

- contract

- ‘She was delighted about the long-term contract.’

- c.

- [Pronoun refers to referent-3 = PATIENT]

- Context sentence

- Die

- The

- Eigentümerin

- owner.F

- vermietete

- rented

- der

- the

- Anwohnerin

- resident.F

- die

- the

- Parkfläche.

- parking space.F

- ‘The (female) owner rented the parking space to the (female) resident.’

- Target sentence

- Sie

- She_PPro

- /

- /

- Die

- She_DPro

- /

- /

- Diese

- She_DemPro

- war

- was

- glücklicherweise

- fortunately

- schattig.

- shady’

- ‘Fortunately it was a shady spot.’

After comparing the acceptability ratings across the three experiments, Patterson & Schumacher (2021) concluded that DPros and DemPros showed a clear effect of order of mention such that both demonstrative pronouns, and not just the DemPros (as proposed in Zifonun et al. 1997), preferred the last-mentioned referent over the 1st and 2nd mentioned ones: however, DPros showed weaker last-mentioned referent preference in one of the three experiments. Interestingly, they also found that both demonstratives showed equally graded sensitivity to the prominence-lending cue of thematic role, such that the referent with the proto-agent role was the least preferred antecedent, the referent with the proto-patient role was the most preferred one and the referent with the proto-recipient role had a preference between the two extremes following canonical argument order. This finding is important for our understanding of prominence scales because it reveals that prominence relations are not binary (as suggested by accounts that propose an anti-agent or anti-topic preference of DPros). Rather the two types of demonstrative pronouns show a nuanced sensitivity to the thematic role scale. Overall, DemPros received higher ratings than DPros as expected under the language formality constraint (Patil et al. 2020).

Thematic role biases have also been investigated in the context of implicit causality verbs. Bader et al. (ms.) carried out two sentence completion studies to find out the interaction between semantic biases through implicit causality and structural constraints — order of mention and grammatical function — for DPros and DemPros. In Experiment 1, they showed partial sentences as in (6) and participants were asked to provide continuations for the text. The continuations provided by the participants revealed which of the two referents (e.g. Peter or the fisherman) were chosen as the antecedent of the pronoun. The two conditions (6a) and (6b) varied in terms of the kind of implicit causality verbs they used. In condition (6a), the verb required a subject-experiencer argument and in (6b), the verb required an object-experiencer argument. Since in implicit causality verbs, the stimulus argument (e.g. the object fisherman in (6a) and the subject fisherman in (6b)) has a strong next-mention bias in the subordinate clause starting with weil (because), the pronouns are expected to refer to the antecedent functioning as the stimulus. On the other hand, the structural constraints on the demonstrative pronouns are also expected to have an influence. Essentially, the antecedent preferences should reveal how the interaction between semantic biases through implicit causality and structural constraints pans out. Experiment 2 was similar to Experiment 1 with only a minor difference in the continuation prompt.

- (6)

- a.

- Subject experiencer verb

- Peter

- Peter

- achtet

- respects

- den

- the

- Fischer,

- fisherman

- weil

- because

- der / dieser…

- he_DPro / he_DemPro…

- ‘Peter respects the fisherman because he_DPro / he_DemPro…’

- b.

- Object experiencer verb

- Der

- The

- Fischer

- fisherman

- beeindruckt

- impresses

- Peter,

- Peter

- weil

- because

- der / dieser…

- he_DPro / he_DemPro…

- ‘The fisherman impresses Peter because he_DPro / he_DemPro…’

The results of the two experiments showed a strong effect of the semantic bias (i.e. implicit causality) such that for both verb types and both demonstrative pronouns, the referent functioning as the stimulus argument of the verb was strikingly the preferred antecedent. Since the stimulus argument had a strong next-mention bias under the implicit causality manipulation, Bader et al. (ms.) concluded that the semantic bias outweighed the structural biases. They further observed that there was still an influence of the structural bias such that the demonstrative pronouns showed preference towards the object antecedent (similar findings were observed by Patterson et al. 2022 for DemPros, where the stimulus bias of implicit causality verbs lowered object preferences of the demonstrative), and interestingly there was no difference between the DPros and DemPros in terms of the influence of either the semantic bias or the structural constraints. Bader et al. (ms.) concluded that the two demonstratives do not differ along structural and semantic biases.

2.3 Interim Summary

Overall, the existing experimental work comparing DPros and DemPros provides clear evidence that suggests: (i) the two pronouns do not differ in their referential preference — both avoid the most prominent referent, (ii) both show referential shift potential, but (iii) they differ along the scale of language register and modality — DemPros prefer formal language and DPros prefer informal language and the spoken modality. There is also some evidence suggesting that DemPros have a stronger last-mentioned preference than DPros, whereas DPros have a more sustained referential shift potential than DemPros.

Before presenting our own analysis in Section 3.1, we will summarize the analysis of DPros proposed by Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2016; 2017) in the next section, since its basic assumptions are crucial for our account of the contrast between DPros and DemPros.

2.4 DPros and perspectival prominence

Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2016; 2017) observe that DPros do not always disprefer maximally prominent referents as antecedents or binders (see also Hinterwimmer et al. 2020 for further empirical evidence; for the purposes of this paper, we will focus on coreference exclusively and disregard binding configurations). Note, however, that the notion of prominence on which this conclusion is based is not clearly defined; on the approach we propose in Section 3.1, the discourse referents that are maximally prominent for Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2016; 2017) are no longer maximally prominent.

Consider the contrast between (7a) and (7b), on the one hand, and (8a) and (8b), on the other. In all cases, the respective opening sentence introduces a referent that is maximally prominent in terms of order of mention, grammatical function and thematic role: In (7), the proper name Peter occurs in clause-initial position, it is the subject of the matrix clause and its referent is the experiencer of the main clause event as well as the agent of the event introduced by the temporal adjunct clause, where Peter is picked up by a personal pronoun functioning as the subject. Likewise, in the opening sentence of (8) the proper name Paul occurs in clause-initial position, it is the subject of the clause and its referent is the experiencer of the state introduced by the verb wollte (wanted). Nevertheless, the respective maximally prominent referent can be picked up by a DPro more easily in one variant of the continuation than in the other. According to Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2016; 2017), the relevant factor distinguishing the continuations in (7b) and (8b), where the DPro can pick up the maximally prominent referent more easily, from the continuations in (7a) and (8a), where this is not the case, is perspective: Both (7a) and (8a) are most likely interpreted as expressing the perspective of the maximally prominent referent, while the continuations in (7b) and (8b) can only be understood as expressing the speaker’s or narrator’s perspective.

- (7)

- Peteri

- Peteri

- seufzte,

- sighed

- als

- when

- er

- he

- die

- the

- Tür

- door

- öffnete

- opened

- und

- and

- sah,

- saw

- dass

- that

- die

- the

- Wohnung

- flat

- mal wieder

- again

- in

- in

- einem

- a

- fürchterlichen

- terrible

- Zustand

- state

- war.

- was

- ‘Peter sighed when he opened the door and saw that the flat was in a terrible state again.’

- a.

- Verdammt,

- Damn

- *deri

- *he_DProi

- /

- /

- eri

- he_PProi

- hatte

- had

- doch

- after all

- gestern

- yesterday

- erst

- only

- aufgeräumt.

- tidied up

- ‘Damn, he had only tidied up yesterday, after all.’

- b.

- Deri

- He_DProi

- /

- /

- Eri

- He_PProi

- kann

- can

- sich

- REFL

- einfach

- simply

- nicht

- not

- gegen

- against

- seinen

- his

- Mitbewohner

- flatmate

- durchsetzen.

- stand ground

- ‘He is simply unable to stand his ground against his flatmate.’

- (Adapted from Hinterwimmer & Bosch 2016.)

- (8)

- Pauli

- Pauli

- wollte

- wanted

- mit

- with

- Peterj

- Peterj

- laufen

- run

- gehen.

- go.

- ‘Paul wanted to go running with Peter.’

- a.

- Aber

- But

- der*i,j

- he_DPro*i,j

- /

- /

- eri,j

- he_PProi,j

- war

- was

- leider

- unfortunately

- erkältet.

- caught cold

- ‘But he had a cold unfortunately.’

- b.

- Eri,j

- He_DProi,j

- /

- /

- Deri,j

- He_PProi,j

- sucht

- look for

- sich

- REFL

- immer

- always

- Leute

- people

- als

- as

- Trainingspartner

- training partners

- aus,

- die

- who

- nicht

- not

- richtig

- really

- fit

- fit

- sind.

- are

- ‘He always picks people as training partners who are not really fit.’

- (Adapted from Hinterwimmer & Bosch 2016.)

The sentence in (7a) is an instance of Free Indirect Discourse (FID), i.e. it is interpreted as a thought that Peter has when he notices the state his flat is in. As is characteristic of FID, all perspective-dependent linguistic expressions with the exception of pronouns and tenses are interpreted with respect to the perspective of the protagonist whose thought is rendered, while pronouns and tenses are interpreted with respect to the narrator’s perspective. In the case of (7a), verdammt (damn) is most likely understood as expressing Peter’s negative feelings, not the narrator’s, and the deictic temporal adverb gestern (yesterday) is interpreted with respect to Peter’s (fictional) context, i.e. it refers to the day preceding the day on which the events introduced by the opening sentence took place.

Likewise, the modal particles doch and erst (which roughly translate as after all and only in this context) are intuitively understood as expressing Peter’s attitudes, i.e. his surprise that the flat is in a terrible state again in spite of his recent efforts of cleaning up. The second sentence in (8a) is likewise most naturally interpreted as expressing the maximally prominent protagonist’s perspective. On the most plausible interpretation, Peter has a cold and therefore cannot go running. Note that this does not mean that the sentence is an instance of FID rendering a conscious thought of Paul. It simply means that the sentence expresses Paul’s general attitude towards the described situation.

The continuations in (7b) and (8b), in contrast, can only be understood as evaluative comments of the speaker or narrator on the character and dispositions of Peter and Paul, respectively. This is not only due to the content, but also due to the shift from past tense to present tense, which breaks the narrative continuity. Essentially, DPros can pick up referents that are maximally prominent in terms of order of mention, grammatical function and thematic role if the sentence containing the DPro clearly expresses the perspective of a referent that is different from the antecedent. Note, however, that for some speakers the shift from past tense, which suggests standard narration, to present tense, which can only be made sense of if the reader is willing to accommodate a rather unusual, highly ‘involved’ narrator, makes the entire text segment rather awkward. In order to avoid this complication, we have only used text segments in which no such temporal shifts occur in the experiment reported in Section 3.2 below. Based on this observation, Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2016; 2017) draw the conclusion that DPros are anti-logophoric pronouns, i.e. they avoid referents functioning as perspectival centers as their antecedents. They define the term perspectival center (cf. Harris 2012; Harris & Potts 2009) as in (9):

- (9)

- A referent α is the perspectival center with respect to a proposition p iff p is the content of a thought or perception of α.

Recall the observation that in neutrally narrated sentences, DPros have a strong tendency to avoid referents that are maximally prominent in terms of order of mention, grammatical function and thematic role. For such cases, Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017) suggest that these referents usually function as topics. This is based on the assumption that at least in the absence of overriding contextual factors, the topic of a sentence tends to be the referent that is maximally prominent in terms of order of mention, grammatical function and thematic role. Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017) adopt the notion of aboutness topicality from Reinhart (1981), according to which the topic of a sentence is the referent for which a mental address is created such that the proposition denoted by that sentence is stored under the address. Crucially, they assume that topics are taken as perspectival centers by default in the absence of a perspectivally prominent narrator or protagonist. Consequently, the proposition denoted by the respective sentence is interpreted as the content of a thought or perception of the referent functioning as its aboutness topic by default.

3 A unified prominence-based account of the two types of demonstrative pronouns

3.1 The proposal

The account proposed by Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017) can be applied to explain the acceptability of the DPro in (1a), repeated here as (10a), and its unacceptability in (2), repeated here as (10c). In (10a), the sentence containing the DPro is an evaluative statement about the DPro’s referent, Peter. Consequently, the abstract speaker/narrator is the perspectival center in (10a) and accordingly the DPro is free to pick up the topical referent, Peter. In (10c), in contrast, the sentence containing the DPro is a factual statement describing the next event in the sequence that took place. Consequently, the abstract speaker’s/narrator’s perspective is not prominent, and the topical referent is taken to be the perspectival center by default. Accordingly, the topical referent cannot be picked up by the DPro without violating anti-logophoricity. Finally, in (10b), there is no violation of anti-logophoricity since the DPro does not pick up the topical referent anyway.

- (10)

- a.

- Peter

- Peter

- will

- wants

- einen

- a

- Benz

- Benz

- kaufen.

- buy

- Der

- he_DPro

- /

- /

- *Dieser

- *he_DemPro

- hat

- has

- wohl

- perhaps

- zu viel

- too much

- Geld.

- money

- ‘Peter wants to buy a (Mercedes-)Benz. He apparently has too much money.’

- b.

- Peter

- Peter

- will

- wants

- einen

- a

- Benz

- Benz

- kaufen.

- buy

- Der

- he_DPro

- /

- /

- Dieser

- it_DemPro

- soll

- should

- aber

- but

- nicht

- not

- so

- so

- teuer

- expensive

- sein.

- be

- ‘Peter wants to buy a Benz. But it should not be too expensive.’

- c.

- Peter

- Peter

- wollte

- wanted

- einen

- a

- Benz

- Benz

- kaufen.

- buy

- *Der

- *he_DPro

- /

- /

- *Dieser

- *he_DemPro

- hatte

- had

- kürzlich

- recently

- eine

- a

- Gehaltserhöhung

- salary increase

- bekommen.

- gotten’

- ‘Peter wanted to buy a Benz. He had recently gotten a salary increase.’

An analysis of the pattern exemplified by (10a)–(10c) that simply adopts assumptions from Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017) about DPros is unsatisfactory insofar as it has to treat DemPros in an entirely different manner: While the behavior of DPros is accounted for via their avoidance of referents functioning as perspectival centers, the behavior of DemPros is accounted for via their avoidance of referents that are maximally prominent in terms of order of mention, grammatical function and thematic role. We, therefore, propose a unified analysis of DPros and DemPros that builds on an assumption already sketched as an alternative account of DPros in Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017) (see also Hinterwimmer et al. 2020 for discussion). In this analysis, both DPros and DemPros avoid maximally prominent referents as antecedents. They differ with regard to the scales determining the maximally prominent referent, however. On the scale that is relevant for DPros, perspectival centers are more prominent than aboutness topics, which are in turn more prominent than the other referents. The scale that is relevant for DemPros, by contrast, does not include perspectival centers. Consequently, aboutness topics are the maximally prominent referents.

Following Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017), we assume that referents that are maximally prominent in terms of order of mention, grammatical function and thematic role, function as aboutness topics for both types of pronouns (at least in the absence of overriding factors at the level of global discourse structure). We do not have a conclusive answer to the question of why the prominence scales differ for the two pronouns. However, we do not find this difference very surprising considering the fact that there are many languages that have logophoric pronouns, which are sensitive to perspective taking (see e.g. Sells 1987 for an overview), in addition to pronouns that are not sensitive to perspective taking at all. Hence, perspective taking can be directly relevant for the resolution options of one type of pronoun, and completely irrelevant for another.

Another possible analysis would be in terms of the form-specific multiple constraints approach proposed by Kaiser & Trueswell (2008) for two types of Finnish pronouns. To adopt this proposal, we would have to say that the resolution options of DemPros and DPros are determined with respect to two different sets of constraints, one of which weighs avoidance of the perspectival center higher than avoidance of the aboutness topic whenever the perspectival center is instantiated as a discourse topic, while the other one does not include avoidance of the perspectival center as a constraint. Empirically, this approach would make the same predictions as ours. However, conceptually, we find our approach simpler since it allows us to state clearly what the two types of pronouns have in common — a strong tendency to avoid the most prominent discourse referent.

In order for our analysis to receive empirical support, we have to assume pace Hinterwimmer & Bosch (2017) that aboutness topics are not perspectival centers by default in neutrally narrated sentences. Rather, such sentences simply do not contain perspectival centers at all. For concreteness, we assume, following Altshuler & Maier (2020; 2022), that while all texts are interpreted as being told by an implicit narrator, only narrators whose perspective is made prominent in a text are represented as discourse referents, like speakers in oral conversation. Perspectivally prominent abstract speakers/narrators like those in (10a) (and (7b) and (8b)) are therefore represented as discourse referents that become the highest ranked elements on the scales relevant for the resolution options of DPros. In the absence of such a discourse referent, the second highest ranked element on the scale, the respective aboutness topic, becomes the highest ranked one. For DemPros, in contrast, the discourse referent functioning as the aboutness topic is the highest ranked element, irrespective of whether the semantic representation of the sentence with the DemPro contains a discourse referent for the abstract speaker/narrator or not.

The analysis just proposed makes a clear prediction: Whenever a sentence expresses an evaluation of the referent functioning as aboutness topic, a DPro, but not a DemPro should be able to pick up that referent. In the absence of such an evaluation, both DPros and DemPros should be unable to pick up a topical referent. In Section 3.2, we present two experiments testing this prediction and in Section 4 we turn to the question of what our analysis has to say about the contrast between DPros and DemPros with respect to language formality, modality and referential shift potential.

3.2 The experiments

In this section, we describe two experiments that empirically test the claims of the unified prominence-based account of the two types of demonstrative pronouns. In Experiment 1a, we directly tested the predictions of the hypothesis, and in Experiment 1b, we carried out an exploratory analysis to test if the degree of evaluation — weak to strong — has any influence on the acceptability of either of the demonstrative pronouns.

3.2.1 Experiment 1a

In order to test the hypotheses regarding the two demonstrative pronouns’ sensitivity to the factor of evaluation, we designed an acceptability rating study. Furthermore, native speakers’ intuitions suggest that negative evaluation of a referent (as in (10a)) renders the use of a DPro more acceptable than a positive evaluation. Thus, we also assess this intuition through a between-items design.

Methods

Design and materials

We designed 32 experimental sets with a 2×2 design. The two factors were the type of the pronoun (DPro vs. DemPro) and the presence of evaluation (neutral vs. evaluative sentences). The first sentence was the same across all four conditions. Regarding the second sentence that involved the critical manipulation, we also controlled for the polarity of evaluation (positive vs. negative) between items: half of the items had negative evaluations as in (11) and the other half had positive evaluations as in (12). We included two types of fillers — 16 good fillers and 16 bad fillers. These fillers also functioned as instructional manipulation checks and helped us decide which participants did not give reliable ratings. The final set of items also included 48 items from an unrelated experiment that were compatible in terms of the design.

- (11)

- Sentence 1 (same across all conditions)

- Maria

- Maria

- hat

- has

- Peter

- Peter

- geohrfeigt.

- slapped

- ‘Maria slapped Peter.’

- Sentence 2

- Evaluative:

- Die

- She_DPro

- /

- /

- Diese

- She_DemPro

- hat

- has

- sich

- REFL

- einfach

- simply

- nicht

- not

- im

- in

- Griff!

- control

- ‘She just can’t control herself!’

- Neutral:

- Die

- She_DPro

- /

- /

- Diese

- She_DemPro

- wollte

- wanted

- die

- the

- Rechnung

- bill

- nicht

- not

- alleine

- alone

- bezahlen.

- pay

- ‘She didn’t want to pay the bill alone.’

- (12)

- Sentence 1

- Volker

- Volker

- hat

- has

- Anja

- Anja

- einen

- a

- Donut

- donut

- vom

- from the

- Bäcker

- baker

- mitgebracht.

- brought

- ‘Volker brought Anja a donut from the baker.’

- Sentence 2

- Evaluative:

- Der

- He_DPro

- /

- /

- Dieser

- He_DemPro

- ist

- is

- wirklich

- really

- ein

- a

- fürsorglicher

- caring

- Mensch!

- person

- ‘He really is a caring person!’

- Neutral:

- Der

- He_DPro

- /

- /

- Dieser

- He_DemPro

- wollte

- wanted

- jede

- every

- Woche

- week

- etwas

- something

- Neues

- new

- beim

- at the

- Bäcker

- bakery

- aussuchen.

- choose

- ‘He wanted to choose something new at the bakery every week.’

Participants

We gathered data from 129 undergraduate students at the University of Cologne who received course credit for participation.

Procedure

The experiment was programmed using PCIbex, a platform for programming and hosting online experiments (Zehr & Schwarz 2018) and participation took place online. Participants were shown trials as in (11) and (12). They were asked to judge how the second sentence sounded as a continuation of the first and rate it on a 1–7 Likert scale (1 = completely unacceptable, 7 = completely acceptable). The items were divided into eight unique lists since the other experiment included in this assessment consisted of eight conditions. Participants were randomly assigned to the lists and the selected list was randomized for every participant. Since, in total, each participant had to rate 112 trials, we gave a three minutes’ mandatory break in the middle of the experiment to reduce the influence of respondent fatigue.

Data analysis

All data processing and analyses reported in the paper were carried out in R (R Core Team 2022) in the Bayesian framework. Carrying out data analysis in the Bayesian framework has many advantages over the frequentist framework. The two main advantages for us were quantifying the uncertainty about the effects through 95% posterior credible intervals (95% CrI) and the ease of fitting complex models. The 95% CrI specifies the range of values over which one can be 95% certain that the true value of a parameter (representing an effect) lies, given the data and the model. This range is considered “credible” enough for making theoretical inferences about the presence of an effect in light of the data. Moreover, complex models such as a model with maximal random effects structure (Barr et al. 2013) almost always converge in the Bayesian framework which is not the case with frequentist models that are fit using tools such as lme4.

Since the responses were on the ordinal scale (ordered values from 1 to 7) we used the mixed-effects ordinal regression with probit link function in the Bayesian framework (Bürkner & Vuorre 2019; Veríssimo 2021). brms provides an interface to Stan, a probabilistic programming language for specifying Bayesian statistical models (Carpenter et al. 2017). We used the default prior provided by brms. The models were fit with a maximal random effects structure (unless mentioned otherwise in the results). We made inferences based on the 95% CrI. Each model included four sampling chains that ran for 5000 iterations with a warm-up period of 2000 iterations. For each effect, we report its mean parameter estimate and the 95% posterior CrI for the parameter. We use CrI to make inferences about the presence of an effect: if the 95% CrI for an effect does not include zero, we consider that there is compelling evidence for that effect and if only a small part of the 95% CrI includes zero and the effect is theoretically important we assume that there is weak evidence for that effect. For making such a graded inference about an effect, we also report the posterior probability of the parameters being greater than zero or less than zero, depending on the sign of the estimated parameter. The posterior probability is calculated by using the posterior sample for a parameter estimated by the statistical model (given the data and the priors) and it denotes the proportion of the sample that is less than or greater than zero.

Apart from testing the hypothesis about the effect of evaluation on demonstrative pronouns, we also tested the effect of the polarity of evaluation (positive vs. negative evaluation). This analysis was carried out because informal native speakers’ judgments suggested that there could be an effect of these two manifestations. The items were designed such that half had positive and the other half had negative evaluations.

In the final analysis, we excluded data from non-native speakers and participants who gave low attention responses. The attention checks were carried out through appropriately designed filler items. This procedure led to an exclusion of 15 out of 129 original participants. We also excluded data from three experimental items which were later found to have typos.

Predictions

Based on our hypotheses, we predicted the following effects: (i) the DPro-evaluative condition is more acceptable than the other three conditions and (almost) completely acceptable, (ii) the DPro-neutral condition is as acceptable as the DemPro-neutral, and (iii) there is no effect of evaluation between the two DemPro conditions. For making inferences about how acceptable an independent condition is (e.g. is the DPro-evaluative condition almost completely acceptable?) we considered our prior knowledge with acceptability ratings as the yardstick for comparison. We have observed that an unmarked pronoun in German, the personal pronoun (PPro), receives a mean rating of 6 or above (on a 1–7 Likert scale) and DPros in an unlicensed context (e.g. a context where a personal pronoun can instead be used) receive a mean rating of 4 or below. With this yardstick, we considered a mean rating of 6 or above as almost acceptable and a mean rating in the range of 4.5 to 6 (excluding 6) as not completely acceptable but relatively good (cf. footnote 3 in the Discussion section for an experiment with a direct comparison of ratings for DPro and DemPro conditions with PPro conditions).

Results

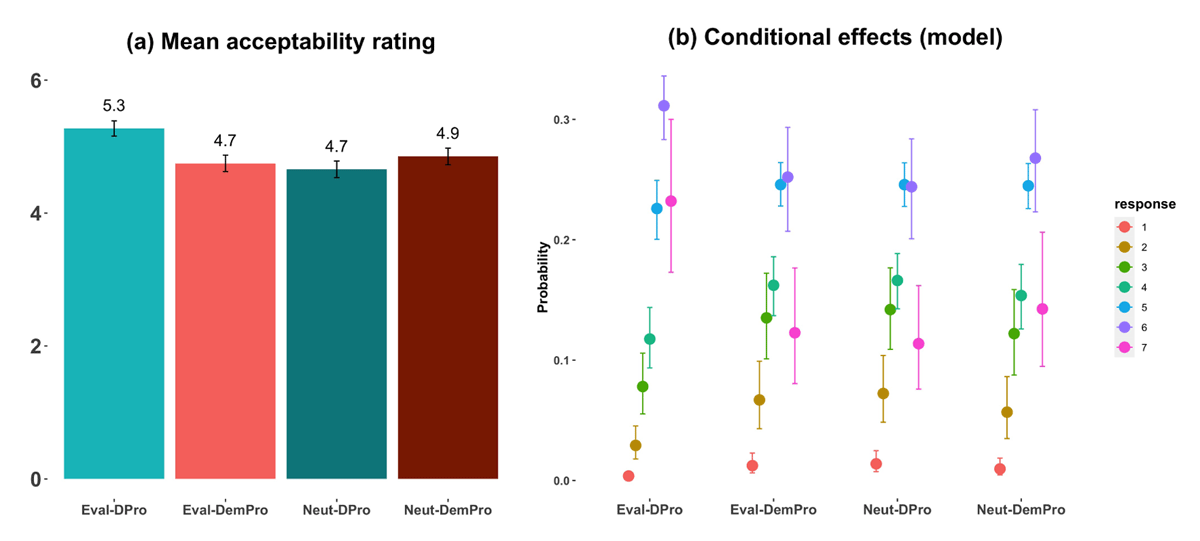

The results are summarized in Figure 1(a) in terms of the mean rating for the four conditions. In the first model, we tested the effect of all independent variables considered in the design of the experiment — pronoun type (sum coded with –1 for DemPro and +1 for DPro), evaluation (sum coded with –1 for neutral and +1 for evaluative), polarity of evaluation (treatment contrast with negative polarity as the reference level) and the interaction between pronoun type and evaluation. We also included a random by-subject slope for interaction terms and the polarity of evaluation, and random by-item slope for interaction terms but no random by-subject slope for the polarity of evaluation since it was a between-item factor (for the detailed structure of the model see the specification for Model (1) in the Appendix). The model estimates for fixed effects, 95% CrI and posterior probability are listed in Table 1. Overall DPros were reliably rated higher than DemPros, and there was weak evidence for evaluative conditions being rated higher than neutral conditions, but there was no indication of any effect of the polarity of evaluation. There was a reliable interaction between pronoun type and evaluation.

(a) Mean acceptability rating and 95% confidence interval for four conditions. For visualization purposes, means and confidence intervals are calculated by treating the response variable (the acceptability rating) as a metric variable instead of an ordinal variable; the data analysis is carried out by treating the response variable as an ordinal variable. (b) Conditional effects across four conditions to aid the interpretation of the model. Conditional effects are the model’s predicted proportion of responses (posterior means and 95% CrI) across response options (1–7) for each condition. The effects are extracted from the estimates of a model that pairwise compared the ‘Eval-DPro’ condition with the other three conditions (Model (2) in the Appendix). For the ‘Eval-DPro’ condition the model clearly predicts a higher proportion of 6 and 7, and a lower proportion of 1, 2, and 3 responses compared to the other three conditions. In contrast, there is no clear difference between the other three conditions.

Results of the statistical analysis (Model (1) in the Appendix) of the data from Experiment 1a to test the effects of pronoun type (DPro vs. DemPro), evaluation (evaluation vs. neutral), polarity of evaluation (positive vs. negative) and the interaction of pronoun type and evaluation — estimates of the model for various effects, corresponding 95% credible intervals (95% CrI) and the posterior probabilities (Post. Prob.). Effects for which the credible interval excludes zero are shown in bold.

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CrI | Post. prob. |

| Pronoun type | 0.07 | [0.01, 0.14] | 0.99 |

| Evaluation | 0.10 | [0, 0.19] | 0.98 |

| Polarity of evaluation | 0.06 | [–0.08, 0.19] | 0.80 |

| Pronoun type : Evaluation | 0.14 | [0.08, 0.21] | 1.00 |

To test if DPros in the evaluative condition were more acceptable than the other three conditions (prediction (i)) we fitted another model where we carried out a pairwise comparison between Eval-DPro and the other three conditions (Model (2) in the Appendix). The model had pronoun type as the predictor (treatment contrast with Eval-DPro as the reference level) and maximal random effect structure. The model revealed that the Eval-DPro condition was more acceptable than the other three conditions (see Figure 1(b) and Table 2).

Results of the statistical analysis (Model (2) in the Appendix) of the data from Experiment 1a to compare the DPro-evaluative condition to the other three conditions — estimates of the model for various effects, corresponding 95% credible intervals (95% CrI) and the posterior probabilities (Post. Prob.). Effects for which the credible interval excludes zero are shown in bold.

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CrI | Post. prob. |

| Eval-DemPro | –0.43 | [–0.63, –0.24] | 1.00 |

| Neutral-DPro | –0.48 | [–0.69, –0.27] | 1.00 |

| Neutral-DemPro | –0.34 | [–0.57, –0.10] | 1.00 |

To test the prediction that both pronouns should be rated equally in the neutral condition (prediction (ii)) we carried out a pairwise comparison between the Neut-DemPro and Neut-DPro conditions (treatment contrast with Neut-DemPro as the reference level; Model (3) in the Appendix). However, the model revealed weak evidence for the Neut-DPro condition being rated lower than the Neut-DemPro condition (see Table 3). To test the prediction that DemPros are not influenced by evaluation (prediction (iii)) we carried out a pairwise comparison between the Eval-DemPro and Neut-DemPro conditions (treatment contrast with Neut-DemPro as the reference level; Model (4) in the Appendix). The model showed no support for any reliable difference between the two conditions (see Table 4).

Results of the statistical analysis (Model (3) in the Appendix) of the data from Experiment 1a to compare the two neutral conditions — the estimate of the model for the effect, the corresponding 95% credible interval (95% CrI) and the posterior probability (Post. Prob.).

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CrI | Post. prob. |

| Neutral-DPro | –0.13 | [–0.27, 0] | 0.97 |

Results of the statistical analysis (Model (4) in the Appendix) of the data from Experiment 1a to compare the two DemPro conditions — the estimate of the model for the effect, the corresponding 95% credible interval (95% CrI) and the posterior probability (Post. Prob.).

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CrI | Post. prob. |

| Eval-DemPro | –0.10 | [–0.30, 0.10] | 0.84 |

3.2.2 Discussion

The results of Experiment 1a revealed that: (i) the DPro-evaluative condition is more acceptable than the other three conditions — DPro-neutral, DemPro-evaluative and DemPro-neutral — however, it was not completely acceptable, (ii) the DPro-neutral and DemPro-neutral conditions receive comparable ratings, however, the DPro-neutral condition is somewhat less acceptable than the DemPro-neutral, and (iii) there is no effect of evaluation between the two DemPro conditions. The results are largely consistent with the predictions of our hypothesis that only DPros are sensitive to the manipulation of prominence through an evaluative expression, but DemPros are immune to any such manipulation.

Although the analysis confirmed our predictions, some of the patterns in the data were surprising. We expected the DPro-evaluative condition to be perfectly acceptable, which was not the case. Patterson et al. (ms.) observed that DPros are less acceptable in the written modality than in the spoken modality (this effect could have been boosted by register). Since our experiment was presented in written modality, it is possible that the lower than perfect ratings reflect the influence of modality. Effects of prosody that are overtly realized in spoken, but not written presentations, can provide additional cues for coreference relations with the immediately preceding sentence. The influence of modality could also explain why the DPro-neutral condition was rated slightly worse than the DemPro-neutral condition.

Moreover, the two neutral conditions overall received relatively high ratings. It has been observed that the two pronouns differ along the scale of language register and modality such that DemPros prefer formal language and DPros prefer informal language in combination with the spoken modality. We speculated that this could be due to the lack of any items in the set of trials with personal pronouns which are acceptable across the board. Since we did not have any predictions for PPros with respect to the manipulation of evaluation we did not include them in the design. However, we carried out a follow-up study that included PPros to test our speculation. The results merely confirmed the patterns from Experiment 1a.3

3.2.3 Experiment 1b

Since evaluation had an effect on the acceptability of DPros, it is quite possible that the acceptability of DPros varies with the degree of evaluation (mild vs. strong evaluation) such that stronger evaluations yield better acceptability. We did not have a specific hypothesis about the effect of degree of evaluation and this was a completely exploratory study since the items in Experiment 1a were also not designed to vary for degree of evaluation, but, we found it to be an informative follow-up study.4 The follow-up study basically involved testing if the acceptability ratings observed for the evaluative conditions in Experiment 1a were influenced by the variations in the degree of evaluation across the items.

Methods

Design and materials

For testing the effect of the degree of evaluation, the goal was to establish how positive or negative the evaluation was in each item. We used the items in the evaluative conditions from Experiment 1a and collected ratings on a weak to strong scale. Items in neutral conditions formed the filler items. This led to 32 items in two conditions and 32 fillers in two conditions. Effectively we had 64 trials in each of the two lists.

Participants

We gathered data from thirty-two self-reported native speakers of German recruited through Prolific (14 females and 1 unreported gender, mean age = 32.9 years, age range = 21–53). Each participant was paid £1.25.

Procedure

As in the previous experiment, Experiment 1b was programmed using PCIbex, a platform for programming and hosting online experiments (Zehr & Schwarz 2018). We collected ratings from native speakers for the degree of evaluation on a scale from –10 (extremely negative) to +10 (extremely positive).

Data analysis

For analyzing the effect of the degree of evaluation on acceptability of the two evaluative conditions, we rescaled the ratings from the original ratings in the range –10 to +10 to the range 0 to 10 such that the rating of –1, –2, … –10 was mapped to 1, 2, … 10, respectively. This ensured that the rating for the degree only encoded the strength of evaluation and not the polarity of it, and higher numerical values for a rating represented a stronger evaluation independent of the polarity of evaluation. We took means of ratings for each item across ratings and used that as the independent variable in the data analysis.

As in the previous experiment, the data analysis was carried out in the Bayesian framework using the mixed-effects ordinal regression following Bürkner & Vuorre (2019). The model was fitted with a maximal random effects structure such that there was, by-subject random intercept and by-condition (DPro vs. DemPro) random slope. There was no random effect parameter for items since the evaluation rating was averaged by-item. We made inferences based on the 95% CrI. Each model included four sampling chains that ran for 5000 iterations with a warm-up period of 2000 iterations. We report results in the same manner as in Experiment 1a.

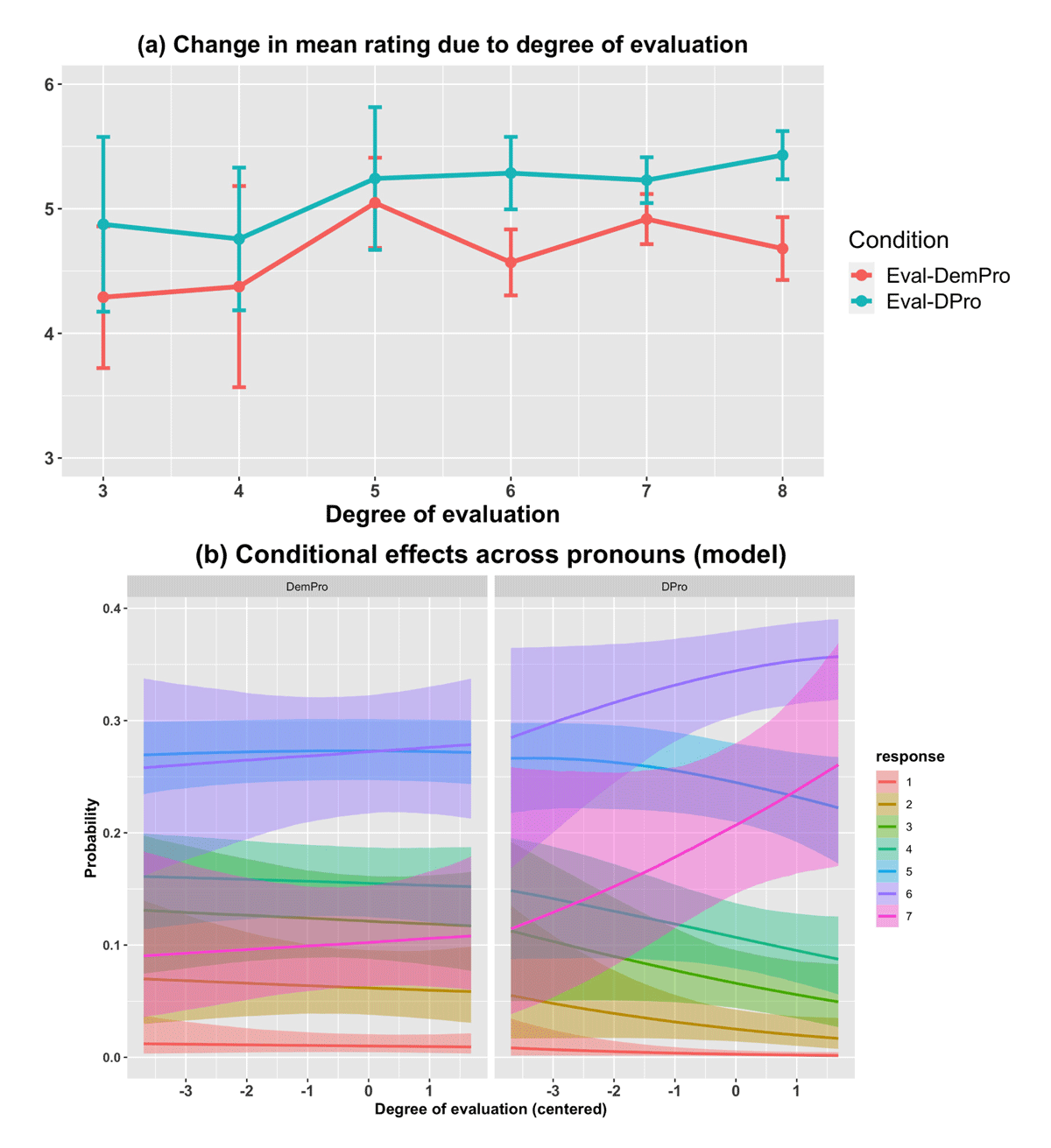

Results

The results are summarized in Figure 2 and Tables 5, 6, 7. In the first model, we tested the effect of pronoun type (sum coded with –1 for DemPro and +1 for DPro), degree of evaluation (centered) and the interaction between the two. We also included a random by-subject slope for interaction terms, and a random by-item slope for the pronoun type but no random by-subject slope for degree of evaluation since it was a between-item factor (see Model (5) in the Appendix and Table 5 for model estimates). The model revealed a reliable effect of the pronoun type and some evidence for degree of evaluation, however, there was no evidence for an interaction between the two factors.

(a) Change in mean acceptability rating as a function of the degree of evaluation across two evaluative conditions. The x-axis numerically represents the degree of evaluation; the larger the number, the stronger the evaluation. For visualization purposes, means and confidence intervals are calculated by treating the response variable (the acceptability rating) as a metric variable instead of an ordinal variable; the data analysis is carried out by treating the response variable as an ordinal variable. (b) Conditional effects of the degree of evaluation for DemPro and DPro, plotted for the purpose of interpretation of the model. Conditional effects are the model’s predicted proportion of responses (posterior means as lines and 95% CrI as shaded bands) across response options (1–7). The effects are extracted from the estimates of a model that tested the interaction between degree of evaluation and pronoun type (Model (5) in the Appendix). For DPros the model predicts an increase in the proportion of 6 and 7 responses as the degree of evaluation increases, and a decrease in the proportion of 1–5 responses as the degree of evaluation increases. In contrast, for DemPros there is no clear increase or decrease in the proportion of any response as a function of the degree of evaluation.

Results of the statistical analysis (Model (5) in the Appendix) of the data from Experiment 1b to test the effects of pronoun type (DPro vs. DemPro), degree of evaluation and their interaction — estimates of the model for various effects, corresponding 95% credible intervals (95% CrI) and the posterior probabilities (Post. Prob.). Effects for which the credible interval excludes zero are shown in bold.

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CrI | Post. prob. |

| Pronoun type | 0.23 | [0.11, 0.34] | 1.00 |

| Degree of eval | 0.06 | [–0.03, 0.15] | 0.92 |

| Pronoun type : Degree of eval | 0.04 | [–0.04, 0.12] | 0.86 |

Results of the statistical analysis (Model (6) in the Appendix) of the data from Experiment 1b to test the effect of degree of evaluation for DPros — the estimate of the model, the corresponding 95% credible interval (95% CrI) and the posterior probability (Post. Prob.). Effects for which the credible interval excludes zero are shown in bold.

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CrI | Post. prob. |

| Degree of eval (DPro) | 0.10 | [0.03, 0.17] | 1.00 |

Results of the statistical analysis (Model (7) in the Appendix) of the data from Experiment 1b to test the effect of degree of evaluation for DemPros — the estimate of the model, the corresponding 95% credible interval (95% CrI) and the posterior probability (Post. Prob.).

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CrI | Post. prob. |

| Degree of eval (DemPro) | 0.01 | [–0.05, 0.07] | 0.62 |

As further exploratory analyses we (i) visually examined the model’s “conditional effects” for the two pronouns (Figure 2(b)), which are the model’s predicted proportions of responses for DemPros and DPros given the data, and (ii) tested the effect of degree of evaluation separately for the DPros and DemPros (Models (6) and (7), respectively, in the Appendix, and Tables 6 and 7). In the conditional effects (Figure 2(b)), for DPros, the model predicted an increase in the proportion of 6 and 7 responses for an increase in degree of evaluation, and a decrease in the proportion of 1–5 responses for a decrease in degree of evaluation. On the other hand, for DemPros there was no influence of degree of evaluation on the proportion of any response.

3.2.4 Discussion

The results of Experiment 1b showed some evidence for an improvement in the acceptability of DPros in evaluative expressions with stronger evaluation. Although this was mainly an exploratory study, it revealed a graded influence of evaluation on the acceptability of DPros and gave rise to a new hypothesis that can be experimentally tested. Since the graded influence of evaluation was not part of the original hypothesis, the experiment material was not designed so as to vary across a wide range of weak to strong evaluations (see Figure B1 in the Appendix for by-item variations in the evaluation ratings). A future experiment can be designed to test this hypothesis by taking into consideration a wider range of evaluations.

4 General discussion

We reported two offline studies with the goal of testing the predictions of the analysis proposed in Section 3.1. According to that analysis, perspectivally prominent abstract speakers/narrators are represented as discourse referents that become the highest ranked elements on the prominence scale relevant only for DPros but not for DemPros. In the absence of such a discourse referent, the second highest ranked element on the scale, the respective aboutness topic, becomes the highest ranked one. For DemPros, the discourse referent functioning as the aboutness topic is the highest ranked element available on the prominence scale, irrespective of the presence or absence of the abstract speaker/narrator.

The results of Experiment 1a are consistent with our hypothesis and provide empirical evidence for the assumption that DPros can pick up a discourse referent that is information structurally prominent (i.e. the aboutness topic) when the abstract speaker/narrator is prominent as perspective-taker through evaluative expressions, while DemPros cannot pick up such discourse referents. The results of Experiment 1b further suggest that the sensitivity of DPros to evaluation is graded — the stronger the evaluation the more suitable the use of DPros (while it makes no difference whether the evaluation is positive or negative). This is also consistent with our hypothesis, since it is plausible that a high degree of evaluation enhances the prominence of the discourse referent corresponding to the abstract speaker/narrator, while it decreases the prominence of the discourse referent corresponding to the aboutness topic.

Despite the predicted interaction of pronoun type and evaluation in Experiment 1a, the relatively good ratings in the acceptability task across all conditions remain an open question, especially the rating for DPros in neutral contexts. One reason for this could be the competition with other referential forms in the experimental setting, but this explanation can be discarded on the basis of a follow-up study with personal pronouns (cf. footnote 3), which yielded comparable ratings. The reason for the high ratings for DemPros may be due to the written modality. These effects motivate new hypotheses that should be tested experimentally. However, they are orthogonal to the hypothesis tested here. In a similar vein, experimentally manipulating and testing the graded influence of evaluation on the prominence scale is also a topic for future research.

Let us now return to the differences between DPros and DemPros reported in Section 2.3 that were found in prior empirical work: (i) they differ along the scale of language register and modality — DemPros prefer formal language and DPros prefer informal language and the spoken modality (Patil et al. 2020; Bader et al. ms.; Patterson et al. ms.), (ii) there is weaker evidence suggesting that DemPros have a stronger last-mentioned preference than DPros (Patterson & Schumacher 2021), whereas (iii) DPros have a more sustained referential shift potential than DemPros (Fuchs & Schumacher 2020).

Concerning (i), we suggest that the correlation between language register and modality is influencing the difference in preferences for the two demonstrative pronouns. Depending on the register and modality features of language under consideration a suitable pronoun is chosen. There is a general tendency for language in the informal register to be subjective and perspective-dependent, and to be realized in the spoken modality. On the other hand, there is a general requirement for formal language not to be subjective and perspective-dependent, and a tendency for it to be realized in the written modality. When talking informally, it is acceptable to express subjective judgements and evaluations, in contrast, when speaking or writing in the formal register, neutrality and objectivity are the ideals to strive for. It, therefore, makes sense that a type of pronoun whose distinguishing feature is sensitivity to perspective taking, i.e. the DPro, is preferred in informal register and the spoken modality, while a type of pronoun that is inherently insensitive to perspective, i.e. the DemPro, is preferred in formal register.

With respect to (ii), the stronger last-mentioned preference of DemPros may be derived from the fact that the most prominent entity on the relevant scale is the aboutness topic (which is typically the first-mentioned entity of the utterance), leaving only the last-mentioned referent as a candidate for coreference (given that most experimental contexts to date make available only two potential candidates5). By contrast, the relevant scale for the DPro may include a prominent perspective-taker, hence making available the non-last-mentioned entity as a potential antecedent in these particular cases. Regarding the differences in the forward-looking potential of the two types of demonstratives (iii), the presence of evaluation may also license a more long-lasting referential chain for DPros since the evaluation calls for elaboration. On the one hand, we have seen that the use of DPros is associated with evaluation, and on the other hand, the evaluation may generate a need for more explanation or elaboration, increasing the number of mentions of the respective referent in subsequent discourse.

In sum, our data confirm the important role of perspectival centers for reference resolution (Sells 1987; Reinhart & Reuland 1991; Dubinsky & Hamilton 1998). A referent serves as perspectival center if the propositional content represents his or her thought or viewpoint. This was implemented in the form of evaluative content in the current investigation. In the absence of explicit thoughts or viewpoints, the perspectival center remains unspecified within the discourse representation. Crucially, the two types of demonstrative pronouns show discrete sensitivities to a potential perspectival center: DPros have access to a prominence scale that includes the perspectival center as the most prominent entity and may thus refer to the (lower ranked) aboutness topic. DemPros by contrast rely on a prominence scale that does not include the perspectival center. This explains the different interpretive preferences for DPros and DemPros and indicates that form-specific prominence scales are available for these two types of pronouns (Kaiser & Trueswell 2008).

Notes

- For the DemPro co-reference is not possible, while for the DPro it might only be available marginally. [^]

- For a comparison between this notion of prominence and other related discourse structure notions such as accessibility, salience, attention and referential activation we point readers to von Heusinger & Schumacher (2019). [^]

- The follow-up study was carried out by adding two PPro conditions (evaluative and neutral) to the design of Experiment 1a, which effectively led to a 2×3 design. We collected data from 49 participants on Prolific following the same procedure as in Experiment 1a. The mean acceptability rating across the six conditions was: 4.8 (Eval-DemPro), 5.1 (Neut-DemPro), 5.5 (Eval-DPro), 4.8 (Neut-DPro), 6.2 (Eval-PPro), 6.4 (Neut-PPro). Statistical analysis showed that the Neut-DPro condition was indeed rated lower than the Neut-DemPro and Neut-PPro, however, we consider the mean rating of 4.8 to be high for DPros in a neutral context. [^]

- The decision to carry out a follow-up study in the form of Experiment 1b was also influenced by the results of a small pilot study where we collected ratings from four native speakers for the degree of evaluation and tested if the ratings of evaluative conditions were correlated with the degree of evaluation. The statistical analysis showed a clear effect for the DPro-evaluative but no effect for the DemPro-evaluative condition. [^]

- Patterson & Schumacher (2021) tested sentences with three possible referents and found that the respective last-mentioned referent was preferred over the other two, with gradient differences for the three potential referential candidates. For sentences with ditransitive verbs or more generally contexts with more than two referential candidates, we tentatively propose that prominence ranking is based on the interaction of different scales: A scale on which the respective aboutness topic is ranked higher than the non-topical referents and a scale that considers edge placement (i.e. the last-mentioned referent), among others. [^]

Abbreviations

m = masculine, F = feminine, REFL = reflexive

Data availability/Supplementary files

All materials, data and analysis are available at: https://osf.io/kwna3/

Ethics and consent

The studies involving human participants have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were reviewed and approved by the Ethikkommission der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Sprachwissenschaft (DGfS). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Funding information

This research has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the SFB 1252 “Prominence in Language”—project number 281511265—in the projects C05 “Discourse referents as perspectival centers” and C07 “Forward and backward functions of discourse anaphora” at the University of Cologne, Germany.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Johannes Hagen, Felix Jüstel, Magdalena Repp and Janne Schmandt for their assistance in stimuli construction. We would also like to thank the three reviewers who helped us improve the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Altshuler, Daniel & Maier, Emar. 2020. Death on the freeway: Imaginative resistance as narrator accommodation. In Frana, Ilaria & Benito, Paula Menendez & Bhatt, Rajesh (eds.), Making worlds accessible: Festschrift for Angelika Kratzer, Amherst: UMass ScholarWorks.

Altshuler, Daniel & Maier, Emar. 2022. Coping With Imaginative Resistance. Journal of Semantics 39(3). 523–549. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffac007

Bader, Markus & Portele, Yvonne & Schäfer, Alice. ms. Semantic bias in the interpretation of german personal and demonstrative pronouns.

Barr, Dale J. & Levy, Roger & Scheepers, Christoph & Tily, Harry J. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68(3). 255–278. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001

Bürkner, Paul-Christian & Vuorre, Matti. 2019. Ordinal regression models in psychology: A tutorial. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2(1). 77–101. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/2515245918823199

Carpenter, Bob & Gelman, Andrew & Hoffman, Matthew & Lee, Daniel & Goodrich, Ben & Betancourt, Michael & Brubaker, Marcus & Guo, Jiqiang & Li, Peter & Riddell, Allen. 2017. Stan: A probabilistic programming language. Journal of Statistical Software, Articles 76(1). 1–32. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v076.i01

Dowty, David. 1991. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67(3). 547–619. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1991.0021

Dubinsky, Stanley & Hamilton, Robert. 1998. Epithets as antilogophoric pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 29(4). 685–693. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4179042. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/002438998553923

Fuchs, Melanie & Schumacher, Petra B. 2020. Referential shift potential of demonstrative pronouns – Evidence from text continuation. In Demonstratives in discourse, 185–213. Language Science Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4055826

Harris, Jesse A. & Potts, Christopher. 2009. Perspective-shifting with appositives and expressives. Linguistics and Philosophy 32(6). 523–552. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-010-9070-5

Harris, Jesse Aron. 2012. Processing perspectives. Doctoral Dissertations Available from Proquest. AAI3498347. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations/AAI3498347.

Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. & Primus, Beatrice. 2015. Prominence beyond prosody – a first approximation. In Dominicis, Amedeo De (ed.), Ps-prominences: Prominences in linguistics. proceedings of the international conference, 38–58. Viterbo: DISUCOM Press. https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/24935/.

Hinterwimmer, Stefan & Bosch, Peter. 2016. Demonstrative pronouns and perspective. In Grosz, Patrick & Patel-Grosz, Pritty (eds.), The impact of pronominal form on interpretation, 189–220. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781614517016-008

Hinterwimmer, Stefan & Bosch, Peter. 2017. Demonstrative pronouns and propositional attitudes. In Patel-Grosz, Pritty & Grosz, Patrick Georg & Zobel, Sarah (eds.), Pronouns in embedded contexts at the syntax-semantics interface, 105–144. Springer (Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56706-8_4

Hinterwimmer, Stefan & Brocher, Andreas & Patil, Umesh. 2020. Demonstrative Pronouns as Anti-Logophoric Pronouns: An Experimental Investigation. Dialogue & Discourse 11(2). 110–127. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5087/dad.2020.204

Kaiser, Elsi & Trueswell, John C. 2008. Interpreting pronouns and demonstratives in finnish: Evidence for a form-specific approach to reference resolution. Language and Cognitive Processes 23(5). 709–748. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01690960701771220

Patil, Umesh & Bosch, Peter & Hinterwimmer, Stefan. 2020. Constraints on german diese demonstratives: language formality and subject-avoidance. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 5(1). 14. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.962

Patterson, Clare & Patil, Umesh & Ventura, Caterina & Schumacher, Petra B. & Hinterwimmer, Stefan. ms. Not modality but register impacts the choice of demonstrative pronouns.

Patterson, Clare & Schumacher, Petra B. 2021. Interpretation preferences in contexts with three antecedents: examining the role of prominence in german pronouns. Applied Psycholinguistics 42(6). 1427–1461. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716421000291

Patterson, Clare & Schumacher, Petra B. & Nicenboim, Bruno & Hagen, Johannes & Kehler, Andrew. 2022. A bayesian approach to german personal and demonstrative pronouns. Frontiers in Psychology 12. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.672927

Portele, Yvonne & Bader, Markus. 2016. Accessibility and referential choice: Personal pronouns and d-pronouns in written german. Discours 18. 9188. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/discours.9188

Primus, Beatrice. 1999. Cases and thematic roles. Berlin, New York: Max Niemeyer Verlag. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110912463

R Core Team. 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1981. Pragmatics and linguistics: An analysis of sentence topics. Philosophica 27. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21825/philosophica.82606

Reinhart, Tanya & Reuland, Eric. 1991. Anaphors and logophors: an argument structure perspective 283–322. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511627835.015

Schumacher, Petra B. & Patterson, Clare & Repp, Magdalena. 2022. Die diskursstrukturierende Funktion von Demonstrativpronomen. In Gianollo, Chiara & Jędrzejowski, Łukasz & Lindemann, Sofiana I. (eds.), Paths through meaning and form. Festschrift offered to Klaus von Heusinger on the occasion of his 60th birthday, 216–220. Köln: Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Köln. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18716/omp.3.c55

Sells, Peter. 1987. Aspects of logophoricity. Linguistic Inquiry 18(3). 445–479. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178550.

Veríssimo, João. 2021. Analysis of rating scales: A pervasive problem in bilingualism research and a solution with bayesian ordinal models. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 24(5). 842–848. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728921000316

von Heusinger, Klaus & Schumacher, Petra B. 2019. Discourse prominence: Definition and application. Journal of Pragmatics 154. 117–127. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378216619305776. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.07.025

Voigt, Robert. 2022. Der Einfluss von Kontrast auf die Verwendung deutscher Personalpronomen und pronominaler Demonstrative. In Gianollo, Chiara & Jędrzejowski, Łukasz & Lindemann, Sofiana I. (eds.), Paths through meaning and form. Festschrift offered to Klaus von Heusinger on the occasion of his 60th birthday, 264–269. Köln: Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Köln. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18716/omp.3.c55

Weinert, Regina. 2011. Demonstrative vs personal and zero pronouns in spoken German. German as a Foreign Language 1. 71–98.

Wiemer, Björn. 1996. Die personalpronomina er. vs. der. und ihre textsemantischen funktionen. Deutsche Sprache 24. 71–91.

Zehr, Jeremy & Schwarz, Florian. 2018. PennController for internet based experiments (IBEX). DOI: http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MD832

Zifonun, Gisela & Hoffmann, Ludger & Strecker, Bruno & Ballweg, Joachim. 1997. Grammatik der deutschen Sprache, vol. 1. Berlin: de Gruyter.