1 Introduction

Doubling constructions in syntax present a particular challenge to the analyst. Why are some items pronounced more than once when most cannot be? There is a significant body of research on doubling constructions, but most are within the clausal domain.1 Perhaps the best known is the predicate cleft construction, which occurs in a wide range of languages, and typically involves the pronunciation of the verb (phrase) in a clause-peripheral position as well as in the canonical, clause-internal position, as exemplified by the Spanish data in (1).

- (1)

- a.

- Leer,

- read.inf

- Juan

- Juan

- ha

- has

- leído

- read

- un

- a

- libro

- book

- ‘As for reading, Juan has read a book.’ (Vicente 2009: (1a))

- b.

- Leer

- read.inf

- el

- the

- libro,

- book

- Juan

- Juan

- lo

- cl

- ha

- has

- leído

- read

- ‘As for reading the book, Juan has indeed read it.’ (Vicente 2009: (10a))

This paper adds to the existing literature on doubling by looking at a case of DP-internal doubling: what we call framing demonstratives in the Merina dialect of Malagasy, where “framing” refers to the fact that the demonstratives “frame” all other material in the DP. Examples of such demonstratives are given in (2), where we have glossed the initial and final instances of the demonstrative as dem1 and dem2, respectively.

- (2)

- a.

- io

- dem1

- boky

- book

- io

- dem2

- ‘this book’

- b.

- ireo

- dem1

- saka

- cat

- telo

- three

- ireo

- dem2

- ‘those three cats’

- c.

- izany

- dem1

- teny

- word

- mahatezitra

- angry

- izay

- rel

- nolazain-dRabe

- said-Rabe

- izany

- dem2

- ‘those angry words that Rabe said’

Framing is obligatory with demonstratives, with some exceptions to be discussed below.

This paper has two main contributions. First, it describes and analyzes the Malagasy framing demonstrative construction. Our analysis relies on proposals within the predicate cleft literature, specifically Saab (2017), and is successful in accounting for the core set of facts. The central claim of the analysis is that doubling arises from a single syntactic representation of the demonstrative, not two independent representations. Although we do not explore alternatives, we believe that other movement-based analyses of the predicate cleft construction (e.g. Hein 2017; 2018; Arregi & Pietraszko 2021) could also account for the patterns. An important consequence is that doubling/copy constructions exist within the nominal domain. Second, despite a rich descriptive literature, Malagasy nominal syntax is almost completely unexplored (but see Zribi-Hertz & Mbolatianavalona 1999 and Ntelitheos 2012). This paper therefore provides novel proposals regarding the structure of noun phrases, including the syntax of demonstratives.

We begin in Section 2 with a descriptive overview of noun phrases in Malagasy, including a discussion of the distribution of demonstratives and the core properties we need to account for. Section 3 provides a structural analysis of Malagasy DPs, where the DP-internal word order is derived via Roll Up within the lexical domain, and this rolled up constituent then fronts to an inflectional position below DP. We also posit that the base position for demonstratives is low in DP, as the head of DemP just above the lexical domain. In Section 4, we explore two approaches to doubling/copy constructions and the framing demonstrative phenomenon: single representation and dual representation. The single representation derivation involves a single base-generated representation of the demonstrative. Our instantiation of the single representation involves long head movement of Dem-to-D. Adopting theoretical proposals in Saab (2017) leads to doubling of the demonstrative. In our dual representation alternative, there are two independent representations of the demonstrative. Although both approaches can account for the framing word order, Section 5 shows that only the single representation analysis can capture additional facts. Section 6 concludes.

2 Aspects of Malagasy nominals

Malagasy is a western Austronesian language spoken in Madagascar. In this paper we describe the Merina dialect of Malagasy, spoken in and around the capital city, Antananarivo. The Merina dialect, which is the basis for Standard Malagasy, is used in government and media. The unmarked word order is VOS, and the language is strongly head-initial. Word order in the Malagasy nominal is relatively rigid, obeying the generalization in (3). The nominal is head-initial, preceded only by determiner-like elements and demonstratives, discussed further below. As indicated in (3) and illustrated by the data above, the demonstratives are initial and final in the nominal. All other dependents follow the noun head in a relatively fixed order: adjective, possessor, numeral, quantifier, and relative clause.2 Section 3 provides a more detailed discussion of the internal structure of the DP.

- (3)

- Malagasy DP word order (modified from Ntelitheos 2012: 63)

- DEM1/det

- N

- adj

- poss

- num

- quant

- rc

- DEM2

This section provides an overview of the key elements in the noun phrase.

2.1 Determiner-like elements

Malagasy has two determiner-like elements. Conforming to the head-initial nature of the language, these articles appear in a DP-initial position. The default article ny is often translated as ‘the’, but the consensus is that it is not equivalent (Fugier 1999; Law 2006; Keenan 2008; Paul 2009; others). In addition to more usual definite uses, ny allows indefinite or novel readings, as illustrated in (4). There is no overt indefinite article.

- (4)

- a.

- Lalina

- deep

- ny

- det

- fitiavan’

- love

- ny

- det

- Malagasy

- Malagasy

- maro

- many

- an’

- acc

- ilay

- det

- antoko

- party

- vaovao

- new

- ‘The love that many Malagasy have for this new party is deep.’

- b.

- Nokapohiko

- hit.pass.1sg

- ny

- det

- hazo

- tree

- ‘I hit a tree.’ (Fugier 1999: 16–17)

In addition to ny, there is an anaphoric article ilay, which Rajaona (1972) calls deictic. It is used when referring to objects that have been previously mentioned or are otherwise salient, as in (5) and (4a).

- (5)

- Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ilay

- det

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- ‘I want to buy that white car (one that we were talking about).’

While ny is unmarked for number, ilay is typically understood as singular. There are, however, cases where ilay is compatible with plural reference (B. Ralalaoherivony, p.c.), such as in (6).

- (6)

- Nalevina

- buried

- avy hatrany

- immediately

- ilay

- det

- omby

- cow

- roa

- two

- maty

- dead

- ‘The two dead cows were immediately buried.’

Singular and plural distinctions are overtly marked only on demonstratives.3

We consider ny and ilay as determiner-like in part because they are in complementary distribution, (7a, b), and they do not have intransitive, pronominal uses, (7c). As we will see below, this distribution contrasts with the demonstratives.

- (7)

- a.

- Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ilay/ny

- det

- fiara

- car

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- ‘I want to buy that/the car.’

- b.

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- {ny

- det

- ilay,

- det

- ilay

- det

- ny}

- det

- fiara

- car

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to buy the/that car.’)

- c.

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ilay/ny

- det

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to buy that/the.’)

2.2 Demonstratives

The demonstrative system in Malagasy is very rich, encoding not only distance (proximal, distal, and neutral) and number (singular and plural), but also visibility (visible and non-visible) and “boundedness”. Bounded and unbounded indicate whether the space that the object occupies is seen as enclosed or open. There are also demonstratives for generics. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, adapted from Rajaona (1972: 633) and Imai (2003), some distinctions are leveled for certain forms (e.g. ireto is the plural, proximal demonstrative, but it is unmarked for bounded versus unbounded).

Visible demonstratives.

| Proximal | Distal | Neutral (but not near speaker) | |||||

| bounded | unbounded | close | very far | bounded | unbounded | ||

| singular | ito | ity | itsy | iroa | iry | io | iny |

| plural | ireto | iretsy | ireroa | irery | ireo | ireny | |

| generic | itony | itsony | irony | ||||

Non-visible demonstratives.

| Proximal | Distal | Neutral (but not near speaker) | |||||

| bounded | unbounded | close | very far | bounded | unbounded | ||

| sing/pl | izato | izaty | izatsy | izaroa | izary | izao, izay | izany |

| generic | izatony | izatsony | izarony | ||||

The reader will note clear morphological regularities (see Rajaona 1972: 623–632 for some discussion), but we set those aside here, focusing instead on the external syntax of demonstratives.

As noted above, the framing pattern for demonstratives is required in Malagasy, with some exceptions to be discussed in 2.3. A second crucial fact about the framing demonstratives is that they must be identical. The initial and final demonstratives must be exactly the same, (8); we have not encountered any text or elicited examples where the demonstratives do not match.4

- (8)

- a.

- io

- dem1

- boky

- book

- io/*ity/*iny/*itsy/*iroa/*iry/etc.

- dem2

- ‘this book’

- b.

- ireo

- dem1

- boky

- book

- ireo/*ireto/*iretsy/*irery/*ireny/etc.

- dem2

- ‘those books’

Framing demonstratives are strictly initial and final in the nominal. They frame any dependents that occur in the nominal. We illustrate non-exhaustive possibilities in (9). (9a) shows framing of a noun, adjective, and possessor; (9b) shows framing of a noun, numeral, and PP modifier; and (9c) shows framing of a noun, quantifier, and relative clause. In no cases can either demonstrative appear internal to the nominal instead of in the peripheral positions.

- (9)

- a.

- possessor & adjective

- io

- dem

- akoho

- chicken

- (*io)

- dem

- fotsin-

- white

- (*io)

- dem

- -dRasoa

- Rasoa

- io

- dem

- ‘this white chicken of Rasoa’s’

- b.

- number & PP modifier

- ireo

- dem

- boky

- book

- (*ireo)

- dem

- telo

- three

- (*ireo)

- dem

- momba

- about

- ny

- det

- planety

- planet

- ireo

- dem

- ‘those three books about the planets

- c.

- quantifier & relative clause

- ireo

- dem

- fitsipika

- rule

- (*ireo)

- dem

- vitsivitsy

- few

- (*ireo)

- dem

- izay

- rel

- tena

- really

- ilaina

- needed

- ireo

- dem

- ‘those few rules which are very needed’

We have encountered two exceptions to this pattern, two elements that can exceptionally appear after the final demonstrative. The first is exceptive phrases that modify a DP and form a constituent with it, which must occur after the final demonstrative, (10). The second case is non-restrictive relative clauses, which may optionally appear after the final demonstrative, (11).5 We assume that, in both instances, the modifier must or can adjoin to the right of the nominal, which will place it strictly final under most any structural analysis.

- (10)

- ireo

- dem

- vahiny

- guest

- rehetra

- all

- ireo

- dem

- afa-tsy

- except

- Rasoa

- Rasoa

- (*ireo)

- all

- ‘all the guests except Rasoa’

- (11)

- a.

- ity

- dem

- varavarana

- door

- (ity)

- dem

- izay

- rel

- nolokoina

- painted

- mena

- red

- (ity)

- dem

- ‘this door, which is painted red’

- b.

- Nahatsiaro

- remember

- menatra

- shame

- i Koto,

- Koto

- raha

- when

- nifanena

- meet

- tamin’

- with

- ireny

- dem

- mpianatra

- student

- namany

- friend.3sg.gen

- ireny

- dem

- izay

- rel

- efa

- already

- tsy

- neg

- azony

- can.3sg.gen

- nandosirana

- flee

- intsony

- anymore

- ‘Koto felt embarrassed when he came across these students, his friends, who he could no longer avoid.’ (Fugier 1999: 190)

We have nothing more to say about these cases as they do not appear to have any implications for the correct analysis of the framing pattern.

2.3 Non-framing uses of demonstratives

The demonstratives have three non-framing uses which we discuss here. First, the most prominent non-framing use is what we will call the pronominal function, or pronominal demonstratives. The demonstrative appears alone, unmodified, and cannot be doubled, (12).6 All demonstratives can appear in this use as far as we are aware, and they can appear in any position where DPs can appear (e.g. subject, object, object of a preposition).

- (12)

- a.

- Te

- want

- hihinana

- eat

- an’

- acc

- ity/io/itony/iretsy/irery/etc.

- dem

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- ‘I want to eat this/that/these/those.’

- b.

- *Te

- want

- hihinana

- eat

- an’

- acc

- ity

- dem

- ity

- dem

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to eat this.’)

Cross-linguistically, this is a common use of demonstratives (Alexiadou et al. 2007: 95); nevertheless, it is perhaps surprising that pronominal demonstratives are never doubled, where they might be framing a null noun. Accounting for this pattern will be important in the analyses to follow.

Second, a lone final DEM2 demonstrative is sometimes possible if the initial determiner is ilay, (13). The interpretation of such nominals combines the anaphoric meaning of ilay with the parameters of number, visibility, distance from the speaker, and boundedness of the demonstrative that is used. Rajaona (1972: 686) indicates that ilay is only compatible with [+visible] demonstratives but not those that are [–visible], except for izay. We have not systematically investigated which demonstratives are possible in this context.

- (13)

- a.

- Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ilay

- DET

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- DEM

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- ‘I want to buy that white car (which we previously discussed and is near the speaker).’

- b.

- Nanamboatra

- fixed

- lakana

- boat

- ilay

- DEM

- lehilahy

- man

- iny

- DEM

- ‘That man (that we already talked about but cannot see) fixed the boat.’

- c.

- Ilay

- DET

- fiara

- car

- frantsay

- French

- io

- DEM

- dia

- top

- lafo

- expensive

- be

- very

- ‘This French car is very expensive.’

The presence of ilay precludes the framing pattern. Only the final instance of the demonstrative is possible:

- (14)

- a.

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- (*ity)

- DEM

- ilay

- DET

- (*ity)

- DEM

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- DEM

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- ‘I want to buy that white car.’

Ilay can cooccur with DEM2 without any intervening nominal material:

- (15)

- a.

- Tsy

- neg

- matahotra

- fear

- haizina

- darkness

- mihitsy

- at.all

- ilay

- DET

- iry

- DEM

- ‘That person is not afraid of the dark at all.’

- b.

- Ilay

- DET

- io

- DEM

- dia

- top

- lafo

- expensive

- be

- very

- ‘This one is very expensive.’

Turning to ny ‘det’, a demonstrative can never cooccur with ny, with or without nominal material, (16).

- (16)

- a.

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ny

- DET

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- DEM

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to buy that white car.’)

- b.

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- {ny

- DET

- ity,

- DEM

- ity

- DEM

- ny}

- DET

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- DEM

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to buy that white car.’)

- c.

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- {ny

- DET

- ity,

- DEM

- ity

- DEM

- ny}

- DET

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to buy that one.’)

Malagasy has a null determiner, which is possible in object position, (17a); however, DEM2 is not possible here either, (17b).7

- (17)

- a.

- Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ø

- DET

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- ‘I want to buy a white car.’

- b.

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ø

- DET

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- DEM

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to buy that white car.’)

Finally, we have determined that some initial DEM1 demonstratives can appear alone, without DEM2. This option is both lexically and idiolectally restricted in that most demonstratives are not possible in this pattern and the ones that are possible vary among speakers. All our speakers accept the proximal and neutral plural demonstratives ireto and ireo in this pattern, (18a). Some speakers accept the corresponding singular demonstratives, ity and io, as well, (18b). No speakers that we have consulted accept any of the other demonstrative as a lone DEM1, (18c).8

- (18)

- a.

- ireto/ireo

- dem1.pl.near/neutral

- boky

- book

- ‘these books’

- b.

- %ity/io

- dem1.sg.near/neutral

- boky

- book

- ‘this book’

- c.

- *iny/itsy/iroa/iry/ireny/iretsy/ireroa/irery/etc.

- dem1

- boky

- book

- (‘that/those book(s)’)

We analyze these cases as a reanalysis of certain demonstratives as determiners (Rajaona 1972). This reanalysis is subject to inter-speaker variation, and we set it aside for the purposes of this paper.

2.4 Against DEM2 as a reinforcer

Before continuing to our analysis, we would like to dismiss treating DEM2 as a demonstrative reinforcer. There is a rich literature on demonstrative-reinforcer constructions in Germanic and Romance languages, exemplified in (19) (Brugè 1996; Bernstein 1997; Leu 2007; 2008; Roehrs 2010).

- (19)

- a.

- English

- this here house

- b.

- French

- ce

- dem

- livre

- book

- rouge-ci

- red-here

- ‘this red book’

- c.

- Spanish (Brugè 1996)

- el

- the

- libro

- book

- viejo

- old

- este

- dem

- de

- of

- aquí

- here

- ‘this old book’

Despite superficial similarity between Malagasy framing demonstratives and demonstrative reinforcers, we believe that the two are distinct phenomena. There are notable differences between framing demonstratives and reinforcers. First, demonstrative doubling in Malagasy always involves identical demonstratives, while in the reinforcer construction, the demonstrative and reinforcer are always morphologically distinct vocabulary items. Second, reinforcers are optional, while in Standard Malagasy doubling is typically required.9 Third, reinforcers are dependent upon the demonstrative and never appear without it, but we have seen that DEM2 can be licensed by the non-demonstrative determiner ilay. Fourth, demonstrative pronouns themselves can be reinforced, as illustrated in the French example in (20); however, we have seen that pronominal demonstrative doubling is impossible in Malagasy.

- (20)

- French (Bernstein 1997: 91)

- celui-ci

- this.one-here

- ‘this here’

Fifth, reinforcers are typically locative elements (e.g. here, there) but DEM2 in the doubling construction must be a demonstrative, not a locative.10 Finally, the position of reinforcers with respect to the head noun varies across languages, as can be seen in the examples in (19), but even in languages where the reinforcer appears to be final (French and Spanish), it precedes possessors and PP modifiers, as in the French examples in (21). The equivalent of (21a) is ungrammatical in Malagasy, as DEM2 must be strictly final (see Section 2.2).

- (21)

- French (Brugè 2002: 38)

- a.

- ce

- dem

- livre-ci

- book-here

- de

- of

- Jean

- Jean

- ‘this here book of Jean’s’

- b.

- *ce

- dem

- livre

- book

- de

- of

- Jean

- Jean

- ci

- here

Thus, notwithstanding some points of resemblance, framing demonstratives and reinforcers are syntactically distinct and we do not unify the two.

2.5 Summary

In Section 4, we will be concerned with accounting for the empirical generalizations introduced above and summarized in (22), which we take to be the core facts regarding Malagasy framing demonstratives.

- (22)

- a.

- DEM1 must be strictly initial and DEM2 must be strictly final

- b.

- DEM1 and DEM2 must be identical

- c.

- All demonstratives can be used pronominally but cannot be doubled in this use

- d.

- Lone DEM2 is compatible with ilay but not ny or a null determiner

Before turning to possible analyses of these patterns, we first lay out a proposal for the structure of the Malagasy DP.

3 Malagasy nominal structure

There is very little work on the structure of Malagasy nominals. We are aware only of Ntelitheos (2005; 2006; 2010; 2012) on nominalizations, and Zribi-Hertz & Mbolatianavalona (1999) and Paul & Travis (2022) on Malagasy personal pronouns. Consequently, we need to develop a preliminary picture of Malagasy nominal syntax before continuing.

As repeated in (23), Malagasy nominals are head-initial, with dependents arraying after the head noun in an order that is roughly inverse with respect to English.

- (23)

- Malagasy DP word order (modified from Ntelitheos 2012: 63)

- DEM1/det

- N

- adj

- poss

- num

- quant

- rc

- DEM2

This inverse ordering with respect to English is also seen in the domain of adjectives, although there is considerable freedom and speaker variation that we have not systematically explored. To first approximation, we take the unmarked order of adjectives to be (24) and illustrated by the data in (25).

- (24)

- Malagasy adjective word order

- N≻nationality ≻color ≻shape ≻size ≻quality

- (25)

- a.

- fiara

- car

- italiana

- Italian

- mahafinaritra

- nice

- ‘a nice Italian car’ nationality ≻quality

- b.

- fioze

- gun

- amerikanina

- American

- lehibe

- big

- ‘a big American gun’ nationality ≻size

- c.

- voankazo

- fruit

- maintso

- green

- mamy

- sweet

- ‘a sweet green fruit’ color ≻quality

- d.

- latabatra

- table

- fotsy

- white

- boribory

- round

- ‘a round white table’ color ≻shape

- e.

- baolina

- ball

- boribory

- round

- ngeza

- big

- ‘a big round ball’ shape ≻size

In what follows we propose a structure for Malagasy nominals that has three components: i) a spine of functional projections extending from the lexical NP at the base to DP at the top (Section 3.1), ii) a Roll Up derivation in a subdomain of the nominal that obtains the inverse ordering of modifiers seen above (Section 3.2), and iii) a Nominal Fronting movement that derives the positioning of the final demonstrative (Section 3.3). We develop each of these in turn. Section 3.4 shows that there are substantive parallels between our proposed nominal structure and the structure of Malagasy clauses.

3.1 The nominal spine

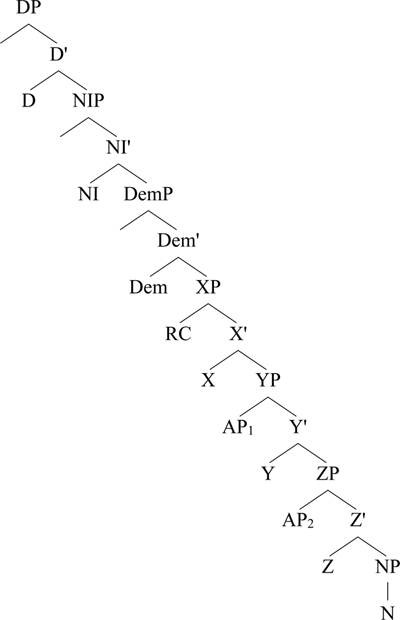

We propose the basic structure for Malagasy nominals in (26).

- (26)

The nominal is built on an NP, which will contain the lexical head. Above this NP is a series of functional projections which will introduce the various modifiers: relative clauses, quantifiers, numerals, a possessor, and adjectives. Because the focus of the paper is on the analysis of demonstratives, we will not develop a specific proposal for most of these dependents. We will take adjectives (AP) and relative clauses (RC) as representative in order to illustrate our proposal. We assume that they are introduced in specifiers of functional projections above NP (Cinque 2010; 2020), labeled XP, YP, and ZP, above. The topmost projection, XP, is roughly equivalent to PredP/vP in the clausal domain, containing the head noun, its arguments, if any, and diverse modifiers.

Above XP we posit a Dem(onstrative)P(hrase) where demonstratives will originate (Bernstein 1997; Giusti 1997; 2002; Pangiotidis 2000; Brugè 2002; Shlonsky 2004; Roehrs 2010; Cinque 2010; 2020; and others). We will have more to say about the syntax of demonstratives, DemP, and its position after spelling out the remainder of the nominal spine. DemP is dominated by a nominal inflectional projection, labeled NIP, whose more precise identity, if it has one, we will not attempt to determine. While Zribi-Hertz & Mbolatianavalona (1999) identify this projection as Num(ber)P, we will not give it that specific label as we believe it may contain more general inflectional information, beyond number.11 We consider NIP to be equivalent to IP in the clausal domain. In some languages, for example those without tense morphology, IP is a more suitable label for the main inflectional head in a clause compared to T(ense)P that has become standard. Finally, NIP is dominated by D(eterminer)P, following much work within the DP Hypothesis (Abney 1987, inter alia), which we adopt. We view the projections above XP (DemP through DP) as an inflectional domain, roughly equivalent to the projections between vP and CP in the clausal domain.

Returning to the syntax of demonstratives, there are at least two dominant families of analysis in the literature. In the determiner analysis, demonstratives are a kind of determiner. Within the DP Hypothesis, they are base-generated in D, at the top of the nominal spine. The determiner analysis is driven by languages such as English in which determiners and demonstratives are in complementary distribution. Placing demonstratives in the same structural position as determiners straightforwardly accounts for this fact (Jackendoff 1977). On the other hand, the analysis faces several empirical and conceptual difficulties. First, there are languages, such as Greek, in which the two are not in complementary distribution, (27).

- (27)

- Greek (Alexiadou et al. 2007: 76)

- afti

- this

- i

- the

- ghata

- cat

- ‘this cat’

Second, the demonstrative is a universal category while determiner is not. There are many languages that lack determiners, most famously the Slavic languages, but none that lack demonstratives (Diessel 1999; Alexiadou et al. 2007: 95). Assigning them to the same position does not yield an immediate explanation for why such an asymmetry might exist. Third, demonstratives can be used intransitively (i.e., pronominally) while determiners generally cannot be (Alexiadou et al. 2007: 95). Finally, the interpretation of demonstratives is different from determiners (Diessel 1999: 35–55; Alexiadou et al. 2007: 98–104).

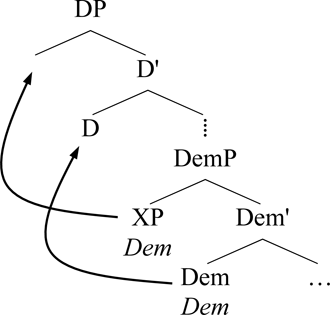

Responding to these differences, researchers have defended some version of the DemP analysis we adopted above. Demonstratives are base-generated in a lower position in the nominal spine. Cartographic principles or language-specific facts determine the location of DemP. Demonstratives may be phrasal and occupy spec,DemP and/or be heads in Dem. Both options have been proposed in the literature. Either of these elements may ultimately move to a higher position, such as spec,DP or D. Thus, there is a rather large family of DemP-based analyses, schematized in (28), depending upon the base and surface position(s) of the demonstrative and the movements posited within the nominal. We will develop two such analyses for Malagasy below. DP

- (28)

With this much in place, we develop a derivation for Malagasy nominals.

3.2 Roll Up

We assume that the inverse ordering of adjectives and relative clauses is achieved through Roll Up in the XP domain in (26). Assuming a universal base-generated order of adjectives as in English (quality ≻ size ≻ shape ≻ color ≻ nationality), Roll Up will yield the inverse ordering of adjectives, (24). Following Cinque (2005; 2010), relative clauses may be generated in leftward specifiers above the adjectives. Continued Roll Up will place the relative clause on the right.

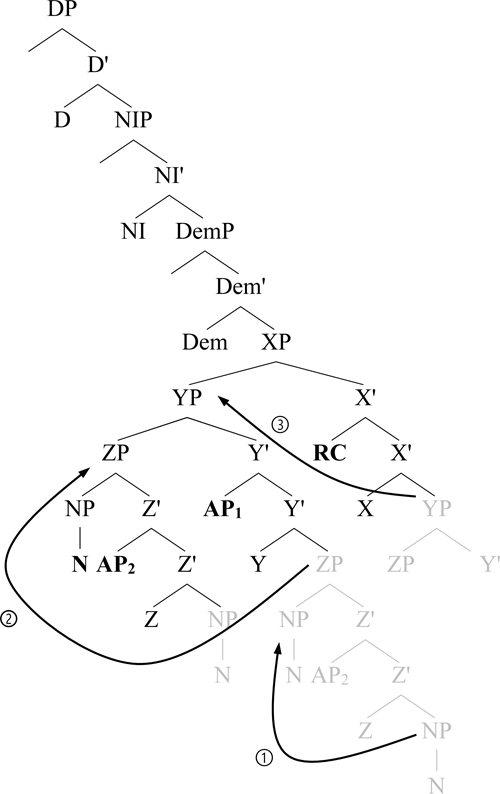

A Roll Up, or Snowball, derivation consists in moving a constituent C1 to a position above a modifier M1 and then moving a constituent C2 that properly contains C1 and M1 to a position above another modifier M2. The movement carries along C1 and M1 in an inverse order. As each subsequent, larger constituent moves, it picks up a modifier on its right. We illustrate for an example with two adjectives, AP1 and AP2, and a RC. The base-generated order seen in (26) is RC ≻ AP1 ≻ AP2 ≻ N. The word order resulting from Roll Up is the inverse N ≻ AP2 ≻ AP1 ≻ RC, (29).

The derivation has an underlying structure as in (26) above. The first movement, labeled ①, moves NP to the (outer) specifier of ZP, above AP2. This achieves the ordering N ≻ AP2. This constituent ZP then undergoes movement, labeled ②, to the (outer) specifier of YP, placing ZP to the left of AP1 and deriving the order N ≻ AP2 ≻ AP1. Finally, YP moves to the (outer) specifier of XP, above RC. This movement is labeled ③. This yields the desired inverse order N ≻ AP2 ≻ AP1 ≻ RC, seen in the bold-faced elements.

- (29)

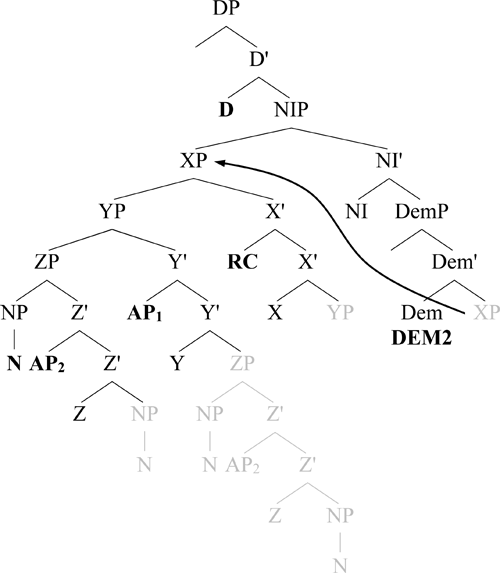

3.3 Nominal Fronting

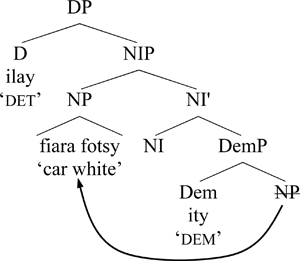

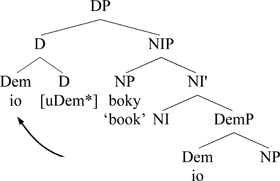

We now turn to the framing word order. We assume that the determiner-like elements ny and ilay reside in D and that demonstratives are in Dem. This requires that all other nominal material move to a position between D and Dem. Consequently, we posit Nominal Fronting, which moves the Rolled Up XP constituent to a position between D and DemP, which we identified above as spec,NIP (see Zribi-Hertz & Mbolatianavalona 1999; Ntelitheos 2012). Continuing the schematic derivation from (29), XP moves to spec,NIP, yielding the structure in (30).

- (30)

The derivation above could correspond to the following nominal:

- (31)

- ilay

- d

- det

- voankazo

- N

- fruit

- maitso

- AP2

- green

- mamy

- AP1

- sweet

- izay

- RC

- rel

- nohaniko

- eat.1sg.gen

- ity

- dem2

- dem

- ‘that sweet green fruit that I ate’

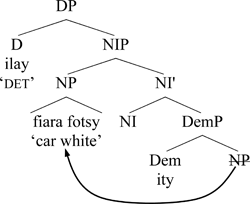

Moving forward, the details of the Roll Up structure will not be relevant to the analysis of framing demonstratives, and we will replace XP with NP, regardless of its structural make up, even when it contains modifiers. We therefore remain agnostic about the category label, but assume it is the highest projection in the nominal lexical domain. Thus, for the demonstrative-modified nominal in (32), we use the representation in (33).

- (32)

- ilay

- det

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- dem

- ‘this white car’

- (33)

We will return to the motivation for Nominal Fronting in Section 4, where we discuss the derivation of framing demonstrative examples. Before turning to such examples however, we situate our proposal in the larger context of Malagasy phrase structure.

3.4 Comparison to Malagasy clause structure

The derivation of Malagasy nominals involves the following pieces:

- (34)

- a.

- a nominal spine consisting minimally of DP > NIP > (DemP) > NP

- b.

- Roll Up inside NP

- c.

- Nominal Fronting: movement of NP to spec,NIP

This section briefly shows that our derivation for Malagasy nominals has parallels to the structure proposed for clauses, which typically posit both a Roll Up process low in the structure and fronting of the Rolled Up constituent to a higher, left peripheral specifier.

A Roll Up derivation in the clausal domain has been proposed for two independent purposes in Malagasy. First, Pearson (2000) uses Roll Up to achieve an inverse ordering of double objects compared to English, (35).

- (35)

- Nanolotra

- offered

- ny

- det

- dite

- tea

- ny

- det

- vahiny

- guest

- ny

- det

- zazavavy

- girl

- ‘The girl offered the guests the tea.’ (Pearson 2000: 329)

Second, Rackowski (1998), Rackowski & Travis (2000), and Pearson (2000) show that the order of preverbal adverbial elements in Malagasy patterns with English and Cinque’s (1999) adverbial hierarchy; however, postverbal adverbials appear in the mirror order. The latter is again achieved via Roll Up. See those references for data. Thus, there is a parallel in the clausal domain for this movement. It takes place in the lower part of the clause, typically identified as vP/PredP. What we have called XP is the nominal equivalent of this phrase.

Nominal Fronting is roughly parallel to Predicate Fronting in the clausal domain. Predicate Fronting derives predicate-initial word order (VOS) from an underlying SVO ordering (see Massam & Smallwood 1997; Rackowski & Travis 2000; Pearson 2001; 2018; Aldridge 2004; Cole & Hermon 2008; Travis & Massam 2021; among others for discussion and motivation). There is a significant amount of literature that derives Malagasy’s predicate-initial word order from an operation that moves the predicate (the verb plus all complements) to a high position in the clause. In other words, a sentence such as (36), has the structure schematized in (37), although the precise details of the category of the moved element and the position it moves to vary among authors.

- (36)

- Nanasa

- washed

- lamba

- clothes

- Rabe

- Rabe

- ‘Rabe washed clothes.’

- (37)

- [XP

- [PredP

- nanasa

- washed

- lamba ]i

- clothes

- [TP

- Rabe [ ti ]] ]

- Rabe

We believe that the parallels between our nominal structure and that typically posited for clauses provide indirect evidence for our proposal.

Having discussed Roll Up and Nominal Fronting within DP, we turn to the framing demonstratives. Section 4 presents two different approaches to syntactic doubling in the literature—single versus dual representation—and applies them to the Malagasy case. Section 5 then argues for the single representation analysis.

4 Two approaches to demonstrative doubling

Copy constructions are morphosyntactic phenomena in which two similar or identical syntactic elements, X1 and X2, identified with a single interpretation are both pronounced. There is a wide range of copy constructions and selected examples are given below.

- (38)

- Copy Raising

- He seems like he is in trouble.

- (39)

- Copy Control

- San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec (Lee 2003: 102)

- R-cààa’z

- hab-want

- Gye’eihlly

- Mike

- g-auh

- irr-eat

- Gye’eihlly

- Mike

- bxaady

- grasshopper

- ‘Mike wants to eat grasshopper.’

- (40)

- Verb Doubling

- Vata (Koopman 1984)

- Lī

- eat

- à

- 1pl

- lī-dā

- eat-pst

- zué

- yesterday

- sa̍ká

- rice

- ‘We ate rice yesterday.’

- (41)

- Wh-Copying

- Afrikaans (Du Plessis 1977: 725)

- Waarvoor

- wherefore

- dink

- think

- julle

- you

- waarvoor

- wherefore

- werk

- work

- ons?

- we

- ‘What do you think we are working for?’

When faced with a copy construction, syntacticians typically resort to one of two approaches, what we will call the single representation approach and the dual representation approach.

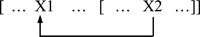

In the single representation approach, one representation of X is generated in the structure. X moves to a new position or positions and two (or more) pieces of the movement chain(s) created are pronounced.12

- (42)

With the replacement of trace theory by the Copy Theory of Movement (CTM) (Chomsky 1993), in which movement leaves behind identical copies of the moving element rather than null traces, such constructions have received greater attention. They provide support for the CTM because they potentially show the pronunciation of multiple chain links/copies. Such analyses are typically called Multiple Copy Spell Out (MCSO). Assuming the CTM, some principled mechanism to determine when multiple copies can be pronounced is required, as the dominant pattern in movement constructions is to pronounce only the highest copy; however, little else is necessary. There are several theories for determining which copies are pronounced in a complex chain, some of which are capable of handling MCSO (see Pesetsky 1998; Fox & Nissenbaum 1999; Bobaljik 2002; Nunes 2004; Kandybowicz 2008; and others for copy pronunciation strategies). Single representation analyses of the above copy constructions dominate the literature and include Copy Raising (Rogers 1974; Joseph 1976; McCloskey & Sells 1988; Déprez 1992; Moore 1998; Ura 1998), Copy Control (Lee 2003; Boeckx et al. 2007; Haddad 2009), Verb (Phrase) Doubling (Koopman 1984; Abels 2001; Landau 2006; Cheng 2007; Martins 2007; Bleaman 2022), and Wh-Copying (Du Plessis 1977; McDaniel 1989; Fanselow & Mahajan 2000; Felser 2004; Bruening 2006).

An alternative analysis of copy constructions is what we call the dual representation approach. In this analysis, the two similar elements are base-generated separately. They are linked by an interpretive mechanism such as coindexation or a syntactic mechanism such as feature matching.

- (43)

- [

- …

- X1i

- …

- [

- …

- X2i

- …

- ]]

Dual representation analyses exist for some of the above constructions: Copy Raising (Potsdam & Runner 2001; Landau 2011) and Verb (Phrase) Doubling (Cable 2004; Antonenko 2018; Muñoz-Pérez & Verdecchia 2022). Two doubling constructions that are widely analyzed with dual representation are Hanging Topic Left Dislocation (Aissen 1992; Hirschbühler 1997; de Cat 2007; Sturgeon 2008; Polinsky & Potsdam 2014), and Prolepsis (Davies 2005; Salzmann 2006). Dual representation constructions typically terminate in a pronominal copy rather than identical copy.

In sections 4.1 and 4.2, we develop single and dual representation analyses for the Malagasy framing demonstrative construction. Looking ahead, Section 5 provides evidence in support of the single representation analysis. We argue that the two demonstratives are realizations of one base-generated element.

4.1 Single representation analysis

This section presents a single representation analysis of Malagasy framing demonstratives. We first lay out our proposed derivation and then present the machinery, from Saab (2017), that results in demonstrative doubling.

As a reminder, (44) contains our assumptions about Malagasy nominal structure.

- (44)

- a.

- a nominal spine consisting minimally of DP > NIP > (DemP) > NP

- b.

- Roll Up inside NP

- b.

- Nominal Fronting: movement of NP to spec,NIP

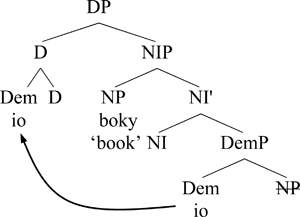

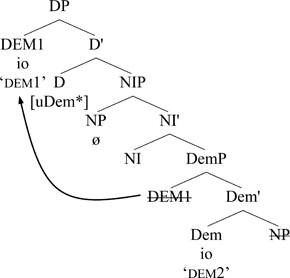

To the framing demonstrative example in (45), we assign the structure in (46). In addition to Nominal Fronting of NP to spec,NIP, there is head movement of Dem to D.

- (45)

- io

- dem1

- boky

- book

- io

- dem2

- ‘this book’

- (46)

We follow Harizanov & Gribanova (2019), which argues that there are two types of head movement: syntactic head movement and post-syntactic morphological amalgamation. The former is a syntactic operation with syntactic properties and subject to syntactic restrictions. Our Dem-to-D is clearly of this type and has a number of its characteristics (Harizanov & Gribanova 2019): i) it affects word order, ii) it is not morphologically driven, iii) it does not result in word formation, iv) it is not governed by the Head Movement Constraint (HMC, Travis 1984) and can skip other heads, and v) it is driven by whatever is assumed to drive syntactic movement (i.e. Agree, feature checking, or a generalized EPP). Of particular note is the claim in iv) that syntactic head movement does not obey the HMC, potentially resulting in what has been called long head movement. Our Dem-to-D is an instance of long head movement. Much recent work (Lema & Rivero 1990; Rivero 1994; Matushansky 2006; Roberts, 2010; Harizanov & Gribanova 2019; Arregi & Pietraszko 2021; others) has argued for the empirical necessity and theoretical viability of long head movement and we follow these works and others in assuming that it is allowed.13

We drive Dem-to-D movement with a strong Dem feature, [uDem*], on D. If D bears this feature, Dem will move to D. If there is no Dem in the derivation with this D head, it will crash. There are other D heads in Malagasy which do not bear this feature and result in D being spelled out as ilay or ny according to the vocabulary insertion rules in (47). This correctly derives the low position of the demonstrative and the lack of framing in (48), which has the structure we previously assigned in (49).

- (47)

- a.

- b.

- c.

- ø

- ilay

- ny

- ↔

- ↔

- ↔

- [uDem*, referential]

- [anaphoric, referential]

- elsewhere14

- (48)

- (*ity)

- dem

- ilay

- det

- (*ity)

- dem

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- dem

- ‘that white car’

- (49)

As previously discussed, Nominal Fronting is akin to Predicate Fronting in the clausal domain. Massam & Smallwood (1997), Pearson (2001), Massam & Travis (2021), and others invoke an EPP feature on a functional head (e.g. T) that drives Predicate Fronting, and we will simply stipulate that Nominal Fronting is driven by an EPP feature on NI, requiring that its specifier be filled.

We now turn to the theoretical machinery that results in double pronunciation of the demonstrative in (46). Saab’s (2017) I-assignment mechanism was developed to account for verb doubling in the Predicate Cleft (PC) construction. The PC is a widely discussed doubling construction in the clausal domain. PCs consist of a fronted verb or verb phrase resumed by a lower copy or morphologically similar copy of the verb. PCs have received a great deal of attention in the literature since Koopman’s (1984) work on Vata. Examples from typologically-diverse languages are given in (50).

- (50)

- a.

- Russian (Abels 2001: (1))

- Čitat’

- read.inf

- (-to)

- to

- Ivan

- Ivan

- eë

- it.fem.acc

- čitaet

- reads

- (no

- but

- ničego

- nothing

- ne

- not

- ponimaet)

- understands

- ‘Ivan does read it (but he doesn’t understand a thing).’

- b.

- Yiddish (Bleaman 2022: (2))

- Red-n

- speak-inf

- mame-loshn

- mama-language

- red

- speak.1sg

- ikh

- I

- ‘As for speaking Yiddish, I speak it.’

- c.

- Hebrew (Landau 2006: (1))

- Lirkod

- dance.inf

- Gil

- Gil

- lo

- not

- yirkod

- dance.fut

- ba-xayim

- in.the-life

- ‘As for dancing, Gil will never dance.’

- d.

- Nupe (Kandybowicz 2008: 101, (28b))

- Bi-ba

- cut~cut

- Musa

- Musa

- ba

- cut

- nakàn

- meat

- o

- foc

- ‘It was cutting that Musa did to the meat.’

- e.

- Vata (Koopman 1984: 38, (50))

- lī

- eat

- O̍

- s/he

- dā

- perf.aux

- sa̍ká

- rice

- lī

- eat

- ‘She has eaten rice.’

Saab (2017), building on Saab (2008), analyzes the PC in Romance and argues that multiple copies of the verb arise due to the conditions that determine copy pronunciation. He proposes the notion of I-Assignment to achieve this. I-Assignment assigns a feature [I] to certain constituents that then blocks Vocabulary Insertion to that constituent at PF. There are two kinds of I-Assignment, phrasal and head. Phrasal I-Assignment occurs in the syntax under familiar conditions, namely, c-command. Head, or Morphological, I-Assignment occurs at PF.

Phrasal I-Assignment is defined as follows, where for Saab’s purposes, chain links count as identical.

- (51)

- Phrasal I-Assignment in the syntax (simplified version) (Saab 2017: (54))

- A copy C is I-Assigned if and only if there is an antecedent copy AC for C, such that

- i.

- AC and C are identical, and

- ii.

- AC c-commands C

I-Assignment to heads occurs at PF under morphological considerations:

- (52)

- Morphological I-Assignment (Head Ellipsis) (Saab 2017: (75))

- Given a Morphosyntactic Word (MWd) Y0, assign a [I] feature to Y0 if and only if there is a node X0 identical to Y0 contained in an MWd adjacent or immediately local to Y0 (where the notion of containment is reflexive).

Following Embick & Noyer (2001: 574), Y0 is a Morphological Word (MWd) if and only if Y0 is the highest segment of an X0 not contained in another X0. Morphological I-Assignment has the effect of marking for deletion any MWd that is either i) linearly adjacent to an identical head or ii) structurally immediately local to an identical head, where immediate locality is the relation between a head and the head of its complement.

Consider how I-Assignment, in particular Morphological I-Assignment, leads to demonstrative doubling in the structure repeated below. The relevant MWd Y0 which could be targeted for I-assignment is Dem in its base position. Given (52), [I] would be assigned to this lower Dem if and only if it is adjacent or immediately local to an MWd containing another instance of Dem, the X0. Neither of these conditions is met. The two Dems are not adjacent because the NP boky intervenes. The lower Dem is also not local to D because D does not select DemP as its complement: NIP intervenes. As a result, the base position of Dem is not assigned an [I] feature and both instances of Dem are pronounced at PF.

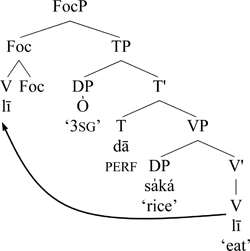

- (53)

Constituent labels aside, this is the analysis that Saab (2017: (114)) assigns to the Vata PC in (50e). V-to-Foc is fully parallel to our D-to-Dem and results in verb doubling.

- (54)

The theory makes the prediction that long head movement will normally lead to head doubling. Whether this is a correct prediction will need to be tested in other domains where long head movement is justified. Space prevents us from exploring it here.1516

4.2 Dual representation analysis

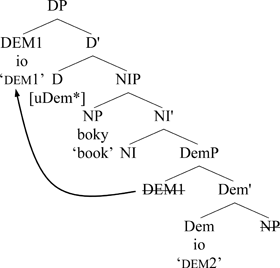

This section develops an alternative, dual representation analysis. Section 5 will show that it is not as successful as our single representation analysis in Section 4.1. A dual representation analysis of framing demonstratives necessarily base-generates two instances of the demonstrative. For the sake of parity, we will formulate a dual representation analysis that is similar to our single representation analysis above. In particular, i) we continue to adopt the DemP analysis of demonstratives, with demonstratives being base-generated within DemP, and ii) we posit movement of Dem into DP.

The dual representation structure for framing demonstratives is given in (55). DEM1 is phrasal and occupies spec,DemP, while DEM2 is the head of DemP. DEM1 moves to spec,DP to check the [uDem*] feature of D. DEM1 moves rather than the Dem head DEM2 because it is closer to D. The lower copy of DEM1 is I-assigned according to the Phrasal I-Assignment rule in (51) and is not pronounced. There is Roll Up within NP and Nominal Fronting as above.

- (55)

This structure gives rise to the correct word order, where DEM1 and DEM2 are initial and final, respectively.17

5 Arguments for single representation

While both the single representation (SR) and dual representation (DR) analyses account for the basic framing word order, we argue here that DR does not cover the full range of empirical facts. We repeat the core patterns in (56), and show that DR is less successful in accounting for (56b-d). We have already seen that both analyses derive the framing word order, (56a).

- (56)

- a.

- DEM1 must be strictly initial and DEM2 must be strictly final

- b.

- DEM1 and DEM2 must be identical

- c.

- all demonstratives can be used pronominally but cannot be doubled

- d.

- lone DEM2 is compatible with ilay but not ny or a null determiner

The identity between DEM1 and DEM2, (56b), falls out directly from SR because there is only one representation of the demonstrative. When it moves, it cannot change form; as a result DEM1 and DEM2 will be identical. Under DR, however, the identity is not automatic. One might try to enforce the identity through feature checking: DEM1 and DEM2 have morphosyntactic features that encode their semantics. Given Tables 1 and 2, we assume for concreteness that these features would be [±visible], [±bounded], [#distance], and [±singular]. Identity could be enforced with an Agree (or Spec-Head) relation between the features of DEM1 and the features of DEM2. Terenghi (2019), however, argues that features unique to demonstratives—in the case of Malagasy, [±visible], [±bounded], [#distance]—are not active in the syntax and therefore cannot participate in Agree. On that assumption, feature checking cannot be used to achieve identity. Moreover, even assuming that such features exist and can participate in Agree, DR arguably would allow cases of non-matching. Depending upon our feature analysis of demonstratives in Table 1 and 2, we might expect mismatched demonstratives if the feature specifications are distinct but compatible. For example, there are demonstratives that are not specified for distance (io, ireo, iny, ireny). Such demonstratives should be compatible with those that have the same [±visible], [±bounded] features but are unspecified for distance, unless “neutral” distance is itself a specification and not an underspecification. This constitutes an argument against DR if demonstrative matching must be done in the syntax.

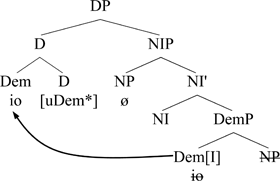

The absence of doubling with the pronominal use, (56c), is accounted for by SR. We follow much of the literature on pronouns (e.g. Postal 1969; Cardinaletti 1994; Ritter 1995; Koopman 1999; Panagiotidis 2002; and references therein) in assuming that pronominal demonstratives involve an abstract nominal. They are not intransitive heads, contra Abney (1987). The derivation proceeds as above but with a null NP, (57). Saab’s Morphological I-Assignment rule, (52), will result in [I] being assigned to the Dem head of DemP because the two copies of Dem are linearly adjacent. Thus, only the Dem in D will be pronounced, as shown.18

- (57)

For DR, it is less clear why there is no doubling. As in SR, we assume a null NP. If the two demonstratives are generated in separate positions, however, both the specifier and head of DemP should be pronounced after movement, (58). It seems that additional stipulations would be required to prevent this structure, which results in the ungrammatical nominal *io io ‘dem1 dem2’ (see also footnote 6).

- (58)

Finally, with respect to (56d), SR allows for ilay (NP) DEM, (59), and its structure in (49): There is no [uDem*] feature and no movement; D is realized as ilay. Consequently, the demonstrative is only pronounced in its base position, giving rise to the absence of doubling in the presence of ilay.

- (59)

- Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ilay

- DET

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- DEM

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- ‘I want to buy that white car (which we previously discussed and is near the speaker)’

DR, in contrast, would by default generate *ilay (NP) DEM1 DEM2. As with the pronominal use, we incorrectly expect two instances of the demonstrative to surface, not one, and additional stipulations are required.

Turning finally to the ungrammatical pattern *ny (NP) DEM, (60), neither analysis provides a straight-forward explanation.

- (60)

- *Te

- want

- hividy

- buy

- ny

- DET

- fiara

- car

- fotsy

- white

- ity

- DEM

- aho

- 1sg.nom

- (‘I want to buy this white car’)

If ilay (NP) DEM is possible, ny (NP) DEM should be as well since we analyze ilay and ny alike syntactically. We tentatively suggest that the pattern is ruled out by a selectional incompatibility between ny and demonstratives. Ny is number neutral and selects an NIP whose head does not contain a number feature. This numberless NI head we stipulate cannot select for DemP. In favor of this approach, we note that in Tsimihety, a dialect of Malagasy spoken in the north central region, it is possible to have DEM2 with i, the Tsimihety equivalent of the default determiner ny (V. Dimisy, p.c.):

- (61)

- a.

- Tsimihety dialect

- i

- det

- zaha

- child

- igny

- dem

- ‘this child’

- b.

- Merina dialect

- *ny

- det

- zaza

- child

- iny

- dem

- (‘this child’)

We take these data to indicate that the Merina pattern is not due to some deep semantic incompatibility (and recall that determiners and demonstratives do co-occur in other languages, such as Greek). Further investigation of demonstratives in other Malagasy dialects is beyond the scope of this article but might shed light on the ungrammaticality of (60) and (61b) in Merina.

Summing up, while both the single and the dual representation analyses account for the framing position of demonstratives, we have argued that SR provides a less stipulative account of additional facts: the identicality of the two demonstratives, the lack of doubling in the pronominal use, and the compatibility of a single final demonstrative with the anaphoric determiner ilay.

6 Conclusion

This paper has provided an analysis of framing demonstratives in Malagasy, a rare phenomenon that has yet to be analyzed in the literature. The analysis has both general theoretical and Malagasy-specific implications.

Doubling phenomena, notably predicate clefts, are well-known in the clausal domain but have hardly been recognized in the nominal realm. Malagasy framing demonstratives instantiate a nominal doubling construction. We argued that the construction is most adequately analyzed using a single representation analysis that instantiates a single syntactic instance of the demonstrative. The doubling results from multiple copy spell out. The single representation approach is superior to a dual representation analysis in which the two instances of the demonstrative are base-generated separately.

For concreteness, we adopted a derivation that includes long head movement of the demonstrative. Saab’s (2017) principles for determining the pronunciation of phrasal and head copies yielded two instances of the demonstrative in most cases with such a derivation. Notably, Saab’s analysis applied to Malagasy was able to explain the lack of doubling with pronominal demonstratives. We do not believe, however, that this derivation is the only one possible and we did not attempt to defend the derivation against alternatives, although we did motivate the individual movements within a minimalist context and within the context of Malagasy grammar. The analysis demonstrates that recent approaches to the pronunciation of copies, previously applied to clausal phenomena such as copy predicate clefts, are also useful in analyzing nominal phenomena. This is a welcome result, as one would not expect such mechanisms to only apply in clauses.

Within the context of nominal syntax, the analysis adopts a low position for demonstratives, as argued for by Bernstein (1997), Giusti (1997; 2002), Pangiotidis (2000), Brugè (2002), Shlonsky (2004), Roehrs (2010), Cinque (2010; 2020), among others. To the extent that our analysis of framing demonstratives is successful, it supports this approach to demonstrative syntax, providing evidence from a language typologically distinct from European languages that initially motivated the proposal.

With respect to Malagasy syntax, the analysis posits Nominal Fronting within the Malagasy DP, parallel to Predicate Fronting in the clausal domain. Parallels between clausal and nominal structure are well-known, so this is not necessarily a surprising result, but it provides further impetus to continue to expect such parallels across languages. At the same time, we have only scratched the surface of Malagasy nominal structure and detailed analyses of other nominal phenomena await. In future work, we would also like to extend our analysis of nominal syntax to personal pronouns and proper names. They are relevant to the current topic in as much as demonstratives can occur with these elements, (62).

- (62)

- a.

- Mba

- prt

- tsy

- neg

- misy

- exist

- saina

- intelligence

- loatra

- too

- i

- det

- Soa

- Soa

- iny!

- dem

- ‘Soa (who is not here) is not very intelligent!’ (adapted from Ravololomanga 1996)

- b.

- Ho

- fut

- aiza

- where

- marina

- real

- isika

- 1pl.incl

- ity

- dem

- e?

- prt

- ‘Where are we really going?’ (Jedele & Randrianarivelo 1998)

Our analysis of demonstratives is compatible with proposals for the syntax of personal pronouns (Zribi-Hertz & Mbolatianavalona 1999; Paul & Travis 2022) and proper names (Paul 2018), but we set aside working through the details for future research.

Finally, an anonymous reviewer raises the question of why demonstrative doubling is so rare. We know of no other language with a similar phenomenon, and we have not even encountered another Malagasy dialect that has it, although we have not systematically investigated. We can only speculate on the issue, building on suggestions from the reviewer, but it can be broken down into at least two separate questions: First, why doesn’t Malagasy have HMC-obeying Dem-to-NI-to-D? If it did, I-assignment would mark each of the non-highest instances of Dem for non-pronunciation, resulting in no doubling. The reviewer points out that there is plausibly no motivation for Dem-to-NI in Malagasy. NI has an EPP feature but it is satisfied by movement of NP to spec,NIP. Thus, an intermediate movement of Dem-to-NI is syntactically unmotivated. Second, why don’t other languages which nonetheless have initial demonstratives where Dem arguably moves to D have long head movement of Dem-to-D? If they did, we might expect to see demonstrative doubling in those languages. While long head movement is perhaps less common than local head movement, it is not clear why the former should be almost universally uninstantiated. We suggest that it is the interaction between Dem-to-D and Nominal Fronting that results in other languages not manifesting doubling, rather than the absence of Dem-to-D alone. In Saab’s system, doubling only arises with Dem-to-D if phonological material intervenes between D and Dem. We speculate that other languages may well have Dem-to-D but they do not have Nominal Fronting, or some other operation that places material between D and Dem. If D and Dem are linearly adjacent, I-assignment applies to the base position of Dem, resulting in the pronunciation of Dem only in D. In Malagasy, we have not been able to find empirical evidence that Dem does or does not stop in NI. Our choice of long head movement over local movement was made on theory-internal grounds. This may be the case for other languages as well. To summarize, demonstrative doubling requires Dem-to-D that, additionally, crosses over phonological material in the inflectional layer of the DP. We speculate that it is this combination of requirements that makes the phenomenon so rare.19

Notes

- Some languages allow for possessor doubling within the DP (e.g. German; Weiß 2008) or determiner doubling (so-called Determiner Spreading) (see Alexiadou et al. 2007 for discussion of a range of languages). Tan (2022) reports a case of pronominal doubling within DP in Amarasi. [^]

- Ntelitheos (2012: 64) notes the restricted possibility of prenominal adjectives, which we do not indicate. We have seen some freedom in the ordering of adjectives and possessives and Ntelitheos (2012: 63) reports variation in the ordering of adjectives and numerals, neither of which we will attempt to document or account for. [^]

- Personal pronouns show number distinctions, but we do not discuss them here. [^]

- The one exception we have found is in Rajemisa-Raolison (1966: 53) and Dez (1980: 189), who give examples where DEM2 is not identical to DEM1. DEM2 in these cases is affixed with -katra, -kitra, and -ana. Note, however, that the base for the affixed form is in fact the same as DEM1 (irery in the example below). Our speakers do not accept the affixed forms, so we assume they are no longer in use. B. Ralalaoherivony p.c. tells us that katra is more common in other dialects, but has no specific meaning.

[^]

- (i)

- Avy

- come

- any

- there

- Antsihanaka

- Antsihanaka

- irery

- dem1

- omby

- cow

- vaventy

- big

- ireri-katra

- dem2-??

- ‘Those big cows come from Antsihanaka.’ (Dez 1980: 189)

- Note that the second demonstrative in (11a) appears either before the relative clause or after. It is not possible to have three demonstratives within a single DP. [^]

- As noted by a reviewer, the ungrammaticality of (12b) could be due to a constraint on adjacent homophonous elements. Keenan (1976: 252) shows this constraint applies to Malagasy pronouns. See Section 5 for our account of the lack of doubling with pronominal demonstratives. [^]

- See Paul (2009) for discussion of the contexts in which ny is not required and the resulting interpretations. [^]

- Rajaona (1972: 686–687) indicates that [+visible] demonstratives whose intervocalic consonant in the singular is not zero or -n-, but not itsy/iretsy, are permitted in this pattern. For [–visible] demonstratives, Rajaona indicates that only izato/izatsy/izany are possible. Our empirical findings are more restrictive. [^]

- The reinforcer is obligatory in colloquial Swedish (Bernstein 1997: 91) and Québec French (J. Royer p.c.). [^]

- Demonstratives in Malagasy are morphologically related to locatives. Malagasy has an equally rich inventory of locative pronouns which are related to the singular demonstratives in Table 1 through replacement of the initial vowel. For example, the demonstrative ity ‘this’ is related to the locatives ety ‘here’ and aty ‘there’ via a change in the initial vowel (see Rajaona 1972: 613–632 and Imai 2003 for discussion). [^]

- For Zribi-Hertz & Mbolatianavalona (1999), the presence or absence of NumP plays an important role in their analysis of pronouns. More specifically, only pronouns lacking NumP can be bound variables. [^]

- Travis (2003) and Müller (2021) propose a variant of the single representation analysis, where doubling arises due to reduplication. [^]

- Such long head movement differs from A’ head movement (Koopman 1984; Matushansky 2006; Vicente 2009; Hein 2017; others) in its landing site. A’ head movement targets a specifier, in this case spec,DP. Our analysis could be recast in terms of A’ head movement but would necessitate revising Saab’s (2017) machinery below slightly. Alternatively, A’ head movement of X to spec,YP could be followed by Matushansky’s (2006) m(orphological)-merger, which merges the heads X and Y into a single constituent, yielding the same structure as above. For simplicity, we continue to show head movement to a head position. [^]

- See Paul (2009) for conditions under which ny can be realized as null. We ignore that complication in the formulation of our vocabulary insertion rules. [^]

- Numerous other analyses for PCs in individual languages exist (see Kandybowicz 2008: 80 and Hein 2017: 3 for references), with the focus on two analytical points: i) the movement(s) involved in the derivation and ii) the theoretical machinery that yields multiple copy pronunciation of the verb (phrase). Alternatives in both of these domains could in most cases be applied to the Malagasy demonstrative doubling construction. We do not assert that our derivation in (46) or Saab’s machinery is either the best or only analysis of framing demonstratives. Other derivations and machinery (e.g. Hein 2018; Arregi & Pietraszko 2021) could be used to make this same point, although we do not explore them here. Rather, our proposal demonstrates that the same considerations that go into the analysis of PCs exist in the analysis of nominal structure, but the framing demonstrative construction does not obviously help to decide between competing analyses of multiple copy pronunciation. [^]

- In contrast, head movement that obeys the Head Movement Constraint will not lead to doubling because each movement is local and triggers I-Assignment. For the case at hand, when Dem moves to D, it must not stop in NI in our analysis; otherwise, only the highest copy of Dem would be pronounced. [^]

- Rajaona (1972: 91–92, 684–687) proposes a dual representation analysis in which DEM2 is an appositive. The shortcomings of our approach discussed in the following section also apply to his analysis. [^]

- Alternatively, we could assume that pronominals do not involve an abstract nominal, in which case, the derivation would converge with no doubling if we stipulate that NI’s EPP feature can go unchecked or that NIP is absent. [^]

- The other Malagasy dialects that we are aware of have Nominal Fronting but they do not have Dem-to-D, i.e. the null D head with a strong Dem-feature, and, thus, no framing demonstratives. [^]

Abbreviations

Glossing follows the Leipzig Glossing Conventions with the following additions: cl: clitic; hab: habitual; prep: preposition.

Ethics and consent

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Western Ontario Non-Medical Research Ethics Board and the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Acknowledgements

The data reported here come from published books and articles as well as elicitation sessions with native speakers. Speakers were presented with sentences and phrases in Malagasy and asked to judge their grammaticality. In some cases, speakers were asked to translate sentences and phrases from English or French into Malagasy. All Malagasy data are from the Merina dialect of the Central Highlands unless otherwise indicated. We thank our consultants Vololona Razafimbelo, Bodo and Voara Randrianasolo, and Vanilla Dimisy, as well as audiences at MOTH 2022, TripleAFLA 2022, and the University of British Columbia. We also appreciate the questions and comments from three anonymous reviewers and the Glossa editor, which led to significant improvements in our analysis. Any errors are our own.

Funding information

This research was partially funded by SSHRC Insight Grant 435 2019 0581.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2001. The predicate-cleft construction in Russian. In Franks, Steven & Holloway King, Tracy & Yadroff, Michael (eds.), Annual Workshop on Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics: The Bloomington Meeting, Vol. 9, 1–18. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Abney, Steven. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.

Aissen, Judith. 1992. Topic and focus in Mayan. Language 68. 43–80. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1992.0017

Aldridge, Edith. 2004. Ergativity and word order in Austronesian languages. Cornell, NY: Cornell University dissertation.

Alexiadou, Artemis & Haegeman, Liliane & Stavrou, Melita. 2007. Noun phrase in the generative perspective. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110207491

Antonenko, Andrei. 2018. Predicate doubling in Russian: One process or two? Paper presented at FASL 27, Stanford University.

Arregi, Karlos & Pietraszko, Asia. 2021. The ups and downs of head displacement. Linguistic Inquiry 52. 241–290. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00377

Bernstein, Judy B. 1997. Demonstratives and reinforcers in Romance and Germanic languages. Lingua 102. 87–113. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(96)00046-0

Bleaman. Isaac. 2022. Predicate fronting in Yiddish and conditions on multiple copy Spell-Out. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 40. 393–424. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-021-09512-3

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2002. A-chains at the PF-interface: Copies and ‘covert’ movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20. 197–267. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015059006439

Boeckx, Cedric & Hornstein, Norbert & Nunes, Jairo. 2007. Overt copies in reflexive and control structures: A movement analysis. University of Maryland Working Papers in Linguistics 15. 1–45.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2006. Differences between the wh-scope-marking and wh-copy constructions in Passamaquoddy. Linguistic Inquiry 37. 25–49. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/002438906775321166

Brugè, Laura. 1996. Demonstrative movement in Spanish: A comparative approach. University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics 6(1). 1–61.

Brugè, Laura. 2002. The positions of demonstratives in the extended nominal projection. In Cinque, Guglielmo (ed.), Functional structure in DP and IP: The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 1, 15–53. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195148794.003.0002

Cable, Seth. 2004. Predicate clefts and base-generation: Evidence from Yiddish and Brazilian Portuguese. Ms. MIT.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 1994. On the internal structure of pronominal DPs. The Linguistic Review 11. 195–219. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/tlir.1994.11.3-4.195

de Cat, Cécile. 2007. French dislocation: Interpretation, syntax, acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199230471.001.0001

Cheng, Lisa. 2007. Verb copying in Mandarin Chinese. In Corver, Norbert & Nunes, Jairo (eds.), The copy theory of movement, 151–174. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.107.07che

Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In Hale, Kenneth & Keyser, Samuel Jay (eds.), The view from Building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, 1–52. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Also published in Noam Chomsky, The Minimalist Program, 167–217, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995.]

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195115260.001.0001

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2005. Deriving Greenberg’s Universal 20 and its Exceptions. Linguistic Inquiry 36. 315–332. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/0024389054396917

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2010. The syntax of adjectives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262014168.001.0001

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2020. The syntax of relative clauses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9781108856195

Cole, Peter & Hermon, Gabriella. 2008. VP raising in a VOS language. Syntax 11. 144–197. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2008.00106.x

Davies, William. 2005. Madurese prolepsis and its implications for a typology of raising. Language 81. 645–665. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2005.0121

Déprez, Viviane. 1992. Raising constructions in Haitian Creole. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 10. 191–231. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00133812

Dez, Jacques. 1980. Structures de la langue malgache. Paris: POF Études.

Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives. Form, function, and grammaticalization. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.42

Du Plessis, Hans. 1977. Wh movement in Afrikaans. Linguistic Inquiry 8. 723–726.

Fanselow, Gisbert & Mahajan, Anoop. 2000. Towards a minimalist theory of wh-expletives, wh-copying, and successive cyclicity. In Lutz, Uli & Müller, Gereon & von Stechow, Arnim (eds.), Wh-scope marking, 195–230. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.37.08fan

Felser, Claudia. 2004. Wh-copying, phases, and successive cyclicity. Lingua 114. 543–574. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(03)00054-8

Fox, Danny & Nissenbaum, Jon. 1999. Extraposition and scope: a case for overt QR. In Bird, Sonya & Carnie, Andrew & Haugen, Jason D. & Norquest, Peter (eds.), Proceedings of the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics 18, 132–144. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Fugier, Huguette. 1999. Syntaxe malgache. Louvain: Peeters.

Giusti, Giuliana. 1997. The categorial status of determiners. In Haegeman, Liliane (ed.), The new comparative syntax, 95–124. London: Longman.

Giusti, Giuliana. 2002. The functional structure of noun phrases. A bare phrase structure approach. In Cinque, Guglielmo (ed.), Functional structure in DP and IP: The cartography of syntactic structures, Vol. 1, 54–90. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195148794.003.0003

Haddad, Youssef A. 2009. Copy control in Telugu. Journal of Linguistics 45. 69–109. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226708005525

Harizanov, Boris & Gribanova, Vera. 2019. Whither head movement? Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 37. 461–522. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9420-5

Hein, Johannes. 2017. Doubling and do-support in verbal fronting: Towards a typology of repair operations. Glossa 2. 1–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.161

Hein, Johannes. 2018. Verbal fronting: Typology and theory. Leipzig: Universität Leipzig dissertation.

Hirschbühler, Paul. 1997. On the source of lefthand NPs in French. In Anagnostopoulou, Elena & van Riemsdijk, Henk & Zwarts, Frans (eds.), Materials on left dislocation, 151–192. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.14.06hir

Imai, Shingo. 2003. Spatial deixis. Buffalo, NY: SUNY dissertation.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1977. X-bar syntax: A study of phrase structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jedele, Thomas & Randrianarivelo, Lucien. 1998. Malagasy newspaper reader. Kensington: Dunwoody Press.

Joseph, Brian. 1976. Raising in Modern Greek: A copying process? In Hankamer, Jorge & Aissen, Judith (eds.), Harvard Studies in Syntax and Semantics Vol. II, 241–278. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Department of Linguistics.

Kandybowicz, Jason. 2008. The grammar of repetition: Nupe syntax at the syntax-phonology interface. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.136

Keenan, Edward. 1976. Remarkable subjects in Malagasy. In Li, Charles (ed.), Subject and topic, 247–301. New York: Academic Press.

Keenan, Edward. 2008. The definiteness of subjects and objects in Malagasy. In Corbett, Greville & Noonan, Michael (eds.), Case and grammatical relations, 241–261. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.81.12kee

Koopman, Hilda. 1984. The syntax of verbs: From verb movement in Kru languages to Universal grammar. Dordrecht: Foris.

Koopman, Hilda. 1999. The internal and external distribution of pronominal DPs. In Johnson, Kyle & Roberts, Ian (eds), Beyond principles and parameters, 91–132. Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4822-1_4

Landau, Idan. 2006. Chain resolution in Hebrew V(P)-fronting. Syntax 9. 32–66. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2006.00084.x

Landau, Idan. 2011. Predication vs. aboutness in copy raising. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29. 779–813. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-011-9134-4

Law, Paul. 2006. Argument marking and the distribution of wh-phrases in Malagasy, Tagalog, and Tsou. Oceanic Linguistics 45. 153–190. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/ol.2006.0013

Lee, Felicia. 2003. Anaphoric R-expressions as bound variables. Syntax 6. 84–114. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9612.00057

Lema, José & Rivero, María-Luisa. 1990. Long head movement: ECP vs. HMC. In Carter, Juli (ed.), Proceedings of NELS 20. Amherst, MA: GLSA, University of Massachusetts.

Leu, Thomas. 2007. These HERE demonstratives. U. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 13(1). 141–154.