1. Introduction — Reflexives and Reciprocals in JA

As is well known, reflexivity and reciprocality represent two different but related linguistic concepts, and we often witness more than one way of their grammaticalization. In Jordanian Arabic (JA), for example, reflexivization may be achieved in at least two ways. As in (1) below, it may be represented syntactically with the internal argument of the verb appearing as a SELF-anaphor.1

- (1)

- l-walad1

- the-boy.nom

- ʔaddab

- behaved

- nafs-uh1.

- self-him.acc

- ‘The boy behaved himself.’

As shown in (2) below, it may also be represented morphologically when a reflexive morpheme (e.g., t-) is affixed to the verb.

- (2)

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-ʔaddab.

- t-behaved

- ‘The boy behaved. (= The boy behaved himself.)’

Similarly, reciprocal constructions in JA fall into two types, one making use of reciprocal anaphors as in (3) and the other involving overt morphological marking on the verb as in (4).2

- (3)

- l-waladeen<1+2>

- the-boys.dl.nom

- ʕaawanu

- helped

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.acc

- l-baʕð̣<1↔2>.

- the-some.acc

- ‘The two boys helped each other.’

- (4)

- l-waladeen

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-ʕaawanu.

- t-helped

- ‘The two boys helped each other.’

In the remainder of this study, for the sake of convenience, we label the constructions as in (1) and (3) “syntactic reflexives/reciprocals” and those as in (2) and (4) “morphological reflexives/reciprocals,” paying attention to the distinct surface forms of the involved verbs. These contrastive labelings, however, will turn out to be too loose eventually as our analyses proceed.

In traditional Arabic grammar, reflexive constructions as in (1)–(2) and reciprocal constructions as in (3)–(4) are generally considered to involve a parallel structure. That is, reflexive/reciprocal verbs lacking overt morphological marking as in (1) and (3) are treated as transitive and must therefore take an anaphor as their object. In contrast, morphologically marked verbs as in (2) and (4) are analyzed as intransitive, reflexive or reciprocal (see Wright 1896; Holes 2004; Ryding 2005). Similar analyses are often adopted for other languages like Greek and Hebrew as well (e.g., Reinhart & Siloni 2005; Dimitriadis 2008b; Siloni 2008; 2012).

There is one issue that has caused controversy in the literature when this transitive-intransitive dichotomy is adopted. It is how the morphologically marked one-place construction can be assimilated to the syntactically represented two-place construction in providing their interpretations. Reinhart & Siloni (2005), for instance, proposed that “morphological” reflexive constructions in Hebrew like (5b) below be analyzed as involving two syntactic operations which let this sentence be interpreted on a par with (5a): what they call “reflexivization bundling” and accusative Case absorption.

- (5)

- a.

- Dan

- Dan

- raxac

- washed

- et

- om

- acmo.

- himself

- ‘Dan washed himself.’

- b.

- Dan

- Dan

- hitraxec.

- refl.washed

- ‘Dan washed.’ (Reinhart & Siloni 2005: 390)

They hypothesize that the bundling operation first fuses the external theta-role of the two-place verb with its internal one (e.g., Agent and Theme) forming one complex theta-role, and then assigns this complex theta-role to the sole syntactic argument, the subject. As a result, the verb is realized as a one-place predicate, and the internal argument need not be syntactically projected or case-marked while it is expressing a two-place thematic relation.

Pushing the same idea, Siloni (2001; 2008; 2012) further contends that a reciprocal construction in Hebrew like (6b) below undergoes a “reciprocalization bundling” operation (by which the external and internal theta-roles are fused and assigned to the subject argument) as well as absorption of accusative Case (see also Laks 2007), and becomes interpreted on a par with (6a).

- (6)

- a.

- Hem

- they

- niʃku

- kissed

- {

- ze

- this

- et

- acc

- ze

- this

- /

- exad

- one

- et

- acc

- ha-ʃeni

- the-second

- }.

- ‘They kissed each other.’

- b.

- Hem

- they

- hitnaʃku.

- recip.kissed

- ‘They kissed.’ (Siloni 2008: 452)

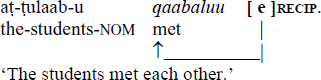

Contrary to the studies described just above, LeTourneau (1998) argues that a morphologically marked reciprocal in Standard Arabic involves a phonetically null internal argument. To make a long story short, he proposes that the implicit reciprocal ([e]RECIP) base-generated in the object position in (7a) below is syntactically raised to the left periphery of the verbal stem. The moved [e]RECIP in this position then is claimed to be morphologically realized as the prefix ta-, yielding the structure in (7b). (The data below from Standard Arabic are adapted from LeTourneau 1998: 106–109, 111.)

- (7)

- a.

- b.

- aṭ-ṭulaab-u

- the-students-nom

- ta-qaabaluu.

- ta-met

- ‘The students met each other.’

Bar-Asher Siegal (2016: 26–27) also offered a semantic motivation for postulating an implicit internal argument of the so-called reciprocal predicates in Hebrew, which also appear with a t-morpheme (in the form hit-V). First, comparing the interpretations of (8a) and (8b) below, he points out that reciprocal interpretations in this construction arise due to the pragmatic relation holding between the two arguments rather than the morphological function of hit-V. (Note the absence of reciprocality in (8b).)

- (8)

- a.

- Josi

- Yosi

- hitxabek

- hit-hugged

- im

- with

- Rina.3

- Rina

- ‘Yosi and Rina hugged each other.’

- b.

- Josi

- Yosi

- hitxabek

- hit-hugged

- im

- with

- ha-karit.

- the-pillow

- ‘Yosi hugged the pillow.’

He then characterizes hit-V as a dyadic predicate that obligatorily selects both external and internal arguments, as described in (9).

- (9)

- hit-V: (hit-Ver, hit-Ved) (N.B. -er as in killer and -ed as in killed in English)

This enforces the presence of a phonetically empty implicit internal argument even when an overt object is missing as in (10a) and (10c).

- (10)

- a.

- Josi

- Yosi

- ve-Rina

- and-Rina

- hitnaʃku

- hit-kissed

- [ e ]RECIP.

- ‘Yosi and Rina kissed each other.’

- b.

- Josi

- Yosi

- hitnaʃek

- hit-kissed

- im

- with

- Rina.

- Rina

- ‘Yosi and Rina kissed each other.’

- c.

- Rina

- Rina

- hitnaʃqa

- hit-kissed

- [ e ]

- ha-jom

- the-day

- b-a-paʔam

- in-the-time

- ha-riʃona.

- the-first

- ‘Rina and someone kissed each other today for the first time.’

Bar-Asher Siegal points out that this analysis permits us to capture all the interpretations in (8a–b) and (10a–c) uniformly, whether they involve a transitive or an intransitive predicate, a plural or a singular subject, or a reciprocal or a non-reciprocal interpretation. Note that the so-called oblique argument is regarded as serving as the internal argument of the predicate in (10b) and presumably in (10a) and (10c) as well, whether it is overt or covert. These cross-language studies encourage us to hypothesize that the optionality of the oblique reciprocal argument in (11) below in fact is analyzable in two ways as illustrated in (12), in which either an overt or empty reciprocal anaphor appears as the complement of a two-place verb in JA.45

- (11)

- l-waladeen<1+2>

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-ʕaawanu

- t-helped

- (maʕ

- with

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.gen

- 1-baʕð̣<1↔2>).

- the-some.gen

- ‘The two boys helped each other.’

- (12)

- l-waladeen<1+2>

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-ʕaawanu

- t-helped

- {maʕ

- with

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.gen

- 1-baʕð̣<1↔2>

- the-some.gen

- / [ e ]RECIP<1↔2>}.

- ‘The two boys helped each other.’

Crucially, on the other hand, morphological reflexives are prohibited from cooccurring with an overt anaphor, as illustrated by (13) below, making a sharp contrast with the morphological reciprocal in (11) above.

- (13)

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-ʔaddab

- t-behaved

- (*maʕ

- with

- nafs-uh1).

- self-him.gen

- ‘The boy behaved himself.’

This observation leads us to take the position that morphologically marked reflexives indeed project only one argument syntactically although we leave it open how such a one-place construction comes to be derived and yields a two-place interpretation without involvement of an empty syntactic argument.

To sum up, comparison of reflexive and reciprocal constructions leads us to the following hypotheses about “morphological” reflexives and reciprocals in JA: (i) t-marked reflexives project only one but t-marked reciprocals project two syntactic arguments, and (ii) when t-marked reciprocals are not accompanied by an overt reciprocal anaphor, they involve a phonetically empty internal argument. These hypotheses thus lead us to shy away from Siloni’s (2001; 2008; 2012) bundling analysis of morphological reciprocals as in (6b), which induces valency reduction, (at least for JA, in which each of the two arguments in the reciprocal construction separately receives a thematic role).6

The remainder of this work proceeds as follows. In Sections 2, we first define the terms “collectivity” and “distributivity” as we use in this work. Then, appealing to these notions, we demonstrate the interpretive contrast between “morphological” and “syntactic” reciprocals, which leads us to identify collectivity as the function of the t-morpheme in JA.7 Sections 3 attempts to identify the formal apparatuses that capture the semantics of collectivity. Finally in Section 4, we will analyze the morphological properties of the t-marked reflexives and reciprocals, paying attention to the semantics of their input and output verbs.

2. The interpretive properties of reciprocals

In this section, we would like to examine and discuss the interpretive properties of reciprocals in JA. In pursuit of this topic, we will find out that several semantic notions such as collectivity, reciprocality and simultaneity are rather intricately intertwined in the interpretation of reciprocals in JA. Our goal in this section is: (i) to clearly define the notion of collectivity and distinguish it from distributivity, and (ii) to abstract collectivity from reciprocality and simultaneity/symmetricity. In the process of fulfilling these tasks, we will be led to identify the exact semantic function associated with the so-called “reciprocal” t-morphemes in JA as collectivity.

2.1 Collectivity and distributivity

In Section 1, we presented two types of reciprocal sentences in JA: syntactic and morphological reciprocals. We then adopted the hypothesis that they are structurally parallel and involve a two-place construction even when the complement reciprocal anaphor of the t-marked predicate is realized covertly, as exemplified in (14) and (15).

- (14)

- l-ʔaxu1

- the-brother.nom

- w-ʔuxt-uh2

- and-sister-his.nom

- ʕaawanu

- helped

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.acc

- l-baʕð̣<1↔2>.

- the-some.acc

- ‘The brother and his sister helped each other.’

- (15)

- l-ʔaxu1

- the-brother.nom

- w-ʔuxt-uh2

- and-sister-his.nom

- t-ʕaawanu

- t-helped

- {maʕ

- with

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.gen

- 1-baʕð̣<1↔2>

- the-some.gen

- / [ e ]RECIP<1↔2> }.

- ‘The brother and his sister helped each other.’

When it comes to their interpretations, however, “syntactic” and “morphological” reciprocals exhibit differences. First, in the syntactic reciprocal sentence as in (14), the expressed reciprocality can be semantically construed either distributively or collectively. That is, the two subeventualities involved in the reciprocal helping in (14) may have “distributively” occurred at different times and/or in different locations, for example, as in the situation such that the brother financially supported the sister while she went to college and the sister looked after the brother when he became seriously ill in later years. Alternatively, the reciprocal helping in (14) may also have occurred “collectively,” with the involved subeventualities significantly overlapping (spatio)temporally, for example, as in the situation such that the brother and the sister clung to each other and warmed themselves in a cabin when they got lost in a snow-covered mountain (with “complete simultaneity”). Collective reciprocal helping in (14) may also have occurred with somewhat looser, “partial (or situational)” simultaneity, for example, in the situation such that the brother and his sister teamed up and collaboratively finished cleaning the house, the brother vacuuming the floor and the sister wiping the windows and furniture. We define the notions collectivity and distributivity in this particular way in the context of the event semantics (as will be formalized in Section 3). Therefore, caution should be exercised to eliminate any misunderstanding that may arise when these terms are used in some other sense.

The availability of both collective and distributive interpretations in (14) can be confirmed when we observe that this sentence can be felicitously followed either by distributive adjuncts as in (16a–b) or by a collective adjunct as in (16c).8

- (16)

- a.

- bi-t-tanaawub ‘taking turns/in turn’

- in-the-turn.gen

- b.

- b-ʃakel

- in-manner.gen

- munfaṣil ‘separately’

- separate.gen

- c.

- sawijjeh ‘together’

- together.acc

Reciprocal constructions involving morphologically t-marked verbs as in (15), on the other hand, only permit the collective interpretation, and are thus compatible with the collective but not distributive adjuncts, as shown in (17).9

- (17)

- l-ʔaxu1

- the-brother.nom

- w-ʔuxt-uh2

- and-sister-his.nom

- t-ʕaawanu

- t-helped

- (maʕ

- with

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.gen

- 1-baʕð̣<1↔2>)

- the-some.gen

- {

- oksawijjeh

- together.acc

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The brother and his sister helped each other { oktogether / #taking turns }.’

The same contrast arises even when the reciprocal anaphor baʕð̣-hum 1-baʕð̣ is replaced by an empty anaphor [e]RECIP (indicated in (17) as the optionality of the overt anaphor).10

Another such pair of “syntactic” and “morphological” reciprocal sentences are presented in (18) below, in which the same contrast can be observed.

- (18)

- a.

- l-taaʤreen<1+2>

- the-businessmen.dl.nom

- faaṣalu

- haggled

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.acc

- l-baʕð̣<1↔2>.

- the-some.acc

- ʕala

- on

- l-ʔasʕaar

- the-prices.gen

- {

- okwaʤh-an

- face-acc

- li-waʤh

- for-face.gen

- /

- okbi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The two businessmen haggled with each other over the prices { okface to face / okin turn }.’

- b.

- l-taaʤreen<1+2>

- the-businessmen.dl.nom

- t-faaṣalu

- t-haggled

- (maʕ

- with

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.gen

- l-baʕð̣<1↔2>)

- the-some.gen

- ʕala

- on

- l-ʔasʕaar

- the-prices.gen

- {

- okwaʤh-an

- face-acc

- li-waʤh

- for-face.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The two businessmen haggled with each other over the prices { okface to face / #in turn }.’

Once again, the distributive interpretation available in the syntactic reciprocal in (18a) becomes unavailable in the morphological reciprocal in (18b). Therefore, (18a) is compatible with the situation such that the first businessman haggled with the second businessman over the prices of some items on one occasion and the second businessman haggled with the first businessman over the prices of different items on another occasion. On the other hand, (18b) is compatible only with the situation such that the two businessmen haggled with each other over the prices on a single occasion. Note here that the collectivity in (18b) involves what was identified above as overlapping subeventualities induced by “partial (or situational)” simultaneity. While the mutual haggling took place “collectively” within a single business session, the two businessmen were not necessarily talking to each other at the very same moment. In other words, the overlapping subeventualities required by the t-morpheme in JA can be induced by either complete or partial simultaneity.11

Thus, we now face a task of having to explicate the observed contrast between “syntactic” and “morphological” reciprocals in JA, in particular, why the collective interpretation becomes obligatory only in the latter.

2.2 Reciprocality and collectivity

One might consider that the obligatory collectivity discussed above arises in one way or another from a reciprocal anaphor as its source. This, however, does not seem to be the case since the contrast between “syntactic” and “morphological” reciprocals arises while both of them involve a reciprocal anaphor, for example as we saw in (18a–b) above. Reciprocal anaphors, in other words, are susceptible to both collective and distributive interpretations.

We also observe in (19) below that a morphologically t-marked predicate is incompatible with adjunct expressions enforcing distributivity such as bi-t-tanaawub ‘taking turns’ and b-ʃakel munfaṣil ‘separately’.

- (19)

- l-ʔaxu

- the-brother.nom

- w-ʔuxt-uh

- and-sister-his.nom

- t-ʕaawanu

- t-helped

- maʕ

- with

- ʔabuu-hum

- father-their.gen

- {

- oksawijjeh

- together.acc

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub

- in-the-turn.gen

- /

- #b-ʃakel

- in-manner.gen

- munfaṣil }.

- separate.gen

- ‘The brother and his sister helped their father {oktogether/#taking turns/#separately}.’

Note that (19) does not involve any reciprocal anaphor or reciprocal interpretation.

Researchers like Dimitriadis (2008b), Siloni (2008) and Bar-Asher Siegal (2016) report that morphologically derived predicates similar to the t-marked verb in (19) involve reciprocality between the subject and the (comitative) complement in Greek, German and Hebrew, which they called “discontinuous (reciprocal) construction.” The sentence in (19), however, can make up a felicitous discourse even when it is followed by another sentence negating reciprocality (square-bracketed below) in (20).

- (20)

- l-ʔaxu

- the-brother.nom

- w-ʔuxt-uh

- and-sister-his.nom

- t-ʕaawanu

- t-helped

- maʕ

- with

- ʔabuu-hum

- father-their.gen

- [

- laakin

- but

- ʔabuu-hum

- father-their.acc

- maa

- neg

- t-ʕaawan

- t-helped

- maʕ-hum ].

- with-them.gen

- ‘The brother and his sister helped their father [ but their father did not help them ].’

This suggests that (19) does not involve any reciprocal interpretation between the subject and the complement.12 After we have discussed the semantics and morphology involved in collectivity, we will point out in Section 4.4 that “discontinuous reciprocals” indeed are possible in JA but only under restricted circumstances.

In short, collectivity is enforced on morphologically t-marked predicates whether or not reciprocal anaphors are introduced into a sentence, i.e., independently of reciprocality. This observation suggests that the function of the t-morpheme in JA should be characterized independently of reciprocality.

2.3 Lexically induced simultaneity and collectivity

Many researchers have identified and discussed what they call “symmetrical” (or “collective/group-level/mutual”) predicates in English as in (21) below, which permit what can be sensed as reciprocality without requiring an overt reciprocal anaphor (e.g., Lasersohn 1995; Carlson 1998; Link 1998; Peres 1998; Lønning 2011).

- (21)

- John and Mary kissed/hugged/met/married.

Crucially, the “reciprocality” expressed by each verb in (21) does not permit distributed multiple events. “John and Mary kissed,” therefore cannot properly describe, for example, the situation such that Mary kissed John on his cheek after John kissed Mary on her forehead. Carlson (1998: 45) argues that “symmetrical” predicates denote a singular event but their lexically entailed mutuality holding between the atomic individuals of a plural subject induces obligatorily reciprocal and collective interpretations. (See also Link 1998: 7, 49 for a similar analysis.) It seems to be true that the lexical meanings of “symmetrical” predicates induce the sense of simultaneity and mutuality because of the necessarily arising shared experience/situation in the induced eventualities.

One may suspect that such lexical semantics of the involved predicates may also play a crucial role in inducing obligatory collectivity in JA, at least in some of the cases discussed above, e.g., (18b) involving the “symmetrical” predicate faaṣalu ‘haggled’. It indeed is the case that a distributive adjunct is anomalous in (22) below, in which the “symmetrical” verb gaabalu ‘met’ appears even without any reciprocal anaphor present overtly or covertly.

- (22)

- Bader

- Bader.nom

- w-Bandar

- and-Bandar.nom

- t-gaabalu

- t-met

- maʕ

- with

- Sawsan

- Sawsan.gen

- (#bi-t-tanaawub).

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘Bader and Bandar met Sawsan (#in turn).’

There are reasons, however, to believe that such lexically induced simultaneity is not necessarily the source of the obligatory collectivity we observed in JA (although it seems to be inducing plurality of eventualities). First, as Carlson (1998: 43) notes, the predicates in question behave as “collective” only when they are used intransitively with a plural NP as their subject. The transitive use of kiss in (23a) below, for example, can denote multiple events but no simultaneous or symmetrical entailment arises at least between the atomic individuals of the plural subject John and Mary.

- (23)

- a.

- John and Mary kissed their daughter.

- b.

- John and Mary kissed each other.

Even when a reciprocal anaphor appears as the object as in (23b), the transitive use of kiss can felicitously describe the distributed multiple events like John’s kissing Mary on the arm and Mary’s kissing John on the arm (observation ascribed to Lila Gleitman). The situation is exactly the same in (24a–b) below, the JA counterpart of (23a–b).

- (24)

- a.

- Bader

- Bader.nom

- w-Sarah

- and-Sara.nom

- baasu

- kissed

- bint-hum.

- daughter-their.acc

- ‘Bader and Sara kissed their daughter.’

- b.

- Bader1

- Bader.nom

- w-Sarah2

- and-Sara.nom

- baasu

- kissed

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.acc

- l-baʕð̣<1↔2>.

- the-some.acc

- ‘Bader and Sara kissed each other.’

Note now that the sentence in (22) as well involves a two-place construction, and no simultaneity between Bader and Bandar seems to be entailed, suggesting that the obligatory collectivity in this sentence (as per our definition) was not caused by lexically induced simultaneity of the verb gaabalu ‘met’.

Second, even when an identical “symmetrical” verb is used, whether or not it exhibits obligatory collectivity depends on the form it appears in, i.e., whether it is morphologically t-marked or not. Compare, for instance, (25) below with (22) above.

- (25)

- Bader

- Bader.nom

- w-Bandar

- and-Bandar.nom

- gaabalu

- met

- Sawsan

- Sawsan.acc

- (okbi-t-tanaawub).

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘Bader and Bandar met Sawsan (okin turn).’

While both sentences involve a symmetrical verb gaabalu ‘met’, a distributive reading is permitted in (25) but not in (22). The contrast in question, in other words, is independent of the symmetricity of the verb itself but rather is dependent on the verb forms.

Various other “symmetrical” verbs also exhibit the contrast in question when they appear in “syntactic reciprocal” sentences on the one hand and in “morphological reciprocal” sentences on the other:

- (26)

- a.

- z-zalameh1

- the-man.nom

- w-marat-uh2

- and-wife-his.nom

- ʕaanagu

- hugged

- /

- baawasu

- kissed

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.acc

- l-baʕð̣<1↔2>

- the-some.acc

- {

- okb-laħð̣et

- in-moment.gen

- bidaajet

- beginning.gen

- raas

- head.gen

- es-saneh

- the-year.gen

- /

- okbi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The man and his wife hugged/kissed each other { okat the moment the new year began / oktaking turns }.’

- b.

- z-zalameh1

- the-man.nom

- w-marat-uh2

- and-wife-his.nom

- t-ʕaanagu/

- t-hugged

- t-baawasu

- t-kissed

- (maʕ

- with

- baʕð̣-hum

- some-them.gen

- l-baʕð̣<1↔2>)

- the-some.gen

- {

- okb-laħð̣et

- in-moment.gen

- bidaajet

- beginning.gen

- raas

- head.gen

- es-saneh

- the-year.gen

- #bi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The man and his wife hugged/kissed each other { okat the moment the new year began / #taking turns }.’

The morphologically unmarked verbs ʕaanagu ‘hugged’ and baawasu ‘kissed’ in (26a) are compatible with both of the adjuncts ‘at the moment the new year began’ and ‘taking turns’, yielding either a collective or distributive interpretation. When the same verbs are morphologically t-marked as in (26b), on the other hand, the distributive adjunct ‘taking turns’ suddenly becomes incompatible. It is true that the distributive adjunct is incompatible even when the morphologically t-marked verbs in (26b) are not accompanied by an overt reciprocal anaphor (indicated by its optionality). Therefore, they may appear to act as an intransitive “genuine” symmetrical verb at first sight. As discussed in Section 1, however, the seemingly intransitive construction here should be analyzed as involving an empty anaphor [e]RECIP in the complement, and hence lexically entailed simultaneity is unlikely to arise directly between the conjoined subjects.13

Finally, the contrast in question between the t-marked and non-t-marked verbs can be observed even when the verb is non-symmetrical in meaning as in (27) and (28).

- (27)

- Bader

- Bader.nom

- w-Bandar

- and-Bandar.nom

- t-saamaħu

- t-forgave

- maʕ

- with

- Sawsan

- Sawsan.gen

- (#bi-t-tanaawub).

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘Bader and Bandar forgave Sawsan (#in turn).’

- (28)

- Bader

- Bader.nom

- w-Bandar

- and-Bandar.nom

- saamaħu

- forgave

- Sawsan

- Sawsan.acc

- (okbi-t-tanaawub).

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘Bader and Bandar forgave Sawsan (okin turn).’

(27) is only compatible with the reading that both Bader and Bander forgave Sawsan on one occasion while (28) is compatible with not only such a collective reading but also with a distributive reading: Bader and Bander separately forgave Sawsan, each on a distinct occasion.14

In short, lexically induced simultaneity of predicates should not be regarded as the only source of the obligatory collectivity observed in morphological reciprocals in JA.

2.4 Collective morpheme

Our investigations so far in this section lead us to identify the exact source of the observed obligatory collectivity. Table 1–(i–iii) encapsulate which constructions exhibit optional collectivity and which others obligatory collectivity:

Optional vs. obligatory collectivity.

| Optional collectivity | Obligatory collectivity | ||

| (i) | (14)+(16) | vs. | (17) |

| (18a) | vs. | (18b) | |

| (ii) | vs. | (19) | |

| (28) | vs. | (27) | |

| (iii) | (25) | vs. | (22) |

| (26a) | vs. | (26b) | |

The contrasts shown in (i) indicate that obligatory collectivity is not induced by reciprocal anaphors, whether they are overt or covert. The observations in (ii) tell us that obligatory collectivity in fact can be observed even when no reciprocality whatsoever is involved in the sentence. Finally, the contrast in (iii) demonstrates that obligatory collectivity arises independently of lexically induced mutuality/simultaneity of the so-called “symmetrical” predicates.

While none of reciprocality, mutuality or simultaneity can induce the obligatory collectivity observed in the data listed on the right-hand side of Table 1, there is one thing in common among all of them — the morphological marking of the verbs with the morpheme t-. This observation suggests that obligatoriness of collectivity is either directly induced by or at least coincides with the presence of the morpheme t-. In fact, as illustrated in (29) below, when we eliminate the t-morpheme from the verb in (19) listed under Table 1–(ii), the distributive expression meaning ‘taking turns’ becomes compatible, which further supports this hypothesis. (Note that (29) fills the gap in one of the cells on the left-hand side of Table 1–(ii).)

- (29)

- l-ʔaxu

- the-brother.nom

- w-ʔuxt-uh

- and-sister-his.nom

- ʕaawanu

- helped

- ʔabuu-hum

- father-their.acc

- {

- oksawijjeh

- together.acc

- /

- okbi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The brother and his sister helped their father { oktogether / oktaking turns }.’

Thus, while researchers have generally treated the Arabic t-morpheme examined in this section solely as a reciprocal marker, the facts in JA prompt us to reidentify it as a morpheme inducing collectivity rather than reciprocality. In the rest of this work, we would like to pursue this hypothesis and call the t-morpheme in question a “collective morpheme” or “collectivizer.”15 Accordingly, we will pay most of our attention to collectivity, distancing ourselves from the topic of reciprocality in the discussions that follow.

3. The semantics of collectivity

In this section, we will construct a semantic model, with which we attempt to clarify, first, how plural eventualities and their distributivity and collectivity are semantically derived. To these ends, we adopt the devices proposed by Lasersohn (1998) and Büring (2005), combining and readjusting them.

To begin with, the sentence in (30) below can exhibit either distributive or collective interpretation (as per our definitions of these notions).

- (30)

- John and Mary sang a song.

That is, it can describe John’s singing and Mary’s singing done either on separate occasions or on one occasion. The first step to capture both of these readings is to identify the existence of a plural eventuality. A quite common approach to fulfil this task is to postulate a distributive operator of some kind.16 Büring (2005: 204), for instance, postulates a covert distributive operator (Dist) semantically characterized as in (31).

- (31)

- ⟦ Dist ⟧g = λP<e,t> λZ. ∀x s.t. x ⊑A Z, P(x) (⊑A indicates “atomic part of”)

Roughly, a property ⟦ Dist ⟧g (α) is defined to hold of a plurality Z if and only if α holds of all atomic parts of Z functioning as an argument of the predicate P.

We believe that the collective reading in (30) above can be captured by postulating a covert collective operator (Coll), which operates on the semantics provided by Dist. Coll is defined as in (32) below, which mimics (and simplifies) Lasersohn’s (1998: 278, 288) semantic characterization of the collective adverb together.

- (32)

- a.

- ⟦ Coll Spatiotemporal ⟧g = λP λZ λe [P(e)(Z) & ∀e1, e2 ≤ e

- [[∃yP(e1)(y) & ∃xP(e2)(x)] → K(e1) ∘ K(e2)]]

- b.

- ⟦ Coll Temporal ⟧g = λP λZ λe [P(e)(Z) & ∀e1, e2 ≤ e

- [[∃yP(e1)(y) & ∃xP(e2)(x)] → τ(e1) ∘ τ(e2)]]

Here, P is a predicate, e1 and e2 are two subeventualities in e, and Z is a group of individuals. K in (32a) is a function that maps any eventuality onto both its running time (τ) and space (σ), with the little circle (∘) indicating a significant overlap between the time and location of the two subeventualities. If the subeventualities overlap only in time but not in space, we can simply replace the spatial and temporal function K with the temporal function τ as in (32b). Roughly, a property ⟦ Coll (Spatio)temporal ⟧g, i.e., collectivity, is defined to hold of P if and only if the subeventualities e1 and e2 in the eventuality e significantly overlap in time (and space). We need to take heed of the following three points when we adopt this approach. First, when we discuss the notion of collectivity appealing to Coll, we are paying attention to the overlapping property of eventualities rather than reciprocality, entailed simultaneity, or a single eventuality achieved by a group. Second, we consider that the presence of Coll in a sentence gives rise to obligatory collectivity and also that some constructions may or may not involve Coll, which gives rise to optional collectivity. Third, Coll in (32) is concerned with collectivity in the event semantics while Büring’s (2005) Dist as in (31) is defined without incorporating event semantics. We therefore need to redefine Dist in (31) in order to combine it with Coll in (32). This adjustment can be made by changing the semantic type of the predicate verb V in (31) from <e,<e,t>>> into <e,<e,<ɛ,t>>> and accordingly the types of constituents that combine with its maximal projection VP in order to avoid any type mismatches. The semantic type of the Dist operator, in other words, needs to be changed from <e,t> as in (33a) into <e,<ɛ,t>> as in (33b). (Here, ɛ is meant to indicate the semantic type of eventuality.)

- (33)

- a.

- ⟦ Dist ⟧g = λP<e,t> λZ. ∀x ⊑A Z, P(x) (= (31))

- b.

- ⟦ Dist ⟧g = λP<e, ɛt> λZ λe. ∀x ⊑A Z, P(x)(e)

Redefined under the event semantics, the function of Dist as in (33b) now comes to identify the existence of a plural eventuality such that each atomic individual of a plural argument (typically a subject) functions as a participant in respective subeventualities. Note then that the subeventualities introduced this way may take place either collectively or distributively (as per our definitions of these notions) even if the naming of this operator “Dist” (inherited from the literature) may give the impression that obligatory distributivity arises. In a sense, this operator is labeled “distributive” only because it distributes the atomic individuals of the plural argument among the subeventualities.

In our analysis, we postulate Coll and Dist as the heads projecting their own phrases CollP (Collective Phrase) and DistP (Distributive Phrase), respectively, above VP as in the syntactic representation indicated in (34).

- (34)

- [TP Sbj1 [CollP (Coll) [DistP (Dist) [VP t1 V Complement ]]]]

Presumably, the introduction of these operators is optional though Dist must select VP, and Coll must select DistP as a complement, once they are introduced.

The sentence (30) above thus can be syntactically represented as in any of (35a–c).

- (35)

- a.

- John and Mary [VP sang a song ].

- b.

- John and Mary [DistP Dist [VP sang a song ]].

- c.

- John and Mary [CollP Coll [DistP Dist [VP sang a song ]].

Since (35a) does not involve Dist, no subeventualities arise, which presumably results in the group reading of the subject involving only a single eventuality. Dist in (35b), on the other hand, identifies a plural eventuality, namely, the subeventualities in each of which an atom of the plural subject participates. Since Coll is not involved, its subeventualities receive no restriction and can be ambiguously interpreted as either collective or distributive. To the contrary, Coll introduced in (35c) imposes obligatory overlap on the involved subeventualities and requires that they take place collectively. We consider that which of these interpretations arises depends on the context/pragmatics, and that, in order to represent each such context-dependent interpretation properly, either or both of Dist and Coll are introduced into a syntactic representation. The claim we made on the t-morpheme in JA therefore can be formally embodied as its requirement to co-occur with Coll.

One important and interesting question is whether and what role Dist and Coll might play in the interpretation of reciprocals. Reciprocality induced by reciprocal anaphors is known to exhibit compatibility with distinct contexts involving varied “strength” of reciprocality, ranging from the “strong reciprocality” (i.e., reciprocality conjunctively holding between the involved atomic individuals) as in (36) below to the “weak (or non-symmetric) reciprocality” (i.e., reciprocality disjunctively holding between the involved atomic individuals) as in (37).17

- (36)

- John and Mary kissed each other.

- (37)

- The trays are stacked on top of each other.

Different researchers adopt different approaches to cope with the variation of actual interpretations which fall somewhere between these two interpretations. Dalrymple et al. (1998), for example, postulate a small inventory of reciprocal meanings and hypothesize that a sentence takes the strongest meaning in the inventory when it is consistent with the given context. Bar-Asher Siegal (2020), on the other hand, hypothesizes that the weakest reciprocality is the basic meaning of what he calls “NP-strategy” reciprocals, which can be strengthened depending on the given context and intended implicature. Perhaps, even the opposite approach is at least logically possible, which hypothesizes that the strongest reciprocality is the basic meaning and it can be weakened depending on the context and implicature. Since our main interest in this section is the semantics of collectivity, we are not in a position to evaluate or select any of such approaches to capture the interaction between the semantics of reciprocals and their contexts, or to argue for any particular semantic analysis of reciprocality.18 In Appendix D, nonetheless, we will explore how the operators Dist and Coll can be utilized in describing the semantic interpretation of collectivity when it is combined with (strong) reciprocality in JA.

4. Aspects of T-morphology in Jordanian Arabic

We now pay attention to morphology. The traditional study of verb morphology in Arabic has recognized two distinct functions of morphological t-marking as summarized in Table 2.19

Overview of t-morphology in JA.

|

(i) Input Verb Form |

(ii) Derived Verb Form |

(iii) Root |

(iv) Derived Meanings |

|

| a. | 2 | 5 | ħ-m-m ‘bathe’ | t-ħammamu ‘they bathed{ themselves / #each other }’ |

| b. | 3 | 6 | s-m-ħ ‘forgive’ | t-saamaħu ‘they forgave{ each other / #themselve }’ |

| c. | 1 | 8 | r-m-j ‘throw’ | ʔir-t-amu ‘they threw { themselves / #each other }’ |

| d. | 1 | 8 | f-r-g ‘separate’ | ʔif-t-ragu ‘they separated from{each other / #themselves}’ |

First of all, as exemplified in column (iv), the t-morpheme appears at surface as a prefix in Forms 5 and 6 but as an infix in Form 8. This variation, however, is generally considered to be induced by phonology and all instances of t-morpheme are said to be identifiable as a prefix (see McCarthy 1981: 390). Following this well-accepted suggestion, we will analyze all instances of t-morpheme appearing in all of Forms 5, 6 and 8 as prefixes.

The prefix t- serves as a reflexivizer in Form 5 (Table 2–a) but it has been said to serve as a reciprocalizer in Form 6 (Table 2–b). The same t-morpheme in Form 8, on the other hand, has been said to ambiguously serve as a reflexivizer as in Table 2–c or as a reciprocalizer as in Table 2–d. Reflecting the conclusion we drew in Section 2.4, however, we recognize the t-morpheme in Table 2–b and Table 2–d as a collectivizer rather than a reciprocalizer with the assumption that reciprocality in collective sentences generally arises due to the syntactic presence of a reciprocal anaphor, which may be overt or covert.20

The segregation of these two distinctive functions of t-marking can be confirmed in (38a–d) below. First, the distributive adjunct ‘taking turns/in turn’ is felicitous in (38a) and (38c) but not in (38b) and (38d). That is, collectivity is optional in the former verb forms (5&8) but obligatory in the latter forms (6&8).

- (38)

- a.

- Reflexive (Form 5):

- el-ʔuxteen

- the-sisters.dl.nom

- ez-zɣaar

- the-little.nom

- t-ħammamen

- t-bathed

- bi-l-ħammaam

- in-the-bath.gen

- {

- b-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- bi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The two little sisters bathed { themselves / #each other } in the bath { simultaneously / taking turns }.’

- b.

- Collective (Form 6):

- l-waladeen

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-saamaħu

- t-forgave

- {

- b-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The two boys forgave { each other / #themselves } { simultaneously / #in turn }.’

- c.

- Reflexive (Form 8):

- l-waladeen

- the-boys.dl.nom

- ʔir-t-amu

- t-threw

- ʕa-l-ʔasirrah

- on-the-beds.gen

- {

- b-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- bi-t-tanaawub}.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The two boys threw { themselves / #each other } on the beds { simultaneously / taking turns }.’

- d.

- Collective (Form 8):

- z-zalameen

- the-men.dl.nom

- ʔif-t-ragu

- t-separated

- {

- b-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub }.

- in-the-turn.gen

- ‘The two men separated from { each other / #themselves }{ simultaneously / #in turn}.’

Second, as indicated by the translations, reflexive interpretations are available in (38a) and (38c) but prohibited in (38b) and (38d). Reciprocal interpretations, on the other hand, are available in (38b) and (38d) but prohibited in (38a) and (38c). In Sections 1 and 2 above, we adopted the view that t-reflexives in JA make up a one-place construction while t-collectives make up a two-place construction which permits an empty reciprocal anaphor as the complement. All the interpretive restrictions observed in (38) are in accordance with these morpho-syntactic analyses.

How exactly can the t-morpheme exhibit reflexivity in some cases and collectivity in others? Although this issue is independent of other claims we made above and its full-scale pursuit goes beyond the scope of this paper, we would like to conduct an initial survey on this issue. One possible and perhaps reasonable approach is to hypothesize that the t-morpheme is inherently specified as both potentially reflexive and potentially collective, and that each of these inherent properties is activated only when some specific properties exist in the verb form the t-morpheme is attached to. Though briefly, we would like to explore an analysis of t-morphology along this line, couching it in the syntactic and semantic analyses argued for above.

As summarized in Table 2–(i–ii) above, the t-morpheme in JA takes three distinct verb forms as input and derives three distinct verb forms as output. In what follows, we will examine each such derivation paying attention to the properties of the input verb forms and the specific effects the t-morpheme achieves in each case. For the sake of brevity of our discussion, we will abbreviate “Verb Forms 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8” as “F1, F2, F3, F5, F6 and F8,” respectively, sometimes referring to the verb forms themselves and other times using them as mere labels. In addition, we will use “transitive, unergative and unaccusative” to label the distinct thematic properties of the original consonantal verb roots as in Table 2–(iii) (rather than characterizing a syntactic construction co-occurring with any verb form).

4.1 Derivation of Verb Form 5 from Verb Form 2

As was introduced in Table 2–a above, F5 is derived when the t-morpheme selects F2 as its input. F2, whose form is characterized by the consonant gemination of the second radical (C1VC2C2VC3), makes up a causative construction, as illustrated by (39)–(41) below (cf. Wright 1896; Holes 2004; Ryding 2005, among others). (We are suggesting here that F2-unaccusatives should also be regarded as involving causation, extending a traditional view.)

- (39)

- a.

- F2-transitive:

- l-ʔustaað

- the-teacher.m.nom

- ʕallam

- caused.to.learn

- ṭ-ṭaalib

- the-student.m.acc

- l-ʕazif

- the-playing.acc

- ʕa-li-bjaanoh

- on-the-piano.gen

- ‘The male teacher caused the male student to learn (playing) the piano.

- (= The male teacher taught the male student (playing) the piano.)’

- b.

- l-ʔabu

- the-father.nom

- mallak

- caused.to.own

- ʔibn-uh

- son-his.acc

- sajjaarah.

- car.acc

- ‘The father caused his son to own a car. (= The father got his son a car.)’

- (40)

- F2-unergative:

- huuh

- he.nom

- maʃʃa

- caused.to.walk

- /

- sabbaħ

- caused.to.swim

- /

- ʔaddab

- caused.to.behave

- ʔibn-uh.

- son-his.acc

- ‘He caused his son to walk/swim/behave. (= He made his son walk/swim/behave.)’

- (41)

- F2-unaccusative:

- a.

- ð̣aww

- light.nom

- eʃ-ʃames

- the-sun.gen

- fattaħ

- caused.to.open

- li-wruud.

- the-flowers.acc

- ‘The sunlight caused the flowers to open/bloom.’

- b.

- huuh

- he.nom

- kassar

- caused.to.break

- ʃ-ʃubbaak.

- the-window.acc

- ‘He caused the window to break. (= He broke the window.)’

The effect of F5-t-marking then can be regarded as requiring the causer and causee in F2 be united in reference, as illustrated in (42)–(44).

- (42)

- F5-transitive:

- a.

- ṭ-ṭaalib

- the-student.m.nom

- t-ʕallam

- t-caused.to.learn

- l-ʕazif

- the-playing.acc

- ʕa-li-bjaanoh

- on-the-piano.gen

- ‘The male student caused himself to learn (playing) the piano.’ (= The male student learned / taught himself / self-taught (playing) the piano.)’

- b.

- l-ʔibin

- the-son.nom

- t-mallak

- t-caused.to.own

- sajjaarah.

- car.acc

- ‘The son caused himself to own a car. (= The son got himself a car.)’

- (43)

- F5-unergative:

- l-ʔibin

- the-son.nom

- t-maʃʃa

- t-walked

- /

- t-sabbaħ

- t-swam

- /

- t-ʔaddab.

- t-caused.to.behave

- ‘The son caused himself to walk / swim / behave. (= The son walked / swam / behaved.)’

- (44)

- F5-unaccusative:

- a.

- li-wruud

- the-flowers.nom

- t-fattaħat.

- t-caused.to.open

- ‘The flowers caused themselves to open. (= The flowers bloomed.)’

- b.

- l-gazaaz

- the-glass.nom

- t-kassar.

- t-caused.to.break

- ‘The glass caused itself to break. (= The glass broke by itself.)’

Based upon the interpretations of F5-transitive as in (42) and F5-unergative as in (43), F5-t-morpheme has traditionally been characterized as a “reflexivizer,” while F5-unaccusative as in (44) has been treated separately as (medio)passive (Wright 1896; Ryding 2005). Our extension of the causative analysis of F2 to unaccusatives as in (41), however, makes it possible for us to assimilate all cases of F5 in (42)–(44).

In short, F2 makes up a causative construction, and t-morpheme selecting F2 requires the causer and causee in F2 be united in reference, deriving F5 as a “reflexive” verb.

4.2 Derivation of Verb Form 6 from Verb Form 3

As was summarized in Table 2–b above, an F6 is derived when the t-morpheme selects F3 as its input. F3 (C1V1V1C2V2C3) is identified by the vowel lengthening taking place in its input verb form F1. F3 verbs often imply some kind of loose symmetricity/parallelism, as in (45a–b).

- (45)

- F3-unergatives:

- a.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- ð̣aaħak

- laughed

- *(ṣaaħb-hu).

- friend-his.acc

- ‘The boy laughed with his friend.’

- b.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- raakað̣

- ran

- *(l-bint).

- the-girl.acc

- ‘The boy ran with the girl.’

It is rather difficult to formally characterize the exact semantico-syntactic effect achieved by F3. One descriptive generalization we have managed to come up with, however, is that F3 seems to require the agent argument of the input verb to appear with one more animate (typically human) participant as the initiator of the same eventuality, which in effect paves the way for F3 to involve a plural eventuality under certain conditions to be discussed shortly below. Moreover, what is noteworthy in (45a–b) is that F3-unergatives must appear with an accusative-marked object which is interpreted as an additional agent of the verb. Putting emphasis more on this interpretive effect than its form, we will label this added participant in examples like (45) “agentive object.”21

Similarly, F3-transitives must appear with such an “agentive object” when the object of a transitive verb is inanimate while this extra participant is prohibited when the object is animate, as illustrated by the contrast in each of (46)–(47).22 (Note the distinct positions of * between each pair of sentences.)

- (46)

- F3-transitive:

- a.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- raahan

- bet

- *(ṣaaħb-uh)

- friend-his.acc

- b-maṣaari.

- in-money.gen

- ‘The boy bet money with his friend. (= Both the boy and his friend bet money.)’

- b.

- z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- naada

- called

- (*ṣaaħb-uh)

- friend-his.acc

- l-bint.

- the-girl.acc

- Intended: ‘The man called (the name of) the girl with his friend. (= Both the man and his friend called (the name of) the girl.)’

- (47)

- F3-transitive:

- a.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- ʃaarak

- shared

- *(ṣaaħb-uh)

- friend-his.acc

- ʕa-l-ʕaʃa.

- on-the-dinner.gen

- ‘The boy shared dinner with his friend. (= The boy and his friend shared dinner.)’

- b.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- ʕaawan

- helped

- (*ṣaaħb-uh)

- friend-his.acc

- l-bint.

- the-girl.acc

- Intended: ‘The boy helped the girl with his friend. (= Both the boy and his friend helped the girl.)’

In other words, when (and only when) the agent in the input verb is not accompanied by the second animate/human participant, F3 adds an agentive object, which is to be interpreted as an extra initiator of the same action.

On the other hand, since unaccusative verbs do not involve any agent argument to begin with, they cannot appear in F3 at all, as illustrated in (48) below. Note that these sentences are ungrammatical whether the second participant appears as an accusative-marked object or not, and also whatever interpretive role this participant may be intended to play.

- (48)

- *F3-unaccusatives

- a.

- *li-zhuur

- the-roses.nom

- faataħat

- opened

- ({

- s-samaad

- the-fertilizer.acc

- /

- l-jaasmiin

- the-jasmine.acc

- }).

- Intended: ‘The roses bloomed ({ due to the fertilizer / with the jasmines }).’

- b.

- *l-gazaaz

- the-glass.nom

- kaasar

- broke

- ({

- l-hawa

- the-wind.acc

- /

- s-saguf

- the-roof.acc

- }).

- Intended: ‘The glass broke ({ by the wind / with the roof }).’

Turning now to F6, we have noted that F6-t-morpheme is attached to only those F3s that can yield a plural eventuality. This state of affairs is a natural consequence if F6-t-morpheme is a collectivizer, as argued for in Section 2.4. If only a single eventuality is involved in its input verb form, a collectivizer cannot fulfil its function properly and fails to be interpreted. For instance, while the F3s involving a single eventuality as in (49a–b) below have no problem, the same verbs cannot be turned into F6s, as shown in (50a–b).

- (49)

- a.

- z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- naada

- called

- l-walad

- the-boy.acc

- b-haðiik

- in-that.gen

- l-laħð̣ah.

- the-moment.gen

- ‘The man called the (name of the) boy at that moment.’

- b.

- z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- xaabar

- informed

- ʃ-ʃurṭah

- the-police.acc

- ʕan-illi

- on-what.gen

- ṣaar.

- happened

- ‘The man informed the police about what had happened.’

- (50)

- a.

- *z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- t-naada

- t-called

- ʕa-l-walad

- on-the-boy.gen

- b-haðiik

- in-that.gen

- l-laħð̣ah.

- the-moment.gen

- Intended: ‘The man called the (name of the) boy at that moment.’

- b.

- *z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- t-xaabar

- t-informed

- ʕa-ʃ-ʃurṭah

- on-the-police.gen

- ʕan-illi

- on-what.gen

- ṣaar.

- happened

- Intended: ‘The man informed the police about what had happened.’

If the input F3 involves a plural eventuality, on the other hand, the derived F6 becomes legitimate, with its subeventualities interpreted as obligatorily collective, as we have confirmed with numerous examples in Sections 2.1–2.3. (See (17), (18b), (19), (27), (22) and (26b) listed in the right column of Table 1.)

Having examined all the F6 examples at hand, we have noted that a plural eventuality which their input F3s are required to induce can be established in at least four ways as described in (A)–(D) below.

(A) It is created by parallel subeventualities involving two NPs interpreted as agent as in (51) and (52).

- (51)

- F6-unergative:

- a.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-ð̣aaħak

- t-laughed

- *(maʕ

- with

- ṣaaħb-uh)

- friend-his.gen

- xilal

- while

- muʃaahadet

- watching.gen

- et-tilfizjoon.

- the-television.gen

- ‘The boy laughed with his friend while watching television. (= Both the boy and his friend laughed while watching television.)’

- b.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-raakað̣

- t-ran

- *(maʕ

- with

- l-bint).

- the-girl.gen

- ‘The boy ran with the girl. (= Both the boy and the girl ran.)’

- (52)

- F6-transitive:

- a.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-raahan

- t-bet

- *(maʕ

- with

- ṣaaħb-uh)

- friend-his.gen

- b-maṣaari

- in-money.gen

- ʕala

- on

- sibaag

- race.gen

- el-ħiṣneh.

- the-horses.gen

- ‘The boy bet money with his friend on the horse race. (= Both the boy and his friend bet money on the horse race.)’

- b.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-ħaasab

- t-paid

- *(maʕ

- with

- ṣaaħb-uh)

- friend-his.gen

- ʕala

- on

- el-waʤbeh.

- the-meal.gen

- ‘The boy paid for the meal with his friend. (= Both the boy and his friend paid (their shares of) the money for the meal.)’

In F6-unergative (51a), for example, the addition of the agentive object induces two parallel subeventualities “the boy laughed” and “his friend laughed.” Similarly in the F6-transitives in (52), the second participant is added as an agentive object within the complement PP and induces an extra subeventuality. Thus, in (52a) for example, two parallel subeventualities “the boy bet money” and “his friend bet money” arise.

(B) A plural eventuality required by the F6-t-morpheme can also be created even when the eventuality does not involve parallel subeventualities if at least one of the two participants is plural in number.

When the input verb is transitive, it does not seem to matter whether this plural participant is interpreted as the subject as in (53) or the complement of the verb as in (54).

- (53)

- F6-transitive (Plural subject):

- l-ʔaxu

- the-brother.nom

- w-ʔuxt-uh

- and-sister-his.nom

- t-ʕaawanu

- t-helped

- maʕ

- with

- ʔabuu-hum

- father-their.gen

- {

- oksawijjeh

- together.acc

- /

- #b-ʃakel

- in-manner.gen

- munfaṣil

- separate.gen

- }.

- ‘The brother and his sister helped their father { oktogether / #separately }.’

- (54)

- F6-transitive (Plural complement):

- l-ʔabu

- the-father.nom

- t-ʕaawan

- t-helped

- maʕ

- with

- ʔibn-uh

- son-his.gen

- w-bint-uh

- and-daughter-his.gen

- {

- oklamma

- together.acc

- ʕimlu

- did

- waaʤib-hum

- homework.acc-their

- sawijjeh

- together.acc

- /

- #b-ʃakel

- in-manner.gen

- munfaṣil

- separate.gen

- }.

- ‘The father helped his son and daughter { okwhen they did their homework together / #separately }.’

At first sight, when the input verb is unergative, the plural subject alone appears to suffice to create a plural eventuality required by the F6-t-morpheme, as exemplified by (55a–b).

- (55)

- F6-unergative:

- a.

- l-waladeen

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-ð̣aaħaku

- t-laughed

- {

- okb-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub

- in-the-turn.gen

- }.

- ‘The two boys laughed { oksimultaneously / #in turn }.’

- b.

- l-waladeen

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-raakað̣u

- t-ran

- {

- okb-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub

- in-the-turn.gen

- }.

- ‘The two boys ran { oksimultaneously / #in turn }.’

One question that arises is why the agentive object required in the input F3 need not appear in F6 here. Since an unergative verb requires an agentive object in F3 even with a plural subject, as shown in (56a–b) below, we cannot consider that the plurality of the subject in (55) alone made the appearance of an agentive object unnecessary.

- (56)

- F3-unergative (plural subject):

- a.

- l-waladeen

- the-boys.dl.nom

- ð̣aaħaku

- laughed

- *(ṣaaħib-hum).

- friend-their.acc

- ‘The two boys laughed with their friend.’

- b.

- l-waladeen

- the-boys.dl.nom

- raakað̣u

- ran

- *(l-bint).

- the-girl.acc

- ‘The two boys ran with the girl.’

We would like to claim, however, that the sentences in (55) only appear to involve a one-place construction at surface but in reality involve a two-place construction. In particular, we would like to maintain the hypothesis we adopted in Section 1 and assume that the t-morpheme allows an empty reciprocal anaphor [e]RECIP to appear as the required agentive object in (55), as shown in (55’).

- (55’)

- F6-unergative reanalyzed:

- a.

- l-waladeen<1+2>

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-ð̣aaħaku

- t-laughed

- [e]<1↔2>

- {

- okb-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub

- in-the-turn.gen

- }.

- ‘The two boys laughed with each other { oksimultaneously /#in turn }.’

- b.

- l-waladeen<1+2>

- the-boys.dl.nom

- t-raakað̣u

- t-ran

- [e]<1↔2>

- {

- okb-nafs

- in-same.gen

- el-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub

- in-the-turn.gen

- }.

- ‘The two boys ran along with each other { oksimultaneously / #in turn }.’

We may consider that parallel subeventualities are also induced in a crisscrossing fashion here by the reciprocality involved in these sentences, in (55’a) for example, between “each boy (A and B)” and “the other boy (B and A).” Since [e]RECIP must be anaphoric to a plural subject, a singular subject cannot introduce it, and an (overt) agentive object must appear, as we have already seen in (51). This contrast indirectly supports the postulation of [e]RECIP in (55’). Moreover, this analysis allows us to capture otherwise improbable reciprocal interpretations detectable in the unergative sentences in (55’) as indicated in their translations.

(C) A plural eventuality required by the F6-t-morpheme can also be created by symmetrical verbs, as exemplified by (57a–b) below. With such verbs, none of the participants need to be plural in number.

- (57)

- a.

- Bader

- Bader.nom

- t-faaṣal

- t-haggled

- maʕ

- with

- Bandar

- Bandar.gen

- ʕala

- on

- l-ʔasʕaar

- the-prices.gen

- {

- okwaʤh-an

- face-acc

- li-waʤh

- for-face.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub

- in-the-turn.gen

- }.

- ‘Bader haggled with Bandar over the prices { okface to face / #in turn }.’

- b.

- Bader

- Bader.nom

- t-saabag

- t-raced

- maʕ

- with

- Bandar

- Bandar.gen

- {

- okb-nafs

- in-same.gen

- l-wagt

- the-time.gen

- /

- #bi-t-tanaawub

- in-the-turn.gen

- }.

- ‘Bader raced with Bandar { okat the same time / #in turn }.’

We will analyze this case in more detail in Section 4.4 below.

(D) In pursuing the source of a plural eventuality in F6, we have encountered some examples that appear to constitute exceptions to our generalizations. Sometimes, F6 seems to be permitted even when none of (A)–(C) above is achieved, as illustrated by (58)–(60).

- (58)

- z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- t-baaħaθ

- t-discussed

- bi-l-muwð̣uuʕ

- in-the-subject.gen

- (#min

- from

- wagt

- time.gen

- la-θaani).

- to-second.gen

- ‘The man discussed the subject thoroughly (#from time to time).’

- (59)

- z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- t-laaʕab

- t-manipulated

- bi-l-natiiʤeh

- in-the-result.gen

- (#min

- from

- wagt

- time.gen

- la-θaani).

- to-second.gen

- ‘The man manipulated the result completely (#from time to time).’

- (60)

- z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- t-daaras

- t-studied

- bi-l-fikrah

- in-the-idea.gen

- (#min

- from

- wagt

- time.gen

- la-θaani).

- to-second.gen

- ‘The man studied the idea intensely (#from time to time).’

That is, F6 seems to be permitted even when a sentence does not involve any of plural participants, parallel subeventualities, or symmetrical verbs. None of these examples involves the second human/animate participant, either. The possibility of F6 in such sentences may suggest some essential inadequacy of the generalization made above. By pushing forward some creative and abstract thinking, however, we can envisage a way to capture cases like (58)–(60) under the proposed generalization.

First, the rejection of a distributive adjunct “from time to time” in these sentences suggests that these sentences all involve obligatory collectivity although such an interpretation is not directly or immediately detectable. Instead, they all seem to convey some implied meanings which may be characterizable as certain types of intensity or exhaustiveness as indicated by “thoroughly,” “completely” and “intensely” in their translations. We would like to claim here that such intensified interpretations are arising because the eventuality involved in each of these sentences can be analyzed as plural, involving the convergence of multifaceted or multi-angled subeventualities. Simply put, we consider that the event of “the man’s discussing the subject” in (58), for instance, was “thorough” because he examined various aspects of the subject. Similarly, “the man’s manipulating the result” in (59) was complete because he maneuvered various significant aspects of the result. As a matter of fact, these sentences can co-occur with the adjuncts indicating a plural eventuality but they cannot co-occur with the adjuncts indicating only a single eventuality, as illustrated in (61a–c).

- (61)

- a.

- “The man discussed the subject” in (58) followed by:

- {

- okmin

- from

- ʤawaanib

- sides.gen

- kθiireh

- many.gen

- /

- #min

- from

- ʤaanib

- side.gen

- waaħad

- one.gen

- }.

- ‘{ okfrom many sides / #from one side }’

- b.

- “The man manipulated the result” in (59) followed by:

- {

- okmin

- from

- ʕiddit

- several.gen

- ʤawaanib

- sides.gen

- /

- #min

- from

- ʤaanib

- side.gen

- waaħad

- one.gen

- }.

- ‘{ okfrom several sides / #from one side }’

- c.

- “The man studied the idea” in (60) followed by:

- {

- okmin

- from

- ʕiddit

- several.gen

- zawaaja

- angles.gen

- /

- #min

- from

- zaawjeh

- angle.gen

- waħadeh }.

- one.gen

- ‘{ okfrom several angles / #from one angle }’

The suggested analysis of (58)–(60) is also compatible with the observation that the verbs which express a one-time event cannot constitute a similar F6, as already seen in (50a–b).

Finally, even if the proposed account of (58)–(60) is adopted, we must still explain how such a plural eventuality can be made possible with the involvement of only a single initiator of the event. To fulfill this task, we would like to appeal to the notion “guise” proposed by Heim (1998) to explain why the violation of Principles B and C of the binding theory can be evaded in examples like (62a–b), respectively (Reinhart 1983; Higginbotham 1985; Grodzinsky & Reinhart 1993).

- (62)

- a.

- You know what Mary, Sue and John have in common?

- Mary admires John, Sue admires him, and John admires him too.

- b.

- He put on John’s coat; but only John would do that; so he is John.

In these utterances, the speaker believes, and intends the hearer to believe, that the highlighted NPs are coreferential despite the apparent violation of Principles B and C, respectively, induced by such interpretations. Heim (1998: 214–217) attempts to solve this conundrum by postulating two distinct “guises” of the same referent John and him/he in the given contexts which would lead to different cognitive values. In (62a), for example, John as an admirer and him as the admired appear as two distinct guises. Since the two guises are distinct from each other, they do not give rise to a binding relation in syntax, and hence do not violate Principles B/C. In their semantic interpretation, on the other hand, the interlocutors appeal to their knowledge and/or assumption that the two guises share the same referent and interpret them as coreferential.

Returning now to (58)–(60), we have claimed above that a plural eventuality in these examples is induced by the convergence of multifaceted subeventualities. Then, it probably is not entirely inconceivable that multiple guises as the initiators of such multiple subeventualities appear in these examples. In (59), for example, “the man as one guise addressed the problem from a theoretical angle,” and “the man as another guise addressed the problem from a practical angle,” and so on. Such multiple guises can induce parallel subeventualities while they refer to one and the same participant. The approach adopted in (D) is admittedly exploratory, but it allows us to capture not only the obligatory collectivity but also the otherwise inexplicable source of the intensified interpretation observed in (58)–(60), assimilating them into those discussed in (A)–(C). We will discuss this phenomenon in Section 4.4 below again, which suggests that (D) in fact can be regarded as a quite rational option the grammar of JA permits.

In short, F3 pluralizes an eventuality, requiring the involvement of more than one human (or animate) participant as the initiator of the same eventuality. Then, t-morpheme selecting F3 requires the subeventualities involved there to significantly overlap in time (and location), deriving F6 as a “collective” verb.

4.3 Derivation of Verb Form 8 from Verb Form 1

F8 is derived when the t-morpheme selects F1 as its input. F8 (ʔiC1tVC2VC3) is derived from F1 (C1VC2VC3) by: (i) t-prefixation (t-C1) followed by (ii) Flop (C1t), and (iii) compensatory ʔi-prefixation to avoid both a consonant cluster (#C1t) and a vowel (#iC1t) word-initially. (See Wright 1896: 41; McCarthy 1981: 390; among others.) F1 is an inflected but unaugmented verb form, which serves as the foundation in deriving many other verb forms. As already described in Table 2–(c–d) above, F8 sometimes yields reflexivity just as F5 does, but at other times it yields obligatory collectivity just as F6 does. How can we rationalize these phenomena? We will attempt to provide an answer below based upon the following reasoning. When F8 yields a reflexive interpretation, it must be the case that the F1 it selects shares whatever aspect of F2 which activates the “potential reflexivity” of the t-morpheme. Likewise, when F8 yields an obligatory collective interpretation, it must be the case that its input F1 shares the aspect of F3 which activates the “potential collectivity” of the t-morpheme.23 Let us now discuss each of these cases in turn.

First, since the basic function of the t-morpheme as a reflexivizer is to require united reference of the participants within a single eventuality, the only way the input unaugmented verb (F1) can satisfy this requirement would be to provide two participants. This reasoning will lead us to consider that F8 necessarily selects a transitive F1 whose two arguments can enter a felicitous self-related (or intrapersonal) relation when they are interpreted as united in reference, as exemplified in (63).24

- (63)

- Reflexive F8:

- a.

- l-ʔixwah

- the-brothers.nom

- ʔix-t-abu

- t-hid

- bi-s-siddeh.

- in-the.attic.gen

- ‘The brothers hid themselves into the attic.’

- b.

- li-wlaad

- the-boys.nom

- ʔir-t-amu

- t-threw

- ʕa-l-ʔasirrah.

- on-the-beds.gen

- ‘The boys threw themselves on the beds.’

Reflexive F8, on the other hand, is never possible with intransitive F1, i.e., unergative or unaccusative verbs.

In short, the reflexivity in F8 is induced more or less in the same way as that in F5, except that the united reference of the participants within a single eventuality is made available by the unaugmented verb (F1) which denotes a self-related (or intrapersonal) relation.25

Next, the t-morpheme as a collectivizer requires the involvement of a plural eventuality in the input verb. In most, if not all, cases of collective F8s, this requirement seems to be fulfilled when the input unaugmented verb (F1) is symmetrical in nature, as in (64a–b).

- (64)

- Collective F8 (Plural subject):

- a.

- z-zalameen<1+2>

- the-men.dl.nom

- ʔif-t-aragu

- t-separated

- [e]<1↔2>.

- ‘The two men separated from each other.’

- b.

- l-waladeen<1+2>

- the-boys.dl.nom

- ʔix-t-alaṭu

- t-mingled

- [e]<1↔2>.

- ‘The two boys mingled with each other.’

Both of these sentences exhibit only a collective reciprocal interpretation (e.g., (38d)) and their subjects must be plural (as will be shown directly below in (65a–b)). This set of facts naturally leads us to postulate an empty reciprocal anaphor as an agentive object in these sentences. The collectivity of the t-morpheme in (64a–b), in other words, seems to be activated by the plural eventuality in F1 that is induced perhaps by the combination of (A) (parallel subeventualities), (B) (plural participant) and (C) (symmetrical verbs) discussed in Section 4.2 above.

If we alter the plural subject in (64a–b) into a singular one, on the other hand, an overt agentive object is required to appear (in the PP complement), as in (65a–b).

- (65)

- Collective F8 (Singular subject):

- a.

- z-zalameh

- the-man.nom

- ʔif-t-arag

- t-separated

- *(ʕan

- from

- marat-uh)

- wife-his.gen

- ‘The man separated from his wife.’

- b.

- l-walad

- the-boy.nom

- ʔix-t-alaṭ

- t-mingled

- *(bi-l-bint)

- in-the-girl.gen

- ‘The boy mingled with the girl.’

Here, a plural eventuality was induced by the addition of an agentive object combined with a symmetrical verb ((C)). The situation is similar to (A) but the involved subeventualities are recicprocal rather than parallel. We will discuss this case in more detail in Section 4.4 below.

Thus, the collectivity in F8 is induced more or less in the same way as that in F6, except that (C) seems to be always involved for F8. We have not encountered any collective F8 licensed by (D) (convergence of multifaceted subeventualities), either. As will be discussed directly below in Section 4.4, however, there is a good reason for these restrictions.

4.4 Collectivity with single subjects

Having examined both semantics and morphology of collectivity, we now are ready to rationalize how a plural eventuality is induced with a singular subject in some t-marked collective constructions.

Since the t-morpheme in JA is a collectivizer, it needs to be associated with the operator Coll. Coll in turn needs a plural eventuality to operate on, and hence requires the presence of Dist, as in (66) (cf. (34)).

- (66)

- [TP Sbj1 [CollP Coll [DistP Dist [VP t1 t-V Complement ]]]]

When the subject is singular and Dist cannot identify a plural eventuality in the sentence, the grammar of JA seems to permit two ways to devise a plural eventuality.

One method is to introduce an agentive object and appeal to the symmetrical property of the involved verb. For instance, as we saw with (51) and (52) in Section 4.2, when the F3 (as the input to the t-marking of F6) implies loose symmetricity/parallelism, the introduction of an agentive object makes parallel subeventualites available, which can be collectivized by F6. When the F3 verbs imply more direct symmetricity (i.e., simultaneity), e.g., race, hug, kiss, and fight, the introduction of an agentive object gives rise to a crisscrossing plural eventuality and hence recipricality. The interpretation derived by this strategy as in (67) below is generally recognized as “discontinuous reciprocality.”26

- (67)

- el-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-saabag

- t-raced

- maʕ

- with

- ʔuxt-uh.

- sister-his.gen.

- ‘The boy raced with his sister.’

JA permits another method to devise a plural eventuality with a singular subject. When the input F3 does not imply any kind of symmetricity/parallelism, e.g., help, forgive and blame, the strategy adopted for (51)–(52) and (67) is not available. We believe that a plural eventuality can be devised in such cases with the “guises” of a singular subject, provided that the emerging multifaceted subeventualities are semantico-pragmatically felicitous, as observed with (58)–(60) in Section 4.2. The same strategy is adopted with an asymmetrical F3 as in (68) below, which cannot induce “discontinuous reciprocality.”

- (68)

- el-walad

- the-boy.nom

- t-ʕaawan

- t-helped

- maʕ

- with

- ʔuxt-uh.

- sister-his.gen

- ‘The boy helped his sister a great deal / in many aspects.’

The multifaceted subeventualities arising here can be detected by the “intensified” interpretation (a great deal/in many aspects) which suddenly pops up in this sentence. The presence of “discontinuous reciprocality” in (67) and its absence in (68) can also be demonstrated when we see that the reciprocality of the former cannot be negated as in (69a) while the reciprocality of the latter can be negated as in (69b).

- (69)

- a.

- (67) +

- #w-laakin

- and-but

- ʔuxt-uh

- sister-his.nom

- maa

- neg

- t-saabagat

- t-raced

- maʕ-uh.

- with-him.gen

- ‘The boy raced with his sister, #but his sister did not race with him.’

- b.

- (68) +

- okw-laakin

- and-but

- ʔuxt-uh

- sister-his.nom

- maa

- neg

- t-ʕaawanat

- t-helped

- maʕ-uh.

- with-him.gen

- ‘The boy helped with his sister, okbut his sister did not help him.’

Note that (69a) also makes a sharp contrast with (20) in Section 2.2, which involves a plural subject.

4.5 Two functions of t-morpheme