1 Introduction

The defining property of accomplishment verbs is that they “proceed toward a terminus which is logically necessary to their being what they are” (Vendler 1967: 101). Thus, a base accomplishment VP, comprised of a dynamic verb and a quantized incremental Theme argument (e.g., Krifka 1989), is integrally associated with a telos (Garey 1957), or a point of culmination (Parsons 1990). Combined with the culmination requirement carried by the perfective (pfv) operator, such telic predicates may only denote culminated events; namely, events in which the referent of the Theme argument has fully undergone the change specified by its governing verb (e.g., Filip 2017: 169). So, for example, to eat an apple entails to eat an apple completely (Tenny 1994: 22–23), and the sentence in (1) would be false in the event that the referent of an apple is only partially eaten.

- (1)

- Adam ate an apple.

Over the past decades, however, it has been increasingly recognized that pfv telic accomplishments do in fact allow for varying degrees of culmination requirements crosslinguistically, and specifically, that non-culminated interpretations of pfv telic accomplishments are more widely available than previously assumed (for a detailed list, see Martin 2019; Persohn 2022). Hence, in many languages, the culmination inference carried by pfv telic accomplishments is defeasible, as demonstrated for Mandarin (2a), Hindi (2b), and English (2c), where the second clause felicitously cancels the culmination inference of the first clause.

- (2)

- a.

- Ta

- he

- hua-le

- draw-le

- yi-fu

- one-cl

- hua,

- picture

- keshi

- but

- mei

- not

- hua-wan.

- draw-finish.

- ‘He drew a picture, but he didn’t finish drawing it.’ (Mandarin: Soh & Kuo 2005)

- b.

- Maya-ne

- Maya-erg

- biskuT-ko

- cookie-acc

- khaa-yaa

- eat-pfv

- par

- but

- us-e

- it-acc

- puuraa

- full

- nahiin

- not

- khaa-yaa.

- eat-perf

- ‘Maya ate a cookie, but not completely.’ (Hindi: Arunachalam & Kothari 2011)

- c.

- She ate the sandwich but as usual she left a few bites. (Hay et al. 1999)

The willingness of English speakers to accept pfv telic accomplishments as descriptions of partially completed events is also demonstrated experimentally (e.g., Arunachalam & Kothari 2011).1

The Slavic pfv, on the other hand, has been consistently argued throughout the theoretical literature to enforce strict culmination requirements on telic accomplishments within its scope, such that non-culminating interpretations are entirely disallowed for such forms (e.g., Filip 2000; 2008; 2017; Grønn 2003; Kazanina & Philips 2007; Martin 2019; Smith 1991/1997).

Furthermore, in Slavic languages such as Russian, culmination is taken to be semantically entailed by pfv telic accomplishments, rather than defeasibly implicated (e.g., Comrie 1976; Filip 2000; 2008; 2017). This is then used to explain the supposed contradiction created in (3), between the putatively entailed culmination of the first clause, and its cancellation in the second clause.

- (3)

- Masha

- Masha.

- s’ela

- pfv-ate-sg-f

- buterbrod

- sandwich-acc

- (#no

- but

- kusočeck

- piece.small

- ostavila).

- left.

- ‘Masha ate the/a sandwich (#but left a small piece).’

Experimental work on adult native speakers’ interpretations of pfv telic accomplishments is rather limited. To our knowledge, the only available source for relevant data is a handful of acquisition and L2 research (acquisition of Russian: Kazanina & Phillips 2007; acquisition of Polish: van Hout 2008; Russian L2: Slabakova 2005; Nossalik 2009; see also van Hout et al. 2010 and van Hout 2018 for a survey of crosslinguistic acquisition data). The primary finding of these studies is that Russian and Polish native adult speakers systematically link the perfective form of the verb with completed events and the imperfective with ongoing processes. Crucially, though, none of these studies directly test the availability of non-culminating interpretations of pfv telic accomplishments. The current study is the first to directly test this in adult native speakers of Russian. Moreover, there exists no prior attempt to systematically probe speakers’ judgments regarding the assumed contradiction in (3) for Russian. The current study aims to fill this gap.

Contrary to the widely assumed view presented above, that Slavic languages such as Russian are uniquely strict in terms of the culmination inference encoded by their pfv telic accomplishments, we want to show that under certain conditions, pfv telic accomplishments may be licensed as descriptions of partially completed events, even in Russian. And further, that Russian speakers may in fact judge sentences such as (3) – where a pfv telic accomplishment is followed by a cancellation phrase – as acceptable.

To this end, we designed a gradable acceptability judgment task, an experimental paradigm which, to the best of our knowledge, has not yet been used to evaluate the availability of Russian non-culminating interpretations of pfv accomplishments. Moreover, and more broadly, gradable acceptability tasks have rarely been used to probe speakers’ interpretations of pfv telic accomplishments in other languages. Indeed, while there is quite a robust crosslinguistic body of experimental research on the topic (e.g., Arunchalan & Kothari 2011; Hacohen & Wolf 2017; van Hout 1998; Liu 2018; Ogiela & Schmitt & Casby 2014; Schulz & Penner 2002; Wright 2014), it almost exclusively comprises studies employing binary judgment tasks.2 An interesting exception is Aoki & Nakatani (2013), who used a gradable acceptability task to test the claim that culmination in Japanese accomplishments is an implicature (and therefore cancellable) (cf. Tsujimura’s 2003). More recently, Chen (2018) used a Likert-type scale to test interpretations of individual verbs in Mandarin Chinese. There is also some existing work from L2/bilingualism research that uses acceptability scales (see, e.g., Slabakova 2000; 2001; Yin & O’Brien 2019), but it is concerned primarily with issues such as crosslinguistic influence rather than telicity per se. Hence, although some experimental work on telicity that elicits non-binary data does exist, it is either restricted to language-specific lexical features of individual verbs or provides little information as to the intricate complexities of the linguistic phenomenon as such.

The rationale for using a gradable paradigm, rather than the more commonly used binary judgment task, is that the former better reflects the nature of acceptability judgments. Unlike grammaticality judgments, which are typically categorical (a sentence is either grammatical or not), acceptability judgments are considered inherently gradable (Chomsky 1965; Schütze 2016: 62, Sprouse 2007 and references therein). Moreover, since “[i]n natural conversation, there are many moves available to an interlocutor who is asked to judge the validity of a statement” (Sikos & Kim & Grodner 2019: 2), reducing speakers’ available choices to only two possible response options artificially constrains behavior (ibid. and cf. Sorace & Keller 2005). Hence, the use of a gradable judgment paradigm is paramount to exposing speakers’ true judgments. As our findings demonstrate, this methodological choice is particularly crucial when investigating the availability of non-culmination crosslinguistically, and in Russian, in particular.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

A group of 33 native Russian speakers were recruited online through Russian social media (12 = F, 16 = M, 5 = no gender reported). Participation was on a voluntary basis and no compensation was offered. Participants came from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, and all declared that Russian was their main language from birth. Age of participants ranged from 18–64, with a median age of 37. The results of three additional participants were excluded from the analysis after a post hoc examination revealed that their responses consisted almost entirely of the highest ratings (4-scores).

2.2 Design and Material

In our design, we manipulated the following variables: aspectual frame (Perfective, Perfective followed by Cancellation phrase, Imperfective); verb type (Creation, Consumption, Destruction); event type (Partial Completion, Full Completion, No event). The verbal stimuli consisted of eight accomplishments composed of an incremental transitive verb followed by a singular count noun object DP. The choice of VPs was mainly motivated by such factors as frequency, familiarity, and ease of depiction. In light of previous studies discussing potential effects of verb-type on the availability of (non-)culminating interpretations (see e.g., Martin 2019; Ogiela et al. 2014; van Hout 1998; Wright 2014), we also wanted to control for verb type. A list of the base accomplishments used is provided in Table 1.

Base accomplishments tested.

| Creation | Consumption | Destruction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

Each of the eight accomplishments appeared in three aspectual frames, as shown in Table 2 for ‘draw star’.

Experimental manipulation of aspectual frames.

| Condition 1: Perfective (pfv) |

|

| Condition 2: Perfective + cancellation (pfv+cncl) |

|

| Condition 3: Imperfective (imp) |

|

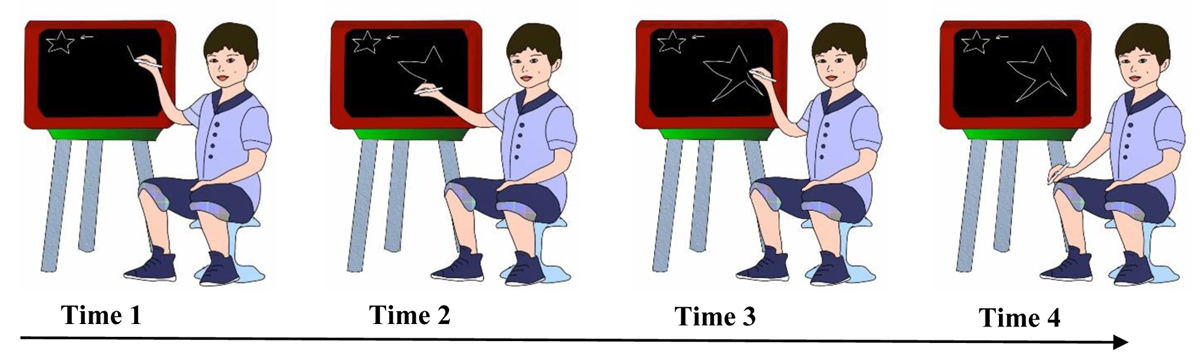

The visual stimuli of the critical items comprised eight short animated clips, depicting a human character performing the action denoted by the eight base accomplishments. The scenarios depicted in the clips unfolded naturally towards their intended endpoint, but they all terminated short before reaching their goal. Note that the events were depicted as approximately 80% completed, similarly to many previous works on the topic (cf. e.g., Kaplan & Raju & Arunachalam 2021). This is illustrated in Figure 1 for ‘draw star’.

In addition to the eight critical items, in which all the events were depicted as partially complete, we also included eight control items. The verbal stimuli in the control items were the same as for the critical items, namely, the eight base accomplishments appearing in three aspectual frames, but the visual stimuli were manipulated, such that five of the clips depicted completed events, and the three remaining clips depicted scenarios in which the intended action did not even begin. The rationale for this unequal division is that in addition to providing the visual control to the partially completed events depicted in the critical items, the control items also served to counterbalance expected responses. Specifically, we wanted to increase the number of low acceptability responses so as to not create a bias towards high acceptability.

In total, there were 48 trials and we used a within-subject design, i.e., all participants were asked to judge all the trials.

2.3 Procedure

The experiment was conducted online using the Qualtricsxm platform. The visual stimuli were presented to all participants in one fixed pseudo-randomized order, while the verbal stimuli were fully randomized for each participant and for each item. Randomization was done automatically using the appropriate feature available through Qualtrics.

At the beginning of each experiment, the participant was told that they would be presented with video clips accompanied by sentences in Russian, and that their task was to evaluate how likely it would be for a native speaker to produce such a sentence. Response options were noted on a 4-point scale, each explicitly labeled: 1 (ni maleišego šansa ‘not a chance’), 2 (vrjad li ‘not likely’), 3 (vozmožno, xotja čto-to ne tak ‘possible, but slightly off’), 4 (vpolne verojatno ‘highly likely’). Importantly, this was not a preference task; the participants were specifically instructed to rate each of the sentences independently, and not relative to one another. This type of joint presentation, where the various sentence types are presented side by side, has been found to significantly enhance the sensitivity of acceptability measures (see Marty & Chemla & Sprouse 2020). Note also that no midpoint was used in the scale. This was done to control for a potential central tendency bias (cf. e.g., Douven 2018; Stevens 1971) and in order to create a forced-choice scale (cf. Chyung et al. 2018).

3. Result and analysis

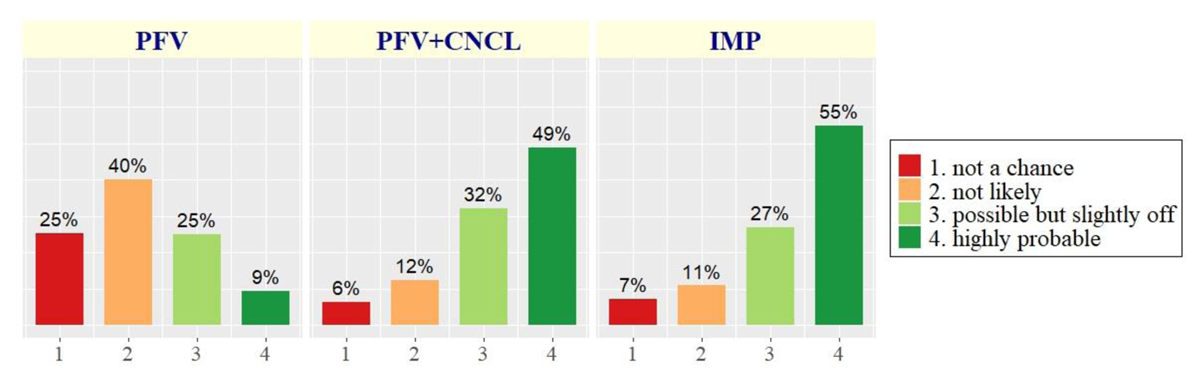

The purpose of our study was to experimentally test whether non-culminated readings of perfective telic accomplishments are available for Russian speakers. Equally important was our aim to test whether Russian speakers accept sentences in which such pfv telic accomplishments are followed by a cancellation phrase. Recall that participants were asked to judge how likely it would be for a native speaker of Russian to use the sentences in the verbal stimuli as descriptions of the events presented in the videos. The distribution of responses across aspectual frames is plotted in Figure 2.3

First, the graph reveals that in the pfv condition, a total of 65% of data points received low acceptability scores (25% and 40% 1- and 2-ratings, respectively). This confirms that Russian pfv telic accomplishments, just like pfv telic accomplishments crosslinguistically, generally denote culmination, and are therefore deemed by speakers to be largely ill-suited as descriptions of events that do not reach their intended endpoint. Still, we also find that as much as 34% of the time, participants judged such forms as “possible” (25%) or even “highly likely” (9%) descriptions of partially completed events. This is unexpected, given the widely accepted view in the literature that the Russian pfv strongly entails culmination, and should therefore be entirely unacceptable in such contexts.

Even more surprising, though, are the findings from the pfv+cncl condition. Here we see that participants freely accept sentences in which pfv telic accomplishments are followed by a cancellation phrase, with a total 81% of judgments being either “highly likely” (49%) or “possible” (32%). Low acceptability scores comprise merely 18% of the data points in this condition. Interestingly, this distribution is essentially identical to the imp data, which is not predicted to carry any inference of culmination.

A statistical analysis of the three conditions in the partially completed scenarios revealed a main effect of aspectual frame (Friedman Chi-Square = 41.54, p < 0.001, df = 2). However, this effect was exclusively due to the distribution in the pfv. Indeed, a post hoc Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test confirmed that the distributions of the pfv+cncl and the imp were not significantly different (p = 0.470).

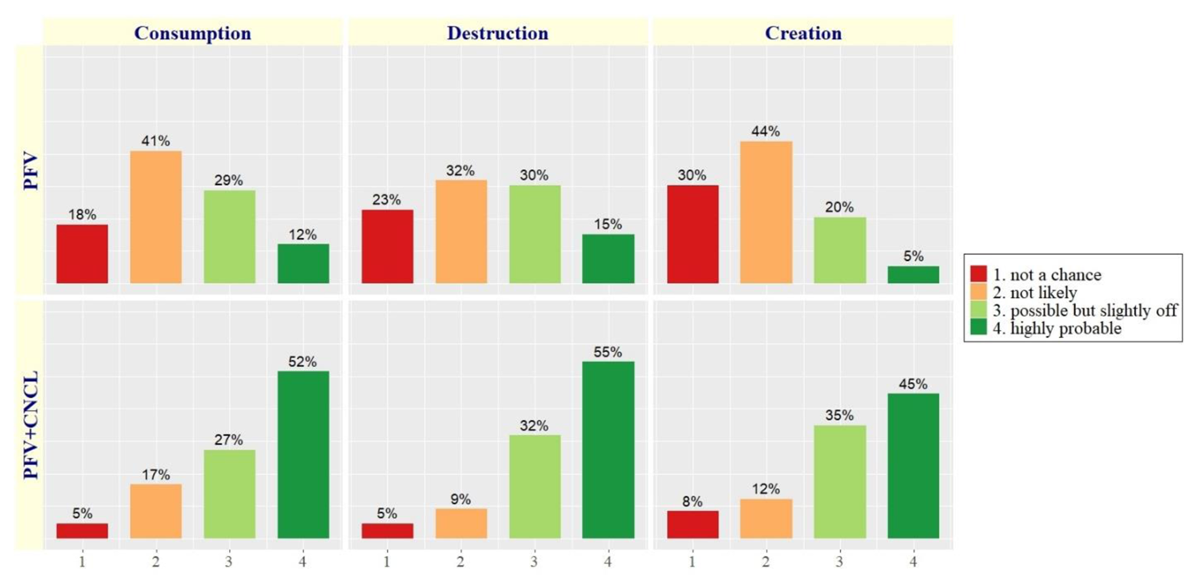

It is also interesting to examine the response distribution across verb types in the two critical conditions, the pfv and the pfv+cncl. These data are presented in Figure 3.

As is clearly visible from the graphs, response distributions were essentially identical, regardless of verb type. This was confirmed by a Friedmann Chi-Square, which did not yield a significant effect of verb type in either of the aspectual frames (p = 0.1975 for pfv, p = 0.0509 for pfv+cncl).

4. General discussion

It is a long established and widely accepted view in the event semantics literature that Slavic languages constitute a language family which is particularly strict in terms of the culmination inference encoded by pfv telic accomplishments (e.g., Filip 2017). This inference, it is argued, amounts to an entailment in Slavic languages, and is therefore non-defeasible (e.g., Comrie 1976; Filip 2000; 2008; 2017). This, in turn, is claimed to be the reason why in Slavic languages, such as Russian, pfv telic accomplishments are only allowed as descriptions of fully completed events, and why sentences in which a pfv telic accomplishment followed by a cancellation phrase purportedly result in a contradiction (e.g., Martin 2019).

Our study suggests that this commonly held typology may need to be revised. Our primary finding is that while pfv telic accomplishments in Russian do generally denote culmination, Russian speakers, nevertheless, also allow for a considerable degree of non-culminating interpretations of such constructions. Furthermore, and even more surprisingly, our data reveal high acceptability judgments for sentences in which pfv telic accomplishments are followed by a cancellation phrase. It is particularly striking that the response pattern in the pfv+cncl condition was not significantly different from the judgments yielded in the imperfective condition. This finding is interesting first, because to our knowledge, it is the first and only time that acceptability judgments of such constructions in Russian have been directly elicited in a systematic, experimental setting. Perhaps more importantly, though, such a finding is striking because it indicates that contra to what has been consistently argued in the theoretical literature, Russian pfv telic accomplishments followed by a cancellation phrase do not necessarily result in a contradiction.

The interesting question to ask here is what exactly is being canceled. In our view, what is being canceled is not the culmination per se, but rather the maximal interpretation of culmination (cf. Martin 2019; Martin & Demirdache 2020), namely, the point “beyond which the event cannot proceed” (Declerck 1991: 121; Depraetere 1995: 3). Hence, the Russian perfective does encode event completion (unlike, e.g., the perfective in Mandarin or Hindi), but it also allows for non-maximal interpretations of pfv telic accomplishments. In other words, and following Martin’s (2019) terminology, while Russian has no non-culminating accomplishments, our study shows that it does have non-maximal accomplishments on par with what has been reported for languages such as English and Spanish (e.g., Martin & Arunachalam 2022). Further research is needed to fully develop this preliminary proposal.

In addition to the interesting theoretical implications of the current study, it also highlights the importance of methodology. In particular, it demonstrates the unique insight gained through the use of gradable acceptability judgments. It has been argued from a theoretical perspective, that the cancellation of the culmination inference in sentences like (3) results not in contradiction, but rather in “degraded acceptability” (Kennedy & Levin 2008: 160).4 But what does “degraded acceptability” mean from an experimental psycholinguistic perspective? If the measure used to collect such acceptability judgments exclusively employs binary judgment tasks, it can only mean that more speakers find it unacceptable. But what if that is not all it means? What if some of the “yes/acceptable” responders would actually prefer to say something more like “yes, to some extent/sort of”? Conversely, what if the “no/unacceptable” actually masks a “not so much” answer? Clearly, this is very different from simply averaging across speakers and arriving at some average response per predicate/sentence-type. Using a gradable acceptability task, as we have done in the current study, allows us to uncover such subtle meaning intricacies that may be glossed over with a binary response paradigm.

In sum, what our findings suggest is that in contrast to the widely accepted view, Russian in particular, and arguably Slavic languages more broadly, are not unique with respect to the culmination inference encoded by their pfv telic accomplishments. This, in turn, provides some preliminary support for a more universalist view of event semantics, whereby the range of crosslinguistic differences is more restricted than previously assumed. However, we emphasize that such a suggestion is merely speculative at this point. While it may still be the case that the culmination inference of pfv accomplishments is indeed stricter in Russian than in other languages (cf. Minor et al. 2022), the contribution of the current study is in showing that Russian has some degree of tolerance in this respect. As such, the current study provides a necessary first step that we hope will inspire and initiate extensive research in the near future.

Notes

- See also Foppolo et al. (2021) for an interesting recent study investigating the time course of telicity interpretations in Italian. The study uses eye-tracking to test when and how the culmination inference of telic predicates arises during processing. Most relevant for the current study, though, are the results from an offline acceptability judgment task that was used as a pre-test for the main experiments. The results show that Italian speakers (N = 37) accept perfective telic sentences as descriptions of incomplete events at around 30%. [^]

- Interestingly, much of the available experimental data, particularly those obtained in the early years, come from acquisition studies. Adult data – though for the most part not the focus of the research – are nonetheless almost always collected in these studies. [^]

- For considerations of space, only data from the partially completed scenarios are discussed here. See Appendix for results of the control items. [^]

- The original claim is made for degree achievements in English. [^]

Data availability

The Appendix with additional results, as well as all the raw data and analysis scripts, can be found at this link: https://osf.io/g4637/?view_only=4a355520602d44968e72eff6b77e512f

Abbreviations

pfv = Perfective, imp = Imperfective, acc = Accusative, vp = Verb Phrase, cl = Clitic, erg = Ergative, gen = Genitive, cncl = Cancellation, 1 = 1st person, 2 = 2nd person, 3rd = third person, sg = singular, pl = plural, f = feminine, m = masculine

Ethics and consent

The Human Subjects Research Committee of Ben-Gurion University has reviewed and approved this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Aoki, Natsuno & Nakatani, Kentaro. 2013. Process, telicity, and event cancellability in Japanese: A questionnaire study. Journal of the English Linguistic Society of Japan 30. 257–263.

Arunachalam, Sudha & Kothari, Anubha. 2011. An experimental study of Hindi and English perfective interpretation. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 4(1). 27–42. https://ojs.ub.unikonstanz.de/jsal/index.php/jsal/article/download/35/21/0. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/jsa.2011.0020

Chen, Jidong. 2018. “He killed the chicken, but it didn’t die”: An empirical study of the lexicalization of state change in Mandarin monomorphemic verbs. Journal of Chinese Language and Discourse 9(2). 136–161. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/cld.17007.che

Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21236/AD0616323

Chyung, Seung Youn (Yonnie) & Swanson, Ieva & Roberts, Katherine & Hankinson, Andrea. 2018. Evidence-based survey design: The use of continuous rating scales in surveys. Performance Improvement 57(5). 38–48. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21763

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge University Press.

Declerck, Renaat. 1991. Tense in English: Its structure and use in discourse. London: Routledge

Depraetere, Ilse. 1995. On the necessity of distinguishing between (un)boundedness and (a)telicity. Linguistics and philosophy 18(1). 1–19. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00984959

Douven, Igor. 2018. A Bayesian perspective on Likert scales and central tendency. Psychonomic bulletin & review 25(3). 1203–1211. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1344-2

Filip, Hana. 2000. The quantization puzzle. Events as grammatical objects 39. 96.

Filip, Hana. 2008. Events and maximalization: The case of telicity and perfectivity. In Rothstein, Susan (ed.), Theoretical and crosslinguistic approaches to the semantics of aspect, 217–256. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.110.10fil

Filip, Hana. 2017. The semantics of perfectivity. Italian journal of linguistics 29(1). 167–200.

Foppolo, Francesca & Bosch, Jasmijn E. & Greco, Ciro & Carminati, Maria N. & Panzeri, Francesca. 2021. Draw a star and make it perfect: Incremental processing of telicity. Cognitive Science 45(10). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13052

Garey, Howard B. 1957. Verbal aspects in French. Language 33. 91–110. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/410722

Grønn, Atle. 2003. The semantics and pragmatics of the Russian Factual Imperfective. (Doctor Artium Thesis, University of Oslo. Oslo, NO). Retrieved from: https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/TVkMjY5Z/thesis.pdf.

Hacohen, Aviya & Wolf, Lavi. 2017. On compositional (a)telicity in adult and child Hebrew. Paper presented at TELIC 2017: Workshop on Non-culminating, Irresultative and Atelic Readings of Telic Predicates, University of Stuttgart, 12–14 January.

Hay, Jennifer & Kennedy, Christopher & Levin, Beth. 1999. Scalar structure underlies telicity in “Degree Achievements”. In Matthews, Tanya & Strolovitch, Devon (eds.), Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (=SALT) IX, 127–144. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v9i0.2833

Kaplan, Max J. & Raju, Amulya & Arunachalam, Sudha. 2021. Real-time processing of event descriptions for partially-and fully-completed events: Evidence from the visual world paradigm. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 6(1). 118–132. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v6i1.4954

Kazanina, Nina & Phillips, Colin. 2007. A developmental perspective on the Imperfective Paradox. Cognition 105. 65–102. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.09.006

Kennedy, Christopher & Levin, Beth. 2008. Measure of change: The adjectival core of degree achievements. In McNally, Louise & Kennedy, Christopher (eds.), Adjectives and adverbs: Syntax, semantics and discourse, 156–182. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krifka, Manfred. 1989. Nominal reference, temporal constitution and quantification in event semantics. In Bartsch, Renate & van Benthem, Johan & van Emde Boas, Peter (eds.), Semantics and contextual expressions, 75–115. Dordrecht: Foris Publications. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110877335-005

Liu, Jinhong. 2018. Non-culminating accomplishments in child and adult Chinese: An experimental study. Nantes, France: University of Nantes PhD dissertation.

Martin, Fabienne. 2019. Non-culminating accomplishments. Language and Linguistics Compass 13(8). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12346

Martin, Fabienne & Arunachalam, Sudha. 2022. Optional se constructions and flavours of applicatives in Spanish. Isogloss. Open Journal of Romance Linguistics 8(4). 1–34. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5565/rev/isogloss.153

Marty, Paul & Chemla, Emmanuel & Sprouse, Jon. (2020). The effect of three basic task features on the sensitivity of acceptability judgment tasks. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 5(1). 72. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.980

Minor, Serge & Mitrofanova, Natalia & Guajardo, Gustavo & Vos, Myrte & Ramchand, Gillian. 2022. Temporal information and event bounding across languages: Evidence from visual world eyetracking. Talk at Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 32. https://osf.io/tv3b8/. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v1i0.5340

Nossalik, Larissa. 2009. L2 Acquisition of the Russian Telicity Parameter. In Bowles, Melissa & Ionin, Tania & Montrul, Silvina & Tremblay, Annie (eds.), Proceedings of the 10th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2009), 248–263. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Ogiela, Diane A. & Schmitt, Christina, & Casby, Michael W. 2014. Interpretation of verb phrase telicity: Sensitivity to verb type and determiner type. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 3(57). 865–875. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1044/2013_JSLHR-L-12-0271

Parsons, Terence. 1990. Events in the semantics of English: A study in subatomic semantics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Persohn, Bastian. 2022. Non-culmination in two Bantu languages. Studies in Language. International Journal sponsored by the Foundation “Foundations of Language” 46(1). 76–132. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/sl.20051.per

Schulz, Petra & Penner, Zvi. 2002. How you can eat the apple and have it too: Evidence from the acquisition of telicity in German. In Costa, João & Freitas, Maria João (eds.), Proceedings of the 2001 Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition (GALA 2001), 239–246. Lisbon: Associação Portuguesa de Linguística.

Schütze, Carson T. 2016. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_603356

Sikos, Les & Kim, Minjae & Grodner, Daniel J. 2019. Social context modulates tolerance for pragmatic violations in binary but not graded judgments. Frontiers in Psychology. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00510

Slabakova, Roumyana. 2000. L1 transfer revisited: The L2 acquisition of telicity marking in English by Spanish and Bulgarian native speakers. Linguistics 38(4). 739–70. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/ling.2000.004

Slabakova, Roumyana. 2001. Telicity in the second language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/lald.26

Slabakova, Roumyana. 2005. What is so difficult about telicity marking in L2 Russian? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 8(1). 63–77. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728904002093

Smith, Carlota S. 1991/1997. The parameter of aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-7911-7

Soh, Hooi Ling & Kuo, Jenny Yi-Chun. 2005. Perfective aspect and accomplishment situations in Mandarin Chinese. In van Hout, Angeliek & de Swart, Henriette & Verkuyl, Henk (eds.), Perspectives on aspect, 199–216. Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3232-3_11

Sorace, Antonella & Keller, Frank. 2005. Gradience in linguistic data. Lingua 115. 1497–1524. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2004.07.002

Sprouse, Jon. 2007. Continuous acceptability, categorical grammaticality, and experimental syntax. Biolinguistics 1. 123–134. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5964/bioling.8597

Stevens, Stanley Smith. 1971. Issues in psychophysical measurement. Psychological Review 78(5). 426. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0031324. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/h0031324

Tenny, Carol S. 1994. Aspectual roles and the syntax-semantics interface. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1150-8

Tsujimura, Natsuko. 2003. Event cancellation and telicity. Japanese/Korean Linguistics 12. 388–399.

van Hout, Angeliek. 1998. On the role of direct objects and particles in learning telicity in Dutch and English. In Greenhill, Annabel & Hughes, Mary & Littlefield, Heather & Walsh, Hugh (eds.), Proceedings of 22th Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD 22), 397–408. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

van Hout, Angeliek 2008. Acquiring perfectivity and telicity in Dutch, Italian and Polish. Lingua 118(11). 1740–1765. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2007.08.011

van Hout, Angeliek. 2018. On the acquisition of event culmination. In Syrett, Kristen & Arunachalam, Sudha (eds.), Semantics in Language Acquisition, 96–121. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/tilar.24.05hou

van Hout, Angeliek & Gagarina, Natalia & Dressler, Wolfgang. 2010. Learning to understand aspect across languages. Paper presented at the 35th Boston university conference on language development (BUCLD 35), November 5–7.

Vendler, Zeno. 1967. Linguistics in philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7591/9781501743726

Wright, Tony Allen. 2014. Strict vs. flexible accomplishment predicates. Austin, Texas: University of Texas at Austin PhD dissertation. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/31483.

Yin, Bin & O’Brien, Eth Ann. 2019. Aspectual interpretation and mass/count knowledge in Chinese-English bilinguals. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 9(3). 468–503. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/lab.16032.yin